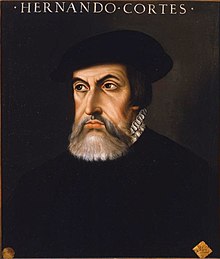

Hernán Cortés

Hernán Cortés de Monroy y Pizarro Altamirano (Marqués del Valle de Oaxaca) - the first name is sometimes given with Hernando or Fernando , the surname is also reproduced with Cortez - (* 1485 in Medellín ; † December 2, 1547 in Castilleja de la Cuesta ) a Spanish conquistador . With the help of his Indian allies, he conquered the Aztec Empire and its capital Tenochtitlan . Hernán Cortés was Governor General of New Spain from 1521 to 1530.

Life

Career until 1518

Cortés came from the lower Spanish nobility ( Hidalgo ). He was distantly related through his mother to Francisco Pizarro , the conqueror of Peru . His family was not wealthy. Cortés studied law at the University of Salamanca at the age of 14 . After two years he dropped out and returned to Medellín. Two years in Salamanca and his later experience as a notary brought him closer to the Castilian legal system. He then entered military service and embarked in 1504 for the West Indies , where he worked for a relative, the governor of Hispaniola , Nicolás de Ovando .

In 1511 he accompanied the governor Don Diego Velázquez to Cuba and, because of his ability, became his secretary when he became governor of Cuba. Cortés had his patron Velázquez in Cuba allot a repartimiento in Cuavanacan on the Río Duaba. There he let the resident Taínos look for gold and acquired a considerable fortune. He also worked as a notary, making money raising cattle and calculating the royal share of Cuban gold production. Other colonists did not take him seriously, as he had not yet distinguished himself by any conquest. When the governor Diego Velázquez moved the capital of Cuba from Baracoa to Santiago in 1515 , Cortés accompanied him and, as Alcalde, became the city's commander-in-chief and justice of the peace. Nevertheless, he kept having differences with the governor. For a short time Velázquez even had his secretary thrown in jail because he did not want to marry Catalina Suárez, whom he had promised to marry. Cortés escaped from prison but was captured again. Eventually, under pressure from Governor Catalina, he married and reconciled with him and his wife's family. The marriage remained childless.

Conquest of Mexico

Expedition commander

Velázquez tried twice to expand his sphere of influence and sent expeditions to the unknown coast of Central America under Francisco Hernández de Córdoba and Juan de Grijalva . This is how he learned about the country's gold wealth. So he equipped a third expedition and deployed Cortés as commander. But friends warned Velázquez against the ambition of Hernán Cortés. So he withdrew his order, but Cortés had already recruited men and bought ships in other Cuban ports. With the flotilla of 11 ships, in addition to the flagship of the conquistador named Santa Maria de la Concepción, three other caravels and seven smaller brigantines as well as a crew of 670 men, mostly young men from Spain, Genoa , Naples , Portugal and France, he sailed on February 18, 1519 from Havana to the newly discovered coast.

On the island of Cozumel it was possible to free the Spaniard Gerónimo de Aguilar from the hands of the Maya . He had been stranded on the coast eight years earlier and had lived as a slave with the Maya and learned their language . Cortés circled the eastern tip of the Yucatán , sailed north along the coast and into the Tabasco River . When he wanted to go ashore near the city of Potonchán to take drinking water, the Maya refused to allow the landing. So the Spaniards took the city by force. This is what the Maya Cortés and the King of Spain surrendered and agreed to toll to pay. On March 15, 1519, Tabscoob , the highest-ranking Mayan prince in Potonchán, handed 20 slaves to Cortés. One of these slaves, Malinche , called Doña Marina by the Spaniards, served as an interpreter together with Gerónimo de Aguilar and became his most important advisor, later also the lover and mother of his first son, Martín (born probably 1523).

Landing and colony establishment

Cortés continued his voyage in a north-westerly direction and landed on April 21, 1519 at San Juan de Ulúa . Moctezuma learned of the landing of the Spaniards and sent them a delegation of his closest confidants. He gave them gifts made of gold and precious stones, clothes and splendid headdresses. Never before have unknown visitors received so many and valuable gifts. However , Moctezuma refused Cortés' request to visit him in Tenochtitlán . With his generous gold gifts he wanted to appease the strangers and get them to leave the country, but did the opposite. It was now clear to Cortés that this country was not poor, but very rich.

In order to gain independence from the governor in Cuba, Cortés founded an independent colony modeled on the Spanish corporations in the name of the king and under royal authority . He gave it the name Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz ( Veracruz ) and sent the Spanish King Charles I (Spanish: Carlos I, later as Charles V also Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation) a letter of justification with the gifts of the Aztecs . He had the ships destroyed after sails, anchors, compasses and all other moving parts had been brought ashore. So he consciously took the opportunity to return to himself and his people. With the destruction of his ships, Cortés put everything on one card. He defied Velázquez's orders and went into debt for the company. If he had failed, he would have been brought to Spain in chains as a traitor or immediately tried in Cuba. Only with success could he defend himself against Velázquez, satisfy his creditors and appear as a hero before the king.

In Veracruz, Cortés left a small force under the command of Juan de Escalante . Most of these men were too old for the upcoming march to Tenochtitlán, sick, or wounded in the first skirmishes in Tabasco and not yet recovered.

Cortés received important information about the country and its people, as well as an invitation to Cempoala , from the Totonaks' "Fat Kaziken " . The Totonaks had been subjugated by the Aztecs a few years earlier. The Indians complained to him about Moctezuma and the overwhelming burden of tribute payments . The Kazike gave the conquistador a deep insight into the political situation in the country. Through his interpreter, Malinche, Cortés learned that the Aztec Empire had no clearly defined national territory. There was no uniform language, although Nahuatl was understood almost everywhere, no uniform administration, no uniform legal system and no standing army. Only the enormous military might of the Aztecs held the multi-ethnic state together. Since the army was only set up for military campaigns, there was almost no military security for the empire. If the Aztecs had subjugated a people, the caciks had to pay tribute to the rulers in Tenochtitlán in the form of precious metals, handicrafts, food and also people. These were enslaved by the Aztecs or sacrificed to the gods on altars. If the tribute demands were not met, this triggered another campaign. So with each victory of the Aztecs, the number of their enemies increased.

