Fratricide (Ottoman Empire)

The fratricide ( Turkish kardeş katli ; also sehzade katli , Prince murder 'or evlat katli , Deszendentenmord') was in the Ottoman Empire usual, often preventive measure for resolving inheritance disputes within the ruling family . In addition to avoiding wars of succession , the aim was to ensure the indivisibility of the inheritance, and thus prevent the division of states. In the Ottoman context, the term fratricide therefore includes, contrary to the name, not only the killing of the (half) brother, but also that of any blood relative who is entitled to inherit. If a prince was executed, his sons usually shared the same fate.

The founder of the dynasty, Osman I, is said to have killed his aged uncle himself in the dispute over the undisputed tribal leadership. The first documented fratricide occurred during the reign of Murad I , who had two rebellious brothers executed in 1360 and a rebellious son in 1385. When Bayezid I came to power in 1389, the preventive killing of a non-rebellious prince took place for the first time.

In the last years of Mehmed II's reign , probably between 1477 and 1481, the killing of the brothers "for the sake of the order of the world" (niẓām-ı ʿālem içün) was expressly appropriate and thus the sacrifice of certain individuals for the benefit of the common good was permitted explained. The practice reached its peak under Mehmed III. who had 19 brothers executed when he ascended the throne in 1595 and his eldest son in 1603. With Mustafa I's accession to the throne in 1617, the succession from father to son was broken for the first time and based on the principle of seniority . An introduction of the Primogenitur , which both Abdülmecid I. and Abdülaziz wanted , ultimately failed to materialize, so that the seniorate was legally established in the new constitution of 1876 .

Succession to the throne

In the Ottoman Empire, there was no explicit and comprehensive regulation of the succession to the throne until the second half of the 19th century . The lack of fixed inheritance rules ( under house law ) was due to the notion of a rule given by God ( ḳuṭ or ḳut 'happiness granted by heaven, charisma'), on the basis of which the creation of a law of succession by human hands was regarded as a revolt against the divine will. Only male members of the Ottoman ruling house of patrilineal descent were entitled to inheritance , with each of these descendants having an equal claim to inheritance. For this reason, the discrediting or ostracizing unexpectedly appearing pretenders to the throne turned out to be “false” or “false” (düzme / düzmece) , that is, as not belonging to the dynasty, as an effective means in the struggle for the throne. The (assertion) ability or suitability ( liyāḳat , idoneity ) should be decisive for the succession to the throne , so that one can speak of a "survival of the most suitable". From this point of view, the outcome of warlike succession disputes was understood as a divine judgment and, with regard to the victor, ipso facto as an expression of his military talent and thus also his authority. Ultimately, however, decisive in the succession to the throne was the support of the high dignitaries, Ulama ’ and / or Janissaries , who supported those who seemed most suitable to them or who seemed most advantageous for opportunistic reasons.

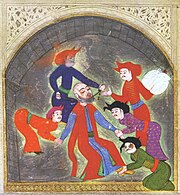

Ottoman miniature painting in the Şemāʾil-nāme-i āl-i ʿOs̠mān des Talikizâde , around 1593. Istanbul , Library of the Topkapi Seraglio Museum (TSMK), III. Ahmed, inv. No. 3592, fol. 10 b -11 a

From around the end of the 14th century, an Ottoman prince ( şeh-zāde ) was given an Anatolian sanjak for administration at the age of about fifteen , so that he became the prince-governor (çelebi sulṭān) under the guidance and supervision of an educator ( lālā ) Gain experience in administrative matters and learn the art of governance. If the great lord died, a prince had to rush to the capital of the empire or, if necessary, to the army camp and claim the throne for himself there. The sovereign could try to influence the succession by sending his favored son as governor of a sanjak not too far from the capital. Against this background, the sanjak centers of Amasya and, from the 16th century, Manisa were of particular importance .

In order to avoid unrest, the death of the Sultan was kept as secret as possible until the successor's accession to the throne (cülūs) and the burial ceremony was held only after the enthronement. If necessary, after the removal of internal organs and the embalming of the body, a temporary burial took place in a coffin usually made of walnut wood. The secrecy was mainly due to fear of an uprising by the grand gate troops , who could take advantage of the vacuum of authority resulting from a change of ruler - all members of the Imperial Council were resigned - and plunder the city with impunity while the throne was vacant.

With Murad III. (from 1562 to 1574) and Mehmed III. (from 1583 to 1595) only the eldest sultan's sons were appointed as presumptive successors actually and not only nominally as governors (in Manisa), while the others remained locked inside the Topkapı Palace for governorship as young princes . This also ensured that the designated ruler could ascend the throne undisputedly and have his (half) brothers in the palace executed without difficulty. After Mehmed III's accession to the throne. In 1595, no more princes were sent away, but kept in what was originally şimşīrlik or çimşīrlik (about ' box tree garden ') and later called ḳafe's 'cage' of the Sultan's palace. The sons of the ruling sultan were granted comparatively greater freedoms, but all imprisoned princes were prohibited from fathering children. The concubines, allowed in limited numbers, received various sterile drugs. However, if pregnancy did occur, male newborns in particular were disposed of immediately after delivery.

When thirteen-year-old Ahmed I ascended the Ottoman throne in December 1603 , his mentally ill brother Mustafa, who was one to two years his junior, was left alive in view of the young sultan's childlessness in view of dynastic continuity. This succeeded Ahmed I, who died on November 22, 1617 at the age of 27, on the throne, so that with the assumption of rule Mustafa I for the first time the principle of succession from father to son (ʿamūd-ı nesebī) was broken.

About two centuries later, both Abdülmecid I and Abdülaziz sought to introduce the primogeniture , but it was not successful. Finally, in 1876, the seniorate was legally established. Article 3 of the Constitution (as amended on December 23, 1876) reads:

سلطنت سنیهٔ عثمانیه خلافت کبرای اسلامیه یی حائز اوله رق سلالهٔ آل عثماندن اصول قدیمه سی وجهدله اکبر اولادلد اکبر عولادجهد

Salṭanat-ı senīye-i ʿOs̠mānīye ḫilāfet-i kübrā-yı islāmīyeyi ḥāʾiz olaraḳ sülāle-i āl-i ʿOs̠māndan uṣūl-ı ḳadīmesi vechile ekʿ evʾiddir iddir.

"The rulership in the Ottoman Empire, which also includes the high Islamic caliphate , is passed on to the oldest prince of the Osman dynasty according to a principle that has been in force since ancient times."

Fratricide law

“The Turkish empire has such a divine right and holy law on it, that every Turkish emperor, if he compts to the empire, must have his brothers strangled; then their law says that they recognize one God in heaven and one Lord on earth. "

Transcripts

The so-called fratricide law - untitled in the original - can be found in a collection of laws ( ḳānūn -nāme) attributed to Mehmed II , which deals with court ceremonies and state organization. This Ḳānūn-nāme , the only one of its kind , did not come to us in the original ; there are only copies from the 17th century. Two manuscripts offering the same text are in the Austrian National Library in Vienna (Cod. HO 143 and Cod. AF 547). The more recent manuscript, dated 15 Rebīʿü l-evvel 1060/18 March 1650, was freely translated into German by Joseph von Hammer around 1815 as Das Kanunname Sultan Mohammed II . About a century later, Mehmed Ârif Bey gave the text of the older manuscript dated 1 Ẕī l-ḥicce 1029/28 October 1620, without knowing the existence of the later copy, under the title Ḳānūnnāme-i āl-i ʿOs̠mān 'Code of the Ottoman ruling house 'in two supplements to the journal of the Society for Ottoman Historical Research. Further copies were unknown until the second volume of Koca Hüseyin's chronicle Bedāʾiʿü l-veḳāʾiʿ 'The original events of time', which was believed to be incomplete for a long time . The chronicler, according to his own statements, took the copy of the collection of laws contained therein from the original kept in the grand archives in 1022/1613 during his activity as chief secretary in the Reichsrat. The found copy of the Chronicle (518 sheets, in the Nestaʿlīḳ duct, sheet dimensions 18 × 28.5 cm, 25 lines per page) was acquired from a private collection by the Asian Museum in Saint Petersburg in 1862 and came from there to the Leningrader Department of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR , where it is kept in the institute's manuscript fund (NC 564). The long-neglected manuscript was published for the first time in 1961 as a facsimile edition.

According to their preface, the collection of laws was written by a certain Leyszâde Mehmed b. Mustafa, the head of the State Chancellery (tevḳīʿī) , has been compiled in three sections or chapters. The date is not certain, but the time of origin is largely set between the years 1477 and 1481 under the Grand Vizieri Karamânî Mehmed Paschas .

