Brigantium

| a) Ölrain Fort, b) Oberstadt Fort, c) Steinbühel Harbor Fort d) Leutbühel Harbor Fort |

|

|---|---|

| Alternative name |

a) Brigantion ; b) Brigantium ; c) Brecantia ; d) Brecantio ; e) Brigantio ; f) Bregancea ; g) Breganceo |

| limes |

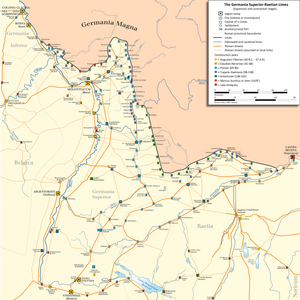

Raetien , Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes , route 3, Raetia prima |

| Dating (occupancy) |

a) Augustan or Tiberian, abandoned in the 1st century AD, b) Diocletian?, 3rd to 5th century AD c) Augustan-Tiberian? 1st to 4th century AD? d) Valentinian, late 4th century AD to early 5th century AD. |

| Type | Cohort and fleet fort |

| unit | Numeri barbaricariorum ? |

| size |

a) 2.74 ha b) 1.2 ha c) unknown d) 0.35 ha |

| Construction |

a) wood-earth, b) unknown, c) unknown, d) stone |

| State of preservation | not visible above ground |

| place | Bregenz |

| Geographical location | 47 ° 30 '18 " N , 9 ° 44' 57" E |

| Previous | Fort Arbon (west) |

| Subsequently | Isny Fort (north) |

Brigantium is the collective term for several Roman castles and the associated civilian settlement in the area of the state capital Bregenz , state Vorarlberg , district Bregenz in Austria .

After the occupation of the Lake Constance region around 15 BC. BC the Romans founded a wood-earth camp with an associated vicus on the area of a Celtic oppidum (Ölrain plateau) . So far it is the oldest Roman fort that could be proven in Austria. After this fort was closed in the course of the 1st century AD, the camp village developed into a town-like settlement that soon advanced to become an important traffic junction and trading center in the Lake Constance region. There was probably another fort at Steinbühel in the 1st century AD, which served to protect the harbor. A large number of excavated military equipment testify to the presence of Roman soldiers in Bregenz.

In the late 3rd century the Ölrain was abandoned and the focus of the settlement shifted to the smaller, but easier to defend hill of today's upper town (old town). After the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes had been cleared , the city again held a key position in the Roman border fortification system in late antiquity - due to its strategic and easily accessible location. The port fort on the Leutbühel, Brecantia , built under Valentinian I , was part of the late antique Danube-Iller-Rhine Limes and a base of a naval unit of the Roman border troops. It was possibly manned by regular Roman soldiers until the early 5th century AD.

Also worth mentioning is the large Roman burial ground on Ölrain, which was documented from the 1st to the 5th century AD and provides insights into the changes in everyday life in a typical Roman provincial town over a period of almost 500 years.

Surname

The place name is possibly derived from the Celtic tribe of the Brixenetes or Brigantier, who belonged to the ethnic group of the Vindeliker . The geographer Strabo mentioned the place around 30/20 BC. As a brigantion . He also appears in the

- Tabula Peutingeriana , at

- Claudius Ptolemaeus , im

- Itinerarium Antonini and in the

- Vita of St. Gall by Walafried Strabo .

In the vita of the missionary Columban of Luxeuil , the place is called Bricantia .

Location and topography

The location combined the advantages of a natural fortress and as a junction of two long-distance routes from today's Switzerland to the east and from the Danube up the Rhine Valley to Italy and as a seaport. This multiple role in through traffic has characterized the place since pre-Roman times, as various finds prove. Bregenz is located on the eastern shore (northeast bay) of Lake Constance , directly on the slopes of the 1063 m high mountain range of the Pfänder . The topographical conditions offered the best conditions for the construction of a large-scale settlement in an elevated position. To the north of the city, the Pfänder reaches almost to the lakeshore (the narrowest point is the so-called Bregenz Klause) and thus shielded the ancient settlement from the north. In the south, the marshes on the banks of the Rhine estuary at Rheineck / Altenrhein and the wild waters of the Bregenz Ach protected the settlement from enemy attacks. In ancient times, the lake reached up to the slopes of the Ölrain, which made large-scale settlement of the bank areas considerably more difficult or impossible.

The location of the late Celtic oppidum mentioned by Strabo is still unknown. It is believed to be on a terrain spur north of the old town hill. The Roman settlement activity was concentrated on three points:

- At the beginning, the Ölrainterrasse was settled on approx. 50 ha, which rises approx. 34 m above the lake. It formed during the melting of the Ice Age glaciers between the basement mountains on the Gebhardsberg, the remainder of the Rhine glacier north of the Inselberg Riederstein and a larger mass of ice in today's Feldmoos. This zone was filled in over the millennia by gravel and sand deposits from the Bregenzer Ach. In the north and east, the terrace slopes steeply towards the lake shore. In the south it runs flat to the slopes of the Pfänder. The foothills of Gebhartsberg, Rieder Sporn and the riverbed of the Bregenzer Ach border the Ölrain in the west.

- The late antique settlement, the 1.2 hectare moraine hill of the upper town, still dominates the cityscape today. It was once separated from the Pfänder massif by washing away by glacier melt water and forms a prominent elevation in the landscape. The Thalbach flows around it in the west and the Weißenreutebach in the east.

- The ancient harbor district was located at the so-called Leutbühel, today's city center at the foot of the upper town.

The area west of the Arlberg up to Lake Constance and some neighboring areas in the north were part of the city territory of the late antique Brigantium . The southern Lake Constance area belonged to the Raetia province , established in the 1st century AD , and from the 4th century it was administratively divided into two halves ( Raetia I and Raetia II ). The region around Bregenz probably fell to the Raetia I with its capital Curia . This was part of the Diocese of Italia Annonaria , Prefecture of Italia .

Road links

Brigantium assumed an important position in the road routes originally laid out according to military and strategic requirements as a north / south or east / west traffic junction in Innerratia and a link between Italy, Germania on the left bank of the Rhine, Gaul and the Danube provinces.

This is also underlined by its mention in the Tabula Peutingeriana on the route Milan / Mediolanum - Chur / Curia - Clunia / Feldkirch - Kempten / Cambodunum - Augsburg / Augusta Vindelicorum .

The road branched off here into the foothills of the Alps, heading west, to Arbon / Arbor Felix - Pfyn / Ad Fines - Kaiseraugst / Augusta Raurica - Windisch / Vindonissa and southern Gaul . In the Severan period (around 201) the road connection Augsburg – Bregenz was fully developed.

Research history

It has been known since around the middle of the 19th century that the Ölrain Plateau was once the site of a Roman town. In the course of the construction of houses and villas, wealthy homeowners arranged for the first excavations to uncover Roman building remains. From 1864 onwards, the then largely undeveloped plateau and some areas in the upper town were examined for the first time from an archaeological perspective by the textile manufacturer Samuel Jenny , who originally came from Switzerland . During these excavations, which were carried out very carefully for the methods and level of knowledge customary at the time, the remains of three ancient stone buildings and individual sections of the Roman route of the Alpine Rhine Valley Road came to light. Jenny, from 1875 also curator of the kk Central Commission for the Preservation of Monuments and from 1877 until his death in 1901 chairman of the museum association, was soon able to present the first summarizing essays on Brigantium's topography on the basis of the results obtained. Researchers who were later active in this area also used his work. John Sholto Douglas (1870) and the National Museum Association, founded in 1858, did their best to catalog and properly keep the excavation finds. After Jenny's death, Karl von Schwerzenbach continued his work. From 1911 to 1913 he succeeded for the first time in discovering Roman wood-earth constructions from the earliest Roman settlement phase. He also examined the burial ground and commissioned the inventory of the museum's holdings. His inventory registers later made it possible to record 90% of the finds from the burial ground since 1847.

