Functional Syndromes

Functional syndromes represent a combination of symptoms or symptoms (of syndromes ) that do not reveal any organic cause. This definition is valid both for general medicine and especially for psychosomatics . It is aimed at a disease process at an early stage, in which mostly no objective symptoms are recognizable. This characteristic situation in the early stages of the course of the disease gave rise to their designation as functional syndromes. Thus, they do not always turn out to be accessible to unambiguous investigation procedures that are based on precisely measurable or descriptively precisely ascertainable empirical findings. Such exact medical findings can usually z. B. be shown routinely with imaging or other apparatus-based examination methods or with procedures that are methodically as precisely as possible to be described. In the practical application related to functional syndromes, however, it is precisely this that results in considerable diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties. In contrast to the somatoform disorder of the ICD-10 , functional complaints are not limited to physical complaints, even if they are quite common in functional syndromes.

The occurrence of individual symptoms (lighter monosymptomatic forms) that relate to the functions of the organs or to the general state of health can also be described as functional disorders . As functional psychoses by Hans Heinrich Wieck psychopathological abnormalities were based psychopathometrischer defined studies. This was intended to express the pathophysiological character of mental disorders with and without organ damage in general . The term functional psychoses is often used synonymously for endogenous psychoses , see Chap. 9. Synonyms .

Explanation pattern

Functional syndromes often cannot be assigned to any common explanatory pattern. Often no objectively verifiable causes can be found for the patient's subjective complaints, such as: B. inflammatory changes in the stomach as an objectively verifiable cause of digestive disorders. This often missing concrete assignment of subjective complaints and objective findings makes it clear that illness is a theoretical construct whose typical characteristic is that it ultimately eludes exact verifiability. Syndromes classified as “functional” due to a lack of etiological correlation may show U. to the seldom explicitly discussed, but widespread difficulty of an operationalized medical procedure. Psychometric methods and psychopathological findings can also be operationalized . According to Karl Jaspers, the latter are collected using phenomenological methods . These procedures are intended to make the subjective statements and complaints easier to classify and thus understandable. But precisely when no meaningful result can be derived from this, the initially mentioned diagnostic and therapeutic difficulties arise. Operationalized procedures generally correspond to a common nosological classification scheme.

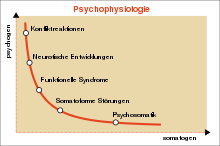

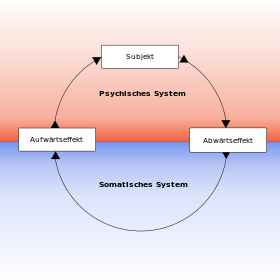

A common explanatory pattern for the simultaneous presence of very different (polysymptomatic) or individual very specific (monosymptomatic) symptoms is the psychophysical correlation . Physical damage can trigger subjective complaints (explanatory pattern of pathology ). Conversely, disorders of the subjective psychological well-being (so-called mental states) can also cause physical lesions , see adjacent figure. These questions include a. Subject of psychosomatic medicine . We therefore speak of “psychosomatic complaints” (downward effect) and “somatopsychic complaints” (upward effect). In philosophy, these questions are called the mind-body problem . - If effects can be traced back to a scientific-physical cause, this is referred to as a cause-effect relationship (principle of causality ). Diagnostic and therapeutic problems often arise when z. For example, due to a stressed scientific attitude, only a “single-line causality” is assumed, namely in the sense of an exclusive cause-effect relationship of the “upward effect” in ›all‹ disease symptoms ( machine paradigm ). With Karl Jaspers one can say:

"The single-line causality is an unavoidable category of our causal understanding, but life is not exhaustible with it."

To clarify, some examples of possible functional disorders appear appropriate: gastric and intestinal disorders, heart disorders, vasomotor disorders , secretion disorders, hearing disorders, voice disorders, menstrual disorders (absence or premature occurrence of menstrual bleeding), but also neurological findings such as headaches, paralysis, loss of sensitivity, Tics, tremors, disorders of the vestibular system ( dizziness , sudden hearing loss , tinnitus ), etc. are only a few of the very diverse functional symptoms. The extent to which they occur cannot be narrowed down any further. Ultimately, they are u. U. to "non-somatic", e.g. B. can be traced back to experience-related influences. The functional symptoms after successful clarification is, so to speak, "plausible", but not always scientifically "explainable". With regard to the systematic listing of functional manifestations in different organ systems, reference must be made to the correspondingly structured textbooks on organ or cellular pathology. The medical care system is mainly divided into organ specialties such as B. ENT , ophthalmology , gynecology , cardiology , etc. A functional syndrome that is common in terms of organ localization is the so-called cardiovascular syndrome . Another group of causal linkages are genetically determined causes of illness, which for their part are not to be understood as "organic", but as "somatic" or inherited disease constitutions . Many authors such as the Thure von Uexküll quoted here therefore differentiate between acquired dispositions to illness and inherited constitutions of illness. Both groups of causes, acquired and congenital causes of disease, can be conceptually separated, but in practice they are often linked and not easy to distinguish from one another.

The distinction between the somatic and mental systems - as shown in Fig. " Correlation " - does not expressly mean that the mental system is considered immaterial - e.g. B. as an immaterial soul - would be thought. The term “psychic system” means organic brain structures that, in contrast to other sections of the central nervous system , convey qualities of consciousness, so-called qualia . These qualia are to be understood as subjective states and contents of experience, as they are delivered by the various sensory modalities as conscious sensual impressions - e.g. B. optical or acoustic type - or how the subject consciousness z. B. conveyed as awareness of one's own identity or one's own body ( body schema ). Such qualia can indeed be described scientifically, but are not adequately explained, since this attempt at an objective description does not take into account the subjective character of modes of experience. Qualia appear empathetic but fundamentally not fully objectifiable. - The problem of "localization" or the localization and delimitation of this psychological consciousness system is the subject of questions about the psychophysical level . The "somatic system" means the vegetatively , immunologically or endocrine , etc. controlled system. It can also be called an unconscious system, because these organic reactions take place in such a way that they can be controlled automatically even without our will activity and without conscious decision.

Even if there are no clear body findings, functional complaints should therefore not automatically be interpreted as being caused by “psychological”, “vegetative”, “immunological” or “endocrine” without positive physical or laboratory findings indicating this! It is important to differentiate precisely in the interests of the patient. To avoid misdiagnosis, the basic requirement is to use a term that is as little prejudicial as possible. This means that diagnostic assignments or suspected diagnoses may contain as few unproven prerequisites as possible, as this can very well be the case with certain aforementioned exclusion diagnoses due to embarrassment or insufficient consideration. This requirement arises in particular with regard to a diagnostic procedure according to an only two-part physical-psychological classification scheme that is supposedly nosologically considered sufficient without mutual influencing. This distinction, which is often misleading in practice, can lead to false diagnostic and therapeutic consequences, especially if the search is ended with a pure presumption of emotional triggering. The tacit but incorrect assumption on which this procedure is based is that the patient's complaints either manifest themselves physically and then also have to be treated physically, or are immaterial and therefore have to be treated psychologically. In this way, however, the fact that the psychosocial and physical systems are interrelated and influenced is mostly overlooked.

Such often short-circuited medical consequences often prompt a referral to an organically oriented clinic that is only suspiciously justified - in the extreme case for surgical intervention - or a referral to a psychiatric clinic that is only suspiciously justified. These practices often wrongly lead the patient to believe that they are indeed suffering from the disease. The often somewhat hasty procedure has been named as a delegation of medical responsibility without sufficient positive clarification of alternative further causes of the disease. However, the requirement for comprehensive diagnostic clarification is not always met in practice for many different reasons.

