Prussian Lithuania

Prussian-Lithuania (in the 20th century occasionally German-Lithuania, Lithuanian: Mažoji Lietuva or Prūsų Lietuva ) refers to the area in northeastern Prussia that has been populated by Lithuanians alongside Germans, Prussians and Kurds since the last quarter of the 15th century (today roughly the eastern half of Kaliningrad Oblast , formerly largely the area of the Gumbinnen administrative district ). The area was also (before the founding of the Lithuanian state) simply referred to as "Lithuania", but between 1923 and 1939 it never belonged to the state , with the exception of the MemellandLithuania . Apart from further nationalistic claims from the past, today the Memel area with adjacent areas is sometimes referred to as Little Lithuania.

Historical and cultural importance

Supported by the Protestant Church and the Prussian state, Prussian Lithuanianism developed independently of the Catholic and strongly Polonized Grand Duchy of Lithuania .

“Due to a centuries-long history, they were firmly connected to Prussia and had little more in common with the Lithuanians who lived across the border in the Tsarist empire than the relationship of the language, some customs, songs and rural customs. They were devoutly Protestant, not Catholic like those over there, participated as farmers in Prussia's economic progress ... "

On East Prussian soil the Lithuanian written language, the first Lithuanian book, the first Lithuanian Bible, the first Lithuanian grammar, the first dictionary of the later standard Lithuanian language, the first Lithuanian university seminar, the first Lithuanian newspaper, the first scientific society for the study of Lithuanian and with Donelaitis ' Metai (Seasons) the first Lithuanian art poem.

The mostly bilingual Prussian Lithuanians called themselves Lietuwininkai (Lithuanians), while the Lithuanians in Greater Lithuania called themselves or call themselves Lietuviai . They settled mainly in the former wilderness areas of East Prussia and until the plague epidemic of 1709/10 made up the majority of the rural population there, while the Germans mainly lived in the cities.

In German usage until the end of the 19th century - when a national revival began in neighboring, then Russian Lithuania - northern East Prussia was also referred to as Litthauen / Littauen / Lithuania / Lithuania (as e.g. in Wilhelm von Humboldt's Lithuanian school plan from 1809 ). Its inhabitants were called Lithuanians, even if they were German. In 1898 a study on northern East Prussia with the title Lithuania was published in Stuttgart . A country and folklore .

"Dear reader, we're going to - LITTAUEN. At the very name I see you shiver, because you immediately think of 20 degrees below zero and three feet of snow; and at the time I am writing this it is in fact like this and not different. You immediately think of Russia and Poland, and you may not have been wrong, because Lithuania really borders on those notorious countries. But you don't have to think that it is still in Russia and Poland; No! it is still in Prussia and recently even in Germany. But you must not be ashamed of your ignorance, because some scholars not only in France but even in the German fatherland do not know better by confidently referring the Prussian administrative district of Gumbinnen to Russia. "

The presumably Kurish paternal ancestors of the philosopher Immanuel Kant and the pastor poet Christian Donalitius (Lithuanian Kristijonas Donelaitis ), who is considered a national poet in today 's Lithuania, come from Prussian-Lithuania . In the state, which has become independent from the Soviet Union since 1990, attempts are being made to build on the Prussian-Lithuanian legacy.

Since 2006, October 16 has been the state day of remembrance of the genocide of the people of Lithuania Minor , in memory of the victims of the last phase of the war, the expulsion to the west and the deportations to the east until 1949.

Political history

The area has been under the rule of the Teutonic Order since the 13th century . In the peace of Lake Melno in 1422 he had to cede parts of Sudau to the east to Poland-Lithuania and renounce further attempts at expansion. This border was to last until 1919 (separation of the Memelland in the Treaty of Versailles) or 1945. In 1525 the religious state became the Duchy of Prussia through secularization , and in 1701 the Kingdom of Prussia , later the province of East Prussia within the State of Prussia . Its territory became part of the German Empire in 1871 . While the old landscape names of the Prussian Gaue "Nadrauen" and "Schalauen" were continued for the region, the name "Litthauische Ämter" became established for the administrative districts due to the large Lithuanian population. These were combined with Masuria from 1736 to 1807 in the "Lithuanian War and Domain Chamber" (also called "Province of Lithuania", from 1808 administrative district of Gumbinnen ) under a "Royal Lithuanian Government". When the new district was formed in 1818, the area with a Lithuanian-speaking population comprised the 10 districts of Memel , Heydekrug , Niederung , Tilsit , Ragnit , Pillkallen , Insterburg , Gumbinnen , Stallupönen and Darkehmen .

In the second half of the 19th century, East Prussia provided decisive impulses for the national rebirth in Russian Lithuania. The political will to live together with Greater Lithuanians in their own state did not develop, however, because the "Little Lithuanians" saw themselves as subjects and members of the Prussian state or as East Prussians. This was particularly evident in the election results of the Memelland annexed by Lithuania in 1923, in which pro-German parties always received between 80 and 90 percent of the votes.

The ethnic group, characterized by the rural way of life, did not succeed in developing its own intellectual class. Education and social advancement were only possible through assimilation into the German environment. Further immigration (including from Salzburg and French-speaking Switzerland ) resulted in a multi-ethnic population that was eventually absorbed into Germanness. The Lithuanian language lasted longer only north of the Memel .

In 1945 the area south of the Memel became Kaliningrad Oblast and the entire population, unless they had fled beforehand, was expelled, deported or murdered by the Red Army. The area north of the Memel was annexed to the Lithuanian Soviet Republic . There was no general expulsion of the Prussian Lithuanians here. “Memel countries” who stayed at home and returned - Kossert estimates their number at 15,000 to 20,000 people - were able to remain in their home country in 1947 by accepting Soviet citizenship. After the conclusion of the German-Soviet treaty of June 8, 1958, around 6000 Memel countries moved to the Federal Republic by 1960. About the same number of Prussian Lithuanians ultimately stayed in Lithuania.

The fate of the farmer Jan Birschkus , who built up one of the largest Lithuanian book collections, stands for her life .

“The collection of the farmer Birschkus (1870–1959) with a total of approx. 1,300 volumes was burned when the Red Army conquered the Memelland in 1945. The fate of this important Prussian-Lithuanian activist is characteristic of Soviet Lithuania. Birschkus lived in Memelland until 1959, but today it is no longer possible to determine where and how. Nobody was interested in him after 1945. His grave was recently destroyed. This is one more sign of how the Prussian-Lithuanians got caught between stools: the Nazis persecuted them because of their Lithuanian language and attitude, the Soviets saw in them Germans, the Greater Lithuanians did not understand their difference and did not care about them. So their unique culture gradually disappeared after the First World War and has to be laboriously reconstructed today. "

Especially at the "Research Center for the History of Western Lithuania and Prussia" founded in 1992 or its successor, the "Institute for History and Archeology of the Baltic Sea Region", which has existed at the University of Klaipėda since 2003, is now concerned with Prussian-Lithuanian history . This cultural heritage is not maintained in Germany.

Settlement history

Around 1400 the area of the later Prussian Lithuania, devastated by the crusades ( Prussian trips and Lithuanian wars of the Teutonic Order ), was wilderness and apart from the remains of settlements of the autochthonous population, Prussian Schalauers and Nadrauern near the order castles and Alt- Kuren (on the Curonian Lagoon and near Memel) , uninhabited. After the defeat of the Teutonic Order in the Battle of Tannenberg (1410) and the establishment of a border with Poland-Lithuania (1422), the repopulation of the wilderness area began. Initially, a few Prussians (also called Pruzzen or Old Prussia) and Germans settled there; fishermen who had immigrated from Latvia settled on the Baltic Sea coast, the later "Nehrungs-Kuren". Bezzenberger calls them "Prussian Latvians" because their Nehrungskurisch is based on a Latvian dialect. In the last quarter of the 15th century, after the Second Peace of Thorens (1466), the immigration of Lithuanians, especially from Shamaites, or the assumed return of Prussians who had fled to Lithuania, began. In the surviving archives of the order, 1050 new land grants are documented up to 1540, only one of them to a German. The main immigration of Lithuanians to Prussia is considered complete around 1550. The settlement geographer Mortensen sees it as the very last phase of the great migration. It was not reasons of faith that were decisive for their settlement in Protestant Prussia, but rather, in addition to better economic conditions, the increasing spread of serfdom in their old homeland. In some cases, the order also targeted recruiting of new settlers and prevented peasants who had fled to Prussia from being returned to their noble masters. The Lithuanian settlers are estimated at around 20,000 to 30,000 people in the mid-16th century. Their names are almost completely preserved in the Turkish tax lists . The further development of the Great Wilderness now mainly took place through internal migration and extended into the first quarter of the 17th century.

During the second Swedish-Polish war in 1656/57, Tatar auxiliaries of the Polish king invaded the country. 11,000 people were murdered and 34,000 dragged into slavery. 13 cities and 249 villages were destroyed. The famine and epidemics that followed killed another 80,000 people.

