Nizarites

The Nizarites ( Arabic النزاريون, DMG an-Nizāriyyūn , Persian نزاریان Nezāriyān ) are an Ismaili - Shiite religious community with followers in almost all countries of the Islamic world , as well as in many countries in East Africa and Europe . It emerged at the end of the 11th century as a result of a split in the Ismaili Shia; the other large group of Ismailis are the Musta'lītes . Main settlement area of the nizari in the Middle Ages were Persia (Iran) and Syria , since the modern era there are India and Pakistan . After the Twelve Shia , the Nicarites form the world's second largest Shiite community with an estimated 15–20 million followers. A characteristic feature is the physical presence of an imam as the religious head in the succession of the prophet Mohammed . The current imam in the forty-ninth generation since 1958 is Karim Aga Khan IV.

designation

The usual self-designation of the Nizarites is "religion of truth [of God]" (dīn-e ḥaqq) . However, since every religious group claims knowledge of an all-embracing truth for itself, various other names were used for them in historiographical tradition. They themselves, as well as the Ismailis in general, alternatively called themselves "people of the inner / secret" (ahl-e bāṭin) , based on the strict secrecy of their teachings from outsiders that applies to them. The dogmas of their Shia are revealed by their Imam from the inner message of the Koran and passed on exclusively in secret, “inside” (bāṭin) , among their members who have sworn to absolute secrecy and loyalty to the Imam. In Muslim historiography, the term Batiniten ( Bāṭiniyya ) has been coined very often on them, to which they could not, however, register any exclusivity right. For a more precise definition, the term nizarites came up at the same time as their origin , with which they are identified as followers of the imam lineage descended from their nineteenth imam Nizar , to which they ultimately referred.

In Christian historiography of the Middle Ages, however, the Nizarites were only known as assassins , which, according to the prevailing doctrine since Silvestre de Sacy 1809, is a corruption of the Arabic word for "hashish smoker " (Ḥašīšiyya) . They have called their political opponents in Syria and Egypt so disrespectful since the publication of the “Amir'schen Guide” in the early 12th century, although in Arab society this swear word is generally used for social outsiders, criminals, the dangerous mob and also for the mentally insane has been used. Because that hashish consumption actually played any significant role among the Nizarites cannot be inferred from any of the contemporary evidence, neither from those left behind by them, nor from those of their enemies. Under this term, in any case, the Nizarites left a deep and lasting impression in the imagination of the Christian-European Occident and inspired it to form a legend that is still popular today, which is inspired by the extravagant and mysterious appearance of the "sectarians" and the assassinations they practice for which they were feared by Christians and Muslims alike. In several European languages, the terms for assassin / murderer, murder and murder have been derived from this external name.

As the numerically largest splinter group of Ismaili Shi'aism today, the Nizarites are more recently again summarized under the synonym Ismailiten (Ismāʿīliyya) , which has been recorded in their official name "Shia Imami Ismailis" (allegiance of the Ismaili Imams) since the late 19th century , but with the Tayyibites in Yemen and India (the Bohras ) and the Mu'minites in Syria there are still further, albeit numerically significantly smaller, Ismaili groups who do not profess to be a follower of the Imam of the Nicarites.

Beliefs

The religious dogma of the Nizarites is based on that of the Ismailis and does not differ essentially from that of other Shiite or Sunni groups. The bottom line of the Shiite doctrine includes a promise of salvation, the break of the individual believer Doomsday is cashed, but its fulfillment is dependent in the confession of the faithful as the rightful Imam. Because only to the rightful representative ( ḫalīfa ) of Muhammad as the spiritual director (imām) of the religious community the secret (bāṭin) message of the Koran is revealed, which is hidden in its external (ẓāhir) wording. The Imam passes these messages on to his adepts in secret meetings, who in turn entrust propagandists, so-called “callers” ( duʿāt ; singular dāʿī ), with spreading them to the faithful. The secret messages of the Koran may only be revealed to the members of the Shia, in so-called "Meetings of Wisdom", which are held on Thursdays in contrast to the Sunnis , Jews and Christians . Outsiders are not allowed to take part in such meetings unless they have been familiarized with the doctrine by a Da'i and, as converts, have made a creed on it , which is combined with a pledge of absolute secrecy and loyalty to the Imam. The callers are also responsible for the Ismaili-Nicaritic mission, the “call” ( daʿwa ) , for the recruitment of new believers.

Nizarites recognize other Shiite groups as well as Sunnis as Muslims (muslimūn) , but only consider themselves to be actual believers (muʾminūn) , which in turn is based on reciprocity. In the heads (imams, caliphs) of the other denominations, they recognize usurpers, whose followers consequently have no access to the true message of the Koran and therefore live in unbelief.

The prerequisite for the legality of an imam is for the Nizarites, as for all other Shiites, whose dynastic inheritance from the Prophet Mohammed via his daughter Fatima from her marriage to the fourth and last of the rightly guided caliphs Ali , who was murdered in 661. The caliphate subsequently established by the Umayyads , however, was rejected by them, as well as by all other Shiites. Accordingly, the Imam lineage begins with Ali among the Ismailis / Nizarites.

history

Prehistory - the Ismailis

The Ismaili Shia emerged in the 8th century after the splitting of the great Imamite Shia following the death of Imam Jafar as-Sadiq (d. 765). Its followers split up among the descendants of his two sons. Because the first-born son and designated successor Ismail (d. 760) had died before the father, the majority of the Shia recognized an error in this designation (naṣṣ) by the actually infallible Imam and after his death therefore sought out his second-born son Musa ( gest. 799) grouped. This following later became known as the Zwölfer-Schia . A smaller group had regarded the designation of Ismail, regardless of his premature death, as an irrefutable dogma of their Imam and now transferred this to a son of Ismail in the sense of inheritance. These followers of Ismail only recognized the lineage of Imam descending from him as legitimate.