After the First World War, Adolf Hild , who had been a museum curator in Bregenz since 1907, carried out investigations on the Ölrain. In 1925, when a bank building on Anton-Schneider-Straße u. a. the course of the ancient lake shore can be reconstructed. Schwerzenbach died in 1926 and Gero Merhart von Bernegg took over the management of the excavations. From 1940 he was replaced by Adolf Hild again, and at his instigation, the excavations at Ölrain and in the upper town were intensified due to the rapidly advancing overbuilding. His diary entries are particularly valuable, in which he noted the connections between findings in great detail. It was he who drew up the first general plan of the cemetery in 1929.

From the 1950s, the new director of the Landesmuseum Vorarlberg , Elmar Vonbank , headed the excavations in Bregenz. In 1954 the remains of the Roman port were cut during excavations in Kaspar-Hagen-Strasse. During construction work in the pedestrian passage at Leutbühel from 1968 to 1969, the remains of the late Roman port facility and the associated small valentine fort were discovered. However, they were only examined more closely by Christine Ertel in 1999. Controversial from research to the last, the archaeological evidence of the oil refinery was obtained in 2010 in the course of a rescue excavation by the Federal Monuments Office. The excavations in 2009/2010 on the Böckleareal (former UKH) in the west of the Roman settlement area brought seven successive settlement phases to light both south and north of the Roman main road. These were the first investigations carried out in Bregenz from a stratigraphic point of view. Findings and finds were processed at the University of Innsbruck. The excavations were under the direction of Maria Bader and were carried out in cooperation with the Austrian Federal Monuments Office. Above all, the settlement layers of the stone construction phase and also the wooden half-timbered construction phases below were examined. These excavations only took place on an area of barely more than 0.5 hectares and only covered the edge areas of the oil drainage deposit. As to the total size of the military installations erected under the emperors Augustus and Tiberius, as well as their exact dimensions, but also questions about the origin and strength of the troops stationed there, we can still only guess.

Since June 2017, the remains of Roman buildings in Bregenz can be viewed in the city map in the "Roman Bregenz" menu. Karl Oberhofer, Andreas Picker and Ursula Reiterer updated the results of all excavations up to the end of 2016 and took care of their georeferencing. The Roman city map was redrawn on a digital basis and incorporated into the city's geographic information system (GIS). Additional information about the individual objects can also be called up using the maptip function. Bregenz thus takes on a pioneering role among the provincial capitals of Austria.

Find spectrum

The earliest settlement finds in the urban area on Kennelbacher Strasse, on the edge of the Ölrainterrasse towards the bank of the Bregenz Ach, date from the early Bronze Age. The finds from the civil town go back to the Claudian period.

A special gem of Celtic culture is a 1.03 × 0.84 × 0.17 m sandstone relief of the horse goddess Epona (or Rhiannon ) found in the old town of Bregenz , which, however, dates back to Roman times (2nd century AD) .) originates. The finds of a fragment of a monumental statue as well as four small bronzes depicting Mercury, Mars, Victoria and a “philosopher” are also worth mentioning. The so-called Drususstein, one of the oldest Roman inscriptions in the area of the former province of Raetia, also came to light in the upper town. The 0.92 × 0.81 × 0.27 m large sandstone block was probably carried off to the upper town hill as building material ( Spolie ) in late antiquity . The inscription was made in honor of the son and designated heir to the throne of Emperor Tiberius , Drusus Caesar , and probably dates from the years 14 to 23 AD. a. Remains of mosaics have been preserved. Due to its location on an important trade route, considerable quantities of southern Gallic terra sigillata (Dragendorf, Dechelette, Knorr, Curle types) were also found. The cultural connections between the townspeople could be traced back to the townspeople with the help of the robes. A deposit of 100 specimens is remarkable, the traces of fire indicate that it was probably burnt in the ground around AD 69. An exceptionally well-preserved find was on the Böckleareal , it was a wooden construction that was probably once part of a street substructure. It essentially consisted of a grid made of square wooden beams and boards attached to it with wooden dowels and iron nails. A small section of this wooden floor could already be observed in 1912 on the property to the east.

The numerous coins found on site from different periods were important for dating the settlement phases. In 1880 a hoard was discovered in Lauteracher Ried, which included silver jewelry, two brooches connected with a chain, two rings, a bracelet and three Celtic and 24 Roman silver coins from the time of the Roman Republic (100 BC). Presumably around this time it came into the ground as a “bog sacrifice”. It is an important testimony to the pre-Roman money circulation in the area around Brigantium. When comparing the coin finds from Bregenz with the neighboring regions (Upper Germany and Rhaetian Alpine Foreland) it became clear that their circulation decreased again noticeably from the middle of the 2nd century AD. This continued in Severan times and in the era of the soldier emperors. Mintings up to 288 were mainly on the Ölrain, coins from the 3rd and 4th centuries were rarely found there. Issues after 293/294 increasingly came to light in the Upper Town. An unusual accumulation of coin finds occurred between 337 and 361, then the currency in circulation fell again significantly, perhaps also because of the steadily falling material value of the coins.

A shield hump, bronze fragments of belts (cingulum) , a fastening hook designed as a snake with a ram's head for chain armor, a spearhead, an early imperial iron dagger (pugio) , a representation of Hercules made from blue glass in The shape of a phalera , niello-embellished belt plates, fragments of scabbards and weapons as well as a sling lead (glans) . The latter in particular are typical finds in Augustan and Tiberian camps north of the Alps. Furthermore, three iron crest mounts for helmets of the Weisenau type were found.

A throwing ax ( Franziska ) and a bronze belt buckle were found from the early Middle Ages .

development

Pre-Roman times

From the Neolithic period, approx. 8000 BC. BC, the first people are likely to have immigrated from the north, along the shores of Lake Constance and from the west via the Walensee furrow into the Rhine Valley. Individual finds in the Bregenz area testify to this early phase of immigration. Finds of settlements from the Early Bronze Age at the foot of the Gebhardsberg reveal the first human settlements in this region from 1500 BC. Capture. Since the 6th century BC The Celts residing there were carriers of the Latène culture, which was widespread in Central and Western Europe. Around 400 BC BC Celts from the Vindeliker tribe settled in the north of Vorarlberg. From approx. 500 BC The oppidum, presumably located on the Ölrain, rose to one of the main settlements of the Celtic Brigantier .

Turn of times to the 2nd century

16-15 BC During a campaign from the south over the central Alps, the Romans also occupied the Rhaetian Alpine foothills. In doing so, they preferred geographically favorable and strategically important points. One of these was Bregenz due to its location at the exit of the Alpine Rhine Valley, on the east bank of Lake Constance and at a narrow point in the land connection to what is now the Allgäu. The adopted sons of Augustus , Tiberius and Drusus , advanced to the lacus Brigantinus (Lake Constance) and took possession of the local Celtic oppidum. To consolidate their rule, the Romans built a wood-earth fort on Ölrain and a harbor fort on the lake shore. A vicus was created around the former in a short time , which was expanded even more generously after the destruction in the turmoil of the three Emperor's year of 68/69. The camp on the Ölrain, on the other hand, was only used for a short time and abandoned again towards the middle of the first century; its crew was assigned to the Danube border . After the construction of the Upper German-Rhaetian Limes , the place was no longer on the border with the Barbaricum , but far in the hinterland. The military installations were either removed or used civilly like the port. Brigantium developed over the next hundred years into a flourishing provincial town with a forum, temples, market hall, thermal baths and later also the most important port on Lake Constance.

3rd century

Between 233 and 259/260 AD, the Alamanni and Juthungen invaded Raetia several times, but Brigantium should not have been directly affected. The area north of the city, between Pfänder and the lake shore, could be blocked off with little effort. That is why troops of Germans passing through were forced to bypass these barriers along the northern lake shore. It is assumed that the place was largely spared from the incursions of Germanic tribes at least until 270. Archeologically verifiable layers of destruction in the surrounding Roman settlements from the 3rd century, Bernhard Overbeck dates them to the years 270/271, 280/283 and 288, but again no direct effects of these devastations on Brigantium could be determined. Nevertheless, the Germanic invasions probably led to a sharp drop in imports of goods to Raetia and to a decrease in travel, as the use of the overland roads became more and more dangerous.

