Theilenhofen Castle

| Theilenhofen Castle | |

|---|---|

| Alternative name | Iciniacum |

| limes | ORL 71a ( RLK ) |

| Route (RLK) | Rhaetian Limes, route 14 |

| Dating (occupancy) | Wood-earth camp: around 100 AD or after 100/101 AD; Stone fort: around 126 AD until 259/260 AD at the latest. |

| Type | Cohort fort |

| unit | Cohors III Bracaraugustanorum equitata |

| size | 196 × 144 m (approx. 2.8 ha) |

| Construction | a) wood-earth b) stone fort |

| State of preservation | Fort marked by paths and replanting; Fort bath preserved |

| place | Theilenhofen |

| Geographical location | 49 ° 5 '21.8 " N , 10 ° 50' 49.4" E |

| height | 499 m above sea level NHN |

| Previous | Gnotzheim Fort (southwest) |

| Subsequently | So-called Second Ellingen Roman Camp (east) Ellingen Fort (east-south- east) Weißenburg Fort (south-east) |

| Backwards | Fort Munningen (southwest) |

| Upstream |

Small fort at the Hinteren Schloßbuck (northwest) Gunzenhausen fort (northwest) Gündersbach small fort (east) |

The fort Theilenhofen , in the ancient Iciniacum called, is a Roman military camp close to the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes (ORL), a UNESCO World Heritage Site , and northwest of the village Theilenhofen in the district of Weissenburg-Gunzenhausen in Bavaria . The fortification, which was probably built for around 480 infantrymen and 128 horsemen ( Cohors equitata ) to secure the border, was lost when the Limes fell around AD 259/260.

location

The fort responsible for guarding the border area was located in the flat hollow of a high plateau around 90 meters above the Altmühl valley , at the upper end of the small Echerbach valley coming from the west. His remains are about 600 meters northwest of the village Theilenhofen in the corridor "Die Weil". The Rhaetian Wall is around 2.2 kilometers away. Field paths run along the edge of the fort's no longer visible; Trees mark the corners of the fortification. The location was chosen so favorably that one could pick up signals from nine to ten watchtowers on the Limes from one tower of the complex and also otherwise had a wide all-round view of the adjacent land.

Research history

As the field name "Die Weil" (from Latin villa ) expresses, the knowledge of the existence of an ancient site was probably never completely lost, especially since according to the Theilenhofen parish description, several shoe- high remains were visible in the landscape in the 17th century obviously left out of the tillage. In particular, the remains of the massively built Principia will have belonged to these ruins, as they were probably reminiscent of a villa . It is assumed that the rising Roman remains were only demolished in the 18th century in order to be able to plow the last open land in this area. In the first Bavarian survey, which was made here in 1820, only arable parcels can be seen on the map. In the course of their field work, the farmers had leveled any signs of the fort that might still be visible. From the 18th century, sources report that “Roman burials” were found in the area. In 1820 a "sweat bath", known today as a military bath, was discovered 250 meters west of the fortification in the Echterbach valley basin. The theologian and historian Andreas Buchner was the first to equate Theilenhofen with the ancient Iciniacum , even if he later refrained from this theory. This Roman name is recorded on the Tabula Peutingeriana , the medieval copy of a Roman road map. In the second annual report of the historical association in the Rezat district (1832), Buchner's consideration was positively received and the place was described as follows: "Here, however, the ruins of a vast colony can be found and in the same continual Roman coins and other antiquities in significant numbers." the treatises of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences in 1838 read:

“It's not uncommon to come across old masonry and now and then on torn pieces of Roman roads. Everywhere old weapons, household items, idols, bricks with graceful cornices, fragments of glass, Sami crockery, sheet iron, oxidized iron, and lead are being excavated. In this area imperial coins emerged in such abundance in the daylight that the farmers often paid for their beer in the taverns with Roman money. "

In 1879, the doctor and hobby researcher Heinrich Eidam (1849–1934) examined an 87-meter-long piece of the western enclosure wall. In the following years between 1879 and 1887 he exposed most of the west wall, the entire east wall and a large section of the north wall with the western flank tower of the Porta praetoria , which belonged to the northern main gate of the fort. Only after these discoveries and the discovery of a brick temple with the abbreviation of the CIIBR unit , which was once stationed here , was early research certain that a fort was under the ground. During the years of these excavations, the ground monument attracted residents of the village of Theilenhofen. So the Wagner Meier carried the earth around the east gate and in 1884 the farmer Karg dug himself at the Porta praetoria . In doing so, he also exposed longer pieces of the north wall on his own. From 1892 to 1895, in his function as route commissioner for the Reichs-Limeskommission (RLK) , Eidam continued to investigate the camp site. In 1894, during the excavation inside the fort, he met the high school professor Josef Fink (1850–1929) and the archaeologist Felix Hettner (1851–1929). 1902) and Friedrich Winkelmann (1852–1934) took turns.

