Luise Duttenhofer

Christiane Luise (Louise) Duttenhofer b. Hummel (born April 5, 1776 in Waiblingen , † May 16, 1829 in Stuttgart ) was one of the most important German silhouette artists . Her work shows Biedermeier , classicist and romantic features. Their paper cuttings made them known far beyond Württemberg's borders. After her death, it was quickly forgotten and was only rediscovered at the beginning of the 20th century. Her husband was the engraver Christian Friedrich Traugott Duttenhofer . Like his father, her son Anton Duttenhofer was also a copperplate engraver.

Life

The most important biographical source is the necrology of Gustav Schwab, besides the few letters left by the Duttenhofer are an important source about their private life.

origin

Luise Duttenhofer was born on April 5, 1776 in Waiblingen in what was then the rectory at Kurzen Strasse 40. She was the daughter of the Protestant deacon Georg Bernhard Hummel (1741–1779) and his wife Louise Hedwig Hummel nee. Spittler (1747-1824). Both parents came from Wuerttemberg Protestant pastor families. The maternal grandparents belonged to the upper middle class. The grandfather Jakob Friedrich Spittler (1714–1780) was a canon preacher in Stuttgart, consistorial councilor, prelate and abbot of Herrenalb and with the pastor's daughter Johanna Christiana Spittler born. Married Bilfinger (1724–1796). They had five children, in addition to the daughter four sons, including the Württemberg State Minister Ludwig Timotheus Spittler (1752-1810).

childhood

Her father died three years after Luise's birth, and the mother and her only child moved to Stuttgart to live with their parents. One year later, in 1780, her grandfather died and Luise grew up alone with her mother and grandmother.

As a child, Luise drew portraits and caricatures and made small clippings with scissors, among other things. a. also cuts with Gothic ornaments, which she memorized when attending church services and which can also be found in her cuts in later years. In adolescence she received drawing lessons at the suggestion of her great-uncle Heinrich Christoph Bilfinger (1722–1788), professor of morality at the high school in Stuttgart, but this did not satisfy her for long because the pupil soon surpassed the teacher. The lessons should not give her any professional qualifications either, since women had to limit themselves to “typically female” skills. In addition to the usual “housewife subjects”, she was also allowed to learn French.

youth

In the 18th and 19th centuries it was almost impossible for a woman to work as a visual artist. Counterexamples such as Angelika Kauffmann , Anna Dorothea Therbusch and Ludovike Simanowiz confirm the rule. The former two were fortunate that they came from a family of painters, and Simanowiz grew up in a culturally open-minded environment and received private painting lessons from a Württemberg court painter. Both of Luise Duttenhofer's parents, on the other hand, came from pietistic pastor families and refused the eighteen-year-old her consent for an academic artistic training. Luise now shifted her artistic activities mainly to cutting scissors, an activity that women were allowed to do as a hobby. In addition, she eagerly read books on history, archeology, mythology and the fine sciences and thus self-taught acquired extensive background knowledge for the practice of her art. During her life, however, she should not forget that she had been denied artistic training. She repeatedly complained in personal conversations, in letters and in satirical silhouettes about this unjust treatment.

marriage

On July 29, 1804, at the age of 28, Luise Duttenhofer married her cousin, the two years younger copper engraver Christian (Friedrich Traugott) Duttenhofer in Heilbronn . Christian was born in Gronau. His father Christian Friedrich Duttenhofer was a pastor there and was transferred to Heilbronn a year after Christian's birth, where Christian grew up and lived until his marriage. Although he also came from a pastor's family, Christian Duttenhofer, unlike his wife, was not denied artistic training, perhaps because he was a man, and he was allowed to study at the art academies in Dresden and Vienna. He then worked from 1803 to 1804 in Paris as a reproduction engraver for the Musée Napoléon (today's Louvre).

Rome trip

After the wedding, the couple went on a study trip to Rome , where they stayed until September 1805. Christian's younger brother, the architect Carl (Rudolph Heinrich) Duttenhofer (1784–1805), joined them later and shared the apartment with them in Via delle Quattro Fontane 140. Her Roman circle of acquaintances included the German painters Eberhard von Wächter , Gottlieb Schick , Joseph Anton Koch , Johann Christian Reinhart and Angelika Kauffmann . In Rome, Luise received many suggestions that were later reflected thematically and formally in her work. "Unfortunate family events" and "the French war of 1806 caused the couple to leave the land of the arts after a stay of little more than a year." The unfortunate family events mentioned by Gustav Schwab in the necrology were two deaths The couple's first child, Carl Aurel, who was still born in Rome, died soon after the birth. Christian's brother Carl, who had traveled to Rome with the couple, died at the age of only 21 on August 23, 1805, also in Rome.

Life in Stuttgart

children

After returning from Rome Luise and Christian Duttenhofer lived in Stuttgart, as people said, “as a dangerous couple; he stabbed and she cut ”. The marriage had seven children between 1805 and 1818, five sons and two daughters. Four children died in infancy: Carl Aurel (* † 1805), Peter Alexis (1814–1815), Kornelie Georgine (* † 1816) and Emil Georg Albert (1818–1819). One daughter and two sons reached adulthood: Marie (Luise) (1807–1839), Fritz (Friedrich Martin) (1810–1859) and Anton (Raphael) (1812–1843).

Anton Duttenhofer (1812–1843) became a copperplate engraver like his father, Friedrich Martin became a government horse doctor and professor, and Marie married Christian Friedrich August Tafel (1798–1856), a lawyer from Öhringen .

Married life

Gertrud Fiege aptly characterized the relationship between the two spouses: “He was capable in his field, but not outstanding, not an artist with his own ingenuity, but instead reproduced works of others in copperplate engraving - an important and necessary task before the invention of photography and modern printing techniques . His wife, on the other hand, had ideas pouring in; she was imaginative, original, creative. Apparently she was changing in her moods. Occasionally she could hurt with biting humor, at other times she withdrew into herself, oppressed by depression and complexes, at the same time loving and communicative. In letters she called her husband the "family friend" and wrote about him in a perhaps resigned and mocking, but ultimately probably positive tone. "

Christian seems to have been a sedate man whom nothing could easily upset. In the snail caravan silhouette, Luise tellingly caricatures her husband as a snail knight, in another she “inspires” her husband, who “depresses” her by attaching Hermes wings to his heels.

Luise, on the other hand, was lively and active, and it was she who took care of the practical aspects of life together. Her superior creativity and the predominantly reproductive activity of her husband probably led to disagreement at times. In her husband, Luise always had an example of the oppression of women before her eyes: as a man he had been allowed to pursue the career of an artist, while as a woman she had to do without it. On the other hand, Christian had to feel offended by the partial superiority of his wife in his "male honor". He reacted to it with "sarcasm" ("the last time I have just too much in my house") and so made his wife's life angry.

When Christian spent several weeks in Paris with Sulpiz Boisserée in 1820 for professional reasons , he incurred “le courroux de Madame son epouse” (the wrath of his wife) because he extended his excursion for so long. Boisserée wrote to his brother Melchior : “I also understand that the woman's influence does not leave the poor man free, and since he has nothing more to do here, but urgently has work at home for Nuremberg, etc., I can Don't hold him against his insistence. ”It took Luise almost the end of her life to find her way into her unchangeable lot. In a letter to a friend a year before her death, she wrote: “Because I was unlucky enough to be shy, now I've been patiently laying out some things, and only the lucky one can shake hands, I'm not quite finished yet, but I am so that I can contribute something to the joy again. Man has to go through some epochs until he has learned to endure, to love, with calm and spiritual sense. "

Social life

The family lived in Stuttgart's “Reichen Vorstadt” at Casernenstrasse 10. Wolfgang Menzel , a literary critic from Vormärz , who bought the “nice house” in 1833, reveled in the highest tones: “It was completely free in the background of a sunlit garden, and vines climbed up to the windows of my study, almost always full of sweet grapes in autumn. ”A few steps further on at Casernenstrasse 20 stood the house of court and domain councilor Johann Georg Hartmann , whose wife Juliane nee. Spittler was related to Luise's mother. The Hartmannsche Haus was a center for social gatherings for the educated Stuttgart bourgeoisie and for strangers traveling through. The Duttenhofers also belonged to Hartmann's circle and met many prominent Swabians and non-Swabians there, almost all of whom Luise Duttenhofer took under the scissors.

The educated middle class of Stuttgart was one big family in which everyone knew everyone. Embedded in this social environment, there were many contacts, including with prominent poets and artists. Ludwig Uhland , who lived in Stuttgart from 1812 to 1830, mentions nine meetings with the Duttenhofers in his diary for the years 1810–1820 (mostly he was invited to dinner). There was a friendly relationship with the families of the poet-lawyer Karl Mayer , whom Luise dearly adored, and the pastor-writer Gustav Schwab , who wrote the necrology on them after Luise's death.

Luise was friends or at least well known with the epigrammatist Friedrich Haug , the art lover Heinrich Rapp , the editor of the Morgenblatt for educated estates Ludwig von Schorn and with the famous sculptor Johann Heinrich Dannecker , in his antique hall, or as she said: "Lumber Chamber" , one could “not draw properly”.

