St. Matthew Passion (JS Bach)

The St. Matthew Passion , BWV 244, is an oratorio passion by Johann Sebastian Bach . The account of the suffering and death of Jesus Christ according to the Gospel according to Matthew forms the backbone. It is supplemented by interspersed passion chorales and edifying poems by Picander in free choirs and arias. The St. Matthew Passion and the St. John Passion are the only two completely preserved authentic Passion works by Bach. With over 150 minutes of performance and a line-up of soloists, two choirs and two orchestras, theMatthäus-Passion Bach's most extensive and strongest work and represents a high point of Protestant church music. The premiere took place on April 11, 1727 in the Thomaskirche in Leipzig . After Bach's death the work was forgotten. The re-performance in an abridged version under Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy in 1829 ushered in the Bach renaissance .

Origin and history

background

In the Christian community, the biblical story of the Passion was given great importance from the beginning, since the suffering and death of Christ were of central importance. These passages of the Bible received special attention in the celebration of the Eucharist and in the liturgy of the church year through a solemn talk. Dramatization has probably taken place since the 5th century by distributing it to different roles (evangelist, Jesus, Pontius Pilate and others). Heinrich Schütz assigned these people different voices and made the groups of people appear as a polyphonic choir. In southern Germany, towards the end of the 16th century, the tradition of interrupting the Passion account with chorales sung by the congregation arose. Free poetic pieces such as chorales and arias were added from the 17th century.

At the end of the Baroque period , the Passion events were set to music in three different ways: by means of the Passion cantata , the Passion Oratorio as a free adaptation , and the “Oratorical Passion”. Bach chose the latter genre for the St. John and St. Matthew Passions . For a period of about 100 years (1669–1766) there was a tradition in Leipzig of solemnly reciting the Passion texts in the morning service by singing the Gospel text in the manner of Gregorian chant . Polyphonic singing (" figuraliter ") was only allowed in the New Church in 1717, in St. Thomas in 1721, in St. Nikolai in 1724 , and then alternately in the two main churches. The passion music took place in the four to five-hour Vespers service from 2 p.m. after the morning service from 7 a.m. to 11 a.m. In contrast to today's performance practice, Bach's passions were part of the service and not intended as concert music.

premiere

Until 1975, the year 1729 was assumed to be the year of origin, but it is now undisputed that the first performance of the St. Matthew Passion took place on Good Friday of 1727, i.e. on April 11, 1727. Carl Friedrich Zelter already commented on the re-performance on the 100th anniversary of the Passion by Mendelssohn Bartholdy in 1829, the question was raised, “… was this performance the very first? does not say the old church text of the year mentioned ”. In 1975 Joshua Rifkin proved that the first performance was in 1727 and that on Good Friday in 1729 the Passion was on the program for the second time. The St. Matthew Passion was played in a revised version in 1736 and possibly also in 1740 (or 1742).

With the date 1727 the relationship to the missing and u. a. In 2010, Alexander Ferdinand Grychtolik reconstructed the cantata Klagt, Kinder, Klagen es der Welt (BWV 244a), the so-called Köthener funeral music (for Prince Leopold von Anhalt-Köthen ), clarified. The princely funeral music was performed on March 24, 1729. The parody model here is therefore the St. Matthew Passion , from which Bach took two choirs and seven arias. Against this background, the widespread idea that Bach never parodied his sacred music into the secular cannot be upheld. However, princely funeral music is not necessarily to be classified as profane; the funeral music mixes spiritual and secular aspects. In addition, pragmatic reasons are suspected: Since the text had to be approved in advance and the music had to be rehearsed, Bach had no time for a completely new composition.

Bach had committed themselves when he took office in 1723 to design the church music so that "they not last zulang, also may Being so constituted, so they do not come out opernhafftig but the audience rather encouraging lower to worship." After Bach in 1724's St. John Passion performed for the first time and in a revised version in 1725, he conducted the Markus Passion by Friedrich Nicolaus Bruhns (1702) in 1726 , to which he added chorals and adapted for Leipzig practice. The St. Matthew Passion exceeds Bach's St. John Passion by a third of the length and thanks to the double-choir structure. It was performed a few times during Bach's lifetime, but not a single reaction from the parish, the city of Leipzig or music lovers has been recorded. There is no reference to a performance or the significance of the work in the local press or in people close to Bach. Apparently the work was largely ignored by contemporaries.

Work versions

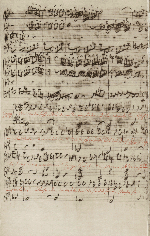

The version of the work that is considered to be valid today and on which most of today's performances are based is from 1736. It is available in a fair copy from the second half of the 1730s, which is considered to be Bach's most beautiful and most careful autograph and indicates the great importance that he himself had to the Attached work. The symbolism of the use of red ink for the pure Bible word and the opening chorale “ O Lamb of God innocent ” is unique to him. After the death of his father, Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach inherited this and numerous other manuscripts, which subsequently came into the possession of the private scholar Georg Poelchau . The score now belongs to the Berlin State Library and is one of its most precious original manuscripts. Preservation using the paper splitting process turned out to be time-consuming and cost-intensive .

The early version of the St. Matthew Passion BWV 244b from 1729 follows a recently evaluated copy of the score by Johann Christoph Farlau from around 1755/1756, which is now also in the Berlin State Library. It was first performed again in March 2000 by the St. Thomas' Choir and the Gewandhaus Orchestra under Thomas Cantor Georg Christoph Biller in Sapporo, Japan, and has been recorded with these ensembles since March 2007. In the early version, the division of the two choirs - it also affects the instruments - is not yet fully completed, because both choirs use a common continuo part with an organ. In addition, Johann Christoph Farlau wrote out the accompaniment of the Evangelist part in long notes - just as Bach himself did with the score of the later version, while he gave shorter notes for the individual parts. In the first version, the later chorale No. 23 “I want to stand here with you” is replaced by the stanza “It serves for my joys”. Bach made the most serious change at the end of the first part: instead of the large-scale chorale arrangement “O man, weep your sin great” (No. 35), which originally introduced the St. John Passion, the simple version of the St. Matthew Passion rang out in the first version Chorale "I will not leave Jesus from me". In almost every movement of the Passion there are also detailed differences in the musical text, text underlay or scoring. So the opening aria of the second part is sung by the bass, in Arioso and Aria “Yes, of course, the flesh and blood wants in us” / “Come, sweet cross”, a lute is required instead of a viol . In the opening choir it is questionable whether the cantus firmus chorale “O Lamm Gottes Innocent” , which Bach added, was sung at all in 1729, since it is also heard here as an instrumental quotation in the woodwinds. In addition, in the Arioso “O pain!”, Transverse flutes take over the roles of the recorders used only here in the late version.

reception

Some cantional movements of the St. Matthew Passion appeared in chant collections published by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. In addition to a few movements from other works by his father, he himself took over three chorales and seven choral movements from the St. Matthew Passion for his Passion pasticcio , which was performed several times in Hamburg between 1769 and 1787.

From 1829 there was a Bach renaissance with the first re-performance of the St. Matthew Passion after Bach's death in a version shortened by about half, conducted by Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy with the Sing-Akademie zu Berlin , which comprised around 150 singers and a few Weeks later in Frankfurt am Main with the Cäcilien-Verein . In particular, arias and chorales have been deleted in favor of the dramatic parts, some movements have been re-instrumented, but in contrast to Zelter's performances, the text has not been repositioned. Mendelssohn Bartholdy had a copy of Bach's original score. He himself accompanied the recitatives on a fortepiano , as no organ was available. The work was first printed in 1830 by the Schlesinger publishing house. After 1829, Bach's works were played annually in concerts until 1840, after which they were played irregularly. Further reception in the 19th century was laborious and by no means continuous. The Vienna premiere took place in 1865 , with the chamber singer Gustav Gunz singing the Evangelist. Mendelssohn Bartholdy's commitment to Bach's music reminded the general public of his importance and contributed to the foundation of the Leipzig Bach Society in 1850. At the end of the 19th century, the St. Matthew Passion had firmly established itself as part of the commercial concerts of the urban bourgeoisie, with the aim of achieving a symphonic sound. Colossal line-ups with 300 to 400 musicians were the rule throughout the 19th century. It was not until 1912 that the unabridged version was performed, which is the norm today.

In 1921, Ferruccio Busoni proposed a staged performance of the St. Matthew Passion after the first production had already been planned by the English director and set designer Edward Gordon Craig in 1914, but could not be implemented due to the outbreak of the First World War . According to Busoni, the arias should largely be deleted for this purpose, since they "unduly delay the action and [...] interrupt". He designed a stage set on two levels, comparable to the Piscator stage , in order to be able to depict several processes at the same time, with a pulpit in the center and a Gothic cathedral on both sides for the choir. In 1930 Max Eduard Liehburg published a script for the staging of Bach's two great Passions, which provided for three levels. None of these designs were realized. John Neumeier performed the St. Matthew Passion as a ballet in Hamburg in 1981 , the choreography of which is considered to be trend-setting.

The St. Matthew Passion was filmed for the first time in 1949, by Ernst Marischka ; Max Simonischek made a second film in 2006.

"Make yourself, my heart, pure" was also reflected in popular music: Michel Magne composed the chanson "Cent Mille ", later made famous worldwide by the French singer Frida Boccara, based on the Bach model for the Vadim film "Repos du Guerrier" Chansons ".

