Lolita (novel)

Lolita is the most famous novel by the Russian - American writer Vladimir Nabokov .

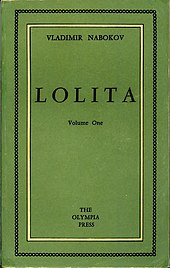

Via the detour of the first edition from 1955, published by the French-based publisher Olympia Press , which specializes in English-language erotica , Lolita reached the American readership in 1957 in excerpts and a year later in the full version and was soon distributed worldwide. In the afterword written in 1956, the native Russian Nabokov confessed that Lolita was his “declaration of love” to the English language , and countered the suspicion of pornography that initially accompanied the reception of the novel. The Russian version of Lolita (1967), which was slightly changed in detail, was done by himself.

The high artistic value of the multi-layered work was initially concealed by its scandalous topic: It is about the forbidden, namely pedophile, love affair between the first-person narrator , the literary scholar Humbert Humbert, who was born in France in 1910 , and Dolores Haze, who was twelve when they began their relationship in 1947 whom he calls Lolita. He describes the beginning and course of his one-sided passion as well as their two-year odyssey across the United States in a prison where he is waiting for his trial after the murder of his rival in 1952.

Coming from Nabokov's title character, the name Lolita has become a household name and has found its way into science (Lolita complex ), pop culture ( Lolicon ) and everyday language. The image of the sexually precocious, seductive girl that is usually associated with “Lolita” is, however, strongly narrowed and trivialized in comparison to the Lolita of the novel. The two film adaptations by Stanley Kubrick ( 1962 ) and Adrian Lyne ( 1997 ) also contributed to this.

Nabokov has stated several times that he particularly valued Lolita - his third novel in English, his twelfth overall. It brought the breakthrough in his writing career to the almost 60-year-old and freed him from his academic bread-and-butter job. The novel Der Zauberer , created in 1939 and published posthumously , is considered a preliminary study for Lolita .

content

The novel is preceded by the foreword by a fictional editor who informs the reader that the following text was written under the title Lolita or The Confessions of a White Race Widower by a prison inmate who uses the code name "Humbert Humbert" and was published on 16 November 1952, shortly before the start of his trial, died of complications from a coronary thrombosis .

The protagonist, born in Paris in 1910 , begins his notes with a brief outline of his life up to the point where he meets Lolita. He focuses on his first love in the summer of 1923: a relationship experienced as symbiotic , accompanied by the awakening of sexuality, with Annabel Lee of the same age, which remains unfulfilled by the early death of the beloved. From then on he sees himself fixated on a certain type of girl around the age of Annabel, to whom he (a “lonely wanderer, artist and madman”) feels magically attracted and which he therefore describes as “nymphets”; Obsessively he seeks her closeness, but can suppress his sexual desire. He describes his escape into a four-year marriage with cynical distance; The same applies to his stays in psychiatric clinics as well as short-term jobs as a teacher, perfume copywriter and expedition member. The only thing that gives him spiritual fulfillment and distraction at times is a commissioned work for a renowned publishing house, which he took on as a trained English specialist : a multi-volume manual of French literature for English-speaking students. He intends to continue this project when he - now living in the USA and financially secured by the pension of a deceased uncle - is looking for a place of retreat for the summer of 1947. In the small New England town of Ramsdale, in the house of the widow Charlotte Haze, he meets the ideal “nymphette”, twelve-year-old daughter Lolita, who is completely unprepared for him. In shock, everything that reminds him of his first love comes to life again, but is almost as quickly replaced by the present.

Although repulsed by the house and the owner, Humbert rented a room and allowed himself to be absorbed in everyday life, provided there was any contact with Lolita. Seismographically he perceives everything that concerns them and excites him; and he records it meticulously in diaries. The three weeks of rapprochement with her culminate in his mother's absence on a Sunday morning: he succeeds in converting an erotically charged teasing gimmick with her on the sofa into sexual manipulation and in a secret orgasm . His “relief” is twofold, as he takes credit for not having touched Lolita's “purity”. Before he can even begin to test whether and how the unexpected success can be converted into a strategy, there are a number of serious twists, all of which come from Charlotte.

First, she decides to send Lolita to summer camp earlier than planned and not to let her come back before the holidays are over. On the day Lolita left, she wrote to Humbert declaring her love and practically giving him the choice of either leaving or marrying her. In order to stay close to Lolita, he opts for marriage, and with the same, already practiced cynicism, he gets rid of the "duties" associated with it. Charlotte seems free of suspicion about his true feelings and intentions - until one day she gains access to his diaries and learns the full truth. She does not fall for his excuse that it was a draft novel. She writes three letters aimed at isolating Lolita from him. When going to the mailbox on the opposite side of the street, however, she runs into a car and dies.

In one fell swoop, everything changed for him. He is now Lolita's sole guardian ; the couple, who are closest friends with Charlotte, even consider him to be their biological father. He picks Lolita up early from summer camp on the grounds that her mother is in the hospital, and he stays with her for one night in a hotel. His plan: what he managed to do by chance on the sofa at home, from now on methodically by sedating Lolita with a sleeping pill . That fails because the remedy doesn't work. In the morning, Lolita takes the initiative and practices with him what she “learned” in summer camp: the sexual act. On the same day, Humbert informs her that her mother is dead and thus also dissuades her from wanting to return home; He had ruled out continuing his affair with her there as too risky from the start. The now beginning unsteady travel life forms the interface between part one and two.

Your first car trip is unplanned and takes you clockwise through almost all states of the USA. By visiting numerous attractions, Humbert tries to create shared experiences in order to bind Lolita to him. But that doesn't catch on with her, unlike the threatening backdrop that he creates after she has indicated that she could report him and take him to prison. Then, he announced, she would become a ward of the state and go to a home. So he succeeds in making her an accomplice; she will not make him a lover like Annabel. She knows her stimuli, to which he responds, and knows how to play with them, but only out of calculation - among other things, to increase the material benefits with which he rewards her sexual availability.

After a year, Humbert made the decision to settle for an indefinite period; his choice falls on the New England college town of Beardsley, where Lolita is attending school for the first time. For her this means a little freedom, for him even more control, suspicion and jealousy - an attitude that ironically makes him a worried but somewhat old-fashioned father in front of the teachers at the girls' school, which sees itself as progressive. Reluctantly, he allows Lolita to rehearse for a play. A violent argument between the two ends with Lolita's flight; when he finds her again, she seems transformed; For her part, she has made a decision: she wants to forego theater and school and go traveling again, on condition that she determines the route. Humbert agrees.

On the way, however, he soon senses that they have a pursuer behind them; he takes turns taking him for a detective, a rival, or a product of his paranoia . When Lolita is in the hospital with a viral infection and Humbert, infected and weakened by her, in the hotel, she takes the opportunity and disappears; The staff informs the “father”, who rages like a fury, that she has been picked up by her “uncle” “as agreed”. Humbert feverishly pursues the trail of the unknown kidnapper (and rival, as he now surely believes) in order to determine his identity, to catch him and kill him and thus to recapture Lolita - in vain.

More than three years later, it is Lolita who - pregnant, married and living in poor conditions - contacts him with a request for money. Humbert disposes of the income from renting the Haze house, which amounts to ten times the desired sum, and gives her what she is entitled to without any conditions. However, his hope of winning Lolita back is not fulfilled. Instead, he learns from her that the great stranger he believed he found in her husband and whom he still seeks to kill was actually a rival and even the only man she was ever "crazy" about; he broke up when she refused to appear in the pornographic films that he had made. After all, Humbert now knows his name and understands the context: the playwright Clare Quilty, an old friend of the Haze family, was the author of the play in Beardsley, the main role of which he designed especially for Lolita and which he based on the hotel “The Enchanted Hunters "Where Humbert spent the first night with her and where he was mysteriously approached by Quilty, as if he could see through him. Humbert is now looking for the final encounter with him, tracks him down and shoots him.

