Integration space

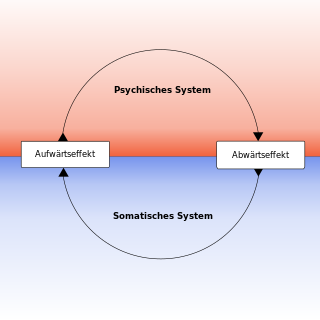

Integration space (derived from the Latin integer = untouched, whole; see integration sciences ) is a concept of psychosomatic medicine and goes back to Thure von Uexküll . It is a model of the unity of soul and body. It is to be compared with the reductionist and z. Sometimes also the analytical models. Regardless of the concept of integration space, the terms have become synonymous in meaning integration psychology and integration typology naturalized by which the unity of personality and environment is called. The concept of ›environment‹ also has a topological meaning in common with ›integration space‹, which Thure von Uexküll refers to in connection with the biostructural world of its own ( anatomy , histology , biochemistry ).

Spatial models as organizational principles or as a means of metaphorical illustration

In neurology, psychiatry and psychosomatics, special physical models automatically also have spatial dimensions as an object. The neurologists John Hughlings Jackson (1835–1911) and Charles Scott Sherrington (1857–1952) have dealt with individual functions and their interaction, particularly between psychological (higher) and purely physical (lower) central nervous centers or switching points. You have thereby expressed a spatial psychophysical continuity . Sherrington spoke of an integrative function of the nervous system. This reduced the distinction between simple physiological and complex psychological reactions to the question of different localization of these switching centers. - Certain analytical models by Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), which thus apparently contained a conceptual separation of body and soul, require concrete physical terminology and a physiological understanding. Such models are e.g. B. to look at the conversion model , the hypochondria or the model of the organ neurosis .

In psychosomatics, spatial dimensions initially show special physical model ideas, such as certain analytical models by Sigmund Freud , which presuppose a concrete physical terminology and thus apparently also a conceptual separation of body and soul. Such models are e.g. B. to look at the conversion model , the hypochondria or the model of the organ neurosis . Spatial models like that of the integration space want to provide more than just information about specific biostructural (e.g. anatomical) conditions. They serve as metaphorical schemes to better illustrate complex psychological issues, but often do not just represent mere metaphors. It can often be stated that the same regularities exist at different levels of integration, see also Chap. Integration levels . Just as the body schema serves as a source of orientation in a special neuropsychological respect and at the same time as a means of coordination, the general concept of the integration space is to be understood as a force field that is decisive for every human activity in the individual case, but also goes beyond the respective individual body . Like the homunculus in the case of the body scheme, the integration space does not correspond to the exact anatomical conditions. These organizational principles only represent a physical scheme that represents the body and includes it in an overarching concept. The somatotopy is a similar biological organizing principle. Here, too, it is not about exact depictions of organ systems, but about the topical representation of these systems in the nervous system, where they are combined into functional units according to different functional aspects. It is similar with the clinical symptoms of the hysterical . It is not determined by the objective anatomy as presented in the textbook. Therefore, Thure von Uexküll makes the demand for a dynamic anatomy as the basis of the integration space. The justification for speaking of an “anatomy” arises from the fact that many of the facts qualified as psychological do not represent metaphysical facts, but can be traced back to physical foundations. A strict separation of purely physical and purely psychological facts appears to be inappropriate. Rather, the distinction represents a structured continuum. The requirement for a dynamic or subjective anatomy has also been taken up by other authors. The theory of layers goes back to Aristotle . Freud's so-called structural model of the superego, ego and id is also to be assessed as such a spatial biostructural model. There is a certain physical analogy with the body scheme of the head, heart and stomach that has been known since ancient times. Freud basically started from a topical approach in the case of psychological symptoms even in cases in which specific physical disorders were not present. In many cases, the term organ medicine expresses the separation of soul and body or the lack of psychophysical continuity or the shortcomings in the simplistic approach to the complexity of psychological approaches.

