Turin Shroud

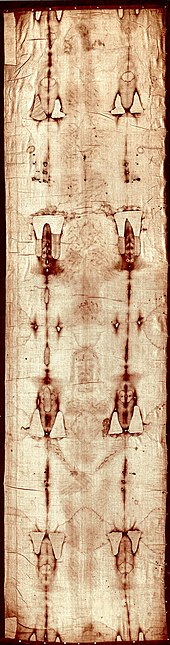

The Turin Shroud ( Italian : Sindone di Torino, Sacra Sindone ) is a 4.36 meter long and 1.10 meter wide linen cloth that shows a full-body portrait of the front and back of a person. The cloth is kept in the Shroud Chapel of Turin Cathedral, which was built at the end of the 17th century .

The origin of the cloth and its appearance are the subject of intense debate among theologians, historians and other researchers. Venerated by many believers as the shroud in which Jesus of Nazareth was buried after the crucifixion, it has inspired a number of depictions of Christ.

The first documented mention of the cloth took place in the 14th century. One of the responsible bishops spoke out against recognizing the cloth as a relic. Other artistically designed grave cloths are also known from the 14th century, as is the associated technique of linen painting with tempera paint , which produces images with unusual transparent properties. The radiocarbon dating of 1988, which was carried out independently of this , also points to an origin as a medieval artifact from this time. The cloth remained the property of various aristocratic families, most recently the House of Savoy , and was not given to the Catholic Church until the late 20th century.

The veneration of the shroud was intensified in particular in the late 19th century after the first photographic negatives of the grave shroud revealed a three-dimensional and lifelike image of great artistic value. The worldwide media coverage and the renewed interest in the cloth made it one of the most studied archaeological objects of all. In contrast to most other historical objects, the large number of high-quality investigations made it significantly more valuable. For advocates of the authenticity of the shroud, it is an acheiropoieton as a non-man-made image .

Religious interpretations

The cloth is not classified as a relic by the Catholic Church , but as an icon . The picture is more than an object of art, it can serve as an existential connection between the viewer and what is represented, and indirectly also between the viewer and God. Notwithstanding this, some believers venerate the cloth as a relic in the sense of a real shroud of Christ .

History of the Shroud

Generally accepted story

The oldest undisputed written sources mentioning the existence of the cloth go back to the middle of the 14th century. In 1353 the French knight Geoffroy de Charny received the order from King John II the Good to build a collegiate church in Lirey near Troyes , Aube department in Champagne. There the shroud was first presented to the public in 1357 - documented by a pilgrim's medallion. Since marauding gangs threatened the cloth in Lirey, it was brought to a chapel in Saint-Hippolyte by canons for security reasons in 1418 . It stayed there for 34 years until in 1453 it passed into the possession of the House of Savoy from the widow of the late Count Humbert of the noble House Faucogney family , Margaret de Charny. During this time, the owners of the time took it with them on their travels and exhibited it in various places. Once a year the cloth was shown to the faithful at a place called "le Clos Pascal".

The authenticity of the shroud was questioned very early on. The incumbent Bishop of Troyes, Pierre d'Arcis, reported in a letter of complaint to the antipope Clement VII in 1389 about a scandal that he had discovered in the church in Lirey. There they “... falsely and deceitfully, with consuming greed and not from the motive of devotion, but only out of the intention of profit for the local church, a cunningly painted cloth on which the twofold image of a man is depicted with clever dexterity, that is Front and back view, of which they falsely claim and pretend that this is the real shroud in which our Savior, Jesus Christ, was wrapped in the grave tomb. ” In addition to the, in his opinion, implausibly explainable lack of mention of a shroud with a body image in the Gospels, Pierre d'Arcis referred to his predecessor, Bishop Henri de Poitiers. During his tenure, 30 years earlier, the cloth was first exhibited. Accordingly, after learning of the matter, Henri de Poitiers undertook an investigation and "... discovered the deception and how the cloth was cunningly painted, the artist who painted it confirmed the truth, namely that it was the work of human skill, and not a miracle or a gift. ” The name of the forger was not mentioned. Pierre d'Arcis' judgment was supported by documents from Geoffroy de Charny's son Geoffroy II, in which the shroud was only mentioned as a “portrait” or “representation”. His daughter Margaret de Charny and her husband Humbert de Villersexel, who were in possession of the scarf, only commented on the scarf in this way. Due to the episcopal appeal, Antipope Clement VII stipulated in 1392 that the cloth was not a relic. An exhibition is allowed as long as it is not presented as the shroud of Christ. Pierre d'Arcis received an order from Clement VII under threat of excommunication to maintain silence about his views on the cloth.

With the transfer of ownership of the cloth from the descendants of Geoffroy de Charny to Duke Ludwig of Savoy in 1453, there was a change in the official assessment of the cloth. In 1464, Francesco della Rovere, who later became Pope Sixtus IV , spoke of the cloth as "colored with the blood of Jesus". His nephew, Pope Julius II , dedicated a special festival day (May 4th) to the cloth as the “Holy Shroud” in 1506, on which a mass and a ritual in honor of the cloth was to be held, although the cloth was not the only recognized holy shroud of that time. Pope Gregory XIII In 1582 he issued a perfect indulgence, which he granted to all who, after confession, penance and the Eucharist, pray devoutly to God in front of the exposed shroud.

After the cloth came into the possession of the House of Savoy , the respective rulers of the family carried it with them as a prestige object on their travels from castle to castle within their possessions. It was thus kept in many places and from time to time also shown publicly. In 1502 the cloth was set up in the castle chapel of Chambéry , the then residence of the House of Savoy, in a temporary permanent storage place in a niche behind the altar that still exists today. The cloth, which was kept folded up in a silver box, survived a fire disaster in the castle chapel of Chambéry in 1532. However, it had symmetrical burn marks and water stains on the edge. The burn holes were sewn up by nuns two years later. On September 14, 1578, Duke Emanuel Philibert of Savoy had the shroud transferred to Turin , the new royal seat of the House of Savoy, where it is kept in Turin Cathedral , the Duomo di San Giovanni, to this day. Only in 1939 was it moved via Rome to the Abbey of Montevergine in southern Italy, where it was hidden in the choir altar. Officially, this was done to protect it from a possible bombing of Turin. According to the historian and director of the Montevergine State Library, Andrea Davide Cardin, this relocation was also carried out to protect it from being accessed by the National Socialists. He relies on references in contemporary documents from Cardinal Maurilio Fossati , the archbishop of Turin at the time. On October 29, 1946, it was returned to Turin with great discretion. It remained in the possession of the House of Savoy beyond the end of their kingship in Italy in 1946, even if it has since been practically under the custody of the Archbishop of Turin . After the death of the former Italian King Umberto II of Savoy in 1983, it was bequeathed to the Pope and his successors, with the proviso that it would remain in Turin.

When the burial cloth chapel between Turin Cathedral and the castle burned on April 12, 1997, the cloth was saved intact by the fireman Mario Trematore, who smashed the protective armored glass at the last minute. Since 1998 it has been kept in a side chapel of the cathedral in a special container filled with argon in order to better protect it from environmental influences. During conservation work in 2002 by the textile restorer Mechthild Flury-Lemberg , the patches from 1534 were removed again, a new supporting cloth was sewn underneath and the wrinkles that had arisen from four hundred years of storage in a rolled state were smoothed out.

Shroud exhibitions

The shroud remains almost exclusively in its sealed shrine and is rarely exhibited publicly or non-publicly on irregular occasions. The last exhibitions of the shroud since the end of the 19th century were from April 24th to 27th, 1868 for the wedding of Crown Prince Umberto , and from May 25th to June 2nd, 1898 on the occasion of various anniversaries of the Savoy royal family, when it was also photographed for the first time all known historical documents on the shroud at the time were collected, from May 3 to 24, 1931 on the occasion of the wedding of Prince Umberto the year before , from September 24 to October 15, 1933 for the Holy Year (1900th year of Jesus' death), not public from November 22 to 24, 1973 for a RAI television documentary with one of Pope Paul VI. introduced direct broadcast on November 23, 1973, then public again only after 45 years from August 26 to October 8, 1978 on the four hundredth anniversary of the transfer from Chambéry to Turin, during which the cloth was also scientifically examined by the Sturp team April 1980 in a private exhibition for Pope John Paul II on the occasion of his pastoral visit in Turin, then from April 18 to June 14, 1998 for the centenary of the first photograph of the cloth with a renewed visit by Pope John Paul II on May 24, then in the great jubilee year 2000 from August 12th to October 22nd (2000th year of Jesus' birth) and finally without any special occasion from April 10th to Pentecost Sunday, May 23rd 2010 by order of Pope Benedict XVI. who came to Turin himself and worshiped the cloth on May 2nd, 2010. At the request of Benedict XVI to show the shroud in the Year of Faith on the most evocative date for this, Holy Saturday , it was exhibited again on March 30, 2013 in a one-and-a-half-hour literal service with a video message from his successor, Pope Francis , broadcast directly on television . The last public exhibition so far was from April 19 to June 24, 2015 on the occasion of the 200th birthday of Johannes Bosco , founder of the Salesian Order , with a visit from Pope Francis on June 21, 2015. In an extraordinary exhibition on August 10, 2018 in preparation for the World Bishops' Synod in October, the shroud was shown to 2,500 young believers. On Holy Saturday, April 11, 2020, Archbishop of Turin Cesare Nosiglia held a closed prayer service on the occasion of the COVID-19 pandemic in front of the Shroud, which was broadcast live on television and streamed at the request of thousands of believers . The next public exhibition is planned for the Holy Year 2025.

