Moesia inferior

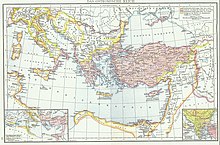

Moesia inferior ("Lower Moesia ") was a province of the Roman Empire on the eastern Balkan peninsula in antiquity . It extended for several hundred kilometers in a west-east direction on the southern bank of the lower Danube (Danuvius) . The area was named after the local Thracian tribe of the Moesi . During its greatest expansion, Lower Moesia included the Bulgarian Danube Plain and the Dobruja .

Pre-Roman population

There was much speculation and mythologization about the origin and nature of the pre-Christian population living in the area of the later province from the area of the national and national communist movements of the 19th and 20th centuries. The representatives, who had dominated for decades, turned the Geto-Dacians, who also lived here, into the real heralds of the Latin language, which the Romans only spoke as a mutilated imitation, as well as the carriers of a pre-form of Christianity . In the reports of ancient authors such as the historian Strabo , who lived around the birth of Christ , the boundaries between the territories of the Getes and Thracians are described. It is also Strabo who writes that the Greeks saw the Getes as Thracians just like the Mysers, who - according to Strabo - are now called Moesi. The Myser are historically difficult to classify. The better-known branch living in Asia Minor is sometimes viewed as an emigrated group, while the historian Herodotus (490 / 480–424 BC) wrote of a campaign by the Myser and Teukrians to Europe in which they defeated the Thracians before the Trojan War subjugated. In his opinion, the Mysers were descendants of the Lydians .

1st to 3rd century

Conquest, foundation of the province

In 29 BC The region of Moesia (Mösia) was conquered by Marcus Licinius Crassus and converted into a Roman province as early as 4 AD. The aim of this initially purely military organizational structure was primarily an effective control of the Danube border. Since the reign of Emperor Tiberius (14–37 AD), the name Moesi expanded in meaning and gradually became the name of all provincial residents. In 44 AD the province was formally raised to a new level after the dissolution of the military command and brought under the leadership of a consular legate .

Under Vespasian a Danube fleet was set up, the Classis Flavia Moesica , which had bases in Lower Moesia in Noviodunum ad Istrum ( Isaccea ), Barboși and at Aegyssus ( Tulcea ).

Dacian wars and division of the provinces

In the winter of 85/86 strong units of the new Dacian king Decebalus broke in , pillaging and plundering across the lower Danube. Completely surprised, the Roman troops were overrun, the governor Gaius Oppius Sabinus was killed. In the spring of 86 the Praetorian Prefect Cornelius Fuscus had received the military high command to repel the attackers. He succeeded in throwing the enemy back across the Danube. The then ruling Emperor Domitian (81–96) rejected an offer of peace by Decebalus and had Cornelius Fuscus prepare a counterattack for the year 87.

Probably in autumn 86 Moesia seems to have been divided into the two provinces Moesia superior (Upper Moesia ) and Moesia inferior . The border river was the Cebrus (Cibrica). The first governor of Lower Moesia was Marcus Cornelius Nigrinus Curiatius Maternus , who was initially appointed as a legate of the undivided province. The capital of the new province was Marcianopolis , today west of Varna .

Until the province of Dacia (Dakia) was surrendered in the second half of the 3rd century, Lower Moesia was bordered by Upper Moesia in the west. The southern border was dominated by the sickle-shaped Balkan Mountains (Haemus mons) running from northwest to east , the foothills of which extend to the Danube. The border with Thracia ( Trakien ) ran on the mountain ranges of the Balkan Mountains . In the north, the Danube formed the natural end of Lower Moesia and, in large parts, the southern edge of Dacia. The vast estuary of the Danube closed the province in the northeastern part. Adjoining this was the Pontus Euxinus ( Black Sea ) in the east - another natural border.

During the ongoing Dacian wars , which can be seen as a cause for the division of the provinces, the adjoining Roman possessions along the Danube became large deployment and supply points. In the spring of 101 Trajan began a large-scale war against the Dacians under Decebalus. The advance was rather slow, as the Romans gradually expanded the infrastructure in the conquered area and secured it with military stations. While they were carrying out a pincer attack against the Dacian heartlands, the Dacians, together with the allied Sarmatian Roxolans and the Germanic Boers , carried out a relief attack against Lower Moesia in autumn 101. The province, exposed by the troops marched north, was almost defenseless to the attackers. In a great battle near Adamklissi in Dobruja, the Roman opponents were defeated and withdrew across the Danube. In 108/109 the Tropaeum Traiani was built here , a monument to the victory of Trajan over the Dacians and their allies. With the end of the war and the establishment of the province of Dacia north of the Mösian borders, the military focus shifted.

