Celandine

| Celandine | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Greater celandine ( Chelidonium majus ), illustration |

||||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific name of the genus | ||||||||||||

| Chelidonium | ||||||||||||

| L. | ||||||||||||

| Scientific name of the species | ||||||||||||

| Chelidonium majus | ||||||||||||

| L. |

The celandine ( Chelidonium majus ) is a species of the genus Chelidonium of the poppy family (Papaveraceae). For some authors, the “greater celandine” is the only species from the family with several subspecies, other authors rate the subspecies from East Asia as two to three separate species.

description

Vegetative characteristics

The celandine is a deciduous, biennial to perennial herbaceous plant that reaches heights of up to 70 centimeters. It forms a branched rhizome . Their milky juice is yellow-orange.

The alternate leaves are divided into a petiole and a leaf blade. The green-gray leaf blade, which is frosted by a thin wax film, is notched. The underside of the leaf is lighter and slightly hairy ( trichomes ).

Generative characteristics

The flowering period extends from May to October. The hermaphrodite flowers are four-fold and about two centimeters in size. The two sepals fall off early. Its four petals are yellow. There are twelve to many free stamens . Two carpels have become an ovary grown. The stylus ends in a two-lobed scar. The thin, bilobed capsule fruit is about five centimeters long and contains few to many seeds. The egg-shaped, black seeds carry a cock-comb-shaped caruncula .

The number of chromosomes in Europe is 2n = 12, in Japan, in Chelidonium majus subsp. asiaticum H.Hara 2n = 10 or 12.

ecology

Greater celandine is a hygromorphic hemicryptophyte .

When the hairy stems break off or the leaves tear, a yellow-orange milky sap emerges from articulated milk tubes . The poisonous juice has a sharp, bitter and very unpleasant taste.

In cool, rainy weather, the flowers are closed and the flower stalks lower. The pollination is effected by insects ( Entomophilie ). There is also self-pollination .

The seeds are spread by ants ( myrmecochory ), which are attracted by the caruncula.

Occurrence

Originally, celandine was widespread in the temperate and warm-tempered areas of Eurasia and the Mediterranean . It was taken to North America by settlers who used it as a remedy for skin diseases and is therefore considered a neophyte there .

This nitrogen-loving species grows widespread in the vicinity of human dwellings, for example on rubble sites, at roadsides, in black locust trees and even in crevices, but also in the mountains .

The celandine occurs in Central Europe in societies of the order Glechometalia but also of the association Arction. In the Allgäu Alps, it rises in the Tyrolean part in the plain near Steeg up to 1250 m above sea level.

The ecological indicator values according to Ellenberg for Chelidonium majus are: L6 = penumbra to half-light plant, T6 = moderately warm to warm indicator, Kx = indifferent behavior, F5 = indicator of freshness, Rx = indifferent behavior, N8 = pronounced nitrogen indicator, S0 = does not bear salt.

Common names

From chelidonium the word scheliwurz developed in Old High German and from it Middle High German schëlwurz . The other common German names for celandine also exist or existed : Affelkraut ( Carinthia ), Augenkraut, Blutkraut ( Silesia ), Geschwulstkraut ( Austria ), Gilbkraut, Goldkreokt ( Transylvania ), Goldwoort ( Unterweser , Göttingen , Middle Low German ), Goldwurz ( Middle High German ), Goldwurzel ( Eifel ), Goltwort (Middle Low German), Gotsgab, Grindwurz (already mentioned in 1482), Grosgrau, Guldkreokt (Transylvania), Gutwurz, Herrgottsblatt, Jölk ( Altmark ), Jülk (Altmark), Lichtkraut, Maikraut, Nailwort ( Bern ), Ogenklar ( Ostfriesland ), Schälerlkraut (Austria), Schalerkraut ( Linz ), Sela (Middle High German), Sceli (Middle High German), Scellawurz ( Old High German ), Scelliwurz (Old High German), Scellinwurz (Old High German), Scelworz (Middle High German), Schelfiederworz (Middle High German), Schelfersworz (Region at the Hase ), Schelaw (Old High German), Schellewort (Middle Low German), Schellewurz (Middle High German), Schellchrut ( St. Gallen ), Sche llkraut, Schellkrokt (Transylvania), Scheltwurz (medium high German), Schelwort (Middle Low German), Schelwurz, Schiel herb ( Schwaben ) Schindkrut ( Mecklenburg , Rendsburgerstrasse pharmacy), Schinkrud ( Bremen ), Schinnefoot ( Westphalia ), Shin herb ( Prussia ), Schinnkrut ( Pomerania ), Schinnwart, Schinnwatersbläer, Schinkrut ( Low German ), Schöllkrut (Mecklenburg), Schöllwurz, Groß Schwalbenkraut, Schwindwurz ( Zillertal ), Tackenkrut ( Lübeck ), Truddemälch (Transylvania), Warty herb (Austria) and Würzekrokt (Transylvania).

Ingredients and their effects

Description of the ingredients

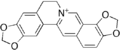

The celandine contains a number of alkaloids, over 20 of which have been isolated and chemically identified. The most important are berberine , chelerythrine , chelidonine , coptisine , sparteine , chelidoxanthin and sanguinarine . The alkaloids are present both in the above-ground parts of the plant and in the root. In autumn they concentrate in the root, which then becomes highly toxic.

The alkaloids are predominantly of the benzophenanthridine , protoberberine or protopine type , depending on their chemical structure , and are derived biogenetically from (-) - scoulerin , a benzyl isoquinoline . Among them, coptisin is the main alkaloid. Chelerythrine is the most potent. Some alkaloid salts are yellow or orange in color and give the milky sap its characteristic color. Furthermore, celandine contains proteolytic enzymes in the milk sap. Other ingredients of the plant are organic acids such as malic , citric and chelidonic acids, as well as caffeic acid esters and flavonoids .

Alkaloid analysis

The identification of the alkaloids is possible by thin layer chromatography or high performance liquid chromatography .

A thin-layer chromatographic analysis of the celandine alkaloids serves - in addition to the macroscopic and microscopic examination of the dried herb - the identification of celandine ( Chelidonii herba ) according to the European Pharmacopoeia . For this purpose, a test solution prepared according to the instructions is chromatographed on silica gel in addition to a reference solution containing methyl red and papaverine . The zone sequence obtained from the test solution is assessed in comparison with that from the reference solution after spraying with Dragendorff reagent and sodium nitrite solution .

Pharmaceutical qualities of celandine must contain at least 0.6 percent total alkaloids, calculated as chelidonin. The predominant chelidonium alkaloids in terms of quantity contain dioxymethylene groups, from which formaldehyde can be split off with strong acids (the pharmacopoeia method prescribes sulfuric acid) , which reacts with chromotropic acid to form a purple-red dye . This is measured quantitatively spectrophotometrically at 570 nm. Using the “specific absorption” for chelidonin, the amount is converted (“calculated as chelidonin”).

The celandine root ( Chelidonii radix ) is not monographed in the European Pharmacopoeia.

In vitro and in vivo effects

Celandine extracts have an in vitro antiviral , antibacterial , antifungal , anti-inflammatory and mildly toxic ( cytotoxic ) effect on human cells, which is attributed to the content of chelidonin, coptisin and protopin . Chelerythrine and sanguinarine are also cytotoxic. A weak effect against influenza viruses was found in vivo .

