passion

|

|

This article was due to acute substance or form defects on the quality assurance side of the portal Christianity entered.

Please help fix the shortcomings in this article and please join the discussion . |

Under Passion (of Greek πάσχειν paschein , German , suffering ' , to endure', 'experience' and from Latin pati , suffer ' , suffer'; passio , suffering ' ) are understood in Christianity primarily the Passion of Jesus Christ , that is, his suffering and death including the crucifixion by the Romans in Jerusalem . The accounts of this in the gospels are called the passion story .

Passion in the New Testament and in the early Church

Biblical outline

For many interpreters of the Bible, Jesus' passion begins "with his incarnation" ( Jn 1.14 EU ), because the birth in the stable ( Lk 2.14 EU ), but also the flight to Egypt ( Mt 2.13 EU ) are indeed Christmas motifs, but contain suffering in the world and with the world. The conflicts that the adult Jesus of Nazareth had to endure especially with the scribes of Jerusalem are reported in detail in the Gospels and indicate Jesus' lifelong suffering.

All four Gospels give the Passion a lot of space, but especially the Gospel of Mark , which is why this Gospel was called a "Passion story with a detailed introduction" as early as the 19th century.

In addition, Jesus' preaching and prophetic work were repeatedly misunderstood by his own people; Jesus also fell into a state of mourning before the actual Passion. Jesus weeps over the city of Jerusalem ( Lk 19.41–44 EU ). The fronts between supporters and opponents of Jesus intensify, the conflictual situations come to a head. In the end, Jesus is accused of blasphemy ( Mk 14.63f EU ):

" 63 Then the high priest tore his robe and cried," Why do we still need witnesses? 64 You have heard the blasphemy. What is your opinion? And they unanimously passed the verdict: He is guilty and must die. "

This is where the core of the Passion tradition begins in all biblical gospels. Largely abandoned by his followers, Jesus is handed over to the Roman authorities of Jerusalem by the high priests Annas and Kajaphas . The Roman procurator Pontius Pilate passed the death sentence after he presented Jesus to the people one last time, with the words: “ Ecce homo ” (“See what a man!”), Also: “There, look at him, man ! "Or:" See, (only) a person! ").

The New Testament Gospels detail the process and the crucifixion that followed . The biblical Passion tradition ends with all four evangelists with the violent death of Jesus. The removal of the body from the cross and the entombment are then described.

For Jesus 'disciples, the Passion, especially Jesus' impotent suffering and death, is a problem. How can Jesus end like this if he is really supposed to be the Messiah, the Christ, even the Son of God ? Why does he have to die so miserably? According to Mark, Jesus' disciples initially understood the arrest only as a failure and as a threat: “Everyone left him and fled.” ( Mk 14.50 EU ). After the crucifixion of Jesus, the Gospels also report the disciples' reactions to flight and fear.

The compilation of the biblical Passion events from all four Gospels is called the Passion Harmony , also the history of the suffering and death of Jesus Christ or in Latin Summa Passionis 'summary of the Passion' . It is the special case of a Gospel harmony that tries to understand the Passion as a compilation of the various Passion stories of Jesus from the four Gospels as a unified narrative thread.

Dating

Historians believe that the date of the crucifixion is between AD 30 and 36. In addition, physicists such as Isaac Newton and recently Colin Humphreys excluded the years 31, 32, 35, and 36 on the basis of astronomical calendar calculations for the festival of Passover, so that two plausible dates remain for the crucifixion: April 7, 30 and April 3, 33. Next As a limiting factor, Humphreys suggests that the Last Supper took place on Wednesday, April 1st in the year 33, further developing Annie Jaubert's double Passover thesis:

All the Gospels agree that Jesus held a last supper with his disciples before he died on a Friday just around the time of the feast of Passover (Passover was held annually on Nisan 15 , with the feast beginning at sunset the previous day), and that his body remained in the grave for the whole of the following day, i.e. on the Sabbath ( Mk 15.42 EU , Mk 16.1–2 EU ). However, while the three synoptic Gospels depict the Last Supper as the Passover Supper ( Mt 26.17 EU , Mk 14.1–2 EU , Lk 22.1–15 EU ), the Gospel of John does not explicitly designate the Last Supper as the Passover Supper and also dates the Beginning of the feast of Passover a few hours after the death of Jesus. John therefore implies that Good Friday (until sunset) was the preparation day for the Passover festival (i.e. the 14th Nisan), not the Passover festival itself (15th Nisan). Another peculiarity is that John refers to the Passover festival several times as the “Jewish” Passover festival. Astronomical calculations of the ancient Passover dates, beginning with Isaac Newton's method from 1733, confirm the chronological sequence according to Johannes. Historically, there have been several attempts to reconcile the three synoptic descriptions with John, some of which Francis Mershman compiled in 1912. The church tradition of Maundy Thursday assumes that the last supper took place on the evening before the crucifixion.