When the Ismailis came into being , they initially included rural southern Iraq , but through intensive missionary work they were able to expand their range throughout the Islamic world within a century and increase their number of followers considerably. New followers could be won in the Arabian Peninsula, Persia, Syria and Palestine. At the end of the 9th century, the first Muslim communities in Berber Algeria and India finally acknowledged their Shia. In 910, the Ismailis conquered the emirate of the Aghlabids in what is now Tunisia and proclaimed their eleventh Imam Abdallah al-Mahdi (874-934) as the “Deputy” ( ḫalīfa ) of the Prophet. The Ismaili caliphate established in this way should remain the only one in the history of Islam that emerged from Shi'aism. From then on it stood in rivalry with the Sunni Caliphate of the Abbasids of Baghdad and worked towards overcoming it. In reminiscence of the ancestral mother of the Ismaili Imams, Fatima , the new Caliph dynasty was called the Fatimids . In 969 the Ismailis / Fatimids conquered Egypt and moved their rulers' seat to the newly founded Cairo . Here the office of the chief missionary, the “caller of the callers” (dāʿī d-duʿāt) , was established, who was subordinate to the Imam and who was responsible for spreading his messages among the faithful and for organizing the Ismaili mission.

Until the end of the 11th century, the Fatimid caliphs, who were also the imams of the Ismailis, were able to continue an uninterrupted lineage in Cairo and also establish one of the most powerful empires in the Islamic world. The scope of the Ismaili mission was not limited to their realm. There were also large communities in Syria and Persia, which, however, have come under political pressure since the arrival of the Turkic Seljuks in the early 11th century, as the Seljuks embraced Sunni Islam and thus the Caliph of Baghdad.

The Ismaili Schism

The death of the eighteenth imam caliph al-Mustansir in 1094 ushered in the historical turning point that led to the division of the Ismailites and thus the establishment of the Nizarites. The incumbent vizier al-Afdal Shahanshah , who was of Armenian descent and who, like his father, already carried out the actual business of government in Cairo, bore a major responsibility . And like his father, al-Afdal had usurped the office of “supreme caller” and thus acquired control of the Ismaili mission without any sense of the religious sentiments of the Shia as a military, or any interest in the subtleties of them To have had secret doctrine. Al-Afdal's priorities were centered on increasing personal power, and the death of the Imam-Caliph had given him new opportunities to expand it. In a coup d'état, he immediately proclaimed one of the deceased's youngest sons, al-Mustali , who was only around twenty , as the new caliph and extorted recognition of this act from the older brothers present under threat of death. To this end, he had immediately married one of his sisters to the new Imam-Caliph, who was no longer to remain as a puppet of the vizier for the rest of his life.

Only the first-born son, Nizar , who is over forty years old , did not recognize this change of power and claimed the successor to his father for himself, as he had given him the appropriate designation years earlier. The designation (naṣṣ) has the legally binding role of a will in Shiite Islam. As an expression of the Imam's will, it had the character of a religious dogma, which the believers were obliged to observe. For this reason, the Ismailis once followed the Imam line of Ismail, who was designated by his father to succeed him in the Imamate. And Prince Nizar now also claimed such a designation for himself. He holed up in Alexandria and proclaimed himself the rightful Imam-Caliph there. But already in the following year he had to submit to the vizier, militarily defeated. He was first taken to a dungeon in Cairo, where he was secretly killed. However, the quick clarification of the struggle for the succession to the throne in Cairo did not prevent the split between the Ismailis. The fault line of this split ran almost exactly along the immediate domain of the imam caliphs, i.e. the Fatimid empire of Egypt and Syria, and the settlement areas of their Shia beyond them, i.e. above all in Persia. While the Shia within the Fatimid Empire willingly or at least tacitly recognized the succession enforced by the vizier and can therefore now be described as Mustali Ismailis , the Shia in Persia and parts of Syria have committed themselves to Nizar.

The family of the 18th Imam:

|

Caliph al-Mustansir 18th Imam 1036-1094 |

Badr al-Jamali vizier 1074-1094 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Nizar 19th Imam 1094-1095 |

Caliph al-Mustali 1094-1101 |

? |

al-Afdal Shahanshah vizier 1094–1121 (X) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Caliph al-Amir 1101-1130 (X) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Nizarites | Tayyibites | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mu'minites | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In Persia, the Ismailitenschia under the leadership of the charismatic Da'i Hassan ibn as-Sabbah , or in Persian Hassan-i Sabbah (Hassan, descendant of the Sabbah), had experienced an urgent expansion, despite the constant threat from the Seljuks . This was thanks to a purposeful strategy and decisive action against their enemies imposed by Hassan. Through infiltration and occupation, the Ismailis took possession of several hilltop castles in the inaccessible mountainous region of the Elbe near the south coast of the Caspian Sea and fortified them strongly. The Ismailis managed to create a safe refuge for themselves in the mountain valleys they controlled and were difficult to access. In 1090 the Alamut castle ( Olah amūt , eagle's nest ) in the Dailam region was taken, which Hassan made his main residence and which he never left. In the following years, more castles were won across Persia, including some in the immediate vicinity of Isfahan , the capital of the Seljuks. At the end of the 11th century, Hassan, as Gran-Da'i, was the undisputed leading authority of the Persian Ismailis. The Shia there followed his command unconditionally and he himself only recognized the True Imam.