The Totonaks hoped for their freedom from Cortés and asked him for military assistance against the Aztecs. Cortés promised to protect them from the Aztecs, and led the caciques to take the bystanders Aztec tribute collectors caught. He urged the Totonaks to renounce their forced alliance with the Aztecs. He secretly helped the tribute collectors to escape in order to use them as messengers for his messages to Moctezuma. They reported to their ruler that Cortés wanted to be his friend and ally. Cortés, on the other hand, promised the Totonaks protection and weapons aid in the event of an attack by the Aztecs. The Totonaks also reported to Cortés of the deep hostility of the Tlaxcaltecs to the Aztecs. They had opposed the Aztecs for many years and paid no tribute. Although the Tlaxcalteks only owned a small enclave in the vast Aztec empire and were limited to a manageable area, they had shown their fighting ability in many battles. Cortés intended to enter into an alliance with this people.

March to Tenochtitlán

On August 16, 1519, Cortés set out with around 300 soldiers, including horsemen, crossbowmen and arquebusmen . In addition, the entourage had several cannons and was accompanied by several thousand Totonaks who, in addition to warriors, also provided porters for the transport of heavy weapons.

That accompaniment was probably the reason why the Tlaxcalteks did not hear the negotiators that Cortés sent them. Not only had the Aztecs waged war against Tlaxcala, but they also imposed a comprehensive trade embargo on the country that even included salt. Now the foreign Spaniards had entered their country together with the Totonaks. The Totonaks were subjugated and forced allies of the Aztecs. From this the Tlaxcalteks concluded that the Spaniards were in league with the Aztecs. They captured the Totonak negotiators and attacked Cortés with great odds. However, since the Tlaxcalteks did not manage to defeat the Spaniards even after several battles, they finally started negotiations with the strangers. They allied with Cortés and formed an alliance. The hatred of the Aztecs made the Tlaxcalteks his most valuable and loyal allies. The Tlaxcalteks and the other indigenous people always addressed Cortés as "Lord of Malinche", the name of his interpreter Malinche, who never left his side.

Reinforced by 2000 men from Tlaxcala, Cortés came to Cholula , a rich city that had been subjected to the Aztecs shortly before and was regarded as a shrine of gods. While there wasn't even salt in Tlaxcala, there was an abundance of food and goods of all kinds.

Today it is no longer possible to say exactly what happened in Cholula. According to later information from Bernal Díaz, Malinche is said to have played to the wife of a cacique from Cholula that she was being held against her will by the Spaniards who, in order to save her, told her about the planned attack by the townspeople on the Spaniards. Two Cholultek priests had also warned Cortés about an attack. The Spaniards are also said to have discovered that barricades had been erected in the streets. In his letters to Karl, Cortés speaks of a hidden Aztec army of 50,000 men. Bernal Díaz also speaks of an Aztec army lurking in front of the city. The Mexican historian Manuel Orozco y Berra (1816–1881), on the other hand, put forward the thesis that the massacre was the result of an intrigue by the Tlaxcaltecs, who wanted to take revenge on the Cholultecs who were enemies with them and wanted to prove their loyalty to the Spaniards. To this end, they spread the rumor of the ambush about Malinche.

With a pre-emptive strike , the Spaniards attacked in the morning and killed many residents. The Tlaxcalteks took revenge on their old enemies and marched through the rich city, fighting and plundering. More troops from Tlaxcala rushed in. Cortés found it difficult to stop them. With his alliance with the Tlaxcalteks and the subjugation of Cholula, Cortés had shown the Aztecs that he was a new power factor in their empire that should not be underestimated. Moctezuma was still trying to keep him away from his capital. But the more Cortés learned about Tenochtitlán, the more willing he was to visit this city.

When the Spaniards had overcome the last pass in the mountains, they saw Lake Texcoco and the many densely populated cities on its banks. Tenochtitlán was the largest of these cities and was in the middle of the lake. Several causeways connected it to the mainland.

In the capital of the Aztecs and Moctezuma's capture

Moctezuma received Cortés on November 8, 1519 at the gates of the capital and had the Spanish assign the palace of his late father Axayacatl as an apartment. This palace was so big that there was room for all Spaniards with their horses and cannons.

At the beginning of their stay in Tenochtitlán, the Spaniards were very courted. It is widely stated that this was due to the fact that the Aztecs identified Cortés with the god Quetzalcoatl , whose return an old prophecy announced. According to a speech handed down by Bernardino de Sahagún , Moctezuma is said to have formally handed over his rule to Cortés when they first met. In recent research this is interpreted as a historical myth with which Cortés and his people wanted to justify their illegal actions against King Charles.

Accompanied by high dignitaries, the Spaniards traveled and explored the country. Of particular interest to Cortés were the country's ports and gold mines. At Cortés' request, Moctezuma showed him and his entourage the inside of a temple. In a room, the walls of which were encrusted with blood, the Spaniards found three human hearts that were being burned in a brazier. In the sacrificial cult of the Aztecs , human sacrifice was a sacred act and an act of worshiping gods . The Spaniards, and especially Hernán Cortés, felt deeply offended in their religious sentiments. For them the religion of the indigenous people meant blasphemy . When Cortés approached the Tlatoani and wanted to overthrow the Aztec statues of gods and replace them with the Christian cross and images of the Virgin , a dispute broke out. The conquistadors set up a small church in the palace assigned to them and discovered the treasury of Axayacatl behind a wall. The growing tension with the Aztecs made the Spaniards realize how vulnerable they were. Cortés received news that the Aztecs had attacked the small garrison in Veracruz under Juan de Escalante . Six men were dead and Escalante badly wounded; he died three days after the battle. The soldier Arguello was captured alive. Now the Spaniards in the Aztec capital were in mortal danger.

After the battle of Veracruz, the Aztec commander sent the severed head of the captured Spaniard Arguello to his tlatoani in Tenochtitlán. Cortés confronted Moctezuma and the Spaniards threatened him with accompanying them to their quarters. They told him that from now on he would be their prisoner. The humiliated prince continued to rule in name, but in reality Cortés was his ruler from then on.

He had the Aztec captains who had fought against Juan de Escalante and his men brought before and interrogated. After confessing that they were acting on Moctezuma's orders, they were sentenced and publicly burned. Cortés forced Moctezuma to watch the execution of the sentence. News of the death of the Aztec captains quickly spread across the country. This restored the reputation of the Spaniards among the Totonaks in Cempoala.