As part of the land consolidation carried out in 1969/1970 , the situation of the fort area, which was no longer recognizable above ground and which had caused a strong breakdown by peasant parcels, was to be improved. The aim was therefore to bring about a new land order that should not only protect the building remains preserved underground, but also facilitate future research. The Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation was able to fully comply with the archaeological concerns through regulations with the Land Consolidation Directorate . As a result of the land consolidation, the fort bath was rediscovered when the fish ponds were built and researched by Fritz-Rudolf Herrmann and the taxidermist and excavation technician Karl Schneider from 1968 to 1970 using modern methods. After the inventory, the facility was opened to the public. The dimensions of the fort in the area were traced by planting trees.

In 2007 a magnetometer survey of the fort site began. The investigation was completed in autumn 2008 with the inspection of the southern end of the fort. The prospected area also included the wood-earth warehouse to the west, which was first identified in 1976 with the help of aerial archeology . In spring 2010 and 2011, the geophysical prospecting of the camp village ( vicus ) in the wider area of the two fortifications followed.

Stone fort

Building history

It is believed that an older wood and earth fort was built around 100 AD, which older research has not yet been able to determine. A simple wooden fort, recorded in 1976 with the help of aerial archeology , which was raised directly in front of the western long side of the later stone fort in the dimensions 155 × 130 meters (1.9 hectares), could come from this early phase. Trial cuts in the ditch area, which were carried out in 1976 by the Bavarian State Office for the Preservation of Monuments , were able to determine the volatility of the camp due to the weak walls. The ancient historian Hartmut Wolff (1941–2012) rated this facility as the predecessor camp of Theilenhofen and the archaeologist Dietwulf Baatz assumed that the occupation of the early Theilenhofen camp could have originated from the Munningen fort of the same size in the Ries , which was built around 110 AD at the latest Was evacuated.

According to the dendrochronological dating of the first Theilenhofen military bath made by Franz Herzig in the year 126 AD, it can be assumed that the stone fort was also built around this time, during the reign of Emperor Hadrian (117-138).

It is also certain that in the first half of the reign of Emperor Antoninus Pius (138–161 AD) at the latest, the Cohors III Bracaraugustanorum, once set up in Braga in northern Portugal, became an ancestral unit in Iciniacum and remained until the fall. A fragment of a military diploma discovered in Nördlingen in 2008 dates from the year 156 AD and could date this somewhat earlier. Because the diploma was issued for an expedes of this cohort, who, according to the archaeologist Bernd Steidl , must have already entered the Cohors III Bracaraugustanorum in Theilenhofen during a regular period of service around 130/131 .

At what times the troops, which changed several times between Raetia and other provinces, were stationed in Theilenhofen has not yet been clarified. Evidence for the existence of the Cohors III Bracaraugustanorum there are brick stamps, an altar for the goddess Fortuna balnearis and a splendid officer's helmet that was found. Since the helmet is assigned to the cavalry, inscriptions speak of Turmae (squadrons) and the stone fort has special dimensions (196 × 144 meters = approx. 2.8 hectares), it is certain that the cohort handed down for Theilenhofen is a mixed unit Cavalry and infantry (Cohors equitata) must have been, as was the case in Fort Pfünz to the east . Both the excavations in Eidam and the magnetic field measurements came to the conclusion that the fort had burned down.

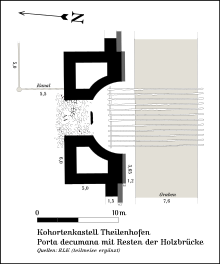

Enclosure

Based on investigations, research suspects that the Roman fort extension in Stein followed a generally applicable standard plan, which was adapted to local conditions and the planned number of crews. The surveyors laid the rectangular stone fort with its four gates on the flanks almost exactly in a north-south direction, with the Praetorial Front, i.e. the side of the camp facing the enemy, facing north towards the Limes. Theilenhofen was surrounded by a triple-pointed ditch. Only the two inner trenches exposed in front of the Porta principalis sinistra (west gate) and the Porta principalis dextra (east gate). All other ditch obstacles had to be crossed with wooden bridges. As a special feature, in front of the rear south gate, the Porta decumana , remains of the former plank bridge that reached over the first ditch were found. The vicus , the camp village belonging to the fortification, began behind the south gate . The Porta decumana of Theilenhofen shows architecturally a very rare type of construction for castles on the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes, as the single-gate entrance arches inward in a semicircle ("niche gate"). Such a funnel-shaped narrowing entrance to the gate lock was also discovered at the gate of the small Bavarian fort “In der Harlach” , at the Faimingen fort , but also in the Lower Austrian legionary camp Carnuntum . Above all, however, it was found at North African military sites such as the Algerian legionary camp Lambaesis and the Bu Njem fort (222 AD) on what is now Libyan soil. The architectural history of this type of door dates back to the late 2nd century.

