Small combat units of the Kriegsmarine

As K-Verband , and command of small combat units (CCG) called, various units of the German are Navy referred to in naval warfare of World War II possessed weapons of small size. Under small arms the high command of the navy understood independently operating and easily deployable maritime combat units. These were primarily manned torpedoes, combat swimmers, micro-submarines and explosive devices. The use of the small combat units ended with the surrender of the Wehrmacht on May 8, 1945, with the last two combat swimmers operating until May 11 and May 12, 1945 respectively.

Their formation was part of a defensive strategy of the Kriegsmarine, which was supported by Hitler . From the spring of 1944 onwards, the latter was forced to develop a naval combat concept that should allow the management level to sink supply , war and merchant ships of the Allies in the coastal apron using a "pinprick tactic" and thus reduce supplies. Their use also served to disrupt the Allied shipping routes and to tie up forces. At the same time, the submarine war should be intensified in order to achieve a decisive turnaround in the war.

Origins and Conception

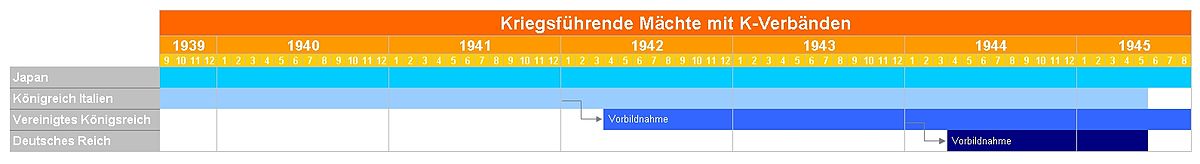

From the late 1930s onwards, the Imperial Japanese Navy developed various small weapons, some of which were micro-submarines used in the attack on Pearl Harbor . During the initial phase of the Pacific War , the funds for the further development of Japanese small-scale weapons were largely cut and only increased again when the Japanese were pushed ever more on the defensive and lost many of their large surface units. The first small maritime combat units on the European theater of war were set up by the Kingdom of Italy with the establishment of Decima MAS in spring 1941. Italy was able to fall back on development and operational experience from the final phase of the First World War and then until 1943 provided the only successfully operating small combat units in the Mediterranean region. After the armistice of Cassibile in September 1943, the association joined the armed forces of the fascist Italian Social Republic . As early as the spring of 1942, the British Royal Navy had developed its own small weapons. It was based on captured or recovered manned torpedoes and miniature submarines of the Italians. The British small weapons were subject to the Underwater Working Party (UwWp) together with the combat swimmers .

From the spring of 1944, the Navy began to develop its own small weapons and set up units. The main focus was not on the associations of the axis partner Italy , but on the British developments, which were considered more effective than the Italians.

A main reason for the relatively late formation of the German K-formations was the doctrine of Erich Raeder , which still dominated until the first years of the war , which concentrated the German naval armament plans on large surface units. The naval armament program of 1938/39 did not include small combat units in the Z-Plan , but mainly large units.

Successful British commando actions and acts of sabotage in Saint-Nazaire and North Africa , which were carried out around the turn of 1942/43, made the German naval command around the new Commander-in-Chief of the Navy, Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz , aware of the possibility of successful operations in the smallest of naval units. Doenitz then considered setting up his own small combat units for the first time, which he called the Mountbatten Organization at that time . He was strengthened in these considerations by various external factors. The German shipbuilding industry was no longer able to build larger ships due to the increasingly massive Allied bombing raids. Only submarines and other smaller units could be built in the new underground shipyards. In addition, the scarcity of resources such as steel hit the navy particularly hard, as the army's tank program and the air force's fighter program took precedence over the navy's submarine program and thus received preferential supplies. Another important reason was the proof of achievement by the British and Italians. With just a few soldiers and tiny units, they were able to damage and sink even larger ship units and, moreover, tied up massive enemy forces. Doenitz therefore saw in its own small weapons a cost-effective way of covering the German-occupied coasts with a blocking network of small units that could be produced quickly in order to be able to hinder or even avert a possible invasion of "Fortress Europe".

The main considerations for such a possible invasion were:

- In view of the overwhelming mass of American war material and its air superiority, the creation of a bridgehead could not be successfully combated with the existing German forces. The bridgeheads that were formed would be shielded from German counter-attacks and expanded by bomb carpets, the radius of which was constantly increasing.

- If an attack were to take place on these bridgeheads, it would have to concentrate primarily on the enemy’s supplies. Since an Allied air superiority had to be assumed, the interruption of the supply lines could only be imagined by an underwater weapon. The fact that the opposing ships would have to penetrate into the narrower coastal area would be seen as beneficial. According to this, a submarine weapon could be used, which only had a small driving range, but should still carry maximum explosive effect with it.

- The future landing sites of the Allied units could only be guessed at. Therefore, an underwater weapon should be developed, which can be produced in large numbers and brought to any point by night transport without great effort by train and truck. Once there, it should be able to be brought into the water immediately without any major devices.

The Allied invasion of southern Italy in September 1943 and the landing in Normandy in June 1944 created this situation, however, before K units could be set up.

Lineup

As early as 1929, the first drafts for the use of manned torpedoes were submitted to the naval management of the then Reichsmarine . However, they were rejected because of the terms of the Versailles Treaty . The Mignatta used by Italy in the First World War were the basis for this first conception of so-called “small arms” . In the course of the mobilization of 1938, the High Command of the Navy (OKM) under Erich Raeder again submitted several proposals for manned torpedoes, which were rejected by the latter for unknown reasons. In the following period, individual concepts were repeatedly presented to the OKM, none of which, however, was further developed to readiness for series production. For example, Heinrich Dräger from Drägerwerke presented several plans for a small submarine to the OKM in October 1941, but these were rejected.

