Lop Nor desert

The Lop Nor desert ( Chinese 罗布 沙漠 , Pinyin Luóbù Shāmò , Uighur لوپنوُﺭ چۆلى Lopnur Qɵli ) is an inland desert in the northwest of China . It is located in the eastern part of the Tarim Basin in the Uyghur Autonomous Region of Xinjiang and has a size of about 47,000 km². The Lop Nor desert stretches in the east to the city of Dunhuang in Gansu Province .

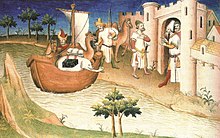

The Lop Nor is characterized as a sandy desert in the west and a salt desert in the east, the ground heats up to 80 ° C in summer. The desert had been along the rivers to Lake Lop Nor since about 2000 BC. Settled, of which large necropolises have been preserved. The Silk Road ran through the desert, so Marco Polo mentioned it in his travel reports. Today the desert is of economic importance for the mining of coal and the production of potash . A sanctuary for endangered wild camels has existed in the Lop Nor desert since 1999 .

Since 2006, trunk road S235 has crossed the Lop Nor desert from northeast to southwest, cutting through the former lake Lop Nor. It connects the city of Hami with the city of Ruoquiang .

About the name

Lop Nor is the name of the Tarim end lake, which has now dried up. The word for desert used in the respective language is added to the name of the desert . The name Lop Desert , used occasionally in the past , has not caught on.

Other spellings for Lop Nor are Lop Nur and Lob Nor . There is also no uniform spelling internationally.

The name Lop Nor comes from Mongolian and means “the lake in which many water sources converge” (English: the lake converging many water sources ), meaning: “catchment area for the inflow of different rivers” (English: catchment for the afflux of several rivers ). The name has been used since the Yuan Dynasty . The Mongolian word nuur means "lake".

Before the Yuan Dynasty, there were other names, for example "salt desert" or "peacock lake". The Han annals used the name forms P'u-ch'ang Hai (or Hu ), Lou-lan Hai (" Loulan Lake") and Yen-tse ("Salt Marsh"). The term Sea of Death is also used in translated Chinese texts today .

location

Lop Nor desert in China |

The desert is located in a sedimentary basin that was separated from the Taklamakan sedimentary basin by a tectonic shift in the Pliocene and sunk to the east. In the rift valley between the Taklamakan and the Lop Nor desert, the Tarim and Konqi rivers used to flow south until they dried up near Tikanlik in 1971. Road 218 from Korla to Qakilik runs along its riverbed . The desert is bounded by this road to the west, the Kuruk Tagh Mountains to the north , the Bai Shan Mountains to the east and the Aqikkol Valley and the Kumtag sand dunes to the south.

The western part of the desert is a sand desert, the eastern part a salt desert with yardangs . This salt desert is located in a depression and contains the lake basin of the Lop Nor salt lake , which has dried up since 1961 or 1962 , the last position of which can still be recognized by an ear-like spiral. In the south of the desert are the basins of the two dry freshwater lakes Karakoshun and Taiterma Lake .

During the above-ground nuclear weapons tests at the nearby Lop Nor nuclear weapons test site , radioactive fallout fell on the desert. As a result, supporters of the Uighur independence movement reported the increased incidence of mysterious illnesses in southwest Xinjiang. Government spokespersons denied that there were illnesses due to increased radioactivity .

climate

There is a fully arid climate in the Lop Nor desert . In summer, the ground temperatures are up to 80 ° C and the air temperatures up to 41 ° C due to the heat radiated from the ground. 50 ° C can be reached in the tent. The mean annual temperature is between 9 and 11 ° C, with the difference between the coldest and warmest month of the year being around 35 ° C. Due to the extreme drought and heat , no vegetation can exist inside the desert . This desert is one of the areas where desertification and anecumens exist. The maximum annual precipitation is 17.4 mm and the annual evaporation 2902 mm. According to data from 1964, 5 mm of precipitation falls from December 1 to February 28, and 5 mm from June 1 to August 31. When it rains, the water droplets evaporate in the hot, dry air before they reach the ground. This phenomenon is called "devil rain" or "umbrella" in Xinjiang.

The Kara Buran (black Buran) sandstorm can be traced back to the 3rd century. Its frequency and intensity have fluctuated greatly over the centuries. Since the year 1000 the frequency of sandstorms increased significantly, it increased from 1500 and in a special way from 1850. In 2000 the number of sandstorms 14 times as many as in 1950 was registered; one reason for this is the increasing desertification in western and northern China since 1949/1950. The sandstorms come mainly from April to October (as of 2006, previously: from February to July) from different directions, often from the southeast or northwest (previously: mainly from the northeast). Every year there are 70 to 80 days with a sandstorm and 200 to 250 days with dust (as of 2005).

Winters are cold and with rare snowfall. Caravans on the Middle Silk Road and expeditions of the 19th and 20th centuries took advantage of the cold months of December and January and took drinking water with them in the form of ice.

Emergence

In the last ice age, the Taklamakan and the Lop Nor desert were almost entirely covered by a glacial lake . This is evident from the drill cores taken in 2003 at the Lop Nor Environmental Science Drilling Project at a depth of 160–250 meters. According to Fang Xiaomin from the Institute of Earth Environment of the Chinese Academie of Sciences , they show that Lake Lop Nor was 1.8 to 2.8 million years ago a very deep and more than 20,000 km² freshwater lake that stretches over a long Period of constant heavy rain extended beyond the Lop Nor desert area into the Taklamakan desert area. In the drill cores, 60 meter long deposits of yellow indigo silt with a high gypsum content were found, which confirm that there was a freshwater lake of great depth, at the bottom of which there was a lack of oxygen. Finds of mussels in the drill cores show that the lake was also a freshwater lake in later times.

The surface of this lake was about 900 m . This can be recognized south and north of the Lop Nor desert by the steep and average 20 meter high lake terraces, which were cut out of the surrounding coast by the lake water and are 870 to 900 m high. Also in the Taklamakan there are references to this lake at an altitude of about 1000 m .

1.8 million years ago in the Pliocene in the eastern Tarim Basin , a tectonic displacement created the lower basin in which the Lop Nor desert is now located. There was formed around 780,000 BC. Through new tectonic subsidence at the end of the middle Pleistocene, the secondary lake basin Lop Nor emerged.

