Army of the emigrants

The army of the emigrants (fr. Armée des émigrés ) was an army that was raised by the counterrevolutionary French nobles and largely maintained with money from the Kingdom of Great Britain . However, these funds were not so abundant that the Comte d'Artois did not have to dismiss his Swiss Guard at some point.

Between 1789 and 1815, around 140,000 people emigrated from the country on the occasion of the French Revolution and because of the reprisals it feared. These emigrants , as supporters of the monarchy , feared collapse. Many of them were of the nobility, wealthy citizens or prelates . Some of them emigrated to fight the revolution from outside. For this they used the army of the emigrants.

This army was to march in the vanguard of the coalition armies at the beginning of the revolution to liberate the royal family and restore the monarchy. With the failure of the operation, after the retreat and in the years that followed, the aim of the princes was now to keep a French army in service and fighting against the revolutionaries and later against the troops of Napoleon Bonaparte . Their aim was to be able to sit at the table of peace negotiations on the day of the victory of their allies, also to avoid a new dynasty being founded in France, as in Poland, and perhaps foreigners sitting on the French throne . It was therefore necessary that an army of emigrants not only exist but also actively play their part in the struggle against the revolutionary armies, so that foreign monarchs would be strengthened against the claim to the Bourbon restoration in Paris.

After the campaign of 1792, the army of the princes disbanded, while the "Armée de Condé" under Louis VI. Henri Joseph de Bourbon, prince de Condé , continued to fight in the service of Austria, then England and Russia until 1801. The emigrants were unable to implement their plans. Those who fought the republic were either killed in the fighting and not replaced, or were returning to France and serving in part in the Napoleonic army . As a result, the regiments maintained by the Allied powers disbanded or partially joined foreign armies (which was particularly true for the officers).

recruitment

This army was formed by emigrants who first sought refuge in Turin and other parts of Italy, then in Germany and Austria, and later in England and Russia. But not all emigrants took up arms against the republic. Some of them simply tried to escape the guillotine and, if possible, continue their lives abroad, for example by staying in the United States. On the other hand, some of the counter-revolutionaries fought not in the army of the emigrants but in units of the allied monarchies.

However, some of the royalists decided not to leave France and to fight in the Armée catholique et royale de Vendée or to participate in royalist uprisings or even in the Chouannerie .

The associations of the French royalists who opposed the revolution were very numerous. But in reality they were often only weak units:

- the “Nobles volontaires” (voluntary nobles), who emigrated from France, partly members of the royal army

- the troops raised by these nobles through subsidies from the European monarchies or even themselves

- the units of the French armed forces who preferred to fight on the side of the royalists, such as B. the 4 e régiment de hussards or the Régiment Royal-Allemand cavalerie

- French sailors condemned to inactivity because of the British superiority on the seas

- the survivors of the siege of Toulon (1793)

It was also not insignificant that some of the emigration soldiers were often only prisoners of the republican armies or inmates of the prisons of Southampton . In return for payment (or without it) - or to avoid conviction - they undertook to return to France and fight for the royalists. However, around 400 of these soldiers, called “Soldats carmagnoles”, then deserted and defected to Hoche .

Emigrants, aristocrats or commoners were robbed of their civil rights and their lands by the revolution, and the lands were sold as national property. Decrees provided for their death penalty should they return to France, and their families were often persecuted. The princes and their followers were partisans in the true sense of the word, but they did not fight for the captured Louis XVI because they foresaw his fate and accepted it as unalterable. A minority relied on the Comte de Provence , who would be regent when his brother died, but the majority placed their hopes on the Dauphin , who as Louis XVII would be the rightful new king. In 1802 Napoleon Bonaparte was the first consul to issue a general amnesty , from which only some generals of the emigrant army were excluded.

The troops

Anonymous caricature from 1791. Mockery of the Prince de Condé with Don Quichotte together with the Viscount de Mirabeau (Mirabeau Tonneau) and Sancho Panza , who lead a counter-revolutionary army in defense of the mill of excessive indulgence , which is made up of a bust of Louis XVI. is crowned.

Armée de Condé (1791–1801)

The Condé, a family in the service of the king

the father of Louis V Joseph de Bourbon, prince de Condé

the son of Louis VI. Henri Joseph de Bourbon, prince de Condé 1790

the grandson, Louis Antoine Henri de Bourbon-Condé, duc d'Enghien , 1792

The "Armée de Condé", commanded by Louis V Joseph de Bourbon, prince de Condé , as cousin of the king, was one of the troops of the army of the emigrants who had been set up to fight the revolution.

Condé was able to escape his arrest after the storm on the Bastille by first fleeing to the Netherlands . From here he went to Turin , then to Worms , while the king's brothers set up their headquarters in Koblenz , the capital of the Electorate of Trier . They set up the "Armée de Condé" here, which Elector Clemens-Wenzeslaus was not very happy about because of the massive threat from the neighboring country. On April 19, 1791, 27 officers of the Régiment de Beauvoisis made themselves available to the prince.

This army took part in the wars of the French Revolution from 1792 to 1801 along with the armies of the HRR . So she fought in the battles of the failed invasion of France.

As in the army of princes, there were a number of aristocrats here too, including his own son, Louis VI. Henri de Bourbon-Condé, his grandson, Louis-Antoine de Bourbon-Condé, Armand Emmanuel du Plessis, duc de Richelieu , Pierre-Louis de Blacas d'Aulps , Claude Antoine Gabriel Choiseul, Louis Alexandre Andrault de Langeron , Joseph-François- Louis-Charles de Damas , François Dominique de Reynaud de Montlosier , Count de Mauny, Louis de Bonald and many from the lower nobility such as François-René de Chateaubriand . This force had almost more officers than soldiers. Elegant officers suddenly became soldiers of the monarchy, but it was a force in which no one wanted to clean a gun or hold an exercise.

"However, they were all brave and ready to be killed."

Philippe-Jacques de Bengy de Puyvallée, former member of the nobility of the Bailiwick of Bourges , escaped from revolutionary prison, noted in November 1791:

“There is no concept of a grand plan, either in the details or in the reports, everything is covered with a veil of total ignorance. But we organize legions, companies, and every day I hear that by January at the latest we will be at the head of 80,000 men in France. If I then say that I don't see any Caporal, I am told that the troops only march at night with small detachments. "

Chateaubriand noted about the army:

"A gathering of old men and children, it hummed and hummed in the dialect of Normandy, Brittany, Picardy, Auvergne, Gascony, Provence and Languedoc."

Condé's troops made many marches back and forth, but this was of little benefit to military training.

Some didn't care. Louis-Antoine de Bourbon-Conde d'Enghien, like his grandfather, dreamed of bringing the emigrants back to their homeland, where they would have more right to live than these people, who every day threw them back into barbarism.

The "Armée de Condé" fought on the side of the Austrians, but only 20,000 of the targeted 80,000 men were present. In an effort to closely control the movements of the emigrants, they kept the Austrians and Prussians in the rear of the military operations in 1792 and placed them under an Austrian general in 1793.

After this quasi-inactivity of 1792, the "Armée de Condé" was not affected by the general dissolution of the French emigrant troops. Stationed in Baden , in Villingen , the army stayed all winter in anticipation of further events. The training continued in the meantime. On January 25, 1793, a funeral service in memory of King Louis XVI was held in the city church. who had been murdered four days earlier.

Eventually the Prince's emissary, Count d'Ecquevilly, managed to persuade the Emperor to keep the troops in service until March. Condé became field marshal , his son, Louis VI. Henri de Bourbon, prince de Condé, major general . The higher grades of the majority of gentlemen were not confirmed. The soldiers were paid seven sous a day. Condé brought together the bulk of salaries (including his own) and distributed them to everyone regardless of rank. A very democratic measure for this army of aristocrats!

