Kurtrier

Kurtrier (also: Erzstift Trier und Kurfürstentum Trier ) was one of the originally seven electoral principalities of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation . The secular territory of the Archbishop of Trier existed from the late Carolingian period until the Reichsdeputationshauptschluss of 1803. Since the turn of the 16th century it belonged to the Kurhine Empire and at the time of its greatest expansion essentially comprised the areas to the left and right of the lower reaches of the Mosel and Lahn . Its capital was Trier , the royal seat of Koblenz since the 17th century .

The archbishops of Trier, along with those of Mainz and Cologne, were among the three spiritual electors. Together with their four secular comrades, the Count Palatine of the Rhine , the Margrave of Brandenburg , the Dukes of Saxony and the Kings of Bohemia , they had the right to elect the German king since the turn of the 12th and 13th centuries, in 1356 was confirmed in the Golden Bull.

history

Emergence

The diocese of Trier was established in the late Roman period, in the 3rd century. Since the 6th century , the suffragans of Metz , Toul and Verdun were subordinate to him as an archbishopric . In the late Carolingian period, the Archbishops of Trier began to establish a secular territorial rule. This worldly property of the Bishop of Trier, the archbishopric , is to be distinguished from his spiritual sphere of influence, the diocese . Its limits were considerably wider. The archbishopric also included areas in Luxembourg and France, for example. On the other hand, the archbishopric included areas such as the Daun office in the Eifel , which were spiritually subordinate to the Bishop of Cologne.

Territorial development

Since 902 the Archbishops of Trier were also the secular lords of their residence city. Up until the beginning of the 11th century, the emerging electoral state was limited to areas around Trier, later known as the upper ore pen. This was expanded considerably in 1018 when Emperor Heinrich II transferred the Franconian royal court of Koblenz together with the associated imperial property to Archbishop Poppo von Babenberg of Trier . The land at the confluence of the Rhine and Moselle rivers and in the lower Westerwald formed the lower ore monastery from then on. In the 12th century, the bishops also won the secular possessions of the Imperial Abbey of St. Maximin and the bailiwick rights of the Rhineland Count Palatine in their diocese .

In the 12th and 13th centuries, a series of disputes with the Rhineland Count Palatine resulted in territorial gains for Trier. Points of contention included the Arras Castle , the Castle Treis and Thurant Castle . The result was the displacement of the Count Palatine from the Eifel-Moselle area to the south.

The Archbishops of Trier have been part of the Electors College since 1198. Like the other two ecclesiastical electors, they were chancellors of one of the three parts of the empire. The office of Arch Chancellor for Burgundy became a meaningless title with the extensive loss of the French-speaking areas of the Holy Roman Empire in the early modern period.

Between 1307 and 1354, under Archbishop Balduin of Luxembourg , the most important elector of Trier, a closed territorial connection was established between the upper and lower archbishopric, partly through warlike territorial acquisitions. In 1309, the future Emperor Heinrich VII pledged the cities of Boppard and Oberwesel on the Rhine to his brother Archbishop Balduin.

In the period that followed, Kurtrier gained additional areas in the Eifel , Hunsrück , Westerwald and Taunus , such as the offices of Manderscheid , Cochem , Hammerstein and Limburg . Above all, Kuno von Falkenstein and Werner von Falkenstein pursued a successful territorial policy.

The Manderscheider feud from 1430–1437 caused considerable destruction and financial burdens in the Trier Kurstaat. Ulrich von Manderscheid fought against Raban von Helmstatt for the Trier bishop's seat. With Ulrich's death in 1436 the dispute was essentially decided.

With the acquisition of the county of Virneburg in 1545 and the prince abbey of Prüm in 1576, the territorial development of the archbishopric was essentially complete. Unlike Kurköln and Kurmainz , the Trier Kurstaat had a largely closed territory. It stretched from the lower reaches of the Saar near Merzig on both sides of the Moselle to Koblenz and up the Lahn to Montabaur and Limburg . An exclave in the Duchy of Jülich was the office of Güsten - Welldorf , a former property of the prince abbey of Prüm.

During the time when the witch hunts were carried out in Kurtrier, Dietrich Flade led numerous witch trials and pronounced death sentences in his capacity as witch judge . In 1588 he got himself into a witch trial. He was arrested on July 4, 1588 on the orders of Elector Johann von Schönenberg and sentenced to death by fire on September 18, 1589.

Under the government of Elector Philipp Christoph von Sötern , Trier became involved in the Thirty Years' War after the Peace of Prague in 1635 . The diocese town, occupied by French troops since 1632, was conquered by the Spanish in 1635 and the territory of the electorate was devastated and depopulated by French, Swedish and imperial soldiers in the following years.

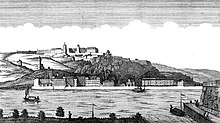

In 1669, the Electorate of Trier issued a land law that applies to the entire territory. The electoral state owned several centers of rulership, with the conveniently located Koblenz growing in importance. In 1632 the residence was moved from the now unsafe Trier to Philippsburg Palace in Ehrenbreitstein and in 1786 to the newly built Electoral Palace of Koblenz .

War of the Palatinate Succession

In June and July 1684 the city of Trier was occupied by French troops after the conquest of Luxembourg . After the outbreak of the Palatinate War of Succession , Kurtrier was almost completely occupied by France and heavily destroyed. The cities of Cochem , Mayen , Wittlich and other cities went up in flames. After Koblenz could not be captured in 1688, the city was badly damaged by cannon fire. Stolzenfels Castle on the Rhine was completely destroyed in 1689. Due to the unfortunate course of the war for the empire, the archbishopric remained in the hands of the French. In 1697 the War of the Palatinate Succession was ended by the Peace of Rijswijk and the French troops left the electorate.