But when in 1094, after the death of the eighteenth imam, his eldest son Nizar was not raised as the new head of the Shia, Hassan recognized this as an attack on their religious convictions, whereby personal interests may also have been at play. Hassan once deepened his faith in Cairo and came into contact with the highest religious masterminds of his Shia. At that time, however, the vizier Badr al-Jamali , who was an Armenian military slave by origin, had also occupied the religious office of "supreme caller" in order to increase his power. Apparently Hassan took public offense at this and also campaigned for the successor to Prince Nizar as the future Imam-Caliph, incurring the disfavour of the vizier, who therefore banned him from Cairo and Egypt after two years. When the son of the old vizier had chosen a puppet for the imamate, Hassan and his loyal Persian followers declared themselves followers of Nizar and recognized him as the rightful nineteenth imam. Although Hassan had not had a personal encounter with the eighteenth Imam al-Mustansir during his time in Cairo, he was nonetheless convinced of the existence of his designation for his eldest son, which, according to their Shia, had to be followed. This is how the Shia of the Nizarites came into being, who regarded themselves as true followers of the Ismaili Shia, while they recognized the imam caliphs who followed in Cairo as usurpers. The entire Isamili-Shia of Persia, as well as a large part of those of Syria, followed Hassan's view and recognized Nizar as a legitimate imam.

Reaction - Amir's guidance

There is no timely evidence of the split between the Ismailis and the views of the people involved. Only after the vizier al-Afdal, who was responsible for the split, was murdered in Cairo in 1121, did the Mustali Ismailis react. The murder was officially blamed on the "Batinites" / Nizarites, but it was probably commissioned by the caliph al-Amir , who had been in office since 1101 and who was also the twentieth Imam of the Mustalia.

Al-Amir immediately used the circumstances politically to carry out a propagandistic blow against the Nizarites, who from his point of view were renegade. In December 1122 he set up a council of the religious authorities of his Shia in Cairo, in which the question of the legality of his imamate should be discussed. The central point of discussion was the content of the designation of the eighteenth imam al-Mustansir. Al-Amir called in several witnesses to confirm that his grandfather had designated his father to succeed the Imamate. A woman, a full sister of Nizar, was interviewed as the key informant, who confirmed that her father, lying on his deathbed, had changed his designation in favor of the youngest son al-Mustali, making his imamate and ultimately that of al-Amir the legal one . But those who followed the Imamate of Nazir had fallen away from the right faith. Al-Amir has sent this knowledge in several letters to his followers in Syria and also to Hassan-i Sabbah in Alamut, with the request that they explain themselves. This letter, "the Amir'sche guidance" (al-Hidāya al-Āmiriyya) , is still carefully kept in copies by the Indian Nizarites. There is no record of a reply by the Gran-Da'i to the expertise of the counter-imam from Cairo, which he hated. His followers did not provide an answer until years after his death in 1124.

It is worth mentioning in this context the choice of words that al-Amir chose in his Hidāya towards the Nizari Ismailis. In one of the letters addressed to his followers in Syria, he had denigrated them as "hashish smokers " (ḥašīšiyya) and thus left the oldest known testimony of this term in relation to the Nizarites. Obviously, this designation was able to establish itself firmly in Syria by the end of the 12th century, which is why the Nizarites there were also known by this name among the Christians of the Crusader states neighboring them ( Benjamin of Tudela , Wilhelm of Tire ). On October 7, 1130, the Nizarites / assassins responded to the questioning of their Shia when several of their Syrian victims, who were willing to make sacrifices, entered Cairo and pulled al-Amir from his horse and stabbed him to death.

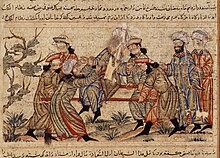

Political murder

A method introduced by Hassan-i Sabbah in the fight against the enemies of his Shia was that of political murder, which became a characteristic of the medieval Nizarites. Militarily far outnumbered their mortal enemies, the Sunni Seljuks, the Persian Ismailis shifted their struggle to targeted attacks against the leaders of the Turkish conquerors. The first spectacular assassination attempt was carried out in 1092, before the Ismaili schism broke out. The almighty Seljuk vizier Nizam al-Mulk was stabbed to death with a dagger by a supplicant who had approached him during Ramadan while breaking the fast and in the presence of his bodyguard, whereupon he bled to death. The perpetrator was described as a "Dailamite boy, one of the Batinites", a native of the Dailam region, the area around Alamut, which was firmly in the hands of the Ismailis. The assassination of the vizier is considered to be a decisive turning point in the history of the Seljuks, whose empire then fell apart in the succession battles of competing pretenders, from which the Nizarites could take advantage and expand their power in Persia considerably.

The perpetrators were not suicide bombers, as is still often postulated today, but the probability that they were killed in the act of commissioning themselves was much higher than that they will survive it. The murderer of Nizam al-Mulk had already intended to flee, but stumbled over a rope of tent and was caught up with and killed by the vizier's bodyguard. The perpetrators sent out to attack were therefore referred to by the Nizarites as " willing to sacrifice" ( fidāʾīyān ) . Because associated with an attack was always the spread of psychological terror among the Nizarites, as the acts were often carried out during the day or in the presence of uninvolved witnesses, even supporters of the victim. This was intended to make their enemies understand that they should never underestimate the absolute determination of a Fida'i, that they could not feel safe at any time of the day, no matter how many bodyguards they were surrounded by. Preparing an attack was often a time-consuming process. Usually, the immediate vicinity of the target had to be infiltrated and often the target's personal trust had to be won. A dagger was always used to carry out the deed and the stab wounds had to be placed on the victim in such a way that the victim would definitely bleed to death. In fact, only a few cases have survived in which the victim was able to survive through rapid medical treatment. The assassins themselves were usually killed immediately after the crime by the bodyguards of their victims, or lynched by the angry crowd. The successful escape of a Fida'i is only recorded in rare cases.