The following effects of isolated alkaloids are mentioned: antispasmodic ( spasmolytic ) on the smooth muscles and central sedative (chelidonine and protopine), choletic (berberine), weakly analgesic (chelidonine), central paralyzing and irritating to the mucous membrane (chelerythrine), AChE- inhibiting ( sanguine- inhibiting).

Fresh celandine is sometimes highly poisonous for animals. However, cases of poisoning are rare because of the unpleasant taste of the plant.

Effects in medical application

In folk medicine , the juice of the plant is used externally for skin diseases such as warts , either native or as an ointment ("Glaucionsalbe", Latin also "Glaucina" ). Protein-dissolving ( proteolytic ) and antiviral mechanisms are discussed as the principle of action . The juice and the ointment can be very irritating. However, if the juice is applied to a wart for several days, it can go away completely. The color begins to fade after a short time and repeated hand washing. However, the benefits are insufficiently documented in clinical studies.

Because of the papaverine-like, slightly spasmolytic and cholagogic effects of the alkaloids typical of chelidonium, preparations made from the herb drug are or were used internally for spasmodic complaints in the gastrointestinal tract and in the biliary tract.

Oral pharmacokinetic studies show that high concentrations of chelidonium alkaloids occur in the stool and only low concentrations in the liver. An accumulation in the liver was not observed. The excretion via the kidneys is low. The findings indicate that poor absorption, but not a high first-pass effect, is mainly responsible for the low systemic bioavailability . In particular, the resorption of the quaternary alkaloids (chelerythrine, sanguinarine) is estimated to be very low.

Medical efficacy for dosages with an intake of 2.5 milligrams of celandine total alkaloids or less has not been adequately proven.

- unwanted effects

After the dermal application of Chelidonium majus for the treatment of warts, the occurrence of contact dermatitis has been observed, which decreased after discontinuation of therapy.

Swallowing parts of the plant in large quantities leads to severe irritation of the gastrointestinal tract . Accordingly, the symptoms manifest themselves in burning, pain, increased salivation, vomiting , bloody diarrhea , weakness in arms and legs, dizziness and circulatory disorders such as accelerated breathing and increased pulse rate. In severe cases of poisoning, death from circulatory failure can occur.

Celandine is suspected of causing dose-dependent toxic liver damage ( hepatitis , cholestasis and even liver failure ) after internal use of therapeutic doses . Since 1993, new reports of suspected liver damage from preparations containing celandine have been made known.

A change in the assessment of the benefit-risk ratio can be seen in the documents that were created for companies and authorities to simplify approval procedures. After the publication of the positive monograph of Commission E in 1985, in which celandine and its preparations - average daily dose of 2-5 g of drug or 12-30 milligrams of total alkaloids - for the treatment of spasmodic complaints in the biliary tract and gastrointestinal tract Tracts were positively assessed, followed in 2003 by the adoption of a monograph by the European Scientific Cooperative on Phytotherapy (ESCOP). She also assessed the risk-benefit ratio as positive in the indication “slight cramps in the upper gastrointestinal tract, slight biliary complaints and dyspeptic complaints such as flatulence” and refers to preparations for adults and children from 12 years of age with a mean daily dose of 1.2–3.6 grams of crushed medicinal drug as a tea infusion and various extracts, including a standardized extract with 9–24 milligrams of total alkaloids (calculated as chelidonin ).

The Committee for Herbal Medicines (HMPC) of the European Medicines Agency, on the other hand, classified the risk-benefit ratio of celandine in preparations for internal use as negative in 2011: The data situation is for a “well-established-use” indication (“general medical use “) Not sufficient for monopreparations made from celandine. Even if one considers a daily dose of less than 2.5 mg total alkaloids as harmless, the benefit remains questionable. A “traditional application” is proven, but is not advocated because of the numerous reports of potential liver damage. A European harmonized monograph could therefore not be drawn up.

In 2005, the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices initiated a step-by-step procedure based on reports of hepatotoxic reactions with the aim of reducing the maximum permissible daily dose for total alkaloids from 2.5 mg to 0.0025 mg (ie 2.5 micrograms) and the approval of drugs withdraw with a higher dose. The safety factor of 1000 for the daily dose of 2.5 mg total alkaloids, which is safe according to studies, was justified with insufficient relevance of the studies for the long-term effects in humans. The authorities did not derive the proposed limit value from the available side effect reports , but based it on in vitro data on rat hepatocytes . In April 2008, the BfArM issued the step-by-step plan notification, which, however, deviated from the original plan insofar as the approval of celandine-containing medicinal products with a higher daily intake of now 2.5 milligrams of total alkaloids (calculated as chelidonin) would be revoked if a dosage was given between 2.5 micrograms and 2.5 milligrams of total alkaloids per day, however, warnings should be included in the package insert.

Celandine components are also said to be contained in the controversial cancer drug Ukrain .

history

etymology

Celandine goes back to Middle High German schëlkrūt , also called schëlwurz . The name “Chelidonium” was first mentioned by Dioscurides and Pliny . They differentiated between a "large Chelidonium" and a "small Chelidonium". According to Dioscurides and Pliny, the name is derived from the Greek word χελιδών chelidon , German 'swallow' , and refers to the fact that the chelidonium begins to bloom when the swallows arrive and wilts when the swallows leave. In 1976, however, it was precisely assumed that the original name was probably due to the common gray-blue color of certain species of swallow and a “herba chelidonia” (cf. Middle Latin celidonia ). "But there are other ways of interpretation".

In Gart health (1485), in small Destillierbuch of Hieronymus Brunschwig (1500) and by the fathers of botany "lesser Chelidonium" as was celandine ( Ficaria needle ), the "big Chelidonium" as celandine ( Chelidonium majus interpreted). In ancient times and in the Middle Ages, chelidonia minor can also refer to turmeric or a type of horned poppy such as red horned poppy or yellow horned poppy ( Chelidonium glaucium ).

Antiquity - late antiquity

Dioscurides and Pliny reported that the swallows used the juice of the chelidonion to heal their blind young. The juice of the "large chelidonium" mixed with honey was considered a remedy for "darkening the eyes". The root, when chewed, should relieve toothache. It was taken with white wine and aniseed for the treatment of jaundice ("icterici sive auriginosi") (cf. signature theory ). Large and small chelidonium were used externally to treat skin diseases, but the “small chelidonium” was used especially as an externally applied caustic agent. These indications were adopted by later authors. The indications mentioned in Dioscorides were also mentioned outside of the technical prose.

middle Ages

The doctors of the Arab Middle Ages also quoted from the works of Dioscurides.

In the Physica attributed to Hildegard von Bingen (12th century) it was stated that celandine contains a “dark and bitter poison” that is more harmful than useful to humans. However, when mixed with old lard, the celandine juice can heal internal ulcers.

In the German Macer (13th century), another application of celandine was stated: "The roots pounded with vinegar vnde that used with wisem wine help the giggling vunde růmet di brust."