For a trading town like Brigantium, this caused enormous commercial damage, which is probably why its economic importance had already declined considerably by the beginning of the 3rd century. Another cause of the downturn can be assumed to be a shift in the focus of Rhaetian north-south traffic to the east - to the Brenner Pass road - by the end of the 2nd century at the latest , which significantly reduced the importance of the Milan – Chur – Bregenz route. Even the Via Claudia Augusta , the old north-south artery of Rhaetia, was temporarily deserted in the 3rd century and apparently was only poorly maintained. Perhaps this was also connected with the stationing of the Legio III Italica in Regensburg , as a significant part of the administration was relocated there. Further reasons for the decline of the settlements in the Lake Constance area could have been the political, military and economic effects of the separation of the Gallic Empire . In addition, there was a climate change that lasted into the 6th century. It brought about a marked cooling with increased occurrence of precipitation.

All these factors may more or less have contributed to Brigantium finally regressing in the 3rd century to an insignificant place with a steadily decreasing population. As a reaction to the Alemanni incursions of 270/271, the population began to migrate from Ölrain to the hill of the upper town as early as these years. In 291/292 the Romans finally gave up the areas north of Lake Constance and withdrew again behind the original borders on the Rhine and Danube. By 300 at the latest, the settlement on the Ölrain should have come down to a largely deserted suburb.

4th century

From the 4th century onwards, a slight economic upturn emerged again, which was particularly evident from the coin finds. Since Brigantium became a border town again through the abandonment of the Dekumatland , the economic recovery is probably due to the renewed stationing of soldiers and the increasing importance of the traffic routes in the Alpine Rhine Valley . A permanent settlement of the hill plateau with the port area stretching along the lake shore as well as the renewed presence of the military is not conceivable until the tetrarchic period at the earliest . The settlement on the upper town hill was now also fortified with a stone wall.

In 377, Emperor Gratian passed the city on an army campaign against the Goths and Alans who had invaded the east of the empire . In 383 the governor of Britain, Magnus Maximus , tried to usurp control over the west of the empire and had the rightful incumbent Gratian murdered by officers in Lyon . The Alemannic tribe of the Lentiens , based north of the Rhine and Danube, took advantage of the departure of the western Roman troops to invade the territory of the empire. The Romans responded with a series of counterattacks, some of which also focused on the Lake Constance area. By the 390s, most of the settlements and estates in this region were largely devastated or abandoned, and most of the survivors withdrew to fortified hilltop settlements. Under Valentinian I a new port fort, Brecantia , was built, which belonged to the fort chain of the Danube-Iller-Rhine-Limes and was supposed to secure the section of the imperial border on the Upper Rhine and Lake Constance. Nevertheless, the importance of Brigantium declined rapidly in the late 4th century. This circumstance was possibly connected with the coin valuation, a continued decline in population and the return to natural economy.

5th to 9th centuries

The dramatic political and social upheavals of the Great Migration ultimately led to the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Brigantium did not survive this unsafe and chaotic period of time without major damage. After the collapse of the Roman administration and border defense, the Alamanni finally took possession of the area around the city from 470 onwards. They settled u. a. the Ölrain new and should have quickly mixed with the novels still resident there.

It is believed that a Christian community has existed there since the 4th century, but that it was not the only local religious community. However, the Christians were only weakly represented in the population still adhering to the old belief in gods. Between the years 610 and 612, the Irish-Scottish missionaries Columban and Gallus tried to renew Christianity in the Lake Constance area. A passage in the Vita des Columban shows that a large part of the city was in ruins at that time and the population had withdrawn to the castrum of the upper town. Columban settled in Brigantium for a while, where he supposedly performed a miracle (so-called beer miracle) and destroyed the old idols in the temple. However, the two did not have any resounding success in their missionary work. Only the founding of monasteries in the 8th century, such as B. St. Gallen , on the island of Reichenau and Pfäfers were able to anchor Christian teaching in this region in the long term.

According to a document from 802, Pregancia castro was designated the seat of a Frankish count and a Carolingian palace was established. In 840, Walahfrid Strabo , a monk and scholar from the Reichenau monastery , described Bregenz again as "oppidum", that is, as a fortified place.

Castles

The fortifications in Brigantium served primarily to protect the port. Ancient sources also report the use of ships with the help of which Augustus' adoptive son Tiberius and his army crossed Lake Constance. Perhaps there was also a sea battle with the Vindelikers. The Roman armed forces apparently operated from an island, either the Werd bei Eschenz or the island Reichenau . In order to get to the islands, a well-fortified base on the lake shore was necessary. The port fort at Steinbühel may have been built for this purpose. The latter and the fort on the Ölrain could have coexisted for a while.

In total there were four castles in the urban area of Bregenz, some of which could also be archaeologically proven:

Fort on the Ölrain

The wood and earth fort was probably built between 5 and 10 AD and was designed for a crew of 500 men. It was first suspected in the upper town. Based on the finds of 2.5 m to 3 m wide pointed trenches in Kaspar-Schoch-Straße, it is believed that it was actually located between Josef-Huter-Straße, Cosmus Jenny Straße, Willimargasse and Kaspar-Schoch-Straße. It probably measured 196 × 140 m and covered an area of 2.74 hectares. The evidence of two pointed ditches at the Böckleareal was a particularly important finding. In connection with a pointed ditch section discovered by Adolf Hild in the early 20th century, it was possible to The location of the earliest military camp in Brigantium can be clearly identified. Furthermore, numerous related finds prove the presence of Roman soldiers in the excavation area.

The decumanus of the later civil settlement, which ran from east to west, was identical to the main camp road (via principalis) . The section of the Spitz trench discovered by Adolf Hild probably protected the south wall. The interior development consisted of simple timber half-timbered buildings. A 30 × 14 m barracks and a stable with wood paneling, 0.5 m deep ditch and wooden floor could be assigned to their function. In addition, 25 m east of the stable building there were traces of a 8.5 × 5.5 m large water basin with clay walls, which either served as a cistern or could have belonged to a thermal bath. It is still disputed whether these are actually still findings from the military camp. The dedicatory inscription from the years 14-23 AD for Drusus the Younger (the so-called "Drususstein", see above) was considered by Adolf Hild to be the building inscription of the fort. This thesis is now considered refuted. Such systems had to be renewed regularly, however, as the weather and moisture in the soil were very heavy on the wood. The camp was therefore rebuilt and renewed again during the reign of Emperor Tiberius (14–37 AD).

At the time of Claudius (41–54 AD) the camp was dismantled again. The old wood was not burned or used for other buildings, but was obviously used to repair the main street. In the course of time, the road had again become in need of renovation, so that a new substructure had to be created. As demonstrated elsewhere, it consisted of a boarded grate made of wooden beams over which a layer of gravel was laid as a road surface. Thanks to the favorable soil conditions, the woods were perfectly preserved. They were dendrochronologically examined by employees in cooperation with the Federal Monuments Office and the Vorarlberg Museum . The evaluation of these data showed that the tree trunks must have been felled in the winter of 4/5 AD.

Steinbühel harbor fort

An early harbor fort, perhaps dating from the time of Augustus, is suspected by Christine Ertel under the Roman villa at Steinbühel (see below). Presumably its center was under the northern portico of the large inner courtyard. So far, only one pointed ditch running from east to west has been archaeologically proven. Regarding the interior development, Christine Ertel believes that she recognized an officer's house in the remains of a 21 × 18 m square predecessor building of the villa. It was u. a. with partly basement rooms, which are grouped around a small inner courtyard. A portico ran along the front of the building on the south wing. It was probably in use until 80 AD.

