Ecclesiology (Roman Catholic Church)

In Roman Catholic theology as well as in other denominations, ecclesiology is the name given to the doctrine of the Church . It includes the methodical theological reflection on the Ekklesia ( ancient Greek ἐκκλησία ekklēsía , Latin ecclesia the 'called out'), translated as “church” in the Catholic area. According to New Testament usage, the Ekklesia is the community of those who have been called out of the world by Jesus Christ through the Gospel , believe in him, gather around him in worship (λειτουργία leiturgía) and from him for testimony of faith (μαρτυρία martyría) and service of love (διακονία diakonía 'service', from διάκονος diákonos 'servant'). The Second Vatican Council sees the Church as “the sacrament , that is, the sign and instrument for the most intimate union with God and for the unity of all humanity” ( Lumen Gentium 1).

Classification of ecclesiology as a science

The scientific discipline of ecclesiology is a subject area ( treatise ) of dogmatics . The New Testament is of fundamental importance as a written record of the “faith experience of God's final promise of salvation and its acceptance by the believing community”; her from teaching based handing down and design, such as theology, faith proclamation and liturgy , in legal norms and constitution of the church maintain their validity only on the background of legitimate interpretation of biblical testimony.

Aspects of ecclesiology are also covered by biblical exegesis , church history , practical theology and canon law . As a theological discipline, ecclesiology wants to formulate the faith of the church in a scientifically clarified manner within the framework of the church; this distinguishes them from religious studies and religious philosophy , which work scientifically independently of the church. Hence the church is both an object and a subject of ecclesiological endeavors. Church becomes objectively, passively determined as the result of divine action and activity ("Church as gathered", which "belongs to the saving gifts of the living God") and at the same time - as a community of believers - as the subject of human actions ("Church as gathering", as a "call to the community").

Ekklesia in the New Testament

The Greek word ἐκκλησία ekklēsía meant a gathering of people and especially a people's assembly in profane usage. It was also used for the gathering of the people of God Israel and was adopted by the Christian community (for example Heb. 2.12 EU , Acts 7.38 EU ). In the New Testament it is the congregation that gathers for worship , the local congregation or the local church ( 1 Cor 1, 2 EU ), but also the community of all local congregations as the “universal church”.

Ecclesiological Lines of Development

Essential attributes in the creeds

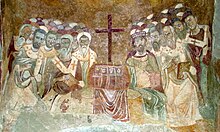

Already in the time of the early church the fundamental essential attributes of the church developed. Already in the ancient Roman creed (approx. 135) holiness is mentioned as an attribute of the church, in the creed of Nicaea (325) catholicity and apostolicity are added. In the 381 extended form, the Nicano-Constantinopolitanum , the four attributes appear together for the first time, which have been essential and distinguishing features of the "true" church since the early modern period:

"We believe [...] the one, holy, catholic and apostolic church"

Church order and structure

According to the Catholic church historian Norbert Brox , the word Ekklesia was initially, even in early Christianity , a name for the individual local congregation. “The individual local church did not have to rely on anything outside of itself in order to be a church in its entirety. At the same time, however, the church meant the communion of the local churches from the outset. ”In the first Christian centuries there was a network of local churches of equal rank, led by bishops. This corresponded to a variety of church ordinances, creed formulas and liturgical traditions. One was aware of this plurality, but (in spite of occasional conflicts) one did not see the unity in faith endangered by the difference. Since the individual local churches mutually agreed to have been founded by an apostle, and since all apostles were in agreement with one another, “apostolicity” guaranteed unity in faith and communion (koinonía, communio) of the local and particular churches.

Early Christianity knew two types of church constitution; both had a collegial structure:

- Leadership by elders (presbyters) based on the Jewish model;

- Direction by episcopes (overseers, "bishops") in the Pauline mission areas.

In the post-apostolic period, the church leadership became a sacramental office, whereby the ministerial official was given authority through ordination. The institutionalization of the church, combined with a hierarchy of offices, is, according to Brox, a fact of church history, but “cannot be described as a“ divine institution ”of a mythical nature and can be dated back to Jesus or the apostles. It is true that it was the old church itself that traced what had become to the institution of Jesus and the apostles, but it did so, as we know today, not on the basis of historical memory, but under the influence of theological guiding ideas. "

To ward off heresies, Irenaeus of Lyon developed a historical construction according to which every bishop went back in complete succession to a predecessor appointed by an apostle or apostle student; for him, the ministry also ensured the transmission of orthodox doctrine that was entrusted to the bishops. Another component in the 2nd to 4th centuries was the cultic interpretation of the office: Bishops and presbyters were now increasingly understood as priests. Ignatius of Antioch developed the theology of a monarchical episcopate; The hierarchical image of the church was designed as a correspondence to the heavenly order and was therefore inviolable ( Pseudo-Dionysius Areopagita , around 500 AD). This derivation of the church order from a heavenly model was a very influential concept for the Middle Ages.

The First Council of Nicaea confirmed the primacy of the bishops of larger cities (Metropolitan Order, Canon 4) and at the same time a superordinate institution: the bishops of Alexandria, Rome, Antioch and other large cities were to have supreme power over a large territory encompassing several provinces (Canon 6). The result was the broad division of the church into patriarchates . While in the east of the empire, where Christianity was born, many places had apostolic traditions, Rome was the only foundation of the apostles in the west, and this legitimized a centralized constitution headed by the bishop of Rome. After Brox, it was only Damasus I who saw himself as pope and adopted the imperial decretal style. When the western empire collapsed at the end of late antiquity, the Roman Church under Leo I succeeded the emperor and empire, while at the same time adopting elements of the pagan Rome idea. However, this is a development that the Eastern Roman Empire did not grasp and therefore does not play a role in the ecclesiology of Orthodox churches.

Cyprian of Carthage developed the doctrine that it is necessary for salvation to have a share in the lawfully administered sacraments within the church. This found expression in the sentence Extra ecclesiam nulla salus (which cannot be found literally in his work, but was later often quoted as a catchphrase) . Even Augustine argued in his writings against the Donatists that the sacraments their healing properties (institutionally understood) only in the ecclesia catholica unfold. He determined this as a corpus mixtum of good and bad, which are only separated in the final judgment; the ideal of a church consisting only of “pure” is thus rejected (cf. Mt 13 EU ). As a corpus mixtum , the church is part of the kingdom of God preached by Jesus .

Ecclesiology as controversial theology

Such individual statements about the church were not yet developed into a systematically elaborated ecclesiology in the time of the church fathers and also in high scholasticism . This only began in the phase of controversial theology as a result of the Reformation from the 16th century. The urge to differentiate itself from other denominations led the Catholics to overemphasize the institutional side of the church; To a large extent, ecclesiology was a “doctrine of the ecclesiastical office” - with the risk of overestimating the institution and the office - and was developed as a “question of the true church”. The question “Which community can rightly be traced back to Jesus Christ?” Linked ecclesiology to Christology , according to Peter Neuner : “Church lives from the power of the resurrection of Jesus , ecclesiology proves to be a consequence of Christology. The church has a share in God's plan of salvation. ”The apostolicity of the church is still tied to the apostolic succession in the episcopate because through personal commission, through consecration and the laying on of hands during episcopal ordination, the sacramental structure of tradition and discipleship becomes clear.

