Kirtan

Kirtan ( Sanskrit कीर्तन , Hindi कीर्तन , Bengali কীর্তন , in IAST kīrtan , Tamil கீர்த்தனை , kīrtanam ) is a devotional style of singing in South Asia , in which usually a group of participants alternately singing religious and mythological topics in verse. The kirtan belongs especially to the Bhakti cult of Vishnuism and to the practice of faith in Sikhism . The Hindu Bhakti cult was originally a movement directed against the Brahmin elite and therefore used vernacular languages instead of classical Sanskrit in religious rituals. Kirtan are known in many regionally different styles, which are mainly derived from the formally strict north Indian singing tradition dhrupad . In a more general sense, regardless of form or as a formally simpler genre, religious songs are called bhajan .

Pada kirtan , performed by a cantor and companions seated in a circle on the floor, consists of mythical tales in verse about the life of a deity and occurs in variants throughout India. In Bengal are in Vishnuite padavali kirtan , the shape of Narottama This was introduced in the 1570s, mythical episodes from the life of Krishna presented. Katha kirtan (“telling stories”) combines narration, sung songs and instrumental music. The choral singing nam kirtan (also nagara kirtan, samkirtan or nam san kirtan ), which is popular throughout India , is based, like the dhikr in Sufism, on a constant rhythm and on endless repetitions of a divine name or a mantra . Nam kirtan is performed standing in the temple or often outside while walking. For Sikhs , the shabad kirtan is an essential part of the liturgy and is conscientiously performed according to a musical structure whose tone sequence is based on a raga . In Maharashtra , the warkari kirtan with a large choir differs from the rest of India through the combination of narration, music, dance and theatrical elements. In South India, the kirtanam is a genre of South Indian classical music .

Kirtan predecessors have the title kirtankar ("someone who does kirtan "). According to legend, the mythical sage Narada is considered to be the first kirtankar .

origin

Vedic origin

Sacred music goes back to the ancient Indian time of the Vedas , when the priests recited sacred words and syllables with magical meanings during ceremonies. The Upanishads , which emerged at the end of the Vedic period, contain modes of recitation and meters that were addressed to personified deities. The meter gayatri in Rigveda corresponded to the sun god Savitri , the meter tristubh to the then highest god Indra and the meter jagati to the subordinate wind deities called Maruts and later other gods. The Samaveda is about the melodies ( saman ) of the verses. The vocal parts were supplemented by a syllable mumbled by several singers in the lowest register. This was apparently a drone accompaniment that is still an essential element of Indian music today. Since ancient Indian times, singing that is purely vocal or accompanied by a few instruments has been considered culturally higher than instrumental music.

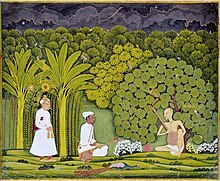

The aesthetic form of expression of kirtan is anchored in Vedic literature. In the Upanishads, the impersonal divine principle of brahman is described as being rasa . Rasa is an aesthetic term that is central to the performing arts in India and means a basic mood of inner fulfillment. The Vedic forms of dance, theater and music were closely related to the religious sphere because they pursued the goal of generating rasa . Apparently the Vedic singers were aware of the magical power of their music, with which they invoked the gods to participate in the rituals and praised them. The goddess Sarasvati is the patroness of music, which is usually shown with a vina in hand and Krishna plays the flute. Other gods are also said to enjoy music, which is why they are surrounded by Gandharvas , heavenly beings making music. The Gandharvas singing under the direction of the sage Narada are accompanied in their Gandharvasangita ("heavenly music") by dancing apsaras and music- making kinnaras . The Ghandarva music directed at the gods included not only dance but also dramatic productions. According to the ancient Indian music theory Natyashastra , which emerged around the turn of the century , special ritual songs ( dhruva ) were not only used in the literary language Sanskrit , but also in the Prakrit languages spoken by society at large in everyday life . The dhruva were the forerunners of later Hindu temple music and the medieval pada kirtan (narrative devotional songs).

The hymns and incantations handed down in the Vedas were and are reserved for the Brahmins who function as ritual priests in the Hindu temples. In contrast, religious singing styles such as kirtan, bhajan and the Bauls' own singing tradition in Bengal are also cultivated by members of other castes, religions and population groups. As accompanying instruments in Hindu temple ceremonies ( puja ), which took place around the middle of the 1st millennium BC. Originated in BC, handbells (Sanskrit ghanta ), snail horns ( sankha ), cymbals ( jhanjh, elathalam ), drums and, in southern India, double-reed instruments (such as the nadaswaram ) are used.

The basic ancient Indian texts for the kirtan and bhajan songs referred to by the Vishnuit Bhakti movement are the Bhagavad Gita and the Bhagavatapurana . In Bhagavadgita , chapter 9, verses 13-14, the terms kirtan (as kirtayanto ) and bhajan ( bhajanti ) stand for a devotion ( bhaktiya ) to the divine which is not necessarily connected with music. According to Tamil literature, the bhakti movement originated in southern India after the 6th century and soon spread throughout northern India in sect-like cults that worshiped Vishnu , Shiva or the female aspect of Shakti . In the Bhakti movement, individual worship took precedence over the temple rituals directed by priests. Since the Middle Ages, new forms of religious music have essentially emerged from the bhakti movement. The Hindu religious Vallabha (Vallabhacarya, 1479–1531) in western northern India and Chaitanya (1486–1533) in Bengal gathered a large following . A special form of kirtan , the choir singing and dances of which sometimes take on ecstatic character, is sankirtana in Bengal, which developed under the Hindu mystic Chaitanya and belongs to Radha Krishna worship. Besides Krishna, the most popular god in the Bhakti cult, other avatars of Vishnu, among them Rama, are worshiped in Vishnuism . Other devotional music is aimed at Shiva, Ganesha and the goddesses Durga and Sarasvati .

In the Bhagavatapurana of the 6th to 9th centuries, kirtan and bhajan are established as an integral part of the Bhakti cult. The bhakti therefore includes nine actions, of which kirtan is listed in second place. Furthermore, it is about offerings, worship ( puja ) and submission to the will of God. The music designated as gayan ("sing") and gita ("song") is expressly part of the worship . In another verse of the Bhagavatapurana (11/11/36) gita (“song”), tandava (“dance”) and vaditra (“instrumental music”) are named as equal components of the temple service.

According to the Bhagavatapurana , there were social bhakti movements directed against the strictly hierarchical social order, at the head of which was the Brahmanic orthodoxy, which in the religious cults used languages spoken in everyday life instead of Sanskrit. Accordingly, one of the usual principles of kirtan singing groups to this day is not to pay attention to gender and caste when composing.

The category pair great tradition versus little tradition of the ethnologist Robert Redfield was applied to the distinction between brahmanic tradition and bhakti movement . This concept explains the Brahmanic cults ( great tradition ) as an urban phenomenon of the elites, whose status the rural majority ( little tradition ) tries to achieve in a process called "Sanskritisierung" by adopting corresponding cult practices. On a musical level, the great tradition in India corresponds to the term shastriya sangit , the “ classical music ”, the melody of which is based on a raga , while the little tradition is assigned to the area of lok sangit , “folk music”, including kirtan . Even if a kirtan melody does not consistently follow a certain raga, some musical structures such as an increasing tempo and regular repetitions of melodic phrases are recognizable as adoptions of classical music.

The devotional chant originates from ancient Indian times, but only the kirtan chant , which was widespread with the bhakti movement and with several participants, facilitated religious worship by the general population. For kirtan singing, there is no need for initiation by a religious master ( guru ), no other rituals and no ascetic way of life.

Kirtan and bhajan

Accompanying instruments for kirtan and bhajan are hand cymbals ( jhanjh ), rattles ( kartal ), various drums ( tabla , pakhawaj , dholak in the north and khol in the east). Common melody instruments in northern India such as sarangi and esraj are increasingly being replaced by a portable harmonium , which was introduced by Christian missionaries in the 19th century and which takes on the function of a drone instrument instead of the tanpura . In South India the shrutibox takes care of the drone .

Kirtan and bhajan are similar in their ritual function to the psalms (from the Greek psalmos , “string play”, “price song”) in the Christian liturgy and the Dhikr of the Sufis. In the Indian tradition there is a functional connection to the Sanskrit hymns ( stotra and sutka ) of the Vedic period to a deity, but the devotional forms of music kirtan and bhajan emerged independently of the Vedic tradition together with the medieval bhakti movement.

The word kirtan is derived from the Sanskrit root kirt- , which means “to glorify”, “to praise”. In medieval Sanskrit literature , kirtan means "song of praise to a god". In addition to music, dance and abhinaya (the physical means of expression in a dramatic staging) form the artistic forms of representation of the temple cult. These are based on the principles of anukaran (imitation) and anukirtan (glorifying narrative). A precentor in kirtan is a kirtankar and someone who recites religious texts from Hindu tradition ( katha ) is a kathakar ("maker of katha "). In over India popular kirtan traditions almost anywhere women assume the role of lead singer, but they are among the members in some ensembles and act regionally, such as when naradiya kirtan of Maharashtra as kirtankar .

