Wilhelmplatz (Berlin)

| Wilhelmplatz | |

|---|---|

| Place in Berlin | |

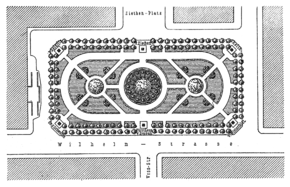

Wilhelmplatz around 1901

looking north; left Wilhelmstrasse, right Zietenplatz |

|

| Basic data | |

| place | Berlin |

| District | center |

| Created | 1749 |

| Confluent streets |

Mohrenstrasse , Wilhelmstrasse , Vossstrasse |

| use | |

| User groups | pedestrian |

| Space design | Green area |

| Technical specifications | |

| Square area | 70 m × 30 m |

The Wilhelmplatz was a place in today's Berlin district of Mitte , which the Wilhelmstrasse was adjacent. During the German Empire , the Weimar Republic and the Nazi dictatorship, the Reich Chancellery , a number of ministries and other striking buildings, most of which were destroyed in the Second World War during the air raids and the Battle of Berlin , were located on it.

Today its outlines are only partially recognizable, as new buildings were erected on the cleared area during the GDR era . The former Wilhelmplatz is part of the Wilhelmstraße history mile, which is used to document the history of the former government district over the centuries using display boards.

In the 18th century

Layout of the square

Wilhelmplatz and Wilhelmstraße were created in the course of the western and southern expansion of Friedrichstadt , which was forced after 1721 and which had been built south of today's street Unter den Linden since 1688 . The engineer and chairman of the municipal building commission, Major Christian Reinhold von Derschau, was in charge of the expansion project . He was advised by the royal senior building director Johann Philipp Gerlach and court building director Johann Friedrich Grael , who were responsible for the architectural design. Under their influence, the building commission decided on binding and narrow guidelines so that a harmonious, holistic cityscape emerged.

Initially, a traditional, small-scale grid system was planned for the new streets to be laid out. From 1732, however, three central north-south axes dominated the planning, which converged radially at the south end in a circular square, the roundabout (today: Mehringplatz ). They were later given the names Wilhelmstrasse , Friedrichstrasse and Lindenstrasse . A royal patent dated July 29, 1734 mentions the construction of a larger square on Wilhelmstrasse among the building projects.

A plan of the royal residence city of Berlin from 1737 shows for the first time a square square that opens in the northern third of Wilhelmsstrasse (as it was written into the 19th century) on the eastern side. Until 1749 it was known as Wilhelms-Markt , after which it was called Wilhelmsplatz or Wilhelmplatz for exactly 200 years . It was named after the Prussian "Soldier King" Friedrich Wilhelm I , who had a strong influence on the expansion and design of Friedrichstadt and, above all, the northern part of Wilhelmstrasse.

Even after early planning, the east side of Wilhelmplatz was connected to a broad connection to Mohrenstrasse , which was initially called "Am Wilhelmplatz" and from the middle of the 19th century was called Zietenplatz . On some historical maps, Zietenplatz is shown as part of Wilhelmplatz or Mohrenstrasse. It was not until the beginning of the 20th century that Mohrenstrasse was extended across Zietenplatz and the cross axis of Wilhelmplatz and has since ended at Wilhelmstrasse.

Edge development

Going back to a request of Friedrich Wilhelm I, around 30 city palaces, deserving representatives of the court, state authorities and the military, were built on the northern Wilhelmstrasse and Wilhelmplatz from the 1730s. The private builders received generous plots of land free of charge and the state bore part of the construction costs. In the literature, however, there is disagreement as to whether this meant a worthwhile honor for those affected or, above all, a financial burden that one would have preferred to avoid. In any case, the builders felt they were obliged to do their part to expand Friedrichstadt in line with their status.

An early pen drawing of the building plans for Wilhelmplatz has survived. It comes from the builder C. H. Horst and can be dated to around 1733. It can be seen that especially magnificent city palaces were intended for the peripheral development of Wilhelmplatz from the beginning. With the exception of a palace originally planned for the northeast side of the square, the buildings first sketched by Horst were actually erected. They were created around the same time from the mid-1730s.

The Palais Marschall on the west side of Wilhelmstrasse (No. 78), probably designed by Johann Philipp Gerlach and C. H. Horst, dominated the new square. It was a focal point on the line of sight of the old Mohrenstrasse. The widening of the connecting road to Wilhelmplatz - which later became Zietenplatz - was evidently deliberately designed so that a comprehensive view of the magnificent palace was made possible from far from the east.

The architect Carl Friedrich Richter built the Palais Schulenburg on the plot at Wilhelmstrasse 77. While Friedrichstadt was otherwise characterized by a continuous house front, a courtyard flanked by side wings was allowed to be placed in front of the main building. However, by aligning the neighboring Marschall Palace on Mohrenstrasse, the Schulenburg Palace was pushed to the northwest corner of Wilhelmplatz and its court of honor remained unrelated to the square. The Palais Schulenburg was to become the official seat of the German Chancellor from 1878 as the Reich Chancellery.

Like almost all properties on the west side of Wilhelmstrasse between Unter den Linden and Leipziger Strasse , Palais Schulenburg and Palais Marschall also had extensive gardens that reached west to what is now Ebertstrasse . Some of them were designed as baroque ornamental gardens, but fruit and vegetables were also grown in them for sale in the Berlin markets. After the conversion of most of the palaces into government buildings in the 19th century, these facilities were referred to as " Ministerial Gardens ".

The first Situated directly on Wilhelmplatz building was from 1737 to Major General Karl Ludwig Steward of Waldburg built Palais Waldenburg . It initially had the house number Wilhelmplatz 7/8 (later 8/9) and was on the north side of the square. At the order of the king, the Order of St. John took over the building after the premature death of the client and had it completed. It is possible that the palace, which was also built by Richter, was based on plans by the royal court architect Jean de Bodt .