Border security in the 2nd century

During the subsequent reign of Emperor Hadrians (117-138), the previous Roman expansion efforts largely came to an end. Instead, the Romans began to stabilize and militarily strengthen the imperial borders. At the beginning of this phase, the Roxolanen and Jazygen advanced again to Dacia and Lower Moesia, but could be repulsed. In the period that followed, the province became quieter. The two Moesia were demilitarized under Hadrian and the subsequent Emperor Antoninus Pius (138-161) and instead Dacia was secured with a dense chain of military installations and border fortifications. As the base of operations for three legions, Lower Moselle remained an important factor in the rear border defense system. During the reigns of the Antonines and Severers that followed, the Lower Danube provinces were characterized by economic prosperity and an intense cultural life.

The legionary bases securing the land were all founded along the Danube Limes and were occupied for centuries:

- possibly as early as the late period of Emperor Augustus (30 BC – 14 AD): Oescus ( Gigen ) as the westernmost legionary garrison;

- since Emperor Claudius (41–54): Novae in the western section, today Swishtow ;

- since Emperor Trajan (98–117): Durostorum in the eastern section, today Silistra , and also

- since Emperor Trajan: Troesmis (Iglitza near Galatz ) in the northern section.

Invasion of the Dacians, Sarmatians and Teutons

In the years 193/196 the Roxolans and other Sarmatian allies crossed the Danube again and broke into Lower Moesia with fire. In 195 the Goths stood on the lower Danube for the first time . Despite their threat to invade the territory of the empire, the Romans succeeded in forcing them to make peace and to provide auxiliary troops. Between 196 and 203 the Jazygens, Roxolans, Dacians, Vandals and other tribes overran the borders from Pannonia (Pannonia) to Lower Moesia. Only after years of campaigns did the Emperor Septimius Severus (193-211) succeed in throwing back the enemy and forcing them to peace. In 202 the emperor also visited some centers in the province such as Nicopolis ad Istrum and probably the garrison towns of Novae and Durostorum .

Late principate

In the course of the 3rd century, the northern border of the province of Lower Moesia became an external border of the Roman Empire again. In the spring of 238 the invasions of the peoples from the Barbaricum began . Carps and Scythians are mentioned in the sources , the latter more likely to be understood as Sarmatians or Goths . The then governor Tullius Menophilus was able to persuade the attackers to withdraw.

Possibly as early as 248 the warriors of a powerful alliance of Goths, Carps, Taifalen , Bastarnian Peukinern and Hasdingen - a sub-tribe of the Vandals - invaded Lower Moesia . With their leaders, the Gothic kings Argaith and Gunderich , they tried in vain to besiege Marcianopolis . This event, which has been handed down by the historian Jordanes , is more likely to be connected in recent research with the events of the year 250/251 or much later. At that time the Gothic king Kniva marched together with the Carps into large parts of Lower Moesia and Thrace and left the country devastated. At Novae the army was divided into two large divisions. One part began with the unsuccessful siege of the legionary site Novae , the other moved to the gates of Philippopolis ( Plovdiv ). The part of the attackers rejected in Novae marched in the meantime to Nicopolis ad Istrum and left a path of devastation. In an attempt to repel the enemy, the rushed emperor Decius (249-251) was defeated and fled to the legionary camp of Oescus . Without the required relief, Philippopolis had to surrender in late autumn 250 and was destroyed by the pillaging Goths. According to the archaeological and numismatic findings, the coastal town of Histria was also the victim of destruction in the middle of the 3rd century - other Black Sea towns were no different. In June 251 the emperor tried at the Battle of Abrittus to capture the booty-laden Goths retreating north, but the Roman troops were defeated again and both Decius and his son Herennius Etruscus were killed. The subsequent peace treaty allowed the Goths to take their rich booty with them. In addition, Rome was to pay them an annual tribute , which kept the Goths from crossing the Roman borders. Just one year later, Kniva demanded that the new governor and later Emperor Aemilianus of Lower Saxony increase the tribute. When Aemilianus refused, a war broke out, as a result of which the Gothic king was defeated that same year.