The Duttenhofers also associated with the brothers Melchior and Sulpiz Boisserée and Johann Baptist Bertram, who exhibited their unique Old German and Old Dutch collection of paintings in Stuttgart from 1819 to 1827. Her husband was involved in the large copperplate engraving Sulpiz Boisserées about Cologne Cathedral. Luise Duttenhofer adored the now forgotten poet Friedrich von Matthisson in her girlhood, later she caricatured him in some of her silhouettes because of his submissive attitude towards King Friedrich I. In any case, she showered Matthisson, who was also the godfather of one of her children, with silhouettes dedicated to him, which have come down to us in the two Matthisson albums. Luise was an "intimate friend" of Klara Neuffer, who was married to an uncle Eduard Mörikes . Mörike probably also became known through “Tante Neuffer” with the paper cuttings of the “famous Madam Duttenhofer”, which he found “like all the similar compositions by this extremely witty woman - admirable” and original.

Last year of life

In November 1828 Luise and Christian Duttenhofer went on a study trip to Munich with their daughter Marie and their son Anton. There Luise eagerly visited the library, the picture gallery and the copperplate cabinet; As a woman, however, she was forbidden to enter the antique collection. From Munich she wrote to Stuttgart: “With tears in my eyes I walked through the halls of the academy where schoolchildren were sitting. Why wasn't such a thing granted to me? so my youth lay before me longing for art lessons. Now it is too late, as much as I line up time and eternity, the professor doesn't do it and laughs at old Thadädl . "

The family returned prematurely from the trip that was planned for six months because Luise fell ill in Munich. She died “prematurely” at the age of only 53 on May 16, 1829 in Stuttgart, without being able to implement the wealth of newly gained ideas in her work. Her husband moved back to Heilbronn in 1834, where he committed suicide at the age of 68 due to an incurable disease.

Luise Duttenhofer had her whole life struggled with her fate, which denied her the career of an artist; Nevertheless, she has given posterity rich gifts and has been posthumously recognized as an important artist in our time.

tomb

Luise Duttenhofer was buried on May 16, 1829 in the Hoppenlaufriedhof in Stuttgart . However, her grave was undetectable until at least 1967. Today's grave, which bears her name, can be found if you go to Wilhelm Hauff's grave using the information boards and follow the path to the left for a few steps. There are two gravestones to the left of the path:

- Directly on the way is the grave of Luise's mother with an approximately 1.20 meter high sandstone stele, the inscription of which is heavily weathered, but still as "Louise Hedwig [Hum] meL, geb. Spittler widowed l [icht] helper since 1779. born […] 1747. [d. d. 17. May 1] 824. “Can be deciphered.

- Next to it, a little further from the path, you come across an approximately 1.65 meter high grave monument with an old base and a restored stele. This bears the inscriptions Luise Duttenhofer geb. Hummel, a shear cutter and Karl Friedrich von Duttenhofer , Colonel and Head of Hydraulic Engineering (a cousin of her husband and a famous hydraulic engineer in his day), the names of his wife and two sons are carved on the back. Manfred Koschlig and Hermann Ziegler ("the best connoisseur of the Hoppenlau cemetery") could not find any inscriptions for Luise Duttenhofer on personal inspection in 1967. Apparently the inscription was added during the restoration.

plant

Luise Duttenhofer was a wife, mother and housewife. In addition to her domestic duties (in which she was supported by the staff) and her participation in social life, she still found time for her art of paper cutting, in which she achieved an unprecedented level of mastery. While most of her contemporaries, as amateurs, were content with cutting out silhouettes or with often absurd and traditional themes and patterns, Luise embarked on her own new path.

Luise Duttenhofer has passed down more than 1,300 silhouette cuts to posterity. In addition to miniatures that are only a few centimeters high and wide, she has created many cuts in single or double postcard size. The smallness of the works leads one to disregard the achievement of their creator, large formats have a much better effect on the audience. Goethe's statement “only the master shows himself in the limitation” applies perfectly to her works : Despite the limitation to small formats, the non-colors black and white and only two dimensions, she has created a small universe that is creative and original , filigree and well-considered compositions combine their observations of the real world with allegorical, mythological and ornamental accessories. She uses her mother's wit to achieve humorous or satirical effects, which (almost) never let the compassionate and soulful woman behind it be missed. The interior design of some cuts, especially the tapering tile patterns, even defies the two-dimensional medium from a perspective effect. All in all: a great artist in a small area.

The artist's work cannot be assigned to a single art-historical style: “The multitude of family scenes, interiors, children and flowers and the restriction to the simple and often to the private correspond to her role as a woman in her time and social class. It is contestable, therefore, as is often the case, to assign it to the Biedermeier period. Mythological themes and ancient ornamentation in her work refer to classicism, the poeticization of reality and mystifications, along with her enthusiasm for the Gothic show romantic influences. Stylistically, it is closest to the circle of classicism, especially Swabian classicism, in which the middle-class family is an essential component. "

subjects

In addition to silhouette portraits and full-length figures, Luise Duttenhofer mostly designed scenic silhouettes, often framed by artistic ornaments, which she not only drew from the traditional fund, but also expanded them with rich floral and figurative ornaments. Their cuts are often carefully composed, and it is often impossible to decipher the meaning of a work and the hidden allusions of individual ingredients without closer knowledge of the history of its creation. Luise Duttenhofer loved the mysterious trimmings of her motifs and certainly gave her contemporaries some puzzles with her mystifications. Her rich repertoire included u. a. the following topics:

- Genre scenes from family, children's, everyday and country life

- Allegories , fairy tales, myths and sayings

- religious motifs

- Memorial sheets on the occasion of birth, death and marriage

- Flowers and animals pictures

- Masks, arabesques and grotesques

- literary cuts to illustrate poems and dramatic scenes

- humorous sheets, caricatures and satires on family members and famous people

- Vase designs

technology

Luise Duttenhofer limited herself to pure outline cuts from black paper, which she usually cut out of a folded sheet of paper in one go, so that she received two mirror-inverted copies of her cut. We owe it to this fact that one of the cuts that had been given away in many cases always remained in her possession and was thus passed on to us through the gift of her grandson Otto Tafel .

It seems that she often, but not always without a preliminary drawing, cut straight out of the scissors. Sometimes she supplemented her cuts with embossing on the reverse in order to achieve a relief effect, with internal drawing with pin pricks and with backing with colored paper. In the manner of a collage , she also put several silhouettes together to form a picture by sticking them in the appropriate order on a neutral paper background. So exist z. B. your perspective interiors from two or more cuts, whereby one section represents the patterned tiled floor, which creates the impression of three-dimensionality by tapering towards the background.

Attribution

In her unpretentious manner, Luise Duttenhofer almost always refrained from drawing her black gems with her name. In spite of this, the attribution of the paper cuttings stored in the Marbach Literature Archive is mostly unquestionable because the vast majority of them come from Luise's estate.

Dating

Only a few cuts are labeled with the year or date of creation. For some pieces, however, a terminus post quem can be determined from which they can at the earliest originate. If z. If, for example, the two silhouettes shown below (Fig. 1 and 2) should actually represent Ludwig Tieck, they were probably made in 1817 at the earliest, when Tieck visited Stuttgart for the first time. Luise could also have portrayed Tieck during his second stay in Stuttgart in 1828 or at some point in between or afterwards. Yes, it cannot even be ruled out that Tieck cut them based on an illustration before 1817. In other cases the terminus post quem is clear, e.g. B. if the cut shows a work of art or relates to a literary work. This applies e.g. B. to the illustration of Goethe's sorcerer 's apprentice and a cut with Dannecker 's statue of Christ . Goethe created his sorcerer's apprentice in 1797 and Dannecker began work on his statue of Christ in 1821, which lasted until 1832. These two cuts were created in 1797 and 1821 at the earliest.

Work title

Image 4: Ludwig Tieck and his sister Sophie, marble relief by Friedrich Tieck , 1796

Most of the silhouettes by Luise Duttenhofer are unmarked, i. H. they are not labeled in any way. If there is an inscription, it mostly does not come from Luise herself, but from her descendants. But since they probably learned from Luise herself what the cuts should represent, these designations can be regarded as secure.

The situation is different with the later work titles. Some are plausible, even if the people of the cut cannot be clearly identified by comparing their faces. The caricature Matthisson shows his king's greyhound the chamber pot entertaining the well-known, extremely corpulent King Frederick I and his most submissive subjects, the poet Matthison, who helps the king's greyhound with his business. Matthison was decried as a crawling courtier, at least since he glorified the royal bloodbath at the Dianenfest in 1812 in hymnic verses. The interpretation of the picture therefore seems entirely plausible. It can also be assumed that the former owner of the pattern, Gustav Edmund Pazaurek (1865–1935), was able to acquire his knowledge from well-informed contemporaries.