During the plague epidemic of 1709/10 , around 160,000 - mainly Lithuanians - of the approximately 300,000 inhabitants of the so-called "Lithuanian Province" died, the Memel area was less affected by the epidemic. In the course of the " retablissement " carried out by King Friedrich Wilhelm I , around 23,000 recruited new settlers ( Salzburg exiles , German and French-speaking Swiss , Nassau and Palatinate ) took over the desolate farms, mainly in the main office of Insterburg. The coexistence of these different ethnic groups went without tension.

“In the southern part of the province, the so-called Masuria, lived a tribe that had lived in for centuries and spoke corrupt Polish, but was the declared opponent of the Poles themselves because of their religion and customs. In the center of the government district, on the other hand, there lived Lithuanians, Germans, immigrant Salzburgers, Swiss, French, and in the northern part a Curonian tribe. Back in 1796, all of these still had their own language and customs, seldom married each other and yet lived contentedly under one law. I am citing the latter mainly because at the moment when I am writing this, a party, admittedly out of easily comprehensible private intentions, wants to pass it off as an impossibility for different ethnic groups to live happily under a wisely drafted general national law and a province could exist without nobility. Go there and see! "

Aided by the nationwide literacy that was carried out up to 1800, an assimilation into Germanness began.

Population and school statistics in the administrative district of Gumbinnen 1817 to 1825:

| native language | 1817 | 1825 | absolute change | percentage change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| German | 177,798 | 229,531 | 51,733 | 29% | |

| lit. | 91,301 | 102.134 | 10,833 | 12% | |

| polish | 108.401 | 133,034 | 24,633 | 22.5% | |

| Total population | 377,500 | 464.699 | 87,199 | 23% | |

| Language of instruction for school-age children from 6 to 14 years of age | 1817 | 1825 | absolute change | percentage change | |

| German | 27,284 | 36,057 | 8,773 | 32% | |

| lit. | 11,540 | 11,394 | −146 | −1.3% | |

| polish | 16,547 | 21,271 | 4,724 | 28.5% | |

| Total number of students | 55,371 | 68,722 | 13,351 | 24% |

Regarding the noticeably strong decline in the number of pupils in Lithuanian-language lessons compared to Polish lessons, there is a contemporary comment that German lessons were gladly accepted by Lithuanian children.

According to Vileisis, the total number of Lithuanian speakers was 149,927 in 1837 and 151,248 in 1852. From the middle of the 19th century many East Prussians emigrated - especially from the Gumbinnen area - to other parts of Prussia ( Berlin , Ruhr area ). The Prussian census of 1890 showed 121,345 people with a Lithuanian mother tongue.

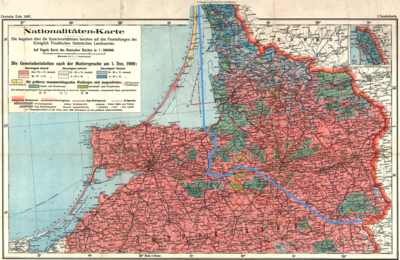

Language and settlement border

How far south the East Prussian Lithuanians settled in their history can be determined with the help of the records of the service given in Lithuanian. This ethnographic border (according to Algirdas Matulevičius, described by a line between the places Heiligenbeil - Zinten - Prussian Eylau - Bartenstein - Laggarben - Barten - Angerburg - Kutten - Gurden) corresponds roughly to the current political border between the Kaliningrad area and Poland. The city of Angerburg was trilingual at that time: German, Polish and Lithuanian.

Friedrich Kurschat describes the language area as follows in 1876:

“The border of the Lithuanian language area goes from its northernmost point on the Baltic Sea, for example from the Russian border town Polangen in a southerly direction to Memel along the Baltic Sea, from there along the Curonian Lagoon and the Deime River to Tapiau . From there it stretches along the Pregel as far as Wehlau to Insterburg , between which two cities it crosses this river, then strikes in a south-easterly direction and in the area of Goldap it crosses the Polish border in an easterly direction . "

By 1900 the border to the purely German-speaking area had shifted very far to the north. According to Franz Tetzner, 120,693 East Prussians spoke Lithuanian as their mother tongue in 1897. By 1910, their number fell to around 114,000 of the 1.4 million inhabitants of the administrative districts of Königsberg and Gumbinnen. Around 1900 a little over half of the Prussian Lithuanians lived north of the Memel.

Flight and expulsion, especially of the Prussian Lithuanians living south of the Memel, and their scattered settlement in Germany after 1945 destroyed their language community.

Place names

The Lithuanian settlement is reflected in many East Prussian place and river names. Village names often end in "-kehmen" (as in Walterkehmen, from 1938 Großwaltersdorf), from kiemas (Prussian-Lithuanian "Hof", "village"), rivers on "-uppe", from Lithuanian upė ("river, stream") like in "Szeszuppe".

New place names also result from the diverse uses and changes in the forest landscape by humans.

"They show how remote (Tolminkemen) and how in the middle of the forest (Widgirren) or hazel bushes (Lasdinehlen) cleared (Skaisgirren), birch tar is extracted (Dagutehlen, Dagutschen), tar is burned (Smaledunen, Tarerbude, Smaleninken), like wood piles coal ( Trakehnen, Traken, Trakininken) and by burning out (Ischdagen) or turning over (Ischlauzen) the forest has been reduced (Girelischken) and the heather has been made habitable (Schilenen, Schilgalen). "

The new Lithuanian place names appearing in the historic settlement area of the Prussian Nadrauer, Schalauer and Sudauer led to an ongoing controversy among historians as to whether the Lithuanians of East Prussia were autochthonous. The starting point of the dispute was the article "The Lithuanian-Prussian border" by Adalbert Bezzenberger from 1882, in which the latter did not take into account the younger age of these Lithuanian place names. The doctrine established by him of the "Deime limit" as an old Lithuanian settlement border along the Pregel, the Alle, the Angerapp and the Goldap River as far as the Dubeningken area, was adopted by Paul Karge (The Lithuanian Question in Old Prussia, 1925) and finally by Gertrud Heinrich (Contributions to the nationality and settlement conditions of Pr. Lithuania, 1927) refuted.

From 1938 the National Socialists replaced many of these old Baltic names with ahistorical German ones . In the Third Reich, investigations into the settlement history of East Prussia were subject to censorship. The third volume by Hans and Gertrud Mortensen on the settlement of the Great Wilderness was not allowed to appear; because they gave evidence of an almost exclusively Lithuanian settlement up to the 17th century.

Only a few of the current Russian place names that were newly established under Stalin after 1945 with reference to a propagated “original Slavic soil” have any reference to the old names of Prussian, German or Lithuanian origin.

Examples of changed place names:

| Lithuanian | Germanized | renamed German | Russian renamed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Budviečiai | Budwehten | Altenkirch | Malomoshaiskoje |

| Gavaičiai | Gawaiten | Herzogsrode | Gavrilovo |

| Kraupiškas | Kraupischken | Breitenstein | Ulyanovo |

| Lazdenai | Laser stretching | Haselberg | Krasnosnamensk |

| Pilkalnis | Pillkallen | Schlossberg | Dobrovolsk |

| Stalupėna | Stallupönen | Ebenrode | Nesterow |

The village of Pillkallen, however, is not a Lithuanian establishment, the name is rather a Lithuanian translation of the place name "Schloßberg", which already existed in the times of the order.

Language history

In order to enforce the Protestant doctrine, the last high master of the order, as secular Duke Albrecht I of Prussia, had ecclesiastical writings translated into Lithuanian and Prussian. This started a long tradition of promoting the Lithuanian language by church and state. This policy corresponded to Luther's demand for the preaching of the Gospel in the mother tongue and helped the Lithuanian language in East Prussia - in contrast to the Grand Duchy or Russian Lithuania - to develop continuously from the 16th to the middle of the 19th century, which also resulted in a standardization of the language a castle. The resulting Prussian-Lithuanian written language, August Schleicher calls the dialect on which it is based "Southwestern Aukschtaitisch" (Aukschtaitisch = High Lithuanian), later became the basis of modern Lithuanian. The East Prussian pastors - often Germans - played a prominent role in this development.

The translation of the Lutheran catechism by Martin Mosvid (Königsberg 1547), a native Shamaite , was the first book in the Lithuanian language - in the neighboring Grand Duchy of Lithuania, Polish and Ruthenian were used as written languages ; the first Lithuanian book did not appear there until around 50 years later.

The Wolfenbütteler Postille , the first Lithuanian collection of sermons and at the same time the first coherent handwritten Lithuanian text, dates from 1573 . It includes 72 sermons for the entire church year. It has been in the Herzog-August-Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel since 1648/1649.

“The most important document of ancient Lithuanian language, church and cultural history” (Range) is the manuscript translation of the Bible (1579–1590) by the German-born pastor Johannes Bretke . The corrections that other pastors have made to the text provide important insights into the history of the language of Lithuanian and its dialects. Bretke mastered the three Baltic languages spoken in East Prussia in a unique combination , alongside Lithuanian the language of his mother, a Prussian, and Curonian, a Latvian dialect spoken on the East Prussian coast. The Lithuanian writings he left behind alone represent about half of the entire Old Lithuanian language corpus preserved from the 16th century. Bretke's translation of the Bible was never printed, the manuscript is now kept in the Secret State Archives of Prussian Cultural Heritage. In 2013, the facsimile edition of this unique cultural and historical monument was completed.

