Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve

| Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve | ||

|---|---|---|

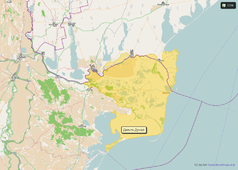

| The narrow part of the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve ( Ukrainian дельти Дунаю ) north of the border is in Ukraine , the larger southern part in Romania. | ||

|

|

||

| Location: | Tulcea , Romania | |

| Next city: | Tulcea and Constanța | |

| Surface: | 4178 km² | |

| Founding: | 1991 | |

| Great white pelicans and cormorants in the Ukrainian part of the delta, 2009 | ||

| Cormorant in the Danube Delta, 2012 | ||

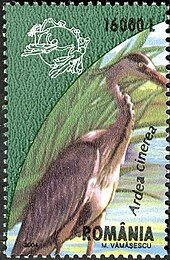

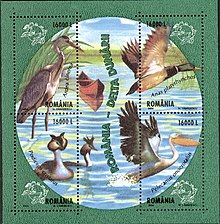

| Birds of the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve, Ukrainian stamp pad from 2004, pictured from left to right are a mute swan, a pygmy shrew, a great egret, a gray goose and a spoonbill | ||

| Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve | |

|---|---|

|

UNESCO world heritage |

|

| National territory: |

|

| Type: | nature |

| Criteria : | (vii) (x) |

| Surface: | 312,440 ha |

| Reference No .: | 588 |

| UNESCO region : | Europe and North America |

| History of enrollment | |

| Enrollment: | 1991 (session 15) |

The Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve ( Romanian Delta Dunării ) is located in the area where the Danube flows into the Black Sea . The Danube Delta prepared according to the Volga Delta the second largest delta Europe represents and covers an area of 5800 square kilometers, of which 72% with an area of 4178 square kilometers under conservation stand. 82.5% of this area is in the Romanian part of the Dobruja region and 17.5% in the Ukraine .

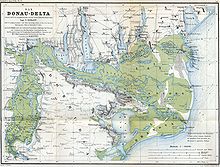

The northern part of the reserve - the actual delta - is traversed by the three mouths of the Danube flowing in from the west: the Chilia arm as the Romanian-Ukrainian state border in the north, the Sulina arm in the middle and the Sfântu-Gheorghe arm in the south. Just south, the fed of channels includes Razim - Sinoie - lagoon complex at. The area has been sparsely populated since ancient times. Agriculture, cattle breeding and fishing often make use of the local natural resources.

So far, around 5200 animal and plant species have been cataloged in the biosphere reserve . The high number of species is attributed on the one hand to the wide range of aquatic and terrestrial habitats , and on the other hand to the geographical coincidence of the Central European forests and the Balkan Mountains with the Mediterranean regions . The closely interconnected habitats such as reed beds , floating islands , oxbow lakes, alluvial forests and extremely dry biotopes in the dunes form a unique network of over 30 ecosystems in the estuary. Some of these species are considered rare or critically endangered. The reserve is home to the world's largest contiguous reed area with an area of around 1800 km² and an important bird sanctuary with the largest colonies of the Great White Pelican and the second largest of the Dalmatian Pelican in Europe.

In 1990 Romania became the first country bordering the Danube to declare its part of the delta a biosphere reserve. The list of wetlands of international importance in the Ramsar Convention was expanded to include the delta in 1991. In 1993, UNESCO included the area on the World Heritage List . Romania designated the reserve as a nature reserve of national and international importance in the same year . The Ukrainian part of the Danube Delta has also been a recognized biosphere reserve since 1998.

From the 1960s, large parts of the marshland were drained for agricultural use, which by 1986 destroyed around a fifth of the natural habitat in the delta. In 2000 Romania, Bulgaria , Moldova and Ukraine committed themselves to the protection and renaturation of the wetlands along the approximately 1000 km long lower Danube. This Green Corridor , initiated by the World Wide Fund For Nature (WWF), created the largest cross-border protected area in Europe.

The unemployment rate for local residents is between 30 and 40 percent. They are hoping for opportunities from the European Union's initiatives to promote gentle tourism in the region, but tourism has already reached the limits of its natural compatibility in some areas. Accidents in the oil industry, the straightening and containment of shipping lanes, but also illegal poaching affect the ecological balance .

geography

landscape

The Danube is the most important receiving water in Southeast Europe and the collecting artery for the major rivers of the Eastern Alps ( Inn , Drau ), the Carpathians ( Tisza ) and the Eastern Dinarides ( Save ). The Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve is located in the area where the Danube flows into the Black Sea and forms a refuge for a large number of plants and animals.

More than half of the total area of the reserve of 5800 km² includes the area commonly referred to as the Danube Delta with 3510 km², while the remaining area extends to the upstream Danube floodplains between Isaccea and Tulcea (102 km²), the Razim-Sinoie lagoon complex (1145 km²) , a narrow strip in the Black Sea (1030 km²) down to a depth line of 20 m, and the area on the Danube between the island of Cotul Pisicii and Isaccea (13 km²). The reserve extends in the south-eastern part of Romania with an area of 3446 km² over the districts of Tulcea and Constanța , and a 732 km² area in the south of Ukraine in the Odessa Oblast . The Danube forms the 54 km long natural border between Romania and Ukraine. There are no official border crossings in this part of the border, the closest crossings are in Galați and Brăila .

The reserve is integrated into the historical Dobruja landscape. The mostly hilly surrounding region can be divided physiographically into the following areas:

The hinterland is predominantly marked by Paleozoic and Mesozoic soil formations. Its northern part has the highest peaks in the region with altitudes of 180–467 meters above zero sea level on the Black Sea. The south of the Dobruja consists of limestone plateaus that are about 100 to 200 meters above sea level and are covered by loess soils . Overall, 60 percent of the Dobruja land area does not rise above 100 meters. In the inner area of the Dobruja, the terrain flattens from north to south to maximum values of 300 meters. The predominant soil-forming rock is schisto. The eastern area along the coast is characterized by the extensive delta area of the Danube and its numerous lagoons. The low flat plain is 0.52 m above mean sea level of the Black Sea and has a mean rise in general gradient of 0.006 m / km. The maximum height difference is 15 m, which results from the highest point (+12.4 m) in the dunes near Letea and the lake bottom (−3 m) in the marine part. 20.5% of the delta area is below sea level of the Black Sea, the remaining 79.5% are above. Of the area above sea level, 54.6% are between 0 and 1 m in height, and 18.2% between 1 and 2 m. Overall, 93% of the delta lies within a hypsometry of 0–3 m.

Under the hydromorphological aspect, the reserve is divided into:

Areas from before the delta was formed

These areas are located in the historical Budschak landscape north of the Chilia arm. The loess deposits in this area were eroded by water and deposited as the base of the Câmpul Chiliei and Stipoc sandbanks . They make up 2.4 percent of the area of the delta.

Sandbanks on river arms or by the sea

The river sandbanks lie along the edges of the main branches and branches of the Danube. The accretion and height of the sandbanks decrease towards the sea. For the formation of the sea sandbanks running parallel to the sea coast (also known as grind ), the sea currents are primarily responsible, which formed natural sea dams from alluvial Danube sediments and which increased over time due to further deposits in the sea. The larger sandbanks were deposited as a series of high dunes with dune transverse valleys in between.

Rivers and canals

At the beginning of the delta west of Tulcea, the mean flow of the Danube is 7320 m³ / s. The differences between low water (2000 m³ / s) and high water (24,000 m³ / s) are considerable.

With a length of 116 km, the Chilia arm to the north is the largest of the three arms of the Danube. At the junction in Ismajil the Tulceaarm separates from the Chiliaarm, after which the Chiliaarm still carries 67 percent of the total amount of water of the Danube through about 25 mouths to the Black Sea. Gravel, sand and mud carried along with organic residues are deposited in a delta of around 2,430 km². Two fifths of this area is on Ukrainian territory.

The Sulinaarm runs in a straight line from west to east and, after the junction, only carries about 13 percent of the total river water, but is the most important arm of the Danube for shipping . Between 1858 and 1902 it was regulated and its stream bed deepened. The originally 84 km long waterway was shortened to 62 km by straightening its pronounced curves. Dredging and maintenance work continues to this day. The water depth reaches at least 23 feet = 7.32 meters and thus enables the traffic of medium- tonnage shipping .

About 20 percent of the water flows through the 70 km long Sfântu-Gheorghe arm into the sea, which forms the northern border of the Dobruja highlands ( Podișul Dobrogei in Romanian ) as far as Murighiol . The arm flows through the southernmost and most scenic part of the Danube Delta. Traces of human intervention are the least visible in its surroundings. This area is sparsely populated; however, the flora and fauna are rich.

The area between the Chilia and Sulina arms is called Letea ; between the Sulina and the Sfântu-Gheorghe arm lies the Caraorman area ; between the Sfântu-Gheorghe arm and the Razim and Dranov lakes is the Dranov area .