Comparison with other sciences

There are also visual spaces in mathematics, as an example of a pure science in which one z. B. speaks of vector spaces or of topological spaces . In physics and many other branches of science one speaks z. B. of and fields . Based on such analogies, there have been numerous concepts in psychology and psychiatry. Here, too, corresponding spatial concepts serve for a better understanding of psychological phenomena, see also → Field Psychology . Freud's concept of the excitation sums e.g. B. includes the idea of such spaces in which affects and the associated psychodynamic forces are summed up according to an assumed mathematical-vectorial or “ algebraic ” procedure (“affect amount”). Thure von Üexküll speaks of topological determinations when it comes to conceptual differentiation between mental and physical illnesses such as a swallowing disorder in the example mentioned. However, this does not necessarily mean the three-dimensional space of the natural sciences. Integration can also mean alignment with value structures and behavioral patterns. What is meant is a topological space .

Division and integration

When a doctor z. B. says that a diphtheric swallowing disorder is a physical illness, while a hysterical swallowing disorder is a psychological one. This mind-body problem basically represents a frame of reference for both types of disorders, psychological and physical. In order to understand and illustrate this, it makes sense, in analogy to the physical space to which we are physically bound, us too to present a ( metaphorical ) space for the relationships between physical and psychological areas, the integration space .

That this is not a mere conceptual construction, but something primarily given and thus empirically tangible, is proven by the fact that we have such different areas or spaces, e.g. B. only become aware through an illness. It is only through illness that such originally intact spaces of integration become apparent. A physically induced swallowing disorder z. B. could have the consequence that the affected person can no longer follow his previous eating habits in the family. As is well known, this is a social impairment that could possibly even lead to further psychological repercussions. If necessary, it dissolves previously existing relationships that were taken for granted and into which the sick person was previously integrated. This is better called a split, because the fragments of reality still exist, only the cohesion appears to have been dissolved., See also → Sense of Coherence

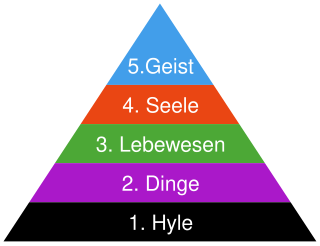

Integration levels

The integration space is divided into " integration levels " by encompassing supra-individual areas of the environment. The human anatomy, on the other hand, is limited to the individual. The transitions from individuals to groups, communities or cultures, for example, can be viewed as individual stages of integration. However, there is an operational connection. In a similar way to how the body is made up of individual organs and cells, society also consists of individual organizations and individuals or citizens. Similar to the way that the cells of an organism are “taken into service” by a functional association, so too are individual individuals from social groups, communities and their cultures. This was also the basic idea that originated from the discoverer of cellular pathology, Rudolf Virchow , and inspired him to found social medicine . His cell theory was for him a model of the democratic state that was just to be created. The hierarchical order to be described in this way results in two different approaches. The first point of view expresses how the requirements of a higher level of integration and its complex units are assessed by the individual. The second point of view says from the perspective of the complex and higher level of integration which tasks have to be fulfilled in cooperation with other interacting individuals and which role expectations exist. In this way, the integrating individual changes into a subject in the sense of psychosomatics. It is also an expression of a multidimensional approach that symptoms of illness can manifest themselves at different levels of integration, even though they are only caused from a single level. This should prevent the impression that an interaction can only take place “from level to level” in the sense of a hierarchical structure. Rather, the idea of a network is appropriate here, ie a “meshing” of the individual levels, see also Chap. Multiconditional diagnostics . Thure von Uexküll thus represents the point of view of psychophysical correlation or the context of meaning. The manifestation of noxae at any level of integration speaks for the theory of unitary psychosis and indeed for a continuum of the integration space. An alcohol addiction can be as such. B. be caused by an endogenous psychosis . This phenomenon has also been described with the help of the layer theory according to Karl Jaspers (1883–1969). Jaspers thus represents the point of view of causality or the causal connection.

Psychosomatics and Organ Medicine

Since models are usually expected to be more clear, it is useful if they make use of a perceptible representability or at least a corresponding imaginability. If models refer to objects that are not necessary and directly accessible to the sense organs, such as physiological and psychological facts, either purely rational distinctions or schematic representational aids are required .

