Proto-Bulgarians

Proto -Bulgarians (occasionally also original Bulgarians or Hunno-Bulgarians ) is a scientific name for various, mainly Turkic-speaking tribal associations of the Eurasian steppe zone , which have appeared in written sources under the ethnonym "Bulgarians" since the 5th century . Their language is called the Bolgarian language . The proto- Bulgarians found larger empires east and west of the Sea of Azov ( Megale Boulgaria , see Greater Bulgarian Empire ), in the Balkans ( First Bulgarian Empire ) and on the central Volga ( Volga-Kama-Bulgaria ). The proto-Bulgarians who immigrated to the Balkans were Slavicized in the early Middle Ages (7th – 10th centuries). They adopted Christianity in the 9th century and are counted among the ancestors of today's ( Slavic-speaking ) Bulgarians . The Volga Bulgarians in Russia, however, adopted Islam in the 10th century .

Ethnonym

There are numerous theories about the meaning of the popular name “Bulgarians” ( Greek Βούλγαροι). It was often derived from the river name of the Volga ( Volgars ). The most widespread theory is that the name "Bulghar" is derived from the proto- Bulgarian "bulganmış" , which means "mixed" and indicates a federation of ethnically heterogeneous associations.

Some Bulgarian researchers such as Nikolay Ovcharov and Georgi Balakov include the proto-Bulgarians to the descendants of the ancient Bactrians that the region around Balch populated, of which the name is derived ( Balkh ar - Bolg ar); However, this represents a minority opinion. Others, in turn, see the Proto-Bulgarians as tribes of the Hun Empire (the so-called Hunno-Bulgarians) who retreated eastwards after the Battle of Nedao and settled on the lower Volga. In general, many points in research are still controversial today.

history

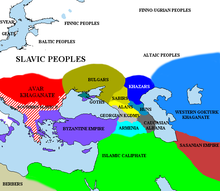

The Proto-Bulgarians were probably Turkic-speaking nomadic tribes from Central Asia . Their exact origin has not yet been fully clarified. According to some researchers, they should be in the 4th / 5th They joined forces with the Huns in the 19th century. After the death of the Hun leader Attila (453) and the collapse of the Hun empire, the proto-Bulgarians settled in the Pontic steppe (southern Russian steppe) north of the Black Sea and in Central Asia. There were also Finno-Ugric and Ural-Altaic tribes. They were joined by the Turkic peoples of the Sagurs and Ogurs, who around 463 had been displaced to the west by the linguistically related Sabirs from their homeland in what is now western Siberia and Kazakhstan . The new "League", to which the old Hungarians ( Onogur - "Ten Tribes") and Alanic elements also belonged, was under the leadership of Attila's son Irnik (according to the Bulgarian list of princes ).

In recent research, many points regarding the origin and development of the Proto-Bulgarians are controversial. Many of the older explanatory models are viewed more critically and the thin and sometimes contradicting sources are pointed out.

The role of the kutrigurs and utigurs in the process of ethnogenesis of the proto-Bulgarians is also problematic . According to legendary reports in the sources, the Kutrigurs and Utigurs are said to have descended from the remains of the Huns, but this is uncertain. Around 550 there was fighting between them, driven by the Eastern Roman side; they were eventually defeated by the Avars . Parts of these groups may later have joined the proto-Bulgarians or have already been identical with them, but this is unclear. In the late antique sources (the main source for this is Prokopios of Caesarea ) these groups are also not referred to as Bulgarians.

Shortly before 558 the proto-Bulgarians were defeated by the Avars. Some joined the Avars and moved further west with them. Large parts of the Proto-Bulgarians, "Huns" (the name in the sources often simply refers to "barbaric peoples" from the region north of the Black Sea) and the other equestrian nomads remained in the southern Russian steppes. In 635, the proto-Bulgarian Onogurs under Khan Kubrat (also Kobrat, from qobrat - "gather the people") rose successfully against the rule of the Avars. Kubrat united the peoples to the Greater Bulgarian Empire (Greek Η παλαια μεγαλη Βουλγαρια; megale Boulgaria - "Greater Bulgaria"). He was allied with Byzantium . On this occasion, Kubrat received the honorary title of Patricius from the Byzantine Emperor Herakleios .