Hypotheses on a history of the cloth before the 14th century

An English writer, Ian Wilson , argued in 1978 that the Shroud of Turin came from a cloth in Constantinople . The basis of the hypothesis was a report by Robert de Clari in 1204 about a shroud that had been kept in the Marienkirche of the new Blachernen Palace and was exhibited every Friday in such a way that the complete imprint of the Lord was visible.

This picture is in turn identical to the Abgar picture , a cloth portrait with a facial imprint of Christ from Edessa in Mesopotamia, which was first mentioned in the 6th century. As proof of the identity between the Abgar image and the shroud, a code that was destroyed in 1943 and is now only available in copy is given, according to which a relative of the Byzantine emperor returned the cloth from in the year after the sack of Constantinople in 1204 in the fourth crusade Pope Innocent III demanded. The picture was then sent to Geoffroy de Charny via the Templar Order, who made the Turin shroud accessible to the public in his collegiate church in 1357.

According to Averil Cameron , however, due to the differences in the historically described dimensions and the nature of the Abgar image, these cannot be identified with the Turin Shroud. In addition, she comes to the conclusion that the Abgar image is an artifact whose origin lies in the resistance to iconoclasm . In addition, since 1988 there has been an incompatibility with radiocarbon dating , which suggests that the cloth has medieval origins.

According to the radiocarbon dating of the Turin shroud, the shroud researcher Noel Currer-Briggs advocated the thesis that the shroud from the Blachernen Palace, the authenticity of which is not clear, came into the hands of the Crusaders after the conquest of Constantinople in 1204, but was ultimately destroyed; probably in 1242 during the Mongol storm . The Turin shroud was a replica , possibly on the orders of the Grand Master of the Templar Order , produced as a replacement.

Two illustrations in the so-called Codex Pray - created between 1192 and 1195 - show the anointing of Jesus and the open grave. The first illustration shows the body of Jesus being anointed on a shroud and the second shows the empty shroud with a pattern, but without a body image on the shroud itself. According to Wilson and Bulst, the following points indicate a connection : “The position of the corpse; complete nudity (unique); the position of the arms and hands, especially the missing thumbs (which are added on most copies). The second picture is supposed to show the unusual fabric structure of the shroud, the older burn holes on the upper half of the cloth are in the same order. ”The fact that this picture appears in a Hungarian codex could be explained by the fact that the Hungarian queen at the time was a Byzantine princess was.

Further approaches to the history of the origin of the cloth are of very different quality. For example, there is the hypothesis that the cloth imprint comes from the 23rd Grand Master of the Knights Templar , Jakob von Molay , who was burned at the stake after being tortured . Even Leonardo da Vinci has been named as the author of the grave cloth.

Scientific investigations

History of Sindonology

Some call archaeometric investigations on the shroud as Sindonology ( ancient Greek ἡ σινδών - sindón , the shroud, also a clothing in the Gospel of Mark ).

The first photograph of the cloth in 1898 by Secondo Pia , who found that the portrait looked much more detailed in the negative than in the original, triggered an intensive study of the cloth. The first scientific investigations into the creation of the image and its authenticity were carried out from 1900 by the biologist Paul Vignon and the anatomy professor Yves Delage, who confirmed the authenticity at the time. Medical doctor Pierre Barbet conducted further research in the 1930s, mainly on the circumstances of death by crucifixion.

In 1969, the Archbishop of Turin set up an Italian commission that photographed the cloth, made recommendations for further tests, but did not carry out any tests itself. An Italian commission formed in 1973, consisting of serologists, forensic experts, textile and art experts, took samples and carried out several tests for the presence of blood. The final report La S. Sidon: Ricerche e studi della Commissione di Esperti , submitted in 1976, noted that all blood tests carried out were negative. Eugenia Rizzati determines the presence of tiny yellowish-orange to red grains on the fibers, but no further special tests were carried out in 1973 that could have identified them as color pigments, for example. Two members of the commission, the Egyptologist Silvio Curto and the art expert Noemi Gabrielli, came to the conclusion in this final report that the shroud was an object made in the Middle Ages. Both later distanced themselves from their findings.

In 1978 further research and sampling was carried out by the Shroud of Turin Research Project, Inc. (STURP) . In contrast to the previous Italian commissions, most of the members of STURP were American citizens.

One of the STURP members, Walter McCrone , resigned from the group because of a heated controversy over his research. In his investigations on the STURP samples using polarization microscopy and secondary electron microscopy, McCrone came to the conclusion that the body image is caused by ocher pigments, and the blood images are caused by both ocher and cinnabar color pigments. Both are red color pigments that were used by artists in the Middle Ages; According to McCrone, vermilion was recommended for the representation of blood. Blood tests and comparative tests carried out by McCrone on modern blood stains turned out negative and confirmed the results of the 1973 commission. He accuses the other members of STURP of the selective use of high-resolution analysis, which cannot refute the results from light microscopy.

STURP members J. Heller and A. Adler came to opposite results using microspectrometry and claimed that the blood images consisted of actually existing blood. J. Heller and A. Adler hold dehydrated yellowish fibers responsible for the body image, which, according to McCrone, is caused by the egg yolk used as a color binder . After McCrone's resignation, the STURP, which practically consisted only of supporters of authenticity, joined J. Heller and A. Adler in its final report. W. McCrone received support from other authenticity skeptics such as the petrologist Steven Schafersman , but also from numerous people who were otherwise rather remote from the authenticity discussion such as Linus Pauling . In 2000 McCrone received the American Chemical Society's National Award in Analytical Chemistry ; the application made reference to his work on the Turin Shroud. McCrones' conclusion received strong support from his results that the cloth was of medieval origin, but also from the radiocarbon dating carried out in 1988, which dated the cloth between 1260 and 1390 AD.

The other international congresses on the shroud and the associated publications are said to have a "depressing relationship with regard to factual information and religious interpretations" (H. Gove) and the limited and selective access for scientists to the shroud or samples taken from the shroud are criticized. The remaining members of STURP are accused that many members are more religiously than scientifically motivated and some are also members of the Catholic "Guild of the Holy Shroud" (English: Holy Shroud Guild ). One of the most vehement critics of STURP is S. Schafersman, who largely classifies their work as " pseudoscience ". W. McCrone lamented the strong pressure from the ranks of the Turin Sindonological Center to which he was exposed and to which he also attributes the distancing of S. Curto and N. Gabrielli from their statements in the expert report of 1976. Proponents of authenticity counter these allegations for their part with the accusation of bias towards the skeptics.

Possible ways of creating the image

Overview of attempted explanations

A distinction must be made between the actual depiction of a crucified and the depiction of blood stains. The chemical properties of the figures are controversial. Proponents of authenticity today mainly assume that the crucified image can be explained by dehydration and thus discoloration of the top fiber layer and that the substance of the blood images is real blood that has penetrated the cloth. This is clearly in contradiction to the results of Walter C. McCrone, who was the only microscopist in the research group to use light microscopy to detect and photograph ocher pigments in areas of the body image and blood stain images as well as cinnabar pigments in areas of blood stain images. Comparative tests with autologous blood gave a completely different result than what can be seen on the cloth.

Even if it is a painting, the creation and painting technique of the image on the cloth is still a mystery. Due to the quality of the picture and its special characteristics, it required a great deal of skill. There are many attempts to explain the creation of the picture:

- Contact print: body / template was wrapped in cloth. A discoloration occurred in places with direct contact, triggered for example by heat, chemical reactions, powder or color pigments applied to the body / template.

- Distance effect: body / template was wrapped in cloth. Discoloration not only occurs in areas of direct contact, but can also occur at a certain distance of a few centimeters between the cloth and the body or template. For example, electromagnetic waves , radioactivity , diffusion or electrostatic discharge have been suggested as discoloration mechanisms .

