Prehistory of Palestine

The prehistory of Palestine ranges from the earliest human traces to the beginning of written tradition. Some representatives of Homo erectus left Africa around two million years ago. The oldest known traces in Palestine can be dated to 1.4 million years and were discovered south of the Sea of Galilee in the area of today 's Israel and Jordan . Another wave of migration followed about 600,000 years ago. At least 250,000 years ago, Neanderthals (stone-working techniques assigned to them could be proven) appeared in the region and others may have come from Europe in cold times, who lived here at the same time as the archaic Homo sapiens . It is considered the direct ancestor of modern humans, developed at least 200,000 years ago in East Africa and can be found in Palestine 110,000 years ago. Some of these anatomically modern people may have left Africa around 130,000 years ago. But they disappeared from Palestine 80,000 years ago, only to reappear 50,000 years ago. Again they lived with Neanderthals in the same region, and it is likely that they had common offspring. The Neanderthals disappeared 45,000 to 28,000 years ago. In the Jordan Valley , a 200 km long, 2,000 km² large lake v to 12,000 was 70,000 years ago. Existed. The people continued to live from hunting big game, smaller animals and fishing also played an increasingly important role, and collecting activities continued.

As early as 18,000 BC There are increasing signs of more permanent storage - a village-like structure has been proven - limited food production and wild barley was ground and baked. The main game were gazelles , and camps were created along their trails. Around 12,000 BC Houses made of semicircular stone placements with structures made of clay appeared, no later than 11,000 BC. Chr. Was grain grown. The signs of rituals and sacrifices increased, the dead were mostly buried in a contracted position, occasionally the skulls were buried separately. The art that had been quite abstract until then was supplemented by more realistic representations, which are considered the oldest pictorial documents of the Near East.

In the period between 9500 and 8800 BC Although agriculture was practiced, the production of clay pots was not yet known. The most important site is Jericho , which protrudes from the settlements, which were mostly less than half a hectare in size, with an area of 4 hectares. Around 8000 BC BC surrounded the city, sheltering perhaps 3000 people, a wall 3 m high, but between 7700 and 7220 BC. The city was uninhabited. Since 8300 BC Grain production, which had been limited to the Jordan Valley and the Golan Heights until then, expanded further to around 7600 BC. BC there was a strong expansion of the settlement area, which was accompanied by migration or with a stronger population growth. Most of the older settlements have been abandoned.

Jericho was rebuilt around 7220 and was until 6400 BC. Inhabited. The migration patterns of the epochs before the "mega-villages" were resumed around 7000, alongside permanent settlements continued to exist. Only after this phase did the stabilization take place, which provided the prerequisites for urban structures, and ceramics also came into use. Sha'ar HaGolan, a site of 20 hectares, is believed to be the largest city between 6400 and 6000 BC. Have been. Long-distance trade can be documented as far as Anatolia and the Nile ; migrations may have taken place there. Between about 5500 and 4500 BC There were no contacts with Egypt, probably due to climatic deterioration. Between 4400 and 4000 BC There again cattle husbandry and type of agriculture point to Palestinian origins. In the Copper Age , Teleilat Ghassul was one of the largest settlements in the Jordan Valley with an area of 20 hectares. It housed spacious houses measuring 3.5 by 12 m, as well as a temple. Between 3500 and 3300 BC There was a drastic cultural collapse, but traces of violence have not yet been proven.

This was followed by a Bronze Age epoch known as "early urban", which maintained trade relations far beyond Palestine, especially to Egypt. Egyptians can be found in a network of settlements along the trade routes to Palestine. Egypt, now centralized under a pharaoh , tried, sometimes by force, to gain control over raw materials between Sinai and Lebanon , which were of great importance for the enormous construction activity in connection with the pyramids there. The existence of numerous fortified settlements is likely to be closely related to these battles. More than 260 settlements with a total of perhaps 150,000 inhabitants are known from this era in Western Palestine alone, especially in Galilee , Samaria and Judah. Among them, Beth Yerah and Yarmuth were the largest with 20 and 16 hectares, some cities had city walls up to 8 m thick, Beth Yerah had perhaps 4,000 to 5,000 inhabitants. City gates and large temples like in Megiddo were built. At the end of the Early Bronze Age there was a breakdown in urban culture and the dominance of pastoralism. At the same time, "Asians" repeatedly attacked the Nile Delta until the Semitic Hyksos there after 1700 BC. Took over the rule.

Paleolithic

There is agreement among paleoanthropologists that both Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans ( Homo sapiens ) had a common ancestor in the African Homo erectus . Some representatives of Homo erectus left Africa during a first wave of expansion around two million years ago towards the Levant , Black Sea region and Georgia, and possibly via northwest Africa towards southern Spain. The early settlement of Georgia is documented by the 1.8 million year old fossils of Dmanissi .

Around 600,000 years ago there was probably a second wave of propagation of the African Homo erectus , which in Europe developed via the intermediate stage called Homo heidelbergensis to the Neanderthal, while in Africa at least 200,000 years ago Homo erectus became the so-called early or archaic anatomically modern man and from from this the anatomically modern man emerged.

A recalculation in 2012 showed evidence of a very early separation of the two human forms; it was dated between 800,000 and 400,000 years ago. The dating is supported, among other things, by the approximately 400,000 year old Swanscombe skull , which - although mostly still related to Homo heidelbergensis - already shows clear features of the early Neanderthals.

The Central European populations of Homo erectus or the Neanderthals and the ancestors of anatomically modern humans living in Africa lived spatially separated from one another for several hundred thousand years until the immigration of modern humans around 45,000 years ago. However, contacts between these populations took place in the Middle East. It is still largely unclear which path the respective migrations took after leaving Africa, including that of anatomically modern humans (Our Way to Europe). Above all, there is a lack of Asian skeleton finds older than 40,000 years. It has been suggested that the settlement might have already taken place more than 60,000 years ago, and there could also have been more than two advances, probably also intermingling with Neanderthals, Denisovans and Homo erectus .

Old Paleolithic (from 2.6 / 1.4 million years before today)

In Israel, at least four waves of immigration can be identified between 2.6 million and 900,000 years. The oldest stone tools outside of Africa were found at Yiron, near the border with Lebanon, and at Erq el-Ahmar. Both sites were dated to an age of 2.2 to 2.6 million years ago, but the dating is considered problematic.

Some finds, which were dated 1.4 million years ago, are assigned to the Acheuléen , the so-called Bizat Ruhama group and Gesher Benot Ya'aqov .

Often the Middle Eastern Acheulean is divided into three phases, early, middle and late. These are often used as a relative chronology. Nevertheless, most of the sites dating back over 700,000 years are attributed to the early Acheuleen.

The oldest secured site in Israel is in the 'Ubeidiya Formation, around 3.5 km south of the Sea of Galilee on both sides of the Jordan. Their age could be dated to 1.5 to 1 million years, the oldest find approximately 1.4 million years. By 1974 alone, 8,000 stone artefacts appeared, 39 stone tool inventories were analyzed; they range from 2 to 1000 pieces. It turned out that certain forms are bound to specific materials, such spheroids of limestone cores and debris equipment consisted mostly of flint , hand axes , however, usually made of basalt . Together with them, the remains of 80 species of mammals, 60 species of birds, as well as reptiles, fish and mollusks were found . Hunting as a survival strategy has already been proven here. There was also evidence of an exchange of fauna with Africa, such as the extinct hippopotamus Hippopotamus gorgops . From other sources it is known that there was specialization in certain animal species, even age groups or only certain parts of the hunted prey. The latter has been linked to the increased energy consumption of the growing human brain, which was offset by a reduction in energy consumption in the digestive tract. This in turn ensured specialization in more energy-rich animal parts. In the case of the later Neanderthals it could be shown that they even lived predominantly on animal protein (supercarnivores). Although human remains were found in 'Ubeidiya (mainly teeth, but also small remains of the skull), their quality did not allow any classification. Nor could it be proven what role the consumption of carrion might have played. It could not be clarified whether the consumption of meat, and therefore hunting, can be considered the engine of human development, although meat played a major role in 'Ubeidiya.

The Abu Khas excavation site is just a few kilometers southeast of 'Ubeidiya, on Jordanian territory. It is located in a high acropolis above Pella . Although no bones or teeth were found there, the tools discovered there point to the same era.

While these sites were excavated from this early phase, little is known about the Middle Acheuleen, which, according to stratigraphic studies, is roughly dated between 700,000 and 400,000 years ago. Finds are in the coastal area of Berzine in western Syria and Wadi Aabet , inland Joub Jannine II.

Mugharet el-Zuttiyeh (Cave of the Robbers) in Galilee is considered to be the first place where the remains of a hominin were found in Western Asia. The cave in which the 200,000 to 300,000 year old "Galilee man" found himself is 30 m above the Wadi Nahal Amud. The human remains of this man were assigned to Homo heidelbergensis . The first excavation took place there in 1925–1926, under the direction of Francis Turville-Petre . Initially, the find was placed next to the Neanderthals.