The troops were then subordinated to the Austrian field marshal Dagobert Sigmund von Wurmser , a native of Alsace. In April it was reorganized according to the Austrian model. It was agreed that the current division should not be larger than 6,000 men, at which point it was 6,400 men strong. It was here that Condé began (and not for the first time) to consider himself superfluous.

Organization of the Armée de Condé at the beginning of 1792

At the beginning of 1792, when the war had just started, the strength of the "Armée de Condé" was about 4,900 men.

- Infantry :

- the "Régiment noble à pied de Condé" (also called "Infantry noble") to about 1350 men

- the "Légion noire de Mirabeau" to about 1200 men

- the Hohenlohe regiment to about 600 men

- the "Régiment de Rohan" to about 400 men

- the "Compagnie de quartier général" (headquarters company) to about 100 men

- Cavalry :

- the "Régiment de cavalerie noble" (noble cavalry regiment) of about 560 men

- the Chevaliers de la couronne (Knights of the Crown) to about 300 men

- the "Escadron de Dauphin" to about 100 men

- the " Hussards de Salm-Kirburg " to about 200 men

- the "Cavaliers de la Prévôté" to about 50 men

Composition of the Armée de Condé in 1795

- Infantry:

- "Régiment des Chasseurs nobles"

- "Légion noire de Mirabeau", then "Légion de Damas"

- "Regiment de Hohenlohe"

- "Régiment de Roquefeuil", after 1793 "Régiment de Bardonnenche"

- "Régiment Alexandre de Damas"

- "Regiment de Montesson"

- Cavalry:

- "1 er régiment noble" (1st noble regiment)

- "2 e régiment noble" (2nd noble regiment)

- "Régiment du Dauphin cavalerie"

- "Hussards de la Legion de Damas"

- "Hussards de Baschi de Cayla"

- "Chasseurs de Noinville"

- "Dragons de Fargues"

- "Chasseurs d'Astorg"

- "Dragons de Clermont-Tonnerre"

- "Cuirassiers de Furange"

- "Chevaliers de la couronne"

In 1796 the troops fought in Swabia . When the Peace of Campo Formio was concluded the following year , hostilities with France officially ended. After the end of the First Coalition War , the "Armée de Condé" entered the service of the Russian Tsar Paul I and was stationed in Poland. In 1799 she fought under Alexander Wassiljewitsch Suworow in the Rhineland. After the end of the Second Coalition War , the army switched to English services and fought in Bavaria. In 1800 Condé was released from the leadership of his troops and went into exile with his son in England.

More troops

As the future minister under Louis XVIII, the Baron Jean-François-Henri de Flachslanden, wrote in a letter of February 1793 to the Duc François-Henri d'Harcourt:

“The individual emigrants are very brave, but bad infantrymen. It would be necessary for this corps to be supported and led by a force used to discipline and fatigue. In the rows there are children, old people and the gentlemen from the cabinets. They fall over after a march and then overload the hospitals. The captaines who carry the musket are aware of their worth and demand that their comrades, who are in front of them as their leaders, do not treat them as simple soldiers. "

The Marquis Louis Ambroise du Dresnay, Colonel in the Régiment du Dresnay, was of the same opinion:

“The legions, made up of masters reduced to the wages and service of the common soldier, were decimated by disease; if we exclude some individuals who are of good constitution, all those who escaped death have fallen into a state of exhaustion and frailty from which they will not recover in their entire lives. To form a corps of soldiers from these people would complete the annihilation of the remnants of the French nobility, half of whom have already perished. "

Then there was the problem of the Carmagnoles , prisoners of war or deserters of the revolutionary troops who were integrated into the army of the emigrants.

Condé confessed to Cardinal Anne-Louis-Henri de La Fare:

"To convert these men who filled Vienna's prisons and the pontoons of England into Christ's soldiers was not a happy idea."

Another problem for the emigrants' military units was money. The regent and his brother distributed favors, rewarded missions and awarded honors from the court to the emigrants who surrounded them; those involved in small industries lived relatively lightheartedly in the middle of the cities, while the struggling emigrants became increasingly impoverished. In addition to the ridiculous wages, the Austrians did not provide them with any artillery or hospitals.

"In addition to their deplorable living conditions, the emigrants can only be sure that they would be shot if captured, and the volunteers from Paris sometimes had the pleasure of cutting the throats of the nobles."

This cruelty by the members of the Jacobin clubs and the agents of the convention caused the line troops to sometimes release the captured royalists. When Louis Aloys de Hohenlohe-Waldenbourg-Bartenstein was captured, the Republican officers treated him with exquisite courtesy. In return for his release, they only asked for encouragement from their friends who served in his regiment. A little more selflessly, officers and surgeons under Jean Victor Marie Moreau saved the lives of dozens of prisoners. Very little welcome among the German rural population, the German peasants sometimes represented a greater danger to the soldiers of the “Condé Army” than the Republicans.

Army of the Princes (1791–1792)

In September 1791, Louis XVI was forced to accept the constitution and there were few supporters of a return to the Ancien Régime . However, the princes still believed in it. They thought that they could return to French soil at the head of an army because they believed they could cause a counterrevolutionary uprising across France. Charles-Alexandre de Calonne already saw the troops march into France with their officers who had been chased away from their former regiments or emigrated.

“These men, dressed in the latest fashions that could only be used as adjutants, were eagerly awaiting the moment of victory. They had nice new uniforms; they strutted around with severity and ease. [...] These brilliant cavaliers, in contrast to the old knighthood, prepared for success with a love of fame. They looked contemptuously at us on foot, with sacks on their backs, little provincial gentlemen or poor officers who had become soldiers [...] I hated this emigration; I could hardly wait to see my colleagues, emigrants like me, six hundred livres a year. "

In Germany, the Prince's Army was formed in Trier in 1792, commanded by Marshals Victor-François de Broglie and Charles Eugène Gabriel de La Croix de Castries under the aegis of the brothers of Louis XVI, the Comte de Provence (later King Louis XVIII) and of the Comte d'Artois (later King Charles X ). Some of the emigrants at the court of the elector in Koblenz were formally jealous of the number of nobles and especially of officers who drew under his banner the military reputation of de Condé and the support he enjoyed in the army. The impoverished Norman manor owners, who lived in the greatest misery, witnessed the rivalries between Trier and Koblenz, in Koblenz between the two brothers, with the two brothers between the favorites, and they said with the common sense of their country: One should, however, first have a bed before you pull on the ceiling! The French princes thought that they would serve in three army corps, namely the army of Louis V Joseph of Bourbon-Condé, which was destined to invade France through Alsace and attack Strasbourg; in that of the princes, called the Central Army, which would follow the troops of the King of Prussia to invade France through Lorraine, and which would advance directly to Paris, and in that of Louis VI. Henri de Bourbon Condé, son of Prince de Condé, who was to invade the Netherlands and attack Lille in Flanders . She returned to France with 10,000 men in the rear of the army of Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel . During the Prussian invasion of Champagne , the Prince's army was commanded by Charles Eugène Gabriel de La Croix de Castries and Victor-François de Broglie. This corps was discharged on November 24, 1792, two months after the French victory in the cannonade at Valmy . The so-called allies of the emigrants always viewed the French as enemies and cared above all about their national interests. This also applied to the population of the empire, who still remembered the devastation of the past, especially in the Palatinate .

Charles de La Croix de Castries, son of the Maréchal de France Charles Eugène Gabriel de La Croix de Castries, served in the "Armée de Coblence" (Koblenz Army). In 1794 he set up his own sizable corps of emigrants here, which bore his name but was paid for with English money. However, this corps was not involved in any combat operations and was disbanded after a year because the English stopped making payments.