- Painting by an artist.

- Hybrid mechanisms: Mixture of several of the above mechanisms (example: bas-relief impression, in which the cloth does not come into direct contact with the actual template, but only with a bas-relief designed according to this template).

The possibilities of origin have been investigated by J. P. Jackson and others. The criteria by which they assessed the different methods were mainly the sharpness of the image and one of the three-dimensionality of the shroud image that they observed. This last requirement was made because by converting the local strength of the shroud image into a height relief, a very realistic-looking body relief could be created. According to these investigations, none of the above methods can satisfactorily describe the properties of the shroud image. Theories of distance effect can explain the three-dimensional information well, since the local strength of the images produced correlates with the expected distance of a sheet from the body at the respective point when this sheet covers the body. However, distance effect methods generally only produce blurred images. Contact printing methods and painting would be able to produce sharp images, but cannot explain the three-dimensional information. Hybrid mechanisms were also unable to meet all the required criteria, although bas-relief impressions came closest to the required criteria in comparison to the other methods.

Another important objection to an image (in all details) of a real human body through direct contact is the fact that the image is hardly distorted, although a strong distortion would be expected in any case due to the topology of a human head, similar to one two-dimensional map also only provides a distorted picture of the earth . Rather, the image represents a projection , which suggests the thesis of an artistic forgery using photographic techniques. A “flash of light” at the resurrection can only explain the undistorted and sharp projection with difficulty or not at all. Depending on whether one imagines the light flash from a point source within the body or from an extended diffuse point of view from the body surface, either the parts of the body further away from the point source should be distorted or, if the source is extended, the image should be rather blurred and blurred.

painting

The painting hypothesis was represented by W. McCrone, among others. Based on his research on the shroud, he came to the conclusion that the shroud was a painting from around 1355 for a new church which needed an attractive relic to attract pilgrims. According to McCrone, the technique with which the picture was painted is already described in a book Methods and Materials of Painting of the Great Schools and Masters written by C. L. Eastlake in 1847 (reissued in New York 1960). C. L. Eastlake describes in a chapter on medieval painting techniques Practice of Painting Generally During the XIVth Century a special technique of linen painting with tempera paint, which produces images with unusual transparent properties that, according to W. McCrone, resemble the shroud image. Other artistically designed grave cloths are also known from the 14th century.

Bas-relief

The bas-relief technique is represented by Jacques di Costanzo or Joe Nickell , for example .

Photography-like method

An attempt to explain it through a photography-like method is mainly represented today by the art historian Nicolas Allen. In a test series with a light-tight room (a kind of camera obscura ), in the aperture of which a simple modern lens made of optical quality quartz was attached, and linen cloths soaked in silver nitrate solution, he was able to produce pictures of statues on linen cloths with an exposure time of several days, which resemble the image on the Turin shroud and, as in this case, come about through bleaching of the outer fiber layers. The images generated in this way have the necessary sharpness to explain the shroud image and also contain the three-dimensional information required by J. P. Jackson and others (1984). The exposure time of several days is essential for the creation of this three-dimensionality, as a result of which the exposure conditions due to the sun change significantly during the exposure. Originally, J. P. Jackson had ruled out a photographic method due to the lack of three-dimensionality, although he used a modern camera. The difference is that the exposure conditions do not change during the short exposure time of a modern camera.

N. Allen justifies his hypothesis that the necessary materials and basic knowledge for a simple photographic method were known at the time of the medieval first reliable appearance of the cloth. The principle of the camera obscura had long been known at this time, and silver nitrate (often called Höllenstein in the past and used medicinally) was also available. The photosensitivity of some substances has been known for thousands of years, such as that of the dye purple . Albertus Magnus (1200–1280) mentions in his notes that silver nitrate applied to the skin changes color. Lenses cut from rock crystal were used, for example, as reading stones at that time, and the principle of the lens was also used for glasses since the 13th century at the latest. On the 11th / 12th Lenses dated to the 19th century, some of which have a quality similar to that of modern lenses, were found in Gotland ( Visby lenses ).

The main objection here is that a human body would decompose too quickly after days in the sun. Reference is also made to the results of A. Adler that there is no discoloration of the fibers underneath a blood image and therefore no image of the body, so that the image of the body was only created after that of the blood. However, it is not essential to N. Allen's method to use real human bodies - statues could also be used, as N. Allen did in his experiments - and A. Adler's results regarding the presence of blood are highly controversial.

Radiocarbon dating from 1988

Radiocarbon dating was used in 1988 to determine age. A 10 mm × 70 mm sample was taken from the left corner of the shroud, in the immediate vicinity of a 7.5 cm wide, sewn-on side strip. The divided sample was dated by three independent institutes with 95 percent confidence (confidence interval ) to the period between 1260 and 1390 AD, the mean value being given as the most likely value 1325 AD. The earliest recorded mention of the shroud comes from this time in 1357.

prehistory

An important prerequisite for dating from 1988 was the development and application of accelerator mass spectrometry as a novel method for dating using radiocarbon. Only this new measuring technique reduced the amount of sample so that a relatively small sample of the Turin shroud sufficed. An investigation in 1983 on three textile samples of known age, coordinated by the British Museum, had confirmed the feasibility of the planned investigation on the Turin Shroud.

At a conference in Turin in 1986, seven radiocarbon laboratories proposed a protocol for sampling and dating the Turin Shroud. It was planned to take samples from several places on the shroud and to date them by the seven laboratories. The Archbishop of Turin, representing the Holy See, selected three of the laboratories (University of Arizona, Oxford University, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Zurich). Other changes to the final protocol included sampling; instead of samples from several places, according to the new protocol, all samples were taken from the same place on the shroud.

Sampling, measurement and results

The sampling took place in the sacristy of Turin Cathedral on April 21, 1988. Present were Archbishop Ballestrero of Turin and his scientific advisor Gonella, a representative of the British Museum (Tite), representatives of the radiocarbon laboratories, two textile experts and G. Riggi, who took the sample. A strip approximately 10 × 70 mm in size was taken near a point where a sample had already been taken in 1973. Care was taken to ensure that there were no patches or charred areas at this point. This strip was divided into three samples, approximately 50 mg each. The Archbishop, his scientific adviser and the representative of the British Museum packed them individually in different containers along with control samples. Except for the packaging, the complete sampling was documented by video and photo recordings. Although the laboratories were not told which containers contained the shroud samples and which contained the control samples, they noted in their later publication that the shroud samples were clearly identifiable by the three-to-one herringbone weave pattern .

Since the shroud was exposed to several possible sources of contamination (dirt, smoke), special emphasis was placed on the pretreatment of the samples. All laboratories examined their samples microscopically to identify and remove contamination. The individual laboratories further divided their samples into several sub-samples and treated them with different chemical and mechanical cleaning methods.

The cleaned samples were burned, the carbon dioxide produced was converted into graphite pellets and measured using accelerator mass spectrometry. The British Museum Research Laboratory received the results for statistical analysis. The results were published in a specialist article in the journal Nature . The authors of the Nature article note that the spread of the measured values between the three radiocarbon laboratories is somewhat larger than would be expected if only a purely statistical spread were taken into account as an experimental cause of error. However, a detailed examination of the statistics of the radiocarbon results of the Turin Shroud by J. A. Christen led to the result that the determined radiocarbon age is correct from a statistical point of view. The measured values of the partial samples from the respective laboratories treated with different cleaning procedures showed no significant deviation of the measurement results from the other partial samples from the same laboratory, generally a strong argument against a significant falsification of a radiocarbon age through contamination.

| sample | Oxford | Zurich | Arizona |

|---|---|---|---|

| Turin Shroud | 1200 AD | 1274 AD | 1304 AD |

| Control sample (Threads, A.D. 1290–1310) | 1195 AD | 1265 AD | 1228 AD |

| Control sample (sheet, 11th / 12th century AD) | 1010 AD | 1009 AD | 1023 AD |

| Control sample (sheet, 1st century BC – 1st century AD) | 30 BC Chr. | 10 AD | 45 BC Chr. |

| Calculated time of origin after radiocarbon dating . Each laboratory also received three control samples of known ages. | |||

meaning

The radiocarbon dating of the shroud was very important in several ways. On the one hand, it contributed to making the general public aware of the possibilities of the new type of radiocarbon dating using accelerator mass spectrometry. On the other hand, it is widely accepted that the publication of the results in the journal Nature essentially concluded research on the Turin Shroud.