It soon became apparent that there were not enough private builders to be found for the plots on northern Wilhelmstrasse. Therefore, Friedrich Wilhelm I had to accept that corporations, guilds, associations and state institutions would also settle there, which otherwise used the southern part of Wilhelmstrasse. A gold and silver factory, which was built from 1735 to 1737 according to plans by Gerlach, set up shop on the southwest corner of Wilhelmplatz (Wilhelmstrasse 79). The manufactory was owned by the Potsdam military orphanage , which was supposed to be financed from the proceeds. Another building belonged to it on the south side of Wilhelmplatz (No. 2). The building at Wilhelmstrasse 79 was extended to the neighboring property (house number 80) and Vossstrasse (house number 35) between 1869 and 1876. The Prussian Minister of Commerce and (from 1878) also the Prussian Minister of Public Works resided in the building complex . During the Weimar Republic and the Nazi era , the Reich Ministry of Transport and part of the Reichsbahn administration were housed there.

Since 1727 the Jews of Berlin were forbidden to buy houses in the city. Nevertheless, in 1735 the Jewish community was assigned the southern corner plot of land on Wilhelmstrasse (Wilhelmplatz 1) with the condition that a building be erected on it. However, due to financial difficulties, the community was unable to do so in the following three decades. Between 1761 and 1764, with special permission from King Friedrich II. Veitel Heine Ephraim , chairman of the Jewish community, acquired the manufactory building at Wilhelmplatz 2 on the south side and the aforementioned corner property as private property, as well as the gold and silver manufacture for hereditary lease.

The statues of the Prussian military

After the end of the Seven Years' War in 1763, the plan developed to erect statues of the Prussian generals who had fallen in the war on Wilhelmplatz. The result was initially four free-standing individual figures made of marble of Field Marshal Kurt Christoph Graf von Schwerin (sculptors: François Gaspard Adam and Sigisbert François Michel , erected in 1769), Field Marshal Hans Karl von Winterfeldt ( Johann David Räntz and Johann Lorenz Wilhelm Räntz , 1777), General Friedrich Wilhelm von Seydlitz ( Jean-Pierre Antoine Tassaert , 1781) and Field Marshal General James Keith (Jean-Pierre Antoine Tassaert, 1786). They depicted the military in a more conventional way. Schwerin and Winterfeldt were depicted in an antique style with Roman clothes and weapons, Seydlitz and Keith in contemporary uniforms.

In 1794 and 1828, two more statues were erected on Wilhelmplatz, which were originally intended for other Berlin city squares. They came from the important Berlin sculptor Johann Gottfried Schadow . The sculptures were depictions of Hans Joachim von Zieten and Leopold I , Prince of Anhalt-Dessau, called "Alter Dessauer". The statue of Zieten was intended for the Dönhoffplatz , which is also in Berlin-Mitte, which no longer exists today , the Anhalt-Dessau monument had initially stood at the southwest corner of the Lustgarten since 1800 and then, according to the plans of Karl Friedrich Schinkel (of the two town squares newly designed) implemented. Together, the six sculptures shaped Wilhelmplatz until the middle of the 20th century.

Because of the fragility of the material, on the advice of Christian Daniel Rauch , bronze versions of the marble sculptures were made by the sculptor August Kiß from 1857 . They replace the originals, which should be placed in closed rooms. However, Kiß completely redesigned Schwerin and Winterfeldt's sculptures and freed them from their ancient appearance. After changing locations, the originals from Wilhelmplatz found accommodation in the small domed hall of the Bode Museum in 1904 .

Both marble originals and bronze versions survived the Second World War, but remained hidden from the public for decades in various depots. Only in the course of a Prussian renaissance in the GDR since the 1980s was a re-erection discussed. On the occasion of the 750th anniversary of Berlin in 1987, the marble originals were transferred back to the small domed hall of the Bode Museum. The bronze versions were placed in front of the Altes Museum in the Lustgarten at the same time , but were put back into storage in the 1990s.

After the turn of the millennium, the Berlin Schadow Society planned to re-erect the statues of the Prussian military in the vicinity of their historical locations. The bronze copies of the Zieten and Anhalt-Dessau monuments were rebuilt in 2003 and 2005 on the subway island on the transverse axis of the former Wilhelmplatz. The remaining four bronze statues found a new location on the neighboring Zietenplatz in September 2009 , after the reconstruction, which began in 2005, was completed. The statues have been a listed building as a whole since 2011.

Bronze statue of Prince Leopold I of Anhalt-Dessau

Monument to Leopold I, base inscription based on a design by Schadow

Bronze statue of Field Marshal Hans Karl von Winterfeldt

Winterfeldt's marble statue from 1777, after an engraving from 1778

Until 1871

Redesign by Schinkel and new residents

Schinkel submitted his proposal to relocate the Anhalt-Dessau monument to Wilhelmplatz as part of the redesign of the square that he was responsible for in 1826 - the most extensive change in the area to date. He assigned the memorials new locations at the ends of the two square diagonals and the transverse axis. He also gave the area the appearance of a park with lawns, linden trees and an oval walkway that touched the edges of the square.

Up until the end of the 19th century, the development on the edge of Wilhelmplatz was partly extended by additions and partly replaced by larger new buildings. The multiple change of owner and user of the city palace also led to its new name.

