Saalburg Castle

| Saalburg Castle | |

|---|---|

| limes | ORL 11 ( RLK ) |

| Route (RLK) |

Upper German Limes , Hochtaunus route |

| Dating (occupancy) | A.1) - A.2) by 85/90 to 90/100 B) by 90/100 to 135 C.1) by 135 to 155/160 C.2) by 155/160 to max. 260 |

| Type | A.1) - A.2) Schanzen B) Numerus fort C) Cohort fort |

| unit | A) unknown vexillations B) unknown number C.1) - C.2) Cohors II Raetorum civium Romanorum |

| size | A.1) 0.11 ha A.2)? B) 0.7 ha C.1) - C.2) 3.2 ha |

| Construction | A.1) - A.2) earth with wattle B) wood-earth fort C.1) wood / stone wall C.2) mortar stone wall |

| State of preservation | reconstructed |

| place | Bad Homburg vor der Höhe |

| Geographical location | 50 ° 16 ′ 17.5 ″ N , 8 ° 34 ′ 0 ″ E |

| height | 418 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Heidenstock small fort (southwest) |

| Subsequently | Lochmühle fort (northeast) |

The Saalburg fort is a former fort of the Roman Limes located on the Taunus ridge northwest of Bad Homburg vor der Höhe . The cohort fort is located immediately west of today's federal highway 456 , about halfway between the city of Bad Homburg vor der Höhe and the community of Wehrheim in the Hochtaunus district . It is considered to be the best-researched and most completely reconstructed fort of the Upper German-Raetian Limes , which has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 2005 .

The Saalburg is one of two houses of the Archaeological State Museum Hessen (ALMhessen). In addition to an archaeological museum, the Saalburg also has an archaeological park and a research center. The museum functions as the central Hessian state museum for the archeology of the Roman provinces and also houses the central Limes information center for Hesse.

location

The Saalburg Castle is around 418 m above sea level. NHN on the leading from WSW to ENE ridge of the Taunus . Even in prehistoric times, trade routes such as the Lindenweg (also known as the Linienweg), starting at the mouth of the Nidda near Frankfurt-Höchst , led from the Rhine-Main plain over the small mountain saddle on this Taunus ridge , the so-called Saalburg Pass , which is still today uses federal road 456 to cross the Taunus into the Usinger Basin , which has been relatively densely populated since the ceramic era . Of traffic-geographical importance also almost always meant of strategic importance and so it is not surprising that there were two simple earth entrenchments (so-called entrenchments A and B, probably already in the time of the Chat Wars (83 to 85) of Emperor Domitian (81–96) between the restored fort and today's federal road) were built by the Roman troops to secure this Taunus pass.

Today the site, which was formerly used for military purposes, is located in a forest area immediately west of the federal highway 456, several kilometers away from the modern settlement areas Obernhain (almost two kilometers), Saalburgsiedlung (almost two kilometers), Wehrheim (a good three kilometers) and Bad Homburg vor der Höhe ( around six kilometers).

Research history

During the Middle Ages and well into modern times, the ruins of the Saalburg were used as a quarry (among other things for building the church of the Thron monastery near Wehrheim ). It was only Elias Neuhof , Hesse-Homburg government councilor and builder of today's Sinclair House in Bad Homburg, who recognized the Roman origin of the ruins and identified them in 1747 as the “Roman Schanze”. He summarized the results of his observations and research between 1747 and 1777 in various publications, most of which, however, have been lost. Thanks to Neuhof, a certain sense of the building's worthy of protection developed for the first time in educated circles, but the stone robbery could only be ended by a decree of Landgrave Friedrich V of Hessen-Homburg in 1818 , immediately before that, in the years between 1816 and in 1818, the Saalburg had been declared a quarry by the city administration of Homburg. For better protection, Landgrave Friedrich VI bought the facility in 1820 .

It was not until 1841 that Friedrich Gustav Habel (1793–1867), the former archivist of the Wiesbaden State Library, received permission from Landgrave Philipp to carry out further research in the area of the Saalburg. Studies carried out by the Nassau Antiquities Association from 1853 to 1862 were also under Habel's direction. In the years that followed, a newly founded Saalburg commission primarily carried out conservation measures on the ruins until Karl August von Cohausen was given responsibility for the excavation in the area of the Saalburg in 1870 . The interest that was awakened by Cohausen's activities led to the founding of the Saalburg Association in 1872, the aim of which was to support further excavations and the establishment of a separate museum for the Saalburg finds. After von Cohausen, in his capacity as Royal Conservator for the Prussian province of Hessen-Nassau, devoted himself more and more to other activities around the Limes and elsewhere in the course of the 1870s , his previous colleague, the Homburg building advisor Louis Jacobi, increasingly took over Cohausen Function and management of the excavations at the fort.

When the Reichs-Limeskommission (RLK) under the direction of Theodor Mommsen began to research the complete course of the Limes and the locations of its forts in Germany in 1892 , Louis Jacobi and his son Heinrich Jacobi (1866-1946), who later became long-standing Head of the Saalburg Museum, track commissioners. As part of this extensive project, which took decades to complete, the archaeological activities in the Saalburg area were further intensified. In the end, it was L. Jacobi who persuaded Wilhelm II in 1897 to initiate the reconstruction of the Saalburg Fort under his leadership from 1897 on the basis of the extensive excavation finds. The foundation stone was laid on October 11, 1900, although L. Jacobi had already started the reconstruction work in 1885 by rebuilding the southwest corner of the defensive wall.

- Reconstruction work from 1885 to 1900

In the years that followed, up to around 1907, the most fully reconstructed fortress in the entire Limes was built, which, along with the Saalburg Museum, is probably the most important institution of this type for German Limes research alongside the Aalen Limes Museum. L. Jacobi's successor was his son Heinrich, who ran the museum from 1912 to 1936 and then provisionally from 1945 to 1946.

Heinrich Jacobi died in 1946, which meant that the management could not initially be filled in the post-war period. The Saalburg was managed on an interim basis by Ferdinand Kutsch from Wiesbaden in 1947/48 . The holdings of the Oberursel engine factory that were moved to the museum buildings as well as the looting of museum holdings in the last days of the war prevented the museum from operating properly. In 1948 the position was filled with the prehistorian Hans Schönberger . Under Schönberger's direction, the Saalburg became a real magnet for visitors again. While only 50,000 visitors were registered in 1947, when he switched to the management of the Roman-Germanic Commission in 1966, it was around 230,000.

Under Hans Schönberger, the Saalburg became a nationally important research center on the Limes. The museum carried out excavations in the castles Echzell , Altenstadt and Heilbronn-Böckingen . In 1964 the 6th International Limes Congress took place in Germany for the first time since the war. The Saalburg guide was translated into English by the well-known British Limes researcher Eric Birley .

From 1967 to 1993 Dietwulf Baatz , one of the most important provincial Roman archaeologists of the second half of the 20th century, was the director of the Saalburg Museum . Egon Schallmayer has held this office since 1995 . In 2013 he retired, and Carsten Amrhein became his successor as Saalburg director .

history

Following the two earthworks of the Domitian wars, a simple wood-earth fort was built for a numerus towards the north towards the Limes around the year 90 CE . A number was an auxiliary troop unit that normally consisted of two centuries , i.e. a nominal strength of around 160 men. Isolated finds suggest that the number of the Saalburg could have been a number Brittonum , i.e. a unit that was originally recruited in Britain, but this assumption is not really certain.