As before, supporters of the authenticity of the Turin Shroud object to the validity of the dating. Mostly, reference is made to a possible undetected contamination or non-representativity of the sampling point. Due to the large difference between the measured age and an age, as would be necessary for an authenticity of the shroud, scenarios are that a shroud from the 1st century has an apparent radiocarbon age in the 13th / 14th centuries. Century, extremely unlikely. A soiling of the shroud from the 16th century would have to make up about 70% of the shroud to shift a dating from the 1st century to the measured radiocarbon dating. Among others, Harry Gove , one of the main initiators of the shroud dating and an important exponent of the method, defended the validity of the dating and came to the conclusion that the shroud was not a relic, but was made by an artist as an icon.

Hypotheses that claim a falsification of the radiocarbon age

Different dating due to lignin-vanillin decay

R. Rogers, who was already a member of the STURP team in 1978, believed that he could show by means of different vanillin concentrations in different areas of the cloth that the radiocarbon sample was not representative of the shroud. Rogers concludes from this that in the Middle Ages a patch was artfully woven into the original cloth by " invisible reweaving ", which was not recognized as such when the samples were taken, and therefore the age of a plugged area was accidentally measured. For the age of the cloth, he gave a range of 1300 to 3000 years based on the vanillin concentration. This hypothesis is based on similar hypotheses by M. S. Benford, who based on analyzes of STURP data from 1978 put forward the thesis that the sample location was not representative.

However, the new dating has some serious weaknesses (see here): The age dated with this method depends heavily on the ambient temperature (hence the very large range from 1300 to 3000 years), in particular short times with high temperatures can make the measured age very strong increase. On the other hand, this is the only known attempt at dating using vanillin so far; a method validation and calibration of the method with other samples of known age as for the radiocarbon method was not carried out.

The “ invisible reweaving ”, which both Rogers and Benford's hypotheses presuppose, is also regarded as extremely implausible, since such a restoration without leaving visible traces is not possible even with today's means. Aside from the difficulty of creating an invisible seam, a piece of fabric that was visually and haptically indistinguishable from the original should have been available for incorporation. According to the textile expert Mechthild Flury-Lemberg, who was responsible for the restoration of the shroud in 2002, the expression " invisible reweaving " was created as a promise for the customers of today's restoration companies; However, experts would certainly recognize a place restored with this technique as being repaired with the naked eye. According to her, the weaving structure of the shroud is coherent and untouched, including at the corners where the samples were taken. The question also arises why this sophisticated technique of “ invisible reweaving ”, when it was already available, was only used to repair unimportant and not at all heavily damaged areas on the edge of the cloth and not also for the serious burn holes were only poorly sewn together with patches.

According to an editorial published in Thermochimica Acta in 2015 regarding R. Rogers' article, a closer analysis of the mass spectra obtained from Rogers reveals contamination in the samples used. When these are taken into account, the differences in the results for the vanillin concentrations in the various areas of the cloth disappear. The authors come to the conclusion that the “ pseudoscientific theory”, according to which the sample used for radiocarbon analysis comes from a patch woven in in the Middle Ages by “ invisible reweaving ”, is not supported by Roger's data.

Bacteria and fungus contamination

Still others assume an influence of bacteria and fungi , which - according to L. A. Garza-Valdes - would have prevented the cloth from decaying through a protective layer and influenced the distribution of the isotopes . The contamination required to produce such a large error of 1300 years through contamination according to Garza-Valdes is even in the best case if the contamination by microorganisms had only emerged in the 20th century and consisted only of phototrophic bacteria (i.e. bacteria, that would cover their carbon needs through photosynthesis from the carbon dioxide in the air), at 66 percent and is relatively unlikely. According to L. A. Garza-Valdes, the bacteria and fungi are also responsible for the creation of the image. Accordingly, these must have been present as early as the 14th century, and the required contamination would accordingly have to be much higher than 66 percent. In addition, such contamination can only arise from phototrophic bacteria, which absorb carbon dioxide from the air and thus falsify the radiocarbon age of the cloth. However, this requires light, and this type of contamination can be excluded for the period in which the cloth was stored in a container. It is more likely that the microorganisms are chemotrophic and feed on the shroud themselves and thus did not adulterate the radiocarbon age. In addition, recent studies have refuted the existence of such a biological layer.

Fire of 1532 - isotope exchange by heating

Some early dating supporters claim that the fire of 1532 distorted the dating results. Such claims, specifically that isotope exchange caused by the fire distorted the radiocarbon age, have been made in publications by Dmitri Kuznetsov and others. These claims were immediately rejected as incorrect by representatives of the radiocarbon laboratories and as not reproducible in tests carried out by the radiocarbon laboratories. In addition, the work of Dmitri Kuznetsov and others has proven to be scientifically dubious after review by Gian Marco Rinaldi.

conspiracy theories

Some conspiracy theories suggest that there was a deliberate swap of the radiocarbon samples prior to dating by those involved in the sampling. Mostly, reference is made here to the packaging and distribution of the samples by M. Tite from the British Museum and Cardinal Ballestrero, which was not documented by video or photo recordings. This thesis was represented, for example, in a book by the theologian Werner Bulst in 1990, a proponent of authenticity who was involved in research on the shroud for several decades. This conspiracy theory was also disseminated through a 1991 issue of the journal Catholic Counter-Reformation in the XXth Century , distributed free of charge , by an ultra-conservative Catholic organization, mainly located in France, which opposed the Vatican on a number of points. Furthermore, this thesis was taken up in 1992 in various books by Holger Kersten and Elmar R. Gruber and the theologian Karl Herbst, who represented their thesis that Jesus survived the crucifixion.

This conspiracy thesis is contradicted not only by the institutes actively involved in the dating, but also by the prominent proponent of authenticity, Ian Wilson. Wilson refers to his personal acquaintance with the people involved, such as Tite, asserts their integrity and stresses that he strictly contradicts such allegations. H. Gove suspected that the change of the protocol by the church, in particular the reduction of the sampling to a single place instead of the three originally intended sampling points, was made with the intention of giving the supporters of authenticity a point of attack in the event of a negative radiocarbon result in terms of authenticity to deliver against the dating.

Neutron hypothesis

It was also hypothesized that the resurrection produced a large number of neutrons , which increased the C-14 content in the cloth. However, this thesis is rejected by scholars because of the supernatural factor of the resurrection. In addition to a miracle, an extremely large coincidence would also be necessary in order to produce exactly the right amount of C-14, the measurement of which has the age of the confirmed first mention of the shroud as the result.

Further investigations and interpretations

The following properties of the shroud are considered unique:

- According to the brightness parameters, the image is a negative . This is expressed in the fact that the shroud image appears more realistic in the photographic negative than when viewed in the original. Nevertheless, it turns out that the image - if the local brightness parameters of the negative are transferred to a height relief - has a three-dimensionality that differs from a typical photographic negative of a modern camera with a short exposure time. On the other hand, modified photographic techniques with very long exposure times have been proposed which can produce such three-dimensionality. Other explanations have also been suggested; According to the Italian computer science professor Nello Balossino, experiment-based contact images, i.e. images that are created by placing a cloth on a body or face, contain three-dimensional information. According to Jacques di Costanzo, images with the three-dimensionality typical of the shroud can also be produced using contact prints from a bas-relief.

- Comparison with the picture of a real mask:

- The image is largely distortion-free in the manner of a photographic projection onto a flat surface. Nevertheless, it shows the front and back of the person depicted in full and identical size. This is important for the explanation of the creation of the image, as it is often argued that when a normal three-dimensional statue or a real person is cast, the result is distortion, which in the image on the cloth is only in a few details, but practically even in the face are not present.

- The illustration shows a man crucified in the manner of Jesus with traces of flagellation, crowning of thorns, nailing and opening of the chest. It is noticeable, however, that the details, deviating from Christian iconography , agree with the results of modern archaeological research: The traces of the crown of thorns do not result in a wreath, but a hood (in the Orient the royal hood was common and a wreath-shaped royal crown was unusual); the hands do not appear on the surface, but pierced at the root; the legs should have been bent to the side on the cross, not stretched out.

