History of the city of Jülich

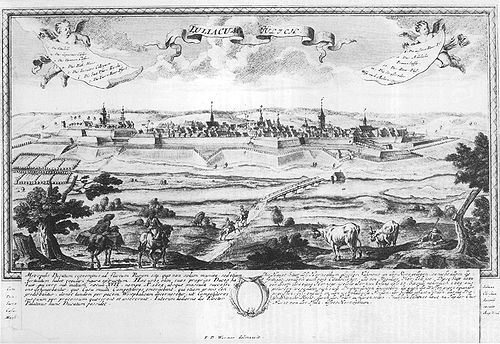

The history of the city of Jülich goes back to the beginning of Roman rule in Germania . The former vicus at a strategically important ford of the Rur , as one of the few settlements in the area, survived the turmoil of the migrations thanks to its fortifications built in late antiquity and developed into the center of first a county and then a duchy , which in the early modern period became too large Power and considerable influence came. With the extinction of the ruling house and the loss of the barely completed residence, the city became a mere fortress and garrison town. In the Second World War was Jülich completely devastated and the few remnants of the old time creating what is now modern city.

Prehistory and early history

The first traces of human settlement go back to the 9th millennium BC. BC, when migrating hunters and gatherers set up resting places in the area of Barmen . Ribbon ceramists and members of the Michelsberg culture created grave fields in what is now the city area.

Antiquity

Main article: Iuliacum

Today's city becomes historically tangible for the first time with the advance of the Romans into Germania, when it was around 50–30 BC. Took possession of the Rhineland and destroyed the native Eburones . Although no evidence of pre-Roman settlement has been found at the site of the Roman Iuliacum itself, a Celtic ring wall was discovered near Niederzier , which was destroyed in Caesar times and is possibly a predecessor of today's Jülich. In Augustan times the Roman road from Heerlen to Cologne was built , on which the vicus Iuliacum was built around the birth of Christ , which served as a rest area and road station. It has been speculated that the name may come from the mass granting of Roman citizenship to residents by the Julian emperors. However, the view is also held that the name is of pre-Roman origin: the name could be a Celtic-Germanic mixture of the words "ialo" (Celt.) And "lich" (Germ.), Both of which mean "clearing". The village was strategically located on a flood-proof high terrace near the Rur and one of the few passable crossings over the river at the time, which was also used by the Roman highway. There was probably already a bridge at that time near the point where the Rur Bridge is today. The settlement grew and its attractive location soon attracted craft businesses and traders, as evidenced by the discovery of a pottery settlement from the 2nd century in the area of today's Wilhelmstrasse. Apparently there were also some cult centers in the area, as the discovery of a Jupiter column suggests. The area around the village had numerous estates and was used intensively for agriculture.

When times became more restless with the onset of the mass migration , the Romans began to fortify the Rhine border and also the roads leading deeper into the empire with the construction of numerous forts. In the course of these measures, Iuliacum received a fourteen- tower fort of approximately round shape around 310 , which was located in the area around today's market square. The fort wall is indicated in the paving of the old town and also follows the southeastern foundations of the provost church . The trunk road ran around the fort in the north and roughly followed the course of today's Grünstrasse, Raderstrasse and Kapuzinerstrasse; in this area there was also an important settlement at the gates of the fortification. From the year 356 comes the tradition that troops of the emperor Julian had a battle with about six hundred Frankish warriors near Iuliacum. With the final retreat of the Romans around 460, Jülich came into the hands of the Franks , its stone fortifications and the favorable location on the Rur crossing ensured that the place was preserved, unlike most of the settlements in the area. In the period that followed, Jülich , which was part of the Franconian crown estate, gained in importance. The place was donated to the Archbishop of Cologne and became the seat of a count , at that time only a royal official. A local center of power was formed around the fort with the count's castle, which was first mentioned in a document from 849, from which the Jülich County emerged in the 9th century at the latest .