The Nizarites' preferred targets were political, military and religious leaders of both Sunni Islam and the Mustalite usurpers in Cairo. Especially in the 12th century, hardly a year has passed without at least one murder recorded. Lists were later found in the archives of the Nizarites in which they recorded the attacks they had successfully carried out, with the names of the victims and the perpetrators. The largest group of victims was made up of Qadis and Muftis , because this group of people, as local representatives of the Sunni judiciary, was entrusted with the persecution of deviants and sectarians, among whom the Nizarites fell from the point of view of Sunni Islam. But the highest worldly and spiritual personalities were also attacked. The most prominent victims include the Sunni caliphs al-Mustarschid (X 1135) and ar-Raschid (X 1136), the Seljuq vizier Fachr al-Mulk (X 1111) and the Sultan Dawud (X 1143). As early as 1130 the ruling counter-caliph of the Mustali Ismailis al-Amir in Cairo was killed, which ushered in the fall of the Fatimid caliphate. Several assassination attempts were also made on the Sunni Sultan Saladin ( Salah ad-Din Yusuf) , but all of them failed. In 1152 the first non-Muslim, Count Raimund II of Tripoli, was murdered, later followed by Margrave Conrad of Montferrat (X 1192) and Raimund of Antioch (X 1214). Overall, however, attacks on Christians have remained the exception.

After all, the Nizarites were so notorious for their murderous practices that almost every act could be attributed to them, or underlined. In fact, they often publicly celebrated the killings of opponents, even if they had not carried out the act themselves. For example in 1121 the killing of the Fatimid vizier al-Afdal, who caused the Ismaili split.

The resurrection

The founding of the Schia Nizars was accompanied by a not insignificant problem for the Gran-Da'i Hassan-i Sabbah. With the death of the nineteenth imam in the dungeon in Cairo, the new Shia had lost its religious leader without a successor being available. The physical presence of an imam was a central component of the Ismaili belief system, without which they had no access to the inner message of the Koran and without which the existence of their Shia could be called into question by their opponents in Cairo, which actually happened in 1122.

For Hassan-i Sabbah there was a need for clarification on the question of the Imamate. He made use of the concept of secular remoteness / secrecy ( ġaiba ), which has already been tried and tested several times in Shiite Islam . Among the Twelve Shiites, the imam had been raptured into secrecy since the 9th century, where he resides to this day, and the Ismailis had also kept their imams in secret for a time to protect them from the persecution of the Abbasids . Hassan-i Sabbah has now followed the same strategy by proclaiming the rapture of their Imam to the Shia, combined with the promise that the end times will begin on his return.

| time | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1090-1124 | Hassan-i Sabbah | Gran-Da'i |

| 1124-1138 | Kiya Buzurg-Umid | Gran-Da'i |

| 1138-1162 | Muhammad ibn Buzurg-Umid | Gran-Da'i |

| 1162-1166 | Hassan II. Ala Dhikrihi s-Salam | 23. Imam |

| 1166-1210 | Only ad-Din Muhammad II. | 24. Imam |

| 1210-1221 | Jalal ad-Din Hassan III. | 25. Imam |

| 1221-1255 | Ala ad-Din Muhammad III. | 26. Imam |

| 1255-1256 | Rukn ad-Din Khurschah | 27. Imam |

From their foundation, the Nizarites were led outward by the Gran-Da'i, who resided on Alamut. After the death of the founder Hassan-i Sabbah in 1124, he was followed by his old companion Kiya Buzurg-Umid (d. 1138), who in turn was inherited by his son Muhammad (d. 1162). Under the leadership of these three "grand masters", a real Nizarite state has emerged in Northern Persia, which was able to assert itself against the Seljuk great power and from which the Shia was able to assert its influence from Syria to India. They were despised by their enemies as well as feared.

In spite of all this, up to the middle of the 12th century there was increasing unrest among the Shia, which was sparked by the absence of their imam. With the claim made from the beginning to continue true Ismailishness, the physical presence of the Imam was indispensable and not compatible with an absence. The dissatisfied began to rally around the son of the third master, Hassan II , who attracted attention for his special erudition and above all for his undisguised disregard for the laws of Islam, compliance with which his father was still rigorously persecuted. Young Hassan's followers increasingly began to recognize him as their imam. During the old master's lifetime, this opinion was strictly suppressed and Hassan himself did not dare to comment on it. But as soon as his father died in 1162, he dropped his mask. On August 8, 1164, in a solemn act in Alamut, he read a letter from the supposedly hidden imam, in which he, as his authorized representative (caliph), announced the dawn of the end times or "the resurrection" (al-qiyāmāh) of the imam. He had delivered this speech to his followers from a pulpit facing Mecca , so that the crowd had to turn their backs on the holy city of Islam as he preached. With the dawn of the end times, the repeal of Islamic law ( šarīʿa ) , the end of all fasting rules, the duty of pilgrimage, like the end of the prohibition on drinking wine and the daily duty of fivefold prayer came along. In the religion of Islam, the resurrection / end times is associated with the revelation of the divine message for all believers, which otherwise can only be inferred to the Imam from the internal sense of the external wording of the Koran. With this revelation goes hand in hand with the fall of all temporary sheaths of faith, the words of the Koran and the commandments of the Sharia, whereby the worship of Allah by the believer finds its way back to its paradisiacal form , just as the first man Adam once prayed to him directly.

The resurrection was proclaimed in all Nizarite congregations and was accepted as a generally applicable dogma, even if it came to controversial arguments in the period that followed. From the standpoint of Sunni orthodoxy, the Nizarites have thus left the community of believers, have become apostates of true Islam and heretics ( malāḥida ) , which every Muslim is commanded to destroy. The judgment of the Sunni historiography of the Middle Ages (see Juwaini ) was clear.

Hassan II himself has not yet made any claim to the imamate; until his murder in 1166 he only saw himself as his representative. But immediately after his death, his followers recognized him as the actual resurrected Imam by negating his public affiliation with the third Gran-Da'i and instead placing him in a lineage to the nineteenth Imam Nizar. Sunni historiography recognized this as a fiction, while the revived imamate has not been questioned by the Nizarites since.

The Shia in Syria

At the beginning of the split between the Ismailis in 1094, the centers of power and main settlement areas of the two groups formed were spatially separated by a large geographical distance, the Mustali Ismailis in Egypt and the Nizari Ismailis in Persia. Only in Syria did they come into direct contact with one another, since the Ismailite community there has divided into both currents. The greater part known themselves as Mustalites, but the Nizarites made up a significant minority from then on. The situation in Syria changed significantly with the arrival of the Christians of the First Crusade , which was proclaimed in distant Clermont in 1095 , when the Christians drove a geopolitical wedge between Syria and Egypt by establishing their Kingdom of Jerusalem and other states.