With the appointment of Karl Dönitz as Commander in Chief of the Navy on January 30, 1943, a rethink began in the naval leadership. During a meeting when Dönitz took office on January 30th, the potential use of small combat units was mentioned. In the same meeting, Doenitz also expressed the wish that such small combat units should be set up under the direction of Rear Admiral Hellmuth Heye . However, since this was initially not available from his post as chief of staff of the Naval Group Command North , Vice Admiral Eberhard Weichold was initially entrusted with the planning and installation. During the planning phase, in which the term "K-Associations" was used for the first time, the following priorities were set in order to accelerate the establishment of the associations:

- Development and construction of a usable mini submarine based on the British model and its use in targeted individual enterprises

- Development of several small torpedo carriers for various purposes, including small speed boats based on the model of the Italian explosive boats

- Continuation of the establishment and training of Marine Operations Commandos (MEKs), which were to carry out attacks on enemy coastal objects such as radar stations, gun emplacements and port facilities from small ships and submarines as British-style raids.

Since the Navy had no experience in the field of small arms, the OKM sent Paul Wenneker , the naval attaché at the German embassy in Tokyo , a questionnaire on the Japanese class A micro submarines . With the help of this catalog, Wenneker should obtain the necessary information about the construction and operational capability of the type A. After several inquiries, the Japanese naval command granted Wenneker and the Italian naval attaché permission to inspect a boat on April 3, 1943. However, since the Japanese refused to provide any information about the technical specifications, this inspection did not yield any new information. Since no information transfer was to be expected from Japan in the future either, it was decided that the development of the K-formations should be based on the developments of the Royal Navy . The experience gained by the Italians in this area so far has only been used in the case of the explosive boats.

At around the same time, Corvette Captain Hans Bartels began setting up the first mobile and operational unit in Heiligenhafen , which was named the Heiligenhafen Operations Department . The unit consisted of 30 navy and army members and was divided into two companies. The first was under Bartels own command, while the second was led by Lieutenant Michael Opladen. The main task should be to carry out covert command operations on the British coast and in the Adriatic , which is why the operations department can be regarded as the forerunner of the later "naval operations commands". The department was subordinate to the Naval High Command East . The members had to commit themselves to the strictest secrecy and to breaking off all civil contacts, including with their own families. In addition, they were given a permanent ban on exit and leave. The first instructors came predominantly from the ranks of the army pioneers, who had mainly gained front-line experience in the Soviet Union . Experienced motor vehicle mechanics, radio technicians, sports and swimming instructors, diving and hand-to-hand combat specialists were later added in order to be able to cover a broad spectrum with the training.

On September 21, 1943, an attack by British X-class submarines on the battleship Tirpitz ( Operation "Source" ) showed how vulnerable even the largest ships could be to such attacks. The attackers were discovered by German patrols after their ground mines had been cast and their boats sunk. The Kriegsmarine recovered one of the sunk X-Crafts and brought it to Germany for investigation, where it was subsequently used as a model for the first German micro-submarine, the Hecht .

In March 1944, Heye took over the leadership of the K-formations as admiral of the small combat units and general advisor for special weapons in the OKM. After Weichold had already created a rough structure for the future small combat units, Heye only had to refine it. He therefore now focused on equipping the associations with suitable means as quickly as possible and on recruiting additional volunteers. A commission formed by him visited selected training locations for officers and NCOs and recruited people who appeared to be suitable.

Start of development, armaments and production forging

| Overview of the development of the German micro-submarines | |||

| Pike (from May 1944) |

Beaver (from May 1944) |

Newch (from June 1944) |

Seal (from September 1944) |

|---|---|---|---|

After the technical analysis of the recovered X-Craft , the first model of a class of miniature submarines for the Navy, the pike , was created on the basis of the knowledge gained . This was able to transport and use a detention mine or a torpedo . Further knowledge for the development could be gained from a British boat of the Welman type . This, with the identification W-46 , got caught in a fishing net during a mission off Bergen on November 21, 1943 and was thereby forced to surface. It was discovered by a nearby guard boat, whose crew was able to bring the boat up unscathed. The German small submarine class Biber was created on the basis of the Welman . Pike and beaver became the basic development pattern for all of the following German micro-submarines. Around the same time, the first manned torpedo of the Kriegsmarine, the Neger, was built . The creator was Richard Mohr, whose one-man torpedo was approved for series production by Hitler on March 18, 1944 based on plans. At the same time, Hitler also approved the construction of initially 50 miniature submarines.

Since Mohr relied on partially existing weapon systems such as the G7 torpedo , the modified version of which formed the Negro's fuselage , when developing the Negro , the first prototypes could be completed in March 1944. The test was carried out in Eckernförde by Johann-Otto Krieg and revealed various weaknesses of the torpedo, including its inability to dive. Although the deficiencies were well known, the OKM quickly classified it as a “front-tire” device due to its simple construction, probably also against the background that at that time no other operational small weapons were available. The first 40 pilots of the future flotilla consisted of members of the army and the Waffen SS . Due to their lack of experience in the fields of nautical science , navigation and torpedo shooting, these subjects had to be trained intensively. The Spica , the former cargo ship Orla , which was converted into a navigation training ship and put into service on June 15, 1944, was used for navigation training in particular . The practical training took place predominantly in maneuvers, which also took place at night. This was the first time that a pilot died as a result of a technical defect. At the beginning of August 1944, Krieg finally reported to his superior Heye that the newly established K-Flotilla 361 was fully operational .

The K-Associations later obtained their operational weapons and equipment from an increasing number of manufacturers. These included many Italian companies that mainly supplied engine parts for the MTM, MTR, MTRM, MTSM and MTSMA types of explosive vessels and speedboats. However, their production could no longer be maintained towards the end of 1944 due to the increasing partisan activity and the retreating front in Italy.