In the early 1790s, the Schulenburg palace briefly belonged to Sophie von Dönhoff , the morganatic wife of King Friedrich Wilhelm II. In 1796, it came into the possession of Prince Anton Radziwill and was henceforth known as the "Palais Radziwill". During the Napoleonic occupation of Berlin, the French city commander resided in it. In the following decades the Palais Radziwill was one of the leading Berlin salons , which aroused both sensation and dislike in Protestant Prussia due to the Catholicism of the owners. Accompanied by his own compositions, Radziwill, a great admirer of Goethe , had Faust I premiered in the house theater of the Palais in 1819/1820 .

With the dissolution of the Order of St. John in the course of the Prussian reforms , the Order Palace fell to the state in 1811. King Friedrich Wilhelm III. transferred it to his third son Carl von Prussia on the occasion of his engagement in 1826 . The Ordenspalais became the “Palais Prinz Karl” with the new numbering Wilhelmplatz 8/9. Karl had Friedrich August Stüler redesign the interior of the baroque building on the basis of Schinkel's plans from 1827–1828, redesign the exterior in a classical style and build a right side building. Until his death in 1865, Stüler was responsible for the redesign of a number of buildings on Wilhelmstrasse.

The former Marschall Palace , which had already changed hands several times in the 18th century, was acquired by the Secret Minister of State Otto Carl Friedrich von Voss in 1800 . It was then called “Palais Voss”. Achim and Bettina von Arnim lived in an associated garden house between 1811 and 1814 . In a letter to Goethe, the latter described her life situation there with the words: "I live here in a paradise!"

Beginnings of the government district Wilhelmstrasse

As early as the end of the 18th century, it became clear that Prussian nobles were often financially unable to maintain the stately palaces in the north of Wilhelmstrasse. So there were individual sales to representatives of the aspiring bourgeoisie, who partly used the buildings for commercial purposes, for example as manufactories, publishing houses or by renting out parts. In addition, “real” town houses were built early on on smaller plots in the area.

In a countermovement in the 1790s, the state of Prussia also began to acquire land and buildings on Wilhelmstrasse and use them for public purposes. It was intended to preserve the appearance of Wilhelmplatz and the surrounding area as a “showcase” of the aristocratic Prussian tradition. The administrative and spatial separation of court and government, which began in the second half of the 18th century, increased after the wars of liberation . Independent ministries and authorities began to emerge. Since they were supposed to keep in close contact with one another, an initially Prussian, then Reich German government district emerged in the course of the 19th century, which became known under the metonym "Wilhelmstrasse". Envoys from German or foreign countries soon followed, renting vacant apartments in the area. In the 1840s, for example, the embassies of Belgium, Mecklenburg-Strelitz and Württemberg had their headquarters on Wilhelmplatz.

The first house on Wilhelmplatz to fulfill Prussian government functions was the Ordenspalais. The building housed departments of the Prussian General Staff from 1817 and also offices of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs from 1820. Both authorities had to move in 1827 when the Ordenspalais passed to Prince Karl. The Foreign Ministry then moved into the southern corner building at Wilhelmstrasse 61 / Wilhelmplatz 1, which was acquired by the Ephraim heirs.

In 1844, the Prussian state also took over the building of the gold and silver factory, which had been heavily modified by renovations in 1823 (the production of which was only carried out in rear extensions) at Wilhelmstrasse 79. From 1848 the newly established Ministry of Trade, Industry and Public Works resided here . The building was rebuilt again in 1854/55 by Stüler, adding another storey.

In the German Empire

New government buildings around the square

After the establishment of the German Empire in 1871, Wilhelmstrasse moved into the political center of a major European power. The redesign of the existing Prussian and the establishment of new imperial offices, authorities and committees resulted in a need for representative official buildings. The creation of office and living space for state secretaries and civil servants also contributed to a new (re) building boom on Wilhelmplatz. His surroundings were given a sober, businesslike character that left no room for shops or restaurants. Until the Nazi era , Wilhelmplatz remained one of the few centrally located squares in Berlin where there were no street cafes.

The Federal Foreign Office , initially created in 1870 as an institution of the North German Confederation , briefly settled on the south side of Wilhelmplatz. It took over the corner building Wilhelmstrasse 61 / Wilhelmplatz 1, which had previously been used by the Prussian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The move took place in 1877 after the demolition of this building and the new building (1874–1877) according to plans by Wilhelm Neumann , executed by Richard Wolffenstein . Using an eclectic style that was based on the external form of the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, the architects combined ornamental elements of the Renaissance and Classicism. At the same time, the Wilhelmplatz 2 building, which was acquired in 1873 and which was converted inside, was incorporated.

After the parts of the Foreign Office located on the southern Wilhelmplatz moved to the northern area of Wilhelmstrasse (No. 75/76), the corner building at Wilhelmstrasse 61 / Wilhelmplatz 1 was used from 1882 by the Reich Treasury , the supreme financial authority of the German Empire created in 1879. In the neighboring building to the east, Wilhelmplatz 2, the Reich Insurance Office was located from 1887 to 1894 , but afterwards it was also occupied by the Reich Treasury. In 1909 the house at Wilhelmplatz 2 was completely redesigned and optically matched to corner building no. As early as 1904, the entire Wilhelmstrasse 61 / Wilhelmplatz 1/2 complex was expanded to the south by adding Wilhelmstrasse 60.

On the opposite side of the street, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Public Works (Wilhelmstrasse 79), which has been residing in the former gold and silver factory since 1848, also expanded. Two extensions at Wilhelmstrasse 80 and the (newly created) Vossstrasse 35 were connected to the complex in 1869/1870 and 1875/1876, respectively. In 1878 the wing of the building became the headquarters of the outsourced new Ministry for Public Works , which was primarily responsible for building construction and railways in Prussia. Other buildings in Leipziger Strasse (No. 125) and Vossstrasse (No. 34) were attached from 1892 to 1894 and 1908, respectively.