The Roman construction crews built a tower in each of the four corners of the fort. The archaeologists were only able to discover two additional intermediate towers on the 1.5 meter thick defensive wall in the area of the Retentura , the rear storage zone.

During the excavations in the 19th century, a drainage ditch was found that runs directly south of the west gate at an angle of around 70 degrees to the defense to the south-west and runs under the three fort ditches. Its further course could be traced by the magnetometer inspection. It turned out that the canal took account of the wood-earth store immediately to the west, because it continues from the gate of the stone fort after around 140 meters around the southeast corner of the ground store and then stays exactly in a westerly direction parallel to the south-facing one Flank of this fortification. In ancient times, the canal went as far as the military bath, which is located in front of the southwest corner of the wood-earth warehouse.

Interior development

As is usual with this type of building, the two camp streets that came from the four gates crossed at the point where the Principia , the staff building of the garrison, was built. These Principia , which also followed a standard scheme, were 40 × 40 meters in size and almost square in Theilenhofen. The 60 × 19 meter multi-purpose hall in front of the actual staff building was located above the Via principalis , which in this case was oriented almost in a west-east direction. The Principia of Iciniacum had no semicircular apse trained for the regimental shrine (due to their time position Aedes ). The design of the sanctuary with apses only became customary in the forts, especially in the Germanic area, from the middle of the 2nd century. An at least partial basement of the Aedes is also completely absent . The units normally kept their troop coffers in these cellars. Fragments of a bronze statue were recorded in the multi-purpose hall, which could have come from the imperial statue that was once erected there. They date to the first half of the 3rd century.

The Horreum , the storage building of the camp with its structured wall templates, was in the rear storage area ( Retentura ) behind the Principia . To the left of the staff building, the RLK discovered a small room with a hypocaust . As the geophysical survey in 2007 showed, this room was part of a 41 × 32 meter building complex, the layout and function of which remains unclear without modern excavations. It was interpreted by Eidam as the house of the commandant ( praetorium ). For Jörg Faßbinder it is the 26 × 32 meter structures on the eastern flank of the Principia that could belong to a praetorium . According to the magnetogram measurements, a built-in courtyard and massive cellars appear to be emerging here.

The measured structures on the left and right of the horreum could have belonged to workshops ( Fabricae ) and / or a hospital ( Valetudinarium ). In addition, Faßbinder recognized wooden team barracks and horse stables in the front camp (Praetentura) on the camp road ( Via praetoria ) falling from the north . Their arrangement is very similar to that of Fort Pförring . Along the northern Lagerringstrasse, to the left and right of Via praetoria, there were two double barracks about 60 meters long, in which horse and rider were housed. The living quarters of the centurion and possibly other officers, non-commissioned officers and staff were located in the head buildings facing west or east. Following these double barracks, simple crew barracks with a cell-like structure were built to the south, as is typical for these camp buildings. Two barracks of the same type are also known from the Retentura . However, the southernmost part of the camp has not yet been measured with the magnetometer.

The main streets of the camp were paved. This paving was clearly perceived during the geophysical exploration in 2007.

Research assumes that the fort sank with the Limes Falls around AD 259/260. Nothing is visible above ground today. The entire area is used for agriculture.

- Findings at the time of the Reich Limes Commission

Wood-earth warehouse

Immediately to the west of the stone fort is a rectangular, only lightly reinforced wood-earth camp, the size of which is 160 × 142 meters measured from the middle of the ditch to the middle of the ditch. It has rounded corners. In contrast to the stone fort, which faces north-south with its long sides, the smaller underground storage facility faces west-east. Immediately after leaving the east gate, the main road of this camp, running from west to east, bend towards the northeast and led directly to the nearby west gate of the stone fort. As the ditch of the stone fort leading to the bath shows, the wood-earth camp may have formed an integrative unit with the cohort fort for a certain point in time. A road also coming out of the west gate of the stone fort, which led in a wide curve over the northeast corner of the wood-earth camp, cuts its ditch in its northwest corner and thus obviously belongs to a phase after the demolition of the earth camp. The magnetic image recording shows structures in the eastern part of this camp that probably belonged to crew barracks. A more precise definition of the purpose or the time of this wood-earth store cannot be made without further research. The geophysical prospection made it clear that the camp area was probably abandoned later and integrated into the camp village, which also expanded to the west of the stone fort.