The Nizarites became active in Syria very early on and, through their missionary work, were able to quickly increase the number of their followers. Her relationship with the Seljuq emir of Aleppo Radwan played a decisive role in this . Although he was outwardly Sunni, to the annoyance of his subjects, he tolerated “Batinites” in his closest environment. The first Da'is of the Syrian Nizarites, the “wise Batatinite astrologer” and the “Persian goldsmith”, belonged to his entourage, who were allowed to open a mission house (dār ad-daʿwa) in Aleppo with his permission . In 1103 they carried out their first assassination attempt. The victim was Radwan's former mentor, whom they probably liquidated on his behalf. In 1113 they murdered Maudud for the emir whose rival for rule in Syria was just leaving the great mosque in Damascus after a prayer. The following year, a large-scale attempt to nizari failed bloodily, the castle Shaizar to conquer. Continued attacks have raised general sentiment against the community and when Radwan died in 1113, she lost her protective hand. His son ordered the persecution of the Nizarites, who were killed by the thousands in pogrom-like unrest and the survivors were driven from the cities. In the Atabeg of Damascus they now hoped to find a new protector, from whom they received the border fortress Banyas in 1126 . But after the Atabeg died in 1129, a pogrom against the Nizarites also broke out in Damascus after a political upheaval. In retaliation for this, they handed over banyas to the Christians of the Kingdom of Jerusalem and in 1131 murdered the Atabeg responsible for the persecution.

In order to save the cause of their Shia in Syria, the Nizarites here in the following years resorted to the strategy already tried and tested by their Persian comrades by creating a safe and easily defended refuge by occupying fortified positions in a mountainous region should. Around 1133 the Nizarites bought the castle of Qadmus . Starting from her, they established their own rulership territory in the following years, which they extended over the ridges and valleys of the Jebel Ansariye . By murdering their old owner in 1141 they finally took possession of the strong fortress Masyaf , which was to remain the new headquarters of the Da'is until it was conquered by the Mamluks in 1270. The territory of the Syrian Nizarites bordered directly on the territories of the Christians of the Principality of Antioch and the County of Tripoli , with whom, apart from the murder of the Count of Tripoli in 1152, good relations were maintained.

In 1162, Raschid al-Din Sinan, a personality with no less determination, took over the leadership of the Syrian Nizarites, as once demonstrated by the founding father Hassan-i Sabbah. Sinan was of Persian descent and, like every Da'i in the Syrian community, he was appointed to his post by the Gran Da'i of Alamut. He was a devoted follower of Hassan II and brought the message of the resurrection to the Syrian Shia. Sinan was the "old man from the mountains" of the Christians ( Wilhelm of Tire ), although this term was later also applied to other leaders and imams of the Shia. The confrontation of the Nizarites with Sultan Saladin ( Salah ad-Din Yusuf) , who ended the Shiite caliphate in Egypt in 1171 and established his power in Syria, is particularly connected with him . The Sunni had no intention of tolerating the heretics of Masyaf in his domain. In order to avoid the military threat, Sinan ordered at least two assassinations on Saladin, none of which could be carried out. But in the end Sinan was able to negotiate a peace with Saladin in 1176, which guaranteed the continued existence of the state of Masyaf. The Sultan gave the fight against Christians a higher priority.

Despite the peace with Saladin, the Syrian Nizarites experienced a continuous loss of importance afterwards. The main reason for this was the power of the Sunni Ayyubid Empire of Egypt and Syria, which militarily and ideologically prevented further expansion of the Ismaili heresy. The "assassins" have also increasingly lost their horror towards the Christians, which was probably also due to the fact that they began to profitably sell their talents for murder to third parties. Already the murder of Margrave Konrad von Montferrat in 1193 was probably motivated with the intention of winning money, apart from the later emerging legends about an alleged personal insult to Sinan. In any case, contemporaries on both sides of the faith have speculated a lot about the real perpetrators of the attack. Both Saladin and Richard the Lionheart were suspected. Politically or ideologically motivated attacks were carried out much less frequently in the 13th century and finally went completely out of use in the middle of this century. Sinan died in the same year as the margrave fell victim to the daggers. The relationship between the assassins and the Christians then turned positive again. Contacts with them were maintained until the fall of Masyaf in 1270, such as their diplomatic exchange with the cruising rulers Emperor Friedrich II. And King Ludwig IX. testifies to France . In the 13th century they were even subject to tribute to the Christian knightly order of the Templars and Hospitallers for a longer period of time. A change in this relationship could not be achieved for them, since if a grandmaster had been murdered, the order would have immediately elected a new one to his post. At least that is what a delegation of assassins complained to the King of France (see Joinville ). The Da'i Nadschm ad-Din Ismail had assured King Manfred of Sicily in a letter dated late 1265 of his support in the fight against Charles of Anjou and the Pope.

The Syrian principality of the Nizarites was destroyed in 1273 by the Sunni ruler Baibars I , on whom a failed assassination attempt had been carried out two years earlier. At first, Baibars had made the leaders of the Syrian assassins his vassals. The attacks on Philip of Montfort and Prince Edward of England ordered by them in 1270 and 1272 had already been carried out at his behest. But after the Da'i had proven to be unreliable, Baibars went over to take over the state of Masyaf directly. He had already conquered Masyaf in March 1270 and the last Syrian Assassin castle al-Kahf, about twenty kilometers west of Masyaf, finally capitulated to him on July 10, 1273. The last Da'i was settled with a fiefdom in Egypt.

After the 13th century, the Nizari-Shia in Syria, which increasingly shrank to ever smaller communities, split off from the Nizarites as Mu'minites when the twenty-eighth imam died in 1310 and continued its own line of imams. After this became extinct in the 18th century, most of them rejoined the Shia of the imam lineage that still exists today. But a few mu'minite communities still exist in Syria without an imam and live in the villages around Masyaf.