middle Ages

Early and High Middle Ages

The beginning of the Middle Ages found the village as the center of a small rule that was under the suzerainty of the Archdiocese of Cologne . In 881 there was a Norman invasion that destroyed the settlement. A document from 1081 names Gerhard I as the first hereditary Count of Jülich. The county experienced a slow but steady upswing, which is evident from the construction of a count's castle in the Altenburg district in the 12th century. It was laid out as a moth typical of the time on an artificial mound that is still clearly visible today. When Emperor Heinrich V moved to Cologne around 1114, the village was destroyed again. In 1147 Bernhard von Clairvaux preached in front of the church for participation in the crusade. The acquisition of extensive areas in the North Eifel with rich mining and the unsafe location of Jülich on the plain prompted Count Wilhelm II to move his residence to Nideggen Castle, which was less threatened as an almost impregnable hilltop castle . In 1214 Emperor Friedrich II conquered the place. In 1234, Count Wilhelm IV. Elevated Jülich to the rank of town, as such it was first mentioned in a document in 1238. A year later, the new city was exposed to a siege by the Cologne residents, as the Jülich counts tried to break away from the archbishop's sphere of influence. The settlement outside the walls was destroyed while the fortified fort withstood the attack. Around this time the moth Altenburg was destroyed. As early as 1278, the city was again besieged and destroyed by the Archbishop of Cologne, Siegfried von Westerburg , after Count Wilhelm IV was slain in an unfortunate attack on the imperial city of Aachen . At that time, the entire late Roman fort formed the count's castle, while the actual city, surrounded by palisades, lay in front of the northern walls in the area of today's Raderstrasse and Kapuzinerstrasse. In the course of the destruction of the city in 1278, the fort was apparently so badly damaged that rebuilding it did not seem worthwhile and instead a new fortification was considered. In 1288, the Count of Jülich and his allies succeeded in the battle of Worringen in breaking the power of the Archbishop of Cologne and gaining independence. In the course of this new freedom, a new stone city fortification was finally completed in Jülich at the turn of the 13th to the 14th century, which already enclosed a large part of today's old town. Relics of it still exist today: the witch's tower as the most obvious remnant and a piece of the city wall that is located within the building block of houses between Stiftsherrenstrasse and Großer Rurstrasse (backyard plots at Stiftsherrenstrasse No. 7 and 9, restricted access).

Rise to the duchy and development to the regional center of power

The power of the Jülich counts grew steadily, and as early as 1336 Count Wilhelm V was appointed margrave by Emperor Ludwig IV and elevated to the rank of imperial prince . The next step followed just twenty years later, when the margraviate became a duchy and Margrave Wilhelm became Duke Wilhelm I. A mayor and a council are documented for Jülich for the first time in 1360, around 1349 the existence of a Jewish community whose synagogue in Judenstrasse (today Grünstrasse / An der Synagoge) was confiscated that year in the course of the persecution of Jews in the Rhineland. The line of the dukes of Jülich died out around 1423 and the Berg family inherited its lands. In 1461 the Jews were expelled from Jülich, and the community was later reorganized at the old location. In 1473 there was a devastating epidemic in the city, and a year later a major fire followed, which among other things destroyed the entire city archive. In the same year, Duke Gerhard signed a contract with Charles the Bold , the great-grandfather of Emperor Charles V , in which he renounced all inheritance claims in the Duchy of Geldern forever . In 1521 the inherited house from the Mark already Dukes of Cleves and Counts of Mark gentlemen Lippstadt , the duchies of Jülich and Berg with the county Ravensberg . From this union the United Duchies emerged , to which the Duchy of Geldern and Ravenstein belonged for a while. The United Duchies thus became the strongest secular power in the region. In 1512 another major fire ravaged the city.

Modern times

William the Rich

In 1539 Duke Wilhelm V took over the rule of the United Duchies, which is known to posterity under the nickname "the rich" and which was to lead them to a final, glamorous climax. A year earlier, with the death of Karl von Egmond, the ruling house in the Duchy of Geldern had already died out, and Wilhelm sought to assert his inheritance claims, especially since the actual rule in Geldern had been exercised by Jülich-Klevian forces for a long time at the request of the estates. However, Emperor Charles V insisted that when the ruling house died out, the duchy would revert to the empire, and referred to the treaty of 1473. Wilhelm did not want to accept this as heir to the Jülich house, which was also extinct in the male line, so it came from 1542 to war . The Duke had wanted to secure French support by marrying a niece of the French king, but soon discovered that the French did not lift a finger to help him. Therefore, the Jülich-Klevischen forces soon succumbed to the imperial superiority, which conquered and destroyed all the ducal fortresses thanks to their superior artillery. Even a Jülich-Klevian victory at Sittard could not change that, and the duke had to throw himself shamefully at Charles V's feet. Jülich himself was handed over to the opponents without a fight. The emperor left him rulership over the inherited lands, but kept funds himself, in accordance with the Venlo Treaty . Furthermore, he operated the annulment of the Duke's French marriage, which was not consummated, and on top of that arranged for Wilhelm Maria von Habsburg to marry afterwards and thus connect with the House of Habsburg . Contrary to what was probably planned, however, when the House of Mark died out in 1609, Habsburg received nothing.