Fort bath

250 meters west of the fort, separated from the south-west corner of the short-term camp by a modern road, are the restored stumps of the military bath ( Balineum ) next to a fish pond . It was assumed that the unusually large distance to the garrison resulted from the local water conditions. The last of the two excavated construction phases of the thermal baths was preserved. In 2002 a dendrochronological dating was carried out. The sample from the older bath, which was partly built in wood, dates back to the year 126 AD. It can therefore be assumed that the first Theilenhofen military bath will be built in this year.

The thermal bath, first described as a "sweat bath" in 1820, later fell out of view again. Its approximate location next to a pond at the upper end of the Echerbach valley was, however, mentioned by the Imperial Limes Commission in the overview plan for the fort as a “bath”. In the 20th century the place became a wild garbage dump, which was only renovated in the course of land consolidation. When ponds were built for water retention at the time, the subsequently restored and partially reconstructed fort bath was "rediscovered" and has since become a well-known visitor destination.

The remains visible today, 16.5 × 28.5 meters in size, are designed in the style of Roman baths. Seven rooms can be made out. The thermal bath, the floor of which was equipped with high-quality Solnhofen limestone , was entered from the north side. There was a corridor that was also a dressing room (apodyterium) . A consecration stone to the goddess Fortuna was found there in 1970 , dated between 140 and 144.

- Fortun (ae)

- Eye (ustae)

- sacrum

- coh (ors) III Br (acaraugustanorum)

- cui prae (e) st

- Vetelli (us)

- v (otum) s (olvit) l (ibens) l (aetus) m (erito)

Translation: Consecrated to Fortuna Augusta; the 3rd Braga cohort, which Vetellius commands, has honored its vows gladly, joyfully and for a fee.

Perhaps also from the bath came a relief that was discovered in 1820 "on the Weil" and showed a river god. This stone, which was once in the district and city museum of Ansbach, is now lost.

The stone and brick supports for the hypocaust heating system, some of which were still in good condition, were removed before the renovation to protect them from the weather and vandalism. In the Burgmuseum Grünwald , a branch of the Archaeological State Collection in Munich, they have been re-erected and documented in a partial reconstruction how a Roman heating system works.

Troop

The troops stationed in Theilenhofen, the Cohors III Bracaraugustanorum (equitata) to torquata , (3rd partially mounted cohort from Bracara Augusta ), originally recruited in Braga in northern Portugal, was a 500-man border guard . After evaluating the magnetogram, Faßbinder assumes that this unit consisted of ten platoons , six of which were infantry groups ( Centurien ) and a cavalry regiment of four squadrons (Turmae) . The name sagittaria (archer), which appeared in the military diplomas of AD 116 , did not previously bear it. The unit therefore had at least some contingents of archers, at least temporarily. The troops are also mentioned in the last known diploma from Regensburg-Kumpfmühl in the year 266 beyond the Limesfall in AD 259/260 and the fall of the Theilenhofen fort. There are no later inscribed documents that can be dated. What happened to the unity after AD 266 is no longer known.

The name of a commander of the Cohors III Bracaraugustanorum in Theilenhofen: Vetellius has been preserved on the consecration stone from the bath mentioned above .

Vicus

The camp village ( vicus ) of the fort extended along the road coming from the south gate to the edge of today's village Theilenhofen. Its extent can only be guessed at based on individual finds, as no excavations have taken place so far. The most important finds from the land of the vicus , which is used today for agriculture, include two Roman helmets, an infantry helmet and a cavalry helmet, which accidentally came out of the ground during a plowing competition in 1974. A follow-up examination revealed that the helmets had been lying on the screed in the middle of a room. The building belonging to it was destroyed in a fire after 189 AD, perhaps not until the 3rd century. It is also possible that the helmets were only stored in the house after the fire.

Found good

Militaria

Riding helmets

One of the two helmets found in the fort vicus is lavishly decorated with drifting work, extremely rare of its kind and belongs to the maskless type Guisborough / Theilenhofen . Pieces of low material thickness such as the one made from Iciniacum are mainly viewed in research as pure so-called parade helmets, which were actually not intended for military use, but were worn during the regularly held, standardized cavalry exercises ("tournaments") of the cavalry Should make the level of training clear. The equestrian tract of Flavius Arrianus from the year 136 AD is the first source for these exercises today . A copy of this is exhibited in the RömerMuseum Weißenburg .