Reich Chancellor Otto von Bismarck , however, had the greatest influence on the further development of the area with his decision in favor of the seat of the Reich Chancellery , which was newly created in 1878 . Instead of moving into a building that Neumann had actually built for this purpose in 1872–1874 at Wilhelmstraße 74, Bismarck chose the former Palais Radziwill (Wilhelmstraße 77) on the northwest corner of Wilhelmplatz. Bismarck had bought the building in order to prevent private investors from securing houses on Wilhelmsstrasse. The executive branch's ever-expanding space requirements should be met within walking distance of the existing facilities. A law stipulated in 1874 that the orbitant purchase price of two million marks was covered by French reparations payments for the war of 1870/1871 . The building was "inaugurated" for its new purpose in June / July 1878 at the Berlin Congress , which took place within its walls.

Other changes

In addition to the consequences of the growth of the government district, three urban developments in particular radically changed the appearance of Wilhelmplatz between 1871 and 1914.

The building and grounds of Palais Voss became the property of the Deutsche Baugesellschaft in 1871 . For reasons of speculation, they developed the plan to demolish the palace and develop the entire site for a new cul-de-sac to Königgrätzer Strasse, today's Ebertstrasse . The small plots to be identified on both sides of the new traffic artery were to be sold at a profit to investors who were able to build commercial buildings there. The newly created Vossstraße, named after the last property owner and initially private, met the transverse axis of Wilhelmplatz and connected with Zietenplatz and Mohrenstraße to form a west-east axis that extended between Königgrätzer Straße and Hausvogteiplatz . This axis was actually opened up to road traffic at the beginning of the 20th century, but inevitably had to cut through and disrupt the Schinkelsche Park.

Two new city palaces were built on the vacated site at the northern corner of Vossstrasse and Wilhelmstrasse: the industrialist August Julius Albert Borsig had the Berlin architect Richard Lucae build the “Palais Borsig” in the style of the Italian High Renaissance on the property at Voßstrasse 1 in 1875–1877 . The surrounding, angular site at Vossstrasse 2 and Wilhelmstrasse 78 was built with the “Palais Pleß” for Hans Heinrich Fürst von Pless according to plans by the architect Gabriel-Hippolyte Destailleur and French models from the 18th century. The numerous towering chimneys allegedly earned this building, which was demolished again in 1913, the contemporary nickname “Chimney Sweep Academy”.

The most striking new building on Wilhelmplatz in the 19th century, however, was the Grandhotel Kaiserhof, built between 1873 and 1875 according to plans by the architects Hude & Hennicke . In order to create space for the huge complex, the "Berliner Hotelgesellschaft" had eleven properties since 1872 at Wilhelmplatz (No. 3 and 5), Zietenplatz (No. 1–3 and 5) and Mohrenstrasse (No. 4) and the Mauerstraße (No. 56-59) and thus acquired an entire district and demolished the existing buildings. On the southeast side of Wilhelmplatz, the previously closed perimeter buildings were broken up and a new connection was created between Mauerstrasse and Wilhelmstrasse under the name Kaiserhofstrasse. The “Kaiserhof” was lifted even more out of its surroundings by releasing adjacent buildings.

Although its main entrance was on Zietenplatz, the luxuriously appointed hotel officially had the address Wilhelmplatz 3–5. Only a few days after its opening, to which Kaiser Wilhelm I also appeared, the hotel burned down on October 10, 1875. In time for the Berlin Congress in 1878, at which numerous diplomats were to stay in the luxury hotel, it reopened its doors. Until the opening of the “ Hotel Adlon ” on Pariser Platz in 1907, the “Kaiserhof” in Berlin set the standard for modern, sophisticated hostel accommodation. To the east of the “Kaiserhof” stood the Trinity Church .

The third major change on Wilhelmplatz before the First World War brought the expansion of the underground network from 1905 to develop the historic city center, initially to the Spittelmarkt . In the course of this expansion of a west-east line, the underground station "Kaiserhof" (today " Mohrenstrasse ") opened in 1908 under Wilhelmplatz and Zietenplatz . The actually planned name "Wilhelmplatz" had to be dispensed with because there was already a station of the same name in Charlottenburg (today 's Richard-Wagner-Platz underground station ). A double street connecting Zietenplatz and Wilhelmstraße flanked an oval island in the middle of Wilhelmplatz, on which the western subway entrance was located. This intervention cut up Schinkel's arrangement of seats, but left the six bronze statues of the military in their traditional places. However, it was no longer they, but the entrance to the subway designed by Alfred Grenander and, above all, its striking pergola framing that shaped the perception of Wilhelmplatz.

The growing architectural influence of the neo-renaissance on Wilhelmplatz was also evident from 1894 on the building designed by the Royal Agricultural Inspector Hermann Ditmar on the southern corner of Zietenplatz and Wilhelmplatz 6 (today Mohrenstrasse 66). The property in question had already been structurally developed in the 1730s, had changed hands several times and was used from 1840 by the “ Kur- und Neumärkische Haupt-Ritterschafts-Direktion ”, a loan fund to support run-down aristocratic estates. The new building opposite the “Kaiserhof” was built for them from 1892 to 1894. The reference to the model of Florentine city palaces for a newly built bank was understood as a recognition of the origins of the modern money economy in late medieval northern Italy.

Soon after the death of Prince Carl of Prussia in 1883, expansion work began on the now aged former Ordenspalais. At right angles to the Stülerer annex from the 1820s, a new court marshal's building was built by the architect Reinhold Persius by 1885. In addition, the wing of the palace facing Wilhelmstrasse was extended and balconies added. Since Carl's son Friedrich Karl died almost two years after his father, his son Prince Friedrich Leopold took over the inheritance at Wilhelmplatz in 1885 . The building was named after him "Palais Prinz Leopold".