In organ medicine , such schematized presentation aids are only required to a comparatively small extent, e.g. B. in the representation of complicated anatomical relationships, such as in the brain anatomy or in the apparatus representation of internal organs that are largely withdrawn from direct sensory perception.

Max Neuburger presented the development of medicine as undulating movements between the view based on the purely anatomical localization of organ disorders ( topical diagnostics ) and a physiological way of thinking in the sense of a “general functional pathology ”.

In contrast to special pathology, general pathology is understood to be a doctrine of diseases that does not only focus on structural changes - i.e. H. refers to anatomical changes - of individual organs, but also takes other biological , physiological , chemical and physical aspects into account. Such factors are e.g. B. physical influences such as radiation and electricity , chemical influences ( poisons ), poor or missing nutrition, living external causes of disease ( parasites , bacteria and viruses ), geographical and meteorological pathology (topology!) And typical defense and degenerative reactions of individual tissues (e.g. B. Inflammation and Metaplasia ). The latter reactions can of course also be understood in the sense of topical diagnostics as exactly localizable changes in individual cell types. The cell ultimately represents an anatomically comprehensible subgroup of the organs. Based on this list it is already clear that environmental factors must also be taken into account in the system of a general pathology, which includes the requirements of psychosomatic medicine .

Herbert Weiner comes to a similar conclusion with his thesis, according to which supporters of a doctrine of structures and those of a doctrine of functions faced each other even among doctors in antiquity. Viewed in this way, Hippocrates and Galen were the first structuralists, cf. → Hylemorphism and Hylozoism . This structuralist-materialist approach continued up to Giovanni Battista Morgagni and Rudolf Virchow . The functionalist side of medicine, on the other hand, is to be seen in the pre-Socratic thinking and the primordial theory of Thales of Miletus , Anaximander , Anaximenes to Anaxagoras and Empedocles , with whom each other also i. S. an antinomy opposing elements fire - water, earth - air can still be seen as a balanced and holistic concept. Instead of the contrast between structuralists and functionalists, Thure von Uexküll speaks of the contrast between generalists and specialists. To clarify the functional point of view, he says, " William Harvey would have had a difficult time demonstrating blood circulation on a corpse".

For organ medicine, the human body is largely to be seen as the sensually perceptible model of organically caused or organically localizable disorders and damage. In physiology and psychology, both physical and non-physical ( abstract ) ideas are required to clarify certain complex and difficult-to-understand relationships. Such an auxiliary construction is u. a. the integration space, which is of course withdrawn from a sensually concrete or only body-related view and mostly relates to functional or life-historical aspects.

Multiconditional diagnostics

The model of the integration space is therefore more intended for the type of general practitioner than a generalist, whose professional practice requires “no major (technical) equipment” and “often also provides more general information possibilities” than special apparatus-based examination possibilities aimed at an exclusively organic diagnosis. Representatives of classical (German) psychiatry also call for such a general and overarching multi-conditional diagnosis . Thure von Uexküll speaks of the need to use “supra-disciplinary” or “multidimensional systems of terms” for psychosomatic medicine, see also Chap. Levels of integration .

The question arises as to which supplementary system of pathology psychosomatic medicine has to offer as an alternative to the model of pure organ medicine. Wesiack distinguished between three pathologies:

- the relationship pathology

- the functional pathology

- the organ and cellular pathology after Morgagni and Virchow

He has assigned relationship pathology the first and overriding role over the other two.

Integration space and organization

The branches of science in which the concept of function plays an important role are just as diverse as the use of the term integration . As is well known, these sciences have an inner relation to organization , a relation which is taken from the symbol of the interaction of organs within a body.

Organization can be summarized as follows: history , cybernetics , computer science , political science , linguistics and sociology . Thure von Uexküll makes the demand that psychosomatics adjust itself primarily to the conceptual systems of politics, history, medical sociology and cybernetics.

Degree of integration

The degree of integration is a statistically defined term in sociology and describes the only partial reference of the individual to society or the conscious attitude towards and within social structures. The individual can never participate in all groups, strata and institutions of a society. The degree of integration is determined by the number of groups or institutions in which the individual participates. For the consensus of the individual, however, the purely statistical numerical value is not decisive, but rather whether he can identify with the groups open to him with their role expectations, value standards, orientation and behavioral patterns (authentic social integration). There are many examples of how one tries to escape the feeling of being isolated by participating in as many cliques, groups, associations as possible, but without identifying with one of these groups. This is a socio-psychological fact. The degree of socio-psychologically unaffected and authentic integration defines not only the presumed consensus but also the deviant behavior at the same time.