Fort in the upper town

This late antique fort was built at the end of the 3rd century. The archaeological findings are very poor due to the dense overbuilding of the upper town hill. In three places a 1.50 m wide wall was observed during excavations, which was probably part of the ancient defense. The fortification wall, which is still partially visible today, dates from the 13th century and is said to have been built on the foundations of the Roman wall. Although there are Roman spolia in the rise, reliable evidence of the previous Roman walls as the basis for the high medieval wall has not yet been successful.

Leutbühel harbor fort

During construction work in the city center in 1968, a carefully executed wall made of ashlar stones came to light, which Elmar Vonbank initially interpreted as part of the ancient quay. During the construction of the pedestrian underpass under Leutbühel-Platz and a department store a little further west between 1972 and 1973, further remains of the wall came to light. The longer wall could be examined more closely. After the groundwater had run off, it could be seen that the cuboids were sitting on a well-preserved pile grid (pilots). After examining the photo documentation, however, it quickly became clear that the system originally had a different function.

In several places, the remains of a massive cast masonry had been preserved above the ashlar masonry. It was partially preserved to just below today's ground level. In a profile section in the area of the supposed harbor basin, a floor level was also clearly visible. Furthermore, a little further south a remnant of the wall had recently come to light. Its foundation consisted of spolia (column drums), some of which protruded far, connected with metal brackets , which, however, did not rest on a pile grid, but directly on the gravel ground. The remains were therefore interpreted as part of a fortification.

The fort stood directly on what was then the shoreline. It served to protect the port and as a base for a patrol boat flotilla. After evaluating the finds (building block analysis, dendrochronological examination of the foundation wood; felling date between 372 and 381), the archaeologists came to the conclusion that the fort must have been founded at the time of the reign of Valentinian I , but counts together with a few other Limes forts in Syria, Arabia and North Africa, but still of the so-called "Diocletian type" (284-305). It had a rectangular, slightly warped, northwest-facing floor plan and was very similar to the forts in Irgenhausen and Schaan . The fenced-in area had a size of approx. 0.35 hectares and offered space for an estimated crew of 120–160 men. The defensive wall was on average 3–4 m wide. During the excavations, due to the modern overbuilding, only the south-western half of the camp could be cut, which made its reconstruction considerably more difficult. The largest exposed section of the wall - part of the south-west walling - was 31 m long and 4 m wide. Presumably, the 50 × 70 m fortifications were reinforced at their corners by four cantilevered corner towers approx. 11 × 11 m in size. As in Irgenhausen, there could also have been two smaller, inward and outward protruding intermediate towers on the side walls. The camp could be entered through two almost equally large gates in the north-west and south-east of the wall. Most of the barracks and functional buildings inside are likely to have been built onto the fort wall with their rear walls. They could only be detected on the basis of a 21 m long and 2 m wide section of wall running from northeast to southwest and a remains of floor screed.

garrison

Nothing is known about the occupations of the 1st to 3rd centuries AD, only the garrison unit of late antiquity has been proven beyond doubt.

According to the Notitia Dignitatum - until around 401 - a Roman patrol boat flotilla ( numerus ) was stationed in Brigantium , which was commanded by a prefect (Praefectus numeri barbaricariorum, Confluentibus siue Brecantia) . As a vehicle she used the small and very agile naves lusoriae (crew 18–32 men), the late Roman standard combat ship for securing the border rivers. The number belonged to the Rhaetian provincial army ( exercitus raeticus ) under the command of a Dux Raetiae .

Where the troops were housed is still largely unclear. A department may have been stationed in the Upper Town. In any case, the Valentinian fort was too small to accommodate all the ship's crews. Since the ships patrolled the lake most of the time, it can be assumed that the entire unit was not in Brigantium at the same time , especially since according to the Notitia there was a second base of the flotilla in Confluentibus ( Constantia Castle ?). The occupation's task was probably primarily to monitor the imperial border and control the transport links on land and water.

Civil settlement

administration

Brigantium was the only town-like settlement in the area of today's Vorarlberg in Roman times. As a political meeting place, religious focal point and market for the people of the Lake Constance region, it certainly had a special position. Whether the settlement was raised to a municipality or even a Roman colony (Colonia) remains unclear due to a lack of written sources, but the former is likely. The elevation to the status of an autonomous city could have been granted under the emperors Claudius , Hadrian or Caracalla, who were generous in such matters . The only vague reference to this - a milestone found at Zirl in Tyrol, which indicates the distance "AB" - was previously incorrectly interpreted as a Brigantio (from Brigantium). This is now considered refuted by the discovery of similar milestones, all of which relate to Via Raetia .

Findings

The settlement area began in the eastern part of the plateau and extended over a length of approx. 650 m along the road from Vindonissa to Cambodunum . The extent of the populated area on the Ölrain is difficult to assess; Due to the structures known so far, however, it should not have been more than 20 hectares. The period between the 2nd and 3rd centuries AD has been researched best, but little has been known about its early and late period. After the fort at Ölrain was abandoned, the fortifications were torn down and the pointed trenches filled in again. The city itself emerged from the fort vicus founded in the early 1st century AD. After a major fire, most of the buildings were rebuilt in half-timbered and stone. Its greatest extent probably falls in the 1st century AD or early 2nd century AD. North of the main street towards the end of the 1st century AD, three stone buildings with a portico facing the street were built. To the north of the stone buildings (A and B), a “garden or courtyard area” from the Roman period with very rich cultural layers and built-in structures was found under a medieval and modern area filling that was several meters thick in places. The latter also includes a water basin made of masonry and plastered with gravel mortar. Brigantium did not have a city wall .

At the turn of the 2nd to the 3rd century, there was a noticeable decline in building activity and, above all, the abandonment of those facilities that ensured higher living comfort (e.g. heating systems). From this point on, the city was also subject to a continuous process of shrinking. The Ölrain was gradually abandoned and the residents withdrew to a - much easier to defend - hilltop settlement in today's Upper Town. Settlement activity on the Ölrain is likely to have been limited to the core area at the end of the 3rd century. After the middle of the 4th century it was largely deserted. The last remains of the Roman building were probably removed there between the 10th and 12th centuries for the extraction of building material for the construction of the castle of the Counts of Bregenz .

Judging by the finds, however, not only the inhabitants of the Ölrain fled to the upper town, but also the rural population from the surrounding area. It may have served as a refuge for some time in times of crisis, as the remains of an older palisade fortification came to light under the defensive wall from late antiquity. The accommodations that housed a department of the city garrison were possibly also located here. During this time, greater settlement activity was otherwise only noticeable on the western slope of the upper town hill and around the naval port on Leutbühel.

building

North of the main street, d. H. on the side facing the lake, there were mainly representative villas and public buildings. Some of the living rooms were fitted with floor mosaics, marble and stone floors and hypocaust heating.

To the south of the decumanus , on the side facing the Gebhartsberg, there were much more modest residential houses as well as farms, craftsmen's and traders' quarters. Strip houses were observed most frequently . Some of the houses were up to 55 m long. But there were also smaller houses that deviated from the usual building scheme. They stood on long rectangular plots, the narrow sides of which faced the main street. The street side of the parcels was completely built up, but it loosened up again at the back. The houses were mostly square in plan, the rooms of which were laid out around an inner courtyard. The shops (tabernae) or porticos , which were open at the front, were concentrated towards the street, while magazines and private living rooms were connected to the rear. At the southern end of the built-up area, three houses were found next to each other, one of which may be referred to as a rest or guest house (mansio) . In another there was a stone block with the officially fixed dimensions of the time and a sundial.

Adolf Hild determined a total of four construction phases for the ancient settlement:

- Phase I is characterized by simple wooden or half-timbered houses with clay plastering, which were covered with thatched or shingle roofs and mostly had a cellar. In the interior, wooden floors could also be found in isolated cases. These buildings existed until the reign of Nero and were probably destroyed during the unrest of the Four Emperor's year 68/69. It is also conceivable that the military vicus on the Ölrain was burned down as planned after the associated fort was closed and that it was planned and rebuilt according to the needs of a civilian settlement.