Cortés sent Spaniards to the provinces to examine them for wealth and replaced unpopular officials. He finally got Moctezuma so far that he formally recognized the supremacy of King Charles V and promised to pay an annual tribute. Despite all the tensions, Moctezuma tried to get along amicably with the Spaniards while in captivity. So he gave Cortés Tecuichpoch , his favorite daughter, to wife. Although Cortés was already married, he did not reject the daughter of the Aztec ruler and promised to treat her well. Another daughter of Moctezuma ( Leonor Moctezuma ) was married to Juan Paez, a Spanish officer.

Fight against Pánfilo de Narváez

The Spanish governor of Cuba, Diego Velazquez, had meanwhile sent a fleet of 18 ships with 1200 men, 12 cannons and 60 horses under the command of the Pánfilo de Narváez to capture Cortés and his officers and to complete the conquest of New Spain. Cortés left 150 men under Pedro de Alvarado in Tenochtitlán and marched to the coast on May 20, 1520 with the remaining 250 men. He attacked Narváez and his people, who had meanwhile withdrawn to the city of Cempoala , and took Narváez prisoner. With gold and promises, Cortés convinced most of the Narváez's men to join him. So he made his way back to Tenochtitlán with an army of over 1200 men and almost 100 horses.

Cortés also took over the entourage of Pánfilo de Narváez, which consisted of at least 20 Spaniards, many locals, African slaves as well as mulattos and mestizos from the Caribbean islands, including women and children. Since Cortés did not want to lose any time, he finally hurried ahead with most of the soldiers and let the slow entourage follow suit. After the column had covered most of the route to Tenochtitlán, warriors from Texcoco attacked the inadequately protected entourage and brought the approximately 550 prisoners to Zultepec . There the prisoners were sacrificed to the gods over the next seven months. Archaeological research in the ruins of Zultepec has shown that the sacrifices were associated with ritual cannibalism .

Still sadness and battle of Otumba

When Cortés and his soldiers arrived in Tenochtitlan, an uprising against the Spaniards had broken out because Pedro de Alvarado had massacred the participants in the Aztec Spring Festival. After an attack by the Aztec warriors on the Spanish palace, Moctezuma was wounded by angry Aztecs when he tried to call his people to peace. He succumbed to his injuries after refusing to have his wounds tended. Since he died in the palace of the Spaniards, this is only documented by Spanish sources. It was later also claimed that the Spaniards got rid of the Aztec king because he was no longer of any use to them. The Aztecs chose Moctezuma's brother Cuitláuac as the new ruler of the empire.

Cortés tried to flee Tenochtitlán with his army on the night of June 30th to July 1st, 1520. The attempt to escape undetected from the city failed, however, and the Spaniards were attacked by thousands of Aztec warriors. Heavily loaded and shot at from all sides, they had to fight their way over the partially destroyed dams. Only 425 soldiers and 24 horses survived the escape. Cortés, who had already reached the other bank, hurried back with some of his captains to assist the beleaguered rearguard. He lost the index finger of his left hand in this fight. It was on that night, known as Noche Triste (Sad Night), that Cortés suffered the greatest loss of men, weapons and especially gold.

Hernán Cortés tried to withdraw to Tlaxcala with his remaining troops . But on July 14, 1520 he was overtaken and caught by an Aztec army on a plain in front of Otumba. The Aztecs intended to destroy the Spaniards once and for all. However, they underestimated the fighting power of the Spanish cavalry . So far they had only seen the riders with their horses on the cobbled streets in Tenochtitlán or on the run over the torn up dams in the Noche Triste. Facing these cavalry in open battle on a grassy plain was new to her. The Spaniards, on the other hand, had already passed many such situations victoriously. Cortés recognized the Aztec commander by his elaborate feather headdress and his feather standard. Accompanied by a few horsemen, he stormed into the midst of the Aztecs. Juan de Salamanca rode down the Aztec commander, killed him, picked up the feather standard and handed it to Cortés. Although the Spaniards suffered heavy losses in this battle, the Aztecs withdrew after the death of their leader.

When Cortés finally reached Tlaxcala five days after his escape from Tenochtitlán, his loss of people and material was enormous. Some Spanish women who had come to the country with Pánfilo de Narváez had also died, while Doña Marina and Doña Luisa, a daughter of Xicoténcatl the elder , survived, as did the two daughters Moctezumas and María de Estrada , the only Spanish woman in arms and armor. She was the wife of a conquistador and had fought with the men throughout the campaign.

The Tlaxcalteks proved to be loyal allies in this situation, offering care and shelter to the defeated and exhausted Spaniards.

Alliances

Despite his defeat in Tenochtitlán, Cortés did not give up. He reorganized his troops and launched a campaign of conquest around Lake Texcoco and built new alliances . His most important allies, the Tlaxcalteks, remained loyal to him even after the defeat in Tenochtitlán, although the Aztecs wanted to pull them to their side and promised them peace and prosperity. Together, the Spaniards and the Tlaxcalteks defeated the Aztec occupation in Tepaeca and cut the city from its alliance with the Aztecs. Meanwhile raged a smallpox - epidemic in Tenochtitlan and soon grabbed onto the country over. A Spanish slave who had arrived with the troops from Pánfilo de Narváez had brought the disease. Moctezuma's successor, Cuitláhuac, died after only eighty days of reign. Although the disease drastically reduced the number of fighters on both sides, the consequences for the Aztecs were more devastating than for the Spaniards. After the death of their ruler, the Aztecs elected Cuauhtémoc , the son of King Ahuitzotl , to the throne in February 1521 . Cuauhtémoc, the new ruler of the Aztecs, sent messengers and warriors to the neighboring peoples and tried to bind them with promises, threats and punitive expeditions. But the Aztec empire was not a homogeneous entity. Many peoples had had enough of the Aztec supremacy and did not take part in the struggle against the Spaniards without, however, immediately taking sides against the Aztecs for fear of being punished by the Aztec army.