The royal guard

Priority for the princes was the re-establishment of the royal guard Maison militaire du roi de France , most of which was dismissed 12 years ago in order to save the costs. The four units of the Guard , Mousquetaires de la garde , Chevau-léger de la garde du roi , Grenadiers à cheval and the Gendarmes de la garde , were quickly formed and included the Marquis d'Hallay, the Comte de Montboissier, the Viscount de Virieu and subordinate to the Marquis d'Autichamp. Then there was the "Compagnie de Saint-Louis" of the Garde de la porte , under the Marquis de Vergennes, the unit of the Chevaliers de la couronne under the Comte de Bussy, the guard formation of Monsieur under the Comte de Damas and the Comte d 'Avaray and finally the Guard des Comte d'Artois under the Bailli de Crussol and the Comte François d'Escars.

All uniforms were extremely elegantly cut, as if made for the ball, all in strong colors with embroidery, the buttons decorated with coats of arms. “Our uniform was gallant,” said a relative who had entered one of the units: “[...] the skirt with orange collar and cuffs, as well as the braids on the shako, the dolman decorated with silver cords. We were all young and handsome, we never stopped laughing, even when the world was going to end. ”Then there was the so-called“ Institution de Saint-Louis ”, but this small elite corps only had a relatively short-lived existence. The “Compagnie de Luxembourg” of the Gardes du Corps was set up in the Pfaffendorf camp .

A few privileged few - around a hundred men - followed the prince to Jelgava on October 5, 1794 to escape the army of François Séverin Marceau .

- The units:

- Hussards de Bercheny

- Hussards de Salm-Kirburg

- Regiment de Saxe hussards

- Hussards de Baschi de Cayla

- Hussards de la Legion de Damas

- Hussards de Choiseul

- Hussards de Rohan

- Hussards de Hompesch

- Regiment de Rohan

The war

On August 19, 1793, the "Armée de Condé" was able to seize the places Jockgrim , Wörth am Rhein and Pfotz . The counterattack of the republican forces during the night could be repulsed, they also lost the towns of Hagenbach and Büchelberg ; their losses amounted to 3,000 men and 18 cannons. The "Armée de Condé" was then placed under Austrian command.

On December 1, 1793, the last attacks by the Moselle army made it necessary to move troops along the Rhine. On this 11th Frimaire, General Pichegru attacked the center of the emigrant-occupied village of Berstheim near Haguenau in vain to test the enemy's strength. The next day the artillery opened the battle again. The attacking infantry met the "Légion noire de Mirabeau" and the "Régiment de Hohenlohe" in the village, with whom they got into violent skirmishes. To reinforce the royalists, de Condé then arrived at the scene of the action at the head of four columns of infantry and drove the revolutionary troops out of the village. At the same time, his cavalry defeated the Republican cavalry on his right flank, captured seven cannons, and captured about 200 men.

In the army in the Netherlands

- Units:

- Legion de Damas

- Hussards de la Legion de Béon

In the Austrian army

After the campaign of 1792, the Austrians incorporated three cavalry regiments of the former royal army: the Régiment Royal-Allemand cavalerie , the Régiment de Saxe hussards and the Régiment de hussards de Bercheny . These three units consisted almost entirely of Germans anyway and thus fit perfectly into their own army.

After some initial successes in the Netherlands, Charles-François Dumouriez was defeated on March 18, 1793 in the Battle of Neer winds. He left Belgium and made demands of the government. The convention investigated the matter and sent him negotiators. He handed them over to the Austrians and wanted to march to Paris. The next day he spoke to his troops, who refused to obey him and some of them left him. However, almost a thousand men decided to follow him to the Austrians: 458 infantrymen of the Régiment d'Auvergne , the Régiment de Poitou , the Régiment Royal des Vaisseaux , the Régiment de Vivarais , the Régiment Royal-Suédois , the “Chasseurs à pied des Cévennes ”, the“ Tirailleurs d'Egron ”and a battalion of volunteers; then another 414 riders from the "Régiment de hussards de Bercheny", the Régiment Bourbon-Dragons , the 21 e régiment de chasseurs à cheval, the 3rd escadron of the régiment cuirassiers du Roi and an escadron "Dragons volontaires".

- Some of the units

- Regiment Royal-Allemand cavalerie

- Regiment de hussards de Bercheny

- Regiment de hussards de Saxe

- Chasseurs de Bussy

- Legion de Bourbon

With the army in Spain

In March 1793, France declared war on Spain, which had been impatiently awaited by the many emigrants from the south and Roussillon on the other side of the Pyrenees. General Antonio Ricardos and his 15,000 men, among them the legions of the Comtes de Panetier and de Vallespir, penetrated the Roussillon from Perpignan , but proceeded only half-heartedly. After a few victories and defeats, the Spanish attack got stuck.

The Legion of the Comte de Panetier

The "Légion de Panetier" was a battalion of royalist troops, the 1793 de by Louis-Marie Panetier, comte de Miglos and Montgreimier, former seigneur of Villeneuve (*;? † 1794), a member of the nobility of the Estates General for Couserans , had been set up . As a strict opponent of the revolutionaries, he left the National Assembly in 1791 . He recruited members of the émigré nobility as well as available French deserters and some Spanish NCOs. The staff was 400 men. They fought alongside the Spanish troops of General Antonio Ricardos during the war between the Kingdom of Spain and revolutionary France in Catalonia . Most of the French soon left the Vallespir Legion (which became a border battalion) to join Panetier. This was able to distinguish himself with his troops in the conquest of Montbolo and Saint-Marsal (Eastern Pyrenees). The Legion moved into winter quarters in Port-Vendres . She defended Port-Vendres in May 1794 and was then evacuated by sea to prevent the members from being captured and guillotined. The commandant was Colonel Comte de Panetier, who was succeeded by General Santa Clara on his death in January 1794. In June 1794 she formed the "Légion de la Reine" with the companies of the regiments "Royal-Provence" and "Royal-Roussillon" that remained after the siege of Toulon . The unit was now named in honor of the Spanish queen and fought in the ranks of the Spanish army. After the defeat at Zamora on January 5, 1796, she was incorporated into the "Régiment de Bourbon".

The Légion du Vallespir

The "Légion du Vallespir " was a unit of light infantry that was quickly set up in 1793. At the beginning it consisted of Spanish and French officers and NCOs and Spanish crews. The Spanish general placed Spanish soldiers under the command of the French emigrants. The Legion was 250 men strong and operated in association with the Spanish Army. But during the chaotic year in which the revolution was held in check in the southern Eastern Pyrenees, practically all 450 deployable men from Saint-Laurent-de-Cerdans and hundreds of others from the parishes of Haut-Vallespir fought alongside Spanish troops in the "Légion du Vallespir". The battalion de Saint-Laurent was commanded by Abdon de Costa (sometimes called Larochejaquelein du Midi); the young Thomas and Jean de Noëll were captain and lieutenant. The Legion was under the command of the Marquis d'Ortaffa, the former lord of the neighboring village of Prats-de-Mollo , actively fought with the Spanish armies in the plain and helped in October 1793 with the attempts of General Luc Dagobert's army, Arles-sur -Tech recapture, prevent. The numerous desertions from the Légion de Panetier then weakened the unit so much that the remnants ultimately had to be incorporated into the "Régiment de Bourbon".

The Régiment de Royal-Roussillon

The regiment Royal-Roussillon , which had been part of the royal army since 1657, was renamed on January 1, 1791 to "54 e regiment d'infanterie". At the end of 1793, a new “Régiment Royal-Roussillon” was set up by Général Antonio Ricardos with the help of a major from the “Légion des Comtes de Saint-Simon” in Barcelona .