- Phase II can be recognized by half-timbered buildings with wall foundations. According to the coin finds, they were probably made in the Trajan period. Characteristic of this construction phase is the warehouse of a dealer, in which burned fragments of terra sigillata from the Vespasian-Domitian period (early 1st century AD) were discovered. Presumably the building was destroyed during this time period.

- The phase III buildings were also erected in half-timbered construction, but were equipped with tiled roofs and are likely to date from the 2nd century AD. The equipment also included ovens in workshop buildings from the Trajanic / Hadrianic period. This construction period ended in the middle of the 2nd century AD.

- Phase IV can be seen in the buildings of the late period with drained dry foundations (pebbles), rising stone masonry and tiled roofs. Some of them were equipped with screed floors and hypocaust heating. According to the findings, they may have been in use until the early or mid-3rd century.

Building material

Lime pebbles dominate the masonry of the houses. Although there would have been enough gravel in the immediate subsoil, most of the building material was probably obtained from the bed of the Bregenz Ach. Obviously, the oil deck terrace should not be unnecessarily destroyed by digging gravel pits. Sandstone from deposits on Gebhardsberg and Riederstein was seldom used, the very porous rock weathered too quickly. It was mainly used where larger stones were needed (e.g. as a column base). The quarries in which the building material for Brigantium was extracted are likely to have been on Gebhardsberg or the rock faces of Kustersberg or in the molasse break-up of Riedenburg / Funkenbühel / Sandplatte. In the southern part of the Böckleareal a wall stood out with its numerous yellowish-white-cream-colored stones. The rock was probably heated very strongly during the extraction of quicklime for the production of mortar. The lime kiln was loaded with unsorted rubble. The silica lime that was erroneously burnt with and vitrified by the burning process was not crushed, but also used for the construction of the wall.

Forum

At the intersection of the two main streets was the multi-phase, 96.50 × 54.60 m large forum, which served as a marketplace and administrative center. The square system was oriented to the NW. It was equipped with a large inner courtyard, which was surrounded by a surrounding columned hall that was open to the inner courtyard. The pillars were painted red and white. The south-western outer wall was supported by buttresses at regular intervals. In the course of a renovation, the portico of the main entrance was made a bit more representative. Presumably dedicatory inscriptions were placed here. A staircase led to the inner courtyard, in which three larger monuments, including possibly an equestrian statue of an emperor, were erected. In the rear, left part of the courtyard was a small temple. The administration building was located at the northwest rear of the forum and was equipped with heated rooms. Their floor plans were somewhat asymmetrical due to their proximity to the terrace slope.

City spa

The public thermal baths were located southwest of the forum, directly on the main road, on the area of today's Protestant cemetery. Apart from the floor plan, little is known of this complex. The dating of the building is also unclear. Its main building was 20 × 20 m in size and consisted of nine rooms, some of which could be heated. The building complex was entered through a small courtyard on the north side. The wall thickness was 1.20 m, presumably they were once covered with a barrel vault. The northwest side was secured by large support pillars. After analyzing the course of a sewer, the water basins must have been in the northern part of the building. The warm bath was on the SW side. It was heated from a boiler room ( praefurnium ) . A courtyard with a two-aisled hall structure on the southwest side that came to light during the excavations could also have been part of the thermal bath complex. However, a structural connection could not be established. There is also no direct access to the thermal baths. The 40.75 × 13.45 m hall was entered via a staircase. Its interior was separated along the longitudinal axis by a row of columns, which - like those at the forum - were painted red and white. The shafts of the pillars measured 0.75 m, the archaeologists estimated the height of the hall to be around 7 m. The floor of the building was made of marble slabs. Presumably, the bathing industry ceased in the early 3rd century at the latest. Antique graffiti was still found in the remains of the plastering .

Rest house at the Böckleareal

In 2009, as part of an emergency excavation, a multi-phase building was discovered at the Böckleareal, which probably once served as a rest station (mansio) . It was very similar to the Mansio Immurium that was excavated near Moosham (State of Salzburg). A total of four construction phases from the 1st to the 3rd century AD could be distinguished. The arrangement and equipment of the remains of the building, as well as the presence of columns and a portico, indicate a representative building. Its location near the road connecting Chur and Kempten also speaks in favor of a rest house.

Villa at Steinbühel

The remains of the wall were examined by Samuel Jenny for the first time in 1884 and were uncovered and preserved between 1980 and 1990 during the construction of the city tunnel . Karl von Schwerzenbach believed he recognized a port barracks in it, Adolf Hild assumed it was the camp hospital (valetudinarium) . However, it was most likely not a residential building, but could have been used as a warehouse for imported olive oil and other goods.

This extremely luxuriously furnished, mid-imperial (80 AD or early 2nd century AD), 2600 m² villa suburbana consisted of 24 rooms, which were grouped around a 10 × 20.80 m large peristyle courtyard. Presumably the main building was single-story and covered with a gable roof. This type of floor plan goes back to Greek models and was also found in other variants in Pompeii and Herculaneum. Remains of a toilet were found in room 8. The inner courtyard itself was also surrounded on all sides by pillar-supported wall halls (portico) , which were covered by a pent roof. On the lakeshore there was a garden, which was also surrounded by a portico , the columns 2.80 m high. The utility rooms were in the north wing of the building. On the city side of the villa there was also a portico made of 18 columns (diameter 58 cm, probably 5.60 m high) through which the building could be entered. Just to the northwest stood a thermal bath, which almost certainly also belonged to the building complex of the city villa. In it was a cold water basin in a niche, which was decorated with elaborately designed wall paintings (e.g. dolphins, jellyfish). Ceramic fragments, glasses, lamps, bronze and iron objects were recovered from a well. The numerous animal bones, but also oyster shells, suggest very wealthy residents. The villa may have stood on the remains of an early port fort (see above).

Road system

The road system was laid out in a regular and rectangular grid typical of Roman settlements, which went back to the 1st century AD. The early and mid-imperial settlement spread along the 9 m wide main road ( decumanus ) , a section of the long-distance transport route Kempten-Augsburg from the Swiss Alps and the parallel roads that branch off from it. The decumanus ran - accompanied by a burial ground - along the embankment to the lake shore. The street also crosses the center of the excavation site at the Böckleareal, which has been investigated since 2009. In the area of the forum a second, 3 m wide main street ( cardo ) crossed the decumanus . Both streets were sometimes accompanied by covered colonnades ( portico ). The column bases found in previous excavations as well as a similar column pedestal that was also used secondarily suggest an imperial road, presumably it connected u. a. the port with the trunk road to Cambodunum . Lime pebbles dominate the road fill, crystalline pebbles (mostly amphibolite , more rarely gneiss ) are rarely found. These types of rubble differ markedly from the occurrences on the Ölrainterrasse. The bulk material was also obtained from the gravel banks of the Bregenzer Ach and separated into grain classes by fine sieving.

Cult buildings

The spoils discovered at the port fort at Leutbühel, especially the very large column drums and two consecration altars, could have come from an imperial temple that stood directly at the port.

The Roman temple district at Sennbühel, which was possibly dedicated to the Capitoline triad Jupiter , Juno and Minerva , but also to other deities (dis deabusque) , was located on the northern edge of the settlement on Ölrain. The approximately 29.50 × 32.50 m large area was surrounded by a pilastrated wall, which was 1 m wide and in places even up to a height of 1 m. It was interrupted by a 12 m wide staircase, of which several steps were still preserved. Fragments of architecture made of white marble were found at the foot of the stairs. Directly next to the main street stood a kind of hall, a temple with portico and a three-part cella had been laid out in a central position on a podium, to which a staircase led. Elliptical remains of the wall next to the cult area were viewed by Elmar Vonbank as an amphitheater .

A somewhat smaller (Celto-Romanesque) temple was a little further out of town on the left side of the decumanus .

Between the two temples there was still a small cult chapel, which was donated by the Brigantium merchants and, according to an inscription , was dedicated to the Roman pantheon of gods .

religion

Pagan cults

In addition to the cults of the classical Roman state gods, the Isis and Mithras cults have also been practiced in Brigantium since the 3rd century .