Often it is as meaningful as it is indefinite For example, we speak of “ vegetative dystonia ” without any concrete findings of nervous damage or malfunction. With such a label, which is often used as a diagnosis of embarrassment , a psychological cause may be indirectly assumed without sufficient physical clarification by the doctor. The inadequately informed patient usually sees the cause as a predominantly physical problem with appropriate therapy plans - possibly a purely technical one - and less than a problem that he should become aware of in his own interest and that he should therefore continue to work on himself got to. Conversely, psychological problems can be played down with the help of this designation without further clarification of concrete psychological causes and mistakenly appear to the patient as problems of a physical nature. In both cases, however, a “coded diagnosis” should be assumed in order to disguise the existing complaints with a therapeutically less informative disease term from the no man's land between physical and mental disorders.

Heuristic problem

The heuristic requirement of the doctor or psychologist to arrive at a preliminary diagnosis that is as little prejudicial as possible in difficult cases is easy to understand, but not always easy to follow in a specific case. One problem already consists of fundamental considerations, since the apparently non-judgmental determination of a “functional syndrome” already contains unproven conditions. These can be explained in more detail as follows.

- The physiology is in the usual sense, the doctrine of the functions or services of the institutions. The hypothesis that there are medical syndromes that have a functional disorder "without organic cause," is basically the physiology at least partially suspended. The question arises whether symptoms of illness are theoretically conceivable at all without an objective physiological basis. Such an assumption would u. U. question the scientific mind-body relationship, as described in section Explanatory Patterns.

- The diagnosis of “functional syndrome” often means a mental disorder, similar to what was already criticized in the Explanatory Patterns section with regard to the diagnosis of vegetative dystonia . The hypothesis that there is a mental illness in the case of organic findings that cannot be ascertained is, however - as already stated - untenable. A mental illness should be positively diagnosed according to the established criteria. However, there are barriers to this, which at least to a large extent affect Germany's health system and which must be discussed further below, see sections Medical Standard and Social Interaction . In Germany, these are primarily medical-historical facts, cf. History section .

The question arises whether a possible concept of purely functional conditions without a pathophysiological basis should only apply pragmatically , as long as physical findings in specific individual cases have not yet been determined as the cause of complaints or have not yet been confirmed by science. A further requirement or hypothesis must be raised here, namely that facts that can be determined objectively-somatically as well as subjectively-psychologically must be counted among the foundations of physiology. The requirement for a psychophysiology is not new, but has so far only been partially realized and z. T. ideologically contested, cf. History section . In principle, there is no reason to doubt the scientific relevance of functional complaints, even if there are significant discrepancies in individual cases between the assignment of subjective complaints and (recognizable or non-recognizable) objective physical findings. The principle of psychophysical correlation does not speak against a physiological perspective and is in no way to be equated with spiritualism .

Here, however, also raises the very practical question of when the search for physical findings are terminated may , or even in terms of the exposure of the patient to be completed by engaging physical examinations must . Such interventions are sometimes not only diagnostically simple in character, but are increased up to surgical measures or up to steps of organ removal, cf. Section The Psychosomatic Ill . The demand for a relativization of indications to physical examinations is also supported by the statement that ongoing physical examination procedures “fix” the patient psychologically on the fact of an existing organic finding. Conversely, these concerns also apply to the presumption of the presence of a mental illness that has been persisted for too long. The absence of organ findings as a negative fact cannot automatically be reinterpreted as a positive fact of functional disorders. The question and demand for alternative nosological concepts arises.

Alternative concepts

Alternative concepts are seen as a way out of the dilemma of assuming as little prejudice as possible when diagnosing and treating functional syndromes.

general requirements

The alternative concepts and models mentioned here are, mind you, ideas of how one can imagine the influences of triggering factors on disorders of the functional relationship of the organs. Here, as for all models according to the ideal-typical construction of models according to Max Weber : "The more unreal, the better!" This maxim underlines the individual, but also the content of constructs or models guided by general ideas and their necessary character of abstraction from Individual fates. With "unrealistic" is meant here the distance from vivid concrete reality in the everyday sense. Kant already dealt with these constructions in his Critique of Pure Reason. He made a distinction between geometric and symbolic construction . Mathematics, as an abstract science, provides examples which, according to Kant, "without the aid of experience" expand the faculty of reason on the path of perception .

Nach den Lehren des radikalen Konstruktivismus sind für unsere Handlungen und Haltungen nicht allgemeinverbindliche Abbilder der Wirklichkeit als solche bestimmend, sondern individuelle Wirklichkeitskonstrukte, die auch als Wirklichkeiten 2. Ordnung bezeichnet werden. Sie unterscheiden sich damit von den konkreten Dingen unserer alltäglichen Erfahrung, den Wirklichkeiten 1. Ordnung, denen keine wesentliche emotionale Besetzung zukommt, wie Tische, Stühle, Fenster und Fahrräder usw. Wir selbst sind die Erfinder und Hüter der Wirklichkeiten 2. Ordnung nach den Prinzipien der Autopoiese und Homoiostase. Diese Wirklichkeiten sind nicht als allgemeingültig objektivierbar, erst recht nicht durch apparative Messungen zu erfassen, sondern stellen für jeden von uns individuelle idealtypische Konstruktionen dar. Wir dürfen sie uns nicht als allgemeingültiges Abbild einer irgendwie gearteten objektiven Wirklichkeit vorstellen, sondern höchstens als ein subjektives symbolisches Konstrukt dieser Wirklichkeit. Hier ist auch auf die gegensätzlichen Theorien von Funktionalismus und Strukturalismus sowie auf ihre möglichen Wechselwirkungen etwa am Beispiel der Sprachforschung zu verweisen. Bereits an dieser Stelle erhebt sich auch die Frage nach der sog. Selbstbewegung oder Selbststeuerung, die sich der ätiologischen Erklärung und damit der Physiologie letztlich entzieht, siehe auch Kap. 2.1.2.4 Homoiostase.

Wilhelm Windelband (1848–1915) made a distinction between nomothetic and idiographic sciences. Nomothetic sciences such as B. Physics deal with generally valid and objectifiable laws of nature. The term nomothetic is derived from agr. Νόμος [nomos] = that which is allocated, ordered, distributed, the given - divine or worldly - law and from τίθημι [titämi] = to set, place, place; θετος = set. Idiographic sciences such as B. History or cultural studies deal with individual cases for which there are no such strict laws. The term idiographic is derived from ancient Greek ΐδιος [idios] = separate from the community, belonging to the individual and γράφειν [graphein] = to denote. When differentiating between nomothetic and idiographic sciences, a distinction can be made primarily - as with the intelligence models above - between spatial and primarily temporal approaches. It is not difficult to relate these distinctions to realities of the 1st and 2nd order as well. First-order realities correspond to nomothetical facts, second-order realities correspond to idiographic ones. While physiology as a natural science can explain somatic phenomena well, namely as realities of the first order, it largely fails when it comes to explaining phenomena of the second order.

The objective question about the localization of such constructs can be answered by relocating them to certain brain centers such as the association cortex, which is responsible for learned behavior and understanding of symbols. Here, however, the scientific description ends, so to speak, "in a thicket of increasingly differentiated physical functions". With these scientific answers, nothing is said about the objective comprehensibility of constructs, nothing about their use and their ability to develop ( quality problem ). These “inner maps” can, however, be made to coincide through interpersonal cooperation, for example through the method of empathetic understanding of networked relationships instead of imaging processes for the representation of organs. In this way, subjective information about the conditions for the creation of such maps can be obtained. This creates the suitable conditions for their possible redesign or further development.