Like bhakti, Bhajan goes back to the Sanskrit root bhaj- (“to share”, “to participate in [a ritual]”). The word Bhagavan is also derived from bhaj- , which means “exalted”, “Lord” who has bhaga (“happiness”, “abundance”). Thus kirtan and bhajan are connected with the worship and praise of God (Bhagavan) in the Bhakti movement. Even if both terms are often used indiscriminately, kirtan usually means a singing style of several singers in praise of God and bhajan a song with a more personal, soloist address to the divine. Nam kirtan and nam bhajan equally denote the chanting of God's names; if this ritual is performed as a personal devotional act with the help of a prayer chain, it is called japamala . Japamala can be performed according to the ancient Indian form of the mantra as a chant with one or two pitches or as a barely audible murmur.

With kirtan and bhajan , pada kirtan , songs with narrative content ( pada , "words", "lyrics") are meant in most cases ; the expression pada bhajan is less common. Pada kirtan lyrics are heavily influenced by one of the most important Sanskrit poems in devotional literature, the Gitagovinda by the Bengali author Jayadeva from the 12th century. In Gitagovinda , a verse form consisting of a refrain ( dhruva ) and eight stanzas ( pada or carana ) is introduced, which since then has been the basis of kirtan and bhajan as a fixed structure . In devotional folk poetry, this or a modified form of verse addresses Vishnu and his incarnations Rada and Krishna as well as a large number of other gods.

In southern India, kirtan was mainly written by the followers of the Haridasa movement founded by Naraharitirtha in the early 14th century. Among them was Sripadaraja that of the 15th century Hari directed kirtan on Kannada wrote. Other South Indian kirtan poets were Annamacharya, who worshiped the god Venkateswara (a form of Vishnu) on Telugu , and Tyagaraja (1767–1847), an important composer of classical South Indian music, who directed his kirtan to Rama. In northern India in the 16th century, the poets Surdas, Swami Haridas, Nandadas and Paramanandadas wrote kirtan addressed to Krishna in the vernacular Braj-Bhakha . Krishna also worshiped Namdev (late 13th to mid 14th century) and Tukaram (17th century) in poems written in Marathi . Tulsidas (around 1532–1623) worshiped Rama in the north Indian vernacular Awadhi in the 16th century . The Bengali poet Govindadasa wrote kirtan for Krishna in the Bengali- related literary language Brajabuli and Chandidas and worshiped Radha and Krisha in poems in Bengali in the 15th century. In northern India, pada kirtan and bhajan were performed in the style of the strictly defined classical music genres dhrupad and dhamar (a rhythmically more pronounced form of dhrupad in a tala with 14 beats ), and also performed in the rhythm of cautal (12 beats ).

Haveli sangit is a singing tradition of the Vallabha movement ( Vallabha Sampradaya ) founded by the religious scholar Vallabha at the beginning of the 16th century . The name haveli for the houses of wealthy traders, especially in Rajasthan and Gujarat, refers to the corresponding patronage of this music for the worship of Krishna. Haveli can denote a palatial house or a temple of Krishna. The Vallabhas, who also included the blind singer and musician Surdas, called their dhrupad- style songs kirtan . The kirtan ascribed to Surdas are gathered in the Sursagar collection ( Sursagar , "sea of sur ", with the Sanskrit root sur , "rule", "shine", derived from Surya , "sun"), which is traditionally divided into twelve sections to form to correspond to the Bhagavatapurana as the most important Sanskrit text for Krishna worship. Surdas belongs to a group of eight poets of the Vallabha sect who are called astachap ("eight seals"). These eight poets (namely Surdas, Paramananddas, Nanddas, Krishnadas, Govindsvamīi Kumbhandas, Chīiasvamī and Caturbhujdas) wrote thousands of pada kirtan , which is why they went down in Indian musical history as pioneers of the classical dhrupad and dhamar songs.

Kirtankar ("one who performs kirtan ") are recognized and educated cantors who are almost always Brahmins . In general, a kirtankar has a more thorough musical training than a bhajan player ( bhajanik ). In addition to devotional songs, the repertoire of a kirtankar often includes classical dhrupad compositions and some entertainment genres such as wedding songs ( Gujarati lagna gita ), lullabies ( haladu ) and seasonal songs ( ritugit, ritu gita ). The status of kirtankar is inherited and bestowed on those who fulfill corresponding obligations to a patron or a temple. The bhajanik , on the other hand, acquires its status through performance and may use it to hide its caste membership.

Katha

Katha (Sanskrit "story", "saga", "story") is a genre of prose stories mentioned in ancient Indian Sanskrit texts and denotes a form of narrative kavya literature, which is divided into katha (prose) and akhyayika (verse). Katha stands for a fictional story that, unlike akhyayika, is not necessarily written in Sanskrit and contains a story that is told not by the hero himself but by another person. In the Sanskrit dictionary Amarakosha from the 4th century BC The completely invented genus katha is distinguished from akhyayika with a certain historical basis. The katha genus includes the Sanskrit collection of fables Panchatantra and the epic Brihatkatha ("great story") written by Gunadhya in Prakrit in the 6th century . The Hindi word katha for fictional prose is taken from Sanskrit .

In addition, katha has stood for a narrative tradition of texts from ancient Indian religious literature since the Middle Ages. The katha genre was recited at rulers, village assemblies, temples and Sufi gatherings . In the 15th and 16th centuries, the katha texts were mainly written in verse and recited aloud. They have been copied many times as elaborate manuscripts and translated into several North Indian languages. The stories of this time - like the Ramcharitmanas , which Tulsidas wrote at the end of the 16th century - are based on the ancient Indian epics and Puranas or at least refer to them, even if they have completely different contents.

Katha kirtan , the narrative song, is the lecture of a single actor ( kathakar ) who appears as a solo entertainer with songs, spoken explanations and acting activities in front of an audience. This has been a popular form of entertainment for men and women of all castes in cities and in the country since at least the 18th century. Regionally, katha kirtan occurs in variants with different names: Hari katha ( Hari as an epithet for Vishnu) in Karnataka and Maharashtra, Shiv katha (addressed to Shiva ), kathakalakshepam in Tamil Nadu , kathaprasangam in Kerala and burra katha in Andhra Pradesh . Other names in other regions are Bhagavad katha, pravachan ( pravacana ) and pandvani . Other genres of performing arts with narrative and satirical elements include the folk dance theaters tamasha in Maharashtra, thullal in Kerala, swang in northwest India, bhavai in Gujarat and jatra in West Bengal.

According to general opinion, the nam kirtan , in which the name of God is proclaimed, is the forerunner of the narrative katha kirtan . The storytellers kathakar of the Middle Ages combined the ancient Indian religious tales with songs and subplots to create their own performance practice. The solo entertainers at the court of Thanjavur in Tamil Nadu, who had been fetched from Maharashtra, sang in their language Marathi , which was enriched with Sanskrit quotes from ancient Indian literature. Later on, katha kirtan were performed in numerous Indo-Aryan and Dravidian languages. The kathakar should be well versed in ancient Indian literature, have a musical training and a pleasant voice. The demands of classical aesthetics ( rasa ) that are placed on its performance include the ability to express emotional moods such as raudra (anger), bhibhatsa (disgust), hasya (humor), karuna (compassion), bhayanaka (fear) and sringara ( Love).

Bengal

Padavali kirtan

The oldest traditional genre of song in the northeast Indian region of Bengal is charya giti , whose heyday was in the 9th to 12th centuries. The religious poems are gathered in the Charyapada and written in the Middle Indian language Abahattha even before the Bengali language was developed. The poets and singers of charya giti came from a group of Buddhist mystical saints. Musically, the songs were based on the then popular classical style charya , which the Vishnuit poet Jayadeva adopted for a new genre in the mid-12th century . With this he inspired the worship of Radha-Krishna in Bengal and founded the Vishnuit devotional musical tradition of Bengal. Jayadeva, the court poet of the Bengali king Lakshmana Sena, who was crowned around 1178, titled his collection of songs written in Sanskrit Gitagovinda ("Songs to Govinda", an epithet of Krishna). The musical form is a forerunner of the later dhrupad . The Gitagovinda-padagana (Sanskrit padagana , "recitation of the Vedas") is considered to be the origin of the Bengali padavali kirtan . Padavali kirtan has also been compared to the genre rupak prabandha , which is treated in the 13th century music theory Sangita Ratnakara , written by Sarngadeva . Prabhandas have been known in Bengal since the time of the music scholar Matanga (probably 8th century).

