Warsaw uprising

| date | August 1 to October 2, 1944 |

|---|---|

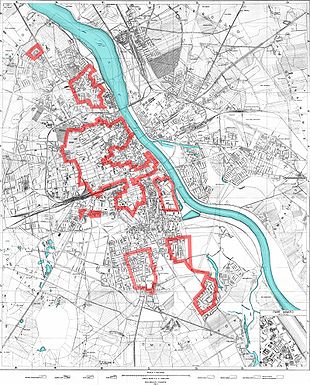

| place | Warsaw |

| exit | Suppression of the uprising |

| Parties to the conflict | |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Commander | |

| Troop strength | |

| 45,000 | 39,000 |

| losses | |

|

15,000 dead, 25,000 wounded, 150,000–225,000 civilian casualties |

2,000–10,000 dead, 0–7,000 missing and 7,000–9,000 wounded |

The Warsaw Uprising was the military uprising of the Polish Home Army ( Armia Krajowa , shortly AK ) against the German occupation in World War II in Warsaw from August 1 to October 2, 1944. From the Polish government in exile in London as part of the nationwide Operation Tempest ordered , alongside the Slovak National Uprising, it was the largest uprising against the National Socialist system of rule in East Central Europe . The resistance fighters fought against the occupation forces for 63 days before capitulating in the face of the hopeless situation . German troops committed mass murders among civilians, and the city was almost completely destroyed after the uprising. The question of why the Red Army on the other side of the Vistula - with the exception of the 1st Polish Army - did not intervene in the fighting is controversial among historians.

prehistory

Location in Poland

After the Polish army was crushed by the German attack in September 1939, German and Soviet troops occupied the country in accordance with the Hitler-Stalin Pact . The western part fell to the German Empire, the eastern part to the Soviet Union.

The German way of dealing with the vanquished was dominated by National Socialist racial policy from the start . West Prussia , East Upper Silesia , the Wartheland and the administrative district of Zichenau were annexed and incorporated into the German Reich as new Reichsgaue or connected to existing Reichsgaue. The annexed areas included parts of Poland that had never been part of Germany before and that were predominantly Polish. The remaining part of Poland under German occupation was under German administration as the Generalgouvernement . The main aim was the economic exploitation and oppression of the Polish population. At the beginning, the German repression mainly hit intellectuals and Poles of Jewish descent. In the so-called intelligence campaign, mass shootings and mass arrests were organized among the country's educated elite. The Jews were ghettoized and thus separated from the rest of the population. Education and the press were cut to a minimum in order to cement the oppression of the Slav population. In a note from SS chief Himmler it says:

“A fundamental question in solving all these problems is the school question, and with it the sifting and sifting of the youth. For the non-German population of the East there is no higher school than the four-class elementary school. The goal of this elementary school has only to be: Simple arithmetic up to a maximum of 500, writing the name, a teaching that it is a divine command to be obedient to the Germans, and to be honest, hardworking and good. I don't consider reading necessary. Apart from this school, there must be no school at all in the East […]. After a consistent implementation of these measures, the population of the Government General will inevitably consist of a remaining inferior population [...] over the next ten years. This population will be available as a leaderless workforce and Germany will provide migrant workers and workers for special jobs (roads, quarries, buildings) every year. "

Likewise, the industry was expropriated and approximately 900,000 Poles as forced laborers in the realm deported . Through the introduction of special courts by the occupying power, the Poles were degraded to subjects without rights in their own country. In his Reichstag speech on October 6, 1939, Hitler had already announced that major resettlements would have to take place in order to return German ethnic groups that were fragmented in Eastern Europe back to the Reich. On the basis of state treaties , ethnic German population groups were resettled in two waves of emigration from Volhynia , Eastern Galicia , Bukovina and Bessarabia as well as mainly from the Baltic States and resettled in the Wartheland. For this purpose, space was created in the Warthegau by order of the authorities through the ruthless transfer of 1.2 million Poles and 300,000 Jews to the Generalgouvernement in ways that would later affect the German ethnic groups.

In the course of the war, the Generalgouvernement also became a main venue for the Holocaust . A total of 2.7 million Polish citizens of Jewish descent were killed in industrialized mass murder. As early as February 1940, the German governor-general Hans Frank said to a journalist: B. posted large red posters that said that 7 Czechs had been shot today. I said to myself; if I wanted to put up a poster for every 7 Poles shot, then the forests of Poland would not be enough to produce the paper for such posters. "

The USSR initiated a policy of sovietization in occupied eastern Poland from 1939 to 1941. The most prominent features of this project were land reform, forced collectivization, dissolution of social associations and the nationalization of industry. This reorganization along the lines of the communist state was accompanied by repression against the population. Shootings, arrests and convictions resulted in mass deportations to penal camps on Soviet soil. These repression followed a social grid. The Soviet organs focused particularly on landowners, former civil servants, entrepreneurs, politicians from the non-communist parties, priests and intellectuals. Estimates of the number of people displaced range from 700,000 to 1.8 million people.

Polish government in exile

After their country had been militarily defeated and divided, around 85,000 Polish soldiers and officers, as well as a large number of Polish politicians, managed to flee to France . Other parts of the Polish military, along with Polish President Ignacy Mościcki and the Commander in Chief of the Armed Forces, fled to Romania , where both politicians were interned and the soldiers were disarmed. In the event that the President could no longer exercise his office, the Polish constitution provided for the transfer of government power; For this reason, Ignacy Mościcki appointed Władysław Raczkiewicz, who was staying in France, as his successor. This formed a new government from the members of the largest political parties who had fled to France, headed by General Władysław Sikorski and General Kazimierz Sosnkowski as his deputy. Thus, on September 30, 1939, the Polish government- in- exile was formed in France, which was immediately recognized by the government of France and shortly afterwards by the governments of Great Britain and the USA as the only legitimate Polish government. After the defeat of France in 1940, this government and part of the military fled to London.

Resistance and the underground state

As a result of the repression by the Germans, a Polish underground state quickly formed, which followed the long tradition of Polish resistance against foreign occupiers in the context of the partitions of Poland . A secret press and social welfare system was organized as well as “illegal” universities. The funds for this came from the population themselves or from funds that had been smuggled in from London. This civil arm of the resistance passed seamlessly into the establishment of armed groups. The Polish military had already founded the underground organization Służba Zwycięstwu Polsce ( Service for the Victory of Poland , SZP) on September 27, 1939, shortly before the surrender and before the establishment of the government in exile . Furthermore, further resistance groups formed spontaneously just weeks after the defeat of the regular army. They fed themselves mainly from the reservoir of former officers and civil servants as well as from the youth organizations of the parties. In particular, scout organizations ( Szare Szeregi ) later made up a large and often particularly motivated part of the recruits for the resistance.