Looking back on a laconic note in the foreword, it turns out that the condition on which Humbert attaches the publication of his notes - Lolita must no longer be alive - is fulfilled: she dies, only a few weeks after him, in childbirth after giving birth with one stillborn girl.

History of origin

Forerunner in Nabokov's work

Certain central themes and motifs, above all the constellation “older man wants child woman”, are already evident in Nabokov's literary works before Lolita .

This is particularly true of The Magician . Written in 1939 in exile in France, it was Nabokov's last major prose work in Russian; it is classified as either a narrative, novella, or short novel. Nabokov found the manuscript, which he believed lost, only after the publication of Lolita and released it for publication in 1959. It was first published in 1986 in the English version under the title The Enchanter (more in the sense of "enchanter" than "magician"). The protagonist is a 40-year-old man who feels drawn to a girl whom he observes in a park for several days (she is, like Lolita, 12 years old, but still looks very childlike); to get closer to her, he gets to know her mother and marries the unattractive, sickly, widowed woman; after her death, his sexual approach to the girl fails in a hotel room and he throws himself in front of a truck.

Much coarser than this “psychological portrait”, the “astute poetic study of sexual obsession” ( Marcel Reich-Ranicki ), the tone in which a minor character in the novel Die Gabe (1934/37) “affects his draft of a story” has an effect real life "- a modification of the" husband / widow / daughter "constellation - presents:" [...] An old dog - but still full of juice, fiery, thirsting for happiness - gets to know a widow, and she has a daughter, still completely girl - you know what I mean - nothing is formed yet, but she already has a way of walking that drives you crazy. [...] "

Another triangular relationship that Nabokov varies in Lolita - "Man / Girl / Rival" - forms the central figure constellation in his novel Laughter in the Dark (1932). The most striking parallel between the two works is the characterological similarity of the men who are not competing on an equal footing: while the protagonists indulge their passion without scruples, their doubles acting in the anonymous darkness act completely unscrupulous and cynical.

Nabokov's poem Lilith , composed in 1928, is focused on an erotic-sexual experience . Taking up certain aspects of their very complex mythology ( Adam's first wife, whom he cast out, mutated in later interpretations into a beautiful young witch who drove men to nocturnal pollutions ), the poem tells of a deceased who thinks he is in paradise and meets Lilith there seductively opens up to him and then suddenly withdraws, so that he experiences the "hell" of coitus interruptus with excruciating ejaculation and public display. Similarly, Humbert describes the abrupt, shameful end of his first love for Annabel Lee, and with reference to Lilith he stylizes his later obsession for nannies in contrast to their adult counter-image: “Humbert was quite capable of sexual intercourse with Eva , but Lilith was after he longed for. "

Emergence

From a letter to his friend Edmund Wilson, it emerges that Nabokov was involved with Lolita as early as 1947 . In the next four years, however, he made difficult progress with writing. Twice he came close to destroying the manuscript. It was also thanks to his wife Véra that this did not happen . From 1951 onwards, Nabokov was able to devote himself seriously to work on Lolita , mainly during the long summer vacation that his university career allowed him. In the final phase, in the fall of 1953, he wrote the novel for up to 15 hours a day. The completion of the manuscript is dated December 6, 1953. - In the years that followed, Nabokov had three more reasons to study the text thoroughly. In 1960 he wrote the screenplay for the first film adaptation , but Stanley Kubrick rejected most of it. In the mid-1960s, Nabokov translated Lolita into his Russian mother tongue, with minor changes to insignificant details. Finally, at the end of the decade, he subjected the text to a thorough revision for the 1970 annotated edition obtained by Alfred Appel Jr. - the first of a modern novel to be published while the author was still alive.

From the aforementioned letter to Wilson and from Nabokov's afterword it emerges that Lolita was not initially conceived as a novel and only gradually grew into one. Nabokov had an improved version of The Wizard in mind; The fact that he had rejected this text was less due to its provocative topic than to the fact that he had not only given the girl no name, but rather little “semblance of reality”. He tried to change this, and so it was logical that the novel, which was initially called "A Kingdom by the Sea", finally bore the name of the heroine as a title. However , Nabokov attributes the “initial shiver of inspiration” for Lolita to an event that preceded the magician without being “directly related” to him. In a newspaper article he had seen a charcoal drawing of a great ape, the first sketch that was "ever produced by an animal"; she showed "the bars of the poor creature's cage".

In the first phase of the creation of his novels, Nabokov collected material like this without knowing what he might use it for; then he subconsciously let the work mature, and only when the “construction” was finished did the actual writing process begin. Nabokov compared this with copying a painting that he saw in his mind's eye "in subdued light" and whose parts he then lit up piece by piece and put together like a puzzle. Lolita was created in this way, not following the later arrangement of the chapters . Nabokov wrote Humbert's diary first, then his first trip with Lolita and then the final killing scene; Humbert's previous story was followed by the “rest” of the plot, more or less chronologically, up to the last meeting between Humbert and Lolita; The final point was the foreword by the fictional editor.

Nabokov's afterword

The reason for the afterword about a book with the title "Lolita" , written in 1956, was the publication of longer excerpts from the novel, realized by the Anchor Review , with the aim of getting the entire work published in the USA. That led to success; however, the epilogue was added to all later editions and, despite minor errors, left unchanged.

Based on the genesis of the novel and his attempts to get it published, Nabokov takes the reactions of publishers, editors and first readers as an opportunity to outline some of his artistic beliefs. There are two main concerns for him: “ Pornography ” - the main accusation against Lolita until then - demands “banality” and “strict adherence to a narrative cliché” and, on the other hand, excludes “artistic originality” and “aesthetic enjoyment”. Lolita does not have “morals in tow” - contrary to the announcement of its fictional editor; He rejects “ didactic prose”; what he demands of literature is that it give him “aesthetic pleasure” and bring him into contact with “other states of being” where “art (curiosity, tenderness, goodness, harmony, passion) is the norm”.

Publication history

First published in France

Immediately after completing the novel, Nabokov tried to get it published. However, the initial feedback, from acquaintances and publishers, was consistently negative. His friend, fellow writer and literary critic Edmund Wilson , thought Lolita was worse than what he had read of him before; Morris Bishop, Nabokov's closest confidante at Cornell University , prophesied that he would be expelled if published. The editors of the publishers Viking Press and Simon & Schuster thought the novel could not be published - the latter even described it as pure pornography . The experiences with three other US publishers were similar. At Doubleday there were advocates among the editors, but the publisher's management categorically rejected the novel.

After the first two refusals in the USA, Nabokov had already reached out to France and contacted an old friend, the translator and literary agent Doussia Ergaz; after the fifth rejection he sent her the manuscript. Two months later she signaled to him that Maurice Girodias , whose small publishing house Olympia Press publishes unusual English-language books, was interested. Nabokov did not know that Girodias specialized in the publication of English-language erotica when the contract was signed on June 6, 1955 and the first edition of Lolita appeared on September 15, 1955 . Nabokov later admitted, however, that he probably would have signed with knowledge of this.