Type of crucifixion

It is often argued that the accurate details of a crucifixion seen on the Shroud were unknown to an artist of the Middle Ages. For example, it was not the palms of the hands that were broken through, as can be seen in almost all of the illustrations, but the wrists. This finding goes back to the French physician Pierre Barbet, who carried out corresponding experiments with corpses and calculations in the 1930s. The pathologist FT Zugibe published a paper in 1995 in which he pointed out some errors in P. Barbet's work and came to the conclusion that the nails were probably driven through the upper half of the palm and not through the destot space in the wrist as claimed by Barbet. However, according to Zugibe, the thumb side of the wrist cannot be completely excluded. Only since the crucified Christ was found at Giv'at ha-Mivtar in 1968 has a material testimony been available for the technique of the ancient crucifixion. The crucifixion penalty was not used in north-western Europe in the Middle Ages, in the east there were crucifixions and corporal punishments, as Jesus experienced, but well into the Middle Ages. According to the shroud researcher Noel Currer-Briggs, experience with these punishments, which were still being carried out at that time, together with the description of the sufferings of Jesus in the Gospels, should have enabled an artist in the Middle Ages to make the shroud image in great detail without actually crucifying a sacrifice for it. Self-crucifixions and self-harm for reasons of piety ( stigmatization ) are also more frequently attested in the Middle Ages, especially since the beginning of the 13th century in Western Europe.

Picture on the back

In April 2004, researchers from the University of Padua discovered a very faint and much less detailed image on the back of the cloth, consisting only of the slightly blurred face and hands. No other details are visible. Like the picture on the front, it is also the result of coloring only the outermost fibers of the fabric, and its representation is accurately compared with the front. This discovery came about during the evaluation of photographs that were taken in 2002 when, during the restoration of the Turin shroud, not only the 30 patches of fabric that covered the burn holes, but also the so-called Holland linen cloth sewn onto the back was removed after almost 500 years has been.

Ancient characters?

In 1997 the scientists André Marion and Anne-Laure Courage wanted to make inscriptions next to the face visible on the computer, among other things by means of digital amplification of color variations on the surface of the shroud. They are Greek and Latin letters about an inch tall. "ΨΣ ΚΙΑ" is written on the right half of the head. This inscription is interpreted as "ΟΨ ΣΚΙΑ" (ops = head; skia = shadow). On the left side the inscriptions “INSCE” (interpreted as “inscendat” = he may go up) or “IN NECE” (“in necem ibis” = you will go to death) and “ΝΝΑΖΑΡΕΝΝΟΣ” (misspelled “the Nazarenes ”In Greek), below“ HΣOY ”(genitive of“ Jesus ”, the first letter is missing). André Marion himself did not carry out any palaeographic investigations, but mentions in his article cited above in the concluding summary, briefly and quite generally and carefully formulated, that some palaeographers would rather place the signs before the Middle Ages. However, he does not give the names of the palaeographers or any other indication of how they reached their conclusions, which means that the claim can ultimately be classified as unfounded.

In November 2009, the Vatican historian Barbara Frale claimed to have discovered and deciphered an almost invisible text on the shroud that mentions Jesus of Nazareth and Tiberius by name.

Coins on eyes?

According to some Sindonologists, coins were placed on the eyes of the body of the shroud, a widespread burial custom in Hellenistic times. With reference to archaeologist Rachel Hachlili's excavation finds , these Sindonologists believe that this is also proven for Palestine, although Hachlili himself vehemently contradicts this interpretation of her findings. The idea arose in 1976 when researchers J. Jackson and E. Jumper, both researchers with the US Air Force at the time, tried to edit images . Also involved were K.Stephenson from IBM and R.Mottern from Sandia National Laboratories . They experimented with three-dimensional computer graphics and used photographs of the shroud as a test object. At the first 'US Conference of Research on the Shroud' in 1977, they reported on the three-dimensional properties and possibly "button-like" objects on the eyes. In an article published several years later by Jackson and Jumper together with W. Ercoline in the journal Applied Optics , where the results are published and evaluated for the first time, the three-dimensional structure of the image is discussed, but button-like objects in the eyes are not mentioned .

Motivated by these results, the American Jesuit Francis Filas presented enlarged images of the cloth to the coin specialist Michael Marx in 1979, based on a print of the original photographic plates made by Giuseppe Enrie in 1931. According to his interpretation, it could be the imprint of a Lituus coin, which shows a characteristic staff symbol and was minted by Pontius Pilate in Judea during Jesus' lifetime . The issues in question are said to be bronze coins minted in the years 29 and 30, which are represented in standard numismatic works . Filas believed that he could also identify fragments of the coin inscription, which consists of the words TIBERIOY KAICAPOC ("[coin] of the Emperor Tiberius"). According to Fillas, in 1981 his observations were backed up by further research by Interpretation Systems Inc. from Overland Park , Kansas , and traces of a coin are said to have been discovered in the right eye.

The American psychiatrist Alan Whanger compared the coin images, which cannot be seen in the photographs of the shroud with the naked eye, in 1985 using a technique he developed himself by polarizing images of the coins that were supposedly recognizable on the shroud by superimposing the photo Brought light to agreement. He thought he recognized four letters on the negative photo of the cloth in the right eye area: U C A I. Although this sequence of letters does not appear on the Lituus coins, in his opinion it is a fragment of the coin inscription from the year 29; for this purpose he assumes a hypothetical misprint.

Whanger's observations are not confirmed by serious research. Against his attempts, the objection is that no counter-tests were made with other templates in order to rule out that the method he developed leads to a positive result with other or even any comparison template. A. Whanger's technique is therefore cited as an example of bad science.

The Israeli archaeologist LY Rahmani denies that it was customary at this time to place coins in the eyes of the dead during Jewish funeral rites, such as those used at Jesus' burial according to the Bible. He also considers it extremely implausible that his disciples and relatives, who were all devout Jews, were supposed to have placed Roman coins in the eyes of Jesus, according to strange pagan custom, which also bore the name of the very emperor in his name Jesus was condemned and brutally killed.

Pollen tests and alleged images of plants on the cloth

Pollen examinations were first carried out by forensic scientist Max Frei-Sulzer , later also by Avinoam Danin and Uri Baruch. These botanical investigations are intended to provide information on the place of origin of the woven fabric. They answer neither the question of authenticity nor the time when the shawl was made, since a shawl made in the Orient at a later date may have reached Europe.

For these pollen investigations, Frei-Sulzer took particle samples in 1973 and 1978 by pressing strips of adhesive tape onto the grave shroud. The particles from the samples taken in 1973 are said to contain almost 50 plant pollen, 34 of which are either in Israel (preferably Jerusalem) or Turkey, but not in Western Europe. After Frei-Sulzer's death in 1983, his samples came into the possession of the Sindonologists Association ASSIST ( Association of Scientists and Scholars International for the Shroud of Turin ) and are said to have been passed on from there to the shroud researchers Mary and Alan Whanger. The exact whereabouts are not known. Alan Whanger claims to have discovered images of plants on the shroud with a special technique. Together with the Whangers, Danim and Baruch also came to the conclusion in 1999 that the pollen had got onto the cloth through direct contact with the corresponding plants, some of them came from the immediate vicinity of Jerusalem and the spring time (i.e. Easter ) can be used as the contact period for the pollen types . open up.

The usefulness of the pollen tests and the presence of the plant image on the shroud are seriously questioned. At a conference of forensics experts (INTER / MICRO-82) in 1982, Steven Schafersman pointed out inconsistencies in Frei-Sulzer's data and discrepancies with the data of comparable adhesive tape samples, which had also been taken in 1978 and by McCrone and other STURP -Members have been examined. According to Schafersman, the deviations can only be explained by falsification, i.e. artificial enrichment of Frei-Sulzer's adhesive tape samples with pollen. This renders all tests based on these samples worthless. Schafersman corroborates his accusation with references to possible personal unreliability of Frei-Sulzer. In Switzerland, he is said to have contributed to incorrect and fraudulent reports (for which there were judicial convictions of colleagues) and therefore resigned. Confidence in the seriousness of Frei-Sulzer's work also suffered as a result of his involvement in a false report on the so-called Hitler diaries .

Joe Nickell also suspects contamination of the samples, although Frei-Sulzer does not assume any intention. It is noticeable that the majority of Frei-Sulzer's adhesive tapes hardly contain any pollen and only one adhesive tape contains a great deal of pollen, in addition to that in a place that did not come into contact with the cloth.

The alleged images of parts of plants that Whanger claims to have found are also mostly judged to be pseudoscientific. Whanger is not an expert in optics or optical pattern recognition techniques. The technique he describes is the same with which he claims to have detected Roman coins on the eyes of the shroud image, and is described as unusable. The alleged pictures of plants can only be seen very faintly and can also be interpreted differently. Stephen Epstein, in an article about school didactics in science subjects, suggested using Whanger's controversial technique because of its ease of repetition in school lessons to demonstrate to students the importance of correctly conducted blind tests using this negative example .