In the 20th century, numerous very different recordings were made with well-known conductors and artists (including in modern performances: Wilhelm Furtwängler , Karl Richter , Otto Klemperer , Rudolf Mauersberger , Peter Schreier , Helmuth Rilling , Georg Solti , Enoch zu Guttenberg , Karl-Friedrich Beringer and in historical performance practice : Nikolaus Harnoncourt , Gustav Leonhardt , Ton Koopman , John Eliot Gardiner , Philippe Herreweghe , Masaaki Suzuki ). They show the wide spectrum of possible interpretations, ranging from conventional casts to monumental versions in the romantic tradition or small casts as an expression of historical performance practice. Attempts in the 1980s to restore the liturgical framework for the Passion were isolated cases.

construction

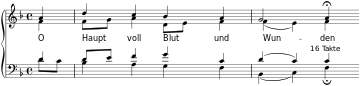

The monumental, dramatic-epic work unfolds its impressive stereophonic effect through the double system of choir and orchestra, in which the choirs often conduct a dialogue with one another. Both parts of the work are framed by large-scale entrance and final choirs, of which the overwhelming entrance choir stands out and has remained without parallel. In between there are many contemplative arias of manageable length that internalize the suffering of Jesus. Between recitatives, choirs and arias, the chorales are incorporated, which refer to the dramatic climaxes of the plot. The chorale O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden by Paul Gerhardt plays a central role here , with various stanzas and harmonizations being played five times and giving the work a sense of unity.

The work consists of a slightly shorter first part, which deals with the murder plans of the Jewish Synhedrion , Jesus' anointing in Bethany, the last Passover meal and the imprisonment in Gethsemane , and a more extensive second part, that of the interrogation before the Jewish council, the denial of Peter, the condemnation by Pilate, the mockery of Jesus, as well as the crucifixion , death and burial reported. In Bach's time, the sermon lasted about an hour between the two parts.

Picander divided his poetry into 15 scenes by headings, while the traditional division of the Passion story is based on five acts : garden, priest, Pilate, crucifixion and burial. Such sections are still recognizable in Bach's St. Matthew Passion , but they take a back seat in view of the unity of the overall layout. Bach himself inscribed the Passion with the title page of his fair copy (mostly 1736) Passio Domini Nostri JC Secundum Evangelistam Matthaeum Poesia per Dominum Henrici alias Picander dictus Musica di GS Bach Prima Parte ("Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ after the Evangelist Matthew, poem by Henrici, Picander called, music by JS Bach, first part ”) and the second part with Passionis DNJC secundum Matthaeum a due Cori Parte Secunda (“ Passion of our Lord Jesus Christ according to Matthew for two choirs, second part ”).

Bach divides the ongoing Bible text from the Gospel of Matthew into 28 sections, which are interrupted by the chorales and free poems, in order to cancel out time and to overcome the distance between the unique Passion event and the presence of the audience. In his St. Matthew Passion , Bach uses the same formal elements as in his St. John Passion and the oratorios ( Christmas Oratorio , Ascension Oratorio and Easter Oratorio ). Due to the length and the many narrative sections, however, there is a stronger emphasis on the epic .

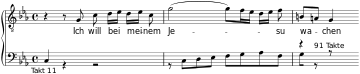

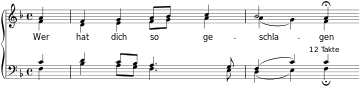

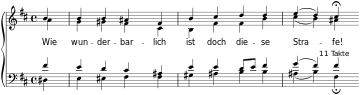

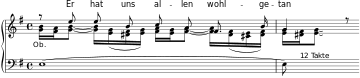

Often, keyword combinations link the biblical text with the arias and the chorales, so that the impression of a sequence of individual pieces is not created, as in the case of the number opera , but a coherent whole with a developing plot. On the other hand, the bridge to today is being built. Choral No. 16 answers the question of the frightened disciples about the traitor (“Lord, is it me?”) With: “It's me, I should atone” and relates it to the listener. Similarly, Jesus' request to the tired disciples “stay here and watch with me!” (No. 24) is complied with in the following recitative (“how gladly I stayed here!”) And in aria no. 26 the answer is given to the believer put in the mouth: “I want to watch over my Jesus”, while choir II flanked it: “So our sins fall asleep”. The last words in recitative no. 30, to obey the will of his heavenly Father even in suffering (“so be it your will”), is followed by chorale no. 31: “What my God wants, always be, his will, which is the best ”who encourages the church to be equally confident. The mocking question “who is it who hit you?” Takes up the chorale no. 44: “Who hit you like that”. When Pilate asks, in view of the obvious innocence of Jesus: “What bad thing has he done?”, Accompagnato No. 57 gives the answer “He has done us all good [...]” and lists some good deeds as examples in order to count with the result conclude: "Otherwise my Jesus did nothing". The mistreatment of Jesus by the soldiers (“and struck his head with it”) is followed by chorale no. 63 “O head full of blood and wounds”.

Musical forms

The three different types of text in the libretto are each given their own form of composition: (1) Biblical texts form the text template for the recitatives and the choruses of the Bible and stand for the dramatic moments. The biblical word has the function of narration (narratio) . (2) Free poems are encountered in the Accompagnato recitatives, in which what happened is explained and theologically interpreted (explicatio) , while in the arias and free choirs meditation and appropriation (applicatio) take place. (3) Church lyrics used in the Bach chorales for the choir, serve the community as a summary confirmation and canned response. In detail, the following musical forms can be found in the St. Matthew Passion :

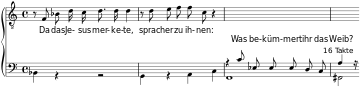

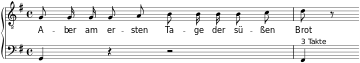

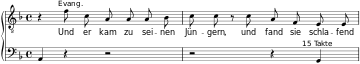

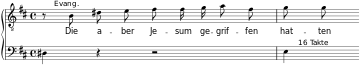

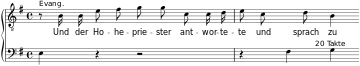

- Secco recitative : The backbone of the Passion is formed by the recitatives in which the evangelist tells the biblical text literally. According to ancient church tradition, it is sung by a tenor. Bach sets the reporting Bible texts to music with the help of secco recitatives, which are only carried by the continuo group without any further instrumental accompaniment. As a rule, the evangelist recitatives set the text syllabically to music ; Melisms are used in meaningful words to illustrate the statement, for example the “crucified” in No. 2, “building” in No. 39 and “weeping” in No. 46. Compared to the St. John Passion , the recitatives are fewer onomatopoeic and there are rarely melismatic designs. Verbatim speeches in the Bible text are assigned to certain soloists , the soliloquents , who appear as Dramatis personae .

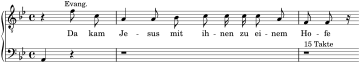

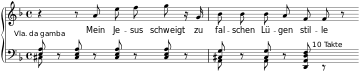

- Arioso : The words of Jesus , on the other hand, are not composed as “secco”, but rather solemnly accompanied by a four-part string set. This makes them stand out from the evangelist report and the individuals who only appear with simple continuo accompaniment. They have the effect of a halo and embody the divine presence.

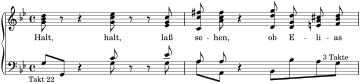

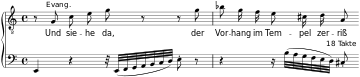

- Turba (“people”, “noise”): groups of people are represented by turba choirs, which Bach effectively uses as dramatic climaxes. The turbae interrupt the recitative 19 times, 13 of which are composed of eight voices. They are used when groups of people appear in the biblical narrative text, be it the disciples, the soldiers, the priests or the masses. In terms of musical implementation, these folk choirs range from the homophonic No. 71 (“Der rufet dem Elijah” and “Halt! Let's see”) and the diminished seventh chord in the dramatic outcry “Barrabam!” (In No. 54) to virtuoso polyphony in the motetic style ( Stile antico ) . A completely unanimous choir and orchestra passage can be heard only once, namely when Jesus is quoted as a confession with the words: "I am the Son of God" (No. 67). Some turbae like the two choirs “Let him crucify” (Nos. 54 and 59), with their excessive intervals, dissonances and expressive harmonies, go to the limit of what was musically reasonable at the time.

- Accompagnato-Recitative : The instrumentally accompanied Accompagnato-Recitative occupies a middle position between recitative and aria, is very close to the Arioso and is also referred to as "Motif Accompagnato" or "Motif Accompagnato". Usually a repeating figure like an ostinato pervades the Accompagnato. In the St. Matthew Passion it serves ten times as a guide to the following aria and prepares its affect and statement. No. 77 has a different function and unites all four soloists before the final choir as in an opera finale. At these Accompagnatos no biblical texts but free poems are set to music. The pitch is not fixed, but always the same as in the subsequent aria. Instrumentation and musical form are extremely diverse. It is also possible to modulate in another key (No. 9, 25, 57, 60, 65, 77).

- Aria : Musically and theologically, the 15 arias form the heart of the Passion. They are based on free seals. The dramatic course of action pauses and aims at comforting encouragement and personal encouragement. Or the listener is asked to internalize the claim of the event and to reflect it morally in action. Two arias are written for tenor, three for soprano, four for bass and five for alto; No. 33 is a duet , No. 26, 33, 36 and 70 have choir inserts. The four arias in the first part without a choir insert (nos. 10, 12, 19, 29) are pure da capo arias according to the ABA scheme, while in the second part only nr. 61 calls for da capo and the other eight the A- Modify parts in each individual way or are completely composed.

- Chorales : They are based on the melodies of the traditional Passion songs from the hymnbook, which Bach harmonizes as four-part cantional movements ( SATB ). The 14 chorales were probably not sung by the congregation at the time, but they were part of the repertoire of the Passion songs and make the relevance of what happened then clear for today's listener. They do not belong directly to the ongoing action, but rather serve the entire community to represent the objective statements of salvation, while the arias are more geared towards the subjective experience of the individual listener. Her voice guidance is of great elegance, while sometimes bitter harmonies give the heavy words an expressive immediacy. The four-part cantional movements are orchestrated colla parte and show the passage and alternating notes typical of Bach in a particularly rich measure. The Arioso No. 25 (“O pain!”) Is combined with a chorale (“What is the cause”).