Literary scandal in Great Britain

A chain of coincidences led to the novel published by this obscure French publisher being commented on in US literary columns a few months later. When the English Sunday Times started their traditional poll for the best three books of the year on Christmas 1955, they also chose Graham Greene as one of the celebrities . As he later stated, Lolita was “delighted” and named Nabokov in third place, in contrast to the other respondents without further explanation. The editor-in-chief of the Scottish tabloid Sunday Express , John Gordon, took this as an opportunity for a violent attack, which was probably more aimed at the competition than the novel:

“Hands down the dirtiest book I've ever read. Pure unrestrained pornography. His main character is a perverted guy who has a passion for "nymphettes", as he calls them. […] It is printed in France. Anyone who relocated or sold it in this country would surely end up in the mess. And the Sunday Times would definitely think that's okay. "

Neither the Sunday Times nor Graham Greene responded directly to these attacks. Instead, Greene published a note in the political magazine The Spectator that he had founded a John Gordon Society whose competent censors would protect the British homeland from the insidious threats of pornography in the future. This satirical act led to letters to the editor filling the columns of the Spectator for months and, on February 26, 1956, The New York Times Book Review also reported for the first time about a literary scandal smoldering in Great Britain, without naming the title of the novel or the author. This did not happen until March of the same year, with the result that a broad American readership began to be interested in this novel.

Indirect ban in France

A raid on the premises of Olympia Press resulted in the French Ministry of the Interior banning the sale and export of all 24 titles of the publisher on December 10, 1956. Girodias was able to prove a little later that the Home Office had only acted at the instigation of the British Home Office , and thereby brought the local press on his side.

The worldwide ban that also applied to Lolita was legally questionable; neither a British nor an American court had banned the sale of this novel. The authority responsible in the USA, the American Treasury Department, informed Girodias on February 8, 1957, at his request, that Lolita had been checked and released. This meant that the novel could not be exported from France, but could be imported into the USA. The situation was even more absurd for other Olympia Press titles in France: their English-language editions were banned while they were still available in French. Therefore, while the ban was still in force , Éditions Gallimard prepared a French edition of Lolita , which appeared in April 1959. The ban on English-language titles published by Olympia Press was finally lifted in July 1959.

Publication in the United States

Decisive for the publication of Lolita in the USA was the preprint of longer excerpts from 16 of the 69 chapters by the respected literary magazine Anchor Review in June 1957, flanked by an essay by the Henry James specialist FW Dupee and an afterword by Nabokov, who helped with the selection of the text had contributed. The aim of the “test balloon” was to encourage academic criticism to comment and, on the other hand, to check whether legal objections were to be expected. The result was positive.

The publication was delayed by the fact that Girodias tried to achieve the greatest possible profit for himself. He owned the rights to the English language edition of the novel; he made heavy financial demands in the event that he resigned her, and at times considered relocating Lolita himself in the United States. Nabokov resisted and at the same time was under time pressure. The reason was the US-American copyright law in force at the time, which provided only limited copyright protection for English-language books printed abroad. It either expired when more than 1,500 copies of the book were imported into the United States or five years had passed after it was first published. After a tough struggle, an agreement was finally reached between Nabokov, Olympia Press and the respected New York publisher GP Putnam's Sons , which published Lolita on August 18, 1958.

Just two weeks later, Lolita was on the American bestseller lists; six weeks later the book reached number one, and that position it held for six months. The sales success was correspondingly great. The third edition went to press just a few days after it was first published, making the novel the first since Gone with the Wind , of which more than 100,000 copies were sold within three weeks.

The German-speaking Lolita

The German-language edition of Lolita in autumn 1959 was a novelty in that no fewer than five translators were responsible for it, including two respected writers and the publishing director, Heinrich Maria Ledig-Rowohlt , personally. The result was generally well received, not least by the leading literary critic of the time, Friedrich Sieburg . In the opinion of Dieter E. Zimmer , who has been in charge of the complete edition of Nabokov's works at Rowohlt since 1989 , the common assumption that the translation was a collaborative effort is largely a " myth ". The first version of the elderly but completely inexperienced Helen Hessel was discarded by Ledig-Rowohlt and passed on to Maria Carlsson, who, in contrast to Hessel, was still very young for editing; He checked the result together with Gregor von Rezzori in a 14-day exam in Merano ; According to Carlsson's account, which kept the minutes, this changed little, from which Zimmer concludes that the German Lolita from 1959 is “essentially Maria Carlsson's text”. - As editor of Nabokov's complete works, he subjected this version to two more thorough revisions, in 1989 and 2007; Although he attests to her having “hit the difficult tone between lyricism and cynicism”, on closer examination he found numerous inaccuracies, mainly “cheap language clichés”, which he gradually eradicated. Zimmer is confirmed by Véra Nabokov's unpublished letters to the publisher, in which she criticizes exactly what he himself had noticed.

The Nabokov expert Dieter E. Zimmer points out that, to the best of his knowledge, there was no complaint against Lolita in Germany . Only a few libraries refused to buy it and a few bookstores refused to sell the novel. This was due to a changing sexual morality, which shortly after the German Lolita publication also took account of the case law. Until 1961, the standard for judging whether a work was lewd or not was the moral feeling of the average citizen. It was enough for ordinary people to express their indignation about a work on the witness stand. For publishers this legal practice meant a high economic and personal risk. The work in question could be confiscated, he could be sentenced to a prison term or the novel could no longer be displayed in bookstores. In October 1960, a court in Göttingen convicted the writer Reinhard Döhl for publishing a polemical poetic collage entitled Missa profane , which pointed to the discrepancy between the holy mass and political reality. The verdict contained the following sentence: The criminality of a publication cannot be excused by the fact that it is a work of art. In the summer of 1961, the Federal Court of Justice overturned this judgment and found that not every citizen could decide on the immorality of a representation. The judge could do this and if necessary he would have to have the work explained to him by someone who was artistically open-minded or at least tried to understand .

The Russian-speaking Lolita

The Russian-language Lolita occupies a certain special position, both in development and publication . Nabokov did the translation into his mother tongue himself; she remained his only one. In an afterword written especially for her, he first refers to what he had written to accompany the preprint of 1957 and which was later included in all other editions. There he had followed the confession that Lolita was a kind of "declaration of love" to the English language, the complaint about the loss of his "natural idiom ", the "rich and infinitely docile Russian language", and thus - like him for eight years later stated - aroused hope that his Russian Lolita must be "a hundred times better than the original". He could not meet this expectation; the “story of this translation” is for him the “story of a disappointment”. A completely different question that he then asks himself and the reader is why he even bothered to translate it into Russian, and for whom. Under the given circumstances, he saw little hope of a noteworthy readership, neither among the Russians in exile nor in "Russia" (Nabokov was generally banned in the Soviet Union , and almost 10 years after his death one of his books was in prison ). He also had every reason to fear interference from censorship (even in democracies like Sweden and Denmark, Lolita had appeared grossly distorted). What Nabokov wants to counter is knowing that his “best English book” (a judgment he only ironically weakens) has been translated “correctly” into his mother tongue.

The first edition of the Russian Lolita was published in 1967 by the New York publishing house Phaedra . In the Soviet Union, the novel was published for the first time in 1989 in Izvestia magazine , as part of the "Library of Foreign Literature" series.

Reception history

The anthology Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism , edited and commented on by Christine Clegg in 2000, attempts to bundle almost half a century of reception history. The difficulty of the undertaking is made clear by the quotation of the opening words of another summarizing Nabokov study. In 1982, Norman Page stated that Lolita had shown its many readers very different "faces" and that the reviewers' views were correspondingly varied, depending on the weight they attached to the various elements and how they rated them.