800,000 years ago the climate in the Tarim Basin changed; it got extremely dry. The glacial lake shrank. After the Taklamakan dried up, the Lop Nor lake basin became the destination of all the rivers in the Tarim basin, which formed their deltas there, supplied their end lakes Lop Nor and Karakoshun with water and deposited the salt carried along in the rivers in a huge salt pan . The outflow-free lake Lop Nor has existed continuously for over 20,000 years in changing size and location in the Lop-Nor basin, to which the arid to fully arid climate contributed, which did not change over a long period of time. The rivers in the deltas meandered and formed yardangs that remained as elongated islands between the different rivers.

Surface shape of the desert

Lop Nor lake basin

Since 1961 or 1962 the Lop Nor lake with its tributaries Konch-darja and Kum-darja has dried up. Since then, his dry lake basin has been the focus of scientific, economic and political interest.

The lake basin is 780 m high at the deepest point of the Tarim basin and is almost as big as Hesse with 21,000 km² . It measures 260 km from the southeast to the northwest and has a maximum width of 145 km. Over the millennia, its biological deposits accumulated a layer 1.50 m thick, in which pollen from aquatic plants was found, which shows that the Lop Nor has kept water for long periods of time and has been a biotope for aquatic plants.

The surface consists of alluvial calcareous and salty soil and is covered as a salt clay plain by a hard and sometimes highly broken salt crust, which makes the northeast of the salt desert almost impassable. The brown earth crust and the rock hard but thin white salt crust are deceptive; because a dangerous salt marsh is already half a meter below the surface.

John Hare saw the parched Lop Nor from the north in 1996 and described him as follows:

“The gray, hazy surface of the lake bed stretched to the horizon. To the east, a number of black lumps - probably small hills - seemed to loom over the horizon on a headland. In the west there were more blackish objects trembling, like horsemen in the rising warm air, but apart from these slightly ominous shapes, gray was the predominant color. Even the blue sky had disappeared behind the dust that the howling wind was now stirring up. "

The big ear

Satellite images show a spiral in the shape of a human auricle with concentric circles in the west of the lake basin . This big ear (English names: Big Ear , Large Ear ) was the target of extensive Chinese research until 2008.

It was found that the outer line of the great ear describes the contour line of 780 m above sea level and surrounds an area of 5,350 km². According to Xia Xuncheng and Zhao Yuanjie, the ring-shaped salt deposits on the coastlines of Lop Nor were formed within four to five years during the drying up of the lake and formed this spiral. The timing of dehydration is controversial. Xia Xuncheng and Zhao Yuanjie assumed in 2005 that the deposits in the big ear were formed in the early 1960s when Lop Nor dried up. Li Bao Guo1, Ma Li Chun and others assumed in 2008, after reinterpreting the aerial photographs from 1956, that the deposits had already formed between the end of the 1930s and the beginning of the 1940s during a drying out of Lop Nor.

The deposits are so hard that they cannot be broken with a hammer or ax. The Lop Nor filled the spiral at a height of three meters until it dried up and also extended to the north at a smaller width and depth.

Yardangs

The explorer Sven Hedin has Yardangs in 1903 in his book In the heart of Asia named and described, after he had visited the Lop Nor desert 1902nd The word Yardang ( Chinese 雅丹 , Pinyin Yardan or Yadan ) is derived from the Uighur word Yar , which can be translated as 'steep hill' or 'steep wall'. In the Lop Nor desert, the yardangs emerged as elongated islands in the deltas of earlier rivers that flowed towards Lake Lop Nor. On the upper platform of the yardangs there are often dead poplars, dead molluscs and dried up reeds. The yardangs run in different directions depending on their location, namely in the direction of flow of earlier rivers. Sandstorms also sanded them off in the direction of the prevailing storms. They consist of clay mineral , often mixed to loam , cover an area of around 3,100 km² and are under nature protection.

In 1985 Xia Xuncheng distinguished the following areas with yardangs in the Lop Nor desert:

A yardang group is located to the west and northwest of the Lop Nor lake basin and surrounds Loulan and the river bank of the Kum-darja. Xia Xuncheng suspected in 1982 that the upper platform of the 5.30 m high yardangs indicated the original height of the lake basin around 1919 and that the eroded areas between the yardangs were caused by the current of the inflowing water in Lake Lop Nor and through until 1959 Rain storms have been deepened. After the lake has dried up, the yardangs are also sanded down streamlined by the prevailing northeastern sandstorms. In 1996 , John Hare found the Yardangs northwest of Lake Lop Nor to be "a frightening tangle ten meters high, strange and wonderful eroded rock forms".

The Yardang group in Bailongdui ( Chinese 白龙 堆 , Pinyin bái lóng duī ) is located northeast of the Lop Nor lake basin. It has a size of 1,600 km² and is 80 km long from north to south and 20 km wide from west to east. The yardangs are usually ten to twenty meters high and two hundred to five hundred meters long. Most of them are covered with a thick crust of salt and shine silver in the sunlight. From a distance, according to the Chinese, they look like white dragons guarding access to Loulan as guardians of the Silk Road.

The Yardang Group in the Aqip Valley lies in four areas of the former Aqip River, the lower reaches of the Shule River in the east of the Lop Nor desert. Dunhuang Yardang Geopark The Dunhuang Yardang Geopark (敦煌 雅丹 国家 地质 公园) with the coordinates 40 ° 31'11 "N 93 ° 4'1" E) in Gansu Province near the eastern border of Xinjiang is 85 km away West Yumen Pass and 180 km northwest of Dunhuang City and is called "City of the Devil" or "Ghost Town" in China. They are two closely spaced yardang groups that extend about 25 km from east to west and about 8 km each from north to south. The yardangs are made of bright yellow to brown sandstone and rise out of the flat black desert. They are sometimes thousands of meters long, several dozen meters wide and several hundred meters separated from their neighbors by the black pebble soil on which no plants grow. Eerie noises arise in a storm; at dusk the wind creates a horrible howl, as if thousands of predators are haunted.

The mythical name "Dragon City " ( Chinese 龙城 , Pinyin lóng chéng ) describes an area with yardangs that cannot be precisely assigned geographically. In 1985, Xia Xuncheng referred the name "Dragon City" to the Yardang group in Bailongdui. The yardangs are different in height, length, width and shape. Its appearance evokes associations with the Chinese of a city with houses, towers, fortresses, boats, animals and people. During a storm, you can hear wind noises that are reminiscent of the noises of a city: for example, dogs barking, birds singing, bells, laughing and screaming children.