The Greater Bulgarian Empire on the north coast of the Black Sea extended from the Maeotis to Kuban . The capital was Phanagoria on the Sea of Azov not far from today's Taman . At the head of the empire stood the Khan and at his side a council of nobles (Great Boilen ) was established. The second man in the empire was the Kawkhan (held several functions, including supreme commander of the armed forces and diplomat ), the third was the Ichirgu-Boil (administrator of the capital and commander of the capital's garrison ). As the highest administrative officials and military commanders, they have a double function that is continued in the subsequent levels of the administrative hierarchy. Some theories see the medieval nobility title Boljaren as a Slavic derivation of the Ur-Bulgarian title Boil . The Greater Bulgarian Empire was destroyed by the Khazars, who were also of Turkic origin, in the second half of the 7th century .

Kubrat's eldest son Batbajan had submitted to the Khazars and stayed in the old capital Phanagoria. But his four brothers split off with significant tribal parts. The Proto- Bulgarians moving northwards under the leadership of Kotrag , the second son of Kubrat, founded the Volga-Bulgarian empire with its capital Bolgar . The Volga Bulgarian Empire existed until the beginning of the 13th century when it was defeated by the Golden Horde of Mongols . The Chuvash people see themselves as the successors of part of the Volga-Bulgarians. Another part merged with the Kazan Tatars , who called themselves "İdil Bolgarları" (İdil = Volga; Bolgarlar = Bulgarians) and not as "Tatarlar" (Tatars) until the late 19th century .

The parts moving to the southwest under Kubrat's son Asparuch crossed the Danube and allied themselves (subject to other opinions) with the local Slavic population of the Severen and the Seven Tribes and established the Danube- Bulgarian Empire with the capital Pliska in 678 . Asparuch is therefore considered to be the founder of today's Bulgaria in the Balkans . This Bulgarian empire was the first empire to be paid tribute by a Byzantine emperor, which was felt to be a great shame in Constantinople . Although contractually recognized by the Byzantine emperor Constantine IV , the proto-Bulgarians besieged Constantinople several times (705 and 813) and under Krum (802-814) extended their empire westward to the Tisza . However, in 718, during the Second Arab attack on Constantinople , Khan Terwel sent his army to the Byzantine Emperor Leo III. to help, which contributed to the lifting of the Arab siege. Until the Hungarian invasion in 895, the Bulgarian empire actually comprised the entire non-Byzantine Balkans and, after defeating the Avars, extended to Budapest in the north .

The two youngest sons of Kubrat, Kuver (Kuber) and Alzek , with their smaller tribal associations, also moved west and joined the Avars in Pannonia (Hungary). After a failed revolt against the tribal leadership, they parted ways again. As early as 680 Kuver moved south together with parts of the Sermesianoi , descendants of the Roman provincial population in Pannonia, and the Roman prisoners who had already been abducted by the Avars and settled in Pannonia in 626. He settled in the unpopulated area around Bitola in Macedonia , which was part of the Byzantine theme of Thessalonica , where Kuver established a khaganate . Under Khan Malamir and Khan Presian I , the Kuverbulgars united with the Bulgarian Empire of Asparuch. In the year 1000, under Tsar Samuil and his successors , its capital was also to become the capital of all of Bulgaria.

Alzek moved further west, crossed the Alps in 667 and moved peacefully to northern Italy in the Ravenna area . So says Paul the Deacon of the arrival of Vulgarum dux Alzeco nomine , who was, however, come for unknown reasons in peace with his army to Italy. The hospitality of the Romans was only a cover. In the same year, the Bulgarians had to fight for their survival in several ambushes. Therefore, they moved further and further south until they finally reached the Duchy of Benevento . The historian Paulus Diaconus further reports that Khan Alzek was received there by the Longobard king Grimoald . Alzek was awarded the Molise region , on the condition that he renounced his title dux and claim to power, since Grimoald himself was dux of Benevento. Even today, mountains, regions, villages, rivers and families all over Italy bear Bulgarian names or the designation "Bulgarians" ( Bulgarian Bulgari ). Examples are the Italian luxury goods manufacturer Bulgari , Bartolomeo Bulgarini , Cardinal Pietro Bulgaro , the name del Bulgaro or the municipality of Bulgarograsso .

The cultural heritage of the Proto-Bulgarians was preserved in a number of architectural monuments, for example in around 100 chiseled monuments in writing with Proto-Bulgarian script from the time of the Danube-Bulgarian Empire or in pictorial representations. Some like the Madara Horseman have been named UNESCO World Heritage Sites .