Expansion into the ideal residential town

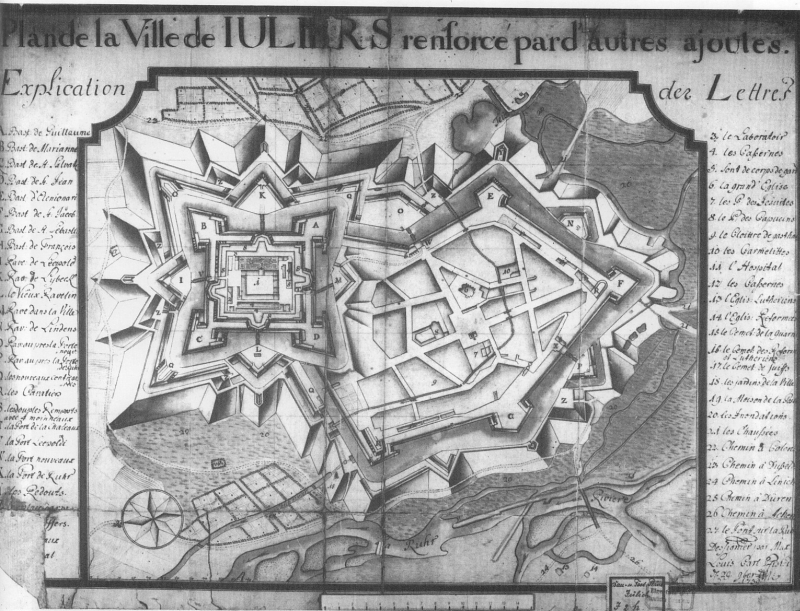

The Duke now set about strengthening his remaining areas and began developing three selected cities into state fortresses and also residential cities. This was possibly also in the interests of the imperial family, with which Wilhelm was now connected. Orsoy was designated as the main Klevian fortress, Düsseldorf as the state fortress and residence in Berg , while Jülich moved up to become the new residence and state fortress for the Duchy of Jülich after the destruction of Nideggen by the imperial troops . Already in 1538 the Jülichsche Landtag had decided to expand the city into a main fortress, but the work that had begun had not progressed very far because of the war and the imperial officials had destroyed the parts that had already been completed. Wilhelm pursued an ambitious plan in Jülich: the city was to become the ideal residential fortress in the style of the Renaissance. To this end, he looked around for an architect who could tackle this titanic task, and found Alessandro Pasqualini from Bologna , who had already made a name for himself with his work in the Netherlands. The Duke entrusted him with the office of state master builder and the supervision of the projects in the three state fortresses, and he also entrusted him with the reconstruction of Hambach Castle . The plans were soon ready and presented to the duke for assessment. The city was to be surrounded with a modern fortification in the bastionary system, the shape of an elongated pentagon was intended, oriented to the west, with bastions at three of the five corners. The other two corners as well as the entire north flank of the city were to be taken up by a huge square citadel , with four bastions, a double fortification and a residential palace in the center. The concept of the palazzo in fortezza , the ruler's palace in a fortification, which was much discussed at the time, but seldom executed, was thus implemented. The new construction of the city and the castle began around 1546, whereby the existing old buildings of the medieval city had to be taken into account. But already in the night of May 26th to 27th, 1547, a large fire destroyed almost the entire city except for a small part around the Hexenturm and the Kleine Rurstrasse. Now the way was clear for an ideal city based on contemporary ideas, which could be laid out regardless of previous development. In 1554, the Duke issued strict building regulations that stipulated, among other things, that all houses in the city had to be made of stone because of the fire hazard and had to be kept within certain limits so that the streets made a uniform impression. The new streets were spacious and fairly wide, but were partly based on the medieval street network. New roads were laid out in such a way that they could be viewed from the citadel or strategic points on the city wall, which made it easier to rule the city. In general, the streets were designed according to lines of sight, which facilitated communication across the buildings and thus control of the city and understanding between different positions in the event of a siege. The most important lines of sight connected the citadel and neuralgic points of the city fortifications so that messages could be exchanged quickly in an emergency. The width of the streets was calculated so that if a house collapsed, only half of the street would be blocked by the rubble, leaving enough space for a car to drive around the rubble. During this period of reconstruction, several unsuccessful attempts to make the Rur navigable were made.