In the second half of the 15th century, the songbook Sri Krishna Kirtan by the poet Chandidas, written in Bengali, added to the devotional songs of the Bengali Vishnuits. In addition to the classical music style of the Buddhist charya giti des Gitagovinda , Chandidas adopted elements from the religious music of the Baul , the panchali stories and Bengali folk music. This resulted in the Bengali devotional genus of padavali kirtan , which was soon spread by hundreds of poets and singers called mahajana ("saints") in Bengal. From her poems and songs, known as mahajana padavali (“songs of saints”), an important Vishnuit musical tradition developed in Bengal in the second half of the 17th century.

Nityananda Thakur was the closest companion to Chaitanya in the 16th century. The Birbhum district where he was born is known for kirtan and the music of the Baul. Unlike the ascetic Chaitanya, Nityananda stayed with members of the lower castes ( Shudras ) and with untouchables . Even if Chaitanya is considered the father of kirtan in Bengal , it was above all Nityananda's merit that he spread his verses and the teaching of Gaudiya Vaishnava through his missionary work .

The padavali kirtan (also pada , "verse", kirtan ) is considered the most cultivated genre of religious music in Bengal. Narottama Das (1531–1587), a student of the mystic Chaitanya, who organized a large kirtan festival ( mela ) in Kheturi (a village in today's Rajshahi district in Bangladesh) in the 1570s, contributed significantly to its current form . At the inauguration of the gods in the Radha Krishna temple there, Narottama Das demonstrated his kirtan style, which has since been known under the name padavali kirtan or occasionally - named after the region around Kheturi - as garanhati kirtan . Narottama succeeded in uniting different groups within the Bengali Vaishnavas with his kirtan style, which, like the dhrupad, is a slow and very ornamental musical form. The musical tradition introduced by Narottama was later given the name Garanhati gharana . The Kheturi Festival takes place every year to this day.

Narottama's Garanhati gharana was later joined by kirtan styles, which were influenced by influences from other classical singing styles such as khyal , thumri and tappa . The verses of padavali kirtan deal with the mythical tales of Radha-Krishna, as they are also the basis of the dance theater Ras lila , and are written in Bengali or in Brajabuli. The latter is an artificial language introduced by Vidyapati (1352–1448) for his poetry, which combines Bengali and Maithili . The narrative thread is interrupted by a few improvised insertions ( akhtar ) in everyday language to give the audience explanations for better understanding. The music is largely passed on orally, and there is also its own notation system ( ba ).

The text presentation follows five aspects named anga : katha, doha (stanza), tuka (decorative part), chhuta (part of a stanza) and ankhara . While kirtan stands for the entire musical form, katha is the narrative song text that relates to conversations, especially the exchange of question and answer between Radha and Krishna. Ankhara is a freely complemented musical embellishment of the singer, comparable to the ornamentation of the melody ( tan, taan, tana ) of classical North Indian chant. Each padavali kirtan is assigned a specific raga, which is common or older. Characteristic are long tala (rhythmic cycles with many beats ), which are performed at a slow pace ( vilambit laya ) in order to increase the meditative atmosphere . The padavali kirtan music ensemble includes one or more singers who are accompanied by a double-headed clay drum ( khol ), hand cymbals ( kartal ), and occasionally a violin and a bamboo flute. There are some well-known male and female singers who perform padavali kirtan .

At the social level, padavali kirtan is assigned two specific characteristics: belonging to an egalitarian social structure and a role in the education of a classical Sanskrit aesthetic. The anti-colonial journalist Sisir Kumar Gosh (1840–1911), a Vishnu follower in Kolkata , was probably the first to write about the social class and anti-authoritarian nature of padavali kirtan and emphasized the religious element in the anti-colonial Bengali national movement . The importance of padavali-kirtan for the upper class ( bhadralok ) of that time speaks for its educational role. The song repertoire mainly includes compositions by Vishnu followers from the 16th century, which are based on the aesthetic theories of Sanskrit literature.

Marai kirtan

In addition to the kirtan in verse, padavali kirtan , the form of storytelling, katha kirtan , and marai kirtan are common in Bengal . The latter is cultivated in rural areas in the west of the Indian state of West Bengal , especially in the Purulia district , in the village temples. Marai means "circular" and in the original meaning "to grind" and "to squeeze out". The regional expression marai kirtan corresponds to the general nam (a) kirtan , in which only one name of God is invoked. In the Dirstrict Purulia the believers only repeat the words Hari Bolo ( Hari means Krishna and bolo, bol , means “to sing the name”). In addition to religious worship, the performances also serve other purposes, for example to solicit rain or happiness for the community from the gods. Marai kirtan is considered to be a folk music parallel development to the classical music of pada kirtan , whereby the essential compositions do not come from the North Indian classical music with its fixed ragas , but are based on regional desi raga ("village ragas"). In padavali kirtan and katha kirtan , music and singing are in the foreground, while dances are of little importance. In contrast, the dance leading to ecstasy forms an essential part of a marai kirtan performance, which can last for several hours without a break . Thus, both meanings of the name marai (“endlessly turning in a circle” and “squeezing out” as “merging with the divine”) contain the essential aspects of the performance. In addition to kirtan performances, Purulia is known for a regional style of dance theater chhau and as a meeting place for Baul singers. The music of the mystical group of the Bauls has an essential part in the emotional character of the marai kirtan . The devotional style of music dapha in the Kathmandu valley reaches a comparable intensity , in which a group of singers accompany each other on barrel drums ( lalakhin ) and cymbals ( tah ).

The instrumental accompaniment of the voices ( mul gayak ) and dances in marai kirtan traditionally consists of the double cone drum khol and the cymbal pair kartal from East India to Bangladesh . In addition, a clarinet , a keyboard or a harmonium , which was introduced during the British colonial era, is often used today , following the melody line sung in parallel. Traditional instruments of the Bauls are the plucked drum ektara , which can be used to rhythmically support the khol , and the two-string plucked long-necked lute dotara .

The main instrument is still the clay drum khol , which has been used for marai kirtan since Chaitanya in the 16th century . Its components and use are based on religious symbols. The black voice paste ( gab ) on the eardrums is associated with the eyes of the Radha. Radha sheds tears because she is separated from her beloved Krishna. The deep fur represents Radha, the high fur Krishna. The symbolism extends to the strips of skin with which both skins are tied and which are presented as Gopis (cowherdesses). The khol are only allowed to make members of the lowest professional caste of shoemakers (Muchi, Mochi) belonging to the Dalit , because the drum has to be held with the feet during production and nobody else is allowed to touch it with their (unclean) feet. As a sign of respect, the khol with honorary titles as shri khol named.

The instrumentalists at kirtan can belong to any caste, many come from one of the professional musicians caste with the lowest social status who live in this region in West Bengal and are classified as Scheduled Castes . The best-known professional musician caste, the Doms, perform with their large kettle drums dhamsa , barrel drums dhol and reed instruments shehnai at all social and religious ceremonies including the dance theater cchau and marai kirtan .

The religious meaning of the marai kirtan is described in terms from the tantra . These include shravana (hearing the teaching or hearing and calling out the name of the deity), manana (intellectual reflection, remembering God), reciting a mantra with the name of God (here Hari nam ) and sadhana (spiritual practice, path to success). With these exercises practiced in marai kirtan , the participants should reach the stage of samadhi (state of consciousness of immersion in the divine). The intensity of singing, music and dance achieve an ecstatic character that is carried over to the audience. However, this does not mean that the participants lose control, who always adhere to the strict rhythmic structure of the music and the dance choreography.

Braj

Braj is a region south of New Delhi in the state of Uttar Pradesh , which includes the cities of Vrindavan and Mathura, which are important for Hindu pilgrims . In Braj, according to the legend, Krishna was born and here he spent his youth, which is why, besides Bengal, several Vishnuitic teaching traditions ( sampradaya ) for the worship of Krishna have their center in Braj. For numerous Bhakti groups, Braj is the starting point of North Indian religiosity. The Ramanandi Sampradaya , a Vishnuit group in Ayodhya , sing about Rama in various bhajan . In the southeastern city of Varanasi on the Ganges , Shiva is worshiped with devotional songs .

The mythical scenes of the youthful Krishna, his lover Radha and the Gopis take place on idyllic lakes in the forests of Braj. These bodies of water are ponds with natural banks or masonry pools, which are called Kund in Hindi . There are temples on their banks , often in the middle of settlements, where they form the ideal public open space for gatherings, festivals and performances of kirtan .

Pada kirtan

Pada kirtan is usually performed by a small group who sit on the floor and form a tight circle with the cantor. The pada kirtan , mainly coined by the Gitagovinda of Jayadeva from the 12th century, consists of eight stanzas ( pada or carana ) and a refrain ( dhruva , literally "fixed", "immobile"). The lead singer and choir alternate between singing a verse and the chorus, both of which lead to an ending rhyme. The texts are structured in such a way that the chorus forms a logical conclusion to each stanza.