In Bulgaria and Macedonia, the Proto-Bulgarians merged mainly with Slavic tribes and the remnants of the Roman provincial population to form today's Bulgarian people. The relatively thin proto-Bulgarian ruling class quickly became part of the majority of the population of the four subjugated Slavic tribes, but only after the Christianization of the Bulgarians is no longer differentiated between Bulgarians and proto- Bulgarians . The Proto-Bulgarians ruled the Danube-Bulgarian Empire until it fell under Byzantine rule in 1018.

Timetable

There are numerous theories about the origins of the Bulgarians and the meaning of the popular name "Bulgarians", most of which are not supported by facts or historical documents.

The first mention of the Bulgarians can be found in the chronograph from 354 . According to this source, the Bulgarians lived in the region between the Black, Caspian and Azov Seas. Cassiodorus informs us that the Bulgarians were still at war with the Roman Empire during the time of the Roman Emperor Theodosius I and were defeated around 390. The Lombard historian Paulus Diaconus writes in his Historia Langobardorum that the Bulgarians attacked and killed the first Lombard king Agelmund around 440 and his successor Lamissio resumed the war with the Bulgarians. John of Antioch , a late antique historian, reports that around 480 the Roman Emperor Zenon used the Bulgarians against the attacks of the Ostrogoths on the territory of the Balkan Peninsula. Magnus Felix Ennodius in his Panegyricus on the Ostrogoths King Theodoric the Great and Cassiodorus confirm that the Bulgarians were defeated by the Goths around 485 near Syrmia . According to Marcellinus Comes , a late antique Roman historian, and his chronicle of 520, the Bulgarians 499 are found in a successful battle against the Magister Millitum of Illyria .

According to the important Eastern Roman chronicler Theophanes , the Bulgarians from Illyria and Thrace attacked Eastern Europe in 497/502 . 514 Bulgarians of Theophanes as soldiers were Vitalian , governor of Thrace, mentioned when he against Emperor I. Anastasios rebelled.

Theories on the origin of the Proto-Bulgarians

To date, research has not been unanimous about the origin of the Bulgarians. The prevailing thesis today is based on a Turkic origin.

Research into the Proto- Bulgarians began in 1832 when Christian Martin Frähn classified the name of Asparuch as Persian when interpreting Arabic news about the Volga Bulgarians. With the work of Wassil Slatarski History of the Bulgarians I: From the founding of the Bulgarian Empire to the Turkish era (679-1396) from 1918, the author advocated a possible Hunnic descent. This thesis found widespread use in Bulgaria until the communists came to power in 1945 and was also written down in school books. During the communist era, this opinion was replaced by consideration of possible ancestry from the Turkic peoples. The older thesis builds its findings primarily on archaeological research and excludes any possible influence of the Turkic peoples, for example on the titulature and grave goods. Wesselin Beschewliew started the discussion in 1967 with two articles on the ancestry of the Bulgarians. In it he accepted the Turkish ancestry of the proto-Bulgarians, but at the same time drew attention to Iranian influences.

Since the late 1980s, research in support of the Indo-Iranian thesis has been intensifying, especially in Bulgaria . So today applies the earlier u. a. discussed by Rüdiger Schmitt and Steven Runciman , at least partial cultural influence of Iranian peoples on the proto-Bulgarians as certain. The Encyclopædia Iranica also points to the cultural influence, above all to the Central Iranian names Asparuch ("the one with the shining horse") and Berzmer (from Pers. Burzmehr , "highly praised Mithras "), as well as the figure of the "Madara rider" which is carved in stone near the ruins of Pliska and is said to be very reminiscent of the “Naqše Rustam” rock reliefs of the Persian Sassanids . The Bulgarian list of princes also shows Iranian features. New archaeological findings also show possible Zoroastrian fire temples under the main churches in the capitals Pliska and Preslaw . According to some Bulgarian researchers such as the historian Georgi Bakalow , the proto- Bulgarians were not only under Iranian influence, but also had ancient Indo-Iranian roots. According to Bakalov, the Bulgarians were later under the influence of the Turkic tribes of the Gök Turks and took over the title and social structure from them. However, this thesis receives little attention in Western European specialist circles.

More recent works by Petar Dobrew , with which he again connects the Proto-Bulgarians with the Indo-European tribes of Central Asia, are very popular in Bulgaria, but are criticized abroad as speculative, since Dobrew only considers elements such as a few names and ignores other findings about the Proto- Bulgarians . The Proto-Bulgarians were associated with the ancient Pamir peoples and their languages as well as with Avestian and Sanskrit , especially with ancient Bactria . These theories refer to a significantly earlier period than the time of the proto-Bulgarian migration to Europe. However, these theories find little support in expert circles.