The archaeological site of Gesher Benot Ya'aqov ("Bridge of the Daughter of Jacob ") is located in the northern Jordan Valley on the banks of a Paleo lake. Its paleomagnetic dating indicates an age of 790,000 years. Hominins certainly lived here, but as there are no bone finds it is unclear whether it was Homo erectus or Homo ergaster . Organic substances such as wood, bark, fruits and seeds were analyzed, and numerous large basalt axes and hatchets were found. The assignment of the site to the Middle or Late Acheuleans is uncertain; it is characterized by unusually large discounts.

In addition, Gesher Benot Ya'aqov showed that the hominins divided the space they lived in outside the cave into two usage zones. There was a zone for the preparation and consumption of food, and a zone about 8 m away was used for the production of tools. Whether this is related to the establishment of a fireplace can only be guessed. In any case, there was also waste there. Some of the wood fragments and seeds show signs of burning, leading to the suggestion that this may be an early controlled use of the fire. If so, it would be by far the oldest recorded use of fire .

In order to classify the sites that arose at the same time as the late Acheulean sites, but were not dominated by their lithic technique, the name Tayacien was created. Here prevail reduction techniques for debris devices (pebble tools) before. The name goes back to the French Micoque cave near Tayac. Occasionally, the term tabunias appears after a cave in Israel (Tabun G), which, however, was better known through Neanderthal finds. They were found next to Tabun in Umm Qatafa.

Overall, there is nowhere near as long a rubble device phase in the Levant as in Africa, which preceded the large cutting devices. It remains unclear whether this can be explained by a wave of colonization from Africa or South Asia, or whether this is due to the small number of sites.

Middle Paleolithic (from approx. 245,000 - 47,000 / 45,000 before today)

In the Middle Paleolithic, both Neanderthals and anatomically modern people lived in the Middle East. Remains that could be assigned to the latter were discovered in the caves of Qafzeh and Skhul . Fossils that could be assigned to the Neanderthals were found at the sites of Tabun , Skhul, Amud , Kebara , Geulah B (a cave near Haifa ), then the cave of Shukhbah, and finally Dederiyeh in Syria. The most important concentration of Middle Paleolithic sites is found in the drainage system of Wadi el-Ḥasā in Jordan . Of the approximately 600 sites, around two thirds can be assigned to the Middle Paleolithic.

The simultaneous existence of the two representatives of the genus Homo has not yet been proven stratigraphically , but only through genetic studies. In view of this , it remains to be seen whether the classification of Neanderthals and modern humans into two species will endure, as there is no binding standard for determining the morphological or genetic distance from which separate species can be assumed.

But with the Middle Paleolithic since the 1920s, it was dominant that tools and remains of Neanderthals were discovered in caves in which very early traces of anatomically modern humans were also found.

In the HaYonim cave, artefacts up to 250,000 years old were found, especially stone tools worked with the Levallois technique , which are typical of the Middle Paleolithic.

The Misliya Cave is of similar importance to the early Middle Paleolithic . Their fauna is by far dominated by ungulate taxa. The most common prey was the Mesopotamian fallow deer ( Dama dama mesopotamica ), closely followed by the mountain gazelle ( Gazella gazella ), plus some remains of aurochs; small animals are rare. The hunted gazelles were completely brought into the cave, while the fallow deer were (partially) cut up beforehand. Middle-aged adult animals were preferred. The forms of big game hunting, the type of transport and cutting, and consumption were already in practice over 200,000 years ago. The traces of hunted prey in the Qesem Cave showed that after a joint hunt, the prey was brought into the cave to be cut up and consumed with the rest of the group.

Finds in this cave are assigned to the Amudien (about 400,000 to 200,000 before today), which is characterized by exceptionally early and systematic blade production, which is otherwise exclusively ascribed to anatomically modern humans. Other locations are Zuttiyeh, Yabrud I, Tabun E, Abri Zumoffen / Aadlun and Masloukh. The Amudien in turn presented the last four stages of the Acheulo-Yabrudien is, the findings stratigraphically above the Acheuléenschicht are, however, below that of the Moustérien .

In 1983 the burial of a Neanderthal child ( Kebara 1 ) and a man ( Kebara 2 ) was found in the Kebara Cave on the western steep slope of Mount Carmel , a site that can be dated to 60,000 years ago. The man's skullless jaw still had the hyoid bone, a U-shaped bone of the larynx skeleton, which is also present in people today and which suggests language ability. This only surviving hyoid bone from a Neanderthal man indicates that they had a high-pitched, powerful voice. The man died between the ages of 25 and 35 with no evidence of a cause of death on the bones. The strong lower jaw with the complete set of teeth has the typical Neanderthal gap behind the molars. At 1.70 m, the dead man was taller than the average European Neanderthal. Kebara 2 is similar to skeletons from Wadi Amud. In the Amud Cave there , there were also the remains of Neanderthals who are around 40,000 to 50,000 years old, including the remains of a ten-month-old child. An approximately 25-year-old man with the unusual height of 1.80 m and a skull capacity of 1740 cm³ was also excavated there.

About 25,000 artifacts of the Aurignacien and Moustérien were found in the four meter thick cave deposits . The oldest levels yielded thousands of animal bones, mainly from gazelles and red deer. On the partially burned bones, there were cuts from stone tools . The middle layers contained Levallois stone artifacts and fireplaces. On top were Epi-Paleolithic relics of Natufia .

Since there were no Neanderthals in Africa, but there were in Europe, West and Central Asia, the question arose where this Neanderthal population came from. After Ofer Bar-Yosef and Bernard Vandermeersch, the Kebara Neanderthals must have come from Europe. The reason for the migration could be the glacial climate between 115,000 and 65,000 BC. That drove European Neanderthals to the Middle East, where they met anatomically modern humans (Homo sapiens) . The artifacts from Kebara resemble stone tools from the Qafzeh Cave in Israel. However, those buried there are clearly not Neanderthals. Why populations belonging to different species had the same culture remains unclear.

The first fossils of modern man outside Africa were excavated from 1931 in Skhul , a cave near Haifa in the Carmel Mountains , and shortly afterwards in Qafzeh near Nazareth . The oldest of them can be dated to an age of 110,000 years; In the period between 80,000 and 50,000 years, evidence of people in these sites dries up again. This is accompanied by a drop in temperature of around 10 ° C, which occurred around 80,000 years ago in the Mediterranean region. After this first advance from Africa, the people here either simply died out or migrated back to Africa. In some cases they have been replaced by Neanderthals. One possible explanation, anthropologist Stanley Ambrose's Toba catastrophe theory , was proposed in 1998.

The oldest, albeit initially controversial, figurine is now the 230,000-year-old depiction of a woman found in Benekhat Ram in the Golan region. The schematized representation of women, slightly processed from a suitable stone, was even considered the oldest work of art in the world. Only with a stone carving from the Ha-Yonim cave did the depiction of a horse-like animal appear in a stone slab around 30,000 years ago.

In the Carmel Mountains near el-Tabun and Mugharet es-Skhul (children's cave), remains of Neanderthals and modern humans were found. A Neanderthal woman, known as Tabun I , is considered the most important find. The Tahun site was repeatedly visited over a period of approximately 600,000 years.

After more than 80 years of debates, in which in 1939 even a separate Palaeoanthropus palestinus was postulated, Skhul is mainly considered to be the burial place of the archaic Homo sapiens , who lived in the Carmel Mountains at the same time or alternately with Neanderthals; however, this species allocation is still controversial. The best preserved finds, however, which can only be dated to a very approximate 100,000 years, are Skhul I and Skhul V , whereby Skhul I is the roof of a child's skull, without facial bones, with only partially preserved lower jaw (partially dentate, molar M1 not yet erupted), in Skhul V around a largely completely preserved skull of an older adult with completely preserved, clearly chewed upper teeth and a strongly fragmented lower jaw. An almost completely preserved skeleton of a presumably male adult with a heavily fragmented skull, incomplete facial bones and an almost completely dentate lower jaw is known as Skhul IV , plus there are further skeletal remains that can be assigned to seven individuals, including that of a 50-year-old man ( Skhul I to X in total ). The site is of great importance not only because of the human remains, but also because of the pierced shells that were found there, which apparently belonged to a kind of jewelry or amulet that had a symbolic meaning.

When modern people migrated towards the Levant (“Out of Africa”) there were apparently two high points, namely 130,000 and 80,000 years ago. The two processes were separated from each other by a drastic climate change. Occasionally, a distinction is made between Out of Africa 2a and Out of Africa 2b , whereby the first emigrants may have been defeated in the food competition with the Neanderthals (or failed for other reasons), while the second emigration succeeded.

In 2005 seven teeth from the Tabun Cave were examined and most likely assigned to the Neanderthal. They could have lived there 90,000 years ago. Another Neanderthal find (C1) from Tabun was dated 122,000 years ago in 2000.