A more recent approach to resolve the (apparent) contradiction was put forward by Annie Jaubert in the course of the excavations of the Qumran settlement in the 1950s . She argued that there were two Passover feasts: On the one hand, the Passover date is said to have been calculated according to the official Jewish lunar calendar and so fell on a Friday in the year of Jesus' crucifixion; on the other hand, there was also a solar calendar in Palestine, which was used, for example, by the Essen sect of the Qumran community and according to which the Passover festival always took place on a Tuesday. According to Jaubert, Jesus would have celebrated Passover on Tuesday, but the Jewish authorities would have celebrated three days later, on Friday evening.

However, Humphreys stated in 2011 that Jaubert's thesis could not be correct, because the Qumran Passover festival was also celebrated after the official Jewish Passover festival. Nonetheless, he advocated Jaubert's approach of considering the possibility of celebrating the feast of Passover on different days. So Humphreys himself discovered another calendar, namely a lunar calendar based on the Egyptian method of calculation, which was then used by at least some Essenes in Qumran and the Zealots among the Jews and is still used today by the Samaritans . From this, Humphreys calculates that the Last Supper took place on Wednesday evening April 1, 33. Humphreys implies that Jesus and the other churches mentioned followed the Jewish-Egyptian lunar calendar as opposed to the official Jewish-Babylonian lunar calendar.

This Jewish-Egyptian calendar is presumably the original lunar calendar introduced by Exodus under Moses , which was then (and at least until the 2nd century AD) in use in the religious liturgy of Egypt. Later, during the 6th century BC. BC, in Babylonian exile , exiled Jews adopted the Babylonian calculation method and introduced it when they returned to Palestine. The different Passover dates come about because the Jewish-Egyptian calendar calculates the date of the invisible new moon and sets it as the beginning of the month, while the Jewish-Babylonian calendar only observes the waxing crescent moon around 30 hours later and notes it as the beginning of the month. In addition, the Egyptian day begins at sunrise and the Babylonian day at sunset. These two differences mean that the Samaritan Passover usually falls one day earlier than the Jewish Passover; in some years several days earlier. The old calendar (Samaritans) and the new calendar (Jews) are still both used in Israel.

According to Humphreys, a last supper on a Wednesday would make all four Gospels appear at the correct time, it would place Jesus in the original tradition of Moses and would also solve other problems: there would be more time than in the traditional reading (with a last supper on Thursday) for the various interrogations of Jesus and for the negotiation with Pilate before the crucifixion on Friday. In addition, there would be a Last Supper on a Wednesday, followed by a daylight trial before the Supreme Council of Jews on Thursday, followed by a brief confirmatory court session on Friday, and finally the crucifixion in accordance with Jewish judicial rules on death penalty charges. According to the oldest handed down court regulations from the 2nd century, a night-time trial of capital crimes would be illegal, as would a trial on the day before the Passover festival or even on the Passover festival itself.

Extra-Biblical Passion Stories

The authors of apocryphal Gospels and pseudepigraphic writings , such as the Gospel of Peter and the Gospel of Judas , know about the Passion of Jesus and interpret it in their own way. They add numerous details to the four canonical gospels:

- In the Gospel of Mark (and, following it, the Gospel of Matthew ), an anonymous centurion testifies to Jesus after his death as the Son of God . The Gospel of Nicodemus names this centurion Longinus . He is said to have stuck a spear, the Holy Lance , in the side of the crucified Jesus after his death . The figure of Longinus plays a role in the depictions of the Passion in Christian art .

- The Gospel of Peter reports that the Jews, elders, and priests recognized their guilt in the death of Jesus. They repent of the crucifixion. Peter and the disciples hide for fear of arrest, they fast and weep.