The Polish Resistance subordinated itself to the government-in-exile, as, according to its self-image, it was a continuation of the Second Republic from the beginning . The government-in-exile tried to unite all these resistance groups, so that by the turn of the year 1943/44 the ZWZ (Polish: Związek Walki Zbrojnej ; German: Association for the Armed Struggle ) was established, which combined most of the Polish resistance. The united resistance was further referred to as Armia Krajowa (German: Home Army ; abbreviation: AK ). In 1944 it comprised a total of around 300,000–350,000 members. Only the forces of the extreme right and the extreme left stayed away from this alliance: On the one hand, the right-wing national anti-communist NSZ militia, which in some cases even worked with the German occupiers, but had only around 35,000 supporters, on the other hand the Communist Armia Ludowa (German: People's Army ; abbreviation: AL ), which tried to establish itself as a counterpoint to the AK after the attack on the Soviet Union . It reached up to 100,000 members.

London and the AK leadership in Poland agreed that the main tasks of the resistance should be to carry out espionage work for the Allies, to damage German armaments and the transport system through acts of sabotage, and to repay particularly brutal actions by the occupier. At first they did not want to carry out open warlike actions. On the one hand because of the low military strength of the ZWZ at the beginning, and on the other hand in order not to provoke repression against the civilian population on the part of the German occupiers. The commander of the ZWZ underground, Colonel Stefan Rowecki, wrote in November 1939: The resistance can only openly emerge when Germany collapses, or at least one leg buckles. Then we should be able to cut veins and tendons in the second leg so that the German colossus falls over.

The resistance only became radicalized when it was recognized that his “moderate” demeanor had no influence on the radical oppression and extermination of Poles and Jews by the German occupiers. In 1943 the Kedyw was founded as an organization for sabotage and acts of diversion. Under her aegis, arson attacks, acts of diversion, liberation of prisoners and even attacks on SS leaders were planned and carried out. The resistance was connected to the Polish government-in-exile via couriers and was supported financially and, to a lesser extent, with weapons. The resistance also carried out large-scale espionage operations in the service of the Allies. In July 1944, for example, a dismantled V2 rocket, which had been captured by Polish resistance fighters, was flown to England by the RAF . During the Warsaw Ghetto uprising in the summer of 1943, fighters from the Home Army tried to organize aid.

Diplomacy and politics

The Polish government found itself in a difficult area of tension within the alliance. Their only capital after the defeat were the Polish troops fighting on the Western Front. Even before the war began, the British government made it clear to the Poles that their guarantees as an ally only extended to the German Reich, not to the Soviet Union. With this step Chamberlain wanted to secure Stalin's neutrality in the war. In 1941, the influence of Poland reached within the alliance by the German invasion of the Soviet Union and the entry into the war the United States a low point. In the Polish-Soviet treaty of July 30, 1941 , the Soviet government declared the Hitler-Stalin Pact null and void, but did not give any assurance that annexed areas would be returned. At the urging of the government, the British secret service SOE concluded an agreement with the Soviet secret police NKVD that cut the number of arms deliveries to the Polish resistance. The AK thus received about 600 tons of material between 1941 and 1944, while the Greek resistance received about 6000 tons and the French resistance about 10,500 tons.

The only real bright spot was the establishment of a Polish army in Russia from the previously deported Polish nationals ( Anders Army ). In October, however, a scandal ensued when the British ambassador in Moscow presented a memorandum that guaranteed the Soviet Union sovereign rights over the Baltic States and the annexed part of Poland. The tense Polish-Soviet relationship was strained even more by problems with the formation of the Anders Army. The soldiers complained of a lack of food and armament. Furthermore, recruits from the formerly Soviet-occupied eastern Poland were not admitted if they were Belarusians, Ukrainians or of Jewish descent. In 1942 the army was transferred to British territory via Persia .

In January 1941, the Soviet Union put together the Union of Polish Patriots (Polish: Związek Patriotów Polskich ; abbreviation: ZPP ), a communist counter-organization to the government in exile. In addition, the Communist Polish Workers' Party with its AL militia had existed in the Polish underground since 1942 . The final break between Stalin and Sikorski was brought about by the announcement of the Katyn massacre by German propaganda agencies in 1943. In September 1939 there were 14,552 Polish prisoners of war , v. a. Officers, soldiers, reservists, police officers and intellectuals were abducted by the Soviet NKVD and have been missing since then. The Polish government believed the German reports and asked the Red Cross to investigate. Of the 4,363 exhumed corpses, 2,730 were identified as Polish soldiers, all of whom were shot in the neck . This clarified the fate of some of the prisoners of war. After this incident, the Soviet Foreign Minister Molotov broke off diplomatic relations with the government-in-exile in April 1943 after Sikorski considered further cooperation to be impossible due to the events. Furthermore, the Soviet leadership intensified its efforts to build up the ZPP as a counter-government and raised the 1st Polish Army under Soviet command under General Zygmunt Berling .

During this time of crisis, the Polish head of state Sikorski died under unexplained circumstances in a plane accident near Gibraltar - and the government-in-exile lost a figure of integration and leadership. The British government described the massacre of the allied officers against their better judgment as a German crime.

Uprising planning

On November 20, 1943, the AK leadership under Bór-Komorowski formulated a first plan to take military action against the German occupiers. The first draft of Aktion Burza (thunderstorm) envisaged the activation of larger partisan units in the countryside, which were to form an independent Polish administration after the Germans were pushed back. In Volhynia this method should be implemented first. However, it managed the local three divisions not the AK to rid the province of the occupiers. They were driven to Polesia and Lublin with great losses . The AK leadership then reconsidered its approach. Along with the advance of the Red Army through Poland, the surrounding AK units should try to conquer the large cities against the retreating Germans and thus take possession of them before the advancing Soviet troops. The method of conquering the cities with an attack from the rural areas alone, however, proved to be a failure. The local AK troops relied on cooperation with the Soviet Army to take the cities. When Vilna was liberated on July 13, 6,000 AK soldiers fought side by side with Soviet troops on the 3rd Belarusian Front . However, just one day later they were forcibly disarmed by the Soviet troops and the officers were arrested.

Another touchstone for the AK leadership was the cooperation with the Soviet Army in the Lublin area . There three divisions of the Home Army fought against the Germans in cooperation with the 2nd Soviet Panzer Army. Lublin lay west of the Curzon Line and, unlike Vilna, was not annexed by the Soviet Union in 1939. Therefore the AK commanders hoped for a friendlier attitude from the Red Army. After the ten days of fighting and the liberation of Lublin, however, all AK troops were again disarmed by the Soviet troops. The same thing was repeated at Lemberg and Ternopil .

These experiences gave an ambivalent picture for the AK leadership. The resistance fighters could only penetrate the cities from the country with the help of the Red Army. Your help was also accepted, but as soon as the enemy was defeated in a region, the AK troops were disarmed. What was remarkable here was the silence of the Western powers, who never objected to Stalin against the disarming of the soldiers of their Polish ally. As a result, the AK command decided to make Warsaw the place of the uprising itself. Here the guerrillas operated themselves out of the city. Furthermore, the uprising was intended to serve as a media-effective demonstration of Polish independence from the Soviet Union. Despite the disarmament, the Soviet side gave the impression that they were friendly to an uprising. Moscow radio broadcast on July 29th an appeal to the citizens of the city to join the fight against the Germans.