Genetic studies also suggest that there was a mixture between Neanderthals and anatomically modern humans. In any case, the settlement history is much more complex than long assumed.

The most significant difference between the Old and Middle Paleolithic with a view to the lithic industries is that the number of large cutting tools and retouched scratches and scrapers declined and the products of the Levallois technique predominated. In this way, large quantities of burins , blades and cuts could be produced. In contrast to the early Paleolithic, regional differentiations can now be recognized. In the Levant, the leaf-shaped hand ax (foliate biface) and stalked points (tanged points), as they appeared in neighboring Africa 100,000 before today, are missing . In contrast to Western Eurasia, the emphasis on heavily retouched kernels is also missing .

Upper Paleolithic (47,000 - 22,000 before today)

In the early Upper Palaeolithic, around 45,000 to 28,000 before today, the Neanderthals disappeared from Europe and West Asia, and Homo sapiens remained as the only representative of the Homo genus. The most recent phase of the European Upper Palaeolithic corresponds roughly to the Epipalaeolithic in the Levant (28,000 / 25,000 to 11,000 / 8,000 before today). This term is used for the regions that were not or only slightly influenced by the change between the ice ages with mighty ice sheets and warmer interglacials. Where the Upper Paleolithic is dated to around 47,000 to 22,000 before today, this change had the effect of a succession of rainy and dry periods. The phase of the last maximum of the glacier expansion also falls during this period. Lower temperatures and presumably heavier clouds created lakes such as Lake Lisan in the Jordan Valley, which stretched from the Sea of Galilee to what was once the southern end of the Dead Sea. It existed from about 70,000 to 12,000 BC. BC and extended over a length of 200 km; it had its highest water level between 26,000 and 24,000 BC. From 14,000 BC. In BC it sank by over 300 m within a millennium. Lakes called Playas were also created at higher altitudes.

The people continued to make a living from hunting big game, but smaller animals and fishing also played an increasingly important role, and the income from collecting continued to be added. With their new survival techniques, they were able to penetrate very challenging areas such as deserts or mountains for the first time. Complex composite tools, projectile weapons, but also protective housing contributed to this. Then there was the heat treatment of tools, the processing of clay, bone tools, as well as symbolic communication. In addition to body painting and jewelry, but also other cultural expressions that already appeared in the Middle Paleolithic, there were increasing signs of a kind of thin network between the groups. Raw material transport over several dozen kilometers, figurines of more or less great abstraction or notation systems served for communication and exchange with others. Improved lithic technology made it possible to process virtually the entire core into tools. These were mainly prismatic blade cores. Prismatic refers to the elongated blades that are used as cuts.

In the Egyptian mining site Taramsan I near Qena, which gave the epoch the name Taramsan , the transition to Upper Paleolithic blade manufacture can be seen in the same way as in the Negev desert at the Boker Tachtit site 43,000 years ago. It is unclear whether there were contacts between the south of Israel and the Upper Paleolithic Egypt, which seems to have been comparatively isolated.

The anatomically modern human is tangible around the Jordan Valley, more precisely in the Wadi Sabra near Petra. For the time about 50,000 to 18,000 years ago, the rich deposits allow extensive ecological investigations, which were started there in excavation campaigns from 2008 to 2011. They proved a more humid climate during the last Ice Age glaciation maximum. In addition to caves as archaeological sources, there are now open-air sites that also open up the Sinai Peninsula and parts of southern Israel.

The kebaria was long considered the last Upper Paleolithic culture of the Levant, but today it is considered to be the immediate predecessor of the Epipalaeolithic Natufia . Therefore, it has recently been counted among the Epipalaeolithic cultures.

Epipalaeolithic, from hunters and gatherers to food producers

Kebaran culture (20,000 / 18,000 - 12,000 BC)

The kebaran or Kebaran culture is the Epipalaeolithic assigned and thus the phase prior to the development of the producing life. It is therefore considered to be the immediate predecessor culture of the Epipalaeolithic Natufien . It was named after a site south of Haifa , the Kebara Cave . The members of the Kebaran culture were highly mobile hunters and gatherers who for a long time produced non-geometrical, but in the end phase geometrical, microlithic tools. But they also collected wild grain and made grinding tools to process the grain. The groups probably moved to higher areas in summer and spent the rainier winter in caves and under rock overhangs .

With the help of the tools, a strong regionalization can be determined; BC non-geometric, from this incision geometric microliths, i.e. trapezoidal and triangular tool parts. In the Negev, a variant of the kebaria developed, which is known as the Negev kebaria and is divided into the phases Harif and Helwan . Geometric and Negev kebaria at least partially overlap, with the Helwan phase being dated a little later. At the same time as this late phase, the Muschabia , a culture that was long believed to originate from North Africa , developed in the Mediterranean, but arid zones .

Finds of settlement sites are rare and rather small. They usually cover areas of 100 to 150 m². Volatile protective structures could be demonstrated. However, 20,000-year-old remains of settlements that are hardly inferior to those of the Natufien have recently been found at the eastern Jordanian site of Kharaneh IV . These were permanently used camps with permanent huts.

Despite minor traces of paleobotanism , the proportion of vegetable food seems to have increased. At the Syrian site of Ohalo II near the Sea of Galilee , around 90,000 remains of 40 plant species, mainly grain and edible fruits, were found. The oldest traces of collecting go back to around 21,000 BC. BC back. Wild barley was ground and baked, maybe wild wheat too. The animal feed included fallow deer in the northern Levant and gazelles in the southern. The Dorcas gazelle and the ibex were hunted in the drier areas, while the crop gazelle and Asiatic donkey , a horse species, were hunted in the eastern steppes. Aurochs , wild boar and hartebeest were less common , and there were turtles, birds, reptiles, hares and foxes. In cheaper areas with an abundant supply of food, mobility seems to have been lower, the distances to resources shorter and the population density higher.

In addition to the composite tools with microliths (which served sickles as cutting edges), bone tools, such as those found in the Kebara cave, were particularly highly developed. In addition to the Kebara Cave, the Hayonim Cave in western Galilee , which also contained deposits from the Moustéria , Aurignacia and the early and late Natufia, as well as the "geometric" sites of 'Uyun al-Hammam in Jordan and Neve David are among the important sites in Israel and Wadi-Sayakh in southern Sinai.

Natufien (12,000-10,200 / 8300 BC)

The natufien or natufium, named after the site discovered in 1928 in the Samarian hill country, has different timescales. Jacques Cauvin and François Raymond Valla put it between 12,500 and 10,000 BC. A, according to Tamar Yizraeli-Noy and others it does not end until around 8300 BC. The period between 9500 and 9000 BC. Chr. Is also called Khiamun after the place where el-Hiyam was found west of the Dead Sea.

Certain tools, such as sickle-shaped microliths, as well as large tools made of basalt and limestone, which are not suitable for transport, are characteristic of the Natufien. The older settlements of these hunters and gatherers, but also fishermen, who were settled on a small scale, were found in the lower elevations of Carmel, at the foot of the Hebron in the upper Jordan Valley, in Galilee (HaYonim terrace) and in the Judean mountains. In the course of the Protoneolithic, there was an accumulation of settlements between the central Euphrates, in the Jordan Depression and on the heights of the still forested Negev. These were settled hunters and gatherers who began to try their hand at growing grain. Long-distance trade relations existed as far as Egypt and Anatolia , which can be proven by means of fish remains from the Nile in the Natufien settlement Ein or Ain Mallaha (25 km north of the Sea of Galilee) and eastern Anatolian obsidian .

In 1970, Bar-Yosef postulated a division of the settlements into base camps (Ain Mallaha, Jericho , Hayonim Cave and Wadi Hammeh 27 ) and short-term areas. Other researchers assume that the base camps were only used in winter and that longer or shorter hunting trips took place in summer. In the Carmel Mountains, winter camps could be identified from the animal bones, but the associated summer camps were missing.

Settlements were under demolitions and in the open. The houses consisted of semicircular stone structures with structures made of rammed earth . In Ain Mallaha, in the oldest phase of settlement, there were sunken, semicircular houses made of limestone dry stone walls, rarely walls that were built with the help of a reddish limestone mortar. The floors are flat or slightly concave (house 131) and consist of compacted soil. The houses have central hearths, the roofs were supported by posts. In Bab edh-Dhra, Jordan, on the Lisan Peninsula on the eastern edge of the Dead Sea , a building that could have been a kiln was uncovered . The villages were suitable for a maximum of 200 to 300 inhabitants.

A team of researchers led by the biologist Gordon Hillman studied food residues from Abu Hureyra for 27 years and found in 2001 that there was already 11,000 BC. Grain was grown but not yet domesticated . The wild barley was harvested with Silex sickles . Mortars and grinding stones were in use; the latter testify to the processing of (wild) grain.