In the printed versions of the little book on the burnt waters , ascribed to the Viennese doctor Michael Puff , which appeared in rapid succession from 1477 until well into the 16th century, a new indication was given for the distilled water obtained from celandine : “It is also good drunk for die bermůter. ”In the manuscripts that appeared before the printing and which served as a template for the printed“ Little Book of Burnt Waters ”, this addition was not included. Instead it said that the mother swallow would heal the eyes of her young with the juice of the celandine. In the 15th and 16th centuries, the name bermutter referred to menstrual cramps ("The uterus rises up and creates pain in the abdomen") but also generally cramp-like pain in the abdomen in women and men, in young and old.

From the second half of the 15th century, a recommendation can also be found, according to which flowering celandine should be placed in a sevenfold distilled wine together with cumin . A small amount of the resulting tincture should be mixed with two-thirds of wine every morning. This potion should be used for disease prevention and long life in health. In addition to the golden women's hair moss and the sundew , the celandine in particular was used by some alchemists to represent the materia prima and the aurum potabile . The selection criterion was the golden-yellow color of the celandine juice. They interpreted the name “chelidonium” as “donum coeli - heavenly gave”.

Sources of the Latin Middle Ages:

Modern times

16th Century

The fathers of botany also interpreted the “smaller chelidonium” as celandine ( Ficaria verna ) and the “large chelidonium” as celandine ( Chelidonium majus ). They adopted the indications for celandine from their predecessors. Hieronymus Bock divided these indications into:

- Internally: to open the liver in jaundice, to heal infectious diseases ("pestilentz")

- Externally: as eye medication, against stains on the face and "pestilentzblattern", to divert serous or fibrinous exudates ("limb water") caused by joint inflammation or injuries, to treat poorly healing wounds ("fistulas" and "cancer"), toothache , Stomach grief , warts in the anal and genital region ("feigwartzen")

Sources from the 16th century (selection):

17th and 18th centuries

In 1768 Jacques-Christophe Valmont de Bomare wrote in the revision of his Dictionnaire raisonné :

- "This plant, 4 to 5 onces [approx. 120 to 150 g] prepared and taken as an infusion in water or whey, has a diuretic effect [- diurétique -] and it is suitable for releasing blockages of the spleen, liver and ureter and especially for curing jaundice caused by thickening of the Lymph has arisen in the vessels. (The celandine cures jaundice by making the bile in the bile ducts fluid.) It is also said that celandine use is harmful if the jaundice is caused by liver inflammation, or by an acute illness such as convulsions or a bite Viper was caused. It is also claimed that the juice of the celandine ingested expels poison through sweat. But you can only take a moderate amount of it, because the juice is so hot that it often causes terrible symptoms. "

Further sources from the 17th and 18th centuries (selection):

19th century

Mathieu Orfila , the founder of modern toxicology , reported in 1815 on experiments in which he administered aqueous extracts or the juice from celandine leaves internally and externally to dogs. Orfila realized that celandine and its extract, both internal and external at the dosages he used, cause violent accidents with fatal consequences. He also found that celandine and its preparations also act on the lungs. From the second third of the 19th century, the newly discovered ingredients of celandine, especially its alkaloids , were the subject of toxicological studies.

Chelidonin . In 1824 the Parisian chemist JP Godefroy noticed an alkaloid while examining the celandine, which he called "chélidonine". When Leo Meier repeated the analysis steps given by Godefroy in Königsberg in 1827, however, he did not find an alkaloid. The discovery of chelidonin was attributed to JMA Probst , who made it pure in 1839. The pharmacist Reuling in Umstadt found after a self-experiment in 1839: “Chelidonin has little or no narcotic effect. Five grains [approx. 0.3 g] sulfuric acid chelidonin ingested only produces a bitter, salty, scratchy, pungent taste ”.

Chelerythrine - Sanguinarine . In 1839, JMA Probst made the alkaloid chelerythrine from the celandine and the yellow horn poppy . In 1842 Jacob Heinrich Wilhelm Schiel (1813–1889) stated that the American chemist James Freeman Dana (1793–1827) made it from the Canadian roots in 1828 Bloodweed ( Sanguinaria canadensis ) represented sanguinarine is identical to Probst's chelerythrine. In 1869 Ludwig Weyland tried sanguinarine (chelerythrine) in animal experiments on the frog. According to Husemann (1871 and 1883), 0.06 g of the alkaloid known as chelerythrine and sanguinarine caused vomiting in humans, and 0.001 g subcutaneously killed frogs and 0.02 g rabbits. Symptoms of poisoning resulted in adynamia and clonic or even tonic convulsions . Death resulted from paralysis of the respiratory center . Small doses increased the pulse rate and blood pressure, while large doses reduced it by paralyzing the vasomotor center and the heart.

Chelidonic acid . While investigating the herb and the roots of the celandine, JMA Probst discovered chelidonic acid in 1839. Lerch (1846), Hutstein (1851) and Wilde (1863) subsequently published the results of their research on this vegetable acid.

In 1831, the Berlin doctor Emil Osann specified the following forms and dosages for the medical use of celandine:

- 1. usually as an extract from the herb (Chelidonii herba) dissolved in water or in pill form.

- According to the third edition of the official Prussian Pharmacopoeia from 1804, celandine extract was obtained only with water as an extractant. From the fourth edition onwards, the instructions for preparing the celandine extract have been changed so that alcohol is added after the juice mixed with water has been squeezed out. This made the extract water-alcoholic. In the German Pharmacopoeia published in 1872 , a regulation for the production of an aqueous-alcoholic celandine extract was given.

- The recommended dosages were given very differently. For the aqueous extract, Pfaff (1821) recommended a dosage of five to ten grains (approx. 0.3 to 0.6 g) and Link / Osann (1831) a dosage of half a drachm to a whole drachm (approx. 8 to 3.6 g).

- The extract was used internally for "congestion in the liver and portal vein system" with hardening of the liver, gallstones, hemorrhoidal complaints ..., for "dropsy due to congestion and weakness of the organs of the abdomen", for "three- and four-day alternating fever" and for skin rashes (" scrofulous and venereal dyscrasias ")

- 2. Less often the freshly squeezed juice from the herb and / or from the root.

- According to Link / Osann (1831), the dose was a scruple (approx. 1.2 g) to one drachma (approx. 3.6 g) two to three times a day together with other herbal remedies ( dandelion , earth smoke , couch grass ) as a spring cure for "blood purification"

- The freshly squeezed celandine juice was also used on warts and genital warts.

- The fresh herb was used as a poultice for the treatment of "flaccid ulcers" and for the resorption of foot edema.

A tinctura chelidonii made from celandine was a major liver product of the Rademacher school and was given in 5–20 drops 3–4 times a day.