The beginning of a standardization of Lithuanian on Prussian soil took place through the Lithuanian grammar of the Tilsit pastor Daniel Klein (Latin version 1653, German version 1654) commissioned by the Great Elector.

In 1706 there was a journalistic dispute between three East Prussian pastors regarding a reform of the Lithuanian church language by approximating the vernacular. The Gumbinn pastor Michael Mörlin made suggestions in his treatise Principium primarium in lingva Lithvanica , which his colleague Johann Schultz from Kattenau implemented in a translation of several of Aesop's fables: He became the author of the first secular Lithuanian book. The pastor of Walterkehmen Jacob Perkuhn published a critical reply under the title Well-founded concerns about the ten fables Aesopi translated into Lithuanian and the same passionate letter . However, the problem of a church language deviating from the colloquial language remained unsolved. Until the 20th century there are reports of Lithuanian churchgoers shaking their heads who only understood half of the sermons of their pastors.

The classically educated pastors noticed the many similarities between Lithuanian on the one hand and Latin and ancient Greek on the other. In his consideration of the Lithuanian language, in its origin, nature and properties (Königsberg 1745) one of them, Philipp Ruhig from Walterkehmen, made a first attempt at a linguistic and historically comparative description of Lithuanian.

In 1796 Daniel Jenisch's philosophical-critical comparison and appraisal of 14 older and more modern languages of Europe appeared, namely: Greek and Latin; Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, French; English, German, Dutch, Danish, Swedish; Polish, Russian, Lithuanian , in which - as from today's point of view - he not only considered all the languages mentioned as related to one another, but also traced their main tribes back to an original language. He sees Old Prussian, Latvian and Lithuanian as a separate language strain, albeit closely related to the Slavic languages. In 1845 the Königsberg professor Nesselmann gave this language group the collective name "Baltic".

Jacob Brodowski's Lexicon Germanico-Lithuanicum , which has been preserved as a manuscript and comprises more than a thousand pages and contains valuable encyclopedia-like factual information, dates from the first half of the 18th century .

The first aesthetic work in Lithuanian, Metai , (Seasons) was created in the second half of the 18th century in the village of Tollmingkehmen. The author of the satirical-didactic poem, written in hexameters, is Pastor Christian Donelaitis, a graduate of the Lithuanian Seminary in Königsberg. The work, published posthumously by Ludwig Rhesa at the suggestion of the Prussian Minister of Culture Wilhelm von Humboldt in 1818, is an occasional poem and describes - sometimes very drastically - the life and environment of East Prussian-Lithuanian crowd farmers in four chants dedicated to the seasons. The UNESCO took Metai 1977 in the library of the European on literature masterpieces.

While fleeing from Napoleon, the Prussian royal couple stayed in Memel in 1807/1808. The devotion shown to him by the Lithuanian population and their complaints prompted the king to found the Karalene educational and teacher training institute ("Queen", in honor of Queen Luise) and a scholarship foundation for talented young Lithuanians. Due to the unfortunate economic situation after the liberation wars, the increased scholarship foundation and a disposition fund for the promotion of the Lithuanian language and folk literature could not be implemented until 1844.

Wording of the royal decree of January 12, 1844:

“From your report of 15. M. I have seen that my Lord Father's Majesty, resting in God, in the paternal care of the faithful Litthau subjects by the following ordinance of March 22, 1807, ordered that 6 boys from indigenous Litthau country people at public expense in schools and Universities educated and instructed, then trained for practical civil service and, depending on their qualifications, preferably employed in Lithuania. The execution of this order, which had already been made known by reading from the pulpit in the churches of Littau, was not carried out given the distressed situation of the state at the time. I want to carry out the noble project, with the realization of which my most blessed father's majesty was prevented by the unfavorable time, now with favorable time conditions, and in order to compensate the loyal Litthauer for the long deprivation of the welfare intended for them, with joy in extended scope . At the end I hereby approve an annual sum of 3,000 thalers from the state fund, from which twelve young people of the Littaui tribe receive scholarships of an average of 200 thalers for their education at schools and universities, which, however, can be distributed according to need The remaining 600 Thaler should be allocated to a disposition fund to promote knowledge of the Lithuanian language. I determine half of the scholarships for young people who want to devote themselves to the clergy or school matters, the other half for those who want to devote themselves to civil service. For those who will acquire the necessary qualification for this, I want to renew the assurance of preferential employment in the districts of Lithuania. The young Litthauers chosen to enjoy those scholarships are to receive their grammar school lessons at the grammar school in Tilsit; the planned disposition fund is also to be connected to this grammar school, and to remunerations for teachers who care about the Lithuanian language that it is through earn your own writings, or through translations of non-profit works into this language, and be used to disseminate the latter among the people. It is possible to work towards finding teachers for the grammar school in Tilsit, or to train them in the way described above, who are completely equal to the Lithuanian language next to the German, thus in this way a living center for the preservation of this language and a Folk literature will be created in the same. I instruct you to prepare the rest of the implementation of this plan, to enter into communication about it with the Finance Minister, and jointly with the latter and in competition with the other department heads involved, with regard to the young people to be trained in the judiciary and administrative service to submit the specific proposals required. "

The scholarship holders included a. the philologist and local researcher Alexander Kurschat, author of a four-volume thesaurus linguae lituanicae , the two pastor Wilhelm Gaigalat, who also worked in philology (doctoral thesis on the Wolfenbütteler Postille, member of the Prussian House of Representatives) and Jonas Pipirs (Lithuanian language teaching) , as well as the later Foreign Minister from East Prussia Dovas Zaunius.

In the 19th century, linguists from all over Europe became aware of the archaic language in the easternmost part of Germany. It became an important part of the evidence for the relationship of the Indo-European languages. Above all, the established similarities with the spatially and temporally distant Sanskrit underlined the conservative character of Lithuanian.

German: God gave teeth, God will give bread .

Lithuanian: Dievas davė dantis, Dievas duos duonos.

Sanskrit: Devas adat datas, Devas dasyati dhanas.

Latin: Deus dedit dentes, deus dabit panem.

The Königsberg professors Ludwig Rhesa , Friedrich Kurschat and Georg Nesselmann published the first scientific papers on Lithuanian. Friedrich Kurschat, himself of Prussian-Lithuanian descent, became the founder of Lithuanian accentology with his work “Contributions to the knowledge of the Lithuanian language” (1843). In 1852 the Indo-Europeanist August Schleicher undertook a longer study visit to East Prussia. Meyer's Konversationslexikon wrote in 1889 about Schleicher's achievements:

- “The Lithuanian language is already dealt with in Bopp's comparative grammar, but the famous linguist Schleicher was the first to systematically seek to unearth this treasure by undertaking a kind of expedition to Lithuania [meaning Prussian Lithuania] in 1852 with the support of the Austrian government and elicited the ancient forms of their language as well as various of their popular songs (dainos), fables and fairy tales from the peasants through queries. He put the results of his journey down in an excellent 'Handbook of the Lithuanian Language', the first part of which contains the grammar (Prague 1855), the second the reader with glossary (1856). For the purpose of comparing languages, Schleicher used Lithuanian itself in his 'Compendium of Comparative Grammar' (4th edition, Weimar 1876) ... "

As head of the Lithuanian seminar at the University of Königsberg, Friedrich Kurschat finally published a grammar (1876) in addition to an extensive German-Lithuanian dictionary (1870). Both works were intended to promote the knowledge of the Lithuanian language, which at that time already appeared to be severely endangered, among Germans. Kurschat (1806-1884) also published the first Lithuanian newspaper with a wider circulation, Keleiwis (Wanderer, 1849-1880). Until the beginning of the 20th century, Prussian Lithuanian was "the most uniform, best-developed Lithuanian written, literary and official language" (Erich Hoffmann). When a national consciousness arose in Russian Lithuania towards the end of the 19th century, Prussian Lithuanian became the basis of the efforts to establish a state language there. The language was initially adapted to the needs of Tsarist Russia and further codified and modernized in the 20th century after the founding of the modern Lithuanian state.

The decline in the number of Lithuanian speakers in East Prussia could not be stopped. The agrarian reforms carried out in Prussia at the beginning of the 19th century made the previously mostly official and only 8.5% subordinate Lithuanian farmers liberal and many into landowners (large farmers). Leaving the rural milieu, military service, urbanization, mixed marriages, the German educational world and social advancement resulted in a Germanization that was not imposed on the Prussian Lithuanians. For educational reasons, however, the East Prussian administrative authorities sought after 1815 that all school children also spoke German. It was believed that the Lithuanian peasant language was not capable of abstractions and prevented an increase in the level of education and thus participation in public life. The conservative pastors, however, saw pedagogical and moral dangers in the suppression of the mother tongue.

Since the middle of the 19th century at the latest, it has been possible to assume bilingualism in the majority of the “Lietuvininkai”, which also applied to Germans in close proximity to Lithuanians. This can be seen not least from the fact that fewer and fewer churches were also preaching in Lithuanian. In Ischdaggen, for example, this tradition ended in 1874.