In both Ain Mallaha and Wadi Hammeh 27, the gazelle predominated among the animal bones. In Wadi Hammeh 27, however, the stork ( Ciconia ciconia ) and ducks were also hunted. From chamber III of El Wad lie the bones of wild cattle ( Bos primigenius ), wild goat ( Capra aegagrus ), red deer ( Cervus elaphus ), fallow deer ( Dama mesopotamica ), roe deer ( Capreolus capreolus ), Edmigazelle ( Gazella gazella ), wild boar ( Sus scrofa ), donkey ( Equus hemionus ) and wild horse ( Equus caballus ). Compared to the previous periods, more and more young animals were killed in the gazelles. Carnivores such as red fox ( Vulpes vulpes ), reed cat ( Felis chaus ), badger ( Meles meles ), stone marten ( Martes foina ) and tiger kilt ( Vormela peregusna ) were also hunted. The proportion of small animals such as turtles, hares and various species of birds, especially partridges , also increased significantly. At some sites it was over 50%. Hawks were mainly captured for their feathers. Whether in the Natufia bow and arrow, which in some areas around 8500 BC. Appeared, were in use, could so far only be made probable. In any case, weapons and tools were carried in bags, as a 14,000 year old find from Wadi Hammeh 27 shows.

Six graves were found on the Hayonim Terrace in northern Israel, which contained single and multiple burials. One grave contained the bones of a human and a dog (it is the oldest common burial of its kind), as well as turtle shells and the horned cones of gazelles. In the Natufien, the dead were usually buried in a contracted position, and occasionally the skulls were buried separately. In a site in Carmel, pierced mortars were discovered that may have been used to offer libations or to mark the graves. A tomb covered with a stone slab was found in Mallaha; this can be seen as the predecessor of the later dolmens . A little more than one in ten jewelry was added.

The upper layers of the Kebara Cave have been dated 11,000 to 12,000 years ago. A communal grave housed the skeletal remains of eleven children and six adults. Evidence of violence was found in all adults; a grown man had fragments of stone in his spine, apparently he had not survived the injury.

In the approximately 100 m² Hilazon Tachtit cave , 14 km from the Mediterranean coast in western Galilee on the Hilazon, at least 28 burials were discovered, with the exception of two in communal graves. Dated to around 10,000 BC. The remains of an approximately 45 year old and 1.50 m tall woman were found in a single grave, who probably dragged a leg during her lifetime. The grave consists of an oval hollow carved into the hard rock, the lower area of which is covered with clay. The walls are lined with limestone slabs. The woman was placed with her back to the wall, her legs crossed, and covered with ten larger stones. In addition, the grave was closed with a triangular limestone block. The grave goods in a nearby, similarly built hollow consisted of the remains of at least three aurochs, around 50 turtle shells, two marten skulls, wing bones of a golden eagle , wild boar bones , a cattle tail and a human foot and fragments of a basalt shell . A young adult was found in another solitary grave. The communal graves were only used for the first burial, skulls and large bones were later moved to an unknown, other final resting place. Of the 3,000 or so bones, 30% were gazelles and 45% turtles. Maybe it was a shaman; ritual celebrations can in any case be proven.

The previously mostly abstract art was supplemented by more realistic representations, which are considered the oldest pictorial documents of the Near East. They were found exclusively at Carmel and at a few sites in the Judah desert .

It is still unclear what role the climatic changes played in this momentous development. The last time it happened was in the Younger Dryas between 10,730 and 9700/9600 BC. To a strong global cooling. This in turn tore off sharply and culminated in a warm period within a few years. In the Levant, which was not affected by glaciation, there was a significant decrease in precipitation. In the Negev there was a revival of extensive collecting activities (Kharifien), while in the north gazelle hunting increased again (late Natufien).

In the areas bordering on the most important resource of the bourgeois, namely the migration routes of the gazelles, chains of more or less agreed local territories must have existed. Perhaps this led to a cultural control of the holdings in the long term. Studies of the visibility of burial sites in comparison to the settlements also indicate that the burial sites are to be understood as a claim to the surrounding, visible land at the latest from the Chalcolithic era .

Khiamien (10,200 - 8800 BC)

The Khiamien got its name after the El Khiam site at Wadi Khureitun near the Dead Sea, where excavations were first carried out in the early 1930s. The area in which artefacts of this culture were found extends from Sinai, with the site of Abu Madi, which is located east of the Catherine's Monastery , over Jordan (Azraq) to the Euphrates (Mureybet). In contrast to the Natufien, houses were now built at ground level, while half of them were previously below ground level. Key artifacts are the Khiamien blades.

Abu Madi was founded between 9750 and 7760 BC. BC, and thus mainly to the late Khiamien. The blades there differed, however, so that they were referred to as Abu Madi blades. Possibly they were an adaptation to the requirements of gazelle and wild goat hunting. At times the settlement was among the candidates for the oldest grain-producing way of life.

Neolithic

Pre-ceramic Neolithic

For a long time it was believed that the Neolithic, the ability to produce food, came about along with the manufacture of ceramics, especially the making of clay vessels. But at various sites it became apparent that neither the local stability nor the manufacture of ceramics are related to the development of "agriculture". In Jericho, for example, a 10 m thick layer was found that already contained air-dried adobe bricks and walls, as well as a tower made of stones. Not until 6000 BC The processing of clay, especially pottery, became generally accepted.

Pre-ceramic Neolithic A (9600-8800 BC), first "mega-sites"

That of Kathleen Kenyon based on the stratigraphy of Jericho section defined refers to a early Neolithic period 9500-8800 v. In the Levant and in the northern part of the Fertile Crescent , in which the manufacture of clay pots was not yet known. But there were human and animal figures made of clay, vessels were made from plaster of paris, stone and burnt lime, among other things. Round houses with terrazzo floors are typical.

A distinction is made between several regional forms, in Palestine the Sultania named after the Tell es-Sultan, i.e. Old Jericho (sometimes also the Khiamien, if one assumes a "long" Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA)). The lithic inventory includes the so-called El-Khiam and Aswad points as well as bifacial flint axes. The most important site in the south of Palestine is Jericho, which protrudes from the settlements, which were mostly between 0.2 and 0.5 ha in size, with an area of 4 ha. Khirbat Sheikh Ali and Beisamoun in the upper and middle Jordan Valley can also be counted among such sites, known as “mega-sites”.

Pre-ceramic Neolithic B (8800-7000 BC), first urbanization

In contrast to the round houses of the previous epoch, the houses were typically multi-room and rectangular. The lithic inventory includes, for example, Byblos and Helwan lace. In the primary production of the flint industries, a technological standardization of tool blanks emerged for the first time, the bidirectional core technologies. These not only saved raw material and represented a technically efficient solution for the mass production of size-standardized blades. They also promoted quality standardization in the end products. In addition, specialized, trained skills emerged that could lead to an emerging craft. Later bricklayers and lime burners were added as other early crafts.

In the early phase up to around 8300 BC The area in which settlements grew grain or vegetables was small. It was limited to the Jordan Valley or the Golan, as well as a few other favorable locations. Between 8300 and 7600 BC The more stationary settlement method spread to less favored areas. This could indicate a population increase, especially as a number of new settlements emerged. In addition, the focus of nutrition shifted from the gazelle to the goat, which opened up new areas of use. Around 7600 BC There was a drastic expansion of settlement activity, which apparently went hand in hand with migratory movements, possibly with greater population growth. The core families of the Middle PPNB apparently later became larger ancestral families or "lineage families". Most of the older settlements have been abandoned. Central places in the sense of a centralized settlement hierarchy do not seem to have existed yet. In this phase of around 500 years, “central” does not mean, as is usually the case, a hierarchy of settlements, but rather refers to settlements that were centers of their own local development patterns. The surpluses of individual settlements - for example, Basta produced blanks for blades, Ba'ja sandstone rings, es-Sifiya basalt, 'Ain Ghazal raw flint material - could have been the cause of defensive measures. On this basis, new social and spatial hierarchies would have arisen in the long term if these “mega-villages” had not been deprived of their development opportunities due to the degradation of their surroundings.

Animal and human figurines were made from clay and other materials, while vessels were made from plaster of paris or burnt lime. Above all, settlement burials are known, grave goods were common. The faces of the dead were partly modeled from plaster, as in Jericho or Nahal Hemar. The latter site is a cave with wooden artifacts and paving. Pearls were also found there, which probably belonged to special items of clothing. Decorated skulls, animal figurines and knives suggest rituals. According to the excavators, these finds belong to the oldest stratum (4) and are therefore predominantly in the period between 8210 and 7780 BC. To date. Periodization with a pre-ceramic Neolithic C (7000–6400 BC) following the PPNB is only common in Israel.

The last phase of the gazelle hunt ( Gazella gazella ) could be researched at the early and middle PPNB site Motza in the Judean Mountains around Jerusalem. The settlement hid tools made of gazelle bones, as they were in use in the previous Sultania, as well as other PPNA traditions were often continued; the finds from Motza go back to the early PPNB, not as long assumed only to the middle. Heluan and Jericho blades dominated.