The end of Alamut

By the end of the 12th century the power of the Seljuks in Persia was broken, but they were inherited by the Choresmi , who, as Sunnis, also represented a serious threat to the Nizarites. However, the cohesion of their community was also threatened by internal threats after controversial disputes over the interpretation of the doctrine of the resurrection had sparked. Hassan's II. Son and successor Nur ad-Din Muhammad II continued it unconditionally, but after his death in 1210 the new Imam Jalal ad-Din Hassan III. a U-turn was proclaimed, the Sharia and all religious commandments of Islam put into effect again. The extent to which this turning away from the teachings of his forefathers was influenced by external political pressure can no longer be determined today, but these measures actually took the wind out of the sails of the threat posed by the choristers. Because Hassan III. had committed himself to orthodox Sunniism, for which he was solemnly accepted into the community of believers by the Abbasid caliph of Baghdad as a “new Muslim”. His Schia was devoted to him, but followed silently. In order to publicly demonstrate his new orthodoxy, Hassan III. to take stock of his library located on Alamut and to sort out all books classified as heretical that were publicly burned in the presence of emissaries of the caliph. In the time of Hassan III. Further changes have taken place on the political map of Persia. The Khorezmian Empire was defeated by the newly emerging power of the Mongols of Genghis Khan and collapsed. The first Muslim ruler to go to an audience with the conqueror was the Imam of the Nizarites.

1221 is Hassan III. died, rumor has it that he was being tutored, and his son's guardians immediately denied his Sunni confession and professed the doctrines of the resurrection without any noteworthy resistance in the Shia. The disturbing contradiction that the intervening return to the Sunnah and Sharia has evoked among believers has been satisfactorily resolved with a theological theory handed down in the writings of the famous Persian polymath Nasir ad-Din Muhammad at-Tusi (1201–1274) is. Accordingly, the lawless paradisiacal original state of faith that occurs with the resurrection (qiyāmāh) is subject to the phases of "veiling" (satr) and "revelation" (kašf) . While this state manifests itself in the abolition of all religious commandments in the times of revelation, for reasons of caution ( taqīya ) it retreats into the inner sense (bāṭin) of the Koran during times of veiling , where it reveals itself only to the Imam. During this time the believer is again subject to the observance of the external (ẓāhir) physical act of religion, such as observance of Sharia law, observance of fasting and prayer, and pilgrimage. To what extent Tusi, who lived on Alamut for several decades and converted to Ismailism there, was involved in the formulation of this theory cannot be determined. But his surviving writings have given posterity the most comprehensive insight into the theology of the Nizarites of the Middle Ages.

Because the Mongols dedicated themselves to the conquest of China in the following years , the Islamic world of the Near East experienced a moment of sigh of relief. Occasional marching Mongolian generals operated mainly in the Caucasus region and Azerbaijan, but did not venture far into the Persian mountain regions. Under these circumstances, the state of Alamut under its supposedly crazy Imam Ala ad-Din Muhammad III. can still maintain a period of peace and independence. He has always avoided a request addressed to him for personal submission ( kowtowing ) to the Great Khan. This was the doom of the Nizarite state when in 1256 the Mongol Khan Hülegü crossed the Oxus to Persia with a huge invading army . His first destination was Alamut. Muhammad III was already there last year. were murdered and his son Khurschah had also resisted repeated requests for submission. When the Mongol army marched in front of Alamut, it was too late for that. Recognizing his hopeless inferiority, Churschah has surrendered after all and, on the instructions of Hülegü, asked his followers to give up Alamut. The “eagle's nest”, which had withstood every attacker for almost one hundred and eighty years, fell into the hands of the Mongols without a fight after just one day of siege. Hülegü had the castle razed so that it would never again become a place of resistance. The Nizarite state in Persia ceased to exist. Imam Churschah was executed a year later on the orders of the Great Khan with several of his relatives.

The Persian chronicler and court official Ata al-Mulk Dschuwaini (1226–1283) also belonged to the Mongol army . He was a Sunni out of deep conviction and for whom, from his point of view, heretical Ismailis from Alamut only knew contempt. The last chapters of his work, "The History of the World Conqueror" ( Ta'rīch-i Jahānguschāy ), were devoted to their downfall . After the capture of Alamut, Juwaini had the opportunity to search through the Imam's library, whose heretical works were then to be destroyed in a car dairy like almost forty-five before . For his description of the heretical practices of the Nizarites and their history, however, he drew extensive information from their written records. In places he has quoted entire passages from the autobiography of Hassan-i Sabbah and the theological works of the Shia, of course only to reveal their supposed heresy. So it is ironic of history that the most extensive accounts of the history of the Shiite Nizarites of Alamut have been handed down to posterity through the pen of a Sunni, of all things. Other Persian historians such as Raschīd ad-Dīn (1247-1318) have also been able to look into the written legacy of the Nizarites and quote from them.

The long time of caution

Contrary to the news announced by Juwaini of the complete extermination of the heretical community in Persia, the Ismaili-Nicarite Shia was able to continue to exist there. Due to the loss of their castles, the last Gerdkuh near Damghan fell in 1270, they lost their organizational structure and political independence. The community has withdrawn to the villages and towns of northern Persia and Azerbaijan, which were far removed from the centers of power of the now ruling Mongolian Ilkhan . Following the command of caution ( taqīya ) , their followers have publicly denied their faith, or disguised themselves as Sufis or Twelve Shiites, especially in situations of threat . The line of imams was also able to continue, although it has now largely withdrawn from the public eye. The caution they also show, however, is not to be equated with concealment (ġaiba) ; the imams were still physically present for their followers and could be visited by them. The Ismaili mission (daʿwa) also continued steadily.