20th to 21st century

Celandine is suspected of causing dose-dependent toxic liver damage ( hepatitis , cholestasis and even liver failure ). The first reports of suspected liver inflammation caused by medicinal products containing celandine extract were made in 1993 and announced in 1998. See the following table for the chronology of the side effect reports and their accompanying circumstances:

| Authority - institution - company | Chronology of side effect reports and their accompanying circumstances |

| Commission E of the former Federal Health Office | In May 1985, Commission E of the former Federal Health Office published a positive monograph on celandine (Chelidonii herba), in which the herb and its preparations were approved for the treatment of spasmodic complaints in the biliary tract and gastrointestinal tract, with contraindications, Side effects and interactions were reported as "not known". |

| Drugs Commission of the German Medical Association (AkdÄ) | In October 1998 the Medicines Commission informed the German medical profession that eight cases of hepatitis had been registered in their database since 1993 after the administration of preparations containing celandine extract, and that a suspicion of a medicinally toxic cause must therefore be expressed. |

| Medicines Commission of the German Medical Association | In November 2002, the drug commission of the German medical profession had over 60 reports on chelidonium preparations in its database for adverse drug reactions (ADRs), more than 40 relating to “liver damage”. Fatal liver failure was reported in one case. Since more effective substances are available for the effects claimed by chelidonium preparations, the Medicines Commission advised against the use of celandine extracts. |

| Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM) | In April 2008, the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices ordered that the approval of celandine-containing drugs, for which more than 2.5 milligrams of total alkaloids (calculated as chelidonin ) per daily dose can be administered according to the dosage instructions in the package insert, be revoked. If the dosage instructions in the package insert are between 2.5 micrograms and 2.5 milligrams, detailed warnings should be included in the package insert. The Steigerwald Arzneimittel company filed an objection to this order and did not adapt the instructions for use of its gastrointestinal drug "Iberogast" accordingly. |

| Steigerwald Arzneimittel | In May 2008, the Steigerwald company announced that the recommended daily dose of 60 "Iberogast" drops had taken 0.25 milligrams of total alkaloids. |

| European Medicines Agency EMA | In its assessment report published in September 2011, the European Medicines Agency (EMA) certified that celandine and the preparations made from it generally had a negative benefit-harm ratio and recommended that the group of people to be treated and the amount of recommended daily doses be restricted. This also applies to daily doses below 2.5 milligrams of total alkaloids. |

| Bayer takes over Steigerwald | In July 2013, the phytopharmaceutical manufacturer Steigerwald and with it its product “Iberogast” was taken over by Bayer AG. |

| Swissmedic | In January 2018, the Swiss Medicines Institute, Swissmedic, included a warning about liver damage such as acute liver failure and hepatitis in the package insert and in the specialist information for the celandine-containing drug "Iberogast". |

| Bayer Vital GmbH | In September 2018, the manufacturer Bayer Vital GmbH also added detailed warning notices to the “Iberogast” package insert.

In June 2019, the Cologne public prosecutor's office started investigations against unknown persons. The reason was a death that occurred in the spring of 2018, which was linked to the consumption of "Iberogast". It was questionable whether this death could have been prevented by earlier information on the package insert. |

Historical illustrations

Great Chelidonium ( Chelidonium majus )

Pseudo-Apuleius Leiden 6th century

Vitus outlet 1479

Herbarius Moguntinus 1484

Garden of Health 1485

Otto Brunfels 1532

Leonhart Fuchs 1543

Small Chelidonium ( Ranunculus ficaria )

Vitus outlet 1479

Garden of Health 1485

Otto Brunfels 1532

Leonhart Fuchs 1543

literature

- Karl Daniel, Dieter Schmalk: The celandine (= medicinal plants in individual representations. 1). Stuttgart 1939.

- Dumont's great herbal encyclopedia. DuMont, Cologne 1998, ISBN 3-7701-4607-7 .

- Gustav Hegi (first), Friedrich Markgraf (Hrsg.): Illustrated flora of Central Europe. Volume 4, part 1, 2nd edition. Carl Hanser Verlag, Munich 1958.

- Kerstin Hoffmann-Bohm, Elisabeth Stahl-Biskup, Piotr Gorecki: Chelidonium. In: Rudolf Hänsel , K. Keller, H. Rimpler, G. Schneider (Eds.): Hagers Handbook of Pharmaceutical Practice. 5th edition. Springer, Berlin, Volume 4: Drugs A – D. (1992), pp. 835-848. ISBN 3-540-52631-5 .

- Robert W. Kiger: Chelidonium majus . In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee (Ed.): Flora of North America North of Mexico. Volume 3: Magnoliidae and Hamamelidae. Oxford University Press, New York / Oxford 1997, ISBN 0-19-511246-6 .

- Gerhard Madaus : textbook of biological remedies. Thieme, Leipzig 1938, Volume II, pp. 916–927: Chelidonium (digitized version )

- Oskar Sebald: Guide through nature. Wild plants of Central Europe . ADAC Verlag, Munich 1989, ISBN 3-87003-352-5 .

Web links

- Giuseppe Mazza, Eugenio Zanotti: data sheet. (monotypical)

- Shiro Tsuyuzaki: Plant ecology - Environmental Conservation. Hokkaido University: data sheet. (monotypical)

- Celandine . In: BiolFlor, the database of biological-ecological characteristics of the flora of Germany.

- Profile and distribution map for Bavaria . In: Botanical Information Hub of Bavaria .

- Chelidonium majus L. In: Info Flora , the national data and information center for Swiss flora . Retrieved October 22, 2015.

- Distribution in the northern hemisphere according to: Eric Hultén , Magnus Fries: Atlas of North European vascular plants 1986, ISBN 3-87429-263-0 .

- Thomas Meyer: Data sheet with identification key and photos at Flora-de: Flora von Deutschland (old name of the website: Flowers in Swabia )

- awl.ch/heilpflanze - Celandine.

- Celandine - Profile of the Maria Laach Monastery Nursery . Accessed July 31, 2019.

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b c d e Chelidonium majus L., celandine. In: FloraWeb.de.

- ↑ Gustav Hegi (original), Friedrich Markgraf (Hrsg.): Illustrated flora of Central Europe. 2nd Edition. Volume IV, Part 1, 1958, pp. 24-26.

- ^ Erich Oberdorfer : Plant-sociological excursion flora for Germany and neighboring areas . With the collaboration of Angelika Schwabe and Theo Müller. 8th, heavily revised and expanded edition. Eugen Ulmer, Stuttgart (Hohenheim) 2001, ISBN 3-8001-3131-5 , pp. 424-425 .

- ↑ Erhard Dörr, Wolfgang Lippert : Flora of the Allgäu and its surroundings. Volume 1, IHW, Eching 2001, ISBN 3-930167-50-6 , p. 564.

- ^ Georg August Pritzel , Carl Jessen : The German folk names of plants. New contribution to the German linguistic treasure. Philipp Cohen, Hannover 1882, p. 90. (online)

- ↑ a b Maria L. Colombo, Enrica Bosisio: Pharmacological activities of Chelidonium majus L. (Papaveraceae). In: Pharmacological Research . Volume 33, 1996, pp. 127-134.

- ↑ a b c d E. Teuscher: Biogenic drugs. 5th edition. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, 1997. ISBN 3-8047-1482-X . P. 325 f.

- ↑ a b c T. Dingermann, Karl Hiller, G. Schneider, I. Zündorf: Schneider drug drugs. 5th edition. Elsevier, 2004. ISBN 3-8274-1481-4 . P. 466 ff.