Force field of politics and history

The degree of integration thus not only determines the extent of the consensus, but at the same time also the degree of deviant behavior. However, deviant behavior often elicits social responses in the form of sanctions. Such mechanisms of social control are the main component of all politically and ideologically controlled processes of social integration . These take place u. a. with the help of religions, ideologies, philosophies and the media derived from them (educational institutions, political and cultural instruments of domination ). In this way, social control is always connected with domination or with compulsion as the exercise of hierarchically organized power relations. In this way, however, it also repeatedly creates counter-forces with a disintegrative effect, which are concerned with changing existing social structural relationships in favor of realizing new interests.

If cultural factors such as religions, ideologies and philosophies have an often underestimated influence on the willingness to integrate into society, they are automatically of political interest. It is not only when psychology leaves the narrow boundaries of individual mental processes ( individual psychology ) and recognizes the importance of social factors ( social psychology ) that it is of political interest. Your individual psychological findings also prove to be valid in a social or socio-psychological respect. There are numerous examples of political interest. Thure von Uexküll mentions above all the historical controversy between the meaning of the plant (or genetic material ) and life history. In other words, it is about the question of whether certain human characteristics must be considered innate or acquired. From 1933 the belief in the omnipotence of the hereditary mass became a political dogma in Germany. After 1945, on the other hand, it was considered backward and undemocratic not to swear by the omnipotence of living conditions. The Soviet biologist Trofim Denissowitsch Lyssenko (1898–1976) established the theory that genetic factors are changed by environmental influences ( Lyssenkoism ). In doing so, he advocated a thesis that contradicted Western research. In the West, hereditary factors were considered constant. Lyssenko's theory, however, matched the teachings of dialectical materialism . According to this, the human being is the product of social conditions. The same applies to the Soviet scientist Ivan Petrovich Pavlov . His theory of reflexes remained connected to the points of view of neurophysiology and thus of natural science, which were recognized in scientific circles and socio-political , although he had reached the limits of psychology with the conditioned reflexes he described . His doctrine of conditioned reflexes was also consistent with the political doctrine, according to which it is not innate properties but acquired abilities that determine the mental processes that are mediated by the animal nervous system .

In connection with the increasing political importance of the problem of integration, in view of the increased international migration, the problem of the lack of recognition of psychoanalysis and psychosomatic research in Germany should also be pointed out. As a result, many researchers emigrated to the USA before, during and after the Nazi era. Freud emigrated to London. The focus of psychosomatic research began to shift to America. This included the fact that the tradition of patriarchalism in Germany has never been completely torn down. Here the belief in divine right and in innate leadership qualities was only partially shaken by the thoughts of the French Revolution . Rather, he embodied himself in the claim to leadership of the entire German people. Historically, Germany looked back on a long tradition of noble families and princely houses, while in the Anglo-Saxon countries and in France the teaching of the philosopher John Locke (1632–1704) was widespread, a doctrine of the equality of people born as tabula rasa .

Medical sociology

The sociology of medicine gained relevance not only because of the problems of the sociology of science listed above using the example of Pavlov, Lysenko and Freud , it was also caused by the change in medical ideas and the spectrum of diseases. The catchphrase of the diseases of civilization came up. Such factors have resulted in a. to expand the one-sided biological disease model in favor of psychological and social factors. Psychoanalysis was not uninvolved in this. The role of the patient who makes the decision to see the doctor also had to be redefined. This applies above all to mental disorders and a new type of doctor-patient relationship, all the more since a more active self-image of the patient and more active cooperation and motivation with the therapist seem sensible and useful ( empowerment ).

