Legal position in Germany after 1945

As the legal position of Germany after 1945 , the legal position of the German Reich after the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht on 7/8 May 1945. Specifically, the question arose as to whether the occupied German nation-state , whose supreme power of government the Allies had taken over with the Berlin Declaration on June 5, 1945, continued to exist as a legal entity from a constitutional and international law perspective or had perished . Since the people and territory of the state still existed in 1945, in line with the three-element doctrine , the main argument was whether state authority had ceased to exist. The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany was based on the continued existence of the German Reich. The Federal Constitutional Court confirmed this in 1973 and determined that there were two states on German soil that were not foreign to one another, the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic . Internationally the question remained controversial until German reunification in 1990; In the Eastern Bloc , after the establishment of the two German states, it was assumed that the entire German state had also perished from a legal point of view and that two successor states had now taken its place.

Legal conceptions of the victorious powers

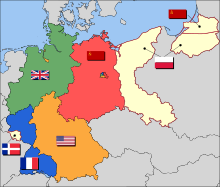

As a result of the Casablanca Conference , US President Franklin D. Roosevelt formulated the demand for unconditional surrender on January 24, 1943 . Roosevelt wanted to make it clear that Nazi Germany could not be a contractual partner of the Allies. Rather, the National Socialist state authority should be completely eliminated in order to have a free hand in the redesign. Based on the plans of the American Foreign Minister Cordell Hull , the European Advisory Commission (EAC), which was set up at the beginning of 1944, recommended that Germany should unconditionally surrender not only militarily but also politically and politically, and that the German Reich government should therefore also sign the document of surrender. It was intended that this would create new international law. The document of surrender passed on July 25, 1944 and the commentary report of the EAC made it clear that the victorious powers wanted to regulate the legal position of Germany unilaterally after the surrender. However, the American commander-in-chief Dwight D. Eisenhower and the Soviet high command mutually disregarded this conception and agreed on May 4, 1945, an exclusively military surrender. The American representative of the EAC, Ambassador John Gilbert Winant , only managed to get a change in Article 4, which stipulated that the Allies could replace the specifically military document of surrender with another form of surrender. With the Berlin Declaration of June 5, 1945, the Allies implemented this reservation and took over the power of government (“supreme authority”) in Germany. According to the London Protocol , Germany was divided into zones of occupation in which the respective commanders-in-chief exercised authority on behalf of their governments. The Allied Control Council was established for common matters .

“The German armed forces on land, sea and in the air are completely defeated and have unconditionally surrendered, and Germany, which is responsible for the war, is no longer able to oppose the will of the victorious powers. As a result, Germany's unconditional surrender has taken place, and Germany submits to all demands that are now or later placed on it.

There is no central government or agency in Germany which is capable of taking responsibility for maintaining order, for administering the country and for carrying out the demands of the victorious powers. [...] The governments of the United Kingdom, the United States of America, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the Provisional Government of the French Republic hereby assume supreme governmental power in Germany, including all powers of the German government, the Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht and the Governments, administrations or authorities of the states, cities and municipalities. The assumption of said governmental authority and powers for the aforementioned purposes does not result in the annexation of Germany. "

Historians have interpreted the assumption of government power (“supreme authority”) in Germany by the victorious powers in such a way that the German state as such perished. This theory was also the starting point for the legal considerations at the end of the war. In 1944, the exiled international lawyer Hans Kelsen proposed that the victorious powers should occupy Germany and replace its sovereignty with the joint sovereignty of a condominium in order to carry out the planned reorganization. At this point in time the plan was to divide Germany into several states. After the Berlin Declaration, Kelsen stated that Germany had ceased to exist as a state within the meaning of international law. An occupatio bellica could not be accepted. An occupatio bellica would have meant that the victorious powers would have been bound by the general principles of customary international law and were restricted in the exercise of their occupation rule by the Hague Land Warfare Regulations and the Geneva Conventions . However, the declared goals of the Allies to reorganize Germany and to transform it went far beyond that. Kelsen's solution consisted in the construction of an originally acquired sovereignty for the victors, which suited the Allied plans for Germany. For the definitive replacement of state authority, however, traditional international law provided for an act of subjugation ( subjugatio , debellatio ), as would have been presented by annexation . The victorious powers had explicitly rejected this. So Kelsen's teaching seemed to prevail at first, but this point of view could not be maintained. Only the French decided from the start that Germany had perished as a state, although in practice they occasionally ignored it. The USA, Great Britain and the Soviet Union, on the other hand, apparently deliberately avoided committing themselves in order to retain political room for maneuver.

The question of the collapse of German statehood also affects the legitimacy of the decisions of the Potsdam Conference under international law . A German Reich that was simply incapable of acting would not be bound by international law to the decisions of the "Big Three" on the German eastern territories beyond the Oder and Neisse , which were placed under provisional administration by Poland and the Soviet Union. Compared to a German state that no longer exists, the winners would have effectively controlled German territory and the peace treaty reservation would only have been of a political nature.

The German discussion until mid-1948

For the Germans, the problem of the continued existence of German statehood arose at the end of the war. In the first phase of the discussion, from 1945 to 1948, the continuation thesis prevailed.

On May 22, 1945 , Wilhelm Stuckart had submitted an expert opinion for the Dönitz government that Germany continued to exist as a state under international law. With the arrest of the Dönitz government the following day, the report remained unknown. Other problems arose at the level of public administration. When setting up new administrative structures , the legislative powers, the previous employment relationships of the employees and civil servants as well as the private law obligations of the former authorities had to be clarified. In addition, expert opinions were issued which, with one exception, came to the conclusion with arguments based on constitutional law that the Reich had not perished as a state. Kelsen's argumentation was largely unknown in Germany at the time. In October / November 1946 Wilhelm Cornides presented his essays to the German academic public in the Europa-Archiv .