Within a few months, Cortés and his troops defeated several city-states such as Chimalhuacán , Oaxtepec , Yautepec , Cuernavaca and Tlacopan around Lake Texcoco, while others joined him voluntarily. Many peoples whom Cortés met during his campaign of conquest felt oppressed by the Aztecs. They were not an integral part of the empire, but were exploited by the Aztecs after their submission. Tepeyacac , Cuernavaca and the cities of Huejotzingo , Atlixco , Metztitlán and Chalco joined him as new allies . If he didn't want a ruler, Cortés quickly replaced him with a man he could use as a puppet. When the Tlatoani of Chalco died of smallpox, he recommended his people on their deathbed to submit to the Spaniards and sent his sons to Cortés instead of Cuauhtémoc, the Aztec ruler. He placed his succession and rule over the associated localities in the hands of Cortés. He received the princes benevolently and confirmed them in their office. More and more cities recognized the conquistador as the supreme ruler. Through his clever alliance policy and military successes over the Aztecs, he took the position that Moctezuma had previously occupied. Also Texcoco , one of the largest cities of the empire and a member of the Triple Alliance could take the Spaniards and pull to their side. Cortés took advantage of the disputes between the Indians for rule over the city and put Ixtlilxochitl , the son of Nezahualpilli on the throne.

Siege and fall of Tenochtitlán

In Tlaxcala, Martín López, the shipbuilder, had built thirteen brigantines . Several thousand Tlaxcaltec warriors carried the individual parts of the ships to Lake Texcoco under the protection of Gonzalo de Sandoval and his men. The ships were assembled and launched in the city of Texcoco, the last on April 28, 1521. After just a few days, the smallest ship was decommissioned because it could not hold its own against the Aztec war canoes.

The ships formed the first ring of sieges around the Aztec capital. In the beginning, Cortés himself took command. The troops under Alvarado and Olid marched towards Chapultepec and destroyed an aqueduct there . In doing so, they interrupted the water supply to Tenochtitlán. With his brigantines, Cortés largely prevented the capital from being supplied with its inedible salt water via Lake Texcoco. Few canoes got through under cover of night. At the beginning of the fight, the Aztecs rammed stakes into the lake bed with the tips just below the surface of the water. They wanted to stop the brigantines so that they could attack them with their canoes . But the Spaniards sailed over these piles with full sails without being damaged.

The Aztecs tried to defend the city already on the dams in the lake. They tore up some places and built jumps in other places. Day after day the Spaniards attacked and were attacked by the Aztecs with canoes from the lake. With the help of their ships, the Spaniards fought their way free, reached the city and gained ground. As they retired to their positions in the evening, the Aztecs again occupied their old positions in the city that night. Cortés therefore ordered the captured houses to be torn down. So the Spaniards slowly advanced towards the city center. Cuauhtémoc organized a large-scale attack on Alvarado and the troops in Tlacopan. But the Aztecs were repulsed.

Eventually the Spaniards intercepted all food and water deliveries to the city. Even the Aztecs who tried to catch fish in the lake were caught. Many drank the salt water from the lake and got sick. Many of those trapped died of the famine. While the Aztec forces continued to be decimated, fresh Spanish troops arrived in Vera Cruz . A strong force under Francisco de Garay had actually set out to conquer the Pánuco area . However, it had failed there and so most of the men joined Cortés. More and more cities formerly allied with the Aztecs now sided with the Spaniards, such as Huichilibusco , Coyohuacan , Mizquic and all other places around Lake Texcoco.

Cortés was subject to a ruse on June 21, 1521. He followed the Aztecs, who had apparently finally been defeated, into the city. There Cuauhtémoc offered fresh forces against him. They killed many Spaniards and took around 60 prisoners. Cortés narrowly escaped captivity. Cristóbal de Olea saved his life and died himself fighting. The Aztecs sacrificed the captured Spaniards to their gods. They sent body parts of the dead to the peoples who fought on the side of the Spaniards and threatened them. In fact, they managed to get some cities back on their side. But Cortés sent a punitive expedition and prevented aid for Tenochtitlán.

Cuauhtémoc withdrew with his remaining troops to Tlatelolco , a district in the middle of the lake, but did not give up. When Cortés lured the Aztec warriors into an ambush, they pretended to accept the Spaniards' offer of peace, but attacked them again. But her strength was already too weak.

During a break in the fighting, many starved women and children fled to the Spaniards. Cortés sent Gonzalo de Sandoval and his men to the last part of the lake occupied by the Aztecs. There they tore down the houses and entrenchments. When there was no longer any way out, Cuauhtémoc fled across the lake in canoes with his family and their last loyal companions. García Holguíns, one of Gonzalo de Sandoval's men, was able to arrest the last ruler of the Aztecs, Cuauhtémoc, with his brigantine while he was fleeing on Lake Texcoco. It is estimated that 24,000 Aztecs died during the siege, which lasted several months.

On August 13, 1521, the almost completely destroyed city was finally conquered. There were many bodies lying in the streets that could not be buried. Cortés evacuated the population. The train of the half-starved people to the mainland lasted three days.

When the bodies were removed from the city and buried, Cortés began to rebuild Tenochtitlán. Charles V appointed him governor, chief judge and captain general of New Spain. This made him the most powerful man after the emperor. With the conquest of the Aztec Empire, Hernán Cortés laid the foundation stone for the viceroyalty of New Spain . Cortés confirmed Cuauhtémoc as King of the Aztecs. But only a short time later he had him tortured to find out where he had hidden the gold treasures. During the conquest of the country, Cortés had already worked towards a change in the religion of the Indians. Now he was bringing missionaries to New Spain.

With military advances to the north, he expanded his sphere of influence far beyond the borders of the former Aztec empire.

After the conquest

Forced labor for the indigenous population

On March 20, 1524, as captain general , Cortés issued the Ordenanzas de buen gobierno para los vecinos y moradores de la Nueva España ("Ordinances for good government for the inhabitants of New Spain "). In it he introduced the encomienda for the indigenous population: It was assigned to hundreds of Spanish settlers for forced labor , who in return were commissioned ( Spanish encomendar) to protect and Christianize them . The system had had devastating effects on the Antilles , as it left the indigenous population unprotected to exploitation by the Spaniards and, through the closer contact that this entailed, also promoted the spread of infectious diseases. Cortés had therefore spoken out in a letter to King Charles I against the expansion of the encomienda system to the American mainland. However, under pressure from those who participated in his campaign, who wanted to reap the fruits of their labors, and worried that they would otherwise leave the country, he relented. He ordered that the indigenous peoples were only allowed to be employed in agriculture, that is, by no means in mining, and set working hours and wages. He also stipulated that each encomendero should arm himself according to the number of indigenous people who had been assigned to him and that he should go to roll call at the responsible Alcalde three times a year . Violations were punished with fines or the withdrawal of forced laborers. The Encomenderos also had to stay at their place of residence for at least eight years and were not allowed to set out to conquer new, perhaps even more profitable, territories. In this way, Cortés created a militia that put down occasional indigenous uprisings and secured Spanish power in Central America even without a regular standing army . The Spanish court was skeptical of this approach. Under the impression of the campaign of the Dominican monk Bartolomé de Las Casas , Charles I Cortés forbade further assignments of indigenous people to Spanish settlers, because "Our Lord God made the Indians free and not subject to any servitude." The captain general simply ignored this letter. It was not until November 13, 1535, that a royal charter legalized Cortes' approach.