When the dead were buried in Motza, there was no preferred orientation, even if they were buried strongly flexed. Three adult graves show evidence that the skull was later removed.

On an area of 40,000 m², the Atlit Yam site extended 200 to 400 m off the coast of Israel, where the Oren flows into the Mediterranean on the Carmel coast. Underwater archaeologists worked on the site at a depth of 8 to 12 meters, which dates from between 6900 and 6300 BC. Was dated. At that time the coastline was about a kilometer to the west. The settlement, which is the oldest evidence of a village inhabited by farmers and fishermen, may have fallen victim to a tsunami . This was triggered by the Atna. But it could also have been given up due to the salinisation of the well water. The archaeologists found rich, abandoned stocks of fish, which could indicate an escape. In addition to a row of rectangular houses and a well 5.5 m deep and 1.5 m in diameter, they discovered a stone semicircle around a (possible) spring. The seven megaliths were between one and 2.1 m high, the semicircle they formed had a diameter of 2.5 m. To the west of it there were rock slabs 0.7 to 1.2 m in length. Another structure, apparently for ritual purposes, was found in the form of three oval stones surrounded by furrows that represented schematic, anthropomorphic figures. Traces of the oldest case of tuberculosis were discovered on the corpses of a woman and a child . In addition, some men had severe damage to the ear area, which could indicate fatal seafood dives. The animal bones come from wild animals, but grain stocks have apparently been established.

An approximately 3 m high city wall, the purpose of which has not yet been clarified, was found two kilometers northwest of today's city center of Jericho in the 21 m high Tell es-Sultan . The settlement also contained the oldest, over 10,000 years old, 8.25 m high tower and probably defensive structures. At this point in time, around 3,000 residents are estimated for the 4-hectare settlement, which is often seen as the beginning of urbanization. Pottery and metal processing were still unknown. The economic basis of the “city” was the cultivation of emmer , barley and legumes , as well as livestock farming and hunting. After this phase the settlement was empty and did not emerge again until the end of the 7th millennium BC. BC, a settlement was established for the period between 7700 and 7220 BC. Chr. Not prove. Between 7220 and 6400 BC From the end of the Pre-Ceramic Neolithic B to the Pre-Ceramic Neolithic C, large rectangular adobe houses were inhabited. A new wall was created, which was destroyed and rebuilt several times. Numerous useful plants and traces of sheep breeding could be detected. In the homes of human skulls were near the entrances zweitbestattet . The faces of the skulls were partially reconstructed with plaster of paris and in some cases the eyes were replaced by shells. Burial places of this kind were found next to Jericho, where seven skulls were found, in Ain Ghazal and Beisamoun in the upper Jordan Valley, but also in Tell Ramad near Damascus .

Ceramic Neolithic (7000 - 6400 BC), pastoralization

The ceramic Neolithic of South Palestine shows completely different characteristics than the previous epoch. There was a pastoralization and the dissolution of previous ways of life. There was an adjustment in steppe economies, in which ecological factors were probably even more in the foreground. The reduced migration patterns of the epochs before the “mega-villages” have been resumed. There were also permanent settlements. Only after this phase did the stabilization, which provided the prerequisites for urban structures, take place.

The Yarmukien is the oldest ceramic culture in Israel, its most important place Sha'ar HaGolan in the Yarmuktal . In 1949 the site south of the Sea of Galilee was recognized as belonging to the Ceramic Neolithic. It extends over 20 hectares, which made the settlement the largest of its era, and was dated to 6400 to 6000 BC. Dated. There were large houses with inner courtyards measuring between 250 and 700 m². In terms of architectural history, they represent an important new development, because this type of house still exists in the Mediterranean region today. In addition, the settlement differed from the contemporary large settlements in Anatolia, for example, in that the houses were separated from one another by streets. The widest of these streets was 3 m long and covered with pebbles pressed into the clay. Another winding road was only three feet wide. A 4.15 m deep well provided drinking water. Obsidian blades , the basic material of which came from Anatolian volcanoes more than 700 km away, were also discovered. Sha'ar HaGolan is the first Neolithic site in Israel with extensive ceramic production. Over 300 artifacts interpreted as art objects were found, 70 of them figurines in a house alone. The figurines made of clay are much finer and more detailed, those made of stone are more abstract.

Another important site of this period is Megiddo , a tell or settlement mound around 30 km southeast of Haifa, which dates back to the 7th millennium, or Munhata, 11 km southwest of the Sea of Galilee. Yarmukian ceramics were also found in an excavation of only 100 m² near today's village of Hamadia, north of Bet She'an in the central Jordan Valley.

The early Neolithic of Egypt is fundamentally different from that of Israel in that it was not associated with tillage, as was the case in the entire Fertile Crescent. Merimde Beni Salama, about 45 km north-west of today's Cairo , was the original settlement of the Merimde culture , which can be classified in the beginning of the ceramic Neolithic. It seems to have Southwest Asian roots, which can indicate cultural contacts or migrations.

Within the Ceramic Neolithic, the Yarmukia was followed in some areas of Palestine by the Lodien, then the Wadi-Rabah culture , which some archaeologists at least partially attribute to the Chalcolithic. However, the relationship with the northern cultures is unclear due to the lack of excavations in Syria and Lebanon.

Chalcolithic (until 3300 BC), cities

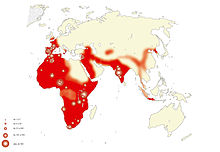

Concentration of the sites in the peripheral areas

The Chalcolithic or Copper Stone Age sites are concentrated on the Wadi banks in the Israeli periphery. Over a distance of around 110 km along the Beersheba and its continuation, the Besor , for example, more than 70 excavation sites from this era were found. The same applies to the Jordan Valley, where the central settlement Teleilat Ghassul was, which was the largest settlement in the region for around 1000 years with an area of around 20 hectares. At best it could be compared with the cities of Mesopotamia. Teleilat Ghassul was above the northeastern edge of the Dead Sea. There were spacious houses measuring 3.5 by 12 m, with the entrance on the long sides. Several houses that touched on the narrow sides formed a long chain, with several of these chains being built within the city. There was also a temple that contained numerous symbols that we could hardly understand, such as an octagonal star, an elephant head mask, colored, geometric figures or a bird.

Characteristic of the Chalcolithic are also extremely large pithoi , the largest storage jars ever made in Palestine. Typical is the rope-like handle, which is decorated with fingerprints. The spectrum of clay pots expanded; This created craters , vessels for mixing wine and water, but also the butter churn.

Climatic separation from Egypt (mid-6th to mid-5th millennium BC)

As a result of an arid phase in Palestine between the middle of the 6th and the middle of the 5th millennium BC. BC, from which no settlements can be proven for the area south of Lebanon, there were no longer any contacts with the Egyptian (middle) Merimde culture. The Badari culture there, the oldest known culture from Upper Egypt with a sedentary, soil-cultivating way of life, maintained contacts again. It is dated to around 4400 to 4000 BC. BC - perhaps it began as early as 5000 BC. A - and followed the Merimde culture . Although this culture had ceramic connections in Sudan, animal husbandry and type of agriculture point to Palestine.

End of Ghassulia (between 3500 and 3300 BC)

Ghassulia, named after the largest settlement, ended abruptly around 3500 to 3300 BC. It was probably a serious event, but traces of violence have not yet been proven.

Nachal Mischmar's treasure was found around 3500 BC. In a cave on the north side of the Nahal Mischmar. It consisted of 432 copper, bronze, ivory and stone objects: 240 club heads, around 100 sceptres, 5 crowns, horns, tools and weapons that were wrapped in a mat. The copper processed in it probably came from Armenia. Another copper treasure comprising around 800 objects was discovered near Kfar Monasch near Tel Aviv. It is unclear whether these treasure finds are related to the end of the Ghassul culture.

Bronze age

- Concordance of the Bronze Age cultures in the ancient Near East . The times are approximate, more precise in the individual articles. The Iron Age followed after the Bronze Age .

Early Bronze Age I (3300-3050 BC)

The delimitation of the early Bronze Age is not undisputed. Kathleen Kenyon could not assert herself with her naming of the first two of the three associated phases (Early Bronze Age Ia and Ib) in "early urban", even if it was precisely this cultural trait that characterized the cultures particularly clearly.

The break to the Chalcolithic era is not visible everywhere, because around a third of the sites continued earlier settlements. In addition to this continuity, an expansion into other parts of the country can be seen, such as the coastal plain, the central mountainous region, the Schefela , and the northern plains. Curvilinear, round, elliptical and apsidic structures emerged in the north, which were so different from the previous buildings that they suggested immigration.

At the same time, the supraregional relationships that were previously dominated by Mesopotamia increased significantly, in fact, they even became a hallmark of the epoch. The main focus was on Egypt, where Palestinian pottery appeared in the eastern Nile Delta.