At this point, politicians had already taken the initiative. Konrad Adenauer, for example, applied in May / June 1946 to the Zone Advisory Board of the British Zone to have Germany's international legal situation clarified by an expert. He hoped that the continuity of Germany would be confirmed in order to then be able to urge the Allies to comply with the Hague Land Warfare Regulations. However, the military government did not respond and forbade further discussion. At the end of 1946, the Hessian Prime Minister Karl Geiler spoke out decisively against Kelsen's theses.

The Hamburg international law expert Rudolf Laun published an article in the weekly newspaper Die Zeit on December 19, 1946 , in which he established the continued existence of the German Reich as a legal subject and demanded compliance with the Hague Land Warfare Regulations. This was followed by a journalistic debate, whereupon Laun repeated his theses at the first post-war conference of German international law experts in April 1947 and linked them to demands for the occupation powers to deal with the Germans. The SPD politician Georg August Zinn simultaneously published corresponding statements in the Neue Juristische Wochenschrift and the Süddeutsche Juristenteitung .

Despite differences of opinion in detail, German constitutional and international law formed almost unanimously in favor of the theory of continuity, while the advocates of a doom thesis such as Hans Nawiasky , Wolfgang Abendroth or Walter Lewald were marginalized. The legal discussion was based on the concept that the law should be used for politics. As outlaws of the international community, it was hoped that insisting on traditional international law would create political leeway and use it for one's own interests. It therefore rejected any changes to the criteria of international law based on the new situation after war, surrender and occupation of Germany. In the years 1947 and 1948 this was of increasing political importance in questions of occupation policy, dismantling , reparations , requisitions, occupation costs or citizenship law . This led to a discussion about the new regulation of the occupation law in the form of an occupation statute .

The Republic of Austria , which after the so-called Anschluss became part of the “Greater German Reich” and was absorbed into it (the Moscow Declaration of the Allies of November 1, 1943 declared the “Anschluss” to be “null and void”, the Austrian Declaration of Independence from November 27 , 1943) April 1945 assumed a “completed annexation” of Austria and accordingly proclaimed its nullity ), had separated from the German Reich in 1945 by way of a secession under international law and was reestablished as a new state within the 1938 borders. In contrast, positive law identifies Austria with the former Austrian state and postulates its continuity (occupation theory). Like Germany, this was divided into four zones; Just as in Germany, the Allies' claim to joint responsibility for occupied post-war Austria was thus upheld. The Austrian nationality did not rest about 1938-1945, but went under, so that in 1945 a new nationality with effect ex nunc has emerged.

Foundation of the Federal Republic and the GDR

After the London Conference of November and December 1947 was unsuccessful, the Western Allies decided to establish a West German state. The Americans, with their desire for a strong federal state, prevailed against the French , who actually only wanted to tolerate a weak confederation on their border. That the Parliamentary Council worked out by the West German state parliaments adopted and by the occupying powers approved Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany on 23 May 1949 in the Federal Law Gazette published and entered into force the following day. The Federal Republic only became capable of acting through its organs when the first German Bundestag was constituted on September 7th and the Federal Government took office on September 20th.

On October 7, 1949, the provisional People's Chamber put the constitution of the German Democratic Republic into effect in the Soviet occupation zone . The GDR government took office on October 12th.

As early as April 10, 1949, the Occupation Statute was issued to delimit the powers and responsibilities between the future German government and the Allied Control Authority, which reserved the Western Allies certain sovereign rights with regard to the Federal Republic , such as the exercise of foreign relations of the Federal Republic or the Control of their foreign trade, every constitutional amendment was subject to approval, laws could be overturned, and the military governors reserved full power in the event that security was threatened.

These reservation rights were exercised by the Allied High Commission , which was then founded on June 20 , which thus continued to hold the highest state authority. The occupation law took precedence over the Basic Law, could not be measured by its standard and could only be repealed by international treaties between the Federal Republic and the occupying powers. The Federal Republic thus initially had only limited sovereignty .

With the Paris Treaty of October 23, 1954, which came into force in 1955 , the occupation regime of the Western Allies in the Federal Republic was ended. The Paris Treaties also included the Germany Treaty of May 26, 1952 in the version of October 23, 1954, of which Article 1, Paragraph 2 stated:

"The Federal Republic will [...] have the full power of a sovereign state over its internal and external affairs."

However, at the same time, Art. 2 contained reservations regarding Berlin and Germany as a whole:

“In view of the international situation which has hitherto prevented the reunification of Germany and the conclusion of a peace treaty, the Three Powers retain the rights and responsibilities they have previously exercised or held with regard to Berlin and Germany as a whole, including the reunification of Germany and one peace treaty regulation. "

The Federal Republic did not have full sovereignty again when it came into force.

Due to developments in the Federal Republic of Germany, the Soviet Union issued a unilateral declaration on March 25, 1954 about the "establishment of full sovereignty of the German Democratic Republic":

"1. The USSR establishes the same relations with the German Democratic Republic as it does with other sovereign states. "

"The German Democratic Republic will have the freedom to decide at its own discretion about its internal and external affairs, including the question of relations with West Germany."

"2. The USSR retains the functions in the German Democratic Republic which are connected with the guarantee of security and which result from the obligations which the USSR accrues from the Four Power Agreement. "

Thereupon the GDR declared its sovereignty two days later. Both German states made use of their extensive sovereignty when they joined the United Nations in 1973 .