Construction work

It turned out to be necessary to reduce the generous design plan due to lack of funds, but this probably only happened during the construction work. The citadel was significantly reduced in size and relocated, which disrupted the regular shape of the city and required the construction of an additional half-bastion in the northwest. The foundation stone for the ducal residential palace was laid on April 30, 1549. The east wing was ready for occupancy as early as 1553, the decorative facade of the north wing was completed around 1556, and the south wing followed around 1561. The fortifications required more time, around 1565 the Cologne Gate was completed, but it was not until 1580 that the work had progressed so far that the fortress was in a state ready for defense. Huge quantities of bricks were used, invoices that have survived show the delivery of a total of 27 million pieces between 1555 and 1568. The repopulation of the city after the great fire of 1547 was rather slow, among other things due to the high demands on the construction of the houses. which made the construction projects more expensive. The Duke ordered the abandonment of the town hall at its previous location in the northern part of the city; it was rebuilt from 1566 on the west side of the market square, roughly opposite the current location. Around 1570 there were still many vacant lots, the district south of today's Grosse Rurstrasse was almost empty. Within the city fortifications, there were still numerous remains of the old walls, around which areas of the southern part of the city up to the Aachener Tor were pronounced poor quarters. In 1572 the ducal particular school was founded, from which later the state grammar school and later the today's citadel grammar school was to emerge. From the year 1575 the number of 296 houses is given. In 1583 the Landdrost Werner von Gymnich decided for tactical reasons to demolish the town of Petternich, which was located directly in front of the northern front of the citadel between Ellebach and Rur and which would have enabled the attacker to nest near the fortress in the event of a siege. Some of the inhabitants were resettled in the city, some emigrated. The Petternicher Straße in the north quarter still reminds of the submerged place.

Fortress and garrison town

Main article: Jülich Fortress

Even after the fortifications and the residential palace were completed, the duke and his family rarely stayed in Jülich. One of the reasons for this was the continued armed conflict in the neighboring Netherlands , where the war of liberation raged against the Spaniards and as a result of which the security situation in the Duchy of Jülich remained tense. The privileged position of the city came to a definite end with the extinction of the ruling family in 1609, which also marked the end of the United Duchies.

The Jülich-Klevian succession dispute

The last Duke, Johann Wilhelm I , had died childless, and the heirs fought with the Emperor over the rich lands. The related events, which nine years before the outbreak of the Thirty Years' War almost led to an all-out war between the great powers of Europe, have gone down in history as the Jülich-Klevischer succession dispute . The Wittelsbach Electors of the Palatinate and the Hohenzollern Electorate of Brandenburg in particular made claims, while Emperor Rudolf II took the position that the duchies had reverted to the empire when the dukes died out. Imperial troops occupied Jülich, and a major European war between the imperial party and the supporters of the heirs seemed to be looming. In 1610, troops of the Dutch States General , reinforced by Brandenburg, English, Palatinate and French troops, besieged and conquered the city, which was then considered the strongest fortress in Europe, which had to give up after only 35 days - the defenders were poorly prepared and probably not at all seriously expected a siege. A major European war could just be averted once more, the new masters settled in the city and expanded the fortifications, a plan of division between Brandenburg and the Palatinate let Jülich fall into the hands of the Palatinate.

The Thirty-Year War

With the outbreak of the Thirty Years War , the city again became the focus of interest. The resurgence of fighting between the Dutch States General and Spain in the course of the Eighty Years' War marked the beginning of a new siege. Both sides had signed a twelve-year armistice in 1609, which expired that year. This immediately led to renewed hostilities, and the Spaniards immediately raised an army to invade the Netherlands from Jülich and Kleve. Little is known about the exact proportions, the number of fighters involved and their equipment, but the enclosure of the fortress began on September 5, 1621. The fortress was again cut off from the outside world by a ring of entrenchments, and the Spaniards intervened as before of the previous siege the citadel from the Merscher Höhe. The Dutch, trained in fortress warfare, offered tough resistance from the reinforced positions and repeatedly carried out attacks to disrupt the work of the besiegers. However, there was no prospect of relief, because the Spaniards blocked the Dutch army at Kleve, so that Prince Moritz of Orange could not send any help. The fierce fighting continued through the winter, cold, hunger and disease made the trapped as hard as the very intensified attacks by the Spaniards, and on February 3, 1622 the defenders finally had to surrender.

For the remainder of the war, the Spaniards occupied the fortress and carried out some renovations and extensions. Allegedly the Spaniards led a regiment of terror and were hated by the population. But they did not leave Jülich until 1660 and gave their property back to the Palatinate. The city grew very slowly, but in 1646 there were already 335 houses in the city.