As already explained in the above example of a physically justified swallowing disorder, the impairment of a very specific function can already have social consequences. According to Thure von Uexküll, the concept of the integration space should therefore include the concept of medical sociology. Examples of the adoption of originally sociological terms in the basic terms of psychosomatic medicine are terms such as provision or the term "reflex republic" used by Jakob Johann von Uexküll for the function of the nervous system in organisms that do not yet have a central nervous system, such as in sea urchins . Thure von Uexküll described this rather vegetative function as comparable to a “voting republic”. Society as such also offers itself as a model that comes close to that of the integration space. Just as the body consists of individual organs, organ systems and cells, society also consists of organizations, social classes and individual citizens.

cybernetics

According to Norbert Wiener , cybernetics encompasses both the control of living and machine systems. According to Thure von Üexküll, this property of a new science can serve as a model for overcoming the gap between psychology and physiology . Such a gap exists because physiology, like the basic science of physics, uses the basic concepts of energy and matter , so that it cannot correspond to the concepts of order and regularity, which are decisive for medicine. B. the concept of order in biology. Only ideas derived from natural philosophy such as entelechy , the building plan and the idea were derived from the terms order and regularity . Order and regularity do not arise from the conversion of matter into energy. Physics had not developed an interpretation model for the concepts of order and regularity . For them, order and planning are therefore a product of chance . Cybernetics, on the other hand, took over the concept of message from the social realm . If one raises the objection that the conception of physiology and physics corresponds to the functioning of apparatuses that also have a blueprint, this even leads to the question of what program a certain machine works according to . Purely mechanical devices have a program defined by the designer. Apparatus controlled by variable programs can take on variable tasks. Scheduling and order can not only be observed in animate and inanimate nature, but also in the area of unconscious activities and conscious action. Basic cybernetic concepts therefore also include the area of the subjective . However, the terminology of cybernetics finds a limit in questions of the allocation of meaning to the psychic, since the psychic cannot only be grasped in purely quantitative categories of increasing complexity. This division of meaning <?> Corresponds to questions about reference variable feed . With the help of association theory , the functioning of the calculators can be compared with biological behavior. Processes to be worked through step by step can be made understandable here , but not the motivation of living beings based on the models made available by cybernetics.

Nosology

In the following, nosological concepts are presented as possible units of an integrative “pathology”. They result from the demand for a multi-conditional approach or a multi-dimensional conceptual system.

Pathoanatomical (biostructural) concepts

- Organ pathology according to Giovanni Battista Morgagni = model of special pathology, e.g. B. " Fatty liver "

- Cellular pathology according to Rudolf Virchow = model of general pathology (histological pathology), e.g. B. "Cancer" or " Inflammation "

- Hereditary diseases according to Gregor Mendel = model of general pathology (chromosomal pathology, as a subgroup of cellular pathology ["cell organelles"]), e.g. B. Sickle cell anemia

- Infectious (caused by pathogens) pathology according to Robert Koch = model microbiology of general pathology, e.g. B. " Tuberculosis "

- Immunopathology according to Edward Jenner = model of general pathology (organic biochemical pathology), e.g. B. " Autoimmune Disease "

- Pathobiochemical = model of general pathology (inorganic biochemical explanatory models), e.g. B. for " tetany ", more specifically as symptoms alkalosis etc.

Pathophysiological Concepts

- Various psychosomatic concepts, e.g. B. Functional Syndromes , more specifically z. B .: "Stomach upset without an organic basis"

- Neuropsychological syndromes , see also the concept of the psychophysical level specifically e.g. B. " Neglect "

Pathopsychological Concepts

- Psychopathology (Heidelberg model), e.g. B. Diagnosis of " schizophrenia " with the help of symptoms of the first order according to Kurt Schneider

-

Neurosis psychological explanatory model according to Sigmund Freud , z. B. " Obsessional neurosis "

- Conversion model subgroup , e.g. B. "Hysterical Paralysis"

- Explanatory model psychosis , e.g. B. "Endogenous Depression"

- Anthropological disease concept z. B. after Walter Ritter von Baeyer , z. B. " Fear ".

- Bio-psycho-social disease model of the WHO , e.g. B. descriptive recording of diseases largely without nosological classification.