- Shipyards of the K-Associations

|

|

|

- Total production figures of small weapons

| Total production numbers of K funds | |||||||||||||

| K-means | 05/1944 | 06/1944 | 07/1944 | 08/1944 | 09/1944 | 10/1944 | 11/1944 | 12/1944 | 01/1945 | 02/1945 | 03/1945 | 04/1945 | total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newt | - | 3 | 8th | 125 | 110 | 57 | - | 28 | 32 | - | - | - | 363 |

| beaver | 3 | 6th | 19th | 50 | 117 | 73 | 56 | - | - | - | - | - | 324 |

| pike | 2 | 1 | 7th | 43 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 53 |

| seal | - | - | - | - | 3 | 35 | 61 | 70 | 35 | 27 | 46 | 8th | 285 |

| lenses | 36 | - | 72 | 144 | 233 | 385 | 222 | 61 | 37 | 11 | - | - | 1201 |

| MTM | - | 10 | 45 | - | 50 | 58 | 50 | 52 | 83 | - | - | - | 348 |

| SMA | 1 | 16 | 3 | 4th | 3 | 7th | 6th | 7th | 16 | - | - | - | 63 |

| Hydra | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 13 | 11 | 9 | 6th | 39 |

| total | 42 | 36 | 154 | 366 | 516 | 615 | 395 | 218 | 216 | 49 | 55 | 14th | 2676 |

Physical and psychological inadequacies

The construction-related narrowness of the small weapons led among the K pilots, who were also known colloquially as captains , that they already showed serious psychological problems such as claustrophobia and panic attacks during the test drives. They also often suffered from anxiety disorders . There were also human needs such as urination and bowel movements . Many pilots also suffered from severe flatulence , which they tried to counter with a strict "non-bloating" diet before and during the mission. During the voyage, the pilots had no choice but to collect their secretions in vessels and containers, which were then emptied on occasion during an overwater voyage. Often, however, this was not possible, and in particular the crews of the seals were sometimes seated up to their waist in a mixture of washed-in seawater, diesel distillate, leaked oil, feces , urine and vomit. In some cases, the hygienic conditions were so extreme that crew members became seriously ill. To prevent this, the budding lone warriors went through tough training in which they were supposed to improve their mental and physical fitness. Their daily training consisted of a 10,000 meter run in the morning , followed by close combat exercises or night marches over 30 km. The deployment preparation also included sitting exercises in the K-means, which could last 20 hours.

The pilots' physical problems were countered with the “ D-IX ” tablet, which was a drug mix of oxycodone (brand name Eukodal, an analgesic opioid), cocaine and methamphetamine (brand name Pervitin ). Extensive tests with this preparation showed that the pilot fell into euphoria that lasted two to three days and then into total exhaustion. Later seal crews, whose missions could last several days, were later also given pure pervitin or the identical isophane, which could cause hallucinations after taking it for days . The use of Pervitin was first examined in September 1938 by the Navy on 90 test subjects at the Military Medical Academy in Berlin. In 1944 these attempts were extended to athletes and prisoners of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp . The result of these attempts was that the doctors advised against Pervitin, as it could cause a failure of the central nervous system after it was fully effective. They therefore suggested that the pilots should instead take mainly kola chocolate ( Scho-Ka-Kola ) and only add small doses of pervitin. The chocolate consisted of 52.5% cocoa and 0.2% caffeine . The use of stimulants to improve performance was widespread during World War II. For example, drivers in the German army were often given stimulants in order to be able to cope with the enormous distances on the Eastern Front. This practice was used at least on the British and American sides.

organization

| Armed forces of the small combat units of the navy | ||||

| Explosives | Speed boats | Manned torpedoes | Small submarines | Task forces |

|---|---|---|---|---|

The organization of the small combat units of the Kriegsmarine comprised a large number of internal structures, at the upper end of which was the command staff of the K units. The operational management staff of small arms and the associated personnel and training departments were directly subordinate to him. The troop medical care was the responsibility of the quartermaster staff. The K-formations were tactically subdivided by the small weapons staffs (K-staffs), which were named after the respective area of operation. In addition to various training commands, the further structure also included the naval operational commands, the K flotillas and the K divisions.

In this context, the established structure was used to form the different types of weapons of the K-formations, which, roughly structured, comprised three important components: the group of micro-submarines, explosives and combat swimmers. The Navy based itself on the historical model of the Italian Decima MAS , which also considered these three branches of arms as small arms. In addition, the specially set up research and development department of the K-associations served to test various prototypes, some of which were trend-setting and far ahead of their time, others were purely utopian.

Troop strength

In the development phase of the K associations, Heye calculated a staffing requirement of 17,402 people. Of these, 794 were to be officers and officer cadets and 16,608 non-commissioned officers and men . The largest part was planned for the floor organization, which was to consist primarily of drivers , administrative employees and maintenance and repair teams. Dönitz gave in to this requirement and at the same time confirmed that he would give Heye any support on the personnel issue. However, he denied Heye the opportunity to recruit commanders of normal submarines for his units. The recruitment was done by means of advertising and targeted propaganda , since entry into the K-associations should generally be on a voluntary basis. Initially, the K-Associations tribe comprised only a few hundred people. With the establishment of the units, the troop strength rose to around 8,000 men by October 1944, including ground personnel. How these were distributed to the various branches of the K-Associations is not known, nor are there any interim personnel balances. So it can only be estimated on the basis of the known boat units in which order of magnitude the troop strength moved at different times. In mid-December 1944, 221 boat units were stationed in the Scheldt region and 263 units at the end of January 1945; this number thus roughly indicates the number of pilots and helmsmen.

More concrete figures will only emerge at the end of the war. On May 6, 1945, about 3,000 men, mainly members of the seal flotilla, were taken prisoner of war in IJmuiden, the Netherlands . These numbers, which are put at around 5,000 in other sources, have not, however, been differentiated between members of the K-units and other members of the air force, navy and army. Therefore no exact figures for the members of the K-associations in the Netherlands can be taken from it. On May 8, 1945, the K units stationed in Norway surrendered with a total of 2,485 men. In addition, there are the personnel of the K-formations on the Adriatic coast, which were deployed in regular army units in the first days of May 1945. This also does not take into account the strengths of the naval commandos, the teaching staff of the various training facilities and the associations that are currently being set up such as the 1st Hydra Flotilla . Around 450 combat swimmers had been trained by the end of the war. These figures suggest that the total strength of the K units was around 10,000 men. Of these, around 2,500 were pilots or helmsmen, of whom about 250 were helmsmen with the seals . Other sources put the number of personnel in the K units at the end of the war at around 16,000 men.

