Ottoman Constitution

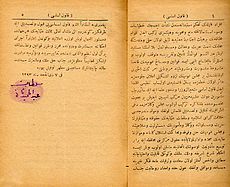

The Ottoman Constitution ( Ottoman قانون اساسی İA Ḳānūn-ı Esāsī , German 'Basic Law' ; French Constitution ottomane ) of December 23, 1876 was the first and together with the constitutional law of 1921 (“double constitutional period”) the last written constitution of the Ottoman Empire . The core of the Basic Law, which emerged in the wake of constitutionalism in the 19th century, was the introduction of a bicameral parliament and thus the path to a constitutional monarchy . The Sultan gave up the sole exercise of certain rights ("voluntary self-restraint"), but continued to determine the fate of his subjects through legislation and, in particular, through his unrestricted right of banishment from Art. 113 sentence 3.

After the closure of parliament in February 1878, Sultan Abdülhamid II ruled - for over thirty years - as absolute monarch until the forced convocation of parliament in July 1908 . The constitution remained formally in force and was largely applied. Only parliament was no longer convened. With the constitutional amendment of August 1908, the system of the constitution developed into a parliamentary monarchy. Between 1921 and 1923, the constitution , including its appendix and amendments, was gradually overridden by the constitutional law passed by the Grand National Assembly chaired by Mustafa Kemal Pasha . After the founding of the Republic of Turkey , the constitution of April 20, 1924 finally came into force on May 24, 1924 , repealing the Ottoman Basic Law.

Constitutional history

Alliance treaty

In 1807, the Janissaries, led by Kabakçı Mustafa , revolted and dethroned the "infidel Sultan" Selim III. who tried to reorganize the army with the help of European instructors ( Nizâm-ı Cedîd ), and set Mustafa IV as ruler. This intended to reverse previous reforms, whereupon Alemdar Mustafa Pascha from Rustschuk marched with his army to Istanbul . In order to thwart his impending disempowerment, the Sultan issued the death warrant for Selim and Mahmud . While Selim was being killed, Mahmud - next to Mustafa now the only legitimate heir to the throne still alive - managed to escape the executioners and ascend the throne on July 28, 1808. Alemdar Mustafa Pasha himself became the Sultan's Grand Vizier .

At that time, between the central power and regional rulers ( aʿyān , derebey ) in Anatolia and Rumelia there were "states of spite and discord". The Grand Vizier invited those landlords to talks in the capital, where they were accepted on September 29, 1808. According to contemporary reports, the participants arrived in Istanbul with 70,000 soldiers of their own and were housed outside the city. On October 7, 1808, they signed the so-called Alliance Treaty (سند اتفاق / Sened-i İttifāḳ , also 'Document of Unanimity, Alliance Pact'), through which the Sultan renounced his control over the life and property of the Aʿyān and Derebeys . The document granted - like the Magna Carta to the nobility in England - the landlords basic freedoms vis-à-vis the Ottoman rulers. In return, they recognized the central power and expressed their loyalty to the Sultan.

On November 14, 1808, Alemdar Mustafa Pascha was killed in a janissary uprising. To secure his throne, Mahmud II reacted by killing his half-brother and predecessor Mustafa, who was in the Kafes . With the death of Alemdar Mustafa Pasha, the driving force behind Sened-i İttifāḳ. the treaty , which was considered the first step towards a constitutional monarchy and was usually placed at the beginning of Turkish constitutional history, had in fact lost its validity. Eventually, later grand viziers also refused to sign the document with a substantive constitutional character.

Edict of Gülhane

After the death of Mahmud II, he was succeeded on July 2, 1839 by his son Abdülmecid I on the throne. In accordance with his father's explicit instructions, he set about implementing the reforms to which Mahmud had devoted himself. On November 3, 1839, Foreign Minister Mustafa Reşid Pascha , the "father of the Tanzimat ", read in Gülhane Park an edict that he had developed and which is an Ottoman continuation of the French declaration of human and civil rights (خط شريف / Ḫaṭṭ-ı Şerīf / 'sublime handwriting'), with which an era of fundamental reforms (تنظيمات خيریه / Tanẓīmāt-ı Ḫayrīye / 'benevolent ordinances'). The handwriting contained the basic lines of this reorganization and guaranteed the protection of "the life, honor and property of the population" regardless of religious affiliation. The Sultan also assured the public of legal proceedings , the fair distribution of taxes, and the reduction of military service to four to five years.

In the formal sense, this decree was not a constitution and also not an enforceable right. Nevertheless, the Ḫaṭṭ-ı Şerīf of 1839 played an important role in the constitutional development of the empire, especially since it is viewed as a promise of the later constitution.

Renewal Decree

The Renewal Decree of the Sublime Porte (خط همايون / Ḫaṭṭ-ı Hümāyūn / 'Grand Manorial Handwriting') was proclaimed on February 18, 1856, 18 days after the armistice in the Crimean War . He confirmed and developed the reforms of Gülhane.

The alleged aim of the letter was the complete equality between Muslim and non-Muslim subjects ( dhimma ) by dissolving the Millet system and granting Ottoman subordination to all religious communities. Non-Muslims were given access to state posts and admission to military schools, which had been denied until then, except for Millet-i Rum (“Greek nation of faith”). The state also strived for equality with regard to the taxes to be paid (cf. Dschizya ) . In keeping with this equality, handwriting determined that the same rights also entail the same obligations. For example, non-Muslims were now subject to military service, but could provide a substitute for exemption or a military tax (اعانهٔ عسكریه / iʿāne-ʾi ʿaskerīye , laterبدل عسكری / bedel-i ʿaskerī ).

As a result of handwriting, the Greek Orthodox, Armenian Orthodox and Jewish religious communities drew up provisions to regulate their own (mainly administrative and religious) affairs, with which their own parliaments were formed. These provisions (officially Rum Patrikliği Nizâmâtı of 1862, Ermeni Patrikliği Nizâmâtı of 1863 and Hahamhâne Nizâmâtı of 1865) were dubbed the “constitution” (constitution) by them and in the West . Krikor Odian , co-author of the Armenian “national constitution” ( Ազգային սահմանադրութիւն Azgayin sahmanadrowt'iwn ), later worked as an advisor to the committee for the Ottoman constitution.

Constitution

First constitutional period

In the years 1875 and 1876 in the broke Herzegovina and Bulgaria riots (see April Uprising ) from. In terms of foreign policy, the palace approached Russia , which, however, promised the rebels support. A protest in mid-May 1876 against this rapprochement led, among other things, to the dismissal of the Grand Vizier Mahmud Nedim Pasha and the replacement of the highest posts. Mütercim Mehmed Rüşdi Pascha was raised to Grand Vizier, Hasan Hayrullah Efendi to Sheikhülislam and Hüseyin Avni Pascha to Minister of War . This put together with Midhat Pasha , the Chairman of the State Council , the ruler Abdülaziz from May 30, 1876, his nephew Murad Mehmed Efendi as Murad V. a. In the days that followed, fundamental differences of opinion between Hüseyin Avni Pasha, who spoke out against a constitution, and constitutional supporter Midhat Pasha led to a split. Grand Vizier Rüşdi Pasha spoke out in favor of Avni Pasha and took the view that the adoption of a constitution in view of Murad V's mental disorders was inappropriate and out of the question. On June 15, 1876, Hüseyin Avni Pasha was shot and stabbed to death by a supporter of the deposed and murdered Abdülaziz during a meeting in the house of Midhat Pasha .

On June 30, 1876, the principalities of Serbia (see Serbian-Ottoman War ) and Montenegro declared war on the Ottoman Empire. Meanwhile, Great Britain pressed for a conference to prevent an impending Russo-Ottoman war and to give the insurgents greater autonomy. In order to counteract any foreign interference and such a "threat to break off the top", Midhat Pasha urged the early proclamation of a constitution that would come into force before the planned conference and grant all Ottoman subjects equal rights.

In order to be able to depose the sick Murad V, Midhat Pasha took up talks with his brother Abdülhamid and offered him the throne on condition that the constitution was accepted. When Abdülhamid announced that he would adopt the new constitution, he was brought to the throne on August 31, 1876 as Abdülhamid II . The new sultan took his time to keep his promises, in particular the convening of a constitutional committee, but ultimately consented to further pressure from Midhat Pasha.