Since the 19th century, the view of the church as “ societas perfecta ” has been determining; Pope Leo XIII. In 1885, in his encyclical Immortale Dei, wrote in relation to the Church:

“[…] It is a perfect society of its own kind and of its own right, since it possesses everything that is necessary for its existence and effectiveness in accordance with the will and by virtue of the grace of its founder in itself and through itself. Just as the goal to which the Church strives is by far the most sublime, so her violence is also far superior to all others, and it must therefore neither be regarded as inferior to civil violence, nor be subordinated to it in any way. "

The theologian Peter Neuner describes the then prevailing view of the form of the church as a “society of unequal ( societas inaequalis )”, which was traced back to a position of God: The church “is hierarchical, i.e. H. strictly top-down structured society. The subject of church activity is the clergy alone ; the laity appears as an object of clerical care and support ”. This culminated in the primacy of jurisdiction and in papal infallibility according to the teaching of the First Vatican Council (1870). The church, according to Peter Neuner, is only understood in terms of its offices. It cultivated its own culture and, in the current of anti- modernism, took the defensive against modernity; it condemned social achievements such as democracy , freedom of religion and freedom of the press . In 1964, the Second Vatican Council also declared infallibility to the whole of the faithful: “The whole of the faithful who have the anointing of the holy cannot err in the faith.” This council dedicated the declaration Dignitatis humanae on “law ” to religious freedom of the person and the community on social and civil freedom in the religious area ", in the Council Decree Inter mirifica , No. 12 expressly declares freedom of the press as worthy of protection, since today's society requires" true and right freedom of information ".

The change of perspective was initiated by theologians such as Johann Adam Möhler († 1838) and the Tübingen School , who emphasized the early church concept of the mystery of the church as a counterweight to the church's institutionalism. After the First World War, there was an “ecclesiological awakening ” (Peter Neuner), accentuated by Romano Guardini's coining of the term “the church awakens in souls”. The departure was marked by the liturgical movement and the Catholic action , by the Catholic youth movement and the Catholic academic movement , by authors such as Karl Adam , the poet Gertrud von Le Fort with her “Hymns to the Church” (1924) and the Dominican Yves Congar who described the church as a community in the sense of the church fathers.

Especially the encyclical Mystici corporis by Pope Pius XII. determined Catholic ecclesiology in the middle of the 20th century. The Pope emphasized the institutional aspect of the church, but also took up the mystery character of the church , which had come back into consciousness . A purely legal understanding of the church is corrected in favor of a single, indivisible organism led by the Holy Spirit , in which the unity of all and the individuality of the individual grow at the same time; Church is a community that is both visible and invisible. However, a clear demarcation is maintained from outsiders: “Just as there is only one body, only one Spirit, one Lord and one Baptism in the true community of believers in Christ, so there can also be only one faith in it (cf. Eph 4, 5 EU ); and that is why whoever refuses to listen to the Church is to be regarded as a pagan and public sinner according to the commandment of the Lord (cf. Mt 18:13 EU ). For this reason, those who are separated from one another in faith or in leadership cannot live in this one body and out of its one divine spirit. "(Mystici Corporis 22)

Ecclesiology of the Second Vatican Council

At the Second Vatican Council, the Catholic Church expressed itself for the first time in an overall view on its understanding of the church, emphasizing various aspects. Sources of understanding the church are the Holy Scriptures and our own tradition . Traditionally, the seven sacraments and the ecclesiastical office are particularly important to her. However, with the Dogmatic Constitution Lumen Gentium on the Church (1964) , the Council no longer starts “with the institutional elements of the Church, but with its spiritual nature as a“ community of faith, hope and love ”[…] and marks it thus a turn towards an ecclesiology of communion in the Catholic area. ”The premises are now included in the designation of the church as the basic or primordial sacrament, a view that defines the church as an instrument and sign of God's will of salvation for the whole world.

Pope John Paul II summarized the essential aspects of the Council's ecclesiology as follows:

- "The doctrine according to which the church as the people of God ...

- ... and the hierarchical authority is presented as a service ”;

- "The teaching that the Church as a community ( communion constitutes identifies)" and therefore the necessary relationships that must exist between the particular Churches and the universal Church, and between collegiality and primacy;

- "The doctrine according to which all members of God's people, each in his own way, partake of the threefold office of Christ - the priestly, prophetic and royal office";

- "Doctrine ... concerning the duties and rights of believers, especially of the laity ";

- "The commitment that the church must muster for ecumenism ."

Reason and aim of the church

The church is founded in the word and work of Jesus Christ :

“For the Lord Jesus made the beginning of his church (initium fecit) by proclaiming the good news, namely the coming of the kingdom of God , which was promised from ancient times in the scriptures: 'The time is fulfilled and the kingdom has drawn near Of God '( Mk 1.15 EU ; cf. Mt 4.17 EU ) "

The coming of the kingdom of God is evident in the proclamation of Jesus, his mighty acts, in his suffering and death and in his resurrection . It is not the work of the earthly Jesus, but of Christ exalted in the Paschal mystery : the risen One appeared to the disciples after Easter , promised them the assistance of the Holy Spirit and gave them the task of preaching the Gospel and baptizing people:

“When he had completed the mysteries of our salvation and the renewal of everything once and for all through his death and resurrection, he founded [...] his church as a sacrament of salvation before he was taken into heaven, sent the apostles in All the world, just as he himself had been sent by the Father, and charged them: 'Go then and make disciples of all the nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit, and keeping them all teach what I have commanded you '( Mt 28 : 19-20 EU ) "

However, according to the unanimous view of the Catholic ecclesiology after the Second Vatican Council, this can no longer be understood as the formal founding of a church under corporation law in the sense of an institutional setting by Jesus himself, as the theology of the Counter Reformation had accentuated for apologetic reasons. In the representation of the church in the New Testament, testimonies of faith from post-Easter parish situations with their experiences and problems have flowed, which interpret the life of the congregations "in the light of the message and the history of Jesus, theologically process and legitimize" and thus faithful to the original intention of their founder Jesus stay. Theologians speak of a “structural continuity” between the gathering of Israel by Jesus and the post-Easter emergence of the church; Jesus set “community-building signs of the coming kingdom of God”, which “based on the resurrection and spirit experience of the first witnesses [...] were taken up and updated as pre-forms of the post-Easter church”; the foundation of the church is thus “in the whole Christ event”, his earthly work, his death and his resurrection up to the sending of the spirit.

The calling of the church through Jesus Christ and its eschatological goal correspond to a plan of salvation of God himself:

“But before all time, the Father 'foreseen and predestined all the chosen ones to become conformed to the image of his Son, so that he might be the firstborn among many brothers' ( Rom 8:29 EU ). But those who believe in Christ, he decided to call together in the holy church. It was foreshadowed from the beginning of the world; in the history of the people of Israel and in the old covenant it was wonderfully prepared, established in the last times, revealed by the outpouring of the Holy Spirit, and at the end of the ages it will be made perfect in glory. "

In the Church, Christ himself is effectively present until the end of time. As such, the church is the object of the basic creeds and is called the "one, holy, catholic and apostolic" church. The Eucharist , the breaking of bread together according to Jesus' commission to do this in memory of himself (cf. 1 Cor 11 : 23-25 EU ), was of great importance for the unity and identity of the Christian community .

The council theologian Karl Rahner SJ gave a definition of church in 1964: “The church is the socially legitimately constituted community in which through faith, hope and love the eschatologically perfect revelation of God (as his self-communication) in Christ is present as reality and truth for the world remains."

Spiritual origin of the church: Jesus' death on the cross

According to a reading that goes back to Ambrose of Milan and Augustine of Hippo , the spiritual place of origin from which the church comes, from which the sacraments also come, is the wound on the side of Jesus on the cross ( Jn 19 : 33-34 EU ).