In an old Chinese text, the classic of the waters , there is an etiological legend that tries to fathom the origin of the "dragon city" with its yardangs :

“The dragon city is the residence of Giang Lai. He rules a great barbarian kingdom. One day the waters of Lop Nor rose and flooded the capital of this kingdom. The city's foundations are still intact. They are very extensive. If you start at the west gate at sunrise, you will only get to the east gate at sunset. A canal had been built under the steep slope of the town. Above it, the ever-blowing wind has piled up sand that gradually took the form of a kite looking west across the lake. Hence the name Dragon City. The territory of their rulers extends a thousand miles. It consists entirely of salt in a hard, solid state. The travelers passing through spread felts for their animals to lie on. If you dig in the ground, you come across blocks of salt the size of pillows, piled regularly on top of each other. In this area the air is hazy like rising fog or like fast moving clouds, so that one rarely sees the sun or the stars. There are only a few animals there, but many demons and ghostly beings. "

Fossils and flora

With the drying up of the Lop Nor and its tributaries, one of the oldest lakes on earth with its community of plants and animals has disappeared from the Lop Nor desert. Instead of the lake, only the significantly smaller salt-brine basin of the Lop Nur Sylvite Science and Technology Development Co. Ltd remains today. After all, the Lop Nor desert is an archive of the past that provides information about the rich flora and fauna of the past millennia and millions of years. When the Swedish geologist Erik Norin explored the desert during the Sino-Swedish expedition , he found layers of sandstone on the edge of the Kuruktagh and in the middle of the desert with fossils that were formed in the Tournaisium and are more than 345 million years old. Among the fossils he discovered were, for example, molluscs with various fossil snails of the genera Euomphalus and Bellerophon .

The drill cores, which were taken from a depth of 160–250 meters at the Lop Nor Environmental Science Drilling Project in 2003 , show that plants were growing here in the Middle Pleistocene , 781,000 to 1,806,000 years ago, and their descendants are still growing today occur in the Lop Nor desert. These are xerophytic species from the three taxa sea pigeons , goosefoot and wormwood . In addition, tree and shrub species that already existed in the Tertiary , i.e. over 2.6 million years ago, in the neighboring Gobi Desert grow in the desert . These include the tamarisk Tamarix ramosissima , Tamarix hispida , Tamarix taklimakanensis and Tamarix Hohenackeri and the poplars Populus euphratica and Populus pruinosa . During the flowering period in spring, the tamarisks glow in white, orange and purple colors. The white flowering shrub Zygophyllum xanthoxylum comes from the Holocene . It is one of the comparatively young plant species in the Lop Nor desert.

The halophytes have adapted to the living conditions in the Lop Nor lake basin. In 1985 there were only 36 species of halophytes left in the Lop Nor desert , belonging to 26 genera and 13 families . Compared to the research and reports of the explorers , twelve species have disappeared since 1876, the year of Nikolai Mikhailovich Prschewalski's first expedition . This also includes the water-loving Typhaceae , sour grass family and pondweed family . The remaining 36 halophytes give the Lop Nor lake basin a colored appearance in spring during the flowering period. They form the food for the animals that live in the salt desert. A popular forage plant for wild camels is Alhagi pseudalhagi . These camel spurs are high in protein and have long roots that reach down to the groundwater. Salt plants like Scorzonera divaricata are so powerful when they grow that they break through the very hard salt crust on their way to light. The salt plants of the Lop Nor desert include Apocynum venetum , Poacynum hendersonii , Halocnemum strobilaceum , reed , Halostachys caspida and Saussurea salsa .

History of settlement

On the rivers that led to the Lop Nor, river oases were created that made possible Bronze Age settlements 4000 years ago, in which people of European appearance lived, whose mummies were found in the early Bronze Age necropolises of Xiaohe and Käwrigul . The graves in Käwrigul were surrounded by five to seven concentric rings of close-knit poles to protect them from wind erosion; outside the rings stood numerous rows of vertical poles, which, viewed from the center of the grave, pointed radially in all directions. From 900 BC Chr. Developed Iron Age settlements with cemeteries. After the Iron Age, burial grounds were equipped with underground tombs. One of these cemeteries is 10 hectares in size and has deep underground tombs with vaults up to 30 meters high.

In northwest China, around 200 BC, A period of high temperatures and heavy precipitation, which was followed by a period of prolonged drought and drought from the third to the fifth centuries. From 200 BC The rivers that carried their water to Lop Nor became broad rivers that desalinated the water from Lake Lop Nor, carried fresh water over the lake shore and created large wetlands that could be used for agriculture. Lake Lop Nor was now of almost inestimable importance for the cultures of the Tarim Basin along the Silk Road , namely for the Uyghur Loplik, who inhabited this desert and lived mainly from fishing.

In records from the Han Dynasty (206 BC – 200 AD), Lake Lop Nor is described as follows: “P'u-ch'ang Hai (ie Lop Nor) covers an area of 300 Li (= 150 km) length and width, the water ends here, its height never changes. ”Old Chinese maps show the salt lake with a diameter of 150 km.

From 200 BC onwards, climate change led to BC to founding cities in Loulan , Miran , Haitou, Yingpan, Merdek and Qakilik . The city of Loulan with its Kingdom of Shanshan played a dominant role due to its location on the Middle Silk Road until the royal family was ousted by the Chinese Empire, which then controlled the Silk Road itself and secured it against attacks by the Xiongnu with signal towers along the Great Wall of China . The city of Loulan, which was located on a river and experienced an economic boom as an outpost for the Chinese, was abandoned around 330 along with other settlements on the Kum-darja because of the lack of water. One reason was the beginning of a change in the climate, which led to the rivers and river oases drying up and Loulan from now on lacking fresh water. It has also been suggested that the frequent earthquakes turned the Tarim in a different direction. The Middle Silk Road north of Lake Lop Nor was now impassable, and the population in the Lop Nor desert was rapidly declining.

According to a report by the Chinese Li Daoyuan entitled Shuijing zhu (Part 2), which was written before AD 527, the lake had three tributaries: Qiemo (i.e., Cherchen-Darya or Qarqan He), Nan (i.e., Tarim ) and Zhubin (i.e., Haedik-gol and its lower reaches Konqi , Konche-darja, and Kum-darja). Apparently, the Lop Nor lake was running again at this point. In the late Qing Dynasty , the lake was 80 or 90 Li (= 40 km to 45 km) long from east to west and 1–2 or 2–3 Li (= 500 m to 1 km or 1 km to ) from south to north 1.5 km) wide.

