Edward Gorey

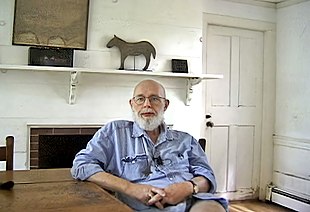

Edward St. John Gorey (born February 22, 1925 in Chicago , Illinois , † April 15, 2000 in Hyannis , Massachusetts ) was an American author and illustrator . He is known for his black and white hatched drawings with which he illustrated books by other authors as well as his own works, mainly short stories in comic form.

Gorey's own stories are kept in bizarre humor and relate to nonsense and children's literature. They often deal with expressionless people in the late 19th or early 20th century to whom absurd and macabre things happened. The sober tone of the text is characteristic of Gorey's works, which, together with the drawings, often gives a motionless, sinister impression. His best-known works include The Doubtful Guest (1957) and The Gashlycrumb Tinies (1963).

Life

Edward Gorey was the only child of newspaper reporter Edward Leo Gorey and his wife Helen, nee. Garvey. The parents encouraged young Gorey's drawing talent. Nevertheless, he learned to draw largely in self-study; After graduating from high school , he only attended a Saturday course at the Art Institute of Chicago for one semester in 1943 . From 1944 to 1946, Gorey served in the Army as an employee at the Dugway Proving Ground weapons test site in Utah . He then enrolled at Harvard University , where he graduated in 1950 with a Bachelor of Arts in French.

After working for various booksellers in Boston , Gorey worked in New York from 1953 to 1960 as an author and illustrator for the Doubleday publishing house . In 1953 he published his first book, The Unstrung Harp , followed a year later by The Listing Attic. These unusual works found favor with a curious group of readers and New York intellectuals. With the publication of The Doubtful Guest by Doubleday three years later, his works became known to children and adults outside of New York. Gorey's first four books sold only about 1,500 copies each, and he often changed publishers. Sometimes he published the books himself under the Fantod Press imprint .

Gorey's works gained more attention after Edmund Wilson compared Gorey's drawings with those of Max Beerbohm and Aubrey Beardsley for The New Yorker magazine in 1959 . In 1959 Gorey founded the Looking Glass Library, an imprint of the Random House publishing house specializing in children's books .

In the 1960s, Gorey began to publish some of his pre-book stories in magazines, such as Leaves From A Mislaid Album in First Person (1960) or The Willowdale Handcar and The Evil Garden in Holiday Magazine (1962 and 1965, respectively). From 1965 his works were exhibited regularly by art colleges and institutions.

In the 1970s, Gorey focused on adult stories but continued to make a living mainly illustrating other authors' books. The Diogenes Verlag began in 1972 in order to publish some of his early works in German translation; the illustrations on numerous book covers of the publisher are taken from his works. Gorey increasingly experimented with unusual book formats and new ways of combining text and drawing, for example he wrote the pop-up book The Dwindling Party in 1982 .

Gorey owned several cats, was interested in silent films, Victorian novels, and Japanese and Chinese literature, and regularly saw George Balanchine's performances at the New York City Ballet ; all of these interests were also a source of inspiration for his works. Gorey frequently visited Cape Cod , which was also home to family members and friends. He lived temporarily in Barnstable during the summer months before moving from Manhattan to Yarmouth Port near Barnstable in 1988 . Since then he has mainly been involved in theater productions, both as a stage and costume designer and as the author of several plays. Gorey died of a heart attack on April 15, 2000, unmarried and childless in Cape Cod Hospital in Hyannis. His home, called the Elephant House , is now a museum, in which his life and work are documented.

Books

With a few exceptions, Gorey's more than 100 books are short stories in the form of a sequence of images, each with short texts as prose or poem . The stories seem to take place in the late Victorian or Edwardian ages , often in affluent settings with stately mansions and formally dressed, expressionless people from the upper class. The motionless, mostly gloomy black-and-white atmosphere of the drawings, the scenes from a bygone era and the short, cool-toned text create the impression that a “parallel universe” that obeys its own rules and properties is being entered. Edmund Wilson described Gorey's works as "amusing and gloomy, wistful and claustrophobic, poetic and poisoned at the same time."

Something unforeseen always happens in Gorey's stories: people are haunted by strange characters, disappear or suddenly suffer abstruse misfortunes. Children are particularly often victims; One of Gorey's most famous books, The Gashlycrumb Tinies, enumerates the fatal fates of 26 young children in alphabetical order in naive pair rhyme . Still, the overall impression of Gorey's stories is not tragic, but rather comical because of the ironic undertone. The works were also referred to as " postmodern fairy tales"; some can be considered children's literature, albeit unconventional by today's standards. The relation to nonsense is more or less pronounced.

References to children's literature

Regarding the question of whether Gorey's works can be considered children's or adult literature, there are different assessments of the often macabre content. Obituaries and criticisms range from claiming that Gorey is not an author of children's books to claiming that his books are ideal for children. Gorey, who illustrated children's literature all his life and taught a course on children's literature at the university in 1965, made contradicting statements about the target audience of his works. He once claimed that he had written many of his own works primarily for children; another time he was amazed that children would like his books since he only had adults in mind.

Kevin Shortsleeve sees the reason for Gorey's lack of reputation as a children's author both in his unwillingness to promote his works and in the way his works have been published. The publishers of the Amphigorey collections did not see children as a target group, so the books would mix stories suitable for children with stories that could be considered unsuitable. Gorey did not consider his stories inappropriate, as he understood that earlier children's literature was often cruel, such as some of Grimm's fairy tales . Indeed, children - who would appreciate violent literature anyway - might perceive Gorey's works as parodies of the numerous children's stories that end well and demonstrate their maturity by reading Gorey. Some of the fates of children, as described by Gorey, are also plausible; Children could feel addressed by these refreshingly brutal, realistic descriptions.