Nevertheless, the Goths continued their raids on Roman territory in association with the Carps and Burgundians, especially in 254-255, advancing south to Thessalonica ( Thessaloniki ). The massive deployment of the Roman army in Lower Moesia under Decius was also reflected in the money in circulation. According to 249, for example, a significantly higher percentage of coins flowed to Niedermösien than to neighboring Obermösien.

In the years that followed, armies plundered the province. 262 or 263, the Goths pushed again by Lower Moesia and exceeded on their prowl the Hellespontos to in Asia Minor to maraud, being in Ephesos with the Artemis temple one of the seven wonders of the world destroyed. On the march back they passed through Lower Moesia again. After further raids, the province's largest invasion occurred in 269. Thousands of Goths, Herulers, Gepids, Bastarnen, Peukines and other tribes broke into the country with arson. Since this time they intended to settle in the devastated country south of the Danube, their belongings, women and children were in the entourage. The attackers tried unsuccessfully to take the cities of Marcianopolis and Tomoi . Ultimately, the Roman army was able to destroy the enemy at Naissus ( Niš ). But incursions and unrest also had to be fended off in the following decades.

Late antiquity

Diocletian administrative reforms

The far-reaching administrative reforms of the tetrarchic period began in Moesia during the reign of Emperor Aurelian (270–275). He continued the consolidation policy of his predecessor Claudius Gothicus (268-270) and followed the realpolitical realities of the time by abandoning the actual Dacia as a Roman province in 271. Instead, Aurelian had a new Dacian province set up in the northern parts of the areas of Lower and Upper Moesia: Dacia ripensis . Perhaps during his reign the governorship of the Legatus Augusti pro praetore was converted into that of a praeses .

The imperial reforms introduced with Diocletian's accession to power also had an impact on the organization of the provinces. The capital of the now reduced province Moesia inferior , which was now called Moesia secunda , remained Marcianopolis with Odessos ( Varna ) as the most important port city. The eastern part of Lower Moesia with the legionary camps Durostorum and Troesmis had been added to the newly founded province of Scythia minor , which roughly occupied the area of today's Romanian Dobruja. These two provinces, together with the newly founded four Thracian provinces of Thracia , Haemimontus , Rhodope and Europe as an administrative unit, form the "Diocese of Thrace" ( Dioecesis Thraciae) , also known as Diocese V.

In 308, when an attempt was made to save the decaying system of the tetrarchy, the Praetorian prefecture of Illyricum - which also included the diocese of Thrace - was assigned to the emperor Licinius, who ruled from 308 to 324 . After Constantine the Great had secured the western part of the empire and Licinius the eastern part, a dispute arose over the Illyrian prefecture, because both emperors claimed its territory. When Constantine was able to force Licinius to cede the prefecture of Illyricum to him in 314 or 316 after his victorious invasion of the Danube-Balkan region , the diocese of Thrace was detached from the Illyrian administration and added to the prefecture of Oriens . As a result of this measure, the responsibility for the defense of the endangered middle and lower Danube Limes was now divided between the respective emperors in the east and west. Since the demarcation of the two parts of the empire became more and more solid, especially in the last third of the 4th century, this meant that the Balkans, among other things, became more and more the bone of contention for competencies. Attackers from the Barbaricum were given good opportunities to take advantage of the situation to advance on this flank.

Christianity

The first historical evidence of Christianity in Lower Moesia has been passed down through several military martyrs who were murdered at the Legion site of Durostorum in the years 303/304 according to the Diocletian edict of February 23, 303 . Diocletian himself was in this city on June 8, 303. In the years that followed, executions mainly took place in Durostorum . Other places that have survived from the Diocletian persecution are the garrison towns of Noviodunum ad Istrum , Axiopolis ( Cernavodă ), Dinogetia and Novae, calculated according to the number of victims . Most of the professionally documentable victims come from the ranks of the military. In addition to individual soldiers, senior officers and entire families were also executed. Craftsmen were the second most common murder. The historical existence of some of the victims - for example St. Dasius from Durostorum - is beyond doubt.