Samaj gayan

A lesser-known form of north Indian pada kirtan , which in three Vishnuit traditions only occurs in the Braj region, is samaj gayan . The singers-choir alternating chants of samaj gayan include their own melodies, which are less strictly based on the classic ragas and talas. The style name kirtan is not used by the singers themselves, although the characteristic features of pada kirtan apply. The demanding samaj gayan , which requires a long period of practice, is cultivated by the Nimbarka Sampradaya , the Haridasi Sampradaya and the Radhavallabha Sampradaya , all of which are at home around Vrindavan and belong to the Radha Krishna cult usual in Braj. The samaj gayan ensembles act cantor ( mukhiya ) and accompanying singers ( jhela ) over other kirtan groups musically more as equal partners. Solo singing is not common because, according to the singers, the stories of Radha and Krishna can only be made clear by acting together. A cantor and at least two singers are required, who answer each individual verse of the cantor in a fixed way with a refrain. The cantor begins with a verse, after which the choir singers repeat the verse verbatim after a suitable exclamation. At the end of the verse, the chorus is performed by all singers at a faster pace, which can take over an hour depending on the length of the song. The accompanying instruments are the double-cone drum pakhawaj , which is sometimes replaced by the kettle drum pair of tabla , hand cymbals ( kartal or jhanjh ) and harmonium, occasionally supplemented by the plucking tanpura , which produces a drone sound , and the stringed lute sarangi or esraj .

The Nimbarka Sampradaya traces its tradition Nimbarkacharya in the 12th century and continue on a mythical origins date back, after which Krishna Himself in heaven the sage Narada the samaj gayan taught. Sri Bhatta, the poet of Yugalasataka, belongs to this tradition in the 16th century . This is a collection of 100 verses, first written in Braj-Bhakha , describing the pleasures of the young couple Radha and Krishna and which became the model for Krishna poetry in that language. Sri Bhatta's disciple was Sri Harivya's Devacharya (1550-1630), who wrote the most important song collection of the Nimbarka sect, Mahavani . It contains songs for 20 religious festivals throughout the year. These include Holi in spring, Diwali in autumn, and the birthdays of their acharyas (religious leaders). Otherwise samaj gayan are not listed as a daily ritual.

The Haridasi Sampradaya was founded by Swami Haridas (16th to the beginning of the 17th century) who, according to tradition, was the teacher of the court singer Mian Tansen (around 1506–1589) and thus stands at the beginning of classical Hindustan music. Swami Haridas wrote the Kelimata song collection , ( dhrupad compositions with 110 short verses) he was a solo dhrupad singer and musician, but did not practice samaj gayan choir singing . This was only adopted by his followers in the early 19th century. The Haridasi strictly adhere to a fixed assignment of pada kirtan for the respective day of the Hindu calendar including the birthdays of the Acharyas and other religious holidays. On these festive days, a special form of samaj gayan is practiced with an alternating chant between the groups lead singer ( mukhiya ) and answer choir ( jhela ),

The Radhavallabha Sampradaya was founded by Sri Hit Harivansh (1502–1552) and has been practicing samaj gayan since then, according to its followers . The main work of the founder, Hitacaurasi (also Caurasi pada ), written in Braj-Bhakha , consists of 84 verses for different ragas. This Vishnuit group, little known outside the Braj region, worships Radha more than Krishna. Its members claim to have performed samaj gayan longer than any other group. Radhavallabhaji ka Varsotsava , written by several authors (known as samaji ), is the most extensive pada kirtan song collection. The songs are ragas in the classic dhrupad style or slow pieces in the dhamar style.

Haveli sangit

Better known than samaj gayan is the Krishna lyric haveli sangit , based on dhrupad and dhamar compositions , which was written in Braj at the beginning of the 16th century. Haveli sangit , in the tradition of the Vallabha Sampradaya and especially associated with the traders' houses in Rajasthan, was called kirtan at the time of the Surda in the 16th century . Surdas and the other of the "eight poets" ( astachap ) founded the Vallabha Sampradaya , in which the worship of Krishna in the form of Srinathji (also Shri Nathaji, "the holy lord") is the focus. The image of the god was brought to Rajasthan in 1672 to protect it from Muslims. Today the image of Srinathji is venerated in the pilgrimage center and main temple of this group in Nathdwara in Rajasthan (northeast of Udaipur ). This includes a daily sequence ( nitya kirtan ), which consists of eight, three-hour sections ( prahara ) from morning to evening , during which kirtan is sung in ragas that match the time of day. In addition to Braj and Nathdwara in Rajasthan, haveli sangit is also performed in Gujarat and Maharashtra .

Only traditional ragas and talas are used in haveli sangit . The seven main talas used are cautal (12 matra , counting times), dhamar (14 matra ), ada cautal (14 matra ), tintal or adi tal (16 matra ), jhaptal (10 matra ), sultal (10 matra ) and jhumra ( 14 matra ). Ragas also used in North Indian classical music include sarang, kedar and malkauns .

Gujarat

Haveli sangit

For the Vallabha Vishnuits, haveli sangit is the main form of kirtan . The chant serves to worship Krishna in his haveli (Krishna's home in a stately home or temple). There a Brahmin priest ( pujari , from puja ) offers food and clothing directly in front of the statue of Krishna, which is located in a partitioned off area of the temple. If a kirtan group is present, the kirtankar leads the worship ritual . Here the priest takes the screen aside and the image of Krishna shows itself to the believers. The lead singer and his companions guide the believers who participate in the kirtan singing. The musicians play the double-headed drum pakhawaj or, in some newer pieces, the kettle drum pair tabla . A tanpura or a shrutibox (also surpeti ), a harmonium, jhanjh (flat hand cymbals), manjira (cup-shaped cymbals), sarangi (bowed lute) and bansuri (bamboo flute) are also used as drone instruments .

The believers are either placed opposite each other according to sex, with the men on the right of the Krishna figure and the women on the left or, if they all form a circle, then the men sit in the front rows and the women behind them. The believers take over the chorus after each verse of the lead singer in the alternate song. The verses often come from the Gitagovinda .

Akhyan

Another genre of devotional songs in Gujarat is akhyan , a legend or poetic tale from the Puranas . Akhyan belongs to the classical Gujarati literature, which was written exclusively for musical performance from the mid-15th to the mid-19th century. The narrative ( pada ) contained in an akhyan is divided into sections ( kadava ), each in a different tala and with a connecting refrain ( valana ) in between.

The best known form of akhyan is called bhatt (or gagaria bhat ). Gujarati gagar, gager, gagri means "water pot" and one stands for a large spherical metal vessel, both of which refer to their use as a rhythmic accompanying instrument for the storyteller (cf. ghumat made of clay, mizhavu made of copper). Bhatt is a common proper name of Brahmins in Gujarat, which means "educated person". According to a centuries-old tradition, the man bhatt akhyan is a single male storyteller ( man bhatt ) who accompanies himself on a metal pot. He tells stories from the great Indian epics Mahabharata and Ramayana , from the Puranas and from everyday life. The clients for appearances in a temple or in the courtyard of a private house are cartridges from the middle class, otherwise he finds his audience in public places. The narrator claps his finger rings flat on one hand on the top of a pot with a diameter of around 60 centimeters, producing short, metallic-sounding blows. Accompanying musicians also use the ion instruments common to haveli sangit . The narrator pauses between the verses and adds explanations by showing parallels between the ancient Indian stories and everyday life today. With inserted songs from all areas, he occasionally loosens the narrative thread.

Maharashtra

Naradiya kirtan

In Maharashtra , the kirtan goes back to the Marathan saint Dnyaneshwar in the 13th century. Since then there has been a kirtan tradition in Maharashtra , which consists of sung verses in connection with recited stories and conveys philosophical theses that are packaged in ancient Indian epics and life stories of saints. The naradiya kirtan according to legend, to the mythical sage Narada is returned, stylistically he was influenced by Marathi poet Namdev. The variant rashtriya kirtan in Maharashtra is a religious and political music genre in the Marathi language , which is hardly known outside of this state. Formally, the rashtriya kirtan belongs to the genus naradiya kirtan . The other of the two kirtan genera in Maharashtra's Warkari kirtan .

A naradiya kirtan begins with the praise ( naman ) of the kirtankar first to the temple deity, then to Sarasvati and Ganesha , to the patron deity ( kuladevata ) of his own family and finally to his guru, sometimes also to a portrait of Narada. The audience sits opposite each other, separated by sex. After the ceremonial prelude purvaranga , which is generally used in Indian theater , which includes a kirtan with instrumental accompaniment addressed to a famous singer like Narada, a detailed explanation ( nirupan ) and classification of the song in religious poetry follows . The kirtankar often quotes from Sanskrit sources . In the following songs the audience joins the singing. This is followed by the second part ( uttararanga ) with a long narration ( katha ), in which the ethical and moral issues mentioned earlier are dealt with . In this part, also called akhyan , the kirtankar tells well-known stories, and the emphatic nature of his presentation decides whether he succeeds in delighting his audience. Finally, he once again thanks the gods and has a donation vessel passed around.