Special aetiological models

Taking into account general requirements, special etiological models can only be described in the form of a selection.

Sociological concept

The sociological concept of disease was one of the first to be favored by the physiological literature of the 18th century, see Chap. 14.3.1 Psychics and somatics . Later, the prime example of these theories was the term neurasthenia . Today the designation of functional disorders has often replaced similar meanings. This shows that a change of orientation has taken place within modern scientific medicine. This traces "in a certain way the change in the focus of clinical work from short-term treatable to chronic and often insidious, degenerative diseases". With this change, the shortcomings of a purely psychopathological methodology must be considered. This method is in harmony with the scientific concept insofar as the sick patient becomes an object or a so-called 'case', "which has a more or less 'typical' accumulation of characteristic symptom constellations". This shows a certain similarity with the treatment z. B. of infectious diseases in which the cause of the disease must be localized in the individual concerned . This scientific model differs significantly from the social-psychiatric disease models, which attach considerable importance to the style of social interactions in the development of mental illnesses, especially in the doctor-patient relationship , see Chap. 5 Social Interaction .

Triadic System of Psychiatry

The so-called “multiconditional approach”, as demanded by Gerd Huber , can be seen as an alternative concept and a way out of the dilemma of diagnosing and treating functional syndromes . He represented the concept of the " triadic system of clinical psychiatry ". As far as the strict dualism of the mind-body problem is concerned, this should at least be seen as progress.

Descriptive Concepts

It is also known that the current inventory of the ICD-10 has moved away from nosological models in favor of descriptive concepts, which undoubtedly simplifies and unifies the descriptive side of communication. The question arises, however, whether this is also useful in medical practice when a nosological classification in the sense of generally justifiable therapeutic consequences has to be found despite all the welcome variety of descriptions. Description can facilitate the nosological system, but not replace it. Descriptive concepts are mainly used by psychopathological methodology.

Homeostasis

The model of personal integration represents a certain way out of an often fruitless back-and-forth between physical and mental explanatory patterns. Symptoms of illness are viewed as " attempts to compensate", i. H. as "active services of the patient's overall personality". This is intended to loosen the causal relationship between structural and functional factors, which is necessary according to the physiological explanatory model, in which the symptom is to be understood all too exclusively from the point of view of traditional (scientific) physiology. Healing from illness would therefore be an active attempt by the organism to compensate for harmful factors. Symptoms of illness would not only be purely causal consequences of damaging factors, but also an expression of this compensation process (functional point of view), e.g. B. Fever as an expression of a defense process against. Pathogens and not just as an expression of illness (purely causal consequence), which is to be combated in any case with antipyretic agents. This compensation of different trigger factors, which can cause a disturbance of the stable state of health, is therefore a self-healing process . Compensation and thus the maintenance of a steady state or a homeostasis is also the consistent creation of a stable state of health or well-being in the sense of individually determined strategies. The trigger factors for pathological changes are z. B. also to count psychosocial and cultural factors and not only directly physiologically objectively measurable influences.

Comorbidity

In connection with the compensatory performance of the organism as a whole, reference should also be made to the frequency of comorbidity, which has only recently been increasingly discussed, and of multiple physical complaints associated with functional disorders. Various disturbances acting on an organism at the same time are able to exhaust its compensatory capacity earlier. In particular, the question arises whether a phenomenologically defined similarity of complaints justifies a summary of diagnostic groups in diagnostic glossaries (ICD, DSM).

Cybernetic Concepts

Another way out of the dilemma of a lack of explanatory models is to use communications models to understand functional disorders. It is an attempt at the cybernetic clarification of the symptoms of illness. The lack of organic findings in medicine would be comparable to disruptions in the transmission of messages due to regulatory problems. A technically intact message transmission device can still be inoperable due to deficiencies in the programming. Then the fault is not a hardware fault , but a software failure . In this case, the undisturbed hardware could be compared with the lack of physical organ findings. The operational disruptions caused by faulty programs in technology can be compared in the language of psychology with disturbed or poorly trained motivations . This comparison can be made even clearer by the fact that programs are referred to as timers that plan the course of processes in advance. Our senses, with which we receive “objective” information from the environment, are mainly designed to perceive spatial shapes. This also explains the inadequate suitability of physiological models, especially in the case of subjective or psychologically conditioned trigger factors of diseases. Already Gustav von Bergmann (1878-1955) such diseases designated as "malfunction." Even Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) pointed out that the "time not an empirical concept (is) that deducted from an experience" can be. - "Time is nothing else than the form of the inner sense ..." - "Space ... (is) the pure form of all external perception ...".

Teleological Concepts

The aspect of expediency or teleology , which is viewed as relatively unsuitable as a scientific approach in the natural sciences, however, proves to be helpful and indispensable for understanding the functional syndromes. The resulting dispute between scientifically and psychosomatically oriented scientists can, as is often the case, be refuted by the fact that opposing views do not necessarily have to be mutually exclusive. U. complement each other. A discovery of meaningful connections makes z. B. an investigation of the causal relationships is not superfluous and vice versa.

Sigmund Freud represented a teleological concept with the principle of economics, see metapsychology . Teleological concepts are also considered by individual psychology and analytical psychology .

Rainer Tölle puts the relationship between functional and organic appearing disorders in the context of tendency or expediency reactions and refers to the work of Ernst Kretschmer . He emphasizes that symptoms can have an expressive and symbolic character, such as B. in hysteria , but also in other psychological abnormalities can be observed. Such reactions, sometimes assessed as pathological, would often aim at a so-called gain in disease . Biologically, Tölle establishes relationships with the dead reflex (psychogenic paralysis, twilight states , functional anesthesia, etc.) on the one hand and with the state of motor excitation ( manifest symptoms , functional seizures , functional tremors, etc.) on the other. Phylogenetically , such symptoms are z. In some cases, they can be interpreted as early primitive movements that are updated when the occasion arises and used as "appropriate". Even if they are initially applied more or less arbitrarily in dangerous and conflict situations, they would eventually become independent of the will through conditioning and thus gain an organic appearance.

Thure von Uexküll viewed these diseases, which are determined by their expressive and symbolic character and which rather take into account the communicative needs of the subject with his social environment, as a group of expressive diseases. In these, subjectively already existing uniform motives for action are represented in a symbolically understandable way through physical expression phenomena. The body as a whole represents this expressive content in a figuratively non-verbal way. However, as a result of the conflicting tension, these motives for action disintegrate into “action fragments”. In the case of readiness diseases, on the other hand, there are no specific motives for action. Own coordination of certain and possibly different or conflicting motives for action has not yet taken place. This even less mature and even less integrated and personally conscious stage of motive formation (immature disorder) distinguishes it from expressive diseases in which an already more clearly present motive is only prevented from being implemented by external social influences (more mature stage of personality development). In the case of these expressive diseases, the body symbolizes the disrupted social integration vis-à-vis the “outside world responsible” for this disorder. In the case of readiness diseases, on the other hand, there is no uniform, externally recognizable motivation to act, there are only fragments of the readiness of different organs, whose integrating interaction no longer appears to be guaranteed. These organ manifestations have recently been referred to as “ organ language ”. This indicates a lack of intrapsychic integration due to insufficient motivation. However, their expressive content is more difficult to interpret. Here the body takes on less of an expressive role as a whole within the social, rather it is the individual organs that represent and resolve the conflict of opposing moods ( organ neurosis ). It is not a social situation that is symbolized by means of physical means of expression that are easy to interpret within the social context, but the body itself represents the scene in the context of a conflict-laden internal argument.