- ↑ A. Petruczynik, M. Waksmundzka-Hajnos, T. Michniowski, T. Plech, T. Tuzimski, ML Hajnos, M. Gadzikowska, G. Józwiak: Thin-layer chromatography of alkaloids on cyanopropyl bonded stationary phases. Part I. In: J Chromatogr Sci. 45 (7), Aug 2007, pp. 447-454. PMID 17725873

- ^ Y. Gu, D. Qian, JA Duan, Z. Wang, J. Guo, Y. Tang, S. Guo: Simultaneous determination of seven main alkaloids of Chelidonium majus L. by ultra-performance LC with photodiode-array detection. In: J Sep Sci. 33 (8), Apr 2010, pp. 1004-1009. PMID 20183823

- ↑ a b European Pharmacopoeia, 8th edition, basic work, p. 2060 ff.

- ↑ a b c Assessment report on celandine from September 13, 2011 (PDF; 527 kB), Committee for Herbal Medicines of the European Medicines Agency (English).

- ^ [1] Danger of liver damage from celandine, communication Joint Poison Information Center of the states of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia from June 1, 2011, accessed on May 29, 2020

- ↑ Warts: What Really Helps Them? ( Memento from February 9, 2010 in the Internet Archive ) ARD : Advice on Health (BR) from September 13, 2009.

- ^ Karl Ernst Georges : Comprehensive Latin-German concise dictionary. Unchanged reprint of the eighth improved and increased edition. 1. Volume, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, Darmstadt 1998, p. 2939. (Reprint of the Hanover edition: Hahnsche Buchhandlung, 1913), at www.zeno.org.

- ↑ https://www.deutsche-apotheker-zeitung.de/daz-az/2014/daz-21-2014/bitte-geduld

- ↑ https://www.deutsche-apotheker-zeitung.de/daz-az/2005/daz-27-2005/uid-14234

- ↑ Etxenagusia MA, Anda M, Gonzalez-Mahave I, Fernandez E, Fernandez de Corres L .: Contact dermatitis from Chelidonium Majus (greater celandine). Contact Dermatitis 2000, 43:47.

- ↑ Wesselin Denkow: Poisons of nature. Ennsthaler Verlag, Seyr, 2004; ISBN 3-8289-1617-1 , p. 96.

- ↑ ESCOP monographs. The Scientific Foundation for Herbal Medical Products. 2nd edition, Thieme, New York 2003, p. 74 ISBN 1-901964-07-8

- ↑ H. Blasius: How does celandine work and what about the clinical evidence? , DAZ.online, September 14, 2018.

- ↑ [2] Reinhard Kurth: Hearing on celandine medicinal products for internal use from May 6, 2005, communication from the Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices, accessed on May 29, 2020

- ↑ Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM): Defense against dangers from drugs, level II here: Medicines containing celandine for internal use - notification (pdf). April 9, 2008, accessed June 2, 2020 .

- ↑ Jürgen Martin: The 'Ulmer Wundarznei'. Introduction - Text - Glossary on a monument to German specialist prose from the 15th century. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1991 (= Würzburg medical-historical research. Volume 52), ISBN 3-88479-801-4 (also medical dissertation Würzburg 1990), p. 168.

- ↑ Julius Berendes : Des Pedanius Dioskurides medicament theory in 5 books. Enke, Stuttgart 1902, Book II, Cap. 211, Large Chelidonium (digitized version)

- ↑ Julius Berendes: Des Pedanius Dioskurides medicament theory in 5 books. Enke, Stuttgart 1902, Book II, Cap. 212, Small Chelidonium (digitized version)

- ↑ Naturalis historia . Edition Külb 1840–1864 German. Book VIII, § 98 (Chapter XLI) (digitized version) . Book XXV, § 89 (Chapter L) (digitized version) ; Section 172 (Chapter CIX) (digitized version) . Book XXVI, § 24 (Chapter XII) (digitized version) ; § 141 (Chapter LXXXVII) (digitized version ) ; § 152 (Chapter XC) (digitized version)

- ↑ Cf. on this Barbara Fehringer: The "Speyerer Herb Book" with Hildegard von Bingen's medicinal plants. A study on the Middle High German “Physica” reception with a critical edition of the text. (= Würzburg medical historical research. Supplement 2). Würzburg 1994, p. 89 (“Pliny: The script daz die swalben, wan the ir boys the eyes are stung or are sust blint that they make them with disem crut against the sighted. Dis krut hept also knew, so they swalben comment, and wurt also durre, if they fly away again: And that's why dis krut has a name, called celidonia from the bird of the swallows, which in krieschem is called celidon ”).

- ↑ Helmut Genaust: Etymological dictionary of botanical plant names. Birkhäuser, Basel / Stuttgart 1976, ISBN 3-7643-0755-2 , p. 107 f.

- ^ Friedrich Kluge , Alfred Götze : Etymological dictionary of the German language . 20th edition, ed. by Walther Mitzka , De Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1967; Reprint (“21st unchanged edition”) ibid 1975, ISBN 3-11-005709-3 , p. 642 ( celandine ).

- ^ Willem F. Daems: Nomina simplicium medicinarum ex synonymariis medii aevi collecta. Semantic studies of the specialist vocabulary of high and late medieval drug customers. (= Studies in ancient medicine. 6). Leiden / New York / Cologne 1993, pp. 115 and 283.

- ↑ Ulrich Stoll: De tempore herbarum. Vegetable remedies as reflected in herbal collection calendars from the Middle Ages: an inventory. In: Peter Dilg, Gundolf Keil, Dietz-Rüdiger Moser (eds.): Rhythm and Seasonality. Congress files of the 5th symposium of the Medievalist Association in Göttingen 1993. Sigmaringen 1995, p. 356 f.

- ↑ Julius Berendes : Des Pedanius Dioskurides medicament theory in 5 books. Enke, Stuttgart 1902, Book II, Cap. 211, Large Chelidonium (digitized) ; Book II, cap. 212, Small Chelidonium (digitized version)

- ↑ Pliny : Naturalis historia . Edition Külb 1840–1864 German. Book VIII, § 98 (Chapter XLI) (digitized version) . Book XXV, § 89 (Chapter L) (digitized version) ; Section 172 (Chapter CIX) (digitized version) . Book XXVI, § 24 (Chapter XII) (digitized version) ; § 141 (Chapter LXXXVII) (digitized version ) ; § 152 (Chapter XC) (digitized version)

- ↑ Galen (2nd century). De simplicium medicamentorum temperamentis ac facultatibus. (Adapted from Kühn 1826, Volume XII, p. 156.) Chelidonium (digitized version)

- ^ Pseudo-Apuleius . (4th century), printed Rome 1481, Herba Celidoniae (digital copy )

- ↑ See for example: Bernhard Dietrich Haage: Celandine in the 'Parzival' Wolframs von Eschenbach (Pz. 516, 21-27)? In: Leuvense Bijdragen. Volume 96, 2007-2010, pp. 121-129.

- ↑ Avicenna : Canon of Medicine (11th century). Edition Andrea Alpago, Basel 1556, Volume II, Cap. 738 (p. 319) Vena tinctorum digitized Vena tinctorum (= Vena citrina) after Hermann Fischer. Medieval botany . Munich 1929, pp. 264, 305.