Clegg divides Lolita's reception history into five decades and carefully tries to work out the main lines of development. She indicates a kind of turning point by stating that with the beginning of the 1980s - i.e. immediately after Nabokov's death - the image of the author as an "esthete who was indifferent to humanity" was increasingly critically questioned. This change, as Clegg's account suggests, is primarily due to the contributions by Richard Rorty and Michael Wood and, on the other hand, to those by Ellen Pifer, Linda Kauffman and Elisabeth Bronfen , which at the same time reflects the fact that from this time on Lolita increasingly also from a female point of view (or the feminist ) is received. The questions are new or are formulated more sharply: The focus shifts overall from Humbert to Lolita, most pointedly with Kauffman (“Is there a woman in the text?”); In the judgment of Humbert the critical accents predominate; And finally, it is also checked to what extent one and the other are hindered or promoted by the author.

Clegg does not fail to point out that the foundations for these approaches were laid by the earliest reviewers. In addition to the momentous essay by Lionel Trilling , she particularly highlights the contributions by Kingsley Amis and FW Dupee. She emphasizes that the first reception at the end of the 1950s produced a "variety of intelligent criticism", and explicitly contradicts the presentation by Bryer and Bergin, who in a study from 1967 considered the majority of the works from that period to be worthless, mainly because because in it Nabokov's literary achievement was not as appreciated as it deserved. The Lolita reception moved in precisely this direction in the 1960s. The culmination points were the contributions by Carl Proffer and Alfred Appel Jr., who was ultimately also responsible for the annotated Lolita edition from 1970, which he provided with a detailed annotation apparatus and also introduced with a 50-page essay.

The extensive epilogue by publisher Dieter E. Zimmer in the German-language edition of 2007, which he has revised for the second time , also offers a look back at the history of reception . The starting point is also the statement that Lolita is one of the exemplary examples of a “multi-layered” work. Zimmer adds a multitude of other readings to the interpretations suggested by Norman Page (romance novel, parody , psychological study of obsessive behavior, description of certain aspects of American life, moral or immoral book) and groups them in pairs of opposites ( e.g. erotic / anti- erotic , road novel or its parody) and concludes: " Lolita is a novel that agrees what seems to be mutually exclusive according to common understanding." He then takes up four such antinomies in order to illuminate essential aspects of the reception. One of them - this is the second parallel to Clegg's portrayal - Zimmer alone devotes half of his consideration, to the pair of opposites aestheticistic / moral. The other three of his choices are traditional / modern, serious / weird, and realistic / fantastic.

interpretation

main characters

Humbert

Humbert Humbert, the protagonist and first-person narrator, "is a man with an obsession ", said Nabokov in an interview, and therefore does not differ from many of his other characters who have "violent obsessions, obsessions of the most varied kinds". When asked whether Humbert appears not only “funny” but also “haunting and moving”, he replies elsewhere: “I would put it another way: [He] is a vain and cruel villain who succeeds in creating a ' to make a moving 'impression. "

The picture drawn by Humbert's Lolita criticism does not agree in every respect with Nabokov's, especially not when it comes to whether he appears to the reader as a “villain”. Page Stegner, for example, thinks there are good reasons to be inclined to sympathize with him. Although he is a sexually perverted and murderer, he suffers from his pathological obsession; the persuasiveness and charm that his creator gave him cannot be erased by his crimes; Humbert's longing for something lost goes beyond his first love and is directed towards an ideal state beyond space and time. In contrast to Nabokov, who thinks that the real meaning of the “moving” only fits Lolita, Stegner clearly refers to Humbert when he concludes with the statement that the “moving experience” while reading the novel consists of “compassionate understanding of suffering generated by an idealistic obsession for the unattainable. "

One analysis that confirms Nabokov's picture of Humbert at its core is that of Richard Rorty . Based on the postulate that Nabokov's greatest creations are "obsessive" (in addition to Humbert he names Kinbote from Fahles Feuer and Van Veen from Ada ), Rorty claims that they are people whom Nabokov detested. Rorty explains that they can still appear engaging and moving by the fact that their creator endowed them with an artistry that is on a par with him and with an extraordinary sensitivity towards everything that concerns their obsession. In contrast, they lack any curiosity for anything that lies outside of them. Rorty proves Humbert's "lack of curiosity" ( "incuriosity" ) with several examples from the text and also justifies it on the basis of Nabokov's afterword to Lolita , in which the author links his conception of art to the existence of "curiosity, tenderness, goodness and ecstasy" . Rorty thinks that Nabokov was very well aware that in his definition he encapsulated aesthetic and moral categories and that what belongs together for him can be separated from others, which ultimately means that there can be artists who capable of just as much ecstasy as he is in the absence of elementary moral qualities. Logically, Nabokov created characters - figures like Humbert and Kinbote - who are at the same time ecstatic and cruel, sensitive and hard-hearted. This particular type of “ingenious monster”, a “monster of a lack of curiosity”, according to Rorty, is Nabokov's special contribution to our knowledge of human possibilities.

Lolita

"The only success of the book", judged Kingsley Amis in 1959 in one of the first extensive - and generally negative - reviews, "is the portrait of Lolita herself." The paradoxical question that arises from this (comments editor Christine Clegg) is this how a "real" representation of Lolita could even succeed through Humbert's perspective. In this context, Clegg recalls Alfred Appel's statement that Lolita was one of the “essential realities” of the novel, and adds that most of the critics of his time also judged it that way.

Dieter E. Zimmer resolves the supposed paradox by making it clear that the novel shows two “Lolitas” - more precisely, a “Lolita” and a “Dolores”. “Lolita” is the protagonist's fantasy figure, she is Humbert's subjective projection, the “demon” he believes he is bewitched by, the ideal-typical embodiment of what he imagines as a “nymphette”. The name itself, Lolita, is his invention and it is almost exclusively reserved for him. “Dolores” on the other hand, Dolores Haze, is the girl's real name; Friends and relatives usually call her Dolly or Lo. It is thanks to Nabokov that the reader of Humbert's fantasy figure can very well replace another, "real" figure, according to Zimmer. Her appearance (right down to her exact body measurements), her language, her behavior, her likes and dislikes are described - in any case enough to make critics agree that she is the image of a “typical American teenager of the 1950s “Is recognizable.

This “real” Lolita, continues Zimmer, seemed to some readers all too banal and vulgar and, above all, was thoroughly misunderstood by early European reviewers. As an example, he quotes a reputable German daily newspaper: “Hardly said too brutally: this nymph Lolita is the most naughty, depraved (even in the camping camp she 'did' it with her peers), most corrupt, cunning, filthy little girl who uses the liberal upbringing methods of the newcomers At best, create the world and we and the author can imagine if need be. ”Judgments like these were by no means limited to the phase of first reception. In 1974 Douglas Fowler emphasized Lolita's "vulgarity" and "indifference" - in contrast to Humbert's "sensitivity" and "vulnerability". It is motivated differently when Page Stegner and Michael Wood speak almost identically of Lolita's “ordinaryness”; It is Stegner's intention to highlight the discrepancy between “real” and fantasy figures; Wood is concerned with gauging the extent of the destruction: In the end it becomes clear that even Lolita's "ordinary" has been ruined.