Position and wording of the fratricide law

The fratricide law is contained in the second chapter (bāb-ı s̱ānī) of the collection of laws. The copies preserved in the second volume of the Chronicle of Koca Hüseyin and in the Austrian National Library show only insignificant, only orthographical and stylistic deviations from one another with regard to the fratricide. The following is the version edited by Mehmed Ârif Bey in 1912:

و هر کمسنه یه (a) اولادمدن سلطنت میسر اوله (b) قرنداشلرین نظام عالم ایچون قتل ایتمك مناسبدر (c) اکثر علما دخی (d) تجویز ایتمشدر انکله (e) عامل اوله لر (f)

Ve her kimesneye evlādımdan salṭanat müyesser ola ḳarındaşların niẓām-ı ʿālem içün ḳatl ėtmek münāsibdir eks̠er-i ʿulemā daḫi tecvīz ėtmişdir anuñalar ʿ

“And each of my descendants, when they gain the sultanate, is allowed to kill their brothers in view of the order of the world. Most of the " Ulem" have given their approval. That's how they should act. "

Methods of execution and burial

Miniature excerpt from the second volume of the Hüner-nāme , around 1588. Istanbul, Library of the Topkapi Serail Museum (TSMK), Hazine, inv. No. 1524, fol. 181 a

18th century engraving by Cl. Duflos [sculp.] After N. Hallé [inv.], Edited by Jean-Antoine Guer, 1747

After Turco-Mongolian tradition no dynastic blood could be shed so that the execution of members of the dynasty usually by choking with a silk bowstring ( Kiriş or çile ) or a greased and provided with a sling belt (kemend) was completed. As an exception to this, Murad II had his “false” uncle Mustafa, who was actually a son of Bayezid I , hanged demonstratively in public in 1422 . 1808 was Selim III. stabbed .

Prince's children born in the “prince's prison”, especially sons, were killed immediately after giving birth by not tying off the severed umbilical cord . In the 19th century, the birth of Prince Yûsuf Izzeddin Efendi (* 1857) as well as that of Prince Selâhaddin Efendi (* 1866) was kept secret.

Executed princes were often buried together with their father, but some princes also found their final resting place in their own mausoleum ( Türbe ) . While all the sultans were buried there after the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, executed princes continued to be buried in Bursa until the end of 1574. Bayezid b. Suleyman I and four of his sons who were strangled in 1562 and buried in Sivas outside the city walls.

Accession to the throne and succession disputes (selection)

Osman I.

The first killing of a blood relative is said to have happened to the founder of the dynasty and namesake of the later empire. As Neşrî in his universal history titled Cihān-nümā 'Weltschau, Weltspiegel', of which only the sixth and last part has survived , Osman I is said to have killed his uncle Dündar Bey with an arrow in 1298 or 1302. However, it is unclear whether this description is true. The grave of Dündar Bey is said to be between the villages of Çakırpınar ( Bilecik ) and Köprühisar ( Yenişehir ).

Bayezid I.

The first preventive killing of a non-rebellious prince took place when Bayezid I came to power , known as yıldırım 'weather beam , lightning', who followed his father, who had died in June or August 1389. Ottoman and occidental reports diverge in detail about the circumstances of Murad I's death . According to a letter contained in the controversial Mecmūʿa-ʾı Münşeʾātü s-selāṭīn ('Collection of Briefs of the Sultans') by State Secretary Feridun Ahmed Bey (d. 1583), which is identified as a copy of an edict of Bayezid the Weather Ray, Murad I. after the victorious battle on the blackbird field by someone named Miloş Ḳopilik (میلوش قوپیلك) known assassins were maliciously murdered with a poison-coated dagger hidden in their sleeve.

In any case, shortly after Murad I's death, his younger son Yakub was executed. The question of whether the decision to murder Yakub was made of Bayezid I's own free will or under pressure from high dignitaries cannot be answered unequivocally. While the later, High Ottoman chroniclers Hoca Sâdeddin Efendi (d. 1599) and Solakzâde Mehmed Hemdemî (d. 1658) report that the viziers and ulamas had the killing in view of the Koran passage«الفتنة اشد من القتل» / al-fitnatu ʾašaddu mina l-qatl (i) / ' Fitna is worse than killing' ( Sura 2, verse 191) at least approved, one searches in vain for corresponding mentions in earlier sources. It is remarkable in this context that although fitna is to be understood in the sense of "riot, disorder", Yakub was killed before he had even found out about his father's death.

The body of Yakub was transferred to Bursa together with that of his father (see Meşhed-i Hüdavendigar ) and is buried there within the Hudâvendigâr complex in the Çekirge district founded by Murad I ( map ).

Murad II

In 1422 Murad II had his "false" uncle Mustafa, who was actually a son of Bayezid I , publicly hanged . The public execution and deliberate deviation from the usual type of execution made it clear that the “false” Mustafa was not considered to belong to the Osman family. Âşıkpaşazâde describes the execution of Mustafas as follows:

“[And] nd arrested him [ie Mustafa]. They took him back to Edrene and there they hung him on the tower of the castle. And all the people came to look at him. "

Mehmed II

Murad II died on February 3, 1451 in the main residence of Edirne. Grand Vizier Çandarlı Halil Pascha immediately sent a courier with the mourning message to Manisa, where Prince Mehmed had again been as governor of the Sanjak Saruhan since 1446 . About two weeks after his father's death, Mehmed arrived in Edirne, where on February 18, 1451, he again ascended the Ottoman throne. Whether the takeover of Mehmed II went completely smoothly cannot be determined more precisely: While Chalkokondyles reports on an uprising of the Janissaries [?] Ultimately prevented by the Grand Vizier, there is no reference to such unrest in Ottoman chronicles.

There were no disputes over the throne, as the death of Murad II had also been concealed with regard to Prince Orhan, a presumed grandson of Emir Suleyman, who had been a hostage in Constantinople since childhood, and Küçük Ahmed, the only living (half-) Brother Mehmed, still in infancy ( küçücük , ṭıfl-ı nā-resīde ). The fact that Yusuf Adil Shah , the founder of the Adil Shahi dynasty and first sultan of Bijapur , was a son of Murad II and that he escaped fratricide by Mehmed II only on the initiative of his mother, is more likely due to a need for legitimation and is allowed to In the absence of any source, this is more than doubtful. Küçük Ahmed, born around 1450 by the princess' daughter ( İsfendiyar ) Hadice Halime Hatun, was probably asphyxiated in the bath by Evrenosoğlu Ali Bey on the orders of the new sultan and sent to Bursa for burial with the body of Murad II . Ali Bey himself was not, as Dukas reported, executed shortly after the prince murder, but took part as Akıncı leader in the campaign in Wallachia and accordingly died after 1462. Prince Orhan died in the course of the siege and subsequent conquest of Constantinople (hereinafter Istanbul ), the exact circumstances of his death being inconsistent. It is unclear whether he threw himself off the city walls out of desperation and resignation or whether soldiers on the run seized him and executed him. In any case, his severed head was brought to the Sultan.

Bayezid II

Mehmed II died on May 3, 1481 at the start of a campaign. His death was kept secret and the body was secretly transferred from the field camp near Gebze to Istanbul. Assumptions about the poisonous death of the ruler are based on a lyrical insert in the chronicle of the Âşıkpaşazâde , but cannot be confirmed by other sources.

Grand Vizier Karamânî Mehmed Pasha sent couriers to Amasya ( Bayezid ) and Konya ( Cem ) to notify the two sons . However, the two messengers sent to Cem were intercepted and arrested by order of the Anatolian Beğlerbeğs Arnavud Sinan Pasha, a son-in-law of Bayezid. Despite all efforts of Karamânî Mehmed Pasha to hide the death of Mehmed II, the Janissaries learned of the Sultan's death - probably at the instigation of Ishak Pasha . Angry, the soldiers returned to Istanbul and sacked the city. They also penetrated the grand vizier's house and killed him in his reception room. The impaled head of the Grand Vizier was carried through Istanbul for days. In order to calm the situation until Bayezid's arrival, Ishak Pasha put his son Korkud on the throne on May 4, 1481 as imperial administrator. Korkud stayed with his brothers Alemşah and Mahmud as well as Cem's son Oğuzhan since their circumcision in 1480 as hostages and guarantors for the good behavior of the fathers in Istanbul.

On May 22, 1481 Bayezid II ascended the throne and had the funeral ceremony held for his father, whereas Cem in Bursa had his name mentioned in the pulpit prayer ( ḫuṭba ) and coins minted as an expression of his sovereignty . On June 20, 1481, the grand army achieved a victory over Cem, who then fled.

On November 18, 1482, Bayezid II had the former Grand Vizier (1474–1477) Gedik Ahmed Pasha , whose loyalty he had long doubted, executed. A little later, in the last decade of the month of Şevvāl in the year 887 / 2nd to 11th December 1482, the Sultan issued the order addressed to a certain Iskender (ḥükm) to secretly strangle Cem's son. On the death of his son Oğuzhan, Cem wrote an elegy (mers̠īye) .

Prince Cem died after temporary stays in Rhodes, Nice, Les Échelles near Chambéry and Rome, on 29th Cemāẕī l-evvel 900 / 25th February 1495 in Castel Capuano in Naples . Whether his death was the result of poisoning (Cantarella?) Or an illness (pneumonia or malaria?) Is controversial, although the biography of Vāḳıʿāt-ı Sulṭān Cem 'incidents of Sultan Cem, presumably written down by Haydar Bey, a follower of the prince, is evident 'finds no evidence of poisoning. After ablution, funeral prayer and removal of internal organs, the body was embalmed, wrapped in an oilcloth and placed in a lead coffin (ḳurşun tābūt) .