Joseph Ratzinger takes up this old church tradition and combines it with modern exegetical considerations: According to the Gospel of John, Jesus died exactly at the hour at which the Easter lambs were slaughtered for the Passover in the Jerusalem temple . This is interpreted to mean that the true Paschal Lamb came in the form of Jesus Christ, God's Son. For the page of Jesus that is opened, the evangelist used the word πλευρά pleurá , which appears in the Septuagint version of the creation story in the account of the creation of Eve ( Gen 2.21 EU ). With this, John makes it clear that Jesus is the new Adam who descends into the night of the sleep of death and in it opens the beginning of the new humanity. “From Jesus' gift of death flow blood and water, Eucharist and baptism as the source of a new community. The open side is the place of origin from which the church comes, from which the sacraments that build the church come. "

The Second Vatican Council put this derivation in the introductory chapter of its Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Lumen Gentium :

“The church, that is, the kingdom of Christ already present in mystery, grows visibly in the world through the power of God. This beginning and this growth (exordium et incrementum) are symbolically indicated by the blood and water that flowed out of the open side of the crucified Jesus (cf.Jn 19:34), and foretold by the words of the Lord about his death on the cross: 'And I, when I am lifted up from the earth, will draw everyone to me '( Jn 12.32 EU ). Whenever the sacrifice on the cross, in which Christ, our Paschal Lamb, was given up ( 1 Cor 5,7 EU ), is celebrated on the altar, the work of our redemption takes place. At the same time, through the sacrament of the Eucharistic Bread, the unity of the believers, who form one body in Christ, is represented and realized ( 1 Cor 10:17 EU ). All people are called to this union with Christ who is the light of the world. "

Sacramentality and Principles

According to a long theological tradition, Jesus Christ himself is understood as the "primordial sacrament", the origin and goal of divine saving action in the world, as was the case with Augustine of Hippo and Thomas Aquinas . Even Martin Luther wrote: "Only a sacrament only knows the Scriptures, which is Christ the Lord himself." For the members of the Roman Catholic Church is the presence of Christ in the Church by its nature sacramental experience. The church is “sacrament, sign and instrument” of God's saving action in the world and brings about “the most intimate union with God” and “the unity of the whole human race” (Ecclesia sit veluti sacramentum seu signum et instrumentum intimae cum Deo unionis totiusque generis humani unitatis ) , a name that goes back to the Doctor of the Church Cyprian of Carthage ., namely as "sacrament of unity" (unitatis sacramentum)

The doctrine of the sacramentality of the church, which emphasizes the unity of divine saving action, belongs to the core of the Dogmatic Constitution Lumen Gentium of the Council, according to the Council theologian Joseph Ratzinger . The Fathers of the term was Mysterion / sacramentum only sporadically applied to the church. In the 20th century, the idea is first found in the theologian George Tyrrell , who was then excommunicated as a modernist , who wanted to accentuate the difference between the community of believers and the hierarchical institution of the church. Since the 1930s, the idea of the church as a basic or root sacrament - in addition to the designation of Jesus Christ as the "primordial sacrament", according to Karl Rahner - by theologians such as Carl Feckes , Hans Urs von Balthasar , Henri de Lubac OP, Karl Rahner SJ and Otto Semmelroth SJ developed and incorporated it into the template for Lumen gentium .

With the application of a broad concept of the sacraments to the church, the council wanted to describe the symbolic and testimony of divine saving acts in history, the relationship between the hidden, spiritual reality of the church and the visible, institutionalized church, and it is about the relationship of the Action of God for action of man.

According to the theologian Medard Kehl , this definition interprets the church as “the event of the making present of Jesus Christ and his ultimate salvation” and fends off both a mystifying exaggeration of the church and its purely functional devaluation. The church must therefore not be equated with salvation, the present Christ or the kingdom of God that has already arrived; rather, the salvation given by God is only shown analogously, “in the finite and sinful sign of the church”. That is why their historical contingency , continuity and global organic unity, guaranteed by the bishops as successors of the apostles , have theological relevance. Theologians such as Hans Küng , Leonardo Boff and Wolfgang Beinert reject too great a kinship between the church and the kingdom of God: “The church is not the surviving Christ, but only his sacrament, that is, a substantially imperfect tool, which in a certain analogy to its Lord stands, but in such a way that the dissimilarity is greater than the similarity, as is the case with any understanding of analogy. "Hans Küng emphasizes the substantial separation between the created church and the uncreated God:" Any deification of the church is excluded. "

The practice of the sacraments, which is fundamentally linked to the church as an organizational form, is decisive for personal faith. In the tradition of the Roman Catholic Church, the number of seven individual sacraments has emerged, which was established in its seven number by the second council of Lyon on July 6, 1274.

The basic functions of the church from the point of view of today's Catholic theology take up the tradition of the three offices of Christ ; The church therefore takes place in witness or “faith service” ( martyria ), liturgy or “worship” ( ancient Greek leiturgia ) and diakonia ( diakonia ) or “brotherly service”. Since the Second Vatican Council, a fourth basic dimension of the church has also been mentioned, the community ( communio / koinonia ).

Body of Christ

A central concept in the New Testament is that of the Ekklesia as the body of Christ into which one is incorporated through baptism and the Eucharist . It can be found in the Pauline letters and, with a different emphasis, in the letters of the Pauline School (Colossians and Ephesians):

“For just as we have many members in one body, but not all members have the same task, so we, the many, are one body in Christ, but as individuals we are members who belong to one another. We have different gifts depending on the grace bestowed upon us. "

The concept of the body of Christ in Romans and 1 Corinthians is rooted in participation in the Lord's Supper founded by Jesus ( 1 Cor 10 : 16f EU ). This Eucharistic table community constitutes “the functional unity of the organism”, in which a “togetherness shaped by Christ”, similar to baptism , overcomes the differences between the members ( Gal 3:26 ff EU ). The impulse emanating from the Lord's Supper remains decisive even after the service, in the everyday life of Christians in the community. Through baptism, the person enters into the context of life with Christ, which is historically visible in belonging to the local church: "Through the one Spirit we were all received into one body in baptism." ( 1 Cor 12 : 13 EU )

The "Deuteropaulin" letters written by students of Paul, the Letter to the Colossians and the Letter to the Ephesians , see the body of Christ metaphor in a cosmic-mythological understanding. Jesus Christ is the "head", the Ekklesia - now understood as the whole Church - is the body that is built up and stabilized from the head ( Eph 4.15f EU ) and in which eschatological peace can already be experienced ( Col 1, 18-20 EU ).

The encyclical Mystici corporis of Pope Pius XII. (1943) was all about the metaphor of the body of Christ. In the organic-pneumatological picture of the church, whose head is Jesus Christ, there are still elements of a hierarchical concept; The demarcation from outsiders is emphasized in favor of a spirit-guided unity of the members of the body. Within the organism, however, it is the case that the individual members with their respective functions are dependent on one another for the whole body and especially the weakest members deserve the solidarity of all.

The Second Vatican Council mentioned the concept of the body of Christ on several occasions, but devoted only one article to it in the Church Constitution Lumen Gentium (No. 7). More decisive for the council is the - less exclusive - concept of the “people of God”, which replaced the previously prevailing idea of the church as the body of Christ. This was viewed by the Council Fathers as too timeless and immutable, difficult to reconcile with the idea of a development in the Church and her teaching; the differences between the estates in the Church are overemphasized and obscure the fundamental equality of all Christians; in addition, one saw the difficulty of "doing justice to the fact of sin in the church".

People of god

The concept of the “people of God” is one of the central ideas in the ecclesiology of the Council, which referred to the Doctor of the Church Augustine.