Resomatization concept

The concept of resomatization developed by Max Schur in 1955 has proven useful in connection with the concept of actual neuroses developed by Freud in 1898, but largely forgotten, to explain the development of physical symptoms in psychosomatics , because this is differentiated from the conversion mechanism due to different prospects of therapeutic success got to.

Medical malpractice

Most of the time, overlooking an organic finding is still viewed as a “medical malpractice”. However, malpractice is a term that is no longer used in practice today. Instead, it is referred to as medical malpractice. The disproportionately more frequent overlook of a "psychological finding" is much less often assessed as a treatment error in legal practice than the overlooking of a "physical finding". But even with mental illnesses are no less serious and z. Sometimes life-threatening consequences must be taken into account. Psychological facts are often not easy to prove in court. The term “medical standard”, which is decisive in legal practice, represents “the current state of scientific knowledge and medical experience that is necessary to achieve the medical treatment goal and that has proven itself in trials”. However, the "state of scientific knowledge" is not always sufficient for mental disorders and functional syndromes. - In the literature, the lack of official statistics on medical liability proceedings is complained.

Medical standard

The diagnosis of functional disorders is time-consuming and therefore made difficult in practice by organizational regulations. Since they are carried out with the help of technical devices from the already 2. Heuristic problem can usually not be posed for the reasons mentioned above, there is therefore another fundamental problem that also affects the area of medical experience and training. As long as technical and apparatus-related services are paid better than conversation-related diagnostic measures in today's health care system, favorable social and cultural conditions cannot be assumed for the detection and treatment of functional complaints. This fact has led to the popularization of the terms already over 150 years ago neurasthenia contributed (ICD-10 F48.0) as culturally and stamped by the lifestyle of technical progress disorder, on the other hand just this concept also shows a tendency of victims to somatization , the was particularly well received by a socially integrated group of people. The partly historical aspect of device diagnostics (e.g. EEG ) and therapy (e.g. electrotherapy ) is also the subject of the psychosomatic concept of the machine paradigm .

Social interaction

If the lack of organic findings leads to intensification of the diagnostic effort, a referral from the family doctor to the specialist often appears inevitable. If this doesn't help either, admission to the hospital often turns out to be inevitable. However, the patient with functional complaints is usually discharged from the hospital without effective improvement of his complaints and without any tangible result of an objectifiable physical finding. Then the cycle turns again with other specialists and other, usually more intrusive examination or treatment procedures ( revolving door effect ). There are also z. T. iatrogenic damage, d. H. additional disadvantages caused by examinations and possibly hasty therapy decisions. The revolving door effect means the futile and time and again strained efforts of the search for an objectifiable organic or psychological finding. The unsuccessful search for a psychological finding or the futile attempts to improve alleged psychological disorders through repeated admissions to psychiatric hospitals without changing the diagnostic point of view also lead to considerable damage through the continued use of disproportionate means, e.g. B. through chronic use of psychotropic drugs. Such unsuccessful attempts are also well known as "revolving door psychiatry". The name is primarily aimed at the problem of the chronification of psychiatric suffering, which has been intensified in this way. a. the social psychiatry adopted. The cycle of referral practice is also characterized by the often insufficient knowledge of the previous history as well as the lack of knowledge of suitable psychosocial parameters, since the interest often focuses on special and ever new apparatus-based examination procedures (e.g. based on the principle of searching for a physical finding) or routine psychological treatments ( e.g. detoxification) but not focused on a paradigm shift in the search for the nosological classification, cf. Cape. 4. Medical standard .

Because of the uselessness of the described measures of a repetitive vicious circle (vicious circle) of the referral practice and because of the resulting high costs, considerations have been made as to why similar scenarios keep coming up. The point of view of social interaction seemed important. It describes the style of transference and countertransference . This means that patients often transfer negative experiences to previous caregivers into medical treatment. In this way and favored by the ineffectiveness of the medical diagnosis strategies practiced in individual cases, the transference on the part of the patient provokes a further negative countertransference on the part of the doctor. As a result, this decides on the procedure already described in Chap. 1 sample explanation mentioned "delegation of medical responsibility" by means of referral to more and more specialists or more and more hospital admissions. For his part, the doctor expects the patient to adopt a behavior pattern that corresponds to his basic diagnostic assumptions. This overall context within the health system can be understood - from a medical-sociological point of view - as a reaction to the patient's “deviant behavior” perceived by the doctor. "Deviating behavior" of the patient is, despite the best of intentions, outwardly "sanctioned" through the referred referral practice. This should be avoided by analyzing the mutual transmission between doctor and patient.

Patients not only follow certain medical strategies as a result of pressure to conform to the doctor, but conversely, medical behavior is also adapted to the patient's unspoken expectations. This can also lead to negative consequences, e.g. B. on chronic drug abuse or incorrect organ treatment according to the pressure on the patient to “act” on the doctor. This expectation can mean an expression of a repression of one's own emotional or social suffering.

From a medical-sociological point of view, the demand for the examiner to have as little prejudice as possible is also to be understood as a demand for an open anamnesis without the pressure of social expectations or the pressure to adopt the examiner's own assumptions. Such an expectation would prevent the patient from self-confident preoccupation with his functional disorder. It depends on an open dialogue , reluctance to “advisory” in the sense of therapeutic abstinence and increasing the sensitivity of the examiner, as practiced in Balint groups . These qualities of the medical discussion are of course threatened if the practice of medical assessment z. B. is exercised under time and performance pressure - and under predominantly operationalizing aspects.

frequency

Many epidemiological studies have come to very different results with regard to the frequency of functional syndromes in general. These results vary between approx. 30–80% of a general or multidisciplinary sick population, i. H. thus all observed diseases at all. Despite different results, there is no doubt that the incidence of functional syndromes is very significant. Some authors believe that the incidence of functional diseases has increased. Maria Blohmke emphasizes that, despite immense medical and scientific successes, the state of health in industrialized nations is often not better. T. has even gotten worse. This manifests itself primarily in an increase in cardiovascular diseases and functional disorders. The sickness rate increased from 1.5% to 6% between the turn of the century and 1966. This is associated with the rapid socio-cultural change of the industrial revolution .

The presumably extremely high frequency of functional syndromes not only urgently calls for further scientific engagement with the topic, but also makes the health policy debate with regard to the consequences of insufficiently recognized and therefore insufficiently treated cases for the health system appear appropriate. - The reason for the different results of the studies was obviously the selection criteria of the examined patients. Standardized selection categories were therefore developed. A distinction was made between

- a "pure" group of functional syndromes, d. H. "Without" any kind of organ disorders,

- mixed cases with only partially functional and partially organic complaints, d. H. "With" corresponding organ findings as well

- a group of “purely organically” based symptoms.

When comparing the frequency of functional and organic symptoms, it is necessary to distinguish between “purely functional” groups on the one hand and “purely organic” diseases on the other hand, and between “purely organic” diseases “without” functionally internalized complaints on the other and “mixed organic” diseases “with” functionally internalized complaints, cf. see chap. 10 differential diagnosis and chap. 14.3.2.1 The Shiverers of War . The organ diseases with functional components represent the therapeutically most serious cases because the objective assignment of organ findings and subjective complaints cannot always be secured by a doctor with strict evidential value and, on the other hand, because the assignment of organ findings to emotional facts on the part of the patient also involves great subjective Uncertainties can be burdened ( displacement , aggravation or simulation ). Deciphering this is apparently the crucial task in solving the puzzle of functional syndromes. The division into epidemiologically different groups is not only statistically, but also pathogenetically and prognostically significant, see Chap. 7. Pathogenesis and Chap. 11. Forecast . An organism that has been organically damaged does not have the same defense potential against diseases as a healthy one. Here, too, seems to be the case in Chap. 13. To confirm the thesis expressed in nosology , according to which a patient who acquires an organic condition loses his functional syndrome (theory of two-phase repression), see symptom change . From this point of view, the epidemiological importance of the genesis and physical complications of functional diseases on the statistical increase in physical diseases in old age must also be taken into account.