The network of numerous side arms, some smaller rivers, canals and side canals runs through the plain and determines the movement of water through and around the delta. These waterways often expand to form lakes and form, among other things, the Razim-Sinoie lagoon complex

Lakes

Most of the lakes in the reserve are river limanes , marine limes , or brackish water lagoons . The elongated and deep Jalpuch and Kotlabuch lakes are limanes on the Ukrainian side of the delta.

The Razim Lake and the Sinoie Lake south of the actual delta are brackish water lagoons. To the west and south the lakes border on the Dobruja plateau and in the north on the swamp area of the Sfântu-Gheorghe arm. The eastern side is bordered by a series of low sandbars. Lake Razim extends over an area of around 870 km² and, together with the other lakes, forms a coherent complex of 1,145 km². The lake, which is up to three meters deep in some places, was originally connected to the Black Sea at Portița (German: Türchen ), but is now separated from it by a dike. The dykes are occasionally hit by violent storms. The Razim Sinoie lagoon complex is constantly under water with 75 to 80 percent of its area. The Sfântu-Gheorghe arm feeds Lake Razim through the Dranov and Dunavăț channels . In the south of the border Golovita Lake and Salcioara Lake on; This is followed by the Smeika and Sinoie lakes, in the west is the Babadag lake , in the north the Calica lake and in the east the Dranov lake .

From 1980 in communist Romania, many of the lakes in the area around Pardina and Sireasa were drained for intensive agricultural use. This reduced the lake area from 313 km² (9.28 percent of the area of the delta) to 258 km² (7.28 percent of the delta area). The larger lakes there include the Dranov Lake (21.7 km²), the Gorgova Lake (13.8 km²), the Roșu Lake (14.5 km²) and the Lumina Lake (13.7 km²). Before 1980 there were 668 lakes in the Romanian part of the reserve, after which drainage projects reduced their number to 479.

Swamps

87 percent of the delta consists of marshland; the rest is alluvial soil . The delta forms the largest wetland in Europe. The swamps lie between −0.5 and 1 m above the water level and surround the lakes in the delta depressions. In early summer, the amount of water flowing into the Danube swells due to meltwater from the mountains and floods the swamps. The wide estuary area between the estuary arms has a high population of reeds. Driven by the current, floating reed islands move through the swampy space, which is subject to constant change. The waters are bordered by natural dams. The drainage projects of the 1980s also drained many of the delta's swamps and bogs.

Emergence

The Danube Delta was formed from a bay more than 10,000 years ago. At that time, the sea level at this point was between 50 and 60 meters below its current height. In this stage, the emergence of an "initial belt" was indicated, which corresponds to today's Letea Forest , Caraorman Forest and Crasnicol and ultimately led to the damming of the bay. Today's delta was formed by further deposits of billions of tons of floating debris . At medium high tide, the Danube flows at over 6000 cubic meters of water per second at Ceatalul Chiliei , where the river divides into two arms, and carries around 80 million tons of alluvial material with it every year. In connection with currents and waves, a labyrinth of canals, lakes and reeds formed.

It was not until the end of the Little Ice Age that sand began to collect in the mouth of the Danube into the Black Sea. Since then, debris and fine mud have washed into the Danube from the mountain slopes of the Alps and Carpathians . The coarse rubble already settled in the high-current upper areas of the river. The fine mud was transported to the lower Danube and finally to the Black Sea. The ocean currents did not distribute the mud evenly in the ocean, but instead piled it up in the bay. On the surface of these accumulations of sand and mud, a network of watercourses developed , some of which were repeatedly blocked by sand or reed islands and silted up , others were created by floods, which constantly changed the nature of the delta. Only the three large estuary arms of the Danube have remained almost unchanged since they were canalised and straightened . From the late 19th century the delta was calmed; Dykes protect large areas from flooding, and the reinforcement of the banks prevents the meanders from migrating . The increase in shipping initiated the expansion of ports.

The Sfântu-Gheorghe arm is the oldest arm of the Danube and was the first arm to form its own delta. Parallel to the shoreline of Sfântu-Gheorghe arm lined up especially in the field more in seasons arranged dunes on that show older coastlines. With around 80 million tons of suspended matter per year, its delta is currently growing further into the sea.

The Sulina arm developed in the deposits of the Sfântu-Gheorghe arm and took over an increasing influx of sediments, forming its own delta. It is the shortest of the three river arms and is currently no longer growing. By erecting concrete walls protruding far into the sea to secure the traffic routes, the suspended solids are now carried out of the delta and no longer serve the coastal structure. Numerous still waters in the delta are cut off from the sediment supply and are gradually silting up.

The port of Chilia Veche on the Chilia arm was five kilometers from the sea in the 15th century, today it is about 30 kilometers. On this heavily sedimenting arm, the coastline is currently advancing four to five meters per year, especially east of Wylkowe . Sediments that reach the sea through the Chilia arm are carried by the ocean current and are deposited further north around the Jibrieni formation .

The Pleistocene Rias of the Jalpuch and Kotlabuch Lakes were separated from the open sea in the Holocene by the deposits of the Danube. These river limans emerged from the old confluences Gârlița , Oltina , Dunăreni , Baciu , and the marine limanes Corbu , Siutghiol , Tașaul through former river mouths. Lake Razim and the neighboring Sinoie lagoon are spits that were formed in the former sea bays by deposits.

climate

The Danube Delta has a continental climate with maritime moderation. Low precipitation and long hours of sunshine are characteristic. The average amount of rain is 457.2 millimeters per year and the average annual temperature is 11 ° C, but extreme fluctuations are not uncommon. The dry climate favors desertification and prevents the formation of forests.

The temperature extremes measured so far were -23.6 ° C on February 9, 1929 and +37.5 ° C on August 20, 1946. In Tulcea the thermometer rises above +30 ° C for about 100 days a year. In Sulina there are an average of 80 warm days a year. Between May and October the mean temperature is +19.0 ° C and the sun shines for around 300 hours a month.

Rain often comes down as downpours that are short-lived. Most precipitation falls in June and least in February and March. In the drought year of 1942, the annual rainfall in Sulina was only 134.4 millimeters.

The wind blows almost constantly; the number of windless days over the course of a year is between 25 and 30. The prevailing wind direction is northeast. Strong and cold northeast winds called Crivăț can reach high speeds due to the low breaking through mountains and forests.

| Average temperature (monthly average / annual average) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | yearly |

| Tulcea | −1.8 ° | −0.2 ° | 4.2 ° | 10.3 ° | 16.2 ° | 19.9 ° | 22.2 ° | 21.1 ° | 17.4 ° | 12.6 ° | 6.2 ° | 1.8 ° | 10.8 ° |

| Sulina | −0.7 ° | −0.2 ° | 4.1 ° | 9.6 ° | 15.8 ° | 20.1 ° | 22.5 ° | 21.8 ° | 17.9 ° | 12.7 ° | 6.8 ° | 2.1 ° | 11.1 ° |

| Precipitation amount (monthly average / annual average in mm) | |||||||||||||

| month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | yearly |

| Tulcea | 35.5 | 26.4 | 30.8 | 35.7 | 39.4 | 50.2 | 46.9 | 44.5 | 37.7 | 32.0 | 29.4 | 35.0 | 443.0 |

| Sulina | 24.2 | 21.0 | 21.1 | 21.6 | 34.2 | 45.5 | 34.5 | 40.8 | 26.4 | 33.6 | 27.2 | 28.9 | 359.0 |

Human geography

Settlement and borders

- History atlas

Archaeological excavations at Baia-Hamangia found traces of the Hamangia culture from the Neolithic period .

The area was originally inhabited by Thracians , first by the Getes , then by the Dacians . From the 7th century BC Several Greek colonies were established along the Black Sea coast. The region was later targeted by Celtic and Scythian invasions. For a time it was part of the Kingdom of Dacia .

In ancient times, Scythia Minor referred to the region whose borders roughly correspond to the historical Dobruja landscape , which is now partly in Romania and Bulgaria. The earliest description of the region can be found in Herodotus , who lived between 454–447 BC. BC traveled the area and saw the beginning of Scythia north of the Danube Delta.

Other ancient scholars and travelers wrote about the estuary of the Danube, among them Polybius (201–120 BC), who noticed "large amounts of mud that the river drags into the sea" and reported a sandbank that was dangerous for navigation. In his detailed descriptions he feared “the Black Sea would be filled in” with mud. Also Pliny the Elder and Arrian mentioned the Danube Delta. In a Roman decree from Histria , the area was declared in the 2nd century BC. . AD as Scythia called. The first use of the name "Scythia Minor" ( Mikrá Skythia ) can be found in the geography of the Greek geographer Strabo (63 BC – 23 AD) and the geographer and mathematician Claudius Ptolemy (around 100–180) from Alexandria left records of the delta, as well as the fish trade in the port of Histria was mentioned in historical documents.

In 29 BC BC Marcus Licinius Crassus Moesia conquered . The delta then became part of the Roman province of Moesia Inferior . The fortresses of Halmyris near Murighiol, Salsovia and Aragmum along the Sfântu-Gheorghe arm formed the focus of trade during the Roman era . The Trajan's Wall ended at the northern tip of the Danube Delta.