The Proto-Bulgarians had their own runic script , their own calendar and their own religion, whose supreme deity was the sky god Tangra . In addition to the above-mentioned theory, there are other theses, especially widespread in Bulgaria, that reject the Turkic descent of the Proto-Bulgarians and a possible connection between the Proto-Bulgarian god Tangra and the god Tengri , who was worshiped by ancient Turkic peoples . The author Schiwko Woinikow goes from an alleged, but very questionable origin from the Sumerian term for "God" Dingir (Sumerian: ? , ![]() later

later ![]() ) from.

) from.

religion

The Proto-Bulgarians originally had a religion that was shaped by shamanism and ancestral cult . The supreme god was the sky god Tangra . It could be a name variation of the old Turkish sky god Tengri . Tangra is mentioned in almost all Proto-Bulgarian runic inscriptions. White horses were preferred as an offering to the sky god. The intestines of the sacrificed animals were used for divination.

Due to the traditional worship of mountains (e.g. Khan Tengri ), the highest mountain in the Balkans received the name of the god Tangra. It was only renamed Musala by the Ottomans in the 15th century . Smaller mountains were also worshiped, such as the Perperikon , which, however, had been a sacred place for the Thracians and other local peoples even before the Proto-Bulgarians . On the slope of this mountain there are still well-preserved cult buildings that were dedicated to the ancient Greek wine god Dionysus ( Zagreus among Thracians ). Proto-Bulgarian runic inscriptions with a relief of the Tengrist fertility goddess Umay can be found on the highest rock of Perpenikon .

In addition, the Proto-Bulgarians also worshiped the sun, the moon and the five planets known at the time, Jupiter , Venus , Mercury , Mars and Saturn .

Religious freedom prevailed in the multi-ethnic Bulgarian empires. The Proto-Bulgarians already had Christian, Jewish and Buddhist minorities when they lived on the northern shore of the Black Sea. Archaeological excavations and written records confirm this.

2001 Bulgarian researchers gave a Mountains Antarctica the name Tangra .

See also

literature

- Veselin Beševliev : The Proto-Bulgarian Period of Bulgarian History. Hakkert, Amsterdam 1981, ISBN 90-256-0882-5 .

- Florin Curta : Southeastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 500-1250. Cambridge 2006.

- Bojidar Dimitrov : Bulgaria Illustrated History. 2nd Edition. Sofia 2002, ISBN 954-500-091-0 .

- Edgar Hösch , Karl Nehring, Holm Sundhaussen (ed.): Lexicon for the history of Southeast Europe. Böhlau, Vienna / Cologne / Weimar 2004, ISBN 3-205-77193-1 .

- Gert Rispling: Volga Bulgarians. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 34, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-018389-4 , pp. 210-211.

- Jonathan Shepard : Slavs and Bulgars. In: The New Cambridge Medieval History . Volume 2. Cambridge 1995, p. 228 ff. (With a detailed bibliography on the subject of Bulgarians and Slavs [ibid., P. 915 ff.])

- Warren Treadgold : A History of the Byzantine State and Society. Stanford University Press, Stanford 1997, ISBN 0-8047-2630-2 .

- Daniel Ziemann: From wandering people to great power. The emergence of Bulgaria in the early Middle Ages. Böhlau, Cologne a. a. 2007, ( scientific review ).

Web links

- Rasho Rashev: On the origin of the Proto-Bulgarians (pp. 23–33 in: Studia protobulgarica et mediaevalia europensia. In honor of Prof. V. Beshevliev , Veliko Tarnovo, 1992) (Eng.)

- Rüdiger Schmitt: Iranica Protobulgarica. Asparuch and Co. in the light of Iranian onomastics

- Bulgarian Myth and Folklore. Background to Bulgarian Myth and Folklore: The Proto-Bulgarians (engl.)