A differential diagnostic differentiation is also difficult, since many descriptively well-known diseases contain functional complaints, see Chap. 10. Differential diagnosis . This also makes statistical comparisons difficult.

The authors Hoffmann and Hochapfel point out that, based on a survey of all patients in a general outpatient department about functional complaints, 93.6% reported at least one functional symptom. In contrast, only 68% of a control group of healthy people reported at least one such symptom. On the one hand, this underlines the frequency of the complaints, but also the increased importance of functional complaints and accumulation in people who, for reasons that are not objectively specified, subjectively consider themselves sick (communicative aspect, symbolic and figurative expression through an occasional physical symptom language). . It can even be assumed that such a connection or an accumulation of subjective symptoms also exists with comorbidity , which further increases the unspecific subjective possibilities of expression, cf. Alternative concepts section .

Pathogenesis

Illustration of probable pathogenetic interrelationships without involvement of organic levels of integration (model after Thure von Uexküll)

Functional circle with the integration of the “subject” in the psychophysiological processes. The illustrations “interrelationships” to “ situation circle ” are to be thought of as “connected” through this common element.

The figure "Interrelationships" shows an illustration of probable pathogenetic relationships in functional diseases, which goes back to a work by Thure von Uexküll . The decisive factor here is the assumption that functional disorders and subjective perception patterns mutually reinforce each other. These subjective perception patterns mainly include individual types of experience processing such as u. a. certain fear reactions. Functional disorders are determined by a large number of possible trigger factors, which, however, do not only fall under the paradigm of psychological or physical noxae .

The fact that a pathogenetic mechanism can initially be assumed that proceeds without any noticeable physical impairment agrees with the fact that functional syndromes were initially viewed as a “only temporary” disorder. It can also be assumed that functional syndromes do not initially cause organic disorders. Later, however, these appear more and more frequently - especially in the case of chronic progressions, cf. Fig. “ Revolving door effect ” in the Social Interaction section and the Forecast section . Such chronified courses were also understood as so-called " readiness diseases ". In terms of motivational psychology, these are characterized by the fact that no suitable motives are available to change a certain suffering situation. The situation in which people with “functional syndromes” live was also characterized in terms of motivational psychology as a situation in which two opposing motivations collide with one another. In order to avoid a chronification of functional syndromes, it is therefore urgently advisable to make aware of this mostly unconscious conflict situation as early as possible and to defuse it by means of suitable solution strategies, see section Social interaction .

As already emphasized in the Alternative Concepts section , a multifactorial nosological consideration is important in functional diseases. The subjective factor obviously plays the decisive role here. The consideration of this factor is not only seen as a pathogenetic link and as a key to understanding for the patient with functional syndromes, but also generally required as a benchmark for the examiner. It is therefore important to describe various pathogenetic models that can trigger functional syndromes. With these, it seems appropriate to understand the “subject” as the interface between functional and physical syndromes, see figures “ Interrelationships ” to “ Situation circle ”. Instead of an “objective anatomy”, a “ subjective anatomy ” has therefore also been used.

The word from the internist Ludolf von Krehl (1861–1937) comes from: “It is not illnesses but sick people that are to be treated”. This principle is of great importance not only in forensic psychiatry .

The psychiatrist Frantz Fanon (1925–1961) was a staunch advocate of the principle of subjectivity . It is precisely this principle that is also to be applied in the health policy discourse that deals with the patient, see also Chap. 6. Frequency . If these principles are not observed in public, historically new problems arise which are to be dealt with in more detail in the history section .

The illustration “ situation circle ” illustrates this revolutionary reversal of perspective of the subject. While subject has a derogatory meaning in colloquial language, Thure von Uexküll described the connection between subject and object in the motivational context as follows:

“The 'opposing' means ' ob-jectum' in Latin . At the same time, the motif subjects me to the rules of the game that apply to dealing with this something. Any violation of the rules of the game would lead to a miss of the object and a failure of the plot. As a doer, I am therefore subject to the rules of the game of a motive, and ›submission‹ means › sub-jectum ‹ in Latin . "

According to Uexküll, this submission follows the regular rules of dealing with the object. Yet it is not only the object that here unfolds its power over the subject. Rather, the “frame of reference” that arises between object and subject develops into a “power to shape reality”. - Systems theorist Ludwig von Bertalanffy (1901–1972) was also concerned with this question . He speaks of "primarily active" biological systems. This means that not only the external process (the stimulus) is decisive for the reaction of a biological system, but also the internal state of the system (the willingness to react). This subjective influence of the inner willingness to react can be described with the help of the cybernetic model as a deviation from a target value or as a disturbed homeostatic equilibrium. Without a subjective need, external stimuli would not even be perceived. Our senses only make that part of the environment appear large and important to us that is essential for our practical needs.

Synonyms

Frequently used synonyms for functional syndromes, apart from the “ vegetative dystonia ” already mentioned, are in particular: vasolability, neurocirculatory dystonia, sympatheticotonia , vagotonia , psychogenic syndrome, neurasthenia , organ neurosis , vegetative-endocrine syndrome and psychovegetative disorder. The critical reservations already mentioned apply to all of these designations, cf. Cape. 1. Explanation template and chap. 2. Heuristic problems . Disease names with the addition “essential” such as B. Essential hypertension indicates a lack of organ findings. The addition " endogenous " to certain disease names such as z. B. Endogenous eczema or the older term endogenous psychosis . In psychiatry, the term "functional psychosis" mentioned in the article header is also used . It means roughly the same as endogenous psychosis, i. H. a psychosis that cannot be determined by a recognizable organ disease. However, this possibility of organic causation should be considered. However, the term does not suggest whether this psychosis is to be regarded as congenital or acquired, see also the psychiatric-historical problem of the term endogenous psychosis. Other names for certain groups of physically unjustifiable diseases are atopy and constitutional diseases . According to a suggestion by Thure von Uexküll and Karl Köhle, the term "essential" should only be used in cases of functional syndromes in which no organ changes could definitely be found (pure or essential cases) include cases mixed with organ findings, cf. Cape. 6. Frequency .

Symptoms

The symptoms of the functional syndromes can hardly be described as uniform, but rather as extremely variable and fuzzy. It can therefore be described as "paradoxical" because it contradicts the definition of a syndrome. According to this definition, a certain uniformity of symptoms is required.

The symptoms of functional syndromes range from relatively precisely localizable somatoform disorders to diffuse and vague feelings of depression. A clear demarcation between physical and mental complaints is therefore hardly possible. This lack of delineation is particularly evident in symptoms such as dizziness , general insecurity and tremors , palpitations , heart sensations, tendency to sweating , fatigue , insomnia , globe feelings , ill-defined paresthesia and mood lability . Even if one tries to qualify these symptoms as vegetative, in functional syndromes the mostly rapid change in symptoms ( symptom change ) is rather uncharacteristic of vegetative disorders.

The organ complaints, which are sometimes intensely complained by the patient, often lead to the wrong organ-related conclusions, see the keywords "single-line causality" or "monocausal approach" in Chap. 1. Explanation pattern , "Defects in psychogenic model concepts" in Chap. 2.1. Alternative concepts and “pressure of expectation” in Chap. 5. Social interaction .