The ornate cheek flap of another equestrian helmet, which was almost completely preserved when it was found, has already been published in the Limeswerk (ORL) and is in a dramatically worse condition today in the Gunzenhausen local history museum. The relief visible on the flap shows a standing bacchante who is holding a bowl in his left hand and a stick in his right. In comparison with the historical photo from the ORL, the find was almost completely preserved when it was found.

Infantry helmet

The second helmet found together with the equestrian helmet of the Koblenz-Bubenheim / Weiler type, which comes from the Hellenistic tradition, belongs to the widespread genus of the Weisenau type . This type of helmet, once further developed from Celtic models, was worn in the Roman army since the days of the late republic, and it was subject to multiple changes until its development ended in the late 2nd or early 3rd century with the heavily armored Niederbieber type .

Its simple design in bronze allows it to be identified as a helmet for auxiliary troops. The cohort stationed in Theilenhofen also belonged to this group of troops. As the cross-shaped reinforcement on the dome shows, the helmet was made in the first half of the 2nd century. A datable, early comparative piece of this type of construction, which, however, belonged to a legionnaire (imperial-Italian type Hebron), was lost during the Bar Kochba uprising. With the advent of the cross-shaped reinforcements, the traditional helmet bushes for legionaries and - where available - auxiliary troops were abolished.

Other military finds

The excavation finds also include the remains of harness sets such as crescent-shaped pendants, but also metal plates from scale armor. As evidence shows, scale armor was not only worn by infantrymen and cavalrymen. In Dura-Europos in Syria three Roman cataphract horse armor were found, which confirmed the takeover of this type of rider by the Romans. The small-scale sheds from Theilenhofen certainly belonged to the equipment of a soldier. The luggage on marches also included pegs, which also came out of the ground in Theilenhofen.

Terra Sigillata

In addition to the old finds from the excavations of the RLK, field inspections have been carried out time and again, during which sigillata fragments are also found. It was found that 50 percent of the total share of Theilenhofen sigillata from southern Gallic goods came from the French Banassac in the Lozère department . Banassac has been shipping to many provinces since around AD 100. Pieces of this pottery have become known especially in southern Germany and following the Danube. During the reign of Emperor Hadrian (117-138) this manufacture came to a standstill. La Graufesenque , which has been in operation since Tiberian times , was an older, important manufacturing center in southern Gaul . Almost 300 potters from there are known by name. In the late phase towards the end of the 1st century, the businesses of this place tried to assert themselves against the emerging competition from Banassac with increasingly cheaper and thus poorer quality products, which did not succeed. The Terra Sigillata from La Graufesenque recovered in Theilenhofen comes mainly from the factories of the manufacturers Mercato and Mascuus. The early date of the found sigillata confirms the assumption that the stone fort must have been preceded by a predecessor. After an evaluation of the reading findings known at the time, the ceramics expert Hans-Günther Simon (1925–1991) found in 1978 that the oldest Theilenhofen sigillata fragments are younger than those from the forts Gnotzheim (founded in 81/96 AD) and Weißenburg ( founded around 90 AD) known material, but older than the finds from Pförring (founded at the beginning of the 2nd century), which is why the Theilenhofen founding date can be determined around the year 100 AD. Since South Gallic Drag. 29 picture dishes were not found in Theilenhofen, the archaeologist Barbara Pferdehirt postponed the founding approach to the time "after 100/101 AD".

Coins

The abundance of coins was noticed very early on. In 1837 silver and bronze coins found on the "Weil" were named for the following rulers and personalities: Agrippa, Nero , Vespasian , Titus , Trajan , Hadrian , Aelius, Antoninus Pius , Septimius Severus , Caracalla , Julia Maesa , Maximinus Thrax and Valerian .

Vessels

A find of particular beauty was a bronze jug handle, which was attached to the no longer present vessel with bird protomes . Its attachment forms a Medusa head , the eyes of which are inlaid with silver. The piece was donated to the Royal Antiquarium in 1840 and is now in the Staatliche Antikensammlungen in Munich.

Lost property

The found material from Theilenhofen is now in the Museum of Prehistory and Early History Gunzenhausen , in the Archaeological State Collection in Munich , in the Burgmuseum Grünwald , in the collection of the Natural History Society in Nuremberg and in the Germanic National Museum in Nuremberg .

Monument protection

Theilenhofen fort and the facilities mentioned have been part of the UNESCO World Heritage as a section of the Upper Germanic-Rhaetian Limes since 2005 . In addition, they are protected as registered ground monuments within the meaning of the Bavarian Monument Protection Act (BayDSchG) . Investigations and targeted collection of finds are subject to authorization, accidental finds must be reported to the monument authorities.