The Home Army (AK) was well equipped with around 45,000 fighters in and around Warsaw. Under the command of the communist Armia Ludowa (AL) stood around 1,300 soldiers in Warsaw who joined the uprising. However, there was a lack of weapons, equipment and ammunition. Only every fourth AK fighter had a gun at the start of the uprising. According to calculations by the head of the Warsaw District AK Antoni Chruściel , the resources would only be sufficient for three to four days of offensive combat or two weeks of defensive operations. In the absence of their own supplies, AK fighters often made do with captured German uniforms and steel helmets during the uprising. However, the Polish leadership hoped for air support from the Western Allies and the deployment of Polish parachute troops fighting on the Western Front .

The riot

Elevation of the Home Army

In July 1944, several secret meetings of the AK leadership took place in Warsaw, in which various variants of the uprising were debated. As early as the third week of July, the head of the AK in Poland, General Bór-Komorowski , expressed his conviction - also to the government in exile - that an armed uprising would have to take place in the shortest possible time. However, the lack of ammunition and weapons made it undecided.

In the next few days a series of events took place which increasingly convinced the AK leadership and the government-in-exile that the time had come for an armed uprising. For one, you knew the attack on 20 July on Hitler and the failed coup attempt, on the other hand reports spread about the successful escape of the Allies from the bridgeheads in Normandy. The partial evacuation of German storage rooms and the administrative apparatus of the Germans from Warsaw suggested an imminent withdrawal of the Wehrmacht from Warsaw and an imminent general collapse of Germany.

In addition, the formation of the Lublin Committee - a Polish communist puppet government - by the Soviet Union showed that the Soviet Union wanted to pursue its own political goals despite all protests; On July 29, the communist AL spread the false report that the AK units had left Warsaw. On the same day Moscow Radio broadcast an appeal in Polish, calling on the population to armed uprising: "For Warsaw, which never surrendered but always fought, the hour of struggle has struck!" On July 31, 1944, another meeting of the AK leadership took place in Warsaw, which initially ended with no results; However, when the AK intelligence service reported at 5:30 p.m. on the same day that Soviet tanks had already reached the Praga district east of the Vistula , the head of the AK in Poland, General Bór-Komorowski, announced in agreement with the delegation of the government-in-exile from London to carry out the uprising in Warsaw. All AK units were supposed to strike at the same time against the German occupiers on August 1st at 5:00 p.m.

However, there were isolated firefights between AK units and German troops before the appointed hour, as some of the cells were discovered by the Germans by chance. The element of surprise was therefore only given in a few cases. Furthermore, some units received the order too late or could not fully assemble by 5:00 p.m. The AK cells in the city center suffered less from this deficiency due to the shorter distances in their districts. On the other hand, in contrast to the forces in the surrounding area and the suburbs of the city, they were less armed.

Despite these factors, the insurgents achieved some success. In the course of the first days of the fight, they were able to conquer the 68-meter-high building of the Prudential insurance company as a landmark that could be seen from afar. They also brought the city's central post office and power station under their control. They besieged some important buildings like the switchboard. The resistance fighters also attacked the transit camps that were still in existence as planned and freed numerous concentration camp inmates. By and large, they were able to bring about half of Warsaw to the left of the Vistula under their control. The Polish commander, General Bór-Komorowski, described the events as follows:

“At five o'clock in the afternoon sharp, when they were torn open, thousands of windows were flashing. A hail of bullets fell on the passing Germans from all sides, tore up their marching columns and crashed into the buildings they occupied. The civilians disappeared from the streets in an instant, while the men gathering to attack poured out of the houses. Within fifteen minutes the whole city with its million inhabitants had become a battleground. All traffic stopped. The large junction of Warsaw, immediately behind the German front, with its roads converging north, south, east and west, no longer existed. The battle for the city had broken out. "

However, many strategically important goals remained in the hands of the German occupation forces. The AK fighters did not succeed in clearing the Vistula bridges from German troops. This left the east-west connection through the city open to German troop movements, even if it was constantly threatened by the soldiers of the Home Army. The Germans were also able to repel the attacks on the city's two airports, the university buildings and the police headquarters.

Both sides had thus missed their goals. The Germans could not suppress the uprising and the AK did not have the key positions in the city under their control. After the first days of the fighting, Warsaw resembled a “puzzle” made up of German or Polish controlled sectors; groups on both sides were often isolated and encircled. The Polish resistance fighters lost around 2,500 soldiers on the first day alone, the Germans lost 500 deaths. On August 3, tank units of Hermann Göring's division tried to reopen the road connection to the east for supplies to the eastern front. But they failed because of the rebels' fire. A second attempt by a grenadier regiment of the Wehrmacht also failed. During these operations, Polish civilians were systematically abused by German troops as so-called human shields . But Polish units are also said to have committed war crimes during the first hours of the fighting . The inmates of the German main first aid station in Warsaw are said to have been massacred by AK soldiers, as well as captured Azerbaijani auxiliary troops.

Meanwhile, the German high command had realized that the 20,000-strong Warsaw garrison, of which only 5,000 could be addressed as well-trained and well-equipped combat troops, was unable to put down the uprising. The proposal by the chief of the German Army General Staff, Guderian , to include Warsaw in the Wehrmacht's operational zone and to hold it responsible for suppressing the uprising was rejected by Hitler. Likewise, due to the fighting on the Eastern Front , the High Command of the 9th Army was very reluctant to allow the fight against the insurgents to be imposed on them. Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler received the order to suppress it, and SS-Gruppenführer Heinz Reinefarth commissioned it, since the city commander of Warsaw, Rainer Stahel , was surrounded by insurgents in his headquarters. This initially consisted of a combat group from various intact and partially cut off parts of the garrison, a regiment of the 29th Waffen Grenadier Division of the SS "RONA" under Bronislaw Kaminski , the SS Storm Brigade Dirlewanger , the special association, consisting mainly of prisoners and concentration camp prisoners Bergmann , SS police units from Posen (Poznań) and a 600-man security regiment - which consisted of older men from the staff of the 9th Army who were not fit for the front. He also received support from the Hermann Göring Panzer Division and the 4th Panzer Grenadier Regiment.

Massacre in Wola

Himmler had already given the order days before, in the spirit of Hitler, to kill all non-German residents of Warsaw regardless of age, gender or involvement in the uprising and to level the city to the ground. With this arrangement he wanted to break the resistance of the Polish people against the Nazi rule once and for all. As a result, the attack by the "Kampfgruppe Reinefarth" against the western part of Wola ended with a massacre of the civilian population. It is estimated that the German units killed between 20,000 and 50,000 Polish civilians. The units even avoided taking up combat against the Home Army. The commander of the AK units located in Wola described his losses to soldiers as 20 dead and 40 wounded. Meanwhile, Reinefarth complained to his superiors that the ammunition allotted to him was insufficient to shoot all the civilians captured. The effect of the massacre on the civilian population was not long in coming. Those who could tried to escape to an area of the city controlled by resistance fighters. This strengthened the fighting spirit of the Polish soldiers, but it also laid the foundation for the supply problems and overcrowding behind the resistance positions.