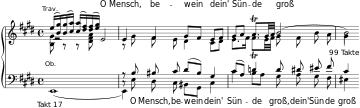

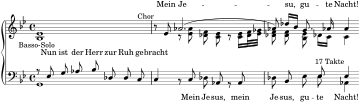

- Free choirs : In the St. Matthew Passion there are six madrigal free choir interludes for the allegorical figure of the "Daughter of Zion " (Choir I) and the community of believers (Choir II). In the double choir opening choir, these two groups enter into a dialogue with each other. No. 33 "Are lightning, are thunder" is tantamount to an outburst due to its long seventh chord chains, the excessive jumps, the shortened dominant seventh chords and the rapid pace. The first part ends with a large-scale chorale arrangement " O man, weep your sin great " (No. 35) in the motet style, in which the chorale melody is supported by the soprano in ripieno . The whole passion ends with the rondo- like lullaby “We sit down with tears” (No. 78) in a swaying 3/4 time. Two other free choir insertions can be found in arias No. 26 (“I want to watch over my Jesus”) and No. 70 (“See, Jesus has the hand”).

occupation

The piece was written for several vocal soloists, two orchestras and two four-part choirs, each with the vocal parts ( soprano , alto , tenor and bass ). Another soprano part is added in the opening choir. The instruments used on woodwinds are 2 transverse flutes - in no.25 instead 2 recorders - and 2 oboes - in no.25, 57/58, 69/70, 75 instead oboes da caccia and in no.18/19, 35, 36, 46 instead oboes d'amore - provided. Two violin parts , viola , viola da gamba (No. 40/41, 65/66, instead of one lute in the early version) are used on string instruments , and for the continuo group cello, violone and organ are used as basso continuo . The use of a bassoon for the continuo is controversial . Brass instruments are not considered appropriate for a Passion setting and are not used in Bach's Passions. Today the two ensembles are often set up side by side as a double choir and orchestra; the soloists can take over the roles in both ensembles.

It is unclear to what extent Bach planned a separate spatial arrangement in the first version in order to clarify the dialogic structures. Only in 1736 did Bach completely separate the two ensembles. A note from the Thomaskuester JC Rost indicates that the work was performed in 1736 with both organs . The small swallow's nest-like eastern gallery only offered space for the soprano ripieno during this performance , so that both choirs and the double orchestra played on the western main gallery of the St. Thomas Church. The fact that Bach replaced the second continuo organ with a harpsichord in 1740 is usually interpreted as a stopgap measure. That year the second organ was dismantled. It can be assumed that, with such a large cast, Bach used the choir singers, some of whom also had to play instruments, as well as students, city musicians, family members and music lovers. Today's performance and constellation practice can vary considerably from conductor to conductor.

In the fair copy of the 1736 version, the chorale melody appears in movements 1 and 35 in red ink and without text. The original parts also require a texted soprano in ripieno . For the cast of the Ripienochor, there is a modern performance tradition with boys' voices (as opposed to the female voices in the two choirs), which, however, has no relation to the original intentions of Bach, who in any case only used boy sopranos (or falsetting male voices for both soprano) in the church and Alt) began. In Bach's first version of the work from 1727, this part was taken over by the high woodwinds.

In addition to the solo parts for the recitatives and arias (soprano, alto, tenor, bass, divided into two choruses ), the St. Matthew Passion provides for the following role solo parts :

- Evangelist - tenor

- Jesus - bass

- Two maidservants (No. 45), Pilate's wife (No. 54) - sopranos

- Two witnesses (No. 39) - alto and tenor

- Simon Petrus (nos. 22, 46), Judas Iscariot (nos. 17, 49), high priest (nos. 39, 42), two priests (nos. 50), Pilate (nos. 52, 54, 56, 59, 76 ) - bass

Often six actual soloists (4 Accompagnato aria soloists - independent of the chorus -, another tenor - evangelist - and another bass - Jesus) are used and the remaining solos (the roles of the so-called soliloquents) are taken over by choir members. Occasionally the evangelist also takes on the tenor arias. In Bach's original voice material, however, a precise distinction is made between the choris (vocal and instrumental). The evangelist and Christ take over the tenor and bass of the first chorus . Bach's arias are also always assigned to one of the two ensembles ( chorus I or II). As early as 1920 Arnold Schering assumed that Bach usually had to make do with twelve singers. But only the early music movement followed this approach. Since Philippe Herreweghe's first recording in 1985 at the latest , such a reduced choir size of 12 to 20 singers has been the rule. The question of the cast was sparked above all by Andrew Parrott , who, following Rifkin, took the view that the cantatas and great vocal works in Bach's time were not made up of a choir in the modern sense, but as a rule soloists and only rarely by ripienists were reinforced. However, other representatives of historical performance practice such as Ton Koopman have contradicted this thesis and still use a small choir.

Text sources

The text is based on the 26th and 27th chapters of the Gospel of Matthew in the translation of Martin Luther as well as on the poems by Christian Friedrich Henrici (called Picander) in the madrigal pieces (arias, ariosi and free choirs), plus the passion chorales. No. 36 is based on a quote from ( Hld 6,1 LUT ). There is consensus in research that Bach influenced the design of the text. He himself probably selected chorales, as these are missing from Picander's collection of poems by Ernst-Schertzhaffte and Satyrische Gedichte (Vol. 2, Leipzig 1729). Picander, on the other hand, used passion sermons by Heinrich Müller for about half of his poems , whom Bach apparently valued very much and of which five volumes were represented in his library.

The chorales date from the 16th and 17th centuries. Eight of the total of 15 song verses are by Paul Gerhardt .

- "O lamb of God innocent", Nikolaus Decius (1531), verse 1 for no. 1 (cantus firmus)

- "Herzliebster Jesu", Johann Heermann (1630), verse 1 for no. 3, verse 3 for no. 25 (choir II in tenor recitative), verse 4 for no. 55

- "O world, see your life here", Paul Gerhardt (1647), verse 5 for no. 16, verse 3 for no. 44

- “ O head full of blood and wounds ”, Paul Gerhardt (1656), stanza 5 for no. 21, stanza 6 for no. 23, stanza 1 and 2 for no. 63, stanza 9 for no. 72

- " Whatever my God wants, that's always good ", Margrave Albrecht von Brandenburg (1547), verse 1 for no

- "O man, weep for your sin greatly", Sebald Heyden (1525), verse 1 for no. 35

- "I hoped in you, Lord", Adam Reusner (1533), verse 5 for no. 38

- “Get perky, my mind”, Johann Rist (1642), verse 6 for no. 48

- “ You command your ways ”, Paul Gerhardt 1653, verse 1 for no

Symbolism and interpretation

In the St. Matthew Passion , Bach often works with musical symbols that were anchored in the general consciousness of his contemporaries. In the recitatives, for example, the words of Jesus are always accompanied in the arioso by string chords that symbolize the divine. The acting people, however, are only supported by the figured bass . It is only when Jesus speaks the last words on the cross and laments his abandonment by God that the stringed instruments fall silent (No. 71).

Bach proves to be an interpreter of the Bible, the composition of which reflects a reflective theological interpretation and is designed as a “sounding sermon” (praedicatio sonora) . The depiction of the arias, which appears overloaded and rich in images, may be due to influences from Pietism . On the other hand, it shows piety phenomenological similarities with the outgoing Lutheran orthodoxy , which is not easy to distinguish from Pietism in terms of linguistic styling. Bach's extensive theological library comprised 52 volumes, which in addition to Bibles and the works of Luther contained extensive collections of songs and theological edification literature of Lutheran orthodoxy and pietism.

While choir I can symbolize the “daughters of Zion”, choir II stands for the believers, as Picander himself notes in his text edition. The two choirs have distinct roles in the six madrigal pieces. Choir I is close to the Passion Report and explains it, while Choir II focuses on the presence of the listener and asks questions. Particularly impressive is the opening choir, which bundles the entire message theologically and musically and expresses lament, mourning and confession of guilt, but also the call to look closely at God's love and patience. The throbbing bass, the key of E minor and the tombeau rhythm in 12/8 time emphasize the seriousness. The dense polyphony and the double-choir structure are increased by an additional soprano (“in ripieno”), who, through the crowning “O Lamb of God innocent”, calls to mind the healing message of the suffering of Christ, who through his vicarious death is the guilt of man has worn. The “daughters of Zion / Jerusalem” are known from the Song of Solomon and play a major role in Christian bride mysticism . They personify the encouragement and claim of the Passion event and appear at the beginning of the second part (No. 36) with a verbatim quote from ( Hld 6,1 LUT ). Taken as a whole, these are personified individual features that serve the purpose of dramatization, but which above all have a reflective function.

With recourse to old theological interpretations of the Passion story of Jesus, the Jews or individual persons are not identified as the cause of the suffering. “There are neither clearly good nor clearly bad protagonists; rather, all people are equally sinners. The disciples, Judas, Peter are only symbolic figures for general human behavior ”(quotation from Bartelmus). In the opening choir, the listener is not only asked to look at the suffering of Jesus, but also to become aware of his own sin: "See the bridegroom [...] see our guilt". At the request of Jesus to be vigilant, the conscience of the listener is addressed in Accompagnato No. 25: “Oh! my sins have struck you; I, oh Lord Jesus, are responsible for what you endured ”. The denial and repentance of Peter comments on aria 47: "Have mercy, my God, for the sake of my tenacity". The statement of the death of Jesus (“and passed”) takes the chorale no. 72 (“If I should part, then do not part from myself”) as an opportunity to ask God for his help for the hour of one's own death. As in the St. John Passion , the contemplative updating of the historical report does not take place by means of a mystical merging of the time horizons or an emotional shock to the listener, but through devout contemplation and concern of the biblical word.