See also

literature

General

- Johann Schrenk, Werner Mühlhäußer: Land on the Limes. In the footsteps of the Romans in the Hesselberg - Gunzenhausen - Weißenburg region. Schrenk, Gunzenhausen 2009, ISBN 978-3-924270-57-5 , especially pp. 102-104.

- Thomas Fischer , Erika Riedmeier-Fischer: The Roman Limes in Bavaria. Pustet, Regensburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7917-2120-0 .

- Thomas Fischer, in: Wolfgang Czysz u. a .: The Romans in Bavaria. Nikol, Hamburg 2005, ISBN 3-937872-11-6 , p. 522 f.

- Dietwulf Baatz : The Roman Limes. Archaeological excursions between the Rhine and the Danube. 4th edition. Gebr. Mann, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-7861-2347-0 , p. 284 ff.

- Britta Rabold , Egon Schallmayer , Andreas Thiel : The Limes. Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1461-1 .

- Thomas Fischer: forts Ruffenhofen, Dambach, Unterschwaningen, Gnotzheim, Gunzenhausen, Theilenhofen, Böhming, Pfünz, Eining. In: Jochen Garbsch (Ed.): The Roman Limes in Bavaria. 100 years of Limes research in Bavaria. (= Exhibition catalogs of the Prehistoric State Collection 22), 1992, p. 37 ff.

- Günter Ulbert , Thomas Fischer: The Limes in Bavaria . Theiss, Stuttgart 1983, ISBN 3-8062-0351-2 .

- Ludwig Wamser , Christof wing , Bernward Ziegaus (ed.): The Romans between the Alps and the North Sea . Zabern, Mainz 2000, ISBN 3-8053-2615-7 and ISBN 3-927806-24-2 (Landesausstellung Rosenheim 2000; series of publications by the Archäologische Staatssammlung 1), p. 116, fig. 90,3

Individual studies

- Heinrich Eidam : Theilenhofen fort. In: Ernst Fabricius , Felix Hettner , Oscar von Sarwey (eds.): The Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes of the Roemerreiches B VII No. 71a, Petters, Heidelberg, 1905

- Jörg Faßbinder: New results of the geophysical prospection at the Upper Germanic-Raetian Limes. In: Andreas Thiel (ed.): New research on the Limes . 4th specialist colloquium of the German Limes Commission 27./28. February 2007 in Osterburken, Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2251-7 , (= contributions to the Limes World Heritage Site 3), pp. 153–171, especially pp. 156–161.

- Markus Gschwind : Reflex bow stiffeners and slingshots from Iciniacum / Theilenhofen, Gunzenhausen, Mediana / Gnotzheim and Ruffenhofen. For arming Raetian auxiliary units in the middle imperial period. In: Contributions to archeology in Middle Franconia. Volume 5. Faustus, Büchenbach 1999, p. 157 ff.

- Markus Gschwind, Salvatore Ortisi : On the cultural independence of the province of Raetia. Almgren 86, the raetical form of the so-called Pannonian trumpet brooches . In: Germania 79/2, 2001, pp. 401-416, Fig.1,4.

- Eveline Grönke: The fibulae from the area of the Roman forts and the vicus in Theilenhofen, district of Weißenburg-Gunzenhausen . In: Bavarian History Leaflets 70, 2005, pp. 103-132.

- Eveline Grönke: A Roman cicada primer from Theilenhofen. Weissenburg-Gunzenhausen district. In: Contributions to archeology in Middle Franconia. Volume 4. Faustus, Büchenbach 1998, p. 138 ff.

- Hans Klumbach , Ludwig Wamser: A new find of two extraordinary helmets from the Roman Empire from Theilenhofen, Weißenburg-Gunzenhausen district. A preliminary report. In: Annual Report of the Bavarian Heritage Monument Care 17/18, 1978, pp. 41–61.

- Carsten Mischka , Jürgen Obmann, Peter Henrich : Forum, basilica and a scenic theater on the Raetian Limes? In: The Limes. News bulletin of the German Limes Commission. 4, 2010 / issue 1. pp. 10–13.

- Carsten Mischka, Peter Henrich: Forum or Campus? Theater and plaza in Theilenhofen. In: The Limes. News sheet of the German Limes Commission 2, 2012 / Heft 2, pp. 4-7. ( online pdf )

- Hans-Günther Simon : Roman finds from Theilenhofen. In: Bavarian History Leaflets 43, 1978, pp. 25-56.

Web links

- Fort Theilenhofen , website of the German Limes Commission; accessed on February 23, 2016

- The Romans in Theilenhofen , website of the municipality of Theilenhofen; accessed on February 23, 2016

Remarks

- ↑ Klaus Schwarz : The preservation of soil monuments in Bavaria from 1970 to 1972 . In: Annual Report of the Bavarian Land Monument Care 11/12, 1970/71, pp. 156–250; here: p. 184.