- ↑ Constantine the African ( Ibn al-Jazzar ) (11th century). De Gradibus . Print edition Basel 1536, p. 381 (digitized version)

- ↑ Approximately instans . De simplicibus medicinis. (12th century). Print Venice 1497, sheet 195v, Celidonia (digital copy )

- ↑ Hildegard von Bingen . 12th century Physica I / 138: Grintwurtz. Edition. Charles Victor Daremberg and Friedrich Anton Reuss (1810–1868). S. Hildegardis Abbatissae Subtilitatum Diversarum Naturarum Creaturarum Libri Novem. Migne, Paris 1855. Sp. 1185–1186 (digitized version ) based on the Paris manuscript. Liber beate Hildegardis subtilitatum diversarum naturarum creaturarum et sic de aliis quam multis bonis. Paris. Bibliothèque Nationale. Codex 6952 f. 156-232. Complete handwriting. 15th century (1425-1450). Translation (Herbert Reier. Hildegard von Bingen Physika (1150-1157). Translated into German from the text edition by JP Migne, Paris 1882. Kiel 1980, p. 40): Grintwurtz is very warm and contains poisonous juice. It has such a dark and bitter poison in it that it cannot be of any benefit to human health, because if it were to bring health to man in one respect, it would on the other hand only cause him a greater illness inside. When someone eats or drinks it, it ulcers and harms them internally, and so at times causes pain and discomfort in man, both in solution and in digestion. But if you eat, drink or touch something unclean, which causes ulcers in the body, take old lard, add plenty of grint root juice to it, crush it so that it dissolves in a bowl. Then he smeared himself with the sebum and will heal.

- ↑ Heidelberg, cpg 226, Alsace 1459–1469, sheet 198v (digitized version )

- ^ German Macer . Critical edition with extensive bibliographical information. Bernhard Schnell and William Crossgrove. The German Macer. Vulgate version. With an impression of the Latin Macer floridus "De virtutes herbarum". Issued critically. Niemeyer, Tübingen 2003, p. 362 ISBN 3-484-36050-X

- ↑ output Bämler, Augsburg 1478 (digitized)

- ↑ For example Solothurn, Codex 386 (1463–1466), sheet 134r (digitized version )

- ^ Matthias Lexer. Concise Middle High German dictionary. Ber-muoter ... uterus, colica ... (digitized)

- ↑ Nikolaus Frauenlob . Pharmacopoeia. Heidelberg, Cpg 583, Südwestdeutschland 1453–1483, sheet 10v (digitized version ) . Transcription: That the man albeg fresh and healthy peleib Man sal celidonia so green with the juice and plüedt put in the wine as ir he knows a water of the body haisset and the jne vij paints by raynen gleser distilled it and also puts Ciminum so verbet in it the water will be seen as e and the same water will sult ir all tomorrow with wine ain a little of the water in a glass When how the water the third were as the wine I do not want to be distorted that is good and helps for all visibility and illness how they are called and baked pej heals man and that he is fresh and healed and happy and that man is not an ordinary person for was. --- Heidelberg, Cpg 666, Südwestdeutschland 1478, sheet 118v (digitized version ) . Transcription: a That the human being fresh and healthy pleibe Man sal celestial herb so green jn the juice and jn the plut jn put the wine who is the water of life and to be sipped by dÿ gleser be stilled and there lays a zÿminum so forbids it water as ir worth seeing vnd the same water salt jr use a little with wine every morning jn a glaz when wy daz water the third part were than the wine i don't want to spoil it daz is good and helps against all sighting and kranckheyt knows sy gnante sey vnd keeps people fresh and healthy and because they are alzeyt frolicky and gloomy and people are not old.

- ↑ Hieronymus Brunschwig : Liber de arte distillandi de compositis. Strasbourg 1512, sheet 27va. Quinta essentia from the krut called Celidonia. (Bavarian State Library digitized)

- ↑ Macer floridus . (11th century). Printed in Basel 1527 (digitized version)

- ^ Prüller herbal book . (12th century) Friedrich Wilhelm. Monuments of German prose. Munich 1960, Volume I, pp. 42-43; Volume II, p. 108. Scellewurze soch [juice]. Clm 536 digital copy, sheet 86r.

- ↑ Hildegard von Bingen : Physica . (12th century) Book I, Chapter 138. Grintwurtz. Book I, Chapter 207. Ficaria.

- ^ Franz Pfeiffer (ed.). Konrad von Megenberg . Book of nature . Stuttgart 1861, p. 390. (digitized version )

- ↑ Gabriel von Lebenstein (14th century) Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Clm 5905 (2nd half of the 15th century), sheet 55r (digitized version ) . Transcription: celandine waſſer. Water is good for the eyes. Who nympts a little honey to it and makes it ain plater and legs over the eyes ſo draws it out to all ſmerces out all red and praises all patter in the eyes. Whom dy prague tint yn the eyes of nem the water and paint it up on prague. Who ain winniger Hundt peeks it with the water. To whom the oren wanted ſand that he didn't belong, the trauff the waſſer yn dy oren ſo dewell ſi ym. Who pluet runst be the drink that waſſer ſo verſtet it ym. [In the reference manuscripts »Wolfenbüttel. Herzog August Bibliothek, Cod. 54 Aug. (1st quarter of the 15th century) "and" London. Wellcome Institute of the history of Medicine, MS 283 (end of the 15th century) ”, this sentence is missing. In the manuscript »Brno. Stadtarchiv, Cod. St. Jacob 110 (around 1500) «it reads: Whoever plut runst sey be the trinckh. ] To whom the main wee do the necz ain tuech dar yn vnd pincz vmb the main ſo he is geundt.

- ↑ Michael Puff : Booklet of the burnt-out waters . (15th century) Chapter 62. Schelwurtz. Printed in Augsburg (Johannes Blaubirer) 1481 .

- ↑ Nikolaus Frauenlob : Pharmacopoeia. (15th century) Celidonia schelkrawtt manuscript census . Frauenlob, Nikolaus: Pharmacopoeia . Cpg 583, sheet 10v (digitized version ) ; Cpg 666, sheet 118v (digitized version ) . Celidonia, schelkrawtt.

- ↑ Herbarius Moguntinus . Mainz 1484. Cap. 44. Celidonia, Schelwortz (digitized version )

- ↑ Gart der Gesundheit . Mainz 1485. Edition Augsburg (Schönsperger) 1485. Cap. 9: Apium emorrhoidarum fickblater eppich (digital copy ) ; Cap. 85: Celidonia schelwortz (digitized version )

- ↑ Hieronymus Brunschwig: Small distilling book. Strasbourg 1500, sheet 50r, Fick wartzen krut (digitized version ) , sheet 106r, Schelwurtz (digitized version )

- ↑ Dieter Lehmann: Two medical prescription books of the 15th century from the Upper Rhine. Part I: Text and Glossary. Horst Wellm, Pattensen / Han. 1985, now at Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg (= Würzburg medical-historical research. Volume 34), ISBN 3-921456-63-0 , p. 180 f.

- ↑ Jürgen Martin: The 'Ulmer Wundarznei'. Introduction - Text - Glossary on a monument to German specialist prose from the 15th century. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 1991 (= Würzburg medical-historical research. Volume 52), ISBN 3-88479-801-4 (also medical dissertation Würzburg 1990), p. 131 ( gelitwazzer ).

- ↑ Hieronymus Brunschwig. Small distilling book . Strasbourg 1500, sheet 106r. ... E. --- Otto Brunfels. Contrafeyt Kreueterbuch . Strasbourg 1532, p. 133 Schölwurtz ... His strength ... He who was sore ...