Passion in the Church

In all churches the passion of Christ is remembered in a special way during the Passion . This includes the practice of fasting and praying . Readings from the Bible, including the contemplative Lectio divina , approach the Passion of Christ. But also diverse forms of meditation and contemplation help to internalize the Passion event. The passion is modeled through rites and customs. The Church is concerned with the living visualization of the destiny of Jesus, i.e. with the fact that the former suffering of Jesus could just as well have taken place in the present.

What all churches have in common is that the Passion season ends on Holy Saturday and then ends with Easter . The name Passion has been used in the Western Church since the 9th century to denote the pre-Easter Lent .

Catholic Church

Lent in preparation for Easter is part of the Easter festival circle in the Roman Catholic Church . In the liturgy of the Catholic Church , the passion story (usually called “Passion”) is read alternately by three readers on Palm Sunday and Good Friday. On Palm Sunday the Passion from one of the synoptic gospels is recited: Reading year A: Matthew ( Mt 26.14 EU –27.66 EU ), reading year B: Mark ( Mk 14.1 EU –15.47 EU ), reading year C: Luke ( Lk 22.14 EU -23.56 EU ). On Good Friday the Passion according to John is always recited ( Joh 18.1 EU –19.42 EU ). The reading is introduced by Passio Domini nostri Jesu Christi secundum N. , 'The suffering of our Lord Jesus Christ according to N.'.

The Catholic Church cultivates the custom of visualizing the Passion of Jesus in devotion to the Cross , which can be prayed alone or in community both during Lent and in the church year, especially on Fridays. The stories of suffering of martyrs and saints are called the Passion .

Protestant church

Theology of the cross

In Protestant theology of the Passion of Jesus plays a particularly important role. Thus, Martin Luther formulated a theologia crucis 'theology of the cross' , also 'theology of the cross' , which continues to have an impact today. It is about a theological way of thinking in which the cross of Christ is at the center. The doctrine and life of the church must be measured against it. Luther tied directly to key statements of the Apostle Paul . Paul already put the Passion event at the center of his preaching ( e.g. Gal 6,14 EU or 1 Cor 2,2 EU , but also 1 Cor 1,18f EU ):

“The word of the cross is folly to those who are lost; but to us who are saved it is a power of God. We preach Christ crucified, an offense to the Jews and folly to the Greeks. "

In Lutheranism, "the word of the cross has become the center of the proclamation, [...] the message of the resurrection, on the other hand, has largely faded into the background". In this context, Horst Georg Pöhlmann states that there is a certain “over-accentuation of the cross”, but at the same time emphasizes that the cross and resurrection of Christ - and with them Passion and Easter - are indispensably linked. "Both healing acts [...] identify each other and are so inseparable."

Evangelical liturgy and spirituality

Both Martin Luther and Huldrych Zwingli emphasized the freedom of a Christian and thus questioned the compulsion to fast that prevailed in their time: “No Christian is obliged to do the works that God did not command. So he is allowed to eat any food at any time. ”For Luther, the fasting of the believers was not so much the focus of the pre-Easter period, but the passion of Jesus itself. For him, the preparation time for Easter was intensified again for the Passion time , the time:

"[...] in which people sing and preach about the suffering of our dear Lord Jesus Christ in the church."

In the Protestant area, the forty days before Easter are therefore called Passion Time , as a sign that the motif of the Passion of Jesus determines the entire preparation time for Easter, starting on Ash Wednesday . The biblical background for the celebration of the forty days is provided by all those texts in which a period of forty days - or forty years - has a special meaning ( Gen 7,4ff LUT , Ex 24,18 LUT , Jona 3,4 LUT , Mt 4,2 LUT and others). There are always times of transition, preparation, and purification that are reported here.

In the Protestant Church, special weekly devotions, passion services , take place in numerous parishes , in which the Passion texts are read and meditated in consecutive order. At the end of the 20th century, the custom of inspecting “ 7 weeks without ” emerged as an act of renunciation based on the fasting practice previously practiced . The liturgical color of the passion time is purple . In the liturgy of worship, the alleluia is omitted and the glory be to God on high .