Between 1725 and 1921, the Karakoshun lake basin in the southwest of the Lop Nor desert was filled with fresh water from the Tarim, and the Lop Nor became a salt marsh. In 1921 the Karakoshun dried up and the Tarim brought its water back to Lop Nor.

The Uighur Loplik left around 1920 settlements in the Lop Nor desert after a plague - epidemic had led to numerous deaths there. The last time the Lop Nor was filled was in 1921; its size varied greatly, in 1928 it was 3,100 km², in 1931 1,500–1,800 km², in 1950 2,000 km² and in 1958 5,350 km². The Lop Nor had the lowest water level in 1934 in the ear-shaped helix , and a water level only a few centimeters high existed between the helix and the confluence of the river Kum-darja to the north. Sven Hedin sailed the northern part of the lake on May 16, 1934. According to his information, the lake was 130 km long and up to 80 km wide. The wetlands on the lake had a size of 10,000 km².

Since 1949, numerous irrigation projects have been carried out in the Tarim Basin and in the Yanji Basin - later under the direction of the Xinjiang Production and Development Corps founded in 1954 - in order to settle immigrant Han Chinese in Xinjiang. In the area of the Tarim and its tributaries alone, the irrigated arable land increased from 351,200 ha in 1949 to 776,600 ha in 1994; During the same period, irrigation canals with a length of 1,088 km and 206 reservoirs with a total capacity of 3 billion cubic meters of water were built. The excess water from Lake Bosten , which until 1949 had primarily fed the Lop Nor, has been used to irrigate the Yanji Basin since 1949. The outflow of the Bosten Lake, the Konqi , has received little water since then and could no longer supply the Konche-darja and its lower reaches Kum-darja or the lower reaches of the Tarim . From 1958 to 1961 or until 1962, Lop Nor and its wetlands fell completely dry. This led to the death of the bank vegetation at Lake Lop Nor and the expansion of the dunes.

For ecological reasons, water has been discharged from Lake Bosten several times since April 2000 via the Konqi into the Tarim and Lake Lop Nor. According to a resolution of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region from the winter of 2000-2001, water from the Lio River is to be channeled through a tunnel under the Tian Shan Mountains to the Tarim River so that Lake Lop Nor can be re-created by water from the Ilo. The project is called “Redirecting Water from North to South”.

The started development of a sylvin field by Lop Nur Sylvite Science and Technology Development Co., Ltd and the planned development of the rich deposits of oil, natural gas, coal and minerals will lead to the development of an infrastructure in the desert with first roads and a workers' town to lead. A preliminary work for this is the publication of 49 topographical maps of the Lop Nor desert in 2007 on a scale of 1: 50,000, which should facilitate the prospecting of the soil deposits. The previous map series of the Lop Nor Desert came from Sven Hedin , whose Central Asia atlas was published in 1966 by the Stockholm Ethnographic Museum. In this series of maps, Sven Hedin used the route recordings that were made during his own expeditions and during Sir Aurel Stein's expeditions between 1896 and 1935.

Exploring the desert

Early reports

The Chinese pilgrim Faxian traveled from China to India in the 4th century and described the Lop Nor desert as follows:

“There are many demons and hot winds in her. Those who meet them die to the last man. There are no birds or other animals. If you look around as far as the eye can see to find the way, there are no clues, except for the rotting bones of the dead, which show the way. "

The Lop Nor desert was described by Marco Polo , who visited the city of Lop in 1274 :

“A most curious thing is reported about this desert. If a man of a tour company that is out and about at night stays behind or falls asleep and then tries to reach his people again, he hears ghost voices calling him by name. Believing that they are his comrades, he is led astray, so that he never finds the caravan again and perishes miserably. A stray traveler can also sometimes hear the patter of large riders off the beaten track. He then takes this to be the noise of his companions; he follows the sound and it is only at dawn that he realizes that he has been fooled. It is therefore common for travelers to stick together closely on this route. All animals also have large bells around their necks so that they cannot get lost so easily. This is the only way to cross the Great Desert. "

Marco Polo called the desert Lop Nor at that time the Lop desert . Giacomo Gastaldi inscribed it in 1561 as Diserto de Lop in his painted map of Asia in the Doge's Palace in Venice . The Swedish artillery lieutenant Renat issued a map of Central Asia in 1733 in which he had entered the Lop Nor lake under the name Läp . The Dutchman Daniel de La Feuille published a map of Asia around 1706 and referred to the Lop Nor desert as Desert de Lop .

Scientific research

From 1928 to 1935 the Sino-Swedish expedition led by Sven Hedin explored the Lop Nor desert extensively. Folke Bergman published the archaeological results in his English-language book Archaeological Researches in Sinkiang. Especially the Lop-Nor region , which also contains maps of the numerous sites.

When this book had been translated into Chinese decades after its publication, Chinese archaeologists at the end of the 20th century carried out numerous excavations at the sites that had been discovered during the Sino-Swedish expedition and documented by Folke Bergman. During the excavations they uncovered Bronze Age and Iron Age cemeteries, the coffins of which contained mummies up to 4,000 years old . This confirmed Sven Hedin's assumption that the eastern Tarim Basin was settled by Indo-Europeans , the later Tocharians , over 4000 years ago . The excavation at Folke Bergman's early Bronze Age necropolis Xiaohe on the “Schmalen Fluss” (also: Small River, Xiaohe, Qum-köl), which was completed in 2004, was one of the “Top Ten Archaeological Finds 2004” in China. As robber excavations are constantly taking place in the Lop Nor desert and this cannot be prevented, the Chinese government decided to dig, secure and document the more than 80 sites described by Folke Bergman from 2006 onwards.

Sven Hedin and Folke Bergman found ruins of signal towers that had stood on the Great Wall of China, and were thus able to continue Sir Aurel Stein's research and reconstruct the original course of the Middle Silk Road in the Lop Nor desert. When interest in the Great Wall of China awoke around 1980 , the Chinese scientists discovered in Folke Bergman's book, to their astonishment, that the course of the Great Wall of China had been explored 50 years earlier by the Sino-Swedish expedition and that the wall once reached the western border of Xinjiang .