Awards and uniforms

Within the associations, the strict service regulations of the Navy and Wehrmacht with regard to clothing were not implemented to the same extent as was often the case in other places. Badges of service and rank were rarely worn. This went back to an initiative by Heyes, which was supposed to create a certain informality and give the individual the feeling of belonging to a special unit. In addition, it should encourage soldiers of different ranks to deal with one another in a non-self-conscious manner.

The members of the K-Flotilla 611 (1 assault boat flotilla) were entitled to the Ärmelband Hitler Youth to wear. This authorization was given in the course of a military parade in Dresden by Reich Youth Leader Artur Axmann and Karl Dönitz to the flotilla chief Kapitänleutnant Ullrich, who was present with his relatives at the parade, on behalf of the Führer . The cuff was similar to that of the 12th SS Panzer Division and only differed in its navy blue material. For "security reasons", however, it was not worn by the members of the flotilla because they feared reprisals by Allied interrogation officers in the event of a capture.

Orders and decorations were awarded according to different criteria. The usual award for the successful sinking of a merchant ship or a destroyer was the German Cross in gold . If a cruiser was sunk, the victim could even hope for the Knight's Cross . As a rule, the Iron Cross II and / or I class was awarded jointly or individually after the first assignment. It didn't matter whether the mission was successful or not. While in the course of the Allied invasion of Normandy the Knight's Cross was awarded to six members of the K-associations for relatively "low" achievements, later and much higher rated deeds were not honored with the highest honor. Instead, the German Cross in Gold was awarded to dozens of members of the K associations until the end of the war, for example 13 times in connection with the sea battles in Normandy. Other awards were also made to combat swimmers and seal crews. The award practice therefore served more as an incentive than to honor military successes. The Wound Badge was issued for wounds suffered in action . However, possible injuries during practice drives without direct enemy influence were not taken into account. By the end of November 1944, however, there was no “weapon-typical” combat badge within the K-associations that clearly identified the recipient as a member of the K-associations. Preliminary considerations, which had initially considered the submarine war badge , were discarded as this could not cover the entire range of K-missions (explosives and combat swimmers). Instead, the probation and combat badge for small weapons was created on November 30, 1944 in order to be able to honor future K deployments of all relatives. When designing the probation and combat badges, the swastika and imperial eagle were omitted and the sawfish was chosen as the symbol of the K-associations.

Calls

The naval missions of the German small arms combat initially concentrated in April 1944 on the west coast of Italy and the sea area near Anzio in order to attack the bridgehead formed there by the US Army and thus to prevent or at least disrupt the supply. After their failure, the fighting of the K-formations shifted to the invasion front in Normandy, where violent sea battles broke out in July and August 1944. The K-formations suffered high losses, while the losses of the Allies were relatively small. The K operations around the Normandy landing did not have any influence on the further course of the war. After the withdrawal of the Wehrmacht to central and eastern France, which began between the end of August and the beginning of September, the K units were reorganized on the Dutch coast by the end of the year. From there, from October 1944 onwards, they intervened again with beavers and lenses in the sea battle for the mouth of the Scheldt and its important shipping routes. In January 1945, the newly commissioned seals reached Holland and operated until the end of April 1945 under poor external conditions in the area between Holland and the Thames estuary with moderate success. The remaining K-formations in the Mediterranean and the Adriatic, mainly lentils and martens , only took action sporadically until the end of the war and could not meet the expectations placed on them. Their missions against sea targets off the southern French and Croatian coasts were mostly unsuccessful, with high losses. The combat swimmers of the K associations had been operating on most of the important sections of the front since June 1944 with varying degrees of success. However, they were able to achieve their goals significantly more than the submarines and explosives. The K units stationed in Norway did not intervene in the war, apart from a single attempt. In the final battle for the German Reich, the remaining K-formations were used for numerous river operations. The main task here should be the destruction of important bridges on the western and eastern fronts. The combat swimmers in particular were able to more or less fulfill their missions again.

Balance sheet

| Sinking statistics of the K-formations according to Fock | ||

| Branch of service | Sinkings | Damage |

| manned torpedo |

1 cruiser

2 destroyers 3 M-boats 1 merchant ship 1 trawler 1 LCG |

-

|

| Small submarine |

1 destroyer

9 merchant ships (18,451 GRT) |

3 merchant ships (18,384 GRT)

|

| Explosives |

-

|

-

|

| Total |

19 ships

|

3 ships

|

The re-evaluation of the “successes” of the German K-formations and other small maritime combat formations in World War II shows that they did not have the overwhelming success often claimed by the propaganda. Even the seals , which were seen as the most promising of the German projects, could not meet the expectations placed on them, mostly due to technical deficiencies. Various information is available about the actual success rates of the K associations. Depending on the source, they fluctuate between 15 and 19 sunk ships, with the sunk tonnage data also being subject to major differences. The literary works by Paterson and Blocksdorf do not show a final balance and are limited to the successes of the sinking and damage at the individual locations or during the operations shown. The highest sinking rate for the month of April 1945 alone is estimated at around 120,000 GRT and is said to have been achieved solely by seal- type boats . A similar number, to be regarded as utopian, is the sinking rate of the beavers , which are said to have sunk around 95,000 GRT between December 1944 and April 1945. The successes in the sinking of the lenses in the course of the missions in Normandy alone are estimated with 12 ships, including a tanker with 40,000 t as well as the HMS Quorn and the HMS Gairsay . While the sinking of the two British warships has been confirmed, there is no evidence of the sinking of the nameless tanker.

In a comparison of the total of sunk and damaged ships with the effort and the units lost on the German side due to the successful Allied defense and technical deficiencies, the balance of the K-formations is rated as negative by Rahn. Tarrant agrees with this opinion, but also emphasizes the haphazardness of the operations, which made them ineffective despite undisputed bravery. In addition, he classifies all developments except for the seal , which was also unable to meet the expectations placed in him, as undesirable developments without military use. In his work The Last Year of the German Navy May 1944 to May 1945 , he puts the number of sunk ships at 42 and the number of damaged ships at six, but does not give any tonnage. He is referring to a work by William Shirers from 1960. Rahn, in turn, took over these figures from Tarrant, but added that the seals sank nine ships with 18,451 GRT from January to May 1945. This deviation seems to have come about because Tarrant's balance sheet closes at the end of April 1945, while the Rahns go on to surrender on May 8th. In his publication Marine-Kleinkampfmittel (Nikol Verlagsvertretungen), Harald Fock names a total sinking (April 1944 to May 1945) of 19 ships including the destroyer La Combattante with more than 18,451 GRT and four damaged ones with more than 18,384 GRT. On the other hand, the Allies justified the sinking of La Combattante by a mine hit.