- ↑ Lorenz Fries . Mirror of the remedy. 1518, sheet 181v: Von fistulen vnnd dem krepß (digitized version )

- ↑ Otto Brunfels. Contrafeyt Kreueterbuch. Strasbourg 1532, p. 132, Schölwurtz (digitized version )

- ↑ Otto Brunfels. Contrafeyt Kreueterbuch. Strasbourg 1532, p. 176: Fygwartzenkraut (digitized version )

- ↑ Hieronymus Bock. New Kreütter book. Strasbourg 1539, book I, cap. 33, Schölwurtz (digitized version )

- ↑ Hieronymus Bock: New Kreütter book. Strasbourg 1539, book I, cap. 35, Feigblatern Eppich (digitized version )

- ↑ Leonhart Fuchs. New Kreütterbuch. Strasbourg 1543, Cap. 333, Schölkraut (digitized version )

- ^ Leonhart Fuchs: New Kreütterbuch. Strasbourg 1543, Cap. 334, fig wort herb (digitized)

- ↑ George Handsch (translation) and Joachim Camerarius the Younger (processing). Kreutterbuch Desz highly learned and well-known Mr. D. Petri Andreae Matthioli. Frankfurt 1586, sheet 206: Schölwurtz (digitized version )

- ↑ Jacques-Christophe Valmont de Bomare . Dictionnaire Raisonné Universel D'Histoire Naturelle: Contenant L'Histoire Des Animaux, Des Végétaux Et des Minéraux, Et celle des Corps célestes, des Météores, & des autres principaux Phénomenes de la Nature; Avec L'Histoire Et La Description Des Drogues Simples Tirées Des Trois Regnes; Et le détail de leurs usages dans la Médecine, dans l'Economie domestique & champêtre, & dans les Arts & Métiers . Didot, Paris 1764, Volume I, p. 553 (digitized version)

- ^ Albrecht von Haller , Jaques-Antoine-Henri Deleuze (1732-1774) and Nicolas-Maximilien Bourgeois (eds.). Jacques-Christophe Valmont de Bomare: Dictionnaire Raisonné Universel D'Histoire Naturelle: Avec plusieurs articles nouveaux & un grand nombre d'additions sur l'Histoire naturelle, la médecine, l'économie domestique & champêtre, les arts & les metiers. Yverdon 1768, Volume III, pp. 3–4 (digitized version)

- ↑ Johann Schröder . Pharmacopoeia medico-chymica: sive thesaurus pharmacologicus, quo composita quaeque celebriora; hinc mineralia, vegetabilia & animalia chymico-medice describuntur, atque insuper principia physicae Hermetico-Hippocraticae candide exhibentur ... Görlin, Ulm 1644, book 4, chapter 90 (p. 43): Chelidonium majus (digitalisat)

- ^ Johann Schröder and Friedrich Hoffmann. Johann Schröder's excellently provided medicin-chymische pharmacy: or: most valuable Arzeney treasure ... Nuremberg 1685 (digitized version )

- ↑ La Pharmacopée raisonnée de Schroder. Commentée by Michel Ettmuller . T. Amaulry, Lyon 1698, Volume 1, pp. 139–142: Chelidonium majus (digitized version )

- ↑ Nicolas Lémery . Dictionnaire universel des drogues simples, contenant leurs noms, origines, choix, principes, vertus, étymologies, et ce qu'il ya de particulier dans les animaux, dans les végétaux et dans les minéraux , Laurent d'Houry, Paris, 1699, p 187–188 (digitized version )

- ↑ Complete Lexicon of Materials . Complete material lexicon. Initially drafted in French, but now after the third edition, which has been enlarged by a large [...] edition, translated into high German / By Christoph Friedrich Richtern, [...]. Leipzig: Johann Friedrich Braun, 1721. Sp. 296–296 (digitized version )

- ^ Albrecht von Haller (editor). Onomatologia medica completa or Medicinisches Lexicon which explains all names and artificial words which are peculiar to the science of medicine and pharmacists art clearly and completely [...]. Gaumische Handlung, Ulm / Frankfurt am Main / Leipzig 1755, columns 388–389 (digitized version )

- ^ Antoine François de Fourcroy . Chelidoine . In: Encyclopédie méthodique . Charles-Joseph Panckoucke , Paris 1792, Médecine , Volume 4: Thérapeutique ou Matière médicale , pp. 684–685 (digitized version )

- ^ Mathieu Orfila . Traité des poisons tirés des règnes mineral, végetal et animal, ou toxilogie générale, considérée sous les rapports de la physiologie, de la pathologie et de la médecine légale . Crochard, Paris 1814-1815. Volume II, Part 1, 1815, pp. 68–70: De la Chélidoine (digitized version )

- ^ Sigismund Friedrich Hermbstädt (translator). General toxicology or poison science: in which the poisons of the mineral, plant and animal kingdoms from the physiological, pathological and similar. medico-judicial aspects are examined. After the French of Mr. MP Orfila . Amelung, Berlin 1818, Volume III, pp. 72–75 (digitized version ) (1 drachma = approx. 3.6 g)

- ^ JB Henkel (translator). Handbook of poison theory for chemists, doctors, pharmacists and court officials by AWM van Hasselt . Vieweg, Braunschweig 1862, part I General poison theory and the poisons of the plant kingdom . Pp. 254–255 (digitized version )

- ↑ August Husemann and Theodor Husemann : The plant substances in chemical, physiological, pharmacological and toxicological terms. For doctors, pharmacists, chemists and pharmacologists. Springer, Berlin 1871, pp. 197-199: Chelidonin (digitalisat) , pp. 782-786: Chelidonic acid. Chelidonic acid. Chelidoxanthin. (Digitized version)

- ^ Theodor Husemann. Handbook of the entire pharmacology. Springer, Berlin, 2nd edition, Volume II (1883), pp. 839–840 (digitized version )

- ^ JP Godefroy. Sur les plantes nommées Chelidonium Majus et Chelidonium Glaucium . In: Journal de Pharmacie et des Sciences Accessoires . Volume X (1824), pp. 635–644 (digitized version )

- ↑ Godefroy. Observations and experiments on Chelidonium majus and Chelidonium Glaucium . (Excerpt from the Journal de Pharmacie, December 1824.) In: Magazin für Pharmacie and the sciences involved. 3rd year, Volume 9, pp. 274–279 (digitized version )

- ^ Leo Meier (Königsberg). Chemical analysis of the leaves of the greater celandine . In: Berlinisches Jahrbuch für die Pharmacie , F. Oehmicke, Berlin, Volume XXIX (1827), Issue 1, pp. 169–232 (digitized version )

- ↑ Gustav Polex. About chelidonine and pyrrhopine . In: Archiv der Pharmacie , 2nd series, Volume XVI (1838), pp. 77–83 (digitized version )

- ↑ Dr. Probst. Description and method of representation of some of the substances newly discovered during the analysis of Chelidonium majus . In: Annalen der Pharmacie , Volume XXIX (1839), pp. 113–131, here: pp. 123–128 (digitized version )

