Ideal nudity

Ideal nudity or heroic nudity are modern terms for idealizing nudity that does not reflect reality in art since ancient Greece . Rather, it stood for youth, beauty, strength, purity and related, primarily positively masculine qualities. In women, the idea of ideal nudity first emerged in the Middle Ages. The idea was handed down in various forms into the 20th century.

While the depiction of idealizing nudity in antiquity did not reflect reality, but rather real properties, since the Renaissance corresponding portraits were no longer based on nature, but on an idealizing world of ideas and thoughts. This means that their foundations in antiquity and modern times differ diametrically, despite optical overlaps and modern recourse to ancient art. On the other hand, this form of representation connects two epochs of occidental art and distinguishes them from other forms of world art.

Idealized nudity in ancient times

There is no written record of the reasons why the Greeks began showing people naked. Thus, it is left to archeology and art and cultural studies to discover the reasons for such representations.

The idea of depicting the human body in its nudity, which does not correspond to reality, but rather as an ideal, developed in ancient Greece. Both in myth and in lived reality, nudity is not the norm for either men or women. On the contrary, apart from exceptional situations or sports, going to the baths or in cultic contexts, both complete and partial nudity were the exception. But of all things ancient art, which shows nudity in a non-real, heroic way, was supposed to shape the image of antiquity in post-antiquity in a way that ultimately falsified reality.

Even with early examples of Attic - geometric art, such as the Dipylon Amphora , the idealized nudity is indicated. The people here are still designed as silhouettes , but certain aspects that symbolize masculinity and strength are particularly emphasized. The triangular shape of the upper body looks just as athletic as the striking thighs. Apart from swords on belts, clothing cannot be recognized. Nevertheless, it is clear that no real nudity should be shown here, because this would have run counter to the conventions for the depicted scene of the laying in of the dead . The representation symbolized ethical, aristocratic values. Nonetheless, the scheme of these apparent nude representations, which is also encountered in the small sculpture at the same time, was from now on developed further in Greek art. Mainly Syrian influences were in the 8th and 7th centuries BC. Responsible for a briefly produced group of statuettes of self-contained, naked women, the archaic naked mirror- bearers produced mainly in Laconia were influenced by Egypt. The next significant step for the representation of male nudity were the nude kouros statues in the Archaic period , which were based on clad Egyptian models . Here, too, nudity did not reflect reality, but an ideal of youth and athleticism. It is striking that the female counterparts, the Kore statues, were shown fully clothed. While the representation of naked athletes corresponded to the reality, the representation of naked warriors was against all (lived) reality. In the archaic era, different ways of depicting nudity diverged. In addition to the idealized form, there was also the depiction of craftsmen ( banauss ), who had just as little heroism in them as that of the naked actors of Greek comedy . On the phlyak vases of the red-figure Lower Italian vase painting of the 4th century B.C. In BC, nudity was even exaggerated and caricatured by costumes with large phalloi. The portrayal of naked and robbed fallen enemies also does not reflect an ideal, nor does the portrayal of naked women in the classical period who had no direct reference to religion or mythology . They did not show ideal cases of nudity, but generally straight women, that is, women on the fringes of society. They were inspired by Praxiteles ' statue of Aphrodite of Knidos based on the model of the hetaera Phryne , the first large-scale sculpture to show a woman completely naked. It became the most famous statue of antiquity, no other work has survived in so many copies. The statue initially seemed downright disturbing to contemporaries and troubled even later generations. The bare female breasts were generally restricted to divine and mythological persons in the Greek Classical period, and a typical scheme for the arrangement even emerged. The pubic area was generally covered by items of clothing or accessories, or at least the view of it was restricted with the hands held up, as in the Venus pudica type .

The widespread depiction of naked gods began in the 5th century BC. Until then, most of the male gods were dressed and depicted as bearded. In the classical period, the form of representation of some gods changed significantly. For example, Apollon , Dionysus or Hermes became gods who, through their nakedness and beardlessness, should ideally embody youthfulness and strength. Thus, the gods were rejuvenated and transfigured. Some goddesses, initially Aphrodite in particular , and later Nike too , were shown in an ideal embodiment of nudity. Nymphs and maenads, on the other hand, like satyrs , embodied a raw, sexualized nudity that had little to do with the ideal. These images of the Dionysian tryphe , like erotic images, have been standing alongside the heroic images since the early Hellenistic period.