In contrast, Berlin remained the responsibility of the four occupying powers. It is true that the GDR declared “Berlin” to be its capital with Art. 2 Clause 2 of its constitution of October 7, 1949, while the Federal Republic of Germany considered “ Greater Berlin ” to belong to it, which was stated in the old version of Art. 23 of the Basic Law of May 23, 1949 was expressed:

“This Basic Law initially applies in the areas of the states of Baden, Bavaria, Bremen, Greater Berlin, Hamburg, Hesse, Lower Saxony, North Rhine-Westphalia, Rhineland-Palatinate, Schleswig-Holstein, Württemberg-Baden and Württemberg-Hohenzollern. In other parts of Germany it is to be put into effect after their accession. "

However, the (Western) Allies had never recognized either West or East Berlin as part of the Federal Republic or the GDR, but rather Berlin (or at least West Berlin) as a still occupied territory in accordance with the four-power status that continued to apply to Berlin treated. This is also expressed in the four-power agreement on Berlin of 1971, according to which the four-power status for Berlin continued to apply.

This state of affairs in the Federal Republic, Berlin and the GDR persisted and did not change again until reunification in 1990.

The legal situation of the German Empire

While the characteristics of “state people” and “national territory” of the German Reich were undisputed (see also below ) , the question of the legal situation depended exclusively on its characteristic “state authority”. Various doom and continuity theories existed for this. The existence and legal status of the Federal Republic of Germany and the GDR were interpreted differently on the basis of these theories.

Doom theories

Doom theories (discontinuity theories) assume that the state, which was known as the German Reich until 1945, went under as a subject of international law . Since the fall of the German Reich , its constitutional law could no longer be effective. Within this theory there are again controversial conceptions as to when the state went under. The states of the Eastern Bloc and others postulated the international law deballation of the German Reich, justified by the military defeat in 1945. Other conceptions saw the point in time when the German state was founded in 1949 as decisive. According to this, the German Reich existed until 1949 and then went under with a dismembration , in international law the division of a general state into independent individual states. The Federal Republic of Germany and the GDR would therefore be successor states to the German Empire.

Debellation theory

At the beginning of the scholarly international law discussion, Hans Kelsen had already argued in 1944 that in the event of an occupatio bellica of Germany by the Allies, in which state authority would only have been temporarily ousted, they would have a certain degree of administrative powers under the Hague Land Warfare Regulations. The Allies would go beyond this measure with their measures such as denazification , re-education and demilitarization . It should therefore be assumed that the Allies would have a condominium , and Germany ceased to exist as a sovereign state.

The problem with this theory is that, under international law, an act of submission ( debellatio ) would have to have taken place in order to replace state authority . In the case of an annexation, this would have been answered in the affirmative without problems, but in the present case, as mentioned above, there was no annexation. So it was questionable whether the state authority had been replaced.

Dismembration theory

The dismembration theory assumed that the German Reich had split up into the two German states of the Federal Republic and GDR, neither of which was identical to the German Reich, and that the German Reich had therefore ceased to exist.

Within the dismembration theory, the point in time at which the disintegration should have taken place differed: in part this was linked to the founding of the two German states in 1949, according to another view the disintegration took place with the recognition of the sovereignty of the two states by the respective occupying powers in 1954 and Another opinion was of the opinion that the collapse occurred with the entry into force of the Basic Treaty in 1973.

Continuity theories

According to the survival theories, the German Reich continues. Up until the Yalta Conference in the first few months of 1945, the Allies took it for granted that Germany had to be dismembered. Until the Potsdam Conference , which lasted from July 17 to August 2, 1945, the tendency to treat the area of Germany to be occupied by the Allies as an economic and also as a political unit prevailed. This gave the survival theories more weight.

What the continuity theories have in common is that they do not assume any kind of downfall of the German Reich, but rather its military occupation (occupatio bellica) . The Allies' takeover of state power merely made the German Reich incapable of acting. During its existence from 1945 to 1948, the Allied Control Council therefore assumed a dual position; on the one hand it exercised state authority of the German Reich on a fiduciary basis, on the other hand it was a joint international law organ of the four occupying powers and also exercised their state authority in Germany .

Roof theory / partial order theory

The roof or partial order theory assumed that under a fictitious roof of the German Reich (within the German external borders of December 31, 1937 ) the two would not exist with this identical partial order of the Federal Republic of Germany and the GDR. One of these partial state orders (due to the lack of democratic legitimation of the GDR, according to widespread opinion in the West only the Federal Republic of Germany was considered) acts as a representative of the entire state of the German Reich, which no longer has any special organs, and takes on its tasks and rights in a trustee manner.

State core theory

The state core theory assumed that the Federal Republic was identical to the German Reich, but differentiated between the state territory, which was that of the German Reich within the borders of December 31, 1937, and the scope of the Basic Law, which would correspond to the territory of the Federal Republic.

The variant of the state core theory that the GDR is identical with the German Reich is less widespread. This assumption was abandoned by the GDR itself in the 1950s (see below) , but is interesting precisely because this variant would in fact mean that the German Reich would have "acceded" to the Federal Republic of Germany in 1990.

Core State Theory / Shrinking State Theory

The core state or shrinking state theory also assumed the identity of the Federal Republic with the German Reich, but assumed that the territory of the German Reich had shrunk to the territory of the Federal Republic.