When the news of the prince's demise became known to the Sultan on April 20 of the same year, he ordered the performance of the funeral prayer in absentia and a three-day mourning. Charles VIII is said to have offered the Sultan to hand over the body to Cem for a payment of 5,000 ducats. About three months after the prince's death, the remains were brought to Gaeta by sea . At the end of 1496 the body returned to Naples and was kept there in the Castel dell'Ovo . It was not until 1499, after lengthy diplomatic negotiations, that Frederick I allowed the repatriation to his home country and the body was sent by ship via Lecce to Mudanya and from there to Bursa , where Bayezid II finally bought it for her brother Mustafa (d. 1474) was buried in the mausoleum ( map ) in the Murâdiye complex.

Suleyman I.

In 1520, Suleyman I took over the rule relatively smoothly, as there were no princes who could dispute the throne for him. His foster brother (see milk relationship ) Beşiktaşlı Yahyâ Efendi was not entitled to inheritance. Even before he came to power, Suleyman I had sons Murad, Mahmud and Mustafa, born to at least two different concubines. While marching back from the successful siege of Belgrade , the Sultan received news of Murad's death (October 19, 1521) and shortly after his arrival in Istanbul on October 29, 1521, Prince Mahmud died of smallpox . In the same year Hürrem (Roxelane) gave birth to his future wife, Prince Mehmed. Between 1523 and 1530, the connection with Hürrem resulted in four more sons - Abdullah (d. 1526 as a toddler), Selim, Bayezid and Cihangir.

| Concubines |

Suleyman I (ruled 1520–1566) |

Hürrem Sultan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Murad (died 1521) |

Mahmud (died 1521) |

Mustafa (executed in 1553) |

Mehmed (died 1543) |

Abdullah (died 1526) |

Selim II (ruled 1566–1574) |

Bayezid (executed 1561) |

Cihangir (died 1553) |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mehmed (executed in 1554) |

6 sons (including Murad III ) |

5 sons (executed in 1561) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

While Mustafa as the eldest prince enjoyed the special care of his grandmother Hafsa and the grand vizier Ibrahim Pascha , after their death or execution Mehmed became the favorite son of Suleyman I. In 1541, Mustafa had to give up his governorship of Saruhan in favor of Mehmed in 1541. Contrary to custom, Hürrem did not accompany her firstborn to Manisa, but stayed in Istanbul. When Mehmed died unexpectedly of smallpox on November 7, 1543, the Sultan was deeply dismayed and had the body brought to Istanbul, not as usual, to Bursa, and there on October 16, 1543 in the complex designed by the architect Sinan and (later ) bury the monumental building known as Şeh-zāde cāmiʿ 'Prince's Mosque'. In the following years, however, Mustafa was not able to rise again in the father's favor, but rather fell further into disfavor. At the end of August 1553, Suleyman I set out with his troops and accompanied by his youngest son Cihangir from Üsküdar and called on his sons to join him. In the second week of September 1553, the armed forces reached Yenişehir , where Prince Bayezid from the royal seat of Kütahya had also gone. After celebrating the festival of the breaking of the fast , Bayezid moved to Edirne as a deputy and the main army further to the southeast, which Prince Selim and his units joined in Bolvadin . On October 5, 1553, a field camp was set up in Aktepe (also Akhöyük, Aköyük or Akyüz) near Ereğli , where Mustafa arrived with his army.

Right thumbnail: The one with a piece of Kaaba enveloped -Ceiling and turban , caftan , belt and Handschar coffin adorned the strangled in Bursa Prince son Mehmed. It is not clear who the person depicted crying is.

Miniatures from the Hüner-nāme , vol. 2, around 1588. Istanbul, Library of the Topkapi Seraglio Museum (TSMK), Hazine, inv. 1524, fol. 168 b (left) and 171 a (right)

Before Mustafa could enter the grand tent, he had to get rid of his weapons. Inside he met the father instead of several executioners waiting for him who immediately pounced on him. Although the prince was initially able to assert himself as the stronger in the struggle for survival, he was ultimately strangled by the new Mahmud Agha, who later received the nickname Zāl , was promoted to pasha and a son-in-law of Selim II, and strangled by the Dilsiz . The stable master and the prince's standard bearer were beheaded. As a sign of betrayal, Mustafa's body is said to have been displayed on a Persian carpet (according to Western sources). In May 1554, Mehmed, Mustafa's son, born in 1546, was also executed in Bursa on the orders of the Sultan.

It is not known why Mustafa was executed. In any case, contemporary sources accuse Hürrem and her son-in-law Rustem Pascha . For example, the year of Mustafa's death in 960/1553 is often indicated with the chronogram (see abdschad )«مکر رستم» / MEKR-i Rustem / Guile Rustem 'defined and numerous written on the death of Mustafa's Elegies blame Rustem Pasha, Hürrem and Sultan himself. The most famous known among the 15 Trust Roden is that of soldiers and Dīwāndichters Taşlıcalı Yahyâ (d. 1582 ), which begins as follows:

مدد مدد بو جهانك یقلدی بر یانی

اجل جلالیلری آلدی مصطفی خانی

meded meded bu cihānuñ yıḳıldı bir yanı

ecel celālīleri aldı Muṣṭafā Ḫānı

“God save us! The world falls over our ears.

The rioters of death have seized Mustafa Han. "

Even Hans Dernschwam that in the wake of a delegation King I. Ferdinand the end of August had arrived in Istanbul in 1553, described the circumstances that led to the execution of the Prince Mustafa, according to the then prevailing public opinion as follows:

"The reason why he [ie the Sultan] in [di Mustafa] let blow and choke, so that all the people and also the ianczarn were favorable to Mustafa and named a sultan (that is a khonig). Dan khain other sultan is the only khaiser. Also, that Mustaffa [!] Waited alone until his father, the khaiser, was gone with death in the course of vmkhomen who. So he drowned out his fellow fellow brothers, Selinus, Baiasetes and Hangier, and became khaiser. The hot die kayserin, who is a rewsian slave, vnd the rustan bascha, who is ir daughter hot vnd of the kayser ayden, and the obriste bascha still the kayser, […] don't like wol leyden. Vnd doubtfully located the khaiser in oren and made Mustafa suspicious and in the khaisers fang splendid. "

On November 8, 1553, Suleyman and his army reached Aleppo to spend the winter there. The youngest sultan's son died there on November 27, 1553, although the circumstances of death are unclear. It is widely believed that the already ailing Cihangir died of grief over the execution of his half-brother. In contrast, pleurisy or even suicide motivated by fear or grief are also named as the cause of death . His body was brought to Istanbul and buried in the doorway of his brother Mehmed.

Mustafa was buried in Bursa. His mausoleum, which was built (or rebuilt) between 1571 and 1573 under the rule of his half-brother Selim II and in which his mother, who died in 1581, also found her final resting place, is located within the Murâdiye complex ( map ).

Murad III

When Selim II died in 1574 at the age of 50, he had six sons. The oldest of these was Murad, born by the favorite Nurbânû in July 1546, who had received Saruhan's governorship from his grandfather Suleyman I in March 1562 and has since resided in Manisa. The other sons of Selim II were born after 1566 and were still in Topkapı Palace when he died .

Notified by the Grand Vizier Sokollu Mehmed Pasha of the death of his father, Murad reached the capital on the night of December 21st to 22nd, 1574, ascended as Murad III. took the throne and had his five brothers - Mustafa, Osman, Suleyman, Cihangir and Abdullah - strangled.

The princes were buried with their father on the southwest side of Hagia Sophia . The mausoleum ( map ), commissioned by the architect Sinan during the reign of Selim II , was completed in 1576/1577.

Mehmed III.

Murad III died in January 1595. Of his more than 100 descendants, 20 sons (and 27 daughters) survived him. The eldest son Mehmed was appointed governor of Saruhan at the end of 1583. On January 27, 1595 - a Friday - Mehmed arrived in Istanbul and ascended the throne. The name of the new sovereign was mentioned in the Friday sermon . The following day, Mehmed III. strangle his 19 brothers. The prayers for the dead were from the kingdom, with the participation of the Great Scheichülislam Bostanzâde Mehmed Efendi passed. The princes were buried with their father. In the mausoleum of Murad III, begun by the court architect Dâvud Agha (d. Around 1598) and completed in 1599 by Dalgıç Ahmed Agha (d. 1607). ( Map ) a total of 54 people are said to be buried, with a total of 50 Ṣandūḳa (empty wooden sarcophagi) in the building today .

In 1603 Mehmed III. strangling his son Mahmud before he died at the end of the same year at the age of 37.