“The Church is at the same time holy and always in need of purification, she is always on the path of repentance and renewal. The Church "walks between the persecutions of the world and the consolations of God on her pilgrimage" and proclaims the cross and the death of the Lord until he returns (cf. 1 Cor 11:26 EU ) [...] but God liked it, not to sanctify and save people individually, regardless of all mutual connection, but to make them into a people that should recognize him in truth and serve him in holiness. "

In the reception of the dogmatic Council Constitution Lumen Gentium , the description of the social form of the church as the pilgrim people of God in Chapter II of the Constitution dominated in the decades after the end of the Council , because this conception was “beneficial” compared to the fixed hierarchical church thinking of the 19th century. far '”was felt. From this paradigm the “true equality in the dignity and activity common to all believers for the building up of the body of Christ” is derived, since “all are called to holiness” and “have obtained the same faith in God's righteousness” (cf. 2 Pet 1, 1 EU ). The council includes in this provision the covenant of God with his chosen people Israel , who are not released from the covenant and divine promise; it does not understand the church as a perfect society, but as a people that is approaching its perfection through God's eschatological action at the second coming of Christ .

Church as a community (Koinonia / Communio)

The regaining of the idea of the church as a community of believers is considered to be one of the decisive decisions of the council. Communio-theology considers the being of the church as a community ( ancient Greek κοινωνία koinonía , Latin communio ) between God and human beings, realized through the word and the sacrament as "fellowship in the gospel and at the table of the Lord", founded in Holy Spirit . The church is a “theocentric” community: the community of believers arises from communion with God in the Holy Spirit. It is a fellowship between the apostle and his church, between the local churches among themselves and between individuals and groups of people. After the Second Vatican Council, the term became significant as a counterpoint to an overly hierarchical, monolithic conception of the church, which distinguished between the "teaching church of the clergy and the listening church of the laity". There is a fundamental equality between officials and “laypeople”, which results from the common “dignity of the members from their rebirth in Christ” - baptism - and a common “call to perfection”: “Even if some according to God's will as teachers, Distributors of secrets and shepherds are appointed for the others, a true equality prevails among all in the dignity and activity common to all believers in building up the body of Christ. The difference which the Lord has made between consecrated ministers and the rest of the people of God includes a bond, since the shepherds and the other believers are closely related. The pastors of the church are to serve one another and the rest of the faithful, following the example of the Lord, but they are to work diligently with the pastors and teachers. Thus all in diversity bear witness to the wonderful unity in the body of Christ ”( Lumen gentium no. 32).

Because the term Koinonia means unity in diversity and not “uniformity”, the term also has an important function for ecumenical thinking. What is particularly important in this is the “unified office of Peter” - the papacy .

The council understands the church as a visible assembly and spiritual community; the earthly church and the church endowed with heavenly gifts form a single complex reality that grows together from the human and divine elements. According to the Catholic understanding, the “mystical body of Christ”, the community of saints , includes the members of the earthly church “who make a pilgrimage here on earth”, but also those “who are purified after the end of their earthly life ” and the deceased who “ enjoy heavenly bliss ”; together they form the one church. The council takes up the determination of the church, which essentially goes back to Augustine, as a pilgrim ecclesia militans ("contending church"), which is associated with the ecclesia triumphans ("triumphant church") - the saints in the view of God - and the " poor souls " in purgatory , which is connected to ecclesia patiens ("suffering church").

One of the most important rediscoveries of the Second Vatican Council, according to Siegfried Wiedenhofer, is the “local church”.

“The Church of Christ is truly present in all legitimate local communities of believers who, in their union with their pastors, are called churches in the New Testament. For they are each in their place [...] the new people called by God. In them the believers are gathered together through the proclamation of the good news of Christ, in them the mystery of the Lord's Supper is celebrated [...]. In every altar community appears under the sacred office of the bishop the symbol of that love and that "unity of the mystical body, without which there can be no salvation". In these communities, even if they are often small and poor or live in the diaspora, Christ is present, through whose power the one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church is united.

The one and only Catholic Church consists of them and of them. "

In contrast to the idea of the "universal church" with the Pope as "world bishop", where the dioceses function as administrative units, the principle of the "local church" now applies. This means the diocese under the direction of the bishop, which is connected to other dioceses, so that the whole church is realized as a network of cross connections. The inculturation of Christianity takes place in the local churches, which can lead to differences between the individual dioceses. The local parishes and also personal congregations are then pragmatic subdivisions of the diocese, in which a pastor as pastor proprius (“one's own shepherd”) represents the bishop of the parish entrusted to him, because the bishop “neither always nor everywhere presides over the entire flock in person can ”( Sacrosanctum concilium No. 42).

In this context, the episcopate was upgraded. The local bishop does not represent the Pope in his diocese, but has “his own ordinary and direct power, even if its execution is ultimately regulated by the highest ecclesiastical authority and with certain limits in view of the benefit of the church or the faithful can ”( Lumen Gentium No. 26); his office is thus divine right and cannot be derived from the papal office, but is subject to the pope's primacy of jurisdiction . The bishops form a college: “Just as, according to the Lord's decree, St. Peter and the other apostles form a single apostolic college, so the bishop of Rome, the successor of Peter, and the bishops, the successor of the apostles, are in a corresponding way with one another united ”and in a special way when they meet as a council . The Pope is the head of the college of bishops and "the everlasting, visible principle and foundation for the unity of the multiplicity of bishops and believers". The college of bishops has authority only in communion with the Bishop of Rome; together with the Pope, however, the bishops are “also bearers of the highest and full authority over the whole Church”. The council expressly understands the statements on the collegiality of the bishops as a continuation and addition of the statements of the First Vatican Council on the primacy of the Pope.

Church of the Poor

The discipleship of Jesus and the task of the church are concretely concretized today in the option for the poor , a partiality as promoted by liberation theology as “theology of the poor”. She also received fundamental impulses from the Second Vatican Council:

“So the Church, even if she needs human means to fulfill her mission, is not founded to seek earthly glory, but to spread humility and self-denial also through her example. Christ was sent by the Father to 'bring good news to the poor, to heal the oppressed in heart' ( Lk 4,18 EU ), to 'seek and save what was lost' ( Lk 19,10 EU ). In a similar way the Church surrounds with her love all those who are challenged by human weakness, yes, in the poor and suffering, she recognizes the image of the one who founded her and was himself poor and suffering. It strives to alleviate their need and seeks Christ to serve in them. "

The option for the poor represents a significant change of perspective: “The poor can no longer be treated as 'objects' of a paternalistically condescending church. In a church with the poor, which enters the world of the poor and shares its conditions in friendship and solidarity, the poor themselves become subjects of the church and their common faith ”; the poor are not only “the preferred addressees of the gospel, but also its bearers and heralds” (cf. Mt 11.25 EU ).

Ecclesiological metaphors

The council described the church as "the kingdom of Christ already present in the mystery " (LG 3); it aimed to determine the essence of this mystery not through a single term, but “through a multitude of mutually correcting and complementing images and terms”. In addition to the ones already mentioned, these are:

House and Temple of God

The pastoral letters choose the οἶκος oíkos "house, residence" as the guiding metaphor for the community as an institution . Housekeeping played a central role in the urban culture of the eastern Mediterranean, where Christianity spread; the “whole house” was the family residence, but also the production facility, business premises and meeting place for relatives, business partners and workers under the direction of the pater familias . The model of the late antique family business is transferred to the local congregations of the developing, settled early Christianity and gives them reliability and stability after the Christians were expelled from the synagogue at the Synod of Jabne .