On the other hand, if one takes a closer look at some of Manfred Koschlig's (1911–1979) attributions, irresolvable doubts remain. According to Koschlig, the profile of Figure 3 “physiognomically” matches that of Figure 2 “Depicted in every detail”. He goes on to say: “The comparison of the profile line” of picture 1 with picture 2 “leaves little doubt as to the identity; the physiognomic features of both pieces also correspond to the marble relief "in picture 4 ". It is difficult to understand the identity in the two silhouette because in picture 2 the forehead is half covered by the hair and because the mouth area in picture 2 consists of only one line. It is even more difficult to compare the silhouette with the drawing in Figure 3 and the relief in Figure 4 . Since the third dimension is missing, essential details of the face cannot be found in the silhouettes. As in many other cases, one must therefore regard the attribution to Tieck as very vague. On the other hand, it has meanwhile become common practice to assign these silhouettes to Tieck, so that the work titles will still endure.

Locations

The majority of the surviving works are now in the Schiller National Museum / German Literature Archive in Marbach am Neckar . The architect Otto Tafel (1838–1914), a grandson of the artist who owned part of her artistic estate, bequeathed 337 folio sheets with around 1,300 paper cuttings, which were made in 1911 and 1933 to the Marbach literary archive in a deed of donation dated November 10, 1911 passed over the holdings of the archive. The collection is supplemented by around a dozen individual additions and 45 sections, which were given to the archive on permanent loan from the state of Baden-Württemberg in 1989.

In addition, there is a high probability that many of Duttenhofer's works - recognized or undetected - are in private ownership. Gustav Schwab already emphasized in his necrology: "Many friends in all parts of our German fatherland will, when reading these lines, bring out some beautiful souvenir from their artful hand with emotion." Fortunately, Luise made most of her cuts as double cuts, so that in As a rule, one copy remained in their possession and ended up in the literary archive via the estate.

Two albums with paper cutouts from Luise Duttenhofer were found in Friedrich von Matthisson's estate. Luise put together the first album with 47 cuts herself for Matthisson, around 1803; the other album contains about 25 cuts that Matthisson received as gifts over the years and that he or others glued into the album. In 1853 Eduard Mörike had a "large folder with black clippings from the famous Mad. Duttenhofer", which probably came from Luise's former girlfriend Klara Neuffer. Nothing is known about the whereabouts of the portfolio.

Portraits

In Stuttgart and on her trip to Rome, Luise met many celebrities whom she portrayed or caricatured in paper cutouts. The list of celebrities portrayed by Luise Duttenhofer is like a who's who of the cultural elite in Germany at the time. These included:

- the builder Friedrich Weinbrenner

- the sculptor Johann Heinrich Dannecker

- the art collectors Sulpiz Boisserée and Karl Friedrich Emich von Uexküll-Gyllenband

- the painters Philipp Friedrich von Hetsch , Angelika Kauffmann , Joseph Anton Koch , Gottlieb Schick , Gottlob Friedrich Steinkopf and Eberhard Wächter

- the philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Schelling

- the writers Achim von Arnim , Clemens Brentano , Johann Wolfgang von Goethe , Friedrich Haug , Therese Huber , Jean Paul , Jung-Stilling , Justinus Kerner , Friedrich von Matthisson , Wolfgang Menzel , Eduard Mörike , Wilhelm Müller , August Graf von Platen , Friedrich Rückert , Friedrich Schiller , Gustav Schwab , Ludwig Tieck , Ludwig Uhland and Johann Heinrich Voss

- and the publisher Johann Friedrich Cotta .

Literary paper cutting

Luise Duttenhofer also created paper cutouts to illustrate poems or individual verses or stanzas from literary sources. In one case she also contributed to the illustration of a book, to the volume of poems "Lautentöne" by Christian Gottlob Vischer.

Overview

- Cupid and Psyche (Fiege 1993, 163)

- Epistle to Exter in Zweibrücken (Rühl & Fiege 1978, 144)

- Alexis and Dora

- Charon | Charon (Fiege 1990, page 29, Goethe 1828, Dickenberger 1992, 37–39, 48–50, 68, 134–137, Rühl & Fiege 1978, page 129)

- Erlkönig (Rühl & Fiege 1978, 132)

- Faust (Rühl & Fiege 1978, 131)

- Idyll (Rühl & Fiege 1978, 130)

- Lilis Park (Pazaurek 1924, plate 22 above)

- Notes and treatises for a better understanding of the west-east divan (Rühl & Fiege 1978, 134)

- Sorcerer's apprentice (Pazaurek 1922, calendar sheet June)

- Love in the realm of death (Rühl & Fiege 1978, 151)

- The light tarpaulin of childhood limits the evening red (Pazaurek 1924, plate 22 below)

- The childhood years (Rühl & Fiege 1978, 135)

- Death wreath for a child (Rühl & Fiege 1978, 141)

- The Princes Chawansky (Rühl & Fiege 1978, 143, ( full text in the Google book search))

- Tomorrow (Rühl & Fiege 1978, 140)

- The girl from abroad (Rühl & Fiege 1978, 134; Güntter 1937, plates 22-23)

- Do you want with (Rühl & Fiege 1978, 133, ( full text in the Google book search))

- The young cowherd (Rühl & Fiege 1978, 142)

- More noble deeds arise through respect (Rühl & Fiege 1978, 138)

- Christian Gottlob Vischer

- Unknown poet

- And an angel hands him the golden fruit of paradise (Rühl & Fiege 1978, 135)

- Years escaped too quickly / The impartiality, / What between cradle and bier / Is your bliss? (Rühl & Fiege 1978, 135)

Hints:

- The following paper cuttings are arranged alphabetically according to the poet's name and the work title.

- For most of Luise Duttenhofer's silhouettes, which are often enigmatic and peppered with hidden allusions, there is no reliable interpretation. The following attempts at interpretation should therefore only serve as a suggestion for a better understanding of the pictures.

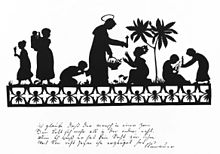

Aloys Blumauer: Creed of one who struggles for truth

Black silhouette, illustration of a stanza from the poem “Creed of Faith of a Wrestling After Truth” by Aloys Blumauer , year of origin unknown, Marbach, German Literature Archive . Literature: Blumauer 1827, page 6, Rühl & Fiege 1978, page 139. Inscription by Luise Duttenhofer: “I believe that people in one zone / light come closer than in the other; / But I know he has no right to wages / Because Rome, not Japan, produced him / Blumauer ”.

Aloys Blumauer believes that the people of the West ("Rome") can reach the Christian faith ("Light") more easily than the rest of humanity ("Japan"). To be born into a certain "zone" and therefore to find faith more easily is not a worthy merit.

Three groups of people can be seen on a base with tracery and plant ornaments. The group of three in the middle symbolizes the believing Christians, the two innocent children on the right are still half in disbelief, and in the sidelong on the left stand the pagans, who also beckon with the hope of redemption.

A saint with a nimbus protrudes from the middle group . He offers a kneeling young woman, who wears a crown on her head and holds her arms up to him, a cross, the symbol of the Christian religion, from a basket with crosses and figures of saints. A child kneels behind the saint and kisses the hem of his robe.

A stylized palm tree, symbol of resurrection and victory over death, separates the group of three from the two children on the right. The boy, sitting on the floor, is holding an ogival mini-window frame with a cross on top in his hand. The figure inside the frame is devoid of a nimbus and resembles the idols worshiped by the pagans on the left. It seems as if the boy is still addicted to superstition. A standing girl bends down to the boy and implores a saint figure.

To the left is a mother with a small child in her arms, turning to the saint. Her older daughter behind her is about to leave. Like the toddler, she holds a pagan idol figure in her hands. The children grow up in the inherited faith, but the woman's turn shows that the path to true faith is open for them too.

Matthias Claudius: The happy farmer

Black silhouette, illustration of a verse from the poem "The Happy Farmer" by Matthias Claudius , year of origin unknown, Marbach, German Literature Archive . Literature: Claudius 1976, page 362, Rühl & Fiege 1978, page 137, Schlaffer 1986, page 72-73. Inscription by Luise Duttenhofer: “And it gets difficult for me at times, / I like it! what's the harm? / M. Claudius ".

The paper cut illustrates the verse given, but makes no reference to the poem in which a happy peasant is in the foreground.

A troop of traveling people passes an old, gnarled olive tree. The procession is led by a man who is grumpy pulling a single-axle cart with two small children behind him with both hands. His little wife runs after the cart she is pushing. The man is dressed in a jacket and trousers and has a cap on his head and shoes on his feet. His wife, on the other hand, dressed in a skirt and jacket, is bareheaded and barefoot. Behind the younger one is an older couple, the children's grandparents. The old woman in an ankle-length dress, with a basket of flowers or vegetables on her head, holds a lute with a bow in one hand and leads a blind man behind her with the other. The man is short, wears a hat, coat and woolen gaiters and leans with one hand on a walking stick.

In this family picture, Luise Duttenhofer portrays three generations of poor people who drive across the country and earn a meager living with casual work and making music. The poor people are happy with their lot despite all the hardship.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

Alexis and Dora

Black silhouette based on a line of verse from the poem Alexis and Dora by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe , round medallion , 12.4 cm wide x 14.3 cm high (without inscription), year of origin 1797 at the earliest, Marbach, German Literature Archive. Literature: Goethe 1797, page 16, verse 156, Rühl & Fiege 1978, page 128. Inscription by Luise Duttenhofer: “How misery and happiness / change in loving breasts! / v. Goethe."