This was the prevailing theory in the West at the time the Federal Republic was founded. In his inaugural speech, the President of the GDR, Wilhelm Pieck , seems to refer to this theory and claim it for the newly founded GDR:

“The division of Germany , the perpetuation of the military occupation of West Germany by the occupation statute , the separation of the Ruhr area from the German economic body will never be recognized by the German Democratic Republic, and we will not rest until those who have been illegally torn away from Germany and subjected to the occupation statute Parts of Germany with the German core area, with the German Democratic Republic are united in a unified democratic Germany. "

Identity theories

Identity theories assume the legal identity of one of the newly created states with the German Reich. The Federal Republic of Germany represented just being identical with the German Reich until around 1969 ( state core theory ). The partial identity theory finally proceeded from the identity of both German states with the German Reich, each related to their area. The consequence of this partial identity was that the Federal Republic of Germany could not establish any new obligations or rights for the whole of Germany during the division of Germany and, in particular, could not conclude a peace treaty .

View of the GDR

The GDR initially assumed that the German Reich would continue to exist and initially took the view that it was identical to it, from which it derived a claim to sole representation for all of Germany. Later she assumed a partial identity with him.

In the mid-1950s she advocated the theory of debellation and dated the fall of the German Reich on May 8, 1945, the day of the unconditional surrender of the German Wehrmacht. With the founding of the Federal Republic and the GDR in 1949, two new states emerged.

View of the Federal Republic

From the outset, the Federal Republic assumed that the German Reich would continue to exist and initially took the view that it would be identical with it both as a legal entity and in terms of constitutional law. From this she also derived a claim to sole representation for the whole of Germany, which she also tried to enforce by means of the Hallstein Doctrine .

The Federal Constitutional Court had also assumed the continued existence of the German Reich in numerous decisions:

“In scientific discussions, the fact that only the armed forces and not the government surrendered unconditionally has only been taken as evidence of the continuity of a unified Germany. The Allies then exercised state power in Germany by virtue of their own right of occupation , not by virtue of being transferred by a German government; the state power of the later newly formed German government organs is not based on a retransfer by the Allies, but represents original German state power that has become free again with the resignation of the occupation power. "

“This interpretation of Article 11 of the Basic Law arises not only from the fundamental conception of the nationwide German nation anchored in the Basic Law, but no less from the likewise fundamental conception of the nationwide state territory, and in particular from the all-German state authority: the Federal Republic of Germany as the appointed and alone Part of Germany as a whole that was able to act and which could be reorganized by the state, granted the Germans of the Soviet occupation zone freedom of movement, also because of this fundamental conception of their position. It has thus at the same time justified the claim to the restoration of comprehensive German state power and legitimized itself as the state organization of the state as a whole, which until now could only be reestablished in freedom. "

In 1954, a judgment on a constitutional complaint by former members of the Wehrmacht cited the judgments of 1952 and 1953.

In 1957 the legal issue arose from pre-war treaties with the Holy See regarding religious instruction in schools. The statements were as follows:

"The assumption of such a remainder of mutual legal relationships presupposes that the German Reich continued to exist as a partner of such a legal relationship beyond May 8, 1945, a legal opinion from which the Federal Constitutional Court [...] started."

“Of course, the legal structure of the state partner has changed fundamentally. The tyranny collapsed. However, according to the prevailing opinion, which was also shared by the court, this did not change anything in the continued existence of the German Reich and therefore also nothing in the continued existence of the international treaties concluded by it [...] "

“The German Reich, which did not cease to exist after the collapse, continued to exist after 1945, even if the organization created by the Basic Law is temporarily limited in its validity to part of the Reich territory, the Federal Republic of Germany is identical to that German Reich."

The attitude of the Federal Republic with regard to its constitutional and international legal identity or its claim to sole representation changed only in the 1960s within the framework of the new Ostpolitik , in which the Hallstein doctrine was given up in favor of “change through rapprochement”. Aspects of various theories of survival were combined. It was concluded that the two German states could not be foreign to one another . The Basic Treaty also emerged from the new Ostpolitik .

In its 1973 ruling on the basic treaty, which it had to decide on after an application by the Bavarian State Government for an abstract review of norms , the Federal Constitutional Court also found, combining various continuation theories:

“The Basic Law - not just a thesis of international law and constitutional law! - assumes that the German Reich survived the collapse of 1945 and did not go under either with the surrender or through the exercise of foreign state authority in Germany by the allied occupying powers; this follows from the preamble, from Art. 16 , Art. 23 , Art. 116 and Art. 146 GG. This also corresponds to the constant jurisprudence of the Federal Constitutional Court, to which the Senate adheres. The German Reich continues to exist [...], still has legal capacity, but is unable to act as a state as a whole due to a lack of organization, in particular due to a lack of institutionalized bodies. "

“With the establishment of the Federal Republic of Germany, a new West German state was not founded, but part of Germany was reorganized (cf. Carlo Schmid in the 6th session of the Parliamentary Council - StenBer. P. 70). The Federal Republic of Germany is therefore not the “legal successor” of the German Reich, but as a state is identical to the state “German Reich” - with regard to its spatial extent, however, “partially identical”, so that in this respect the identity does not claim exclusivity. As far as its nation and territory are concerned, the Federal Republic therefore does not include the whole of Germany, regardless of the fact that it is a unified nation of the subject of international law 'Germany' (German Reich), to which its own population belongs as an inseparable part, and a unified national territory 'Germany' (German Empire), to which their own national territory also belongs as a non-separable part. In terms of constitutional law, it limits its sovereignty to the “scope of the Basic Law” […], but also feels responsible for the whole of Germany (cf. preamble to the Basic Law). The Federal Republic currently consists of the states named in Art. 23 GG, including Berlin; the status of the state of Berlin in the Federal Republic of Germany is only diminished and burdened by the so-called reservation of the governors of the western powers [...]. The German Democratic Republic belongs to Germany and cannot be viewed as a foreign country in relation to the Federal Republic of Germany "