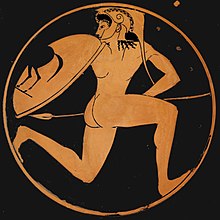

In vase painting there are also examples of heroic nudity in the Classical period, which can be seen in a direct line from the representation on the Diplon amphora. There are images of a warrior's farewell in which the warrior was shown naked, often only wearing his weapons, as an insignia of masculinity. Here, too, it is not possible to imagine a real farewell in naked form, but rather the interpretation as an idealized representation of youth, beauty, strength, courage and the will to fight. Since the idealized naked representation of gods became the norm, an idealized representation of naked real people was more and more an impossibility , especially in democratic Athens . It contradicted the principle of equality, only in the field of athlete representation was nudity still possible. Other regions of Greece also followed this development. Thus a Thessalian dynast could in the time between 336 and 332 BC. In Delphi only those of his ancestors who had really achieved success as athletes are honored with naked statues. It was different in the Boeotia region, for example , where the Attic idea of democratic equality and the rejection of individuals being distinguished from the crowd were of no importance. Here even fallen warriors could be shown naked and thus idealized on their tombs.

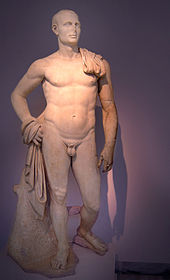

In men there was from the 5th century BC A gentle beginning development to leave the purely mythical level with the portrayed or to bring the portrayed people closer to gods and heroes through the portrayal. For example, the Parthenon Fries celebrated the ideal Athenian image of man by depicting naked Athenians. It is controversial in research whether these could possibly be Attic strategists . In the post-classical and Hellenistic period, the connotation changed from an idealizing nudity to a heroizing one. People were no longer shown so much in an ideal form as in a heroic form. The first person who, apart from being an athlete, was ideally portrayed naked was probably Alexander the Great . For him, too, nudity should stand for beauty, youth and strength. Because of his early death, these ideals were also given in Alexander's case. During Hellenism , the representation of naked rulers became the norm. As is often the case in Hellenistic art, idealism and reality were not infrequently combined. The bodies were designed in an ideal form, but heads, portraits and busts were often adapted to reality. In these cases, the sculptors combined naked young bodies with portraits that were obviously of age, such as baldness.

The Romans adopted this type of representation at various times. The decisive factor for the representation of people and gods in ideal nudity was the respective zeitgeist, which was mostly shaped by leading figures in public life or the imperial family. The setting up of completely naked sculptures in semi-official art was very rare until the early days of the Principate . It was not until the 2nd century that the traditional Greek-artistic conventions in Roman non-sacred sculptures gained in importance. A form of representation that was never used in this form by the Romans either before or after. During this time, certain Grecophile emperors and wealthy private individuals were depicted in heroic nudity. Naked heroic statues with portraits of emperors were therefore possible, especially in the 2nd century AD, as they lifted the sitter into mythical spheres and did not give the viewer the impression of the real nudity of the depicted. Sometimes female members of the imperial family were portrayed as Venus ; here, too, reference should not be made to the real appearance of the depicted. The adaptation of these forms of representation since Augustan times has made the image conventions independent. They were thus separated from the cultural roots. In spite of the increasing physical hostility influenced by Stoic philosophy and Roman literati, there was always erotic and Dionysian art up to late antiquity and the early Christian era.

Male subjects were generally portrayed in an anatomically correct manner, even if the genitals were mostly shown smaller than in reality. They should not detract from the overall aesthetic impression. The genitals were not believed to be that important to the heroic sense of the word, so real-size representation was not important and should not detract from the rest of the body. However, the intervention was far greater in the anatomy of the woman. Instead of the vulva , a flawlessly perfect triangle was shown, even pubic hair was rarely even hinted at. This “pure” groin remained the convention for depicting naked women in Western art until the 20th century.