Archaeological sites

Cities

Loulan

In 1901 Sven Hedin discovered the ruins of the 340 x 310 m, walled-in former royal city and later Chinese garrison city of Loulan . He found the remains of the brick building of the Chinese military commander, a signal tower of the Great Wall of China on the Silk Road and 19 houses made of poplar wood. He also laid during archaeological excavations a wooden wheel free, (from a horse-drawn cart Araba called) came, and which have been made in the years from 252 to 310,276 written documents from wood, paper and silk, and disruption gave the history of the city. Sir Aurel Stein also carried out excavations in 1906. After 1980, Chinese archaeologists finally started excavations.

The city of Loulan was first established in 176 BC. Mentioned in a letter from the Xiongnu ruler to the emperor of the Han dynasty Wendi . A report from the year 126 BC BC via Loulan comes from the Chinese diplomat Zhang Qian, who traveled the Silk Road from 139 to 123 BC. BC on behalf of the Chinese Emperor Han Wudi . He reported of a town with about 14,000 inhabitants and wrote: The areas of Loulan and Gushi have a walled city and walled suburbs; they lie on the salt marsh.

Loulan was abandoned around 330. The cause was a change in climate, which led to the fact that the rivers and river oases dried up and that from now on there was no fresh water in Loulan. It is also believed that the frequent earthquakes have steered the Tarim in a different direction.

In 1994 Christoph Baumer found a large former orchard about 5 km south of the city. He writes: “In front of us are more than 20 long rows of withered fruit trees, which must have come from the 4th century AD. It is probably apricot trees. "

Miran

Sven Hedin discovered the ruined city of Miran in the south of the Lop Nor desert in 1900 . Sir Aurel Stein carried out excavations there in 1907 and 1914. Chinese archaeologists began further excavations after 1950. Miran was probably an outpost of the Shanshan Empire with Buddhist monasteries, wall paintings and stupas in the 3rd century . In the 8th century Miran was a Tibetan garrison town with corresponding fortifications. Perhaps Miran was the place called Yixun in the Han annals .

Necropolis

On the lower reaches of the Konqi there are numerous archaeological sites of tombs and necropolises . The excavations suggest that the river banks were built around 1800 BC. BC and from 202 BC Until the year 420 were settled. Burials took place in the Käwrigul necropolis around 1800 BC. And in the Yingpan necropolis in the period from 220 to 420. The large Xiaohe necropolis is located on the Narrow River and was built 4000 years ago. Settlements from that time have not yet been found at this necropolis.

Käwrigul

The Käwrigul necropolis ( Chinese 古墓 沟 , Pinyin Gumugou ) is located about 70 km west of the dried up Lake Lop Nor next to the lower reaches of the Konqi on a small dune. The burial ground dates back to around 1800 BC. Dated. Its size is 1500 km². In 1979, 42 graves were excavated on it, which are divided into two groups in terms of surface features, finds and burial customs.

- The first group consisted of 36 shaft graves sunk shallowly in the sand. In addition to a few group graves for two to three men, there were mostly individual graves in which men, women and 13 children were buried stretched out on their backs, their heads in the east and feet in the west.

- The second group consisted of six individual graves in which men were buried who also lay on their backs, their heads in the east and their feet in the west. Around each of these graves were seven closely placed circles of posts, which were surrounded by a wide ring of many other posts, which were set up radially outwards.

Because of the extreme aridity and the high salt content of the soil, two complete mummies were found in Käwrigul in excellent condition. One of them is the beauty of Loulan , which is on display in the Urumqi Museum.

Great Wall of China

The Middle Silk Road ran from Dunhuang via Yumenguan on a not yet clearly defined route through the Lop Nor desert. She crossed the encrusted lake basin north of Lake Lop Nor and was watched by soldiers at the forts LJ, Tuken and LE before the Silk Road reached the city of Loulan (LA, i.e. Loulan station). From Loulan it led on the north bank of the lower reaches of the Konqi, which at that time ran south, to the city of Yingpan and along 10 signal towers to the city of Korla . This middle section of the Silk Road was built by 120 BC. BC up to the year 330 mainly used in winter because the caravans could transport water supplies in the form of ice blocks during frost.

Since the Han dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD), signal towers served as watchtowers for orientation and safety for travelers on the Middle Silk Road. Ruins of the Great Wall of China signal towers on the Silk Road have been found in the Lop Nor desert in the following locations: Miran; 45 km south of Loulan (name of the fortress: LK); 20 km northeast of Merdek at the "Schmalen Fluss"; on the north and north-west edge of Lake Lop Nor (names of fortresses: LJ, Tuken, LF, LE and LA, i.e. Loulan); in Yingpan and from there to the west on the north bank of the Kum Darya and the Konche Darya at close distances to the cities of Korla and Charchi.

From the 2nd century on, the Northern Silk Road became an alternative to the Middle Silk Road. It avoided the dreaded Lop Nor desert by heading north-west to Turfan from Dunhuang . In Kashgar it flowed into the southern Silk Road. After the Lop Nor lake dried up, only the southern Silk Road was used from 330; it led from Dunhuang south by Lake Lop Nor and then from Miran to Qakilik ; Marco Polo used this route .

There was also a connecting road from Miran to Loulan, which connected the Middle and South Silk Road. On this road 45 km south of Loulan stood the fortress LK with the settlements LL, LM and LR to the west. To the north of LK this road ran through an area with yardangs. Another road possibly led from Miran or Qakilik past the fortress Merdek to the "Narrow River", which was monitored by a signal tower. From there this road joined the Middle Silk Road, which ran along the Kum Darya River.

Natural resources

See “Development of Mineral Resources” in the Lop Nor article .

Wild camel sanctuary

Nikolai Michailowitsch Prschewalski met wild camels south of the Karakoshun in 1876 . He did not succeed in killing any of them; Nevertheless, three prepared camels came into his possession. After he had put a high bounty on the animals, these three skins were brought to him by local hunters three weeks later and sold. The very rare and shy wild camels have been unknown since Marco Polo's time. Therefore, at the end of the great Central Asia expedition, these three skins were among the most important exhibits in his collection. Sven Hedin also found wild camels in 1901 on Kum-darja near Lop Nor. In 1927, the Russian scientist AD Simukov researched the distribution and way of life of these wild saltwater camels, Camelus ferus ferus , which can drink salt water and are optimally adapted to Lake Lop Nor.

According to official estimates from 2001, there are around 600 of these saltwater camels in China and a further 300 saltwater camels in the Mongolian Gobi Desert, where the Southern Altay Gobi Nature Reserve (also: Great Gobi Reserve A) exists. As far as is known, 15 saltwater camels are kept in captivity in China and Mongolia.