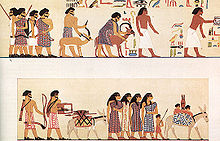

Contacts with Egypt in the Early Bronze Age II and III (from 4th millennium - 2300 BC)

Trade contacts with Egypt already existed at the time of the Maadi culture existing there in the north, i.e. before the first ruling unification of Egypt. So oil, wine and raisins came from Palestine. Flint tools also show a strong Middle Eastern influence (Canaanite blades). Significant amounts of copper were found in Maadi, probably from copper sites in Wadi Arabah in the southeast of the Sinai Peninsula.

The trade routes to Palestine were evidently secured by the Egyptian side at this time. There were Egyptians who worked with local materials in Egyptian technology. They apparently maintained a network of settlements.

The trigger for military conflicts was the attempt by Egypt, centralized under a pharaoh, to gain control over raw materials that were of great importance for the country's massive construction activity. Pharaoh Aha sent several expeditions to Lebanon and Palestine. The ruins of a bastion were found near En Besor in southwest Israel, which, based on ceramic and ivory finds, can be dated to the early 1st dynasty . Vessel fragments with Palestinian decorations were found in Aha's grave. Pharaoh Djer also ordered several expeditions to Sinai. In his tomb complex there were pieces of jewelry made of turquoise , which comes from Sinai. The victory of Dens over a foreign armed force was recorded on several ivory plaques, which is referred to in the inscriptions as the “First Suppression of the East”. The opponents were called Iuntiu ("arch people"). These were nomads from the Sinai Peninsula who regularly raided the royal turquoise mines. In an inscription from the Wadi Maghara (Sinai) Djoser appears killing a prisoner . Next to him stands a goddess, behind this stands the administrator of the Ankhen-en-iti desert , who carried out this expedition , according to the inscription . There are turquoise mines nearby , which were probably the target.

The contacts with Egypt were also of a peaceful nature. The Palermostein reports of the construction of ships and the arrival of 40 shiploads of cedar wood from Lebanon, from which ships were built and palace doors made. It is possible that the Sinai Peninsula with its copper and turquoise deposits was secured by military means under Sneferu. The only source for this is a rock inscription in Wadi Maghara on which Sneferu kills a Bedouin . By Graffiti is Cheops in Wadi Maghareh in Sinai - there as a protector of the mines - occupied. There is also evidence of trade relations between the Phoenician city of Byblos and Egypt. Trade relations with the Syrian region can be evidenced by a bowl from Ebla , which perhaps represented the trade hub between Egypt and Mesopotamia, and a seal cylinder from Byblos, both of which bear Chephren's name. The name of Menkaure or Mykerinos also appears on an object from Byblos. Expeditions to Lebanon have already been carried out under Userkaf.

Under Sahure , the only documented campaign of his reign was directed against Bedouins on Sinai, which the king reported on a large relief. The trade relations in this region are underlined by a relief in the mortuary temple of the Sahure pyramid, on which ships are depicted, whose crews are Syrians. An alabaster bowl with the name Neferirkares was found in Byblos .

Several rock inscriptions tell of the usual expeditions to the turquoise mines in Wadi Maghara , and an alabaster vessel found in Byblos with the mention of a Sedfest of the Djedkare documents trade contacts there. A war campaign to the Middle East is evidenced by a pictorial representation in the grave of Inti in Deschascha on the edge of the Fayyum. The 6th Dynasty lost its influence after campaigns against Libya, Nubia and Palestine.

The unification of the empire and thus the Middle Kingdom (2055 - 1650 BC) will have been completed around Mentuhotep's 39th year of reign. It was also possible to regain some influence outside of Egypt, as in Lebanon. But even Amenemhet I felt compelled to have walls built on the eastern edge of the delta to protect against Asian invasions. Sesostris I son Amenemhet II is best known for an annals stone found in Memphis, on which campaigns to Palestine are mentioned. Under his successor Sesostris II , so-called Genut, a kind of diary, among them the most important one found in Memphis, show that there were frequent conflicts and contracts with "Asians" (Aamu), as Herodotus (Historien 2106) noted. Byblos and the northern Syrian town of Tunip appear as trading partners, other cities as opponents of the war, of which allegedly they were taken prisoner in 1554. These high numbers could explain why so many Asian slaves lived in Egyptian houses in later times.

Under Sesostris III. As Herodotus and Manetho report, there were numerous campaigns. These undertakings are poorly documented. However, only one campaign to Asia appears in the sources.

Urbanization in the Early Bronze Age II and III (until 2300 BC)

The existence of numerous fortified settlements is likely to be closely related to these battles that flared up again and again. So Dan , Hazor , Qadesh in Galilee, Beth Yerah (Khirbet Kerak), Bet She'an and Megiddo in the north, Jericho, Lachish and Tell el-Hesi in the south were excavated. In addition, more than 260 settlements from this era are known in Western Palestine. 20 of them measured more than 5 hectares, Beth Yerah 22 hectares, Yarmuth 16, Tell el-Hesi 10 hectares, as well as Ai and Tel Arad . Mazar estimated that the total area of the urban settlements was 600 hectares, on which he assumed 150,000 inhabitants. They were concentrated in Galilee, Samaria, Judah, which is what characterizes the Early Bronze Age I. There were also large settlements in Transjordan, such as Bab edh-Dhra '.

Early Bronze Age II settlements were found in the Negev and the southern Sinai Peninsula. More than 50 such settlements were found in the vicinity of the later St. Catherine's Monastery alone. The settlements of the epoch had mighty fortifications, many of them were surrounded by 3 or 4 m thick walls, covered by horseshoe-shaped towers. In the later Bronze Age sections II and III, the walls were further reinforced, some of them were 7 or 8 m thick. In addition, the areas in front of the walls were protected by steep slopes; elongated rectangular towers appeared at the weaker points of the fortifications. City gates also appeared, such as in Tell el-Far'ah in the north or in Beth Yerah, Ai or Arad.

Large temples like those in Megiddo were built. Its three temples measured 17 by 18 m with outer walls up to 80 cm thick. The systems had open porches with two columns, and a corridor led into a large interior space measuring 14 by 9 m. A deity stood in a raised place, with each temple dedicated to the worship of a different one.

Beth Yerah was able to acquire enormous supplies, as the city had a storage facility with an area of 30 by 40 m. The outer walls were 10 m thick and nine 8 m thick silos were sunk there. Assuming that the building was 7 m high, 1400 to 1700 tons of wheat or other grain could be stored here. With perhaps 4,000 to 5,000 inhabitants, the city could probably trade in grain or at least store it for a long time.

Pastoralization in the Early Bronze Age IV and Middle Bronze Age I (2300/2250 - 2000 BC)

At the end of the Early Bronze Age II and III there was a breakdown in urban culture and the dominance of pasture farming. Egypt saw a similar decline in the 7th to 11th dynasties. It was only with the Middle Bronze Age II after 2000 BC. Around the same time as the Middle Kingdom in Egypt. At the same time a written tradition began.

Due to the lack of settlements, cemeteries are the most important sites for the typical ceramics of the time, but also caves. There are three types of cemeteries: shaft graves in western Palestine (they are the most common form), tumuli-covered dolmens in the Golan Heights and Upper Galilee, and ground-level tumuli (cairns) in the central Negev region. The shaft graves reached, for example in Jericho, depths of up to 6 m. The tumuli in the Negev emerged within the settlements. The deceased was buried in the inner cell, although grave goods were supposed to accompany him in a life beyond. Probably the dead were only buried here temporarily until the bones could be buried separately.

The cultural rift, it was believed, stems from an invasion by semi-nomadic, Semitic tribes, the Amurru , but Indo-European groups or inland nomads who filled the power vacuum after the collapse of urban culture were also blamed.

An important source for this period comes from Egypt. It is the story of Sinuhe , a probably fictional tale by an Egyptian who lived in Palestine and returned to his homeland in old age. In addition to the prohibition texts, it is the most important Egyptian source on Palestine in the early 2nd millennium. After the collapse of the urban centers, city-states or permanent settlements had emerged again, but the way of life of migrant grazing continued to exist. As a model, one might think of tribes next to cities; H. a juxtaposition of nomadic and urban forms of life and rule. At least some of the Amurites found themselves in the process of settling down and urbanization.

Sinuhe lived between nomads and urban rulers of defined areas. Byblos was a city-state of importance, but the outlawing texts also speak of the tribe of Byblos. Apart from Byblos, the author of the Sinuhe tale does not mention any cities, although the urban culture was just beginning to flourish. Ludwig Morenz assumes that the contrast between Egypt and Palestine was thereby brought out even more, thus emphasizing the foreign.