- Deployment statistics of the K associations after selected months

| K-sorties in April 1944 | ||||

| Branch of service | Patrols | losses | Sinkings | Damage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negroes | 23 | 10 | - | - |

| total | 23 | 10 | - | - |

| K-sorties in January 1945 | ||||

| Branch of service | Patrols | losses | Sinkings | Damage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| seal | 44 | 10 | 1 | - |

| Beaver & Newt | 15th | 10 | - | - |

| lenses | 15th | 7th | - | - |

| total | 74 | 27 | 1 | - |

| K-sorties in February 1945 | ||||

| Branch of service | Patrols | losses | Sinkings | Damage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| seal | 33 | 4th | 2 | 1 |

| Beaver & Newt | 14th | 6th | - | - |

| lenses | 24 | 3 | - | - |

| total | 71 | 13 | 2 | 1 |

| K-sorties in March 1945 | ||||

| Branch of service | Patrols | losses | Sinkings | Damage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| seal | 29 | 9 | 3 | - |

| Beaver & Newt | 56 | 42 | 3 | 1 |

| lens | 66 | 27 | - | - |

| total | 151 | 78 | 6th | 1 |

| K missions in April 1945 | ||||

| Branch of service | Patrols | losses | Sinkings | Damage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| seal | 36 | 12 | 2 | 2 |

| Beaver & Newt | 17th | 9 | 4th | 1 |

| lens | 66 | 17th | - | - |

| total | 119 | 38 | 6th | 3 |

|

Number of missions and missions of the K-units (January to May 1945) |

|||||

| Branch of service | Patrols | losses | Loss rate | Sinkings | Damage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| seal | 142 | 35 | ≈ 25% | 8 (17,301 GRT) | 3 (18,384 GRT) |

| Beaver and newt | 102 | 70 | ≈ 69% | 7 (491 GRT) | 2 (15,516 GRT) |

| lenses | 171 | 54 | ≈ 32% | - | - |

| Total | 415 | 159 | ≈ 42% | 15 (17,792 GRT) | 5 (33,900 GRT) |

The reasons for the failure of the K-formations were varied. In addition to the inexperience of the crews and technical problems, the reasons were bad weather and the constriction of supplies due to the Allied air superiority. The latter, in particular, together with the collapsing front from February 1945 onwards, considerably reduced operational readiness. The lack of spare parts forced the flotilla bosses on site to use some of their units as "cannibalization models" in order to be able to guarantee at least a minimum of operational performance. As early as January 1945, the falling allocations to fuel meant that individual K-formations were no longer operational. The instruction of the OKM to conserve fuel supplies to the utmost, meant in practice to put the boats "on the chain". All exercise and routine trips were canceled and the use of the K-formations was only permitted for promising combat activities. In Holland, most of the remaining capacities flowed to the seals , since, in the opinion of the OKM, they could provide the greatest military benefit. With this in mind, it is astonishing that many of the flotillas were still at least marginally able to carry out operations until the end of April. The associations were able to benefit from the support of Armaments Minister Albert Speer , who gave the seal building program the highest priority. Therefore, almost only these were built in the final phase.

As the war progressed, the K units also suffered from a lack of personnel to make up for their losses. The recruitment, which was initially on a voluntary basis, resulted in fewer and fewer reports of suitable persons, so that Admiral Heye was increasingly concerned that the operational capability would not be limited by the number and technical condition of boats, but by a lack of pilots. The staff shortage was also due to the fact that the service of the seals required qualified personnel. The Mürwik Naval School and other training units could no longer adequately cover this need, which is why the training period was shortened. The resulting, sometimes glaring gaps in knowledge of the pilots often led to damage to the boats through incorrect operation.

From May 1944 to April 1945, the German armaments industry produced a total of 2,676 units of the various types, which, due to the high losses suffered, was never enough to meet the needs of the individual associations. The high losses of the K-formations, especially in the battle around the Scheldt estuary and in the Mediterranean Sea, also resulted from the Allied air sovereignty, because of which the air force was unable to provide sufficient or even air cover during operations. As a result, many boats fell victim to Allied airmen. As these casualties increased, Hitler personally asked Hermann Göring , the Commander-in-Chief of the Air Force, whether at least the ports of operations could not be shielded by sufficient anti-aircraft guns and whether it was possible to use artificial ones to prevent the beavers and seals on their way in and out To protect fog banks.

In contrast to other areas of the Wehrmacht, there was apparently hardly any decline in morale or general disintegration in the K units. This may have been due to the informal leadership style of Brandi and Heye, who nevertheless and repeatedly tried to give their soldiers the feeling of belonging to a special elite unit.

Assessment of the loss rate

|

Number of missions and missions of the K-units (January to May 1945) |

|||

| Branch of service | Calls | losses | Loss rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| seal | 142 | 35 | ≈ 25% |

| Beaver and newt | 102 | 70 | ≈ 69% |

| lens | 171 | 54 | ≈ 32% |

| Total | 415 | 159 | ≈ 42% |

Compared with the failures of other branches of service over the entire war, the losses of the K units are to be regarded as extraordinarily high. It is difficult to explain this rate of loss, as it ran parallel to the fate of the submarine weapon in 1944 and 1945, during which the losses also rose sharply. Often, however, the argument is put forward that the high toll on human life was also caused by the fact that the K-units were set up as “suicide squads” and their staff were indoctrinated into fanatical lone fighters. As a result, the K associations are partly to blame for this high rate. However, this statement is often contradicted.