The Knighthood Directorate and the Court Marshal's building are the only parts of the historical peripheral buildings on Wilhelmplatz that still exist. Both buildings are now part of the Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs complex and are under monument protection .

Changes in the Weimar Republic

During the November Revolution of 1918, the Reich Chancellery developed into a major location for the dramatic events in Berlin. Here the last Imperial Chancellor, Prince Max von Baden, negotiated the handover of official business with Friedrich Ebert on November 9th, and the latter concluded the Ebert-Groener Pact at the same place on the evening of November 10th during telephone negotiations with the First Quartermaster General of the Army . In the following, sometimes chaotic two months, demonstrations by the various groups marched through Wilhelmstrasse, claiming political power and trying to enforce it in part by force.

The consolidation of the Weimar Republic in 1919 paved the way for a revision of the administrative order in the German Reich. Not only was responsibility rearranged between the Reich and Prussia, but the central government also acquired new powers. The transition from a monarchical to a republican state also changed the area around Wilhelmplatz.

In contrast to these structural changes, the building boom on Wilhelmplatz had already subsided since the beginning of the First World War. Almost all of the land was now state-owned or had been occupied with stately new buildings in the previous decades. Although new authorities and ministries were established from 1919 onwards, these occupied the buildings of the imperial era, which were often unchanged from the outside, or had to be housed in the surrounding streets due to the increasing lack of space.

After the conversion of the previous Reich offices into ministries, two Reich ministries resided next to the Reich Chancellor on Wilhelmplatz: In the wing of the houses on the south side of the square, Wilhelmstrasse 61 / Wilhelmplatz 1, there was initially the Reich Treasury , which was incorporated into the Reich Finance Ministry in 1923 , whose headquarters were then on Wilhelmplatz . The opposite side of the street, Wilhelmstrasse 79/80, was occupied by the newly created Reich Ministry of Transport after the Prussian Ministry of Public Works was dissolved in 1921 . From this , the privatized Reichsbahngesellschaft was spun off in 1924 due to conditions arising from the German reparation obligations ( Dawes Plan ) . She took over the corner building of the former gold and silver factory and the houses on Vossstrasse that were attached during the imperial era. In addition, a residential building built in the 1880s was attached there (No. 33), which is the only pre-war building on Vossstraße that still exists today.

After the First World War, the Prussian Treasury and the House of Hohenzollern fought over ownership of the Prince Leopold Palace, whose namesake had lifelong right to live in the building. In 1919 it was briefly considered as the official residence of the newly elected Reich President. Because of the high purchase price, the poor structural condition and safety concerns, Ebert decided against the largely empty building. Instead, Wilhelmstrasse 73 was converted into the Reich President's Palace. But the Palais on Wilhelmplatz was finally rented by the State of Prussia - as the seat for the new United Press Department of the Reich government belonging to the Foreign Office . From then on, it kept in touch with the media in the capital with daily press conferences in the garden hall of the property.

The increasing lack of space on Wilhelmstrasse spurred plans in 1926 to acquire the now aging, deficit-working hotel "Kaiserhof" and to convert it into the new seat of the Reich Ministry of Finance. However, nothing came of the purchase. The only opportunity to expand the office space on Wilhelmplatz was a vacant lot at Wilhelmstrasse 78, which had existed since the Palais Pleß was demolished in 1913. The Reich Chancellery had secured the property of the neighboring area, but a planned extension had been postponed because of the World War. In view of the financial bottlenecks that burdened the young democracy, the valuable building plot lay fallow for years after 1918 and only housed a few barracks to accommodate the guard of the Reich Chancellery.

The growing tasks of the Reich Chancellery had led to an expansion of the service areas in the Palais Radziwill since 1919 - at the expense of the premises used for personal and representative purposes. Therefore, in 1927, plans matured to outsource all official functions to an extension (also called component II) on the property at Wilhelmstrasse 78. A design by architects Eduard Jobst Siedler and Robert Kisch won a much-noticed competition . They convinced the jurors with the attempt to connect the stylistically different neighboring buildings - the baroque palace of the Reich Chancellery and the neo-renaissance building Palais Borsig - with a sober, factual intermediate link and thus "close Wilhelmplatz in terms of urban development", as the award committee judged was called. A striking tower section in the right half of the building also emphasized the modern architectural demands. After a partly lively public controversy about the supposed aesthetic break with tradition, the building was erected in a slightly modified form between 1928 and 1930.

Another building project on Wilhelmplatz was of course largely hidden from the public. The background was the planning of an underground north-south connection for the Berlin S-Bahn between the “Potsdamer Bahnhof” (today “ Potsdamer Platz ”) and the “ Stettiner Bahnhof ” via the “ Friedrichstrasse ” station. Instead of the later east-west loop under Pariser Platz and the “Unter den Linden” S-Bahn station (since 2009: “Brandenburger Tor”), a more southern variant was originally planned with tunneling under the garden of the Reich Chancellery. A separate S-Bahn station “Wilhelmplatz” was to be built with a connection to the existing U-Bahn station “Kaiserhof”, which had to be partially under the property at Wilhelmstrasse 78. In order not to cause any later construction conflicts with the extension of the Reich Chancellery, the shell of the station tunnel was created at this point from 1927, but was never used later. Its discovery by Soviet soldiers in the spring of 1945 could have contributed to the emergence of rumors and speculations about mysterious Nazi tunnels and their function in the Wilhelmstrasse and Vossstrasse area.