In the course of the establishment of the empire in 1871, Prussia finally gave up the caring attitude it had exercised over centuries towards its non-German ethnic groups. Despite their Protestant faith and their loyalty to the Prussian royal house, the Prussian Lithuanians suffered from Bismarck's culture war. In petitions to the emperor, they turned against the dismantling of native language teaching.

From a Lithuanian petition to the Kaiser on May 11, 1879:

“We poor beleaguered Littauers want our children to be taught in German, we only want religious teaching and the reading of holy scriptures to be Lithuanian. We also want to get to know the language of our dear compatriot, whom we are so fond of and love so dearly, that is why we also know that our children's babbling in their mother tongue is not taken away from them. We would like to know the language that educates German heroes, but we don't want to lose the core of our language, which is planted in our hearts by nature. We would like to know the language that is known to many millions on the earth, but we do not want to forget what one brother speaks to the other from the heart in the future; for once our language, which nature has put in our hearts, is destroyed, the greatest art will no longer succeed in restoring it in all its dignity. "

In 1878 a Lithuanian delegation accompanied by Georg Sauerwein was received by Kaiser Wilhelm I. The Crown Prince, who later became Emperor Friedrich III, noted the visit in his diary:

“It was difficult to look at the unaffected heartfeltness of such love and gratitude, and to listen to its expression without tears welling up in your eyes at the thought of the recent efforts of various sides in East Prussia to quickly eradicate the old, venerable ones Language with its folk songs of unaffected, unspoiled natural power and deepest religious belief. "

In the Polish-speaking area, teaching in the mother tongue was completely banned in 1887. In the administrative district of Gumbinnen, however, the 1873 regulation that provided for Lithuanian-language religious instruction in the lower grades and Lithuanian reading and writing classes in the middle grades was retained. The extent to which these Lithuanian lessons could be implemented on site depended on the parents' will, the class composition and the skills of the teachers.

No further concessions were made to the Lithuanians, who were loyal to the state, because the German-Polish relationship came to a head at the turn of the century.

In the late 1870s, standardized language samples, the so-called Wenkerbogen, were collected in schools for the German Language Atlas . Today they allow us an insight into the prevalence of East Prussian Lithuanian and its two main dialects, the Aukschtaite and West Shamaite.

Saving the threatened language for science was the goal of the Lithuanian Literary Society founded in 1879 (this is the original spelling, later: Lithuanian Literary Society ). She published collections of folk poetry such as folk songs (Dainos) , fables, fairy tales, proverbs and riddles , especially in her magazine, the Mittheilungen der Lithuanian Litterarian Society . Members were u. a. Adalbert Bezzenberger , August Bielenstein , Franz von Miklosich , Friedrich Max Müller , Ferdinand Nesselmann , August Friedrich Pott and Ferdinand de Saussure . The company was dissolved in 1925. Its last chairman, Alexander Kurschat (1857–1944), saved the manuscript for a large four-volume Lithuanian-German dictionary despite the war and expulsion to the West. The fourth volume, published in 1973, is the last evidence of Prussian-Lithuanian.

"Call for the formation of a Lithuanian literary society:

The Lithuanian language, one of the most important for linguistics, is rapidly approaching its decline, at the same time harassed by German, Polish, Russian and Latvian, it will only exist for a short time. With it, the peculiarity of a people that temporarily ruled northern Europe disappears, with it its customs, sagas and myths, with it its poetry, which attracted the attention of a Herder, was imitated by a Chamisso.

Science, whose task it is to look after the existing, and to at least keep a picture of what has fallen into ruin according to the laws of nature and the development of history, has long since taken a position on this question, has for some time Scholars, some of the first class, devoted their energies to Lithuania and tried to solve those problems with her; But the picture that you have drawn of Lithuania is still often shadowy and blurred, the yield in this area is just too rich for the treasures to be raised and shaped by the work of individuals. This is possible only through the planned and unanimous action of a community, a community which unites the forces of all those involved, establishes a living connection between them and their work, and knows how to arouse and enliven Lithuania to the greatest extent.

On the basis of these considerations, the undersigned call for the formation of a society which, in the manner of the Latvian Literary Society, the Association for Low German Linguistic Research, etc. would be active. In doing so, you are addressing first of all those who have a sense and sympathy for the Lithuanian being by tradition or occupation, but further to all who are concerned that what has so often happened to the detriment of historical research does not repeat itself before our eyes: that a whole people, which deserves our respect and sympathy, will perish unworthily and without a trace (Tilsit 1879). "

In 1891 the Sanskritist Carl Cappeller, who was descended from East Prussian Salzburgers, published fairy tales from the Stallupönen area, which he had collected many years earlier . He remarked resignedly about her linguistic state:

“Nobody can escape the fact that the dialect of southern Prussian Lithuanian, which once formed the basis of the written Lithuanian language and in which Donalitius wrote, is already in complete degeneration and disintegration. But I am of the opinion that the language is worthy of the researcher's attention even at this stage, despite or perhaps because of its stunted vocabulary, its broken syntax and its crass Germanisms. "

The Lithuanian linguist Zinkevicius sees the faulty Lithuanian linguistic usage of the German-educated Lithuanian intellectuals, which was imitated by ordinary people, as the reasons for the linguistic decline due to the influence of German. The poor language skills of the pastors, especially Germans who spoke German-Lithuanian jargon, also had a negative effect.

vocabulary

The Prussian Lithuanian has acquired fiefdom from contact with the German and Slavic languages, especially Ruthenian and Polish. The Slavisms include u. a. "All expressions relating to the Christian religion, Christian festivals, days of the week, church matters, social orders and the like" (F. Kurschat). The Slavisms are therefore proof that the Prussian Lithuanians were not autochthonous, but immigrated to northern East Prussia.

The names of the days of the week e.g. B. are panedelis (Monday, see Belarusian panyadzelak , Polish poniedziałek , Czech pondělí ), utarninkas (see Belarusian aŭtorak , Polish wtorek , Czech. Úterý ), sereda (see Belarusian Sierada , Polish środa , Czech. středa ), ketwergas , petnyczia , subata , nedelia (after Kurschat, 1870). In the former Russian Lithuania, in the course of the language reform at the beginning of the 20th century, the even more numerous Slavisms there were erased and replaced by Lithuanian but ahistorical formations: pirmadienis (Monday - literally "first day"), antradienis (Tuesday - literally "second day"), treciadienis , ketvirtadienis , penktadienis , sestadienis , sekmadienis .

Words borrowed from German are linguistically adapted to Lithuanian and given Lithuanian endings: popierius - paper, kurbas - basket, zebelis - saber, apiciers - officer, pikis - bad luck, kamarotas - comrade, kamandieruti - command.

In addition to old Lithuanian words from the peasant world, there are now German equivalents, such as B. for month names:

- Januarijis next to wasaris , ragas or pusczius from pusti "blow".

- Februarijis next kowinis (Dohle month), rugutis or prydelinis .

- Mercas next to karwelinis or balandinis (pigeon month).

- Aprilis next to sultekis (birch month ) or welyku-menu (Easter month ).

- Meijis next to Geguzinis (cuckoo month ) or ziedu-menu .

- Junijis next to pudimo-menu ( fallow month), sejinis (sowing month), semenys (flax month) or wisjawis .

- Julijis next to liepinis (linden month) or szienawimo-menu .

- Augustas next to degesis ( heat month ) or rugpjutis (harvest month ).

- Septemberis next to rudugys (autumn month), rugsejis , wesselinnis (cooler month) or pauksztlekis .

- Oktoberis next to lapkritis (month when the leaves fall) or spalinis .

- Nowemberis next to grudinis (frost month ).

- Decemberis next to sausis (dry month) or kaledu-menu (Christmas month ).

In the private sphere, too, a delightful mixture of Lithuanian and German is created for outsiders.

- "Kur foruji?" (Where are you going?)

- "I miesta ant verjnyjes." (To the city for pleasure.)

- "Well, tai amyzierukis!" (Well, then have fun !)

orthography

Printed matter such as newspapers, bible, catechism, hymn book and other popular writings appeared - in contrast to Greater Lithuania - in German script , but was written in Latin script.

Prussian-Lithuanian family names

They have been in existence since the 16th century, a century earlier than family names in neighboring Poland-Lithuania. In German they often lose their original endings. The name Adomeit z. B. goes back to the form of adomaitis . It is created by adding the patronymic suffix -aitis to the first or family name Adomas (Adam). This originally had the meaning "son of ...". As a family name, the derived form has usually prevailed (see Germanic names such as Johnson or Thomson). The wife of Adomeit is called Adomaitiene , the daughter Adomaitike (also Adomaityte ). The members of the East Prussian Adomeit family answered the question about their names as follows: Ansas Adomaitis (the father Hans Adomeit), Barbe Adomaitiene (the mother Barbara Adomeit), Pritzkus Adomaitis (the son Friedrich Adomeit) and Urte Adomaitike (the daughter Dorothea Adomeit ). The most common endings of Prussian-Lithuanian family names in Germany are -eit, -at, - (k) us and -ies.

- Since, in contrast to German, Lithuanian has no article and no strict word order, the grammatical relationships in the sentence are expressed using endings. This also applies to proper names. There are seven cases:

- Nominative: RIMKUS yra geras vyras = Rimkus is a good man.