Campaign to Honduras

In 1523, Cortés sent Cristóbal de Olid to Honduras to conquer this land. Olid was a companion from the very beginning and had never given Cortés cause for suspicion. But he allied himself with Cortés' archenemy Velázquez and wanted to conquer Honduras for himself with the help of the governor of Cuba and make himself independent from Cortés. When Cortés heard about it, he sent Francisco de Las Casas with two ships to Honduras to take Olid prisoner. But because Cortés hadn't heard from Las Casas for a long time, he set out for the south with an army of several hundred Spaniards and three thousand Indian auxiliaries in the fall of 1524. Fearing that the last king of the Aztecs, Cuauhtémoc, might instigate a revolt in the capital while he was away, Cortés took him on the campaign. On the way, he is said to have allegedly been guilty of a murder plot and was hanged by the Spaniards. The campaign to Honduras almost failed due to the rigors of the road, the bad weather and the hunger. Many participants of the expedition died in the fighting with the hostile Indian peoples.

Meanwhile, Las Casas landed in Honduras and was captured there. During a meal together, however, Las Casas injured his host Olid with a dagger and had him beheaded in the market square of Naco . In 1525 Las Casas traveled by ship to Veracruz and overland to the capital Tenochtitlán. There he was arrested by Cortés' opponents and sentenced to death for the murder of Olid. The sentence was not carried out because he wanted to ask the emperor for mercy. He was brought to Spain in chains, where he was acquitted two years later.

Because there was no news of Cortés in Tenochtitlán for a long time, the rumor arose that he was no longer alive. His enemies took this rumor as a fact to the Spanish royal court and shared his property. When Cortés found in Honduras that Las Casas had done its job, he took the ship via Havana to Vera Cruz. He was enthusiastically received in New Spain and, especially in Tlaxcala, greeted with great enthusiasm. However, he had lost absolute power through his long absence.

On December 13, 1527, Charles V appointed an Audiencia for New Spain. It was supposed to take over the government of the colony and consisted of a president and four oidores (judges). Its president was Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán . The judges were Juan Ortiz de Matienzo, Diego Delgadillo, Diego Maldonado and Alonso de Parada.

At the emperor's court

The Bishop of Burgos , Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca , tried to trivialize Cortés' successes at the emperor's court or to ascribe them to Diego Velázquez. He provided one of his favorites, Cristóbal de Tapia, with documents and blank documents allegedly issued on behalf of the emperor . He wanted to bring de Tapia to power and give him the position of governor of New Spain. Francisco de Montejo and Diego de Ordas gave the governor of the King of Spain, Pope Hadrian VI. , a written indictment. According to these indictments, Bishop Fonseca took advantage of his power as chairman of the Consejo de Indias and had the messengers that Cortés had sent to the court in Spain thrown into prison. He withheld gold gifts and reports to the emperor. In Seville he prevented the urgently needed supplies of men and weapons from Spain. The bishop's complaints forced Cortés to go to Spain to the emperor's court to justify himself.

In 1528 he went to Europe on a speed sailer and made the journey from Veracruz to Palos in just 41 days. New Spain had been a province of Spain since October 1523. As the conqueror of this largest and richest province, Cortés saw himself in line with the most powerful European princes of his time. That is why he surrounded himself with a large retinue on the journey. He was accompanied by comrades-in-arms from New Spain and aristocratic Indians from Tenochtitlán, Tlaxcala and Cempoala. At his side were Moctezuma's sons and Maxixcatzin's sons, one of the princes from Tlaxcala. He was also accompanied by twelve Tlaxcaltek ball players as well as Indian musicians, singers and acrobats. He had gold, precious stones, objets d'art and exotic animals in his luggage. Gonzalo de Sandoval fell ill on the way and died in La Rábida. When Charles heard of Cortés' arrival, he had the local nobility pay him all honors.

At the official reception of the conquistador at court, Cortés appealed to the justice of his emperor and gave him a detailed account of the conquests and battles he had fought in the new world . He responded to the accusations of his enemies and denied that he had withheld gold from the crown, rather he proved that he had sent more than the required fifth to Spain. He had also contributed a lot of money out of pocket for the reconstruction of Tenochtitlán. Charles V owed a lot to Cortés; Without the rich gold and silver deliveries from New Spain, it would not have been possible for him to wage wars in Europe.

Cortés had always been loyal to him; the indigenous peoples of New Spain viewed him as the absolute ruler and supreme Tlatoani , even if he never called himself that. By building a palace on the ruined foundations of the palace of Moctezuma, he had made his claims known.

During the war of conquest, Cortés laid the foundations for his later demands. He had acquired in-depth knowledge of the country from numerous exploratory expeditions and campaigns of conquest and decided to claim the most economically profitable places and the key military locations for himself. In 1526, in a letter to his father, who acted as his representative at court, he had given a list of his territorial demands to the king, which he presented again in a petition in 1528 with minimal changes. The list only contains the main places; Cortés probably thought of the associated tributary provinces. Had Charles V accepted these demands, Cortés would have had substantial parts of the Aztec Empire as personal property.

Charles V appointed Cortés for his services to Knight of Saint Jacob and General Captain of New Spain and the South Seas ( Pacific Ocean ). In addition, on July 6, 1529 he was given the title and possessions of Marqués del Valle de Oaxaca ( Marquis of the Valley of Oaxaca ). With this award, however, only the possession of a part of the places and land areas required by him was connected, other important and attractive places Charles V had reserved for himself, including all ports. The locations actually awarded, as the definition below revealed, only included their immediate catchment area and not the corresponding provinces.