Weave of the cloth

The texture of the cloth was examined in 1973 by textile expert Gilbert Raes as part of an Italian expert commission. In the final report of this expert commission published in 1976 ( La S. Sidon: Ricerche e studi della Commissione di Esperti, Diocesi Torinese, Turin, 1976), Raes comes to the conclusion:

“At the beginning of the Christian era, both cotton and linen were known in the Middle East. The weave is not particularly specific and does not allow us to determine the time period in which it was made. "

and

“On the basis of the above observation, we can say that we have no precise indications which would allow us to conclude without a shadow of doubt that the fabric cannot be dated back to the time of Christ. On the other hand, it is also not possible to confirm that the fabric was actually woven during this time. "

The Swiss textile specialist Mechthild Flury-Lemberg , who carried out conservation work on the cloth in the summer of 2002, states that the weave of the cloth is a three-to-one herringbone pattern . Herringbone patterns are also known from the Middle Ages, and Flury-Lemberg points out in an interview with the American television channel PBS that a three-to-one herringbone pattern meant exceptional quality in ancient times, while less fine linen in the first century Had a one-on-one herringbone pattern. In the interview, however, she also mentions that there is a seam on one side of the cloth, the pattern of which is similar to the seam of a fabric that was found in the Jewish fortification in Masada and which dates back to 40 BC. And 73 AD. Their conclusion is:

"The linen of the Shroud of Turin shows no weaving or sewing techniques that would speak against its origin as a high-quality product by textile workers in the first century."

As early as the 1980s, Flury-Lemberg was asked about the possibility of dating the shroud by textile analysis. However, since, in their opinion, it is not possible to obtain a reliable dating from a textile analysis alone, they did not commit themselves.

According to researchers from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem , the Turin cloth cannot date from the time of Jesus of Nazareth due to its complex weave. They compared the cloth with a contemporary grave cloth from the 1st century AD, discovered in a Jerusalem crypt, which has a considerably simpler weave.

Examination of injuries and blood stains

The first check of possible traces of blood by serologists took place in 1973 as part of an investigation of the shroud, which was initially kept secret, at the request of Cardinal Michele Pellegrino . Several detection methods were used. The 120-page final report was not published until 1976. It states that all the detection methods used would have given negative results with regard to the presence of blood.

An investigation by Walter McCrone as part of the STURP project also came to the conclusion that it is not blood, but the color pigments ocher and cinnabar used in painting that can be found in the blood images of the cloth. In contrast, John Heller and Alan Adler came to a positive result through chemical tests on comparable samples, and the STURP project endorsed this opinion in its final report. At a 1983 conference, forensic scientist John E. Fischer agreed with McCrones, according to which the positive results of Heller and Adler could also have been caused by organic ingredients and binders such as egg yolk, as found in tempera paint.

Sometimes it is claimed that the blood stains from the head and nail wounds can be analytically differentiated in their nature from the blood residue corresponding to the side wound, insofar as the latter consists of post-mortem blood, while the latter consists of premortal blood. There are also claims that the blood stains can be more closely identified as blood of blood group AB (Baima Bollone 1981). These hypotheses are rated with great reluctance even by other proponents of authenticity; skeptics reject them as unfounded. The blood group was determined using the redox state of iron in the samples and could produce similar results if the measurement did not examine blood residues, but iron-containing color pigments. The claims that L. A. Garza-Valdes made that blood group AB was particularly common among Jews are false. Claims that DNA traces were allegedly found in the blood residues (e.g. from LA Garza-Valdes) are based on unauthorized samples and are also rejected as untrustworthy by Alan Adler, who also affirms the authenticity of the suspected blood residues. Practically everyone who came into contact with the cloth in the past could also have left DNA traces.

There are also hypotheses that allegedly attempt to interpret eye injuries that can be seen on the cloth. According to a reconstruction of the facial injuries, viscous contents of the eye, especially vitreous, would have leaked from one eye and indirectly made the coins listed elsewhere more visible.

Compare with Oviedo's handkerchief and Manoppello's veil

There is no image on the Oviedo handkerchief , an alleged relic dated by radiocarbon dating to the 7th century. From a comparison of the existing traces of blood (allegedly of the same rare blood group AB) on the handkerchief with the corresponding pattern on the shroud, proponents of authenticity conclude that the towels covered the same head. The numerous punctiform wounds are attributed to the crown of thorns at the death of Christ. Avinoam Danin added his result of the analysis of the pollen (see above ) to this investigation . If this were true, it would be in clear contradiction to the radiocarbon dating of both cloths.

On another cloth, the veil of Manoppello in the Italian Abruzzo, there is the image of a man with open eyes, whose facial injuries are covered with those of the cloths of Turin and Oviedo. According to some proponents, the Volto Santo is said to come from the tomb of Jesus with the Turin shroud and the handkerchief of Oviedo and thus from the same person. Due to some similarities, the veil could also have served as a template for the possible manufacturer of the shroud, critics point to the very different fabrics, other welding cloths and related references to falsified relics.

The Catholic Church speaks of icons , not relics, when it comes to the veil and the shroud .

Is a corpse or a living person depicted?

In popular scientific literature , the religious educator H. Kersten and the parapsychologist E. Gruber support the thesis that a living person was wrapped in the shroud, which suggests that Jesus survived the crucifixion. They justify their assertion with the fact that corpses do not bleed like living people, so the blood stain image could only have been created by a living wrapped body. In the serious scientific literature, the theses of Kersten and Gruber play practically no role.

In fact, blood coagulation usually begins shortly after death, but even in a dead body, blood can still leak through a larger wound until it completely coagulates. It is also controversial whether the blood stain images are really blood. In addition, blood could also have been applied artificially.

Garlaschelli tried to make an impression

In 2009, the Italian chemist Luigi Garlaschelli made a replica of the cloth by artificially aging a linen fabric made using medieval methods through washing and boiling. He put the cloth over a volunteer and rubbed its outlines with an acidic pigment paste of reddish color, as it was known in the Middle Ages. After the dyes had acted for about thirty minutes, an image of the volunteer remained on the cloth, which Garlaschelli finished with traces of blood, burn holes and water stains. The result showed a strong resemblance to the real shroud.

Similar objects

literature

Books

- Karl Braun , Barbara Stühlmeyer : The Turin shroud. Fascination and facts. Butzon & Bercker Kevelaer 2018, ISBN 978-3-7666-2534-2 .

- Andrea Nicolotti: From the Mandylion of Edessa to the Shroud of Turin. The Metamorphosis and Manipulation of a Legend (= Art and Material Culture in Medieval and Renaissance Europe, Vol. 1) , Brill, 2014. ISBN 978-90-04-26919-4

- Paul Badde : The Shroud of Turin. Pattloch Verlag, Munich 2010. ISBN 978-3-629-02261-5

- Nello Balossino: The image on the Turin shroud: photographic examination and information study. Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2000, ISBN 3-7954-1334-6

- Hans Belting : Image and cult: a history of the image before the age of art. Beck, Munich 1990, ISBN 3-406-37768-8

- Paul-Eric Blanrue: Le Secret du Suaire - autopsy d'une escroquerie. Pygmalion, 2006

- Werner Bulst SJ: Fraud on the Turin shroud. The manipulated carbon test. Knecht, Frankfurt am Main 1990, ISBN 3-7820-0609-7 (with ecclesiastical printing permission)

- Harry Gove : Relic, Icon or Hoax? Carbon Dating the Turin Shroud. Institute of Physics Publishing, Bristol 1996, ISBN 978-0-7503-0398-9

- Markus von Hänsel-Hohenhausen: From the face in the world. Thoughts on Identity in the 21st Century. Frankfurter Verlagsgruppe, Frankfurt am Main 2005, ISBN 3-937909-54-0 (with a focus on the Turin shroud ), full text: THE COORDINATION OF KNOWLEDGE AND FAITH (COORDINATE MAGISTERIA)

- Karl Herbst: Crime Golgotha. Econ, Berlin 1992, ISBN 3-430-14355-1

- Michael Hesemann : The silent witnesses from Golgotha. The fascinating story of Christ's passion relics. Hugendubel, Munich 2000, ISBN 3-7205-2139-7

- Michael Hesemann: Stigmata. They bear the wounds of Christ. Silberschnur, Neuwied 2006, ISBN 3-89845-125-9

- Markus van den Hövel : The true face of Jesus Christ: the shroud of Turin and the veil of Manoppello . Be & Be, Heiligenkreuz im Wienerwald 2010, ISBN 978-3-902694-22-5

- RW Hynek : Golgotha. In the testimony of the Turin Shroud , Badenia, Karlsruhe 1950

- Christopher Knight, Robert Lomas: The Shroud of Turin, the Templars and the Secret of the Freemasons. Scherz, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-502-15378-7

- Bernd Kollmann : The Shroud of Turin - A Portrait of Jesus? Myths and Facts. Herder, Freiburg i. Br. 2010, ISBN 978-3-451-06216-2 .