In the Teso decision of 1987, the Federal Constitutional Court stated:

“The Parliamentary Council did not understand the Basic Law as an act of establishing a new state; he wanted to 'give state life a new order for a transitional period' until the 'unity and freedom of Germany' in free self-determination was completed (preamble to the Basic Law). Preamble and Article 146 of the Basic Law summarize the entire Basic Law with this aim in mind: the constitution-giver has thereby standardized Germany's will to state unity, which threatened serious danger because of the global political tensions that had broken out between the occupying powers. He wanted to counteract a state division in Germany, as far as this was in his power. It was the basic political decision of the Parliamentary Council not to establish a new ('West German') state, but to understand the Basic Law as a reorganization of part of the German state - its state authority, its state territory, its state people. The Basic Law is based on this understanding of the political and historical identity of the Federal Republic of Germany. The adherence to German citizenship in Article 116, Paragraph 1, Article 16, Paragraph 1 of the Basic Law and thus the previous identity of the state people of the German state is a normative expression of this understanding and this basic decision. "

"Already Article 116, Paragraph 1, Clause 2 of the Basic Law shows that the Basic Law assumes a regulatory competence over questions of the German citizenship of persons for whom a connection to the territorial status of the German Reich on December 31, 1937 - and thus also over the spatial Scope of application of the Basic Law beyond - is given. "

“The Senate has repeatedly stated that the Basic Law is based on the continued existence of the German state people [...] and that the Federal Republic does not include all of Germany in terms of its state people and territory. Even after the Basic Treaty has been concluded, the German Democratic Republic is “another part of Germany”, for example its courts are “German courts” […]. Only if the separation of the German Democratic Republic from Germany were sealed through the free exercise of the right to self-determination, could the sovereign power exercised in the German Democratic Republic be qualified as a foreign state power detached from Germany from the point of view of the Basic Law. "

“Neither the Basic Law itself [...] nor the state organs of the Federal Republic of Germany formed on its basis rated this process as the downfall of the German state. Rather, the Federal Republic of Germany viewed itself from the start as being identical to the German Reich, the subject of international law. The fact that the territorial sovereignty of the Federal Republic of Germany is limited to the spatial scope of the Basic Law has not been able to change this identity of the subject. Even a final change in the status of parts of its national territory does not change the identity of a state subject under international law under international law. "

These constitutional assessments by the Federal Republic or its organs were only of importance for the international law question of the legal situation of the German Reich, as they represented the legal opinion of the Federal Republic.

Status under international law

Under international law, the German Reich was mostly treated as continuing, which can compensate in particular for doubts about the existence of effective state authority. The occupying powers passed numerous legal acts in which implicit or explicit reference was made to the rights and responsibilities for “ Germany as a whole ”. Before the GDR advocated the debellation theory , it also assumed that the German Reich would continue to exist (see above) . The Holy See assumed that the German Empire would continue to exist in the form of the Federal Republic by treating the Concordat concluded between it and the German Reich on July 20, 1933 as continuing between itself and the Federal Republic, and complained that the State of Lower Saxony had by the decree of the law on the public school system in Lower Saxony of September 14, 1954, violated this concordat (see BVerfGE 6, 309 - Reich Concordat ).

Further evidence can be found in the Teso decision of the Federal Constitutional Court (BVerfGE 77, 137 (157 ff.)).

It is also pointed out that "the Federal Republic of Germany may no longer move away from the Western states from the constant, legally based practice of the Federal Republic and the third states asserting the identity of the Federal Republic with the German Reich, because this practice [... ] Has established customary international law ; the simple assertion of the identity thesis by the Federal Republic and its recognition by third countries would not have resulted in such a binding under international law ”.

Schweitzer also points out what he believes to be a defensible opinion that the German Reich fell through dismembration and that two new states emerged with the establishment of the Federal Republic and the GDR.

Furthermore, in the London Debt Agreement and the further reparation policy, the Federal Republic was accepted by the international community as legally identical to the German Reich.

Legal consequences for the reunification of Germany

The topic was again topical on the occasion of the accession of the GDR to the scope of the Basic Law in 1990 (in contrast to the legal term “accession”, often imprecisely referred to as “German reunification”).

The clarification of the legal situation was relevant, for example to answer the question of whether the Federal Republic of Germany was the successor state of the German Reich (with all the implications of state succession that were not yet codified at the time, such as the continued validity of international treaties ) or was identical with it in terms of international law . Furthermore, it also depended on the clarification of who might be authorized to represent and recognize territorial claims or who could waive them.

The question was also of importance under state and constitutional law : While the Federal Republic would have had to be reconstituted in the event of the fall of the German Reich , otherwise only a reorganization would have been necessary, since at the end of the war the German state had been disorganized by the smashing of the National Socialist ruling apparatus . This in turn depended on the question of whether the creation of the Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany (GG) required the consent of the individual - then sovereign - German states alone , or whether the constitutive power originated in the entirety of the German, which is distributed over the individual states People lay.

In terms of international law, the legal situation is complex insofar as the occupation and assumption of government responsibility did not correspond to the requirements of the Hague Land Warfare Act or was measured against the classic three-element theory of Georg Jellinek . According to the latter, the three characteristics state territory , state people and effective state authority are constitutive for the qualification of a state as a subject of international law . With the unconditional surrender of the German armed forces on May 7th and 8th, 1945, which in the opinion of Dieter Blumenwitz "was only a military act and therefore could not decisively affect the legal substance of the German state authority", Germany became factual nevertheless relieved of all executive power, but continued to exist as a subject under international law.