- Genitive: Ši knyga yra RIMKAUS = This book belongs to Rimkus.

- Dative: Perduok šią knygą RIMKUI! = Give this book to Rimkus!

- Accusative: Pasveikink RIMKų su gimtadieniu = Congratulate Rimkus on his birthday.

- Instrumental: RIMKUMI galima pasitikėti = We can trust Rimkus.

- Locative: RIMKUJE slepiasi kažkokia jėga = There is power in Rimkus.

- Vocative : RIMKAU, eik namo! = Rimkus, go home!

- Name endings of the son, they can vary regionally, in East Prussia -ATIS and -AITIS predominate, -UNAS is less common:

- N. Rimkūnas, Rimkaitis

- G. Rimkūno, Rimkaičio

- D. Rimkūnui, Rimkaičiui

- A. Rimkūną, Rimkaitį

- I. Rimkūnu, Rimkaičiu

- L. Rimkūne, Rimkaityje

- V. Rimkūnai! Rimkaiti!

- Name endings of a married woman: Rimkuvienė, Rimkuvienės, Rimkuvienei, Rimkuvienę, Rimkuviene, Rimkuvienėje, Rimkuviene

- Endings of an unmarried woman's name: Rimkutė, Rimkutės, Rimkutei, Rimkutę, Rimkute, Rimkutėje, Rimkute

- In addition to the plural forms in East Prussia, there are also the forms of the dual, which have disappeared in today's Lithuanian

- There are German-Lithuanian mixed forms such as tailoring, shoemaking, bakerying, Fritzkeit, Dietrichkeit, Müllereit, Cimermonis, Schulmeistrat, Schläfereit, Burgmistras

- Many family names arise from Christian first names: Ambrassat (Ambrosius), Tomuscheit (Thomas), Kristopeit (Christoph), Stepputat (Stephan), Petereit (Peter), Endruweit (Andreas), Simoneit (Simon).

- Professional names are Kallweit (blacksmith), Kurpjuhn (Schumacher), Podszus (potter), Laschat (Scharwerker), Krauczun (tailor), Krauledat (Aderlasser)

- Names that indicate the origin are Kurschat (Kure), Szameit (Schamaite), Prusseit (Prussia), Lenkeit (Pole).

- Names of animals and plants: Wowereit (squirrel), Awischus (oat man), Dobileit (clover), Schernus (boar), Puschat (pine), Schermukschnis (mountain ash), Kischkat (hare)

- Names denoting physical and mental characteristics: Didschus (large), Rudat (red-brown), Kairies (left-handed), Mislintat (thinker)

- Some names of foreign origin can also be lithuanized: French Du Commun becomes Dickomeit , the Swiss name Süpply becomes Zipplies

- Finally, names of the autochthonous Prussian population can be covered up in Lithuanian (Scawdenne-Schaudinn, Tuleswayde-Tuleweit, Waynax-Wannags, Wissegeyde-Wissigkeit), some names are common to Prussian and Lithuanian.

- The most common German name of Prussian-Lithuanian origin is Lithuanian “naujokas” (German “Neumann”) with its variants Naujocks , Naujoks , Naujox , Naujock , Naujok , Naujokat , Naujokeit and Naujack (2690 mentions on verwandt.de ); the most common name in Lithuania itself, Kazlauskas , only has 1857 mentions (Lithuanian telephone directory 2004).

The Balticist Christiane Schiller estimates the number of people with Lithuanian family names in Germany at up to half a million.

Bearer of Prussian-Lithuanian family names

- Dirk Adomat , German politician (SPD)

- Wulf Bernotat , German manager and former CEO of E.ON AG.

- Erich Dunskus , German film and theater actor

- Wilhelm Gaigalat (Lithuanian Vilius Gaigalaitis), Prussian-Lithuanian pastor and member of the Prussian House of Representatives

- Georg Gerullis , German Baltist

- Martynas Jankus , mostly German Martin Jankus, Prussian-Lithuanian printer owner and publicist

- Herbert Jankuhn , German prehistorian

- Daniel Jurgeleit , German soccer player

- Ursula Karusseit , German actress

- John Kay (Fritz Krauledat), lead singer of the rock group Steppenwolf

- Jürgen Keddigkeit , German historian

- Christoph Kukat , East Prussian evangelist and penitential preacher

- Lothar Kurbjuweit , German soccer player

- Sven Mislintat , German football official and player observer

- Bodo Rudwaleit , German soccer player

- Heinrich Schlusnus , German opera and concert singer

- Gerd Siemoneit-Barum , German circus director

- Max Simoneit , German military psychologist

- Jonas Smalakys , Prussian-Lithuanian member of the Reichstag, landowner, participant in the Italian struggle for independence

- Wilhelm Steputat , German writer, member of the Prussian House of Representatives and state president in the Memelland state directorate

- Klaus Theweleit , German literary scholar, cultural theorist and writer

- Lena Valaitis , German-Lithuanian pop singer

- Vydūnas (bourgeois Wilhelm Storost) Prussian-Lithuanian teacher, poet, philosopher, humanist and theosophist

- Ulrich Wannagat , German chemist

- Reinhard Wenskus , German historian

- Dietmar Willoweit , German legal scholar and legal historian

- Günter Willumeit , German humorist, parodist and entertainer

- Klaus Wowereit , Governing Mayor of Berlin

Quotes

- In the Insterburg office there were “... almost only Lithuanians who are a strong people and who are godly in their own way, who honor their pastors, are obedient to the authorities and willingly do what they are obliged to do. But if they are burdened beyond that, they stick together and become defiant like bees ... and whether they are also loaded with the tiresome drinking truck, which is very common in these countries, so also that they are temporarily full, boy, Old people, men, women, servants, maidservants, just like the cattle lying together on the litter, but without knowing any fornication from them. "( Caspar Henneberger , 1595, quoted from Willoweit)

- “I add to this: that he / the Prussian Lithuanian / von Kriecherey is further away than the peoples neighboring him, is used to speaking with his superiors in a tone of equality and confidential frankness; which they do not resent or refuse to shake hands, because they find him willing to do everything cheap. A pride quite different from all arrogance, or from a certain neighboring nation, if someone is noble among them, or rather a feeling of his worth, which indicates courage and at the same time guarantees his loyalty. ”( Immanuel Kant , 1800; he was three Private tutor in Judtschen near Gumbinnen for years )

- “… Brandenburger, Prussians, Silesians, Pomeranians, Litthauer! You know what you have endured for almost seven years; You know what your sad lot is if we do not end the beginning struggle with honor. Remember the past, the great Elector, the great Frederick. Remain in mind of the goods that our ancestors fought for bloodily among you: freedom of conscience, honor, independence, trade, hard work and science ... "(Call of the King of Prussia Friedrich Wilhelm III." To my people "at the beginning of the wars of liberation against France from 17. March 1813)

- “People should not be cherished just for the sake of rarity like elephants, but should move on to higher education; so the Litthauer will disappear in Prussia. "(Friedrich Förster 1820)

- “... the fact that Lithuanian is such a lovely, cozy and gentle language, since it has not yet developed into a written language, cannot justify its existence. It has not a single original work, even Donaleiti's seasons are a consequence of Germanic education and are not free from Germanisms; and now the language has already been completely Germanised and is losing its character of peculiarity more and more. (...) We do not find anything unnatural in it if the Prussian state successfully works on the extinction of the secondary languages and makes German education and language general. "(Preußische Provinzial-Blätter 3, 1830)

- “130 years ago these areas of land may only have been inhabited by Litthauer, it was only after the great plague of 1709 and 1710 that German colonists began to occupy these then completely depopulated areas. From then on, however, the Litthauer remained fairly stable in the conditions once established until the most recent times. For 25 years alone it has been striking how quickly the Lithuanian nationality, their language, their customs and costumes are disappearing and how people are gradually becoming completely Germanized. It is not improbable that in 50 years' time there will be only small remnants of a purely Littauian people in these regions, especially with regard to the language. ”(August von Haxthausen 1839)

- “Although I suffer a lot of hardship and privation (for example, my current landlord's plates are completely alien - we eat from a common bowl) but I endure all of this with joy - soon it will be over, on October 15th I will remember in Prague. "( August Schleicher , 1853 in" Letters to the secretary, about the success of a scientific trip to Lithuania ")

- “The Littau resident generally likes to approach German and is particularly friendly and courteous towards him when he, who does not speak German, can converse with him or at least communicate with him in his language. He is a loyal fatherland friend and a brave soldier in the war. "(Friedrich Becker, 1866)

- “Scholars, who have to cover a wide range of languages, cannot be expected to learn Lithuanian as one learns the language of a people who are powerful in literature or science. It will always belong to those who learn very few people for their own sake, since literature offers nothing, even the often praised folk poetry with a few graceful songs does not compensate for the extremely poor content and the dreary monotony of the other thousands. "( August Leskien , 1891)

- "In the northernmost part of the province of East Prussia, the Lithuanian tribe, which is extremely strange in terms of language and customs, has lived for five millennia." ( Wilhelm Gaigalat , 1904)