The council stated:

“This building has different names: House of God ( 1 Tim 3,15 EU ), in which the family of God lives, dwelling place of God in the spirit ( Eph 2,19-22 EU ), tent of God among men ( Rev 21,3 EU ), but above all the holy temple, which the holy fathers see and praise depicted in the stone sanctuaries and which in the liturgy is rightly compared with the holy city, the new Jerusalem . We are already inserted into this building on earth as living stones ( 1 Petr 2.5 EU ). "

In Lumen Gentium, the church is often referred to as “Temple of the Holy Spirit” based on 1 Cor 3:16 EU ; only where the Spirit of God is at work is the church, as an essentially “pneumatic structure”, fully given.

bride of Christ

The motif of the church as the bride of Christ, "the flawless bride of the flawless Lamb ( Rev 19.7 EU ; 21.2.9 EU ; 22.17 EU )" ( Lumen gentium 6) takes up the Old Testament motif of marriage between YHWH and his people on. It expresses the mutual love and personal openness between Jesus Christ and the Church, which also includes the obligation to believe and love. At the same time, however, the non-identity of Christ and the Church is stated, so that the Church as an “unfaithful bride” can also become the Church of sinners.

The Church as Mother - Mary as "Mother of the Church"

In Lumen Gentium 6, the council takes up the biblical designation of the church as “our mother” ( Gal 4,26 EU ; cf. Rev 12,17 EU ); her motherliness is shown by the fact that she guides people through word and sacrament like a mother leads her children. In Lumen Gentium 53, Mary , the Mother of God, is referred to as the “beloved mother” of the Church, a title of Mary that goes back to the Church Father Ambrosius of Milan .

Churches and Ecclesial Communities

On the question of overcoming the divisions between the churches, the Second Vatican Council initially broadened the perspective by perceiving other denominations in terms of their ecclesiastical nature and placing unifying elements in the foreground. However, from the 1990s onwards, this development was put into perspective by some statements made by teachers who emphasized the deficit status of non-Catholic groups.

Controversies after the Reformation

In response to the Reformation, the Council of Trent codified only a few controversial aspects of ecclesiastical ministry, mainly the question of ordination , the difference between priests and lay people and a tripartite clerical hierarchy of diaconate , presbyterate and episcopate . According to the theologian Peter Neuner, this was subsequently understood as a comprehensive doctrine of the church as a “visible, institutionally well-defined size” that was largely identified with the hierarchy and especially with the papacy . The Roman controversial theologian and Cardinal Robert Bellarmine coined the classic definition of the Roman Catholic concept of the church:

"That one and true (Church) is an association ( coetus ) of people who, through the confession of the same Christian faith and through the communion of the same sacraments, under the guidance of the legitimate shepherds, above all the one representative of Christ on earth, the Roman Pope, connected is."

There couldn't be several churches side by side; the Roman Catholic Church saw itself as the Church of Christ in full reality, other episcopal churches (cf. autocephaly ) were at best considered as particular churches, but not as (Catholic) "Church in the real sense". By the 19th century, this idea was solidified up to the definition of primacy of jurisdiction and papal infallibility in the First Vatican Council (1870).

Second Vatican Council

The Second Vatican Council brought about a change here. The ecumenism decree Unitatis redintegratio paid tribute to the ecumenical movement and called on Catholics to participate. Instead of speaking of "schismatics and heretics" as it did before, the council now spoke of "separated brothers". In place of a “return ecumenism”, which only demanded a movement from the other churches, the council set the goal of “helping to restore the unity of all Christians”.

The “Communio-Theology” of the Council allows further development because it enables certain conceptual openings:

- In the church constitution Lumen Gentium (No. 8) it says: “This church, composed and organized as a society in this world, is realized ( subsistit ) in the Catholic Church, which is led by the Successor of Peter and by the bishops in communion with him . ”In the draft of the constitution, the predicate est (“ is ”) was used instead of subsistit . According to Peter Neuner, the choice of the term subsistit “has overcome a simple and exclusive identification of the Roman Catholic Church with the Church of Christ”; "The Church of Jesus Christ [...] appears in the Roman Catholic Church in a concrete form in a historically limited form". This “self-relativization” allows the statement “that the church of Christ also experiences a specific, limited realization in other church forms”.

- The council assumes a tiered church membership and also sees "outside of its structure various elements of sanctification and truth [...] which, as gifts peculiar to the Church of Christ, urge Catholic unity" ( Lumen Gentium No. 8). It recognizes people “in their own churches or ecclesiastical communities ” - as the name has been customary since then - “who are part of the honor of the Christian name through baptism”, and knows that it is connected to them “even if they do not profess or fully believe fail to preserve the unity of the community under the Successor of Peter ”( Lumen gentium n. 15). The council deliberately leaves open which group is meant by “church” or “ecclesial community”. The Orthodox churches have been referred to as churches before. Unitatis redintegratio (heading to Part II and No. 19) deals with “separated churches and ecclesiastical communities in the West”, “those in the severe crisis that began in the West at the end of the Middle Ages, or later on from Roman Apostolic See were separated “. Some Christian groups do not see themselves as a church.

Unitatis redintegratio explains “that some, indeed many and important elements or goods from which the Church as a whole is built and gains its life can also exist outside the visible limits of the Catholic Church: the written word of God, the life of grace , Faith, hope and love and other inner gifts of the Holy Spirit and visible elements: all this that proceeds from and leads to Christ belongs rightly to the only Church of Christ. ”For ecumenical dialogue the Council refers to the hermeneutical principle of one " Hierarchy of truths within Catholic doctrine, according to the various ways in which they are related to the foundation of the Christian faith". For Gerhard Feige this means the transition from an exclusivist to an inclusiveist ecclesiology.

Peter Neuner recalls that the concept of accepting "ecclesiastical elements" outside the formal church ("element ecclesiology") was developed in 1950 by the World Council of Churches , to which the Roman Catholic Church is not a member, and has now been converted into a Roman- Catholic document flowed in. The members of the World Council do not necessarily recognize one another as churches in the full sense of the word; the Toronto Council Declaration of 1950 had stated: “The member churches of the World Council recognize elements of the true church in other churches. [...] They hope that these elements of truth will lead to an acknowledgment of the full truth and unity [...]. "The concept of Vestigia Ecclesiae (" traces of the "Church) goes to the reformer John Calvin back and was included in the 20th century by Roman Catholic theologians such as Yves Congar and Walter Kasper ; Kasper called these "traces" or "elements" "promising points of contact". - The council regards the unity of the church as broken; for the fullness of the church's existence, fellowship with the church is to be striven for. The Council, however, avoids speaking of the “return” of the separate communities to the Roman Church. Peter Neuner points out that the Roman Catholic Church itself is viewed as deficient in the face of the split, because the split prevents the Church from “allowing its own fullness of catholicity to take effect in those sons that it is through belonging to Baptism but separated from their full communion ”. The split makes it more difficult for the Church herself to “express the fullness of catholicity in every aspect in the reality of life”. ( Unitatis redintegratio No. 4)

Current development

The question of mutual recognition as “church” is a central problem of the current ecumenical movement . There is a lively exchange between the denominations on factual issues; In the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification , a significant rapprochement between Lutherans and Catholics was achieved in 1999, after which the differences over justification and the practice of indulgence , which had broken the unity of the Western Church during the Reformation, were overcome. The doctrinal condemnations that relate to the doctrine of justification have thus lost their church-dividing effect.