The topic contains important legal theoretical aspects and touches on the essential foundations of international law.

Situation after the accession of the GDR to the Federal Republic

The contract between the Federal Republic of Germany and the German Democratic Republic on the establishment of the unity of Germany of August 31, 1990 regulated in Article 1 paragraph 1 that "with the entry into force of the accession of the German Democratic Republic to the Federal Republic of Germany" on October 3, 1990 ( "Reunification") "the states of Brandenburg, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, Saxony, Saxony-Anhalt and Thuringia became states of the Federal Republic of Germany", whereby the GDR perished as a subject of international law, while the Federal Republic continued to exist (the contracting parties themselves also assumed this, see Article 11 and 12). If one follows the continuation theory, the Federal Republic has since then not only been partially identical, but (fully) subject-identical to the German Reich.

According to the three-element doctrine, according to which the state presupposes a state territory, a state people and a state authority as a legal unit, the following chain of arguments results:

State people

A nation is the totality of physical citizens. Acquisition and loss of citizenship are based on the domestic law of the respective state, which - provided there is actually a genuine connection between state and person - is also relevant under international law.

Acquisition and loss of German citizenship are based on the Reich and Citizenship Act of July 22, 1913 (RGBl. 1913 p. 583), which, with some changes, is still in force today under the title Citizenship Act. Whether, in addition, Article 116 (1) of the Basic Law contains a statement relevant to international law about the extent of German citizenship is disputed.

In the Teso decision of 1987, the Federal Constitutional Court ruled that the people who had been granted citizenship of the GDR were also German citizens within the framework of public policy :

“The complainant's acquisition of citizenship of the German Democratic Republic had the effect that he at the same time acquired German citizenship within the meaning of Article 16 (1) and Article 116 (1) of the Basic Law. This legal effect did not come into effect by virtue of or due to an acquisition fact of the Reich and Citizenship Act [...]. However, it follows from the requirement to preserve the unity of German citizenship (Article 116.1 and Article 16.1 GG), which is a normative concretization of the reunification requirement contained in the Basic Law , that the acquisition of citizenship of the German Democratic Republic for the legal system the Federal Republic of Germany has the legal effect of acquiring German citizenship within the limits of public policy. "

This national feature was never really in question.

National territory

State territory is the area comprising the land area, the territorial sea and the air area that is under the territorial sovereignty of a state . The national feature “national territory” was not controversial as such, but it was in view of its extension to the countryside.

In Art. 7 para. 1 of the 1952 Germany Treaty, which came into force in 1955 (see above) , the contracting parties of the Federal Republic of Germany, the United States of America, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and the French Republic stated that the final definition of the borders of Germany by a freely negotiated peace agreement (referred to in the Potsdam Protocol as a "peace settlement") must be postponed:

“The signatory states agree that an essential goal of their common policy is a peace treaty settlement freely agreed between Germany and its former opponents for the whole of Germany, which should form the basis for a lasting peace. They still agree that the final definition of Germany's borders must be postponed until this settlement is reached. "

In addition to the rather unproblematic treaties between the Federal Republic of Germany to correct borders with Belgium (September 24, 1956), Luxembourg (July 11, 1959), the Netherlands (April 8, 1960 and October 30, 1980), Switzerland (November 23, 1964 and April 25 1977) and Austria (February 29, 1972 and April 20, 1977), there were long differences of opinion about the border with Poland.

Govern the there was the German eastern border for the first time in the Potsdam Agreement of 2 August 1945 in the east of the Oder-Neisse line lying areas of the German Reich as "former German territories" were called. The final demarcation was nevertheless reserved for a peace treaty. Also in the border treaty between the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of Poland of August 16, 1945, the final drawing of the boundary was reserved for a peace treaty. In the Görlitz Treaty concluded on July 6, 1950 between the GDR and Poland , the contracting parties assumed that Poland would have sovereignty over the areas east of the Oder-Neisse line. In the Warsaw Treaty of December 7, 1970 between the Federal Republic and Poland, the Federal Republic also recognized this border.

In the run-up to the reunification of Germany, Poland in particular called for a final settlement. As a result, the German Bundestag and the People's Chamber of the GDR passed resolutions of the same name on June 21, 1990, in which they expressed their will to finally establish the limit set in the previous treaties by means of an international treaty. This happened in the same year through the two-plus-four treaty of September 12 between the Federal Republic and the GDR and the four victorious powers and the German-Polish border treaty of November 14 between the Federal Republic and Poland :

“The contracting parties confirm the existing border between them, the course of which changes according to the agreement of June 6, 1950 between the German Democratic Republic and the Republic of Poland on the marking of the established and existing German-Polish state border and the agreements concluded for its implementation and supplementation (Act of January 27, 1951 on the execution of the marking of the state border between Germany and Poland; Treaty of May 22, 1989 between the German Democratic Republic and the People's Republic of Poland on the delimitation of the sea areas in the Oder Bay) and the treaty of December 7 1970 determined between the Federal Republic of Germany and the People's Republic of Poland on the basis of the normalization of their mutual relations. "

From the point of view of international law, the German Federal Government could not be assumed to be illegitimate. Even if the government had put itself to power, the border treaty it concluded would be effective, since international law only depends on the existence of state power, not on its nature.

After the demarcation was finally settled, only the irrelevant questions in this context about possible compensation had to be clarified.