- Personality-based disease model according to Nikolaus Petrilowitsch , e.g. B. "abnormal personality"

- Multiaxial system according to ICD-10

- Salutogenesis according to Aaron Antonovsky

- Affect logic according to Luc Ciompi

- Relationship pathology according to Wolfgang Wesiack

See also

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Thure von Uexküll : Basic questions in psychosomatic medicine. Rowohlt Taschenbuch, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1963, (a) on head. “Overview of all main job information”: pp. 128, 131, 224 f., 229 ff., 234 f .; (b) Re. “Environment as social environment (society)”: p. 230, 233 ff .; (c) Re. “Demand for a dynamic anatomy”: p. 235; (d) on Stw. “Freud's terminology of the› affect amount ‹and vector psychology”: pp. 128, 145 ff., 183 ff., 204; (e) on Stw. “Vector spaces as a topological hierarchical system”: pp. 128, 227, 230 f .; (f) Re. “Integration space as an organizational principle or as metaphorical or topological space ”: p. 127 f .; (g) Re. “Illness as a split between body and soul”: p. 124 ff .; (h) on taxation “Integration levels”: pp. 224, 230, 239, 260; (i) on taxation “ multiconditional approach ”: pp. (225), 227, (239 ff.); (j) on Stw. “Mutual nosological influenceability at different levels of integration”: pp. 225, 227; (k) on “Psychosomatics and Organ Medicine”: p. 239 ff .; (l) on taxation “Multi-dimensional conceptual systems”: pp. 224 f., 227, (239 ff.); (m) on district “Degree of integration”: p. 220 ff .; (n) on tax authority “Lyssenkoism as an example of the political factor”: p. 37; (o) on Stw. “Political, philosophical and ideological factors: Freud and Pavlov”: p. 84 (footnote 4), 166; (p) on Stw. “Phenomenon: Emigration of Researchers to the USA”: p. 38 f .; (q) Re. “Current Issues in Medical Sociology”: p. 214; (r) on Stw. “Concepts derived from sociological phenomena” pp. 165, 174, 225 ; (s) on “Physical symptoms and social integration” p. 125 ff., 226; (t) on Stw. “Cybernetic Models as an Alternative to the Physiological Conceptual World” pp. 243–276; (u) to Stw. “The demand for a pluralistic concept of illness as an expression of the change in etiological ideas” p. 239 ff.

- ^ FA Brockhaus: The large foreign dictionary. Brockhaus Enzyklopädie, Leipzig 2001, ISBN 3-7653-1270-3 , p. 628.

- ↑ a b Peter R. Hofstätter (Ed.): Psychology . The Fischer Lexicon, Fischer-Taschenbuch, Frankfurt a. M. 1972, ISBN 3-436-01159-2 ; see chap. Layer theory (a) on evolutionary thoughts in the natural sciences: page 287; (b) philosophical and religious views that are too traditional: ( Neo-Platonism , Gnosis , Apostle Paul ) page 286

- ^ Charles Scott Sherrington : The Integrative Action of the Nervous System . Scribner, New York 1906; Cambridge University Press, London 1947.

- ^ Kurt Eissler : Medical Orthodoxy and the Future of Psychoanalysis . New York 1965, 138

- ↑ Richard Reitzenstein : The Hellenistic mystery religions: according to their basic ideas u. Effects . Unchangeable reprograph. Reprint d. 3rd, exp. u. reworked Edition Leipzig 1927; Knowledge Buchges., Darmstadt 1977, 438 p. DNB

- ^ Kurt Lewin : Principles of topological psychology . 1936.

- ^ Roy Richard Grinker (Senior) : The Psychosomatic Concept in Psychoanalysis . New York 1953.

- ↑ a b c d Karl-Heinz Hillmann : Dictionary of Sociology (= Kröner's pocket edition . Volume 410). 4th, revised and expanded edition. Kröner, Stuttgart 1994, ISBN 3-520-41004-4 , p. 377 f., Stw. Integration

- ↑ Aaron Antonovsky , Alexa Franke: Salutogenese, to demystify health . Dgvt-Verlag, Tübingen 1997, ISBN 3-87159-136-X .

- ^ Wilhelm Szilasi : Philosophy and natural science. Francke, Bern 1961.