Some of Gorey's stories are similar to children's books with warning and chilling examples, such as those published by Wilhelm Busch , Heinrich Hoffmann ( Struwwelpeter ) and Hilaire Belloc (Cautionary Tales for Children) . The book The Stupid Joke, for example, tells the story of a boy who, to the chagrin of his family, makes fun of staying in bed all day, and who ends up badly. The terrible consequences of childlike disobedience always give Gorey a normal and less tragic impression.

Humor and parody

Although Gorey can be described as a humorist rather than a satirist in the absence of any moral opinion in his works, he made use of satirical stylistic devices such as irony and parody. In The Unknown Vegetable , complete moral emptiness itself becomes the subject of irony. The story in which a young woman digs a hole next to a plant for no apparent reason and is buried in it ends with the words “There is a moral to this fable / Of an unknown vegetable”.

According to Steven Heller, Gorey's characters parody the manners of the Victorian era, "that obsessively moral time - and in a broader sense the absurdities of the present." The humor in Gorey's work can also be viewed as a modern form of black humor , based on an ironic reversal of the cult of sentimentality prevalent in the Victorian era. Since in the 19th century deaths could not so easily be left to hospitals and nursing homes, but had to deal with them in one's own home, death was idealized in a sentimental and pious way. Gorey satirized and parodied this attitude particularly obviously in The Gashlycrumb Tinies as well as in the story The Pious Infant, kept in the style of puritanical- moralistic children's literature . The comedy of childish misfortunes is also based on the ironic processing of the motif of parental care. In The Gashlycrumb Tinies the parents seem to be present and absent at the same time, as the children are on the one hand well cared for, and on the other hand the misfortunes are apparently due to a lack of care. This contrast is emphasized by the smart clothes of the children and the luxurious interiors in which they come to an end.

Wim Tigges sees a “perfect balance between the existence and non-existence of humor” in Gorey's works, because sentences like “In the next two years they killed three more children, but it was never as amusing as the first time” (from The Loathsome Couple ) create an inner contrast that makes you waver between amusement and revulsion. Gorey's works are not only about macabre incidents, but often only bizarre annoyances. When asked if he was concerned about the impact of his stories on readers, Gorey replied that he hoped his works were "slightly unsettling," as it were.

Nonsense and puns

About half of Gorey's works consist of rhymes or short, alliterative sentences. Nonsense is a common feature of Gorey's stories; the word amphigory , on which the titles of Gorey's anthologies are based, means ' nonsense poem '. The speech melody of the verses, the playful rhymes and the nonsense limericks are similar to the works of Edward Lear , but are "blacker". Occasionally they seem to combine joie de vivre and death, for example in the last verse from The Wuggly Ump, in which a monster eats three children: "Sing glogalimp, sing glugalump, From deep inside the Wuggly Ump". A certain influence of the comical nonsense ideas of William Heath Robinson , for example in his told / drawn story Uncle Lubin, is recognizable.

The "comical morbidity" of Gorey's stories has been compared to Charles Addams ' cartoons . Gorey's “dark” nonsense and cruel humor also make the biggest difference to the nonsense children's literature by Dr. Seuss , in which happiness and optimism predominate. However, both the nonsense texts and the rhyming pairs build a distance to the violent content. Gorey himself saw no alternative to "hideous" nonsense, because "sunny, happy" nonsense is boring. Gorey's dry descriptions of improbable sequences of events also show parallels to Dadaist and surrealist poems. Gorey saw himself in the tradition of surrealist theory, but was averse to most works of art of surrealism.

A frequent element in Gorey's works is the dry mention of decorative but somewhat out of place details. In Gorey's first work The Unstrung Harp, in which the writer Mr. Earbrass is writing his new book, the following examples can be found:

|

|

|

|

|

According to Gorey, he tried to express irrelevant and inappropriate ideas so as not to restrict the reader's imagination by means of specific contexts of meaning. The book L'heure bleue, a series of meaningless and partly syntactically absurd dialogues between two dogs, is reminiscent of Gertrude Stein's experimental collection of texts Tender Buttons. According to Van Leeuwen, Gorey's work cannot be described as “pure” nonsense, since it “does not represent the comedy of paradoxical trains of thought, but the nothingness of paradoxical emotions”.

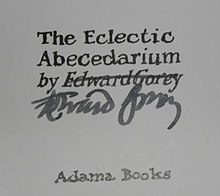

Gorey often wrote under pseudonyms, often anagrams of his own name. Occasionally he borrowed titles, subtitles or personal names from the French, German and Italian languages. Several works are in alphabetical form and seem to parody early ABC books with their superficially moral sounding but insignificant texts , such as The Chinese Obelisks (1972), The Glorious Nosebleed (1974) or The Eclectic Abecedarium (1983).

Stories like The Raging Tide , in which the reader can set up a plot sequence for themselves, and books in unusual formats - without text, thumb-sized or as a folded book - are close to postmodern literature , which expressly indicates its form through self-referentiality .

Drawing style and symbolism

In Gorey's work there is a balance between words and images that are inextricably linked.