17th century

Successor of Mehmed III. was his thirteen-year-old son Ahmed I. In view of the sultan's childhood and the resulting childlessness, his mentally ill brother Mustafa, who was one to two years younger than him, was left alive in view of dynastic continuity. When Ahmed I died on November 22nd, 1617 at the age of 27, he left seven sons in addition to this brother and the question arose as to who should succeed on the throne: Mustafa as the oldest member of the dynasty or the thirteen-year-old Osman as eldest son of the late regent. First Mustafa I came to the throne, which for the first time broke the principle of succession from father to son (ʿamūd-ı nesebī) , but because of his weakness of mind, he could only stay on the throne for a few months, so in the end he did Osman II came to power.

| Mahmud (executed 1603) |

Ahmed I (ruled 1603-1617) |

Mustafa I (ruled 1617/1618 and 1622/1623) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Osman II (ruled 1618–1622) |

Mehmed (executed 1621) |

Murad IV (ruled 1623-1640) |

Bayezid (executed 1635) |

Suleyman (executed 1635) |

Kasım (executed 1638) |

Ibrahim (ruled 1640-1648) |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

A few years later - in preparation for the Polish campaign - Osman II decided to have his brother Mehmed (born March 8, 1605), who was only a few months younger and whom he now perceived as a threat to his throne, executed. After the Sheikhul Islam Hocazâde Esad Efendi had refused to prepare a corresponding fatwa , the Sultan successfully turned to the Kazasker of Rumelien Taşköprizâde Kemâleddin Efendi ; Mehmed was executed on January 12, 1621.

On May 19, 1622 Osman II was deposed and killed. Mustafa I became sultan again, but he was again unable to hold onto the throne, so that on September 9, 1623 Murad IV ascended the throne in childhood. He later had his half-brothers Bayezid and Süleyman - in August 1635 - and - in February 1638 - his full brother Kasım strangled.

19th century

At the end of May 1807, the janissaries, led by Kabakçı Mustafa , revolted and dethroned the "unbelieving sultan" Selim III. who tried to reorganize the army with the help of European instructors ( Nizâm-ı Cedîd ), and set Mustafa IV as ruler. This intended to reverse previous reforms, whereupon Alemdar Mustafa Pascha from Rustschuk marched with his army to Istanbul to reinstate Selim as sultan. In order to thwart his impending disempowerment, Mustafa IV. Issued the death warrant for his predecessor Selim and his half-brother Mahmud. While Selim was bloodily killed, Mahmud - now the only legitimate heir to the throne still alive - managed to escape the executioners and, on July 28, 1808, to ascend the throne with the help of Alemdar Mustafa Pasha. On November 14, 1808, Alemdar Mustafa Pascha was killed in another janissary uprising. A few days later, on November 17, 1808, Mahmud II had his half-brother and predecessor Mustafa strangled to secure his throne. The body was buried in the doorway of the father, Abdülhamids I , southeast of the Yeni Cami ( map ).

literature

- Mehmet Akman: Osmanlı Devletinde Kardeş Katli. Eren Yayıncılık, Istanbul 1997, ISBN 975-7622-65-6 (also dissertation under the title: Osmanlı Hukukunda Kardeş Katli Meselesi , Marmara University Istanbul 1995).

- İbrahim Artuk: Osmanlılarda Veraset-i Saltanat ve Bununla İlgili Sikkeler. In: İstanbul Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakanschesi Tarih Dergisi. No. 32, 1979, ISSN 1015-1818 , pp. 255-280 ( PDF file; 4.5 MB ).

- Haldun Eroğlu: Osmanlı Devletinde Şehzadelik Kurumu. Akçağ Yayınevi, Ankara 2004, ISBN 975-338-517-X (also dissertation under the title: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nda şehzadelik kurumu (Klasik Dönem) , Ankara University 2002), pp. 193-217.

- Colin Imber: The Ottoman Empire, 1300-1650. The Structure of Power. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, et al. a. 2002, ISBN 0-333-61386-4 , pp. 96-115.

- Ahmet Mumcu: Osmanlı Devleti'nde Siyaseten Katl. 3rd, revised edition. Phoenix Yayınevi, Ankara 2007, ISBN 9944-931-14-4 (also dissertation, University of Ankara 1962), pp. 165–182.

- Abdülkadir Özcan: Atam Dedem Kanunu. Kanunnâme-i Âl-i Osman. Extended new edition. Yitik Hazine Yayınları, Istanbul 2013, ISBN 978-9944-766-56-2 .

References and comments

- ↑ Halil İnalcık: The Ottoman Succession and its Relation to the Turkish Concept of Sovereignty. Translated from Turkish by Douglas Howard. In: Halil İnalcık: The Middle East and the Balkans under the Ottoman Empire. Essays on Economy and Society (= Indiana University Turkish Studies and Turkish Ministry of Culture Joint Series. Vol. 9). Indiana University Press, Bloomington (Indiana) 1993, pp. 37-69; First publication in Turkish: Halil İnalcık: Osmanlılar'da Saltanat Verâseti Usûlü ve Türk Hakimiyet Telâkkisiyle İlgisi. In: Ankara Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakanschesi Dergisi. Vol. 14, No. 1, 1959, ISSN 0378-2921 , pp. 69-94 ( PDF file; 13.3 MB ).

- ↑ Halil İnalcık: The Ottoman Empire. The Classical Age 1300-1600. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1973, ISBN 0-297-99490-5 , p. 59.

- ↑ Halil İnalcık: The Ottoman Succession and its Relation to the Turkish Concept of Sovereignty. Translated from Turkish by Douglas Howard. In: Halil İnalcık: The Middle East and the Balkans under the Ottoman Empire. Essays on Economy and Society (= Indiana University Turkish Studies and Turkish Ministry of Culture Joint Series. Vol. 9). Indiana University Press, Bloomington (Indiana) 1993, pp. 37-69, here: p. 60.

- ↑ Donald Quataert: The Ottoman Empire, 1700-1922. (= New Approaches to European History. Vol. 34). 2nd Edition. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge u. a. 2005, ISBN 978-0-521-83910-5 , p. 90. Original: "survival of the fittest".

- ↑ Colin Imber: The accession to the throne of the Ottoman sultans. Developing a ceremony. In: Marion Steinicke, Stefan Weinfurter (eds.): Investiture and coronation rituals. Assertions of power in a cultural comparison. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2005, ISBN 3-412-09604-0 , pp. 291–304, here: p. 295; Halil İnalcık: The Ottoman Succession and its Relation to the Turkish Concept of Sovereignty. Translated from Turkish by Douglas Howard. In: Halil İnalcık: The Middle East and the Balkans under the Ottoman Empire. Essays on Economy and Society (= Indiana University Turkish Studies and Turkish Ministry of Culture Joint Series. Vol. 9). Indiana University Press, Bloomington (Indiana) 1993, pp. 37-69, here: p. 60.

- ^ Friedrich Giese: The seniorate in the Ottoman ruling house. In: Friedrich Kraelitz-Greifenhorst, Paul Wittek (Hrsg.): Communications on Ottoman history. Reprint of the edition from 1923–1926. Vol. 2, Biblio, Osnabrück 1972, ISBN 3-7648-0510-2 , pp. 248-256, here: p. 253; Ahmet Mumcu: Osmanlı Devleti'nde Siyaseten Katl. 3rd, revised edition. Phoenix Yayınevi, Ankara 2007, ISBN 9944-931-14-4 , p. 174.

- ↑ Nuran Tezcan: Manisa after Evliyā Çelebi. From the ninth volume of the Seyāḥat-nāme (= Evliya Çelebi's book of travels. Vol. 4). Brill, Leiden / Boston / Cologne 1999, ISBN 90-04-11485-8 (also dissertation, University of Bamberg 1996), p. 232 note 300.

- ↑ Enis Karakaya: Manisa. Mimari. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 27, Ankara 2003, pp. 583-588, here: p. 587 ( PDF file; 4.8 MB ).

- ↑ 'King's Son, Prince'. It is believed that the prince title was introduced in the reign of Mehmed I (1413-1421); see also Christine Woodhead: Sh ehzāde. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 9, Brill, Leiden 1997, p. 414.

- ↑ Josef Matuz: The Ottoman Empire. Baseline of its history. 6th edition. Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-89678-703-3 , p. 87; Haldun Eroğlu: Osmanlı Devletinde Şehzadelik Kurumu. Akçağ Yayınevi, Ankara 2004, ISBN 975-338-517-X , pp. 106, 112; İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı: Osmanlı Tarihi. 10th edition. Vol. 1, Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, Ankara 2011, ISBN 978-975-16-0011-0 , p. 499.

- ↑ On this in detail Haldun Eroğlu: Osmanlı Devletinde Şehzadelik Kurumu. Akçağ Yayınevi, Ankara 2004, ISBN 975-338-517-X , p. 108 ff .; see. also Nuran Tezcan: Manisa after Evliyā Çelebi. From the ninth volume of the Seyāḥat-nāme (= Evliya Çelebi's book of travels. Vol. 4). Brill, Leiden / Boston / Cologne 1999, ISBN 90-04-11485-8 (also dissertation, University of Bamberg 1996), p. 25 ff.

- ↑ See İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı: Osmanlı Devletinin Saray Teşkilâtı. 3. Edition. Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, Ankara 1988, ISBN 975-16-0041-3 , p. 52.

- ^ Zeynep Tarım Ertuğ: XVI. Yüzyıl Osmanlı Devleti'nde Cülûs ve Cenaze Törenleri (= Osmanlı Eserleri Dizisi. Vol. 16). Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Kültür Bakanlığı Yayınları, Ankara 1999, ISBN 975-17-2151-2 (also dissertation, University of Istanbul 1995), p. 150.