It took more than two decades before the view of the novel as a whole and of the protagonist in particular began to fundamentally change in the 1980s: the focus shifted from the question of what is happening in Lolita to what is happening to Lolita. Judgments like those of Fowler, who attested Lolita “vulgarity” and “indifference”, now appear, reinterpreted, in a completely different light. Ellen Pifer, for example, sees Lolita's “bad manners” and “youthful clichés” as a defense strategy with which she attacks Humbert's “good taste” on the one hand and tries to preserve her personal integrity on the other. Finally, from a decidedly feminist position, Linda Kauffman works specifically on her male critic colleagues, above all Lionel Trilling and Alfred Appel. Trilling's thesis that Lolita is not about sex, but about love, she counters with: " Lolita is not about love, but about incest , which means betrayal of trust and the rape of love." She later continues this thought with a quote by Judith Lewis Herman : "Father-daughter incest is a relationship of prostitution " - a thesis that the novel confirms not only in a moral sense, but also in a material sense, as Humbert pays Lolita for her servitude.

Nabokov's wife Véra , always the first reader of his works and, in his eyes, also the best, notes in her diary that she would like “someone to share the delicate description of the child's helplessness, his moving dependence on the monstrous HH and his heartbreaking courage took note, culminating in the miserable but essentially clean and healthy marriage, and in her letter, and her dog. And the terrible look on her face when HH deprives her of a promised little joy. They all ignore the fact that 'the nasty little brat' Lolita is a good child in the end - otherwise she would not have got up again after being so badly trampled and found a decent life with poor Dick, that she was a thousand times better than the previous one. "

However, neither Véra Nabokov nor her husband could prevent the protagonist from developing her own life in the public consciousness soon after the novel was published and practically becoming a third figure - the "Pop Lolita". Apart from her age, she has little in common with the “Real” figure “Dolores”; with Humbert's fantasy figure only so much that she, the "Pop-Lolita", is reduced to what the man wants: the child woman as a seductress. What the novel does - to expose this as a male projection - makes the trivial myth of "Pop-Lolita" disappear.

Key scenes

In her interpretation of the "masturbation scene" on the Hase sofa, Elisabeth Bronfen takes up two thoughts of Humbert: on the one hand, his conviction that he had "safely kept Lolita in a solipsistic manner" during this time , and on the other hand, his subsequent realization that it was not the real girl, but his "own creation, another, a fantasy Lolita" that he had "madly possessed". From this she concludes that by conceiving and taking possession of Lolita's body as an image, Humbert becomes blind to the fact that her real body is there; by believing that he has only touched an image and not a body, he is not only raping a body, but ignoring that rape took place in the first place. Linda Kauffman sarcastically comments on the fading out of the female perspective in this scene: “Both come at the same time - provided the reader is male.” Rachel Bowlby, on the other hand, thinks that the female perspective is clearly recognizable; Just as with Humbert, “Fantasies” also played a role in Lolita: He imagines the nymphette he has poetically exaggerated, and she imagines the movie heroes resembling Humbert, whose picture she pinned over her bed.

Unlike the girl of the same age but still very unsuspecting in Nabokov's The Magician , Lolita does not react in horror when she realizes that she is lying in bed with her stepfather in the hotel “The Enchanted Hunters”. On the contrary, she even initiates the first sexual intercourse with him. Quite a few readers have therefore willingly followed Humbert's statement “It was she who seduced me”. The text clearly shows that this is only externally a "consensual" sexual act. The thoughts with which Humbert accompanies Lolita's “energetic, objective” efforts make it clear that he is aware from the outset of the discrepancies that exist between the experiences and expectations of both. For Lolita, sex is a "summer camp game forbidden by boring adults", GM Hyde states, but on the other hand it is also free of the thoughts of "sin and guilt" with which it is associated for the " puritanical , educated" Humbert; instead of the gate to “freedom” opening for him, from now on he is caught in his “gloomy lust”. Some critics see in this that Lolita has already lost her “innocence” and that Humbert “anticipates”, clues that exonerate him morally. FW Dupee counters this by saying that Lolita's “delicate sham agreement” only makes Humbert's guilt even deeper and more complicated than if it had been “unequivocally rape”.

In an interview, Nabokov describes his protagonist as a “screwed-up poet” - an attribution that Dieter E. Zimmer takes up with a look at the scene in which Humbert meets the pregnant, married Lolita again: there he stops being a “screwed-up poet” , from then on he goes through a "deep change". Not all critics see it that way. Some are disturbed by the tone in which Humbert speaks of repentance. Dupee, for example, thinks he sounds a bit “fake”. Trilling also thinks it is “less successful”, but sees the logic of the plot preserved in that Humbert's desire to marry Lolita fails; With a view to his own thesis that the novel is about “love out of passion” - the opposite of marriage - this is only logical. One of the most thorough analyzes of the re-encounter scene comes from Michael Wood. A large part of it belongs to dealing with fellow critics. David Rampton was of the opinion that the scene draws its strength from the fact that Lolita's character had gained depth and complexity; Wood, on the other hand, thinks that its effect is based precisely on the fact that a Lolita is shown that has even lost its original "ordinary". The common thesis that Humbert's remorseful statements towards the end of the novel set a completely new tone is refuted by Wood using examples from the text and concludes that feelings of guilt were always present in him, but could only penetrate them selectively because they were caused by constant desire and fear were suppressed. What worries Wood most, however, is whether Humbert repents at all. Ultimately, he decides to say no. What moves Humbert sounds more like transfiguration and romanticization. So it's more about nostalgia than remorse. Real repentance, Wood continues, is also a sign of greatness. Nabokov didn't want to do that. Instead, he created a character like the one found in Flaubert and Joyce , one whose “unfortunate lack of size” may move the reader more than the “great tragedy” of some other characters.

Structure and style

Humbert, the narrator, an educated literary scholar, describes, on the one hand, as a European outsider, partly fascinated, partly disgusted, detailed the American everyday and youth culture; on the other hand, he peppered his report with multilayered literary allusions, puns and jokes, whereby the readers are also led on the ice that they often do not know whether it is a deliberate ambiguity of Humbert or the editor John Ray Jr. or the author Nabokov .

This network of relationships is made even more complicated by the fact that references are not only made within one language - the native Russian Nabokov wrote the novel in English - but that a dense, criss-crossed network of meanings is spun from Russian, French, German and other languages . Some of this is inevitably lost in the translation. For example, according to Nabokov, the name "Humbert Humbert" refers to an unpleasant person due to its unpleasant double sound, but is also a royal name, reminiscent of the English word "humble" (humble or humble), of the Spanish "hombre" (man ), the French “ombre” (shadow) - which is reinforced by the duplication - and a card game of the same name, to name just a few possibilities. Nabokov chose the pseudonym because it was "a particularly bad-sounding name". The last name Lolita has towards the end of the novel, "Dolores Schiller", could be understood as an allusion to the shimmering character of this character - or it can be read in English phonetically as the homophone of English "Dolores 'killer" ("Dolores' murderer." "), Because Dolores dies of the consequences of the birth of the child that her husband Dick Schiller (" Dick 's [the] killer ", dt." The' tail 'is a murderer "or" murderer of masculinity "; ever according to the degree of phonetic blending) with her.

The ambiguity and ambiguity of the novel is heightened at the end by the fact that Humbert is an unreliable narrator : the purpose of his text is not the truthful presentation, but an apology of his deeds. He says that he was seduced by Lolita on their first night of love, but in the further course of the story he mentions that Lolita cried during and after every sexual act, and finally accuses himself of raping herself hundreds of times . In Lolita's secret helper in her escape, he also finds a strong opponent who is at least equal in literary knowledge and always one step ahead; at times, Lolita's savior seems to be Humbert's own alter ego . The murder sequence at the end, which takes place in a dreamlike atmosphere, also raises the question of whether the author is describing an imagined reality or just a nightmarish imagination of the main character who finally frees itself from its "dark side" through a fictional murder (Lolita's savior is not less pedophile than Humbert himself). The game of hide and seek only ends with the last point and leaves many questions unanswered.