Steven Heller described Gorey's portrayal of bygone times as follows: "His meticulous lines, paired with a keen sense of British expression, create a graphic set of Victorian rooms with upholstered furniture, omnipresent urns and gloomy curtains." An article in Die Zeit expresses itself similarly : Gorey's toddler figures “act together with men with gloomy foreheads, in ankle-length coats and striped scarves, together with veiled women in crackling black taffeta dresses, together with devious-looking domestics and viciously curling small animals, in a world that has many Victorian attributes, but but was created by Gorey. Heavy velvet porters, deep armchairs, flowered wallpaper and carpets, paneled walls are the constant props, gloomy mansions and endless, defoliated parks are the preferred settings. "

Gorey admired John Tenniel's illustrations and, according to a biography of Edward Lear, was influenced by his drawing style. Some of Gorey's books, especially later ones, are washed with watercolors . He used colors as an additional element in order to better emphasize or differentiate individual elements, but not to directly reinforce the emotional effect. The drawings are often designed sparingly, as they only show a few people against a background that has been reduced to the essentials. The context is often clarified by object fragments at the edge of the picture, such as parts of a track or a statue. Gorey often portrayed the most dramatic moment, shortly before the immediate consequences of the accident. Gorey considered newspaper photos, especially from the sports section, to be a good starting point for his works, as they often show unexpected combinations of moving figures.

Gorey's books and stories are vaguely reminiscent of silent films. The "travel story " The Willowdale Handcar, for example, has the effect of a pastiche on the short films by Buster Keaton because of the demonstrative seriousness of the text and the absurd plot . Gorey himself wrote an unfilmed screenplay for a silent film thriller parody called The Black Doll. Despite Gorey's interest in the art of film, his drawings do not imitate the camera perspective typical of films. Rather, he depicts his characters as a whole and at the same distance from the viewer, comparable to stage actors.

In The Gashlycrumb Tinies , the irony is also graphically expressed in the cover picture, which shows death personified holding an umbrella protectively over the immobile group of children. Gorey often used symbols such as bats, urns, or skulls, which serve as harbingers of evil. Such omen were common in both horror novels and nineteenth-century painting; in the novel Dracula, for example, the vampire flies around the windows of its victims in the form of a bat. This symbolism becomes particularly evident in Gorey's The Hapless Child , as the images in the background show strange creatures that foreshadow the unfortunate outcome of the story. Nevertheless, Gorey did not see himself in the tradition of the horror novel. According to Hendrik van Leeuwen, Gorey graphically represented the “oppressive emptiness” that is only expressed in text form in Samuel Beckett's works. The comparison with Beckett in Gorey's textless picture book The West Wing, which shows a series of gloomy, empty rooms with isolated figures and objects, becomes particularly clear .

Gorey repeatedly made use of banal everyday objects such as umbrellas, bicycles, bookbinder's paste, tea warmers or feather dusters, which he often integrated into the action as puzzling elements and which occasionally even become active main characters in the plot ( e.g. in The Inanimate Tragedy ). In contrast to Max Ernst's illustrated nonsense novels such as Une semaine de bonté , sexual symbolism plays no role in Gorey, with the exception of The Curious Sofa and The Recently Deflowered Girl (published under the pseudonym "Hyacinthe Phypps"). In an interview, Gorey attributed the asexuality of his stories to the fact that he himself had a "rather underdeveloped sex drive" compared to some other people.

List of well-known works

The Unstrung Harp ( A harp without strings, 1953)

- This first published book by Goreys tells in 30 pictures of a novelist who is writing his new book. The gradual accumulation of nonsensical and bizarre details in the text creates a tension between the meaningfulness of what is described and nonsense right from the start; in the end, the story raised more questions than it answered. The work can be interpreted both as a self-portrait of Goreys and as a satire on the question of the meaning of book-writing.

The Listing Attic ( Balaclava, 1954)

- This book contains 60 illustrated limericks . According to Wim Tigges' count, 24 of the poems describe various acts of violence in a dry manner; this is typical of many works of nonsense literature. The cruelty remains unmotivated and unexplained without addressing the reader's sympathy. The exuberance of Edward Lear's characters often gives way to bored indolence in Gorey. Gorey's texts are also more precise than Lear's, a murder, for example, is described in a similarly sober tone as a police report.

The Doubtful Guest ( The dubious Guest, 1957)

- The Doubtful Guest is about a family who is haunted by an intruder, a mute, penguin-like figure. Although the "guest" is a nuisance to the residents, his presence is tolerated. Gorey dedicated the work to Alison Lurie after learning of her pregnancy. Lurie suspects that the dubious guest, who at first looks strange and doesn't understand a language, and later displays greedy and destructive behavior, is supposed to be a child.

The Object-Lesson ( A Sure Evidence, 1958)

- This book consists of 30 drawings, each with one line of text, which together form a “ non sequitur ”, a story with no context. The text is reminiscent of the literary avant-garde techniques of William S. Burroughs and Brion Gysin , who fabricated nonsense by cutting out sentences from newspapers and putting them back together in any order. Although the text is on the verge of the absurd, a meaningful plot is suggested along with the images. It seems like the puzzle could be solved with just some additional clue.

The Fatal Lozenge ( The Morita Alphabet, 1960)

- Similar to The Listing Attic , this four - line cross rhyming alphabet ironically processes brutality. Gorey's pictures are similar in style and rawness to the Victorian tabloid The Illustrated Police News , but the text remains cool and avoids the sensational language of the newspaper, which morally condemns the acts. Gorey does not identify victims or perpetrators, nor does he provide any information about whether the actions should be classified as a crime at all.