With the uprising, Cortés belonged to the high nobility of Spain. The title was held by his descendants until 1811. The Oaxaca Valley was one of the richest areas in New Spain. Despite all the honors, he was not reinstated as governor or viceroy in New Spain, so he remained without political power. It can be assumed that Cortés had become too rich and powerful for the emperor. In addition, the court had come to realize that the conquistadors were not suited to exercise the government of the new countries, as the fall of Columbus had shown. The king therefore retained the leadership of the new land to himself and entrusted it to men who did not have such immense domestic power.

A few days after the audience, Cortés fell so seriously ill in Toledo that it was assumed that he would die. At the request of the Duke of Béjar , Charles V visited the apparently terminally ill Cortés accompanied by the nobility. This visit was seen as a great token of favor.

Return to New Spain, discovery of California

In 1530, Cortés embarked for New Spain again, but only had military authority. On his return he found the country in anarchy . After order was restored, he focused on exploring the west coast of New Spain.

The management of civil affairs has been entrusted to an authority, the Audiencia de Nueva España . Antonio de Mendoza was sent to New Spain as viceroy, but did not arrive there until 1535, where he took over civil administration. Cortés retained military power and had permission to continue his conquests. This division of power led to constant disputes with the viceroy. Tenochtitlán was renamed Ciudad de México (Mexico City).

Cortés had ships built on the west coast of New Spain at his own expense. In 1536 he discovered the Baja California peninsula on an expedition . In 1537 he sent three ships west across the Pacific. They were under the command of Álvaro de Saavedra , who was tasked with finding the Spice Islands ( Moluccas ). But the expedition failed on the way back in the Pacific.

In 1539 he equipped another expedition at his own expense and sent Francisco de Ulloa with three ships from Acapulco in a northerly direction along the west coast of New Spain. His mission was to explore the coast and find a sea route in the north of the American continent to Europe. Probably to please his client, Francisco de Ulloa named the Gulf of California Mar de Cortés (Lake Cortés). Although he had reached the end of the gulf and then circumnavigated the Baja California peninsula, Baja California was shown on maps as an island on his return.

Last years and death

In 1541 Cortés traveled to Spain again, but was welcomed there with cold. His claims were not heard in court. The emperor allowed him to join the fleet of Andrea Doria on the campaign to the Berber coast to Algiers and to fight against the Ottomans . Despite the concerns of experienced sailors, Charles V ordered the attack on Algiers. The fleet got caught in a storm off the Algerian coast. The troops could not be disembarked for two days. When the men finally went ashore on October 23, they had to wade through deep water with their heavy luggage. After only a fraction of the troops, horses and provisions had been unloaded, bad weather set in again and prevented the other ships from unloading. On the night of October 24th to 25th, the storm turned into a hurricane. The Esperanza, the ship of Cortés, sank with over 150 other ships. He and his sons were barely able to save himself. Despite his experience in conquering the Aztec Empire, Charles V did not invite him to the council of war. Cortés took this as a deliberate insult to himself.

The chronicler Francisco López de Gómara took part in the campaign in the wake of Cortés and wrote:

“Cortés then offered to take Algiers by storm with the Spanish soldiers and the German and Italian forces who had already landed, if that would serve the emperor. The men of war loved such speeches and praised him very much, but the sailors and others did not listen to him. And so he went on the assumption that His Majesty had no knowledge of it. "

Cortés had used a lot of money to finance his expeditions. In February 1544 he filed a claim for reimbursement from the royal treasury, but was only put off for the next three years and referred from one court to the next. Disgusted, he decided in 1547 to return to New Spain. But when he reached Seville , he fell ill and died on December 2, 1547 on his estate in Castilleja de la Cuesta at the age of 62. His bones were buried in Mexico, but disappeared in 1823.

Children and offspring

Hernán Cortés was married twice and had a total of eleven documented children from a total of six relationships. His first wife, Doña Catalina Juárez Marcaida, died childless on November 1, 1522. By his second marriage in 1528, Cortés had five children from various relationships:

- Catalina Pizarro, (* 1514 or 1515 in Cuba). Her mother was Leonor Pizarro, possibly a relative of Cortés. She and her half-brothers Martín and Luis were legitimized by Clement VII in 1529 through a papal bull .

- Martín Cortés with the nickname El Mestizo (* 1522 or 1523 in Coyoacán ) from the relationship with Malinche . It was legitimized by a papal bull in 1529.

- Luis Cortés (* 1525) from a relationship with a Spaniard, Antonia (or Elvira) Hermosillo. It was legitimized by a papal bull in 1529. He married Doña Guiomar Vázquez de Escobar, niece of the conquistador Bernardino Vázquez de Tapia.

- Leonor Cortés y Moctezuma (* 1527 in Tenochtitlán). Daughter of Tecuichpoch , who was baptized Doña Isabel de Moctezuma by the Spaniards and who was a daughter of Moctezuma II. Leonor was rejected by her mother after giving birth, but was later recognized by her father. She married Juan de Tolosa, conquistador of Zacatecas.

- María Cortés, daughter of an unknown Mexican princess. Bernal Díaz del Castillo noted that she had an unspecified disability.

In April 1528 Cortés married his second wife from the Spanish aristocracy, Doña Juana Ramírez de Arellano de Zúñiga, daughter of Conde de Aguilar and niece of Duque de Béjar. Doña Juana lived in the palace in Cuernavaca, which was completed in 1526 . From this marriage there were six children:

- Luis Cortés y Ramírez de Arellano (* 1530 in Tezcoco), died shortly after birth

- Catalina Cortés de Zúñiga (* 1531 in Cuernavaca), also died shortly after birth

- Martín Cortés y Ramírez de Arellano , also El Legítimo (* 1532 in Cuernavaca), inherited the title of Marqués del Valle de Oaxaca

- María Cortés de Zúñiga (* between 1533 and 1536 in Cuernavaca); later married Luis de Quiñones, 5th Conde de Luna

- Catalina Cortés de Zúñiga (* between 1533 and 1536 in Cuernavaca); died unmarried

- Juana Cortés de Zúñiga (* between 1533 and 1536 in Cuernavaca); married Don Fernando Enríquez de Ribera, 2nd Duque de Alcalá, in 1564

The titles of Cortés passed to the Neapolitan Duke of Monteleone in the 17th century by marrying the last female title holder .

Sources

Several detailed reports in letter form to Charles I have been received from Cortés himself, in which he describes his campaign against the Aztecs. However, the content of the letters cannot be taken as a certain fact. Cortés deliberately suppressed and falsified facts in order to justify himself to the emperor. So the Moctezuma's resignation from office to Cortés in favor of the Spanish ruler, described by Cortés twice in different situations, is undoubtedly a clever invention.