In late Hadrian times , around the year 135, the numerus fort was replaced by a 3.2 hectare camp for a cohort , an infantry unit of almost 500 men. The floor plan of this fort was now aligned with the Roman city of Nida and initially provided with a wood-stone wall built using drywall construction, which was only replaced by a mortared stone wall with an earth ramp in the second half of the 2nd century. This final construction phase also corresponds to the reconstruction of the fort with its dimensions of 147 by 221 meters. Fragments of the dry stone wall can still be seen in the Retentura (rear area of the fort) and a section of the defensive moat belonging to the wood-earth fort was left open or restored and can be viewed there.

The crew of the cohort fort, probably the Legion command in Mogontiacum ( Mainz shelter) was that Cohors II Raetorum civium Romanorum ( "second cohort of Rhaetians Roman citizenship"), which is a nearly 500-strong infantry unit. The cohort was originally located in Aquae Mattiacorum (Wiesbaden) and from there, after being stationed again in Fort Butzbach (ORL 14), was finally commanded to the Saalburg.

The fort existed in this form and with this occupation until the fall of the Limes around the year 260. The name of the unit is mentioned again and again in stone inscriptions during this time and the names of individual commanders have come down to us in this way.

At the beginning of the 3rd century, times on the Limes became more restless. A preventive war of the Roman Emperor Caracalla , who in 213 of Raetien and Mogontiacum (Mainz) made against the Alemanni and their allies chat pushed forward, reduced the pressure on the Germanic frontier temporary. Nida (today Frankfurt-Heddernheim ), the backward civilian capital of the Civitas Taunensium received a fortification ring and as early as 233 the Alemanni invaded Roman areas again. There were further major Alemannic incursions in 254 and 260. Finally, the entire area on the right bank of the Rhine was lost in the middle of the third century during the internal and external political and economic crisis of the empire . In connection with these events, the Saalburg fort seems to have been evacuated as planned without fighting.

After the end of the Upper Germanic Limes, the dilapidated fort was used as a quarry until the protection measures and excavation activities began around the middle of the 19th century.

Fort

Earliest fort buildings (Schanzen A and B)

The earliest military installations on the mountain saddle of the Saalburg are two simple earthworks, the so-called "Schanze A" and "Schanze B". They are located approximately at the level of the Retentura (rear storage area) of the cohort fort, around 60 to 80 meters east of it. The two small forts were discovered by chance in 1908 when the forest there was cleared.

In 1913, as part of one of the first experimental archaeological actions in research history , the two forts were completely rebuilt by two pioneer battalions northwest of the actual fort site, in the area of the "Dreimühlenborn". The traces of these systems are still clearly noticeable in the area today.

Schanze A (Vexillation Fort)

"Schanze A", located to the north, is the older of the two facilities. It had an irregular, pentagonal ground plan due to a bevel on the northeast side. With an average of around 42 m by 38.5 m side length, the entire facility took up an area of almost 1,600 m² (= 0.16 ha), whereas the usable interior area was just under 1,200 m² (= 0.12 ha). On the top of the wall was a wattle fence, against which the excavation of the defensive trench had been poured. There was no battlement behind it. The simple ditch, 1.50 m to 1.80 m wide and 0.80 m to 0.90 cm deep, encircled the entire fort and only continued in front of the only one on the south side of the fort and from the central axis of the camp right shifted gate briefly. In front of the ditch, traces of another wattle fence were discovered that ran around the entire camp. It was interpreted as the defense of a provisional older camp, whose crew could have built "Schanze A".

The troops were probably accommodated in tents that were probably located in the western three quarters of the interior. One can assume a maximum of ten team tents with eight soldiers each, as well as one additional tent for the commander of the unit, so that the troops were the size of a centurion, i.e. about 80 men plus batches. The eastern quarter of the inner area of the camp was probably reserved for the accommodation of pack animals and riding animals, as the drinking and drainage channels that have been proven in this fort area speak for. There were several ovens in the northwest corner of the camp.

The ski jump was hidden in the mixed forest not far from a pass over the Taunus ridge. It was probably created under Domitian during the wars against the Chatti in the years 83 to 85 AD. However, in view of the low loss of material that usually exists in short-term tent camps and therefore also low finds, an earlier, Vespasian foundation cannot be entirely ruled out.

Schanze B (Vexillation Fort)

"Schanze B", about 28.50 m south of "Schanze A", is younger and had an approximately square floor plan of around 44 m by 46 m, which means that it covered a total area of over 2,000 m². After deducting all obstacles to the approach (ditches and ramparts), only a usable inner area of 300 m² (17 m by 19 m) remained. The facility was surrounded by a double pointed trench, the individual trenches of which were each 2.80 m wide and 1.20 m deep. On the 1.50 m wide ridge between the two trenches, a shallow and only 15 to 30 cm wide trench was detected. At this point there was probably a wattle fence as an additional obstacle to approach. A berm towards the fort was completely missing, the inner slope of the inner trench merged without offset into the outer slope of the wall, which carried another wattle fence as parapet and the battlement behind it. In front of the only gate of the fort that faced north, towards the Limes, the trenches were exposed. The gate was around five meters wide and could have had a tower-like structure.

The Via Sagularis (Lagerringstrasse) ran between the walls and the inner buildings . The development itself probably consisted of a single, U-shaped building with a paved or graveled inner courtyard, opening towards the gate. The wings of the building could each have contained four to five contubernia , the rear part of the building probably consisted of the living quarters of the centurion .

Like "Schanze A", "Schanze B" should also have provided space for a vexillatio the size of a centurion, i.e. for a crew of around 80. In contrast to Schanze A, however, it was a facility that had apparently been designed for a long-term occupancy period from the start.

Numeruskastell (wood-earth fort)

The wood-earth fort or earth fort, as it was also called in older literature, is the earliest camp at the place where the cohort fort was later to be built. It had a rectangular floor plan. With its central, north-south longitudinal axis of 84.40 m and an east-west transverse axis of 79.80 m in length, it took up an area of just over 6,700 m².

The defensive wall, which was built entirely in a wood-earth construction method and rounded at the corners of the fort, consisted of a pile of earth stabilized on the inside with wooden posts and consolidated on the outside with turf and wattle. Most of the earth for this purpose probably came from the excavation of the defensive moat in front of the wall - and only separated from it by a 0.60 m to 0.70 m wide berm. This trench had the shape of a so-called fossa punica , so it was steeper on the enemy side than on the fort side. Overall, it was an average of two meters deep, its bottom was provided with a narrow, at least partially lined with wooden planks, the drainage channel of which led to the north. The width of the moat varied between five and six meters.

At the corners of the fence, as well as in the middle of the east and west side, a total of four corner and two side towers (or tower scaffolding in open construction) could be inserted through post holes up to 1.25 m deep and three by three meters each be detected. There were two fort gates, one on the north and one on the south, both with a width of 3.60 m. The northern gate facing the Limes must be addressed as porta praetoria (main gate). In front of him the course of the trench ceased and the earth bridge formed by this interruption was protected by a section of trench, a so-called titulum , nine to ten meters long, a good three meters long. At the porta decumana (rear gate), on the other hand, the ditch only narrowed, but ran uninterruptedly.