On August 6, the newly arrived Commander-in-Chief Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski restricted the mass murder for tactical reasons. Women, the elderly and children were excluded from the execution order and the execution of the mass murder was shifted from the actual combat units to specially trained task forces behind the front. This was to hide the progress of the murders from the civilian population.

International situation

During the first days of the uprising, the situation of the Red Army had also changed. As part of their western offensive , they were repulsed by the Wehrmacht on August 1st shortly before Warsaw. During the German counter-attack, the leading Soviet tank corps was temporarily cut off and the Red Army deprived of initiative. The Commander-in-Chief of the 1st Belarusian Front Konstantin Rokossovsky saw this only as a short-term failure. A few days later he presented an operation plan in which he announced the capture of Warsaw by August 10th. However, this plan was rejected by higher authorities and the Red Army ordered outside Warsaw to remain in a defensive position. Due to a lack of sources, it is not clear whether the rejection stemmed from the political or military leadership of the Soviet Union.

Since July 30, Sikorski's successor as prime minister, Stanisław Mikołajczyk , was in Moscow in order to dispel diplomatic tensions with the Soviet ally. From August 3, he met Josef Stalin several times . However, he did not promise any support for the uprising. He demanded the recognition of the Communist Lublin Committee and in some remarks made very disparaging remarks about the military capabilities of the insurgents.

Under the pressure of the almost daily requests for help and of General Bór's situation reports from Warsaw, Mikołajczyk also met with representatives of the communist counter-government and made extensive concessions to them regarding the constitution and territorial issues. He was also ready to give the Lublin Committee fourteen seats in a combined government. A few days later, on August 9, Stalin assured him of all support for the Home Army in Warsaw. Thereupon the Polish Prime Minister left Moscow for London believing that he had achieved a decisive foreign policy success. On August 16, however, there was another U-turn in the policy of the Soviet Union. In a letter to Churchill, Stalin declined any assistance to the Polish resistance in Warsaw. He also turned down Roosevelt's request to let US planes stop over at Soviet airports in order to support Warsaw. This had already been demonstrated several times during Operation Frantic . US bombers and fighters landed in the Ukraine and bombed military targets in Hungary , Romania and Poland on the return flight . Due to the hunting escort and the sheer number of US bombers, the chances of success of these missions were far more promising than the previous flights of the Royal Air Force from Italy.

On August 4th, the Allied Air Force started its first flights towards Warsaw. Two planes flew over Warsaw on the night of August 4th, and three more arrived four nights later. Polish, British and Dominion crews dropped weapons, ammunition and supplies. The number of flights, however, remained small and completely inadequate. The only large-scale aid flight with over 100 aircraft was carried out by the Americans on September 18, after several Allied inquiries regarding the use of Soviet airfields were always negative. This was also the last Frantic mission, as Stalin subsequently refused to approve.

Battle for the old town

On August 13, 1944, the Germans began the offensive against the rebels in the old town with 39,000 soldiers . Von dem Bach-Zelewski had chosen this goal in order to restore the railway bridges and thus the supply connection to the 9th Army, which fought on the Eastern Front. They faced 6,000 resistance fighters who were in the a few square kilometers large district with around 100,000 civilians. The German troops proceeded along the streets in the protection of tanks and supported by artillery and air force. This approach failed because of the guerrilla tactics of the insurgents. In particular, the use of Polish snipers was described by German authorities as being particularly effective. It took several days for the Germans to adopt the basic tactics of the insurgents and, instead of moving in the open air, use wall breakthroughs and cellar corridors and mainly the sewer system to move around. In this urban warfare , however, they could hardly bring their numerical superiority in terms of people and heavy weapons to bear. The battle for the old town thus became a battle for every room and every building.

By August 21, the German troops had pushed the AK back to an area of one square kilometer. By that date, they had lost around 2,000 soldiers to death or wounding. The German losses amounted to about 4,000 men by August 26th. On August 31, the AK command in the old town decided to evacuate the remaining fighters and civilians. They withdrew unnoticed by the Germans through the sewer system into the city center controlled by the AK. Since the German troops had concentrated on the old town, the remaining enclaves of the resistance were still relatively untouched. The sight of civilians evacuated from the old town often turned out to be a shock for the local population. Water had been scarce in the disputed neighborhood as the Germans cut the water supply to the whole city. The use of wells was life threatening under artillery fire and bombardment. Efforts by the insurgent administration to maintain medical care failed. As of August 20, anesthetics were no longer available and operations were performed while fully conscious. On August 22nd, the last bread rations were given to AK fighters. Around 25,000 to 30,000 civilians died in the old town. German authorities spoke of around 35,000 interned civilians after the conquest of the quarter. These people awaited deportation for forced labor in the German Reich. After the complete conquest of the old town on September 1, 1944, German troops began shooting wounded civilians and AK soldiers. Only in one case did liberated German prisoners of war, who had been cared for by their Polish opponents in the same hospital as resistance fighters and civilians, prevent mass murder. Furthermore, shootings of captured AK soldiers by German units are also documented during the fighting.

The insurgents of the other districts managed to achieve some local successes during the struggle for the old town. They conquered some of the enclaves in which the occupying forces had stayed, including the PAST telephone company building . As the tallest building in the city, its storming on August 22, 1944 meant a great moral success. The insurgents also tried to establish connections with one another by attacking strategically important buildings. Where the Germans were not cut off themselves, however, they failed, so that the AK still kept a patchwork of isolated areas that did not interact with each other and also hardly communicated. The attempt to smuggle larger reserves into the city via the surrounding forest areas also failed.

Hope and agony

After the fall of the old town, the resistance defended three large areas within the city. The city center was split in two by German troops, but it comprised the AK's strongest district. There were 23,000 soldiers here and the management of the insurgents was most advanced here. There were newspapers, a postal service, a radio station and an in-house weapons production facility, mainly producing hand grenades .

Mokotów was to the south of the center . Since the first days of the uprising, when there had been fighting and shootings by German troops (see “ Pacification of Mokotów ”), it had remained relatively quiet here. An attempt to free the connection to the center failed at the end of August, so that Mokotów remained isolated. In the north of the center, the insurgents held the Żoliborz district, a smaller island of resistance. Here, too, the situation remained comparatively calm until August.