The K-formations as a whole, like the ram hunters of the Luftwaffe , which are often cited as examples of German "suicide missions", were in principle not set up as a self-sacrifice unit. Neither here nor there were there directly ordered “death missions”, even if these were given out in clauses before the mission or by radio at the K-units. However, both air ramming and sea collision trips always provided for the driver or pilot to be able to exit in good time. Heye put it in a publication published in 1955 in such a way that the “highly civilized peoples of the white race and the crew of these weapons, in contrast to, for example, the Japanese fatal planes, (must) have a real chance of survival in combat and a return”. Heye thus underlined one of the fundamental principles of the K associations. This stated that every lone fighter had to have the certainty that there was a high probability that they would survive before deploying. In fact, the K-men who were discovered and pursued by the enemy defense should prefer imprisonment to "heroic death". In one of his quotations, Heye goes even further and tries to explain the balancing act between the sacrifice of a few and the futility of these acts:

“It may be that one or the other can be found among our people who not only expresses their willingness to die such a sacrificial death, but also has the psychological strength to carry it out. I was and still am of the opinion that such acts can no longer be performed by members of cultivated peoples of the white race. Thousands of brave men can indeed act in the sudden intoxication of a fight without regard to their own life, as it has certainly often happened in all military powers of the world, but the sacrificial death, which is inevitably certain hours or days before its occurrence for the person concerned, becomes our peoples can hardly become a generally applicable form of struggle. The European does not have the religious fanaticism that enables him to do such deeds; he also no longer has the primitive contempt for death and thus his own life. "

His today seemingly racist statement is underlined by the demands of the OKM, which, when designing the K-weapons, was based on reusable devices or at least weapons with which the soldier had the opportunity to return to his own lines after the attack. The only exception were the Linse type explosives , which were supposed to cover the rest of the way to the target unmanned or remote-controlled before the planned collision, after the pilot had jumped off. So neither were Negroes still beaver , pig , pike or seal fitted with explosives contacts or percussion fuses that use suicide by ramming as the Japanese Kaiten would have allowed. The mostly acute staff shortage of the K-associations and the high training expenditure of the lone fighters also speak against the practice of sacrifice. The proclaimed sacrifice was apparently not passed on to the soldiers by the training officers either. Johann-Otto Krieg said several times to his “students” that when they had come to the conclusion that they had no way of returning home, they should approach the next ship, sink the negro or martens and shout for help. Self-sacrifice is pointless, since survival, even if it is in captivity, is the most important thing.

However, these arguments and statements were partially negated by the commanders and lone fighters involved in combat operations. From August 1944 onwards, the words “Winkelried”, “Kamikaze”, “victim fighter” or “victim fighter”, “total deployment” and “storm viking” were increasingly found in the war diaries of the naval war command. These terms describe a form of military operation in which soldiers were consciously and willingly sent to death by their commanders or commanders or did so voluntarily in order to achieve military success. The name of honor "Winkelried" was the most common. It was named after the legendary Swiss national hero Arnold Winkelried and was to be awarded posthumously to all fighters who had perished in the sacrifice for “Führer, Volk und Vaterland”. The first to receive this nickname were 10 young men from the K-Flotilla 361, who had announced before their deployment that they would destroy all worthwhile destinations regardless of their sailing area or the possibility of returning. None of the 10 returned from the mission. According to Friedrich Böhme, head of the command staff west of the K-units at the time, these men were worth being called "Winkelriede" because of their willingness to make sacrifices. The obituary signed by Dönitz and published in the Marine Ordinance Gazette read: ... The spirit that speaks from these men should be an example and an incentive for every soldier in the Navy to fulfill the highest duties.

There was another such, albeit claused, request to self-sacrifice on August 3, 1944, when Admiral Heye called on the negro and marten pilots deployed on that day with a so-called "cheering speech" (Anfeuerungs-FT), "Winkelriede for the to be hard fighting land front ”. It is not known whether the pilots concerned were encouraged in their commitment and willingness to make sacrifices. Interviewed contemporary witnesses after the war were silent about the dimension of the missions. Such requests have only come to light when manned torpedoes are deployed. Contrary to what Dönitz said, when the beavers and seals were later deployed , they were no longer documented.

At a presentation of the situation to Hitler on January 18, 1945, Dönitz first used the term "Sturmwikinger". In his opinion, the K-formations were only to be used as storm vikings “because of the long distances [to the target].

During an interrogation after the war, he said that the K-formations had been viewed as "consumption" from the outset. They were cheap to make and quick to replace. Heye made a similar statement in his 1955 publication, in which he stated that the ideal lone fighter is the man who acts on his own initiative, even without orders, in the sense of leadership (e). Even if British post-war reports expressly underline the self-sacrifice dimension of the K-units, it cannot be abstracted and also cannot be projected onto all weapon systems of the K-units. This also applies to Dönitz's statements. It is no longer possible to precisely determine whether the enormously high numbers of casualties of this time were based on an actual will to sacrifice or simply on the inadequacy of their weapons and the intensity of the fighting. It was probably a combination of all three factors.

Mission evaluation

From a military point of view, the K units did not pose a serious threat to Allied shipping in the Mediterranean or the English Channel at any time. Their missions were too weak and without the necessary intensity. Only the combat swimmers of the Kriegsmarine and their naval task forces were able to solve the combat missions assigned to them satisfactorily. The reasons for the failure of the concept of small combat units are diverse.

The OKM initially designed the units as a purely defensive force, but tried to use them more aggressively as conventionally large submarines as well as speedboats and torpedo boats due to the tumultuous events in Italy and Normandy. Due to the inadequate range and armament, this concept could hardly be implemented in practice with the available resources. The naval historian Werner Rahn is of the opinion that the use of small arms was practically useless compared to its military benefit. After the war, Heye also recognized that the small weapons of any kind could at best only be a supplement to the regular naval weapons, but never replace them. At best, they would have been suitable for splitting or binding the enemy's stronger naval forces.