A first advisory committee, which was to determine the further course of action and which included 20 ulamas and higher state officials, was convened by imperial decree on September 30, 1876. Midhat Pasha chaired the meeting. Midhat Pasha's 59 articles "New Law" (قانون جديد / Ḳānūn-ı Cedīd ) and Said Pasha's draft based on the translation of French constitutional laws (those of 1848 and 1852 ). Since there were also constitutional opponents among the committee members, there were violent disputes, which were also reported in the press. Only one week after it was founded, the Council of Ministers therefore decided to dissolve the existing committee and to convene a new one. On October 8, 1876, the names of the members of the Constitutional Committee, also known as the "Special Committee", were announced. The number of members is given in a variety of sources as 28: two military, ten ulama and 13 Muslim and three Christian officials. In fact, the commission initially consisted of 25 people (on October 15, 1876 the number rose to 33, on November 4, 1876 to 38) chaired by Server , but more likely Midhat Paschas. In order to be able to work more efficiently, working groups have been formed, for example for regulations regarding administration.

In addition to the aforementioned works by Midhat and Said Pasha, Süleyman Hüsnü Pascha's "Basic Law" (قانون اساسی مسوده سی / Ḳānūn-ı Esāsī Müsveddesi ) and possibly the Belgian and Prussian constitution . At the request of the Sultan, the draft constitutional drafts (there were three) were submitted to selected officials in the Yıldız Palace , such as Mütercim Mehmed Rüşdi Pascha , and the Council of Ministers for revision. The last draft was completed on December 1, 1876 and approved by the Council of Ministers on December 6. In the Yıldız Palace, however, they insisted on the sultan's right of banishment. Thus Art. 113, through which the Sultan was granted this right of exile with sentence 3, was incorporated into the constitution. This development caused outrage among some members of the special committee, particularly the young Ottomans Namık Kemal Bey and Ziya Pascha . Midhat Pasha, who pushed for the constitution to be proclaimed, finally succeeded in appeasing the angry minds. On December 19, 1876 he was appointed Grand Vizier.

On December 23, 1876, the constitution came into force by imperial decree and appeared in French as well as in Turkish. Foreign Minister Saffet Pasha interrupted the ongoing conference in Constantinople and declared, accompanied by 101 gun salutes , that a new constitution would be proclaimed that would equate all Ottoman subjects and guarantee them their rights and freedoms.

The great powers and conference participants, above all the Russian envoy General Ignatjew , remained suspicious of the Ottoman Empire and viewed the constitution as a sham solution. On February 5, 1877, the ruler deposed Midhat Pasha and made use of his right to banish him for the first time. Almost eleven weeks later, the ongoing Balkan crisis led to the Russo-Ottoman War , which ended with the defeat of the Ottoman Empire and, from a Turkish perspective, the disastrous preliminary peace of St. Stefano (partially revised by the Berlin Treaty of July 13, 1878).

Already two weeks after the armistice of Edirne , Abdülhamid II, who feared that parliament would hold himself personally responsible for the defeat, took the opportunity to justify an "extraordinary political crisis" and closed the parliament for an indefinite period of time. The Sultan announced the closure (تعطيل / taʿṭīl orقپادلمه / ḳapadılma ) of Parliament against dissolution (فسخ / fesḫ ) and in this way avoided holding the planned new elections, cf. Art. 7, 73. A convocation (عقد / ʿAḳd orدعوت / daʿvet ) and the wording of Art. 43, 7 after required disclosure (اچلمه / açılma orکشاد/ küşād ) of the parliament was absent in November 1878 and in the following period. Although the constitution did not formally expire and was printed in the annual Imperial Almanac, the ruler, who feared attacks and therefore increasingly withdrew to the Yıldız Palace, reigned in the following three decades with the help of the secret police, which was in fact subordinate to him, and the expansion of the Espionage and informers absolutist about the empire. Midhat Pasha, the "father of the constitution", was strangled by soldiers on May 8, 1884 in Ta'ifer exile on the orders of Abdülhamid II .

Second constitutional period

Young Turkish Revolution

On July 3, 1908, the officer Ahmed Niyazi Bey , who was involved in a conspiracy against the absolutist regime of Abdülhamid II and feared that this involvement would be exposed, went into the mountains with 200 or 400 armed men and openly demanded that the constitution be reinstated . He received support from the Committee for Unity and Progress under the leadership of Enver Bey , from the Armenian Revolutionary Federation and from Albanian, Greek and Bulgarian communities. The Young Turkish Revolution initiated by Ahmed Niyazi Bey took place in Macedonia , especially in the Vilayets of Kosovo, Monastir and Saloniki. In response, the Sultan dispatched Şemsi Pasha , who was supposed to move against Ahmed Niyazi Bey with his 18th division, but was shot by the young Turk Atıf Bey on July 7th . In order to accommodate the rebels, the Sultan now dismissed his Grand Vizier Mehmed Ferid Pasha and on July 22nd appointed Mehmed Said Pasha , whose translations of the French constitutional texts had been taken into account in the drafting of the constitution in 1876. However, there were only monarchists in his cabinet.

On July 23, 1908, the Committee for Unity and Progress proclaimed "Freedom" at demonstrations with large numbers of participants in several cities in Macedonia (حريت / ḥürrīyet ). At the same time, news arrived in Istanbul saying that the constitution had to come into force again within 24 hours, otherwise the Second and Third Armies would march into the capital. On the advice of the cabinet, the sultan ordered parliament to be convened by Ferman that same day . A week later, the palace declared the end of espionage and censorship. The grand manuscript of August 1, 1908, once again confirmed the validity of the constitution and supplemented it in part. Initially, only the revolters were amnestied . This was later followed by an amnesty for political prisoners who had served two-thirds of their term. Due to protests, however, a general amnesty took place, which in turn led to a demonstration in the form of a march of around 2,000 people to the Sublime Porte . About two weeks after his appointment, Said Pasha resigned as Grand Vizier on August 5, 1908, partly because of his critical and contrary opinion on the general amnesty, but mainly because of differences of opinion with the Committee for Unity and Progress. His successor was Kâmil Pascha, known as an Anglophil and liberal .

The Senate and the newly elected House of Representatives met on December 17, 1908. Ahmed Rızâ , who had returned from exile, became President of the House of Representatives . A total of 147 Turks, 60 Arabs, 27 Albanians, 26 Greeks, 14 Armenians, 4 Jews and 10 Slavs were represented. MPs also included members of the Committee on Unity and Progress such as Talât Bey . The leading figures Enver and Cemal Bey , on the other hand, did not become MPs, but retained a great deal of influence in politics. In mid-February 1909, Grand Vizier Kâmil Pascha was replaced by Hüseyin Hilmi Pascha by means of a vote of no confidence with 198 votes to 8 in the House of Representatives , after he had appointed two new ministers without consulting the Committee for Unity and Progress.

Counter coup: "The event of March 31st"

Soon after the revolution, critical voices rose against the Young Turks as a result of various territorial losses. Taking advantage of the opportunity that had Cretan government unilaterally proclaimed connection to Greece, Austria-Hungary , Bosnia and Herzegovina annexed (see. Bosnian crisis ) and Ferdinand I , the Principality of Bulgaria to the independent Kingdom of Bulgaria declares (cf.. Bulgaria's independence ) .

In religious-traditional circles, too, and especially in Istanbul, displeasure about the “freedom” declared by the Young Turks prevailed and grew. Dervish Vahdetî , founder of İttihad-ı Muhammedî Fırkası (“Mohammedan Unity Party”) and editor of the newspaper Volḳan (“Vulkan”), propagated that the existence of Islam was in danger. The fact that women still appeared in public wearing Çarşaf but without a face veil met with incomprehension and led to attacks. On October 14, 1908, an angry crowd lynched a Greek gardener when it became known that he and a Muslim woman were about to get married. Furthermore, theology students who had previously been exempt from military service now stood up against the Young Turks because of a draft law regarding their conscription. In particular, the Young Turks, who mainly included graduates from military academies called Mektebli , were confronted with regimental officers who had emerged from the soldier's class without such training (Alaylı) . The Alaylı increasingly felt they were being ousted by the “western” trained Mektebli , who were accused of disbelief because they neglected prayer due to their time-consuming training .

The murder of the anti -government journalist Hasan Fehmi Bey from the newspaper Serbestī (“Independence”) on April 7, 1909 finally brought the barrel to overflowing in the already heated mood. On the night of April 13, 1909, Greg. / 31. March 1325 rūmī , loyal to the sult, Alaylı took over the leadership of a counter-coup, which was at least benevolently tolerated by Abdülhamid II - in the hope of returning to the absolutist status quo ante. About 5,000 to 6,000 soldiers and hundreds of students and hodjas gathered on Sultan Ahmed Square and chanted şeriat isteriz, padişahımız çok yaşa (“we demand Sharia , long live our Padishah ”). Young Turkish politicians were murdered all over the city. Justice Minister Nâzım Pascha , who was mistaken for the President of the House of Representatives Ahmed Rızâ, and MP Arslan Bey - due to his resemblance to the Young Turkish journalist Hüseyin Cahid Bey - fell victim to the mob. Navy Minister Rıza Pasha got away with serious injuries. Grand Vizier Hüseyin Hilmi Pascha resigned together with the entire cabinet. Ahmed Tevfik Pasha took over the office and formed a new government on April 14, which, however, received no recognition from the committee.