The end of the electoral state

Under the last Elector of Trier, Clemens Wenzeslaus of Saxony , Koblenz became a rallying point for counter-revolutionary French nobles. During the First Coalition War , French revolutionary troops occupied most of the electorate in 1794 . The Ehrenbreitstein fortress in the Electorate of Trier was able to last until 1799, but then had to give up. Its areas on the left bank of the Rhine were annexed to France in the Peace of Lunéville in 1801 and essentially divided between the Sarre departments , based in Trier, and Rhin-et-Moselle , based in Koblenz. The areas on the right bank of the Rhine fell to Nassau-Weilburg in 1803 .

At the Congress of Vienna , most of the Electorate of Trier were added to the Kingdom of Prussia and, in 1822, incorporated into the Prussian Rhine Province . With the exception of the region around Limburg , they have belonged to Rhineland-Palatinate since 1946 . The coat of arms of the then newly formed country shows the red cross of Kurtrier next to the electoral Palatinate lion and the Mainz wheel .

The use of the title prince (arch) bishop and the use of the secular signs of dignity associated with it (such as the prince's hat and coat ) was approved in 1951 by Pope Pius XII. also formally abolished.

State castles

Kurtrier owned state castles for the administration and control of the territory . In contrast to the feudal castle, the archbishop could directly dispose of state castles. The facilities were manned by archbishop servants ( officials , castle men , waiters and guards).

List of Trier regional castles:

Arras , Baldenau , Balduinseck , Balduinstein , Bischofstein Castle , Castle Wernerseck , Boppard , Cochem , Ehrenbreitstein , Genovevaburg , Grimburg , Hard Rock , Old Castle Koblenz , Kyllburg , Oberburg Manderscheid , Malberg , Montabaur , New Castle , Pfalzel , Ramstein , noise castle , Saarburg , Sterrenberg , Stolzenfels , Treis , Thurant , Trier (palace hall) , Welschbillig .

The standing order

The status of the electorate of Trier provided for three organs: the elector, the cathedral chapter and the assembly of the estates .

The elector

The elector was the supreme ruler of the electorate and archbishop of the much larger archbishopric of Trier. After the election by the cathedral chapter, he was appointed archbishop by the pope and elector by the emperor . In his secular function, he was advised by a councilor and had ruled largely absolutist since the 16th century . However, he was often restricted in his decisions by the so-called right of consensus of the cathedral chapter and the estates.

The cathedral chapter

An important task of the cathedral chapter was the election of the archbishop. At its head stood the provost of the cathedral . The elector could not convene the estates without the approval of the cathedral chapter, furthermore the contracts of the elector without countersignature by the cathedral chapter were not valid. In times of the Sedis vacancy, the cathedral chapter took over the entire government, was able to mint coins and wage wars. The cathedral chapter assumed an autonomous position, was exempt from taxes and administered its property itself.

The estates

Since 1501 there were estates in Kurtrier , which were responsible for the entire electorate. Their main task was to approve new taxes. The creation of this body had become necessary after the reform of the Reich , which for the first time provided for the levying of a nationwide tax, the common penny . The elector called the state parliament, which usually met once a year, with the approval of the cathedral chapter. The state parliaments also discussed complaints and demands of the estates, which were then passed on to the elector.

The Trier electors since the 13th century

See also

literature

- Ingrid Bodsch : castle and rule. On the territorial and castle policy of the Archbishops of Trier in the High Middle Ages up to the death of Dieter von Nassau († 1307). Boppard 1989.

- Peter Brommer : Kurtrier at the end of the Old Kingdom. Edition and commentary on the Electoral Trier official descriptions from (1772) 1783 to approx. 1790. 2 volumes, Mainz 2008, ISBN 978-3-929135-59-6 .

- Richard Laufner: The Trier Archbishopric. In: Franz-Josef Heyen (Ed.): History of the State of Rhineland-Palatinate, Freiburg im Breisgau, Würzburg 1981, pp. 42–49.

- Franz Roman Janssen: Kurtrier in his offices, mainly in the 16th century. Studies on the development of early modern statehood. Bonn 1985, ISBN 3-7928-0478-6 .

-

Jakob Marx : History of the Archbishopric Trier.

- part One

- Volume 1, Trier 1858 ( full text ).

- Part II

- Volume 1: The abbeys of the Benedictine and Cistercian monastery ( full text)

- Volume 2: The monasteries and monasteries .

- part One

- Fritz Rörig: The emergence of the state sovereignty of the Archbishop of Trier between the Saar, Mosel and Ruwer and their struggle with the patrimonial powers. F. Lintz, Trier 1906.

- Friedrich Rudolph: The development of sovereignty in Kurtrier up to the middle of the 14th century. In: Trierisches Archiv. Supplementary booklet 5, pp. 1–65, F. Lintz, Trier 1905.

- Dorothe Trouet, aristocratic castles in Kurtrier. Buildings and building policy of the von Kesselstatt family in the 17th and 18th centuries. Kliomedia , Trier 2007 (History and Culture of the Trier Land, Vol. 6), ISBN 978-3-89890-105-5 .

- Hermann Weber : France, Kurtrier, the Rhine and the Reich. 1623-1635 . (Paris Historical Studies; 9). Röhrscheid, Bonn 1969 ( digitized version )

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Franz Gall : Austrian heraldry. Handbook of coat of arms science. 2nd edition Böhlau Verlag, Vienna 1992, p. 219, ISBN 3-205-05352-4 .