The Hapless Child ( The unfortunate child, 1961)

- This story tells in a laconic tone of a little girl from a well-to-do family who loses both parents, is put in boarding school, after escaping falls under the control of a drunkard and is finally run over by her father, who was believed dead. While the book can be viewed as a parody of the sappy nineteenth-century children's novel, that doesn't prevent the reader from following the plot with genuine pity. The story has been compared to Frances Hodgson Burnett's Sara Crewe , but it is actually based on Léonce Perret's silent film L'enfant de Paris (1913). However, Gorey replaced the kidnapping story of the film with a tragic storyline that dashed hopes for a happy ending.

The Curious Sofa ( The Secret of the Ottoman, 1961)

- Despite the subtitle of this work, "a pornographic work by Ogdred Weary", all actions are left to the reader's imagination. The suggestive and yet meaningless expressions such as “to render a highly surprising service” are reflected in the drawings by blank, concealing wall screens , car doors or branches, so that almost doubts arise as to whether something offensive is being described at all. The work can be seen as a satire on erotic fantasy and pornography consumption; the punch line is that nothing happens. Gorey himself referred to the book, which he drew on a weekend, as a satire on Dominique Aurys Story of O . The Curious Sofa is the only complete work by Gorey that was also published in the GDR . The work was indexed in Austria .

The Gashlycrumb Tinies ( The Little Morks, 1963)

- This work is one of several rhyming alphabets. In each of the pictures, a small child whose old-fashioned name begins with the respective letter falls victim to a violent death. With a few exceptions, the children are depicted alone in empty rooms or lonely surroundings. The undignified, grotesque forms of death stand in blatant contrast to the Victorian ideal of the "good" death. The humor of the work is largely determined by the fact that one death follows another apparently casually, right down to the letter Z. In contrast to The Hapless Child , the reader is more inclined to amuse themselves at the inventive rhyming pairs than to regret the fatal ones To show the fates of the children. Together with The Doubtful Guest counts The Gashlycrumb Tinies of the most famous works Gorey.

The Wuggly Ump ( The Schrekelhuck, 1963)

- The Wuggly Ump is Gorey's only work that has been advertised as a children's book by publishers and is also one of the few books with colored drawings. The story is about three children playing who are devoured by a voracious monster at the end. In contrast to Edward Lear's monsters, who perform nonsensical actions as protagonists , the nonsense of the "Wuggly Ump" consists in the fact that he is described as an intruder, whose origin and intentions are unclear. This impression is reinforced by the fact that the victims happily ignore the impending danger until the end.

The Sinking Spell ( The Haunting Case, 1964)

- This story is about an enigmatic something that slowly sinks down from the sky, floats on through a family's house and finally sinks into the basement. There is never a hint of what the "creature" is, and it does not seem to cause any reaction other than amazement in those affected. The "spook" itself remains invisible in the 16 pictures; its existence is only hinted at by the staring looks of the people portrayed.

The Evil Garden ( The Evil Garden, 1966)

- Like many other works, Gorey published this book under a pseudonym; According to the title page, it is Mrs. Regera Dowdy's translation of a story by Eduard Blutig with drawings by O. Müde. A family enters a strange garden that looks magnificent at first glance, but soon turns out to be fatal. Little by little, people are devoured by plants, strangled by snakes or sink into the "bubbling pond".

The Iron Tonic ( The Iron Tonic, 1969)

- In contrast to the other stories, this compilation of illustrated rhyming pairs (subtitle: "or, a Winter Afternoon in Lonely Valley") is set in a vast, lonely, barren winter landscape. In some of the pictures, objects such as clocks, mirrors, vases and bicycles fall from the sky, which are popular nonsense objects. Each drawing contains a circular view that at first glance looks like a magnifying glass placed over the scene, but often shows details that are distant, detached from the context and hardly contributes to understanding.

The Epiplectic Bicycle ( The epiplektische bike, 1969)

- The Epiplectic Bicycle is one of the works with pronounced nonsense elements. The book is about two children, Embley and Yewbert, who find a bike and go on a journey of strange adventures with it.

The Loathsome Couple ( The despicable pair, 1977)

- This story tells of a criminal couple and their "life's work" which consists of luring young children into a remote house and spending nights murdering them "in various ways". The couple are eventually suspected and arrested. Gorey admitted that The Loathsome Couple was a disturbing work, but defended himself by saying that it was based on a real case, namely the Moors murders .

Cover design and illustration

Gorey began his work as a book cover designer in 1953 for Anchor Books, an imprint of Doubleday Publishing specializing in high-quality paperback books. Many of the books published by Anchor were on factual subjects and had colleges as their main target group; the titles range from Virgil's Aeneid to Henry Kissinger's Nuclear Weapons and Foreign Policy. As chief designer of the book covers, Gorey oversaw all of the design, including typography and layout, and ensured a consistent appearance. Other artists often worked on the illustrations, including Leonard Baskin , Milton Glaser , Philippe Julian and Andy Warhol . Of the two hundred titles published during Gorey's time with Anchor, about a quarter of the titles were hand-illustrated by Gorey. Gorey also designed covers with a comparable appearance for other publishers.

Compared to the paperback bindings customary at the time, Anchor's book bindings were described as “modern” and “artistically presented”; Print magazine gave them a uniform, independent impression. Gorey's illustrations for the book covers are in the same old-fashioned black and white hatched style as his own books. Very often Gorey put the contrast between an "innocent" character, who often stands out from a group, and a "dark" character. Instead of a somber figure, Gorey occasionally depicted an eerie object, for example a sinister mansion ( Alain-Fournier's The Wanderer ) or a dark statue ( Joseph Conrad's The Secret Agent ). As in his own books, Gorey used color sparingly as a design aid. In most illustrations, the background is at most two-tone, and individual objects may also be highlighted in monochrome.