The quoted line of verse comes from Goethe's elegy “Alexis and Dora”, which was first published in Schiller's Musenalmanach in 1797 (Goethe 1797). The paper cut allegorizes the given line of verse, but makes no reference to Goethe's poem.

The cut consists of three parts. The inner round medallion depicts an allegory of the golden cage in the upper segment (1), in the lower segment a funeral (2) in which a drunkard is carried to the grave. The medallion is framed by a vine wreath (3) with owls and palmettes .

- (1) Allegory of the Golden Cage. An old man is enthroned in front of his desk on a recliner with legs that swing nicely backwards. He rests his head and neck on two thick pillows. The man comfortably stretches his legs, wrapped in a thick, comfortably warming blanket, under the table, one foot on a bracket that hangs down from the table top. Behind the armchair, the man's cane is leaning against the wall. The quill in his left hand is what the man writes on an inclined writing desk, while he extends his right arm for an oversized drinking cup.

- On the desk there is a high, round birdcage, the dome of which is closed with a ring-shaped hanger. A little bird sits on it, its body stretched far forward, as if it were about to fly away. It will escape to freedom, but - wrong world - in a cage a woman and her child have to endure in captivity. The young woman is sitting on a stool, her body and face averted from the old man. It is she who offers him the oversized drinking vessel, stretching her arm behind her. With one hand she embraces her little child, who is standing upright on her lap and pointing with her hand to a winged cupid standing behind the cage. She holds a rose with a stem as high as a man in her hand and knocks on the bars with the thick, richly filled rose petal.

- (2) Burial of a drunkard. The lower medallion segment shows a funeral procession. 13 men and women accompany a horned, goat-legged satyr on his last journey. Two men carry the bier with the dead follower of the wine god Dionysus on their shoulders. Seven mourners walk ahead, praying, and four mourners follow the procession.

- The writing "EST EST EST" under the funeral procession refers to the famous Italian white wine Est! Est !! Est !!! di Montefiascone , where a prelate named Johannes Fugger is said to have drunk himself to death in 1111. The funeral procession and the grape leaf flanked by two grapes under the funeral procession symbolically indicate that a great friend of the grape juice is being buried.

- (3) Vine wreath. The inner medallion is framed by a wreath of tendrils, which once again takes up the subject of death, which is posted in the lower segment of the medallion. The death symbolism of the alternating wreath of palmettes and hollow-eyed staring owls, 12 each in number, underlines the death motif. The owl has long been considered a herald of death, and in Christian tradition the palm branches symbolize the promise of paradise, the victory over death. Luise Duttenhofer connects owls and palmettes with curved tendril shoots by bending the outer feathers of the owls in a circle and transferring them to a neighboring palmette stolon.

As with many of her silhouettes, Luise Duttenhofer poses a number of riddles here, so that several interpretations are possible. We don't know when the cut was made, and we don't know why. If one uses the line of verse “How sadness and happiness / change in loving breasts!” As a basis, one can assume that a young woman was married to a wealthy older man who was perhaps an important writer. He keeps her and the child in a golden cage, which restricts their freedom but also protects them from the outside world. The man is too fond of wine, and she has to watch him drink himself to death, yes, against her will, she has to give him a helping hand. The blooming life knocks on the cage in the shape of the putto with the rose, but she remains locked out of the life outside. Fate takes its course and the man perishes of his addiction. The young widow and child remain lonely and without male support.

With Duttenhofer's penchant for mystification, it is certainly no coincidence that some mystically significant numbers are embodied in the silhouette: 1 vine leaf, 2 grapes, 3 × EST, 4 mourners behind, 7 mourners in front of the funeral procession, 12 owls and 12 palmettes, 13th century Mourners overall.

Formally, the silhouette is similar to the "four play plates" that Luise Duttenhofer created as designs for play plates, and to some other silhouettes in the form of framed round medallions.

Christian Gottlob Vischer

Literature: Koschlig 1960, page 126, Vischer 1821.

In contrast to many other silhouette artists, Luise Duttenhofer usually did not work as a book illustrator. In one single case, however, she and her husband Christian Duttenhofer supplied vignettes for the volume of poems "Lautentöne" by Christian Gottlob Vischer, a poet now forgotten (Vischer 1821). Her husband contributed a copper engraving and she made five silhouettes, which Johann Wilhelm Gottlieb Pfnor made as woodcuts. Pfnor reproduced the silhouettes partly true to the original, partly alienated by drawing.

Ode to Crown Prince Wilhelm I of Württemberg

|

Woodcut by Johann Wilhelm Gottlieb Pfnor after a black silhouette by Luise Duttenhofer, entry vignette for the poem “Ode to His Royal Highness the Crown Prince of Würtemberg”, year of origin 1821. Literature: Vischer 1821, page 14.

Two hovering guardian angels hold a bowl with victory palms over a lion, the heraldic animal of Württemberg. The ode was written in December 1813, when the later King of Württemberg, Wilhelm I, took to the field as commander-in-chief of the Württemberg army against Napoleon and contributed to his defeat and abdication in several battles between January and March 1814. |

Ode to friendship

| Woodcut by Johann Wilhelm Gottlieb Pfnor after a black silhouette by Luise Duttenhofer, entry vignette for the poem "Ode to friendship", year of creation 1821. Literature: Vischer 1821, page 59.

A man with curly hair and a beret on his head, wearing a short jacket and trousers, is standing in a meadow in front of a bush. He leans on a man-high wooden stick on which his dog, “man's best friend” happily jumps up. Luise Duttenhofer owned a dog named Mylord, which she loved very much. |

Reconciliation

| Woodcut by Johann Wilhelm Gottlieb Pfnor based on a black silhouette by Luise Duttenhofer, entry vignette for the poem “Cannstatt”, year of creation 1821. Literature: Fiege 1990, page 27, Koschlig 1968, page XI-XI, Rühl & Fiege 1978, page 33. Literature : Vischer 1821, page 62.

Eduard Mörike made a copy of the silhouette in 1827 and sent it to his friend Wilhelm Hartlaub (1804–1885) in a letter on May 25, 1827: “Another small supplement is the black group that I made after a silhouette of the famous Madam Duttenhofer in Stuttg [art], quickly but faithfully. It is a very lovely thought, it is supposed to allegorize the reconciliation of two children, of which the one who has offended does not want to be comforted with shame and remorse. The tree appears to be an olive . The whole thing, with such great simplicity - like all similar compositions by this extremely witty woman - is admirable! ”(Fiege 1990, page 27). The woodcut copy of the paper cut shows the original cut reversed and shortened on the sides. |

Cannstatt

| Woodcut by Johann Wilhelm Gottlieb Pfnor after a black silhouette by Luise Duttenhofer, entry vignette for the poem “Cannstatt”, year of origin 1821. Literature: Vischer 1821, page 91.

The woodcut shows the god of the Neckar in a transverse oval medallion , who lies on the river bank near Bad Cannstatt and lets the water flow from a large barrel into the river. The river god is depicted as an elderly man with a straight face, classic profile, a long, flowing beard and a well-preserved muscular body. He is naked except for the pubic area covered by a cloth. The wild hair on the head is tamed by a ribbon that ends in a screen made of bay leaves. In his right arm, which he leans on the barrel, the god holds a bundle of reeds as a scepter. He rests in the middle of an idyllic reed and flower landscape and above his head the vines of the fertile Neckar valley wind on a vine like a protective shade roof. |

Transfiguration of Müller

| Woodcut by Johann Wilhelm Gottlieb Pfnor based on a black silhouette by Luise Duttenhofer, entry vignette for the poem “Cannstatt”, year of creation 1821. Literature: Vischer 1821, page 101.

The poem glorifies the copperplate engraver Johann Friedrich Müller (1782–1816), the eldest son of the Stuttgart copperplate engraver Johann Gotthard Müller (1747–1830). His main work is the Sistine Madonna after Raphael . At the age of 32 he was appointed professor of copper engraving in Dresden, but died in Pirna / Saxony in 1816, only 34 years old. The crowned artist is enthroned in the clouds of Mount Olympus, surrounded by praising angels' heads (winged putti without bodies) and an angel floating on clouds who kneels down before the master. |

