Pen food

The Essen Abbey was a women's abbey that existed from around 845 to 1803. The pen was the nucleus for the development of the city of Essen . The collegiate church, the Essen Minster , now serves as a cathedral for the Ruhr bishopric . The preserved church treasure includes some of the most important Ottonian works of art as well as art treasures from later eras.

history

The sources for the period up to around 946 are very unfavorable. Around this time the monastery burned down, damaging the church and destroying archives and the library. The monastery was founded before 850 by a group of aristocrats around the Saxon nobleman Altfrid († 874), the later Bishop of Hildesheim (851-874), near the royal court As [t] nidhi, from which the later name of pen and City derives. The first abbess was Gerswit, probably a relative of Altfrid. The first mention can be found in the third vita of Saint Liudger , the founder of the neighboring Werden Abbey , from around 864 , in the form of a miraculous healing report. The healed girl Amalburga had accordingly taken the veil and entered the monasterio sanctimonialium, quod Astnidhi appellatur . The founding clan probably died out with the abbess Gersuith II.

After that, the monastery was possibly the own monastery of the Hildesheim bishops. King Lothar II (855–869) gave the monastery the Villae Homberg and Kassel near Duisburg. Around 860, Ludwig the German gave the monastery a court association in Huckarde and other possessions that could not be located, as well as Salland with its court associations Archem, Olst and Irthe in the province of Overijssel . Charles III gave the monastery a vineyard near Godesberg , Zwentibold von Lothringen donated 898 areas on the left bank of the Rhine, which were lost again.

It soon became apparent that the Liudolfingers were interested in gaining influence in Essen. Duke Otto von Sachsen gave the monastery the Beeck Villication near Duisburg. The exact time at which the monastery became imperial is not certain, it was probably during the reign of King Conrad I (911–918).

The monastery experienced its heyday from the middle of the 10th century under five successive abbesses from the Liudolfinger family. Mathilde II , granddaughter of Emperor Otto I , ran the monastery from around 973 to 1011, under her the most important art treasures of the Essen cathedral treasure came to Essen. Her two predecessors, Hathwig and Ida, and her two successors, Sophia and Theophanu, also came from the Liudolfing family and thus increased the rank, wealth and influence of the monastery. In 1228 the abbess was first referred to as the princess . From 1300 onwards, the abbesses increasingly took up residence in Borbeck . They managed to develop a rule between the rivers Emscher and Ruhr , to which the city of Essen belonged. Their efforts to become a free imperial city were thwarted by the monastery in 1399 and finally in 1670.

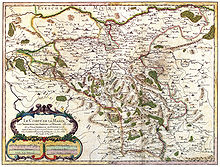

The Stoppenberg Monastery had been located in the north of the territory since 1073, and the Rellinghausen Abbey in the south . The property of the monastery also included the area around Huckarde , on the border with the county of Dortmund and separated from the Essen territory by the county of Mark . The monastery had around two to three thousand property titles in the area, in Vest Recklinghausen , on Hellweg as well as around Breisig and near Godesberg . A total of around 40 manors belonged to it, apart from Salland, up the Rhine to the area of Andernach and Breisig. There were also scattered properties in Westphalia and on the Lahn around Fronhausen south of Marburg .

From 1512 until it was dissolved, the imperial abbey belonged to the Lower Rhine-Westphalian Empire . The abbess had been a member of the Rhenish Prelate College since 1653 .

In 1495 the abbey signed a hereditary bailiff contract with the Dukes of Kleve and Mark, whereby the Essen monastery lost the right to choose a bailiff itself, and was therefore limited in its independence. From August 1802 the territory was occupied by Prussian troops. In the course of secularization , the monastery was dissolved in 1803. The three square mile area of the spiritual territory went to Prussia in 1803 , belonged to the Grand Duchy of Berg from 1808 to 1813 , and then returned to the Kingdom of Prussia based on the resolutions passed at the Congress of Vienna . The last abbess, Maria Kunigunde of Saxony , died on April 8, 1826 in Dresden.

Research history

Scientific work on Essen Abbey began in the early modern period when the first abbess calendars were compiled from the necrological manuscript and other sources. By Jodocus Hermann Nünning two tracings of a lost manuscript of the abbess were Hathwig narrated Giles Gelenius handed the inscriptions of Marsus shrine .