- Roman Laussermayer: Meta-physics of the radiocarbon dating of the Turin shroud. Publishing house for science and research, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-89700-263-9

- Alexander Lohner: The cloth of Jesus. Structure, Berlin 2005, ISBN 978-3-7466-2122-7

- Walter C. McCrone : Judgment day for the Shroud of Turin. Prometheus Books, Amherst / NY 1999, ISBN 1-57392-679-5

- Lynn Picknett, Clive Prince: The Jesus Forgery. Leonardo da Vinci and the Turin Shroud. Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1995, ISBN 3-7857-0773-8

- Joseph Sauer : The oldest images of Christ. Wasmuth, Berlin 1920

- Blandina Paschalis Schlömer : The Veil of Manoppello and the Shroud of Turin. Resch, Innsbruck 1999, ISBN 3-85382-068-9

- Maria Grazia Siliato: And the shroud is real: the new evidence. Heyne, Munich 2002, ISBN 3-453-16501-2

- David Sox: The Shroud Unmasked. The Canterbury Press, Scoresby 1988, ISBN 0-947293-07-8

- Ian Wilson : Das Turiner Grabtuch , Wilhelm Goldmann, Munich 1999, ISBN 3-442-15010-8

- Ian Wilson: The Shroud , Bantam Press, London 2010, ISBN 978-0-593-06359-0

Essays

- PE Damon et al. a .: Radiocarbon dating of the Shroud of Turin . In: Nature , 1989, vol. 337, pp. 611-615.

- Mary Warner: The Shroud of Turin . In: Analytical Chemistry , 1989, Vol. 61, 2, 101A

- Amardeo Sarma: a cloth with seven seals? The Turin Shroud as an object of research . 2000. In: Skeptiker , issue 00-2.

- Stephan Matthiesen: Doubts about the age of the Turin shroud, January 30, 2005. Reprinted in Skeptiker , Heft 05-4, pp. 164–165.

- Jacques Evin: La datation radiocarbone du Linceul de Turin . In: Dossiers d'Archéologie. , No. 306, September 2005, ISSN 1141-7137 , pp. 60-65

- Daniel Raffard de Brienne: La désinformation autour du Linceul de Turin. Éditions de Paris, Paris 2004. ISBN 2-85162-149-1 .

- Raymond Rogers: A Chemist's Perspective On The Shroud of Turin , 2008, ISBN 978-0-615-23928-6

- Raymond Rogers: Studies on the radiocarbon sample from the shroud of turin , 2004, ( PDF file ), in: Thermochimica Acta 425 (2005) 189–194

- M. Sue Benford, Joseph G. Marino: Discrepancies in the radiocarbon dating area of the Turin shroud , July / August 2008, ( PDF ), in: Chemistry Today. Vol 26 no 4

Web links

- Official website for the exhibition of the Shroud of Christ in Turin

- Website of the "Shroud of Turin Research Project" (STURP)

- ZDF Expedition, November 19, 2006, Sphinx: The Man on the Shroud - with new findings and documents ( Memento from December 14, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- McCrone Research Institute website, et al. a. with microphotographic images of the shroud and comparison samples

- Website on the Volto Santo and the Turin Shroud

Individual evidence

- ^ B. Ruffin, 1999 ISBN 0-87973-617-8

- ↑ a b c d Walter McCrone in: Vienna Reports on Natural Science in Art 1987/1988, 4/5, 50.

- ^ "The Shroud of Turin is the single, most studied artifact in human history" statement considered as "widely accepted" in Lloyd A. Currie: "The Remarkable Metrological History of Radiocarbon Dating [II]", J. Res. Natl. Inst. Stand. Technol. 109, 2004, p. 200, Article (PDF; 3.8 MB).

- ^ William Meacham: The Authentication of the Turin Shroud: An Issue in Archaeological Epistemology , Current Anthropology , Volume 24, No 3, June 1983. The Authentication of the Turin Shroud: An Issue in Archaeological Epistemology

- ^ Brian Haughton: Hidden History . 2007, ISBN 1-56414-897-1 , pp. 117 .

- ^ Ian Wilson: Highlights of the Undisputed History

- ↑ Ian Wilson: The Mysterious Shroud . Doubleday, Garden City (New York) 1986.

- ↑ Documentation by ZDF on the Turin Shroud ( Memento from December 3, 2016 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ These 30 patches were removed by a textile expert in 2002, so that the Turin shroud looks different on the edge than on all the older photos.

- ↑ Historians: Hitler wanted to steal the Turin shroud. kath.net, April 6, 2010

- ↑ Report on the exhibition of the Turin Shroud 2010 on kath.net

- ^ Pope's message on the Turin Shroud ( Memento from April 2, 2013 in the Internet Archive ), Vatican Radio March 30, 2013

- ^ Communication ( memento of December 9, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) on the exhibition of the Turin Shroud 2015 on sindone.org

- ↑ Special exhibition of the Turin Shroud Vatican News from August 11, 2018, accessed on August 13, 2018

- ↑ Diretta streaming della Contemplazione della Sindone di Torino (Italian).

-

^ Ian Wilson: The Shroud of Turin: the Burial Cloth of Jesus Christ? Doubleday & Company, New York 1978;

ders .: The Mysterious Shroud. Doubleday, New York 1986. - ↑ Robert of Clari's account of the Fourth Crusade, chapter 92: And on every Friday that shroud did raise itself upright, so that the form of Our Lord could clearly be seen. ( Memento of August 3, 2003 in the Internet Archive ). On Wilson's thesis that the idol allegedly venerated by the Knights Templar is identical to the Turin cloth, cf. most recently Karlheinz Dietz , The Templars and the Turin Shroud . In: Karl Borchardt, Karoline Döring, Philippe Josserand, Helen J. Nicholson (eds.): The Templars and Their Sources (= Crusades - Subsidia . Vol. 10). Routledge, London 2017, ISBN 978-1-315-47529-5 (e-book; limited, unpaginated preview in Google book search).

- ↑ Averil Cameron: The Skeptic and the Shroud . King's College Inaugural Lecture monograph, London 1980

- ↑ Averil Cameron: The mandylion and Byzantine Iconoclasm. In H. Kessler, G. Wolf (Ed.): The holy face and the paradox of representation. Bologna 1998, pp. 33-54

- ↑ N. Currer-Briggs: Shroud Mafia. The Creation of a Relic? The Book Guild, 1995, ISBN 1-85776-005-0 , pp. 169/170 .

-

↑ Turin shroud "Leonardo created God in his image" www.derStandard.at of July 3, 2009

Vittoria Haziel: La passione secondo Leonardo . Il genio di Vinci e la Sindone di Torino. 2005, ISBN 88-8274-939-8 . - ^ H. Gove: Relic, Icon or Hoax? P. 38

- ^ Joe Nickell Voice of Reason: The Truth Behind the Shroud of Turin

- ↑ Steven Schafersman: A Skeptic's View of the Shroud of Turin. History, Iconography, Photography, Blood, Pigment, and Pollen. (PDF)

- ↑ J. P Jackson, E. J. Jumper, W. R. Ercoline: Correlation of image intensity on the Turin Shroud with the 3-D structure of a human body shape. In: Applied Optics. Volume 23, 1984, pp. 2244-2270

-

^ Nicholas P. L. Allen: Is the Shroud of Turin the first recorded photograph? In: The South African Journal of Art History. November 11, 1993, pp. 23-32

Nicholas P. L. Allen: The methods and techniques employed in the manufacture of the Shroud of Turin. Unpublished DPhil thesis, University of Durban-Westville , 1993 -

↑ Nicholas P. L. Allen: A reappraisal of late thirteenth-century responses to the Shroud of Lirey-Chambéry-Turin: encolpia of the Eucharist, vera eikon or supreme relic? In: The Southern African Journal of Medieval and Renaissance Studies. 4 (1), 1994, pp. 62-94.

Nicholas P. L. Allen: Verification of the Nature and Causes of the Photo-negative Images on the Shroud of Lirey-Chambéry-Turin. - ↑ Photo History - Finding the chemistry ( Memento of February 7, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ The history of glasses. in the Virtual Museum of Ophthalmic Optics ( Memento from June 21, 2013 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Richard Burleigh, Morven Leese, Michael Tite: An intercomparison of some AMS and small gas counter laboratories . In: Radiocarbon . tape 28 , 2A, 1986, pp. 571-577 ( PDF ).

- ^ PE Damon et al: Radiocarbon dating of the Shroud of Turin . In: Nature . tape 337 , no. 6208 , February 16, 1989, p. 611-615 , doi : 10.1038 / 337611a0 .