Depictions of passion

Visual arts

sequence

In the fine arts, on the one hand, individual events and scenes from the Passion of Christ are presented; on the other hand, there are broader Passion Cycles which - more or less completely - chronologically trace the main scenes of the Passion tradition. The following presentation is largely based on the individual scenes as they are literarily recorded in the four Gospels of the New Testament, as they are visualized in the Holy Time through readings from the New Testament and thus also appear one after the other at Stations of the Cross :

- Entry into Jerusalem

- The washing of feet

- The last supper

- Christ on the Mount of Olives ( Gethsemane )

- The Judas kiss

- Capture of Jesus

- Christ before Kajaphas

- Denial of Peter

- Judas hangs himself

-

Christ before Pontius Pilate

- Exhibition of the Lord (Ecce homo , "Behold the man")

- Mocking Jesus

- Way of the Cross

-

Crucifixion of Christ

- The nailing of Jesus and the breaking of the legs (Crurifragium)

- Erecting the Cross ( Hypsosis )

- Distribution of clothes by the captors

-

Jesus on the Cross ( Seven Last Words , Crucifixion Group )

- Jesus' desperation ("My God, my God, why did you leave me?")

- Jesus' forgiveness ("Father, forgive them because they don't know what they are doing.")

- Jesus and the thieves (the repentant thief Dismas - "Today you will be with me in paradise.")

- Jesus' surrender on the cross ("Father, I put my spirit in your hands.")

- Jesus and his mother and the disciples (" Woman , behold your son !" And: "Behold your mother!")

- Soaking with vinegar ( posca , "I'm thirsty!")

- The passing of Jesus ("It is finished!")

- Opening the side

- "And the curtain was torn / And the bodies of the dead rose up"

-

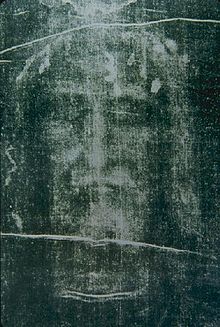

Man of Sorrows (representation of the suffering and wounds on the figure)

- Mater Dolorosa (Representations of the Mourning Mother)

- Descent from the Cross

- Rest of the dead of Jesus ( Good Friday )

Strictly speaking, the actual Passion of Jesus ends with his dead rest. This is how almost all church music passions handle it . However, in the performing arts, especially in passion cycles and art series, the last stages of Jesus' life are extended to include the Easter scenes of the resurrection:

Important examples (selection)

The Great Passion by Albrecht Dürer can be used as an example of a more extensive Passion cycle . It is a printed work that was printed in 1511. It is a book that tells the story of the Passion of Christ using Latin text and twelve woodcuts .

music

The Passion of Christ is reflected in numerous genres of music history and church music. These include:

Passions

In music , the passion story is mainly represented in passions. These form their own church music genre . In baroque music, in addition to the three passions by Heinrich Schütz (passions according to Matthew , Lukas and Johannes ), especially the St. Matthew Passion and the St. John Passion by Johann Sebastian Bach are important narratives of the Passion of Christ. Bach uses biblical texts, baroque poetry and song texts and combines them to a detailed description of the passion of Jesus. The feeling of the believers is added through musical means.

Passion Cantatas

Music history knows not only great passions, but also smaller cantatas related to the passion. An example of this is: Membra Jesu nostri , (Latin, translated: “The holiest limbs of our suffering Jesus”), a cycle of seven Passion cantatas by the Danish-German baroque composer Dieterich Buxtehude (BuxWV 75).

Stabat Mater

Settings of the Stabat mater also belong to the narrower subject area of the Passion. It is based on a Latin Passion poem in which the situation under the cross is reflected. The setting by the Italian composer Giovanni Battista Pergolesi , which conveys a special passion mood in the tonal language of baroque music, is often played .

The seven last words on the cross

The seven last words of Jesus on the cross were often set to music as a short form of a passion ; here the corresponding work by Joseph Haydn under the title The seven last words of our Savior on the Cross became known.

Modern forms

From the field of pop music , the musicals Jesus Christ Superstar and Godspell by Stephen Schwartz should be mentioned. There is also an album by Peter Gabriel called Passion , which is loosely linked to the Passion story because the music was created as the soundtrack for Martin Scorsese's film The Last Temptation of Christ (see below).

Movie

The character Jesus of Nazareth has been the protagonist of a film over 150 times , with the focus of the films on the Passion of Christ. In 1895, for the first time in film history, the Lumiere brothers shot a 221 meter long film about the life of Jesus in 13 scenes, from the arrival of the Magi to the Resurrection.

