Assam: Difference between revisions

| [pending revision] | [pending revision] |

| Line 343: | Line 343: | ||

==See also== |

==See also== |

||

[[Image:wanda_blau.JPG|thumb|right|180px|Orchids are abundantly found in Assam; a variety - Bhatou Phul or [[Vanda]] coerulea, the '''Blue Orchid'']] |

|||

{{columns |width=200px |gap=5px |

{{columns |width=200px |gap=5px |

||

|col1 = |

|col1 = |

||

Revision as of 16:18, 29 June 2007

Assam

Assam | |

|---|---|

state | |

| • Rank | 16th |

| Population | |

| • Total | 26,655,528 |

| • Rank | 14th |

| Website | assamgovt.nic.in |

| † Assam had a legislature since 1937 | |

Assam (Assamese: অসম Ôxôm) is a north eastern state of India with its capital at Dispur, a suburb of the city Guwahati. Located south of the eastern Himalayas, Assam comprises the Brahmaputra and the Barak river valleys and the Karbi Anglong and the North Cachar Hills. With an area of 78,438 km² Assam currently is almost equivalent to the size of Ireland or Austria. Assam is surrounded by the rest of the Seven Sister States: Arunachal Pradesh, Nagaland, Manipur, Mizoram, Tripura and Meghalaya. These states are connected to the rest of India via a narrow strip in West Bengal called the "Chicken's Neck".[1] Assam also shares international borders with Bhutan and Bangladesh; and cultures, peoples and climate with South-East Asia—important elements in India's Look East Policy.

Assam is known for Assam tea, petroleum resources, Assam silk and for its rich biodiversity. It has successfully conserved the one-horned Indian rhinoceros from near extinction in Kaziranga, the tiger in Manas and provides one of the last wild habitats for the Asian elephant. It is increasingly becoming a popular destination for wild-life tourism and notably Kaziranga and Manas are both World Heritage Sites.[2] Assam was also known for its Sal tree forests and forest products, much depleted now. A land of high rainfall, Assam is endowed with lush greenery and the mighty river Brahmaputra, whose tributaries and oxbow lakes provide the region with a unique hydro-geomorphic and aesthetic environment.

Etymology

Assam was referred to as Pragjyotishpura in the Mahabharata; and Kamarupa in the 1st millennium. After the disintegration of Kamarupa in the 12th century the Ahom kingdom was founded in the 13th century by Sukaphaa, a Shan prince, which unified the polity and lasted for the next 600 years. Though the precise etymology of Assam is unclear, the academic consensus is that the name is associated with the Ahom kingdom (originally called the Kindom of Assam).[3]

The British province after 1838 and the Indian state after 1947 came to be known as Assam. On February 27, 2006 the Government of Assam started a process to change the name of the state to Asom,[4] a controversial move that has been opposed by peoples and political organizations.[5]

Physical geography

Geologically, as per the plate techtonics, Assam is in the eastern most projection of the Indian Plate, where it is thrusting underneath the Eurasian Plate creating a subduction zone.[6] It is postulated that due to the northeasterly movement of the Indian plate, the sediment layers of an ancient geocyncline called Tethys (in between Indian and Eurasian Plates) have been pushed upwardly to form the Himalayas. It is estimated that the height of the Himalayas is increasing around 4 cm each year. Therefore, Assam possesses a unique geomorphic environment, with plain areas, dissected hills of the South Indian Plateau system and with the Himalayas all around its north, north-east and east.

Geomorphic studies conclude that the Brahmaputra is a paleo-river, older than the Himalayas, which often crosses higher altitudes in the Himalayas and sustaining its flow by eroding at a greater pace than the increase in the height of the mountain range. The heights of the surrounding regions are still increasing to form steep gorges in Arunachal. Entering Assam, the Brahmaputra becomes a braided river and along with its tributaries, creates the flood plain of the Brahmaputra Valley[7] The Brahmaputra Valley in Assam is approximately 80 to 100 km wide and almost 1000 km long and the width of the river itself is 16 km at many places.

The hills of Karbi Anglong and North Cachar and those in and around Guwahati and North Guwahati (along with the Khasi and Garo Hills) are originally parts of the South Indian Plateau system.[7] These are eroded and dissected by the numerous rivers in the region. Average height of these hills in Assam varies from 300 to 400mt. The southern Barak Valley is separated by the Karbi Anglong and North Cachar Hills from the Brahmaputra Valley in Assam. The Barak originates from the Barail Range in the border areas of Assam, Nagaland and Manipur and flowing through the district of Cachar, it confluences with the Brahmaputra in Bangladesh. Barak Valley in Assam is a small valley with an average width and length of approximately 40 to 50 km.

Assam is endowed with petroleum, natural gas, coal, limestone and many other minor minerals such as magnetic quartzite, kaolin, sillimanites, clay and feldspar[8]. A small quantity of iron ore is also available in western parts of Assam.[8] The Upper Assam districts are the major reserves of oil and gas. Petroleum was discovered in Assam in 1889. A recent USGS estimate shows approximately 399 million barrels of oil, 1178 billion cubic feet of gas and 67 million barrels of natural gas liquids in Assam Geologic Province. [9]

With the 'Tropical Monsoon Rainforest Climate', Assam is a temperate region and experiences heavy rainfall and high humidity.[7] [10] Winter lasts from late October to late February. The minimum temperature is 6 to 8 degrees Celsius. Nights and early mornings are foggy, and rain is scanty. Summer starts in mid May, accompanied by high humidity and rainfall. The maximum temperature is 35 to 38 degrees Celsius, but the frequent rain reduces this. The peak of the monsoons is during June. Thunderstorms known as Bordoicila are frequent during the afternoons. Spring and Autumn with moderate temperatures and modest rainfall are the most comfortable seasons.

Assam is one of the richest biodiversity zones in the world. There are number of tropical rainforests[11] in Assam. Moreover, there are riverine grasslands[12], bamboo[13] orchards and numerous wetland[14] ecosystems. Many of these areas have been protected by developing national parks and reserved forests. The Kaziranga and Manas are the two World Heritage Sites. The Kaziranga is the home for the rare Indian Rhinoceros, while Manas is a tiger sanctuary. Moreover, there are numerous other valuable and rare wildlife and plant species available in Assam. Few of the rarest species are the Golden Langur (Trachypithecus geei), the White-winged Wood Duck or Deuhnah (Cairina scultulata), the Golden Cat, etc. The Hoolock Gibbon in Assam is the only ape found in South Asia. Assam is also known for orchids.[15]

The region is also prone to natural disasters. High rainfall, deforestation, and other factors have resulted in annual floods that cause widespread loss of life, livelihood and property. The region is also prone to earthquakes. Mild tremors are familiar, and strong earthquakes are rare. There have been three strong earthquakes: in 1869 the bank of the Barak sank by 15 ft; 1897 (8.1 on the Richter scale); and 1950 (8.6).