Gorey not only designed book covers on non-fiction and fiction, but also illustrated entire books by other authors, including works as diverse as HG Wells ' War of the Worlds and TS Eliot's satirical collection of poems, Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats . He also occasionally provided illustrations for magazines such as National Lampoon , Vogue and Harper's Magazine . From 1980 Gorey designed the animated opening sequences for the series Mystery! Together with the animated film maker Derek Lamb . of the PBS television network , which brought his style to a wider American audience. Occasionally, Gorey also designed posters as well as record and CD covers.

Theater productions

From 1973 Gorey designed costumes and decorations for mostly regional theater performances and ballets. He won the Tony Award the following year for his costume designs for the Broadway production of Hamilton Deane's Dracula adaptation under the direction of Dennis Rosa in 1977 . His stage design, which with the exception of one bright red object per scene was black and white, received a nomination. The play was a hit with the public, but received mixed reactions from critics. The New York Magazine about complained that an already shoddy old piece was staged yet campy exaggeration. Gorey's drawings are complex, but inadequate and inflated as a stage design. Production ended in 1980 after over 900 performances.

Goreys wrote a number of plays himself, such as the university play Tinned Lettuce (1985). The off-Broadway production Amphigorey: The Musical (1992), in which he translated his stories for the stage, only saw one performance. There is also a musical adaptation by students of the University of Kentucky entitled Gorey Stories, which was also performed off-Broadway in 1978 and once on Broadway. On Cape Cod, Gorey wrote and directed several local theater productions, including some hand puppet shows. The following are the titles of Gorey's theatrical productions on Cape Cod and when they were performed. Unless otherwise noted, Gorey directed it himself.

Lost Shoelaces Aug 1987 Heads Will Roll (puppet show) July 1996 Useful Urns June-Aug. 1990 Heads Will Roll / Wallpaper Aug. – Sep. 1996 Stuffed Elephants Aug-Sep. 1990 Cautionary Tales (Hilaire Belloc; puppet show) Oct. – Nov. 1996 Flapping ankles July-Aug. 1991 Epistolary Play July-Aug. 1997 Crazed teacups July-Aug. 1992 Omlet: or, Poopies Dallying / Rune lousse, rune de leglets: ou, sirence de glenouirres (puppet show) July-Aug. 1998 Blithering Christmas Dec 1992 English soup Oct 1998 Chinese gossip July-Aug. 1994 Moderate seaweed Aug 1999 Salome ( Oscar Wilde ) Feb 1995 Papa Was a Rolling Stone: a Christmas Story

(co-author: Carol Verburg, director: Joe Richards)Dec 1999 Inverted commas July 1995 The White Canoe: an Opera Seria for Hand Puppets

(puppet show; music: Daniel Wolf, director: Carol Verburg)Sep 2000 Stumbling Christmas Nov. – Dec. 1995

influence

Some of Gorey's stories were written by jazz musicians Michael Mantler ( The Hapless Child, 1976) and Max Nagl ( The Evil Garden, 2001), the British music group The Tiger Lillies with the Kronos Quartet ( The Gorey End, 2003), and by the composer Stephan Winkler ( The Doubtful Guest, 2006/2007) set to music.

The novelist and screenwriter Lemony Snicket (Daniel Handler) came into contact with Gorey's works early on and, according to his own admission, was influenced by them; Parallels to Gorey can be seen particularly in Handler's early books for children and young people. Gorey was also cited as a source of inspiration for Tim Burton's illustrated poetry collection, The Melancholy Death of Oyster Boy (1997). In the film The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993) produced by Burton, the scenes were deliberately designed "Gorey-style" , according to director Henry Selick . According to Mark Dery, Gorey's works influenced Rob Reger's comic book character Emily the Strange and Neil Gaiman's novel Coraline ; the latter was originally intended to be illustrated by Gorey.

The music video directed by Mark Romanek for the song The Perfect Drug of the music project Nine Inch Nails uses several visual elements from Gorey's books, including black-veiled women, oversized urns, obelisks and topiary plants .

Awards

- New York Times "Best Illustrated Book of the Year" 1969 for illustrations by Edward Lears Dong with the Luminous Nose and 1971 for illustrations by Florence Parry Heides The Shrinking of Treehorn.

- Recording Amphigorey in the list of 50 best-designed books of the year in 1972 by the American Institute of Graphic Arts .

- Choice of Amphigorey one of the five "remarkable art books" of 1972 by the New York Times.

- “Best Children's Book” at the Children's Book Fair Bologna 1977 for The Shrinking of Treehorn.

- German Youth Literature Prize 1977 for Schorschi schrumpft (German translation of The Shrinking of Treehorn ).

- Tony Award 1978 for the costume designs for the Broadway production of Dracula.

- World Fantasy Award 1985 and 1989 (artist category).

- Bram Stoker Award 1999 (Lifetime Achievement Category).

Exhibitions

- Seven fantastic humorists: Paul Flora , Edward Gorey, Luis Murschetz , JJ Sempé , Roland Topor , Tomi Ungerer , Reiner Zimnik , exhibition catalog: October 5 - November 18, 1972. Daniel Keel Gallery , Zurich 1972, OCLC 758385075 .

- Gorey's Worlds , Wadsworth Atheneum , Hartford, Connecticut, USA 2018. Catalog.

literature

Anthologies

The publication dates given refer to the latest paperback edition.