The approximately three meter wide via sagularis (Wallinnenstrasse, Lagerringstrasse) was connected to the inner side of the wall, which was delimited to the built-up part of the inner area of the warehouse by a 30 cm wide, timber-paneled and planked road ditch. After subtracting the area used by the fencing and via sagularis, there remained a buildable interior area of around 4200 m². Little is known of the actual interior development. Regular postings in the eastern part of the Retentura (rear part of the camp) make team barracks in this area likely - also in analogy to other numerus castles, especially those of the Odenwald Limes. Some fire places indicate possible further locations of barracks. A paving in the center of the camp, shifted a little to the east from the central axis, was mentioned by L. Jacobi as a possible location of the flag sanctuary ( aedes or sacellum ), interpreted by Egon Schallmayer as the place of the tribunal, but such interpretations must be considered remain hypothetical due to the unclear findings and lack of clear findings. The function of a 1.50 m deep water basin of 3.90 m by 4.50 m length with a five-step staircase on the south side also remains unclear.

To the north-northeast outside of the wood-earth fort (in an area that was later formed by the retentura (rear part of the camp) of the cohort fort , not far from its Porta decumana ) was the associated fort bath . It was a block type bath, i. H. the individual rooms of the bath drain were arranged side by side in two axes. While the apodyterium (changing room) and the frigidarium (cold bathing room) together with the cold water basin were in the eastern half, the tepidarium (leaf room ), the caldarium (hot bathing room) and the praefurnium (furnace) were located on the western side .

The finds that can be assigned to the earth fort made a good dating possible. According to the finds, the facility was built between the years 90 and 100 AD and was systematically cleared, laid down and leveled around the mid-thirties of the second century. An As of Hadrian (117-138) from the backfilling of the ditch can be used as the terminus post quem . As a result of the relatively long occupation, a small vicus could develop, which mainly extended south of the fort. An estimated 350 to 450 people must have lived here.

Cohort fort (wood-stone fort and stone fort)

Wood and stone fort

The enlargement of the garrison and the associated establishment of a cohort fort with a numerus fort is part of a fundamental restructuring of the Limes in Hadrianic times. The first camp built by the new cohort had a fence made of wood and stones laid without mortar and is therefore also known as the “wood-stone fort”. In addition to size and construction, its orientation was the most obvious new feature: the praetorial front was no longer oriented towards the Limes, but was oriented towards the south, towards Nida . The wood and stone fort covered an area of around 3.2 hectares. Its enclosure consisted of two 0.8 m wide quarry stone walls that ran parallel to each other at a distance of 2.3 m and the space in between was filled with rubble and earth. The whole thing was stabilized with a construction of 20 cm by 50 cm thick beams, which connected the dry stone walls with one another at regular intervals. The upper end was formed by a - possibly roofed - battlements. In front of the wall, a three-meter-wide berm and an eight-meter-wide pointed ditch served as an obstacle to the approach. There was no embankment on the inside, access was via a total of 24 narrow ramps. A total of 19 ovens between 1.5 m and 1.8 m in diameter were found at various points on the inside of the fence. L. Jacobi had denied the existence of corner and gate towers, but today the existence of wooden towers is assumed.

The approximately three-meter-wide via sagularis (Lagerringstrasse) with a drainage ditch ran between the fence and the internal development .

Only faint traces of the interior development itself, mainly post holes, could be identified, which indicated a strong similarity between the older and the younger development.

Stone fort

The complex called "stone fort" was not a separate and / or completely newly built fort, but an expansion phase, in the course of which, in particular, the defensive wall, which is presumably in need of repair, as well as the building of the cohort fort serving the most important administrative and logistical purposes, was entirely were built of stone. This last expansion phase, roughly the same shape as it presents itself to the visitor in a reconstructed state, led to a rectangular, four-gate cohort fort, 147 meters wide and 221 meters long, typical of this Limes section.

Enclosure

The entire fort area of a good 3.25 hectares in size was surrounded by a mortar defensive wall, which was plastered on the outside and painted a mock masonry. Inside the fort there was a heaped earth ramp behind the wall, which the fort crew could use to get to the top of the wall. The corners of the wall were rounded and had no watchtowers, but all four gates were provided with double towers.

The foundation of the new wall had a width of 2.10 m to 1.80 m, tapering in steps towards the rising. The rising masonry, the remaining height of which was around 2.40 m at the time of the excavations, should originally have been around 4.80 m high. On its top it was provided with battlements, the distance from each other was 1.50 m. The relatively large distance between the battlements is explained by the type of armament (hand throwing and slinging weapons), which required a certain amount of free space. In this respect, the reconstruction that is visible today, which was based on the findings of the last building phase, but whose significantly narrower pinnacle spacing, contrary to the excavation findings and contrary to the original design at the explicit request of Kaiser Wilhelm II, was flawed.

A double pointed ditch, which surrounded the fort after a 90 cm wide bench, served as an obstacle to the approach . The inner pointed trench reached a width of between 8.00 m and 8.75 m at a depth of around three meters, the outer trench was almost ten meters wide at 2.5 m to 3.0 m. In front of the gates the trenches were interrupted in most places by an earth bridge. Where this was not the case, wooden bridges enabled access to the interior of the fort. The function of two larger interruptions in the outer ditch in the northern half of the castle's eastern side has not yet been clarified.

The gates were each designed with two flanking gate towers in a similar construction but different widths. The south-facing Porta Praetoria (main gate) had a double passage, each with a clearance of 3.36 m, divided by a central pillar. The Porta Decumana (rear warehouse gate), on the other hand, only had a single passage 2.8 m wide. The side gates, which were also only built with simple passages, differed only slightly in their widths at 3.66 m at the Porta principalis sinistra (left side gate) and 3.77 m at the Porta Principalis Dextra (right side gate).

Interior development

The renovation of the interior was essentially based on the layout of the previous fort; only the Horreum (storage building) experienced an approximate doubling of the original area.

The center of the fort was dominated by the large principia (staff building) with a roofed transverse hall. The dimensions of the main building complex of the Principia were 41 m by 58 m. The floor plan of the transverse hall adjoining to the south was 38.5 m by 11.5 m, which clearly covered the axis of the Via principalis (cross street that connected the two side gates). The relatively massive 85 cm to 95 cm foundations of the vestibule suggested an above-average room height, as was expressed in the reconstruction. During the excavations in the transverse hall, among other things, the remains of a tank statue were found, which could have come from the imperial statue once erected here. The fragments can be dated to the early 3rd century. One entered the hall either through a main gate located in the axis of Via Praetoria (Lagerhauptstrasse) or one of the two side gates located in the axis of Via principalis . The canopies that were pulled up over the gates in the reconstruction were supposed to protect the open gate leaves in bad weather. Five more gates led from the hall into an inner courtyard surrounded on all four sides by a porticus . Its reconstruction is incorrect in that it was presumably not open but covered. Inside the courtyard, two wells and a 5.2 m by 5.2 m installation with an indefinite function were verified.

In the Praetentura (front fort area) there was the Praetorium (residential building of the commandant) to the west of Via Praetoria and a large Horreum (storage building) to the east .

The rest of the fort area has to be imagined - in contrast to the current state - densely built with stables, warehouses, workshops and of course the crew accommodation with their communal rooms ( contubernia ) . Two of these team barracks have been reconstructed in the south-eastern part of the fort.