In Saloniki, the stronghold of the Young Turks, the news from Istanbul was received with horror. On April 15, the 40,000-50,000-strong intervention army (حرکت اوردوسو / Ḥareket Ordusu ) - as a non-partisan “guardian of [constitutional] freedom” - under the leadership of Hüseyin Hüsnü Pasha on the way to the capital. On April 22nd, Mahmud Şevket Pasha took over the supreme command of the army , which had meanwhile arrived in the Istanbul suburb of Yeşilköy , which finally marched into the city on the night of April 23rd to 24th, 1909 and bloodily suppressed the uprising: About 100 soldiers and died 230 insurgents. A few days later the parliament decided in a secret session with 136 to 59 votes and in accordance with a fatwa obtained beforehand by Sheikhul Islam Mehmed Ziyaeddin Efendi (خلع / ḫalʿ ) Abdülhamids II. On April 27, 1909, the politically unambitious puppet ruler Mehmed V took the place of the exile in Saloniki . On May 5, Hüseyin Hilmi Pasha, who had resigned under pressure from the insurgents, was again Grand Vizier. Members of the new cabinet now also included leading members of the committee, such as Finance Minister Mehmed Cavid Bey (from June) and Interior Minister Talât Bey (from August).

After being under siege for nine years (ادارۀ عرفيه / İdāre-ʾi ʿÖrfīye ) within the meaning of Art. 113 in Istanbul, the leaders and others significantly involved in the "incident", including Dervish Vahdetî, were judged by military tribunals (دیوان حرب عرفی / Dīvān-ı Ḥarb-i ʿÖrfī ) sentenced to death (75 people in total) and put on public display after their execution. The government opposed a trial against the deposed Abdülhamid.

The Abide-i Hürriyet in Istanbul, inaugurated in 1911 and which served as the central national memorial until the Republican era , commemorates the victims of the event of March 31 .

Constitutional amendments

In August 1909 the parliament passed a far-reaching constitutional amendment, so that in this context the "Constitution of 1909" is also used. The amendment of 21 articles, the deletion of article 119 and the addition of three articles mainly restricted the rulership of the sultan and expanded the powers of the people's representation. The Sultan's right to dissolve Parliament was subject to considerable restrictions, so that this could only take place under the conditions of Art. 35 and only with the consent of the Senate; the mandatory new elections had to be completed within three (previously six, Art. 73) months, Art. 7 i. V. m. Art. 35. According to Art. 7 i. V. m. Art. 43 only possible at the appointed time (beginning of May rūmī ). Furthermore, the parliament, which was no longer compulsorily convened, but only opened by decree (cf. Art. 7, 43, 44), could now propose the drafting of new and the amendment of existing laws under Art. 53. By deleting Art. 113 Clause 3, the Sultan lost his right to pronounce bans. Preventive censorship was banned and the citizens and workers were granted limited political association and assembly rights and the right to strike .

Further changes followed in the years 1914 to 1918. The Sultan suffered additional losses in power; so he could only dissolve the House of Representatives on condition that it was re-elected within four months. The government was appointed with the approval of the House of Representatives, with the ministers being responsible to it. In addition, Parliament was now entitled to adopt bills rejected by the Sultan with a two-thirds majority.

Repeal

With the defeat in World War I and the signing of the Mudros Armistice Agreement on October 30, 1918, the Ottoman Empire suffered considerable territorial losses. The remaining areas - Asia Minor and Thrace - were largely occupied by the victorious powers. A resistance movement led by Mustafa Kemal Pascha (Ataturk) arose against this occupation . In the course of the so-called War of Liberation , the resistanceists founded the Grand National Assembly in Ankara on April 23, 1920 . On January 20, 1921, this counter-government ratified Law No. 85 , the "de facto Constitution of the Resistance Movement". This constitutional law, which declared the nation to be sovereign (Art. 1 Clause 1), did not repeal the Ottoman Basic Law, but supplemented it and partially repealed it ( lex posterior derogat legi priori ) . The Sultanate remained formally untouched, but Article 2 of the Grand National Assembly laid claim to the exclusive exercise of legislative and executive powers (unity of powers). Unconsidered remained the judiciary , with the established during the liberation war of independence dishes (Independence Tribunals) was of great importance. The question of the form of government of the first constitutionally named "Turkey" ([!]تورکیا دولتی) initially remained open.

Along with the institutional separation of the Sultanate and the Caliphate , the National Assembly, in its resolution of November 1, 1922, designated the Sultanate as belonging to history forever since March 16, 1920. Since Mehmed VI. refused to voluntarily abdicate, he was threatened with a trial for treason, so that he was forced to flee into exile. After the republic (Art. 1 Clause 3;جمهوریت / cumhūrīyet ) as the form of government and the office of President of the Republic (Art. 10, 11;رئيس جمهور / reʾīs-i cumhūr ), the caliphate was finally abolished on March 3, 1924.

Ultimately, the Ḳānūn-ı Esāsī and the constitutional law of 1921 were repealed on May 24, 1924 with Article 104 of the April 20, 1924 constitution. Article 1 of this constitution determined the republic as a form of government and was withdrawn from constitutional amendment by Article 102, Paragraph 4 (see also eternity clause ) . The popular sovereignty enshrined in Art. 1 Clause 1 of the Constitutional Law of 1921 has now been recorded in Art. The legislative power was exercised by the Grand National Assembly (Art. 6), the executive power by the President and Council of Enforcement Commissioners ( İcra Vekilleri Heyeti ; later: Council of Ministers, Bakanlar Kurulu ) (Art. 7). Art. 8 determined the independence of the Turkish judiciary .

content

General

The constitution was preceded by a Ḫaṭṭ-ı Hümāyūn - originally addressed to Midhat Pasha - as a preamble . The Basic Law was divided into twelve titles and initially comprised a total of 119 articles ( sing. ماده / madde ). By deleting one and adding three articles in August 1909, the number increased to a total of 121.

جناب حق ملك و ملتمزك سعادت حالنه چالیشانلرك مساعیسنی مظهر توفیق بیوره / Cenāb-ı ḥaḳḳ mülk ve milletimiziñ seʿādet ḥāline çalışanlarıñ mesāʿīsini maẓhar-ı tevfīḳ buyura. / 'God Almighty may all who work for the benefit of Our kingdom and people be part of success.'

State organization

In the first section of the constitution, the indivisibility of the Ottoman state (دولت عثمانيه / Devlet-i ʿOs̲mānīye ) with the capital Istanbul /استانبولset. The rule of the sultan was based on the monarchical principle . The offices of sultan and caliph were given to the Osmans family (سلالهٔ آل عثمان / sülāle-ʾi āl-i ʿOs̲mān ) and, as has been customary since the reign of Ahmed I , now under statutory law to the oldest male beneficiary (اکبر اولاد / ekber evlād ) inherited ( seniority principle ). According to Art. 4, the ruler was considered the protector of Islam (دین اسلامك حامیسی / dīn-i İslāmıñ ḥāmīsi ) and was in his person as holy and not responsible to anyone (مقدس و غیر مسؤل / muḳaddes ve ġayr-i mesʾūl ) recognized, Art. 5. Article 6 protected the freedom rights of the Sultan's family as well as their movable and immovable private property and their lifelong civil lists .