- ↑ Cf. Colin Imber: The ascension of the throne of the Ottoman sultans. Developing a ceremony. In: Marion Steinicke, Stefan Weinfurter (eds.): Investiture and coronation rituals. Assertions of power in a cultural comparison. Böhlau Verlag, Cologne 2005, ISBN 3-412-09604-0 , pp. 291-304, here: pp. 291 f.

- ^ İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı: Osmanlı Devletinin Saray Teşkilâtı. 3. Edition. Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, Ankara 1988, ISBN 975-16-0041-3 , pp. 46, 120.

- ↑ Halil İnalcık: The Ottoman Empire. The Classical Age 1300-1600. Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London 1973, ISBN 0-297-99490-5 , p. 60; see. also İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı: Osmanlı Devletinin Saray Teşkilâtı. 3. Edition. Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, Ankara 1988, ISBN 975-16-0041-3 , p. 140.

- ↑ On the prince's prison see G. Veinstein: Ḳafes. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 12, Brill, Leiden 2004, pp. 503-505.

- ↑ a b M. d'Ohsson: Tableau Général de l'Empire Othoman. Vol. 1, Imprimerie de Monsieur, Paris 1788, pp. 285 f .; critical of the sterile means and the method of killing Friedrich Giese: The seniorate in the Ottoman ruling house. In: Friedrich Kraelitz-Greifenhorst, Paul Wittek (Hrsg.): Communications on Ottoman history. Reprint of the edition from 1923–1926. Vol. 2, Biblio, Osnabrück 1972, ISBN 3-7648-0510-2 , pp. 248-256, here: p. 254.

- ^ İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı: Osmanlı Devletinin Saray Teşkilâtı. 3. Edition. Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, Ankara 1988, ISBN 975-16-0041-3 , p. 115.

- ↑ See İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı: Osmanlı Devletinin Saray Teşkilâtı. 3. Edition. Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, Ankara 1988, ISBN 975-16-0041-3 , p. 46 f.

- ^ Friedrich Giese: The seniorate in the Ottoman ruling house. In: Friedrich Kraelitz-Greifenhorst, Paul Wittek (Hrsg.): Communications on Ottoman history. Reprint of the edition from 1923–1926. Vol. 2, Biblio, Osnabrück 1972, ISBN 3-7648-0510-2 , pp. 248-256, here: pp. 255 f .; İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı: Osmanlı Devletinin Saray Teşkilâtı. 3. Edition. Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, Ankara 1988, ISBN 975-16-0041-3 , p. 49; Hakan T. Karateke: Who is the Next Ottoman Sultan? on the efforts for the introduction of the Primogenitur in the 19th century . Attempts to Change the Rule of Succession during the Nineteenth Century. In: Itzchak Weismann, Fruma Zachs (Ed.): Ottoman Reform and Muslim Regeneration. Studies in Honor of Butrus Abu-Manneh (= Library of Ottoman Studies. Vol. 8). IB Tauris, London / New York 2005, ISBN 978-1-85043-757-4 , pp. 37-53 ( PDF file; 1.6 MB ).

- ^ Translation of Friedrich von Kraelitz-Greifenhorst: The constitutional laws of the Ottoman Empire. Publishing house of the Research Institute for the East and the Orient, Vienna 1919, p. 31.

- ↑ Quoted from Salomon Schweigger: To the court of the Turkish sultan. Edited and edited by Heidi Stein. VEB FA Brockhaus Verlag, Leipzig 1986, p. 142.

- ↑ Cod. HO 143 and Cod. AF 547 ; see also Gustav Flügel: The Arabic, Persian and Turkish manuscripts of the Imperial and Royal Court Library in Vienna. Vol. 3, Kk Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, Vienna 1867, p. 248 (No. 1813, 3; online ) and p. 254 (No. 1820, 3; online ).

- ^ Joseph von Hammer: The Ottoman Empire State Constitution and State Administration. Vol. 1 (State Constitution), Camesina, Vienna 1815, pp. 87–101; the fratricide law can be found here under the title Kanun der Securing Rule of the Throne on p. 98; See also Konrad Dilger: Studies on the history of the Ottoman court ceremony in the 15th and 16th centuries (= contributions to knowledge of Southeast Europe and the Near East. Vol. 4). Trofenik, Munich 1967 (also dissertation, Ludwig Maximilians University Munich 1967), p. 9; Friedrich Kraelitz-Greifenhorst: Ḳānūnnāme Sultan Meḥmeds the Conqueror. The oldest Ottoman criminal and financial laws. In: Friedrich Kraelitz-Greifenhorst, Paul Wittek (Hrsg.): Communications on Ottoman history. Reprint of the edition from 1921–1922. Vol. 1, Biblio, Osnabrück 1972, ISBN 3-7648-0510-2 , pp. 13-48, here: p. 15 footnote 7.

- ↑ Meḥmed ʿĀrif (Ed.): Ḳānūn-nāme-i āl-i ʿOs̠mān. Ṣūret-i ḫaṭṭ-ı hümāyūn-ı sulṭān Meḥemmed ḫān anāra 'llāhu burhānahu. In: Taʾrīḫ-i ʿos̠mānī encümeni mecmūʿası. Annexe to Vol. 3, No. 13 and Vol. 3, No. 14, Istanbul 1330 (1912); See also Konrad Dilger: Studies on the history of the Ottoman court ceremony in the 15th and 16th centuries (= contributions to knowledge of Southeast Europe and the Near East. Vol. 4). Trofenik, Munich 1967 (also dissertation, Ludwig Maximilians University Munich 1967), p. 8 f.

- ↑ Abdülkadir Özcan: Atam Dedem Kanunu. Kanunnâme-i Âl-i Osman. Extended new edition. Yitik Hazine Yayınları, Istanbul 2013, ISBN 978-9944-766-56-2 , p. XV; the manuscript of the first volume of the chronicle is in the Austrian National Library ( Cod. AF 63 ) and had been known for some time; see Gustav Flügel: The Arabic, Persian and Turkish manuscripts of the Imperial and Royal Court Library in Vienna. Vol. 2, Kk Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, Vienna 1865, pp. 94–96 (No. 864; online ); see. also Joseph von Hammer: History of the Ottoman Empire. Vol. 4, Hartleben, Pest 1829, p. 601; Franz Babinger: The historians of the Ottomans and their works. Otto Harrassowitz, Leipzig 1927, p. 186.

- ↑ Hans Georg Majer (review): Dilger, Konrad: Investigations into the history of the Ottoman court ceremony in the 15th and 16th centuries. In: Southeast Research . Vol. 28, 1969, pp. 464-467, here: p. 465; the copy of the Ḳānūn-nāme contained in the second volume of Koca Hüseyin's Chronicle is printed as a facsimile in Abdülkadir Özcan: Atam Dedem Kanunu. Kanunnâme-i Âl-i Osman. Extended new edition. Yitik Hazine Yayınları, Istanbul 2013, ISBN 978-9944-766-56-2 , p. 47 ff., Relevant here: fol. 277b, especially lines 8 ff.

- ↑ Anna Stepanovna Tveritinova: The Turkish Manuscript of Qoǧa Ḥusejn's Chronicle Bedāʾiʿ ül-weqāʾiʿ (Volume II) from the Collection of the Institute of Oriental Studies (Leningrad Branch), USSR Academy of Sciences. In: Herbert Franke (Hrsg.): Files of the twenty-fourth international Congress of Orientalists. Munich, August 28 to September 4, 1957. Steiner, Wiesbaden 1959, pp. 398-402, here: p. 399.

- ↑ Anna Stepanovna Tveritinova, Jurij Ašotovič Petrosjan (ed.): Beda'i 'ul-Veka'i' (Udivitel'nye sobytija) (= Pamjatniki literatury narodov Vostoka. Teksty. Bol'šaja serija. Vol. 14). 2 volumes, Izdat. Vostočnoj Literatury, Moscow 1961; see also Abdülkadir Özcan: Koca Hüseyin. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 26, Ankara 2002, p. 130 f., Here: p. 131 ( PDF file; 1.7 MB ).

- ↑ The aforementioned preface is not included in the copy of the Ḳānūn-nāme contained in the second volume of Koca Hüseyin's Chronicle , but the content of the same is given in abbreviated form. The person responsible for the compilation is called Hüseyin at Koca«لیثي زاده محمد افندي» / Leys̠ī-zāde Meḥemmed Efendi ; see Abdülkadir Özcan: Atam Dedem Kanunu. Kanunnâme-i Âl-i Osman. Extended new edition. Yitik Hazine Yayınları, Istanbul 2013, ISBN 978-9944-766-56-2 , fol. 277b line 5.

- ↑ So Halil İnalcık: Osmanlı Hukukuna Giriş. Örfî-Sultanî Hukuk ve Fatih'in Kanunları. In: Ankara Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakanschesi Dergisi. Vol. 13, No. 2, 1958, ISSN 0378-2921 , pp. 102–126, here: p. 113 ( PDF file; 10.9 MB ); Gülru Necipoğlu: Architecture, Ceremonial, and Power. The Topkapi Palace in the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA / London / New York 1991, p. 16; On the contrary, see Konrad Dilger: Studies on the history of the Ottoman court ceremony in the 15th and 16th centuries (= contributions to knowledge of Southeast Europe and the Near East. Vol. 4). Trofenik, Munich 1967 (also dissertation, Ludwig Maximilians University Munich 1967), p. 14 ff.