The center became the next target of the German occupiers for two reasons: The road connections to the east ran through it and, due to its size, it was the mainstay of the AK. Von dem Bach-Zelewski began the attack on September 2, 1944. The occupiers advanced along the western bank of the Vistula to cut off the rebels from any approaching Soviet troops. As in the battles for the old town, the tough Polish defense resulted in high losses among the German troops, but the positions against the material superiority could not be held. On September 6th, German troops occupied the power station and tightened the ring around the insurgents. Bór-Komorowski was convinced that the situation was hopeless and on September 8th asked the government in exile to authorize surrender by radio. It was granted to him, but the situation changed drastically a day later. On September 9th, the Soviet Air Force intervened for the first time, bombed German positions and broke German air control within a day. The next day, Rokossowski's attack on the eastern part of Praga began . Thereupon the Polish commander in chief broke off the surrender negotiations with the German commander. On September 14th, the Red Army had the eastern bank of the Vistula completely under control. Poles and Russians were now only a few hundred meters apart.

The AK's morale was strengthened again on September 18. The Soviet Union had now approved a flight for the US Air Force. A total of 110 B-17 Flying Fortresses took off to drop supplies over the city. 104 heavy bombers reached their destination and then landed on the Soviet base in Poltava . Due to the confusing conditions, however, only around 20% of the containers reached the Polish resistance. The US Air Force applied for the continued use of Soviet airfields to carry out the relief flights, but received no permission from the Soviet leadership until the end of the uprising. This remained the only support of the American military for the uprising.

Several days earlier, on September 15, three Polish divisions of Berling had attempted to cross the Vistula north and south of the city. They were supported by Soviet artillery and the Red Air Force. The Red Army combat troops remained passive and Berling himself complained about the lack of pioneer equipment made available for the transition. So only a few soldiers and a small number of heavy weapons could be transferred. After a German counter-offensive, Berling broke off the attack on September 23 and ordered a retreat from the bridgeheads west of the Vistula.

On the same day the German troops captured Żoliborz. After the last AK units there surrendered, there was a massacre of the civilian population. Four days later the AK troops surrendered in Mokotów. By October, the Germans had not been able to break the resistance in the city center. But in view of the hopeless situation of the military and the civilian population, Bór-Komorowski decided to surrender. A ceasefire was agreed on October 1st and went into effect the following day. A few days later, soldiers and civilians were evacuated from Warsaw.

One of the last radio messages from Armia Krajowa from embattled Warsaw in early October 1944, which was intercepted in London, was:

“That is the sacred truth. We have been treated worse than Hitler's satellites, worse than Italy, Romania, Finland. May God the Just pass judgment on the terrible injustice that has befallen the Polish people, and may He punish all those guilty. Our heroes are the soldiers whose only weapon against tanks, planes and artillery was their revolvers and kerosene bottles. Our heroes are the women who cared for the wounded and reported services under bullets, who cooked in bombed-out cellars for children and adults, who brought relief and comforted the dying. Our heroes are the children who played innocently in the smoking ruins. These are the people of Warsaw. A people who live in such bravery are immortal. Because those who died have won, and those who live will continue to fight, will win and again bear witness that Poland will live as long as Poles live. "

consequences

Consequences of war

In a military and political sense, the uprising leadership was unable to achieve its goals. The attempt to drive the occupiers out of their own capital failed. Due to the hopelessness of the military situation, the uprising did not strengthen the position of the government in exile vis-à-vis the Soviet Union, but weakened it, as one had to hope for the help of the Red Army. On the Polish side around 15,000 soldiers died and 25,000 were wounded. Estimates for the civilian population range between 150,000 and 225,000 civilian deaths. This massive suffering of the civilian population made the government-in-exile and the uprising the target of criticism from their own camp as well as from their communist competitors.

The German side could not achieve its initial goals either, as a quick suppression of the uprising failed and the resistance fighters fought against the occupation forces for 63 days. There are two contradicting statements about the losses of the German armed forces. Bach-Zelewski, who was directly responsible for the operation against the uprising, spoke in his report on the uprising of 10,000 dead, 7,000 missing and 9,000 wounded. The files of the staff of the 9th Army recorded 2,000 dead and 7,000 wounded, but these figures do not claim to be exhaustive. The fears of the High Command of the 9th Army, namely a simultaneous Soviet offensive, did not come true. In addition, after the fall of the old town, the supply lines via Warsaw to the eastern front could be restored relatively quickly.

The AK leadership under Bór-Komorowski had tried to a large extent to comply with the requirements of international martial law (open carrying of weapons; armbands as an external identification mark), and therefore claimed combatant status for their soldiers in accordance with the Hague Land Warfare Regulations during the surrender negotiations . The same was agreed for the smaller groups including the communist AL. On August 30, the Western powers also declared the rebels to be members of the Allied forces and threatened reprisals if they were not treated as such. The Wehrmacht therefore granted combatant status to all around 17,000 prisoners since the beginning of the uprising (including members of the communist Armia Ludowa ). In addition, the transport and guarding of fighters and civilians should only be carried out by regular Wehrmacht units, not by the SS. One problem arose from the 2,000 to 3,000 women among the prisoners. Fighting women had not previously been granted combatant status, but according to the surrender negotiations they were now protected by international martial law. At the request of the resistance activists, a passage had been included in the negotiations which enabled women and young people to voluntarily profess civilians. The German prisoner-of-war administration therefore soon began using this provision to forcibly convert women into civilian relationships. Only after the protests of the YMCA and the ICRC did women regain combatant status in December 1944.

Likewise, the resisters had persuaded the German commander von dem Bach-Zelewski to refrain from reprisals against the civilian population. These promises were largely kept towards the AK fighters, but only partially towards the civilians. The Warsaw population was deported from the city via transit camp 121 Pruszków . From here, 100,000 Warsaw residents came to the German Reich as forced laborers after the end of the fighting. Another 60,000 were sent to the Auschwitz , Mauthausen and Ravensbrück concentration camps . After the victory over the Polish forces, Heinrich Himmler ordered the complete destruction of the Polish capital . Until the conquest by the Red Army, German troops occupied themselves with explosions and arson in the city. They mainly focused on culturally significant institutions such as castles, libraries and monuments. Around a quarter of the city's pre-war buildings had been destroyed by the fighting during the uprising. Another third fell victim to the German destruction measures after the surrender. Warsaw was largely uninhabitable at the time of the Red Army conquest.

Further development in Poland

On December 31, 1944, the USSR unilaterally recognized the Lublin Committee as the only legitimate government in Poland. Previously, the Polish Prime Minister Mikołajczyk had been successfully urged by the Western Allies and the Soviet Union to recognize Poland's shift to the West . The Soviet side had not waited for its approval anyway. In October 1944, the NKVD began to “repatriate” the Polish population east of the Curzon Line . As one of the first western observers, George Orwell saw Poland's way into a satellite state dependent on the Soviet Union .

“No, the 'Lublin Regime' is no victory for socialism. It is the reduction of Poland to a vassal state… Woe to those who want to maintain their independent views and policies. ”

“No, the 'Lublin regime' is not a victory for socialism. It is the degradation of Poland to a vassal state. ... those who want to keep their independent goals and policies will suffer hardship. "

This endeavor to suppress the forces not dependent on Moscow was also strongly directed against the former resistance fighters. When the Red Army conquered the western part of the city on January 17, 1945 as part of the Vistula-Oder operation , the order was issued to the advancing NKVD troops to lock up any AK elements that were still present. During the uprising, the Lublin Committee described the AK as a traitor and as infiltrated by ethnic Germans . The leadership of the Home Army was accused of collaborating with Germany.