In the course of the reforms of Diocletian during his tenure (284-305) as Roman emperor, the region was separated from the province of Moesia as a separate province of Scythia . The delta then became part of the Dioecesis Thraciae . With the division of the empire in 395 , the province came under Byzantine control. The region kept the name Scythia Minor until the Slavs conquered the Balkans in the 7th century. Then the classic name was replaced by the Slavic Dobruja . Until the 13th century, the region was alternately under Byzantine and Bulgarian rule.

Tulcea has been an important port city since ancient times. The first places recorded on sea maps are Sulina around the year 950, Chilia Veche as a trading center with its own administration and its own coins in the 13th century, and Sfântu Gheorghe in the 14th century. In other phases of settlement, which lasted until the beginning of the 20th century, Slavs and Romanians from Bessarabia and Transylvania immigrated to the interior areas of the delta such as Caraorman and Letea .

In the 15th century the Danube Delta was part of the Ottoman Empire as Sanjak Tulça . Turkic peoples such as Turkmen , Oguz and Kipchaks , but also Nogay (Alttataren) were established in the 13th century in the region.

At the beginning of the 16th century, Armenians immigrated to the area via the trade route from Lviv to Constantinople . Around this time there were also Roma who had converted to Islam under the influence of the Ottoman Empire. Greeks and Jews lived mainly in the urban environment of the region from the 17th century.

In rejecting the church reform of the Russian Patriarch Nikon , the old Orthodox Lipovans , fleeing religious persecution by the Russian Orthodox Church, withdrew from the Moscow area to the inaccessible areas of the delta in the 17th century . Ukrainian Chacholes , the successors of mercenaries Cossacks who originally settled along the Don River , sought refuge in the Danube Delta after their military disempowerment in the middle of the 18th century.

After the Russo-Turkish War (1806–1812), the Ottoman Empire and the Russian Empire agreed on a border along the Chilia arm, and from 1829 along the Sfântu-Gheorghe arm. At the beginning of the 19th century, permanent settlements such as CA Rosetti (Satu Nou) were established in the area around Letea and Chilia to operate transhumance - seasonal changes in pasture areas in remote pasturing over long distances, resulting in high mobility. Immigration from the Bessarabian region of Budschak and the Ukrainian settlements of Wylkowe and Kilija contributed significantly to the population growth in the villages around Letea in the 19th century.

The first German "colonists" in Dobruja consisted mainly of peasant families originally from southern Germany, who settled in several waves between 1841 and 1856 from the neighboring Russian governorate of Bessarabia and Cherson, also in the Danube Delta, where they included the places Malkotsch and Atmajah founded. Over the course of its hundred-year history, they formed the ethnic group of the Dobrudschadeutschen , which in 1940 de facto dissolved during the Nazi era in the course of their resettlement " Heim ins Reich ".

The Third Peace of Paris of 1856 ended the Crimean War , as a result of which the Danube Delta fell to the Ottomans. In the peace the European powers guaranteed free navigation on the Danube . The European Danube Commission and the Commission of the Danube Bank States were founded to solve day -to-day business problems . In 1870 Sulina received the status of an international free port . Within the Tatars of the Danube Delta, the Crimean Tatars who immigrated here after the Crimean War are still the largest group.

After the Turkish defeat in the Russo-Ottoman War in 1878, the border between Russia and Romania ran along the Chilia arm. In the course of the incorporation of the Dobrudscha into Romania after the Berlin Congress , the delta was populated with Romanians as planned , with "colonies" such as Carmen Sylva and Floriile being founded along the arms of the Danube . The place Crişan later developed from them .

The nationality of some of the Danube islands on the Chilia arm - Tatarul Mic, Tatarul Mare, Daleru Mic, Daleru Mare, Maican, Cernofica and Limba - was controversial after the Second World War . From 1948 they belonged to the Soviet Union, today they are part of the Ukraine. The nearby Snake Island was handed over to the Soviet Union in a secret protocol dated May 23, 1948, which the Romanian public did not know about for decades.

The Socialist Republic of Romania moved between 1960 and 1980 targeted at specialists in fish farming, cane cultivation and agriculture in the Danube Delta. Military units were also stationed in the border area. Since the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Chilia arm and later its side arm Stambulul Vechi (German Old Stambul ) have formed the border between Romania and Ukraine.

population

Due to its location on the river and the sea, it has always been a place of settlement, passage and refuge for the most diverse cultures. Today, besides the Romanians, the Ukrainians ( Chacholes ) and Lipovans shape the ethnic landscape in the Danube Delta. In the remote villages of the Danube Delta of Sfântu Gheorghe, Caraorman, Letea and Chilia Veche, mainly Ukrainians live. As a result of their linguistic assimilation - Ukrainian language skills are only available in the older population - most of the Chacholes identify with the Romanians. A predominantly Romanian population can only be found in CA Rosetti and Sulina .

In 1960 the population in the Romanian part of the region reached its highest level to date of around 21,000. Parts of the population emigrated from the area in the 1990s. In 2002 about 14,000 people lived in the Danube Delta, mostly on smaller islands made up of river and sea sand banks , of which 68.5 percent were in villages and 31.5 percent in the city of Sulina. The population density is around 3.5 inhabitants per square kilometer.

According to the 2002 census, the population of the Danube Delta was made up as follows:

- Romanians: 12,666 people (87%)

- Russians , Lipovans: 1438 people (10%)

- Ukrainians (Chacholes): 299 people (2%)

- Other ethnic groups (1%): Roma (69 people), Greeks (63), Turks (17), Hungarians (12), Bulgarians (3), Germans (2), Armenians (2), others (12).

15.3% of the population live from fishing, 29% are employed in forestry and agriculture, 15.7% work in industry, construction, trade and the service sector. 15.4% live from tourism, transport and telecommunications, 1.9% work in the health sector, 5.7% are active in education and culture, a further 13.5% in public administration and 3.6% in other areas. The three branches of the Danube, Chilia, Sulina and Sfântul Gheorghe, separate the residential areas and are their main sources of drinking water.

The population development in the reserve is declining, with the towns of Sulina and Tulcea recording an increase of 60% since the political change in 1989. 88.5% of the localities in the Danube Delta are considered to be small villages, of which Chilia Veche with 2946 inhabitants, Sfântu Gheorghe with 1068 inhabitants and Pardina with 791 inhabitants are the most populous villages in the rural area. The remaining settlements each have fewer than 500 inhabitants. The unemployment rate is between 30 and 40%.

In 1989 there were 17,000 people in the Ukrainian city of Wylkowe, and in 2013 there were around 10,000 inhabitants.

Traditional architecture

- Clay brick production, 2003

- Village impressions

The traditional architecture and the shape of the settlements are adapted to the main occupation of the residents and the surrounding natural space. The elongated fishermen's houses in the street villages of the Lipovan population differ significantly in shape and design from the farmsteads of the farmers and the solid stone houses of the merchants.

The locals of the Danube Delta have always used natural resources such as clay, stones and reeds to build their simple traditional houses. The clay is formed into bricks that are used to build walls. The roofs are with thatch covered. The natural building materials, which do not require any elaborate preparation for processing, are in abundance in the Delta. For the production of clay bricks ( Ceamur ) the loess- containing soil is mixed with straw and chaff and tamped down . Oak wood is often worked into the corners of the houses made of loess earth to prevent wall breakage due to thermal expansion. Mud walls in front protect many mud houses from strong winds and regular flooding. The mud bricks are also used in rural areas to build shepherds' huts and storage sheds. Concrete construction predominates in the urban space of the delta.

Development of the protected area

The Letea Forest was designated as a nature reserve as early as 1938. On August 27, 1990 Romania declared the Danube Delta a biosphere reserve by decree, after which the administration of the Biosphere Reserve of the Danube Delta ( Romanian Administrația Rezervației Biosferei Delta Dunării , ARBDD) was brought into being. The aim of the ARBDD is to prevent the exploitation of natural resources, which can disturb the natural balance. The ARBDD sets the closed seasons for the animal population in the delta. The list of wetlands of international importance in the Ramsar Convention was expanded to include the delta in 1991. On February 15, 1993, UNESCO added the area to the World Heritage List. In the same year Romania designated the reserve as a nature reserve of national and international importance with Law 82/1993 . Since 1998 the Ukrainian part of the Danube Delta has also been a recognized biosphere reserve, for which there is a separate reserve administration ( Ukrainian Дунайський біосферний заповідник ).

Romania, Bulgaria, Moldova and Ukraine committed themselves on June 5, 2000 to the protection and renaturation of the wetlands along the 1000 km long lower Danube. With this 6,000 km² green corridor initiated by the WWF , the largest cross-border protected area and renaturation project in Europe was created. The biosphere reserve is home to the world's largest contiguous reed area and an important bird sanctuary with the largest pelican colony in Europe. The WWF recognized the commitment of the participating countries as a "gift to the earth".

In 2007 the “Danubeparks” project was created to protect and renaturate the ecosystem along the Danube. It is part of the coherent network of protected areas Natura 2000 , which was established within the European Union according to the Fauna-Flora-Habitat Directive . Since then, an area of 4178 km² has been protected . The Danube bordering states Germany, Austria, Croatia, Hungary, Slovakia, Slovenia, Bulgaria and Romania participated in the project, which includes 15 nature reserves, including the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve in Romania, the Danube Auen National Park in Austria, the Drawa National Park in Hungary, the Lonjsko Polje nature park in Croatia, the Đerdap national park in Serbia, the Persina nature park in Bulgaria and the Donauauwald nature park in Neuburg – Ingolstadt in Germany.