It consisted of a few emigrants, but mainly of Catalan artisans from the north, but also of deserters and prisoners (the "Carmagnoles") or even law breakers, because recruitment was generally difficult. The suspects in the eyes of the Catalans were housed in barracks in Barcelona . On June 29, 1794, a religious holiday in Spain, these 200 "soldiers" who had never fought the Republicans planted a tree of freedom, danced the farandole and guillotined a picture of the King of Spain. The Catalans, who noticed this, gathered in front of the barracks and shouted “Long live religion! Long live our catholic king! Death to the French! ”In this one. What followed was a massacre , 129 of the pseudo-soldiers were killed and 40 wounded. Anti-French rallies followed almost everywhere in southern Catalonia. The "Royal-Roussillon" was therefore dismissed and its most reliable relatives incorporated into the Légion du comte Panetier.

The Catholic and Royal Legion of the Pyrenees (Légion catholique et royale des Pyrénées)

Claude-Anne de Rouvroy de Saint-Simon, Marquis, Deputy of the Bailliage et sénéchaussée d'Angoulême , took part in the campaign of 1792 after his emigration in the army of the princes. On May 16, 1793, King Charles IV of Spain appointed him Mariscal de Campo in his army. He got involved by gathering emigrants in Pamplona who were ready to fight. He set up a unit of 600 infantrymen and an Escadron Hussars and took command of this unit. This so-called "Légion des Pyrénées" (or "Légion de Saint-Simon") was made up of members of the higher aristocracy, land nobility and officers, but also prisoners of war, deserters, Basque emigrants and Spanish non-commissioned officers. The unit did not participate in any major 1793 operations. Only in December of the same year did the Spanish government consider sending the Legion with the English and Spanish troops to the relief of the besieged Toulon .

The Legion then fought:

- on April 26, 1794 near Saint-Étienne-de-Baïgorry with high casualties (17 of those who were captured were executed on the guillotine )

- on July 10, 1794 in the mountains of Arquinzun with personnel losses of between 30 and 50%

- on July 24, 1794 at Bidassoa , where she covered the Spanish retreat and lost 50 prisoners

- in November during the siege of Pamplona

The emigrants and deserters of the republican army who were captured were executed. While defending the Arquinzun position, Saint-Simon was shot in the chest. His legion now operated in the formation of the Spanish Army and in 1795 brought up the rear. Then the Legion was merged with the "Régiment Royal-Roussillon".

In 1796, Saint-Simon was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Army in Navarre and on April 20, 1796 received the post of Colonel in the "Régiment de Bourbon", which he had been assigned to set up. The following May the King of Spain granted him the rank of Captain General of Old Castile .

The regiment de Bourbon

The regiment was formed in 1796 by the Marquis Claude-Anne de Rouvroy de Saint-Simon from the remains of the "Légion de la Reine" (ex Légion de Panetier), the border battalion and most of the "Légion royale des Pyrénées". The regiment operated in the association of the Spanish Army and in 1796 was named Regimiento de Infantería Borbón n ° 47 (the numbering was changed to n ° 37 in 1802). It existed in the Spanish Army until 1931 when it was incorporated into the Regimiento de Cazadores de Alta Montaña Galicia n ° 64 . In 1814, however, it was still largely made up of foreigners and the Walloon Guards. In 1808 the workforce was 1,600. Garrison was Ciudad Rodrigo (1797), then Majorca . It fought at the siege of Girona and the battle of Las Rozas (1808).

José de San Martín , the later South American revolutionary, fought the Bonapartists in the regiment.

In the English army

- Units involved in landing in Quiberon

- the Hussards de Guernesey (incorporated into the Hussards d'York in 1800)

- the Hussards d'York

- the "Régiment Hector" (also called "Marine Royale")

- the "Régiment Loyal-Emigrant"

- the "Compagnies d'invalides étrangers" (mainly formed from the wounded of the "Régiment Loyal-Émigrant")

- the "Régiment du Dresnay" (then Régiment de Léon)

- the "Régiment Royal-Louis" (then Régiment d'Hervilly)

- the "Régiment de Mortemart"

- the "Régiment d'Allonville"

- the "Hussards de Hompesch"

- the "Chasseurs de Hompesch"

- the "Ulhans britanniques"

- the "Régiment de hussards de Bercheny"

- the Hussards de Salm-Kirburg

- the "Hussards de Waren" (formed a 60 man strong unit, which was worn down to nine men on landing in Quiberon)

- the "Hussards de Choiseul"

- the "Régiment de Saxe hussards"

- the "Hussards de Baschi de Cayla"

- the "Hussards de la Légion de Damas"

- the "Hussards de Rohan"

- the "Hussards de la Légion de Béon"

- the "Compagnie d'artilleurs franco-maltais"

- the "Régiment des Chasseurs britanniques"

- The Corsicans and the Antilles troops

- the "French Chasseurs" (1793–1798)

- the "Dragons légérs corses" (1794–1795)

- the "Ingénieurs et artificiers étrangers" (Corsicans)

- the three battalions "Royaux anglo-corses" (1794–1796)

- the "Gendarmerie Royale Anglo-Corse"

- the "Smith's Corsica regiment" (1795–1797)

- the "Corps des émigrés de Saint-Domingue"

- the "Légion britannique de Saint-Domingue" (emigrants and Creoles)

- the "Uhlans britanniques de Saint-Domingue" (emigrants and Creoles)

- the "Chasseurs français" (colored people)

- the "Gendarmes Royaux Anglais" (officers and colored auxiliaries)

The Régiment d'Allonville (1794–1796) and the landing in the Vendée

General Armand Jean d'Allonville changed to the service of the English king. He recruited emigrants and landed with 300 aristocrats under his command in June 1793 in Bremen . The later "Régiment d'Allonville" landed in France to restore the rule of the Bourbons. The historian Armand François d'Allonville, his son, wrote:

“After eight months of active effort, Joseph de Puisaye had succeeded in ensuring that the expedition would consist entirely of French regiments, paid for with English money. Four cadre companies were to be set up, which should grow up to regiments after landing in France. Louis-Antoine de Rohan-Chabot, the Marquis d'Oilliamson, the Viscount de Chambray and the Comte d'Allonville, my father, were appointed commanders. Stationed in Jersey and Guernsey, these cadre associations should support the main forces. "

This is confirmed by the Histoire générale des émigrés pendant la révolution français by Henri Forneron, but here we are talking about four brigades. The "Régiment d'Allonville" consisted of Breton aristocrats, 186 officers of the royal army and candidates for the Navy, the company d'Oilliamson was formed from the officers and soldiers of the "Régiment d'Allonville", but should then be under the command des Comte d'Artois in Brittany and the Vendée and was filled with volunteers and militiamen from the Vendée and former prisoners. The latter were called "carmagnoles" by the counter-revolutionaries.

In early September 1796 Armand Jean d'Allonville left Guernesey and went to Camp Ryde on the Isle of Wight . His force consisted of 240 volunteers, all of them former officers or landed gentry. In Southampton , 60 ships were ready to pick up the entire expeditionary army and set them ashore in the Vendée.