Finally, in Article 7, the sovereign was granted extensive, not exhaustively listed sovereign rights. The wording in the 1876 version was as follows:

"وکلانك عزل و نصبی و رتبه و مناصب توجیهی و نشان اعطاسی و ایالات ممتازه نك شرائط امتیازیه لرینه توفيقا اجرای توجیهاتی و مسکوکات ضربی و خطبه لرده نامنك ذکری و دول اجنبیه ایله معاهدات عقدی و حرب و صلح اعلانی و قوه بریه و بحریه نك قومانده سی و حرکات عسکریه و احکام شرعیه و قانونیه نك اجراسی و دوائر اداره نك معاملاتنه متعلق نظامنامه لرك تنظیمی و مجازات قانونیه نك تخفیفی ویا عفوی و مجلس عمومینك عقد و تعطیلی و لدی الاقتضا هیئت مبعوثانك اعضاسی یکیدن انتخاب اولنمق شرطیله فسخی حقوق مقدسه پادشاهی جمله سندندر"

"Vükelānıñ'azl ve naṣbı ve rütbe ve menāṣıb tevcīhi ve Nisan i'ṭāsı ve eyālāt-ı mümtāzeniñ şerā'iṭ-i imtiyāzīyelerine tevfīḳan ICRA Yi tevcīhātı ve meskūkāt darbi ve ḫuṭbelerde nāmınıñ Zikri ve Düvel-i ecnebīye ile mu'āhedāt'aḳdi ve Harb ve sulh i'lānı ve ḳuvve- 'i berrīye ve baḥrīyeniñ ḳumandası ve harekat-ı'askerīye ve Ahkam-ı şer'īye ve ḳānūnīyeniñ icrāsı ve devā'ir-i idāreniñ mu'āmelātına müte'alliḳ niẓāmnāmeleriñ tanẓīmi ve mücāzāt-ı ḳānūnīyeniñ taḫfīfi vEYA'afvı ve meclis-i'umūmīniñ'aḳd ve ta'ṭīli ve lede'l-iḳtiżā hey'et-i mebʿūs̲ānıñ aʿżāsı yeñiden intiḫāb olunmaḳ şarṭiyle fesḫi ḥuḳūḳ-ı muḳaddese-ʾi pādişahī cümlesindendir. "

“The holy rights of the [ Padishah ] include: the appointment and dismissal of ministers; the appointment to offices and ranks and the bestowal of awards; the appointment of the highest officials in the privileged territories of the Reich in accordance with the special rights granted to them; the coinage; the mention of his name in Friday public prayers ; the conclusion of treaties with foreign states; the declaration of war and peace; the supreme command of the armed power on [land and sea]; the execution of military movements and the regulations [of the Sharia ] and [of] secular law; the issuing of service instructions for the administrative authorities; the mitigation or waiver of statutory penalties; the convening and closing of [Parliament]; if necessary, the dissolution of the House of Representatives on condition that its members are re-elected. "

Fundamental rights

In the second section (تبعهٔ دولت عثمانیه نك حقوق عمومیه سی / Tebaʿ-ʾi Devlet-i ʿOs̲mānīyeniñ Ḥuḳūḳ-ı ʿUmūmīyesi / 'general rights of the Ottomans'), which corresponded to Title II of the Belgian and Prussian constitution and which was modeled on the declaration of human and civil rights , were the basic rights in the Articles 8 to 26 and, from August 1909, also in Articles 119 and 120.

Art. 8 initially defined the term Osmanlı /عثمانلی / 'Ottoman'. Ottomans were therefore "all subjects of the Ottoman Empire, whatever religion or sect they belong to". This “citizenship” could also be acquired or lost. Unless the freedom rights of third parties were violated, personal freedom (حریت شخصیه / ḥürrīyet-i şaḫṣīye ) and the right to self-determination is expressly protected from attacks and arbitrary state decisions , Art. 9, 10. Article 11 defined Islam as the state religion, but granted all members of recognized religions free exercise , provided that this was not contrary to public order and repudiated morality. The freedom of the press , as long as it was in accordance with the law, and from 1909 the prohibition of prior censorship were enshrined in Art. Freedom of association restricted to trade, commerce and agriculture (شركت تشكيلنه مأذونيت / şirket teşkīline meʾẕūnīyet ) became a limited political association and assembly right by Art. 13 and from 1909 (حق اجتماع / ḥaḳḳ-ı ictimāʿ ) guaranteed by Art. 120. According to Art. 14, every Ottoman subject had the right to address the competent authorities and Parliament (individually or in association with others) (عرض حال ویرمیه صلاحیت / ʿArż-ı ḥāl vėrmeye ṣalāḥīyet / ' Right to petition ') and to receive or give free instruction in accordance with Art. 15. All schools were placed under state control (Art. 16). Furthermore, all Ottomans were given equal status before the law and they were granted or imposed the same rights and duties towards the empire (Art. 17). Access to the civil service was open to all subjects (as had been the case since the Ḫaṭṭ-ı Hümāyūn of 1856) (Article 19), but was dependent on a command of Turkish , the official language (Article 18). Taxes were "imposed on all Ottoman subjects in proportion to their property" (Art. 20), property was placed under protection and expropriation only in the public interest (منافع عموميه / menāfiʿ-i ʿumūmīye ) and, in accordance with the law, against compensation (دکر بهاسی / değer bahāsı ) (Art. 21). The inviolability of the home was anchored in Art. 22, the right to a legal judge in Art. Asset Confiscations (مصادره / müṣādere ) and Corvée (انغاریه / anġarya ) were banned with Article 24, torture and other ill-treatment with Article 26. According to Art. 25, among other things, taxes could only be levied on the basis of a law (see: Lawfulness of Taxation ) .

Council of Ministers

Members of the Council of Ministers (وكلای دولت / Vükelā-yı Devlet / 'Minister of State'; Art. 27–38, Section 3) were the Grand Vizier, Sheikhul Islam, the President of the Council of State and the Foreign, Building, Finance, Trade and Agriculture, Interior, Justice, War, Culture and Navy Ministers . Other members were the Minister of Religious Foundations and the Minister of Post, Telegraphs and Telephones.

Grand Vizier and Sheikhul Islam were appointed directly by the Sultan, the other members by imperial decree (Art. 27). The council entered under the chairmanship of the Grand Vizier, who assumed the duties of the head of government (رئيس وكلا / reʾīs-i vükelā ) took over, together (Art. 28). The ministers were initially only responsible to the ruler, after the constitutional amendment of 1909, "jointly for the general policy of the government and individually for the business of their office towards the House of Representatives" (Art. 30) and could be deposed by him by a declaration of no confidence, Art. 38. The appointment was also changed in 1909. The offices of Grand Vizier and Sheikhul Islam continued to be delegated by the Sultan, but the other members were appointed by the Grand Vizier.

Furthermore, according to Article 35, in the event of fundamental differences of opinion with the Chamber of Deputies, the ministers had to either resign or accept the decision of the deputies. In May 1914, Article 35 was changed again. According to this change, the Sultan decided, if the situation described above, whether new ministers were installed or the House of Representatives dissolved, but then re-elected within four months. On March 9, 1916, Art. 35 was completely omitted.

The members of the Council were entitled to attend parliamentary sessions and to speak at any time, Art. 37.

Officer

Officer (مأمورين / Meʾmūrīn ; Art. 39–41, Section 4) could neither be dismissed nor dismissed "as long as their conduct does not constitute a legal reason for their removal and they do not resign themselves or there is no compelling reason for the government to remove them" (Art. 39 ). According to Art. 41, they were “obliged to respect and awe” towards their superiors and had to follow their instructions (duty of obedience ), provided they did not violate the law. In the event of compliance in illegal cases, the officer was responsible for the same.

houses of Parliament

Parliament (مجلس عمومی / Meclis-i ʿUmūmī ; Art. 42–59, section 5) consisted of two chambers, the Senate and the House of Representatives, according to Art. 42, 43, which opened annually by imperial decree (since 1909 without convocation) from the beginning of November to the beginning of March rūmī (from August 1909 “ Beginning of May ”; from February 1915“ four months ”, thus again at the beginning of March) met. The Sultan was able to convene or open and close parliament before this point in time and thus extend the duration of the session (تمديد / temdīd ) or shorten (تنقيص / tenḳīṣ ), cf. Art. 44. From August 1909 the duration of the session could only be extended, but no longer shortened, either by the imperial decision or by a written request of the majority of the deputies, only through early opening or late closing. On the day of the opening, the Sultan or at least the Grand Vizier as his representative, as well as the ministers and members of both chambers, had to be present (Art. 45). The latter were sworn on that day and swore “to serve the fatherland faithfully, to fulfill all the duties imposed on them by the Constitution and their mandate, and to abstain from all actions that run counter to these duties” (Art. 46).

Art. 47 guaranteed the free mandate , that is, the acquittal of being bound by "promises or instructions", as well as the indemnity of the parliamentarians. Furthermore, MPs enjoyed an immunity limited to the duration of the session , which could only be lifted by a majority of the votes of Parliament, Art. 79. The members of Parliament could not belong to both chambers at the same time and hold no other office (Art. 50).

The right of initiative lay with the ministers (Art. 53), whereby the parliament (until August 1909) only had a limited right of initiative dependent on the at least tacit consent of the sultan. At the request of the Senate or the House of Representatives, but only with the ruler's decree, the State Council drafted bills (Art. 54), which were first discussed by the House of Representatives and then passed on to the Senate (Art. 55). These only became legally binding by imperial decree (Art. 54). The parliamentary sessions had to be in Turkish (Art. 57).