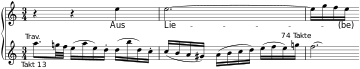

The deepest explanation of the suffering is offered by the contemplative aria no. 58 “For love”, which takes the center stage in the symmetrical conception of the early version. The intimate connection between the Savior and the pious ego of the hearer is justified in the voluntary sacrificial death of Jesus out of love. Through the delicate instrumentation with flute and two oboes da caccia that not without continuo ( "Bassettchen") and the Key A minor signs has, the pure, angelic character of the aria is underlined and symbolizes the heavenly love and innocence of Jesus. The contrast to the following choir “Let him crucify” (No. 59), which is one whole tone higher than the otherwise identical chorus No. 54, cannot be greater. How the irrepressible fury of the masses increases is shown by the increase of crosses as an accidental up to C sharp major, which has seven crosses. In strict polyphony of a fugue exposure, the individual voices, which rise one after the other from bass to soprano, demand “formulated according to law, with merciless severity the maximum penalty” (quote from Platen). The affect is underlined by the cross motif in the melody, the syncope formation and the reduced fourth and fifth leaps (the tritone stands for the diabolus in musica ).

Bach relates music and text in the sense of musical rhetoric. Based on the doctrine of affect generally widespread in the Baroque , the basic character of a piece is determined by the musical form, tempo, dynamics , key characteristics, rhythmic design and scoring, while the meaning of individual words is expressed musically through rhetorical stylistic figures. Thus, in aria no. 10, the saltus duriusculus and the passage duriusculus are inserted in response to the words “Buß und Reu” (bars 13 f., 15 f., 30 and 31) to create mental contrition through the surprisingly dissonant, excessive leaps in intervals to be heard. With the words "expresses and came on earth" in No. 35, Bach lets the melody descend over the pitch of a decimal in seconds, while the thoroughbass descends 15 pitches, not only about the descent of Christ from the heavenly world, but also his humiliation and to illustrate humiliation. The circling melody movement of the Circulatio on the words “captured” in No. 33 illustrates the immobility of Jesus during his capture, underlined by the chains of tied note sequences. The contrasting rhythmic character in the aria “Patience” (No. 41) characterizes the two contrasting figures of the hypotyposis . Bach clarifies the word “patience” with a calm eighth note accompaniment as well as a tied-up melody voice that has been delayed by suspensions; the accompaniment of the text "false tongues", however, he provides with impetuous punctuation.

The unequal, well-tempered mood in the Baroque era led to differently pure sounding keys, from which a key characteristic was developed that assigned the different keys to the different affects. According to Bach's contemporaries Johann Mattheson in E minor is deeply contemplative / sad and sad [...] but so / that one hopes to be comforted there (cf. the opening choir “Come, you daughters, help me complain” and no. 33 “So my Jesus is now trapped "), G major is so easy to serieusen as cheerful things even sent (cf. No. 19" I want to give you my heart "), B minor is bizarre, uncomfortable and melancholy (cf. No. 19) 30 “Oh! Now my Jesus is gone!” And No. 47 “Have mercy”), C minor is an extremely lovely dabey, also sad Tohn (cf. the final chorus “We sit down with tears”).

There are numerous studies that believe to recognize particularly pronounced number- mystical elements in the St. Matthew Passion , but at least some of them are likely to be based on coincidences. In the earthquake scene (no.73), the 190 eruptive thirty-second notes in the continuo can be divided into three groups of 18, 68 and 104 notes, which corresponds to the numbers of the three psalms in which earthquakes are mentioned: ( Ps 18 : 8 LUT ), ( Ps 68,9 LUT ) and ( Ps 104,32 LUT ). The total of 365 words of Jesus are interpreted as an allusion to the conclusion of the Gospel of Matthew, where Jesus promises his disciples to be with them "every day" ( Mt 28:20 LUT ). In the 14 chorales and 28 (2 × 14) free poems by Picander one discovers an allusion to the name Bach, whose letter value adds up to 14 (A = 1, B = 2, C = 3, H = 8). Bach also wanted to place himself under the cross through the 14 bass notes in the captain's confession (No. 73 “Truly, this was God's Son”) and wanted to join in.

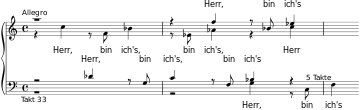

Another example is choir No. 15: In the accompanying recitative, Jesus says: "Truly, I say to you: One of you will betray me." In the following excited choir, the disciples answer eleven times in a wild confusion with the question: “Lord, is it me, is it me?” The fact that this question is repeated eleven times - and not twelve times, as would correspond to the number of apostles present - can be understood to mean that Judas, fully aware of his guilt, initially does not dare to ask his master that question. Only in the following recitative, Judas as the twelfth disciple asks: "Is it me, Rabbi?"

Work overview

The numbers in the article follow the Bach works directory . For comparison, the corresponding numbers from the New Bach Edition are given in the second column. In the last column the incipit indicates the beginning of the song text.

| Color legend | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| recitative | Turba | Accompagnato | aria | Chorale | Free choir |

The different musical forms are highlighted according to the color legend. In the case of combination forms (for example aria + chorale or free choir) the second corresponding color appears in the same line.

| First part | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BWV | NBA | shape | key | Tact | Start of text | Instrumentation | Text source | Incipit | |

| 1 | 1 | Choir I & II (SATBSATB) | + Chorale melody (soprano) | E minor | 12/8 |

Come, you daughters, help me complain + O Lamb of God innocent |

2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Picander, Nicolaus Decius, 1531 |

|

| 2 | 2 | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Jesus / Bass) | G major → B minor | Since Jesus had finished this speech | Continuo | Mt 26 : 1-2 LUT |

|

||

| 3 | 3 | Chorale (SATB) | B minor | C (4/4) | Dearest of Jesus | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Johann Heermann, 1630 |

|

|

| 4th | 4a | Recitative (evangelist / tenor) | A major → C major | Then the chief priests met | Continuo | Mt 26,3-4 LUT |

|

||

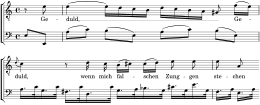

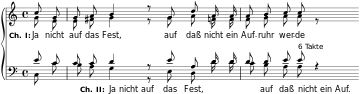

| 5 | 4b | Choir I & II (SATBSATB) | C major | C (4/4) | Yes not for the party | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Mt 26,5 LUT |

|

|

| 6th | 4c | Recitative (evangelist / tenor) | C major → E major | Now that Jesus was in Bethany | Continuo | Mt 26,6-8a LUT |

|

||

| 7th | 4d | Choir I (SATB) | A minor → D minor | C (4/4) | What is this rubbish used for? | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Mt 26,8b-9 LUT |

|

|

| 8th | 4e | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Jesus / Bass) | B major → E minor | Since Jesus noticed | Strings, continuo | Mt 26 : 10-13 LUT |

|

||

| 9 | 5 | Accompagnato recitative (alto) | B minor → F sharp minor | C (4/4) | You dear savior | 2 transverse flutes, continuo | Picander |

|

|

| 10 | 6th | Aria (alto) | F sharp minor | 3/8 | Repentance and repentance | 2 transverse flutes, continuo | Picander |

|

|

| 11 | 7th | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Judas / Bass) | E major → D major | Then one of the twelve went | Continuo | Mt 26 : 14-16 LUT |

|

||

| 12 | 8th | Aria (soprano) | B minor | C (4/4) | Just bleed, dear heart! | 2 transverse flutes, strings, continuo | Picander |

|

|

| 13 | 9a | Recitative (evangelist / tenor) | G major → D major | But on the first day of the sweet bread | Continuo | Mt 26,17a LUT |

|

||

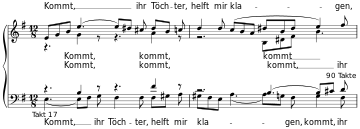

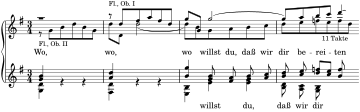

| 14th | 9b | Choir I (SATB) | G major | 3/4 | Where do you want us to prepare you | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Mt 26,17b LUT |

|

|

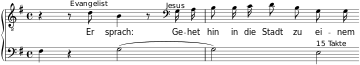

| 15th | 9c | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Jesus / Bass) | G major → C major | He said: Go into the city | Strings, continuo | Mt 26 : 18-21 LUT |

|

||

| 9d | Recitative (evangelist / tenor) | B minor → F minor | And they got very sad | Continuo | Mt 26,22a LUT |

|

|||

| 9e | Choir I (SATB) | F minor → C major | C (4/4) | Lord is it me? | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Mt 26,22b LUT |

|

||

| 16 | 10 | Chorale (SATB) | A flat major | C (4/4) | It's me, I should pay | 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Paul Gerhardt, 1647 |

|

|

| 17th | 11 | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Jesus / Bass, Judas / Bass) | F minor → G major | C (4/4) -6/4 | He answered and spoke | Strings, continuo | Mt 26 : 23-29 LUT |

|

|

| 18th | 12 | Accompagnato recitative (soprano) | E minor → C major | C (4/4) | Although my heart is swimming in tears | 2 oboes d'amore, continuo | Picander |

|

|

| 19th | 13 | Aria (soprano) | G major | 6/8 | I want to give you my heart | 2 oboes d'amore, continuo | Picander |

|

|

| 20th | 14th | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Jesus / Bass) | B minor → E major | And since they had spoken the hymn of praise | Strings, continuo | Mt 26 : 30-32 LUT |

|

||

| 21st | 15th | Chorale (SATB) | E major | C (4/4) | Know me, my keeper | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Paul Gerhardt, 1656 |