For the first time the term Ḥq3-ḫ3swt (“ruler of foreign lands”) appears in the Sinuhe story (Sinuhe B98), which is commonly called Hyksos . At the time of the Middle Kingdom, this term stood for a specific group in the population of Palestine. Later it meant kings of Asian origin who lived in Egypt from around 1650 to 1542 BC. Ruled. According to Ludwig Morenz, the "rulers of foreign countries" in the Sinuhe story are established rulers who differed from the wandering nomads at the time when they settled in the Palestinian region. With the figure of Amunenschi, the prince of Oberretjenu, a non-Egyptian is shown primarily as a ruler for the first time in Egyptian literature. The author thus replaces the usual ethical generalization of the foreign as a general negative connotation . By speaking Egyptian, he is even included in the Egyptian world of meaning.

literature

Overview works

- Daniel T. Potts (Ed.): A Companion to the Archeology of the Ancient Near East , John Wiley & Sons, 2012.

- Nigel Goring-Morris, E. Hovers, A. Belfer-Cohen: The Dynamics of Pleistocene and Early Holocene Settlement Patterns in the Levant: An Overview , in: John J. Shea , Daniel E. Lieberman (Eds.): Transitions in Prehistory . Essays in Honor of Ofer Bar-Yosef , Oxbow Books, 2009.

- Gösta Werner Ahlström, Gary Orin Rollefson, Diana Vikander Edelman: The History of Ancient Palestine from the Palaeolithic Period to Alexander's Conquest , JSOT Press, 1993 (heavily outdated for the oldest history)

- John J. Shea : Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East. A Guide , Cambridge University Press, 2013.

- Elena AA Garcea: South-Eastern Mediterranean Peoples between 130,000 and 10,000 Years Ago , Oxbow Books, 2010.

Paleolithic

- The Acheulian Site of Gesher Benot Ya'aqov , Vol. 1: Naama Goren-Inbar, Ella Werker, Craig S. Feibel: Wood assemblage , Springer 2002, Vol. 2: Nira Alperson-Afil, Naama Goren-Inbar: Ancient flames and controlled use of fire , Springer, 2010.

- Michael Chazan, Liora Kolska Horwitz: Holon. A Lower Paleolithic Site in Israel , Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnology, Harvard University, 2007.

- Donald O. Henry (Ed.): Neanderthals in the Levant. Behavioral Organization and the Beginnings of Human Modernity , Continuum International Publishing Group, New York 2003. (Focus on the Jordanian Tor Faraj)

- Carlos E. Cordova, April Nowell, Michael Bisson, Christopher JH Ames, James Pokines, Melanie Chang, Maysoon al-Nahar: Interglacial and glacial desert refugia and the Middle Paleolithic of the Azraq Oasis, Jordan , in: Quaternary International 300 (2013) 94-110.

Epipalaeolithic, Neolithic

- A. Nigel Goring-Morris, Anna Belfer-Cohen: A Roof over One's Head. Developments in Near Eastern Residential Architecture Across the Epipalaeolithic-Neolithic Transition , in: Jean-Pierre Bocquet-Appel, ʻOfer Bar-Yosef: The Neolithic Demographic Transition and its Consequences , Springer 2008, pp. 239–286.

- Lisa A. Maher, Tobias Richter, Jay T. Stock: The Pre-Natufian Epipaleolithic: Long-term Behavioral Trends in the Levant , in: Evolutionary Anthropology 21,2 (2012) 69–81.

- Ofer Bar-Yosef : The Natufian Culture in the Levant. Threshold to the Origins of Agriculture , in: Evolutionary Anthropology 6 (1999) 159-177.

- Marion Benz: The Neolithization in the Near East. Theories, archaeological data and an ethnological model , Studies in Early Near Eastern Production, Subsistence and Environment 7. ex oriente, Berlin 2008².

- Tania Hardy-Smith, Phillip C. Edwards: The garbage crisis in prehistory: artefact discard patterns at the Early Natufian site of Wadi Hammeh 27 and the origins of household refuse disposal strategies , in: Journal of Anthropological Archeology 23 (2004) 253-289 .

- Gordon Hillman, Robert Hedges, Andrew Moore, Susan Colledge, Paul Pettitt : New evidence for Late Glacial cereal cultivation at Abu Hureyra on the Euphrates , in: The Holocene 11 (2001) 383-393.

- Natalie D. Munro: Zooarchaeological Measures of Hunting Pressure and Occupation Intensity in the Natufian. Implications for Agricultural Origins , in: Current Anthropology . Supplement 45 (2004), p. 5.

- Cheryl A. Makarewicz: The Younger Dryas and Hunter-Gatherer Transitions to Food Production in the Near East , in: Metin I Eren (Ed.): Hunter-Gatherer Behavior. Human Response during the Younger Dryas , Left Coast Press 2012, pp. 195-230.

- Yosef Garfinkel , Doron Dag, Daniella Bar-Yosef Mayer: Neolithic Ashkelon , Institute of Archeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, 2008.

- Ian Kujit: Demography and Storage Systems During the Southern Levantine Neolithic Demographic Transition , in: Jean-Pierre Bocquet-Appel, ʻOfer Bar-Yosef: The Neolithic Demographic Transition and its Consequences , Springer 2008, pp. 287-313.

Bronze age

- Walter C. Kaiser Jr .: A History of Israel. From the Bronze Age to the Jewish Wars , Broadman and Holman, 1998.

- Israel Finkelstein : The Archeology of the Israelite Settlement , Jerusalem 1988.

- Robert G. Hoyland: Arabia and the Arabs. From the Bronze Age to the Coming of Islam , Routledge, London / New York 2001.

- Lester L. Grabbe (ed.): Israel in Transition 2. From Late Bronze II to Iron IIA (c. 1250–850 BCE): The Texts , New York-London 2010 (from Samuel).

- Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman: No Trumpets Before Jericho. The archaeological truth about the Bible , Beck, Munich 2006.

- Markus Witte, Johannes F. Diehl (ed.): Israelites and Phoenicians. Their relationships as reflected in the archeology and literature of the Old Testament and its environment , Friborg and Göttingen 2008.

- Assaf Yasur-Landau: The Philistines and Aegean Migration at the End of the Late Bronze Age , Cambridge University Press 2010.

Web links

- Dawn of Civilization , permanent exhibition at the Israel Museum

- Archaeological Survey of Israel

- Project website of the Sapienza , Rome

- Ancient Jericho (Tell Sultan) , 1978

Remarks

- ^ Friedemann Schrenk, Stephanie Müller: Die Neandertaler , CH Beck, Munich 2005, p. 42.

- ↑ Carl Zimmer: Where do we come from? The origins of man , Spektrum Akademischer Verlag, 2006, p. 90.

- ↑ Aylwyn Scally et al .: Revising the human mutation rate: implications for understanding human evolution , in: Nature Reviews Genetics. Volume 13, 2012, pp. 745-753.

- ↑ Ewen Callaway: Studies slow the human DNA clock , in: Nature 489, No. 7416, 2012, pp. 343-344, doi: 10.1038 / 489343a .

- ↑ Kevin E. Langergraber et al .: Generation times in wild chimpanzees and gorillas suggest earlier divergence times in great ape and human evolution , in: PNAS 109, No. 39, 2012, pp. 15716–15721, doi: 10.1073 / pnas. 1211740109 .

- ↑ Chris Stringer, Jean-Jacques Hublin: New age estimates for the Swanscombe hominid, and their significance for human evolution , in: Journal of Human Evolution 37 (1999) 873-877, doi: 10.1006 / jhev.1999.0367 .

- ↑ Jean-Jacques Hublin: The origin of Neandertals , in: PNAS 106, No. 38, 2009, pp. 16022-16027, doi: 10.1073 / pnas.0904119106 .

- ↑ Milla -Y. Ohel: Origine et répartition du silex et des industries sur le plateau de Yiron (Israel) , in: Bulletin de la société préhistorique française, 80.6 (1983) 179-183.

- ^ John J. Shea: Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East. A Guide , Cambridge University Press 2013, p. 73.

- ^ The oldest human groups in the Levant . Cat.inist.fr. September 13, 2004. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ John J. Shea: Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East. A Guide , Cambridge University Press 2013, p. 74.

- ↑ Sabine Gaudzinski-Windheuser : Subsistence strategies of early Pleistocene hominids in Eurasia. Taphonomic observations of fauna at the sites of the 'Ubeidiya Formation (Israel) , monographs of the Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz 61, Habelt, Mainz / Bonn 2005 ( online ).

- ↑ Sabine Gaudzinski-Windheuser: Subsistence strategies of early Pleistocene hominids in Eurasia. Taphonomic observations of fauna at the sites of the 'Ubeidiya Formation (Israel) , Habelt, Mainz / Bonn 2005, p. 12.

- ^ Matt Cartmill, Fred H. Smith: The Human Lineage , John Wiley & Sons 2009, pp. 320f.

- ^ John Noble Wilford: Excavation Sites Show Distinct Living Areas Early in Stone Age , in: The New York Times, December 21, 2009.

- ↑ Naama Goren-Inbar et al .: Evidence of Hominin Control of Fire at Gesher Benot Ya'aqov, Israel , in: Science, 304, no. 5671 (2004) 725-727.