Vast preparations have been made in the maritime cities and garrisons of Great Britain. In order to prepare the residents of the Vendée for what was to come, they were given daily public notices in which the progress of the expedition was documented and the generals and regiments who were to take part were named. It was Francis Rawdon-Hastings, Commander in Chief, who said, “The name of these soldiers is a guarantee of honor, courage and loyalty.” Major General Doyle headed the first landing party; the second, which consisted exclusively of emigrants, consisted of the regiments Mortemart, Castres, Allonville, Rohan and Choiseul as well as the Chasseurs d'York and the "Ulhans britanniques". The Comte d'Artois also took part in the expedition. The Republicans were prepared and assembled all available land and naval forces at the threatened spot. The fleet, which had to operate on a large scale, actually consisted of only 40 transport ships: only 2,000 soldiers, 500 Uhlans and a 400 to 500-strong cadre of French emigre officers could be transported. The first three companies of the "Régiment d'Allonville" were involved in the brief occupation of the Île d'Yeu at the end of 1795 , but did not arrive at all in the Vendée. Thousands of Vendéens stood ready on land to drive away the weak republican forces. But only a handful of the emigrants appeared on the scene. The Comte d'Artois was too late. Republican reinforcements came in quickly and the English did not want to attack the Île de Noirmoutier , which was defended by 2,000 men and a strong artillery. Francis Rawdon-Hastings was recalled from his command, much to the regret of the emigrants. He was friends with General d'Allonville and had always shown great interest in the affairs of the royalists.

Together with the Vendéens and the Chouans

Joseph de Puisaye, the commander in chief of the Chouans of Brittany, who had gone to England in 1795, was involved in the Quiberon expedition. More than 5,000 soldiers from the emigration army landed in Carnac , but over half of them were republican defectors who had been recruited more or less forcibly. Though fraternally united, discord was soon sown as the emigrant leader, Louis Charles d'Hervilly , had no confidence in the Chouans and refused to allow troops made up of Chouans to launch attacks on the Republicans. The expedition ended in a catastrophe, the regiments of emigrants were crushed in the battle near Plouharnel and in the Battle of Quiberon , more than 500 were killed in battle, 627 emigrants captured and 121 Chouans were shot. The Chouans were angry with the emigrants, who they accused of causing the expedition to fail. The general of the emigrants, Antoine-Henry d'Amphernet de Pontbellanger , was arrested by the Chouans and sentenced to death for leaving the army. He was finally pardoned and banished by the new General Georges Cadoudal . Cadoudal refused any officer among the emigrants in the Morbihan department , and in a letter to Jacques Anne Joseph Le Prestre de Vauban dated September 7, he described the emigrants as "monsters that would have been better devoured by the sea before arriving in Quiberon".

Puisaye, however, continued to rely on the emigre units. After differences of opinion with Cadoudal, he left the Morbihan and occupied the Ille-et-Vilaine . On November 5, Puisaye wrote to the Council of Princes in London:

“The Morbihan that Georges is occupying is turning more than ever against the nobility and against the emigrants. They say they are waging a people's war and not a restoration. In this corps of the army the gentlemen are not of good standing, so Georges was able to concentrate all his energies and gain all confidence. We have to be prepared for the fact that he can escape from one day to the next. To prevent the republic he will always be its most relentless enemy, but in his own way he will fight the revolution which he hates. Resistance to our plans will always come from those royalists who want to create equality under the white flag. The nobility has lost a lot of prestige, in the Morbihan they love a gentleman who fights as a volunteer; but we don't want the first person who runs along and makes the law. What is creeping up in this area is already secretly noticeable in all other parts of Brittany. "

Joseph de Puisaye united the divisions of Fougères and Vitré in the east of the Ille-et-Vilaine on behalf of Aimé Picquet du Boisguy. Still determined to rely on the nobility, he created the company "Chevaliers catholiques", which consisted of sixty emigrants, all officers. These received several commands in the Chouan divisions, which the existing leaders displeased. In March 1796, one of the Chouan officers nicknamed "La Poule" tried to provoke an uprising against the emigrants. However, he was quickly arrested, sentenced, and then shot on Puisaye's orders.

In August 1795, the Comte d'Artois tried to unite the army of the Vendéens with an army of emigrants and British. The "Ile d'Yeu Expedition" was a failure, but several emigrants ended up in the Vendée to join the army of General François Athanase Charette. However, they received an unfriendly reception from the Vendéens because the announcement that a group of emigre officers had been formed to command the peasants angered their commanders. The "proud and contemptuous" behavior of most of the emigrants drew the hostility of the Vendée fighters. The Vendée officer Pierre-Suzanne Lucas de La Championnière wrote that “we hated each other as if we were not from the same party”.

“Emigrants who escaped Quiberon or ended up on other coasts came to Belleville to join us. We couldn't feel sympathy for one another; by a clumsiness it had previously been announced in a proclamation that officers would come to command our regiments. This news, which we found unflattering, struck us as ridiculous. Our leaders, who had commanded for two years, were unwilling to leave their places and least of all to hand over to preferred foreigners. Let them do what we did, we said, that they work just as long, that they can cope with the struggle and the fatigue, then the bravest of them or of us will have the position, or that they form their own corps and march separately. They also made a bad impression on us in the battle near Quiberon, especially after a battle between the Vieillevigne division and a division of Republicans who escorted a convoy back to Montaigu (Vendée) . They were beaten and our soldiers returned with fine English weapons that had been taken from the emigrants.

When the gentlemen arrived, disregarding those who had prepared the way in two years, most of them appeared proud and scornful. Instead of approaching the Vendée officers and showing them some admiration, gratitude and courtesy, they formed their own group and stayed apart. In many ways they corresponded to what led Republicans to preach the hatred and contempt of the nobility. "

“A foreigner who came to us to receive some awards had great courage at the first opportunity in front of the most fearless of the army. Without this torment, of whatever quality, we would never have earned the soldier's awe or respect. The real soldiers soon became known, unfortunately almost all of them were killed in the first few fighting. A Herr de la Jaille, who survived this despite the hardship, pleased the farmers because, although old, he walked and was fully committed. Another officer, named La Porte, felt respect only for those who had volunteered. In the middle of the night he got up to saddle his horse and knock on the door of a barn where soldiers were sleeping. When asked who he was, he said, 'Open - I am the Chevalier de La Porte, Chevalier de Saint-Louis.' - 'Well,' said someone, 'if you are the Chevalier de La Porte, then guard the porte.' Angry at such an answer, he rattled the door until it opened, but the first one that fell into his hand slammed hard. It then took him some time to look for a light at headquarters, and when he came back vengeful the barn was empty.

The divisions that went first into the fire also had the advantage of receiving the best treatment, because in the village in which they stopped they had the best quarters and everything that was of use for convenience; Even on the marches they made sure that no one came forward who did not have a right or habit to be there. Understandable that when someone approached bedtime they wanted to try to get in the first rows to lie on brocade. This condition was a hundred times worse for the emigrants.

But what was surprising was that Charette didn't seem to like her, and he didn't refuse anyone to resign, which many did.

Pierre Constant de Suzannet had lived in a castle since his arrival, which was said to have good food, while we often lacked bread. Charette put together a company of volunteers with permission to take away anything that was successfully carried out. It was not his preference for his former officers that he did so, for he treated them harshly and showed little confidence in them; we haven't known him as a friend since Louis Guérin's death. "

Several emigrants also joined the army of Jean-Nicolas Stofflet , who was not involved in combat operations. In December 1794 an officer wrote Charles a letter to his commander in chief; in which he worried about the growing influence of emigrants at the expense of former officers.

A small army of 748 captured emigrants was sentenced by Hoche on the Quiberon peninsula in 1795. They were all shot.

In Prussia

In August 1791, the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm II met with Emperor Leopold II in Pillnitz . Here they decided to prop up Louis XVI and restore monarchy in France. Friedrich Wilhelm himself took part in the campaigns of 1792 and 1793. However, he was hampered by a lack of money, and his advisers were more interested in Poland , which offered better prospects for booty than a crusade against revolutionary France.