Work examples

|

"The Sorcerer's Apprentice" by Goethe

Illustration to Goethe's poem “ The Sorcerer's Apprentice ”, after 1797, dimensions and location unknown. Standing on a pedestal with a flower frieze, the sorcerer's apprentice (right) conjures the incarnate broom (“Stand on two legs, with a head on top”) to stop its activities and not drag in any more water: “Stand! stand! because we have fully measured your gifts! ”, but the overzealous apprentice lost the magic word:“ Oh, I notice! Alas! alas! I forgot the word! ". |

|

|

Mother with newborn child

Memorial sheet for the birth of a child, 17.7 × 10.5 cm, year of origin unknown, Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach, inventory number 5686. A woman who has recently given birth is sitting in bed with her baby on her lap. The infant lies on its back and holds all fours in the air. In front of mother and child, the child's guardian angel kneels on the bed and gives the child the blessing with a lily in hand, the symbol of innocence. There is a cradle in front of the bed with three guarding angels' heads buzzing over it. |

|

|

Goose girl with her flock

Rural genre scene, 13.3 × 4.1 cm, year of origin unknown, German Literature Archive Marbach. A little goose girl threatens her flock, which waddles in front of her "in single file", energetically with the raised whip. The geese are not shown as stencils, almost each one is drawn as an individual. One stretches her neck up, the other stretches it far out, one picks up a herb, the other pecks her front wife in the backside, and two geese flutter with outspread wings, as if they were about to run away. |

|

|

Matthisson entertaining the chamber pot to his king's greyhound

Satirical silhouette, around 1812, dimensions and location unknown. In her youth, Luise Duttenhofer was an ardent admirer of the poet Friedrich von Matthisson . In 1812, the fat King Friedrich I (left in the picture) organized the last of the so-called "Dianenfests" in Bebenhausen , a drive hunt for which thousands of forced laborers from all over the country first had to catch the animals and then drive them to the guns of the high masters. which they then slaughtered from the comfort of their stands. With his salacious glorification of the festival of Dianas, Matthisson challenged the caustic mockery of his admirer, who satirized the submissiveness and vanity of Matthissons in several silhouettes. |

|

|

Snail caravan

Humorous family portrait, around 1820, dimensions and location unknown. Luise's husband, Christian Duttenhofer, leads the family caravan as a sedate snail knight who pokes two fauns on the copper plate. Luise with the scissors brings up the rear of the procession, but she has the reins (of the rocking horse) in her hand, in between (from left to right) Cupid with an arrow, a crouching cat, a prancing juggler, daughter Marie with a basket of flowers, a flying cupid and the sons Anton and Fritz on the rocking horse. |

|

|

The hope

Religious motif, 9.2 cm high, year of origin unknown, German Literature Archive Marbach, inventory number 5699. According to Gertrud Fiege, “Luise Duttenhofer found a completely independent visualization for the representation of one of the three theological virtues, hope. She gave the anchor, symbol of hope, to an angel with a - surely good - star above it. The angel holds the anchor like a pendulum. It becomes clear: Hope wavers. But the angel arrests him with his foot - he holds hope. With his free hand he points to the anchor: It is not he and his behavior that are important, but hope as such. The artist has dressed this profound thought, which contains a warning, in a graceful, amiable form and has given the heavenly messenger with the childlike profile and elegantly shaped wings something playful. " |

|

|

Grotesque mask amphora

Vase design, dimensions, year of creation and location unknown. The amphora stands on a foot decorated with owls, on which the vase belly, decorated with a leaf frieze, rests. Two grim masks with wide open mouths form the handles. The vase ends in a terrifying mask with rich leaf tendril decorations on the forehead, slanted almond eyes, flaring nostrils and a grotesquely thick mouth bulge. Luise's work contains a whole series of vase designs, often in the form of segmental arches or friezes. At least one vase was made in the Ludwigsburg porcelain factory . Her husband published a series of booklets in 1810/1811 under the title Ideas for Vases , which "has the purpose of providing art lovers with a pleasant enjoyment through diverse fantasies in the field of ornamentation". One can assume that Luise, if she wasn't the initiator of the series, at least contributed drafts. |

|

|

Heinrich Rapp, proclaiming the fame of his brother-in-law Dannecker as the creator of the statue of Christ

Caricature, 9.8 × 9.8 cm, 1820 at the earliest, Deutsches Literaturarchiv Marbach, inventory number 1523. Johann Heinrich Dannecker , the famous classicist sculptor, worked on a statue of Christ from 1821, which lagged far behind his other works. His brother-in-law Heinrich Rapp , who acted as Dannecker's advocate, received Luise Duttenhofer's cheeky mockery in this caricature. Rapp (left) and Dannecker are both depicted as goat-footed fauns. Dannecker presents his Christ with one hand, while he holds out the other to Rapp to make a firm bond. He trumpeted the fame of his brother-in-law to the world - with a child's trumpet that makes an inappropriate noise in an inappropriate place. |

Four play plates

The four round silhouettes represent play plates. They were probably intended as designs for a four-piece play plate series. It is not known whether the designs were ever implemented.

Game plates were used in card games to place coins or tokens on them that were used in the game. Each player had a small game plate on which he kept his coins or tokens. In the middle of the table was a large game plate on which the players placed their bets. With a diameter of around 10 cm, the four game plates are roughly the size of mocha saucers and therefore represent designs for small game plates.

The mirrors of the plates are occupied by animal medallions , which are separated from the surrounding frieze by a wreath of leaves. The animal medallions show: an owl on a perch, a monkey with a mirror sitting on an arrow, a raven on a wooden branch and a cock spreading a feather. Four thematically matching scenes are depicted on the outer friezes: princely pageants (owl plate), sleigh rides (monkey plate), witch rides (raven plate) and board games (cockerel plate). The four playing card colors diamonds, hearts, spades and clubs are hidden one or more times in each of the friezes. The throat of the plate between the mirror and the flag is decorated with a wreath of leaves or flowers, which is underlaid with light blue paper.

The flag of the raven plate is covered with a surrounding frieze with scenes from Blocksberg. Each of the four Blocksberg groups shows a young couple riding through the air on a whisk or pitchfork.

reception

According to the unanimous opinion, Luise Duttenhofer is one of the most important German paper cutting artists.

Lifetime

During her lifetime, Luise was represented twice with paper cutouts in the Stuttgart art exhibitions of 1812 and 1824, and the morning paper for educated classes reported about it in a few friendly lines. Nothing is known about the 1813 Breslau Historical Exhibition, in which she also took part.

In 1824, at Goethe's suggestion , the Stuttgart publisher Cotta announced a competition for visual artists to depict Goethe's poem “Charon”. Luise took part, but out of competition, because she knew that she would never have been granted artist status. The painter and art writer Johann Heinrich Meyer (nickname: Kunschtmeyer or Goethemeyer), who worked closely with Goethe, was very praiseworthy at the end of his review of the submitted competition entries: “These lofty and serious endeavors are followed by an easy one cheerful sequel, a small picture cut out like a black paper, of a lady gifted with taste and artistry. ”This judgment, which was certainly inspired or approved by the poet prince, has a belittling aftertaste, even if Luise's contribution is even referred to as a“ work of art ”in the following.

19th century

Many contemporaries were enthusiastic about the products of Duttenhofer's wonder scissors. The epigrammatist Friedrich Haug , with whom she was friends, dedicated several of his epigrams to her, e. B. “I am very much afraid of the Parzen's scissors ; / Yes, female Hogarth , yours is more ”. Gustav Eduard Mörike speaks repeatedly in his letters of the "famous Madam Duttenhofer" and he finds "all the similar compositions by this extremely witty woman - admirable!" Gustav Schwab already paid the highest praise to Luise Duttenhofer in his necrology : "This art of shadow cuts [...] was subsequently raised from the childish artificiality and tastelessness of earlier times to a new subject in the visual arts, in which it achieved so much, that these achievements as well as Berner Mind's cat drawings, the Cariera Rosalba pastel paintings, Petitots and Jaquotot enamel painting, and similar limited branches of art, as, albeit in a narrow circle, highly peculiar and excellent appearances, will not be without lasting recognition in the future . “Gustav Schwab's assessment has not lost any of its validity to this day. His assignment of the paper cutting to the "limited branches of art" still applies and explains why the small-scale formats have a much more difficult time being recognized as works of art than large paintings or sculptures, for example. In fact, scissors cutting was not considered an art during Luise's lifetime, and when the name Duttenhofer was mentioned, her husband, the engraver, a professional artist, was mentioned first, and Luise was mentioned only in passing, if at all. Up to the end of the 19th century, Luise was either ignored in the biographical reference works or presented as insignificant compared to her husband.

20./21. century

Soon after her death, the artist Duttenhofer fell into oblivion, not least because almost all of her works were privately owned and because paper cutting was still not considered a recognized art form. Even if important artists such as Philipp Otto Runge , Moritz von Schwind , Adolph Menzel and Henri Matisse dealt with scissor cutting in the 19th and 20th centuries, this did not lead to a corresponding recognition of this branch of art.

The rediscovery of the Duttenhofer is thanks to the art historian Gustav Edmund Pazaurek (1865–1935). In 1908 he held her first solo exhibition as director of the State Trade Museum in Stuttgart . He continued to promote memories of Duttenhofer's work through an article in Westermann's monthly magazine (1909), a literature and art calendar (1922) and a first illustrated book (1924). After Otto Tafel bequeathed a large collection of Duttenhofer's works to the Marbach Literature Archive in 1911 and 1933, the archive directors Otto Güntter (1858–1949) and Manfred Koschlig (1911–1979) contributed to the further popularization of their work through relevant publications. On the 150th anniversary of her death, the second solo exhibition for Luise Duttenhofer took place in the literature archive in 1979. In literary terms, too, she is gaining increasing recognition in books, essays and mentions or through the depiction of her works, also from specialist science. Most of her works, however, are not accessible to the general public because they are stored in the literature archive. A separate museum or at least an exhibition room dedicated to Luise Duttenhofer could help.