For the year 325 bishoprics in the province have been handed down, for example for the capital Marcianopolis . Later the religious orientation of individual bishops in the Moesia secunda becomes clear through various surviving documents. As in the neighboring western provinces, Arianism also dominated here . During the christological disputes during the first half of the 5th century, Bishop Dorotheus of Marcianopolis campaigned strongly for the patriarch of Constantinople , Nestorius and his doctrine, Nestorianism . At the Council of Ephesus in 431 he joined the Antiochene School with Jacobus of Durostorum .

Gothic Wars

During the reign of Constantine II (337-340), his father Constantine the Great continued his pro-Goth policy. In 343, a group of Christianized Goths persecuted in Gothic Transdanubia was allowed to settle under the leadership of their Bishop Wulfila in the area around Nikopolis ad Istrum without having to fulfill the usual federal duties. Wulfila is one of the most famous ecclesiastical personalities of his time, who with the oldest Germanic translation of the Bible also preserved the most important Gothic language monument for the future.

In 376, three Gothic sub-associations, which retreated from the Huns invasion of the previous year, turned south towards the Roman Empire. One of the groups, the Terwingen under Alaviv and Fritigern , came in consultation with the then ruling Eastern Emperor Valens (364–378) over the Danube Limes of the Moesia secunda in order to settle as subject ( Dediticii ) in the Balkans. But supplying such a large number of people led the responsible military commander in chief of the province , Lupicinus, to the limits of his possibilities. To accompany the Terwingen on their way to the provincial capital Marcianopolis , he deployed parts of the border troops. When the other two Gothic groups noticed that parts of the border were unguarded, they forced the river to cross. An illegally defected association was defeated and settled in Italy, the other, consisting of Greutungen , was probably settled with the Terwings in the Moesia secunda - the northern part of the diocese of Thrace. In the same year the newcomers rose up in the Gothic war against the Romans after Lupicinius had tried in vain to have Fritigern killed during a guest visit in Marcianopolis. In the course of the war that followed, Moesia secunda was temporarily withdrawn from Roman control after the Goths - united with the Huns and Alans - blocked the passes over the Balkan Mountains. The most brutal clashes in the southern part of the diocese of Thrace culminated in the Catastrophic Battle of Adrianople (378) , in which Emperor Valens was killed. Modares , a Roman military leader of Gothic descent, succeeded in 379 in throwing the rebels now sitting in Thrace back to Moesia behind the Balkan Mountains. With the peace treaty of October 3, 382, which was sometimes doubted by historians, the Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosius I (379–394) confirmed the Goths' claims to settlement areas that were assigned to them along the Danube front, including in Moesia secunda , against Fritigern . According to this Foedus , the country remained Roman territory and the Goths became members of the Empire. But they were able to live tax-free under their own rulers, but in times of war they had to do armed services as Foederati under the Roman command in return for payment . Wulfila is also said to have played an important role in the conversion of Fritigern's Terwingen. After the Tervingi become Kristallationspunkt of the emergent to a new, large unit Visigoth nation Association and I. Alaric had moved to Rome 408, they took their Gothic- homöischen with faith.

Empire division of 395

In the course of the organizational division of the empire in 395 , administrative structures also changed for Moesia secunda . In 395/420, Diocese V (Thrace) fell under civil administration to the so-called “ Byzantine Empire ”, which developed from then on, and Thrace and thus Moesia secunda finally came to the Greek Patriarchate , while the neighboring, in Diocese VII (Dacia) lying Moesia prima , remained subordinate to the Bishop of Rome . It was not until 732 that Moesia came to Orthodoxy in Constantinople .

Huns incursions

Moesia secunda was also devastated during the Huns' invasions . For example, the attackers destroyed the provincial capital Marcianopolis . Ten years after these events, 457, life in the Moesia secunda seems to have recovered faster than that in the adjacent Moesia prima and Dacia ripense . Only Marcianopolis seems to have remained a ruined city at first and Abrittus had taken over the function of provincial capital. The title of Bishop of Marcianopolis was retained, but his office holder probably resided in Kpel . Even twenty years later, when the Ostrogoth King Theodoric 477/478 lived in the Moesia secunda , Marcianopolis still seems to have been in ruins. It is possible that 457 Scythia minor - which was now called Scythia prima - lost provincial status, had been added to Moesia secunda or was administered directly by Kpel.