Christianity

So far, no archaeological evidence of the existence of an early Christian community in Brigantium has emerged. In this respect one can only fall back on hagiographic sources such as the Gallusvites or one has to rely on conclusions by analogy. When the Alamanni destroyed the settlement on the Ölrain in 259/260, Christianity had not yet established itself in this region. The cult activities were limited to the domestic area. That is why it is difficult to prove there on the basis of buildings. The late antique settlement area could only be examined selectively due to the dense development. The Christian cult probably spread from Italy to Raetia and was initially only able to gain a foothold in the larger cities. The chances of deeper roots in the area around Lake Constance were therefore extremely poor. Before the 4th century there was almost certainly no hierarchically organized Christian community in what is now Vorarlberg. Also that a bishop resided in Brigantium before 400 is rather unlikely due to the exposed border location. Due to the ongoing incursions of the Alemanni, the church organization, which was still in the process of being established, was probably smashed again, causing many residents to revert to the old faith. The Gallusvites report that the Irish Scottish missionary Columban found a church in Brigantium, but this had long since been converted into a place of worship for various gods. In the brigantium of the early 7th century, the missionaries did not find any pagan Alemanni either, but formerly Christian novels that followed a mixed cult of Christian and pagan elements.

port

The existence of an early and mid-imperial port has not yet been proven archaeologically, but it is very likely. The extensive Roman port was uncovered between 1968 and 1972 with a width of at least 80 m and a much larger, but currently undetermined length, recognizable by the mighty ashlar walls and dense rows of piles. The harbor district - Maurach, Untere and Obere Kirchstraße - was built up due to the finds, obviously already in the early days of Roman rule. The late Roman naval port on Leutbühel offered an anchorage for around ten ships (naves lusoriae) . They could either tie up at two simple wooden piers angled to the northwest, which formed smaller pools with hook-shaped ends, or they were pulled onto the beach. In the northwest it was protected by a pier made of wooden piles and sandstone blocks at the height of today's Kaspar-Hagenstrasse and Bahnhofstrasse. Presumably the bank reinforcement was also constructed similarly. Their traces (wooden planks) were found at the intersection of Jahnstrasse / Kaspar-Hagen-Strasse and at the National Bank. The remains of a granary (horreum) were uncovered in Maurachgasse .

economy

The economic basis was long-distance trade with the Mediterranean region, which was probably mainly carried out via the well-developed roads of the Alpine Rhine Valley and the Bündner passes. The trade connections reached as far as Hispania and Asia Minor. The discovery of forge furnaces and small hearths suggests that the blacksmith's trade played a greater role in the economic life of the settlement. The trade in ceramics from northern Italy and southern Gaul was also of some importance.

Burial ground

The Brigantium burial ground has been one of the most important archaeological sites in the Pre-Alps since it was discovered between 1847 and 1950. This is also because from the surrounding Roman settlements such. B. Arbon, Konstanz or Pfyn only little material in this regard is available. Ancient chronicles are also largely ruled out as sources of information for these places. In total, up to 1075 graves could be discovered and scientifically analyzed on the Ölrain. They offered a good insight into the culture, customs and traditions of a Rhaetian provincial town from the 1st to the 5th century.

The ancient necropolis was created between the eastern end of the Ölrain plateau and the old town hill. Its length is 340 m, its width about 140 m. Their center with a dense occupation of individual graves was located south of Gallusstrasse, further ancient individual graves were uncovered on Reichstrasse, Schillerstrasse, Anton-Schneiderstrasse, Bergstrasse and east of Kennelbachstrasse. The latter could also have belonged to a separate burial place in a Villa Rustica . A thoroughfare ran right through the cemetery. According to the current state of research, 78% of the burial ground is likely to have been excavated, the northeastern remainder of the area fell victim to landslides caused by erosion - probably as early as Roman times.

A total of up to seven occupancy phases could be determined. The burials along the main street - between today's Ölrainstraße and Riedergasse - consisted of cremation and body graves from the 1st to the 5th century. The number of graves from the 3rd century, however, was not very large. However, it is not known whether another burial ground did not exist for this period, which was newly laid out at the beginning of the 3rd century and then possibly also used as a burial place until the early 4th century. The poverty of grave goods during the 3rd century was striking, compared to the cremation graves from the early 1st century, but also again among the body graves of the 4th and early 5th centuries. The body graves were oriented east-west, the skulls were in the west. The late antique burials were all body graves. In some cases, however, the dead were also buried in body graves and urn graves in parallel. In the 4th century body burials replaced urn burials.

The deceased were buried in lead sarcophagi, wooden coffins, stone box or brick-plate graves and brick underground burial chambers. Furthermore, the existence of three mausoleum structures is known (grave structures I-III). Many of the graves were also equipped with additional niches and bordered with stone walls made of river pebbles.

In 1937 the early medieval ( Merovingian period ) burial place of a warrior was found under a choir pillar in the Church of St. Gallus, who was buried with a sax (short sword or knife) and a spathe in the grave, as well as several other graves without gifts. However, there was no continuity with the Roman burial ground.

Course of the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes from Brigantium to Fort Vemania

Listed according to the list Claudia Theune: 2004, p. 419

| ON / name | Description / condition | |

|---|---|---|

| Watchtower / Burgus Hörbranz | In the Hörbranz district of Betzentobel (Erlach parcel above Allgäustraße on the Pfänderwald slope), excavated in April 1932 by Josef Fink - school director in Hörbranz - and archaeologists from the Vorarlberg State Museum. It stood directly on the road from Brigantium to Cambodunum , which led through the Leiblach Valley , and served to protect the imperial border and to monitor road traffic. The occupation force is unknown, it was probably provided by one of the neighboring forts.

The watchtower, which was probably entirely made of stone, was built in the 4th century and had a square floor plan of 11.8 × 12 m. The wall thickness was 1.55 m. The entrance to the tower was on the west. The interior was once divided by partition walls made of wood and half-timbering. The floor was made of rammed earth. In the north there was a larger hearth, to the right and left of the entrance there were two more hearths. The rubble contained the fragments of several Roman gravestones (probably dragged here from the oil grave field), a bronze coin of Theodosius and various animal bone remains . After the investigation, the wall foundations were filled in again. |

|

| Watchtower / Burgus Gwiggen | ||

| Watchtower / Burgus Hohenweiler | His remains were found in the Gmünd district, near the Gmündmühle inn. The tower had an approximately square floor plan and measured 10 × 12 m. | |

| Watchtower / Burgus Burgstall | ||

| Watchtower / Burgus Waldburg | ||

| Watchtower / Burgus colloquial | ||

| Watchtower / Burgus Opfenbach | Tower with a square floor plan of 10 × 12 m. | |

| Watchtower / Burgus Mellatz | Tower with a square floor plan of 10 × 12 m. | |

| Watchtower / Burgus Meckatz | Tower with a square floor plan, 11.8 × 12 m, its walls were still visible until the beginning of the 19th century. | |

| Watchtower / Burgus Heimenkirch | ||

| Watchtower / Burgus Dreiheiligen | Discovered during the construction of the railway, square floor plan, dimensions 11.8 × 12 m. | |

| Watchtower / Burgus Oberhäuser | ||

| Vemania Castle |

Hints

At the Leutbühel, bronze plaques set into the ground mark the course of the ancient harbor wall. Remnants of the civil settlement have been preserved at the grammar school in Blumenstrasse and at the senior citizens' residence in Riedergasse. In the area of the Protestant cemetery, the remains of the wall from the mid-imperial thermal baths were excavated, restored and made accessible to the public. The foundation walls of the villa at Steinbühel (motorway access road to the city junction) have been preserved and are freely accessible. The finds from the excavations can be viewed in the Vorarlberg State Museum . In the exhibition are u. a. A model of the civil town on the Ölrain, inscription stones, the so-called fish fresco, small finds from civil settlements and graves, a sarcophagus made of lead, various ceramics, traditional costume components and a replica of the foundations of the port fort on Leutbühel are presented.