After the dissolution of the monastery, the art historical preoccupation with the monastery treasure began in the 19th century, one of the first treatises on the treasure was written by Ernst aus'm Weerth in 1857. With the establishment of the historical association for the city and monastery of Essen , research activity intensified. Members of the association were Konrad Ribbeck , who edited the Essen necrological manuscript in 1900 , Franz Arens , who first treated the Liber Ordinarius of the monastery in 1901 , and Georg Humann , who published a work on the monastery treasury in 1904. From the establishment of the Essen Minster Association in 1947 and the first publication of its periodical Das Münster am Hellweg in 1948, articles on the history of the monastery were also published there. The diocese of Essen, founded in 1957, acknowledged the tradition of the women's foundation from the start; the custodians of the cathedral treasury, Leonard Küppers and Alfred Pothmann, supported the research.

From 2000 onwards, the Essen working group for research into women's pens was established as an interdisciplinary association of scientists. The conference volumes of the annual conferences are published as a series of publications from Essen's contributions to the women's foundation . Some monographs that are important for dealing with the Essen Abbey, some of them by members of the working group, appeared in the Sources and Studies series of the Institute for Research on Church History of the Diocese of Essen. The popular science book Macht in Frauenhand - 1000 Years of Rule of Noble Women in Essen , which was published for the fourth time in 2008, was also written by a member of the working group.

See also

- List of Abbesses of Essen

- List of the bailiffs of the Essen monastery

- City arms of Essen

- Portal: Holy Roman Empire / Essen Abbey

literature

- Katrinette Bodarwé, Thomas Schilp (ed.): Dominion, liturgy and space - studies on the medieval history of the women's monastery in Essen. Klartext Verlag, Essen 2002, ISBN 3-89861-133-7 .

- Günter Berghaus, Thomas Schilp, Michael Schlagheck (eds.): Dominion, education and prayer. Klartext Verlag, Essen 2000, ISBN 3-88474-907-2 .

- Jan Gerchow, Thomas Schilp (ed.): Food and the Saxon women's pencils in the early Middle Ages. Klartext Verlag, Essen 2003, ISBN 3-89861-238-4 .

- Martin Hoernes, Hedwig Röckelein (eds.): Gandersheim and Essen - Comparative studies on Saxon women's foundations , Klartext Verlag, Essen 2006, ISBN 3-89861-510-3 .

- Detlef Hopp : Archaeological traces in the early Essen monastery. (= Reports from the Essen Monument Preservation. Volume 11). City of Essen, Institute for Monument Protection and Preservation / Urban Archeology, Essen 2015 ( PDF ).

- Ute Küppers-Braun: Power in women's hands - 1000 years of rule by noble women in Essen . Essen 2002, ISBN 3-89861-106-X .

- Thomas Schilp : The manorial organization of the noble women's monastery in Essen. From the economic development to the political-administrative recording of space , in: Vergierter Zeiten. Middle Ages in the Ruhr Area (exhibition catalog), Vol. 2, ed. by Ferdinand Seibt, Gudrun Gleba, Heinrich Theodor Grütter, Herbert Lorenz, Jürgen Müller, Ludger Tewes, Essen 1990, pp. 89-92, ISBN 3-89355-052-6 .

- Thomas Schilp (Ed.): Reform - Reformation - Secularization. Women's pencils in times of crisis , Klartext Verlag, Essen 2004, ISBN 3-89861-373-9 .

- Thomas Schilp (edit.): Essener Urkundenbuch. Regesta of the documents of the women's monastery in Essen in the Middle Ages. Volume 1 from the foundation around 850 to 1350 , Droste Verlag, Düsseldorf 2010, ISBN 978-3-7700-7635-2 .

- Thomas Schilp (Ed.): Women build Europe. International links of the Essen women's monastery . Klartext Verlag, Essen 2011, ISBN 978-3-8375-0672-3 .

footnote

- ↑ Thomas Schilp: Altfrid or Gerswid? On the founding and beginnings of the Essen women's monastery . In: Günter Berghaus, Thomas Schilp, Michael Schlagheck (eds.): Dominion, education and prayer. Foundation and beginnings of the Essen women's monastery . Klartext Verlag, Essen 2000. pp. 29–42, here p. 34.