Since 1989 the Friends of Nature International (NFI) has recognized ecologically valuable, cross-border regions in Europe as Landscape of the Year with the aim of contributing to sustainable development. On June 3, 2007, the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve was declared the Landscape of the Year 2007-2009 in Tulcea by NFI President Herbert Brückner in the presence of the President of the International Danube Protection Commission (ICPDR) Lucia Varga , regional politicians and a Ukrainian delegation. Since then, a pelican at the port has been commemorating the landscape of 2007-2009 in Romanian, Ukrainian, English and German as a sign of cross-border understanding.

In addition to the WWF, the International Commission for the Protection of the Danube (IKSD) is committed to preserving the delta . In 2006, under her patronage, a conference on the protection of the Danube Delta took place in Odessa, Ukraine, which was attended by numerous conservationists and delegations from the delta neighbors Romania, Ukraine and Moldova.

Zoning

The Romanian part of the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve has been divided into four protection zones by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN):

Core zone

The core zone of the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve is divided into 18 strictly protected zones. In order to preserve biodiversity, these are designated as a strict nature reserve / wilderness area and cover 8.7 percent of the reserve with around 506 km². These zones have been classified by the World Commission on Protected Areas (German: World Commission for Protected Areas ) as "Category IV: Biotope / species protection area with management protection area, for the management of which targeted interventions are made".

The 18 strictly protected zones of the IUCN Category IV biotope / species protection area of the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve are:

| Serial No. | Strict nature reserve | Area in km² |

Locality, district | Type of biotope, species protection area | Meaning according to the management plan of the reserve administration ARBDD | image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Roşca-Buhaiova | 96.25 | Chilia Veche , Tulcea County | Biotope complex | It is home to the largest pelican colony in Europe and is a nesting place for ducks |

|

| 2. | Letea Forest | 28.25 | CA Rosetti , Tulcea County | Forest reserve | Forest with a subtropical character: Mediterranean, Balkan, subtropical and steppe vegetation |

|

| 3. | Lake Răducu | 25th | CA Rosetti, Tulcea County | Biotope complex | Preservation of the fish population of lakes Răducu and Răduculeț Preservation of the vegetation of the wetlands |

|

| 4th | Lake Nebunu | 1.15 | Pardina , Tulcea County | Bird sanctuary | Nesting and feeding place for Limikolen and duck birds. Preservation of the fish population in lakes with shallow depths |

|

| 5. | Vătafu-Lunghuleț | 16.25 | Sulina , Tulcea County | Bird sanctuary | Preservation of the diverse ecosystems: steep banks, small lakes, wetlands, floating and fixed reed islands, dunes |

|

| 6th | Caraorman Forest | 22.50 | Crișan , Tulcea County | Forest and bird sanctuary | Oak forest with centuries-old trees, nesting place for sea eagles |

|

| 7th | Brackish lake Murighiol | 0.87 | Murighiol , Tulcea County | Biotope complex | 206 species of birds: Limikolen, ducks and geese | |

| 8th. | Erlenwald Erenciuc | 0.5 | Sfântu Gheorghe , Tulcea County | Forest and bird sanctuary | Preservation of the reserve's only alder population, a nesting site for sea eagles |

|

| 9. | Popina Island | 0.98 | Valea Nucarilor , Tulcea County | Bird sanctuary | Passage place for migratory birds, nesting place for shelduck Preservation of steppe and water vegetation |

|

| 10. | Sakhalin-Zătoane | 214.1 | Sfântu Gheorghe, Tulcea County | Bird sanctuary | 229 species of birds: largest colony of Dalmatian pelican and sandwich tern | |

| 11. | Periteaşca-Leahova | 41.25 | Jurilovca and Murighiol, Tulcea County | Bird sanctuary | 249 bird species: migration, feeding, nesting and wintering place for Limikolen, geese and ducks | |

| 12. | Capul Doloșman | 1.25 | Jurilovca, Tulcea County | Bird sanctuary archeology |

Nesting place for swifts and wheatear archeology: Orgame -Argamum |

|

| 13. | Grindul Lupilor | 20.75 | Mihai Viteazu , Constanța County | Bird sanctuary | Passage, feeding place for geese and duckbirds Vegetation specifically for sandy soils |

|

| 14th | Istria sinoie | 4th | Istria , Constanța County | Archeology biotope complex |

Protection of the Moorish tortoise, arrow snake, dice snake 288 bird species: migration and feeding place for ducks and geese birds, Limikolen Archeology: ruins of the fortress Histria |

|

| 15th | Grindul Chituc | 23 | Corbu , Constanța County | Bird sanctuary | 289 bird species: migration and wintering place for migratory birds Preservation of the only habitat of the jackal in the reserve |

|

| 16. | Rotundu Lake | 2.28 | Isaccea , Tulcea County | Water and bird sanctuary | Preservation of the only uncontrolled Danube Auen Lake Preservation of the fish population |

|

| 17th | Potcoava Lake | 6.25 | Crișan, Tulcea County | Water and bird sanctuary | Feeding and nesting place for waterfowl Preservation of the fish population: crucian carp, tench |

|

| 18th | Belciug lake | 1.1 | Sfântu Gheorghe, Tulcea County | Water and bird sanctuary | Preservation of the fish population: crucian carp, tench, nerfling feeding and nesting place for water birds |

|

Unauthorized visitors face fines of up to 6000 lei (around € 1400). Between 2010 and 2013, 305 people were suspected in the Romanian part of the reserve, of whom 207 were fined a total of 80,365 lei (around € 18,500).

Buffer zones

Around the Strict Nature Reserve / Wilderness Area , 13 buffer zones were set up on an area of over 2233 km² (38.5 percent) surrounding the strictly protected areas in order to achieve better protection for the core zone: Agriculture and fishing are restricted here allowed. For example, it is not allowed to fish in the spring so as not to disturb the brood of birds.

| Serial No. | Buffer zone | Area in km² |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Matita-Merhei-Letea | 225.6 |

| 2. | Sontea | 125 |

| 3. | Caraorman | 138.3 |

| 4th | Lumina - Vătafu | 134.6 |

| 5. | Dranov | 217.6 |

| 6th | Sărături-Murighiol | 0.05 |

| 7th | Rotundu Lake | 12.4 |

| 8th. | Popina Island | 2.60 |

| 9. | Capul Dolosman | 0.28 |

| 10. | Zmeica sinoie | 315.1 |

| 11. | Potcoava Lake | 29.37 |

| 12. | Periteasca Leahova | 2.1 |

| 13. | Maritime buffer zone | 1,030 |

Economic zones

About half of the reserve is designated as an economic zone. The economic zones with a total area of 3061 km² (52.8 percent) are used for agriculture, fishing, forestry and residential areas.

Renaturation zones

After the Romanian Revolution , the country's new government decided on measures to renaturalize the delta, which were first implemented in 1994. By opening dams, drained areas were used again as flood plains, and after about ten years the first successes in restoring the ecological balance became apparent. The biosphere reserve is the largest ecological renaturation zone in Europe, in which around a tenth of the drained areas have been renatured since 1991.

In 2013 around 150 km² were renatured. With the help of the WWF, drained areas are reconnected to the freshwater flow. Alluvial areas that were once converted into fields, pasture land, fish farms and poplar cultures are now to be renatured. The environment ministers of Romania, Moldova and Ukraine agreed in 2000 to expand the biosphere reserve to the mouth of the Prut River and to jointly manage the project.

Ecosystems

The mouth of the Danube encompasses a network of closely interconnected habitats and ecosystems of reed beds, floating islands, oxbow lakes and lakes, alluvial forests and extremely dry biotopes in the dunes. The reserve is divided into four categories that include around 30 ecosystems. These include the three natural, i.e. aquatic , swampy and terrestrial habitats. In addition, there are the anthropogenic habitats with fish farming, agricultural and forestry facilities or human settlements. A distinction is also made between eleven aquatic, four swampy, five terrestrial and 16 dike ecosystems that intersect with one another. Some of the plants and animals that live here are considered rare or threatened with extinction. The reserve is home to the world's largest contiguous reed area with an area of around 1800 km².

The meandering rivers in the shallow lower reaches of the Danube are divided into the free water body , the hyporheal (area of flowing water under the surface water) and the benthal (area at the bottom of the water), which form their own ecosystems. The living beings in the transition area between water and solid surface had to adapt to this habitat. Some species developed suction cups or byssus threads in order not to be carried away by the water, such as the leech ( Hirudinea ) or mussels ( Bivalvia ). The food chain of the ecosystems of the river area ranges from zoo or phytoplankton to insects and predatory fish , which in turn are hunted by piscivorous birds. Coarse fish feed on plankton, plants, insect larvae and snails. Omnivorous fish of the river area are the smooth fat, the Russian sturgeon, the starfish and the catfish. Representatives of the predatory fish are the asp , the giant house or the pikeperch .