Munich Kouros, around 540/30 BC Chr .; Glyptothek , Munich

Theseus and Procrustes , amphora by the Alkimachus Painter , around 470/60 BC Chr .; State Collections of Antiquities , Munich

Athletes on a chalice crater of Euphronios , around 510/500 BC Chr .; Antikensammlung Berlin

Farewell to Warriors: Jason and Medea , Roman sarcophagus , late 2nd century; Palazzo Altemps, Rome

Statue of Augustus , early 1st century; Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki

Phlyac scene by the painter Python . An actor wears a somatium caricaturing nudity as a costume, around 360/50 BC. Chr.

Middle Ages and Early Modern Times

The European Middle Ages knew four forms of nudity, of which only nuditas criminalis was rejected. The latter also included the ancient statues of rulers and gods. In medieval art, such naked statues were often depicted as haughty idols on their pillars. In early Christian times, the rejection of portraits in general was combined with an interpretation of the portraits of naked goddesses in a sexualized way that was contrary to ancient conventions. They didn't care about the real reception. A monk who designed a codex in Montecassino Abbey showed the Roman goddesses Juno and Minerva naked, which was in complete contradiction to ancient conventions. Aphrodite and Venus statues were also models for depictions of the personification of the mortal sin Luxuria ( lust , lust). Even biblical figures like Noah , Lot or Job were usually only shown naked if they were shown in a negative context.

The representation of the naked Hercules was seen differently . It was interpreted here allegorically and stood for strength. In addition, it was also transferred to similar biblical heroes such as Samson . The portrayal of Adam and Eve naked before the fall of man also had positive connotations. Like the naked Jonas , the forms of representation were taken from ancient art, but as an adaptation to the zeitgeist - as has sometimes been documented for Christian sarcophagi since early Christian art - a fig leaf was placed in front of the genital area. Representations of Jesus Christ often show him naked as the "New Adam". Allegorical representations, such as those of chastity , truth, and charity , were also often shown naked. Here the heroic nudity was finally transferred to portraits of women. These forms of representation continued to have an effect beyond the Middle Ages; in the Renaissance and modern times , such forms of representation of naked female beings went back to these medieval and not to ancient models.

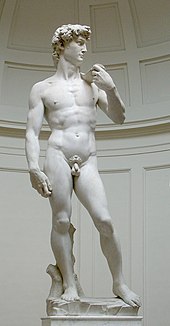

The recourse to the Middle Ages are reflected for a long time about it resists that even artists like Albrecht Durer , the Diana , Benvenuto Cellini , the Minerva or Antonio da Correggio showed naked against ancient conventions his Juno. The goddesses were symbols of chastity and were still represented in the medieval conventions for chastity. Only Raphael brings the ancient idols in the center of interest, the medieval representations were still alongside the recourses to ancient times, there are still long. However, recourse to antiquity penetrated even religious art during the Renaissance. With the naked Christ Child in Raphael's Sistine Madonna , for example, the ancient ideal can be clearly felt. Michelangelo, on the other hand, shows groups of naked youths in his Tondo Doni with the representation of the Holy Family in the background. It is a review of the idealized heroic antiquity. It is not always clear at first glance whether it is an antique or a Christian form of ideal nudity. For Donatello's David, for example, there are interpretations in one direction as well as in the other: on the one hand it is considered the first free-standing naked statue since ancient times, on the other hand it is interpreted as an allegorical representation of vulnerability in a Christian sense. In this way, one must also see the representations of male and female naked enslaved figures, which go back to ancient models and were made by Antonio Federighi in the cathedral of Siena as holy water basin bearers . Here ancient forms were reinterpreted as models for the victorious Christian. Next to it is a negative view that demonized ancient art, even Michelangelo's naked Christian heroes in the Sistine Chapel , whose representation was based on heroic ancient conventions, the naked nakedness was painted over in 1555. Nevertheless, the nudity all'antica had established itself in art in the 16th century , although it was customary to really orient it in form and content to ancient models. For example, Lucas Cranach the Elder created various portraits of Venus and the Paris Judgment .