In the Red List of Threatened Species of IUCN , the wild Bactrian camels (salt water camels) since 2002 as threatened with extinction (critically endangered) , respectively. It is expected that the population in Mongolia and accordingly also in China will decrease by 84% by 2033 (in the third generation after 1985). The Mongolian subpopulation decreased from 650 animals to 350 animals in the years 1984 to 2006, the Chinese population shrank in the years before 2006 by around 20 animals that were killed by hunters or mine layers.

In the years 1980–1981, the research group of the Chinese Academy of Sciences toured the Lop Nor desert and created a map of the range of the saltwater camels. John Hare checked the population of the saltwater camels first in 1992 in the Gashun Gobi Desert and later in the years 1995–1999 in the Lop Nor Desert. In 1997 he became one of the founders of the Wild Camel Protection Foundation, which is committed to protecting the last living saltwater camels.

The Wild Camel Protection Foundation worked with the Chinese government to plan a large-scale conservation area for these animals, which is financially supported by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP). On March 18, 1999, this protected area was established by the Chinese State Office for Environmental Protection (SEPA) with the name "Xinjiang Lop Nur Nature Sanctuary of China" (also: Xinjiang Lop Nur Wild Camel National Nature Reserve). In 2003 it became a National Nature Reserve with the new name Lop Nur Nature Reserve and is subject to SEPA. It has an area of 107,768 km² and encloses both the Lop Nor lake basin and the Lop Nor Chinese nuclear weapons test site . Its borders touch three other protected areas: Arjin Shan Reserve (15000 km²), Annanba Protected Area (3960 km²) and Wanyaodong (333 km²). Other sources speak of the Arjin Shan Lop Nur Nature Reserve with a size of 65,000 km².

In 2001, only five of the 15 road access roads into the protected area were monitored by checkpoints. The establishment of this nature reserve to preserve biodiversity , the ecosystem and the landscape shaped by yardangs in Lop Nor was funded on November 6, 1998 as Project 600 by the Global Environment Facility until 2001 with a grant of $ 750,000. The German contribution to this grant was $ 90,000. The Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region will cover the running costs of the sanctuary, including fuel and personnel costs.

A danger for this protected area comes from the workers who are employed in the industrial extraction of mineral resources in the lake basin of Lop Nor, since the protected saltwater camels are traditionally hunted as sport or as fresh meat suppliers, although their hunting is strictly prohibited in China. A gas pipeline, which was to be led underground through the protected area in a west-east direction, was finally laid outside the protected area.

risk of death

Security notice

The development of the Lop Nor desert by roads for the extraction of raw materials leads to the increasing tourist development of the desert. Tourists shouldn't hide the fact that the Lop Nor desert is one of the most treacherous areas in Asia. A basic rule is that when leaving the safe place (e.g. tent, vehicle, bus, building), the traveler has to wear everything that is necessary for survival for the next few days. Even forgetting to drink water, a spare battery, torch, respiratory protection or medication can be dangerous.

The dangers lie not only in the extreme temperatures, but also in the sudden loss of orientation. There is also the risk of sudden sandstorms, which make it difficult to see, orientate and breathe and make breathing protection necessary. Professional advice is therefore necessary to prepare for excursions into the desert.

The Peng Jiamu case

The Chinese Peng Jiamu (1925–1980) was a trained chemist and geologist and worked as Vice President of the Institute for Environmental Protection in Xinjiang . The Chinese Academy of Sciences asked him to lead three scientific expeditions to explore the Lop Nor desert in 1980 and 1981. The scientists on the expeditions included chemists, geologists, biologists, and archaeologists. The first expedition began in May 1980. In June, the scientists reached the Kum Tagh sand dunes in the south of the Lop Nor desert. The drinking water had been lost on the way there.

On the morning of June 17, the scientists left the campground to look for water, while Peng Jiamu telegram to call for rescue workers and set off with a water bottle and two cameras. When the scientists returned to the camp site, they found a piece of paper that Peng Jiamu had written on it, "I am going east to sources, Peng, on June 17th at 10:30 am." They therefore suspected that Peng Jiamu was the source wanted to visit, which was marked on their map. Time passed, but Peng Jiamu did not return to the campground.

Hundreds of soldiers with airplanes and helicopters and six policemen with police dogs then searched the wide area, but they only found a few footprints left by Peng Jiamu. Three more major searches remained unsuccessful.

In the winter of 2004/2005, the scientist Dong Zhiguo found a mummified body on an expedition to the city of Dunhuang about 50 km from the then campground. He left it untouched, in accordance with the regulations in force, to be examined by specialists in the spring. A team of researchers went to the site on April 11, 2005 to see if it was the mummy of Peng Jiamu. The team members did not find any clothes or shoes on the mummy, nor the water bottle and cameras that Peng Jiamu was carrying, and took the mummy to the Dunhuang City Museum. The scientific assignment of this mummy to Peng Jiamu was not successful in spring 2006 with a DNA analysis .

The Yu Chunshun case

The Chinese Yu Chunshun from Shanghai († 1996) planned to cross all of China on foot alone. Between 1988 and 1996 he covered a total of 42,000 km in 72 expeditions. In June 1996 he wanted to cover a distance of 97 kilometers through the dried out Lop Nor lake basin in three days. Local people warned him that the ground in the Lop Nor Desert can heat up to 75 degrees Celsius in June, but Yu Chunshun did not allow himself to be dissuaded from his plan.

Chinese television was supposed to film him as he crossed the desert. The television team followed the selected hiking route and deposited drinking water and provisions every seven kilometers . On the morning of June 11, 1996, Yu Chunshun went out. Because it was a particularly hot day, the TV crew was concerned and followed him in the SUV. But Yu Chunshun did not let himself be stopped and continued to walk to his overnight place in the evening.

On June 13th, he did not come to the designated meeting point. A large-scale search for him was unsuccessful in the next few days. On June 18, the crew of the search helicopter found him away from his first overnight place. Yu Chunshun died naked in his tent. He hadn't found the place to sleep with drinking water and provisions, although it was only two kilometers away. The rescue team leader said that Yu Chunshun deviated west at a point where he had to go south. Doctors named excessive temperature fluctuations as the cause of death, which even cause stones to burst. Since then, there has been a memorial with his friends' paper flowers at the place where the body was found.

literature

- Nikolai Michailowitsch Prschewalski : From Kulja, Across the Tian Shan, to Lob-Nor . 1879.