- ↑ Andreas Buchner: Journey on the Devil's Wall. An investigation into the remains of the Roman protective institutions, etc. Montag-Weissische Buchhandlung, Regensburg, 1818. P. 73.

- ↑ (without naming the author): Second annual report of the historical association in the Rezat district. For the year 1831. Riegel and Wießner, Nürnberg 1832. p. 16.

- ↑ Franz Anton Mayer: Exact description of the Roman landmark known under the name of the Devil's Wall. In: Treatises of the Philosophical-Philological Class of the Royal Bavarian Bavarian Academy of Sciences. 2nd volume. 2. Dept. Lindauersche Hofbuchdruckerei, Munich 1837, p. 280.

- ^ Heinrich Eidam: Theilenhofen. (Castle.) In: Limesblatt. Notices from the route commissioners to the Reichslimeskommission. No. 15 (June 19, 1895). Pp. 421-424; here: pp. 421-422.

- ↑ a b Jörg Faßbinder: New results of the geophysical prospection on the Upper German-Raetian Limes. In: Andreas Thiel (ed.): New research on the Limes. Volume 3. Kommissionsverlag - Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2251-7 , p. 157.

- ^ Heinrich Eidam: Theilenhofen. (Castle.) In: Limesblatt. Notices from the route commissioners to the Reichslimeskommission. No. 15 (June 19, 1895). Pp. 421-424; here: p. 422.

- ↑ Klaus Schwarz : The preservation of soil monuments in Bavaria from 1970 to 1972 . In: Annual Report of the Bavarian Land Monument Care 11/12, 1970/71, pp. 156–250; here: p. 176.

- ↑ Jörg Faßbinder: Magnetometer prospection at Iciniacum fort near Theilenhofen, Weißenburg-Gunzenhausen district, Middle Franconia. In: The archaeological year in Bavaria 2007. Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2156-5 , pp. 73-77.

- ↑ a b Jörg Faßbinder: From Eining to Ruffenhofen. On the way to a magnetogram atlas of the Raetian Limes fort - results of the geophysical prospection in Bavaria. In: Peter Henrich (Ed.): Perspektiven der Limesforschung. 5th colloquium of the German Limes Commission . Theiss, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8062-2465-8 , (= contributions to the Limes World Heritage Site, 5), pp. 89-103; here: p. 97.

- ↑ Carsten Mischka , Cecilia Moneta: New geomagnetic prospections in the fort vici of the Raetian Limes . In: Peter Henrich (Ed.): The Limes from the Lower Rhine to the Danube. 6th colloquium of the German Limes Commission . Theiss, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-8062-2466-5 (= contributions to the Limes World Heritage Site, 6), pp. 123–135; here: p. 124.

- ↑ Hartmut Wolff : The Raetian army and its "military diplomas" in the 2nd century AD. In: Bayerische Prognistorblätter 65, 2000, pp. 155–172; here: p. 166 f.

- ↑ a b c Bernd Steidl : … civitatem dedit et conubium… Eight new fragments of military diplomas from Raetia . In: Bavarian history sheets 79, 2014, pp. 61–86; here: p. 71.

- ↑ Jochen Garbsch : Theilenhofen / Iciniacum. In: Walter Sölter (Ed.): The Roman Germania from the air . 2nd edition, Lübbe, Bergisch Gladbach 1983, ISBN 3-7857-0298-1 , p. 38.

- ↑ Bernd Steidl : … civitatem dedit et conubium… Eight new fragments of military diplomas from Raetia . In: Bavarian history sheets 79, 2014, pp. 61–86; here: p. 70.

- ↑ Fortun (ae) / Aug (ustae) / sacrum / coh (ors) III Br (acaraugustanorum) / cui prae (e) st / Vetelli (us) / v (otum) s (olvit) l (ibens) l (aeta ) m (erito) ( Ubi erat lupa, no.8887 ).

- ↑ a b Jörg Faßbinder: New results of the geophysical prospection on the Upper German-Raetian Limes. In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Neue Forschungen am Limes , Volume 3. Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2251-7 , p. 159.

- ↑ Jörg Faßbinder: New results of the geophysical prospection on the Upper German-Raetian Limes. In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Neue Forschungen am Limes , Volume 3, Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2251-7 , p. 158.

- ^ Anne Johnson : Roman castles . von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 112.

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz ): Römische Kastelle . von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 152.