Between 1789 and 1806 more than 5,500 emigrants were registered in the Prussian states. The class solidarity of the king towards the emigrants was to have a lasting influence on Prussian domestic politics. Prussian kings showed more solidarity with emigrants than with their own high officials. Nevertheless, the state came first for them and prevented them from accepting too many emigrants in Prussia. The importance of state authority was clearly demonstrated by the immigration of emigrants into the Prussian army, which was a fundamental instrument for integrating the Prussian monarchy. The king only allowed the emigrants to be integrated into this elite group because they were useful to him because of their high military fitness or because they were sometimes young enough to embrace Prussian patriotism. In addition to the Minister of War Julius von Verdy du Vernois , a number of Prussian generals who were in service or who returned to service in 1914 had French names: Martin Chales de Beaulieu , Gerhard von Pelet-Narbonne , Eduard Neven Du Mont , Lavergne-Peguilhem , Carl von Beaulieu-Marconnay , Longchamps-Bérier, Emil von Le Bret-Nucourt, Amand von Ruville and two generals Digeon de Monteton. In addition, a dozen senior officers who achieved the rank of general during the war had French roots: Anton Wilhelm von L'Estocq , Anton Wilhelm Karl von L'Estocq , Perrinet de Thauvernay, Lorne de Saint-Ange, eight generals La Chevallerie , Coudres and again Digeon de Monteton and Beaulieu-Marconnay. However, some of these Germans are descendants of Huguenots.

In Russia

At the Russian court, the French emigrants met with real sympathy. When Catherine, the Empress of Russia, heard that Louis V Joseph de Bourbon-Condé had not received the 100,000 crowns that had been promised to him by the German Emperor, she immediately sent them to the prince and said: “As long as you do I will help you use your money well. ”In February 1793 the Empress ordered her ambassadors to financially release the nobles and other emigrants of any kind after the disbandment of the prince's army from all powers.

In January 1793 she had Armand-Emmanuel du Plessis von Richelieu convey to Louis V Joseph de Bourbon-Condé that she strongly supported the cause of the emigrants and gave them “in the event that this French Republic should consolidate, a settlement on Sea of Azov on the 46th parallel ”. The colony would have consisted of six thousand nobles, at whose disposal a sum of six thousand ducats would have been made available so that they could live. Each of them would have had two horses and two cows. They kept their culture, obeyed their own laws and recognized them as head Louis V. Joseph de Bourbon, prince de Condé. The land that would be given to them was formerly part of the kingdom of Pontus by Mithridates VI. been.

French emigrants poured into Russia. They were usually soldiers and very hostile to revolutionary France. Thomas Jean Marie du Couëdic, nephew of Charles Louis du Couëdic, emigrated in 1791 and served as a captain in the Russian Navy.

When he joined the anti-French coalition, Tsar Paul I hastened to show the French emigrants the greatest interest. He gave some of them ranks in his army. Counterrevolutionary committees were formed to assist discontented people who remained in France in hopes of delaying the strengthening of the republic's institutions.

The French government then asked the Tsar to revoke the exceptional protection he had granted the emigrants. It also happened that emigrants in Russian services wanted to use their uniforms in order to remain undisturbed as foreigners in France. This could always have led to diplomatic entanglements between the two governments. Paul I then agreed that carefully chosen terms should be used against France that France could not object to. The use of the word emigrants and any other expression that would have been too direct in some way to describe them was avoided.

Furthermore, the French government demanded that every emigrant who had settled in Russia and who allowed himself to maintain correspondence with the "internal enemies" be expelled from the countries under Russian rule. It was also announced that the government of the republic was taking the right to expel emigrants who came to France in the service of Russia in Russian uniform or with a government mandate - as had happened - without being able to claim diplomatic protection.

Fate of the families of the members of the emigrant army

A large number of the parents of the emigrants were gutted, guillotined, executed, otherwise killed or died because of the conditions of detention in the revolutionary prisons. Many of their relatives escaped during this time by hiding in small villages in the Périgord or other provinces, where no one wanted to know much about revolutionary uprisings.

After the reign of terror and the law of September 17, 1793, women were no longer immediately pursued by emigrants, but they were severely harassed:

- by the prohibition of changing residence

- through daily control

- by paying taxes that were arbitrarily set

- through humiliation by the revolutionary authorities or the so-called patriots

- by robbing property and profits from z. B. trade or agriculture etc.

Since the property of the emigrant families was sold as national property, the wives of the emigrants were dependent on an extremely poor pension that was disproportionate to their previous income. The women were sometimes forced to get divorced. Correspondence with the husbands was a criminal offense.

Some prominent members of the army

- Jean-Baptiste Symon de Solémy

- François-Henri de Franquetot de Coigny

- Louis-Marie-François de La Forest Divonne - Major général in the Armée de Condé, Maréchal de camp

- Charles-Julien Lioult de Chênedollé - Poet

- Louis de France (1775-1844)

- Pierre Marie Alexis du Plessis d'Argentré - military and politician

- Antoine Xavier Natal - Marechal de camp

- Louis-Auguste-Victor de Ghaisnes de Bourmont

- René Charles Guilbert de Pixérécourt

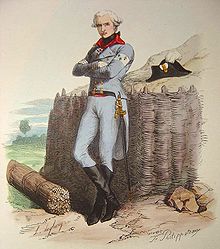

- Antoine Le Picard de Phélippeaux - Colonel of the Artillery

- Anne-Alexandre-Marie de Montmorency-Laval - Lieutenant-général des armées du roi

- Louis-François Carlet de La Rozière - military and secret agent

- Charles-César de Damas d'Antigny - general and politician

- Roger de Damas d'Antigny

- Bernard de Corbehem - war volunteer

- Louis Pierre de Chastenet de Puységur - Minister of War in the years 1787–1789

- Antoine Charles Augustin d'Allonville - Maréchal de camp ( fallen during the Tuileries storm on August 10, 1792)

- Armand Jean d'Allonville - General of the Cavalry

- Armand François d'Allonville - Maréchal de camp and scientist

- Alexandre Louis d'Allonville - Maréchal de camp and politician

- Cerice de Vogüé - Maréchal de camp and Deputy of the Estates General

- Joseph-Louis-Claude de Cadoine de Gabriac-Colonel

- Victor François de Montchenu - Maréchal de camp

- Louis François Marie Bellin de La Liborlière - writer

- Esprit Charles Clair de La Bourdonnaye - Maréchal de camp

- Hippolyte-Marie-Guillaume de Rosnyvinen de Piré

- Claude-Louis de Lesquen-Bishop of Rennes

- Louis Dubois-Descours, marquis de la Maisonfort -general and writer

- Damien Orphée Le Grand de Boislandry - Lieutenant du roi

- Adrien de Rougé - politician, Pair de France

- Philippe François Maurice d'Albignac

- Cyrille Jean Joseph Lavolvène, known as Chevalier de la Volvène - Adjudant-général (died January 23, 1800 near Meslay-du-Maine )

- Joseph-Paul-Marie Raison du Cleuziou

- Joseph de Banyuls, comte de Montferré - Maréchal de camp

- Auguste François Bucher de Chauvigné - Colonel

- Franz Xaver of Saxony

- André Boniface Louis Riquetti de Mirabeau

- Pierre-Étienne Dumesnil Dupineau - formerly officer of the Garde du corps du roi of Louis XVI

- Henri-René Bernard de la Frégeolière - Maréchal de camp

- Bernard-Armand-Jean de Bernard du Port - Major and Militia Leader

- Louis-Anselme-François Pasqueraye du Rouzay - writer

- François-Nicolas de la Noüe - Colonel and militia leader

- Louis Marie de Sainte-Marie - politician

- Jean de Sapinaud de Boishuguet - writer

- Claude-Antoine-Gabriel de Choiseul - Colonel, Pair de France

- François-Frédéric de Béon - Colonel

Footnotes

- ^ Greg Dening: Beach Crossings. Voyaging Across Times, Cultures, And Self. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia 2004, ISBN 978-0-8122-3849-5 , p. 125.