Detail of the horreum with pseudo-cuboid painting on the outside

Facilities of the cohort fort outside the enclosure

Fort bath

The Saalburg fort bath was located in front of the main gate west of the road leading to Nida-Heddernheim . During the excavation, the finding was initially interpreted as a “villa”. As part of the Wilhelmine restoration concept, a “Roman garden” after Pliny the Elder was created by the Homburg Taunus Club on the east side of the ruin in 1888 . The work was carried out by the Homburg court gardener Georg Karl Merle . Due to a lack of funds for the maintenance of the garden, it fell into disrepair a few years after it was set up.

Building description

In the fort is acted originally a Bad-line type, in which the individual bathing tracts hot bath ( caldarium ) , Laubad ( Tepidarium ) and the cold bath ( Frigidarium ) were arranged in series. The entire complex of the Saalburg thermal baths began in the east with a large transverse hall, which did not belong to the first construction phase, but was added at a later point in time, was laid down again relatively early and which is interpreted as a changing area ( apodyterium ) . In a later construction phase, a hypocausted room was drawn into the northern half of this apodyterium , which was interpreted as a "winter apodyterium". On the southern side, the changing area was presumably flanked by a latrine, which also belonged to a later construction period. The next room to the west consisted of a frigidarium and bathing pool ( Piscina ) in the south and a heated room, probably the sweat bath ( sudatorium ) , in the north. The third suite consisted of a tepidarium with a southern apse and a northern room of unclear purpose. The following flights consisted of only one room each, in sequence:

- another 12.5 m by 6.25 m large tepidarium with its own boiler room ,

- a large, north and south with apses piscinae contained, provided caldarium , which is followed

- Another, large and rectangular piscina in a separate room was connected.

In the west, the thermal baths were closed off by a large praefurnium .

Building history

Since the baths were mostly built together with the forts, the thermal baths of the Saalburg have a long period of use, which is also proven by several renovations. A sequence of the construction work becomes clear through the built-in stamped bricks. The oldest brick temple are the Legio VIII Augusta to you, followed by stamps of Legio XXII Primigenia , stationed here Cohors II Raetorum civium Romanorum ( "second cohort of Rhaetians Roman citizenship") and finally the youngest brick which the Cohors IIII Vindelicorum ( "4 . Vindeliker cohort ") from Großkrotzenburg .

Mansio

Immediately to the south-east of the thermal baths and directly on the arterial road from the fort to the south was another large and multi-phase building complex, which is interpreted as an accommodation house ( mansio ). Such mansiones were used to accommodate people traveling on behalf of the state and to change horses for the official postal service. Corresponding to this function, the room suites with the rooms serving as accommodation framed an inner courtyard, which served as a storage area for the touring carriages and to accommodate the riding animals. At least the rooms on the south side of the building could be heated. Since part of the building area was also used by the apodyterium of the fort baths, the mansio could only have been built after this part of the building was demolished in the second half of the second century. In the late period of the fort, the accommodation building was no longer used and was probably already partially demolished.

Vicus

The Saalburg is not only the most extensively restored Limes fort, it is also the only one whose vicus (civil settlement) has also been partially exposed and preserved. The part of the vicus that is visible today is essentially located south of the Saalburg on both sides of the Saalburgstrasse , which in Roman times connected the fort with Nida , the former main town of the Civitas Taunensium , which was also the location of another garrison at the rear.

The fort village began immediately outside the Porta Praetoria (main gate), at which there was a mansio (official accommodation building) and - a little set back - the bathing building for the soldiers. This was followed today in their foundations and cellars, preserved and partially reconstructed houses as well as possibly the also reconstructed remains of a Mithraeum (cult site of the god Mithras, very popular in Roman military circles ).

The research assumes that the extensive Saalburg complex (fort and vicus) was temporarily inhabited by up to 2,000 people (500 military and 1,500 civilians).

Burial grounds

Since no systematic plans of the necropolis in the vicinity of the fort and the vicus were made during the early archaeological investigations and the burial fields were excavated, it is unfortunately not possible to obtain and present a complete and complete picture of their exact location today. As usual, they will have been on the arterial roads of the fort and outside the settlement limits of the vicus . What is certain is that the largest cemetery was south of the fort, on both sides of the road to Nida . From the fact that there were no burials under the street itself, it can be concluded that the street was laid out at the same time as the fort and vicus . The graves were all cremation burials, some of which were bordered with stones or bricks. The cremation of the corpses probably took place in a central Ustrina , the cremation was then collected and buried in urns, which were often made of organic materials. The additions usually consisted of ceramic vessels, an oil lamp and a coin, occasionally more luxurious everyday objects (glass, bronze, etc.) and / or terracotta figures were added, among which the representation of a rooster was very common.

Older burial ground (vicus area)

The older burial ground consists of two complexes of findings, which were separated from each other by a 30 m wide strip in which no burials could be detected. Both complexes are located in the area of the vicus and are partially covered by this.

The northern findings consist of around 50 secured graves, the majority of which were excavated in 1909 and a few in 1969. The grave goods, including a sesterce and an ace of Hadrian, as well as terra sigillata of the forms of drag. 18/31 and drag. 35 , refer to the first half of the second century.

The southern evidence consists of around 40 graves, of which only 13 have been secured, which is due to the insufficient documentation in the excavation years 1933/1934. Among the additions were a Dupondius of Trajan, minted between 98 and 102, and Terra Sigillate of the Drag types . 18/31 and drag. 27 , whereby this field can also be assigned to the first half of the second century.

The entire cemetery was probably occupied during the time of the numerus fort and gradually built over at the beginning of the time of the cohort fort.

Younger burial ground (south of the vicus)

The cemetery south of the vicus is the main necropolis of both the cohort fort and the civilian settlement. A total of around 300 graves were discovered there, but only 26 of them can be clearly assigned. This is due to the fact that excavations in this area have been aimlessly and without sufficient documentation for two hundred years.

The small number of dating finds begins with an Ace by Antoninus Pius, which was struck between 140 and 144. The end date can be limited by a coin of Septimius Severus, a denarius of Julia Maesa, as well as a potter's stamp from the 3rd century. Overall, the younger burial ground is likely to have been occupied from the middle of the second to the middle of the third century.

G. Habel and L. Jacobi claim to have recognized a Ustrina in a finding from the younger burial ground. Today this interpretation is doubted. Due to the imprecise or missing documentation, a correct interpretation of the findings is absolutely not possible.

Burial house: The burial house is on the opposite side of the Saalburgchaussee. The grave house was built in 1872 as the first building on the Saalburg Pass with funds from the Saalburg Association founded in the same year. The house is located in the middle of the Roman burial ground of the Saalburg. On the one hand, it should provide a dignified environment for the grave equipment and inventories arising during the excavations. On the other hand, the building should give an impression of the appearance of the planned reconstruction of the Saalburg.

Grave enclosure (formerly so-called "Mithraeum")

On the southern edge of the vicus , H. Jacobi reconstructed a Mithraeum , a cult site of Mithras , directly at a spring . Although the existence of a sanctuary to the Persian god of light, who was very popular with soldiers throughout the empire, near a fort the size of the Saalburg is quite likely, it is not supported by any finds or findings at this point. A mithraeum like other places of worship can be postulated with a high degree of probability in the vicinity of the Saalburg, but their location remains completely uncertain. The finding, which Jacobi had interpreted as Mithraeum, consisted of two wall sections lying next to each other, between which a total of 33 closely spaced cremations had been recovered in 1872. The fact that a floor plan published in 1937 deviated from the plan first published in 1897 made Jacobi's interpretation even more dubious.