In addition to the tendency to change symptoms, the relatively large number of complaints can be regarded as characteristic of the presence of a functional syndrome. An organic genesis is rather unlikely in this case. The long duration of the complaints without specific indication of the beginning of these complaints is also to be regarded as pathognomonic .

According to a statistical study of the urban population (random sample), the ten most frequently complained of “psychogenic complaints” also include five functional disorders such as the following: general inner restlessness , tiredness and exhaustion , headaches , concentration and performance disorders, and sleep disorders .

It often happens that relatives and acquaintances suffered from symptoms similar to those with which the patient identified . Taking a history can be quite difficult because the patient is trivializing significant events in his life. Disposing factors in the form of early pathogenic interpersonal relationships are well documented in literature. It can also be seen as "paradoxical" that certain otherwise stabilizing factors in the family structure are having a disastrous effect here. A rigid and cohesive character structure and an overadaptation appear to be characteristic.

- Thus, the tendency to become chronified, together with a relatively rapid change in the various complaints in a cohesive family structure, appears to be typical. Paradoxically, the “typical symptoms” are characterized by a low specificity.

Differential diagnosis

The following diagnostic differentiation criteria result from the above statements:

- Querulatory character development (ICD-10 F68.8) and querulatory delusional disorder (ICD-10 F22.0): Functional disorders must be taken seriously with regard to the possibly poor prognosis and must not be character-related or due to the lack of organic findings be seen as less of a personality variant to be taken. The “diagnosis-centered” view of a functional syndrome can be supplemented by a “personality-centered” view. However, both approaches are not mutually exclusive.

- Dissociative disorders (ICD-10 F44.-): Functional syndromes are common here. However, the character-related objections as mentioned in the previous point apply.

- Acute emotional stress reactions (Freud's current neuroses) with a good prognosis (ICD-10 F43.1): Functional syndromes are common here and represent, so to speak, the easiest initial stage of the disease.

-

Somatoform disorder (ICD-10 F45) with subgroups: The somatoform disorder overlaps e.g. Sometimes with the functional syndromes, but must be differentiated from them because of the body-related issues required by definition (body-soul dualism). The somatoform disorder presupposes that “real physical complaints” can be ruled out, while the functional syndromes in the advanced stage can definitely contain complaints about “real physical complaints”, see the information in Chap. 6. Frequency named epidemiologically “mixed” group. - In contrast to the somatoform disorder, functional syndromes are not limited to somatic complaints, but often show a “psychogenic expression”, which can e.g. B. relates to the general condition.

- Hypochondriac reactions and developments (ICD-10 F45.2) as an example from the somatoform subgroups: The above criteria for distinguishing somatoform disorders also apply here, because the “psychogenic expression” in functional diseases must be taken into account. Differentiation is more difficult if the functional syndromes to be suspected have no objectifiable organ findings (“pure group” see Chapter 6. Frequency ) and the lamentation is not “psychogenic”. In the case of functional syndromes, however, actual organ damage in the course of the chronification, in contrast to the hypochondriac disorder, can be assumed. Hypochondria is also often viewed as a character disorder. The differential diagnostic considerations mentioned in relation to the first point, "Querulatory character development", also apply here. The ICD-10 points out that lamentation in hypochondria is fixed on one or two diseases, while in somatization disorders and thus also in functional syndromes it is variable and symptom-related. Stavros Mentzos refers to the defensive mode of introjection and projection into the body that is characteristic of hypochondria. Rainer Tölle emphasizes that overlaps with functional syndromes are inevitable in the hypochondriac processing mode.

- Neurosis (nosological differentiation): See chap. 14.3.2 Neurosis and functional disease .

forecast

The prognosis is also to be seen as a “paradox” - similar to the one in Chap. 9. Symptoms described disease characteristics, since the initially often trivialized functional complaints "without organic basis" can show a clear tendency to worsen and even lead to a significant excess mortality. Polysymptomatic forms of functional complaints act as less mature disorders and therefore have a less good prognosis than monosymptomatic ones. Comorbidity and polysymptomatic manifestations are to be viewed as an additional stressful circumstance, as if the experience of individual disorders or symptoms add up in terms of their disease value.

In the above-mentioned publication “From Emotion to Lesion”, the psychosomatic downward effect is already expressed in the title of the work. Ultimately, this downward effect often manifests itself in physical damage. This at least suggests the prognosis of the functional syndromes. Of course, this does not mean that only “psychologically” or “emotionally” caused effects are possible in functional diseases. Acquired dispositions and inherited constitutions can combine in the form of functional syndromes. Physical disorders that have occurred once can repeatedly become noticeable as a "weak point". Then one speaks of “fixed suffering”. Learning effects also play a role here, as do physical examinations that are carried out for too long.

An "essential high blood pressure" which has not been sufficiently recognized nosologically, e.g. B. leads in the worst (untreated) case to the dreaded complications of high pressure, such as kidney damage, stroke and heart attack due to increased vascular sclerosis. If the cause of this hypertension is not recognized, long-term symptomatic treatment with medication is only possible while accepting the medication side effects associated with it to a certain extent. In practice, all transitions from mild, non-fixed hypertension d. H. Incessantly persistent increase in blood pressure (degree of severity I according to Duncan) up to severe d. H. Fixed, progressive, malignant hypertension (Duncan's grade IV) known.

If no nosologically applicable explanatory models are recognized and treated therapeutically in a meaningful way, then, as a rule, a continuous deterioration and chronification of the symptoms must be expected. Originally, functional syndromes were only defined as variable and non-fixed symptoms. Today they are also seen as the cause of chronic - especially physical - damage.

therapy

As already in Chap. 7. If pathogenesis is carried out, it is necessary to search for opposing motives for action as the cause of functional complaints. Therapy therefore begins with taking the medical history. The technique of taking an anamnesis must therefore also be characterized by a “multiconditional approach” (asking “open questions”), so as not to ask a certain idea of the examiner into the patient and to give him the opportunity to express his own subjective Developing representation of these complaints. Gerhard Buchkremer also understands the concept of “multidimensional psychiatry” as an approach to multidimensional therapy. However, as already mentioned, this is a lengthy process and cannot consist of a diagnostic process for excluding organic findings. The possible "disappointment" of a patient who is fixated on the finding of an organic finding must be made the subject of a mainly "trust-building" therapeutic relationship, in which negative "transferences" but also "countertransference" are made the topic of the conversation, see chap. 5. Social interaction .

Nosology

If one assumes a strict concept of illness that only relates to physically justifiable disorders of health, then one finds oneself in the one already in Chap. 8. Synonyms called dilemma of endogenous psychoses. Functional syndromes, however, are the example par excellence that speaks in favor of expanding this strict concept of disease. The concept of nosology , which comes from pathology , can only be used to a limited extent in psychiatry. There is no doubt that physically justifiable units of illness also have their place in psychiatry. But when it comes to the whole, the unity of the symptoms of illness, only "life itself" can be the yardstick for a systematic classification of illnesses. Everyday practice in life shows that functional diseases are of very serious importance in all of medicine and that this validity is not only required in psychiatry. Please refer to the explanations in Chap. 1. Explanation template referenced.