- ↑ Heinrich Will . Composition of chelidonin and jervin . In: Annals of Chemistry and Pharmacy , Volume XXXV (1840), pp. 113–119 (digitized version )

- ↑ M. Chastaing. Chimie organique. Alcaloïdes naturels. Chélidonine. In: Edmond Frémy (ed.): Encyclopédie chimique . Volume VIII. Dunod, Paris 1885, pp. 176–177 (digitized version )

- ^ GLW Reuling, pharmacist in Umstadt. Chelidonin . In: Annalen der Pharmacie , Volume XXIX (1839), pp. 131–135: Chelidonin (digitized version )

- ^ Sanguinarine, a new organic alkali in Sanguinaria canadiensis . From Dana. In: Philipp Lorenz Geiger (Hrsg.): Magazine for pharmacy and the sciences involved . 6th year (1828) Volume XXIII, p. 124 (digitized version)

- ↑ Dr. Probst. Description and method of representation of some of the substances newly discovered during the analysis of Chelidonium majus . In: Annalen der Pharmacie , Volume XXIX (1839), pp. 113–131, here: pp. 120–123 (digitized version ) --- Description and method of representation of some peculiar substances found during the investigation of the Glaucium luteum, as a material contribution to a comparative one Analysis of the Papaveraceae . In: Annalen der Pharmacie , Volume XXXI (1839), pp. 241–258, here: pp. 250–254 (digitized version )

- ↑ Squint. About the Sanguinarin . In: Annals of Chemistry and Pharmacy . Volume XLIII (1842), pp. 233-236 (digitized version ) --- Sanguinarine identical to chelerythrine . In: Journal for practical chemistry . Volume LXVII (1856), p. 61 (digitized version)

- ↑ Ludwig Weyland. Comparative studies on veratrine, sabadillin, dolphinine, emetine, aconitine, sanguinarine and potassium chloride . Brühl, Giessen 1869 (Inaug. Diss.). P. 18–19 and P. 31–34: Sanguinarin (digitized version )

- ↑ M. Chastaing. Chimie organique. Alcaloïdes naturels. Chélérythrine . In: Edmond Frémy (ed.): Encyclopédie chimique . Volume VIII. Dunod, Paris 1885, pp. 172–176 (digitized version )

- ↑ August Husemann and Theodor Husemann : The plant substances in chemical, physiological, pharmacological and toxicological terms. For doctors, pharmacists, chemists and pharmacologists. Springer, Berlin 1871, pp. 199-202: Chelerythrine. Sanguinarin. (Digitized version)

- ^ Theodor Husemann. Handbook of the entire pharmacology. Springer, Berlin, 2nd edition, Volume II (1883), pp. 839–840 (digitized version )

- ↑ Dr. Probst . Description and method of representation of some of the substances newly discovered during the analysis of Chelidonium majus . In: Annalen der Pharmacie , Volume XXIX (1839), pp. 116-120: Chelidonic acid (digitized version)

- ^ Joseph Udo Lerch (1816-1892). Investigation of chelidonic acid . In: In: Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie , Volume LVII (1846), pp. 273-318 (digitized version )

- ↑ J. Hutstein in Breslau. Representation of chelidonic acid . In: Archives of Pharmacy . Second series volume LXV (1851), pp. 23–24 (digital copy)

- ↑ C. Wilde. About chelidonic acid . In: Annalen der Chemie und Pharmacie , Volume CXXVII (1863), 2nd issue pp. 164–170 (digitized version )

- ↑ August Husemann and Theodor Husemann : The plant substances in chemical, physiological, pharmacological and toxicological terms. For doctors, pharmacists, chemists and pharmacologists. Springer, Berlin 1871, pp. 782-786: Chelidonic acid . Chelidonic acid. Chelidoxanthin. (Digitized version)

- ↑ Pharmacopoea Borussica or Prussian Pharmacopoé. Translated from Latin and accompanied by comments and additions by Dr. Carl Wilhelm Juch . Stein, Nuremberg 1805, p. 220 (digitized version)

- ↑ Prussian Pharmacopoeia. Fourth edition. Translation of the Latin original . F. Plahn, Berlin 1827, pp. 166–167 (digitized version )

- ↑ Pharmacopoea Germanica . R. Decker, Berlin, p. 110: Extractum Belladonnae (digital copy ) , p. 114: Extractum Chelidonii (how to prepare Extractum Belladonnae) (digital copy)

- ↑ Christoph Heinrich Pfaff . System of the materia medica: according to chemical principles with regard to the sensual characteristics and the healing conditions of the medicinal products; for doctors and chemists. Vogel, Leipzig 1821, Volume VI, pp. 412-414: Greater celandine (digital version )

- ^ Heinrich Friedrich Link and Emil Osann . Chelidonium . In: Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Medicinal Sciences . Published by the professors of the Medical Faculty in Berlin: Dietrich Wilhelm Heinrich Busch , Carl Ferdinand von Graefe , Christoph Wilhelm Hufeland , Heinrich Friedrich Link, Karl Asmund Rudolphi . JW Boike, Berlin, 7th volume (1831), pp. 422–425 (digitized version )

- ^ Theodor Husemann . Handbook of the entire pharmacology. Springer, Berlin, 2nd edition, Volume II (1883), pp. 839–840 (digitized version )

- ^ Johann Gottfried Rademacher . Justification of the intellectual empirical teaching of the old, divorced secret doctors, misunderstood by the scholars, and faithful communication of the result of 25 years of testing this teaching on the sickbed . 2nd edition 1846, Volume I, pp. 163-180: Celandine Chelidonium (digitized version ) ; Volume II pp. 778–779: Tinctura Chelidonii (digital copy )

- ^ Positive monograph by Commission E, published in the Federal Gazette on May 15, 1985

- ↑ Deutsches Ärzteblatt 1998; 95 (44): A-2790 / B-2249 / C-2045: From the UAW database of the AkdÄ

- ↑ Deutsches Ärzteblatt 2002; 99 (47): A-3211 / B-2707 / C-2523

- ↑ Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices (BfArM): Defense against dangers from drugs, level II here: Medicines containing celandine for internal use - notification (pdf). (PDF) April 9, 2008, accessed July 25, 2019 .

- ↑ arznei telegram 2015; 46: 31-2 March 20, 2015

- ↑ Letter from Steigerwald Arzneimittelwerke to arznei-telegramm dated May 5, 2008. Quoted in arznei-telegramm 2008; 39: 95-7 (digitized version )

- ↑ EMA: Assessment Report on Chelidonium majus, herba, as of September 2011 (pdf), pp. 39-40 . Quoted from arznei-telegram 2015; 46: 31-2 Liver damage from Iberogast? Note 7

- ↑ EMA documents: Chelidonii herba

- ^ Pharmaceutical newspaper May 21, 2013. Bayer wants to take over Steigerwald

- ↑ Pharma + Food July 5, 2013. Bayer completes takeover of Steigerwald

- ↑ swissmedic. HPC - Iberogast tincture. January 18, 2018 - Risk of liver damage: adaptation of the drug information

- ↑ arznei-telegram, February 16, 2018. Liver damage under "Iberogast"

- ↑ BfArM risk assessment procedure. Medicines containing celandine for internal use. Amendment from October 01, 2018

- ↑ arznei-telegram, August 2019 (digitized version)