The declaration of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith Dominus Iesus , published on August 6, 2000, repeated formulations of the council. While the basic motive in the ecumenism decree was to name something that unites, the defect of communities without a valid episcopate has now been emphasized without, however, completely denying them an ecclesiality:

“The ecclesiastical communities ( Communitates ecclesiales ), on the other hand, which have not preserved the valid episcopate and the original and complete reality of the Eucharistic mystery , are not churches in the proper sense ( sensu proprio Ecclesiae non sunt ); But those baptized in these communities are incorporated into Christ through baptism and are therefore in a certain, if not perfect, communion with the Church. "

Since the so-called “ecclesiastical communities” do not consider themselves deficient in their self-understanding, Dominus Iesus' language regulation was perceived as a degradation. “For the declaration, the churches of the Reformation are, so to speak, at the lowest level of the church hierarchy. ... With a clarity that leaves no room for doubt, the principle of dealing par cum pari, ie equal to the same, is rejected, ”said President Manfred Kock, President of the Council of the EKD.

His successor in office, Wolfgang Huber, gave a similar judgment . He recalled that less than a year before the appearance of the Dominus Iesus declaration, the joint declaration on the doctrine of justification had been signed, in which representatives of the Roman Catholic Church and the Lutheran Church announced a dialogue “as equal partners ( par cum pari )” . Nothing of this can be felt in the declaration.

In July 2007 the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith published the letter Responsa ad quaestiones de aliquibus sententiis ad doctrinam de ecclesia pertinentibus , in which the distinction between church and ecclesial community is affirmed:

"5. Question: Why do the texts of the Council and the subsequent Magisterium not ascribe the title 'Church' to the communities that emerged from the Reformation of the 16th century? Answer: Because, according to Catholic doctrine, these communities do not have apostolic succession in the sacrament of Holy Orders and therefore they lack an essential constitutive element of being a church. The ecclesiastical communities mentioned, which, mainly because of the lack of the sacramental priesthood, have not preserved the original and complete reality of the Eucharistic mystery, cannot, according to Catholic teaching, be called "churches" in the proper sense. "

literature

- Leonardo Boff: The Church as a sacrament on the horizon of world experience. Attempt to legitimize and lay the foundations of the Church on a structural and functional basis following the Second Vatican Council. (= Denominational and controversial theological studies , Volume 28) Bonifacius-Druckerei, Paderborn 1972, ISBN 3-87088-063-5 .

- Leonardo Boff: The Rediscovery of the Church. Base churches in Latin America. Grünenwald Verlag, Mainz 1980, ISBN 3-7867-0802-9 .

- Yves Congar: The Doctrine of the Church. From the occidental schism to the present. Freiburg-Basel-Vienna 1971.

- Gregor Maria Hoff : Thinking about faith at the moment. Volume 6: Ecclesiology . Paderborn 2011, ISBN 978-3-506-77315-9 .

- Walter Kasper: The Church of Jesus Christ. (= Collected writings. Writings on ecclesiology I., Volume 11) Freiburg-Basel-Vienna 2008.

- Walter Kasper: The Church and its Offices. (= Collected writings. Writings on ecclesiology II., Volume 12) Freiburg-Basel-Vienna 2009.

- Medard Kehl : Ecclesiology . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 3 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1995, Sp. 568-373 .

- Medard Kehl: The Church. A Catholic ecclesiology . 4th edition. Echter Verlag, Würzburg 1993, ISBN 3-429-01454-9 .

- Cornelius Keppeler, Justinus C. Pech (Ed.): Contemporary understanding of the church. Eight ecclesiological portraits (= series of publications by the Institute for Dogmatics and Fundamental Theology at the Philosophical-Theological College Benedict XVI. , Volume 4). Heiligenkreuz 2014.

- Hans Küng : The Church. Herder Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau 1967.

- Henri de Lubac: Corpus mysticum. Church and Eucharist in the Middle Ages; a historical study. Transferred by Hans Urs von Balthasar . Johannes, Freiburg / Einsiedeln 1995, ISBN 3-89411-161-5 .

- Helmut Merklein : The Ekklesia of God. Paul's concept of the church and in Jerusalem. In: Helmut Merklein: Studies on Jesus and Paulus I. (= WUNT 43), Tübingen 1987, pp. 296-318.

- Helmut Merklein: Origin and content of the Pauline idea of the body of Christ. In: Helmut Merklein: Studies on Jesus and Paulus I. (= WUNT 43), Tübingen 1987, pp. 319–344.

- Ralf Miggelbrink : Introduction to the Doctrine of the Church. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2003.

- Gerhard Ludwig Müller : The Church - the new covenant people of God (ecclesiology). In: Gerhard Ludwig Müller: Catholic dogmatics for the study and practice of theology. 8th edition, Herder Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau 2010, pp. 570–626.

- Peter Neuner : Churches and Church Communities . In: Münchener Theologische Zeitschrift 36 (1985), pp. 97-109.

- Peter Neuner: Ecclesiology. Doctrine of the Church. In: Wolfgang Beinert (ed.): Faith accesses. Textbook of Catholic Dogmatics. Volume 2. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn / Munich / Vienna / Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-506-70802-3 , pp. 399-578.

- Hugo Rahner : symbols of the church. The ecclesiology of the fathers. Müller Verlag, Salzburg 1964.

- Karl Rahner: Church and Sacraments. (= Quaestiones disputatae , Volume 10) Herder Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau 1960.

- Karl Rahner: Structural change in the church as a task and an opportunity. (= Herder Library, Volume 446) Herder Verlag, Freiburg im Breisgau 1972, ISBN 3-451-01946-9 .

- Joseph Ratzinger: The new people of God. Drafts on ecclesiology. Patmos Verlag, Düsseldorf 1984, ISBN 3-491-71001-4 .

- Joseph Ratzinger: Church - Signs among the Nations. Writings on ecclesiology and ecumenism. (= Gesamt-melte Schriften Volume 8, Teilband 8/1) Freiburg-Basel-Vienna 2010.

- Matthias Reményi , Saskia Wendel (ed.): The church as the body of Christ. Validity and limits of a controversial metaphor (= Quaestiones disputatae. Volume 288). Herder, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2017, ISBN 978-3-451-02288-3 .

- Walter Simonis : The Church of Christ. Ecclesiology. Patmos-Verlag, Düsseldorf 2005, ISBN 3-491-70384-0 .

- Jürgen Werbick : Church. An ecclesiological draft for study and practice. Herder Verlag, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 1994, ISBN 978-3-451-23493-4 .

- Siegfried Wiedenhofer : Ecclesiology. In: Theodor Schneider (Ed.): Handbuch der Dogmatik. Volume 2, 4th edition. Patmos Verlag, Düsseldorf 2009, ISBN 978-3-491-69024-0 , pp. 47-154.

Web links

Individual evidence

- ^ Medard Kehl: Ecclesiology. I. Concept and task. In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 3 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1995, Sp. 569 .

- ^ Peter Neuner: Ecclesiology. Doctrine of the Church. In: Wolfgang Beinert (ed.): Faith accesses. Textbook of Catholic Dogmatics. Volume 2. Paderborn a. a. 1995, pp. 399-578, here p. 402f.

- ^ Siegfried Wiedenhofer: Ecclesiology. In: Theodor Schneider (Ed.): Handbuch der Dogmatik. Volume 2, 4th edition. Patmos Verlag, Düsseldorf 2009, ISBN 978-3-491-69024-0 , pp. 47–154, here p. 91 and p. 52f.

- ↑ Walter Bauer : Greek-German dictionary on the writings of the New Testament and early Christian literature. 6th, completely revised edition, ed. by Kurt Aland and Barbara Aland. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1988, column 485.

- ^ Karl Kertelge: Church. I. New Testament . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 5 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1996, Sp. 1454 .

- ^ Herbert Frohnhofen: §8. The essential characteristics of the Church: unity, holiness, catholicity, apostolicity. (PDF) In: Theology scripts. Retrieved July 20, 2015 .

- ^ Norbert Brox: Church history of antiquity . 6th edition, Patmos, Düsseldorf 1998, p. 83.