|

|

| 22nd | 16 | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Petrus / Bass, Jesus / Bass) | A major → G minor | But Peter answered | Strings, continuo | Mt 26 : 33-35 LUT |

|

||

| 23 | 17th | Chorale (SATB) | E flat major | C (4/4) | I want to stand here with you | 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Paul Gerhardt, 1656 |

|

|

| 24 | 18th | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Jesus / Bass) | F major → A flat major | So Jesus came with them to a court | Strings, continuo | Mt 26 : 36-38 LUT |

|

||

| 25th | 19th | Accompagnato recitative (tenor) | + Chorale (SATB) | F minor → G major | C (4/4) | Here the tormented heart trembles | 2 recorders, 2 oboes da caccia, strings, continuo | Johann Heermann, 1630 |

|

| 26th | 20th | Aria (tenor) | + Choir II | C minor | C (4/4) | I want to watch over my Jesus | 2 transverse flutes, oboe, strings, continuo | Picander |

|

| 27 | 21st | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Jesus / Bass) | B major → G minor | And went a little | Strings, continuo | Mt 26,39 LUT |

|

||

| 28 | 22nd | Accompagnato recitative (bass) | D minor → B flat major | C (4/4) | The Savior falls before his Father | Strings, continuo | Picander |

|

|

| 29 | 23 | Aria (bass) | G minor | 3/8 | I would like to make myself comfortable | 2 violins, continuo | Picander |

|

|

| 30th | 24 | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Jesus / Bass) | F major → B minor | And he came to his disciples | Strings, continuo | Mt 26,40-42 LUT |

|

||

| 31 | 25th | Chorale (SATB) | B minor | C (4/4) | Whatever my God wants, that's always the case | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Albrecht of Prussia, around 1554 |

|

|

| 32 | 26th | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Jesus / Bass, Judas / Bass) | D major → G major | And he came and found her sleeping | Strings, continuo | Mt 26 : 43-50 LUT |

|

||

| 33 | 27a | Aria (soprano, alto) | + Choir II (SATB) | E minor | C (4/4) | So my Jesus is now trapped | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Picander |

|

| 27b | Choir I & II (SATBSATB) | E minor | 3/8 | Is it lightning, has thunder disappeared in clouds? | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Picander |

|

||

| 34 | 28 | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Jesus / Bass) | F sharp major → c sharp minor | And see, one of them | Strings, continuo | Mt 26 : 51-56 LUT |

|

||

| 35 | 29 | Chorale (SATB) | E major | C (4/4) | O man, weep greatly for your sin | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes d'amore, strings, continuo | Sebald Heyden, around 1530 |

|

|

| Second part | |||||||||

| BWV | NBA | shape | key | Tact | Start of text | Instrumentation | Text source | Incipit | |

| 36 | 30th | Aria (alto) | + Choir II (SATB) | B minor | 3/8 | Oh! now my Jesus is gone! | Transverse flute, oboe d'amore, strings, continuo | Picander |

|

| 37 | 31 | Recitative (evangelist / tenor) | B major → D minor | But who had grasped Jesus | Continuo | Mt 26,57-60a LUT |

|

||

| 38 | 32 | Chorale (SATB) | B flat major | C (4/4) | The world judged me deceptively | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Adam Reusner, 1533 |

|

|

| 39 | 33 | Recitative (evangelist / tenor, 2 witnesses / alto and tenor, high priest / bass) | G minor | And although many false witnesses came forward | Continuo | Mt 26.60b-63a LUT |

|

||

| 40 | 34 | Accompagnato recitative (tenor) | A major → A minor | C (4/4) | My Jesus is silent | 2 oboes, viola da gamba, continuo | Picander |

|

|

| 41 | 35 | Aria (tenor) | A minor | C (4/4) | Patience! When the wrong tongues prick me | Continuo (with viola da gamba instead of violone) | Picander |

|

|

| 42 | 36a | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, High Priest / Bass, Jesus / Bass) | E minor | And the high priest answered | Strings, continuo | Mt 26,63b-66a LUT |

|

||

| 36b | Choir I & II (SATBSATB) | G major | He is guilty of death! | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Mt 26,66b LUT |

|

|||

| 43 | 36c | Recitative (evangelist / tenor) | C major → D minor | Then they spit out | Continuo | Mt 26,67 LUT |

|

||

| 36d | Choir I & II (SATBSATB) | D minor → F major | Prophesy us, Christ | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Mt 26,68 LUT |

|

|||

| 44 | 37 | Chorale (SATB) | F major | C (4/4) | Who hit you like that | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Paul Gerhardt, 1647 |

|

|

| 45 | 38a | Recitative (evangelist / tenor, Petrus / bass, 2 maids / soprano) | A major → D major | But Peter was sitting outside | Continuo | Mt 26 : 69-73a LUT |

|

||

| 38b | Choir II (SATB) | D major → A major | Verily, you are one too | 2 transverse flutes, oboe, oboe d'amore, strings, continuo | Mt 26,73b LUT |

|

|||

| 46 | 38c | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Petrus / Bass) | C sharp major → F sharp minor | Then he began to curse himself | Continuo | Mt 26 : 74-75 LUT |

|

||

| 47 | 39 | Aria (alto) | B minor | 12/8 | Have mercy | Violin solo I, strings, continuo | Picander |

|

|

| 48 | 40 | Chorale (SATB) | F sharp minor → A major | C (4/4) | I left you in a moment | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Johann Rist, 1642 |

|

|

| 49 | 41a | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Judas / Bass) | F sharp minor → B major | But in the morning all the high priests stopped | Continuo | Mt 27 : 1-4a LUT |

|

||

| 41b | Choir I & II (SATBSATB) | B major → E minor | What is that to us? | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Mt 27,4b LUT |

|

|||

| 50 | 41c | Recitative (evangelist / tenor, 2 high priests / bass) | A minor → B minor | And he threw the pieces of silver into the temple | Continuo | Mt 27,5-6 LUT |

|

||

| 51 | 42 | Aria (bass) | G major | C (4/4) | Give me back my Jesus! | Violin solo II, strings, continuo | Picander |

|

|

| 52 | 43 | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Jesus / Bass, Pilate / Bass) | E minor → D major | But they held advice | Strings, continuo | Mt 27,7-14 LUT |

|

||

| 53 | 44 | Chorale (SATB) | D major | C (4/4) | You command your ways | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Paul Gerhardt, 1653 |

|

|

| 54 | 45a | Recitative (evangelist / tenor, Pilate / bass, Pilate's wife / soprano) | Choir I & II (SATBSATB) | E major → A minor | But the governor was used to the festival | Continuo | Mt 27 : 15-22a LUT |

|

|

| 45b | Choir I & II (SATBSATB) | A minor → B major | Let him be crucified! | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Mt 27,22b LUT |

|

|||

| 55 | 46 | Chorale (SATB) | B minor | C (4/4) | How wonderful is this punishment! | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Johann Heermann, 1630 |

|

|

| 56 | 47 | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Pilate / Bass) | E minor | The governor said | Continuo | Mt 27,23a LUT |

|

||

| 57 | 48 | Accompagnato recitative (soprano) | E minor → C major | C (4/4) | He did us all good | 2 oboes da caccia, continuo | Picander |

|

|

| 58 | 49 | Aria (soprano) | A minor | 3/4 | My Savior wants to die for love | Transverse flute, 2 oboes da caccia, no continuo | Picander |

|

|

| 59 | 50a | Recitative (evangelist / tenor) | E minor | But they screamed even more | Continuo | Mt 27,23b LUT |

|

||

| 50b | Choir I & II (SATBSATB) | B minor → C sharp major | Let him be crucified! | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Mt 27,23c LUT |

|

|||

| 50c | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Pilate / Bass) | C sharp major → B minor | But then Pilate saw | Continuo | Mt 27 : 24-25a LUT |

|

|||

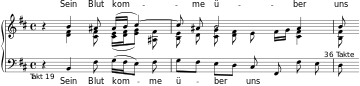

| 50d | Choir I & II (SATBSATB) | B minor → D major | His blood come on us | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Mt 27,25b LUT |

|

|||

| 50e | Recitative (evangelist / tenor) | D major → E minor | So he released Barrabam to them | Continuo | Mt 27,26 LUT |

|

|||

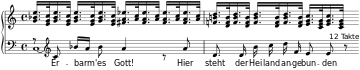

| 60 | 51 | Accompagnato recitative (alto) | F major → G minor | C (4/4) | Have mercy on God! | Strings, continuo | Picander |

|

|

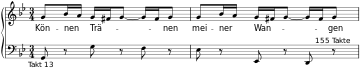

| 61 | 52 | Aria (alto) | G minor | 3/4 | May my cheeks tear | 2 violins, continuo | Picander |

|

|

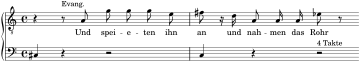

| 62 | 53a | Recitative (evangelist / tenor) | F major → D minor | Then the soldiers took | Continuo | Mt 27 : 27-29a LUT |

|

||

| 53b | Choir I & II (SATBSATB) | D minor → A major | Greetings, King of the Jews! | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Mt 27,29b LUT |

|

|||

| 53c | Recitative (evangelist / tenor) | D minor | And spit at him | Continuo | Mt 27.30 LUT |

|

|||

| 63 | 54 | Chorale (SATB) | D minor → F major | C (4/4) | Oh head, full of blood and wounds | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Paul Gerhardt, 1656 |

|

|

| 64 | 55 | Recitative (evangelist / tenor) | A minor | And since they mocked him | Continuo | Mt 27 : 31-32 LUT |

|

||

| 65 | 56 | Accompagnato recitative (bass) | F major → D minor | C (4/4) | Yes, of course, want in us | 2 transverse flutes, viola da gamba, continuo | Picander |