In the political variant rashtriya kirtan , the kirtankar also mainly performs devotional songs and also tries to convince his audience of a Hindu nationalist course directed against the secular state model in favor of certain political parties . This religious-nationalist tendency has dominated Indian politics since 1998, when a coalition led by the BJP came to power. In Maharashtra, the Brahmins have always been at the forefront of the nationalist movement; the Hindu-extremist organization RSS was controlled by Brahmins in Maharashtra and formed a closed social group after Gandhi's murder in 1948 by a Brahmin from Maharashtra.

The religious reference makes the medium kirtan suitable for nationalist propaganda among Hindu listeners. On the ritual occasion of a naradiya kirtan , the kirtankar , who always belongs to the brahmin, stands facing the god statue in the temple in front of the sexually separated listeners. According to an estimate from 2002, the proportion of women among the kirtankar is around 40 percent. The accompanying musicians play tabla and harmonium, the kirtankar himself beats the hand cymbals jhanjh . He sings mostly as a soloist, the choir only comes into action at the beginning, during breaks and at the end.

The rashtriya kirtan emerged at the beginning of the 20th century when kirtan singers began to travel through the villages of Maharashtra for the nationalist, anti-colonial liberation struggle. Today's nationalist kirtankar take different positions, some want to preserve traditional Brahmin values and warn against Western cultural influences, while others direct their agitation against Muslims and support India's military actions in the Kashmir conflict against Pakistan. There are also other rashtriya kirtankar that address social problems such as alcoholism, environmental protection or corruption. The musical form in which they convey these messages largely corresponds to that of the religious, apolitical naradiya kirtan . Both times the verses of a holy poet are the starting point, with a rashtriya kirtankar representing nationalistic activities as religious merits. One difference is the Marathi song genre powada , which is integrated in rashtriya kirtan and missing in the rest of naradiya kirtan , which represents a historical narrative tradition that emerged at the end of the 17th century.

Warkari kirtan

The warkari kirtan belongs to the ritual program of the Vishnuit Warkari Sampradaya , whose believers worship the god Vithoba (also Vittala, a manifestation of Vishnu in Maharashtra) in the main temple of the city of Pandharpur . The kirtankar in the warkari kirtan , who is almost always a man, stands at some distance in front of the figure of Vithoba, while the audience, separated by sex, sit on the floor between him and the figure of the god. He is accompanied by a 10 to 50-member choir set up in a semicircle behind him. A musician plays a two-headed drum mridang and the kirtankar or alternately a member of the choir produces a drone tone with a long-necked lute ektari . The choristers are talkari called because they way the Handzimbeln tal beat.

The songs are composed of depend (a) in a certain meter of a Marathi poet who is revered as sacred and a bhajan . Abhanga is a devotional form of poetry addressed to Vithoba, and bhajan here means single-line songs in praise of God. The choir and kirtankar often interrupt each other and continue the song performance . The listeners know most of the melodies and often join the choir singing.

South india

Marathi kirtan

The Smarta tradition ( Smarta Sampradaya ) is a mainstream orthodox Hinduism in which the five gods of the Indian pantheon are worshiped according to a ritual practice called panchayatana puja and which mainly adhere to Brahmins. The Smarta Brahmins in Tamil Nadu have adopted the Marathi tradition of kirtan and try to distinguish themselves as a link to non-Tamil traditions and to strengthen the influential Brahmanic cultural tradition of their state. Ultimately, the Tamil Brahmins claim a role as custodians of the all-Indian Bhakti movement. As the father figure for their devotional music ( bhajana sampradaya ) they often name Sadguru Swami (1777-1817) from the village of Marudanallur ( Taluk Kumbakonam ).

The modern cultural influence of Maharashtra in Tamil Nadu dates back to the 17th century, when a half-brother of the famous Marathas -Anführers Shivaji 1674 Thanjavur conquered and the Marathas Dynasty local justified. Samarth Ramdas (1608–1681), a religious adviser to Shivaji, is said to have visited Thanjavur himself. What is certain is that one of his students founded a building dedicated to Samarth Ramdas in Thanjavur in 1677/78 for the performance of devotional music and that later other such buildings ( bhajana matha ) were set up. In these bhajana matha songs composed by Ramdas were sung.

In the 18th century, the North Indian classical music styles dhrupad , khyal and tappa were cultivated in Thanjavur, as was the Marathi-language music and dance style lavani from Maharashtra. It is from there that Vithoba is worshiped by the Warkari sect, which was a popular religious practice in Thanjavur in the 18th and 19th centuries. During this time, the Marathi poet Namdev, Bhanudas (1448-1513) and Tukaram were performed in Thanjavur and the surrounding delta of the Kaveri warkari kirtan . Via this region, warkari kirtan reached the south to the princely state of Travancore on the south-western tip of India.

In the bhajan matha (or Ramdasi matha ) of Thanjavur is in addition to the Warkari kirtan and Ramdasi kirtan , a third Marathi kirtan maintained that after month, Dhanu (also dhanurmas / January December) of the Malayalam calendar dhanurmas kirtan calls. This Marathi style of kirtan is part of special temple rituals and processions that take place in Thanjavur in the month of dhanu .

Around the middle of the 19th century, the Marathikirtankar Ramchandra Bava (1812–1881) was one of the first to perform the Marathi-speaking kirtan in Thanjavur outside of a matha in temples or palaces. Ramchandra's ensemble also included a Muslim musician who played the drum dholak . There was also the North Indian string instrument sarinda . This kirtan tradition was continued by a few Marathas, revived at the beginning of the 20th century by Tamil Brahmins and is now considered one of their forms of classical South Indian music for some of the Tamil Brahmins.

Kirtana

From the 14th century, under Persian influence, classical music in northern India gradually began to separate from the ancient Indian tradition, so that two different lines of tradition emerged with Hindustan music in the north and Carnatic music in the south. Nevertheless, there are numerous stylistic similarities between the vowel styles dhrupad in the north and kirtana (m) in the south.

A starting point for rhythmic structures and rhyme forms of the kirtana songs is the Gitagovinda from the 12th century. This is the origin of the basic structure of kirtana with verses ( carana ), stanzas made up of eight verses ( astapadi ) and a refrain ( druva ), which was further developed in Karnataka in the 14th century by members of the Haridasa movement. Vishnuit singers practiced the tradition of Gitagovinda daily in the Jagannath Temple of Puri over the centuries . Singers belonging to the Haridasa movement who performed kirtana in their regional language, Kannada , were Narahari Tirtha (14th century) and Sripadaraya (1422-1480). According to the structure, kirtana refers to a song composition of up to ten verses ( caranam ) with one line as the refrain ( pallavi ) and, based on the performance practice, as in the north, a devotional song divided between the lead singer and the choir. The 16th century was the heyday for the development of kannada-speaking kirtana of the Haridasa movement.

In Andhra Pradesh , Tallapaka Annamacharya (1424–1503), cantor at the particularly holy Venkateswara temple near Tirupati , wrote thousands of kirtana songs in Telugu . The same is narrated from Purandara Dasa (1485–1565), who wrote on Kannada and, according to legend, sang songs in his youth with the older Annamacharya. Both are considered to be Hindu people.

The Telugu poetry of kirtana was continued by the descendants of Annamacharya, his son Pedda Tirumalayyangar and his grandson Tallapakam Chinnayya and is performed by singers to this day. The three Tallapaka composers expanded the kirtana, consisting of the two alternating segments pallavi and caranam , to a three-part form of pallavi, anupallavi (Sanskrit anu , "small") and caranam , which has been the standard ever since. The engraved texts and names of the ragas of around 20,000 songs have been handed down on 3,000 copper plates.

The three-part kirtana form, as padam, javali and pada varnam, also characterizes the pieces of music for religious dance theater such as Yakshagana , Bhagavata Mela and Kuchipudi . Other South Indian singing forms are kriti and varnam , which are essential components of classical music. In South India, Bhajan is a simpler and shorter form of devotional collective chant with less text than kirtan .