While Schönberger in 1957 and Schwertheim in 1974 had already formulated objections to the interpretation of the finding as mithraea, science today unanimously assumes that the finding is about the enclosure of a grave complex. Due to the additions to one of the graves, which consisted of a denarius from Julia Maesa , a TS jug of the Niederbieber 27 type and a sword of Germanic origin, the dating of this grave complex can be narrowed down to the extent that it was there in the first half of the third Century burials must have been made.

Surroundings of the Saalburg

Jupiter column

Not far south of the Saalburg is also a replica of a Jupiter column found in Mainz in 1904/05 . The replica was made by the Mainz sculptor Eduard Schmahl and completed in 1912. The approx. 12 m high Jupiter column is a listed building. The figure was renovated in 2011-2014.

Margherite stone

The Margherite stone next to the Mithraeum commemorates the visit to the Saalburg by Queen Margherita of Italy in 1905. It is a listed building.

Landgasthof Saalburg

The neighboring Landgasthof Saalburg has been a listed building since 2013, as it has an original interior from the German Empire .

Limes course from Kastell Saalburg to the small fort Lochmühle

From the height of the Saalburg Pass, the Limes descends relatively steeply to the small fort Lochmühle. It runs through primarily heavily forested terrain and loses more than 110 meters in altitude on its way.

| ORL | Name / place | Description / condition |

|---|---|---|

| ORL 11 | Saalburg Castle | see above |

| Limes crossing | ||

| Wp 3/67 | Presumed, but not archaeologically proven, tower site. | |

| Wp 3/68 | On the Frölichmann head | Tower site, consisting of two wooden towers and a stone tower.

The stone tower had an approximately square floor plan with a side length of 6.35 m to 6.55 m. The wall thickness was 60 cm. Immediately to the west of the stone tower, only 90 cm from its foundation pit, was the 1.90 m wide and 60 cm deep trench of a wooden tower. A coin of Caracalla was recovered from the narrow area between the stone tower and the western wooden tower . Immediately to the east of the stone tower, the stud posts and the moat of another wooden tower were found. The position of the tower post was excellently chosen. From here, the view extended from Wp 3/63 in the west to the towers of route 4, beyond the Köpperner Tal in the east, and in the north far into the Limes foreland. |

| Wp 3/69 | "On Bennerpfad" | Place a stone tower with a rectangular floor plan with an aspect ratio of 5.60 m to 5.80 m. The thickness of the masonry was 90 cm. The floor plan of the tower was not parallel, but slightly inclined to the Limes palisade. Its distance from the middle of the Limes trench was between 25 m and 26 m. For a study, the archaeologist Thomas Becker had an animal bone recovered as food waste from this watchtower site dated using the radiocarbon method and was able to write the piece to the years AD 141 +/- 48. A red deer bone from watchtower 3/69 shows the use of wild animals to feed the soldiers. However, domestic mammals were much more important. The cattle should be mentioned in the first place, sheep and goats as well as pigs were also important. As an extremely rare meat supplier, the bones of two horses were also found at this watchtower. |

| KK | Lochmühle fort | see main article small fort Lochmühle |

Monument protection

The Saalburg fort and the surrounding Limes complex have been part of the UNESCO World Heritage as a section of the Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes since 2005 . In addition, they are ground monuments according to the Hessian Monument Protection Act . Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to approval, and accidental finds are reported to the monument authorities.

Saalburg Museum

Even if the Saalburg appears primarily as an open-air facility and museum, it also fulfills a number of scientific functions that must initially remain hidden on a superficial visit.

Of course, the reconstructed fort with the complete enclosure, the principia (staff building) with the flag sanctuary (Aedes) and the roll call hall, the horreum ( granary ), the two team barracks with their contubernia ( communal rooms ) and the only partially restored residential building of the commandant ( Praetorium) .

In the Horreum there is also part of the informative exhibition rooms, the focus of which is on the presentation of cultural-historical as well as construction and military-technical aspects of Roman Germania. Further exhibits can be found in the Principia and the Fabrica, which was only reconstructed in 2008 .

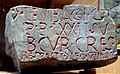

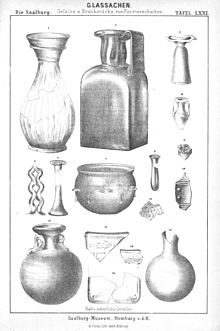

- Exhibits from the Saalburg Museum

Finds from the Mithraeum in Stockstadt

Bricks of the Legio XXII Primigenia

CIL 13, 7613a from Fort Zugmantel

In addition, the Saalburg has always been an internationally renowned research institute for provincial Roman archeology in general and for the investigation of the Limes in particular. The heart of this research facility is the specialist library with a stock of over 30,000 books and 2,200 slides. Numerous colloquia organized by the Saalburg Museum and, last but not least, the specialist publications published here round off the scientific work.

The office of the German Limes Commission, founded in 2003, is also located in the museum buildings.

Classical concerts have been held annually in the Saalburg by the Lions Club Friedrichsdorf-Limes since the early 1980s .

Directors

- 1897–1910 Louis Jacobi

- 1912–1935 Heinrich Jacobi

- 1935–1938 (provisional) Wilhelm Schleiermacher

- 1938–1939 (provisional) Joseph Alfs

- 1945–1946 Heinrich Jacobi

- 1948–1966 Hans Schönberger

- 1966–1993 Dietwulf Baatz

- 1995-2013 Egon Schallmayer

- since 2013 Carsten Amrhein

Saalburgbahn

In connection with the reconstruction at the end of the 19th / beginning of the 20th century, the interest of the population and the spa guests staying in Bad Homburg in the Saalburg increased. In order to ensure the most comfortable transport possible for visitors, the Saalburgbahn was built at the beginning of the 20th century by the Bad Homburg tram and opened on June 3, 1900. The tram - line was initially well received by the passengers and flourished before the First World War . After the war, demand fell, not least due to the massive drop in the number of spa guests. In addition, inflation was a major problem for Deutsche Bahn . Operations ceased on July 31, 1935. Apart from a few railway embankments in the forest, only the former train station building , which is somewhat remote and is not accessible to the public, remains. It was built based on a design by the Bad Homburg architect Louis Jacobi , who also reconstructed the Saalburg for Kaiser Wilhelm II . The Latin inscription is attached to the open half-timbered vestibule:

IUVET VOS SILVARUM UMBRA / MANSIO RAEDARUM SAALBURGIENSIUM / SALVETE HOSPITES

The Waldesschatten / Saalburg stop of the electric train will refresh you / Greetings guests

The station was at the apex of the Wendeschleife there . It was extensively restored in terms of monument conservation in 2005 and is now used for beekeeping and is a listed building .

Even today, the Saalburg can be reached by public transport . The city bus line 5 of the Bad Homburg city traffic, which also serves the Hessenpark on weekends , stops in the immediate vicinity of the fort. The Taunusbahn travels to Saalburg / Lochmühle station , which is about 1.2 km as the crow flies below the Taunus ridge .

See also

Literature (selection)

Monographs

The Roman fort Saalburg near Bad Homburg in front of the height. According to the results of the excavations and using the records left by the royal. Conservator Colonel A. von Cohausen .