The novel is pervaded by numerous literary quotations, half-quotations and allusions. The two most important references are a series of works by Edgar Allan Poe : Humbert refers to his poem Annabel Lee when he mentions “a princedom at the sea” when he remembers his first childhood love. In addition, her name is Annabel Lee, just like Poe's. He married his 13-year-old cousin Virginia Clemm in 1836; the poem may allude to her early death. Nabokov also refers to the novel The Adventures of Arthur Gordon Pym , the story William Wilson and many others, as well as the novel Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll , whose main character, a little girl, as well as its ambiguities, dream worlds and allusion patterns in numerous, often travested figures appear. There are also quotations from the French original edition of the novella Carmen by Prosper Mérimée . Humbert Humbert repeatedly refers to Lolita as Carmen, especially towards the end of the story. The prison motif is also consistent: All the people involved are portrayed directly or metaphorically as prisoners.

Donald E. Morton draws attention to the complex symmetrical relationships that structure the novel: in addition to the strangely duplicated name of Humbert, this is evident in the two roles in which he appears in the book: as the protagonist who experiences the story and as the narrator who reflective looks back on them. In addition, it is reflected by the figure of the equally pedophile Quilty. There are also duplications in the two parts of the novel, in the number 342, the Lolitas house number in Ramsdale and the room number in the motel The Enchanted Hunters is; the house in Ramsdale is strikingly similar to that in Beardsley, there are two trips together, and finally a foreword and an afterword frame the novel. In the preface, the fictitious editor refers to the “ ethical appeal” that the book makes “to the responsible reader”. In the afterword, Nabokov denies this reading: Lolita has “no morals in tow”. According to Donald E. Morton, this highly artistic game with dualisms helps ensure that when the novel is over, “both the reader and Humbert have had their pleasure”.

Romance novel

The American literary critic Lionel Trilling interpreted Lolita as a romance novel in a highly acclaimed essay published in 1958 . He starts from the thesis that in a classic love story the meeting of the two lovers is disturbed, if not impossible. In modern permissive society, however, there are no class barriers, no more parental prohibitions, and the fact that one of the two is otherwise married is no longer a real obstacle. Therefore, Nabokov had to describe a perverted love, a love that is against violates the social taboo of pedophilia. Trilling finds evidence for his thesis in numerous allusions to the minne tradition of the Middle Ages and early humanist love poetry: Both Dante and Petrarch sang about passionate love affairs with underage girls, and Lolita remains, just like in courtly minnie poetry, "always the cruel lover [... ] even after her lover has physically possessed her ”. Humbert's plea at the end of the novel, when Lolita had already outgrown the nymphet age, that she should live with him, show his true love. In this respect he is "the last lover".

palimpsest

Dieter E. Zimmer contradicts Trilling's interpretation, which he accuses of having fallen for Humbert's apology, with which he wanted to get the reader or the jury to his side. Rather, Nabokov wrote the novel as a palimpsest , as a double-written sheet. The reader is expected to recognize both levels of the text; superficially one reads Humbert's dazzling rhetoric, which invites sympathy with him, but underneath it is important to recognize his monstrosity and lovelessness, which the author lets shine through again and again. Love is tied to three minimum conditions: it is directed to a certain person and not just to a certain type; she does not want to harm the love object; and the love object must at least have the chance to consent to the love relationship. However, all three conditions are not met in Humbert's case. He does not want the person Dolores Haze, but the ideal type of nymph, which Lolita embodies for him; he consciously harms her by systematically preventing her from contact with her peers. Towards the end of the novel, he is increasingly aware that he has stolen her childhood. But only Humbert the narrator feels remorse about it, never Humbert the experiencer. After all, he was not interested in reciprocating his feelings, all he wanted was sex. Their needs - for friendship with other children, for comic books, magazines and sweets - he disturbs, he ignores or he makes fun of them. The tender feelings that he sometimes feels for her immediately turn into sexual desire again, and he rapes her again: Zimmer sums up:

"Something that could and would like to be love destroys what is loved and itself. Amusing to read, Lolita confronts us with the tragic possibility that love and sex can be mutually exclusive."

Possible role models and inspirations

Heinz von Lichberg's novella Lolita from 1916

The literary scholar Michael Maar tried to prove in 2004, Nabokov was on the short story Lolita the forgotten German author Heinz von Lichberg (published in the short story collection 1916 The Cursed Gioconda been) stimulated. This thesis was taken up with interest by the press and turned into an accusation of plagiarism . Lichberg's story has little in common with Nabokov's novel, apart from the eponymous name of the main character: It is a horror story in which a man falls in love with a Spanish woman who is portrayed as young but not prepubescent; the family is under a curse that causes all women to die with the birth of a daughter, including Lolia's mother. The narrator then escapes from the relationship and Lolita dies. Stylistically, too, the differences between Lichberg's simple fable and Nabokov's allusive and cleverly constructed novel predominate. It is possible that Nabokov, who lived in Berlin from 1920 to 1937, knew Lichberg or his novella, but there is no further evidence for this, especially since Nabokov could not read German fluently and therefore did not receive the original German literature of his time . Dieter E. Zimmer comes to the conclusion that one can only observe from this parallel “how urban legends arise”.

The Sally Horner case

Lolita, or parts of it, likely pick up on an actual case of child abuse , the kidnapping of a twelve-year-old girl named Florence Sally Horner by a 52-year-old unemployed mechanic, Frank La Salle, in 1948. He had seen Sally give her a five cent as a test of courage stole expensive notepad. He posed as an FBI agent to her and made her come with him. He drove her all over the US for 21 months and abused her regularly. When he was arrested, La Salle claimed he was Sally's father; just two weeks later he was sentenced to 35 years in prison. Sally Horner died in a car accident in 1952. The case shows parallels to the second part of Lolita . Nabokov's notes also show that he was known to him. In addition, Humbert alludes to it several times in his novel. Still, the press releases about the case may not have been the first inspiration for Lolita, as Nabokov had already started writing the novel when it was first published and the oldest traces of the story, Lilith and The Sorcerers , are both significantly older.

Classic role models

Several classics of world literature that Nabokov held in high esteem, such as Pushkin's Eugene Onegin , Tolstoy's Anna Karenina and Flaubert's Madame Bovary , show certain similarities in the constellation of the characters. 120 years after Onegin, 100 years after Madame Bovary and 80 years after Anna Karenina, love also fails in Nabokov's Lolita. This time, however, it is not the protagonist who is seduced, but Humbert Humbert, with which Nabokov reverses the model of the classic seduction novel.

Emma and Anna, Lolita's famous predecessors, are adulterers - Emma does not commit suicide out of lovesickness, but because she is heavily in debt, is threatened with seizure, because she can no longer find anyone to lend her money, and out of general disappointment; Anna is shattered by the brief happiness of the great emotions when she breaks out of the confines of the marital harbor, in contrast to the harsh truth of social norms. Lolita, on the other hand, escapes from a stormy love affair into the port of marriage, more or less into shallow waters, but she seems to be moored there. In these works, love turns out to be an insidious delusion, which in Lolita drives the self-deceiving man to murder. Lolita's state of mind remains opaque in its depth until the end. This shows the strongest parallels to Pushkin's Tatiana, who ultimately also distrusts love.