The river banks and dams of the reserve are often reinforced with rocks or concrete for stabilization. These formations provide shelter for reptiles , amphibians and crabs . The vegetation on the natural river banks depends on the flow speed of the water. Heavy vegetation has a slowing effect, which can lead to the formation of an ecosystem that resembles stagnant water . Most of the time there is little vegetation on the river banks. There are sandpipers here , and kingfishers on steeper river banks . The standing waters include the lakes, the slowly flowing tributaries and the canals leading into dead ends. Amphibians and species of fish such as carp, tench, bream, perch, pike, pikeperch or catfish reside between the water lilies. There is also a large number of birds such as ducks, geese, herons and pelicans. The largest pelican colony in Europe lives here. Around 20 rare plant species in the reserve depend on wild horses to survive in their ecosystems.

Marshland or swamp vegetation cover 1,435 km² or 43 percent of the delta. The areas are mainly characterized by reeds and reed islands. This ecosystem is constantly changing, as the reed islands, some of which are mobile, are permanently changing the landscape, which requires constant adaptation from the species that occur here. Fish prefer marshland for laying their eggs, as the juvenile fish find protection from predatory fish between the aquatic plants. Many bird species also use the marshland to raise their offspring, as the nests in the dense vegetation are better protected from predators. Reptiles such as turtles and snakes, and mammals such as wild boar and raccoon dogs also live here.

Poplars, willows and bushes thrive in river dyke landscapes. Most of the ecosystems were able to develop on the sea dikes. Their flora is more complex than that of river dikes, which are influenced by human activity. Between the numerous sand dunes, forests have formed in some places, which also accommodate various subtropical liana species. A large number of trees and bushes can also be found on the sea dikes . The open dune ridges close to the sea are often desert-like in character and in some places are covered by extensive, fan-shaped sand dunes up to 250 meters long and ten meters wide and accommodate species adapted to the extreme drought. Lizard species live here, such as the desert racer, which also occurs in the Asian steppes, or insect species such as the ant lion . Riparian forests occupy six percent of the delta area. The willows, ash trees, alders, poplars and oaks that grow on high bank areas reach a height of up to 50 meters in places and are flooded at regular intervals. The rich flora of these forests also includes numerous climbing plants .

flora

In Dobruja, 50 percent of the approximately 3800 plant species cataloged in Romania grow; the delta and the lagoon complex host from 1839. The flora of the reserve is cataloged in 2383 taxa . The 955 species of vascular plants represent a mixture of Asian and European floral elements and include rare species such as Ephedra distachya , Carex colchica , Nymphaea candida or Convulvulus persica .

Swampy landscape

The swamp vegetation of reeds ( Phragmites australis ), cattails ( Typha angustifolia ) and rushes makes up about 70 percent of the delta vegetation and takes up 78 percent of the area of the delta suitable for vegetation. With about 1800 km² it is the largest contiguous reed area on earth. The reeds can reach a height of over six meters and have been growing here for around 8,000 years.

The swamps and the coastal lagoons are home to extensive fields of sea and pond rose, as well as a multitude of rare and protected plants such as the water nut ( Trapa natans ), European sea can ( Nymphoides peltata ), crayfish claws ( Stratiotes aloides ), swan flower ( Butomus umbellatus ) and water sword lily ( Iris pseudacorus) ). Other plants are: Bulrush ( Typha latifolia ), narrow-leaved cattail ( Typha angustifolia ), dioecious sedge ( Carex dioica ), stiff sedge ( Carex stricta ), rooted ledges ( Scirpus radicans ), Lakeshore Bulrush ( Scripus lacustris ), marsh iris ( Iris pseudocorus ), Water mint ( Mentha aquatica ), ash willow ( Salix cinerea ).

Floating islands

The reeds and rushes of the reserve form a thicket of roots ( rhizomes ), some as thick as trunk, above and below the surface of the water , which intertwine in the mud to form a dense tissue. Occasionally, parts of the dense root carpet detach themselves from their anchorage on the ground due to floods or due to gas escaping from rotten plant parts and form floating reed islands that can reach considerable size. The islands are called "Plaur", derived from the Slavic word "plavaty", German to swim . Reed islands can overgrow parts of lakes and lagoons and change their shape in the process.

In addition, there are islands firmly anchored to the ground, which are flooded during floods. The rich humus layer on the surface of the islands is a breeding ground for herbaceous plants , pit-worm ferns , mint , dwarf willows , climbing plants and wild hemp . This milieu offers good development opportunities for colonies of pelicans. Sedge , water hemlock , knotweed and the climbing plants Calystegia sepium and Solanum dulcamara also grow here .

River islands

The alluvial land is spread over three large river islands (Romanian: Grinduri ) :, the Letea Island , between the Chilia and Sulina arms, the Sfântu Gheorghe Island , between the Sulina and Sfântu Gheorghe arms and the Dranov Island , between the Sfântu-Gheorghe arm and the Razelm-Sinoie lagoon complex.

The islands consist of older loess layers on which sand is stored meters high, which gives the eastern part of these areas in particular a dune character. They are only originally forested in a few places, such as Letea and Caraorman. Willows are the most common tree species in alluvial forests . Due to the temporarily high water level, many secondary roots develop on their trunks. Willow trunks become hollow and are exposed to a process of putrefaction inside , which is accelerated by the action of fungi such as the sulfur pore. The infected trunks take on a yellow phosphorescent color and glow in the dark. Birds often find shelter in the human-sized hollows inside the willows.

Dike landscape

In river dike landscapes poplars grow as the forestry major bastard black poplar ( Populus x canadensis ) and the white poplars ( Populus alba ), and the gray poplar ( Populus canescens ) and aspen ( Populus tremula ). There are also willows such as the white willow ( Salix alba ), broken willow ( Salix fragilis ), purple willow ( Salix purpurea ), laurel willow ( Salix petandra ), almond willow ( Salix triandra ), blend willow ( Salix rubra ) and ash willow ( Salix cinerea ).

The common oak ( Quercus robur ), the narrow-leaved ash ( Fraxinus angustifolia ), the hairy ash ( Fraxinus pallisiae ) and the field elm ( Ulmus foliacea ) grow on the sea dykes . Representatives of the shrubs include the blackthorn ( Prunus spinosa ), the grooved hawthorn ( Crataegus monogyna ), the dog's rose ( Rosa canina ), the barberry ( Berberis vulgaris ), the common privet ( Ligustrum vulgare ), the heather Tamarisk ( Tamarix ramosissima ) and sea buckthorn ( Hippophae rhamnoides ). The climbing plants are represented by the wild grapevine ( Vitis sylvestris ), the ivy ( Hedera helix ), the real hops ( Humulus lupulus ) and the Greek tree snare ( Periploca graeca ).

Dune landscape

The Letea and Caraorman forests are covered in some places by sand dunes. Hardwood alluvial forests exist here , in which the gray oak, the English oak and the Balkan oak predominate. Next come swamp ash , alder, quivering poplar and elm .

The Letea Forest is the oldest nature reserve in Dobruja and is characterized by large oaks such as the gray oak . Other tree species are the silver poplar and the black poplar, the elm, the white willow, the alder and the ash . The Letea forest shows its tropical aspect with its large occurrences of lianas, in addition to which there are also other hanging plants such as wild grapevines , hops , ivy and bindweed , but also the Persian winds , sea ravages , the colch sedge and various types of lichen .

The sandy soil of the Caraorman forest is covered by an oak forest, the Turkish name of which means "Caraorman" means black forest . The largest oak tree in the reserve is located here. It is 400 years old and twelve meters in circumference. It is nicknamed "Kneeling Oak" because its branches reach to the ground. Their location is called Fântâna Vânătorilor (German: Jägerbrunnen ).