- “The Lithuanians are not very drawn to each other, which is why it was difficult to get them as members. The membership has increased a bit every year and has now, after 5 years, reached 70, but this is very little if you compare it with the large number of Lithuanians living here. Why do we Lithuanians care so little about ourselves? We see that every people finds its greatest glory in preserving what it has possessed since ancient times: its language, its ancient customs. To familiarize oneself with the history of their people, with their national literature, is a matter of honor for Germans. Why is that not the same with us? Why don't we ensure that we can read and write well in our language? Why don't we read Lithuanian books as well as German ones? Why, when the Lithuanian meets the Lithuanian, is he ashamed or afraid to speak Lithuanian? An honorable, educated person does not throw away what he got from his mother and does not despise the inheritance of his fathers. "(Association of Lithuanians in Berlin, 1905)

- “... It is therefore worthwhile to look at the past. We do not think for a moment of Lithuania that has no past and no present in the present, of Prussian Lithuania with its slightly more than 100,000 Lithuanian-speaking Protestants who have no relations whatsoever with their Catholic tribal brothers across the border, to be completely alien and indifferent to them, to share nothing with them except the (dialectically) deviating language; Despite the decades of work “Junglithauens” that had to go on in Prussian soil, in Tilsit and elsewhere (severely hindered by the Prussian police, who eagerly obeyed all St. Petersburg instructions), these Lithuanians have remained without national consciousness: we are different from them Poland, d. H. the national element plays no role for us. So not about this venerable ethnographic curiosity, comparable to the elks of its forests, but we are talking about that Lithuania, which by adopting Catholicism before the flooding by the Russians and their orthodoxy, as well as by preserving its language before being absorbed by Polishism received ... "(Alexander Brückner, Polish historian, 1916)

- “Probably only a few out in the country know anything more precise about the Lithuanians and their songs, the Dainos. And yet these are among the most blooming and scented flowers in the wonder garden of folk poetry, and those are perhaps the most joyful and song-rich people on earth. The Lithuanian farmer sings while working in the fields, the girls in the spinning rooms, no social gathering, no wedding is celebrated without singing, in short the Lithuanian - at least where he has kept himself unmixed, like across the border - sings wherever there is an opportunity . "(Louis Nast, 1893)

- “With Lithuanian one immediately faced the question of which of the existing dialects should be used as a basis for the work. The Prussian-Lithuanian and the Russian-Lithuanian are so different that Russian and German Lithuanians can only communicate with difficulty. "(Seven-language dictionary: German, Polish, Russian, White-Ruthenian, Lithuanian, Latvian, Yiddish. 1918)

- “Since the Lithuanians were only able to assert themselves in East Prussia for more than two hundred years as a result of the plague, they also had no right to be granted on German soil. They would only have the status of "foreigners". In addition, Papritz denied the Mortensens the right to speak about "settlement issues in northeastern East Prussia" at the 1938 Amsterdam Geographers' Congress, despite the fact that they had already been announced. Foreign countries were denied the message that Slavic minorities had settled on "German soil" since the Middle Ages. Instead, the Mortensens now had to represent to the outside world that the German people had been "down to earth" far beyond the borders of their national state and had a right to be united in an all-German state. The new guideline of the Memel politics provided for the “foreign national” population groups either the expulsion or an assimilation. ”(Ingo Haar in: Historiker im Nationalsozialismus. German History and the“ Volkstumskampf ”in the East . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2000)

Secondary literature

General representations

- Zigmas Zinkevicius, Aleksijus Luchtanas, Gintautas Cesnys: Where we come from. The origin of the Lithuanian people. Vilnius 2005. Lithuanian Internet version : Tautos Kilme .

- Adalbert Bezzenberger : The career of the Lithuanian people . In: Quarterly for social u. Economic history . Volume XIII. Berlin 1916. pp. 1–40 ( online )

- Theodor Lepner: The Preusche Littauer. Danzig 1744 ( online ).

- Gottfried Ostermeyer: Thoughts from the old inhabitants of Prussia . Königsberg / Leipzig 1780 ( online ).

- Tiez: The Litthauer in East Prussia . In: Abroad. Twelfth year. Stuttgart and Tübingen 1839 ( online ).

- August Eduard Preuss: The Litthauer . In: ders .: Prussian country and folklore. Königsberg 1835. pp. 224-232 ( online ).

- August Gotthilf Krause: Litthauen and its inhabitants in terms of descent, folk kinship and language. A historical attempt with reference to Ruhig's contemplation of the Lithuanian language . Koenigsberg 1834.

- Ludwig von Baczko: Journey through a part of Prussia vol. 1. Hamburg and Altona 1800 ( online ).

- Rudolph Stadelmann: The Prussian kings in their activity for the national culture. First part. Friedrich Wilhelm I. Leipzig 1878 ( online ).

- Otto Glagau: Littau und die Littauer ( online ), Tilsit 1869.

- Albert Purpose : Lithuania. A country and folklore. Stuttgart 1898 ( online ).

- G. Hoffmann: Popular things from Prussian Lithuania . In: Communications of the Silesian Society for Folklore. Breslau 1899, No. 6, No. 1, pp. 1-10 ( online ).

- Franz Tetzner: The Slavs in Germany. Contributions to the folklore of the Prussians, Lithuanians and Latvians, the Masurians and Filipinos, the Czechs, Moravia and Sorbs, Polabians and Slovins, Kashubians and Poland Braunschweig 1902 ( online ).

- Wilhelm Storost: Lithuania in the past and present . Tilsit 1916 ( online ).

- Fritz Terveen: State and Retablissement. The reconstruction of northern East Prussia under Friedrich Wilhelm I, 1714–1740 . Goettingen 1954.

- Fritz Terveen: The retablissement of King Friedrich Wilhelm I in Prussian-Lithuania . In: ZfO Vol. 1, No. 4 (1952), pp. 500–515 ( online )

- Jochen D. Range: Prussian-Lithuania in a cultural-historical perspective. In: Hans Hecker / Silke Spieler: Germans, Slavs and Balts, aspects of living together in the east of the German Empire and in East Central Europe. Bonn 1989, pp. 55-81.

- Arthur Hermann (Ed.): The border as approximation, 750 years of German-Lithuanian relations. Cologne 1992.

- Algirdas Matulevicius: German-Lithuanian Relations in Prussian-Lithuania. In: Arthur Hermann (Ed.): The border as a place of rapprochement, 750 years of German-Lithuanian relations. Cologne 1992.

- Bernhart Jähnig u. a .: Church in the village. Their significance for the cultural development of rural society in “Prussia” 13. – 18. Century (exhibition catalog). Berlin 2002.

- Domas Kaunas: The cultural and historical heritage of Lithuania Minor. In: Annaberger Annalen. No. 12, 2004 ( online )

- Little Lithuania Foundation, Publishing Institute for Science and Encyclopedias: Little Lithuania Encyclopedia, Vilnius 2000–2008.

- Vol. 1: A-Kar, 2000.

- Vol. 2: Kas-Maz, 2003; Review: Klaus Fuchs: The Memel area in the presentation of the Little Lithuania Encyclopedia, in: Old Prussian Gender Studies , Vol. 38, Hamburg 2008, pp. 401–407.

- Vol. 3: Mec-Rag, 2006.

- Vol. 4: Rahn – Žvižežeris, 2008.

- Andreas Kossert : East Prussia, history and myth. 2005.

- Zigmas Zinkevicius: Mažosios Lietuvos indėlis į lietuvių kultūrą (The Influence of Lithuania Minor on Lithuanian Culture) . Vilnius 2008.

- Hermann Pölking: East Prussia. Biography of a Province . Berlin 2011 ( excerpt: “Those who speak Lithuanian and Curonian” online ).

- Hermann Pölking: The Memelland. Where Germany once ended . Berlin 2013.

- Werner Paravicini: The Prussian journeys of the European nobility . Part 1. Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1989, ISBN 3-7995-7317-8 ; Part 2. Thorbecke, Sigmaringen 1995, ISBN 3-7995-7348-8 ( Beihefte der Francia, 17, 1-2) ( Vol. 1 online ), ( Vol. 2 online ).

- History in the flow. The Memel, dossier of the Federal Agency for Civic Education , 2012.

- Ingė Lukšaitė , Vilija Gerulaitienė: Prūsijos įdomybės, arba Prūsijos regykla. T. 1 (MATTHAEUS PRAETORIUS: DELICIAE PRUSSICAE, or PRUSSIAN SCHAUBÜHNE) . Vilnius 1999. ( online ).

- Ingė Lukšaitė, Vilija Gerulaitienė, Mintautas Čiurinskas: Prūsijos įdomybės, arba Prūsijos regykla. T. 2 (MATTHAEUS PRAETORIUS: DELICIAE PRUSSICAE, or PRUSSIAN SCHAUBÜHNE) . Vilnius 2004. ( online ).

- MOKSLO IR ENCIKLOPEDIJU LEIDYBOS CENTRAS / Publishing Institute of Science and Encyclopedias: Concise Encyclopaedia of Lithuania Minor . Vilnius 2014.

- Robert Traba (ed.): Self-confidence and modernization. Social-cultural change in Prussian-Lithuania before and after the First World War . Osnabrück 2000 ( online ).