Logo of the Osiander bookshop

Postage stamp for the 200th birthday of Clemens Brentano, designed by Elisabeth von Janota-Bzowski

Luise Duttenhofer is not a popular artist who would have found a broad place in the vocabulary of the advertising and fashion industry, but at least three of her paper cuttings have become known to broader circles as advertising logos or as postage stamps (although very few people know who the template came from) . The Stuttgart Antiquarian Book Fair, which turned fifty in 2011, uses, slightly alienated, the reading Ludwig Tieck as a “figurehead” for its publications. The Osiander bookstore in Tübingen chose the cut of Ludwig Uhland, who also reads, as its logo, if only as a cutout. After all, the Brentano pattern served as a butterfly as a template for the commemorative stamp for Clemens Brentano's 150th birthday in 1978.

literature

The specified number of plates and illustrations only takes into account those with works by Luise Duttenhofer.

Biographical reference works

- Duttenhofer, Christiane Luise . In: Ulrich Thieme (Hrsg.): General Lexicon of Fine Artists from Antiquity to the Present . Founded by Ulrich Thieme and Felix Becker . tape 10 : Dubolon – Erlwein . EA Seemann, Leipzig 1914, p. 237 ( Textarchiv - Internet Archive ).

- David EL Thomas: Duttenhofer, (nee Hummel), Christiane Luise . In: General Artist Lexicon . The visual artists of all times and peoples (AKL). Volume 31, Saur, Munich a. a. 2001, ISBN 3-598-22771-X , p. 292 f.

life and work

- Max von Boehn: Miniatures and Silhouettes. A chapter from cultural history and art. Munich 1917, pp. 191–193, 198–199, 3 illustrations.

- Walter Hagen: Manfred Koschlig: Die Schatten der Luise Duttenhofer [Review of Koschlig 1968]. In: Journal for Württemberg State History 28.1969, pp. 472–474.

- Friederun Hardt-Friederichs: Meeting: Luise Duttenhofer and Therese Huber. 2007, 2 images readingwoman.org .

- Ursula and Otto Kirchner: On land, on water and in the air. The motif of locomotion in Luise Duttenhofer. In: Ursula and Otto Kirchner (editor): Unterwegs. How and where The motif of locomotion in the paper cut. Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-940061-40-9 , pp. 6-15.

- Manfred Koschlig: Luise Duttenhofer in personal reports. In: Stultifera navis 10.1953, pp. 14–30, 20 illustrations.

- Manfred Koschlig: Some communications on the essay about Luise Duttenhofer. In: Stultifera navis 11.1954, pp. 50-52.

- Manfred Koschlig: A donum from Duttenhofer. In: Librarium , 3.1960, pp. 117–126, 7 illustrations.

- Manfred Koschlig: Arcadia is here too. News from Madame Duttenhofer's wonderful scissors. In: Librarium , 10.1967, pp. 124-147, 25 illustrations.

- Walther Küenzlen: Louise Duttenhofer. In: Walther Küenzlen: Waiblinger miniatures. Stuttgart 1988, pp. 86-90.

- Thomas Frank Lang: The artist with the sharp scissors. Christiane Luise Duttenhofer on her 225th birthday. In: Schlösser Baden-Württemberg , 2001, issue 2, pp. 10-13.

- Edith Neumann: Artists in Württemberg. On the history of the Württemberg Association of Women Painters and the Federation of Female Artists of Württemberg , Volume 1, Stuttgart 1999, pp. 30–33, 1 illustration.

- NN: From the Schillermuseum in Marbach [the works of Luise Duttenhofers are provided by Otto Tafel]. In: Schwäbischer Merkur No. 11 of January 9, 1912, pp. 5-6.

- Gustav Edmund Pazaurek: Black Art in Swabia. A silhouette study. In: Westermanns Monatshefte 105. 1908–1909, pp. 546–568, 50 illustrations. The pages of a revised special print are numbered consecutively from 1 to 24.

- Gustav Edmund Pazaurek: Louise Duttenhofer. A silhouette study with 14 illustrations in the calendar and 8 in the text. In: From Swabian plaice. Calendar for Swabian Literature and Art 1922 , calendar pages January to December, pp. 54–61, 25 illustrations Gustav Edmund Pazaurek: Louise Duttenhofer. A silhouette study . Heilbronn 1921 (PDF).

- Frank Raberg : Luise Duttenhofer 1776–1829. Born 230 years ago. In: Moments 2006, issue 2, page 21.

- Sebastian Rahtz: The Protestant Cemetery Catalog , Rome 2000 acdan.it (PDF; 2.7 MB).

- Ernst Schedler: Silhouettes by Luise Duttenhofer. In: Oberstenfeld - Gronau - Prevorst in history and stories , Volume 4, Horb am Neckar 2008, pp. 112-143, 53 illustrations.

- Hannelore Schlaffer : Luise Duttenhofer (1776–1829). Black and white clarity. In: Birgit Knorr; Rosemarie Wehling: Women in the German Southwest , Stuttgart 1993, pp. 123–127.

- Hannelore Schlaffer : Luise Duttenhofer (1776–1829). In: Elisabeth Noelle-Neumann (editor): Baden-Württemberg portraits. Female figures from five centuries , Stuttgart 2000, pp. 60–63.

- Gustav Schwab : [Necrology on Christiane Louise Duttenhofer]. In: Morgenblatt für educated stands No. 154 of June 29, 1829, pp. 613–615 (in Gothic script) books.google.com . Reprinted in Latin script: Koschlig 1953, pp. 14-19, and Koschlig 1968, pp. XXII-XXVII.

- Julia Sedda: Little tea hours, reading circles and flower arrangements, the everyday life of bourgeois women in the silhouettes around 1800 by Luise Duttenhofer. In: Schwarz auf Weiß 2006, issue 29, title page, pp. 1–4. Online version: scherenschnitt.org .

- Julia Sedda: Ancient Knowledge. The rediscovery of the line and the color black using the example of the silhouette by Luise Duttenhofer (1776–1829). In: Ulrich Johannes Schneider (editor): Cultures of Knowledge in the 18th Century , Berlin 2008, pp. 479–488.

- Julia Sedda: Reading Circles, Crafts and Flower Arranging. Everyday Items in the Silhouettes of Luise Duttenhofer (1776-1829). In: Maureen Daly Goggin (editor); Beth Fowkes Tobin (Editor): Women and Things, 1750-1950. Gendered Material Strategies , Farnham 2009. Pages 109–128.

- Julia Sedda: Reception of Antiquities and Christian Tradition. The silhouette work of Luise Duttenhofer , dissertation, Tübingen 2012.

- Julia Sedda: The cutter Luise Duttenhofer (1776-1829) , Stuttgart 2013.

- Arnold Wolff: Sulpiz Boisserée. The correspondence with Moller, Schinkel and Zwirner , Cologne 2008, pp. 529-530.

Illustrated books

- Otto Güntter (editor): From classical times. Paper cuts , Stuttgart 1937.

- Martin Knapp: German shadow and scissors pictures from three centuries , Dachau near Munich [1916], frontispiece, pp. 40–43, 11 illustrations.

- Manfred Koschlig (editor): The shadows of Luise Duttenhofer. A selection of 147 silhouettes , Marbach 1968, 140 plates, 149 illustrations.

- Gustav Edmund Pazaurek: The scissors artist Luise Duttenhofer (1776–1829) , Stuttgart 1924, 26 plates, 101 illustrations Gustav Edmund Pazaurek: The scissors artist Luise Duttenhofer (1776–1829) . Stuttgart 1924 (PDF).

- Hans Rühl; Gertrud Fiege: silhouette by Luise Duttenhofer. Facsimile printing of 147 plates from the collection in the Schiller National Museum / German Literature Archive in Marbach , Aarau 1978.

- Hannelore Schlaffer : The silhouette of Luise Duttenhofer . Frankfurt 1986.

Exhibitions

- 1812 Stuttgart - First art exhibition in Stuttgart in the Old Palace in May 1812.

- Heinrich Rapp: The first art exhibition in Stuttgart. In: Morgenblatt für educated stands , No. 127 of May 27, 1812, pp. 505–507, No. 135 of June 5, 1812, pp. 537–539, here: Page 537 Heinrich Rapp: The first art exhibition in Stuttgart (1812) (PDF).

- 1824 Stuttgart - Art exhibition in Stuttgart in September 1824.

- Ludwig Schorn: Art exhibition in Stuttgart, September 1824. In: Morgenblatt für educated estates, Kunstblatt No. 84 of October 18, 1824, pp. 333–336, No. 88 of November 1, 1824, pp. 349–351, here : Page 352 Ludwig Schorn: Art exhibition in Stuttgart , September 1824 .

- 1908 Stuttgart - Duttenhofer exhibition in the Landesgewerbemuseum

- HT: Stuttgart. In: The art. Monthly notebooks for free and applied arts , volume 17.1908, page 405.

- 1909 Düsseldorf - Silhouettes exhibition in the Kunstgewerbe-Museum

- G. Howe: Düsseldorf. In: Die Kunst, monthly for free and applied arts 19.1909, page 437.