The development up to the French era

The period following the departure of the Spaniards until the end of the 18th century was marked by stagnation. Jülich became a sleepy fortress and garrison town away from the events of that time. In 1678 the city was blocked by French troops in the Franco-Dutch War , but no serious attack took place. Around 1687 the Jesuits acquired the entire west side of the market square; later in the course of the 18th century they also gained considerable weight in the city through the influence of their general Goswin Nickel , who came from Jülich . A Reformed parish with its own church can be traced back to 1690, but the church was burned down by strangers as early as 1692. From 1693 the Palatinate and later the Bavarians carried out considerable extensions to the fortress, numerous new external works and a glacis were created. To employ the soldiers in the garrison in Jülich, apparently a regiment, large gardens were laid out around the city, especially along Römerstrasse and in the area of today's Probst-Bechte-Platz.

At the beginning of the 18th century, the Reformed community, which had its church outside the city walls, was exposed to reprisals from French troops passing through. The same happened to the Lutherans , who also had their church outside the ramparts. Only under the rule of Duke Karl Theodors did the Protestant citizens receive permission to move their church behind the city wall and in 1745 they built a new church on the site of today's Christ Church, right next to the city wall. In the years from 1738 to 1748, the (old) Rurkaserne (old) barracks, elongated structures along today's street Am Aachener Tor, were built and thus far away from any threats. During the Seven Years' War , French troops occupied the city from 1756 to 1762 with the permission of the Duke, then again from 1772 without permission, and only withdrew again in 1778. During this time (1756–1759) the Jesuit Church was built on the market square, and since 1756 dams have been built and maintained along the Rur for flood protection. In 1770 the old town hall was demolished and rebuilt in 1781 at the current location. Apart from that, there was little construction activity, hardly any houses were built or rebuilt, and only the establishment of monasteries brought some changes. In 1793, a first attempt by French revolutionary troops to take the city failed in the First Battle of Aldenhoven, with French and imperial troops facing each other on both sides of the Rur. Only a year later, after the Second Battle of Aldenhoven , did the city fall into the hands of the French on October 3, 1794 without a fight. This year the number of existing houses in the city should have been 341, only six more than almost 150 years earlier.

French time

In 1801 the Rhineland came to France in the Treaty of Lunéville , and the Duchy of Jülich was dissolved; the city came under the name Juliers as Mairie (mayor's office) to the newly formed Département de la Roer , Arrondissement de Cologne . The French closed all the monasteries and the grammar school and carried out considerable extensions of the fortifications, which were supposed to ensure that Jülich was used as a base for a large army and protect the important Rur crossing of the Heerstraße into France. The bridgehead was started in 1799 and completed around 1806. On September 11, 1804, Napoléon Bonaparte visited the city to find out about the progress of the work on the fortress, he laid the foundation stone for the unfinished forts on the Merscher Höhe. After the collapse of Prussia in 1806, however, the expansion plans were severely cut in favor of the expansion of Wesel, which fell to France . On November 7, 1811, Napoléon visited Jülich a second time with his wife. When the French withdrew from Germany after the lost Battle of the Nations near Leipzig , Jülich was besieged by Prussian, Swedish, Danish and Mecklenburg troops from January 17 to April 19, 1814 , the defenders capitulated on April 28 and left on May 4 the French Jülich. The landscape painter Johann Wilhelm Schirmer experienced the siege as a child and describes it in his memoirs.

Prussian time

On April 5, 1815, after the Congress of Vienna , Prussia officially took possession of the city, the following year the Jülich district was formed on April 24 , which first belonged to the Jülich-Kleve-Berg province and then, after its dissolution, to the Rhine province . The new masters completed the expansion of the fortress that the French had begun and used it as a bulwark against France, so the New Rur barracks were built between 1820 and 1822. For this reason, the city was not given a railway connection when the Cologne - Aachen - Belgium line was built, as there were fears that a possible besiegers could bring their material in this way, the line was instead led via Düren and was one of the first railways in the Rhine province opened in 1841. In 1859 the Prussian cabinet decided to demolish and loosen Jülich, the fortifications were outdated and no longer offered adequate protection from the new weapons of the approaching industrial age. This met with resolute resistance from the citizens, who owed a not inconsiderable part of their livelihood to the maintenance of the fortifications and the orders from the garrison, and the citizens submitted petitions to King Wilhelm asking for the fortress or at least the garrison to be retained. Jülich then remained a garrison town, and a non-commissioned officer school was set up, which took up quarters in the citadel. In September 1860 the Prussian army carried out a large siege exercise in Jülich, during which new artillery pieces and rifles as well as new methods of attack were tested. The citadel was damaged in the process, but it was preserved, while the outer works and the city fortifications were demolished in the following years.