National Socialism and World War II

The National Socialists sought proximity to Wilhelmplatz at an early stage, thereby underscoring their claim to take power in Germany. During his visits to the capital of the Reich, from 1930 Adolf Hitler regularly stayed at the Kaiserhof , which, due to the right-wing national stance of its operators, was a focal point for ethnic groups. From August 29, 1932, the NSDAP leadership resided continuously in the hotel; one floor served as a provisional party headquarters. Significantly, Joseph Goebbels gave his diary notes from this period published in book form in 1934, Vom Kaiserhof zur Reichskanzlei .

On the evening of January 30, 1933, torch-carrying formations of SA , SS and steel helmets marched from the Brandenburg Gate via Pariser Platz and Wilhelmstrasse to Wilhelmplatz to celebrate Hitler's appointment as Chancellor . Hitler showed himself to the cheering crowd at a window of the settler extension of the Reich Chancellery, his new official seat. Similar marches took place in the same place in the following years, always on Hitler's birthday on April 20th. The draping of buildings with large-format swastika flags, which soon became common , also changed the external character of Wilhelmplatz. This “politicization” was a new phenomenon in the history of the government district.

At the latest, Hitler's assumption of the office of Reich President after Hindenburg's death in 1934 revealed the centralization in the National Socialist state. This also increased the importance of Wilhelmstrasse. The apparatus of the old and new ministries and authorities, but also of the powerful party offices, was geared even more towards the Reich Chancellery on Wilhelmplatz, where Hitler often resolved disputes between the various institutions.

In March 1933, the newly founded Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda under Goebbels moved into the old Prince Leopold Palace on the north side of the square, which had previously been used by the press department of the Reich government. The interior furnishings, which were still made by Schinkel, were partially destroyed during renovation work. By 1940, an extensive extension in the style of National Socialist architecture was built according to plans by Karl Reichle . This extended to Mauerstrasse, where the new main entrance to the ministry was also located.

Reichle integrated the Hofmarschallhaus, built in 1885 on the northeast corner of Wilhelmplatz, into the wing of the building, but changed its front by adding a loggia and dividing the facade with three arched axes. The building of the palace on Wilhelmstrasse was extended from 1938, while the Schinkel style was retained, but the balconies that were added in the 1880s were no longer available. The Reichle building, which has been preserved in contrast to Palais Prinz Leopold, is now a listed building and, after renovation, functions as the seat of the Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs between 1997 and 2001 . Its main entrance (today: Wilhelmstrasse 49) is in the Hofmarschallhaus, which was redesigned by Reichle.

In 1933 the Borsig Palace was rented by the state and made available to Vice Chancellor Franz von Papen as his official residence. Purchased by the Reich at the beginning of 1934, the building was used by officials of the presidential chancellery as well as the leadership of the SA, who moved from Munich to Berlin after the “ Röhm Putsch ”, after Papen's office was soon abolished . The General Inspector for German Roads, Fritz Todt , also had his official residence here for a time.

For the purposes of the National Socialists, the old structure of Wilhelmplatz proved to be a hindrance. On the occasion of the Olympic Games in 1936 , the area was redesigned at the instigation of Goebbels. The aim was to create space for marches and to hold mass events on the leaders' balcony , which Albert Speer had added in 1935 to the first floor of the extension to the Reich Chancellery. This construction measure took place in the context of a general renovation of the Reich Chancellery, which the architect Paul Ludwig Troost had carried out according to Hitler's wishes. Among other things, the Borsig Palace was attached to the Reich Chancellery and the interior was redesigned.

When the Wilhelmplatz was changed, the lawns and a large part of the linden trees were removed. The bronze statues of the Prussian military were all placed on the east side of the square, where a row of linden trees was preserved; the grids surrounding the statues since the Schinkel period fell victim to the redesign. The square was fortified with stone slabs and large-scale mosaic patterns, on which blocks of people could easily be aligned, and was delimited by high, two-armed lighting fixtures. The subway entrance has been greatly reduced in size, the pergola edging has been removed and the surrounding street has been adapted. In addition to the Tempelhofer Feld and the Lustgarten , the image of Nazi mass events in Berlin is primarily linked to this converted Wilhelmplatz: “The central square of the government district, where the Reich Chancellery and the Propaganda Ministry were located, had become a place of homage for Adolf Hitler . "

As the most monumental new building in the area around Wilhelmplatz, the New Reich Chancellery designed by Speer was erected along Vossstrasse , also known as component III of the Reich Chancellery. Its dimensions and elaborate furnishings were intended to impress foreign visitors in particular and underline the German Reich's claim to supremacy in Europe. Preparations for the building had already begun in 1934 with the purchase of land on Vossstrasse, which was to be widened to a thoroughfare at the same time. Hitler declared the new building to be politically necessary and made no secret of his contempt for the two older parts of the Reich Chancellery: The Palais Radziwill was built with an "overloaded nobility" in the imperial era, but "rotten" and "decayed" in the Weimar Republic ". (In fact, the building had been completely renovated in 1932 and was in excellent condition.) On the outside, component II made “the impression of a warehouse or municipal fire station”, inside it resembled a “sanatorium for lung patients”. On the occasion of the inauguration of the New Reich Chancellery in January 1939, the Nazi propaganda claimed that the construction time was only nine months. That was a double misleading, because on the one hand the construction work had already started in 1937, on the other hand the building was only partially completed at the inauguration and was largely dysfunctional. Further construction work dragged on until 1943, but was not completed.

Although there was a smaller entrance on Vossstrasse, the New Reich Chancellery faced Wilhelmplatz. From there it was possible to drive ( large double portal ) into a 68 m long courtyard behind the Siedler-Bau and Palais Borsig , at the end of which the main portal was located. The courtyard was furnished with two statues by Arno Breker (The Party and the Wehrmacht) and a lighting system designed by Speer. The left part of the settler building had been broken through for the passage.