Even the hoped-for psychological effect on the enemy did not materialize. The K-means were not magic bullets , nor did they create any shock effects such as the first appearance of the Tiger tanks among American army soldiers. The British experience with the “Decima MAS” in the Mediterranean in 1942 and 1943 had negated the element of surprise. An effective fight against small weapons of any kind was possible through massive escort protection, heightened vigilance and targeted barrage. Where the Allies encountered German K units, they did not evade them, but instead placed and destroyed them. The British fighter planes in particular achieved high numbers of seals and beavers being shot down . Heye had already stated in August 1944 that the surprise effect and thus the military success depended solely on opposing the enemy as many different types of weapons as possible in small series. As soon as he had adjusted to this or that, the K-weapon lost its shock effect and had to be replaced by a new weapon system. Thus, the enemy should practically be put under constant pressure to adapt, which should enable the German forces to achieve their military goal. The industry could not or would not follow Heyes' concept despite a sufficient number of designs and focused on the series production of standard models, which resulted in a higher output of boats. Because the Allies knew their opponents relatively precisely, they were able to optimize their defensive measures. However, General Dwight D. Eisenhower later noted:

"It seems likely that if the Germans had used these weapons six months earlier than they did, our invasion of Europe would have proven extremely difficult, perhaps impossible."

The decryption of the Enigma key by British cryptologists in Bletchley Park made the use of the K-associations even more difficult. These used the "Eichendorf Code" within their machine, which the British Admiralty called "Bonito". However, it took the British scientists between 2 and 14 days to decrypt incoming K messages, so that often no operational advantage could be derived from them. In addition, the K-Associations largely kept radio silence or never gave exact information on upcoming or ongoing operations in their messages. The Allies therefore limited themselves to a “general warning”: SUB SUB SUB (SUB = Submarine, U-Boot).

In conclusion, it can be stated that the K-units of the Kriegsmarine were deployed too early and potentially effective models such as the seal arrived too late to be able to have any real influence on the war. Their only success was the creation of a strong diversification effect among the Allies, who employed up to 500 boats and 1,500 aircraft in the hunt for small weapons in the Scheldt estuary alone. As von Dönitz had already stated in 1944, they were therefore not destroyers of ships, but rather served to bind ships and air forces. At most the new models in development at the end of the war, in which the deficiencies of the predecessors were tried to be remedied as much as possible, could possibly have led a more effective naval war. However, it remains questionable whether this would have had any influence.

Simulation games and global terror

Despite or precisely because of the increasing number of defeats on all fronts, the Navy developed utopian simulation games , similar to the American bomber project , which were intended to make global operations and attacks possible far beyond the borders of Europe. Technical advances, such as that of the revolutionary Walter drive , may have influenced this. All K-means in the front line were continuously developed, so u. a. the Biber II and the Biber III as well as the Seal II , which, from a purely technical point of view, could reach ever larger areas of application.

Even after the Allied invasion of Normandy, the German secret service developed plans to sabotage the England-France oil pipeline that had been laid in the course of Operation Pluto . The K-formations' micro-submarines were to be used here to search the seabed on the suspected pipeline route using hooks. The pipeline discovered in this way was to be blown up with Nipolit. However, the plan was quickly abandoned. Instead, combat divers should drill into the pipeline and infiltrate a corrosive chemical liquid. This should be colorless and odorless and ensure that engines started with it would be destroyed. Ideally, this should affect thousands of vehicles.

The planned use of a single beaver in the Suez Canal was one of the other concepts for the use of small weapons . He was to be flown on board a BV 222 to the target area and there, without the possibility of returning, torpedo and sink the first merchant ship in the canal. This wreck was supposed to block the Allied supplies through the Suez Canal for weeks and thus give the German front in Italy a respite. The company failed not because of the will of the OKM, but because of the destruction of the engines of the planned BV 222, which had been dismantled for a final check before the start of operation and which were destroyed in a bomb attack on the factory hall.

Other simulation games provided for eight to ten combat swimmers to be released in the New York harbor so that they could damage or sink ships there by means of explosive fishing (mines). Even the destruction of the locks of the Panama Canal was planned, as well as the dropping of several lens blasting boats using the Go 242 into the bay of Scapa Flow in order to attack the British fleet there. No nation on earth should be safe from German attacks. On a secret mission at the end of January 1945, the war fishing cutter KfK 203 disguised as a Norwegian broke out from Harstad ( Norway ) to head for its destination, the Indian Ocean and the Persian Gulf . On board were 12 combat swimmers from the K associations. A few weeks later, the OKM received the short signal from the war fish cutter on the west coast of Africa. After that, its track is lost.

The last operational order reached Dönitz in mid-April 1945, when Hitler requested a bodyguard specially available for him, which should consist of tried and tested soldiers from the K units. The background to this was Hitler's increasing distrust of his SS Leibstandarte . On April 27, 1945, 30 K fighters gathered at the Rerik airfield to be flown to the burning Berlin. However, the reconnaissance aircraft flying in a Ju-52 that was made available no longer found a safe airfield over Berlin. A landing on the east-west axis in front of the Brandenburg Gate seemed possible, but massive Soviet flak fire forced the pilot to turn back. Another reconnaissance attempt was made on April 28, 1945, but it showed that the intended runway was littered with impact craters and did not guarantee a safe landing. A parachute jump on April 29, 1945 would have been almost impossible due to the thick smoke from the many burning houses. The plan was postponed again for a day and canceled after Hitler's suicide on April 30th as the men were no longer needed.