|

|

| 66 | 57 | Aria (bass) | D minor | C (4/4) | Come on, sweet cross | Viola da gamba, continuo | Picander |

|

|

| 67 | 58a | Recitative (evangelist / tenor) | C major → F sharp major | And when they came to the place | Continuo | Mt 27 : 33-39 LUT |

|

||

| 58b | Choir I & II (SATBSATB) | F sharp major → B minor | Who break the temple of God | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Mt 27.40 LUT |

|

|||

| 58c | Recitative (evangelist / tenor) | F sharp major → E minor | Likewise also the high priests | Continuo | Mt 27,41 LUT |

|

|||

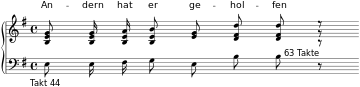

| 58d | Choir I & II (SATBSATB) | E minor | He has helped others | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Mt 27 : 42-43 LUT |

|

|||

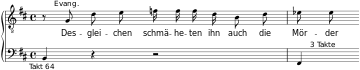

| 68 | 58e | Recitative (evangelist / tenor) | G major → C minor | Likewise reviled him | Continuo | Mt 27,44 LUT |

|

||

| 69 | 59 | Accompagnato recitative (alto) | A flat major | C (4/4) | Oh Golgotha | 2 oboes da caccia, continuo | Picander |

|

|

| 70 | 60 | Aria (alto) | + Choir II (SATB) | E flat major | C (4/4) | See, Jesus has the hand | 2 oboes da caccia, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Picander |

|

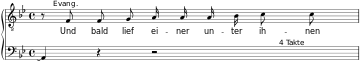

| 71 | 61a | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Jesus / Bass) | E flat major → C minor | And from the sixth hour | Continuo, no strings | Mt 27 : 45-47a LUT |

|

||

| 61b | Choir I (SATB) | C minor → F major | He calls Elias! | 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Mt 27,47b LUT |

|

|||

| 61c | Recitative (evangelist / tenor) | F major → G minor | And soon one of them was running | Continuo | Mt 27 : 48-49a LUT |

|

|||

| 61d | Choir II (SATB) | G minor → D minor | Stop! Let me see | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Mt 27,49b LUT |

|

|||

| 61e | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Jesus / Bass) | D minor → A minor | But Jesus cried out loudly again | Continuo | Mt 27.50 LUT |

|

|||

| 72 | 62 | Chorale (SATB) | A minor | C (4/4) | If I ever have to divorce | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Paul Gerhardt, 1656 |

|

|

| 73 | 63a | Recitative (evangelist / tenor) | C major → A flat major | And lo and behold, the curtain in the temple was torn | Continuo | Mt 27 : 51-54a LUT |

|

||

| 63b | Choir I & II (SATBSATB) ( unison ) | A flat major | Verily, this was the Son of God | 2 transverse flutes, oboe, strings, continuo | Mt 27,54b LUT |

|

|||

| 63c | Recitative (evangelist / tenor) | E flat major → B flat major | And there were many women there | Continuo | Mt 27 : 55-58 LUT |

|

|||

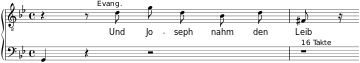

| 74 | 64 | Accompagnato recitative (bass) | G minor | C (4/4) | In the evening when it was cool | Strings, continuo | Picander |

|

|

| 75 | 65 | Aria (bass) | B flat major | 12/8 | Make yourself, my heart, pure | 2 oboes da caccia, strings, continuo | Picander |

|

|

| 76 | 66a | Recitative (evangelist / tenor) | G minor → E flat major | And Joseph took the body | Continuo | Mt 27 : 59-62 LUT |

|

||

| 66b | Choir I & II (SATBSATB) | E flat major → D major | Lord we thought | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Mt 27 : 63-64 LUT |

|

|||

| 66c | Recitative (Evangelist / Tenor, Pilate / Bass) | G minor → E flat major | Pilate spoke to them | Continuo | Mt 27 : 65-66 LUT |

|

|||

| 77 | 67 | Accompagnato recitative (soprano, alto, tenor, bass) | + Choir II (SATB) | E flat major → C minor | C (4/4) | Now the Lord is rested | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Picander |

|

| 78 | 68 | Choir I & II (SATBSATB) | C minor | 3/4 | We sit down with tears | 2 transverse flutes, 2 oboes, strings, continuo | Picander |

|

|

literature

General

- Malcolm Boyd : Johann Sebastian Bach. Life and work . dtv, Bärenreiter, Munich, Kassel 1992, ISBN 3-423-30323-9 .

- Werner Breig : Bach, Johann Sebastian . In: Ludwig Finscher (Hrsg.): The music in past and present. Person part . 2nd Edition. tape 1 . Bärenreiter / Metzler, Kassel / Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-7618-1111-X , p. 1397-1535 .

- Martin Geck : Bach. Life and work . Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 2000, ISBN 3-498-02483-3 .

- Michael Heinemann (Ed.): The Bach Lexicon . 2nd Edition. Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2000, ISBN 3-89007-456-1 (Bach Handbook; 6).

- Konrad Küster (Ed.): Bach Handbook . Bärenreiter / Metzler, Kassel / Stuttgart 1999, ISBN 3-7618-2000-3 .

- Werner Neumann, Hans-Joachim Schulze (Ed.): Foreign-written and printed documents on the life story of Johann Sebastian Bach 1685–1750 . Bärenreiter, German publishing house for music, Kassel / Leipzig a. a. 1969 (Bach documents 2).

- Werner Neumann, Hans-Joachim Schulze (ed.): Documents from the hand of Johann Sebastian Bach . Bärenreiter, Kassel u. a. 1963 (Bach documents 1).

- Arnold Werner-Jensen: Reclam's music guide Johann Sebastian Bach . tape 2 : vocal music . Reclam, Stuttgart 1993, ISBN 3-15-010386-X .

- Christoph Wolff : Johann Sebastian Bach. The Learned Musician . WW Norton, New York / London 2000, ISBN 0-393-04825-X .

plant

- Rüdiger Bartelmus : The St. Matthew Passion by J. S. Bach as a symbol. Thoughts on an inexhaustible musical-theological work . In: Theological Journal . tape 1 , 1991, p. 18-65 ( books.google.de ).

- Hans Blumenberg: St. Matthew Passion (= Library Suhrkamp . Vol. 998). Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 1988, ISBN 3-518-01998-8 .

- Werner Braun: The Protestant Passion . In: Ludwig Finscher (Hrsg.): The music in past and present . Material part . 2nd Edition. tape 7 . Bärenreiter, Kassel 1997, ISBN 3-7618-1101-2 , p. 1469-1487 .

- Hans Darmstadt: Johann Sebastian Bach. St. Matthew Passion. BWV 244. Analyzes and remarks on composition technique with practical performance and theological notes. Klangfarben-Musikverlag, Dortmund 2016, ISBN 978-3-932676-18-5 .

- Martin Geck: The rediscovery of the St. Matthew Passion in the 19th century. The contemporary documents and their interpretation of the history of ideas . Bosse, Regensburg 1967.

- Günter Jena : “It touches my soul.” The St. Matthew Passion by Johann Sebastian Bach . Herder, Freiburg 1999, ISBN 3-451-04794-2 .

- Daniel R. Melamed: Choral and choral movements . In: Christoph Wolff (Ed.): The world of Bach cantatas . tape 1 Johann Sebastian Bach's church cantatas: from Arnstadt to the days of Köthen . JB Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 1996, ISBN 3-7618-1278-7 , p. 169–184 (2006 special edition, ISBN 3-476-02127-0 ).

- Johann Theodor Mosewius : JS Bach's St. Matthew Passion presented musically and aesthetically. Berlin 1852; Digitized

- Andrew Parrott : Bach's choir: to the new understanding . Metzler / Bärenreiter, Stuttgart / Kassel 2003, ISBN 3-7618-2023-2 , p. 66-107 .

- Emil Platen : Johann Sebastian Bach. The St. Matthew Passion. Origin, description of the work, reception . 2nd Edition. Bärenreiter, dtv, Kassel / Munich a. a. 1997, ISBN 3-7618-4545-6 .

- Johann Sebastian Bach. St. Matthew Passion, BWV 244. Lectures of the JS Bach Summer Academy 1985 . In: Ulrich Prinz (Ed.): Johann Sebastian Bach. St. Matthew Passion BWV 244 . Breitkopf & Härtel, Stuttgart / Kassel 1990, ISBN 3-7618-0977-8 .

- Johann Michael Schmidt : The St. Matthew Passion by Johann Sebastian Bach. On the history of their religious and political perception and impact . Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Leipzig 2018, ISBN 978-3-374-05448-0 .

- Arnold Schmitz: The oratory art of J. S. Bach . In: Walter Blankenburg (Ed.): Johann Sebastian Bach (= Paths of Research . No. 170 ). Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1970, p. 61-84 .

- Christoph Wolff (Ed.): The world of Bach cantatas. Volume III. Johann Sebastian Bach's Leipzig church cantatas . Metzler, Bärenreiter, Stuttgart, Kassel a. a. 1998, ISBN 3-7618-1277-9 .

Theological interpretation

- Elke Axmacher: “My Heyland wants to die for love”. Investigations into the change in the understanding of the Passion in the early 18th century . Hänssler, Neuhausen-Stuttgart 1984, ISBN 3-7751-0883-1 (contributions to theological Bach research 1).

- Johan Bouman : Music for the Glory of God. Music as a gift from God and proclamation of the Gospel with Johann Sebastian Bach . 2nd Edition. Brunnen, Giessen 2000, ISBN 3-7655-1201-X .