Modern

Empire, Weimar Republic and the time of National Socialism

As a result, the city grew very slowly, the loss of the fortress had made it economically unattractive and the lack of a railway connection made itself felt. During the Franco-Prussian War there was a prison camp in the bridgehead, in 1873 the city got a railway connection with the lines Mönchengladbach - Jülich - Stolberg (- Aachen) and Jülich - Düren , built by the important Bergisch-Märkische Eisenbahngesellschaft ; In 1882 the (more local) Aachen-Jülich railway company extended its line Aachen North - Mariagrube via Aldenhoven to Jülich. A few years later, both companies were nationalized. At the end of the 19th century, the entry for the city of Jülich in Meyers Konversationslexikon (4th edition) was:

| “ Jülich , district town in Prussia. Administrative region Aachen, junction of the lines Munich-Gladbach-Stolberg and J.-Düren of the Prussian State Railway and the Aachen-Jülich Railway, has a Protestant and 2 Catholic. Churches, a district court, a Progymnasium, a NCO school, a sugar factory, paper pulp, cardboard and leather production and (1885) with garrison (1 Bat. Infantry No. 53 and 1 compartment. Field Artillery No. 23) 5234 mostly Catholic. Residents. The important fortifications that previously existed here were demolished in 1860. - J., the Juliacum der Alten, was conquered in 1277 by Archbishop Siegfried of Cologne, in 1609 by Archduke Leopold, in 1610 by the Dutch under Moritz von Orange, and in 1622 by the Spanish. In 1794 the French took it; In 1814 it was blocked, but maintained by the French until the Peace of Paris. " |

In 1902 a new Rur bridge was opened to traffic, which replaced the Napoleonic lock bridge, which had become too small , in 1910 today's Protestant Christ Church was inaugurated, in 1911 the new Aachener Landstrasse, which made its way through the bridgehead, and the state railway line Jülich - Linnich - Baal - Dalheim (which crosses the main line Aachen - Düsseldorf in Baal ); In 1912 the route of the district's own Jülich circular railway reached the city. That same year, branching off from the Mönchengladbach railway line was narrow gauge railway Ameln - Bedburg on standard gauge umgespurt and shortly after nationalized, so that now existed alongside the Düren line another connection to Cologne. The direct route to Cologne, which was often requested at the time, was never realized; the Jülich companies could only benefit (until the 1960s) from direct freight trains to Cologne (via Ameln).

During the First World War , the city was a stage and was used to train fresh troops, especially on the artillery bay north of the citadel. The Prussian state railways built from 1914-15 the designed 1,800 workers railway main workshop Jülich (later Reichsbahn repair shop - RAW), which in 1918 was put into operation and brought many new residents, who were settled in the schedule developed Südviertel (rear panel). After the end of the First World War , a workers 'and soldiers' council was also founded in Jülich on November 9, 1918 . What followed were withdrawals from the SPD and entries into the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). The period between 1918 and 1933 in Jülich was also shaped by mass unemployment (6 million unemployed) and the clashes between the parties of the Weimar Republic . In 1918, during the occupation of the Rhineland, Belgian and French troops moved into the city, which they did not leave again until 1929. In this year the expansion of the bridgehead to the Volkspark began. During the Weimar Republic, Jülich, like most cities and towns in the strictly Catholic Rhineland, was heavily influenced by the Center Party and did not tend particularly towards the National Socialists . The center also won comfortable majorities in the last election to the Reichstag .

After 1933 the city was assigned to the Cologne-Aachen district. In 1934 the bridgehead was converted into a Thingstätte or "National Consecration" with allegedly 20,000 seats, the casemates were used to grow mushrooms . On November 9, 1938, during the November pogroms (“Reichskristallnacht”), the Jülich synagogue in Grünstraße also burned down after it was set on fire by the National Socialists. It was completely destroyed in the Second World War and not rebuilt, the ruins were torn down after the war. The northern part of Grünstraße ( also called Judenstraße in the Middle Ages ), where it was located, is now called An der Synagoge . The Jewish cemetery on Aachener Strasse, which was used from 1816 to 1940, has been preserved; At the nearby Propst-Bechte-Platz, a memorial inaugurated in 2004 commemorates the kidnapped and murdered Jülich citizens who fell victim to the deportation of Jews from Germany during the Nazi era.