The first parliament was on 19./20. Opened March 1877 with a speech given by the Sultan in the ballroom of the Dolmabahçe Palace , given by Said Pasha . Of the total of 155 parliamentarians, 119 came from the House of Representatives. The number of non-Muslims was 58.

senate

The total number of members of the Senate (هيئت اعيان / Heyʾet-i Aʿyān ; Art. 60–64, Section 6) was limited to a maximum of one third of the number of members of the House of Representatives; The President and the members of the Senate were appointed by the Sultan for life (Art. 60). They had to be at least 40 years old (Art. 61) and could be “transferred to another office by the state at their own request” (cf. Art. 62). The monthly salary of the senators was 10,000 Kurush (Art. 63). The task of the Senate was to review bills and budgets submitted by the House of Representatives for violations of “the faith, the sovereign rights of the Sultan, freedom, the constitution, the territorial unity of the state, the internal security in the country, protection and defense measures taken by the Fatherland or against public security ”and, if necessary, sent back to the House of Representatives or forwarded to the Grand Vizier (Art. 64). In addition, there was the right of interpretation (تفسير / tefsīr ) regarding the constitution according to Art. 117 to the Senate.

The first president of the 32-member Senate was Server Pasha.

House of Representatives

The total number of members of the House of Representatives (هيئت مبعوثان / Heyʾet-i Mebʿūs̲ān ; Art. 65–80, Section 7) was limited in such a way that there was one MP for every 50,000 male residents (Art. 65).

According to Art. 66, the elections had to take place according to special law. A provisional, seven-article electoral law was already approved by the Sultan on October 15, 1876, entered into force on October 28 and November 6, 1876 and should cease to be in force after a single application in accordance with Art. However, due to the lack of a new law, the provisional electoral law was applied again. A special law called Beyānnāme , which was promulgated on January 1, 1877 , applied to Istanbul and its surroundings, including Izmir . The electoral law and beyānnāme contained provisions that were contrary to the constitution. For example, Article 69 of the constitution stipulates a term of office (مدت مأموریت / tired-i meʾmūrīyet ) of four years; however, the electoral law provided for annual parliamentary elections.

The Election Act (انتخاب مبعوثان قانونی / İntiḫāb-ı Mebʿūs̲ān Ḳānūnı ) from 1877 largely adopted the provisions of the provisional electoral law, but did not come into force until the second constitutional period due to a lack of imperial approbation. According to Art. 66 of the Constitution in conjunction with Art. 8, 21 of the Law on Election of Representatives, elections took place equally and indirectly, free and secret , but not generally . Women, for example, had no right to vote. Up to 500 electors (Müntehib-i evvel) elected with a relative majority an elector (منتخب ثانی / Münteḫib-i s̲ānī ) (Articles 21, 43, 45, 46 of the Electoral Law for Representatives). The voters were not allowed to be or claim to be members of a foreign nation and had to be over 25 years of age. In addition, at the time of the election they were not allowed to be employed by another person or under a guardian, have forfeited their political rights or be joint debtors. The electors also had to be subjects of the empire and were not allowed to be in the service of another nation. Members of parliament were also required to be at least 30 years of age (25 in the electoral law) and master the Turkish language. Furthermore, they were not allowed to be known for "an immoral lifestyle" (cf. Art. 68). Their re-election was possible (Art. 69).

The president and two vice-presidents were appointed by the sultan from three proposed candidates each, Art. 77. After the constitutional amendment of 1909, the election of the presidium took place immediately and the sultan was only informed of the result. The MPs received an annual allowance of 20,000, from 1909 30,000 and after 1916 50,000 kurūsch from the state treasury as well as a monthly travel allowance of 5,000 (from 1916 4,000) kurūsch, Art. 76.

Abdülhamid II appointed the loyal Ahmed Vefik Pasha as the first President of the house, contrary to the procedure prescribed in Art. 77 . In the second legislative period , Art. 1 of the Rules of Procedure (نظامنامهٔ داخلی / Niẓāmnāme-ʾi Dāḫilī ) corresponding to the oldest member, Gümüşgerdan Mihalaki Bey, President. Later Hasan Fehmi Efendi was able to prevail against Rıfat Efendi and Sheikh Bahaeddin Efendi, who became first vice-president. Hüdaverdizâde Hovhannes Allahverdian became the second vice president.

jurisdiction

In the section محاكم / Meḥākim / 'Courts' (Articles 81–91), the independence of the courts (cf. Article 86) and the security of the judges were guaranteed. Art. 81 initially regulated the appointment, transfer, retirement and dismissal of judges, according to which they were appointed by decree and not withdrawable, but could voluntarily resign from office. More was to be found in a special law. In principle, court hearings had to take place with the participation of the public ; Judgments could be published. Exclusion of the public was permissible in cases regulated by law (Art. 82). Everyone was entitled to make use of the necessary legal means in court (Art. 83).

Art. 87 stipulated that "Trials that relate to Scheriat law [...] before the Scheriat courts, those that are decided according to civil law before the civil courts".

High Court

Pursuant to Art. 92, the High Court (دیوان عالی / Dīvān-ı ʿĀlī ; Art. 92–95, Section 9) is responsible for proceedings against ministers, members of the Court of Cassation and against persons “who act against the person or the rights of the Sultan or attempt to endanger the security of the state”. The two-chamber court consisted of ten members each from the Senate, the Council of State (شورای دولت / Şūrā-yı Devlet ) and from the Court of Cassation and Appeal (محكمهٔ تمييز و استئناف / Maḥkeme-ʾi Temyīz ve İstiʾnāf ), a total of 30 members (Art. 92). The Prosecution Chamber (دائرهٔ اتهامیه / Dāʾire-ʾi İthāmīye ) consisted of nine (Art. 93), the Judgment Chamber (دیوان حكم / Dīvān-ı Ḥüküm ) of 21 judges (Art. 95). According to Art. 94, the Prosecution Chamber had to decide by a two-thirds majority whether an action was brought at all. When a lawsuit was brought, the judgment chamber also decided with a two-thirds majority in accordance with the applicable law, whereby the judgments were neither appealable nor cashable (Art. 95).

Finances

Taxes could only be levied on the basis of laws (Art. 96). Draft budgets were presented to the House of Representatives immediately after the opening of Parliament (Art. 99) and, after examination in Parliament, either referred back to the House of Representatives or approved and forwarded to the Grand Vizier (Art. 98 in conjunction with Art. 64). The budget was basically valid for one year, but could be extended by one year by imperial decree and resolution of the ministers if the House of Representatives was dissolved (Art. 102). In addition, an audit office (دیوان محاسبات / Dīvān-ı Muḥāsebāt ) and was responsible for checking the officials entrusted with finances (Art. 105). The Court of Auditors consisted of twelve members who could be appointed by the Sultan and dismissed only by the Chamber of Deputies (Art. 106).

Various provisions

In the twelfth and last section (Articles 113–119 or 121) the "various provisions" (مواد شتی / Mevādd-ı Şettā ). According to Art. 113 Sentences 1, 2, the government could, if necessary, a locally and temporally limited state of siege (ادارۀ عرفيه / İdāre-ʾi ʿÖrfīye ) and the Sultan was entitled to the right of banishment from Art. 113 sentence 3 until August 1909. Primary instruction (birinci mertebe) was compulsory for all Ottomans (Art. 114). Art. 115 protected the constitution from suspension and repeal. A constitutional amendment could only be made on the proposal of the Council of Ministers, the Senate or the House of Representatives through an acceptance with a two-thirds majority in the Senate and confirmation of the acceptance with a two-thirds majority in the House of Representatives and with the consent of the Sultan (Art. 116). The Court of Cassation and Appeal was responsible for judicial matters, the Council of State for administrative matters and the Senate for constitutional matters (Art. 117).

From August 1909, Art. 119 protected the secrecy of correspondence , Art. 120 on the one hand guaranteed freedom of association and on the other hand prohibited associations “that violate morality and common decency or serve the purpose of violating the territorial existence of the Ottoman Empire, the form of To change the constitution and government, to act against the provisions of the constitution and to politically separate the various Ottoman parts of the people ”. The establishment of secret societies was also prohibited. According to Art. 121, meetings in the Senate had to be public, but could be held non-public at the request of the ministers or five senators with a majority of votes.

Meaning and criticism

As a result of this constitution, for the first time in the Ottoman Empire, an attempt was made to deny the absolute legitimacy of the religious legitimation of the power of rule and state with democratic elements. However, this failed in view of the fact that the constitution was drawn up by a committee convened directly by the Sultan and the drafts were reviewed by monarchists such as Mütercim Mehmed Rüşdi Pascha or Ahmed Cevdet Pascha . The document ultimately protected the ruler's rights and privileges vis-à-vis the people and parliament. The sultan remained theocratically legitimized ruler, to whom the state organization was tailored. Thus the Sultan ruled in an absolutist sense despite a de jure valid constitution . This was particularly evident in the closing of parliament just eleven months after the constitution came into force. The constitution promulgated by Ferman was again effectively suspended by a Ferman. The basic rights guaranteed in the constitution - albeit also in previous edicts - were not insignificant in Ottoman legal history, but were severely limited by the ruler's discretion because of the right of banishment under Art. 113 sentence 3.