- Walter Hilbrands : Johannes Sebastian Bach as interpreter of the Bible in his St. John Passion . In: Walter Hilbrands (Ed.): Love language - understand God's word. Contributions to biblical exegesis . Brunnen, Giessen 2011, ISBN 978-3-7655-9247-8 , p. 271-285 .

- Robin A. Leaver: Bach's Theological Library . Hänssler, Neuhausen-Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-7751-0841-6 .

- Martin Petzold: Between Orthodoxy, Pietism and Enlightenment - Considerations on the theological-historical context of Johann Sebastian Bach . In: Reinhard Szeskus (ed.): Bach and the Enlightenment . Breitkopf & Härtel, Leipzig 1982, p. 66-107 .

- Lothar and Renate Steiger: The theological meaning of the double choir in Johann Sebastian Bach's "St. Matthew Passion" . In: Wolfgang Rehm (Ed.): Bachiana et alia musicologica. Festschrift Alfred Dürr . Bärenreiter, Kassel 1983, ISBN 3-7618-0683-3 , p. 275-286 .

Recordings / sound carriers (selection)

The list is a selection of influential recordings made on phonograms, specifically considering those currently commercially available.

On historical instruments

- Nikolaus Harnoncourt (Teldec, 1970): Concentus Musicus Wien , boy soloists of the Regensburger Domspatzen , Choir of King's College (Cambridge) ; Soloists: Kurt Equiluz , Karl Ridderbusch , boy soprano of the Vienna Boys' Choir , Paul Esswood , Tom Sutcliffe, James Bowman , Nigel Rogers , Max van Egmond , Michael Schopper .

- Philippe Herreweghe (Harmonia Mundi, 1985): La Chapelle Royale , Collegium Vocale Gent ; Soloists: Howard Crook, Ulrik Cold, Barbara Schlick , René Jacobs , Hans-Peter Blochwitz , Peter Kooij .

- John Eliot Gardiner (archive production, 1989): English Baroque Soloists , Monteverdi Choir ; Soloists: Anthony Rolfe Johnson , Andreas Schmidt , Barbara Bonney , Anne Sofie von Otter , Michael Chance , Howard Crook, Olaf Bär .

- Gustav Leonhardt (German Harmonia Mundi, 1989): La Petite Bande and male choir, Tölzer boys' choir ; Soloists: Christoph Prégardien , Max van Egmond , boy soloists of the Tölzer Knabenchor, René Jacobs , David Cordier , Markus Schäfer , John Elwes , Klaus Mertens , Peter Lika .

- Christoph Spering (Tete-a-Tete, 1992): Chorus Musicus Cologne , Das Neue Orchester; Soloists: Wilfried Jochens , Peter Lika, Angela Kazimierczuk, Alison Browner , Markus Schäfer, Franz-Josef Selig .

- Ton Koopman (Erato, 1993): Nederlandse Bachvereniging , Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra & Choir; Soloists: Guy de Mey, Peter Kooij, Barbara Schlick , Kai Wessel , Christoph Prégardien, Klaus Mertens.

- Frans Brüggen (Philips, 1996): Boys' Choir of St Bavo's Cathedral, Haarlem & Nederlands Kamerkoor, 18th century orchestra ; Soloists: Nico van der Meel, Kristinn Sigmundsson, María Cristina Kiehr , Mona Julsrud, Claudia Schubert, Wilke te Brummelstroete, Ian Bostridge , Toby Spence, Peter Kooy, Harry van der Kamp .

- Philippe Herreweghe (Harmonia Mundi, 1998): Collegium Vocale Gent; Soloists: Ian Bostridge, Franz-Josef Selig, Sibylla Rubens, Andreas Scholl , Werner Güra , Dietrich Henschel .

- Masaaki Suzuki (BIS Records, 1999): Bach Collegium Japan ; Soloists: Gerd Türk , Peter Kooy, Nancy Argenta , Robin Blaze, Makoto Sakurada, Chiyuki Urano.

- René Jacobs (HMF, 2012): RIAS Chamber Choir , Staats- und Domchor Berlin , Akademie für Alte Musik Berlin ; Soloists: Sunhae Im, Bernarda Fink , Johannes Weisser, Topi Lehtipuu, Konstantin Wolff, Werner Güra .

- Rudolf Lutz (JS Bach Foundation, 2014): Choir and Orchestra of the JS Bach Foundation ; Soloists: Joanne Lunn , Margot Oitzinger , Charles Daniels , Peter Harvey , Wolf Matthias Friedrich .

- Jos van Veldhoven (allofbach, 2014): Nederlandse Bachvereniging ; Soloists: Benjamin Hulett, Andreas Wolf, Griet De Geyter, Tim Mead , Thomas Hobbs.

- Frieder Bernius (Carus, 2015): Chamber Choir Stuttgart , Barockorchester Stuttgart ; Soloists: Hannah Morrison, Sophie Harmsen, Tilman Lichdi, Peter Harvey.

With a solo cast

- Paul McCreesh (archive production, 2003): Gabrieli Consort and Players; Choir 1: Deborah York, Magdalena Kožená , Mark Padmore , Peter Harvey , Choir 2: Julia Gooding, Susan Bickley, James Gilchrist , Stephan Loges.

- Sigiswald Kuijken (Challenge Classics, 2008): La Petite Bande ; Christoph Genz , Jan van der Crabben, Gerlinde Sämann , Marie Kuijken, Petra Noskaiová, Patrizia Hardt, Bernhard Hunziker, Marcus Niedermeyr.

On modern instruments

- Willem Mengelberg (Philips, 1939): Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam, Amsterdam Toonkunstkoor & “Zanglust” Jongenskoor; Soloists: Karl Erb , Willem Ravelli, Jo Vincent, Ilona Durigo , Louis van Tulder, Hermann Schey.

- Otto Klemperer (EMI, 1962): Philharmonia Orchestra and Choir; Soloists: Peter Pears , Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau , Elisabeth Schwarzkopf , Christa Ludwig , Nicolai Gedda , Walter Berry , Heather Harper , Geraint Evans .

- Leonard Bernstein (Columbia Masterworks, 1962): New York Philharmonic , Collegiate Chorale; Soloists: Adele Addison , William Wildermann, David Lloyd, Charles Bressler, Donaldson Bell, Betty Allen .

- Karl Richter (archive production, 1969): Munich Bach Choir , Munich Boys Choir , Munich Bach Orchestra ; Soloists: Ernst Haefliger , Kieth Engen , Ursula Buckel , Marga Höffgen , Peter van der Bilt

- Herbert von Karajan (Deutsche Grammophon, 1972): Berliner Philharmoniker , Wiener Singverein , choir of the Deutsche Oper Berlin , boys' voices of the State and Cathedral Choir Berlin ; Soloists: Peter Schreier , Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Gundula Janowitz , Christa Ludwig , Horst Laubenthal , Walter Berry , Anton Diakov .

- Rudolf Mauersberger ( Eterna , 1975): Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Dresdner Kreuzchor , Thomanerchor Leipzig, soloists: Peter Schreier, Theo Adam , Adele Stolte , Annelies Burmeister , Hans-Joachim Rotzsch , Günther Leib , Siegfried Vogel .

- Georg Solti (Decca Records, 1988): Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus; Soloists: Hans-Peter Blochwitz , Olaf Bär , Kiri Te Kanawa , Anne Sofie von Otter , Anthony Rolfe Johnson , Tom Krause .

- Helmuth Rilling (SCM Hänssler, 1999): Gächinger Kantorei Stuttgart , Bach-Collegium Stuttgart ; Soloists: Christiane Oelze , Ingeborg Danz , Michael Schade , Matthias Goerne , Thomas Quasthoff .

- Enoch zu Guttenberg (Farao Classics, 2003): Orchestra of the Sound Management, Chorgemeinschaft Neubänen, Tölzer Knabenchor ; Soloists: Marcus Ullmann , Klaus Mertens, Anna Korondi, Anke Vondung, Werner Güra , Hans Christoph Begemann .

- Simon Rattle (DVD, 2010, and video - live stream in the so-called Digital Concert Hall ): Ritualization: Peter Sellars ; Ensembles: Berliner Philharmoniker , Rundfunkchor Berlin , boys' voices of the State and Cathedral Choir Berlin ; Soloists: Camilla Tilling , Magdalena Kožená , Topi Lehtipuu (arias), Mark Padmore (evangelist), Thomas Quasthoff (arias), Christian Gerhaher (Christ).

Web links

Digital copies

- Original score, 1736 (Berlin State Library)

- Copy of the score of the early version by JC Farlaus, Part 1 (Berlin State Library)

- Copy of the score of the early version by JC Farlaus, Part 2 (Berlin State Library)

- Matthew Passion (early version) BWV 244.1 and Matthew Passion BWV 244.2 at Bach-Digital , Bach-Archiv Leipzig

Sheet music and audio files

- St. Matthew Passion (Bach) : Sheet music and audio files in the International Music Score Library Project (including autograph)

Further information

- Text and structure of the St. Matthew Passion

- Source description of the original score , source database RISM

- Publications on the St. Matthew Passion in the catalog of the German National Library

- St. Matthew Passion with Bach Cantatas (English)

- Search for St. Matthew Passion in the German Digital Library

- Search for St. Matthew Passion in the SPK digital portal of the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation

Discography

- Overview of the existing recordings (English)

Individual evidence

- ^ Platen: Johann Sebastian Bach. The St. Matthew Passion. 1997, p. 13.

- ↑ For the history of passion music see: Braun: Die Protestantische Passion. 1997, pp. 1469-1487.

- ↑ Hilbrands: Johannes Sebastian Bach as an interpreter of the Bible in his St. John Passion. 2011, p. 274 f.

- ^ For example, in the first volume of the Bach documents: Neumann (Ed.): Writings from the hand of Johann Sebastian Bach. 1963, p. 238.