In the mid-1930s, an extensive bunker system was built on Wilhelmplatz, invisible to the public. Part of the bunker system intended for Hitler ( pre- bunker ) was planned as part of the renovation of the old Reich Chancellery and placed under the new hall building on its north wing in 1935/1936. Between 1943 and autumn 1944, under the leadership of Reich Building Councilor Carl Piepenburg, a second bunker building, significantly lower down and provided with stronger outer walls, was added to the west, in which Hitler's personal rooms were located. However, individual parts of this bunker were not completed. The largest bunker complex was under the New Reich Chancellery and, with 91 individual bunkers, stretched under the entire building wing. A part of these bunkers on Vossstraße was opened to the public from 1940. Other bunker systems in the area around Wilhelmplatz were located south of the Kaiserhof underground station (for the SA leadership) and under the Reich Ministry of Transport.

In the more than 300 air raids on Berlin during the Second World War , numerous buildings in the government district were damaged or destroyed. The heavy attacks in February / March 1945 caused major damage. Most of the buildings on Wilhelmplatz were not destroyed until the Battle of Berlin in the last weeks of the war. From April 21, 1945, the bombardment by Soviet artillery was concentrated on the area around the Reich Chancellery. While in newer buildings (such as the New Reich Chancellery) at least the outer walls remained partially in place, some of the older palaces from the 18th century turned out to be less resistant. They were almost completely destroyed. This applied to the old building of the Reich Chancellery and to the Prince Leopold Palace . The Hotel Kaiserhof was largely destroyed in an air raid. The Reich Ministry of Transport and the Reich Ministry of Finance also suffered considerable damage in the last days of the war.

During the last months of the war, Wilhelmplatz was transformed into a desert of rubble, interspersed with barricades and barracks of the defenders of the government district. Hitler's secretary Traudl Junge describes her impressions on April 22, 1945 in her memoir: “Wilhelmplatz looks desolate. The imperial court has collapsed like a house of cards, its ruins almost reaching as far as the Reich Chancellery. The only symbol left of the Propaganda Ministry is the white facade on the bare square. "

After the clearing work and demolition in the post-war period, only the court marshal's building and the knighthood management remained of the former peripheral development of Wilhelmplatz . The bronze statues of the Prussian military survived the general destruction: They were dismantled after an air raid in January 1944 and stored in a depot.

Historical peripheral development until 1945

- Wilhelmplatz 1/2; Wilhelmstrasse 61: Reich Ministry of Finance , destroyed

- Wilhelmplatz 3–5: Hotel Kaiserhof , destroyed

- Wilhelmplatz 6, today Mohrenstrasse 66: Knighthood Directorate , inventory

- Wilhelmplatz 7: building rented by the USA for their Berlin embassy until 1931 , destroyed

- Wilhelmplatz 8: Hofmarschallhaus, existing building

- Wilhelmplatz 9: Ordenspalais , Propaganda Ministry , destroyed. The Wilhelmstrasse 49 extension is now the seat of the Federal Ministry of Labor and Social Affairs

- Wilhelmstraße 79 / Voßstraße 33–35: Reichsbahn building , destroyed

- Voßstraße 1: Palais Borsig , integrated into the building of the New Reich Chancellery in 1938/39 , destroyed

- Wilhelmstraße 77/78, Vossstraße 2: (Old) Reich Chancellery with extension, destroyed

View in February 1945 of the Zietenplatz towards the entrance of the largely destroyed Hotel Kaiserhof ; the rubble was later removed

The Borsig Palace (right) and the Reichsbahn building (left) at the beginning of Vossstrasse were demolished after the war, in 1946

In contrast to the neighboring buildings, the Knighthood Directorate, today Mohrenstrasse 66, was restored after the war; it served as the GDR guest house from 1949, 1951

From Wilhelmplatz to Thälmannplatz

The buildings on the edge of Wilhelmplatz, which were heavily damaged in the Second World War and especially during the street fighting of the last days of the war, and the remaining ruins were removed by 1949 . After the remnants of the Prince Leopold Palace had been demolished, the north side of the square almost doubled in size and now extended to the Reichle building of the Propaganda Ministry. The former building of the Knighthood Directorate was restored despite massive war damage and from then on served as the guest house of the GDR government. The German People's Council was housed in the Hofmarschallhaus until 1949 , then the Central Council of the National Front of the GDR.

In August 1949, decided to East Berlin magistrate , the former Wilhelmplatz by Ernst Thalmann in Thälmannplatz rename. The Kaiserhof underground station, which was destroyed in the war, was given the same name after its restoration . At the public ceremony for the renaming of the square on November 30, 1949 , Walter Ulbricht declared : "A war-mongering square has become a symbol of peace-loving, rebuilding Berlin."

Apart from the Central Council of the National Front, no important state institution was located on Thälmannplatz during the GDR era. After the popular uprising of June 17, 1953, and completely after the construction of the Berlin Wall on August 13, 1961, Thälmannplatz, located near the sector border with West Berlin, became a peripheral location.

Between 1974 and 1978 the southern half of Thälmannplatz with the embassy of Czechoslovakia in the GDR was built over. The building by architects Vera Machonina, Vladimir Machonin and Klaus Pätzmann was created as a solitaire in an environment that was still largely free of buildings after the war damage. Accordingly, there was enough space available to erect a massive structure on a base area of 48 by 48 meters, which in no way tied in with the architecture of the historical peripheral development of Wilhelmplatz. The reinforced concrete frame construction with curtain walls and the dominant materials steel, concrete and glass shows the influences of brutalism . The main floor emerges from the cubature with twice the floor height above an aerial floor at street level, which takes up the driveway of the house . Above are three more floors that accommodate the office space. The facades show a horizontal structure made of strips of material in which natural stone slabs and dark-tinted glass alternate. The building now serves as the embassy of the Czech Republic in Germany.