Influenced by humanism , a representation scheme for nude heroic images of rulers developed early in late medieval, early Renaissance art. As early as 1390, Francesco Novello da Carrara was depicted with a naked bust on a medal based on a coin of the Roman emperor Vitellius . Other artists like Donato Bramante also follow this example. But here too there are forms of a Christian adaptation of this form of representation. Bishop Niccolò Palmieri , for example, had the saying from the book Job nudus egessus sic redibo ("I came naked from my mother's womb, I will go back naked") added. Other rulers were depicted completely naked according to ancient models. So let Andrea Doria in Carrara a statue erected of himself and Agnolo Bronzino painting a painting from him. In both cases, the most famous naval hero of his time was portrayed as Neptune . Even Charles V had a statue by Leone Leoni make that could be covered, however, if necessary with an armor. There is even a portrait of Martin Luther by Peter Vischer the Younger , which depicts Luther in heroic nudity surrounded by naked allegories of virtue.

The Counter Reformation ended such representations for a long time, especially in the private sphere. Only in the middle of the 18th century did this form of representation come into fashion again, now also without the Christian-religious, allegorical forms. Spokespeople in the revival of these forms of representation are Johann Joachim Winckelmann and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe ; in pictorial form, Jacques-Louis David is at the beginning of a revival. In France and Italy in particular, the nude portrait statue was becoming fashionable again at this time.

The model of ancient works of art, especially the statues, which, unlike painting, have been handed down in greater numbers, had an influence on modern artists that could hardly be overestimated. Since Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci it was customary to put on figures naked. The study of nature and antiquity came side by side, and even when there were enough nude models, the study of ancient works of art continued to be of central importance. In his theoretical writings, for example, Peter Paul Rubens advocates the study of ancient sculptures ( De imitatione statuarum , around 1608). The onset of academic art lessons in the 15th century also brought professional nude studies with it, but the works of art thus created had to fit into conventions and the problematic nudity turned into what was later called an unproblematic act . The study of ancient sculptures thus corresponds to an idealism that stands alongside naturalism. Both sides were seen as a prerequisite for perfecting artistic ambitions.

Tondo Doni by Michelangelo, 1506 to 1508; Uffizi Gallery , Florence

Peter Vischer's allegorical depiction of the victory of the Reformation with a naked Martin Luther

From the 19th century

One of the major works of this revival was the colossal nude statue of Napoleon I by Antonio Canova . Canova's art of persuasion was needed, as Napoleon was at first gracious, but then allowed himself to be convinced by Canova's arguments referring to antiquity. In 1831, Eugène Delacroix painted in heroic-allegorical nudity the freedom that led the people . In the period of Romanticism , such representations went back a little under Christian influence, but no longer disappeared completely. Towards the end of the 19th century there was another high point borne by the upper class. In 1891, for example, freedom as a woman and naked was depicted with the statue by the artist Vital Dubray, "The illumination of the world through freedom". The protagonists of this art are Auguste Rodin with his statue The Thinker or Max Klinger with his naked Beethoven torso. Even in the imperial representation, such portraits were possible again, as with the Kaiser Friedrich monument in Bremen .

The classicism is considered the epoch of art in which, as in no other, the notion of an ideal or heroic nudity shaped the art image. The terms were also coined during this time. During historicism , the depiction of heroic nudity faded into the background, apart from salon painting . It was only the art of modernism that began to reflect on the ancient models and the role model character of this golden age . Artists like Hans von Marées , Pierre Puvis de Chavannes or Paul Cézanne create works that on the one hand take up the ancient formalisms, but on the other hand deal with gender in a relaxed manner. The recourse to antiquity also comes into play in photography . Wilhelm von Gloeden often depicts young men ( Ephebe ) even within ancient ruins in Posen, which have been adopted from ancient art. The more academic reception was opposed to an escapist form. In the wake of the emerging nudist culture , artists like Fidus attempted a relaxed approach to the human body, which in its ideal form was placed at the center of art.