In post-war Poland these tendencies were quickly promoted with the help of the Soviet security services. In June 1945 a show trial was held in Moscow against the last AK commander after Bór-Komorowski Leopold Okulicki and several leaders of Polish parties. The prison sentences range from four months to ten years. Several convicts died under unexplained circumstances in the Soviet penal camps. The treatment of ordinary soldiers in Poland was also based on this example. Some of them were deported to the Soviet Union or imprisoned in their homeland. In Poland itself, show trials against AK soldiers followed until the 1950s. They were considered exiled soldiers . Furthermore, former resistance fighters were excluded from studying and pursuing a professional career in the communist planned economy. Attempts were also made to capture the memory of the uprising through the politics of the one-party state. In the first post-war years, when Stalinism was enforced in Poland, the uprising was completely ignored by government agencies.

In the wake of the thaw after Stalin's death, these restrictions were relaxed. On August 1, 1957, the uprising was officially commemorated in post-war Poland for the first time. The propaganda continued to criminalize the uprising. However, the government tried to use the uprising to legitimize its own ideology by recognizing the performance of the population and the common soldiers. These tendencies were reinforced in the 1960s when a limited amount of nationalistic tones were added to the memory of the uprising. The first non-state-controlled discussion about the uprising did not take place until the samizdat in the era of the Solidarność movement in the 1980s.

However, the leadership of the Soviet Union kept the Warsaw Uprising in mind. While in the GDR in 1953, in Hungary in 1956, in Czechoslovakia in 1968, Soviet tanks brutally pushed through the Moscow party line, Poland was spared military intervention by the Soviet Union in the crisis years of 1956 , 1970 , 1976 and 1980 . This made it possible for one of the most liberal societies in Eastern Europe to develop in Poland.

Prosecution of war criminals

Persecution of the German war criminals in Warsaw remained low. Bronislaw Kaminski was shot by the Germans on August 28, 1944, allegedly because of his brutal behavior. Oskar Dirlewanger died under unexplained circumstances in French captivity. Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski , who had commanded the fight against the insurgents, was sentenced to life imprisonment in the Federal Republic of Germany in the 1960s - albeit for murders that he had ordered as SS leader before the outbreak of war. The SS officer Heinz Reinefarth became a member of the state parliament of Schleswig-Holstein and mayor of Westerland after the war .

Controversy over the role of the Red Army

The Soviet government said it was not informed before the uprising. On August 16, she stated to the Western powers that “the action in Warsaw is a rash, terrible adventure that is costing the population great sacrifices. This could have been avoided if the Soviet high command had been informed before the start of the Warsaw action and the Poles had maintained contact with them. In view of the situation that has arisen, the Soviet High Command has come to the conclusion that it must distance itself from the Warsaw adventure. "

In the first half of August 1944, the 2nd tank army of the 1st Belarusian Front encountered the resistance of III in the tank battle outside Warsaw in front of Praga . Panzer Corps , which operated together with the IV. SS Panzer Corps . The Soviet troops lost about 500 tanks. As a result of the German counterattack, the number of tanks on the front dropped to 236 by the beginning of August. On her left wing she and the 1st Ukrainian Front formed several bridgeheads over the Vistula, which, however, could not be expanded. On the right wing, the Soviet units only achieved the breakthrough to the Narew at the end of August , which was essential for flank security. At the end of August, the Red Army units went into defense after the 1st Belarusian Front lost 166,808 men in August and early September alone. Only the 1st Polish Army (Berling Army) was deployed to help the insurgents, after the 47th Army of the 1st Belarusian Front had finally captured Praga on September 14th. The Polish divisions crossed the Vistula on September 16 and formed some bridgeheads, which, however, had to be abandoned again on September 23 under strong German pressure. The 1st Polish Army had lost around 3700 soldiers in these days alone. At the same time as the advance, Soviet air support from the 9th Guards Night Bomber Division and the 16th Air Army began and Soviet aircraft flew over the city again after more than five weeks. According to Soviet data, they flew 2,243 missions from September 14 to October 1, supplying Armia Krajowa with 156 grenade launchers, 505 anti-tank rifles, 2,667 firearms, 41,780 grenades, three million cartridges, 113 tons of food and 500 kg of medicine. However, many parachutes did not open, so that many containers smashed on the ground.

Even then, but also especially in the aftermath of the uprising, a controversy arose over the behavior of the Soviet Union with regard to the uprising. The day after the fighting began, the commander of the Polish troops in the West, General Władysław Anders , said in a private letter: “Not only will the Soviets refuse to help our beloved, heroic Warsaw, but they will be with the greatest The joy of watching the blood of our nation seep away to the last drop. ” The following points speak in favor of this view of things and the lack of helpfulness of the Soviet Union:

- At the urging of Great Britain and the United States, Moscow only approved one Allied aid flight, although the United States Air Force was ready for more.

- It was not until September 9, more than a month after the start of the uprising, that Soviet air strikes took place on German positions in Warsaw.

- Stalin decided to shift the focus of the offensive on the Ukrainian fronts towards Slovakia , which was often interpreted as a lack of willingness to help the AK.

- No Soviet combat troops took part in Berling's attempt at relief.

- The NKVD took extremely repressive measures against AK units both before and after the uprising.

- The propaganda of the Soviet-controlled Lublin Committee criminalized the AK while the uprising was still going on.

Due to the lack of access to Soviet archival files, it is difficult to prove a clear stop order for Rokossowski's troops, as is often postulated in popular scientific papers. There is no question that the Armia Krajowa, as the armed arm of the Polish government-in-exile, represented a potential competitor to the Polish Workers' Party (PPR) , which was preferred by Moscow, and the simultaneously existing Lublin Committee. The defeat of the AK made it easier for the Soviet leadership to regulate the political situation in post-war Poland without having to take them into account. In today's public opinion in Poland there is therefore the view that the Soviet Union deliberately let the Polish resistance fighters bleed to death. The US-American historian Gerhard Weinberg described the action of the Wehrmacht and the Red Army during the uprising as "a kind of new edition of the Hitler-Stalin Pact of 1939 against Poland."

In the research volume The German Reich and the Second World War , which is published by the Military History Research Office of the Bundeswehr , the military historian Karl-Heinz Frieser presents evidence that speaks against Stalin's plan to have the Warsaw rebels liquidated by the Wehrmacht. As a result of its rapid advance and the associated supply problems, as well as the massive German resistance, the Red Army was unable to carry out relief attacks for several weeks. The Berling Army , consisting of Polish forces , which fought on the side of the Red Army, tried to build a bridgehead on the west bank of the Vistula, but had to withdraw after almost 5,000 men had been killed within a few days.

The Soviet side also referred to the military situation, which did not allow extensive support for the uprising. High military officials like Marshals Rokossovsky and Zhukov expressed themselves in this regard. In addition, the official Soviet historiography later referred to the alleged refusal of the Armia Krajowa to cooperate with the Red Army. The Poles refused to fight with the Soviet units in the Vistula bridgeheads.