- ↑ a b Jörg Faßbinder: New results of the geophysical prospection on the Upper German-Raetian Limes. In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Neue Forschungen am Limes , Volume 3, Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2251-7 , p. 160.

- ↑ Martin Kemkes: The image of the emperor on the border - A new large bronze fragment from the Raetian Limes. In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Research on the function of the Limes , Volume 2, Theiss, Stuttgart 2007, ISBN 978-3-8062-2117-6 , p. 144.

- ↑ a b c Jörg Faßbinder: New results of the geophysical prospection at the Upper German-Raetian Limes. In: Andreas Thiel (Ed.): Neue Forschungen am Limes , Volume 3. Theiss, Stuttgart 2008, ISBN 978-3-8062-2251-7 . P. 161.

- ^ Anne Johnson (German adaptation by Dietwulf Baatz ): Römische Kastelle . von Zabern, Mainz 1987, ISBN 3-8053-0868-X , p. 188 ff.

- ↑ Carsten Mischka, Cecilia Moneta: New geomagnetic prospections in the fort vici of the Raetian Limes . In: Peter Henrich (Ed.): The Limes from the Lower Rhine to the Danube. 6th colloquium of the German Limes Commission . Theiss, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-8062-2466-5 , (= contributions to the Limes World Heritage Site 6), pp. 123–135; here: p. 98.

- ↑ fort at 49 ° 5 '17.63 " N , 10 ° 50' 34.92" O .

- ↑ C. Sebastian Sommer : Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, Marc Aurel ...? - To date the systems of the Raetian Limes . In: Report of Bayerische Bodendenkmalpflege 56 (2015), pp. 321–327; here: p. 142.

- ^ Britta Rabold, Egon Schallmayer, Andreas Thiel: Der Limes. Theiss, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-8062-1461-1 , p. 120.

- ↑ AE 2011, 00856 ; www.ubi-erat-lupa.org: Altar for Fortuna ; accessed on November 21, 2016.

- ^ Corpus Signorum Imperii Romani . Germany I, 1. Raetia (Bavaria south of the Limes) and Noricum (Chiemsee area). From the estate of Friedrich Wagner . Habelt, Bonn 1973, p. 81.

- ↑ Peter Kolb: The Romans with us. Museum-Pedagogical Center Munich, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-934554-02-4 , ill. P. 116.

- ↑ CIL 16, 121 .

- ^ Fasti archaeologici. Annual Bulletin of Classical Archeology, 34-35, Vol. 2. 1979-1980 Florence 1987. p. 1125.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann: Riders like statues from Erz. Von Zabern, Mainz 1996, ISBN 3-8053-1819-7 , p. 88.

- ^ Heinz Menzel: Roman bronzes from Bavaria. Roman Museum Augsburg. Augsburg 1969. p. 46.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann: The Legions of Augustus. von Zabern, Mainz 1986, ISBN 3-8053-0886-8 , p. 172.

- ^ Daniel Peterson: The Roman Legions. Barett Verlag, Solingen 1994, ISBN 3-924753-42-3 , p. 32.

- ↑ Marcus Junkelmann : The riders of Rome. Part III. von Zabern, Mainz 1992, ISBN 3-8053-1288-1 , p. 161 u. 213.

- ^ A b Stefan Groh: The Insula XLI by Flavia Solva: Results of the excavations in 1952 and 1989 to 1992. Verlag des Österreichisches Archaeologische Institut, Vienna 1996, ISBN 3-900305-20-X , p. 158.

- ↑ Barbara horse shepherd: The Roman terra sigillata pottery in southern Gaul. Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of Southwest Germany 18. Aalen 1978, p. 15.

- ↑ Barbara horse shepherd: The Roman terra sigillata pottery in southern Gaul. Small writings on the knowledge of the Roman occupation history of Southwest Germany 18. Aalen 1978, p. 14.

- ^ Hans-Günther Simon : Roman finds from Theilenhofen. In: Bavarian History Leaflets No. 43, Beck, Munich 1978. pp. 25–56.

- ↑ Barbara Pferdehirt: The Roman occupation of Germania and Rhaetia from the time of Tiberius to the death of Trajan. Investigations into the chronology of southern Gaulish relief sigillata. In: Yearbook of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum 33, 1986. P. 291.

- ↑ Franz Anton Mayer: Exact description of the Roman landmark known under the name of the Devil's Wall. In: Treatises of the Philosophical-Philological Class of the Royal Bavarian Bavarian Academy of Sciences. 2nd volume. 2. Dept. Lindauersche Hofbuchdruckerei, Munich 1837. p. 281.

- ^ Heinz Menzel: Roman bronzes from Bavaria. Roman Museum Augsburg. Augsburg 1969. pp. 41-42.