The extent to which the factual ineffectiveness of the constitution, which lasted for more than thirty years, had an impact on freedom of the press became noticeable after the ban on press censorship in 1908. The number of periodicals published rose suddenly after the constitution was reinstated. In the years 1908 and 1909 330 works were counted (see also the article on Mehmed Memduh ).

literature

- Gotthard Jäschke : The development of the Ottoman constitutional state from the beginning to the present. In: The world of Islam . Volume 5, Issue 1/2, Brill, August 1917, pp. 5-56.

- Gotthard Jäschke: The legal significance of the amendments made to the Turkish constitutional law between 1909 and 1916. In: The world of Islam. Volume 5, Issue 3, November 1917, pp. 97-152.

- Christian Rumpf : The Turkish constitutional system. Introduction with complete constitutional text. Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 1996, ISBN 3-447-03831-4 , pp. 37-57.

- Bülent Tanör : Osmanlı-Türk Anayasal Gelişmeleri. 18th edition. Yapı Kredi Yayınları, Istanbul 2009, ISBN 978-975-363-688-1 , pp. 41–220.

Festschrift:

- Armağan. Kanun-u Esasî'nin 100. Yılı. Ankara Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakanschesi Yayınları, Ankara 1978.

Legal texts:

- Suna Kili, A. Şeref Gözübüyük: Türk Anayasa Metinleri. Sened-i İttifak'tan Günümüze. 3. Edition. Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, Istanbul 2006, ISBN 975-458-210-6 , pp. 33–51 (Turkish in Latin script , uncommented).

- Grégoire Aristarchi: Législation ottomane ou recueil des lois, règlements, ordonnances, traités, capitulations et autres documents officiels de l'Empire ottoman. Volume V, Constantinople 1878, pp. 1-25 (official French translation).

- Abdolonyme Ubicini : La constitution ottomane du 7 zilhidjé 1293 (23 December 1876) . Expliquée et Annotée by A. Ubicini. A. Cotillon et Co., Paris 1877, ia800308.us.archive.org (PDF)

-

Friedrich von Kraelitz-Greifenhorst : The constitutional laws of the Ottoman Empire. Translated from the Ottoman-Turkish and compiled. Verlag von Rudolf Haupt, Leipzig 1909, pp. 28–53.

- Revised edition: Friedrich von Kraelitz-Greifenhorst: The constitutional laws of

- Excerpt in: Andreas Meier (Ed.): The political mission of Islam. Programs and Criticism between Fundamentalism and Reforms. Original voices from the Islamic world. Peter Hammer Verlag, Wuppertal 1994, ISBN 3-87294-616-1 , pp. 71-78.

Web links

- Kanun-ı Esasi on the website of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey

Legal texts:

- Original version (PDF; 828 kB)

- Final version (PDF; 649 kB)

- Constitutional text in Latin script (without preamble)

- German translation of the constitutional text (translation by Kraelitz-Greifenhorst)

- French translation (the basis of translation into non-Muslim languages) published in:

- Documents diplomatiques: 1875–1876–1877 . Ministry of Foreign Affairs (France) , Imprimerie National, Paris 1877, pp. 272–289, pp. 281–298

- Documents historiques . In: Revue générale treizième année , volume 25, Chapter 10, Imprimerie E. Guyott, Brussels February 1877, pp. 319–330, pp. 319–343

- G. Pedone (Ed.): Annuaire de l'Institut de droit international . Paris 1878, pp. 296-316 catalogue.bnf.fr Read online . Text available accessed on January 17, 2011

- Greek Non-Muslim languages (PDF) at the Veria Digital Library - From Sismanoglio Megaro of the Consulate Gen. of Greece in Istanbul; Bulgarian (PDF)

Representations:

- Vedat Laçiner: The first Turkish constitution from 1876 Kanun-i Esasi . turkishweekly.net.

References and comments

- ↑ قانون اساسى یه دائر شرفصدور ایدن خط ھمایون عدالت مشحون شاھانه نك صورت منیفه سیدر / Ḳānūn-ı Esāsīye dāʾir şeref-ṣudūr eden ḫaṭṭ-ı hümāyūn-ı ʿadālet meşḥūn-ı şāhānenin ṣūret-i münīfesidir. Maṭbaʿa-ʾi Aḥmed Kāmil, Istanbul 1293.

- ^ Johann Strauss: A Constitution for a Multilingual Empire: Translations of the Kanun-ı Esasi and Other Official Texts into Minority Languages . In: Christoph Herzog, Malek Sharif (Ed.): The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy . Orient-Institut Istanbul , Wurzburg 2010, pp. 21–51. ( urn : nbn: de: gbv: 3: 5-91645 ) at Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg // CITED: p. 33 (PDF p. 35/338). "The official French version: […] This translation was made simultaneously by the Translation Office (Terceme odası) for transmission to the foreign ambassadors. 57 " // Also: p. 51 (PDF p. 53/338). "This is corroborated by the fact that most“ Western-style ”versions of the Kanun-i esasi tended to be translated from the French version rather than from Ottoman Turkish […] For all of these languages, French was the model and the source of the terminology, either by direct borrowing or through calques. "

- ^ Klaus Kreiser: History of Istanbul. From antiquity to the present. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-58781-8 , p. 85.

- ↑ Erhan Afyoncu, Ahmet Önal, Uğur Demir: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nda Askeri İsyanlar ve Darbeler. Yeditepe Yayınevi, Istanbul 2010, ISBN 978-605-4052-20-2 , p. 236 ff.

- ↑ M. Şükrü Hanioğlu: A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire. Princeton University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-691-13452-9 , p. 56.

- ↑ Virginia H. Aksan: Ottoman Wars 1700-1870. To Empire Besieged. Pearson Education Limited, London 2007, ISBN 978-0-582-30807-7 , p. 249.

- ↑ In the alliance treaty:«نفسانیت و شقاق حالاتی» / 'nefsānīyet ve şıḳāḳ ḥālāti' / 'states of spite and discord'.

- ↑ Bülent Tanör: Osmanlı-Türk Anayasal Gelişmeleri. 18th edition. Yapı Kredi Yayınları, Istanbul 2009, ISBN 978-975-363-688-9 , p. 43.

- ^ A b Virginia H. Aksan, Daniel Goffman: The early modern Ottomans. Remapping the Empire. Cambridge University Press, 2007, ISBN 978-0-521-81764-6 , pp. 124 f.

- ↑ a b Kemal Gözler: Türk Anayasa Hukukuna Giriş. 1st edition. Ekin Kitabevi, Bursa 2008, ISBN 978-9944-14-137-6 , p. 10 ff.

- ^ Sina Akşin: Sened-i İttifak ile Magna Carta'nın Karşılaştırılması. In: Ankara Üniversitesi Dil ve Tarih-Coğrafya Fakuchteesi Tarih Bölümü Tarih Araştırmaları Dergisi. Volume 16, No. 27, 1992, pp. 115-123, ankara.edu.tr (PDF; 490 kB).

- ↑ Christian Rumpf: Reception and constitutional order: Example Turkey. Stuttgart 2001, p. 4, tuerkei-recht.de (PDF; 211 kB).

- ↑ Kutluhan Bozkurt: Turkey's relations with the EU. Legal processes and legal influences. Vienna 2004, p. 47 f., Juridicum.at ( Memento of the original from September 19, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 1.2 MB).

- ↑ Josef Matuz: The Ottoman Empire. Baseline of its history. 6th edition. Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-89678-703-3 , p. 215 f.

- ↑ Gottfried Plagemann: From Allah's Law to Modernization by Law. Law and Legislation in the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey. Lit Verlag, Berlin / Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-8258-0114-4 , p. 84 with additional information

- ↑ Christian Rumpf: The Turkish constitutional system. Introduction with complete constitutional text. Harrassowitz Verlag, Wiesbaden 1996, ISBN 3-447-03831-4 , p. 37.

- ↑ See Klaus Kreiser: The Ottoman State 1300-1922. 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-486-58588-9 , p. 36.

- ↑ Kemal Gözler: Türk Anayasa Hukuku. Ekin Kitabevi Yayınları, Bursa 2000, p. 12: “ maddî anlamda anayasal niteligte olan bir belge ”.

- ↑ Josef Matuz: The Ottoman Empire. Baseline of its history. 6th edition. Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-89678-703-3 , p. 224.