- ^ Duc de Castrie: Les Émigrés (= Les temps et les destins ). Librairie Arthème Paillard, Paris 1962, p. 187.

- ^ Henry-René D'Allemagne: Histoire des jouets. Hachette, Paris 1902, p. 192 ( full text in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Chevalier d'Hespel, quoted in Grouvel , 1961.

- ↑ Philippe-Jacques de Bengy de Puyvallée, quoted in Bertaud, 2001, p. 123 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ^ François-René de Chateaubriand, quoted in Bertaud, 2001, p. 133 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ↑ Louis-Antoine de Bourbon-Condé, quoted in Bertaud, 2001, p. 123 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ↑ Quoted from Forneron, 1884, Volume II, p. 13 ( digitized on Gallica ).

- ↑ Forneron, 1884, Volume II, p. 13 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Forneron, 1884, Volume II, p. 13 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Forneron, 1884, Volume II, page 14 ( digitized ).

- ↑ Forneron, 1884, Volume II, page 14 ( digitized ).

- ↑ Forneron, 1884, Volume II, page 17 ( digitized ).

- ^ François-René de Chateaubriand: Mémoires d'outre-tombe. Volume 2. Meline, Cans, Brussels 1849, p. 28 (new edition Librairie Générale Française (LGF), Paris 2000, ISBN 978-2-253-16050-2 ).

- ^ Armand-Francois Hennequin d'Ecquevilly: Campagnes du corps sous les ordres de Son Altesse Sérénissime M gr le prince de Condé. Volume 1. Le Normant, 1818, p. 23 (new edition 2018, Forgotten Books, ISBN 978-0-656-29832-7 , full text in the Google book search).

- ↑ Forneron, 1884, Volume I, p 264 ( digitized ).

- ↑ Pierre Olivier d'Argens: Mémoires d'Olivier d'Argens et correspondances des généraux Charette, Stofflet, Puisaye, d'Autichamp, Frotte, Cormartin, Botherel (= Mémoires relatifs à la Révolution française ). F. Buisson, Paris 1824, p. 20 (new edition Kessinger Publishing, Whitefish 2010, ISBN 978-1-168-62302-7 ).

- ↑ Forneron, 1884, Volume I, p 264 ( digitized ).

- ↑ Forneron, 1884, Volume I, p 262 ( digitized ).

- ^ Notice on M. Leroy-Jolimont par le secrétaire (I). In: Mémoires de la Société royal d'agriculture, histoire naturelle et arts utiles de Lyon. 1828-1831. JM Barret, Lyon 1832, p. 68 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ↑ Jean Pinasseau: L'émigration militaire. Emigrés de Saintonge, Angoumois, et Aunis dans les corps de troupe de l'emigration française. 1791-1814. A. and J. Picard, Paris 1974 ( OCLC 464101209 ).

- ^ Philippe-Joseph-Benjamin Buchez , Prosper-Charles Roux-Lavergne: Histoire parlementaire de la révolution française, ou Journal des Assemblées nationales depuis 1789 jusqu'en 1815, contenant La narration des événements […]; précédée d'une Introduction sur l'histoire de France jusqu'à la convocation des États-Généraux. Volume 31. Paulin, Paris 1837, p. 6 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ Panetier de Montgenier. In: Website of the French National Assembly (PDF; 1.56 MB).

- ↑ Louis de Marcillac: Histoire de la guerre entre la France et l'Espagne, pendant les années de la Révolution française 1793, 1794 et partie de 1795. Magimel, Paris 1808, p. 190 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ Antoine Henri de Jomini: Histoire critique et militaire des guerres de la Révolution. Nouvelle édition, rédigée sur de nouveaux documents, et augmentée d'un grand nombre de cartes et de plans. Volume 2. J.-B. Petit, Brussels 1837, p. 66 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ↑ Arthur Chuquet: Dugommier (1738–1794). Albert Fontemoing, Paris 1904, p. 380 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Archives départementales des Pyrénées-Orientales (ADPO). 1 M, p. 402; Pierre Vidal: L'an 93 en Roussillon (1 re série). Compte-rendu fait à la Convention nationale par le représentant du peuple Cassanyes. Loriot, Céret, 1897, pp. 62-63; Joseph Napoléon Fervel: Campagnes de la Révolution française dans les Pyrénées orientales. Volume 2. Pilet fils aîné, Paris 1853, p. 161 ( digitized , new edition Éditions Lacour, 2008, ISBN 978-2-7504-1970-7 ); Jean Sagnes: Le Pays catalan (Capcir - Cerdagne - Conflent - Roussillon - Vallespir) et le Fenouillèdes. 2 volumes. Société Nouvelle d'Éditions Régionales et de Diffusion, Pau 1983 and 1985, ISBN 2-904-61001-4 / ISBN 2-904610-01-4 , p. 620.

- ^ François Mignet, Henry Vergé, P. de Boutarel: Séances et travaux de l'Académie des sciences morales et politiques. Compte rendu. Volume 64 (164th of the collection). Académie des sciences morales et politique, Alphonse Picard et fils, Paris 1905, p. 446 ( digitized version ).

- ^ Rafael Tasi: La revolució francesa i Catalunya (= Episodis de la història ). Editorial Rafael Dalmau, Barcelona 1962. Quoted in: III. Una frontera injustificable. In: Llorenç Planes: Catalunya nord, la importància d'un nom. El petit llibre de Catalunya Nord, Barcelona 1962.

- ↑ Biography des hommes vivants, ou Histoire par ordre alphabétique de la vie publique de tous les hommes qui se sont fait remarquer par leurs actions ou leurs écrits. Volume 5 (P-Z). LG Michaud, Paris 1819, p. 288 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ Louis Miard: Les sources espagnoles relatives à l'histoire de la Révolution dans l'ouest de la France. 1789-1799. Guide des sources d'archives et publications de textes. Édition du Conseil général de Loire-Atlantique, 1989, p. 348 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ William-Aimable-Émile-Adrien Fleury: Soldats ambassadeurs sous le Directoire, an IV – an VIII. Volume 1. Plon-Nourrit, Paris 1906, p. 150 ( full text in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Georges Poisson : Claude-Anne, "duque" (?) De Saint-Simon. In: Cahiers Saint-Simon. Société Saint-Simon, No. 31, 2003, p. 107 (provided by the Persée portal ).

- ^ Revue d'histoire de Bayonne, du Pays basque et du Bas-Adour. Société des Sciences Lettres et Arts de Bayonne, No. 157, 2002, p. 201 (ISSN 1240-2419).

- ↑ Michel Péronnet, Jean-Paul Jourdan: La Révolution dans le département des Basses-Pyrénées. 1789-1799. Horvath, 1989, ISBN 978-2-7171-0618-3 , p. 128.

- ↑ Études religieuses, philosophiques, historiques et littéraires (monthly journal). Ed .: Pères de la Compagnie de Jésus. Victor Retaux et fils, Paris 1856, 26th vol., Volume 48, 1889, p. 82; Arthur Chuquet: Dugommier (1738-1794). Albert Fontemoing, Paris 1904, p. 380 ( digitized version ).

- ↑ René Chartrand; Patrice Courcelle (Ill.): Emigré and Foreign Troops in British Service (= Men-at-Arms ). Osprey Publishing, 1999, ISBN 978-1-85532-766-5 , p. 40.

- ↑ Nicolas Viton de Saint-Allais : Nobiliaire universel de France, ou Recueil général des généalogies historiques des maisons nobles de ce royaume. Volume 8. Self-published , Paris 1816, p. 284 ( full text in the Google book search, reprint Bachelin-Deflorenne 1874 on Gallica).