Annihilation in World War II

During the Second World War , the city was a transit station and stage in the French campaign, from 1940 the citadel was used by the Reich Labor Service , and German troops exercised on the artillery bay. The Rurbrücke received anti-aircraft guns to protect it at the bridgehead and on the city-side bank; parts of the concrete foundations could be seen long after the war. With the Allied invasion of Normandy and the withdrawal from France in 1944, Jülich himself moved into the front area, after the capture of Aachen in October 1944, the front slowly but surely came closer. The city was now in the fire area of enemy artillery and was also the target of bombing attacks because of the strategically important Rur Bridge to supply the front, the train station and the Reichsbahn repair shop, as well as the omnipresent Allied fighter-bombers , which dominated the hinterland of the German front during the day. Although the damage initially remained relatively minor, there were numerous dead and injured.

Several direct bombings in the forced labor camp of the Reichsbahn repair shop on the evening of September 29 killed hundreds of Russian and Ukrainian workers from the East. In the city chronicle there is talk of 120 to 400 dead, whose bodies were buried in the nearby forest. A memorial opposite the gate of the Army Restoration Plant still reminds of them. In this attack, the repair shop was so badly damaged that it was no longer operated and, as the city's largest employer, failed. On October 8, a bomb exploded in the hospital, killing more than a dozen young student nurses, their graves are in the cemetery of honor. With the progress of the heavy fighting and the intensification of the Allied aviation activity, the air and artillery attacks increased, the number of damage and casualties increased more and more. More and more citizens were evacuated from their homeland, and gradually more and more parts of the city sank into ruins.

Meanwhile, the Allied High Command was planning a devastating air strike against the German front. With it, the start should a major offensive against the Rurfront find their opener, which was to break the defensive positions west of the Roer and allow the advance to the Rhine. The company went down in history as Operation Queen , on November 16, 1944, several hundred British and American strategic bombers destroyed the cities of Düren , Jülich and Heinsberg in order to cut off supplies from the German front, and they also launched attacks against the front line itself. Jülich The attack hit particularly hard, as it was still shown as a fortress on American and French troop maps, and accordingly, as in Normandy, the Allies tried to devalue the assumed strong fortifications by completely destroying the city. The heavy bombardment and the conflagration that lasted several days almost completely destroyed the city, and since the ongoing major offensive was unable to break through the German front despite the oppressive superiority of the attackers, the city area remained in the range of the artillery on both sides for a long time. Most of the citizens had already left the city by this time, but there were still a number of civilian casualties, and many of the soldiers in Jülich perished. There are numbers of up to 4,000 dead as a result of the attack, including part of the 147th Artillery Regiment of the 47th People's Grenadier Division , which has just been unloaded at the station. The main battle line ran along the Rur for months, and the German Ardennes offensive and the heavy losses in the Huertgen Forest forced the Allies to suspend their offensive for the time being. Even after the failure of the Battle of the Bulge and the American attack along the Rurfront of 10 February 1945, it would take almost two weeks until they finally managed the transition across the river, as the Germans the floodgates of Rurtalsperre opened and the Rurtal following through Flood made impassable. Continuous artillery fire, further bombing attacks and bitter house-to-house fighting in the spring of 1945 contributed to the fact that the city looked like a deserted desert when it was finally taken by the Americans on February 23rd - hardly a person was left behind in the plowed ruins. Only in Römerstrasse and Linnicher Strasse had a row of houses been preserved here and there, the fortifications had most likely withstood the devastation, but the city was 98% destroyed and thus one of the worst-damaged cities of the entire war, if not even the worst damaged ever. In total, the city was in the combat zone for 155 days.

research

After the war, there were considerations of leaving the city as a memorial and rebuilding it elsewhere. So complete was the destruction that people seriously considered not trying to rebuild it. Conditions in the ruins were impossible, which the British publisher and journalist Victor Gollancz impressively documented in an illustrated report entitled In darkest Germany . It triggered a wave of helpfulness in Great Britain , which not only helped alleviate the fate of the residents of Jülich, a street in Jülich is now named after Gollancz out of gratitude. After the dissolution of Prussia, the city came to the newly founded state of North Rhine-Westphalia . The clearing of rubble was hard work, but the old town was rebuilt on the ruins according to the old ideal city plan. The architect R. Schöffer contributed to this by drawing up the first construction plan in 1947. Of the historical buildings in the city center, practically only the lower floors of the tower of the provost church and the witch tower survived, otherwise the once picturesque old town was completely destroyed. It was rebuilt in the style of the 1950s on the old floor plan, but the old beauty was gone.