- ↑ Klaus Kreiser: The Ottoman State 1300-1922. 2nd Edition. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, Munich 2008, ISBN 978-3-486-58588-9 , p. 39.

- ^ Sabri Şakir Ansay: The Turkish law. In: Bertold Spuler (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Orientalistik. First Dept. The Near and Middle East. Supplementary volume III. Oriental law. Brill, Leiden 1964, p. 442 f.

- ↑ Kemal Gözler: Türk Anayasa Hukukuna Giriş. 1st edition. Ekin Kitabevi, Bursa 2008, ISBN 978-9944-14-137-6 , p. 16.

- ↑ See Günter Seufert u. a .: Turkey: politics, history, culture. CH Beck, 2006, ISBN 3-406-54750-8 , p. 71 f.

- ↑ Klaus Kreiser, Christoph K. Neumann: Small history of Turkey. Federal Agency for Civic Education, Bonn 2006, ISBN 3-89331-654-X , p. 337 f.

- ↑ Bülent Tanör: Osmanlı-Türk Anayasal Gelişmeleri. 18th edition. Yapı Kredi Yayınları, Istanbul 2009, ISBN 978-975-363-688-9 , p. 131.

- ↑ مجنون / mecnūn / 'insane'; see Selda Kaya Kılıç: 1876 Kanun-i Esasi'nin Hazırlanması ve Meclis-i Mebusan'ın Toplanması. Ankara 1991, p. 80.

- ↑ a b c Yusuf Ziya Özer: Mukayeseli Hukuku Esasiye Dersleri. Recep Ulusoğlu Basımevi, Ankara 1939, p. 389 ff. ( Ankara.edu.tr ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. (PDF; 24.4 MB).

- ↑ Erhan Afyoncu, Ahmet Önal, Uğur Demir: Osmanlı İmparatorluğu'nda Askeri İsyanlar ve Darbeler. Yeditepe Yayınevi, Istanbul 2010, ISBN 978-605-4052-20-2 , p. 266.

- ↑ a b c Sina Akşin: Birinci Meşrutiyet Meclis-i Mebusanı (I). In: Ankara Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakanschesi Dergisi. Volume 25, No. 1, 1970, pp. 19-39 (19 f.), Ankara.edu.tr (PDF; 8.9 MB).

- ↑ Bernhard Stern. Young Turks and conspirators. The internal situation of Turkey under Abdul Hamid II. 2nd edition. Verlag von Grübel & Sommerlatte, Leipzig 1901, p. 161.

- ^ A b c Stanford Shaw, Ezel Kural Shaw: History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Vol. II: Reform, Revolution, and Republic. The Rise of Modern Turkey, 1808-1975. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge u. a. 2002, ISBN 0-521-29166-6 , p. 174 f.

- ↑ a b c Selda Kaya Kılıç: 1876 Anayasasının Bilinmeyen İki Tasarısı. In: Ankara Üniversitesi Osmanlı Tarihi Araştırma ve Uygulama Merkezi Dergisi. No. 4, 1993, pp. 557-633 (563 ff.), Ankara.edu.tr (PDF; 3.8 MB).

- ↑ Selda Kaya Kılıç: 1876 Kanun-i Esasi'nin Hazırlanması ve Meclis-i Mebusan'ın Toplanması. Ankara 1991, p. 109 ff. With further references

- ↑ a b Kemal Gözler: Türk Anayasa Hukuku. Ekin Kitabevi, Bursa 2000, p. 19 ff. (Online)

- ↑ Gotthard Jäschke: The development of the Ottoman constitutional state from the beginning to the present. In: The world of Islam. Volume 5, Issue 1/2, Brill, 1917, pp. 5-56 (12).

- ↑ a b Ahmet Mumcu: Türkiye'de İnsan Hakları ve Kamu Özgürlüklerin Tarihsel Gelişimi. In: Kıymet Selvi (ed.): İnsan Hakları ve Kamu Özgürlükleri. 2nd Edition. Anadolu Üniversitesi, Eskişehir 2005, ISBN 975-06-0312-5 , pp. 118 ff.

- ↑ a b Christian Rumpf: Reception and constitutional order. Example Turkey. Stuttgart 2001, p. 8, tuerkei-recht.de (PDF; 211 kB).

- ↑ a b M. Tayyib Gökbilgin: Midhat Paşa. In: İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Volume 8, Millî Eğitim Basımevi, Istanbul 1979, pp. 270-282 (277).

- ↑ Gotthard Jäschke: The development of the Ottoman constitutional state from the beginning to the present. In: The world of Islam. Volume 5, Issue 1/2, Brill, 1917, pp. 5-56 (13).

- ↑ فی ٧ ذی الحجه سنه ۱۲۹۳ / fī 7 Ẕī ʾl-ḥicce sene 1293 .

- ↑ For the official translation, see La Constitution ottomane du 7 zilhidjé 1293 (23 December 1876). Expliquée et annotée by A. Ubicini. Cotillon, Paris 1877.

- ^ Ralph Uhlig: The Inter-Parliamentary Union: 1889-1914. Franz Steiner Verlag, 1988, ISBN 3-515-05095-7 , p. 490 f.

- ↑ Roderic H. Davison: Midhat Pa sh a. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Volume 6, Brill, Leiden 1991, pp. 1031-1035 (1034).

- ↑ a b Hans-Jürgen Kornrumpf: Midhat Pascha, Ahmed Şefik. In: Mathias Bernath u. a. (Ed.): Biographical Lexicon on the History of Southeast Europe. Volume III. Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 1979, ISBN 3-486-48991-7 , p. 194.

- ↑ See Sina Akşin: Birinci Meşrutiyet Meclis-i Mebusanı (I). In: Ankara Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakanschesi Dergisi. Volume 25, No. 1, 1970, pp. 19-39 (39), ankara.edu.tr (PDF; 8.8 MB).

- ↑ Gottfried Plagemann: From Allah's Law to Modernization by Law. Law and Legislation in the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey. Lit Verlag, Berlin / Münster 2009, ISBN 978-3-8258-0114-4 , p. 95.

- ↑ Cf. Jean Deny: ʿAbd al-Ḥamīd. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Volume 1, Brill, Leiden 1986, pp. 63-65 (64).

- ↑ Cf. Roderic H. Davison: Midḥat Pa sh a. In: The Encyclopaedia of Islam. New Edition. Volume 6, Brill, Leiden 1991, pp. 1031-1035 (1031).

- ↑ M. Tayyib Gökbilgin: Midhat Paşa. In: İslâm Ansiklopedisi. Volume 8, Millî Eğitim Basımevi, Istanbul 1979, pp. 270-282 (281).

- ↑ a b Alan Palmer: Decline and fall of the Ottoman Empire. Heyne, Munich 1997, ISBN 3-453-11768-9 , p. 290 f.

- ↑ Mehmet Hacısalihoğlu: The Young Turks and the Macedonian Question (1890-1918). Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2003, ISBN 3-486-56745-4 , p. 165 ff.

- ↑ Kemal Gözler: Türk Anayasa Hukukuna Giriş. 1st edition. Ekin Kitabevi, Bursa 2008, ISBN 978-9944-14-137-6 , p. 23.

- ↑ a b Mehmet Hacısalihoğlu: The Young Turks and the Macedonian Question (1890-1918). Oldenbourg Wissenschaftsverlag, 2003, ISBN 3-486-56745-4 , pp. 188 ff.

- ↑ See İrāde of July 30, 1908.

- ↑ İlay İleri: Batı Gözüyle Meşrutiyet Kutlamaları ve Genel Af. Constitutional Monarchy Celebrations and the Amnesty to the Western Eye. In: Ankara Üniversitesi Osmanlı Tarihi Araştırma ve Uygulama Merkezi Dergisi. No. 17, 2005, pp. 295-310, ankara.edu.tr (PDF; 316 kB).

- ^ A b c Klaus Kreiser, Christoph K. Neumann: Small history of Turkey. Federal Agency for Civic Education , Bonn 2006, ISBN 3-89331-654-X , p. 357 ff.

- ↑ a b Handan Nezir Akmeşe: The Birth of Modern Turkey. The Ottoman Military and the March to World War I. IB Tauris, 2005, ISBN 1-85043-797-1 , pp. 87 ff.

- ↑ Gotthard Jäschke: The development of the Ottoman constitutional state from the beginning to the present. In: The world of Islam. Volume 5, Issue 1/2, Brill, 1917, pp. 5-56 (23).

- ↑ Josef Matuz: The Ottoman Empire. Baseline of its history. 6th edition. Primus Verlag, Darmstadt 2010, ISBN 978-3-89678-703-3 , pp. 251 f.

- ^ Klaus Kreiser: History of Istanbul. From antiquity to the present. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-58781-8 , p. 92 f.