Film adaptations and adaptations

The novel was filmed twice:

- 1962 - Lolita by Stanley Kubrick , with James Mason as Humbert Humbert, Shelley Winters as Charlotte Haze, Sue Lyon as Lolita and Peter Sellers as Clare Quilty.

- 1997 - Lolita by Adrian Lyne , with Jeremy Irons as Humbert Humbert, Melanie Griffith as Charlotte Haze, Dominique Swain as Lolita ( Natalie Portman had not accepted the role because she was afraid that after her role as Mathilda in the film Léon - The Professional for Last being committed to the childlike seductress) and Frank Langella as Clare Quilty.

In 1998 the work was also released as a radio play , produced by Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR), in the leading roles with Ulrich Matthes , Natalie Spinell and Leslie Malton . In 2005 an audiobook read in by Jeremy Irons was published .

Since March 2003, a theater adaptation by Oliver Reese has been performed as a one-man play at the Deutsches Theater in Berlin with Ingo Hülsmann in the role of Humbert Humbert.

The English new wave band The Police processed the Lolita theme in their 1980 song Don't Stand So Close to Me and referred to Nabokov in a line of text. The song Lolita by Lana del Rey refers to the book.

Opera by Rodion Shchedrin

The Russian composer Rodion Shchedrin created an opera from Nabokov's novel, for which he wrote the libretto himself. The world premiere took place on December 14, 1994 at the Kungliga Operan, Stockholm . Mstislav Rostropovich was the musical director .

Lolita complex

As Lolita complex (also Nymphophilie of nymph and philia ) is called strong erotic or sexual desire of men from middle age to girls or young women.

See also

Book editions

- English

- Lolita . Novel. Afterword by Craig Raine . Penguin, London 1995, ISBN 0-14-118253-9 (text without comment).

- Alfred Appel (Ed.): The annotated Lolita. Penguin, London 2000, ISBN 0-14-118504-X .

- Friederike Poziemski (ed.): Lolita . Novel. Reclam, Stuttgart 2013, ISBN 978-3-15-019833-9 (= Reclams Universal Library , Volume 19833).

- German

-

Lolita. Novel. From the American by Helen Hessel with Maria Carlsson , Gregor von Rezzori , Kurt Kusenberg and HM Ledig-Rowohlt . Rowohlt, Reinbek 1959.

- New edition as paperback, edited by Dieter E. Zimmer . Rowohlt, Reinbek 2008, ISBN 978-3-499-22543-7 .

literature

German speaking

- Gregory von Rezzori : A Stranger in Lolitaland - Stranger in Lolitaland. An essay. From the American. trans. and with an afterword by Uwe Friesel . Edited by Gerhard Köpf , Heinz Schumacher and Tilman Spengler . Berliner Taschenbuch Verlag, Berlin 2006, ISBN 978-3-8333-0364-7 (German and English; travel report about the locations of Nabokov's Lolita ).

- Dieter E. Zimmer : Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel. Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-498-07666-5 .

- Azar Nafisi : Reading Lolita in Tehran. Goldmann TB, 2008, ISBN 978-3-442-15482-1 .

English speaking

- Kingsley Amis : [Review] . The Spectator , London, November 6, 1959, pp. 635-636.

- Alfred Appel, Jr .: Lolita: The Springboard of Parody. In: Nabokov: The Man and His Work. (Ed. LS Dembo). Madison, Wisconsin 1967, pp. 106-143.

- Alfred Appel, Jr. (Ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: The Annotated Lolita. McGraw-Hill, New York 1970 and 1991.

- Elisabeth Bronfen : Over Her Dead Body: Death, Femininity and the Aesthetic. Manchester University Press , Manchester 1992, pp. 371-381.

- Christine Clegg (Ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000.

- FW Dupee: A Preface to "Lolita". Anchor Review, New York, June 2, 1957, pp. 1-13.

- Linda Kauffman: Framing Lolita: Is There a Woman in the Text? In: Yaeger and Kowalewski-Wallace 1989, pp. 131-152.

- Norman Page (Ed.): Nabokov: The Critical Heritage. Routledge , London 1982.

- Ellen Pifer: Nabokov an the Novel. Harvard University Press , Cambridge 1980.

- Carl Proffer: Keys to "Lolita". Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1968.

- Richard Rorty : Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge University Press , Cambridge 1989, pp. 41-68.

- Lionel Trilling : The Last Lover: Vladimir Nabokov's "Lolita". Encounter , London, November 1958, pp. 9-19.

- Graham Vickers: Chasing Lolita: How Popular Culture Corrupted Nabokov's Little Girl All Over Again. Chicago Review Press, 2008, ISBN 978-1-556-52682-4 .

- Michael Wood: The Language of "Lolita". In: The Magician's Doubts: Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction. Chatto, London 1994.

Radio plays

- Lolita. Radio play. Radio play editing and director: Walter Adler . 2 CDs. Der Hörverlag, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-86717-087-1 ( WDR production , 1998).

Audio books

- 2005: Lolita (read by Jeremy Irons ), Random House Audio , ISBN 978-0739322062

Web links

- Reviews and links to the Roman (English)

- Glossary of the novel ( Memento of February 3, 2007 in the Internet Archive ) (English)

- Article about Lolita on zembla (English)

- Herbert Huber: About Heinz von Lichberg's story Lolita

- Chronology Compiled by Dieter E. Zimmer (English)

- Lolita as a travel novel The routes of Lolita and Humbert on both journeys (1947/48 and 1949), with maps and around 100 illustrations (English)

- Lolita, nymph . In: Der Spiegel . No. 12 , 1959, pp. 60-64 ( Online - Mar. 18, 1959 ).

- Dieter E. Zimmer, interview with Andrea Schmittmann: “A story of insincerity”. About unreliability as a translation problem in "Lolita", in ReLÜ , Review Journal , No. 15, March 16, 2014 (also about the early translations and the publisher's reasons for sticking to them)

Footnotes

- ↑ a b Timeline for the creation of the novel. In: Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 706

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: The Magician . Translator's note. Book guild Gutenberg, Frankfurt am Main 1989, p. 117

- ↑ Marcel Reich-Ranicki: Vladimir Nabokov - essays. Ammann Verlag & Co, Zurich 1995 ( ISBN 3-250-10277-6 ), p. 66

- ↑ Timeline for the creation of the novel. In: Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, pp. 705–706.

- ↑ Timeline for the creation of the novel. In: Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 704

- ↑ Timeline for the creation of the novel. In: Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, pp. 703–704

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 31

- ↑ a b Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, p. 16

- ↑ Timeline for the creation of the novel. In: Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 709

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A reader's guide to essential criticism. Edited by Christine Clegg. Icon Books, Cambridge 2000, p. 66

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: The annotated Lolita. Vintage Books, New York 1991, Introduction p. XXXVIII. Original quote "semblance of reality" (own translation)

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: About a book called "Lolita". In: Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 514

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: Interview with the BBC 1962. In: Vladimir Nabokov: Clear words. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1993, pp. 37/38

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: Interview with the Playboy 1963. In: Vladimir Nabokov: Clear words. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1993, pp. 58/59

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: The annotated Lolita. Vintage Books, New York 1991, Introduction p. XXXIX

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: About a book called "Lolita". In: Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 517

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: About a book called "Lolita". In: Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 520

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, p. 16.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, p. 17.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, p. 17 and p. 18.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, p. 18.

- ↑ quoted from Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, p. 19.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, p. 20.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, p. 21.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, p. 21 and p. 22.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, p. 22 and p. 23.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, p. 24.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, pp. 28–29.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, p. 25 - p. 28.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 2008, p. 11.