Around 1900 a " new classic " began to emerge . It reached a final climax during the fascist regimes in Europe from the 1920s to 1940s. Soldiers were shown heroically exaggerated at war memorials in ancient tradition. Artists like Arno Breker mostly created allegorical works, some of which are viewed critically by modern art history. But artists such as Arnold Böcklin , Pablo Picasso or Mario Sironi also contributed important works in painting, Aristide Maillol , Louis Tuaillon and Georg Kolbe in sculpture.

Felix Kupsch , Cenotaph for the Fallen in the Flak Artillery , 1933, Berlin

literature

- Nikolaus Himmelmann : Ideal Nudity in Greek Art (= yearbook of the German Archaeological Institute. 26th supplement). de Gruyter, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-11-012570-6 .

- Nikolaus Himmelmann: Heroic Nudity. In: The same: Minima Archaeologica (= cultural history of the ancient world . Volume 68) Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 1996, ISBN 3-8053-1893-6 , pp. 92-102.

- Rolf Hurschmann , Ingomar Weiler , Dietrich Willers : Nudity. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 8, Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-476-01478-9 , Sp. 974-978.

- Berthold Hinz : Nudity in Art. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 15/1, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-01485-1 , Sp. 649-656.

- Sabine Poeschel : Strong men, beautiful women. The story of the act. Scientific Book Society / Philipp von Zabern, Darmstadt / Mainz 2014, ISBN 978-3-8053-4752-5 .

Web links

Remarks

- ^ Rolf Hurschmann, Ingomar Weiler: Nudity: A. Mythos; B. cult; C. Everyday life and sport. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 8, Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-476-01478-9 , column 674 f.

- ^ Dietrich Willers: Nudity. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 8, Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-476-01478-9 , Sp. 676 .. Cf. also Walter August Müller: Nudity and exposure in ancient oriental and older Greek art , Leipzig 1906.

- ^ Dietrich Willers: Nudity. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 8, Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-476-01478-9 , Sp. 676.

- ^ Dietrich Willers: Nudity. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 8, Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-476-01478-9 , Sp. 676.

- ^ Dietrich Willers: Nudity. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 8, Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-476-01478-9 , Sp. 677.

- ^ Dietrich Willers: Nudity. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 8, Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-476-01478-9 , column 676 f.

- ^ Robert West: Roman portrait sculpture , Volume 1, L'Erma di Bretschneider, Rome 1970. p. 153.

- ↑ Detlef Rößler : The portrait of the emperor in the 3rd century . In: Klaus-Peter Johne (Ed.): Society and economy of the Roman Empire in the 3rd century. Akademieverlag, Berlin 1993, ISBN 3-05-001991-3 , pp. 319-375; here: p. 337.

- ^ Dietrich Willers: Nudity. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 8, Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-476-01478-9 , Sp. 677.

- ^ Berthold Hinz: Nudity in Art. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 15/1, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-01485-1 , Sp. 649.

- ^ Dietrich Willers: Nudity. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 8, Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-476-01478-9 , Sp. 677.

- ^ Berthold Hinz: Nudity in Art. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 15/1, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-01485-1 , Sp. 649.

- ^ Berthold Hinz: Nudity in Art. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 15/1, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-01485-1 , Sp. 649.

- ^ Theodor Hetzer: The Sistine Madonna , Frankfurt a. M. 1947, p. 13.

- ^ Berthold Hinz: Nudity in Art. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 15/1, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-01485-1 , Sp. 651.

- ^ Berthold Hinz: Nudity in Art. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 15/1, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-01485-1 , Sp. 654.

- ^ Berthold Hinz: Nudity in Art. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 15/1, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-01485-1 , Sp. 655 .; Karina Türr: On the reception of antiquity in French sculpture of the 19th and early 20th centuries, Berlin 1979.

- ^ Berthold Hinz: Nudity in Art. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 15/1, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-01485-1 , Sp. 655.

- ^ Berthold Hinz: Nudity in Art. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 15/1, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-01485-1 , Sp. 655.