Slav Wars

Around 527, the historian Prokopios of Caesarea reported the first Slavic invasions on the lower Danube. During the reign of Emperor Justin I (515-527), the Anten crossed the river on the Mösian border, but were thrown back by the imperial nephew Germanos , the master of the diocese of Thrace.

During the reign of Emperor Justinian I (527-565), the diocese of Thrace and thus Lower Moesia remained in Roman hands. On May 18, 536, with the establishment of the quaestura exercitus, the military border defense was reorganized. In addition to Moesia secunda, the Quaestura included the Cyclades , Caria and Cyprus and testifies to the continued importance of the fleet for land surveillance along the Sava Danube Limes. Still, under Justinian, the country suffered heavy fighting and devastation. The army masters of the diocese of Thrace ultimately had too few strengths to take massive action against the raiders who invaded the hinterland. Once the often small groups of attackers had overcome the secured Danube, they could pillage almost unhindered. Only the strongly fortified provincial towns still offered protection in many cases. Around 529 the proto-Bulgarians , around 560 the Avars and again and again the Slavs, who in 559 had managed to advance to Constantinople in association with the Huns , before the general Belisarius could repel them. In order to prevent the permanent conquest of land by the Slavs in the Balkans and to keep the Avars down, Emperor Maurikios (582–602) also led a series of Balkan campaigns with great success . The murder of the emperor by the usurper Phokas , however, ruined all successes. Under the despotic rule of Phocas (602–610), Constantinople, as the regulating power in the Balkans, was temporarily lost completely. In addition, the military strength of Eastern Stream was so bound by ongoing wars with the advancing Persians that both parties were ultimately completely bled to death. In this situation, which was threatening the existence of Constantinople, the Slavs' conquest of land in the Thracian diocese, which was completed around the middle of the 7th century, manifested itself, the northern parts of which now only belonged pro forma to the Eastern Roman Empire. The intruders even managed to advance into the diocese of Macedonia, overcome the Hexamilion barrage and conquer the Peloponnese . Some of the Christians from the Lower Mossian communities took the relics of their martyrs with them while fleeing from the pillaging pagan Slavs . Probably at the end of the 6th century, the remains of Dasius from Durostorum were brought to the Black Sea city of Odessos (Varna), which later came to Italy.

Due to the ongoing turmoil of war, the leading church structures that still existed in the 5th century seem to have completely dissolved by the end of the 6th century. It was not until 680, at the Third Council of Constantinople , that bishops of the Thracian diocese were named again.

First Bulgarian Empire

Proto- Bulgarians also repeatedly advanced into the area of Moesia secunda . In 679 they laid claim to the areas in the Dobruschka area and settled there. The Slavs, who until then had been stateless, were subjugated and made subject to tribute. In addition, they were supposed to offer the proto-Bulgarians military successes against East Stream in the future. With the establishment of the First Bulgarian Empire a little later, the proto-Bulgarians consolidated their regional power in the eastern Balkans.

The military clashes that followed between them and Constantinople ultimately resulted in Ostrom finally having to surrender the Mösian territories to the attackers in 681 and undertaking to pay tribute to the Bulgarians for his own safety. Against Emperor Constantine V (741–775), who had the passes over the Balkan Mountains fortified in order to stabilize the borders of the Eastern Roman Empire, the Bulgarians advancing against it initially suffered heavy defeats. The following crisis in Bulgaria was only ended by the following Khan Krum (802-814), who not only secured the two Moesia for Bulgaria, but also the province of Thrace. In the early Middle Ages , the term "Moesia" experienced a significant expansion. Among other things, in the Vita sancti Clementis , created between 876 and 882, Moesia is equated with Illyria . And the chronicle of Pope Dukljanin from the 12th century makes it clear that the term “Moesia” was also extended to the inhabitants of Bosnia at this time .

Byzantine renewal from 971

The emperor Johannes Tzimiskes, who ruled between 969 and 976, oriented himself towards a restoration of the old Roman size . His invasion of the Balkans in 971 heralded the end of the Bulgarian Empire. Under him, among other things, the territory of the old Moesia secunda was recaptured. During the administrative restructuring, however, the old provinces were no longer re-established, but the thematic system that had been introduced in the meantime was used, with the territory of the Moesia secunda reappearing as a “ paristrion ”. The capital became the old Durostorum, which Johannes renamed "Theodoroupolis".