Reception and appreciation

After the fall of the Wall , the political aspects of the uprising were hotly debated in the Polish public. In general, the uprising in the new democracy was rated positively. According to a 1994 poll, a majority of Poles saw the uprising as an important historical event . In the same year, the commemoration of the uprising sparked two foreign policy controversies. The cancellation of Russian President Boris Yeltsin's participation in the commemorations caused displeasure in Poland. In addition, the German President Roman Herzog caused irritation when, in a speech before the celebrations, he mistook the Warsaw uprising for the uprising in the Warsaw ghetto . The German historian Martin Zückert notes that the Warsaw Uprising, together with the Slovak National Uprising, was the “largest uprising against the National Socialist system of rule” in East Central Europe.

Warsaw Uprising Monument

On August 1, 1989, the Warsaw Uprising Monument (Pomnik Powstania Warszawskiego) was unveiled on Krasiński Square in front of the Supreme Court building .

Warsaw Rising Museum

In 2004 the Warsaw Uprising Museum (Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego) opened in the Wola district , in the former tram power station on Przyokopowa and Grzybowska Street . The original building, completely rebuilt after the war, was built in 1908. The house, redesigned according to plans by Wojciech Obtułowicz , was opened as a museum in 2004; the exhibition concept comes from Mirosław Nizio, Jarosław Kłaput and Dariusz Kunowski using the latest multimedia technology. A 35-meter tower represents the symbol of the fighting Poland. In the courtyard a long wall of memory with the names of over 6,000 fighters, who were relatives of their families. T. can still be supplemented. In 2005 a museum chapel was consecrated by Józef Cardinal Glemp in the name of Józef Stanek .

Warsaw Uprising Memorial Day

Every year on the commemoration day of the Warsaw Uprising on August 1st, the nationwide commemoration of the attempted liberation and its victims.

Movies

- Paul Meyer : Conspirators. Documentary. Germany, 2006, 88 min. (Lots of historical recordings. Interviews with women who took part in the uprising as soldiers and were interned in the Emsland camps . Polish soldiers of the Allies reached the Oberlangen camp on April 12, 1945. The film shows also how the experiences from the resistance changed and shaped the whole further life of these women. Paul Meyer, born in 1945, grew up in Emsland and was a lecturer at the Sociological Institute of the University of Freiburg; in 1998 he was a Grimme Prize winner .)

- Christophe Talczewski (TV director): Betrayed and lost. The heroes of the Warsaw uprising. Documentation of historical recordings, Poland, France; 2013, 52 min.

Three dramatized films are known today:

- Andrzej Wajda : The Canal (1956. The film has a documentary effect, but does not have this claim and describes, based on the autobiographical notes of a survivor ( Jerzy Stefan Stawiński ), the fate of a resistance group that has to withdraw into the sewer system below Warsaw.)

- Roman Polański : The Pianist (2002. Based on the drama by Władysław Szpilman . The three Academy Award-winning film also deals with the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and the Warsaw Uprising.)

- Jan Komasa : Warsaw '44 (Original title: Miasto 44 from 2014. The film portrays the effects of the Second World War on the Polish population from the perspective of the youngest combatants in the armed underground.)

See also

- Emslandlager Oberlangen , prisoner of war camp for AK fighters

- Warsaw Uprising Cross

- Powązki cemetery , burial place for many victims of the uprising

Literature (selection)

- Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw uprising in 1944. Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2004, ISBN 3-596-16186-X ( Fischer-Taschenbücher 16186 The time of National Socialism ).

- Bernhard Chiari (ed.): The Polish Home Army. History and myth of the Armia Krajowa since the Second World War. Oldenbourg, Munich 2003, ISBN 3-486-56715-2 ( contributions to military history 57).

- Winston Churchill : The Second World War. Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 2003, ISBN 3-596-16113-4 .

- Jan M. Ciechanowski: The Warsaw Rising of 1944. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge et al. 1974, ISBN 0-521-20203-5 ( Soviet and East European Studies 15), (also: London, Univ., Diss., 1968: The political and ideological background of the Warsaw Rising, 1944. ).

- Norman Davies : Rise of the Lost. The fight for Warsaw 1944. Droemer / Knaur, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-426-27243-1 ( reviews in German-language newspapers, summarized by perlentaucher.de , Lars Jockheck, review in sehepunkte ; PDF; 54 kB).

- Wolfgang Etschmann: The Warsaw Uprising in 1944. Strategic and operational aspects. In: Heeresgeschichtliches Museum Wien (Ed.): From mercenary armies to UN troops. Armies and wars in Austria and Poland from the 17th to the 20th century. Vienna 2011, ISBN 978-3-902551-22-1 .

- Zenon Kliszko : The Warsaw Uprising. Memories and reflections. Translated by Diemut Lötzsch & Roland Lötzsch, Dietz Verlag, Berlin 1969.

- Hanns von Krannhals : The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Bernard & Graefe, Frankfurt am Main 1962 (Reprint: ars una, Neuried 2000, ISBN 3-89391-931-7 ).

- Bernd Martin, Stanisława Lewandowska (ed.): The Warsaw Uprising 1944. German-Polish Publishing House, Warsaw 1999, ISBN 83-86653-09-4 .

- Janusz Piekałkiewicz : Battle for Warsaw. Stalin's betrayal of the Polish Home Army in 1944. 2nd edition. Commemorative edition for the 60th anniversary of the Warsaw Uprising of 1944. Herbig, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-7766-1699-7 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Warsaw Uprising in the catalog of the German National Library

- Warsaw Uprising Museum (Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego; English; in German only opening times etc.)

- Wirtualne Muzeum Powstania Warszawskiego , Virtual Museum of the Warsaw Uprising

- Warsaw Uprising 1944 (English)

- Miasto Ruin - digital reconstruction of the city after the uprising

- Bryla.pl: Photos of the destruction of the western parts of Warsaw by the German occupation forces in autumn 1944

- Speeches on the 50th anniversary of 1994 by the then Polish President Lech Wałęsa and the then Federal President Roman Herzog

- Truth, Memory, Responsibility - The Warsaw Uprising in the Context of German-Polish Post-War History - Topics of the Polish and German Research Perspectives on the Uprising (Conference 2007)

- Warsaw Rising: The Forgotten Soldiers of World War II Educator Guide. (English)

- Publications on the Warsaw Uprising at LitDok East Central Europe / Herder Institute (Marburg)

Individual evidence

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 419.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej : The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 144 ff., Frankfurt / M. 2004, p. 190.

- ↑ a b Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 190.

- ↑ a b Bernd Martin, Stanisława Lewandowska (ed.): Der Warschauer Aufstand 1944. Warsaw 1999, p. 139.

- ^ Norman Davies: God's Playground - A History of Poland. Volume 2. p. 477.