- Adalbert Bezzenberger: The Curonian Spit and its inhabitants . In: Research on German regional and folklore 3-4. Stuttgart 1889. pp. 166-300 ( online ).

- Ms. Lindner: The Prussian desert then and now. Pictures from the Curonian Spit . Osterwieck 1898. ( online ).

- Handbook of real estate in the German Empire. I. The Kingdom of Prussia, III. Delivery: The Province of East Prussia. Edited from official and authentic sources by P. Ellerholz, H. Lodemann. Berlin 1879. ( online ).

- Mokslo ir enciklopedijų Leidybos centras: Prussian-Lithuania. An encyclopedic manual . Vilnius 2017.

- Stephanie Zloch, Izabela Lewandowska: The “Pruzzenland” as a divided region of memory. Construction and representation of a European historical area in Germany, Poland, Lithuania and Russia since 1900 . Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, Göttingen 2014, ISBN 978-3-8471-0266-3 .

Settlement history

- Aleksander Pluskowski: The Archeology of the Prussian Crusade. Abingdon 2013

- Lotar Weber: Prussia 500 years ago in cultural-historical, statistical and military relation together with special geography. Danzig 1878 ( online )

- Reinhard Wenskus: The German order and the non-German population of Prussia with special consideration of the settlement . In: Walter Schlesinger (Ed.): The German East Settlement of the Middle Ages as a Problem of European History . Sigmaringen 1975. pp. 417-438 ( online ).

- P. v. Koeppen: The Lithuanian tribe. Spread and strength of the same in the middle of the XIX. Century . Academy of Sciences St. Petersburg. St. Petersburg / Leipzig 1850. Vol. 8, pp. 274-291 ( online ).

- Adalbert Bezzenberger: The Lithuanian-Prussian border. In: Old Prussian Monthly Journal, 1882, online.

- Alexander Kurschat: On the history of the Lithuanians in East Prussia . In: Communications from the Lithuanian Literary Society . Issue 18, Heidelberg 1893, pp. 497-509.

- Ernst Seraphim : Where does Prussian-Lithuania belong? Greve, Berlin around 1920.

- Gertrud Heinrich : Contributions to the nationality and settlement conditions of Pr. Lithuania . Berlin 1927 ( online ).

- Hans Mortensen: The Lithuanian Migration. In: Nachr. Gesellsch. d. Science Göttingen 1927 ( online ).

- Paul Karge: The Lithuanian question in Old Prussia in historical light. Königsberg 1925 ( online ).

- Otto Barkowski : The settlement of the main office Insterburg 1525-1603. Koenigsberg, 1928/1930.

- Hans Mortensen and Gertrud Mortensen : The settlement of northeastern East Prussia up to the beginning of the 17th century.

- Vol. 1: The Prussian-German settlement on the western edge of the Great Wilderness around 1400. Leipzig, 1937.

- Vol. 2: The wilderness in eastern Prussia, its condition around 1400 and its earlier settlement. Leipzig 1938.

- Vol. 3: Unfinished manuscript in the Secret State Archives in Berlin-Dahlem (shows the Lithuanian immigration based on the sources in the Königsberg archives); now in progress as: Jähnig, Bernhart and Vercamer, Grischa: Hans and Gertrud Mortensen: The settlement of northeastern East Prussia up to the beginning of the 17th century. The immigration of the Lithuanians to East Prussia.

- Manfred Hellmann: Volkstum in the German-Lithuanian border area. In: Ztsch. f. Folklore. 49/1940. Pp. 27-40 ( online ).

- Hans Mortensen, Gertrud Mortensen, Reinhard Wenskus, Helmut Jäger (eds.): Historical Atlas of the Prussian Country, Lf. 5: The settlement of the great wilderness. Wiesbaden 1978.

- Bernhart Jähnig: Germans and Balts in the historical-geographical work of Hans and Gertrud Mortensen in the interwar period. In: Michael Garleff (Ed.): Between Confrontation and Compromise , Lüneburg 1995, pp. 101-131 ( online ).

- Bernhart Jähnig : Lithuanian immigration to Prussia in the 16th century. A report on the “third volume” by Hans and Gertrud Mortensen. In: Udo Arnold (Ed.): On the settlement, population and church history of Prussia. Lueneburg, 1999.

- Arthur Hermann: The settlement of Prussian-Lithuania in the 15th-16th centuries Century in German and Lithuanian historiography. In: Journal for East Research. 39, 1990. pp. 321-341.

- Hans Heinz Diehlmann (ed.): The Turkish tax in the Duchy of Prussia 1540. Vol. 2: Memel, Tilsit. (Special publication 88/2), 331 pp. And 2 cards. Association for Family Research in East and West Prussia V., Hamburg 2007 (nationwide register of names of the tax-paying population).

- Hans Heinz Diehlmann (Ed.): The Turkish Tax in the Duchy of Prussia 1540, Vol. 3: Ragnit, Insterburg, Saalau, Georgenburg. (Special publication 88/3), Association for Family Research in East and West Prussia e. V., 88/3, Hamburg 2008.

- Grischa Vercamer: 2008_Introduction, in: The Turkish Tax in the Duchy of Prussia 1540, Vol. 3: Ragnit, Insterburg, Saalau, Georgenburg (special publications of the Association for Family Research in East and West Prussia, 88/3), ed. von Diehlmann, Hans Heinz, Hamburg 2008, pp. 7 * -31 * ( online ).

- Grzegorz Bialunski: Population and settlement in the orderly and ducal Prussia in the area of the Great Wilderness until 1568 (special publication 109), Association for Family Research in East and West Prussia e. V., Hamburg 2009.

- Grischa Vercamer: Settlement, social and administrative history of the Komturei Königsberg in Prussia (13th - 16th centuries) (= individual publications of the Historical Commission for East and West Prussian State Research, Vol. 29), Marburg 2010. Digital maps in pdf and pmf format ( online ( memento of February 2, 2014 in the Internet Archive ))

- Max Beheim-Schwarzbach: Friedrich Wilhelm's I colonization plant in Lithuania, mainly the Salzburg colony. Königsberg 1879 ( online ).

- Lothar Berwein: Settlement of Swiss colonists as part of the repetition of East Prussia (special publication 103), Association for Family Research in East and West Prussia e. V., Hamburg 2003.

- Johann Friedrich Goldbeck: Complete topography of the Littthau Cammer department . Marienwerder 1785. ( Online, Google )

- Wolfgang Rothe: On the history of the settlement in Prussian Litthauen . 2016.

- Volume I: Text volume

- Volume II: Document volume

- Distribution map of the East Prussian ethnic groups

- Vincas Vileišis: Tautiniai santykiai Mažojoje Lietuvoje ligi Didžiojo karo: istorijos ir statistikos šviesoje [Nationality relations in Lithuania Minor up to the World War from the point of view of history and statistics]. 2nd Edition. Vilnius 2009.

- Christoph Lindenmeyer: rebels, victims, settlers. The expulsion of the Salzburg Protestants. Salzburg 2015.

- Kurt Forstreuter: The beginnings of language statistics in Prussia and their results on the Lithuanian question. In: ZfO 2, 1953, pp. 329-35 ( online ).

- Christian Ferdinand Schulze : The emigration of the evangelically minded Salzburgers with reference to the emigration of the evangelically minded Zillerthalers . Gotha 1838. ( Online, Google )

- Domas Kaunas (ed.): Pirmieji Mažosios Lietuvos lietuviai Kanadoje (The first Prussian Lithuanians in Canada) . Išeivio Jurgio Kavolio 1891–1940 metų dokumentinis paveldas (Documentary estate of the emigrant Georg Kawohl from the years 1891–1940). Vilnius 2015.

- Johannes Kuck: The settlements in western Nadrauen . Leipzig 1909. ( online ).

- George Turner : Salzburg, East Prussia - Integration and Preservation of Identity. Berlin 2017.

- Wilhelm Sahm: History of the plague in East Prussia. Leipzig 1905. ( online ).

- Ulrich Wannagat: Family tree of a farming family from the old Prussian landscape of Schalauen: Wannagat in Klein Schillehlen. Self-published in 2000.

Individual presentations on the history of the settlement

- Wolfgang Rothe: Parish Tollmingkehmen, a contribution to the history of settlement in Prussian Lithuania. Volume III, ISBN 3-9807759-2-5 , published by Prusia, Duisburg 2005.

- Günter Uschtrin (Ed.): Where is Coadjuthen? The story of an East Prussian parish in the former Memelland . Berlin 2011.

- Erwin Spehr: From the history of the Schloßberg district (Pillkallen) . Gene wiki. Portal: Pillkallen / History ( online ).

- Horst Kenkel: Grund- und Häuserbuch der Stadt Tilsit: 1552-1944 . Cologne / Berlin 1973 ( online ).

- Gitanas Nausėda / Vilija Gerulaitienė (ed.): Chronicle of the school in Nida. Vilnius 2013

- Wulf D. Wagner : Das Rittergut Truntlack 1446–1945: 499 years of history of an East Prussian estate . Husum 2014

- Gustav Tobler: Swiss colonists in East Prussia . In: Anzeiger für Schweizerische Geschichte. Vol. 7 (new episode). Pp. 409-414 (1896 No. 6). ( online ).