- Sven Hedin : In the heart of Asia . FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1903.

- Sven Hedin : Lop-only. Scientific Results of a Journey in Central Asia 1899–1902. Vol. 2. Stockholm 1905.

- Ellsworth Huntington : The Pulse of Asia . Boston / New York 1907.

- Sir Aurel Stein : Serindia, detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China . Oxford 1921. (Text material is contained in Volume 1 and Volume 2 ; Images are contained in Volume 4 ; Maps are contained in Volume 5 ).

- Sir Aurel Stein: Innermost Asia: Detailed Report of Explorations in Central Asia, Kan-Su and Eastern Iran. Volume 1. Oxford 1928 (maps are contained in Volume 4 ).

- Emil Trinkler : The praise desert and the Lobnor problem based on the latest research. In: Journal of the Society for Geography in Berlin. Berlin 1929, p. 353ff. ISSN 1614-2055

- Albert Herrmann: Loulan. China, India and Rome in the light of the excavations at Lobnor. FU Brockhaus, Leipzig 1931.

- Folke Bergman : Archaeological Finds. In: Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen Gotha 1935. ISSN 0031-6229

- Nils Hörner: Resa till Lop . Stockholm 1936 (Swedish, not translated into German).

- Parker C. Chen: Lop nor and Lop desert . In: Journal Geographic Soc. of China. Nanking 1936.3.

- Sven Hedin : The Wandering Lake . FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1937, Wiesbaden 1965.

- Folke Bergman: Archaeological Researches in Sinkiang. Especially the Lop-Nor region. Reports: Publication 7. Stockholm 1939 (English. The basic work on the archaeological finds in the Lop Nor desert with important maps, translated into Chinese around 2000).

- Sven Hedin, Folke Bergman: History of an Expedition in Asia 1927-1935 . Part III: 1933-1935. Reports: Publication 25. Stockholm 1944.

- Vivi Sylwan: Investigation of silk from Edsengol and Lop-nor and a survey of wool and vegetable materials . Stockholm 1949.

- Huang Wenbi : Meng Xin Kaocha riji 1927-1930 [Huang Wenbi's Mongolia and Xinjiang Survey Diary], Beijing: Wenwu Chubanshe 1990

- Huang Wenbi: The Exploration around Lob Nor: A report on the exploratory work during 1930 and 1934 . Beijing 1948 (English and Chinese).

- Herbert Wotte : Course towards unexplored . FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1967.

- Zhao Songqiao, Xia Xuncheng: Evolution of the Lop Dessert and the Lop Nor. In: The Geographical Journal. 150 No. 3, November 1984, pp. 311-321. ISSN 0016-7398 ( abstract )

- Xia Xuncheng, Hu Wenkang (Eds.): The Mysterious Lop Lake. The Lop Lake Comprehensive Scientific Expedition Team, the Xinjiang Branch of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Science Press, Beijing 1985 (bilingual English and Chinese throughout; expedition results from the years 1980/1981 with pictures and maps; a supplement to the work of Folke Bergman Archaeological Researches in Sinkiang. Especially the Lop-Nor Region , which was not known to the expedition members at the time ; loanable in the university library of the Technical University of Berlin)

- Helmut Uhlig: The Silk Road. Ancient world culture between China and Rome. Gustav Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1986, ISBN 3-7857-0446-1

- Xia Xuncheng: A scientific expedition and investigation to Lop Nor Area. Scientific Press, Beijing 1987.

- Christoph Baumer: Ghost towns on the southern Silk Road, discoveries in the Takla-Makan desert. Belser, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-7630-2334-8 (report from his expedition into the Lop Nor desert and to Loulan 1996, pp. 159–179)

- Gunnar Jarring : Central Asian Turkic Place-names Lop Nor and Tarim area. An Attempt of Classification and Explanation Based on Sven Hedin's Diaries and Published Works. Sven Hedin Foundation, Stockholm 1997, ISBN 91-85344-37-0

- Elizabeth Wayland Barber: The Mummies of Urumchi. New York City 1999, ISBN 0-393-04521-8

- Christoph Baumer: The southern silk road. Islands in the sand sea. Mainz 2002, ISBN 3-8053-2845-1 (with current references)

- John Hare : On the trail of the last wild camels. An expedition to forbidden China. Foreword by Jane Goodall. Frederking & Thaler, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-89405-191-4

- Yuri Bregel: An Historical Atlas of Central Asia. Brill, Leiden 2003, ISBN 90-04-12321-0

- Alfried Wieczorek, Christoph Lind (Ed.): Origins of the Silk Road. Sensational new finds from Xinjiang, China. Exhibition catalog of the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museums, Mannheim. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 3-8062-2160-X

- Feng Zhao: Treasures in Silk. An illustrated history of Chinese textiles. Hangzhou 1999, ISBN 962-85691-1-2

- Fiction

In 2000 the writer Raoul Schrott published a novella entitled The Desert Lop Nor .

Web links

- Search for Desert Lop Nor in the German Digital Library

- Search for "Lop Nor" in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

- Blue Marble Images of Silk Road . In: dsr.nii.ac.jp (animation of the Lop Nor desert as the seasons change).

- GEF Project ID 600: Lop Nur Nature Sanctuary Biodiversity Conservation . In: gefonline.org

- Satellite image of the plant for the production of 1.2 million tons of potash fertilizer annually.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Gansu drawing the 1st topographic map of Lop Nor ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ a b Xia Xuncheng, Hu Wenkang (ed.): The Mysterious Lop Lake. The Lop Lake Comprehensive Scientific Expedition Team, the Xinjiang Branch of the Chinese Academy of Sciences . Science Press, Beijing 1985, pp. 49 (English).

- ↑ Shi Peijun, Yan Ping, Yuan Yi: Wind Erosion Research in China: Past, Present and Future . Beijing 2002.

- ↑ Johannes Küchler, Birgit Kleinschmit, Ümüt Halik: Before the earth becomes a desert . In: TU International . tape 57 , 2005, p. 34–37 ( pdf ( memento of January 9, 2007 in the Internet Archive )). Before the earth turns into a desert ( memento of the original from January 9, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was automatically inserted and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Experts Claim Quaternary Freshwater Lake at Lop Nor. china.org.cn, October 14, 2003, accessed December 12, 2008 .