- 1913 Breslau - Historical exhibition to celebrate the centenary of the wars of freedom

- Karl Masner , Erwin Hintze (editor): The historical exhibition for the centenary of the Wars of Freedom in Breslau 1913 , 2 volumes, Breslau 1916.

- 1914 Leipzig - International Exhibition for Book Trade and Graphics Leipzig 1914.

- Martin Knapp: psaligraphy, silhouettes, stencils, shadow play figures. In: Rudolf von Larisch (editor): Official catalog of the International Exhibition for Book Trade and Graphics Leipzig 1914 , Leipzig 1914, pages 195, 197.

- 1979–1980 Waiblingen, Heidelberg, Heidenheim - Luise Duttenhofer April 5, 1776 - May 16, 1829. An exhibition by the Schiller National Museum and the German Literature Archive in Marbach am Neckar on the 150th anniversary of death in Waiblingen (1979), Heidelberg (1980) and Heidenheim (1980).

- Gertrud Fiege: Die Scherenschneiderin Luise Duttenhofer , Marbach 1st edition 1979, 2nd edition 1990, 17 illustrations.

- 1993 Stuttgart - Swabian classicism between ideal and reality 1770–1830. Exhibition at the Staatsgalerie Stuttgart from May 15 to August 8, 1993.

- Gertrud Fiege: Luise Duttenhofer b. Hummel (1776-1829). In: Christian von Holst (editor): Swabian classicism between ideal and reality, essays , Stuttgart 1993, pp. 159–164, 6 illustrations.

- 1999 Gotha, Konstanz - Between ideal and reality. Artists of the Goethe era between 1750 and 1850. Exhibition in the Gotha Castle Museum from April 1 to July 18, 1999 and in the Rosgarten Museum in Konstanz from August 25 to October 24, 1999.

- Astrid Reuter: [Silhouettes and short biography of Luise Duttenhofer]. In: Bärbel Kovalevski (editor): Between ideal and reality. Artists of Goethe's time between 1750 and 1850 , Ostfildern-Ruit 1999, page 7, 107-108, 130, 144-145, 331.

Individual works

Alphabetically according to the title of the work and the year of publication.

- Cupid and Psyche.

- Gertrud Fiege: Antique black and white - Luise Duttenhofer's silhouettes for “Amor and Psyche”. In: Jochen Meyer (editor): Antiquity in sight: Strandgut from the German Literature Archive, Marbacher Magazin, Volume 107, Marbach 2004, pp. 80–83.

- Angelika Kauffmann in the studio, Dannecker in the studio, Matthisson in front of Schiller's bust, Uexküll in Eberhard Wächter's studio.

- Beate Frosch: Christiane Luise Duttenhofer. In: Christian von Holst (editor): Swabian classicism between ideal and reality. Catalog , Stuttgart 1993, pp. 286-288, 446.

- Ariadne on the panther.

- Gertrud Fiege; Mathias Michaelis: How Ariadne came across the panther. In: Black on white 2000, issue 15, pp. 15–16, 2005, issue 26, page 25, 3 illustrations.

- Book illustrations.

- Christian Gottlob Vischer: Lute tones. A collection of lyric poems [with 5 silhouettes by Luise Duttenhofer] , Frankfurt am Main 1821 Christian Gottlob Vischer: Lautentöne, Frankfurt am Main , 1821 (PDF).

- Manfred Koschlig (editor): Swabian customer. Ballads and romances by Schiller, Kerner, Uhland, Schwab and Mörike. With 7 paper cuts by Luise Duttenhofer , Marbach 1951, 7 illustrations.

- Charon (based on the poem by Goethe).

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Charon. Modern Greek. In: Ueber Kunst und Alterthum 4.1823, pp. 49-50.

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: To Charon, the modern Greek. In: Ueber Kunst und Alterthum 4.1823, pp. 165–167.

- Ludwig Schorn: Charon by Goethe. Invitation to sculptors and painters. In: Morgenblatt für educated estates , Art Gazette No. 6 of January 19, 1824, pp. 21-22.

- Ludwig Schorn: Charon. Modern Greek. In: Morgenblatt für educated estates, Art Journal No. 10 and 11 of February 6, 1826, pp. 37-44, Judgment on Luise Duttenhofer's silhouette: Page 41.

- Karl Leybold : [Lithograph of the award-winning Charon drawing]. In: Morgenblatt für educated Estates, Art Gazette No. 20 of March 9, 1826, supplement.

- Summary of the above sources on the competition for the visual representation of Goethe's Charon: Goethes Charon, sources for the visual competition (PDF).

- Faun with Cupid.

- Friedrich von Matthisson; Erichwege (editor): The family book of Friedrich von Matthissons , Volume 1: [Facsimile] , Göttingen [2007], No. 39 on page 47, Volume 2: Transcription and Commentary on the Facsimile , Göttingen 2007, pp. 64–65.

- Friedrich Rückert.

- Jürgen Erdmann (editor): 200 years of Friedrich Rückert 1788–1866, poet and scholar, catalog of the exhibition , Coburg 1988, pages 8, 43–44, 46, 1 illustration.

- Friedrich von Schiller

- Unterberger, Rose: Friedrich Schiller, Places and Portraits. A biographical picture book , Stuttgart 2008, page 154.

- The Scheffer siblings.

- Michael Davidis: The German Literature Archive Marbach receives a valuable work by the artist Luise Duttenhofer (1776–1829). In: Black on white 2006, issue 29, page 5.

- Goethe in Stuttgart 1797.

- Gertrud Fiege: "Goethe in Stuttgart 1797". From Luise Duttenhofer. In: Yearbook of the German Schiller Society 53.2009, pp. 11–18.

- Hope, Ascension, Our Father.

- Gertrud Fiege: "Hope" and "Ascension". Religious topics with Luise Duttenhofer (1776–1829). In: Schwarz auf Weiß, 2009, Heft 35, pp. 30–31.

- Ludwig Tieck

- Irene Ferchl: Nice books [50. Stuttgart Antiquarian Book Fair]. In: Stuttgarter Zeitung , January 25, 2011, page 24.

- Psyche paper cutouts

- Christiane Holm: Cupid and Psyche. The invention of a myth in art, science and everyday culture (1765–1840) , Munich 2006, pp. 214–217, 2 illustrations.

- Schiller's apotheosis.

- Gertrud Fiege: Luise Duttenhofer: Schiller's apotheosis. In: Schwarz auf weiß 2001, issue 17, pp. 22–23, 1 illustration.

- Sulpiz Boisserée, Mathilde Rapp

- Günther Bernhard Sellen: Sulpiz Boisserée ∞ Mathilde Rapp? To a fragmentary portrait of a married couple. In: Kölner Domblatt 48, 1983, cover picture, pp. 283–287, 4 illustrations.

- Albert Verbeek: Sulpiz Boisserée on the spiers of Cologne Cathedral. A satirical silhouette by Luise Duttenhofer. In: Kölner Domblatt 8/9, 1954, pp. 201–202, 1 illustration.

- Vases

- Christian Friedrich Duttenhofer: Ideas for vases , 6 booklets planned, at least 2 booklets published, Stuttgart 1810–1811. According to the KVK ( Karlsruhe Virtual Catalog ), the booklets are not available in any German library.

- NN: Announcement for art lovers [subscription offer for Duttenhofer 1810–1811]. In: Intelligence Journal of the Journal of Luxury and Fashions , No. 3 of May 1810, page XLVII.

- NN: [Advertisement of the second issue by Duttenhofer 1810–1811]. In: Intelligence sheet for the morning paper for educated classes , 1811, No. 13, page 49.

- various

- Ernst Biesalski : Paper cut and silhouette. Little history of silhouette art , Munich 1978, pp. 49–54.

- Hans Helmut Jansen; Rosemarie Jansen: artists of the paper cutting. In: Ruperto Carola 42.1967, pp. 53–64, especially pages 53, 55–56, 58–60, 4 illustrations.

- Sigrid Metken: Cut paper: a history of cutting out in Europe from 1500 to today , Munich 1978, pp. 135–136, 146–147, 8 illustrations.

- Susanne Schläpfer-Geiser; Sabina Nüssli: Paper cuts. Material, Techniques, History , Bern 1994, pp. 126–128.

- Herbert H. Wagner: The shadows of friendship. Silhouettes of artists and amateurs from Goethe's time. In: Art and Antiques 1977, No. 5, pp. 21–28, here: pp. 26–27.

- Water nymph and cupids.

- Christa Weber: Luise Duttenhofer. In: Schwarz auf Weiß 2002, issue 21, page 6.

Literary paper cutting

- Aloys Blumauer: Creed of one struggling for truth [1782]. In: Aloys Blumauer: all works , part 3, Königsberg 1827, pages 3–10 books.google.de .

- Matthias Claudius: The happy farmer. In: Matthias Claudius: Works in one volume , Munich [1976], pages 360–362 zeno.org .

- Johann Wolfgang von Goethe: Alexis and Dora. In: Friedrich Schiller (ed.): Muses-Almanach for the year 1797 , Tübingen 1797, page 1–17 Schiller Musenalmanach 1797 001.jpg .