After the end of the Crusades at the end of the 13th century, the Nizarites / Assassins only got out of the historiographical field of view among Christians in Europe and therefore found their way into popular literature in the western world. Shortly before the turn of the century, the Venetian world traveler Marco Polo crossed the area around Alamut on his way back from China and there he learned the most adventurous stories of the invisible, inaccessible and insane "old man from the mountains" Aloadin and his blindly devoted disciples who were told by beautiful virgins in seduced in a garden of paradise and made docile with drugs, only to be sent out to commit suicidal attacks. Based on these and other reports embellished with a lot of imagination, a "black legend" has established itself in Europe in the coming centuries around the assassins, in which they entered into it as ruthless religious fanatics and docile disciples of their masters, who relied on him as proof of their absolute loyalty Instruction even fell from the walls of their castles. In the recent past they have been increasingly cited as prototypes of Islamist terror .

In Marco Polo's time, the “old man from the mountains” actually lived in relatively modest circumstances in Tabriz, Azerbaijan . After the death of the 28th Imam Shams ad-Din Muhammad (d. 1310), the Shia of the Nizarites experienced a similar schism as it happened more than two hundred years ago when it was founded. The Shia split between two pretenders and henceforth formed the lines of the Mu'minites and Qasimites. The Imams of Qasimiten resided for some time in Qom until the 32th Imam to Anjedan moved, the de facto capital of the Shia in Persia. His grave mausoleum erected there can still be seen today. At the beginning of the 16th century, the Mongolian rule in Persia was ended by the local Safavid dynasty , which was also an important turning point for the Nizarites. Like them, the Safavids were Shiites, even if they belonged to the Twelve Shia, which in the meantime made up the majority of the population in Persia. However, the first Safavid Shah Ismail I (1487–1524) was open to the Nizarites. Her 35th Imam Abu Dharr Ali was even allowed to marry into the Shah family.

A turning point occurred, however, with the accession of Shah Tahmasp I (1514–1576), who established the doctrine of the Twelve Shia as the sole state religion in Persia and demanded that all subjects obey it, which exposed the Nizarites to a new threat. Her 36th Imam Murad Mirza was incarcerated in 1573 despite his relatives to the Shah. But in the same year he was able to escape after converting his jailer to Ismailism; but only a few months later he was captured again on his flight to Afghanistan and now executed before the Shah. Only a generation later, another political U-turn occurred. Shah Abbas the Great (1571–1629) stopped the persecution of the Nizarites and rehabilitated their 36th Imam Chalil Allah I by marrying a Safavid princess. To this end, the theological law school of Qom issued an edict in 1627 in which the Nizarites were recognized as members of the “house of believers” (dār al-muʾminīn) and privileged with a tax exemption. This edict is immortalized as an inscription on the facade of the mosque of Anjedan.

Under the 40th Imam Shah Nizar, the imam residence was relocated from Anjedan to the village of Kahak in the province of Qom . His mausoleum was built here. From the 42nd Imam Sayyid Hassan Ali onwards, the imams and with them their followers increasingly dropped the commandments of caution and from then on they again publicly acknowledged their beliefs. The Nizari-Schia then experienced a renaissance and a phase of reunification. Because at the end of the 18th century the last imam of the Mu'mini-Nizarites in India was missing. In the search for a new imam, almost all Mu'imites joined the still existing Qasimite lineage in the following decades, largely overcoming the division of the Nizarites that occurred after 1310. Only a small Mu'imite community in Syria (Masyaf) has remained independent, now with a hidden imam. The increasing political influence of the Nizarites under the new ruling dynasty of the Qajars , however, provoked fierce opposition from conservative representatives of the Twelve Shia. In 1817 the 45th Imam Shah Chalil Allah III. lynched by an angry crowd at his residence in Yazd along with some relatives . He was the last imam to be buried on Persian soil in Najaf .

The modern Ismailis

The following Imam Hassan Ali Shah (1804-1881) was a young man, the friendship of Fath Ali Shah enjoyed (1771-1834), of which he is a daughter in marriage and the Persian noble title "Sir Duke" ( Āghā Khān ) has been awarded which was passed on to all subsequent imams. In 1835, Aga Khan I was appointed as Imam by Mohammed Shah (1810-1848) as governor of the province of Kerman , where he was able to restore public order after the unrest of the change of dynasty in Persia and repel the repeated attacks by the Afghans. However, when the Shah wanted to relieve him of this post in 1837 in favor of a royal prince, the imam became a long-time rebel. Ultimately defeated by the government troops, he fled with his family and many supporters to Kandahar, Afghanistan in 1841 . With this, the Nicarite imamate has left his Persian homeland after more than seven hundred years of existence. In Afghanistan, the imam sought proximity to the British authorities who had occupied the country a few years earlier. He supported them in taking Sindh , for which he was granted an annual allowance. Eventually he moved into his new residence in Calcutta , British India , where he achieved the social recognition of the British. Among other things, the future King Edward VII († 1910) visited him here .

Since the Middle Ages, there has been an important Ismaili Shia on the Indian subcontinent , which, unlike in Egypt, Syria or Persia, was not exposed to any noteworthy persecution and was consequently able to prosper and preserve its written heritage into modern times. When the Ismaili schism broke out, the majority of the Indian community had embraced Nizar's supporters. The Indian Nizarites have organized themselves in their own communal associations, the Chodschas, each of which was headed by a self-chosen Mukhi (mukī) as the social and religious head. The arrival of their imam had, however, caused a certain unrest in the Indian community, as they had got used to the form of self-government that had existed for centuries. But by virtue of a judgment of the British High Court in Bombay in 1866 the status of the Imam as the holder of both spiritual and secular authority over the entire community of the "Shia Imami Ismailis" was confirmed, giving him absolute power over their political organization and their material and affairs financial property was transferred. Since then, this status has not been questioned within the community.