- Bojidar Dimitrov: Extract from the book " Bulgaria Illustrated History " (English; PDF file; 525 kB)

- Peter Dobrev: Inscriptions and Alphabet of the Proto-Bulgarians ( alternative link to the same page )

- Velina Dimitrova: Evidence of the art and culture of the proto-Bulgarians from the pagan period of the First Bulgarian Empire (7th - 9th centuries)

supporting documents

- ↑ Harald Haarmann : Protobulgaren , in: Lexicon of the undergone peoples , Munich 2005, p. 225. General overview in: Ivan Dujcev: Bulgaria , in: Lexikon des Mittelalters , Vol. 2, Col. 915 ff .; René Grousset: Die Steppenvölker , Munich 1970, p. 249; Heinz Siegert: Eastern Europe - From the origin to Moscow's rise , Panorama of world history , Vol. 2, ed. by Heinrich Pleticha, Gütersloh 1985, p. 46; Walter Pohl : A Millennium of Migrations, 500–1500 (PDF; 2.1 MB). In: Vienna Encyclopedia of the European East 12, pp. 134 ff., 147

- ↑ a b c d e f g Hösch, Nehring, Sundhaussen: Lexicon for the history of Southeast Europe. 2004, p. 553.

- ^ Hösch, Nehring, Sundhaussen: Lexicon for the history of Southeast Europe. 2004, pp. 139-140.

- ↑ a b Nikolay Ovtscharow: History of Bulgaria. Brief outline , Lettera Verlag, Plovdiv 2006, ISBN 954-516-584-7

- ↑ Harald Haarmann: Protobulgaren , in: Lexikon der Untergegiegen Völker , Munich 2005, p. 225

- ^ René Grousset: The steppe peoples. Munich 1970, p. 249

- ^ Heinz Siegert: Eastern Europe - From the origin to Moscow's rise. (= Panorama of World History , Volume 2) edited by Heinrich Pleticha, Gütersloh 1985, p. 46.

- ↑ On the controversial origin of the Bulgarians see Daniel Ziemann: Vom Wandervolk zur Großmacht. The emergence of Bulgaria in the early Middle Ages. Cologne u. a. 2007, p. 32 ff.

- ↑ Overview of research by Daniel Ziemann: Vom Wandervolk zur Großmacht. Cologne u. a. 2007, p. 2 ff.

- ↑ Cf. Daniel Ziemann: From Wandering People to Great Power. Cologne u. a. 2007, pp. 95ff.

- ↑ Max Vasmer : Russian etymological dictionary. Vol. 1, Heidelberg 1976 (1st edition 1950), ISBN 3-533-00665-4 , s. v. bojarin ; Russian version online ( memento from September 29, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Friedhelm Winkelmann u. a .: Prosopography of the Middle Byzantine period . Vol. 1, de Gruyter, Berlin 1999, ISBN 3-11-015179-0 , pp. 62-63.

- ↑ Paulus Deacon : Historia Langobardorum . V, 29.

- ↑ On the culture of the Bulgarians in Italy

- ^ Mavro Orbini: Il regno de gli Slavi, Ragusa 1601

- ↑ Paulus Diaconus, Historia Langobardorum (ed. Georg Waitz, MGH SS rerum Langobardicarum, Hannover 1878) 12-187, §16, §17.

- ↑ Sergei Mariev (ed.): Ioannis Antiocheni fragmenta quae supersunt. Corpus fontium historiae Byzantinae 47.Berlin-New York 2008.

- ↑ The Theoderich-Panegyricus of Ennodius / Christian Rohr. Hanover: Hahn 1995

- ↑ James J. O'Donnell: Cassiodorus, 1979 University of California Press, Postprint 1995

- ↑ Marcellinus Comes, Chronicle

- ↑ Theophanes Chronographia, A, Anastas. 25 p. 138

- ^ Vasil Slatarski: History of the Bulgarians I: From the founding of the Bulgarian empire to the Turkish period (679-1396). Bulgarian Library 5, Leipzig 1918

- ^ Rüdiger Schmitt: Asparuch and consorts in the light of the Iranian onomastics. In: Linguistique Balkanique 28, 1958, pp. 20-30 full text

- ^ Steven Runciman: A History of the First Bulgarian Empire. London 1930, pp. 19-30, 273-78.

- ↑ DM Lang, Asparukh. In: Encyclopædia Iranica

- ^ See: The inscriptions and the alphabet of the Proto-Bulgarians , Petar Dobrew; Georgi Bakalow, Little Known Facts from Bulgarian History ; Boschidar Dimitrov , 2005. 12 мита в българската история (Bulgarian)

- ↑ Inscription and alphabet of the Proto-Bulgarians : второе (TANGRA) восходит к тому же корню, что и шумерское Dingir

- ↑ University of Saskatchewan, Andrei Vinogradov, Department of Religious Studies and Anthropology, November 2003 Page 78 ( Memento of the original from August 24, 2006 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 1.6 MB)

- ↑ See here under Perpenikon

- ^ Bojidar Dimitrov : Bulgaria Illustrated History. 1994