- ↑ Meḥmed ʿĀrif (Ed.): Ḳānūn-nāme-i āl-i ʿOs̠mān. In: Taʾrīḫ-i ʿos̠mānī encümeni mecmūʿası. Annex to Vol. 3, No. 14, Istanbul 1330 (1912), p. 27.

- ^ Translation of Konrad Dilger: Studies on the history of the Ottoman court ceremony in the 15th and 16th centuries (= contributions to knowledge of Southeast Europe and the Near East. Vol. 4). Trofenik, Munich 1967 (also dissertation, Ludwig Maximilians University Munich 1967), p. 30.

- ↑ The copy of Ḳānūn-nāme contained in the second volume of Koca Hüseyin's Chronicle is printed as a facsimile in Abdülkadir Özcan: Atam Dedem Kanunu. Kanunnâme-i Âl-i Osman. Extended new edition. Yitik Hazine Yayınları, Istanbul 2013, ISBN 978-9944-766-56-2 , p. 47 ff., Relevant here: fol. 281b lines 10-12.

- ↑ Haldun Eroğlu: Osmanlı Devletinde Şehzadelik Kurumu. Akçağ Yayınevi, Ankara 2004, ISBN 975-338-517-X , p. 197 f .; on bowstring (çile / kiriş) and lasso (kemend) see in detail Joachim Hein: Bowcraft and archery among the Ottomans. I. Continuation. In: Islam. Vol. 15, Issue 1, 1926, ISSN 0021-1818 , pp. 1-78, here: pp. 1-9 and 55-57.

- ↑ Fahamettin Basar: Mustafa Çelebi, Düzme. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 31, Istanbul 2006, p. 292 f. ( PDF file; 1.7 MB ).

- ↑ Mehmet Akman: Osmanlı Devletinde Kardeş Katli. Eren Yayıncılık, Istanbul 1997, ISBN 975-7622-65-6 , p. 162 f .; Ahmet Mumcu: Osmanlı Devleti'nde Siyaseten Katl. 3rd, revised edition. Phoenix Yayınevi, Ankara 2007, ISBN 9944-931-14-4 , p. 181 f.

- ↑ Mevlānā Meḥemmed Neşrī: Kitāb-ı Cihān-nümā. Edition Franz Taeschner (Ed.): Ǧihānnümā. The old Ottoman chronicle of Mevlānā Meḥemmed Neschrī. Vol. 1 (Cod. Menzel), Otto Harrassowitz, Leipzig 1951, pp. 25, 29; Vol. 2 (Cod. Manisa 1373), Otto Harrassowitz, Leipzig 1955, p. 37; Mehmet Akman: Osmanlı Devletinde Kardeş Katli. Eren Yayıncılık, Istanbul 1997, ISBN 975-7622-65-6 , p. 43 ff .; M. Tayyib Gökbilgin: Osman I. In: İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 9, Millî Eğitim Basımevi, Istanbul 1964, pp. 431-443, here: p. 437; Haldun Eroğlu: Osmanlı Devletinde Şehzadelik Kurumu. Akçağ Yayınevi, Ankara 2004, ISBN 975-338-517-X , p. 200.

- ^ Zeynep Tarım Ertuğ: XVI. Yüzyıl Osmanlı Devleti'nde Cülûs ve Cenaze Törenleri (= Osmanlı Eserleri Dizisi. Vol. 16). Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Kültür Bakanlığı Yayınları, Ankara 1999, ISBN 975-17-2151-2 (also dissertation, University of Istanbul 1995), p. 4.

- ↑ Bayezid I's secret decree on the death of Murad I, addressed to the Qādī of Bursa and dated from the middle decade of Şaʿbān 791/5 to 14 August 1389; Copy in Ferīdūn Aḥmed Beğ: Mecmūʿa-ʾı münşeʾātü s-selāṭīn. 2nd Edition. Vol. 1, Taḳvīmḫāne-i ʿāmire, Istanbul 1274 (1858), p. 115 f.

- ↑ Haldun Eroğlu: Osmanlı Devletinde Şehzadelik Kurumu. Akçağ Yayınevi, Ankara 2004, ISBN 975-338-517-X , p. 201.

- ↑ Ḫoca Saʿdeddīn: Tācü t-tevārīḫ. Vol. 1, Ṭabʿḫāne-i ʿāmire, Istanbul 1279 (1862), p. 124; Ṣolaḳ-zāde Meḥmed Hemdemī: Ṣolaḳ-zāde tārīḫi (Tārīḫ-i Ṣolaḳ-zāde). Maḥmūd Beğ maṭbaʿası, Istanbul 1297 (1879/80), p. 50.

- ↑ Cf. Konrad Dilger: Studies on the history of the Ottoman court ceremony in the 15th and 16th centuries (= contributions to knowledge of Southeast Europe and the Near East. Vol. 4). Trofenik, Munich 1967 (also dissertation, Ludwig Maximilians University Munich 1967), p. 33.

- ↑ Cf. Mehmet Akman: Osmanlı Devletinde Kardeş Katli. Eren Yayıncılık, Istanbul 1997, ISBN 975-7622-65-6 , p. 151.

- ↑ Fahamettin Basar: Mustafa Çelebi, Düzme. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 31, Istanbul 2006, p. 292 f. ( PDF file; 1.7 MB ).

- ↑ Translation ʿĀşıḳ-paşa-zāde: From the shepherd's tent to the high gate. The early days and rise of the Ottoman Empire according to the chronicle "Memories and Times of the House of Osman" by the dervish Ahmed, called ʿAşik-Paşa-Son (= Ottoman historians. Vol. 3). 2nd Edition. Translated, introduced and explained by Richard F. Kreutel. Verlag Styria, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1959, p. 141; for the quote in the original see ʿĀşıḳ-paşa-zāde: Tevārīḫ-i āl-i ʿOs̠mān. Edition ʿAlī Beğ: ʿĀşıḳ-paşa-zāde tārīḫi. Maṭbaʿa-i ʿāmire, Istanbul 1332 (1914), p. 100; Edition Friedrich Giese (Ed.): The old Ottoman chronicle of ʿĀšiḳpašazāde. Released on the basis of several newly discovered manuscripts. Reprint of the 1929 edition. Otto Zeller Verlag, Osnabrück 1972, p. 89.

- ^ JH Kramers: Murād II. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 7, Brill, Leiden / New York 1993, pp. 594 f., Here: p. 595; Halil İnalcık: Murad II. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 31, Istanbul 2006, pp. 164–172, here: p. 170 ( PDF file; 8.2 MB ).

- ↑ So with reference to chalcocondyles also Halil İnalcık: Mehmed II. In: İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 7, Millî Eğitim Basımevi, Istanbul 1957, pp. 506-535, here: p. 509; critical, however, Johann Wilhelm Zinkeisen: History of the Ottoman Empire in Europe. Vol. 1, Perthes, Hamburg 1840, p. 794.

- ↑ Cf. Franz Babinger: Mehmed the Conqueror and his time. World striker at a turning point. F. Bruckmann, Munich 1953, p. 67.

- ↑ Steven Runciman: The conquest of Constantinople 1453. From the English by Peter de Mendelssohn. CH Beck, Munich 1966, pp. 60, 89.

- ↑ ʿĀşıḳ-paşa-zāde: Tevārīḫ-i āl-i ʿOs̠mān (ʿĀşıḳ-paşa-zāde tārīḫi). Edition ʿAlī Beğ. Maṭbaʿa-i ʿāmire, Istanbul 1332 (1914), p. 140.

- ↑ Ṣolaḳ-zāde Meḥmed Hemdemī: Ṣolaḳ-zāde tārīḫi (Tārīḫ-i Ṣolaḳ-zāde). Maḥmūd Beğ maṭbaʿası, Istanbul 1297 (1879/80), p. 187.

- ↑ P. Hardy: ʿĀdil- Sh āhs. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 1, Brill, Leiden 1986, p. 199; Erdoğan Merçil: Âdilşâhîler. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 1, Istanbul 1988, pp. 384–386, here: p. 384 ( PDF file; 2.5 MB ).

- ↑ On the person see M. Çağatay Uluçay: Padişahların Kadınları ve Kızları. 5th edition. Ötüken, Istanbul 2011, ISBN 978-975-437-840-5 , p. 31 f.

- ↑ Instead of many Franz Babinger: Mehmed the Conqueror and his time. World striker at a turning point. F. Bruckmann, Munich 1953, p. 68 f.

- ↑ Based on Dukas also Joseph von Hammer: History of the Ottoman Empire. Vol. 1, Hartleben, Pest 1827, p. 501.

- ↑ İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı: Evrenos. In: İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 4, Millî Eğitim Basımevi, Istanbul 1977, pp. 414-418, here: p. 417.

- ↑ Suicide according to İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı: Osmanlı Tarihi. 10th edition. Vol. 1, Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, Ankara 2011, ISBN 978-975-16-0011-0 , p. 489; Capture and execution after Franz Babinger: Mehmed the Conqueror and his time. World striker at a turning point. F. Bruckmann, Munich 1953, pp. 73 f .; Steven Runciman: The conquest of Constantinople 1453. Translated from the English by Peter de Mendelssohn. CH Beck, Munich 1966, p. 156.