Other plants

Other plant species found in the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve are:

- Maple plants : Field maple ( Acer campestre ), Norway Maple ( Acer platanoides )

- Muskrat Family : Muskrat ( Adoxa moschatellina )

- Borage family : rock seeds ( Buglossoides arvensis ), brown monkweed ( Nonea erecta )

- Figworts : Toothwort ( Lathraea squamaria ), Ivy-speedwell ( Veronica hederifolia ), prostrate speedwell ( Veronica prostrata ), multipartite speedwell ( Veronica multifida )

- Beech family : Downy oak ( Quercus pubescens )

- Thick-leaf family : stonecrop ( Sedum )

- Umbelliferae : field litter ( Eryngium campestre ), Venus comb ( Scandix pecten-veneris )

- Smoke plants : Bulbous lark spur ( Corydalis cava ), firm bulbous lark spur ( Corydalis solida )

- Fever Clover Family : Common Gentian ( Nymphoides peltata )

- Goosefoot plants : prostrated cochlea ( Kochia prostrata ), steppe runner ( Salsola sp. )

- Honeysuckle family : Attich ( Sambucus ebulus ), Black elder ( Sambucus nigra )

- Buttercup family : Yellow anemone ( Anemone ranunculoides ), mussel flowers ( Isopyrum thalictroides ), celandine ( Ranunculus ficaria ), Illyrian buttercup (Ranunculus illyricus ), water crowfoot ( Ranunculus trichophyllus )

- Hazel family : Oriental hornbeam ( Carpinus orientalis )

- Dogwood family : Red hornbeam ( Cornus sanguinea )

- Dog poison plants : herbaceous periwinkle ( Vinca herbacea )

- Sunflower : wormwood ( Artemisia absinthium ), soft salsify ( Scorzonera mollis )

- Madder family : Common ragwort ( Cruciata laevipes ), Piedmontese ragwort ( Cruciata pedemontana )

- Herbaceous plants : sand winds ( Convolvulus persicus ), the sprouting timeless ( Merendera sobolifera ), orchid species such as the pyramidal dogwort ( Anacamptis pyramidalis ), the brown-red stendellum ( Epipactis atrorubens ) and the two-leaved forest hyacinth ( Platanthera bifolia )

- Cruciferous : steppe alyssum ( Alyssum desertorum ), Alyssum ( Aurinia saxatilis ) nodule-bearing tooth root ( Cardamine bulbifera ), Blue Mustard ( Chorispora tenella ), Sophie herb ( Descurainia sophia ), reveal mixed cress ( Lepidium perfoliatum ), stems Comprehensive Hellerkraut ( Thlaspi perfoliatum )

- Buckthorn family : piercing ( Paliurus spina-christi )

- Flax Family : Enduring flax ( Linum perenne )

- Lily family : Grape bisamhyacinth ( Muscari racemosum ), Milky Star ( Ornithogalum oreoides )

- Mint : deadnettle ( Lamium amplexicaule ), field deadnettle ( Lamium purpureum ), horehound ( Marrubium vulgare ), noble germander ( Teucrium chamaedrys )

- Poppy plants : Greater celandine ( Chelidonium majus ), gossip poppy ( Papaver rhoeas )

- Carnation family : Spurre ( Holosteum umbellatum )

- Oil willow family : Narrow-leaved oil willow ( Elaeagnus angustifolius )

- Orchids : monkey orchid ( Orchis simia )

- Rose family : Hawthorn ( Crataegus sp. ), Blackthorn ( Prunus spinosa )

- Primroses : extended man's shield ( Androsace elongata ), field man's shield ( Androsace maxima )

- Butterflies : Gleditschia , False Christ Thorn ( Gleditsia triacanthos ), Robinia ( Robinia pseudoacacia )

- Gooseberry family : golden currant ( Ribes aureum )

- Saxifrages : Dreifingeriger saxifrage ( Saxifraga tridactylites )

- Cranesbill family : common heron beak ( Erodium cicutarium ), soft cranesbill ( Geranium molle )

- Elm Family : field elm ( Ulmus minor )

- Violet family : steppe pansy ( Viola kitaibeliana )

- Walnut family : walnut tree ( Juglans regia )

- Duckweed family : triple furrowed duckweed ( Lemna trisulca )

- Water hose plants : water hose ( Utricularia sp. )

- Spurge family : Euphorbia myrsinithes ssp. Litardieriei

fauna

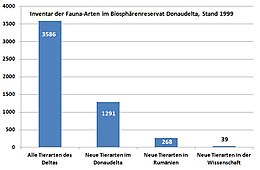

In the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve there are 4029 animal species , of which 3477 are invertebrates and 552 are vertebrates . Overall, around 98 percent of Europe's aquatic fauna live here.

Invertebrate representatives are:

- 2244 insect species

- 168 species of arachnids

- 115 species of crustaceans

- 91 species of molluscs

- 73 species of worms and rotifers

insects

Some of the orthopteric species found on the island of Caraorman (48) and on the island of Letea (33) are bound to a biotope. In damp places especially have been conocephalus discolor ( Conocephalus fuscus ), the Leek Grasshopper ( Parapleurus alliaceus ) and Chorthippus Loratus proven. The blue-winged wasteland insect ( Oedipoda caerulescens ), Costa's beautiful insect ( Calliptamus barbarus ), Omocestus minutus and the common nasal insect ( Acrida ungarica ) could be detected in dry places , while the green beach insect ( Aiolopus thalassinus ) could be observed in salt places .

The most famous mosquito is the malaria mosquito Anopheles maculipennis . Originally, the alluvial areas of the Danube, especially the delta area, were a notorious breeding ground for malaria . The disease was eradicated in this area as part of the Global Eradication of Malaria Program . The fight went in two directions: the comprehensive fight against the vectors and the comprehensive treatment of those suffering from malaria with effective drugs. The control of adult malaria mosquitoes was accomplished through the use of DDT . The goblin female from America , which became native to the vicinity of Mangalia and Bucharest , was introduced to eat the larvae and pupae bound to the water . The Anopheles mosquitoes , which still occur occasionally in the delta today, no longer carry any malaria pathogens and are therefore harmless. They can be recognized by their posture and their spotted wings. Under the flies, especially under the horseflies , individual specimens can reach a size of 15-20 millimeters.

In their larval state, the mite ticks ( Ixodida ) parasitize on reptiles, birds and small mammals. The adult ticks also attack larger mammals, including humans. The best-known species of tick is the common wood tick ( Ixodes ricinus ), which, when full, resembles a castor core in size and shape, according to its Latin name .

The European black widow ( Latrodectus tredecimguttatus ) is a venomous spider whose bite is painful and in exceptional cases can be fatal. The males of this spider are relatively small with a body length of five millimeters. The bodies of the females reach a length of 15 millimeters. They are velvety black and have red spots on their abdomen. The giant runner ( Scolopendra cingulata ), a centipede that can grow to over ten centimeters, can be found on the island of Popina.

fishes

More than 110 fish species live in the Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve, including 75 freshwater species .

A unique family among the fish of the Danube Delta are the saltwater sturgeon : the Sternhausen , the Hausen , the Danube sturgeon, from whose roe the black caviar is obtained, as well as the freshwater sturgeon : the sterlet and the smooth sturgeon . The most important representative of the sturgeon is the European Hausen ( Huso huso , also Riesenhausen ). During the spawning season it leaves its usual habitat in the Black Sea and penetrates to the spawning sites up to the Iron Gate . In past centuries sturgeons have been sighted upstream to Budapest , Bratislava and Vienna . Due to their poor adaptability, sturgeons are sensitive to physiological and ecological fluctuations. As a result of intensive fishing and pollution, the sturgeon population is falling. Ecological interventions in nature such as hydropower plants or dams are insurmountable obstacles for many sturgeon on the way to their spawning sites in the upper reaches of the river , despite fish migration aids such as fish ladders . Some sturgeon species have relocated their spawning areas to the coastal waters of the Black Sea and the lower reaches of the Danube. After spawning, the fish return to the sea. A year or two later, the brood follows them into the sea.

The Danube herring is the most important migratory fish in the region. A fully grown Danube herring weighs between 300 and 800 grams. The Danube catfish is considered to be the largest freshwater fish in Romania.

In stagnant water species of fish such as carp ( Cyprinus carpio ), Tench ( Tinca tinca ), bream ( Abramis brama ), perch ( Perca fluviatilis ) Pike ( Esox lucius ), Zander ( Lucioperca lucioperca ), Rudd ( Scardinius erytrophthalmus ) Silberkarausche , Brill ( Scophthalmus rhombus ), ( Carassius auratus gibelio ) and catfish . During spawning time, catfish leave their nooks and crannies hidden under roots and bank hollows and penetrate the delta lakes with the spring floods. A female lays between 50,000 and 200,000 eggs. When the water level falls, the catfish are the first to leave the lakes and return to the river system.

The Chinese sleeper gobies ( Perccottus glenii ), which normally live in the fresh waters of northern Vietnam , the People's Republic of China , Korea , Japan and the far east of Siberia , are also at home in the brackish waters of the Ukrainian estuaries, where individual specimens were first sighted in June 2011. They feed on carnivore and are substrate spawners . The clutch is guarded by the male. The fish were released as ornamental fish into the Eastern European river system at the end of the 19th century and have since spread further. In the Slovak part of the Danube and in Poland fell specimen as carriers of parasites ( Nippotaenia mogurndae on). Yuriy Kvach from the Institute of Biology of the Southern Seas of the National Academy of Science of Ukraine sees the spread of fish as a risk of these parasites being passed on to other fish in the delta.

Although there was an increase in stocks of species such as crucian carp, carp and bream ( Abramis brama ), overfishing in the reserve led to a sharp decline in stocks of sturgeon, pike, tench, catfish and pikeperch.

Amphibians

The amphibians are represented in the Danube Delta by the following species:

- European tree frog ( Hyla arborea )

- Little water frog ( Rana lessonae )

- Moor frog ( Rana arvalis )

- Sea frog ( Rana ridibunda )

- Agile frog ( Rana dalmatina )

- Pond frog ( Rana kl. Esculenta )

- Common toad ( Bufo bufo )

- Common spadefoot toad ( Pelobates fuscus )

- Syrian common toad ( Pelobates syriacus balcanicus )

- Green toad ( Bufo viridis )

- Danube crested newt ( Triturus dobrogicus )

- Pond newt ( Triturus vulgaris )

- European fire- bellied toad ( Bombina bombina )

Reptiles

Reptiles such as lizards (Lacertidae), snakes (Serpentes) and turtles (Testudinata) inhabit the forest areas and sand dunes. The most common representative of the water snake in the reserve is the dice snake . The smooth snake is native to the island of Letea in the actual delta , and the Aesculapian snake and the four-lined snake also live here. The only European giant snake, the western sand boa, lives in the south of the Dobruja, which no longer belongs to the actual delta . Venomous snakes such as sand otters and steppe otters can be found all over the delta. The Moorish tortoise ( Testuda graeca ) was recognized as a natural monument in 1938 .