History

Pre-history and myths

Assam and adjoining regions have evidence of human settlement from all periods of the Stone ages. That the known hills settlements belonged to earlier periods may suggest that the valleys were populated later, or it may reflect sampling bias due to mountainous areas being more likely to remain less disturbed over long stretches of time.

The earliest ruler according to legend was Mahiranga (sanskritized form of the Tibeto-Burman name Mairang). He was followed by others in his line: Hatak, Sambar, Ratna and Ghatak. Naraka removed this line of rulers and established his own dynasty. The Naraka king mentioned at various places in Kalika Purana, Mahabharata and Ramayana covering a wide period of time were probably different rulers from the same dynasty. Kalika Purana, a Sanskrit text compiled in Assam in the 9th and 10th century, mentions that the last of the Naraka-bhauma rulers, Narak, was slain by Krishna. His son Bhagadatta, mentioned in the Mahabharata, fought for the Kauravas in the battle of Kurushetra with an army of kiratas, chinas and dwellers of the eastern coast. Later rulers of Kamarupa frequently drew their lineage from the Naraka rulers.

Ancient and medieval Assam

Ancient Assam was known as Kamarupa and was ruled by many powerful dynasties. The Varman dynasty (350-650AD) and the Xalostombho dynasty led Kamrupa as a strong ancient kingdom. During the rule of the greatest of the Varman kings, Bhaskarvarman (600-650AD), a contemporary of Harshavardhana of Kanauj, the Chinese traveler Xuan Zang visited the region and recorded his travels. Other dynasties that ruled the region belonged to the Indo-Tibetan groups, such as the Kacharis and Chutias.

Two later kingdoms left the biggest impact in the region. The Ahoms, a Tai group, ruled eastern Assam for nearly 600 years (1228-1826). The Koch, a Tibeto-Burmese, established their sovereignty in 1510 which later extended to western Assam and northern Bengal. The Koch kingdom later split into two. The western kingdom became a vassal of the Moghuls whereas the eastern kingdom became an Ahom satellite state.

Despite numerous invasions from the west, mostly by Muslim rulers, no western power ruled Assam until the arrival of the British. The most successful invader was Mir Jumla, a governor of Aurangzeb, who briefly occupied Garhgaon the then capital of the Ahoms (1662-1663). But he found it difficult to control the people, who made guerrilla attacks on his forces, forcing them to leave the region. Attempt by the Moghuls under the command of Raja Ram Singh resulted in victory for the Ahoms at Saraighat (1671) under the Ahom general Lachit Borphukan.

British Assam

Ahom palace intrigue, and political turmoil due to the Moamoria rebellion, aided the expansionist Burmese ruler of Ava to invade Assam and install a puppet king in 1821. With the Burmese having reached the doorsteps of the East India Company's borders, the First Anglo-Burmese War ensued, in which Assam was one of the sectors. The war ended with the Treaty of Yandaboo[16] in 1826, which saw the East India Company take control of the Lower Assam and install Purander Singh as king of an independent Upper Assam in 1833. This arrangement only lasted until 1838 when the British annexed most of independent Assam, annexing the remainder the following year.

Under British administration, Assam was made a part of the British Indian province called the Bengal Presidency with its capital at Calcutta. Sometime about 1905-1912, Assam was separated and with parts of Bengal, a separate province of Eastern Bengal and Assam was established, with Dhaka as the capital.

At the time of independence of India, it consisted of the original Ahom kingdom, the present-day Arunachal Pradesh (North East Frontier Agency), Naga Hills, original Kachari kingdom, Lushai Hills, and Garo, Khasi and Jaintia Hills. Of the Assam province on the eve of Independence, Sylhet chose to join Pakistan in a referendum; and the two princely states Manipur and Tripura became Group C provinces. The capital was Shillong.

Post British period

In the Post British period since 1947, unfortunately economic indexes of the region, which were above average before independence, began to fall compared to the rest of the country. Separatist and militant groups began forming along ethnic lines, and demands for autonomy and sovereignty grew, resulting in the new states of Nagaland, Meghalaya and Mizoram in the 1960s and 1970s. The capital of Assam, which was in Shillong in present Meghalaya, had to be moved to Dispur, now a part of an expanding Guwahati. After the Indo-China war in 1962, Arunachal Pradesh was also separated out.

At the turn of the last century (1900s), people from present-day Bangladesh migrated to Assam. The British tea planters imported labour from central India to work in the estates adding to the demographic canvas. In 1961, the Government of Assam passed legislation making the use of Assamese language compulsory. The legislation resulted in widespread protest in Barak Valley, particularly by the Bengali speaking majority. Coming under intense pressure, the Government withdrew the legislation.

In the 1980s the Brahmaputra valley saw a six-year Assam Agitation [17] that began non-violently but became increasingly violent. The movement was triggered by the discovery of a sudden rise in registered voters on electoral rolls. The movement tried to force the government to identify and deport foreigners who, the natives maintained, are illegally inundating the land from neighbouring Bangladesh and changing the demographics, gradually pushing the indigenous Assamese into a minority. The agitation ended after an accord between its leaders and the Union Government. Most of the accord remains unimplemented, causing simmering discontent. However, political parties have increasingly used the Bangladeshi card as a vote bank rather than addressing the concerns of the Assamese populace. Former Governor of Assam (Retd) Lt Gen. S. K. Sinha reported explicitly on the burning problem in his report to the Government of India.[18]

Like indigenous peoples in other parts of the world, the many ethnic groups of this region struggle to maintain their cultural heritage resulting into active autonomy movements in the Bodo and Karbi dominated regions in the 1980s and 1990s. At the same time, added by economic stagnation, high aspirations for development and failure of public policies in the region in almost all the fronts, the period experienced the growth of armed secessionist groups like United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA) [17] and National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB). In November 1990, the Government of India deployed the Indian army to control the situation, leading to claims of human rights violations. The Indian army deployment has now been institutionalised under a "Unified Command". The low-intensity military conflict has been continuing for more than a decade now without an end to the insurgency at sight. In recent times, ethnicity based militant groups have also mushroomed (UPDS, DHD, KLO, HPCD etc.) leading to violent inter-ethnic conflicts (e.g. the Hmar-Dimasa conflict).