Important personalities from Lower Moesia

- Maximinus Thrax († 238 in Aquileia), Roman emperor from 235 to 238 AD. The origin of the emperor from Lower Moesia is not certain, but it is also not impossible.

- Flavius Aëtius (* around 390 in Durostorum, † 454 in Rome), Western Roman army master and politician

See also

literature

- Sven Conrad: The grave steles from Moesia Inferior: Investigations into chronology, typology and iconography. Casa Libri, Leipzig 2004, ISBN 3-00-012056-4 .

- Jan Beneš: Auxilia Romana in Moesia atque in Dacia. On the questions of the Roman defense system in the Lower Danube region and the adjacent areas . Academy, Prague 1978, DNB 790311704 .

- Jenő Fitz : The career of the governors in the Roman province of Moesia Inferior. Böhlau, Weimar 1966, DNB 456626050 .

- Max Fluß : Moesia. In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume XV, 2, Stuttgart 1932, Col. 2350-2411.

- Franz Schön, Anne-Maria Wittke : Moesi, Moesia. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 8, Metzler, Stuttgart 2000, ISBN 3-476-01478-9 , Sp. 328-332.

- Bogdan Sultov, Toros Chorisjan: Ancient centers of pottery in Lower Moesia. Sofia-press, Sofia 1976, DNB 208087176 .

- Arthur Stein : The Legates of Moesien. Moesia helytartói. Institute for Coin Studies and Archeology d. Peter Pázmány University, Budapest 1940, DNB 362796890 .

Remarks

- ↑ Lucian Boia : History and Myth. About the present of the past in Romanian society. Böhlau, Cologne / Weimar / Vienna 2003, ISBN 3-412-18302-4 , p. 119.

- ↑ Stefan Radt (Ed.): Strabons Geographika, Volume 2, Book V – VIII: Text and Translation. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2003, ISBN 3-525-25951-4 , p. 251.

- ↑ Reinhold Bichler: Herodotus world. Akademie Verlag, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-05-003429-7 , p. 134.

- ↑ Claude Lepelley: Rome and the Empire in the High Imperial Era 44 BC. BC – 260 AD. Vol. II. The regions of the empire. KG Saur, Munich, Leipzig 2001, ISBN 3-598-77449-4 , p. 312.

- ^ András Mócsy : Studies on the history of the Roman province of Moesia Superior. In: Acta archaeologica Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. 11, 1959, pp. 283-307.

- ↑ Claude Lepelley: Rome and the Empire in the High Imperial Era 44 BC. BC – 260 AD. Vol. II. The regions of the empire. KG Saur, Munich, Leipzig 2001, ISBN 3-598-77449-4 , p. 257.

- ↑ Emilian Popescu: Romanization and assimilation in Roman and late Roman times (2nd-6th centuries) in the area of Romania and their significance for the development of the Romanian people. In: Romanitas - Christianitas. Research on the history and literature of the Roman Empire. de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1982, ISBN 3-11-008551-8 , p. 712.

- ↑ Karl Christ : History of the Roman Empire. From Augustus to Constantine. 6th edition. CH Beck, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-406-59613-1 , p. 272.

- ↑ Miroslava Mirković: Moesia Superior. A province on the middle Danube. Von Zabern, Mainz 2007, ISBN 978-3-8053-3782-3 , p. 7.

- ^ Rumen Ivanov: The Roman defense system on the lower Danube between Dorticum and Durostorum (Bulgaria) from Augustus to Maurikios. In: Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission. Vol. 78, 1997, Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 467-640; here: p. 503.

- ^ Karl Strobel: Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history. Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , S: 157.

- ↑ Marcelo Tilman Schmitt: The Roman Foreign Policy of the 2nd Century AD: Securing Peace or Expansion? Steiner, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-515-07106-7 , p. 110.

- ↑ a b Rumen Ivanov: The Roman defense system on the lower Danube between Dorticum and Durostorum (Bulgaria) from Augustus to Maurikios. In: Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission. Vol. 78, 1997, Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 467-640; here: p. 516.