Monument protection

The facilities are ground monuments within the meaning of the Monument Protection Act. Investigations and targeted collection of finds without the approval of the Federal Monuments Office are a criminal offense. Accidental finds of archaeological objects (ceramics, metal, bones, etc.) as well as all measures affecting the soil must be reported to the Federal Monuments Office (Department for Ground Monuments).

See also

List of forts in the Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes

literature

- Karl Heinz Burmeister (ed.): Brigantium in the mirror of Rome. Lectures on the 2000 year celebration of the state capital Bregenz . Dornbirn, Vorarlberger Verlagsanstalt 1987, ISBN 3-85430-080-8 , (= research on the history of Vorarlberg, 15)

- Christine Ertel, Verena Hasenbach, Sabine Deschler-Erb (eds. :) Imperial cult district and port fort in Brigantium. A building complex from the early and middle imperial period . UVK, Konstanz 2011, ISBN 978-3-86764-182-1 .

- Christine Ertel, Helmut Swozilek (ed.): The Roman harbor district of Brigantium, Bregenz . (= Writings of the Vorarlberger Landesmuseum, Series A, Landscape History and Archeology. Volume 6). Vorarlberg State Museum, Bregenz 1999

- Gerhard Grabher: The late Roman port fort of Brigantium (Bregenz). In: Norbert Hasler, Jörg Heiligmann, Markus Höneisen, Urs Leutzinger, Helmut Swozilek: In the protection of mighty walls. Late Roman forts in the Lake Constance area. Published by the Archaeological State Museum Baden-Württemberg, Frauenfeld 2005, ISBN 3-9522941-1-X , pp. 68–70.

- Gerhard Grabher: The treasure trove from Lauteracher Moor. In: Liselotte Zemmer-Plank (Hrsg.): Cult of prehistoric times in the Alps. Athesia Publishing House, Bozen 2002, ISBN 88-7014-932-3 . (Italian German)

- Gerhard Grabher: Bregenz / Brigantium. In: Arch. Austria. 5/1, 1994, pp. 59-66.

- Michaela Konrad : The Roman burial ground of Bregenz - Brigantium . (= Munich contributions to prehistory and early history. Volume 51). Beck, Munich 1997,

- Florian Schimmer: The Italian Terra Sigillata from Bregenz (Brigantium) . Vorarlberger Landesmuseum, Bregenz 2005, ISBN 3-901802-18-5 .

- Florian Schimmer: At the beginning of the early imperial brigantium (Bregenz): civil settlement or military camp? In: Zsolt Visy (ed.): Limes XIX. Proceedings of the XIXth International Congress of Roman Frontier Studies held in Pécs, Hungary, September 2003 . University of Pécs, Pécs 2005, ISBN 963-642-053-X , pp. 609-613.

- Elmar Vonbank , Helmut Swozilek (ed.): The Roman Brigantium. Vorarlberger Landesmuseum Bregenz July 20–30. September 1985 . (= Exhibition catalog of the Vorarlberger Landesmuseum. No. 124). Vorarlberg State Museum, Bregenz 1985.

- Helmut Swozilek: Brigantium / Bregenz. In: Franz Humer (Hrsg.): Legion eagle and druid staff, From legion camp to Danube metropolis, special exhibition on the occasion of the anniversary "2000 years Carnuntum". Text tape. Verlag Ferdinand Berger & Sons, Horn 2007, ISBN 978-3-85460-229-3 , pp. 116-117.

- Helmut Swozilek: Bregenz: Roman villa on the Steinbühel. Vorarlberg State Museum, Bregenz 1991.

- Julia Kopf: Bregenz / Brigantium in the 3rd century AD. An investigation into the development of settlements in Roman times using selected small dating finds. Thesis . Innsbruck 2007.

- Julia Kopf: Bregenz / Brigantium in the 3rd century AD In: Gerhard Grabherr, Barbara Kainrath (Ed.): Files from the 11th Austrian Archaeological Conference in Innsbruck pp. 23–25. March 2006. IKARUS 3, Innsbruck 2008, pp. 139–149.

- Julia Kopf: On the settlement development of Brigantium in the late middle imperial period. Museums Jahrbuchverein, Vorarlberger Landesmuseumsverein, Bregenz 2011 ( online; accessed May 30, 2013 ).

- Julia Kopf: Review and Outlook: Traces of the early Roman military in Brigantium. In: Yearbook of the Vorarlberger Landesmuseumsverein. 2011, 68-75.

- Julia Kopf, Karl Oberhofer: Archaeological evidence of the excavation in 2012 in the fort area of Brigantium (GN 1037/11, KG Rieden, LH Bregenz) . Montfort. Journal for History of Vorarlberg 65/2, 2013, pp. 17–29.

- Julia Kopf, Karl Oberhofer: Brigantium / Bregenz, fort area: News on the location and size of the military post. Yearbook of the Vorarlberger Landesmuseumsverein 2013, pp. 60–73.

- Julia Kopf, Karl Oberhofer: Old and new research results on the main street of the Roman settlement Brigantium / Bregenz. In: Gaisbauer / Mosser (arrangement): Streets and squares. An archaeological-historical foray. Monographs of Stadtarchäologie Wien 7 (Vienna 2013) pp. 65–87.

- Rudolf Egger : From the old brigantium. In: Yearbook of the Vorarlberg State Museum. 1929, pp. 39-44.

- Adolf Hild: Brigantium and its prehistory. In: Yearbook of the Vorarlberger Landesmuseumsverein. 95, 1952, pp. 28-44.

- Adolf Hild: Archaeological research in Bregenz. In: Annual books of the Austrian Archaeological Institute. 26, 1930, Beiblatt, pp. 137-140.

- Adolf Hild: Late Roman border castle to Hörbranz. In: Germania. No. 16, 1932, p. 292 f.

- Hans-Jörg Kellner : The great crisis in the 3rd century. In: Wolfgang Czysz, Karl-Heinz Dietz, Thomas Fischer, Hans-Jörg Kellner: The Romans in Bavaria. Stuttgart 1995, pp. 309-357.

- Klaus Kortüm : On the dating of the Roman military installations in the Upper German-Raetian Limes area. Chronological investigations based on the coin finds. In: Saalburg yearbook. 49, 1998, pp. 5-65.

- Bernhard Overbeck : History of the Alpine Rhine Valley in Roman times . Part I: topography, find template and historical evaluation. (= Munich Contribution. Pre- and Frühsch. 20). Munich 1982.

- Bernhard Overbeck: History of the Alpine Rhine Valley in Roman times . Part II: The coins found in the Roman period in the Alpine Rhine Valley and the surrounding area . (= Munich Contribution. Pre- and Frühsch. 21). Munich 1973.

- Karlhorst Stribrny: Romans on the right of the Rhine in AD 260. Mapping, structural analysis and synopsis of late Roman coin series between Koblenz and Regensburg. In: Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission. 70, 1989, pp. 351-505.

- Samuel Jenny: Structural remains of Brigantium. In: Yearbook of the Vorarlberger Landesmusverein. 1896, pp. 16-25.

- Samuel Jenny: The Roman burial place of Brigantium . Eastern part . State Printing Office Vienna, 1898.

- John Sholto Douglass: The Romans in Vorarlberg. Wagner, Innsbruck 1870.

- Jochen Garbsch : The late Roman Danube-Iller-Rhein-Limes . (= Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of Southwest Germany. No. 6). Society for Prehistory and Early History in Württemberg and Hohenzollern, Stuttgart 1970.

- Jochen Garbsch: Overview of the late antique DIRL. In: Jochen Garbsch, Peter Kos: The late Roman fort Vemania near Isny. In: Two treasure finds from the early 4th century. Verlag Beck, Munich 1988, ISBN 3-406-33303-6 .

- Claudia Theune : Teutons and Romans in the Alamannia. Structural changes due to the archaeological sources from the 3rd to the 7th century (= supplementary volumes to the Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Volume 45). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2004, ISBN 3-11-017866-4 , pp. 410-422.