- ↑ Mehmet Akman: Osmanlı Devletinde Kardeş Katli. Eren Yayıncılık, Istanbul 1997, ISBN 975-7622-65-6 , p. 67 ff.

- ↑ See ʿĀşıḳ-paşa-zāde: Tevārīḫ-i āl-i ʿOs̠mān. Edition Friedrich Giese (Ed.): The old Ottoman chronicle of ʿĀšiḳpašazāde. Released on the basis of several newly discovered manuscripts. Reprint of the 1929 edition. Otto Zeller Verlag, Osnabrück 1972, p. 204.

- ↑ Halil İnalcık: Mehmed II. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 28, Ankara 2003, pp. 395–407, here: p. 405 ( PDF file; 11.6 MB ).

- ↑ On Arnavud Sinan Pascha see Hedda Reindl: Men um Bāyezīd. A prosopographical study of the epoch of Sultan Bāyezīds II. (1481–1512) (= Islamic studies. Vol. 75). Klaus Schwarz Verlag, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-922968-22-8 (also dissertation, Ludwig Maximilians University Munich 1982), p. 319 ff.

- ↑ MC Şehabeddin Tekindağ: Bayezid II 'in Tahta Çıkışı Sırasında İstanbul'da Vukua Gelen Hâdiseler Üzerine Notlar. In: İstanbul Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakanschesi Tarih Dergisi. Vol. 10, No. 14, 1959, ISSN 1015-1818 , pp. 85-96, here: p. 89 ( PDF file; 1.2 MB ); Yusuf Küçükdağ: Karamânî Mehmed Paşa. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 24, Istanbul 2001, pp. 449–451, here: p. 450 ( PDF file; 2.6 MB ).

- ↑ MC Şehabeddin Tekindağ: Bayezid II 'in Tahta Çıkışı Sırasında İstanbul'da Vukua Gelen Hâdiseler Üzerine Notlar. In: İstanbul Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakanschesi Tarih Dergisi. Vol. 10, No. 14, 1959, ISSN 1015-1818 , pp. 85-96, here: pp. 89 f. ( PDF file; 1.2 MB ); İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı: II. Bayezid'in Oğullarından Sultan Korkut. In: Belleten. Vol. 30, No. 120, 1966, ISSN 0041-4255 , pp. 539-601, here: p. 542.

- ^ German translations of the execution order by Hans Joachim Kissling: On the personnel policy of Sultan Bājezīd II. In the western border areas of the Ottoman Empire. In: Hans-Georg Beck, Alois Schmaus (Hrsg.): Contributions to research on Southeast Europe. On the occasion of the II. International Balkanologists Congress in Athens 7.V. – 13.V.1970 (= contributions to knowledge of Southeast Europe and the Near East. Vol. 10). Trofenik, Munich 1970, pp. 107–116, here: p. 109 footnote 3; Richard F. Kreutel: The pious Sultan Bayezid. The story of his rule (1481–1512) according to the old Ottoman chronicles of Oruç and Anonymus Hanivaldanus (= Ottoman historians. Vol. 9). Verlag Styria, Graz / Vienna / Cologne 1978, ISBN 3-222-10469-7 , p. 280 f. Note 11.

- ↑ Detailed information on the execution of Gedik Ahmed Pasha İ. H. Uzunçarşılı: Değerli Vezir Gedik Ahmed Paşa II. Bayezid Tarafından Niçin Katledildi? In: Belleten. Vol. 29, No. 115, 1965, ISSN 0041-4255 , pp. 491-497.

- ↑ For the person see Hedda Reindl: Men um Bāyezīd. A prosopographical study of the epoch of Sultan Bāyezīds II. (1481–1512) (= Islamic studies. Vol. 75). Klaus Schwarz Verlag, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-922968-22-8 (also dissertation, Ludwig Maximilians University Munich 1982), p. 244 a. E. ff., In particular p. 246, footnote 26.

- ↑ See also Hedda Reindl: Men around Bāyezīd. A prosopographical study of the epoch of Sultan Bāyezīds II. (1481–1512) (= Islamic studies. Vol. 75). Klaus Schwarz Verlag, Berlin 1983, ISBN 3-922968-22-8 (also dissertation, Ludwig Maximilians University Munich 1982), p. 124 f.

- ↑ For the elegy see Cemâl Kurnaz: Cem Sultan'ın Oğuz Han Mersiyesi: Bir Kaside mi, Üç Gazel mi? In: Türk Dili. Dil ve Edebiyat Dergisi. Vol. 1996 / I, No. 530, February 1996, ISSN 1300-2155 , pp. 315-320 ( PDF file; 123 KB ).

- ↑ Anonymous: Vāḳıʿāt-ı Sulṭān Cem. Edition Meḥmed ʿĀrif: Vāḳıʿāt-ı Sulṭān Cem. In: Taʾrīḫ-i ʿos̠mānī encümeni mecmūʿası. Annexe to Vol. 4, No. 22, 23 and Vol. 5, No. 25, Istanbul 1913/1914, p. 31 f .; Edition Nicolas Vatin: Sultan Djem. Un prince ottoman dans l'Europe du XV e siècle d'après deux sources contemporaines: Vâḳıʿât-ı Sulṭân Cem, œuvres de Guillaume Caoursin. Imprimerie de la Société Turque d'Histoire, Ankara 1997, ISBN 975-16-0832-5 , pp. 238 f., Fol. 31r.

- ↑ So Hans Joachim Kissling: Sultan Bâjezîd's II. Relations with Margrave Francesco II. Von Gonzaga (= Munich University Writings, series of the Philosophical Faculty. Vol. 1). Hueber, Munich 1965, p. 52.

- ↑ Anonymous: Vāḳıʿāt-ı Sulṭān Cem. Edition Meḥmed ʿĀrif: Vāḳıʿāt-ı Sulṭān Cem. In: Taʾrīḫ-i ʿos̠mānī encümeni mecmūʿası. Annexe to Vol. 4, No. 22, 23 and Vol. 5, No. 25, Istanbul 1913/1914, p. 32.

- ↑ Josef Matuz: The Ottoman Empire. Baseline of its history. 6th edition. Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-89678-703-3 , p. 115 f.

- ↑ On the person see Heath W. Lowry: From Trabzon to Istanbul: The Relationship Between Süleyman the Lawgiver & His Foster Brother (Süt Karındaşı) Yahya Efendi. In: Osmanlı Araştırmaları / The Journal of Ottoman Studies. No. 10, 1990, ISSN 0255-0636 , pp. 39-48 ( PDF file; 1.4 MB ); Haşim Şahin: Yahyâ Efendi, Beşiktaşlı. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 43, Istanbul 2013, p. 243 f. ( PDF file; 1.1 MB ).

- ↑ Joseph von Hammer: History of the Ottoman Empire. Vol. 3, Hartleben, Pest 1828, p. 15; İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı: Osmanlı Tarihi. 10th edition. Vol. 2, Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, Ankara 2011, ISBN 978-975-16-0012-7 , p. 401, footnote 1.

- ↑ See Nejat Göyünç: Taʾrīḫ Başlıklı Muhasebe Defterleri. In: Osmanlı Araştırmaları / The Journal of Ottoman Studies. No. 10, 1990, ISSN 0255-0636 , pp. 1–37, here: p. 22 ( PDF file; 5.0 MB ).

- ^ Leslie P. Peirce: The Imperial Harem. Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press, New York a. a. 1993, ISBN 0-19-507673-7 , p. 61.

- ^ Leslie P. Peirce: The Imperial Harem. Women and Sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire. Oxford University Press, New York a. a. 1993, ISBN 0-19-507673-7 , p. 81.

- ↑ On the miniatures Zeynep Tarım Ertuğ: XVI. Yüzyıl Osmanlı Devleti'nde Cülûs ve Cenaze Törenleri (= Osmanlı Eserleri Dizisi. Vol. 16). Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Kültür Bakanlığı Yayınları, Ankara 1999, ISBN 975-17-2151-2 (also dissertation, University of Istanbul 1995), p. 19 ff.

- ^ Çağatay Uluçay: Mustafa Sultan. In: İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 8, Millî Eğitim Basımevi, Istanbul 1979, pp. 690-692, here: p. 691; Mehmet Akman: Osmanlı Devletinde Kardeş Katli. Eren Yayıncılık, Istanbul 1997, ISBN 975-7622-65-6 , p. 87.

- ↑ Instead of many see İbrāhīm Peçevī: Tārīḫ-i Peçevī. Vol. 1, Maṭbaʿa-i ʿāmire, Istanbul 1866, p. 303 aE; for the chronogram see Ahmet Atilla Şentürk: Yahyâ Beğ'in Şehzade Mustafa Mersiyesi yahut Kanunî Hicviyesi. Timaş Yayınları, Istanbul 2009, ISBN 978-975-263-953-9 , p. 181 ff.