The fortifications were provisionally secured from 1954, but otherwise sank into a long slumber and were deliberately ignored by the population and the city administration.

The paper and sugar industry was able to recover from the war damage, and in the 1950s the city sought connection to promising technologies. The Jülich Shortwave Center was established in 1956, and in the same year the city saw the establishment of the Atomic Research Center, today's research center , which was known from 1960 to 1990 as the Jülich Nuclear Research Center (KFA). In their wake, the Uranit company (now Urenco Germany or ETC ) also established the nuclear industry in Jülich. Again, numerous immigrants came, especially academics, who found their livelihood in the research center and mostly took up residence in the new north quarter around the former artillery bay. In the spirit of modernization, a new bus station went into operation in 1963 at the Hexenturm, far from the train station , and an engineering school was built in 1970.

From 1964 serious security measures were carried out in the citadel, which unfortunately a large part of the historic buildings fell victim to. In the same year, the Federal Railroad Repair Works was closed and the Bundeswehr took over large parts of the area as Army Repair Works 800. On November 4, 1976, a training workshop for 72 young people was opened there.

In 1968, construction began on the citadel, which was to make it the headquarters of the state high school , and in 1972, exactly 400 years after it was founded, the school was able to move into the new building. On January 1, 1972, the Jülich district was dissolved in the course of local government reform and largely merged with the Düren district . Several surrounding villages were incorporated into Jülich and the population rose to over 30,000. Also contributed to the resettlement as a result of the progression of the surrounding open-cast mines of Rheinbraun in which Jülich with the relocation site Lich Steinstraß 1981 bestowed a new suburb in the northeast on Merscher height.

In the 1970s, extensive restoration work began on the citadel and, sporadically, on the bridgehead, which were continued in the 1980s and 1990s, initially tentatively and with little consideration, then with increasing determination and quality. A major rethinking set in: if the old fortifications used to be nothing more than a brick, they were increasingly viewed as treasure to be guarded from, from which capital could be made in many ways. This change in awareness was not least the work of fortress researcher Hartwig Neumann , who tirelessly fought for “his” fortress.

From 1985 the citadel was finally a listed building, from 1986 the historic city center was renovated. This development reached its preliminary climax in the State Garden Show in 1998, the focus of which was above all the bridgehead, which was restored to a high quality and adorned with an elaborate garden.

On May 25, 2009, the city received the title “ Place of Diversity ” awarded by the federal government .

Historical city map

Legend:

|

|

See also

- Jülich

- Iuliacum

- Citadel Jülich

- Jülich bridgehead

- Jülich Fortress

- Duchy of Jülich

- Witches Tower Jülich

- Jülich-Kleve-Berg

literature

- Hartwig Neumann : Citadel Jülich: Great art and building guide . Publishing house Jos. Fischer (Jülich), 1986, ISBN 3-87227-015-X .

- Hartwig Neumann: City and fortress Jülich on pictorial representations , Bonn 1991, ISBN 3-7637-5863-1 .

- Hartwig Neumann: The Jülich Citadel: a walk through history . Publishing house Jos. Fischer (Jülich), 1971.

- Hartwig Neumann: The Jülich bridgehead . Publishing house Jos. Fischer (Jülich) 1973.

- Helmut Scheuer: How was that back then? Jülich 1944–1948 . Verlag des Jülich history association 1985, ISBN 3-9800914-4-9 .

- Eisenbahn-Amateur-Klub Jülich eV (Ed.): Jülich, the old railway town , 2nd edition, Jülich, 1986

- Ulrich Coenen: From Juliacum to Jülich . Verlag G. Mainz, Aachen 1988, ISBN 3-925714-17-0 .

- Guido von Büren and Erwin Fuchs (eds.): Jülich: City - Territory - History . Boss Druck und Medien Kleve, 2000, ISBN 3-933969-10-7 .

Web links

- Jülich timeline

- Jülich history association

- Website of the city of Jülich

- Citadel Museum

- Entry in the digitized Meyers Konversationslexikon

Individual evidence

- ↑ Günter Bers: Jülich history sheets - year book of the Jülich history association No. 41, 1974, The Jülich workers and soldiers council in November 1918, pp. 1–31

- ^ Federal Statistical Office (ed.): Historical municipality directory for the Federal Republic of Germany. Name, border and key number changes in municipalities, counties and administrative districts from May 27, 1970 to December 31, 1982 . W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart / Mainz 1983, ISBN 3-17-003263-1 , p. 308 .