- ^ Norbert Brox: Church history of antiquity . 6th edition, Patmos, Düsseldorf 1998, p. 85.

- ^ Norbert Brox: Church history of antiquity . 6th edition, Patmos, Düsseldorf 1998, p. 93.

- ^ Norbert Brox: Church history of antiquity . 6th edition, Patmos, Düsseldorf 1998, p. 94 f.

- ^ Norbert Brox: Church history of antiquity . 6th edition, Patmos, Düsseldorf 1998, p. 96.

- ^ Norbert Brox: Church history of antiquity . 6th edition, Patmos, Düsseldorf 1998, p. 98.

- ^ Norbert Brox: Church history of antiquity . 6th edition, Patmos, Düsseldorf 1998, p. 105.

- ^ Norbert Brox: Church history of antiquity . 6th edition, Patmos, Düsseldorf 1998, p. 109.

- ↑ Andreas Hoffmann : The Church - united, necessary for salvation, based on divine law. Basics of the understanding of the church with Cyprian of Carthage. In: Johannes Arnold , Rainer Berndt , Ralf MW Stammberger, Christine Feld (eds.): Fathers of the Church. Ecclesial thinking from the beginning to modern times. Festival ceremony for Hermann Josef Sieben SJ on his 70th birthday. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn / Munich / Vienna / Zurich 2004, ISBN 3-506-70423-0 . Pp. 365-388.

- ↑ Emilien Lamirande : Corpus permixtum. In: Augustinus Lexicon. Volume 2. Schwabe, Basel 1996-2002, Col. 21 f.

- ^ Siegfried Wiedenhofer: Ecclesiology. In: Theodor Schneider (Ed.): Handbuch der Dogmatik. Volume 2, 4th edition. Patmos Verlag, Düsseldorf 2009, ISBN 978-3-491-69024-0 , pp. 47–154, here p. 50.

- ^ Peter Neuner: Ecclesiology. Doctrine of the Church. In: Wolfgang Beinert (ed.): Faith accesses. Textbook of Catholic Dogmatics. Volume 2. Paderborn a. a. 1995, pp. 399-578, here p. 401.

- ^ Siegfried Wiedenhofer: Ecclesiology. In: Theodor Schneider (Ed.): Handbuch der Dogmatik. Volume 2, 4th edition. Patmos Verlag, Düsseldorf 2009, ISBN 978-3-491-69024-0 , pp. 47–154, here p. 134.

- ^ Leo XIII .: Circular Immortale Dei . In: Human and Community in Christian Vision . Freiburg (Switzerland) 1945, pp. 571–602, paragraph 852.

- ^ Peter Neuner: Ecclesiology. Doctrine of the Church. In: Wolfgang Beinert (ed.): Faith accesses. Textbook of Catholic Dogmatics. Volume 2. Paderborn a. a. 1995, pp. 399-578, here p. 509.

- ↑ Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Lumen Gentium No. 12.

- ^ Romano Guardini: From the sense of the church. Five lectures. 4th edition, Mainz 1955, p. 19 (first 1922).

- ^ Peter Neuner: Ecclesiology. Doctrine of the Church. In: Wolfgang Beinert (ed.): Faith accesses. Textbook of Catholic Dogmatics. Volume 2. Paderborn a. a. 1995, pp. 399-578, here pp. 518.509ff.

- ↑ Thomas Ruster : Mystici Corporis Christi . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 7 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1998, Sp. 593 .

- ↑ Ulrich Kühn: Church (= Handbuch Systematischer Theologie, 10). Gütersloher Verlagshaus, Gütersloh, ISBN 3-579-04925-9 , p. 173, fn. 30.

- ↑ Pope John Paul II : Apostolic Constitution Sacrae disciplinae leges of January 25, 1983 (online)

- ↑ See Lumen gentium 4f.

- ^ Medard Kehl: The Church. A Catholic ecclesiology. 3rd edition, Echter Verlag, Würzburg 1994, ISBN 3-429-01454-9 , pp. 270, 277f., With reference to Hans Waldenfels , Heinrich Fries and Wolfgang Trilling ; see. Ralf Miggelbrink: Introduction to the Doctrine of the Church. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2003, ISBN 3-534-16321-4 , pp. 21, 24.

- ^ Medard Kehl: The Church. A Catholic ecclesiology. 3rd edition, Echter Verlag, Würzburg 1994, ISBN 3-429-01454-9 , p. 288.

- ↑ Karl Rahner: Self-Execution of the Church: ecclesiological foundation of practical theology (= all works, volume 19). Benziger, 1995, p. 49.

- ^ Wilhelm Geerlings : The church from the side wound of Christ with Augustine. In: Johannes Arnold, Rainer Berndt, Ralf MW Stammberger, Christine Feld (eds.): Fathers of the Church. Ecclesial thinking from the beginning to modern times. Festival ceremony for Hermann Josef Sieben SJ on his 70th birthday. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn / Munich / Vienna / Zurich 2004, ISBN 3-506-70423-0 . Pp. 465-481, here p. 475.

- ↑ Ambrose of Milan (340–397): Lukas commentary (excluding the story of suffering) , 2nd book, No. 86 [1]

- ↑ Joseph Ratzinger: Eucharist - center of the church. Munich 1978, p. 21 f.

- ↑ Martin Luther: Disputatio de Fide infusa et acquisita . WA 6,86,5ff., Quoted in: Ralf Miggelbrink: Introduction to the teaching of the church. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2003, ISBN 3-534-16321-4 , p. 57, also for the whole.

- ↑ Lumen gentium (LG) 1; see. LG 9.48.59

- ^ Constitution Sacrosanctum Concilium on Sacred Liturgy No. 26; Cyprian of Carthage: Unitas ecclesiae 4.

- ^ Georg Tyrell: Christianity at the Crossroads. London 1907; German: Christianity at the crossroads. Munich - Basel 1959, p. 182. See: Peter Neuner: Ekklesiologie. Doctrine of the Church. In: Wolfgang Beinert (ed.): Faith accesses. Textbook of Catholic Dogmatics. Volume 2. Paderborn a. a. 1995, pp. 399-578, here p. 513.

- ↑ Ralf Miggelbrink: Introduction to the teaching of the church. Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 2003, ISBN 3-534-16321-4 , p. 58.

- ↑ Matthias Remenyi: From the Body of Christ ecclesiology for sacramental ecclesiology. Historical lines of development and hermeneutical problem overhangs. In: Matthias Remenyi, Saskia Wendel (ed.): The Church as the Body of Christ. Freiburg et al. 2017, pp. 32–72, here u. a. P. 41 (Rahner).

- ^ Siegfried Wiedenhofer: Ecclesiology. In: Theodor Schneider (Ed.): Handbuch der Dogmatik. Volume 2, 4th edition. Patmos Verlag, Düsseldorf 2009, ISBN 978-3-491-69024-0 , pp. 47–154, here p. 96.

- ^ Medard Kehl: The Church. A Catholic ecclesiology. 3rd edition, Echter Verlag, Würzburg 1994, ISBN 3-429-01454-9 , p. 83.134.

- ↑ Wolfgang Beinert: Office - Tradition - Obedience: Fields of tension in church life. Regensburg 1998, p. 116, quoted in: Nikolai Krokoch: Ekklesiologie und Palamismus. Dissertation, Munich 2004, p. 74 note 300 (digitized)

- ↑ Hans Küng: The Church. Freiburg im Breisgau 1967, p. 47, quoted in: Nikolai Krokoch: Ekklesiologie und Palamismus. Dissertation, Munich 2004, p. 83, note 347 (digitized)

- ↑ Enchiridion Symbolorum 860; Herbert Vorgrimler : Sacrament. III. Theology and dogma historical . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 8 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1999, Sp. 1442 .