- Edward Gorey: Amphigorey. Perigee, New York 1980, ISBN 0-399-50433-8 ( hardcover - first edition published in 1972)

- Contains The Unstrung Harp, The Listing Attic, The Doubtful Guest, The Object-Lesson, The Bug Book, The Fatal Lozenge, The Hapless Child, The Curious Sofa, The Willowdale Handcar, The Gashlycrumb Tinies, The Insect God, The West Wing, The Wuggly Ump, The Sinking Spell and The Remembered Visit

- Edward Gorey: Amphigorey Too. Perigee, New York 1980, ISBN 0-399-50420-6 (hardcover first edition published in 1975)

- Contains The Beastly Baby, The Nursery Frieze, The Pious Infant, The Evil Garden, The Inanimate Tragedy, The Gilded Bat, The Iron Tonic, The Osbick Bird, The Chinese Obelisks (final draft and draft), The Deranged Cousins, The Eleventh Episode, [The Untitled Book], The Lavender Leotard, The Disrespectful Summons, The Abandoned Sock, The Lost Lions, Story for Sara (after Alphonse Allais ), The Salt Herring (after Charles Cros ), Leaves from a Mislaid Album and A Limerick

- Edward Gorey: Amphigorey So. Harcourt, London 1998, ISBN 0-15-605672-0 (hardcover first edition published in 1983)

- Contains The Utter Zoo, The Blue Aspic, The Epiplectic Bicycle, The Sopping Thursday, The Grand Passion, Les passementeries horribles, The Eclectic Abecedarium, L'heure bleue, The Broken Spoke, The Awdrey-Gore Legacy, The Glorious Nosebleed, The Loathsome Couple, The Green Beads, Les urnes utiles, The Stupid Joke, The Prune People and The Tuning Fork

- Edward Gorey: Amphigorey Again. Harcourt, Orlando 2007, ISBN 0-15-603021-7 (hardcover first edition published in 2006)

- Contains The Galoshes of Remorse, Signs of Spring, Seasonal Confusion, Random Walk, Category, The Other Statue, 10 Impossible Objects (abridged version), The Universal Solvent (abridged version), Scènes de ballet, Verse Advice, The Deadly Blotter, Creativity , The Retrieved Locket, The Water Flowers, The Haunted Tea-Cozy, Christmas Wrap-Up, The Headless Bust, The Just Dessert, The Admonitory Hippopotamus, Neglected Murderesses, Tragédies topiares, The Raging Tide, The Unknown Vegetable, Another Random Walk, Serious Life: A Cruise, Figbash Acrobate, La malle saignante and The Izzard Book (unfinished)

German language translations

The following 33 works by Edward Gorey were published as Diogenes Kunst Taschenbuch 26033-26065. Translations by Wolfgang Hildesheimer , Hans Manz , Dieter E. Zimmer , Walter E. Richartz , Jörg Drews , Werner Mintosch , Hans Wollschläger , Gerd Haffmans , Urs Widmer , Fritz Senn and Ursula Fuchs .

- A Harp Without Strings or How to Write Novels, Balaclava, The Doubtful Guest / A Sure Evidence, The Beetle Book / The Schrekelhuck, The Moritas Alphabet / The Spook Case, The Secret of the Ottoman, The Unfortunate Child, The Ugly Baby, That pious child Heini Klump, The Draisine von Untermattenwaag (1963 and 1981; The Willowdale Handcar), The Little Morks Blanks, The West Wing, The Insect God, Memory of a Visit, The Soulless Tragedy / The Horrible Passamentaries, The Evil Garden, La chauve- souris dorée, The Alphabetical Zoo / The Nursery Frieze, The Sad Twelve Pounder or The Blue Spike, The Other Statue, The Epipectic Bicycle, The Obsessed Cousins / The Iron Tonic or A Winter Afternoon in the Silent Valley, The Chinese Obelisks, The Soaking Wet Thursday, The Ospick Bird / The Untitled Book, The Eleventh Episode / The Disrespectful Invitation, The Legacy of Miss D. Awdrey-Gore, The Depraved Sock / Leaves from a misplaced Albu m, Category - Katergory, The vanished lions / The lavender-colored jersey, The merciless nosebleed, The blue hour, The soft spoke, The despicable couple

Since April 2013 new translations of Gorey's works have been published by Lilienfeld Verlag in Düsseldorf:

- A questionable guest ( translated from English by Alex Stern), Lilienfeld Verlag 2013, ISBN 978-3-940357-32-8

- The water bloom (from the English by Alex Stern), Lilienfeld Verlag 2013, ISBN 978-3-940357-34-2

- The recently deflowered girl. The right words in every precarious situation. In collaboration with Hyacinthe Phypps (from the English by Alex Stern), Lilienfeld Verlag 2014, ISBN 978-3-940357-44-1

- The other zoo. One alphabet. (from the English by Clemens J. Setz ), Lilienfeld Verlag 2015 (2nd edition: 2019), ISBN 978-3-940357-52-6

- The unfortunate child (from the English by Clemens J. Setz ), Lilienfeld Verlag, Düsseldorf 2018, ISBN 978-3-940357-67-0

- The Osbick bird (from the English by Clemens J. Setz ), Lilienfeld Verlag, Düsseldorf 2020, ISBN 978-3-940357-79-3

Secondary literature

- Victor Kennedy: Mystery! Unraveling Edward Gorey's Tangled Web of Visual Metaphor. Metaphor and Symbolic Activity 8, 3 (1993): 181-193, ISSN 0885-7253