Also live in the reserve:

- European pond turtles ( Emys orbicularis )

- Eastern green lizards ( Lacerta viridis )

- Giant emerald lizards ( Lacerta trilineata )

- Sand lizards ( Lacerta agilis )

- Taurian lizards ( Podarcis taurica )

- St. John's Lizard ( Ablepharus kitaibelii )

- Caspian angry snakes ( Coluber caspius ) and grass snakes ( Natrix natrix )

- Wall lizards ( Podarcis muralis )

- Slow worms ( Anguis fragilis )

- Arrow snakes ( Coluber caspius )

- Smooth snakes ( Coronella austriaca )

- Meadow viper ( Vipera ursinii ) and sand vipers ( Vipera ammodytes )

The meadow viper is a nationally and Europe-wide endangered species. The few surviving specimens could only be found in some protected areas of the reserve. The steppe runner ( Eremias arguta ) lived on the land arms of the Danube Delta, but has not been observed there since the 1990s.

Birds

The Danube Delta Biosphere Reserve offers around 325 species of birds in large numbers breeding and feeding places. 218 species nest in the Danube Delta, the remaining 109 species are only in transit in the Delta (autumn, winter and spring). The reserve lies at the intersection of six bird migration routes and is the largest resting area for migratory birds. Ornithologists regularly catalog new bird species here. In the delta there are three larger bird reserves (here especially the Roşca-Buhaiova-Hrecisca reserve ) and several small protection zones with the largest pelican colony in Europe. More than 7000 great white pelicans ( Pelecanus onocrotalus ) and 700 Dalmatian pelicans ( Pelecanus crispus ) live in the delta. The Dalmatian pelican (160–180 cm) and the great white pelican (140–175 cm) are the largest birds in the delta, weighing over 13 kilograms. The pelicans are the symbol of the reserve in Romania.

The protected areas Perisor-Zatoane and Periteasca-Leahova in the summer breeding areas for mute swans , geese and ducks , as from beyond the northern polar circle originating tailed duck ( clangula hyemalis ). Also cranes (Gruidae) and various species of herons (Ardeidae) breed here. The island Popina is a hotbed of shelduck ( Tadorna tadorna ). Numerous Nordic migratory birds overwinter in these areas. At Murighiol there are smaller protected areas for stilts and avocets . In Marhelova mixed heron colonies are native. Uzlina is home to pelicans (Pelecanidae, Pelecanus ), Istria water fowl .

In the standing water a plurality lives of birds: Tufted ( Aythya fuligula ), Moorente ( Aythya nyroca ), Kolbenente ( Netta rufina ), Mallard ( Anas plathyrhynchos ), gray goose ( Anser anser ), silver Heron ( Egretta alba ), Seidenreiher ( Egretta garzetta ), Gray heron ( Ardea cinerea ), night heron ( Ardea nycticorax ), great white pelican, Dalmatian pelican, mute swan ( Cygnus olor ) and the brown ibis ( Plegadis falcinellus ).

The red-necked grebe ( Gavia stellata ), the black-necked grebe ( Gavia arctica ), the little grebe ( Tachybaptus ruficollis ), the great crested grebe ( Podiceps cristatus ), the red-necked grebe ( Podiceps grisegena ) and the black-necked grebe ( Podiceps nigricollis ) are represented in the reserve.

Of the three species of cormorant found in Romania, only the cormorant ( Phalacrocorax carbo ) and the pygmy shag ( Phalacrocorax pygmeus ) can be found in the reserve . The herons are represented by the white heron, of which there are two types, the great egret and the little egret. Among the types of colorful Heron is heron ( Ardea cinerea ) to be found, as is the Purpurreiher ( Ardea purpurea ), the night Heron Rallenreiher ( ardeola ralloides ) and the dwarf Heron ( Ixobrychus minutus ). From the heron family, the bittern ( Botaurus stellaris ) and the little bittern ( Ixobrychus minutus ) can also be seen in the reserve. The spoonbills ( Platalea leucorodia ) also belong to the heron family, but differ from other types of heron in how they fly. The black stork ( Ciconia nigra ), which is almost as big as the white stork ( Ciconia ciconia ), is a rarity.

Swans are the largest geese in the reserve. The mute swan ( Cygnus olor ) and the dwarf swan ( Cygnus bewickii ) are most common, and whooper swans ( Cygnus cygnus ) also retreat from their northern nesting areas to the delta in winter .

About 95 percent of the world's red-necked geese ( Branta ruficollis ) population visit the delta in autumn . Further representatives of the geese are the common gray goose ( Anser anser ) and the white- fronted goose ( Anser albifrons ). Occasionally pygmy geese ( Anser erythropus ) and bean geese ( Anser fabalis ) also appear. In winter there are red-necked and white-fronted geese at Baia , Agighiol and Sarinasuf . The rust ( Tadorna ferruginea ) and shelduck ( Tadorna tadorna ) belong to a group that forms the transition between geese and ducks and combines characteristics of both species. Of these two species, the shelduck is more common. The rarer rust goose can be found in the vicinity of Istria.

The mallard ( Anas platyrhynchos ), the ancestor of the common domestic duck ( Anas platyrhynchos ), is common almost everywhere. In summer the teal ( Anas querquedula ) and the teal ( Anas crecca ) appear in the reserve. The shoveler ( Anas clypeata ), which belongs to the swimming ducks , can only be seen in autumn and spring during their migration. The body of the diving duck is broader, its beak and neck are shorter than those of the swimming ducks . During the summer they are represented by the bog duck ( Aythya nyroca ), the pochard ( Aythya ferina ) and the pochard ( Netta rufina ). In the cold season, tufted ducks ( Aythya fuligula ) and pygmy mergans ( Mergellus albellus ) also visit the mouth of the Danube. The wigeon ( Anas penelope ) and the gadfly ( Anas strepera ) as well as the pintail ( Anas acuta ), the mountain duck ( Aythya marila ), the eider ( Somateria mollissima ), the long-tailed duck ( Clangula hyemalis ), the velvet duck ( Melanitta fusca ) and the Schellente ( Bucephala clangula ) sighted.

A main route of the birds of prey migration in south-eastern Europe runs west of the Black Sea. Of the 37 species of birds of prey identified in Romania, 29 regularly visit the Danube Delta and the Razim-Sinoie lagoon area:

- Eagle Buzzard ( Buteo rufinus )

- Tree falcon ( Falco subbuteo )

- Osprey ( Pandion haliaetus )

- Goshawk ( Accipiter gentilis )

- Imperial eagle ( Aquila heliaca )

- Hen harrier ( Circus cyaneus )

- Kurzfangsperber ( Accipiter brevipes )

- Common buzzard ( Buteo buteo )

- Merlin ( Falco columbarius )

- Buzzard ( Buteo lagopus )

- Marsh harrier ( Circus aeruginosus )

- Red-footed falcon ( Falco vespertinus )

- Red kite ( Milvus milvus )

- Red hawk ( Falco naumanni )

- Greater spotted eagle ( Aquila clanga )

- Schlangenadler ( Circaetus gallicus )

- Egyptian vulture ( Neophron percnopterus )

- Lesser Spotted Eagle ( Aquila pomarina )

- Black kite ( Milvus migrans )

- White-tailed eagle ( Haliaeetus albicilla )

- Sparrowhawk ( Accipiter nisus )

- Golden eagle ( Aquila chrysaetos )

- Steppe harrier ( Circus macrourus )

- Kestrel ( Falco tinnunculus )

- Peregrine falcon ( Falco peregrinus )

- Honey buzzard ( Pernis apivorus )

- Montagu's Harrier ( Circus pygargus )

- Sucker falcon ( Falco cherrug )

- Booted eagle ( Hieraaetus pennatus )

The reserve is an important resting and reproduction area for migrating and breeding birds of prey. The Caraorman and Letea forest areas, along with the Măcin Mountains and the Babadag and Niculițel forest areas, provide a habitat for the region's often rare or endangered birds of prey. Many species are widespread here and sometimes in large numbers. Due to its high concentration of waterbirds, waders and small mammals , the Razim-Sinoie lagoon complex is particularly attractive to them. However, the population of birds of prey in the reserve declined sharply in the course of the 20th century; Goose and black vultures as steppe eagle died out here. Despite some stable breeding populations, which in the case of the eagle buzzard, are increasing, the populations of most species are steadily declining. Intensive agriculture and the associated use of pesticides destroyed the habitat for parts of the food chain of birds of prey. 22 of the bird of prey species found here are subject to European animal and nature conservation . The conditions for the survival of 19 species are unfavorable. 14 of them are considered 'Species of European Conservation Concern'. Greater spotted eagle, imperial eagle and red hawk are among the world's endangered bird species ; White-tailed eagles and steppe harriers are endangered species .