History of Assam Tea

The East India Company began setting up poppy plantations in Lower Assam for the Opium trade to China. This changed with the confirmed discovery in 1834 of Camellia sinensis, tea plants, growing in the wild in Assam. The first chests containing leaves of wild tea were sent to Britain at the end of 1836. Botanical expeditions proved Upper Assam to be a more favourable area for tea plants than Lower Assam. British companies were allowed to rent land in Assam from 1839. Profitability for tea growers remained elusive and the first and largest actor, The Assam Company, didn't pay dividends on its stocks until 1853.

The various stages in growing and making tea were learnt through a lengthy trial and error process. Imported Chinese labour proved invaluable in spreading knowledge about every step in growing and processing tea. Early tea plantations were also hindered by the hostility of native Assamese and as a result the British recruited labour from other parts of India. The native jungle was unhealthy for non-natives and had to be cleared for the plantations. The British also persisted for decades in trying to grow the Chinese tea variety (which they thought of as proper tea) or a Chinese-Assamese hybrid, before accepting that the native tea variety Camellia assamica was more suitable for local agriculture and also tasted just as well if not better.

The first tea boom took off in 1861 when investors were allowed to own land in Assam. The British had hoped to undercut the Chinese tea trade by eliminating the middlemen and through more efficient production but found this difficult due to extremely low Chinese labour costs. The second boom began when William Jackson invented the first efficient mechanical tea roller in the early 1870s. He formed an association with Britannia Iron Works and out of it grew Messrs Marshall Sons & Co., Ltd which for a long time dominated the tea machinery manufacturing business. Further important inventions by William Jackson led to a thorough mechanization of the tea industry in Assam. The cost of a finished tea product went down from 11d per pound of tea in 1872 to a mere 3 shillings a pound in 1913. While India's tea exports to Britain soared to 220 million lbs in 1899, Chinese trade with Britain collapsed to 16 million lbs. Nowadays the only step that still requires considerable manual labour is the plucking of the delicate tea leaves.

Despite outmaneuvring the Chinese, Indian tea labour remained exploited and working under poor conditions. In face of greater government interference the tea growers formed The Indian Tea Association in 1888 to lobby for the continued status quo. The organisation was very successful in this, and even after India's independence conditions have only slowly improved.[19]

Administrative divisions

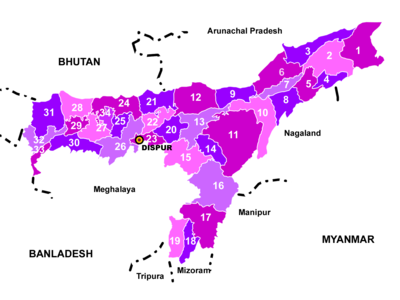

Assam is divided into 27 administrative districts.[20] More than half of these districts were carved out during 80s and 90s from original 1. Lakhimpur, 2. Jorhat, 3. Karbi Anglong, 4. Darrang, 5. Nagaon, 6. Kamrup, 7. Goalpara, 8. North Cachar and 9. Cachar districts, delineated by the British. Earlier, during 70s, Dibrugarh was separated out from original Lakhimpur district.

These districts are further sub-divided into 49 'Sub-divisions' or Mohkuma.[20] Every district is administered from a district head quarter with the office of the District Collector, District Magistrate, Office of the District Panchayat and usually with a district court.

The districts are delineated on the basis of the features such as the rivers, hills, forests, etc and majority of the newly constituted districts are sub-divisions of the earlier districts. For the present districts of Assam and their location, refer the attached map.

The local governance system is organised under the jila-parishad (District Panchayat) for a district, panchayat for group of or individual rural areas and under the urban local bodies for the towns and cities. Presently there are 2489 village panchayats covering 26247 villages in Assam.[21] The 'town-committee' or nagar-xomiti for small towns, 'municipal board' or pouro-xobha for medium towns and municipal corporation or pouro-nigom for the cities consist of the urban local bodies.

For the revenue purposes, the districts are divided into revenue circles and mouzas; for the development projects, the districts are divided into 219 'development-blocks' and for law and order these are divided into 206 police stations or thana.[21]

Demographics

As per the Census of India 2001, total population of Assam was 26.66 million with 4.91 million households.[22] Higher population concentration was recorded in the districts of Kamrup, Nagaon, Sonitpur, Barpeta, Dhubri, Darang and Cachar. The Technical Group on Population Projection constituted by the National Commission on Population (India) in 2006 has estimated Assam's population at 28.67 million in 2006 and has estimated it to be 30.57 million by 2011, 34.18 million by 2021 and 35.60 million by 2026.[23]

In 2001, the census recorded literacy in Assam at 63.30 percent with male literacy at 71.30 and female at 54.60 percents. Urbanisation rate was recorded at 12.90 percent.[24]

Growth of population in Assam has experienced a very high trajectory since the mid-decades of the 20th century. Population grew steadily from 3.29 million in 1901 to 6.70 million in 1941, while during the later decades it has increased unprecedentedly to 14.63 million in 1971 and 22.41 million in 1991 to reach the present level.[22] Particularly, the growth in the western and southern districts of Assam was of extreme high in nature. This is mostly attributable to the rapid infiltration of population from the then East Bengal (East Pakistan) or Bangladesh.[25][18]

Assam has very many ethnic communities. The People of India project (POI) has studied 115 communities. Of these, 79 (69%) identify themselves regionally, 22 (19%) locally, and 3 trans-nationally. The earliest settlers were Austroasiatic.[26] The Tibeto-Burman speakers entered the region from the north, northeast and southeast at various times in the prehistorical and historical times. The Indo-Aryan speakers entered from the Gangetic plains in the west, again at various times in the past.

Forty-five languages are spoken by different communities, including three major language families: Austroasiatic (5), Sino-Tibetan (24) and Indo-European (12). Three of the spoken languages do not fall in these families. There is a high degree of bilingualism.

Assam has communities representing many different religions, but the major religion is Hinduism (63.13%). Islam (32.43%) has the largest proportional population among all Indian states except Jammu and Kashmir. Other significant religions (4.44%) include Animism (followed by many ethno-cultural groups), Buddhism (by ethnic communities like the Khamti, Phake, Aito etc.) and Sikhism (followed by communities in Borkhola, in Nagaon).

Languages

Assamese and Bodo are the major indigenous and official languages of the state while Bengali holds official status in particular districts in the Barak Valley.