Shabad kirtan

Shabad kirtan , actually gurmat sangit (Sanskrit gur , " guru , teacher"; mat , "doctrine, principle of belief" and sangit , "song") is the devotional music of the Sikhs , which is based on classical ragas and talas, but according to their mood listened to light classical music ( bhav sangit ). The Punjabi word shabad is derived from Sanskrit shabda , "sound of language" with the meaning of "voice, language, murmur" and, in the context of Sikhism, denotes the tone of the words uttered by the guru as well as a hymn or a section in the sacred scriptures of the Sikhs, the Guru Granth Sahib . In the Golden Temple in Amritsar , the main shrine of the Sikhs, shabad kirtan are performed all day . In addition, shabad kirtan take place worldwide in all places where Sikhs meet for a religious gathering - in a gurdwara , temple or private house. Shabad kirtan were composed by Sikh gurus, Muslims or Hindus, they are considered to be the most effective ritual act for Sikhs to experience spiritual fulfillment and closeness to God.

Swami Haridas wrote numerous dhrupad compositions in the 16th century , which consist of the four parts sthai, antara, sanchari and abhogi and were adopted in this form by many later composers of the Bhakti movement. During this time formed in Kashmir a form of Sufi music , the out Sufiana kalam (or sufyana Musiqi ) is called. Sufiana qalam is the classical music of Kashmir, which is preferably promoted by the Muslim urban bourgeoisie and, as a cultural heritage of the region, also by educated Hindus and performed at a mehfil . A mehfil is either a religious meeting of Sufis with music or a secular evening of music lovers in a small group in a private house. Maqam form the melodic basis of sufiana kalam .

During the time of the ten Sikh gurus , who lived from 1469 to 1708, there was already the classic form prabandh ("fixed form"), a style of singing consisting of five elements, one of which is the basis for today's dhrupad . The prabandh also influenced the shabad kirtan . Guru Nanak and his nine successors contributed to the development of the singing style through the use of newly composed or adopted ragas and talas; he had his songs accompanied by a Muslim musician on the plucked rabab . After Guru Nanak several years had been on the go as a missionary, he settled in Kartarpur (District Narowal in Pakistan's Punjab ), where he founded the first center of the Sikhs and Sikhs (the liturgical chant gurmat sangit ) established as a ritual form. Certain kirtan songs were sung in the mornings and evenings , as is evident from the literature of Bhai Gurdas (1551–1636), the first writer of the Granth Sahib .

Each of the subsequent gurus composed hundreds of hymns with different ragas. The tenth and last Sikh guru, Gobind Singh (1666–1708), wrote hymns in 19 different ragas and also promoted other musicians and poets. In his time, the rather lyrical classical music style khyal began to develop compared to the strict older dhrupad . By the middle of the 18th century the khyal became the preferred classical vocal style and consequently influenced the shabad kirtan as well . As with classical music, the melodies of the shabad kirtan were only passed on orally in a teacher-student relationship ( guru-shishya parampara ) within a family tradition ( gharana ); their notation did not become the standard until the end of the 19th century. The division of the country after the independence of British India in 1948 brought radical changes for the kirtan ensembles. Until then, professional Muslim musicians accompanied the singing on the plucked long-necked lute rabāb , when they had to leave India for Pakistan in the course of the population exchange, many of the traditional compositions also disappeared. They were replaced by amateur singers ( raggi ), some of whom had little knowledge of classical ragas.

As in classical music ( shastrya sangit ), the ragas of shabad kirtan are associated with times of day, seasons and moods, and some are associated with historical events. For example, it is known that Guru Nanak composed numerous hymns in the morning raga Ramkali, which is also popular with the Shivaite sect of the Naths and their Siddhas , while the Raga Tilang is preferred by the Sufis and the associated hymns use the imagery of mystical Islam. The rhythms named after their meters ( tala, theka ) are taken from the classical styles dhrupad and khyal as well as the folk music ( deshi sangit ) of the Punjab. As in classical music, the rhythm instrument for the dhrupad is the double-headed drum pakhawaj and for the khyal, which is more popular today, the kettle drum pair tabla .

According to the historical sequence, three groups of shabad kirtan musicians can be distinguished: the tradition of Muslim lute players ( rabābi ) begun under Guru Nanak , the amateur singers ( raggi ) introduced by the fifth guru, Guru Arjan (1563-1606), and the amateur singers ( raggi ) introduced by Guru Nanak sixth guru, Guru Hargobind (1595–1644), promoted musician type dhadi . A raggi ensemble consists of three people: a precentor seated in the middle who also plays the harmonium and after whose name the group is named, another singer who plays the harmonium or a stringed instrument (e.g. the string sarangi ) or pair of cymbals and a drum player with tabla or jori . The name jori ("pair") refers to a pair of single-headed cylinder drums placed next to each other according to the tabla . Both drums have a wooden body and produce lower and louder tones than the tabla pair.

The dhadi group, introduced at the beginning of the 17th century, sings heroic songs ( var ) in a form of ballad singing ( parsang ) , in which the painful history of the Sikhs, often associated with battles against Muslim rulers, is told as a succession of heroic deeds by warriors and martyrs becomes. The dhadi groups played at religious gatherings ( sangat ) and in front of soldiers. The popularity of these groups, who have little or no knowledge of classical music, is due to their emotional style of singing and the use of Punjab folk song melodies. A dhadi group consists of three to four members: two people beat the small hourglass drum that gives it its name, dhadd, and one plays sarangi. There is also a narrator who tells the historical stories ( itihasak prasanga ). There is a clear dividing line between kirtan and dhadi groups within the religious sphere of the Sikhs. The strictly classical music- making kirtan groups sit in the immediate vicinity of Guru Granth Sahib , while the dhadi musicians , who always play while standing, never come near him. In general, Sikh musicians use drums ( tabla, dholak , jori, dholki ), stringed instruments for a drone tone , the harmonium (which is considered inappropriate by those educated in classical music) and, as a characteristic percussion instrument, the metal tongs chimta to accompany songs .

Gobind Singh Mansukhan (1982) distinguishes six types of shabad kirtan according to the proportion of music and song :

- The classical form of music from raga and tala and their perfect performance are in the foreground, the lecture by gurbani (hymns written by the ten Sikh gurus and other authors of sacred texts) is of secondary importance.

- The dominant sound of the musical instruments is considered more important than the musical quality and makes the sung text difficult to understand.

- Conversely, the exact texts of the hymns and the conveyance of their meaning to the audience are in the foreground.

- Intermediate explanations ( viyakhia ) in the liturgical framework make the religious meaning of the verses even more prominent, at the expense of song and music.

- The musicians choose the kirtan according to the wishes of the audience, which serves their entertainment and the money making of the musicians.

- Group chant by believers singing popular shabad kirtan to the accompaniment of dholak, kartal and chimta .

A special term is kirtan chaunki . So a shabad kirtan is called , which is performed in a gurdwara in a ceremony corresponding to the time of day . Kirtan chaunki , the religious service through music at a gathering in a Sikh temple, is embedded in a cyclical sequence of ritual acts. This concerns the rhythmic cycles of the music and the daily routine, which includes the ritual circumnavigation of the sanctuary (place of Guru Granth Sahib during the ceremony). Chaunki literally means "quarter" and refers to a wooden platform on which an ensemble of at least four raggi (singers and drummers) sings hymns to the assembled community, and to the singing performance itself. This is never considered a concert, but a kind Prayer.

Kirtan chaunki is musically divided into five parts:

- Shan , an instrumental prelude with a string instrument and drum accompaniment

- Mangalacharan , a song of invocation (in Hindu performances to invoke the gods) with a short excerpt from Guru Granth Sahib, performed at a slow pace

- Shabad , in which the singer recites a hymn in a certain raga in the classic dhrupad or khyal style

- Shabad rit , a hymn in a light classical style

- Pauri , a final composition in a special rhythm with four beats and in the style of folk music.

From the first gurus to the present day and from the main settlement area of the Sikhs in Indian Punjab to their global distribution, the shabad kirtan underwent major changes up to its eclectic adoption into a kind of world music in western countries. For example, the Australian Dya Singh World Music Group sang kirtan in the United States in 2003 to accompany a harmonium and a didgeridoo . In the 2000s, the American singer Snatam Kaur , a member of the American Sikh organization 3HO (“Healthy, Happy, Holy Organization”) became widely known for New Age music in which she dressed in a long white robe dressed in Sikhs, performing a mixture of Sikh kirtan , Celtic and Indian chants, western folk music and elements of jazz.

Christian kirtan

Tamil Nadu

Christians in India form minorities of varying strengths across the country and are divided into a large number of faiths. Their range extends from the Thomas Christians , who by the apostles Thomas name and its tradition on the southwest coast ( Kerala ) possibly began in the 4th century, on since the occupation by the Portuguese in the 16th century in Goa living Goan Catholics who Anglicans dating back to the British colonial era to the Baptists , who were evangelized between the beginning of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century and who make up the majority of the population in Nagaland in the extreme northeast of India. Even if Christian proselytizing has been associated with Western culture since the colonial times, apparently opposed to Indian culture and, for example, by rejecting the Hindu caste system, had a social revolutionary claim, the Christians adopted a number of Hindu elements in their everyday culture and religious ritual practice. This includes the appropriation of the devotional music genres kirtan and bhajan . In this process, called “Christian indigenization ” in research , statements of Christian theology are expressed through ethnic traditions.