- ^ Klaus Dörner : Citizens and Irre . On the social history and sociology of science in psychiatry. (1969) Fischer Taschenbuch, Bücher des Wissens, Frankfurt am Main 1975, ISBN 3-436-02101-6 , p. 307 f. (+ Footnote 320)

- ↑ Karl Jaspers : General Psychopathology . 9th edition. Springer, Berlin 1973, ISBN 3-540-03340-8 ; Cape. Nosology p. 512 f.

- ^ Rainer Tölle : Psychiatry . Child and adolescent psychiatric treatment by Reinhart Lempp . 7th edition. Springer, Berlin 1985, ISBN 3-540-15853-7 , on Stw. “Multidimensional approach”: pp. VII, 16, 174 f.

- ↑ Gerd Huber : Psychiatry. Systematic teaching text for students and doctors. FK Schattauer, Stuttgart 1974, ISBN 3-7945-0404-6 ; to Stw. "Multiconditional approach" pp. 9, 12, 13, 46, 55, 88, 95, 110, 123, 221, 229, 251, 305, 313, 337.

- ↑ a b c Klaus Holldack : Textbook of auscultation and percussion - inspection and palpation . [1955] Georg Thieme-Verlag, Stuttgart 1967, SV (preface by Curt Oehme) - Note: A textbook that deliberately wants to take into account the ›simple examination techniques‹, namely the findings that are directly perceptible to the senses (without special equipment). But even if you don't want to see the stethoscope as an apparatus, this book can of course not do without information on apparatus-based diagnostic medicine.

- ^ Max Neuburger (ed.): Handbook of the history of medicine . Jena 1902.

- ↑ Ursus-Nikolaus Riede, Hans-Eckart Schaefer: General and special pathology. Thieme, Stuttgart / New York 2001, ISBN 3-13-129684-4 .

- ^ Weiner, Herbert: Psychosomatic Medecine and the Mind-Body-Problem in Psychiatry . 1984.

- ↑ Luciano De Crescenzo : History of Greek Philosophy, The pre-Socratics. 1st edition. Diogenes-Verlag, Zurich 1985, ISBN 3-257-01703-0 , pp. 37, 40 f., 48, 182.

- ↑ causality. In: Hermann Krings et al. (Ed.): Handbook of basic philosophical concepts. Study edition, 6 volumes, Kösel, Munich 1973, ISBN 3-466-40055-4 , p. 781.

- ↑ a b Thure von Uexküll (Ed. And others): Psychosomatic Medicine. 3. Edition. Urban & Schwarzenberg, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-541-08843-5 , (a) p. 3, 1280; (b) p. 3.

- ↑ Gerd Huber : Psychiatry; Systematic teaching text for students and doctors. FK Schattauer Verlag, Stuttgart 1974, ISBN 3-7945-0404-6 , pp. 9, 12 f., 46, 55, 88, 95, 110, 123, 221, 229, 251, 305, 313, 337.

- ^ Wesiack, Wolfgang : Psychosomatic medicine in medical practice . Urban & Schwarzenberg, Munich 1984.

- ↑ René König : Sociology . The Fischer Lexicon. Frankfurt am Main 1958, p. 220.

- ^ A b Gustav A. Wetter : Philosophy and natural science in the Soviet Union . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg, rde vol. 67, (a) on district “Lyssenko”: p. 80 ff .; (b) on district authority “Pavlov”: pp. 96, 100 ff.

- ^ A b Siegrist, Johannes : Textbook of Medical Sociology . 3. Edition. Urban & Schwarzenberg, Munich 1977, ISBN 3-541-06383-1 ; (a) Re. “Change in the spectrum of diseases”: p. 11; (b) on the “doctor-patient relationship”: pp. 12, 115 ff., 174, 189, 206.

- ^ Schulze, Herbert: The Rororo Computer Lexicon . Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1988, ISBN 3-499-18105-3 ; Stw.-Lemma "Cybernetics" p. 298.

- ^ Wolf-Dieter Keidel : negotiation. Society of German Natural Scientists and Doctors . No. 101, 91 1960.

- ↑ Wolf-Dieter Keidel: Biocybernetics of humans . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1989, ISBN 3-534-09376-3 .

- ↑ Luc Ciompi : Affektlogik. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1982.