Francisco López de Gómara was an eyewitness to the Algiers campaign and was already working on his book Historia general de las Indias at that time . He was never in New Spain and relied on the statements of Cortés, of which he was local chaplain, and other conquistadors. The book was printed in Zaragoza in 1552 and banned by Philip II in 1553 , partly because López de Gómara glorified the deeds of Hernán Cortés too much and he did not take the truth very seriously.

In order to help the truth from his point of view, and in response to Francisco López de Gómara, Bernal Díaz del Castillo wrote : Historia verdadera de la conquista de la Nueva España (True History of the Conquest of New Spain). While López de Gómara only relied on the stories of others, Bernal Díaz del Castillo was an eyewitness to the conquest of the Aztec empire as a soldier and left the most precise and extensive records of this time with his book. They are colored by his intention to build a position opposite to Cortés.

The files of numerous trials of Cortés against his opponents and against the crown have been preserved in full. Their statements are less falsified than the reports of individuals about their interests and intentions, but they are not always necessarily objective. Although numerous files of the trials have now been published, much can still only be found in archives.

Bernardino de Sahagún did not arrive in New Spain until after the conquest of the Aztec Empire and in 1569 completed his twelve-volume work entitled Historia general de las cosas de Nueva España , the last volume of which also deals with Cortés and the conquest of New Spain from the perspective of the Indians.

reception

The image of Cortés has changed several times in the course of history. Despite the destruction of the cultural identity of the Indians and the violence triggered by the conquest, he was respected and even revered by many peoples of Central America; this is mainly due to the fact that he had destroyed the supremacy of the Aztecs. From the 19th century onwards, however, the conquistador in Mexico was rather poorly regarded, among other things. under the influence of the so-called Leyenda negra . There are still many streets and squares that bear his name, but the Aztec heritage is far more valued by many Mexicans than Cortés. With the Spanish conquest about 15 million of the natives lost their lives; Most of them died of the diseases brought in, but also of the direct violence of the conquerors. So it is not surprising that the merits of Cortés (the unification of Mexico, the end of the flower wars and the subsequent human sacrifices ) do not outweigh the destruction of indigenous culture in the minds of many Mexicans. More recently, however, there has also been a cautious re-evaluation of Cortés, driven among other things. by the Mexican Nobel Prize for Literature, Octavio Paz , who recognizes him as a heroic founding figure of modern Mexico.

- Stage and film

The life and conquests of Hernán Cortés have been the subject of many literary works since the 18th century. The topic was also popular in theater and music theater. In 1809, the Italian composer Gaspare Spontini , who worked in Paris, created a spectacular opera under the title Fernand Cortez on behalf of Napoleon I , which was successful throughout Europe. Later there were various other processing, including in the film.

- music

Neil Young addressed the battle between Cortés and Moctezuma in 1975 in the song Cortez the Killer from the album Zuma .

Sources in translation

- Hernando Cortés: The conquest of Mexico: three reports to Emperor Karl V. 5th edition. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt / Main 1980, ISBN 3-458-32093-8 .

- Arthur Schurig (ed.): The conquest of Mexico by Ferdinand Cortés. With the general's own handwritten reports to Emperor Karl V from 1520 and 1522. Insel Verlag, Leipzig 1923.

- Bernal Díaz del Castillo : History of the Conquest of Mexico. Ed. And edit. by Georg A. Narciss and Tzvetan Todorov. Insel Verlag, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-458-32767-3 .

literature

In chronological order:

- HD Disselhoff: Cortés in Mexico . Oldenbourg, Munich 1957.

- Hammond Innes: Die Konquistadoren (Second part: Cortez) Hallwag Verlag, Bern 1970.

- Herbert Matis: Hernán Cortés . Musterschmidt, Göttingen 1967.

- Meissner, Hans-Otto : My hand on Mexico. The adventures d. Hernando Cortés. Cotta, Stuttgart 1970; New edition: Klett, Stuttgart 1987, ISBN 3-12-920011-8 .

- Eberhard Straub : The Bellum iustum des Hernán Cortés in Mexico . Böhlau, Cologne 1976, ISBN 3-412-05975-7 .

- Tzvetan Todorov: The Conquest of America. The other's problem. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1985, ISBN 3-518-11213-9 .

- José Luis Martínez: Hernán Cortés ; Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México (DF) 1990, ISBN 968-16-3330-X .

- Richard Lee Marks: The Death of the Feathered Serpent. Droemer Knaur, Munich 1993, ISBN 3-426-26576-1 .

- Claudine Hartau: Hernán Cortés. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg, 1994, ISBN 3-499-50467-7 .

- Salvador de Madariaga : Hernán Cortés . Manesse, Zurich 1997, ISBN 3-7175-8236-4 .

- Hugh Thomas: The Conquest of Mexico. Cortés and Montezuma. Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 2000, ISBN 3-596-14969-X .

- Juan Miralles: Hernán Cortés. Inventor de México. México (Tusquets) 2001, ISBN 970-699-023-2 .

- Felix Hinz: "Hispanization" in New Spain 1519–1568. Kovac, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 978-3-8300-2070-7 .

- Vitus Huber: Booty and Conquista. The political economy of the conquest of New Spain. Campus, Frankfurt a. M. / New York 2018, ISBN 978-3-593-50953-2 .

- Vitus Huber: The Conquistadors. Cortés, Pizarro and the conquest of America. CH Beck, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-406-73429-8 .

Web links

- Literature by and about Hernán Cortés in the catalog of the German National Library

- Reports on Hernán Cortés

- La Conquista

Individual evidence

- ↑ Peter Bigorajski: The conquest of Mexico

- ↑ Cortés, Hernán: The Conquest of Mexico. Three reports to Emperor Charles V p. 323.

- ↑ Felix Hinz: motecuhzoma.de/Baracoa

- ↑ Peter Bigorajski: The conquest of Mexico

- ↑ Cortés, Hernán: The Conquest of Mexico. Three reports to Emperor Charles V p. 38.

- ↑ Jerónimo de Aguilar y Gonzálo Guerrero: dos actitudes frente a la historia. (Spanish).