Feature films (selection)

The following films deal with the Passion of Christ in different ways:

- Passion by Allan Dwan , 1954

- Ben Hur by William Wyler , 1959

- The First Gospel - Matthew by Pier Paolo Pasolini , 1963

- The Greatest Story Ever by George Stevens , 1965

- Passion by Jean-Luc Godard , 1982

- The Last Temptation of Christ (The Last Temptation of Christ) by Martin Scorsese , 1988

- Jesus of Montreal by Denys Arcand , 1989

- The 120 days of Bottrop by Christoph Schlingensief , 1997

- The Passion of Christ (The Passion of the Christ) by Mel Gibson , 2004

Television productions

Franco Zeffirelli shot the four-part series Jesus of Nazareth for British television in 1977, the last two episodes of which deal with the Passion of Christ.

Further impact history

In addition to the memory of the Passion in the forms of liturgy, art and music, other forms of visualizing the Passion event, some of which are popular, emerged, some of which are, however, controversial between the denominations :

Passion tools and relics

With Passion tools (also: Arma Christi, Latin: Arma Christi - weapons of Christ ') are referred to objects that are related to the suffering and death of Jesus Christ. Since the late Middle Ages, the depiction of the instruments of suffering has also become common in Christian iconography . From the end of the 14th century, they are increasingly the subject of devotional literature and piety. Among other things:

- the cross with the titulus crucis , usually INRI

- the crown of thorns of Christ

- the scourge column

- the sponge soaked in vinegar or bile on a pipe

- the handkerchief of Veronica

These objects are closely related to the Passion Relics and Christ Relics , which were collected in different places.

The reformers developed the hermeneutic principle sola scriptura , i.e. the strict concentration on what has been handed down from the Bible . At the same time, this brought with it the rejection of all legends and extrabiblical sources. In the course of this Reformation reassessment, all forms of worshiping relics are assessed as “ unbiblical ”, even as idolatry , and are repressed in the Protestantism that followed, which in particular influences the piety of the Passion.

In Protestantism, the extra-biblical Passion traditions, secondary scenes and secondary figures of the Passion are viewed with the same skepticism. B .:

- Dismas and Gestas , the two thieves on the cross,

- Longinus the captain,

- Stephaton the sponge carrier or

- Veronica with the handkerchief,

while these traditions live on unbroken in Catholic piety up to the present day.

Passion churches

In the history of Christianity , houses of God were built that recall the Passion of Christ in a special way. Passion churches are sacred buildings with the patronage of the Passion of Christ. Another term is the Church of the Suffering of Christ . As a counterpart, among other things, resurrection churches apply . The crucifixion churches , which are found mainly in Italy, are an important subgroup of the Passion churches.

Passion play

As Passionsspielhaus spiritual drama about the Passion, the suffering and death of Jesus are called of Nazareth. Good Friday Plays and Passion Plays were common throughout Europe in the Middle Ages and early modern times. Well-known passion plays are u. a. the Waal Passion Play in Waal (the oldest in Bavarian Swabia ), the Oberammergau Passion Play and the Erler Passion Play in Erl .

Passion poems

The Middle Ages developed an independent passion spirituality . This also includes passion poems. An important example is Van den wapen Kristi , a Low German passion poem from the 15th century for the purpose of passion meditation. A later example is the poem and spiritual song by Paul Gerhardt O Haupt full of blood and wounds . It is based on the medieval Latin poem Salve caput cruentatum by Arnulf von Löwen from the 13th century.

Other forms of passion commemoration

Other forms of Passion Remembrance and Passion Spirituality include:

- Cross processions

- Writings that complement the Passion tradition, such as the “Secret Sufferings” of Christ.

literature

- Peter Egger : Crucifixus sub Pontio Pilato. Aschendorff, Münster 1997, ISBN 3-402-04780-2 .

- Marlis Gielen : The Passion Story in the Four Gospels. Literary design - theological focus . Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2008. ISBN 978-3-17-020434-8 .

- Christoph Nobody : Jesus and his way to the cross. A historical-reconstructive and theological model image. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-17-019702-2 .

- Karl Matthias Schmidt : The incorporated Jesus. Receptions of the Passion Story in Popular Film. In: Thomas Bohrmann, Werner Veith, Stephan Zöller (Eds.): Handbuch Theologie und Popular Film. Volume 2, Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2009, ISBN 978-3-506-76733-2 , pp. 295-309.