- A. Strukat: Swiss colonies in East Prussia . In: Journal of Swiss History. Volume XI, Issue 3 (1931). Pp. 371-377 ( online ).

- Alfred Katschinski: The fate of the Memelland . Tilsit 1923. ( online ).

- Hans Mortensen: Immigration and internal expansion at the beginning of the settlement of the main office in Ragnit. In: Acta Prussica (1969). Pp. 67-76

- Theodor Krüger: The Salzburg immigration in Prussia, with an appendix of memorable files and the history of the Salzburg hospital in Gumbinnen, together with the statute of the same. Gumbinnen 1857. ( online ).

- EC Thiel: Statistical-topographical description of the city of Tilse . Königsberg 1804. ( online ).

- Ernst Thomaschky: Northern East Prussia and Memelland. Water guide. Self-published in 1933. Reprint by Verlag Gerhard Rautenberg, Leer 1989.

- Siegfried Maire: Relations between the Swiss who immigrated to Prussian-Lithuania and their old homeland. In: Leaves for Bernese history, art and antiquity. Vol. 8/1912. ( online ).

Social history

- A. Horn and P. Horn (eds.): Friedrich Tribukeit's Chronik. Description from the life of the Prussian-Lithuanian rural residents of the 18th and 19th centuries . Insterburg 1894. Reprint in: Old Prussian Gender Studies (New Series). Vol. 16, 1986, pp. 433-468.

- Alina Kuzborska: The image of Prussian-Lithuania in the 18th century in the work of K. Donelaitis . Internet edition Collasius, 2003. ( online ).

- Wilhelm von Brünneck: On the history of real estate in East and West Prussia. Berlin 1891 ( online ).

- Karl Böhme: Landlord and rural conditions in East Prussia during the reform period from 1770 to 1830. Leipzig 1902.

- Felix Gerhardt: The farm workers in the province of East Prussia. Lucka 1902 ( online ).

- Family history and local history contributions from "Nadrauen" . Local supplement of the Ostpreußischer Tageblatt published in Insterburg 1935 to 1940. Special publication of the Association for Family Research in East and West Prussia, No. 117. Reprint Hamburg 2013.

- Kurt Staszewski and Robert Stein: What were our ancestors? Official, professional and class names from Old Prussia. Königsberg 1938. ( online ).

- Martina Elisabeth Mettner: The change in the social relationships between landlords, institutes, farmers and sub-peasant classes in Samland after the “peasant liberation” . Osnabrück 2013. ( online ).

- Manfred Klein: "... the youngsters were already over the mountains". On the subculture of young people in the Lithuanian village . In: Annaberger Annalen No. 3/1995. Pp. 138-159. ( online ).

- Dietrich Flade: Administrative measures and their effects in the 18th century on the life of the "subjects in Prussian Litthauen" . In: Annaberger Annalen No. 22/2014. Pp. 153-206. ( online ).

- Hedwig v. Lölhöffel: Country life in East Prussia. o. O. 1976 ( online ).

- August Skalweit: The East Prussian domain administration under Friedrich Wilhelm I and the retablissment of Lithuania. Leipzig 1906.

- Algirdas Matulevičius: Mažoji Lietuva XVIII amžiuje: lietuvių tautinė padėtis . Vilnius 1989. (German abstract online ).

- Georg Didszun: East Prussian Ahnenerbe. How the East Prussian farmer once lived. Leer 1956.

- Gustav Aubin: On the history of the landlord-peasant relationship in East Prussia from the establishment of the religious order to the Stein reform . Leipzig 1910. ( online ).

Administrative history

- August Skalweit: The East Prussian domain administration under Friedrich Wilhelm I and the Retablissement of Lithuania. Leipzig 1906. ( online ).

- Rasa Seibutyte: The formation of the province of Lithuania in the 18th century in: Lithuanian Cultural Institute Annual Conference 2007, Lampertheim 2007. pp. 23–46 ( online ).

- Rolf Engels: The Prussian administration of the Gumbinnen Chamber and Government (1724-1870). Cologne / Berlin 1974.

- Dieter Stüttgen: The Prussian administration of the administrative district Gumbinnen 1871-1920 . Cologne 1980.

- Gumbinnen district . In: Territorial changes in Germany and German administered areas 1874–1945 ( online ).

- Kurt Dieckert: Government capital Gumbinnen and its administrative district . ( online ).

Institutions

- Primary school system in the government district of Gumbinnen, mainly in relation to the increased number of school-age children and the proportion of the inhabitants of the German, Lithuanian and Polish tongues . Yearbooks of the Prussian Volks-Schul-Essence - 3.1826. ( online ).

- Adolf Keil: The elementary schools in Prussia and Litt sculpting under Frederick William I. . In: Old Prussian Monthly Bulletin 23 (1886), pp. 98-137 185-244. ( PDF ).

- Arthur Hermann: Lithuanian-language teaching in East Prussia and its representation in German and Lithuanian historiography , Northeast Archive Volume I: 1992, no. 2, pp. 375–393 ( online; PDF; 1.1 MB).

- Christiane Schiller: The Lithuanian seminars in Königsberg and Halle. A balance sheet , Nordost-Archiv Volume III: 1994, no . 2, p. 375 ( online ).

- Danuta Bogdan: The Polish and the Lithuanian seminar at the Königsberg University from the 18th to the middle of the 19th century , Northeast Archive Volume III: 1994, no. 2, p. 393 ( online ).

- Albertas Juška: Mažosios Lietuvos mokykla (The School of Lithuania Minor). Klaipėda 2003.

- Johannes Brehm: Development of the Protestant elementary school in Masuria as part of the overall development of the Prussian elementary school from the Reformation to the reign of Friedrich Wilhelm I. Königsberg in 1913 ( online )

- Marianne Krüger-Potratz / Dirk Jasper / Ferdinand Knabe: “Fremdsprachige Volksteile” and German Schools: School Policy for the Children of the Autochthonous Minorities in the Weimar Republic - a source and work book. 1988.

- Leszek Belzyt: Linguistic minorities in the Prussian state 1815-1914. The Prussian language statistics in progress and commentary. Marburg 1998. ( online )

Material culture

- Adalbert Bezzenberger: About the Lithuanian house . In: Old Prussian Monthly Bulletin 23 (1886), pp. 34–79 ( PDF ).

- Richard Jepsen Dethlefsen : Farmhouses and wooden churches in East Prussia. Berlin 1911 ( online ).

- Adolf Boetticher: The architectural and art monuments of the province of East Prussia, booklet V. Lithuania. Königsberg 1895 ( online ).

- Georg Froelich: Contributions to the folklore of Prussian Lithuania. Insterburg 1902 ( online ).

- Martynas Purvinas: Mažosios Lietuvos tradicinė kaimo architektūra (“Traditional village architecture in Lithuania Minor ”). Vilnius 2008 ( PDF ).

- Christian Papendick: The north of East Prussia: land between decline and hope. A pictorial documentation 1992–2007. Husum 2009.

- Albert Kretschmer: Historical national costumes in Lithuania around 1870 . In: Folk costumes . Leipzig 1887. ( online ).

economy

- Friedrich Mager: The forest in Old Prussia as an economic area . Cologne 1960.

- Hans Bloech: East Prussia Agriculture . o. O. 1988. Part 1 ( PDF ). Part 2 ( PDF ). Part 3 ( PDF )

- Gerhard Willoweit: The economic history of the Memel area . Marburg 1969. Vol. 1 ( online ). Vol. 2 ( online )

- Julius Žukas: Economic development of the Memel region from the second half of the 19th century to the first half of the 20th century (1871–1939) . Diss., University of Klaipėda 2010 ( online )

- Cultural Center East Prussia in Ellingen (ed.): Trakehnen a horse paradise. The history of the main Trakehnen stud and horse breeding in East Prussia. Ellingen 2008. ( online )

- Rothe, Keding, Mildenberger, Salewski: On the smallholder structure in Prussian Lithuania (Reg.-Bez. Gumbinnen) Shown using the example of Buttgereit-Serguhnen and Lessing-Ballupönen (Wittigshöfen near Tollmingkehmen). 2017

- Klaus J. Bade: Land or Work? Transnational and internal migration in the north-east of Germany before the First World War. Erlangen-Nuremberg 1979. ( online )

identity

- Brolis: wake-up call to Prussia's educated Lithuanians . Tilsit 1911 ( online ).

- Max Niedermann: Russian and Prussian Lithuanians. 1918 ( online ).

- Wilhelm Storost-Vydunas : Seven Hundred Years of German-Lithuanian Relations. Tilsit 1932 ( The people of our homeland ).

- Walther Hubatsch : Masuria and Prussian-Litthauen in Prussia's nationality policy 1870–1920. Marburg 1966.

- Joachim Tauber: The Unknown Third: The Little Lithuanians in the Memel area 1918-1939. In: Bömelburg / Eschment (ed.): The stranger in the village. Lüneburg 1998, pp. 85-104.

- Georg Gerullis (Rector of the University of Königsberg): On the Prussian-Lithuanian identity. ( online ).