The “somatoform autonomic dysfunction” (F45.3) contained in the ICD-10 represents a diagnostic category that is not listed in a comparable form in the DSM-IV . The authors Hoffmann and Hochapfel, who have examined the nomenclature of the ICD-10 in detail, are of the opinion that functional disorders correspond most closely to the somatoform autonomic dysfunction categorized under ICD-10 F45.3. These authors have even set up their own model, according to which the vegetative disorders named in this category in the ICD are to be viewed as a kind of intermediate station on the path of symptom formation from the conscious or, more often, unconscious affective state of tension to the diverse dysfunctions of functional syndromes. However, it should be noted critically that this is a physiological model and not a psychological explanatory scheme. With such physiological models, the individual processing of affects on “deeper” physical (vegetative) levels of integration can be mapped and explained, but not the type of perception of the outside world or second-order realities (expressive character). According to Alexander Mitscherlich's concept of “two-phase repression”, psychological processing is primary and precedes physical symptoms. Conflicts that are only relatively incompletely repressed lead to neurotic disorders of various kinds, which are also associated with functional syndromes. Only when the repression continues, permanent physical symptoms take the place of neurotic mental defenses and functional complaints.

Thure von Uexkull considers this idea important, since it is able to build a bridge between different groups of diseases by placing them under the common point of view of repression. It says that with increasing completeness of the repression of conflict-laden motives, on the one hand, fear decreases, while on the other hand, the severity of physical phenomena increases. These ideas are based on a concept by Sigmund Freud . He spoke of conversion and meant a mechanism for hysterical conflict management. Here the excitement of an incompatible idea is converted into the physical. In this way the fear disappears, which arises with the danger of affect-laden motives breaking into consciousness.

Max Schur took a slightly different view with his concept of de- and resomatization. In doing so, he put the focus on the child's normal development. This consists in the fact that a fixation on certain organ systems with the psychological maturation of the personality fades into the background (desomatization). In crisis situations, however, this development declines (regression), so that there is a renewed affective body reaction that is symptomatic (resomatization).

history

The treatment of the history of psychiatry in the context of the functional syndromes appears significant because in this way too - in a historical representation - the above in various chapters. The question of the differently assessed causal and conditional relationships in the expression of functional syndromes in historically different temporal currents is to be clarified. This historical investigation also points to the significance of functional syndromes, which has been neglected until today, which unfortunately has led to frequent social contradictions.

Antiquity

Hippocrates of Kos (approx. 460-370 BC) saw the soul as part of the human body and located feelings in the brain. Therefore one can consider him as the first advocate of a " neurologizing psychiatry " or a psychophysiology , see also the question of a psychological localization . Even the ancient doctors of the first Christian century such as Aretaeus (around 80–135) or Galenus (around 129–216) interpreted the connection between mental alterations and an organ disease such as B. pneumonia as a consensus (dt. = Agreement, agreement) or as sympathy . This latter term was also used by romantic medicine of the 18th and early 19th centuries, see also Chap. 14.3.1. Psychics and somatics . The views of the psychics are reminiscent of the teachings of ancient authors in other ways as well. Rules for dealing with the mentally ill were first formulated by the Roman encyclopedic author Aulus Cornelius Celsus in the 1st century AD. This also reflects the later dialectic of the disputes about the use of coercion in the treatment of the mentally ill, which was taken up by the psychics. In “De re medica” Celsus describes the treatment of mania and melancholy. He also describes various possibilities of psychological influence, such as For example, in a negative sense, the wholesome lie, the wholesome pain and the wholesome horror, in a positive way, the wholesome distraction and the wholesome conversation as well as the empathic approach to the patient. This list already contains later contradicting positions in the history of psychiatry. Galenus (around 129–216) already recorded the functional aspect of diseases by speaking of Functio laesa as a symptom of inflammation .

middle Ages

In the Middle Ages, the influence of church teaching on dealing with the mental states that are now regarded as medical illnesses was predominant. It should not be denied that many monasteries and other ecclesiastical institutions treated the mass of needy people therapeutically in today's sense. B. The Alexians and the Brothers of Mercy . However, moralizing or marginalizing church tendencies should also be pointed out. Slogans such as the hunt for witches and warlocks, the possessed, the fiends and evil magicians may suffice here. The ecclesiastical organization of dealing with the problem of emotional distress and behavioral problems took place e.g. Partly by exorcising priests and by methods of the inquisition, the burning of witches , persecution by the Dominican order and the bull Summis desiderantes affectibus of Pope Innocent VIII of December 5, 1484. Secular countercurrents are already to be mentioned here. By doctors like Paracelsus (1493–1541) and Johann Weyer (1515–1588) u. a. in the outgoing MA with word and deed, at least a rudimentary support was also given to the sick in public.

Modern times

In the age of secularization , it was the state that created the a. had to take over the tasks of caring for the army of those in need that had been taken over by monasteries, since these monasteries were now dissolved. The state treatment of the sick and the way they dealt with them was perhaps less of a threat to their existence overall, if not less exclusionary. In 17th century France there were still decisive absolutist measures to exclude social misery, such as B. by decree of King Louis XIV of the "renfermement des pauvres" in May 1657 ("inclusion of the poor"). The literally poor lunatics were housed in beggar prisons, which bore the euphemistic name " Hôpital général ".

In Germany such institutions were called “prison”, in England “workhouse”. The z. The sometimes hidden moralizing character of these treatment methods is already striking in the name of the accommodation. In the German name, however, this moralizing character is formulated more clearly and openly than in France. In Germany people tried to get closer to the problem of psychological suffering through education . A moralizing aspect in the public discussion of the problem of the mentally ill is still expressed in the dispute between psychics and somatics.

Psychics and somatics

In the dispute between " psychics and somatics ", as it was conducted in the first half of the 19th century and z. In some cases, it continues to the present day, it is about the serious moralizing and demonizing practice in dealing with the mentally suffering, which until then was practiced in the public discussion and practice in the negative sense, see Chap. 15.2 Middle Ages . Significantly, in Germany the expression “psychic” does not mean the psychologizing, but the “ moral treatment ” in the positive sense, while in France the “moral” rather expresses the psychological side, corresponding to the more subjective-mental evaluation this term has not only adopted there since ancient times. The principles of moral treatment, which was mainly introduced in Western Europe, are also reminiscent of the methods handed down by the ancient author Aulus Cornelius Celsus for dealing with the mentally ill. The psychics, mainly represented in Western Europe, considered mental illness to be an expression of the disembodied soul. The views of Johann Christian Reil differed from this, however, already very substantially, even if he took up individual thoughts of the psychics. Reil already took the view of the somatic nature of mental illness. In accordance with the philanthropic principles of the Enlightenment, moral treatment is softened compared to the radical forms of the church's moralizing claim to power, even if religious exercises were an integral part of the educational program. This program also consisted of gracious personal care, occupational therapy , dieting , amusements, games, music-making, physical exercise, study, recreation, gardening, and agricultural work with no coercion . The moralizing treatment advocated by psychics has a certain relation to modern social-psychiatric treatment concepts as well as to the ideas advocated by Freud . As early as 1900, support for community-based institutions began in England and other countries. This makes the social worker an integral part of psychiatry. This was all the more a reason for the controversy between science-oriented medicine ( classic German psychiatry ) and the more recent methods of Freud or social psychiatry , see Chap. 2.1.2.1 Sociological concept .

The "somatics" firmly demanded the priority of medical treatment on the basis of the new scientific knowledge. These were primarily based on the advances in anatomy since the Middle Ages. Here are u. a. Names like Mondino dei Luzzi (1275–1326; fig. ), Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), Miguel Serveto (1511–1553) and Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) should be mentioned. This anatomical knowledge was gradually expanded into physiological knowledge, i.e. H. knowledge of the functions of the organs. The function of the nervous system was given a decisive role very early on. So have Robert Whytt (1717-1766) and William Cullen (1710-1790) transferred this idea not only to psychiatry ( "Neurologisierung psychiatry"), but almost the whole of medicine and therefore as an early representative of the spirit of the psychosomatic medicine be considered. This although the term "psychosomatic" comes from the camp of psychics, namely from Johann Christian August Heinroth (1773–1843). The somatics relied on the work of Georg Ernst Stahl (1659–1734) and Albrecht von Haller (1708–1777).