Influence on later units

After the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht on May 8, 1945, numerous small seal- type submarines were spoiled by British or Soviet war by the middle of the month . At least four seals were also confiscated from the French Navy . In addition, all construction documents that were stored in the development department of the K-associations were secured. After the British had convinced their American allies of the value of German small arms, the United States Navy arranged a demonstration of the devices in American waters. To this end, seven former seal pilots of the K associations traveled to Florida at the end of May 1945 . In mid-June 1945, a beaver , a newt , a shark and a seal were demonstrated to representatives of the US Navy in Fort Lauderdale . For their part, five Italian members of the “Decima MAS” demonstrated assault boats and SLCs. The seal was sunk off Florida during artillery firing exercises after the test series was completed. Nothing is known about the whereabouts of the boats and any subsequent use by the Allies. With the dissolution of the Wehrmacht on August 26, 1946, the last remnants of the K-units of the Navy also disappeared. Their basic concept was later taken up in a modified and adapted form in the German Federal Navy and in the People's Navy of the GDR . The German Navy owned various small submarines, including submarine class 202 , with displacements of 60, 100 and 180 t, as well as combat swimmers and weapon divers . For its part, the Volksmarine founded the special department of the “Combat Swimmers of the NVA” and the 6th Flotilla , which served as an offensive speedboat association under the Warsaw Pact . The 6th Flotilla also used small torpedo speedboats of the types Iltis and Forelle , which could be regarded as "small weapons".

literature

- Lawrence Paterson: Weapons of Despair - German combat swimmers and micro-submarines in World War II. 1st edition. Ullstein Verlag, 2009, ISBN 978-3-548-26887-3 .

- Harald Fock: Naval small weapons . Nikol publishing agencies, 1997, ISBN 3-930656-34-5 .

- Helmut Blocksdorf: The command of small combat units of the navy. 1st edition. Motorbuch Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-613-02330-X .

- Werner Rahn : German Marines in Transition - From a Symbol of National Unity to an Instrument of International Security . R. Oldenbourg, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-486-57674-7 .

- Cajus Bekker : lone fighter at sea. The German torpedo riders, frogmen and explosive device pilots in World War II . Stalling-Verlag, 1968.

- Cajus Bekker: ... and yet loved life. The exciting adventures of German torpedo riders, frogmen and explosive devices . Adolf Sponholtz Verlag Hannover, 8th edition 1980 (first edition 1956), ISBN 3-453-00009-9 .

- Paul Kemp: Manned torpedoes and small submarines . Motorbuch Verlag, 1999, ISBN 3-613-01936-1 .

- Martin Grabatsch: torpedo rider , storm swimmer , explosive boat driver . Welserfühl Verlag, 1979, ISBN 3-85339-159-X .

- Helmuth Heye: Naval small weapons. In: Defense. Issue No. 8, year 1959.

- Jürgen Gebauer: Marine Encyclopedia . Brand Publishing House, 1998, ISBN 3-89488-078-3 .

- Richard Lakowski: Reichs- u. Navy - Secret 1919–1945 . Brand Publishing House, 1993, ISBN 3-89488-031-7 .

- Klaus Matthes: The seals - small submarines . Koehler Verlag, 1996, ISBN 3-8132-0484-7 .

- Manfred Lau: Ship deaths off Algiers . Motorbuch Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-613-02098-X .

- Michael Welham: Combat Swimmer - History, Equipment, Missions . Motorbuch Verlag, 1996, ISBN 3-613-01730-X .

- Michael Jung: Sabotage under water. The German combat swimmers in World War II . Mittler, 2004, ISBN 3-8132-0818-4 .

Web links

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Werner Rahn: German navies changing - From international symbol of national security unit for instrument . R. Oldenbourg, Munich, 2005, ISBN 3-486-57674-7

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v Harald Fock: Marine-Kleinkampfmittel . Nikol publishing agencies, 1997, ISBN 3-930656-34-5

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i Helmut Blocksdorf: The command of the small combat units of the Navy , 1st edition. Motorbuch Verlag, 2003, ISBN 3-613-02330-X

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Cajus Bekker: ... and yet loved life. The exciting adventures of German torpedo riders, frogmen and explosive devices . Adolf Sponholtz Verlag Hannover, 8th edition 1980 (first edition 1956), ISBN 3-453-00009-9

- ^ Gerhard Wagner: Lectures of the Commander-in-Chief of the Navy before Hitler 1939–1945. On behalf of the Working Group for Defense Research . JF Lehmann Verlag, Munich 1972, p. 570

- ^ Siegfried Beyer, Gerhard Koop: The German Navy 1935-1945. Volume 3, Podzun-Pallas Verlag, ISBN 3-89350-699-3 , p. 86

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n V. E. Tarrant: The last year of the German Navy May 1944 to May 1945 . Podzun-Pallas Verlag, 1994 edition, ISBN 3-7909-0561-5

- ^ A b C. E. T. Warren and James Benson: ... and the waves above us - the British torpedo riders and micro-submarines 1942/45 . Publishing company Jugenheim Koehler 1962

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Cajus Bekker: Lone fighters at sea: the German torpedo riders, frogmen and explosive devices in the Second World War . Stalling, Oldenburg 1968

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l Lawrence Paterson: Weapons of Desperation - German combat swimmers and micro-submarines in World War II. 1st edition. Ullstein Verlag, 2009

- ↑ Janusz Piekalkwicz: The Second World War . Weltbild Verlag, 1993, ISBN 3-89350-544-X , p. 1026

- ^ A b Cajus Bekker: Battle and sinking of the navy . Adolf Sponholtz Verlag Hannover 1953

- ^ William L. Shirer: The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich . Simon and Schuster 1960, p. 1138

- ^ War diary of the Naval War Command, Part A, Stabsquartier Berlin, microfilm T1022, 3/8/44

- ^ Peter Padfield: War Beneath the Sea: Submarine Conflict During World War II . Wiley Verlag, 1998, ISBN 0-471-24945-9 , p. 456

- ↑ Compare the ZDF documentary series, end sequence

- ↑ Control Council Act No. 34 of August 20, 1946

Remarks

- ↑ With regard to small submarines, the Marina Militare had repeatedly unsuccessfully proposed to the Kriegsmarine to carry out developments together with the Germans, since they already had experience with the construction and use of such boats (cf. small submarine type CC et al ).

- ↑ There are no reports on drug addicts or deaths as a result of drug use within the K associations.

- ↑ The award resulted in the future permanent staff of the flotilla being recruited exclusively from young men of the Hitler Youth .

- ↑ They were the first lieutenant to the sea Winzer and Schiebel, lieutenant to the sea Hasen, the chief ensign to the sea Pettke, the chief helmsman Preuschoff, helmsman's mate Schroeger, machine mate Guski and the two sailors Roth and Glaubrecht. The tenth man is not known by name.