- ↑ Gotthard Jäschke: The development of the Ottoman constitutional state from the beginning to the present. In: The world of Islam. Volume 5, Issue 1/2, Brill, 1917, pp. 5-56 (25).

- ↑ Bülent Tanör: Osmanlı-Türk Anayasal Gelişmeleri. 18th edition. Yapı Kredi Yayınları, Istanbul 2009, ISBN 978-975-363-688-9 , pp. 187 ff.

- ↑ Necdet Aysal: Örgütlenmeden Eyleme Geçiş. 31 Mart Olayı. In: Ankara Üniversitesi Türk İnkılâp Tarihi Enstitüsü Ataturk Yolu Dergisi. Volume 10, No. 37, 2006, pp. 15–53 (18 ff.), Ankara.edu.tr (PDF; 1.6 MB).

- ^ Charles Kurzman: Democracy Denied, 1905-1915. Intellectuals and the Fate of Democracy. Harvard University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-674-03092-3 , pp. 205 f.

- ^ Sina Akşin: The Place of the Young Turk Revolution in Turkish History. In: Ankara Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakanschesi Dergisi. Volume 50, No. 3, 1995, pp. 13-29 (16 ff.), Ankara.edu.tr (PDF; 1.09 MB).

- ^ Klaus Kreiser: History of Istanbul. From antiquity to the present. CH Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-58781-8 , p. 93.

- ↑ See Bülent Tanör: Osmanlı-Türk Anayasal Gelişmeleri. 18th edition. Yapı Kredi Yayınları, Istanbul 2009, ISBN 978-975-363-688-9 , p. 192.

- ↑ In detail, Gotthard Jäschke: The legal significance of the amendments to the Turkish constitutional law that were made between 1909 and 1916. In: The world of Islam. Volume 5, Issue 3, November 1917, pp. 97-152.

- ↑ Art. 3, 6, 7, 10, 12, 27–30, 35, 36, 38, 43, 44, 53, 54, 76, 77, 80, 113, 118.

- ↑ See thatجمعيتلر قانونى / Cemʿīyetler Ḳānūnı / 'Association Law' and thatاجتماعات عموميه قانونى / İctimāʿāt-i ʿUmūmīye Ḳānūnı / 'Law of Assembly' of 1909.

- ↑ Christian Rumpf: Reception and constitutional order. Example Turkey. Stuttgart 2001, p. 10, tuerkei-recht.de (PDF; 211 kB).

- ↑ Ahmet Mumcu: Türkiye'de İnsan Hakları ve Kamu Özgürlüklerin Tarihsel Gelişimi. In: Kıymet Selvi (ed.): İnsan Hakları ve Kamu Özgürlükleri. 2nd Edition. Anadolu Üniversitesi, Eskişehir 2005, ISBN 975-06-0312-5 , p. 122 ff.

- ↑ Burhan Gürdoğan: İkinci Meşrutiyet Devrinde Anayasa Değişiklikleri. In: Ankara Üniversitesi Hukuk Fakanschesi Dergisi. Volume 16, No. 1, 1959, pp. 91-105, ankara.edu.tr (PDF; 427 kB).

- ↑ Kutluhan Bozkurt: Turkey's relations with the EU. Legal processes and legal influences. Vienna 2004, p. 15 ( PDF; 1.16 MB ( Memento of the original from September 19, 2011 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove them Note. ).

- ↑ حاكمیت بلا قید و شرط ملتڭدر / Ḥākimīyet bilā ḳayd-ü şarṭ milletiñdir / 'State authority is unrestricted and unconditional to the nation.'

- ↑ Kemal Gözler: Türk Anayasa Hukukuna Giriş. 1st edition. Ekin Kitabevi, Bursa 2008, ISBN 978-9944-14-137-6 , p. 32.

- ↑ See Gotthard Jäschke: On the way to the Turkish Republic. A contribution to the constitutional history of Turkey. In: The world of Islam. Volume 5, Issue 3/4, Brill, 1958, pp. 206-218 (216).

- ↑ Cf. Gotthard Jäschke: Das Ottmanische Scheinkaliphat von 1922. In: Die Welt des Islams. Volume 1, Heft 3, Brill, 1951, pp. 195-228 (203) with further references

- ↑ Act No. 364 of October 29, 1923 on the amendment of certain provisions of the Constitutional Law for the sake of explanation ( German translation ).

- ↑ By Law No. 431 of March 3, 1924 concerning the abolition of the caliphate and expulsion of the Ottoman dynasty from the territory of the Republic of Turkey, RG No. 63 of March 6, 1924 ( German translation ).

- ^ Translation of Friedrich von Kraelitz-Greifenhorst: The constitutional laws of the Ottoman Empire. Verlag des Forschungsinstitut für Osten und Orient, Vienna 1919, p. 30.

- ↑ Gülnihal Bozkurt: Review of the Ottoman legal system. In: Ankara Üniversitesi Osmanlı Tarihi Araştırma ve Uygulama Merkezi Dergisi. No. 3, 1992, pp. 115-128 (120), ankara.edu.tr (PDF; 597 kB).

- ^ Translation from Gotthard Jäschke: The legal significance of the amendments made to the Turkish constitutional law between 1909 and 1916. In: The world of Islam. Volume 5, Issue 3, November 1917, pp. 97-152 (140).

- ↑ Gotthard Jäschke: The legal significance of the amendments made to the Turkish constitutional law between 1909 and 1916. In: The world of Islam. Volume 5, Issue 3, November 1917, pp. 97-152 (113).

- ↑ See thatجمعيتلر قانونى / Cemʿīyetler Ḳānūnı / 'Association Law' and thatاجتماعات عموميه قانونى / İctimāʿāt-i ʿUmūmīye Ḳānūnı / 'Law of Assembly' of 1909.

- ↑ See Gotthard Jäschke: The legal significance of the amendments made to the Turkish constitutional law in the years 1909–1916. In: The world of Islam. Volume 5, Issue 3, November 1917, pp. 97-152 (136).

- ↑ to be found in Başvekalet Arşivi, Yıldız Tasnifi. Kısım № 23, Evrak № 344, Zarf № 11, Carton № 71.

- ↑ Ahmet Oğuz: Birinci Meşrutiyet. Kanun-ı Esasi ve Meclis-i Mebusan. Graphic designer Yayınları, Ankara 2010, ISBN 978-975-6355-69-5 , p. 116.

- ↑ a b Bülent Tanör: Osmanlı-Türk Anayasal Gelişmeleri. 18th edition. Yapı Kredi Yayınları, Istanbul 2009, ISBN 978-975-363-688-9 , p. 152 ff.

- ↑ Gotthard Jäschke: The development of the Ottoman constitutional state from the beginning to the present. In: The world of Islam. Volume 5, Issue 1/2, Brill, 1917, pp. 5-56 (16).

- ↑ Sina Akşin: Birinci Meşrutiyet Meclis-i Mebusanı (I). In: Ankara Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakanschesi Dergisi. Volume 25, No. 1, 1970, pp. 19-39 (21), ankara.edu.tr (PDF; 8.87 MB).

- ↑ Gotthard Jäschke: The development of the Ottoman constitutional state from the beginning to the present. In: The world of Islam. Volume 5, Issue 1/2, Brill, 1917, pp. 5-56 (14).

- ↑ Selda Kaya Kılıç: 1876 Anayasasının Bilinmeyen İki Tasarısı. In: Ankara Üniversitesi Osmanlı Tarihi Araştırma ve Uygulama Merkezi Dergisi. No. 4, 1993, pp. 557-633 (569), ankara.edu.tr (PDF; 3.78 MB).

- ↑ Sina Akşin: Birinci Meşrutiyet Meclis-i Mebusanı (I). In: Ankara Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakanschesi Dergisi. Volume 25, No. 1, 1970, pp. 19-39 (23), ankara.edu.tr (PDF; 8.8 MB).

- ↑ Sina Akşin: Birinci Meşrutiyet Meclis-i Mebusanı (I). In: Ankara Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakanschesi Dergisi. Volume 25, No. 1, 1970, pp. 19-39 (30), ankara.edu.tr (PDF; 8.8 MB).

- ↑ Bülent Tanör: Osmanlı-Türk Anayasal Gelişmeleri. 18th edition. Yapı Kredi Yayınları, Istanbul 2009, ISBN 978-975-363-688-9 , p. 133.

- ↑ Bülent Tanör: Osmanlı-Türk Anayasal Gelişmeleri. 18th edition. Yapı Kredi Yayınları, Istanbul 2009, ISBN 978-975-363-688-9 , p. 164.

- ↑ Christian Rumpf: Introduction to Turkish Law. CH Beck, Munich 2004, ISBN 3-406-51293-3 , p. 25.