- ^ Egon Schallmayer : The Limes. Story of a border. 2nd Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-406-48018-8 , pp. 24-25.

- ^ Andrew Poulter: The Lower Moesian Limes and the Dacian Wars of Traian. In: Dieter Planck (Hrsg.): Studies on the military borders of Rome III. 13th International Limes Congress, Aalen 1983. Theiss, Stuttgart 1986, ISBN 3-8062-0776-3 , pp. 519-528; here: p. 526.

- ↑ Géza Alföldy : The beginnings of the epigraphic culture of the Romans on the Danube border in the 1st century AD. In: Miroslava Mirkovic (ed.): Roman cities and fortresses on the Danube. Files of the regional conference, Belgrade 16. – 19. October 2003. Filozofski facultet, Belgrade 2005, ISBN 86-80269-75-1 , pp. 23-38; here: p. 32.

- ^ A b Karl Strobel : Emperor Traian. An epoch in world history. Pustet, Regensburg 2010, ISBN 978-3-7917-2172-9 , S: 251.

- ↑ Marcelo Tilman Schmitt: The Roman Foreign Policy of the 2nd Century AD: Securing Peace or Expansion? Steiner, Stuttgart 1997, ISBN 3-515-07106-7 , p. 90.

- ^ Rumen Ivanov: The Roman defense system on the lower Danube between Dorticum and Durostorum (Bulgaria) from Augustus to Maurikios. In: Report of the Roman-Germanic Commission. Vol. 78, 1997, Zabern, Mainz 1998, pp. 467-640; here: p. 515.

- ↑ Boris Gerov: The incursions of the northern peoples into the Eastern Balkans in the light of the coin treasure finds. In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World . Part II, Volume 6. de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1977, ISBN 3-11-006735-8 , pp. 110-181; here: pp. 126–127.

- ↑ a b Christo M. Danov : The Thracians in the Eastern Balkans from the Hellenistic period to the founding of Constantinople. In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World. Part II, Volume 7, 1. de Gruyter, Berlin-New York 1979, pp. 89-130; here: p. 183.

- ↑ a b Manfred Oppermann : Early Christianity on the west coast of the Black Sea and in the subsequent inland. Beier & Beran, Langenweißbach 2010, ISBN 978-3-941171-30-5 , p. 4.

- ↑ Boris Gerov: The incursions of the northern peoples into the Eastern Balkans in the light of the coin treasure finds. In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World. Part II, Volume 6. de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1977, ISBN 3-11-006735-8 , pp. 110-181; here: p. 133.

- ^ Jenő Fitz : The circulation of money in the Roman provinces in the Danube region in the middle of the 3rd century. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest 1978, p. 295.

- ↑ Boris Gerov: The incursions of the northern peoples into the Eastern Balkans in the light of the coin treasure finds. In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World. Part II, Volume 6. de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1977, ISBN 3-11-006735-8 , pp. 110-181; here: p. 142.

- ↑ Boris Gerov: The incursions of the northern peoples into the Eastern Balkans in the light of the coin treasure finds. In: Rise and Fall of the Roman World. Part II, Volume 6. de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1977, ISBN 3-11-006735-8 , pp. 110-181; here: p. 143.

- ↑ a b Manfred Oppermann : Early Christianity on the west coast of the Black Sea and in the subsequent inland. Beier & Beran, Langenweißbach 2010, ISBN 978-3-941171-30-5 , p. 5.

- ^ Egon Schallmayer , Mario Becker: Limes. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 18, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 2001, ISBN 3-11-016950-9 , pp. 403-442; here: p. 438.

- ^ Peter Jacob: Aurelian's reforms in politics and legal development. (= Osnabrück writings on legal history. 9). unipress, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-89971-148-3 , p. 92.

- ↑ Friedrich Lotter: Displacements of peoples in the Eastern Alps-Central Danube region between antiquity and the Middle Ages (375-600). de Gruyter, Berlin, 2003, ISBN 3-11-017855-9 , p. 8.

- ^ Rajko Bratož: Directory of victims of the persecution of Christians in the Danube and Balkan provinces. In: Alexander Demandt, Andreas Goltz, Heinrich Schlange-Schöningen (eds.): Diokletian and the tetrarchy. Aspects of a turning point (= millennium studies on culture and history of the first millennium AD. Vol. 1). de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 2004, ISBN 3-11-018230-0 , pp. 123-128.