On the northern half of the square, prefabricated residential buildings, particularly of the WBS 70 type , were built in the 1980s . This meant that the old outlines of the square were only partially recognizable. In 1987 Thälmannplatz was also officially deleted from the street register and the house numbers were added to Otto-Grotewohl-Straße (since 1992 Wilhelmstraße again).

The square was given neither a new name nor its old name back.

literature

- Laurenz Demps : Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse. A topography of Prussian-German power. 3rd revised edition. Links, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-86153-228-X .

- Helmut Engel , Wolfgang Ribbe (Ed.): History Mile Wilhelmstrasse. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-05-003058-5 .

- Christoph Neubauer: City guide through Hitler's Berlin. Yesterday Today. Flashback-Medienverlag, Frankfurt (Oder) 2010, ISBN 978-3-9813977-0-3 .

- Hans Wilderotter: Everyday Power. Berlin Wilhelmstrasse. A publication of the historical commission, Berlin. Jovis, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-931321-14-2 .

Web links

-

Wilhelmplatz . In: Street name lexicon of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein

- Wilhelms market . In: Luise.

- Thälmannplatz . In: Luise.

- 3D animations of all buildings on Wilhelmplatz (archived version)

Individual evidence

- ^ Laurenz Demps : Berlin Wilhelmstrasse. A topography of Prussian-German power . Links, Berlin 1994, ISBN 3-86153-080-5 , pp. 12-16, 18, 26-32.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 14-16, 33.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 12-14, 18-20.

- ^ Wilhelmplatz . In: Street name lexicon of the Luisenstädtischer Bildungsverein

- ^ Mende (Ed.): All Berlin streets and squares. (Articles "Zietenplatz" and "Mohrenstrasse")

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 23-25, 32, 45-49.

- ^ Laurenz Demps: Berlin Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 21-23.

- ↑ Martin Engel: The Forum Fridricianum and the monumental residence places of the 18th century. (PDF) Art history dissertation , Freie Universität Berlin 2001, pp. 42–43.

- ^ Laurenz Demps: Berlin Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 21-23, 42.

- ↑ Engel: Das Forum Fridricianum (PDF) pp. 42–43.

- ^ Laurenz Demps: Berlin Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 20, 42.

- ^ Laurenz Demps: Berlin Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 25, 45.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 30, 42, 49-50.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 23-25, 32.

- ^ Laurenz Demps: Berlin Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 19, 23-25.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , p. 32, 56-60.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 66–68.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 68–70.

- ↑ a b Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 69–70.

- ^ Rainer L. Hein: Prussian generals return to the center . In: Berliner Morgenpost , June 14, 2008.

- ^ Rainer L. Hein: Generals for the Zietenplatz . In: Berliner Morgenpost , January 11, 2009.

- ↑ State monument list (see current PDF version)

- ^ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , p. 106.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 63–66, 79–81, 308. Beate Agnes Schmidt: Music in Goethe's 'Faust'. Dramaturgy, reception and performance practice . Studio-Verlag, Sinzig 2006, ISBN 3-89564-122-7 , pp. 203-214.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 94-102, 311.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 308–309, quotation p. 103.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 72–74, 108.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 84-102. Wolfgang Ribbe: Wilhelmstrasse in the change of the political systems. Prussia - Empire - Weimar Republic - National Socialism . In: Helmut Engel, Wolfgang Ribbe (ed.): Geschichtsmeile Wilhelmstrasse . Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 1997, ISBN 3-05-003058-5 , pp. 21–39, here pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Hans Wilderotter: Everyday life of power. Berlin Wilhelmstrasse. A publication of the historical commission Berlin . Jovis, Berlin 1998, ISBN 3-931321-14-2 , p. 245. Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , p. 86.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 91–94, 98–102.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 125-134.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 128-134.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 132-134.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , p. 140.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstraße , pp. 135-138, 144-150.

- ^ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse. Pp. 139-141.

- ^ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse. Pp. 140-143.

- ^ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse. Pp. 122-124.

- ^ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse. P. 124.

- ^ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse. Pp. 162-163.

- ↑ Berlin address books from 1841

- ↑ Landesdenkmalamt Berlin (Ed.): Monuments in Berlin. Mitte district. Mitte district . Imhof, Petersberg 2003, p. 357.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps : Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 165–168.

- ↑ a b c Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 180-184.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 171–176.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 170-171, 181-184, 199.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 199–203, quoted on p. 202.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , pp. 199–203.

- ↑ Laurenz Demps: Berlin-Wilhelmstrasse , p. 198.

- ^ Joseph Goebbels: From the Imperial Court to the Reich Chancellery. A historical representation in diary sheets . Rather, Munich 1934.

- ^ Landesdenkmalamt (Ed.): Monuments in Mitte , p. 156.

- ^ Adolf Hitler: The Reich Chancellery . In: The new Reich Chancellery. Architect Albert Speer . Eher, Munich 1940, pp. 7–8, citations p. 7.

- ↑ Traudl Junge (with Melissa Müller): Until the last hour. Hitler's secretary tells her life . Claasen, Munich 2002, p. 179.

- ↑ Maoz Azaryahu: From Wilhelm place to Thälmannplatz. Political symbols in public life in the GDR . From the Hebrew by Kerstin Amrani and Alma Mandelbaum. Bleicher, Gerlingen 1991, ISBN 3-88350-458-0 , pp. 153-164, quotation p. 154.

- ↑ Messages. Czech Republic. On: BauNetz.de (on March 23, 2010).

Coordinates: 52 ° 30 '41.9 " N , 13 ° 23' 2.4" E