Under the brief reign of Aga Khan II , Aqa Ali Shah (1830–1885), the communicative and administrative networking of the Ismailis with their followers outside India was established. The imams' philanthropic and social commitment also began with him. Aga Khan III. , Sultan Muhammad Shah (1877–1957), was the first imam born in India. He has made several trips to Europe and made the acquaintance of Queen Victoria and Kaiser Wilhelm II . Six hundred years after Marco Polo's travels, the Christian West made his direct acquaintance with the "old man from the mountains", to whom it has given the highest ceremonial honors. His successor son Aga Khan IV. Was born in 1936 in the mountains of Switzerland . As the first imam, Aga Khan III. also traveled to the Ismaili communities of East Africa. In 1931 he opened his private libraries to the Russian exile Vladimir A. Ivanov († 1970) for systematic cataloging and thus paved the way for scientific research on the Ismailis on the basis of their own traditional documents. This research was instrumental in overcoming the assassin legend, which was uncritically reproduced in European science until the late 19th century, and replaced it with solid historical facts. Ivanov's work is continued today in the Institute of Ismaili Studies , founded by Aga Khan IV in London in 1977 , which has the world's largest collection of Ismaili writings in Arabic, Persian and Indian.

List of Ismaili / Nizarite imams

- Ali (X 661)

- Hussein (X 680)

- Ali Zain al-Abidin († 713) - split off from the Zaidites

- Muhammad al-Baqir († 732/36)

- Jafar as-Sadiq († 765) - splitting off of the twelve

- Ismail al-Mubarak († 760)

- Muhammad al-Maktum († 809)

- Abdallah al-Akbar (hidden)

- Ahmad (hidden)

- Hussein (hidden; † 882/883)

- al-Mahdi († 934) - secession of the Qarmatians

- al-Qa'im († 946)

- al-Mansur († 953)

- al-Mu'izz († 975)

- al-Aziz († 996)

- al-Hakim († 1021) - splitting off of the Druze

- az-Zahir († 1036)

- al-Mustansir († 1094) - splitting off of the Mustalites / Tayyibites and Hafizites

- Nizar (X 1095)

- Ali al-Hadi (hidden)

- Muhammad I. al-Muhtadi (hidden)

- Hassan I. al-Qahir (hidden)

- Hassan II ala dhikrihi s-salam (X 1166)

- Only ad-Din Muhammad II († 1210)

- Jalal ad-Din Hassan III. († 1221)

- Ala ad-Din Muhammad III. (X 1255)

- Rukn ad-Din Churschah (X 1257)

- Shams ad-Din Muhammad († 1310) - secession of the Mu'minites

- Qasim Shah († approx. 1370)

- Islam Shah († approx. 1425)

- Muhammad

- Ali Shah Mustansir († 1480)

- Abd al-Salam Shah

- Abbas Shah Mustansir († 1498)

- Abu Dharr Ali

- Murad Mirza (X 1574)

- Chalil Allah I († 1634)

- Nur al-Dahr Ali († 1671)

- Chalil Allah II († 1680)

- Shah Nizar († 1722)

- Sayyid Ali († 1754)

- Sayyid Hassan Ali

- Qasim Ali

- Abu'l-Hassan Ali († 1792)

- Shah Khalil Allah III. (X 1817)

- Hassan Ali Shah, Aga Khan I († 1881)

- Aqa Ali Shah, Aga Khan II. († 1885)

- Sultan Muhammad Shah, Aga Khan III. († 1957)

- Shah Karim al-Hussaini, Aga Khan IV.

literature

- Max van Berchem , Epigraphie des Assassins de Syrie, in: Journal asiatique, 9th Série (1897), pp. 453–501.

- Farhad Daftary , The Ismāʿīlīs: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Farhad Daftary, The Assassin Legends: Myths of the Ismaʿilis. London, 1994.

- Farhad Daftary, Ismaili Literature: A Bibliography of Sources and Studies. London, 2004.

- Heinz Halm , caliphs and assassins. Egypt and the Middle East at the time of the First Crusades 1074–1171. Munich: CH Beck, 2014.

- Heinz Halm, The Assassins. History of an Islamic secret society . Beck'sche Reihe, 2868. CH Beck, Munich 2017.

- Jerzy Hauziński, The Syrian Nizārī Ismāʿīlīs after the Fall of Alamūt. Imāmate's Dilemma, in: Rocznik Orientalistyczny, Vol. 64, (2011), pp. 174-185.

- Jerzy Hauziński, Three Excerpts Quoting a Term al-ḥašīšiyya, in: Rocznik Orientalistyczny, Vol. 69, (2016), pp. 89-93.

- Hans Martin Schaller , King Manfred and the Assassins, in: German Archives for Research into the Middle Ages , Vol. 21 (1965), pp. 173–193.

- Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy , Mémoire sur la dynastie des Assassins, et sur l'étymologie de leur nom, in: Annales des Voyages, Vol. 8 (1809), pp. 325–343; Republished in: Mémoires de l'Institut Royal de France, Vol. 4 (1818), pp. 1-84.

- Samuel M. Stern, The Epistle of the Fatimid Caliph al-Āmir (al-Hidāya al-Āmiriyya): its date and its purpose, in: The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (1950), p. 20 -31.

- Shafique N. Virani, The Eagle Returns: Evidence of Continued Isma'ili Activity at Alamut and in the South Caspian Region Following the Mongol Conquests, in: Journal of the American Oriental Society, Vol. 123 (2003), pp. 351-370 .

- Paul E. Walker, Succession to Rule in the Shiite Caliphate, in: Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, Vol. 32 (1995), pp. 239-264.

References and comments

- ↑ a b www.spiegel.de - Allah's gentle revolutionary (December 30, 2002), accessed on July 20, 2017.

- ↑ Al-Ḥaqq is one of the most important names of God (cf. also al-Hallādsch ).

- ↑ Cf. Guillaume Pauthier: Le livre de Marco Polo, citoyen de Venise, conseiller privé et commissaire impérial de Khoubilai-Khaân. Paris, 1865. p. 98, note 2.