Traditionally Assamese was the language of the commons (of mixed origin - Bodo, Khasi, Sanskrit, Magadhan Prakrit) of the ancient kingdoms such as Kamrupa and medieval kingdoms of Kamatapur, Kachari, Cuteeya, Borahi, Ahom and Koch. Traces of the language can be found in many poems in Charyapada written by Luipa, Sarahapa, etc during the period of the Xalostombho / Salastambha dynasty (7th/8th century AD) of Kamarupa Kingdom. Modern Kamrupi dialect is the remnant of this language. Moreover, Assamese in its ancient and medieval form was used by almost every ethno-cultural group as the lingua-franca of the region. Probably the language was then required for needed economic integration and was also probably spread through the stronger and larger politico-economic systems such as that of the ancient Kamrupa. Traditional and localised forms of this language still exist in Nagaland, Arunachal Pradesh, North Bengal, Kacar (Cachar) and in Southern Assam (similarities with Chittagonian language in present-day Bangladesh exists). The form used in the upper Assam was enriched by contributions from many eastern immigrations such as of those of Tai-Ahoms and others beginning from 13th century onwards.

Linguistically modern Assamese traces its roots to the version developed by the American Missionaries based on the local form in practice near Xiwoxagor/Sibsagar district. Assamese or Oxomeeya (as called in Assam) is a rich language due to its hybrid nature with its unique characteristics of pronunciation and softness. Assamese literature is one of the richest. The constitution of India recognises it as a major language of Republic of India.

Bodo is the ancient language of Assam and is mother of majority of the present day languages and dialects within the state and also in surrounding areas. Looking at the spatial distribution patterns of related ethno-cultural groups and their cultural traits and also phenomenon such as of naming all the major rivers in the North East Region with original Bodo words (e.g. Dihing, Dibru, Dihong, D/Tista, Dikrai, etc) it is understood that it was the most important language in the North East India in the ancient times, where history yet haven't opened its gates. Bodo is presently spoken largely in the Lower Assam areas mostly under the areas of Bodo Territorial Council. During past few decades (after years of neglect) it is fortunate that Bodo as a language is getting attention and much care is being taken for development of Bodo literature.

Assam is also rich with several native languages such as Mishing, Karbi, Dimaca, Rabha, Tiwa, etc of Tibeto-Burman origin and are closely related to Bodo. There are also small groups of people in different part of Assam with languages such as Tai-Phake, Tai-Aiton, Tai-Khamti, etc related to Tai-group of languages of Southern China and South East Asia. The Tai-Ahom language (brought by Sukaphaa and his followers) is now fortunately getting attentions for wide-spread research after centuries long care and preservation by the Bailungs (traditional priests), which is no more a spoken language for commons today. There are also small groups of people speaking Manipuri, Khasi, Garo, Hmar, Kuki, etc in different parts of Assam.

In the past century migration of Bengalis to the medieval kingdom of Kacar (of Kocaries) in the Barak Valley has led to their majority, prompting the government of Assam to include Bengali as the official language in the Barak Valley districts.

Tradition and culture

Assamese culture is traditionally a hybrid one, developed due to cultural assimilation of different ethno-cultural groups under various politico-economic systems in different periods of pre-history and history. The roots of the culture go back to almost two thousand years when the first cultural assimilation took place with Austro-Asiatic and Tibeto-Burman as the major components.[27]

Thereafter, western migrations such as those of various branches of Mediterraneans, Indo-scythians /Irano-scythians and Nordics along with (or in the form of) the mixed northern Indians (the ancient cultural mix already present in northern Indian states such as Magadha) have enriched the aboriginal culture and under certain stronger politico-economic systems, Sanskritisation and Hinduisation intensified and became prominent.[27] Such an assimilated culture therefore carries many elements of source cultures, of which exact roots are difficult to trace and are matter of research. However, in each of the elements of Assamese culture, i.e. language, traditional crafts, performing arts, festivity and beliefs either local elements or the local elements in a Hinduised / Sanskritised forms are always present.[28]

The major milestones in evolution of Assamese culture are:

- Assimilation under the great dynasties of Pragjyotisha-Kamrupa for almost 700 years (Varman dynasty for 300 years, Mlechchha dynasty for 200 years and Pala dynasty for another 200 years) in the first millennium AD.[27]

- Advent of Ahom dynasty in the 13th century AD and establishment of the Ahom politico-eonomic system and cultural assimilation for next 600 years.[27]

- Assimilation under the Koch Kingdom (15th-16th century AD) of western Assam and Kachari Kingdom (12th-18th century AD) of central and southern Assam.[27]

- Vaishnava Movement led by Srimanta Sankardeva (Xonkordeu) and its contribution and cultural changes.

With a strong base of tradition and history, the modern Assamese culture is greatly influenced by various events those took place in the British Assam and in the Post-British Era. The language was standardised by the American Baptist Missionaries such as Nathan Brown, Dr. Miles Bronson and local pundits such as Hemchandra Barua with the form available in the Sibsagar (Xiwoxagor) District (the nerve centre of the Ahom politico-economic system). A renewed Sanskritisation was increasingly adopted for developing Assamese language and grammar. A new wave of Western and northern Indian influence was apparent in the performing arts and literature.

Due to increasing efforts of standardisation in the 19th and 20th century, the localised forms present in different districts and also among the remaining source-cultures with the less-assimilated ethno-cultural groups have seen greater alienation. However, Assamese culture in its hybrid form and nature is one of the richest and is still under development.

Assamese culture in its true sense today is a 'cultural system' comprised of different sub-systems. It is more interesting to note that even many of the source-cultures of Assamese culture are still surviving either as sub-systems or as sister entities. In broader sense, therefore, the Assamese cultural system incorporates its source-cultures such as Bodo (Boro) or Khasi or Mishing (Micing) but individual development of these sub-systems are today becoming important. However, it is also important to keep the broader system closer to its roots.

Some of the common cultural traits available across these systems are:

- Respect towards areca-nut and betel leaves

- Respect towards particular symbolic cloth types such as Gamosa, Arnai, etc

- Respect towards traditional silk and cotton garments

- Respect towards forefathers and elderly

- Great hospitality

- Bamboo culture

Some of the major elements of Assamese cultural system are:

Symbolism

Symbolism is an important part of Assamese culture. Various elements are being used to represent beliefs, feelings, pride, identity, etc. Symbolism is an ancient cultural practice in Assam, which is still very important for the people. Tamulpan, Xorai and Gamosa are three important symbolic elements in Assamese culture.

There were various other symbolic elements and designs traditionally in used, which are now only found in literature, art, sculpture, architecture, etc or used for only religious purposes (in particular occasions only). The typical designs of assamese-lion, dragon, flying-lion, etc were used for symbolising various purposes and occasions.

Festivals

There are several important traditional festivals in Assam. Bihu is the most important and common and celebrated all over Assam.