Homburg in front of the height, 1897

- Cecilia Moneta: The Saalburg Fort. Evaluation of the old excavations . Zabern, Darmstadt 2018, ISBN 978-3-8053-5169-0 .

- Cecilia Moneta: The vicus of the Roman fort Saalburg . Zabern, Mainz 2010, ISBN 978-3-8053-4275-9 .

- Egon Schallmayer (Ed.): One hundred years of Saalburg. From the Roman border post to the European museum. Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2359-X .

- Margot Klee : The Saalburg (= guide to Hessian prehistory and early history 5). Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1205-8 .

- Erwin Schramm: The ancient artillery of the Saalburg. Reprint of the 1918 edition with an introduction by Dietwulf Baatz. Saalburg Museum, Bad Homburg v. d. H. 1980.

- Heinrich Jacobi : The Saalburg. Guide to the fort and its collections. 13th edition. Taunusbote, Bad Homburg 1937.

- Fritz Quilling: The Juppiter Column of Samus and Severus. The monument in Mainz and its replica on the Saalburg . Engelmann, Leipzig 1918.

- Ernst Heinrich Ferdinand Schulte: The Roman border fortifications in Germany and the Limes fort Saalburg . 3rd, amended and corrected edition. provided by J. Schoenemann. Bertelsmann, Gütersloh 1912.

- Karl August von Cohausen , Louis Jacobi : The Roman fort Saalburg. 5th edition. supplemented by Heinrich Jacobi based on the results of the last excavations . Staudt & Supp, Homburg v. d. H. 1900

- Louis Jacobi: The Roman fort Saalburg near Homburg in front of the height . Self-published, Homburg v. d. H. 1897.

- Georg Keller: The Saalburg Museum . Homburg, 1876.

- Karl Rossel: The Pfalgraben-Castell Salburg near Homburg vd H. Rossel, Wiesbaden 1871.

Essays / articles in compilations, series etc.

- Cecilia Moneta: The vicus of the Roman fort Saalburg. In: Vera Rupp , Heide Birley (Hrsg.): Country life in Roman Germany. Theiss, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-8062-2573-0 , pp. 78-81.

- Cecilia Moneta: The vicus of the Saalburg. An evaluation of the old excavation documentation. In: Peter Henrich (Ed.): Perspektiven der Limesforschung. 5th colloquium of the German Limes Commission . (= Guide to Hessian prehistory and early history. 5). Theiss, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8062-2465-8 , pp. 31-41.

- Margot Klee: The Roman Limes in Hessen. History and sites of the UNESCO World Heritage. Pustet, Regensburg 2009, ISBN 978-3-7917-2232-0 , pp. 103-109.

- Matthias Kliem, Egon Schallmayer u. a. (Ed.): The Romans in the Taunus. Societäts-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-7973-0955-4 .

- Egon Schallmayer : Saalburg. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 26, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2004, ISBN 3-11-017734 X , pp. 3–7.

- Dietwulf Baatz : Saalburg (Taunus) . Dietwulf Baatz and Fritz-Rudolf Herrmann: The Romans in Hesse. License issue. Nikol, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-933203-58-9 .

- Jens Peuser: On the reconstruction of the Saalburg fort. In: Saalburg yearbook. 51, 2001, pp. 243-306.

- Egon Schallmayer: The “amphitheater” of the Saalburg. Horse pond or aristocratic riding arena? In: Saalburg yearbook. 51, 2001, pp. 359-381.

- Dietwulf Baatz: The Roman Limes. Archaeological excursions between the Rhine and the Danube . Gebr. Mann, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-7861-2347-0 .

- Margot Klee: The Limes between Rhine and Main . Theiss, Stuttgart 1989, ISBN 3-8062-0276-1 .

- Dietwulf Baatz: The Saalburg. A Limes fort 80 years after the reconstruction. In: Günter Ulbert (Ed.): Conserved history? Ancient buildings and their preservation . Theiss, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-8062-0450-0 , pp. 117-129.

- Astrid Böhme: The fibulae of the castles Saalburg and Zugmantel . Saalburg-Jahrbuch 29, 1972, pp. 5–112.

- Hans Schönberger : Guide through the Roman fort Saalburg. 20th edition. Zeuner, Bad Homburg v. d. H. 1960.

- Heinrich Jacobi . In: Ernst Fabricius , Felix Hettner , Oscar von Sarwey (ed.): The Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes of the Roman Empire . Department B, Volume II, 1 Fort No. 11 Saalburg, 1937.

- Heinrich Jacobi: The earth fort of the Saalburg. In: Saalburg yearbook. 6, 1914-1924, pp. 85-155 as well as panels II, III and XVI.

- Heinrich Jacobi: Saalburg Castle. In: Saalburg yearbook. 4, 1913, pp. 7-113.

- Georg Wolff : In the footsteps of the Romans on the Main. In: Reclam's universe. Modern illustrated weekly. 29, 2 (1913), pp. 763-767.

Publication series

Since 1910 the has been published (with interruptions) once a year

-

Saalburg-Jahrbuch ,

a scientific periodical of provincial Roman archeology of international renown published by the Saalburg Museum. To date, over 50 volumes have been published.

The

-

Saalburg writings ,

some of which have popular scientific content, and are also aimed at a wider audience.

Web links

- Website of the Saalburg Museum

- Kastell Saalburg on the side of the German Limes Commission

- Kastell Saalburg on Verein Deutsche Limes-Straße ( Memento from June 21, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- Saalburg digital reconstruction and panorama

Remarks

- ↑ "The Saalburg, on this side of the Polgraben, is a square square, surrounded by a moat, and represents a fortune for the Romans."

- ↑ See also the inscription above the porta praetoria (main gate): GVILELMVS II FRIDERICI III FILIVS GVILELMI MAGNI NEPOS ANNO REGNI XV IN MEMORIAM ET HONOREM PARENTUM CASTELLVM LIMITIS ROMANI SAALBVRGENSE RESTITVIT. (Wilhelm II., Son of Friedrich III., Grandson of Wilhelm the Great, restored the Saalburg castle of the Roman Limes in the year 15 of his reign to commemorate and honor his ancestors.)

- ↑ "May the Roman fortress on the heights of the Taunus rebuilt as precisely as possible in Roman style, as a monument to the past rulers and momentous cultural development, revive the understanding of the essence of earlier times in the beholder, keep the historical sense alive and encourage further research." Kaiser Wilhelm II laying the foundation stone for the Principia on October 11, 1900 (according to Hartwig Schmidt : Reconstruction (Architecture Department of the German Archaeological Institute. Monument Preservation at Archaeological Sites Volume 2) . Theiss, Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-8062-0588-4 , p 216.

- ↑ a b For this reconstruction, Jacobi chose a wide pinnacle spacing, which he based on observations on the Tiberian wall of the Praetorian camp in Rome. This situation was only changed in 1898 in favor of the wrong, narrow spacing. Baatz suspects that the change can be traced back to a direct intervention by Wilhelm II, who controlled and partially changed all reconstruction plans and who was probably under the impression of late medieval castles.