- ^ A b Armand François Allonville: Mémoires secrets de 1770 à 1830. Volume 3. Ollivier, Paris 1851, p. 380 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ↑ Henri Forneron: Histoire générale des émigrés pendant la révolution français. Volume II. E. Plan-Nourrit, Paris 1884, p. 104 ( full text in the Google web archive).

- ^ Joseph Toussaint: La Déportation du clergé de Coutances et d'Avranches à la Révolution. Éditions de l'Avranchin, Avranches 1979, pp. 130, 135.

- ^ Charles Hettier, Samuel Elliott Hoskins: Relations de la Normandie et de la Bretagne avec les îles de la Manche. Pendant l'emigration, d'après des documents recueillis par le dr Samuel Elliott Hoskins, membre de la Société Royal de Londres et la Société des antiquaires de Normandie. Imprimerie F. Le Blanc-Hardel, Caen 1885, p. 172, OCLC 458115811 (reprinted Forgotten Books, 2018, ISBN 978-0-265-32262-8 ).

- ↑ Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Jullien de Courcelles : Dictionnaire historique et biographique des généraux français, depuis le onzième siècle jusqu'en 1820. Volume 2. 1821, p. 512 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ↑ Alphonse de Beauchamp: Histoire de la guerre de la Vendée et des Chouans, depuis son origine jusqu'à la pacification de 1800. Volume 3. Giguet et Michaud, Paris 1807, p. 260 ( full text in the Google book search); Nicolas Viton de Saint-Allais: Nobiliaire universel de France, ou Recueil général des généalogies historiques des maisons nobles de ce royaume. Volume 8. Self-published , Paris 1816, p. 284 ( full text in the Google book search, reprint Bachelin-Deflorenne 1874 on Gallica).

- ^ Jacques Crétineau-Joly: Histoire de la Vendée militaire. Volume 2. Hivert, 1840, pp. 344, 345 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ↑ Alphonse de Beauchamp: Histoire de la guerre de la Vendée et des Chouans, depuis son origine jusqu'à la pacification de 1800. Giguet et Michaud, Paris 1807, p. 260 ( full text in the Google book search); Jacques Crétineau-Joly: Histoire de la Vendée militaire. Volume 2. Hivert, 1840, pp. 346, 347 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ↑ Michelle Sapori: Rose Bertin. Ministre des modes de Marie-Antoinette. Institut français de la mode / Éditions du Regard, Paris 2003, ISBN 978-2-914863-04-9 , p. 236. On the Régiment d'Allonville see also René Chartrand; Patrice Courcelle (Ill.): Emigré and Foreign Troops in British Service. Volume 1. Osprey Publishing, 1999, ISBN 978-1-85532-766-5 , p. 9 ( limited preview in Google Book Search).

- ↑ Patrick Huchet: Georges Cadoudal et les Chouans. Éditions Ouest-France, Rennes 1997, ISBN 978-2-7373-2283-9 , p. 231 ( limited preview in the Google book search).

- ↑ Pierre-Suzanne Lucas de La Championnière: La Guerre de Vendée au pays de Charette. Mémoires d'un officier vendéen. 1793-1796. Éditions du Bocage, 1994, ISBN 978-2-908048-18-6 , p. 135.

- ^ Jean-Julien Savary: Guerres des Vendéens et des Chouans contre la République. Volume VI. Baudouin frères, Paris 1827, pp. 72–74 ( full text in the Google book search).

- ^ Thomas Höpel: L'attitude des rois de Prusse à l'égard des émigrés français durant la revolution. In: Annales Historiques de la Révolution française. Ed .: Société des études robespierristes . No. 323, 2001, pp. 21-34 (provided by the Persée portal).

- ^ Georges Dillemann: La carrière des officiers prussiens. In: Carnet de La Sabretache. Ed .: Société d'études d'histoire militaire. No. 48, 1978.

- ↑ Louis Blanc : Histoire de la révolution française. Volume 12. Langlois et Leclercq, Paris 1862, p. 244.

- ↑ Recueil des instructions données aux ambassadeurs et ministres de France depuis les traités de Westphalie jusqu'à la Révolution française. Russie, France. Volume 9. Ed .: Commission des archives diplomatiques. Félix Alcan, Paris 1890, p. 592.

literature

- Antoine de Saint-Gervais: Histoire des émigrés français, depuis 1789, jusqu'en 1828. Volume 3. LF Hivert, Paris 1828 ( full text in the Google book search).

- Armand François Hennequin Ecquevilly: Campagnes du corps sous les ordres de Son Altesse Sérénissime Mgr le prince de Condé. Volume 3. Le Normant, Paris 1818 ( full text in the Google book search).

- Étienne Romain, comte de Sèze: Souvenirs d'un officier royaliste, contenant son entrée au service, ses voyages en Corse et en Italie, son émigration, ses campagnes à l'armée de Condé, et celle de 1815 dans la Vendée. 3rd volume. L.-F. Hivert, Paris 1829 ( limited preview in Google Book search).

- Robert Grouvel: Les corps de troupe de l'emigration française, 1789–1815. Volume 1: Service de la Grande Bretagne et des Pays-Bas. La Sabretache, Paris 1958. Volume 2: L'armée de Condé. La Sabretache, Paris 1961, OCLC 10439711 .

- René Bittard des Portes: Histoire de l'armée de Condé pendant la Révolution française (1791–1801). E. Dentu, Paris 1896 ( full text in the Internet Archive ; new edition Perrin. Foreword by Hervé de Rocquiny. Paris 2016, ISBN 978-2-262-04723-8 ).

- Jean Pinasseau: L'émigration militaire. Campagne de 1792. A. et J. Picard, Paris 1971.

- A.-Jacques Parès: Le Royal-Louis. Regiment français à la solde de l'Angleterre levé au nom du roi Louis XVII à Toulon, en 1793. P. Beau & C., Mouton 1927, OCLC 82482248

- Henri Forneron: Histoire générale des émigrés. E. Plon, Nourrit, Paris. Volume I, 1884 ( digitized on Gallica ), Volume II, 1884 ( digitized ), Volume III, 1890 ( digitized ).

- René Chartrand; Patrice Courcelle (Ill.): Emigré and Foreign Troops in British Service (= Men-at-Arms ). Volume 1: 1793-1802. Osprey Publishing, Oxford 1999, ISBN 978-1-4728-0720-5 . Volume 2: 1803-15. Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2000, ISBN 978-1-85532-859-4 .

- Jean-Paul Bertaud: Le duc d'Enghien. Librairie Arthème Fayard, 2001, ISBN 978-2-213-64778-4 ( limited preview in Google book search).

- André Jouineau, Jean-Marie Mongin: Les hussards français. Volume 1: De l'Ancien régime à l'Empire. Éditions Histoire & Collection, Paris 2004, ISBN 978-2-915239-02-7 .

Web links

- Thomas Höpel: L'attitude des rois de Prusse a l'égard des émigrés français durant la Révolution. In: Annales historiques de la Révolution française. No. 323, January-March 2001, pp. 21-34

- Thierry Rouillard: Les régiments émigrés en Espagne ( Memento of November 15, 2008 in the Internet Archive ). Édition La Vouivre, Paris. In: Histoire et Figurine

- Débarquement des émigrés à Quiberon. Website of the Musée du patrimoine de Quiberon

- Les ennemis de la Révolution, troupes émigrées ( Memento of October 10, 2008 in the Internet Archive ). Darnault family genealogy website

- Archives des tribunaux et de la police. Émigrés (Révolution française) ( Memento of July 22, 2014 in the Internet Archive ). In: FranceGenWeb

- Archives de la Maison du Roi (1815-1830). Armée des Princes et secours aux émigrés (1792–1832)