Bihu is a series of three prominent festivals of Assam. Primarily a festival celebrated to mark the seasons and the significant points of a cultivator's life over a yearly cycle, in recent times the form and nature of celebration has changed with the growth of urban centers. A non-religious festival, all communities---religious or ethnic---take part in it. Three Bihus are celebrated: rongali, celebrated with the coming of spring and the beginning of the sowing season; kongali, the barren bihu when the fields are lush but the barns are empty; and the bhogali, the thanksgiving when the crops have been harvested and the barns are full. Rongali, kongali & bhogali bihu are also known as 'bohag bihu', 'kati bihu' & 'magh bihu' respectively. The day before the each bihu is known as 'uruka'. There are unique features of each bihu. The first day of 'rongali bihu' is called 'Goru bihu' (the bihu of the cows). On this day the cows are taken to the nearby rivers or ponds to be bathed with special care. Traditionally, cows are respected as sacred animals by the people of Assam. Bihu songs and Bihu dance are associated to rongali bihu.

Moreover, there are other important traditional festivals being celebrated every year for different occasions at different places. Many of these are celebrated by different ethno-cultural groups (sub and sister cultures). Few of these are:

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki

table code?† |

Responsive/ Mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

† Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.

Music

Assam, being the home to many ethnic groups and different cultures, is very rich in folk music. The indigenous folk music has in turn influenced the growth of a modern idiom, that finds expression in the music of such artists like Bhupen Hazarika, Anima Choudhury Nirmalendu Choudhury & Utpalendu Choudhury, Luit Konwar Rudra Baruah, Parvati Prasad Baruva, Jayanta Hazarika, Khagen Mahanta among many others. Among the new generation, Zubeen Garg, Debojit Saha and Jitul Sonowal have a great fan following.

Traditional crafts

Assam has maintained a rich tradition of various traditional crafts for more than two thousand years. Presently, Cane and bamboo craft, bell metal and brass craft, silk and cotton weaving, toy and mask making, pottery and terracotta work, wood craft, jewellery making, musical instruments making, etc remained as major traditions.[29] Historically, Assam also excelled in making boats, traditional guns and gunpowder, ivory crafts, colours and paints, articles of lac, traditional building materials, utilities from iron, etc.

Cane and bamboo craft provide the most commonly used utilities in daily life, ranging from household utilities, weaving accessories, fishing accessories, furniture, musical instruments to building construction materials. Traditional utilities and symbolic articles made from bell metal and brass are found in every Assamese household.[30][31] The Xorai and bota have been in use for centuries to offer gifts to respected persons and are two prominent symbolic elements. Hajo and Sarthebari / Xorthebaary are the most important centres of traditional bell-metal and brass crafts. Assam is the home of several types of silks, the most prominent and prestigious being Muga, the natural golden silk is exclusive only to Assam. Apart from Muga, there are other two varieties called Pat, a creamy-bright-silver coloured silk and Eri, a variety used for manufacturing warm clothes for winter. Apart from Sualkuchi / Xualkuchi, the centre for the traditional silk industry, in almost every parts of the Brahmaputra Valley, rural households produce silk and silk garments with excellent embroidery designs. Moreover, various ethno-cultural groups in Assam make different types of cotton garments with unique embroidery designs and wonderful colour combinations.

Moreover, Assam possesses unique crafts of toy and mask making mostly concentrated in the Vaishnav Monasteries, pottery and terracotta work in lower Assam districts and wood craft, iron craft, jewellery, etc in many places across the region.

Paintings

Painting is an ancient tradition of Assam. The ancient practices can be known from the accounts of the Chinese traveller Xuanzang (7th century CE). The account mentions that Bhaskaravarma, the king of Kamarupa has gifted several items to Harshavardhana, the king of Magadha including paintings and painted objects, some of which were on Assamese silk. Many of the manuscripts available from the Middle Ages bear excellent examples of traditional paintings. The most famous of such medieval works are available in the Hastividyarnava (A Treatise on Elephants), the Chitra Bhagawata and in the Gita Govinda. The medieval painters used locally manufactured painting materials such as the colours of hangool and haital. The medieval Assamese literature also refers to chitrakars and patuas. Traditional Assamese paintings have been influenced by the motifs and designs in the medieval works such as the Chitra Bhagawata.

There are several renowned contemporary painters in Assam. The Guwahati Art College in Guwahati is a government institution for tertiary education. Moreover, there are several art-societies and non-government initiatives across the state and the Guwahati Artists Guild is a front-runner organisation based in Guwahati.

Economy

Macro-economic trend

Economy of Assam today represents a unique juxtaposition of backwardness amidst plenty.[32] Growth rate of Assam’s income has not kept pace with that of India’s during the Post-British Era; differences increased rapidly since 1970s.[33] While the Indian economy grew at 6 percent per annum over the period of 1981 to 2000, the same of Assam’s grew only by 3.3 percent.[34] In the Sixth Plan period Assam experienced a negative growth rate of 3.78 percent against a growth rate of 6 percent of India’s.[33] In the post-liberalised era (after 1991), the gaps between growth rates of Assam’s and India’s economy widened further.

In the current decade, according to recent analysis, Assam’s economy is showing signs of improvement. In the year 2001-2002, the economy grew in 1993-94 constant prices at 4.5 percent, falling to 3.4 percent in the next financial year.[35] During 2003-2004 and 2004-2005, in the same constant prices, the economy grew more satisfactorily at 5.5 and 5.3 percent respectively.[35] The advanced estimates placed the growth rate for the year 2005-2006 at above 6 percent.[36]

In the 1950s, soon after the independence, per capita income in Assam was little higher than that in India; it is much lower today. In the year 2000-2001, per capita income in Assam was INR 6,157 at constant prices (1993-94) and INR 10,198 at current prices, which is almost 40 percent lower than that in India.[37] According to the recent estimates,[38] per capita income in Assam at 1993-94 constant prices has reached INR 6520 in 2003-2004 and INR 6756 in 2004-2005, which is still much lower than the same of India.

This is a chart of trend of gross state domestic product of Assam at market prices estimated by Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation with figures in millions of Indian Rupees.

| Year | Gross State Domestic Product |

|---|---|

| 1980 | 25,160 |

| 1985 | 56,730 |

| 1990 | 106,210 |

| 1995 | 194,110 |

| 2000 | 314,760 |

Assam's gross state domestic product for 2004 is estimated at $13 billion in current prices.