- ↑ Steve King: Hurricane Lolita . barnesandnoble.com. Archived from the original on August 29, 2011. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, pp. 181–195.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, p. 41.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, p. 219 ff.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, p. 41.

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: About a book called "Lolita". In: Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 524.

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: Epilogue to the Russian edition. In: Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 527.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 2008, p. 12.

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Editor's Afterword. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 548.

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: About a book called "Lolita". In: Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 532.

- ↑ a b Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 16

- ↑ Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, pp. 90-91.

- ↑ Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, pp. 91-144

- ↑ Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 39

- ↑ Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, pp. 16-17

- ↑ Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, pp. 40-66

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Editor's Afterword. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 562

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Editor's Afterword. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 563

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Editor's Afterword. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, pp. 563-580

- ↑ Interview with Vladimir Nabokov in the BBC (1962). In: Vladimir Nabokov: Clear words. Interviews - letters to the editor - essays. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1993, p. 36.

- ↑ a b Interview with Vladimir Nabokov in The Paris Review (1967). In: Vladimir Nabokov: Clear words. Interviews - letters to the editor - essays. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 1993, p. 150.

- ^ Page Stegner: Escape into Aesthetics. The Art of Vladimir Nabokov. Dual, New York 1966. In: Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, pp. 44-45.

- ↑ a b Page Stegner: Escape into Aesthetics. The Art of Vladimir Nabokov. Dual, New York 1966. In: Christine Clegg (Ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 49.

- ^ Richard Rorty : Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge University Press , Cambridge 1989. In: Christine Clegg (Ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 97.

- ↑ Own translation of the original ( "curiosity, tenderness, kindness, and ecstasy" ), deviating from that of the German Rowohlt edition ("curiosity, tenderness, goodness, harmony, passion"). Vladimir Nabokov: About a book called “Lolita”. In: Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 520.

- ^ Richard Rorty : Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity. Cambridge University Press , Cambridge 1989. In: Christine Clegg (Ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, pp. 98-99.

- ↑ Kingsley Amis : Review of 'Lolita' by Vladimir Nabokov. Spectator , November 1959. In: Christine Clegg (Ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 36

- ↑ a b Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 37

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, pp. 80–81

- ↑ Süddeutsche Zeitung on March 3rd / 4th. October 1959. In: Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, p. 81

- ^ Douglas Fowler: Reading Nabokov. Cornell University Press , Ithaca 1974. In: Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, pp. 85-86

- ↑ Michael Wood: The Magician's Doubts: Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction. Chatto, London 1994. In: Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 120

- ↑ a b Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 27

- ↑ Ellen Pifer: Nabokov and the Novel. Harvard University Press , Cambridge 1980. In: Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 95

- ↑ Linda Kauffman: Framing Lolita: Is There a Woman in the Text? Yaeger and Kowalewski-Wallace 1989. In: Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 105

- ↑ Linda Kauffman: Framing Lolita: Is There a Woman in the Text? Yaeger and Kowalewski-Wallace 1989. In: Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 112

- ↑ Stacy Schiff: Véra - A life with Vladimir Nabokov . Rowohlt Taschenbuchverlag, ISBN 978-3499229916 , p. 339

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Editor's Afterword. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, pp. 555–556

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 97.

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 101.

- ^ Elisabeth Bronfen: Over Her Dead Body: Death, Femininity and the Aesthetic. Manchester University Press , Manchester 1992. In: Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 135.

- ↑ Linda Kauffman: Framing Lolita: Is There a Woman in the Text? Yaeger and Kowalewski-Wallace 1989. In: Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 108.

- ^ Rachel Bowlby: Shopping with Freud. Routledge , London 1993. In: Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 133.

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 217.

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 219.

- ^ GM Hyde: Vladimir Nabokov: American Russian Novellist. Marian Boyars, London 1977. In: Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 79.

- ^ Lionel Trilling: The Last Lover: Vladimir Nabokov's 'Lolita'. Griffin, August 1958. In: Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 20.

- ^ Douglas Fowler: Reading Nabokov. Cornell University Press , Ithaca 1974. In: Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 84.

- ^ FW Dupee: 'Lolita' in America. Encounter February 1959. In: Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 29.

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Editor's Afterword. Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2007, p. 575.

- ^ FW Dupee: 'Lolita' in America. Encounter February 1959. In: Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 31.

- ^ Lionel Trilling: The Last Lover: Vladimir Nabokov's 'Lolita'. Griffin, August 1958. In: Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, p. 26.

- ↑ Michael Wood: The Magician's Doubts: Nabokov and the Risks of Fiction. Chatto, London 1994. In: Christine Clegg (ed.): Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita. A Reader's Guide to Essential Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke 2000, pp. 120-125.

- ^ Dieter E. Zimmer : Lolita. In: Kindlers Literature Lexicon . Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1986, Vol. 7, p. 5793.

- ↑ On the pedophilia of the fictional character Humbert Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, pp. 126–143.

- ^ Dale E. Peterson: Nabokov and the Poe-etics of Composition . In: The Slavic and East European Journal 33, No. 1 (1989), p. 95 f.

- ^ Dieter E. Zimmer: Lolita. In: Kindlers Literature Lexicon . Deutscher Taschenbuch Verlag, Munich 1986, Vol. 7, p. 5793

- ↑ Vladimir Nabokov: Lolita . Rowohlt, Reinbek near Hamburg 1959, p. 8

- ^ Donald E. Morton: Vladimir Nabokov with self-testimonials and picture documents . rororo Bildmonographien, Reinbek: Rowohlt, 2001, pp. 73–77 (here the quote)

- ↑ Marcel Reich-Ranicki: Vladimir Nabokov - essays. Ammann Verlag & Co, Zurich 1995, ISBN 3-250-10277-6 , p. 68

- ^ Lionel Trilling: The Last Lover. Vladimir Nabokov's "Lolita". In: Encounter. 11 (1958), pp. 9-19, the reference p. 17; quoted from Donald E. Morton: Vladimir Nabokov with self-testimonies and photo documents . rororo picture monographs, Reinbek: Rowohlt, 2001, p. 66

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, p. 64 ff.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel . Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, pp. 49–56 (here the quote)

- ↑ Michael Maar: Biography: The man who invented "Lolita" . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. March 25, 2004; same: Lolita's Spanish girlfriend . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. April 28, 2004; the same: Lolita and the German lieutenant. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main 2005.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, pp. 108–119, the quotation p. 110.

- ↑ Dieter E. Zimmer: Cyclone Lolita. Information on an epoch-making novel. Rowohlt, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2008, pp. 120–125.

- ^ Lionel Trilling : The Last Lover: Vladimir Nabokov's "Lolita". In: Encounter . 11, 1958, pp. 9-19. Also in: Harold Bloom (Ed.): Vladimir Nabokov's Lolita: Modern Critical Interpretations. Chelsea House, New York 1987, pp. 5-12

- ↑ Priscilla Meyer: Nabokov's Lolita and Pushkin's Onegin: McAdam, McEve, and McFate. In: George Gibian & Stephen Jan Parker (eds.): The Achievements of Vladimir Nabokov. Center for International Studies (Committee on Soviet Studies, Cornell University), Ithaca 1984, pp. 179-211.

- ↑ James L. Dickerson: Natalie Portman: Queen of Hearts. ECW Press, 2002, ISBN 978-1-550-22492-4 . P. 119

- ^ Deutsches Theater Berlin on theater adaptation ( memento from September 27, 2007 in the Internet Archive )

- ^ Andrew Bennett, Nicholas Royle : An Introduction to Literature, Criticism and Theory. Prentice Hall Europe, 1999, ISBN 0-13-010914-2 , p. 64.