- ↑ At 50 ° 16 ′ 21.97 ″ N , 8 ° 34 ′ 6.5 ″ E

- ↑ At 50 ° 16 ′ 19.78 ″ N , 8 ° 34 ′ 8.18 ″ E

- ↑ It is an older drawing, which means that the names of the buildings are sometimes incorrect today. The building marked “PRAETORIVM” is the Principia , the “QUAESTORIVM” is the Praetorium . The building called “VILLA” outside the fort is the thermal baths and the “MAGAZINE” is now usually referred to as the Horreum .

- ↑ Schallmayer, 100 Years of Saalburg, 1997, reconstructs the numerus fort of the Saalburg analogous to the Hesselbach fort

- ↑ Dietwulf Baatz only restored the historically correct distance between the battlements at a small point on the east wall.

- ↑ ORL = numbering of the Limes structures according to the publication of the Reich Limes Commission on the O bergermanisch- R ätischen- L imes

- ↑ ORL XY = consecutive numbering of the forts of the ORL

- ↑ Wp = W oh p east, watch tower. The number before the slash denotes the Limes section, the number after the slash denotes the respective watchtower. An additional asterisk (*) refers to a guard on the older Limes line.

- ↑ At 50 ° 16 '26.76 " N , 8 ° 34' 14.89" O .

- ↑ At 50 ° 16 '29.74 " N , 8 ° 34' 34.91" O .

- ↑ At 50 ° 16 '29.45 " N , 8 ° 34' 33.9" O .

- ↑ 50 ° 16 '29.94 " N , 8 ° 34' 35.97" O .

- ↑ At 50 ° 16 '43.38 " N , 8 ° 34' 56.15" O .

- ↑ KK = unnumbered K linseed K astell

- ↑ Table of contents of the previously published Saalburg yearbooks on the website of the Saalburg Museum, accessed on May 12, 2013.

Individual evidence

- Jump A at 50 ° 16 ′ 21.97 ″ N , 8 ° 34 ′ 6.5 ″ E and Hill B at 50 ° 16 ′ 19.78 ″ N , 8 ° 34 ′ 8.18 ″ E

- ↑ Hildegard Temporini, Wolfgang Haase: Rise and decline of the Roman world: History and culture of Rome in the mirror of recent research . Vol.?, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1976, ISBN 3-11-007197-5 , p.

- ↑ Elias Neuhof: Completed letters, news of two ancient Roman monuments found . Homburg vd H. 1747; Elias Neuhof: News of the antiquities in the area and on the mountains near Homburg in front of the height. Publishing house of Ev. reformed orphanage, Hanau 1777; Elias Neuhof: 2nd letter to Pastor Christ in Rodheim. In: Hanauisches Magazin. 15, 1783.

- ↑ State Office for the Preservation of Monuments Hesse (ed.): Saalburgchaussee o. No .: Saalburg In: DenkXweb, online edition of cultural monuments in Hesse

- ^ Margot Klee: The Saalburg . (= Guide to Hessian prehistory and early history. 5). Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1205-8 , p. 8.

- ^ Margot Klee: The Saalburg . Theiss, Stuttgart 1995. (= Guide to Hessian prehistory and early history. 5). ISBN 3-8062-1205-8 , p. 10.

- ↑ Dietwulf Baatz: The Saalburg - a Limes fort 80 years after the reconstruction. In: Günter Ulbert and Gerhard Weber: Preserved history? Ancient buildings and their preservation . Theiss, Stuttgart 1985, ISBN 3-8062-0450-0 , pp. 117-129.

- ↑ Gerhard Weber: "As faithfully as possible in Roman construction." On the reconstruction of the Saalburg. In: Egon Schallmayer (ed.): Hundert Jahre Saalburg. From the Roman border post to the European museum . Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2350-6 , pp. 119-125.

- ↑ Figures based on Dietwulf Baatz: Report of the Saalburg Museum for the years 1965–1966. In: Saalburg yearbook. 24, 1967, p. 7.

- ↑ Georg Wolff: The southern Wetterau in prehistoric times . (With an archaeological find map). Published by the Roman-Germanic Commission of the Imperial Archaeological Institute, pp. 5, 6, 72, 73, 75, 78–80, 90, 95. Ravenstein, Frankfurt am Main 1913.

- ↑ After Joachim von Elbe : Our Roman heritage . Umschau-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main, 1985, ISBN 3-524-65001-5 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 07457 , CIL 13, 07462 (p 126) , CIL 13, 07465 (p 126) , CIL 13, 07466 (4, p 126) and CIL 13, 07469 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 07445 , CIL 13, 07452 , CIL 13, 07460 (and CIL 13, 07470 ).

- ^ A b Heinrich Jacobi: Castle Saalburg. In: Saalburg-Jahrbuch 4, 1913, pp. 7–113 as well as panel II.

- ↑ a b ORL B, Vol. 2.1, Kastell 11, pp. 13-15.

- ^ Egon Schallmayer: Castles on the Limes. The development of the Roman military installations on the Saalburg Pass. In the S. (Ed.): One hundred years of Saalburg. From the Roman border post to the European museum. Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2359-X , pp. 108-109.

- ↑ a b c d Margot Klee: The Saalburg . (= Guide to Hessian prehistory and early history. 5). Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1205-8 , p. 28.

- ^ Egon Schallmayer: Castles on the Limes. The development of the Roman military installations on the Saalburg Pass. In the S. (Ed.): One hundred years of Saalburg. From the Roman border post to the European museum. Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2359-X , pp. 106-108.

- ↑ a b ORL B, Vol. 2.1, Kastell 11, pp. 15-19.

- ↑ ORL B, Vol. 2.1, Kastell 11, pp. 17f.

- ^ Egon Schallmayer: Castles on the Limes. The development of the Roman military installations on the Saalburg Pass. In the S. (Ed.): One hundred years of Saalburg. From the Roman border post to the European museum. Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2359-X , p. 110.

- ^ Margot Klee: The Saalburg . (= Guide to Hessian prehistory and early history. 5). Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1205-8 , p. 29f.

- ^ A b Egon Schallmayer: Fortresses on the Limes. The development of the Roman military installations on the Saalburg Pass. In the S. (Ed.): One hundred years of Saalburg. From the Roman border post to the European museum. Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2359-X , p. 111.

- ^ Heinrich Jacobi: The earth fort of the Saalburg. In: Saalburg yearbook. 6, 1914-1924, pp. 85-155 as well as panels II, III and XVI.

- ^ Egon Schallmayer: Castles on the Limes. The development of the Roman military installations on the Saalburg Pass. In the S. (Ed.): One hundred years of Saalburg. From the Roman border post to the European museum. Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2359-X , pp. 109–111.

- ^ Margot Klee: The Saalburg. (= Guide to Hessian prehistory and early history. 5). Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1205-8 , pp. 26-30.

- ^ Margot Klee: The Saalburg . (= Guide to Hessian prehistory and early history. 5). 2nd, supplemented edition. Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1205-8 , pp. 30-39.

- ^ Egon Schallmayer: Castles on the Limes. In the S. (Ed.): One hundred years of Saalburg. From the Roman border post to the European museum. Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2350-6 , p. 117; Margot Klee: The Saalburg . (= Guide to Hessian prehistory and early history. 5). 2nd, supplemented edition. Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1205-8 , p. 34.

- ^ Margot Klee: The Saalburg . (= Guide to Hessian prehistory and early history. 5). 2nd, supplemented edition. Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1205-8 , pp. 34-67.

- ^ Margot Klee: The Saalburg . (= Guide to Hessian prehistory and early history. 5). 2nd, supplemented edition. Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1205-8 , p. 36f.