- Hendrik van Leeuwen: The Liaison of Written and Visual Nonsense. Dutch Quarterly Review of Anglo-American Letters 16 (1986): 186-219, ISSN 0046-0842

- Kevin McDermott: Elephant House: Or, The Home of Edward Gorey. Pomegranate, San Francisco 2003, ISBN 0-7649-2495-8

- Clifford Ross, Karen Wilkin: The World of Edward Gorey. Abrams, New York 1996, ISBN 0-8109-3988-6

- Mark T. Rusch: The Deranged Episode: Ironic Dissimulation in the Domestic Scenes of Edward Gorey's Short Stories. International Journal of Comic Art 6, 2 (Fall 2004): 445–455, ISSN 1531-6793

- Kevin Shortsleeve: Edward Gorey, Children's Literature, and Nonsense Verse. Children's Literature Association Quarterly 27, 1 (2002): 27-39, ISSN 0885-0429

- Alexander Theroux: The Strange Case of Edward Gorey. Fantagraphics, Seattle 2002, ISBN 1-56097-385-4

- Wim Tigges: An Anatomy of Literary Nonsense. Pp. 183-195. Rodopi, Amsterdam 1988, ISBN 90-5183-019-X

- Karen Wilkin (Ed.): Ascending Peculiarity. Harcourt, New York 2001, ISBN 0-15-100504-4

- Karen Wilkin: Elegant Enigmas: The Art of Edward Gorey (exhibition catalog). Pomegranate, San Francisco 2009, ISBN 0-7649-4804-0

- Mark Dery, Born to be posthumous: the eccentric life and mysterious genius of Edward Gorey , London: William Collins, 2018, ISBN 978-0-00-832981-5

Web links

- Literature by and about Edward Gorey in the catalog of the German National Library

- Goreyography.com

Individual evidence

- ↑ Biographical information from Alexander Theroux: The Strange Case of Edward Gorey as well as entry "Edward Gorey" in Glenn E. Estes (Ed.): Dictionary of Literary Biography, Volume 61: American Writers for Children Since 1960: Poets, Illustrators, and Nonfiction Authors, pp. 99-107, Gale, Detroit 1987, ISBN 0-8103-1739-7

- ↑ Carol Stevens: An American Original. Print 42, 1 (Jan./Feb. 1988): 49-63, ISSN 0032-8510 . Reproduced in Wilkin 2001, here p. 131

- ^ Edmund Wilson: The Albums of Edward Gorey. In The New Yorker 35 (Dec. 26, 1959): 60-66, ISSN 0028-792X

- ↑ a b c Alison Lurie: On Edward Gorey. The New York Review of Books 47, 9 (March 25, 2000): 20, ISSN 0028-7504

- ↑ a b Tigges, p. 195

- ↑ Ross / Wilkin 1996, pp. 55, 57

- ^ Edmund Wilson: The Albums of Edward Gorey. Quoted in Van Leeuwen, p. 201

- ^ Amy Hanson, Edward Gorey's Fiendish Fables & Bizarre Allegories. Biblio 3, 1 (1998): 16-21, ISSN 1087-5581 , here p. 17

- ↑ Kate Taylor: G is for Gorey who never was sorry. The Globe and Mail, Apr 22, 2000

- ↑ Maurice Sendak , quoted in Shortsleeve, p. 27

- ↑ Shortsleeve, p. 27

- ↑ Tobi Tobias: Balletgorey. Dance Magazine 48.1 (Jan. 1974): 67-71, ISSN 0011-6009 . Reproduced in Wilkin 2001, here p. 23

- ↑ Wilkin 2009, p. 28

- ↑ Kevin Shortsleeve: Edward Gorey, Children's Literature, and Nonsense Verse.

- ↑ Celia Anderson, Marilyn Apseloff: Nonsense Literature for Children: Aesop to Seuss. P. 171. Library Professional Publications, Hamden 1989, ISBN 0-208-02161-2 . Quoted in Shortsleeve, p. 30. See also Jackie E. Stallcup: Power, Fear, and Children's Picture Books. Children's Literature 30 (2002), pp. 125-158, ISSN 0092-8208

- ↑ Shortsleeve, pp. 31-32

- ↑ Ross / Wilkin 1996, p. 61

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 188

- ↑ a b Van Leeuwen, p. 202

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 181

- ↑ a b Steven Heller (Ed.): Man Bites Man, p. 75. A & W Publishers, New York 1981, ISBN 0-89479-086-2 . Quoted in Van Leeuwen, p. 201

- ↑ Kennedy, p. 182

- ↑ a b Kennedy, pp. 188-189

- ↑ Rusch, p. 447 ff.

- ^ "Over the next two years they killed three more children, but it was never as exhilarating as the first had been". Own translation.

- ^ Ed Pinsent: A Gorey Encounter. Speak (Fall 1997), ISSN 1088-8217 . Reproduced in Wilkin 2001, here p. 192

- ↑ Shortsleeve, p. 33

- ↑ a b Van Leeuwen, p. 204

- ^ The Adventures of Uncle Lubin Told and Illustrated by W. Heath Robinson, London 1902

- ^ Clifford Ross: Phantasmagorey: The Work of Edward Gorey (exhibition catalog), foreword. Yale University Library, New Haven 1974

- ↑ Shortsleeve, p. 34

- ↑ Van Leeuwen, p. 203; Shortsleeve, p. 33

- ↑ Stephen Schiff: Edward Gorey and the Tao of Nonsense. The New Yorker, Nov. 9, 1992, pp. 84-94, here p. 89. Reproduced in Wilkin 2001, here p. 147

- ↑ Ross / Wilkin 1996, p. 64

- ↑ Jane Merrill Filstrup: Interview with Edward Gorey. The Lion and the Unicorn 1 (1978): 17-37, ISSN 0147-2593 . Reproduced in Wilkin 2001, here p. 84

- ↑ Own translations. See Tigges, pp. 185 f.