- ↑ Mehmed Çavuşoğlu: Sehzade Mustafa Mersiyeleri. In: İstanbul Üniversitesi Edebiyat Fakanschesi Tarih Enstitüsü Dergisi. No. 12, 1982, pp. 641-686, here: pp. 654 ff .; Mustafa İsen: Acıyı Bal Eylemek. Türk Edebiyatında Mersiye. 2nd Edition. Akçağ Yayınevi, Ankara 1994, ISBN 975-338-030-5 , pp. 283-323.

- ↑ For a detailed analysis of the elegy see Ahmet Atilla Şentürk: Yahyâ Beğ'in Şehzade Mustafa Mersiyesi yahut Kanunî Hicviyesi. Timaş Yayınları, Istanbul 2009, ISBN 978-975-263-953-9 , p. 103 ff.

- ↑ Printed in full in Meḥmed Zekī (Pakalın): Maḳtūl şehzādeler. Şems maṭbaʿası, Istanbul 1336 (1920), p. 229 ff .; Ahmet Atilla Şentürk: Yahyâ Beğ'in Şehzade Mustafa Mersiyesi yahut Kanunî Hicviyesi. Timaş Yayınları, Istanbul 2009, ISBN 978-975-263-953-9 , p. 201 ff.

- ^ Translation of the Museum of Islamic Art (ed.): Treasures from the Topkapi Serail. The age of Suleyman the Magnificent. (Catalog for the exhibition of the same name) Dietrich Reimer Verlag, Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-496-01050-9 , p. 42.

- ^ Franz Babinger (ed.): Hans Dernschwam's diary of a trip to Constantinople and Asia Minor (1553/55). According to the original in the Fugger archive. 2nd Edition. Duncker and Humblot, Berlin / Munich 1986, p. 55 f.

- ↑ Feridun Emecen: Süleyman I. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 38, Istanbul 2010, pp. 62–74, here: p. 69 ( PDF file; 12.2 MB ).

- ↑ Joseph von Hammer: History of the Ottoman Empire. Vol. 3, Hartleben, Pest 1828, p. 319; John Freely: Inside the Seraglio. Private Lives of the Sultans in Istanbul. Viking, London 1999, ISBN 0-670-87839-1 , p. 62; İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı: Osmanlı Tarihi. 10th edition. Vol. 2, Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, Ankara 2011, ISBN 978-975-16-0012-7 , p. 404; Serafettin Turan: Kanuni Sultan Suleyman Dönemi Taht Kavgaları. 3. Edition. Kapı Yayınları, Istanbul 2011, ISBN 978-605-4322-71-8 , p. 54; M. Tayyib Gökbilgin: Hurrem Sultan. In: İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 5, part 1, Millî Eğitim Basımevi, Istanbul 1987, pp. 593-596, here: p. 595; Cahit Baltacı: Hürrem Sultan. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 18, Istanbul 1998, pp. 498–500, here: p. 499 ( PDF file; 2.6 MB ).

- ↑ Pleurisy according to SA Skilliter: Kh urrem. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 5, Brill, Leiden 1986, p. 66 f., Here: p. 67; Suicide according to Museum of Islamic Art (Ed.): Treasures from the Topkapi Seraglio. The age of Suleyman the Magnificent. (Catalog for the exhibition of the same name) Dietrich Reimer Verlag, Berlin 1988, ISBN 3-496-01050-9 , p. 41 with additional information

- ↑ İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı: Osmanlı Tarihi. 10th edition. Vol. 2, Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, Ankara 2011, ISBN 978-975-16-0012-7 , p. 404.

- ^ Çağatay Uluçay: Mustafa Sultan. In: İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 8, Millî Eğitim Basımevi, Istanbul 1979, pp. 690-692, here: p. 691; Şerafettin Turan: Mustafa Çelebi. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 31, Istanbul 2006, pp. 290–292, here: p. 291 ( PDF file; 2.7 MB ); Ahmet Atilla Şentürk: Yahyâ Beğ'in Şehzade Mustafa Mersiyesi yahut Kanunî Hicviyesi. Timaş Yayınları, Istanbul 2009, ISBN 978-975-263-953-9 , p. 73; Stéphane Yerasimos: Constantinople. Istanbul's historical heritage. From the French by Ursula Arnsperger u. a. Ullmann, Potsdam 2009, ISBN 978-3-8331-5585-7 , p. 179.

- ↑ AH de Groot: Murād III. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 7, Brill, Leiden / New York 1993, pp. 595-597, here: p. 596; Bekir Kütükoğlu: Murad III. In: İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 8, Millî Eğitim Basımevi, Istanbul 1979, pp. 615-625, here: p. 615; Bekir Kütükoğlu: Murad III. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 31, Istanbul 2006, pp. 172–176, here: p. 172 ( PDF file; 4.5 MB ); İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı: Osmanlı Tarihi. 8th edition. Vol. 3, Part 1, Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, Ankara 2011, ISBN 978-975-16-0013-4 , p. 42; Mehmet Akman: Osmanlı Devletinde Kardeş Katli. Eren Yayıncılık, Istanbul 1997, ISBN 975-7622-65-6 , p. 98 f.

- ↑ Zeynep Hatice Kurtbil: Selim II Türbesi. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 36, Istanbul 2009, pp. 418–420, here: p. 419 ( PDF file; 2.7 MB ).

- ↑ Joseph von Hammer: History of the Ottoman Empire. Vol. 4, Hartleben, Pest 1829, p. 241; Friedrich Giese: The seniorate in the Ottoman ruling house. In: Friedrich Kraelitz-Greifenhorst, Paul Wittek (Hrsg.): Communications on Ottoman history. Reprint of the edition from 1923–1926. Vol. 2, Biblio, Osnabrück 1972, ISBN 3-7648-0510-2 , pp. 248-256, here: p. 253.

- ↑ SA Skilliter: Meḥemmed III. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 6, Brill, Leiden 1991, pp. 981 f .; M. Tayyib Gökbilgin: Mehmed III. In: İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 7, Millî Eğitim Basımevi, Istanbul 1957 pp. 535-547, here: p. 536; Feridun Emecen: Mehmed III. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 28, Ankara 2003, pp. 407-413 ( PDF file; 6.3 MB ); for the names of the strangled princes see Ṣolaḳ-zāde Meḥmed Hemdemī: Ṣolaḳ-zāde tārīḫi (Tārīḫ-i Ṣolaḳ-zāde). Maḥmūd Beğ maṭbaʿası, Istanbul 1297 (1879/80), p. 62.

- ↑ İsmail Orman: Murad III Türbesi. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 31, Istanbul 2006, p. 176 f. ( PDF file; 1.7 MB ); to the number of Murads III in the Türbe. buried persons see Ḥüseyin Ayvānsarāyī: Ḥadīḳatü l-cevāmiʿ. Modifications made by ʿAlī Sāṭıʿ Efendi. Vol. 1, Maṭbaʿa-i ʿāmire, Istanbul 1281 (1864), p. 6.

- ↑ İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı: Osmanlı Tarihi. 8th edition. Vol. 3, part 1, Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, Ankara 2011, ISBN 978-975-16-0013-4 , p. 115.

- ↑ See İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı: Osmanlı Devletinin Saray Teşkilâtı. 3. Edition. Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, Ankara 1988, ISBN 975-16-0041-3 , p. 46 f.

- ↑ Şinâsî Altundağ: Osman II. In: İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 9, Millî Eğitim Basımevi, Istanbul 1964, pp. 443-448, here: p. 445; İsmail Hakkı Uzunçarşılı: Osmanlı Tarihi. 8th edition. Vol. 3, part 1, Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi, Ankara 2011, ISBN 978-975-16-0013-4 , pp. 129 f .; Mehmet Akman: Osmanlı Devletinde Kardeş Katli. Eren Yayıncılık, Istanbul 1997, ISBN 975-7622-65-6 , pp. 105 f .; Feridun Emecen: Osman II. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 33, Istanbul 2007, pp. 453–456, here: p. 454 ( PDF file; 3.6 MB ).

- ^ Klaus Kreiser: History of Istanbul. From antiquity to the present. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-58781-8 , p. 85.

- ↑ See Kemal Beydilli: Selim III. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 36, Istanbul 2009, pp. 420–425, here: p. 424 ( PDF file; 5.5 MB ).

- ↑ Erhan Afyoncu, Ahmet Önal, Uğur Demir: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nda Askeri İsyanlar ve Darbeler. Yeditepe Yayınevi, Istanbul 2010, ISBN 978-605-4052-20-2 , p. 236 ff .; M. Şükrü Hanioğlu: A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-691-13452-9 , p. 56; Virginia H. Aksan: Ottoman Wars 1700-1870. To Empire Besieged. Pearson Education Limited, London 2007, ISBN 978-0-582-30807-7 , p. 249.

- ↑ Josef Matuz: The Ottoman Empire. Baseline of its history. 6th edition. Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-89678-703-3 , p. 215 f.

- ^ JH Kramers: Muṣṭafā IV. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Vol. 7, Brill, Leiden / New York 1993, pp. 709 f., Here: p. 710; Kemal Beydilli: Mustafa IV. In: Türkiye Diyanet Vakfı İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Vol. 31, Istanbul 2006, pp. 283–285 ( PDF file; 2.5 MB ).