Sectoral analysis again exhibits a dismal picture. The average annual growth rate of agriculture, which was only 2.6 percent per annum over 1980s has unfortunately fallen to 1.6 percent in the 1990s.[39] Manufacturing sector has shown some improvement in the 1990s with a growth rate of 3.4 percent per annum than 2.4 percent in the 1980s.[39] Since past five decades, the tertiary sector has registered the highest growth rates than the primary and secondary sectors, which even has slowed down in the 1990s than in 1980s.[39]

Agriculture

Agriculture accounts for more than a third of Assam’s income and employs 69 percent of total workforce.[40] Assam's biggest contribution to the world is its tea. Assam produces some of the finest and most expensive teas in the world. Other than the Chinese tea variety Camellia sinensis, Assam is the only region in the world that has its own variety of tea, called Camellia assamica. Assam tea is grown at elevations near sea level, giving it a malty sweetness and an earthy flavor, as opposed to the more floral aroma of highland (e.g. Darjeeling, Taiwanese) teas. Assam also accounts for fair share of India’s production of rice, rapeseed, mustard, jute, potato, sweet potato, banana, papaya, areca nut and turmeric. Assam is also a home of large varieties of citrus fruits, leaf vegetables, vegetables, useful grasses, herbs, spices, etc, which are mostly subsistance crops.

Assam’s agriculture yet to experience modernisation in real sense and is lagged behind. With implications to food security, per capita food grain production has declined in past five decades.[41] On the other hand, although productivity of crops increased marginally, still these are much lower in comparison to highly productive regions. For instance, yield of rice, which is staple food of Assam, was just 1531kg per hectare against India’s 1927kg per hectare in 2000-2001[41] (which itself is much lower than Egypt’s 9283, USA’s 7279, South Korea’s 6838, Japan’s 6635 and China’s 6131kg per hectare in 2001[42]). On the other hand, although having a strong domestic demand, 1.5 million hectares of inland water bodies and numerous rivers and streams and 165 varieties of fishes,[43] fishing is still in its traditional form and production is not self-sufficient.[44]

Industry

Apart from tea and petroleum refineries, Assam has few industries of significance. Industrial development is inhibited by its physical and political isolation from neighbouring countries such as Myanmar, China and Bangladesh and from the other growing South East Asian economies. The region is landlocked and situated in the eastern most periphery of India and is linked to the mainland of India by a flood and cyclone prone narrow corridor with weak transportation infrastructure. The international airport in Guwahati is yet to find airlines providing better direct international flights. The Brahmaputra suitable for navigation does not posses sufficient infrastructure for international trade and success of such a navigable trade route will be dependent on proper channel maintenance, and diplomatic and trade relationships with Bangladesh.

Assam is a major producer of crude oil and natural gas in India. Assam is the second place in the world (after Titusville in the United States) where petroleum was discovered. Asia’s first successful mechanically drilled oil well was drilled in Makum (Assam) way back in 1867. The second oldest oil well in the world still produces crude oil. Most of the oilfields of Assam are located in the Upper Assam region of the Brahmaputra Valley. Assam has four oil refineries located at Guwahati, Digboi, Numaligarh and Bongaigaon with a total capacity of 7 MMTPA (Million Metric Tonnes per annum). Bongaigaon Refinery and Petrochemicals is the only S&P CNX 500 conglomerate with corporate office in Assam.

Although having a poor overall industrial performance, several other industries have nevertheless been started, including a chemical fertiliser plan at Namrup, petrochemical industries at Namrup and Bongaigaon, paper mills at Jagiroad, Panchgram and Jogighopa, sugar mills at Barua Bamun Gaon, Chargola, Kampur, cement plant at Bokajan, cosmatics plant (HLL) at Doom Dooma, etc. Moreover, there are other industries such as jute mill, textile and yarn mills, silk mill, etc. Unfortunately many of these industries are facing loss and closer due to lack of infrastructure and improper management practices.

Places in Assam

Major cities and towns

History of urban development goes back to almost two thousand years in the region. Existence of ancient urban areas such as Pragjyotishapura (Guwahati), Hatapesvara (Tezpur), Durjaya, etc and medieval towns such as Charaideu, Garhgaon, Rongpur, Jorhat, Khaspur, Guwahati, etc are well recorded.[27]

Guwahati is the largest urban centre and a million plus city in Assam. The city has experienced multifold growth during past three decades to grow as the primate city in the region; the city's population was approximately 0.9 million (considering GMDA area) during the census of 2001. The other important urban areas are Dibrugarh, Jorhat, Tinsukia (Tinicukiya), Sibsagar (Xiwoxagor), Silchar (Silcor), Tezpur, Nagaon, Lakhimpur, Bongaigaon, etc. Population growth in the Barak Valley town of Silchar is also astonishing during past two decades. Nalbari, Mangaldoi, Barpeta, Kokrajhar, Goalpara, Dhubri (Dhubury), etc are other towns and district head quarters. On the other hand Duliajan, Digboi, Namrup, Moran, Bongaigaon, Numaligarh, Jogighopa, etc are major industrial towns. Currently, there are around 125 total urban centres in the state.

Attractive destinations

Assam has several attractive destinations; majority of these are National Parks, Wildlife and Bird Sanctuaries,[45] areas with archaeological interests and areas with unique cultural heritage. Moreover, as a whole, the region is covered by beautiful natural landscapes.

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki

table code?† |

Responsive/ Mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

† Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.

See also

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki

table code?† |

Responsive/ Mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

† Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.

Notes and references

- ^ Dixit 2002

- ^ World Heritage Centre 2007

- ^ Sarma, Satyendra Nath (1976) Assamese Literature, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden, p2. "While the Shan invaders called themselves Tai, they came to be referred to as Āsām, Āsam and sometimes as Acam by the indigenous people of the country. The modern Assamese word Āhom by which the Tai people are known is derived from Āsām or Āsam. The epithet applied to the Shan conquerors was subsequently transferred to the country over which they ruled and thus the name Kāmarūpa was replaced by Āsām, which ultimately took the Sanskritized form Asama, meaning "unequalled, peerless or uneven"

- ^ Times News Network, February 28, 2006

- ^ Editorial, The Assam Tribune, January 6, 2007.