- ↑ Stephen Schiff: Edward Gorey and the Tao of Nonsense. The New Yorker, Nov. 9, 1992, pp. 84-94, here p. 93. Reproduced in Wilkin 2001, here p. 154

- ↑ Amy Benfer: Edward Gorey. Salon.com, Feb. 15, 2000 ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as broken. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ^ Van Leeuwen, p. 206

- ^ George R. Bodmer: The Post-Modern Alphabet: Extending the Limits of the Contemporary Alphabet Book, from Seuss to Gorey. Children's Literature Association Quarterly 14, 3 (1989): 115 ff.

- ↑ Shortsleeve, p. 37

- ↑ Tigges, p. 184

- ↑ Kindly cruel . Die Zeit, No. 41 (Oct. 13, 1967)

- ↑ Shortsleeve, p. 35

- ↑ Ina Rae Hark: Edward Lear. P. 135. Twayne, Boston 1982, ISBN 0-8057-6822-X . Quoted in Tigges, p. 183

- ↑ Ross / Wilkin 1996, p. 55

- ↑ a b Ross / Wilkin 1996, p. 81

- ↑ Ross / Wilkin 1996, p. 63

- ↑ Wilkin 2009, p. 12 f.

- ↑ a b Kennedy, p. 185

- ↑ Simon Henwood: Edward Gorey. Purr (Spring 1995): 22-24, ISSN 1351-4539 . Reproduced in Wilkin 2001, here p. 158; Wilkin 2009, p. 15 f.

- ↑ Ross / Wilkin 1996, p. 57

- ↑ Rusch, p. 451 f.

- ↑ Stephen Schiff: Edward Gorey and the Tao of Nonsense. The New Yorker, Nov 9, 1992, pp. 84-94. Reproduced in Wilkin 2001, here p. 147

- ↑ Van Leeuwen, p. 201 f.

- ↑ Lisa Solod: Interview: Edward Gorey. Boston Magazine 72, 9 (Sep. 1980), ISSN 0006-7989 . Reproduced in Wilkin 2001, here p. 102

- ↑ Tigges, pp. 184-185, 187

- ↑ Tigges, p. 187; Wim Tigges: The Limerick: the Sonnet of Nonsense? Dutch Quarterly Review of Anglo-American Letters 16 (1986): 220-236, here pp. 229-235 ISSN 0046-0842

- ↑ Stephen Schiff: Edward Gorey and the Tao of Nonsense. The New Yorker, Nov 9, 1992, pp. 84-94. Reproduced in Wilkin 2001, here pp. 153–154

- ↑ Tigges, p. 188

- ↑ a b Rusch, p. 453 f.

- ↑ Manuel Gasser: Edward Gorey. Graphis 28 / No. 163 (1972): 424-431, ISSN 0017-3452

- ↑ Wilkin 2009, p. 23

- ↑ "to perform a rather surprising service" (own translation)

- ↑ a b Tigges, p. 189

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Comments on an indignation: Edward Gorey and the obscene (PDF; 280 kB). In: The time . No. 4, January 27, 1967, p. 19

- ^ Paul Gardner: A Pain in the Neck. In: New York . September 19, 1977, p. 68

- ^ Ad libitum: Collection Dispersion 6. Verlag Volk und Welt, Berlin 1987, ISBN 3-353-00225-1

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: The secret of the ottoman: An embarrassment of the Austrian censorship. In: The time . No. 7, February 11, 1966

- ^ Van Leeuwen, p. 203

- ↑ Wilkin 2009, p. 16

- ↑ Shortsleeve, p. 28

- ↑ Tigges, p. 191

- ↑ Ross / Wilkin 1996, p. 69

- ↑ Shortsleeve, p. 38

- ^ A b Edward Gorey and Anchor Books. Collecting paperbacks? 1, 14 ( excerpt from Goreyography ); Steven Heller: Design Literacy: Understanding Graphic Design, pp. 71–74. Allworth, New York 2004, ISBN 1-58115-356-2

- ^ New York Magazine, Nov. 7, 1977, p. 75

- ^ Dracula in the Internet Broadway Database

- ^ Carol Verburg: Edward Gorey Plays Cape Cod: Puppets, People, Places & Plots, pp. 6 f. Self-published. ISBN 978-0-9834355-1-8

- ↑ And Here's the Kicker: Daniel Handler ( Memento of the original from July 7, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. ; Sandra L. Beckett: Crossover Fiction: Global and Historical Perspectives, p. 165. Routledge, New York 2009, ISBN 0-203-89313-1

- ^ Paul A. Woods: Tim Burton: A Child's Garden of Nightmares, pp. 10 f., 105. Plexus, London 2002, ISBN 0-85965-310-2

- ↑ Mark Dery: Edward Gorey's sensibility is growing like nightshade. The New York Times, March 6, 2011, ISSN 0362-4331

- ↑ Interview with Mark Romanek (YouTube)

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Gorey, Edward |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Gorey, Edward St. John (full name) |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | American author and illustrator |

| DATE OF BIRTH | February 22, 1925 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Chicago , Illinois , United States |

| DATE OF DEATH | April 15, 2000 |

| Place of death | Hyannis , Massachusetts , United States |