- ↑ Carmen Wurm: Doña Marina, la Malinche. A historical figure and its literary reception . Burned up. Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 978-3-96456-698-0 , pp. 19 and 30 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Cortés, Hernán: The Conquest of Mexico. Three reports to Emperor Charles V p. 87.

- ↑ Hanns J. Prem : The Azteken-Geschichte-Kultur-Religion. Verlag CH Beck, ISBN 3-406-45835-1 , p. 19.

- ↑ Hanns J. Prem: The Azteken-Geschichte-Kultur-Religion. Verlag CH Beck, ISBN 3-406-45835-1 , p. 22.

- ↑ Hanns J. Prem: The Azteken-Geschichte-Kultur-Religion. Verlag CH Beck, ISBN 3-406-45835-1 , p. 39.

- ^ Gerhard Paleczny: The Fall of the Aztec Empire and the Consequences in the 16th Century , Grin Verlag, p. 13.

- ↑ Stefan Rinke: Conquistadors and Aztecs: Cortés and the conquest of Mexico . CH Beck, Munich 2019, ISBN 978-3-406-73399-4 , p. 147 f .

- ↑ Carmen Wurm: Doña Marina, la Malinche. A historical figure and its literary reception . Burned up. Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 978-3-96456-698-0 , p. 24 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Carmen Wurm: Doña Marina, la Malinche. A historical figure and its literary reception . Burned up. Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 978-3-96456-698-0 , pp. 27 f. (Accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, pp. 216f

- ↑ Cortés, Hernán: The Conquest of Mexico. Three reports to Emperor Charles V p. 108.

- ↑ Carmen Wurm: Doña Marina, la Malinche. A historical figure and its literary reception . Burned up. Frankfurt am Main 1996, ISBN 978-3-96456-698-0 , pp. 28 f. (Accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Hammond Innes: Die Konquistadoren Hallwag Verlag, Bern 1970, p. 117ff.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, pp. 221f.

- ↑ Felix Hinz: motecuhzoma.de/motecuhzoma

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, p. 243.

- ↑ Matthew Restall: Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2003, pp. 7 ff. And others; Daniel Grana-Behrens: The disintegration of the Aztec state in central Mexico 1516–1521. In: John Emeka Akude et al. (Ed.): Political rule beyond the state. On the transformation of legitimacy in the past and present. Springer VS, Wiesbaden 2011, p. 83 ff., Roland Bernhard: History myths about Hispanoamerica. Discovery, conquest and colonization in German and Austrian textbooks of the 21st century. Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht, Göttingen 2013, p. 120 ff.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, p. 263.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, p. 271.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, p. 273.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, p. 276.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: The Conquest of Mexico , p. 294f. ISBN 978-3-458-32767-7 .

- ^ Felix Hinz: Bernardino de Sahagún in the context of early historiography about the Conquista of Mexico

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, p. 363.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, p. 361.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, p. 371.

- ↑ Hanns J. Prem, The Azteken-Geschichte-Kultur-Religion. Verlag CH Beck, ISBN 3-406-45835-1 , p. 113.

- ↑ Peter Bigorajski: The conquest of Mexico

- ↑ Hanns J. Prem, The Azteken-Geschichte-Kultur-Religion. Verlag CH Beck, ISBN 3-406-45835-1 , p. 40.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, p. 402.

- ↑ Geoffrey Parker (Ed.): The Times - Great Illustrated World History. Verlag Orac, Vienna 1995, p. 271.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, p. 477.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, p. 376.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, p. 517.

- ^ Günter Kahle : The encomienda as a military institution in colonial Hispanic America . In: Jahrbuch für Geschichte Latinamerikas 2 (1965), pp. 88-105, here pp. 88 ff. (Accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Richard Konetzke : South and Central America I. The Indian cultures of ancient America and the Spanish-Portuguese colonial rule (= Fischer Weltgeschichte . Volume 22). Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1965, p. 183 f.

- ^ Günter Kahle: The encomienda as a military institution in colonial Hispanic America . In: Jahrbuch für Geschichte Latinamerikas 2 (1965), pp. 88-105, here pp. 90 ff. (Accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Richard Konetzke: South and Central America I. The Indian cultures of ancient America and the Spanish-Portuguese colonial rule (= Fischer Weltgeschichte. Volume 22). Fischer, Frankfurt am Main 1965, p. 184.

- ^ Günter Kahle: The encomienda as a military institution in colonial Hispanic America . In: Jahrbuch für Geschichte Latinamerikas 2 (1965), pp. 88-105, here pp. 82 f. (Accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico . 1988, pp. 614-617.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo Real History of the Conquest of Mexico p. 539.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico , 1988, p. 532.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, pp. 595-596.

- ↑ Costume book Munich around 1600 (14 drawings by Christoph Weiditz )

- ↑ Felix Hinz: motecuhzoma.de/wandel

- ↑ a b Felix Hinz: motecuhzoma.de/cort-karl

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, p. 717.

- ↑ Urs Bitterli, The Discovery of America , p. 234.

- ↑ Gerald Sammet, Die Welt der Karten , p. 15.

- ↑ Gerald Sammet, Die Welt der Karten , p. 204.

- ^ Naval Battle of Preveza, 1538

- ^ Alfred Kohler: Karl V. p. 259.

- ↑ Fabian Altemöller, Key Scenes of the Conquest of Mexico - a comparison of the writings of Cortés, Díaz del Castillo and Sahagún. Verlag Grin, p. 2.

- ↑ Hanns J. Prem: The Azteken-Geschichte-Kultur-Religion. Verlag CH Beck, ISBN 3-406-45835-1 , p. 117.

- ↑ Bernal Díaz del Castillo: True History of the Conquest of Mexico. 1988, pp. 680-682.

- ↑ Rudolf Oeser, Epidemics. The great death of the Indians. Smallpox, measles, flu, typhus, cholera, malaria. Publisher: Books on Demand GmbH, p. 81.

- ↑ Octavio Paz: HERNAN CORTES: EXORCISMO Y LIBERACION. Article on the 500th birthday of Hernan Cortés. 1985, accessed December 31, 2014 (Spanish, reprinted from the original article ).

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Cortés, Hernán |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Cortés, Hernando; Cortez, Ferdinand; Cortez, Fernando |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Spanish conquistador and explorer |

| BIRTH DATE | 1485 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Medellín , Kingdom of Castile and León |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 2, 1547 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Castilleja de la Cuesta near Seville |