- Maria Bader: Military and civil settlement remains from Roman times on the Böckleareal in Bregenz. A preliminary report. In: Yearbook of the Vorarlberger Landesmuseumsverein. 2011, pp. 8-67.

- Wilhelm Sydow: The upper town of Bregenz in late antiquity. Vorarlberger Verlagsanstalt, Dornbirn 1995, p. 17.

- Alois Niederstätter: Early Christianity in Vorarlberg. In: E. Zacherl (Ed.): The Romans in the Alps. Historians' conference in Salzburg, Convegno Storico di Salisburgo, 13. – 15. November 1986. Bozen 1989, ISBN 88-7014-511-5 , pp. 221-225.

Web links

- University of Innsbruck, Institute for Archeology, Classical and Roman Provincial Archeology : FWF Project: From Military Camp to Civil Settlement. The genesis of the western periphery of Brigantium , Innsbruck 2012, (accessed on May 21, 2013)

- Vorarlberg Museum: Brigantium. Bregenz in Roman times , on the official website of the Vorarlberg Museum, Bregenz , (accessed on May 21, 2013)

- Models, plans and reconstructions regarding Brigantium

- Plans, excavation finds of the Valentinian port fort

- Floor plan of the Villa am Steinbühel

- Stone relief of the horse goddess Epona on aeiou

- Newspaper report about the discovery of the Mansio: Romans took a rest in Bregenz. Archaeologists found a mansio, a service area - the find is classified as significant , DER STANDARD, print edition, July 8, 2009

- Statue fragment (hand with cornucopia) in the Vorarlberg Museum Bregenz

- Austrian City Atlas: History of the City of Bregenz

- Karl Oberhofer: When the Romans came to Bregenz. The oldest Roman military camp in today's Austria. Contribution to ORF Science

- Location of the castles on Vici.org

Remarks

- ↑ Mentioned on the inscription of the Tropaeum Alpium .

- ↑ Strabo 4, 6, 8.

- ↑ 278.3 ff

- ^ Vita Sancti Galli , I / 5

- ↑ Chapter 27

- ↑ Michaela Konrad: 1997, pp. 19-20.

- ↑ In Segmentum II / 5 written in capital letters and represented as a double tower, in the Tabula Peutingeriana the symbol for hostel (Mansio) .

- ↑ Helmut Swozilek: 2007, p. 116.

- ↑ online

- ^ Geographical Information System (GIS) of the city

- ↑ A fragment of a hand with a cornucopia, the corresponding statue could either have depicted the goddesses Fortuna , Isis Fortuna, Abundantia, Concordia, Tyche or an empress, Elmar Vonbank, Helmut Swozilek: The Roman Brigantium. Vorarlberger Landesmuseum Bregenz July 20 - September 30, 1985 . Vorarlberger Landesmuseum, Bregenz 1985, (= exhibition catalog of the Vorarlberger Landesmuseum, No. 124); therein Elisabeth Walde : Roman bronzes from Brigantium. P. 69.

- ↑ CIL 3, 5769 : [D] ruso Tib (eri) f (ilio) / Caesari = "For Drusus Caesar, son of Tiberius." Elmar Vonbank, Helmut Swozilek: The Roman Brigantium. Vorarlberger Landesmuseum Bregenz July 20 - September 30, 1985 . Vorarlberger Landesmuseum, Bregenz 1985, (= exhibition catalog of the Vorarlberger Landesmuseum, No. 124), in it Norbert Heger : Roman stone monuments from Brigantium. P. 13.

- ↑ Helmut Swozilek: 1985, pp. 49-50.

- ^ Gerhard Grabher: 2002, pp. 563-565.

- ^ Bernhard Overbeck: Part I, 1982, pp. 23-24.

- ↑ Florian Schimmer: 2003, pp. 611–612.

- ↑ Julia Kopf: 2011, p. 105.

- ↑ Julia Kopf: 2011.

- ↑ Helmut Swozilek: 1985, p. 55.

- ↑ Helmut Swozilek: 1985, p. 104, Bernhard Overbeck, 1982, p. 228.

- ^ Cassius Dio 54, 22.

- ↑ Christine Ertel, Verena Hasenbach, Sabine Deschler-Erb: 2011, pp. 185–187.

- ↑ Florian Schimmer: 2003, p. 613.

- ↑ Christine Ertel, Verena Hasenbach, Sabine Deschler-Erb: 2011, pp. 184–188.

- ↑ Christine Ertel, Verena Hasenbach, Sabine Deschler-Erb: 2011.

- ↑ ND occ. XXXV, 32.

- ↑ Christine Ertel: 1999, p. 32.

- ↑ CIL 3, 5988 and CIL 3, 5989 , Ekkehard Weber: On the question of the city rights of Brigantium. In: Elmar Vonbank, Helmut Swozilek: The Roman Brigantium. Vorarlberger Landesmuseum Bregenz July 20 - September 30, 1985 . (= Exhibition catalog of the Vorarlberger Landesmuseum. No. 124). Vorarlberger Landesmuseum, Bregenz 1985, pp. 84–85.

- ↑ Karlheinz Dietz , Martin Pietsch: Two new Roman milestones from Mittenwald , in: Mohr, Löwe, Raute 6 (1998), pp. 41–57. Online version .

- ↑ Julia Kopf: 2007, pp. 6–39 and 142.

- ↑ Julia Kopf: 2007, p. 34.

- ↑ Julia Kopf: 2007, p. 36.

- ↑ Christine Ertel, Manfred Kandler: 1985, pp. 140–141.

- ↑ Christine Ertel, Manfred Kandler: 1985, pp. 141–142.

- ↑ Quote from Virgil's Aeneid (12.58ff): [... decus imperiumque Latini .... te penes in te omnis do (mu) s inclinata re .... cum (bit) ... unum oro .. .desiste manum commitere ... Teucris] , translation by RA Schröder: "... you protection and umbrella of the Latinus Pillar of the empire on which this house, this sinking one is based .... Please ask yourself one thing: let yourself go, don't stand in Field the Teucrum. "

- ↑ Christine Ertel, Verena Hasenbach, Sabine Deschler-Erb: 2011, pp. 184–188.

- ↑ CIL 3, 13542 , sandstone slab with inscription in profile frame, 0.77 x 1.20 x 1.20 m: Dis deabusq (ue) / cives L [a] t (ini) negot (iatores) / Brig [a] ntiens (it) .

- ↑ Alois Niederstätter: 1989, pp. 221-225.

- ↑ Elmar Vonbank: The Roman harbor wall at Bregenz Leutbühl, in: Montfort, 1972, pp. 256-259.

- ↑ Helmut Swozilek: 2007, p. 117.

- ↑ Michaela Konrad: 1997, p. 15.

- ↑ Adolf Hild: 1932, p. 292 f. and Jochen Garbsch: 1988, p. 119.

- ↑ The Romans on Lake Constance and Allgäu. P. 13–16, here P. 14. In: Werner Dobras: Chronologie des Landkreis Lindau . Verlag W. Eppe, 1985, ISBN 3-89089-004-0 .

- ↑ The Romans on Lake Constance and Allgäu. P. 13–16, here P. 14. In: Werner Dobras: Chronologie des Landkreis Lindau . Verlag W. Eppe, 1985, ISBN 3-89089-004-0 .

- ↑ The Romans on Lake Constance and Allgäu. P. 13–16, here P. 14. In: Werner Dobras: Chronologie des Landkreis Lindau . Verlag W. Eppe, 1985, ISBN 3-89089-004-0 .

- ↑ The Romans on Lake Constance and Allgäu. P. 13–16, here P. 14. In: Werner Dobras: Chronologie des Landkreis Lindau . Verlag W. Eppe, 1985, ISBN 3-89089-004-0 .

- ↑ Jochen Garbsch: 1988, p. 119.

- ↑ Jochen Garbsch: 1988, p. 119.

- ↑ Monument Protection Act ( Memento of the original dated November 15, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. on the side of the Federal Monuments Office