- ↑ Joshua Rifkin: The Chronology of Bach's Saint Matthew Passion. In: The Musical Quarterly . Vol. 61, 1975, p. 360 ff.

- ↑ Christoph Wolff also completes the dates in his biography Johann Sebastian Bach from 2000/2005 in his table 8.16: Passion performances in Leipzig 1723–1750 .

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. 2000, p. 206.

- ↑ Wolff: The world of Bach cantatas. Vol. III. 1998, p. 16.

- ^ Dude: Bach. Life and work. 2000, p. 450.

- ^ Neumann (ed.): Documents from the hand of Johann Sebastian Bach. 1963, p. 177.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. 2000, p. 295 f.

- ^ Platen: Johann Sebastian Bach. The St. Matthew Passion. 1997, p. 214 f.

- ↑ Bach digital: Autograph of the St. Matthew Passion , accessed on March 25, 2018.

- ^ Christoph Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. 2000, p. 298.

- ↑ a b c d Heinemann: The Bach Lexicon. 1997, p. 366.

- ↑ Bach's original score can be viewed on the library's digitized collections page: Autograph .

- ↑ Peter Wollny: When noteheads fall out of the scores , accessed on March 25, 2018.

- ↑ Peter Wollny: Tennstedt, Leipzig, Naumburg, Halle - New Findings on the Bach Tradition in Central Germany. In: Bach yearbook . 2002, pp. 29–60, here pp. 36–47. doi: 10.13141 / bjb.v20021740

- ^ Christoph Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. 2000, p. 297.

- ^ Platen: Johann Sebastian Bach. The St. Matthew Passion. 1997, pp. 31-33.

- ^ Platen: Johann Sebastian Bach. The St. Matthew Passion. 1997, pp. 216-218.

- ^ Felix Loy: The Bach reception in the oratorios by Mendelssohn Bartholdy. Schneider, Tutzing 2003, ISBN 3-7952-1079-8 , pp. 17, 27.

- ↑ Sachiko Kimura: Mendelssohn's revival of the St. Matthew Passion (BWV 244). An examination of the sources from a performance perspective. In: Bach yearbook . Vol. 84, 1998, pp. 93-120. doi: 10.13141 / bjb.v19981657

- ↑ Michael Heinemann, Hans-Joachim Hinrichsen (Ed.): Bach and posterity. Vol. 1: 1750-1850. Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 1997, p. 311.

- ↑ St. Matthew Passion (JS Bach). In: Austrian Biographical Lexicon 1815–1950 (ÖBL). Volume 2, Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, Vienna 1959, p. 108.

- ↑ Heinemann (Ed.): The Bach Lexicon. 2000, p. 366 f.

- ^ Platen: Johann Sebastian Bach. The St. Matthew Passion. 1997, p. 218 f.

- ↑ Werner-Jensen: Reclam's music guide Johann Sebastian Bach. Vol. 2. 1993, p. 249.

- ↑ Ferruccio Busoni: On the drafting of a staged performance of JS Bach's St. Matthew Passion . In: On the unity of music . M. Hesse, Berlin 1922, p. 341 ff .

- ^ Platen: Johann Sebastian Bach. The St. Matthew Passion. 1997, p. 234.

- ^ John Neumeier: Texts on the ballet of the St. Matthew Passion by Johann Sebastian Bach. In: Joachim Lüdtke (Ed.): Bach and posterity. Vol. 4: 1950-2000 . Laaber-Verlag, Laaber 2005, pp. 323-348.

- ↑ Heinemann (Ed.): The Bach Lexicon. 2000, p. 367.

- ^ Platen: Johann Sebastian Bach. The St. Matthew Passion. 1997, pp. 226-229.

- ^ Platen: Johann Sebastian Bach. The St. Matthew Passion. 1997, p. 230 f.

- ^ Platen: Johann Sebastian Bach. The St. Matthew Passion. 1997, pp. 40 f., 118-213.

- ↑ Boyd: Johann Sebastian Bach. Life and work. 1992, p. 199 f.

- ↑ Konrad Küster (Ed.): Bach Handbook. 1999, p. 466.

- ^ Platen: Johann Sebastian Bach. The St. Matthew Passion. 1997, pp. 41-44.

- ^ Neumann (ed.): Documents from the hand of Johann Sebastian Bach. 1963, p. 237 f.

- ↑ Bartelmus: The St. Matthew Passion. 1991, p. 26.

- ^ Breig: Bach, Johann Sebastian. 1999, col. 1490.

- ↑ Axmacher: My Heyland wants to die out of love. 1984, p. 197.

- ↑ Werner-Jensen: Reclam's music guide Johann Sebastian Bach. Vol. 2. 1993, p. 250.

- ↑ a b Bartelmus: The St. Matthew Passion. 1991, p. 38.

- ↑ Werner-Jensen: Reclam's music guide Johann Sebastian Bach. Vol. 2. 1993, p. 265.

- ^ Werner Neumann: Handbook of the cantatas by Johann Sebastian Bach. 5.On. 1984, Breitkopf & Härtel, Wiesbaden 1984, ISBN 3-7651-0054-4 , p. 6.

- ↑ Werner-Jensen: Reclam's music guide Johann Sebastian Bach. Vol. 2. 1993, p. 259.

- ↑ Konrad Küster (Ed.): Bach Handbook. 1999, p. 466 f.

- ^ Melamed: Choir and chorale movements. 2006, p. 178.

- ^ Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. 2000, p. 387.

- ↑ Bartelmus: The St. Matthew Passion. 1991, p. 53.

- ↑ Boyd: Johann Sebastian Bach. Life and work. 1992, p. 197.

- ^ Neumann (Ed.): Foreign-written and printed documents on the life story of Johann Sebastian Bach 1685–1750. 1969, p. 141.

- ^ Christoph Wolff: Johann Sebastian Bach. 2000, p. 206.

- ↑ Werner-Jensen: Reclam's music guide Johann Sebastian Bach. Vol. 2. 1993, p. 248.

- ↑ Steiger: The theological meaning of the double choir in Johann Sebastian Bach's "St. Matthew Passion". 1983, p. 277.

- ↑ Christoph Wolff (Ed.): The world of Bach cantatas. Vol. III. 1998, p. 154.

- ^ Platen: Johann Sebastian Bach. The St. Matthew Passion. 1997, p. 228.

- ↑ See on the consequences of a strict spatial division into two groups of musicians: Konrad Küster (Ed.): Bach Handbook. 1999, pp. 452-467.

- ↑ Reinhard Brembeck: What is floating down from the gallery? The new St. Matthew Passion: the realization that Johann Sebastian Bach didn't know a choir in the modern sense is only slowly gaining ground. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung , 1./2. April 2010.

- ↑ Andrew Parrott: Bach's choir: for a new understanding. 2003.

- ^ Ton Koopman : Aspects of performance practice . In: Christoph Wolff (Ed.): The world of Bach cantatas. Volume 2. Johann Sebastian Bach's secular cantatas . JB Metzler, Stuttgart / Weimar 1997, ISBN 3-7618-1276-0 , p. 220-222 . (Special edition 2006).

- ↑ Steiger: The theological meaning of the double choir in Johann Sebastian Bach's "St. Matthew Passion". 1983, p. 275.

- ↑ Axmacher: “My Heyland wants to die for love”. 1984, p. 170.

- ↑ Steiger: The theological meaning of the double choir in Johann Sebastian Bach's "St. Matthew Passion". 1983, p. 278.

- ↑ Bouman: Music for the Glory of God. 2000, p. 29.

- ↑ Leaver: Bach's Theological Library. 1983; Petzold: Between Orthodoxy, Pietism and Enlightenment . 1982.

- ↑ Konrad Küster (Ed.): Bach Handbook. 1999, p. 455 f.

- ↑ Konrad Küster (Ed.): Bach Handbook. 1999, pp. 458-460.

- ↑ Werner-Jensen: Reclam's music guide Johann Sebastian Bach. Vol. 2. 1993, p. 262.

- ↑ Steiger: The theological meaning of the double choir in Johann Sebastian Bach's "St. Matthew Passion". 1983, pp. 277-283.

- ↑ a b Platen: Johann Sebastian Bach. The St. Matthew Passion. 1997, p. 50.

- ↑ a b c Bartelmus: The St. Matthew Passion. 1991, p. 28.

- ↑ Hilbrands: Johannes Sebastian Bach as an interpreter of the Bible in his St. John Passion. 2011, p. 287.

- ↑ Axmacher: “My Heyland wants to die for love”. 1984, p. 177 f.

- ^ Platen: Johann Sebastian Bach. The St. Matthew Passion. 1997, p. 185.

- ↑ Bartelmus: The St. Matthew Passion. 1991, p. 36.

- ↑ Johan Bouman: Music for the Glory of God. 2000, p. 44 ff.

- ^ Schmitz: The oratorical art of JS Bach. 1970, pp. 61-84.

- ^ Schmitz: The oratorical art of JS Bach. 1970, p. 65. This is also the case in the original with the text "Weh and Ach offends the soul a thousand times over".

- ^ Schmitz: The imagery of word-bound music. 1976, p. 60.

- ↑ Johan Bouman: Music for the Glory of God. 2000, p. 84 f.

- ↑ Bartelmus: The St. Matthew Passion. 1991, pp. 33-35, 44-46.

- ^ Johann Mattheson: The newly opened orchestra. Hamburg 1713, pp. 236-251 ( online ), accessed on October 10, 2011.

- ↑ Bartelmus: The St. Matthew Passion. 1991, p. 41.

- ↑ Bartelmus: The St. Matthew Passion. 1991, p. 24.

- ^ Platen: Johann Sebastian Bach. The St. Matthew Passion. 1997, p. 139.