Today only part of the border on Lake Constance is uncertain. In contrast to border rivers, such as the Dollart , through which the course of the border is determined in the absence of a border treaty agreement according to uniform international law regulations, there are no such international law regulations for border lakes. During the border course in the Untersee and in the Konstanzer Bucht by treaties between Baden and Switzerland (20 and 31 October 1854 as well as 28 April 1878) and between the German Empire and Switzerland (24 June 1878) and the Überlinger See is undisputed German territory, the borderline in the remaining part of the Obersee between Germany, Austria and Switzerland has not yet been clarified.

State authority

State power in the sense of international law is the sovereign right to exercise violence against people and things and includes personnel sovereignty over one's own nationals as well as territorial sovereignty over people and things within the national territory.

Article 7 of the Two-Plus-Four Treaty of September 12, 1990 stated:

(1) The French Republic, the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the United States of America hereby end their rights and responsibilities with regard to Berlin and Germany as a whole. As a result, the related quadrilateral agreements, resolutions, and practices related thereto will be terminated and all related Four Power institutions will be dissolved.

(2) The united Germany accordingly has full sovereignty over its internal and external affairs.

The regaining of full sovereignty was thus established. However, since the treaty only came into effect with the ratification of all contracting states on April 13, 1991, the four victorious powers made the declaration for the period from October 3, 1990 to suspend the effectiveness of the four-power rights and responsibilities .

With reunification, the question of the distinction between the all-German state authority as the state authority of the German Reich and the state authority of the Federal Republic no longer applies. If one followed the dismembration theory, the German Reich had already perished in 1949, 1954 or 1973 (see above) . On the other hand, if one follows the survival theory, the founding of the GDR can be viewed as an attempt at secession . The consequence of the secession would then have been the shrinking of the German Reich to the territory of the Federal Republic. In retrospect, this secession should have been seen as a failed attempt because of reunification.

Political agitation

The self- appointed provisional Reich governments and other, partly right-wing extremist groups within the "Reich Citizens' Movement" propagate, with reference to some of the aspects described above, that the German Reich as such still exists from an international law perspective and the Federal Republic of Germany would be an illegitimate regime . To this end, they cite some - albeit only very selected parts - of the above-mentioned decisions of the Federal Constitutional Court and academic articles, but interpret them in a generally unaccepted way to the contrary. In particular, the spatial identity and the identity as a subject of international law are not separated from one another: the spatial identity was indisputably not given in 1973. But as a subject of international law, the Federal Republic has always regarded itself as identical to the German Reich and is thus, so to speak, the German Reich, only under a different name. This is also what the BVerfG writes: "The Federal Republic of Germany is ... as a state identical to the state 'German Reich' ..." (E 36, 1 (16)).

The views of these people and groups are of no importance for assessing the legal situation. They refer to court decisions as “ideologically based delusions” which “are generally represented by right-wing agitators [...] or by psychopaths”.

The federal government classifies the "reichsbürgerbewegung" as a threat to internal security one, since there was a risk of a radicalization of individual offenders who modeled after Anders Behring Breivik to or National Socialist Underground (see. "NSU killings") offenses might commit.

Reception in the social sciences

As the legal historian Bernhard Diestelkamp stated in 1980, the theory that the German Reich survived the collapse of 1945 as a state contradicts the results of contemporary historical research. Because in the historical-political interpretation of the end of the war, the statehood of the German Reich is mostly considered to be obliterated. Wolfgang Schieder, for example, saw the "statehood of the German Reich" as "wiped out" by the Berlin Declaration of June 5, 1945. According to Heinrich August Winkler there was “no more German state power”. In a 1983 lecture, the philosopher Hermann Lübbe spoke of the “end of the empire”. Hans-Ulrich Wehler and other historians described the emergence of the Federal Republic of Germany and the GDR as the " founding of a state ", which presupposes that the previously existing state no longer existed. The political scientist Otwin Massing polemicizes that the judgment of the Federal Constitutional Court on the Basic Treaty “adheres to the thesis of Germany's continued existence in nowhere - whether it is transcendented by metaphysical entities, localized in the illusory world of legal-dogmatic semantics , or whether it is, as has been done before , banished to the cave of myth , product of own projection wishes as well as fear of loss and failure ”. This thesis is purely a historical myth , because Joachim Fest also assumes a final fall of the German Empire. The political scientist Herfried Münkler contradicts Massing, insofar as the continuation thesis has neither a narrative structure nor iconic moments - both constitutive elements of a myth. On the other hand, he calls it a legal fiction and writes that in 1945 the German Reich "ceased to exist as a politically sovereign actor." The term "legal fiction" can also be found in several historical works. The historian Manfred Görtemaker calls the prevailing doctrine of the Federal Republican constitutional and international law theory, according to which the empire has only lost its “ability to will and act” but has never ceased to exist legally, “little more than a legal dogmatic puzzle”.

In this context, Diestelkamp complains of misunderstandings of legal thinking by historians. The theory of the continued existence of the empire is a prime example of the historical impact of legal categories that even historians should not ignore. But lawyers, on the other hand, should take note of the contradiction between legal position and historical knowledge. The historian Walter Schwengler also regrets that historians showed little interest in the findings and interpretations of constitutional and international law experts. According to the legal historian Joachim Rückert , they believe they have to choose “between legal ghosts and common historian's sense”. Since this alternative is wrong, Rückert pleads for a combination of both perspectives and for a stronger reception of legal questions when depicting the collapse of the Nazi state.

meaning

The continued existence of Germany as a subject under international law through all the upheavals from at least 1871 to the present form of the Federal Republic of Germany is no longer in doubt. The prevailing opinion in jurisprudence is based on this, just like the organs of the Federal Republic speaking for them . Ultimately, however, this can neither be proven nor refuted, since legal disputes are not a condition that can be experimentally investigated as in the natural sciences.