- ^ Wandrey 2004 p3-8

- ^ a b c Singh (ed.) 1993. Cite error: The named reference "RLSinghIndia" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ a b NEDFi & NIC-Assam 2002

- ^ Wandrey 2004 p17

- ^ Purdue University 2004

- ^ Borthakur 2002

- ^ Birdlife International, UK Indo-Gangetic Grasslands

- ^ National Mission on Bamboo Applications 2004

- ^ Sharma 2003

- ^ ENVIS Assam 2003

- ^ Aitchison 1931, p230-233 (web-version from Project South Asia, South Dakota State University, USA)

- ^ a b Hazarika 2003

- ^ a b The Governor of Assam 1998

- ^ MacFarlane, Alan and Iris MacFarlane 2003

- ^ a b Revenue Department, Government of Assam

- ^ a b Directorate of Information and Public Relations, Government of Assam

- ^ a b The Government of Assam 2002-03

- ^ The National Commission on Population 2006

- ^ Director of Census Operations, Census of India 2001

- ^ Hussain 2004

- ^ Taher 1993

- ^ a b c d e f Barpujari 1990 Cite error: The named reference "HKBarpujariCHOA" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Kakati 1962

- ^ Assam Tourism 2002

- ^ Ranjan

- ^ Nath

- ^ National Commission for Women 2004

- ^ a b UNDP 2004 p22-23

- ^ UNDP 2004 p22

- ^ a b Government of Assam, Economic Survey of Assam 2004-2005

- ^ Government of Assam, Economic Survey of Assam 2005-2006

- ^ Government of Assam, Economic Survey of Assam 2001-2002 in Assam Human Development Report, 2003 p25

- ^ Government of Assam, Economic Survey of Assam 2005-2006

- ^ a b c UNDP 2004 p24-25

- ^ Government of Assam, Economic Survey of Assam 2001-2002 in Assam Human Development Report, 2003 p32

- ^ a b UNDP 2004 p33

- ^ FAO Statistics Division 2007

- ^ Assam Small Farmers’ Agri-business Consortium

- ^ UNDP 2004 p37

- ^ Directorate of Information and Public Relations 2002

- Aitchison, C. U. ed (1931), The Treaty of Yandaboo, A Collection of Treaties, Engagements and Sanads: Relating to India and Neighbouring Countries. Vol. XII., Calcutta: Government of India Central Publication Branch

{{citation}}:|first=has generic name (help); External link in|title= - Assam Small Farmers’ Agri-business Consortium, Template:PDFlink

{{citation}}:|access-date=requires|url=(help);|last=has generic name (help) - Assam Tourism 2002, Government of Assam, Arts and Crafts of Assam in About Assam, retrieved 2007-06-3

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Barpujari, H. K. (ed.) (1990), The Comprehensive History of Assam, 1st edition, Guwahati, India: Assam Publication Board

{{citation}}:|first=has generic name (help) - Birdlife International, UK, Template:PDFlink

- Borthakur, Ahir Bhairab (January 15, 2002), "Call of the wild", Down To Earth

{{citation}}: External link in|title= - Directorate of Information and Public Relations, Government of Assam, Area of the National Parks and Wildlife Sanctuaries in Assam, 2002, retrieved 2006-05-29

- Directorate of Information and Public Relations, Government of Assam, Assam at a Glance, retrieved 2007-05-25

- Dixit, K. M. (August 2002), "Chicken's Neck (Editorial)", Himal South Asian

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Editorial (6 January 2007), "Assam or Asom?", The Assam Tribune

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ENVIS Assam (April–June 2003), "Template:PDFlink", ENVIS Assam, Assam Science Technology and Environment Council, 2: 8

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: date format (link) - FAO Statistics Division, 2007, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, FAOSTAT, retrieved 2006-06-05

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Government of Assam. Chapter 2, Income, Employment and Poverty "Economic Survey of Assam 2001-2002 in Assam Human Development Report, 2003" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-06-06.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Government of Assam (2006). "Economic Survey of Assam 2004-2005 in NEDFi, Assam Profile, NER Databank" (html). Retrieved 2007-06-06.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Government of Assam. "Economic Survey of Assam 2005-2006 in NEDFi, Assam Profile, NER Databank" (html). Retrieved 2007-06-06.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Government of Assam 2002-03, Statistics of Assam, retrieved 2007-06-3

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|access-date=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Governor of Assam (8 November 1998). "Report on Illegal Migration into Assam". Retrieved 2007-05-26.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Hazarika, Sanjoy (2003), Strangers of the Mist, Penguin Books Australia Ltd.

- Hussain, Wasbir (September 20, 2004), "Assam: Demographic Jitters, Weekly Assessments & Briefings", South Asia Intelligence Review, 3–10

{{citation}}: External link in|title= - Kakati, Banikanta (1962), Assamese, Its Formation and Development, 2nd edition, Guwahati, India: Lawyer's Book Stall

- MacFarlane, Alan; MacFarlane, Iris (2003), Green Gold, The Empire of Tea, Ch.6-11, Random House, London

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Nath, T.K., Bamboo Cane and Assam, Guwahati, India: Industrial Development Bank of India, Small Industries Development Bank of India

- National Commission for Women (2004). "Situational Analysis of Women in Assam" (PDF). Retrieved 2006-07-05.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - National Commission on Population, Census of India (2006). "Population Projections for India and States 2001-2026" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-05-15.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - National Mission on Bamboo Applications, Assam, State Profile, retrieved 2007-05-25

- NEDFi & NIC-Assam, North East India Databank, retrieved 2007-05-20

- Purdue University, The Köppen Classification of Climates, retrieved 2007-05-25

- Ranjan, M.P.; Iyer, Nilam; Pandya, Ghanshyam, Bamboo and Cane Crafts of Northeast India, National Institute of Design

- Revenue Department, Government of Assam, Revenue Administration - Districts and Subdivisions, retrieved 2007-05-25

- Sharma, Pradip (April–June 2003), "Template:PDFlink", ENVIS Assam, Assam Science Technology and Environment Council, 2: 7

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: date format (link) - Singh, K. S (ed) (2003) People of India: Assam Vol XV Parts I and II, Anthropological Survey of India, Seagull Books, Calcutta

- Singh, R. L. (1993), India, A Regional Geography, Varanasi, India: National Geographical Society of India

- Taher, Mohammad (1993) The Peopling of Assam and contemporary social structure in Ahmad, Aijazuddin (ed) Social Structure and Regional Development, Rawat Publications, New Delhi

- Times News Network (28 February 2006), "Assam to fall off the map, turn Asom", The Times of India

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - UNDP (2004), Template:PDFlink, Government of Assam

- Wandrey, C. J. (2004), "Template:PDFlink", U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin, 2208-D

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - World Heritage Centre, UNESCO. "World Heritage List". Retrieved 2007-06-06.