A good two thirds of the Protestants in Tamil Nadu belong to the Dalits , who maintain a wide range of their own musical styles for their Christian ceremonies. The Christian music of the Tamil Dalits has developed in the exchange between the different ethnic groups, castes and the influences of western missionaries since the colonial times. In addition, high- caste Tamil Christians belonging to the Vellalar have provided Carnatic Christian (classical South Indian) music since the end of the 18th century or the beginning of the 19th century through the mediation of Protestant missionaries in the villages of the casteless Dalits. The Christian Vellalar in the districts of Thanjavur and Tirunelveli were the first to compose kirttanai . Since then, the main Christian form of singing in Tamil Nadu has been the kirttanai . He came from the devotional music style of the Vishnuit and Shivaite Brahmins in the Christian worship ceremony. The Vellalar used carnatic ragas, talas and the three-part form of classical music ( pallavi, anupallavi, caranam ). The caranam (verses) refer to the poems often sung by the whole congregation during the Bhakti cult. They also adopted melodies from composers such as Tyagaraja (1767-1847).

At the beginning of the 1820s, Anglican missionaries declared the classical kirttani style to be inappropriate, whereas the Protestant court poet and composer in Thanjavur, Vedanayagam Sastriar (1774–1864, both belonged to the Vellalar), was the most famous Protestant court poet and composer in Thanjavur at the time Music was given special value as a style of the elite upper caste. An American missionary published a collection of over 100 kirttanai composed by Sastriar in 1853 in order to popularize them among the low-caste Tamils. In addition to the " civil " kirttanai , there were noisy processions of the Catholics with the barrel drum tavil , the long cone oboe nadaswaram and fireworks. Sastriar apparently preferred classical musical instruments to instruments of folk music. The kirttanai acted from the middle of the 19th century as a carrier of religious values (also purity laws ) from the upper castes to the Shudras (lower castes ) and Dalits.

After the middle of the 20th century, Tamil Protestants began to culturally upgrade elements of village folk music. The Protestant Dalit theologian JT Appavoo declared folk music to be appropriate for Christian worship and in particular as suitable for the liberation theology of the Dalits. Folk music, elevated to a form of protest, allows an "indigenization" of Tamil Christianity. In this context, the ancient, simple frame drum parai (also thappu ) became a cultural symbol of the Tamil Dalit movement and the genre kirttanai was enriched with stylistic elements from Tamil folk music. Little remained of the melodic structure of the original raga; instead, the takeover of the harmonium in the 1940s inevitably introduced the western tempered mood with simple melodies. The turn of the Protestant Tamils to the Tamil folk culture belongs to the antibrahmanic Dravidian movement (cf. the national movement after an independent Dravida Nadu ), whose musical aspect is known as Tamil Isai Iyakkam ("Tamil Music Movement").

Odisha

In Odisha , where the kirtan of Bengal from reached, lead Christians in the villages and at festivals kirtan in the form of religious songs, stories and play actions. Circle dances are a specialty. The two-headed clay drum mrudanga and the hand cymbals ginni are indigenous accompanying instruments for sung kirtan in Bhubaneswar , while the frequent use of the two-headed dholak is considered inappropriate because it is not an instrument from the region. Otherwise, in Odisha the rhythmic accompaniment of the kirtan consists of the drum khol and the cymbal kartal .

Kerala

The Christians in Kerala , who make up around 19 percent of the total population of the state, are divided into a large number of denominations that observe their own liturgies. While the Syriac Orthodox Church and the Syro-Malabar Church have retained the tradition of a canon sung in Malayalam with ancient modes , the Latin Church in 1967 replaced unison chant in the liturgy with European polyphony. In the 1970s, a popular devotional style of singing with Western and Indian musical instruments became widespread with the help of the newly released audio cassettes. This trend continued in the 1990s with a mixture of western and Indian styles on the one hand. The latter includes Christian kirtana compositions in the style of carnatic music with lyrics in Malayalam. One of the most famous Christian composers from Kerala in the Hindu Bhakti tradition was George Panjara (1938-2017)

Jewish kirtan

Of the four or five Jewish communities in India , the Cochin Jews and the Beni Israel have lived the longest in India, according to legends since pre-Christian times. The Cochin Jews are evidenced by an Old Tamil inscription dated no later than the 10th century. European travelers have reported since the 16th century to have seen Jews in the settlement areas of the Beni Israel in northwestern India (today mostly on the coast of Maharashtra, few in Gujarat ).

The liturgical language of Beni Israel is Hebrew , the colloquial language in Maharashtra Marathi . In their church services, they distinguish between two styles of singing, melody instruments (such as harmonium, bulbultarang , sarod , violin, bamboo flute) and tabla may only be used outside of the liturgy . In the 19th century, the Beni Israel adopted the Hindu naradiya kirtan style of music for singing biblical narratives in Marathi, particularly for reciting the story of Joseph known as kirtan Yosef . Before the 18th century, they followed few Jewish religious norms. Taking over the naradiya kirtan and filling it out with Jewish texts served the Beni Israel to reassure themselves that they were Jewish.

Further regional distribution of kirtan

In Madhya Pradesh , ramsatta is a type of kirtan in which young men sing and dance accompanied by double-headed drums and a harmonium.

The ecstatic sankirtana from West Bengal was introduced in Odisha, the choral singing of which is accompanied by the drum khol and the cymbals kartal . There are kirtan groups in almost every village in Odisha . In a special form of performance called asht prahar , the participants play and sing 24 hours without a break.

Kirtan outside of South Asia

The kirtan came to the United States at the beginning of the 20th century . The Bengali yoga master and spiritual leader Yogananda (1893–1952) gave a lecture in the packed Carnegie Hall in New York in 1923 , at which, according to media reports, he was the first in the United States to sing kirtan at an event . He performed the well-known kirtan composed by Guru Nanak called Hay Hari Sundara (“God so wonderful”). Because of the great enthusiasm of the audience, Yogananda sang kirtan regularly in his evening speeches from now on . In the 1960s, kirtan chanting spread throughout the United States mainly through the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON) founded by AC Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (1896–1977 ), whose followers were called Hare Krishnas. Inspired by their missionary efforts, members of the Hare Krishna sect founded numerous temples in the United States, Canada, and many other countries. There, Hindu rituals for Krishna, including annual temple festivals and kirtan performances, are offered based on Indian models . From the Hare Krishnas, the chanting of kirtan entered the New Age scene and moved away from its original religious contexts. Through North American yoga studios, kirtan became a type of spiritual wellness offering that is supposed to serve as a means of reducing stress.

The form of chant practiced in the United States is similar to nam kirtan , which essentially repeats the names of deities, including Rama, Krishna, Hanuman, and Durga . In the Americanized versions, the typical Indian accompaniment instruments for the alternate singing (drums dhol , dholak and tabla , harmonium and the hand cymbals jhanjh or kartal ) are replaced by guitar, violin, keyboards and various percussion instruments. The verses consist of a mixture of English phrases, excerpts from the Granth Sahib of the Sikhs, the Jewish Torah and from the Christian tradition, which are usually intoned with catchy melodies that correspond to the laws of Western harmony.

Such spiritual music composed of religious elements made David Newman a successful composer, singer and bestselling author. Under the stage name Durga Das, he sings verses in Sanskrit and English to melodies that are based on well-known pop songs. Like Newman, Benjy Wertheimer is of Jewish origin. Wertheimer has been combining a New Age sound carpet with a kirtan since 2000 , the verses of which are written in Hebrew and Sanskrit and describe a spirituality known as " Nadabrahma ". The American singer Krishna Das (bourgeois Jeffrey Kagel, * 1947) combines New Age with Hindu kirtan and in Germany the singer Deva Premal (bourgeois Jolantha Fries, * 1970) creates a corresponding connection.

Snatam Kaur combines New Age and the group Dya Singh world music with Sikh kirtan. There is also devotional music, which is supposed to maintain the cultural identity of the Sikhs in the diaspora and therefore resists modernizations of this kind. This applies to the Sikhs who are now over a million strong and who have emigrated from Punjab to all over the world since the 19th century. For example, Sikhs established the first Gurdwara in Kenya in Mombasa in 1892 . There and in the numerous subsequently founded Gurdwaras in Kenya and Uganda , gatherings took place at which the community ( sangat ) or the priest ( granthi ) of Gurdwara sang kirtan . From the mid-1960s onwards, many of these Sikhs relocated to the United Kingdom, making East Africa an essential distributor for the dissemination of international Kirtan forms of the Sikhs.