The most common chicken birds are the pheasants ( Phasianus colchicus ), which have been established several times since 1969 in the area around Letea, Caraorman, Sfântu Gheorghe, Maliuc and Rusca. Most of the pheasants live on the island of Letea, where they have developed into the characteristic birds of the sandy undergrowth there. The smallest chicken-like birds are the quail ( Coturnix coturnix ), which can be seen in large numbers on the coast, especially in spring.

Of the crane birds , the water rail ( Rallus aquaticus ) and the common crane ( Grus grus ) live in the reserve. Another, smaller species, the maiden crane ( Anthropoides virgo ), is a rare visitor here. Only a few pairs breed in the vicinity of the Sfântu Gheorghe arm. Other species are the coot ( Fulica atra ), the moorhen ( Gallinula chloropus ), the spotted moorhen ( Porzana porzana ), the small moorhen ( Porzana parva ) and the pygmy moorhen ( Porzana pusilla ). The corncrake ( Crex crex ) lives in the damp meadows.

Among the Schnepf birds of are avocet ( Recurvirostra avosetta ) and the stilt ( Himantopus himantopus ) represented in the reserve. They inhabit salt floor areas near Murighiol , the salt marshes of Plopu , the islands of Sakhalin and Letea . Other representatives of the snipe birds are the oystercatcher ( Haematopus ostralegus ), the Kentish plover ( Charadrius alexandrinus ), the lapwing plover ( Pluvialis squatarola ), the golden plover ( Pluvialis apricaria ). The most suitable place to observe snipe birds when they are migrating in North Dobruja is the meadow between Mihai Viteazul and Sinoie . Because of the woodcock ( Scolopax rusticola ), the Letea forest was once a royal hunting ground . The following are to be found:

- the lapwing ( Vanellus )

- the double snipe ( Gallinago media )

- the miniature snipe ( Lymnocryptes minimus )

- the godwit ( Limosa limosa )

- the curlew ( Numenius arquata )

- the Whimbrel ( Numenius phaeopus )

- the sandpiper ( Calidris ferruginea )

- the dunlin ( Calidris alpina )

- the ruff ( Philomachus pugnax )

- the Bekassine ( Gallinago gallinago )

- the common godwit ( Limosa lapponica )

The snipe birds prefer swampy, boggy areas. Also Rotschenkel ( Tringa totanus ), green leg ( Tringa nebularia ) and Philo pugnax may be encountered. In the vicinity of Murighiol-Plopu and the meadows of Istria one can occasionally see the red-winged curlew ( Glareola pratincola ). The Triel ( Burhinus oedicnemus ) prefers dry, sandy areas such as Letea, Caraorman, the Sakhalin Island, or the hills near Murighiol. The Marsh Sandpiper ( Limicola falcinellus ) can be seen in spring and autumn. The Dunlin ( Calidris alpina ), the Sickle Sandpiper ( Calidris ferruginea ), the Rusty Sandpiper ( Calidris canutus ) and the Odin's Grouse ( Phalaropus lobatus ) can also be found. The pygmy sandpiper ( Calidris minuta ) and the Temminck sandpiper ( Calidris temminckii ) were observed . Other species of snipe that have been sighted are:

- Dark water strider ( Tringa erythropus )

- Wood sandpiper ( Tringa glareola )

- Terek sandpiper ( Xenus cinereus )

- Pond sandpiper ( Tringa stagnatilis )

- Wood sandpiper ( Tringa ochropus )

- Wood sandpiper ( Tringa glareola )

- Sandpiper ( Actitis hypoleucos ), and turnstone ( Arenaria interpres )

The most common bird of the delta and the seashore is the black-headed gull . Other seagull species found in the reserve are:

- Arctic Skua ( Stercorarius parasiticus )

- Hawk sku ( Stercorarius longicaudus )

- Fish gull ( Larus ichthyaetus )

- Lesser black-backed gull ( Larus fuscus )

- Thin-billed gull ( Larus genei )

- Black- headed Gull ( Larus melanocephalus )

- Steppe gull ( Larus cachinnans )

- Mediterranean seagull ( Larus michahellis )

- Black-headed gull ( Larus marinus )

- Common Gull ( Larus canus )

The herring gull ( Larus argentatus ) and the little gull ( Larus minutus ) were also observed.

The Black Sea region is of great importance as a breeding, resting and wintering area for many water bird species. The wetlands also offer the waders a resting place on the Mediterranean Flyway during the migration between their breeding areas and their African winter quarters. The Razim-Sinoie lagoon system takes up more than 50,000 at the same time resting waders during the spring migration and more than 25,000 dabbling ducks a central position. 24 water and wading bird species regularly breed in the lagoon area, for many others it represents an important part of the annual habitat as a resting or wintering area. With a total of 33 species, the Danube delta and lagoon area accommodate more than 50 percent of the national breeding population. Including the wintering water birds and resting birds in autumn, the lagoon area is of international importance for numerous water and wading bird species.

The reserve formed an important habitat for the endangered curlew ( Numenius tenuirostris ) during its migration. It was last observed in the lagoon area in 1989, in the Ukrainian part of the Danube Delta in 1994 and 1996. The area is important for six other globally endangered aquatic and wader species: the white-headed oar duck, the little goose, the red-necked goose, the corncrake, the Dalmatian pelican and the bog duck. The dwarf shark was also listed as critically endangered by BirdLife International in 2000 . Almost all of the water and wading bird species that regularly occur in the Razim-Sinoie lagoon system are subject to the Bern Convention , 81 of them fall under the Bonn Convention , and a total of 98 species are in the Agreement for the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Water Birds (AEWA) under the Bonn Convention Convention taken into account.

The largest tern area is Sakhalin Island, where all species of the region can be found:

- Salmon tern ( Gelochelidon nilotica )

- Predatory tern ( Sterna caspia )

- Sandwich tern ( Sterna sandvicensis )

- Common tern ( Sterna hirundo )

- Arctic tern ( Sterna paradisaea )

- Little tern ( Sterna albifrons )

- Whitebeard Tern ( Chlidonias hybridus )

- Black Tern ( Chlidonias niger )

- White-winged tern ( Chlidonias leucopterus )

The pigeons that occur here in large numbers are mostly stock doves ( Columba oenas ) and wood pigeons ( Columba palumbus ).

Of the owls, the little owl ( Athene noctua ) is the most common. Other owl species that breed in the area are long-eared owls ( Asio otus ) and eagle owls ( Bubo bubo ), while short-eared owls ( Asio flammeus ) can only be seen in the reserve during the migration period.

The rocket birds (Coraciiformes) are represented by the bee-eater ( Merops apiaster ), the blue roller ( Coracias garrulus ), the hoopoe ( Upupa epops ) and the kingfisher ( Alcedo atthis ). Black woodpeckers ( Dryocopus martius ) and the common gray woodpeckers ( Picus canus ) live in the forests of Caraorman and Letea .

The songbird migration is concentrated on the western Black Sea coast, where migrants in the Danube Delta and in the Razim-Sinoie lagoon area find suitable resting habitats. The reserve is also of outstanding importance as a breeding ground for many species, especially for reed breeders and residents of open and semi-open habitats. However, many of the habitats are not adequately protected and are exposed to numerous hazards due to diverse usage requirements.

The member of the songbird family is the largest species of lark in Europe, the calender lark ( Melanocorypha calandra ), which is found mainly in the hilly region of Istria. Next come here bag chickadees ( Remiz pendulinus ), Rose Stare ( Sturnus roseus ) and the nistetenden the stork's nest of twigs willow sparrows ( Passer hispaniolensis ) ago.

In 2000, more than 25,000 songbirds were ringed, with which extensive data material on the phenology and biometry of species such as the reed warbler ( Acrocephalus ) was compiled, or interesting faunistic evidence could be provided with several catches of the reed warbler ( Acrocephalus dumetorum ). In systematic Beringungen in 1996 and delivered in 1997 four new records for Romania in the lagoon area Razim Sinoie and in the Danube Delta: desert warbler ( Sylvia nana ), Greenish Warbler ( Phylloscopus trochiloides ), Firecrest-warbler ( Phylloscopus proregulus ) and Isabelline Shrike ( Lanius isabellinus ).

In the years 1990–1996 the employees of the biological station Rieselfelder Münster, in cooperation with the ornithologists of the “Societatea Ornitologică Română” (SOR) and the “Danube Delta Research and Design Institute”, observed and documented a total of seven spring migrations. The aim of the activity was the systematic recording of the passing and resting Limikolen and water birds as well as the breeding birds of these species groups. The following songbird species were found to be regular guests in the Danube Delta and in the lagoon complex of the Romanian Dobruja:

- Short-toed Lark ( Calandrella brachydactyla )

- Woodlark ( Lullula arborea )

- Rock tern ( Ptyonoprogne rupestris )

- Red Swallow ( Hirundo daurica )

- Common pipit ( Anthus campestris )

- Tree pipit ( Anthus trivialis )