- ↑ J. Andres Christians: Summarizing a Set of Radiocarbon Determinations: A Robust Approach . In: Journal of the Royal Statistical Society C . tape 43 , no. 3 , January 1994, pp. 489-503 , doi : 10.2307 / 2986273 .

- ↑ LA Currie: The Remarkable Metrological History of Radiocarbon Dating [II] . In: Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology . tape 109 , no. 2 , 2004, p. 185-217 , doi : 10.6028 / jres.109.013 .

- ^ R. E. M. Hedges: A Note Concerning the Application of Radiocarbon Dating to the Turin Shroud. In: Approfondimento Sindone. 1, 1997, pp. 1-8

- ↑ Harry Gove: Relic, Icon or Hoax? Carbon Dating the Turin Shroud. Institute of Physics Publishing, Bristol 1996, ISBN 978-0-7503-0398-9

- ^ Raymond N. Rogers: Studies on the radiocarbon sample from the shroud of turin. In: Thermochimica Acta. Volume 425, 2005, pp. 189–194 (PDF; 228 kB)

- ↑ MS Benford, JG Marino: Discrepancies in the radiocarbon dating area of the Turin shroud . In: Chemistry Today • vol 26 n 4 / July-August 2008 (PDF; 1.2 MB)

- ↑ a b Stephan Matthiesen: Doubts about the age of the Turin grave book. Novel dating method raises questions. ( Memento from February 12, 2005 in the Internet Archive ) Current message from the Society for Anomalistics e. V. , January 30, 2005

- ↑ Steven Schafersman: A Skeptical Response to Ray Rogers Thermochimica Acta paper on the Shroud of Turin.

- ↑ John L. Ateo, Rachel C. Ateo: Rev. Father Francois Laisne 'Shroud of Turin' Apologist.

- ^ Mechthild Flury-Lemberg: The Invisible Mending of the Shroud, the Theory and the Reality . (PDF; 31 kB)

- ↑ Marco Bellaa, Luigi Garlaschellib, Roberto Samperia: There is no mass spectrometry evidence that the C14 sample from the Shroud of Turin comes from a "medieval invisible mending." In: Thermochimica Acta 617 (2015), pp. 169ff.

- ^ HE Gove, S. J. Mattingly, A. R. David, L. A. Garza-Valdes: A problematic source of organic contamination of linen. In: Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research B. 123, 1997, pp. 504-507

- ↑ DA Kouznetsov, A. A. Ivanov, P. R. Veletsky: Effects of fires and biofractionation of carbon isotopes on results of radiocarbon dating of old textiles. The Shroud of Turin. In: Journal of Archaeological Science. 23, 1996, pp. 109-121

- ↑ AJT Jull, D.J. Donahue, P.E. Damon: Factors Affecting the Apparent Radiocarbon Age of Textiles. A Comment on “Effects of Fires and Biofractionation of Carbon Isotopes on Results of Radiocarbon Dating of Old Textiles. The Shroud of Turin ”, by D.A. Kouznetsov et al. In: Journal of Archaeological Science. 23, 1996, pp. 157-160

- ↑ Gian Marco Rinaldi found during research (see M. Polidoro: Notes on a Strange World, The Case of the Holy Fraudster. ( Memento of May 6, 2004 in the Internet Archive )) in the work of Kuznetsov a large number of quotes from scientific articles which do not exist. In addition, there are no museums from which Kuznetsov claims to have received the alleged samples for his research, and many other inconsistencies. Even before his "career" in Sindonology, D. Kuznetsov had proven scientific falsifications (Dan Larhammar: Severe Flaws in Scientific Study Criticizing Evolution. In: Skeptical Inquirer. 19, No. 2, 1995)

- ↑ Holger Kersten and Elmar R. Gruber: The Jesus plot. The truth about the "Turin Shroud" , Munich 1992, ISBN 3-7844-2420-1

- ^ Karl Herbst: Criminal case Golgotha. The Vatican, the Turin Shroud and the real Jesus , Düsseldorf - Vienna - New York 1992, ISBN 978-3-430-14355-4

- ↑ “Many of you here in continental Europe have opted for there having been some kind of clandestine switch of the samples used for the dating, basically, that Dr. Michael Tite and / or his colleagues in some way conspired to pervert the truth. If that is what you still believe, then I can only disagree with you most strongly. " from Ian Wilson An Appraisal of the Mistakes Made Regarding the Shroud Samples Taken in 1988 - and a Suggested Way of Putting These Behind Us 1999

- ^ H. Gove: Relic, Icon or Hoax

- ^ TJ Phillips: Shroud irradiated with neutrons ?. In: Nature. 337, 1989, p. 594. doi : 10.1038 / 337594a0 ( PDF )

- ↑ REM Hedges: Shroud irradiated with neutrons? - reply. In: Nature. 337, 1989, p. 594

- ^ HE Gove: Dating the turin shroud - an assessment . In: Radiocarbon . tape 32 , no. 1 , 1990, p. 87-92 .

- ^ A Coghlan: Neutron Theory fails to resurrect the Turin Shroud. In: New Scientist. 121, 1989, p. 28

- ↑ Nello Balossino: The image on the Turin grave cloth: Photographic Evaluation and Information study. Schnell & Steiner, Regensburg 2000, ISBN 3-7954-1334-6

- ^ Jacques di Costanzo: Science & Vie. 2005

- ↑ z. B. already argues Silvio Curto in La S. Sidon: Ricerche e studi della Commissione di Esperti in this way

- ↑ Discussion of authenticity and research results in a historical overview - Diploma thesis (2000) by Arabella Martínez Miranda ( Memento from March 18, 2009 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ Christoph Daxelmüller : "Sweet nails of passion". The history of the self-crucifixion of Francis of Assisi until today. Patmos, Düsseldorf 2001, ISBN 3-491-70336-0 , pp. 19-21, 26.

- ^ Frederick T. Zugibe: Pierre Barbet Revisited Sindon NS, Quad. No. 8, 1995.

- ↑ Christoph Daxelmüller: "Sweet nails of passion". The history of the self-crucifixion of Francis of Assisi until today. Patmos, Düsseldorf 2001, p. 26.

- ↑ Christoph Daxelmüller: "Sweet nails of passion". The history of the self-crucifixion of Francis of Assisi until today. Patmos, Düsseldorf 2001, p. 45 f.

- ↑ N. Currer-Briggs: Shroud Mafia. The Creation of a Relic? The Book Guild, Lewes 1995, ISBN 1-85776-005-0 , pp. 174 f.

- ↑ Christoph Daxelmüller: "Sweet nails of passion". The history of the self-crucifixion of Francis of Assisi until today. Patmos, Düsseldorf 2001, pp. 89-97.

- ^ G. Fanti, R. Maggiolo: The double superficiality of the frontal image of the Turin Shroud. In: Journal of Optics A: Pure and Applied Optics. 6, 2004, pp. 491-503

- ^ A. Marion: Discovery of inscriptions on the shroud of Turin by digital image processing. In: Optical Engineering. 37, 1998, p. 2313

- ↑ Photo ( Memento from June 22, 2006 in the Internet Archive )

- ↑ "Some paleographists already consider that the characters, similar to epigraphic characters, are oriental rather than occidental and antique rather than medieval, probably dating from the first centuries of our era." A. Marion: Discovery of inscriptions on the shroud of Turin.

- ↑ Text on Turin Shroud? 20 minutes, November 20, 2009, accessed August 16, 2015 .

- ↑ Rachel Hachlili, Ann Killebrew: 'Was the Coin-on-Eye Custom a Jewish Burial Practice in the Second Temple Period?', The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 46, no. 3 (Summer, 1983), pp. 147-153

- ↑ Jackson, Jumper, Mottern, Stevenson "The three dimensional image on Jesus' burial cloth" Proceedings of the 1977 United States Conference of Research on the Shroud of Turin, Holy Shroud Guild, 1977

- ↑ J. P Jackson, EJ Jumper, WR Ercoline: Correlation of image intensity on the Turin Shroud with the 3-D structure of a human body shape. In: Applied Optics. Volume 23, 1984, pp. 2244-2270

- ^ Francis S. Filas: The Dating of The Shroud of Turin From Coins of Pontius Pilate. Privately Published, Distributed by Cogan Productions, ACTA Foundation, Arizona, 1982

- ↑ Cf. Frederic William Madden (1839–1904): History of Jewish Coinage and of Money in the Old and New Testament. London 1864 (reprint: KTAV Publishing House, New York 1967), p. 149, fig. 14 and 15 in Google Book Search.

- ↑ Johannes von Dohnanyi : In close contact with Jesus. In: Die Zeit 52/1988, December 23, 1988.