- ^ Albert Herrmann: Loulan. China, India and Rome in the light of the excavations at Lobnor . FU Brockhaus, Leipzig 1931, p. 52 (A map with the lake terraces can be found on pages 56–57).

- ↑ Dieter Jäkel found 40 km west of Ruoqiang on the road to Qiemo at an altitude of about 1000 m above alluvial fans that ended abruptly on the slope to the plain. He writes: “ Thus there are many factors indicating the existence of a palaeo-Lob-Nor with a lake level of + - 1000 m asl ” Die Erde 1991, supplementary booklet 6, p. 196f.

- ↑ Christoph Baumer: Ghost towns on the southern Silk Road, discoveries in the Takla-Makan desert. Belser, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-7630-2334-8 , pp. 159-179.

- ↑ Xia Xuncheng and Zhao Yuanjie: Some Latest Achievements in Research on Environment and its Evolution in Lop Nur Region by Xia Xuncheng and Zhao Yuanjie. ( Memento of the original from September 22, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF file; 412 kB), Science Foundation in China Vol. 13, No. 2. 2005.- LI BaoGuo, MA LiChun, JIANG PingAn, DUAN ZengQiang, SUN DanFeng, QIU HongLie, ZHONG JunPing & WU HongQi: High precision topographic data on Lop Nor basin's Lake “Great Ear” and the timing of its becoming a dry salt lake , In: Chinese Science Bulletin 53, Mar 2008, No. 6, pp. 905-914.

- ↑ Sven Hedin : In the heart of Asia . FA Brockhaus, Leipzig 1903.

- ↑ Xia Xuncheng, Hu Wenkang (ed.): The Mysterious Lop Lake. The Lop Lake Comprehensive Scientific Expedition Team, the Xinjiang Branch of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Science Press, Beijing 1985 pp. 30-39.

- ↑ John Hare: In the footsteps of the last wild camels. An expedition to forbidden China. Frederking & Thaler, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-89405-191-4 .

- ↑ Sir Aurel Stein's research on “Dragon City” can be found in Innermost Asia Volume 1 on pages 290 to 295.

- ↑ The text is quoted from Helmut Uhlig: Die Seidenstrasse. Ancient world culture between China and Rome. Gustav Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1986, ISBN 3-7857-0446-1 , p. 158.

- ↑ The basin with brine can be seen on the right edge of the picture.

- ↑ Wendy Chen: Old plants could soon just be history.

- ↑ Xia Xuncheng, Hu Wenkang (ed.): The Mysterious Lop Lake. The Lop Lake Comprehensive Scientific Expedition Team, the Xinjiang Branch of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Science Press, Beijing 1985. pp. 69-81.

- ↑ Evidence for a late Holocene warm and humid climate period and environmental characteristics in the arid zones of northwest China during 2.2 ~ 1.8 kyr BP In: Journal of Geophysical Research . Vol. 109, 2004, D02105, doi: 10.1029 / 2003JD003787 .

- ↑ Xia Xuncheng, Hu Wenkang (ed.): The Mysterious Lop Lake. The Lop Lake Comprehensive Scientific Expedition Team, the Xinjiang Branch of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Science Press, Beijing 1985, p. 49.

- ↑ His description of the lake can be found here: Sven Hedin: The wandering lake . 2nd edition, 1938, pp. 118-136.

- ↑ Discussion on the dried-up time of the Lop Nur Lake ( Memento of the original dated February 7, 2015 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. .

- ↑ Leading Chinese academy says Lop Nur disappeared in 1962 ( Memento of the original from May 1, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. . In: uhrp.org .

- ↑ Scientists complete mapping "sea of death" in NW China desert. and topography and cartography in Lop Nor.

- ^ Sven Hedin: Central Asia atlas. Maps, Statens etnografiska museum. Stockholm 1966 (published in the series Reports from the scientific expedition to the north-western provinces of China under the leadership of Dr. Sven Hedin. The sino-swedish expedition . Issue 47. 1. Geography; 1).

- ↑ The text is quoted from Johannes Paul: Marco Polo: Seidenstrasse . In: Adventurous Journey through Life - Seven Biographical Essays . Wilhelm Köhler Verlag, Minden 1954, p. 28.

- ^ Folke Bergman: Archaeological Researches in Sinkiang. Especially the Lop-Nor region. Reports: Publication 7. Stockholm 1939.

- ↑ Also: Cemetery 5, Ördeks Necropolis.

- ↑ Christoph Baumer: Ghost towns on the southern Silk Road, discoveries in the Takla-Makan desert. Belser, Zurich 1996, ISBN 3-7630-2334-8 , p. 167.

- ^ Jeanette Werning: Käwrigul, Gumugou. In: Alfried Wieczorek, Christoph Lind (Hrsg.): Origins of the Silk Road. Sensational new finds from Xinjiang, China. Exhibition catalog of the Reiss-Engelhorn-Museums, Mannheim. Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 3-8062-2160-X . Pp. 102-104.

- ↑ Maps and research results on the houses, fortresses, signal towers, streets etc. see: Folke Bergman: Archaeological Researches in Sinkiang. Especially the Lop-Nor region. (Reports: Publication 7), Stockholm 1939 and in the work: Xia Xuncheng, Hu Wenkang (eds.): The Mysterious Lop Lake. The Lop Lake Comprehensive Scientific Expedition Team, the Xinjiang Branch of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Science Press, Beijing 1985.

- ↑ Xia Xuncheng, Hu Wenkang (ed.): The Mysterious Lop Lake. The Lop Lake Comprehensive Scientific Expedition Team, the Xinjiang Branch of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Science Press, Beijing 1985, p. 82.

- ↑ The expeditions were called The Lop Lake Comprehensive Scientific Expedition . Her research has been published here: Xia Xuncheng, Hu Wenkang (Eds.): The Mysterious Lop Lake. The Lop Lake Comprehensive Scientific Expedition Team, the Xinjiang Branch of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Science Press, Beijing 1985.

- ↑ See various newspaper reports and Memories of great desert explorer live on . In: peopledaily.com.cn , April 19, 2006.

- ↑ Geographic coordinates: 40 ° 33 '52.55 " N , 90 ° 19' 3.17" O .

- ^ Image of Yu Chunshun's tombstone ( memento from October 12, 2016 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Claus Richter, Bruno Baumann, Bernd Liebner: The Silk Road. Myth and Present. Hoffmann and Campe, Hamburg 1999, pp. 152–154.

Coordinates: 40 ° 10 ′ N , 90 ° 35 ′ E