Already during the colonial period, Sikhs had emigrated directly from India to the United Kingdom, where they founded a Gurdwara in London shortly after 1900 . There, the often musically uneducated parishioners sang kirtan . The first classically trained raga singers ( raagis ) came from India to Great Britain and the United States in the 1970s. With the Sikhs in the diaspora, the kirtan has a meaning as a symbol of identity alongside the secular folk music style bhangra .

literature

- Alison Arnold (Ed.): Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. Volume 5: South Asia. The Indian Subcontinent. Routledge, New York / London 2000

- Guy L. Beck: Kirtan and Bhajan in Bhakti Traditions. In: Brill's Encyclopedia of Hinduism , Volume 2, 2010, pp. 585-598

- Tama Debnath, Rabindra Bharali: Padavali Kirtan of Bengal. (PDF) In: Sangeet Galaxy , Volume 7, No. 1, January 2018, pp. 5–10

- Just Graves: The Marketplace of Devotional Song: Cultural Economies of Exchange in Bengali Padāvalī-Kīrtan. In: Ethnomusicology , Volume 61, No. 1, Winter 2017, pp. 52–86

- Gobind Singh Mansukhani: Indian Classical Music and Sikh Kirtan . (PDF) Oxford University Press, London 1982

- Janice Faye Protopapas: Sikh Śabad kīrtan as a musical construction of memory. (Dissertation) University of Maryland, 2011

- Navtej K. Purewal, Harjinder S. Lallie: Sikh Kirtan in the Diaspora: Identity, Innovation, and Revivalism. (PDF) In: Michael Hawley (Ed.): Sikh Diaspora. Theory, Agency, and Experience. Brill, Leiden 2013, pp. 381-403

- Anna Schultz: Hindu Nationalism, Music, and Embodiment in Marathi Rāshṭrīya Kīrtan. In: Ethnomusicology , Volume 46, No. 2, Spring – Summer 2002, pp. 307–322

- Zoe Sherinian: The Indigenization of Tamil Christian Music: Musical Style and Liberation Theology . In: The World of Music , Volume 47, No. 1 ( Musical Reverberation from the Encounter of Local and Global Belief Systems ) 2005, pp. 125-165

- Zoe C. Sherinian: Musical Style and the Changing Social Identity of Tamil Christians. In: Ethnomusicology , Volume 51, No. 2, Spring – Summer 2007, pp. 238–280

- Stephen M. Slawek: Popular Kīrtan in Benares: Some “Great” Aspects of a Little Tradition. In: Ethnomusicology , Volume 32, No. 2, Spring-Summer 1988, pp. 77-92

- Davesh Soneji: The Powers of Polyglossia: Marathi Kīrtan, Multilingualism, and the Making of a South Indian Devotional Tradition . In: International Journal of Hindu Studies , Volume 17, No. 3, December 2013, pp. 239-269

- Jyoshna La Trobe: Red Earth Song. Marāī Kīrtan of Rāṛh: Devotional singing and the performance of ecstasy in the Purulia District of Bengal, India. (PhD thesis) SOAS University of London, 2010

Web links

- Kirtan . In: Banglapedia , August 18, 2014

- Jatinder Singh: History of Gurmat Sangeet . Raj Academy, Telford (UK)

- Song Of The Divine - Mahesh Kale, Prof. Anna Schultz - Highlights - 4 May 2014, Stanford University . Youtube video

Individual evidence

- ↑ Walter Kaufmann : Old India. Music history in pictures. Volume 2. Ancient Music . Delivery 8. VEB Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1981, p. 13f

- ↑ Walter Kaufmann, 1981, p. 20

- ↑ Guy L. Beck, 2010, p. 588

- ^ Alain Daniélou : South Asia. Indian music and its traditions. Music history in pictures. Volume 1: Ethnic Music . Delivery 4. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1978, p. 8f

- ↑ Guy L. Beck, 2010, pp. 589f

- ^ Alain Daniélou, 1978, p. 46

- ↑ Guy L. Beck, 2010, p. 589

- ↑ Guy L. Beck, 2010, p. 590

- ↑ Stephen M. Slawe, 1988, pp. 79, 85

- ↑ Meena Banerjee: Bangla kirtan exponent Suman Bhattacharya unravels the fascinating journey of the art form. The Hindu, December 7, 2018

- ↑ Anna Schultz, 2002, p. 309

- ↑ Guy L. Beck, 2010, pp. 585f

- ↑ Guy L. Beck, 2010, pp. 591f

- ↑ James G. Lochtefeld: The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Volume 2. The Rosen Publishing Group, New York 2002, p. 673

- ↑ Guy L. Beck, 2010, p. 592

- ^ Gordon Thompson: Gujarat. In: Alison Arnold (Ed.): Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. 2000, p. 632

- ↑ Amaresh Datta (Ed.): Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature. Volume 2: Devraj to Jyoti . Sahytia Akademi, New Delhi 1988, p. 1268, sv “Fiction”

- ^ Sushil Kumar De: The Akhyayika and the Katha in Classical Sanskrit . In: Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies , Volume 3, No. 3, University of London, 1924, pp. 507-517, here p. 508

- ↑ Sujit Mukherjee: A Dictionary of Indian Literature: Beginnings – 1850. Orient Longman, Hyderabad 1998, p. 170, sv “Katha (Sanskrit)”

- ^ Francesca Orsini: Texts and Tellings: Kathas in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. In: Francesca Orsini, Katherine Butler Schofield (Eds.): Tellings and Texts. Literature and Performance in North India. Open Book Publishers, 2015, pp. 327–357, here pp. 327f

- ^ HK Ranganath: Katha-Kirtan. In: India International Center Quarterly , Volume 10, No. 2, June 1983, pp. 199-205, here pp. 199f

- ↑ HK Ranganath, 1983, pp. 201f

- ↑ Swami Prajnanananda: The Gitagovinda-Padagana in the background of the Padavali-Kirtan of Bengal . In: The Journal of the Music Academy Madras , (PDF) Volume 36, 1965, pp. 176-182

- ↑ Sanskrit prabhanda , "composition", denotes a genre of medieval Sanskrit literature and rupak a sung poetry. Rupak prabandhas are used to sing ragas.

- ↑ Tama Debnath, Rabindra Bharali, 2018, p. 6

- ↑ According to other data: Dwija Candidasa (1390-1430). There were several kirtan poets named Chandidas, who are differentiated according to their place of origin, cf. Jyoshna La Trobe, 2010, p. 56; K. Ayyappa Paniker (Ed.): Medieval Indian Literature. An Anthology . Volume 1: Surveys & Selections. Assamese. Bengali. Dogri. Sahitya Akademi, New Delhi 1997, p. 31f

- ↑ Panchali. Banglapedia

- ↑ Karunamaya Goswami: West Bengal and Bangladesh. In: Alison Arnold (Ed.): Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. 2000, pp. 844f

- ↑ Jyoshna La Trobe, 2010, p. 59f

- ↑ Jyoshna La Trobe, 2010, p. 61

- ↑ Eben Graves, 2017, p. 55

- ↑ Anwar Ali: “Kheturi Festival”: A tradition spanning over four centuries. The Daily Star, October 28, 2008

- ↑ Brajabuli. Banglapedia

- ↑ Jyoshna La Trobe, 2010, pp. 120f

- ↑ Tama Debnath, Rabindra Bharali, 2018, p.7

- ↑ Eben Graves, 2017, p. 53

- ↑ Guy L. Beck, 2010, p. 595

- ↑ Eben Graves, 2017, p. 56f

- ↑ Jyoshna La Trobe, 2010, pp. 25-27

- ↑ Jyoshna La Trobe, 2010, p. 127

- ↑ See Richard Widdess: Text, Orality, and Performance in Newar Devotional Music. In: Francesca Orsini, Katherine Butler Schofield (Eds.): Tellings and Texts. Music, Literature and Performance in North India. Open Book Publishers, Cambridge 2015, pp. 231–245

- ^ Norbert Beyer: India. VIII. Musical instruments. 3. Membranophone. In: MGG Online , November 2016

- ↑ Jyoshna La Trobe, 2010, pp. 106f, 148

- ↑ Guy L. Beck: Divine Musical Instruments. In: Knut A. Jacobsen, Helene Basu, Angelika Malinar, Vasudha Narayanan (eds.): Brill's Encyclopedia of Hinduism Online . 2018, pp. 1–10, here p. 7 ( doi: 10.1163 / 2212-5019_beh_COM_000339 )

- ↑ Jyoshna La Trobe, 2010, p. 45 f.

- ↑ Jyoshna La Trobe, 2010, p. 81

- ^ Alain Daniélou : South Asia. Indian music and its traditions. Music history in pictures. Volume 1: Ethnic Music . Delivery 4. Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1978, p. 46

- ↑ Jyoshna La Trobe, 2010, p. 91

- ↑ Guy Beck: Religious and Devotional Music: Northern Area. In: Alison Arnold (Ed.): Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. 2000, pp. 247, 250