Further reading

Language and literature

- Bara, Mahendra (1981), The Evolution of the Assamese Script, Jorhat, Assam: Asam Sahitya Sabha

- Barpujari, H. K. (1983), Amerikan Michanerisakal aru Unabimsa Satikar Asam, Jorhat, Assam: Asam Sahitya Sabha

- Barua, Birinchi Kumar (1965, c1964), History of Assamese Literature, Guwahati: East-West Centre Press

{{citation}}: Check date values in:|year=(help) - Barua, Hem (1965), Assamese Literature, New Delhi: National Book Trust

- Brown, William Barclay (1895), An Outline Grammar of the Deori Chutiya Language Spoken in Upper Assam with an Introduction, Illustrative Sentences, and Short Vocabulary, Shillong: The Assam Secretariat Printing Office

- Dhekial Phukan, Anandaram 1829-1859 (1977), Anandaram Dhekiyal Phukanar Racana Samgrah, Guwahati: Lawyer's Book Stall

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Endle, Sidney (1884), Outline of the Kachari (Baro) Language as Spoken in District Darrang, Assam, Shillong: Assam Secretariat Press

- Gogoi, Lila (1972), Sahitya-Samskriti-Buranji, Dibrugarh: New Book Stall

- Gogoi, Lila (1986), The Buranjis, Historical Literature of Assam, New Delhi: Omsons Publications

- Goswami, Praphulladatta (1954), Folk-Literature of Assam, Guwahati: Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies in Assam

- Gurdon, Philip Richard Thornhagh (1896), Some Assamese Proverbs, Shillong: The Assam Secretariat Printing Office

- Kakati, Banikanta (1959), Aspects of Early Assamese Literature, Guwahati: Gauhati University

- Kay, S. P. (1904), An English-Mikir Vocabulary, Shillong: The Assam Secretariat Printing Office

- Medhi, Kaliram (1988), Assamese Grammar and Origin of the Assamese Language, Guwahati: Assam Publication Board

- Miles, Bronson (1867), A Dictionary in Assamese and English, Sibsagar, Assam: American Baptist Mission Press

History

- Antrobus, H. (1957), A History of the Assam Company, Edinburgh: Private Printing by T. and A. Constable

- Barabaruwa, Hiteswara 1876-1939 (1981), Ahomar Din, Guwahati: Assam Publication Board

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Barooah, Nirode K. (1970), David Scott In North-East India, 1802-1831, New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers

- Barua, Harakanta 1813-1900 (1962), Asama Buranji, Guwahati: Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies, Assam

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Barpujari, H. K. (1963), Assam in the Days of the Company, 1826-1858, Guwahati: Lawyer's Book Stall

- Barpujari, H. K. (1977), Political History of Assam. Department for the Preparation of Political History of Assam, Guwahati: Government of Assam

- Barua, Kanak Lal, An Early History of Kamarupa, From the Earliest Time to the Sixteenth Century, Guwahati: Lawyers Book Stall

- Barua, Kanak Lal, Studies in the Early History of Assam, Jorhat, Assam: Asam Sahitya Sabha

- Baruah, Swarna Lata (1993), Last days of Ahom monarchy : a history of Assam from 1769-1826, New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers

- Bhuyan, Suryya Kumar (1949), Anglo-Assamese Relations, 1771-1826, Guwahati: Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies in Assam

- Bhuyan, Suryya Kumar (1947), Annals of the Delhi Badshahate, Guwahati: Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies, Government of Assam

- Bhuyan, Suryya Kumar (1957), Atan Buragohain and His Times, Guwahati: Lawyer's Book Stall

- Bhuyan, Suryya Kumar (1962), Deodhai Asam Buranji, Guwahati: Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies

- Bhuyan, Suryya Kumar (1928), Early British Relations with Assam, Shillong: Assam Secretariat Press

- Bhuyan, Suryya Kumar (1947), Lachit Barphukan and His Times, Guwahati: Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies, Government of Assam

- Bhuyan, Suryya Kumar (1964), Satasari Asama Buranji, Guwahati: Gauhati University

- Bhuyan, Suryya Kumar (1975), Swargadew Rajeswarasimha, Guwahati: Assam Publication Board

- Buchanan, Francis Hamilton 1762-1829 (1963), An Account of Assam, Guwahati: Department of Historical and Antiquarian Studies

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Duara Barbarua, Srinath (1933), Tungkhungia Buranji, Bombay: H. Milford, Oxford University Press

- Gait, Edward Albert 1863-1950 (1926), A History of Assam, Calcutta: Thacker, Spink & Co.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - Gogoi, Padmeswar (1968), The Tai and the Tai Kingdoms, Guwahati: Gauhati University

- Guha, Amalendu (1983), The Ahom Political System, Calcutta: Centre for Studies in Social Sciences

- Hunter, William Wilson 1840-1900 (1879), A Statistical Account of Assam, London: Trubner & Co.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

Tradition and Culture

- Barkath, Sukumar (1976), Hastibidyarnnara Sarasamgraha (English & Assamese), 18th Century, Guwahati: Assam Publication Board

- Barua, Birinchi Kumar (1969), A Cultural History of Assam, Guwahati: Lawyer's Book Stall

- Barua, Birinchi Kumar (1960), Sankardeva, Guwahati: Assam Academy for Cultural Relations

- Gandhiya, Jayakanta (1988), Huncari, Mukali Bihu, aru Bihunac, Dibrugarh

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Goswami, Praphulladatta (1960), Ballads and Tales of Assam, Guwahati: Gauhati University

- Goswami, Praphulladatta (1988), Bohag Bihu of Assam and Bihu Songs, Guwahati: Assam Publication Board

- Mahanta, Pona (1985), Western Influence on Modern Assamese Drama, Delhi: Mittal Publications

- Medhi, Kaliram (1978), Studies in the Vaisnava Literature and Culture of Assam, Jorhat, Assam: Asam Sahitya Sabha

External links

Column-generating template families

The templates listed here are not interchangeable. For example, using {{col-float}} with {{col-end}} instead of {{col-float-end}} would leave a <div>...</div> open, potentially harming any subsequent formatting.

| Type | Family | Handles wiki

table code?† |

Responsive/ Mobile suited |

Start template | Column divider | End template |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float | "col-float" | Yes | Yes | {{col-float}} | {{col-float-break}} | {{col-float-end}} |

| "columns-start" | Yes | Yes | {{columns-start}} | {{column}} | {{columns-end}} | |

| Columns | "div col" | Yes | Yes | {{div col}} | – | {{div col end}} |

| "columns-list" | No | Yes | {{columns-list}} (wraps div col) | – | – | |

| Flexbox | "flex columns" | No | Yes | {{flex columns}} | – | – |

| Table | "col" | Yes | No | {{col-begin}}, {{col-begin-fixed}} or {{col-begin-small}} |

{{col-break}} or {{col-2}} .. {{col-5}} |

{{col-end}} |

† Can template handle the basic wiki markup {| | || |- |} used to create tables? If not, special templates that produce these elements (such as {{(!}}, {{!}}, {{!!}}, {{!-}}, {{!)}})—or HTML tags (<table>...</table>, <tr>...</tr>, etc.)—need to be used instead.