- ^ A b Aurelio de Santos Otero: Bulgaria . In: Theologische Realenzyklopädie (TRE). Volume 7, de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1981, ISBN 3-11-008192-X , p. 365.

- ↑ Herwig Wolfram: The Goths and their history. 2nd Edition. CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-44779-1 , p. 45.

- ↑ Gerd Kampers: History of the Visigoths. Schöningh, Paderborn 2008, ISBN 978-3-506-76517-8 , p. 111.

- ↑ a b Herwig Wolfram : Fritigern. In: Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde (RGA). 2nd Edition. Volume 10, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1998, ISBN 3-11-015102-2 , p. 85.

- ↑ a b Daniel Ziemann: From wandering people to great power. The emergence of Bulgaria in the early Middle Ages (7th – 9th centuries). Böhlau, Cologne, Vienna 2007, ISBN 978-3-412-09106-4 , p. 26. Compare: Gerhild Klose, Annette Nünnerich-Asmus (eds.): Frontiers of the Roman Empire. Zabern, Mainz 2006, ISBN 3-8053-3429-X , p. 179.

- ^ Friedrich Lotter: Displacements of peoples in the Eastern Alps-Central Danube region between antiquity and the Middle Ages (375-600). de Gruyter, Berlin, 2003, ISBN 3-11-017855-9 , p. 82.

- ↑ Daniel Ziemann: From wandering people to great power. The emergence of Bulgaria in the early Middle Ages (7th – 9th centuries). Böhlau, Cologne, Vienna 2007, ISBN 978-3-412-09106-4 , p. 27.

- ↑ Gereon Siebigs: Emperor Leo I. The Eastern Roman Empire in the first three years of his reign (457–460 AD). de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 2010, ISBN 978-3-11-022584-6 , p. 358.

- ^ Heinrich Kunstmann : The Slavs: Their name, their migration to Europe and the beginnings of Russian history in a historical-onomastic point of view. Steiner, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-515-06816-3 , p. 118.

- ^ Berthold Rubin: The age of Justinian. Volume 2. de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 1995, ISBN 3-11-003411-5 , p. 150.

- ↑ Alexander Demandt : History of late antiquity. The Roman Empire from Diocletian to Justinian, 284-565 AD 2nd edition. CH Beck, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-406-57241-8 , p. 177.

- ↑ Otto Mazal : Restoration and Crisis of the Roman Empire (518–641). In: Theodor Schieder (ed.): Handbook of European history. Vol. 1, 4th edition. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-12-907530-5 , p. 308.

- ^ Arnold Angenendt : The early Middle Ages. Western Christianity from 400 to 900. 2nd edition. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1995, ISBN 3-17-013680-1 , p. 236.

- ^ Rajko Bratož: Directory of victims of the persecution of Christians in the Danube and Balkan provinces. In: Alexander Demandt, Andreas Goltz, Heinrich Schlange-Schöningen (eds.): Diocletian and the Tetrarchy (= Millennium Studies on Culture and History of the First Millennium AD. Vol. 1). de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 2004, ISBN 3-11-018230-0 , p. 235.

- ^ Manfred Hellmann : New Forces in Eastern Europe. In: Theodor Schieder (ed.): Handbook of European history. Vol. 1, 4th edition. Klett-Cotta, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-12-907530-5 , pp. 357-369; here: p. 367.

- ^ Heinrich Kunstmann : The Slavs: Their name, their migration to Europe and the beginnings of Russian history in a historical-onomastic point of view. Steiner, Stuttgart 1996, ISBN 3-515-06816-3 , pp. 146-147.

- ^ Paul Stephenson: The Legend of Basil the Bulgar-Slayer. University Press, Cambridge 2003, ISBN 0-521-81530-4 , p. 65.

- ^ Franz Altheim : Decline of the Old World. An investigation into the causes. Vol. 2: Imperium Romanum. Klostermann, Frankfurt am Main 1952, p. 293. For the problem of origin, see also Adolf Lippold : The origin of the emperor C. Iulius Verus Maximinus. In: The Historia Augusta. Steiner, Stuttgart 1998, ISBN 3-515-07272-1 , pp. 82-96.