- ^ A b Hans von Krannhals: Der Warsaw Uprising 1944. Frankfurt am Main 1962, p. 214.

- ↑ a b Bernd Martin, Stanisława Lewandowska (ed.): Der Warschauer Aufstand 1944. Warsaw 1999, p. 251.

- ^ Hans von Krannhals: The Warsaw uprising 1944. Frankfurt am Main 1962, p. 120 f.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 649.

- ↑ Klaus J. Bade: Migration in the past and present. P. 378.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising in 1944. Fischer, Frankfurt / M. 2004, p. 23 ff.

- ↑ Wolfgang Benz (Ed.): Dimension of the genocide. The number of Jewish victims of National Socialism. dtv, Munich 1996

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 27.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 25, p. 43.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 32 f.

- ^ Antoni Kuczyński : The deportation of Poland by the Soviet power in World War II. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 33 f.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, pp. 184-188.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising in 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 56.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Boże Igrzysko. Historia Polski. Wydawnictwo Znak, Kraków 2003, p. 925.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Boże Igrzysko. Historia Polski. Wydawnictwo Znak, Kraków 2003, p. 926.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , pp. 30–37.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , pp. 57-59.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 196 ff.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 102.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 3 ff.

- ^ SOE-NKVD agreement and figures: Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising in 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 53.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 42 ff.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 49 f.

- ↑ Numbers on the exhumations: Christian Zentner (Ed.): The Second World War. A lexicon. Vienna, p. 288.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 132, pp. 152-154, p. 183.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 49 ff.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 44 f.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 80 f.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , pp. 85 ff.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 89 ff.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 97 f.

- ↑ a b Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 107.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, pp. 183f, p. 256f.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 419, p. 247.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 103, p. 115.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 110 f.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Boże Igrzysko. Historia Polski. Wydawnictwo Znak, Kraków 2003, pp. 932-934.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 113 ff.

- ↑ a b Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 116 ff.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, pp. 245 f., 262 f.

- ↑ Winston Churchill: The Second World War. P. 951.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 114 f.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 245.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 118.

- ^ Günther Deschner: Warsaw Rising. History of World War II. Pan / Ballantine Books, London 1972, p. 34.

- ^ Günther Deschner: Warsaw Rising. History of World War II. Pan / Ballantine Books, London 1972, p. 45.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 142 f.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 252, p. 249.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising in 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , pp. 118, 120.

- ^ Günther Deschner: Warsaw Rising. History of World War II. Pan / Ballantine Books, London 1972, p. 66.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 249.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 253.

- ^ Hans von Krannhals: The Warsaw uprising 1944. Frankfurt am Main 1962, p. 312.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 123.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, pp. 252 f.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 127 ff.

- ↑ Bernd Martin, Stanisława Lewandowska (ed.): Der Warsaw Uprising 1944. Warsaw 1999, p. 90.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 126 f.

- ↑ Winston Churchill: The Second World War. Pp. 953, 955.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising in 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 130.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising in 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 133.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 137.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 311.

- ^ W. Churchill: The Second World War. P. 952.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 144ff, Frankfurt / M. 2004, p. 144 ff.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 151.

- ↑ a b Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 154 ff.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 326.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 152 f.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , pp. 157-161.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 167 ff.

- ↑ Winston Churchill: The Second World War. P. 957.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, pp. 377, 381.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 383.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 180 ff.

- ↑ Winston Churchill: The Second World War. Scherz, 1948, p. 957. In addition to 15,000 resistance fighters killed by the AK, Churchill gives 10,000 dead, 7,000 missing and 9,000 wounded on the German side, as well as around 200,000 victims among the civilian population of Warsaw.

- ↑ on the civilian dead: Norman Davies: God's Playground - A History of Poland. Volume 2. p. 477.

- ↑ on the German loss figures: Hans von Krannhals: Der Warschauer Aufstand 1944. Frankfurt am Main 1962, p. 120 f.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 502, p. 626, p. 640.

- ^ Rüdiger Overmans : The policy of prisoners of war of the German Reich 1939 to 1945. In: The German Reich and the Second World War . Volume 9/2. Munich 2005, (published by the Military History Research Office ), p. 753 f.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 426.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising in 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 206.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, pp. 436-439.

- ↑ Bernd Martin, Stanisława Lewandowska (ed.): Der Warschauer Aufstand 1944. Warsaw 1999, p. 252, p. 140.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 443 ff.

- ↑ Orwell's article in Time and Tide is quoted in Norman Davies' Rising '44 on p. 442.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 440, p. 457.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, pp. 462 f., 466 ff.

- ↑ Stephen Zaloga : The Polish Army 1939-45. London 1996, p. 30.

- ^ Oskar Dirlewanger in deutsche-und-polen.de ; Retrieved December 31, 2012.

- ↑ Erich von dem Bach-Zelewski. Rundfunk Berlin-Brandenburg, accessed on April 16, 2007 .

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, pp. 547, 548, 332.

- ↑ Quoted from: The history of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union. Volume 4. Deutscher Militärverlag , Berlin 1965, p. 274.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 661.

- ↑ Peter Gosztony: Stalin's Foreign Armies - The Fate of the Non-Soviet Troops in the Red Army 1941–1945. Bonn 1991, p. 145.

- ↑ Bernd Martin, Stanisława Lewandowska (ed.): The Warschauer Aufstand 1944. Warsaw 1999, p. 90 f.

- ↑ The History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union. Volume 4. Deutscher Militärverlag, Berlin 1965, pp. 275-279.

- ↑ Winston Churchill: The Second World War. P. 956 ff.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 348; Original quote in English: “Not only that the Soviets will refuse to help our beloved, heroic Warsaw, but also that they will watch with the greatest pleasure as our nations blood will be drained to the last drop.”

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising in 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , pp. 169, 175.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, pp. 348, 350f, 381, 457, 440 f.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 214.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 314 f.

- ↑ Gerhard L. Steinberg, A World in Arms. The global history of the Second World War , Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1995, p. 749.

- ↑ Karl-Heinz Frieser, Klaus Schmider, Klaus Schönherr: The Eastern Front - The War in the East and on the Side Fronts. In: Military History Research Office (ed.): The German Reich and the Second World War (Volume 8). Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart and Munich 2007, ISBN 9783421055071 .

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, pp. 322f, 421.

- ^ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising in 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 127.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, pp. 322f, 421.

- ↑ The History of the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union. Volume 4. Deutscher Militärverlag, Berlin 1965, pp. 275-278.

- ↑ Włodzimierz Borodziej: The Warsaw Uprising 1944. Fischer, 2001, ISBN 3-10-007806-3 , p. 210 ff.

- ↑ Norman Davies: Rising '44. Pan Books, London 2004, p. 521 ff.

- ↑ Martin Zückert: Slovakia: Resistance to the Tiso regime and National Socialist domination. In: Gerd R. Ueberschär (Hrsg.): Handbook on Resistance to National Socialism and Fascism in Europe 1933/39 to 1945. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2011, ISBN 978-3-598-11767-1 , p. 243 .