- Christian Gottlob Vischer: Lute tones. A collection of lyric poems , Frankfurt am Main 1821 Vischer, Christian Gottlob, Lautentöne, Frankfurt am Main 1821 .

Sources and references

- Mathilde Boisserée (editor): Sulpiz Boisserée

- Volume 1: biography, letters, Stuttgart 1862. Reprint Göttingen 1970 books.google.de .

- The collection of letters is incomplete and the reproduction of the letters is incomplete. For further information see: Moisy 1956.

- Volume 2: Correspondence with Goethe, Stuttgart 1862. Reprint Göttingen 1970 with afterword and register of persons books.google.de .

- Michael Davidis: Between Classicism and Romanticism. The scissor cutter Luise Duttenhofer (1776–1829). In: Schwäbische Heimat 71 (2020), pp. 299–306 (not evaluated).

- Irene Ferchl: Stuttgart. Literary milestones in the Bücherstadt , Stuttgart 2000, pp. 62–64.

- Irene Ferchl: Reading wreaths and salons. Stuttgart's literary society in the 19th century , online texts from the Evangelical Academy Bad Boll, Bad Boll 2007, especially page 11 ev-akademie-boll.de (PDF; 210 kB).

- Adolf Haakh: Contributions from Württemberg to modern German art history , Stuttgart 1863, pp. 185–186, 189, 191, 290–291, 339 books.google.de .

- August von Hartmann; Gustav Schwab: Memories of Joh. Georg August v. Hartmann , Stuttgart 1849.

- Julius Hartmann (editor): Ludwig Uhland. Diary 1810–1820. From the poet's handwritten estate , Stuttgart 1898, see register, Duttenhofer.

- Julius Hartmann (editor): Uhlands Briefwechsel, Volume 2: 1816–1833 , Stuttgart 1912, Pages 5, 7, 55, 429 Internet Archive .

- Karl Klöpping: Historic cemeteries of old Stuttgart , Volume 1: Sankt Jakobus to Hoppenlau; a contribution to the history of the city with a guide to the graves of the Hoppenlaufriedhof , Stuttgart 1991.

- Friedrich von Matthisson: Friedrich v. Matthisson's literary estate , 4 volumes, Berlin 1832, here: Volume 2, page 153, 206 books.google.de , Volume 4, pp. 210-211 books.google.de .

- Karl Mayer: Ludwig Uhland, his friends and contemporaries, volume. 2 , Stuttgart 1867, pages 10, 30, 68, 96-97, 134, 196-197, 245 books.google.de .

- Konrad Menzel (editor): Wolfgang Menzel's memorials , Bielefeld 1877, pp. 210–211, 389, 537–538.

- Pierre Moisy: Les séjours en France de Sulpice Boisserée (1820-1825). Contribution à l'étude des relations intellectuelles franco-allemandes , Lyon 1956.

- Eduard Mörike: Works and Letters. [Historical-Critical Complete Edition] , 19 volumes, Stuttgart 1999-2008, Volume 10, Page 160, Volume 16, Page 147.

- Friedrich Noack: Duttenhofer. In: Schedarium of the artists in Rome , without place and year db.biblhertz.it .

- Bertold Pfeiffer: The Hoppenlau cemetery in Stuttgart , Stuttgart 1912.

- Marianne Pältz: Diaries. Sulpiz Boisserée, Register , Darmstadt 1995.

- Christian Ferdinand Spittler: Genealogical news from the Bilfinger family , Stuttgart 1802, page 21, 41.

- Hans-J. Weitz (editor): Sulpiz Boisserée. Diaries , 4 volumes, Darmstadt 1978–1985. Register see: Pältz 1995.

Web links

- Holdings on Luise Duttenhofer in the Marbach literature archive (manuscript collection)

- German paper cutting club

References and comments

- ↑ a b Fiege 1990 , pp. 13-14.

- ↑ Schwab 1829 , Fiege 1990 , pp. 15-21, Koschlig 1953 , pp. 26-30; Koschlig 1960 , pp. 121-124.

- ^ Deacon: second pastor.

- ↑ Johanna Christiane Duttenhofer born Hummel (1752-1814), Christian Duttenhofer's mother, was a sister of Luise's father.

- ↑ Today a district of Oberstenfeld

- ↑ See: 41 ° 54 '6.26 " N , 12 ° 29' 28.99" O .

- ↑ For Eberhard Wächter see: August Wintterlin: Wächter, Georg Friedrich Eberhard . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 40, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1896, pp. 431-434.

- ↑ a b Schwab 1829 , p. 614.

- ↑ Rahtz 2000 , p. 102, no. 74.

- ↑ Pazaurek 1924 .

- ↑ Fiege 1990 , pp. 8-9.

- ↑ Fiege 1990 , p. 18.

- ↑ Influence.

- ↑ Moisy 1956 , pp. 221, 227. We owe Sulpiz Boisserée some interesting details about Christian's personality, his professional qualifications and the relationship with his wife, see Moisy 1956 , pp. 200–201, 203–204, 206–208.

- ↑ Koschlig 1953 , p. 27. Further information, often only hinted at, can be found in Luise's other letters, see Koschlig 1953 , pp. 26–27, 29, Koschlig 1960 , pp. 121–124, Fiege 1990 , p. 17, 21st

- ↑ In the 1920s, Hartmann's daughter Emilie and her husband Georg Reinbeck moved into the " Hartmann-Reinbeckschen Haus " at Friedrichstrasse 14, where the social gatherings were now taking place.

- ↑ Today approximately opposite Leuschnerstrasse 9 ( 48 ° 46 ′ 41.52 ″ N , 9 ° 10 ′ 11.19 ″ E ).

- ↑ Menzel 1877 , p. 211.

- ↑ Today at the corner of Fritz-Elsas-Straße 49 / Leuschnerstraße ( 48 ° 46 ′ 38.68 ″ N , 9 ° 10 ′ 5.19 ″ E ). A memorial plaque for Johann Georg Hartmann refers to the house that was demolished in 1874.

- ↑ See: Hartmann 1849 , pp. 20-21, Koschlig 1953 , pp. 23-24, and Ferchl 2000 . For Johann Georg Hartmann see: Paul Gehring: Hartmann, Johann Georg. In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 7, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1966, ISBN 3-428-00188-5 , p. 733 f. ( Digitized version ).

- ↑ Mörike-Werke Volume 10, page 160, Volume 16, page 147.

- ↑ Fiege 1990 , p. 21. Thaddädl (von Thaddeus) was the name of a comical figure in the old Wiener Volksstück, a stupid, clever apprentice ( Koschlig 1960 , p. 121).

- ↑ Wedded helper: widow of the helper (= deacon) Georg Bernhard Hummel.

- ↑ See: 48 ° 46 ′ 50.88 ″ N , 9 ° 10 ′ 8.09 ″ E

- ↑ See Koschlig 1967 , p. 144. The two inventories of the graves of the Hoppenlau cemetery from 1912 (“according to official sources”) and 1991 (after autopsy ) do not mention Luise Duttenhofer ( Pfeiffer 1912 , p. 39, no. 39; Klöpping 1991 , p. 269, No. 485-486). The older list usually names all the inscriptions on a grave, but in this case it keeps silent about the mother's grave and Karl Friedrich von Duttenhofer in the case of the other. The newer directory gives only one representative name for each grave, usually that of the head of household, so that the search for clues remains in vain here as well.

- ↑ Koschlig 1968 , comments on Figures 115 and 126 on pages 161 and 165, respectively.

- ↑ 1960 or 1967 owned by Sigfrid Heesemann, Bonn, or his descendants. See also: Koschlig 1960 , Koschlig 1967 .

- ↑ Illustration: see here .

- ^ In the caption Friedrich Hölderlin is wrongly stated as a poet.

- ↑ Arthur Wyß: Pfnor, Johann Wilhelm Gottlieb . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 25, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1887, p. 693 f.

- ↑ Wintterlin: Müller, Johann Gotthard (von) . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 22, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1885, pp. 610-616.

- ↑ Fiege 2009 , p. 31.

- ↑ Pazaurek 1909, reprint , p. 24.

- ↑ Literature see here .

- ↑ Mirror: the inner recess of a plate , flag: the surrounding edge strip, throat: the arched connection between the mirror and the flag.

- ↑ Rapp 1812 , p. 537, Schorn 1824.1 , p. 351.

- ↑ Schorn 1826 , p. 41.

- ↑ Fiege 1990 , p. 24.

- ^ Mörike-Werke , Volume 10, page 160.

- ↑ Schwab 1829, page 614.

- ^ Pazaurek 1909 , Pazaurek 1922 , Pazaurek 1924 .

- ↑ Ferchl 2011 .

- ↑ Luise Duttenhofer exhibited one or more silhouettes. However, it is not mentioned in the two catalog volumes.

- ↑ For Karl Leybold see: August Wintterlin: Leybold, Karl Jakob Theodor . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 18, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1883, p. 516 f.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Duttenhofer, Luise |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Duttenhofer, Luise Christiane (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | German silhouette artist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 5, 1776 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Waiblingen |

| DATE OF DEATH | May 16, 1829 |

| Place of death | Stuttgart |