- Joseph Ratzinger- Benedict XVI : Jesus of Nazareth. Part Two: From Entry into Jerusalem to Resurrection. Herder Verlag, Freiburg / Basel / Vienna 2011, ISBN 978-3-451-32999-9 .

- Ulrich Wilckens : Theology of the New Testament. Volume 1/2: History of early Christian theology: Jesus' death and resurrection and the emergence of the Church from Jews and Gentiles. Neukirchener Verlag, Neukirchen-Vluyn 2003, ISBN 3-7887-1895-1 .

- Jean Zumstein , Andreas Dettwiler (Ed.): Theology of the Cross in the New Testament . Mohr Siebeck, Tübingen 2002, ISBN 3-16-147775-8 .

Web links

- Interpretation of the Passion of Jesus

- Current literature on the Passion of Christ, including the film by Mel Gibson

- Christian meaning of the passion of Christ

Individual evidence

- ↑ so inter alia Sabine Poeschel, Handbuch der Ikonographie , Darmstadt 2005, p. 163, ISBN 3-534-15617-X

- ↑ So Martin Kähler in: The so-called historical Jesus and the historical, biblical Christ. 1896, page 80

-

^ Paul William Barnett: Jesus & the Rise of Early Christianity: A History of New Testament Times. InterVarsity Press, Downers Grove (Illinois) 1999, ISBN 0-8308-1588-0 , pp. 19-21.

Rainer Riesner : Paul's early period: chronology, mission strategy, theology . Grand Rapids (Michigan); Eerdmans, Cambridge (England) 1998, ISBN 0-8028-4166-X , pp. 19-27. P. 27 provides an overview of the different assumptions of various theological schools.

Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum: The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament . B & H Academic, Nashville (Tennessee), 2009, ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 , pp. 77-79. - ↑ Colin J. Humphreys: The Mystery of the Last Supper. Pp. 62-63.

- ^ Humphreys: The Mystery of the Last Supper. P. 72; 189

- ↑ Francis Mershman (1912): The Last Supper . In: The Catholic Encyclopedia . Robert Appleton Company, New York, accessed May 25, 2016.

- ^ Jacob Neusner: Judaism and Christianity in the first century . Volume 3, Part 1. Garland, New York 1990, ISBN 0-8240-8174-9 , p. 333.

- Jump up ↑ Joseph Ratziger: Jesus of Nazareth: From the Entrance Into Jerusalem to the Resurrection . Catholic Truth Society and Ignatius Press, 2011, ISBN 978-1-58617-500-9 , pp. 106-115. Excerpt from the Catholic Education Resource Center website ( July 13, 2013 memento in the Internet Archive ).

- ^ Humphreys: The Mystery of the Last Supper . Pp. 164, 168.

- ↑ Nagesh Narayana: Last Supper was on Wednesday, not Thursday, challenges Cambridge professor Colin Humphreys . In: International Business Times . April 18, 2011, accessed May 25, 2016.

- ↑ K. Dienst, article Passionszeit , in: The religion in history and present, Vol. 5, Tübingen 1961, Sp. 142, ISBN 3-16-145098-1

- ^ Official report of the 4th general assembly of Luth. World Federation, Document 75 of the conference of the Lutheran World Federation in Helsinki 1965, p. 528 and also Horst Georg Pöhlmann: Abriss der Dogmatik. 3rd edition, Gütersloh 1980, ISBN 3-579-00051-9 , pp. 211, 212.

- ↑ Horst Georg Pöhlmann: Abriss der Dogmatik. 3rd edition, Gütersloh 1980, ISBN 3-579-00051-9 , p. 212.

- ↑ Horst Georg Pöhlmann: Abriss der Dogmatik. 3rd edition, Gütersloh 1980, ISBN 3-579-00051-9 , p. 211.

- ↑ So Huldrych Zwingli on January 29, 1523 at the 1st Zurich Disputation in the 67 closing speeches

- ↑ see in detail: Sabine Poeschel: Handbuch der Ikonographie. Darmstadt 2005, ISBN 3-534-15617-X , pp. 163-186

- ↑ Life of Jesus on the canvas . In the Sunday paper. January 3, 2009 ( online ).

- ↑ see in detail Petra Seegets: Passion Theology and Passion Piety in the Late Middle Ages. The Nuremberg Franciscan Stephan Fridolin (died 1498) between the monastery and the city. Tübingen 1998, p. X, 338 pages. SMHR 10, ISBN 978-3-16-146862-9 .