- ↑ J. Haidal et al .: Neanderthal infant from the burial cave Dederiyeh in Syria. Paléorient 21 (1995) 77-86 ; Lynne Schepartz, Antiquity, Sep 2004, review of Takeru Akazawa, Sultan Muhesen (ed.), Neanderthal burials. Excavations of the Dederiyeh Cave, Afrin, Syria , Auckland, 2003 ( Memento of July 8, 2012 in the web archive archive.today ).

- ↑ Cf. Burton MacDonald: The Wadi El Ḥasā Archaeological Survey, 1979–1983, West-Central Jordan , Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1988. ( Google Books )

- ↑ Ann Gibbons: The Species Problem. A New View of the Birth of Homo sapiens , in: Science 331 (2011) p. 394, doi: 10.1126 / science.331.6016.392

- ↑ L. Meignen: Les origines de l'Homme moderne au Proche Orient , in: Bulletin du Center de recherche français à Jérusalem 1 (1997) 38-42. For the cave as a whole cf. L. Meignen, Ofer Bar-Yosef , M. Stiner, S. Kuhn, P. Goldberg, S. Weiner: Apport des analyzes minéralogiques (en spectrométrie infra-rouge Transformation de Fourier) à l'interprétation des structures anthropiques: les concentrations osseuses dans les niveaux moustériens des grottes de Kébara et Hayonim (Israël) , in: MP Coumont, C. Thiébaut & A. Averbouh (eds.): Mise en commun des approches en taphonomie / Sharing taphonomic approaches , Supplément 3, publication de la table -ronde organisée pour le XVIème congrès international de l'UISPP, Lisbon 2006; then L. Meignen, P. Goldberg, RM Albert, O. Bar-Yosef: Structures de combustion, choix des combustibles et degré de mobilité des groupes dans le Paléolithique moyen du Proche-Orient: examples des grottes de Kébara et d'Hayonim ( Israël) , in I. Théry-Parisot, S. Costamagno, A. Henry (eds.): Gestion des combustibles au Paléolithique et Mésolithique: nouveaux outils, nouvelles interprétations / Fuel management during the Paleolithic and Mesolithic period: new tools, new interpretations , 1914 (2009) 101–118 and N. Mercier, N., H. Valladas, L. Froget, JL Joron, JL Reyss, S. Weiner, P. Goldberg, L. Meignen, O. Bar-Yosef, S. Kuhn, M. Stiner, A. Belfer-Cohen, AM Tillier, B. Arensburg, B. Vandermeersch: Hayonim Cave: a TL-based chronology of a Levantine Mousterian sequence , in: Journal of Archeological Science, 34/7 (2007) 1064-1077.

- ↑ R. Yeshurun, G. Bar-Oz, M. Weinstein-Evron: Modern hunting behavior in the early Middle Paleolithic: faunal remains from Misliya Cave, Mount Carmel, Israel , in: Journal of human evolution 53.6 (2007) 656 -677.

- ↑ Mary C. Stiner , Ran Barkaib, Avi Gopher: Cooperative hunting and meat sharing 400-200 kya at Qesem Cave, Israel , in: PNAS 106,32 (2013) 13207-13212.

- ↑ Named after Gottfried Zumoffen .

- ↑ Avi Gopher, Ran Barkai, Ron Shimelmitz, Muhamad Khalaily, Cristina Lemorini, Israel Hershkovitz, Mary Steiner: Qesem Cave: An Amudian Site in Central Israel , in: Journal of The Israel Prehistoric Society 35 (2005) 69-92. See R. Barkai, C. Lemorini, R. Shimelmitz, Z. Lev, MC Stiner, A. Gopher: A blade for all seasons? Making and using Amudian blades at Qesem Cave, Israel , in: Human Evolution 24 (2009) 57-75.

- ↑ ( How many Neanderthals are in us? Quarks & Co, December 7, 2010 ).

- ↑ A picture of Amud 7 can be found here ( Memento from July 16, 2011 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ A picture of Amud 1 can be found here ( Memento from April 24, 2011 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Spencer Wells: The Journey of Man. A Genetic Odyssey , Penguin, London 2003, p. 98.

- ↑ Population Bottlenecks and Volcanic Winter , in: Journal of Human Evolution 35 (1998) 115–118 or David Whitehouse: Humans came 'close to extinction' , in: BBC News, September 8, 1998.

- ↑ Silvia Schroer, Othmar Keel: The iconography of Palestine / Israel and the ancient Orient. A history of religion in pictures , Academia Press Friborg / Paulusverlag Freiburg Switzerland, Freiburg i. Ue. 2005, p. 37.

- ^ Timeline in the Understanding of Neanderthals . Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- ↑ A picture of Tabun 1 can be found here ( Memento from August 16, 2013 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ From 'small, dark and alive' to 'cripplingly shy': Dorothy Garrod as the first woman professor at Cambridge . Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- ↑ Excavations and Surveys (University of Haifa) ( Memento from October 27, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ A picture of Skhul V can be found here .

- ↑ Jeffrey H. Schwartz, Ian Tattersall (Ed.): The Human Fossil Record , Vol. 2: Craniodental Morphology of Genus Homo (Africa and Asia) , Wiley, 2003, pp. 358 ff. ( Google Books ).

- ↑ Shell chain as a status symbol. Our ancestors wore jewelry 100,000 years ago , heise de, June 28, 2006.

- ↑ Elena AA Garcea: Successes and failures of human dispersals from North Africa , in: Quaternary International 270 (2012) 119-128. On the trigger, see: Philip Van Peer: Did middle stone age moderns of sub-Saharan African descent trigger an upper paleolithic revolution in the lower nile valley? , in: Anthropologie 42,3 (2004) 215-225.

- ↑ Alfredo Coppa, Rainer Grün, Chris Stringer, Stephen Eggins, Rita Vargiu: Newly recognized Pleistocene human teeth from Tabun Cave, Israel , in: Journal of Human Evolution 49.3 (September 2005) 301-315 doi : 10.1016 / j.jhevol .2005.04.005 .

- ^ R. Grun, CB Stringer: Tabun revisted: revised ESR chronology and new ESR and U-series analyzes of dental material from Tabun C1 , in: Journal of Human Evolution 39 (2000) 601-612.

- ↑ Ewen Callaway: Neanderthal genome reveals interbreeding with humans , in: New Scientist, May 6, 2010.

- ↑ Robin Dennell , Michael D. Petraglia: The dispersal of Homo sapiens across southern Asia: how early, how often, how complex? , in: Quaternary Science Reviews 47 (July 2012) 15-22.

- ^ John Shea: Stone Tools in the Paleolithic and Neolithic Near East. A Guide , Cambridge University Press 2013, p. 114.

- ↑ David Neev, Kenneth Orris Emery: The Dead Sea. Depositional processes and environments of evaporites , ed. Ministry of Development Geological Survey of Israel 1967.

- ^ Amud , in: Encyclopedia Britannica, 2007.

- ↑ Manuel Bertrams, Jens Protze, Daniel Schyle, Nicole Klasen, Jürgen Richter, Frank Lehmkuhl: A Preliminary Model of Upper Pleistocene Landscape Evolution in the Wadi Sabra (Jordan) Based on Geoarchaeological Investigations , Landscape Archeology Conference 2012 - Berlin 2012.

- ^ Daniel T. Potts (Ed.): A Companion to the Archeology of the Ancient Near East , Wiley & Blackwell 2012, pp. 129f.

- ↑ This and the following according to DT Potts (ed.): A Companion to the Archeology of the Ancient Near East , Wiley & Blackwell 2012, pp. 129f.

- ^ Daniel Kaufmann: Excavations at the Geometric Kebaran Site of Neve David, Israel: A Preliminary Report , in: Quartär 37/38 (1987) 189-199; Ofer Bar-Yosef, A. Killbrew: Wadi-Sayakh - A Geometric Kebaran Site in Southern Sinai , in: Paleorient 10 (1984) 95-102 ( online ).

- ↑ Lisa A. Maher, Tobias Richter, Danielle Macdonald, Matthew D. Jones, Louise Martin, Jay T. Stock: Twenty Thousand-Year-Old Huts at a Hunter-Gatherer Settlement in Eastern Jordan , in: PLoS ONE 7.2 ( 2012): e31447, doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0031447 .

- ^ Ohalo II (Israel). Upper Paleolithic Site of Ohalo II , About.com - Archeology.

- ↑ Research pushes back history of crop development 10,000 years

- ↑ Emma Suzanne Humphrey: Hunting Specialization and the Broad Spectrum Revolution in the Early Epipalaeolithic: Gazelle Exploitation at Urkan e-Rubb IIa, Jordan Valley , PhD theses, Toronto 2012. ( online ); Jennifer R. Jones: Using gazelle dental cementum studies to explore seasonality and mobility patterns of the Early-Middle Epipalaeolithic Azraq Basin, Jordan , Quaternary International 252 (February 2012) 195-201.

- ↑ Jerome Murphy-O'Connor (Ed.): The Holy Land. The travel guide to over 200 sites with maps, plans, and photographs , Oxford University Press 2008, p. 448.