- ^ Margot Klee: The Saalburg. (= Guide to Hessian prehistory and early history. 5). 2nd, supplemented edition. Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1205-8 , p. 37f. and Fig. 15.

- ↑ ORL B 2.1, No. 11 (1937), p. 34f .; Dietwulf Baatz: Limes Fort Saalburg. A guide through the Roman fort and its history . 1996, p. 24.

- ↑ a b c Margot Klee: The Saalburg (= guide to Hessian prehistory and early history 5). Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1205-8 , pp. 42-49.

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz ): Römische Kastelle . Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 131.

- ↑ Martin Kemkes: The image of the emperor on the border - A new large bronze fragment from the Raetian Limes. In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Research on the function of the Limes. Volume 2. Konrad Theiss Verlag, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2117-6 , p. 144.

- ^ Margot Klee: The Saalburg (= guide to Hessian prehistory and early history 5). Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1205-8 , p. 45.

- ↑ Bernd Modrow: Court gardener Merle and the influence of Prussia on garden art. In: SehensWerte Palaces & Gardens in Hessen 6/2010, p. 28f.

- ^ Margot Klee: The fort bath (thermae). In: Dies .: The Saalburg. (= Guide to Hessian prehistory and early history. 5). Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1205-8 , pp. 68-74.

- ^ Margot Klee: The Saalburg. Theiss, Stuttgart 1995. (= Guide to Hessian Pre- and Early History 5), p. 68f.

- ^ Margot Klee: The Saalburg. (= Guide to Hessian prehistory and early history. 5). Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, p. 70.

- ^ Margot Klee: The lodging house (mansio). In: Dies .: The Saalburg. Theiss, Stuttgart 1995. (= Guide to Hessian Pre- and Early History 5), ISBN 3-8062-1205-8 , pp. 74-77.

- ↑ Cecilia Moneta: The vicus of the Roman fort Saalburg . Zabern, Mainz 2010, ISBN 978-3-8053-4275-9 ; C. Sebastian Sommer: The Saalburg-vicus. New ideas on old plans. In: Egon Schallmayer: One hundred years of Saalburg . Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2350-6 , pp. 155-165; Margot Klee: The civil settlement near the Saalburg. In: Dies .: The Saalburg . 2nd, supplemented edition. 2000. Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1205-8 , pp. 123–142, (= Guide to Hessian Pre- and Early History. 5); Britta Rabold: Department store, forum, villa or what? A puzzling large building in the vicus of the Saalburg fort. In: Egon Schallmayer: One hundred years of Saalburg . Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2350-6 , pp. 166-169.

- ↑ Margot Klee: The grave fields. In: Dies .: The Saalburg. Theiss, Stuttgart 1995. (= Guide to Hessian Prehistory and Early History 5), ISBN 3-8062-1205-8 , p. 126f.

- ↑ Cecilia Moneta: The vicus of the Roman fort Saalburg . Zabern, Mainz 2010, ISBN 978-3-8053-4275-9 , p. 107.

- ↑ a b Cecilia Moneta: The vicus of the Roman fort Saalburg . Zabern, Mainz 2010, ISBN 978-3-8053-4275-9 , p. 107f.

- ↑ Cecilia Moneta: The vicus of the Roman fort Saalburg . Zabern, Mainz 2010, ISBN 978-3-8053-4275-9 , p. 108.

- ↑ Cecilia Moneta: The vicus of the Roman fort Saalburg . Zabern, Mainz 2010, ISBN 978-3-8053-4275-9 , p. 108f.

- ↑ From finding no. 6002; Cecilia Moneta: The vicus of the Roman fort Saalburg. Catalog . Zabern, Mainz 2010, ISBN 978-3-8053-4275-9 , p. 362f.

- ↑ From finding no. 2151; Cecilia Moneta: The vicus of the Roman fort Saalburg. Catalog . Zabern, Mainz 2010, ISBN 978-3-8053-4275-9 , p. 222.

- ↑ From finding no. 6001; Cecilia Moneta: The vicus of the Roman fort Saalburg. Catalog . Zabern, Mainz 2010, ISBN 978-3-8053-4275-9 , p. 362.

- ↑ Cecilia Moneta: The vicus of the Roman fort Saalburg . Zabern, Mainz 2010, ISBN 978-3-8053-4275-9 , p. 109.

- ↑ Finding no. 6011; Cecilia Moneta: The vicus of the Roman fort Saalburg. Catalog . Zabern, Mainz 2010, ISBN 978-3-8053-4275-9 , p. 364.

- ↑ Margot Klee: Mithraeum. In: Dies .: The Saalburg . (= Guide to Hessian prehistory and early history. 5). Theiss, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-8062-1205-8 , pp. 128-130.

- ^ Hans Schönberger: Preliminary remarks. In: Register for the Saalburg yearbooks I (1910) -XV (1956). Topographical Index I. Saalburg-Jahrbuch 16, 1957, p. 60.

- ↑ Elmar Schwertheim: The monuments of oriental deities in Roman Germany . (= Études Préliminaires aux Religiones Orientales dans L'Empire Romain 93), Brill, Leiden, 1974, p. 250f.

- ↑ a b Cecilia Moneta: The vicus of the Roman fort Saalburg . Zabern, Mainz 2010, ISBN 978-3-8053-4275-9 , p. 109f.

- ↑ Fritz Quilling: The Juppiter Column of Samus and Severus. The monument in Mainz and its replica on the Saalburg . Engelmann, Leipzig 1918.

- ↑ State Office for the Preservation of Monuments Hesse (ed.): Jupitersäule In: DenkXweb, online edition of cultural monuments in Hesse

- ↑ Carsten Amrhein, Elke Löhnig: Monument renovation . Jupiter shines in new splendor. In: The Limes. News bulletin of the German Limes Commission. 6th year, 2012, issue 2 (PDF; 2.7 MB), pp. 34–35.

- ↑ State Office for the Preservation of Monuments Hesse (ed.): Margheriten-Stein In: DenkXweb, online edition of cultural monuments in Hesse

- ↑ Ernst Fabricius , Felix Hettner , Oscar von Sarwey (ed.): The Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes of the Roman Empire . Dept. A, Volume II, 1 Lines 3 to 5 (1936). Route 3.

- ↑ Thomas Becker : Archaeozoological investigations on animal bone finds from watchtowers and small forts on the Limes . In: Peter Henrich (Ed.): The Limes from the Lower Rhine to the Danube. Contributions to the Limes World Heritage Site 6, 2012, pp. 157−175, here: p. 159.

- ↑ Thomas Becker : Archaeozoological investigations on animal bone finds from watchtowers and small forts on the Limes . In: Peter Henrich (Ed.): The Limes from the Lower Rhine to the Danube. Contributions to the Limes World Heritage Site 6, 2012, pp. 157–175, here: p. 160.

- ^ Egon Schallmayer (Ed.): Hundert Jahre Saalburg. From the Roman border post to the European museum. Zabern, Mainz 1997, ISBN 3-8053-2359-X ; Website of the Saalburg Museum .

- ↑ FVV information no. 1 and Walter Söhnlein: Saalburg terminus. In: From the city archive. 1999/2000 (2001), pp. 7-31.

- ↑ State Office for the Preservation of Monuments Hesse (Ed.): Station building of the Saalburgbahn In: DenkXweb, online edition of cultural monuments in Hesse