The clinician and chemist Georg Ernst Stahl can be seen as the originator of the “functional idea”. He distinguished between “ sympathetic ” and “pathetic” mental illnesses, see Chap. 15.1 Antiquity . According to Stahl, the former are caused by disease of organs, the latter represent functional disorders without organ disease. If one translates “sympathetic” with “sympathetic”, then the organic mental diseases are only the result of the mental state of affairs caused by the disease of the organs. In addition to Stahl, there were numerous other contemporaries in Germany who already represented a psychogenic (“pathetic”) cause of mental illness and thus separated them from the purely organic view. B. Christian Gottlieb Ludwig (1709–1773) and Johann Gottfried Langermann (1786–1832). At that time, philosophical idealism triumphed in Germany. According to Wesiack, Thomas Sydenham (1621–1689) before Stahl had already drawn attention to similar psychogenic illnesses in a letter in 1681, which, through their “proteus and chameleon-like” character, imitate other organic illnesses. They are extraordinarily frequent and make up over half of his non-febrile patients. According to Ackerknecht, Sydenham, in his letter to Dr. Cole described the diversity of these forms of hysteria in 1680. However, not Sydenham, but Thomas Willis (1621–1675) together with Charles Le Pois in 1618 was the first proponent of the idea that hysteria was not a disease of the uterus, but of the brain. In France, J. E. D. Esquirol (1772–1840) had already drawn attention to the functional aspect of mental illnesses, which can be determined in connection with the progressive progression from functional to organic disorders, cf. a. Cape. 7 pathogenesis .

The above-mentioned Johann Christian August Heinroth (1773–1843) as well as Justinus Kerner (1786–1862), Karl Wilhelm Ideler (1795–1860), and Carl August von Eschenmayer (1786 ) were representatives of the educational concept of the psychics working mainly in Germany -1852). Demonic ideas of the ghostly immaterial soul won with them z. Sometimes the upper hand again over the purely caring thoughts with regard to the psychological suffering. On the other hand, the Enlightenment, especially in Germany, and especially that of Immanuel Kant, should not be forgotten, who emphasized the role of duty in distinguishing between irrationality, inclination and passion and thus encouraged self-reflection rather than action based on the conviction of political maturity. This attitude naturally increased the isolation of the mentally suffering. Whether philosophical idealism or philosophy of the Enlightenment, the somatics naturally saw themselves compelled to represent their point of view also in relation to philosophical theories. It goes without saying that this was initially done in the sense of differentiation from traditional views. The scientific idea was new and first had to lead to an overemphasis and an absolutization of scientific causal theory and inductive methodology . Such absolutizations led to the misinterpretation of psychosocial and cultural factors and made the somatic thought u. a. susceptible to the doctrine of degeneration . However, this in turn can already be viewed as an adaptation to the contemporary philosophy of pessimism .

The somatics won the controversy in Germany and England between the priority of physical (physical-organic) and psychological (emotional) points of view in a certain way to this day. In England, doctors are called "physicians", even if they deal with mental issues. This does not rule out that exclusionary and moralizing aspects are still noticeable in dealing with the mentally ill and that the state still plays a decisive role in the psychiatric health system.

The fact that this phase of the conflict in Germany ended abruptly around 1850 with the success of the neurological localization of psychological abilities in the brain cannot hide the fact that this outcome, as already indicated, has its downsides through the absolutization and ideologization of the somatic thought. The phase of Neurologisierung psychiatry followed for different reasons different currents of Repsychiatrisierung . When the triumphant advance of the basic physical-neurological assumptions about the triggering and causation of mental illnesses began to emerge from 1850, the opposite development was already becoming apparent. This did not consist in the neurologization of mental illnesses, but, conversely, led to a psychiatization of the neurological constructs that had previously been painstakingly acquired and recognized. These achievements were at least partially lost. The z. B. the new psychological reassessment of the term neurosis and, with it, the term neurasthenia , which was at times very widespread , made this clear. Individual points of view should therefore be mentioned that have led to internal contradictions even into our time.

Neurosis and functional disease

Similar to the dispute between psychics and somatics, there has also been a public debate on the subject of neurosis and functional diseases . If earlier advocates of the neurological view of mental illness took a progressive stance called "neurosis," it has now become a tool of repressive politics.

The war tremors

In the context of functional diseases, a comment on the term neurosis coined by Cullen (1710–1790) , as it is used in today's sense, appears. Klaus Dörner points out that the term neurosis, introduced by Cullen, retained its meaning for over a hundred years as a disorder of nerve function without any recognizable gross and visible structural damage. Then he lost his relationship on his nerves. As the reason for this, Dörner states on the one hand that neurology became independent and that psychological concerns became more and more of a minor matter. On the other hand, the term neurosis has been "internalized psychologically" (internalized). The separation was by no means favored by Sigmund Freud (1856–1939). Freud always kept the psychological and anatomical topics in mind. - Rather, it was state interests that opposed the neurological view of the term neurosis. The reason for this was the problem of the war tremors . At that time, many soldiers reacted to the increasing mechanization of warfare with the symptom of trembling.

However, for reasons of supporting the state finances, this symptom should not be recognized as an illness. Rather, it served the interests of the state not only in Germany but also in other warring countries to strengthen the ideology of the will to defend themselves. For this it was necessary to label the soldiers affected by this symptom as "pension hunters" and thus in the scientific sense as "neurotics". Those affected had a psychological adjustment disorder attested to which no organic basis could be assigned. This has been propagated as scientific knowledge, which is one of the most illuminating examples " of the sociological and political interweaving of the knowledge process in psychiatry ".

Also Thure von Uexküll describes such contradictions related to the Kriegszitterern. If one defines illness as the result of an anatomical change, then there is no other option than to distinguish between “real” and “false” illnesses in the case of war tremors and many other illnesses. In the case of the war tremors, this was done in a less offensive manner by speaking of “organic” and “functional” diseases. But only the former, which showed an anatomical change in an organ, were considered to be conditions that deserved pity and medical attention. The others, with only a functional disorder, i.e. a physical performance, but no anatomical organ change, were suspected of being simulated for unfair reasons. Uexküll continues:

“It deserves to be recorded how, on the basis of an obviously wrong theoretical assumption, one came to a wrong assessment of sick people, an assessment which, due to its moral accent, was to have a particularly negative effect as a result. Because these things still play a significant role today in the resistance of the general public to allow the possibility of emotional causes for physical suffering. "

Gesine Küspert connects the history of functional syndromes with the description of neurasthenia . She writes that this disease was discovered in 1869 by the American doctor George Miller Beard and that it fulfills all the definition criteria of functional syndromes. She notes that there have been reports and speculation of cases of neurasthenia during the two world wars. Most of these cases were classified as "Shell Shock Syndrome" or "War Neurosis". Many doctors also referred to the soldiers' mysterious illnesses as "neurasthenia". From 1900 to 1920, in the course of the further development of psychology and psychoanalysis, neurasthenia was reinterpreted as a mental illness. The psychological labeling had sealed the decline of the disease term neurasthenia.

The hysterics

While the problem of the war tremors mainly affected men, hysteria is a phenomenon that has been attributed mainly to women since ancient times. This is already suggested by the name hysteria, which is derived from ancient Greek ὑστέρα (hystera) = uterus .

Sigmund Freud was best known for his early writings on hysteria. His psychoanalytic method began with the treatment of these patients. Hysteria is the more mature form of conflict processing than z. B. in hypochondria.