- ↑ Cf. Veronika Prüller-Jagenteufel: Basic Executions of the Church. In: Maria Elisabeth Aigner , Anna Findl-Ludescher, Veronika Prüller-Jagenteufel: Basic concepts of pastoral theology (99 concrete words theology). Don Bosco Verlag, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-7698-1509-2 , p. 99f.

- ↑ Jürgen Roloff: The Church in the New Testament. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 1996, pp. 100-110, especially pp. 100f., 106, 109, 110, quotation p. 101.

- ↑ Thomas Söding : Body of Christ. I. Biblical-theological. 2. Deuteropaulins . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 6 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1997, Sp. 771 .

- ↑ Thomas Ruster : Mystici Corporis Christi . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 7 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 1998, Sp. 593 .

- ^ Peter Neuner: Ecclesiology. Doctrine of the Church. In: Wolfgang Beinert (ed.): Faith accesses. Textbook of Catholic Dogmatics. Volume 2. Paderborn a. a. 1995, pp. 399-578, here pp. 518f.

- ↑ Augustine: Civ. Dei, XVIII, 51, 2: PL 41, 614.

- ↑ Lumen gentium 32.

-

↑ Ralf Miggelbrink: Introduction to the teaching of the church. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2003, ISBN 3-534-16321-4 , pp. 35f.

Peter Neuner: Ecclesiology. Doctrine of the Church. In: Wolfgang Beinert (ed.): Faith accesses. Textbook of Catholic Dogmatics. Volume 2. Paderborn a. a. 1995, pp. 399-578, here p. 520. - ^ Peter Neuner: Ecclesiology. Doctrine of the Church. In: Wolfgang Beinert (ed.): Faith accesses. Textbook of Catholic Dogmatics. Volume 2. Paderborn a. a. 1995, pp. 399-578, here p. 461.521.524 (citation).

- ↑ Lumen gentium 8.

- ↑ Pope Paul VI. : Creed of the People of God (1968) No. 30.

- ^ Siegfried Wiedenhofer: Ecclesiology. In: Theodor Schneider (Ed.): Handbuch der Dogmatik. Volume 2, 4th edition. Patmos Verlag, Düsseldorf 2009, ISBN 978-3-491-69024-0 , pp. 47–154, here p. 134.

- ↑ Thomas Aquinas : Summa theologica III., Q. 73, loc. 3

- ^ Peter Neuner: Ecclesiology. Doctrine of the Church. In: Wolfgang Beinert (ed.): Faith accesses. Textbook of Catholic Dogmatics. Volume 2. Paderborn a. a. 1995, pp. 399-578, here p. 522f.

- ↑ Codex Iuris Canonici can. 519

- ↑ Lumen gentium No. 23.

- ↑ Lumen gentium No. 22.

- ↑ Lumen gentium No. 18.

- ^ Medard Kehl: The Church. A Catholic ecclesiology. 3rd edition, Echter Verlag, Würzburg 1994, ISBN 3-429-01454-9 , p. 244f.

- ^ Siegfried Wiedenhofer: Ecclesiology. In: Theodor Schneider (Ed.): Handbuch der Dogmatik. Volume 2, 4th edition. Patmos Verlag, Düsseldorf 2009, ISBN 978-3-491-69024-0 , pp. 47–154, here p. 90.

- ↑ Ralf Miggelbrink: Introduction to the teaching of the church. Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 2003, ISBN 3-534-16321-4 , p. 14f.

- ^ Siegfried Wiedenhofer: Ecclesiology. In: Theodor Schneider (Ed.): Handbuch der Dogmatik. Volume 2, 4th edition. Patmos Verlag, Düsseldorf 2009, ISBN 978-3-491-69024-0 , pp. 47–154, here p. 96.

-

^ Peter Neuner: Ecclesiology. Doctrine of the Church. In: Wolfgang Beinert (ed.): Faith accesses. Textbook of Catholic Dogmatics. Volume 2. Paderborn a. a. 1995, pp. 399-578, here p. 476.

Medard Kehl: Die Kirche. A Catholic ecclesiology. 3rd edition, Echter Verlag, Würzburg 1994, ISBN 3-429-01454-9 , p. 89. - ^ Peter Neuner: Ecclesiology. Doctrine of the Church. In: Wolfgang Beinert (ed.): Faith accesses. Textbook of Catholic Dogmatics. Volume 2. Paderborn a. a. 1995, pp. 399-578, here p. 476f.

- ^ Hugo Rahner : Mater Ecclesia - praise of the church from the first millennium . Einsiedeln, Cologne 1944.

- ^ Peter Neuner: Ecclesiology. Doctrine of the Church. In: Wolfgang Beinert (ed.): Faith accesses. Textbook of Catholic Dogmatics. Volume 2. Paderborn a. a. 1995, pp. 399-578, here pp. 507ff .; Bellarmine quote p. 508.

- ^ Keyword: Council decree "Unitatis redintegratio". In: kathisch.at. October 8, 2015, accessed September 13, 2019 .

- ^ Peter Neuner: Ecclesiology. Doctrine of the Church. In: Wolfgang Beinert (ed.): Faith accesses. Textbook of Catholic Dogmatics. Volume 2. Paderborn a. a. 1995, pp. 399-578, here pp. 507ff .; Bellarmine quote p. 524f.

- ^ Gerhard Feige: Unitatis redintegratio . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 10 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2001, Sp. 415 .

- ^ Peter Neuner: Ecclesiology. Doctrine of the Church. In: Wolfgang Beinert (ed.): Faith accesses. Textbook of Catholic Dogmatics. Volume 2. Paderborn a. a. 1995, pp. 399-578, here pp. 507ff .; Bellarmine quote p. 530.

- ↑ Unitatis redintegratio No. 3.

- ↑ Unitatis redintegratio No. 11.

- ^ Gerhard Feige: Unitatis redintegratio . In: Walter Kasper (Ed.): Lexicon for Theology and Church . 3. Edition. tape 10 . Herder, Freiburg im Breisgau 2001, Sp. 415 .

- ^ Peter Neuner: Ecclesiology. Doctrine of the Church. In: Wolfgang Beinert (ed.): Faith accesses. Textbook of Catholic Dogmatics. Volume 2. Paderborn a. a. 1995, pp. 399-578, here pp. 507ff .; Bellarmine quotation, p. 530, note 271.

- ^ Eva-Maria Faber: Calvinus catholicus , Göttingen 2012, p. 63ff.

- ^ Peter Neuner: Ecclesiology. Doctrine of the Church. In: Wolfgang Beinert (ed.): Faith accesses. Textbook of Catholic Dogmatics. Volume 2. Paderborn a. a. 1995, pp. 399-578, here pp. 507ff .; Bellarmine quote p. 530.

- ↑ Florian Ihsen: A church in the liturgy. On the ecclesiological relevance of the ecumenical community of worship. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2010, p. 75.

- ↑ Peter Neuner: Churches and Church Communities Münster 2001, pp. 196–211, here p. 208.

- ↑ Manfred Kock: Statement on the declaration “Dominus Iesus” published by the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith of the Roman Catholic Church. In: EKD. September 5, 2000, accessed June 9, 2019 .

- ↑ Wolfgang Huber: End or New Beginning of Ecumenism? . In: Michael J. Rainer (Ed.): "Dominus Iesus": offensive truth or offensive church? LIT Verlag Münster 2001, pp. 282–285, here p. 284.

- ↑ Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith: Answers to Questions on Some Aspects of Doctrine on the Church. In: vatican.va. June 29, 2007. Retrieved July 15, 2019 .