If one assumes that it will continue to exist, the question of its significance arises. Immediately, the continued existence would only mean the continuity of the legal personality of the state as a subject under international law. Much more interesting, however, is what would indirectly rule out continued existence. If, for example, conspiracy theorists assume that it will continue to exist, this already rules out their further claim that the Federal Republic of Germany is “non-existent” and / or “illegal”. If one takes as a basis the constitutive, but also essential elements of "national territory", "state people" and "state authority", then at the latest with the accession of the GDR to the Federal Republic of Germany and the (re-) acquisition of full sovereignty of the Federal Republic Either the German Reich finally perished in the absence of effective state authority and a new state, the Federal Republic, emerged on its territory, or the Federal Republic is fully identical with the German Reich under international law. Its area was therefore legally reduced at the latest due to the accession of the GDR to the Federal Republic of Germany and with the regaining of full sovereignty - the completion of German unity - whereby the size of the national territory is not at all important, but only its existence .

In this context, the “illegality” of the Federal Republic could not even mean illegality under international law. The three elements of the state are constitutive for the quality of the state, so today there is absolutely no need for any further explicit or implicit act of recognition by other subjects of international law or a judgment by the community of states. Recognition by other states is only of a declaratory nature and therefore has no significance for the existence of a state. The categories legal / illegal do not exist in this context.

The claim that the Federal Republic is constitutionally illegal also makes little sense. The underlying constitution is in each of the two possible cases (see above) the German Basic Law : If one assumes the downfall of the German Reich, the newly created Federal Republic of Germany would have given itself a new constitution, the Basic Law. If the German Reich had continued to exist, the Federal Republic, which is fully identical with it, would have given itself a new constitution, as it had before in the history of the German Reich ( Bismarck's Reich constitution of April 16, 1871 became the responsibility of the government to parliament and thus to the parliamentary monarchy seriously changed by the October reform of October 28, 1918; the Weimar constitution of August 11, 1919 was a complete break with the previous Reich constitution). The Federal Republic under the Bonn Basic Law, however, has to be consistent with itself measured in terms of itself, so it cannot be “constitutionally illegal”.

“With the unconditional surrender of all armed forces on May 7th and 8th, 1945, the German Reich in its historical guise collapsed completely. Its organs and other constitutional structures that were still in existence at that time ceased to exist at all levels in May 1945; in the following years, most recently through German reunification on October 3, 1990, new structures that were historically and legally unrestricted by general elections were established kicked. "

literature

- Adolf Arndt : The German state as a legal problem. Lecture given to the Berlin Legal Society on December 18, 1959 (= series of the Legal Society of Berlin 3). Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 1960.

- Dieter Blumenwitz : What is Germany? Principles of constitutional and international law on the German question and their consequences for German Ostpolitik , 3rd edition, Kulturstiftung der deutschen Vertaufenen, Bonn 1989, ISBN 3-88557-064-5 .

- German Bundestag and Federal Archives (ed.): The Parliamentary Council 1948–1949. Files and minutes . Vol. II: The Constitutional Convention on Herrenchiemsee . Boppard am Rhein 1981, ISBN 3-7646-1671-7 .

- Bernhard Diestelkamp : Legal and constitutional problems to the early history of the Federal Republic of Germany . In: JuS 1981, pp. 409-413.

- Bernhard Diestelkamp: Legal history as contemporary history. Historical considerations on the development and implementation of the theory of the continued existence of the German Reich as a state after 1945 . In: ZNR 1985, pp. 181-207.

- Werner Frotscher , Bodo Pieroth : Constitutional history . 7th edition, CH Beck, Munich 2008, Rn. 638 ff., ISBN 978-3-406-58060-4 .

- Clemens von Goetze : The rights of the allies to participate in German unification . In: NJW 1990, issue 35, p. 2161 ff.

- Gilbert Gornig : The status of Germany under international law between 1945 and 1990. Also a contribution to the problems of state succession. Wilhelm Fink, Munich 2007, ISBN 978-3-7705-4461-5 .

- Jens Hacker: The legal status of Germany from the perspective of the GDR . Science and politics, Cologne 1974, ISBN 3-804-68490-4 .

- Matthias Herdegen : International Law . 4th edition, CH Beck, Munich 2005, ISBN 3-406-53277-2 .

- Otto Kimminich : Deutsche Verfassungsgeschichte , 2nd edition, Nomos, Baden-Baden 1987, pp. 658 to 664.

- Michael Schweitzer: Constitutional Law III. Constitutional law, international law, European law . 8th edition, CF Müller, Heidelberg 2004, Rn. 612 ff. (And 6th edition 1997, marginal number 629 f.), ISBN 3-8114-9024-9 .

- Ulrich Scheuner : The constitutional continuity in Germany . In: DVBl. 1950, pp. 481-485 and 514-516.

Web links

- The “Berlin Declaration” of June 5, 1945 on documentArchiv.de or on verfassungen.de

- BVerfGE 2, 1 - SRP ban, judgment of the First Senate of October 23, 1952, Az. 1 BvB 1/51.

- BVerfGE 2, 266 - Emergency room, decision of the First Senate of May 7, 1953, Az. 1 BvL 104/52.

- BVerfGE 3, 288 - Professional soldier relationships, judgment of the First Senate of February 26, 1954, Az. 1 BvR 371/52.

- BVerfGE 6, 309 - Reich Concordat, judgment of the Second Senate of March 26, 1957, Az. 2 BvG 1/55.

- BVerfGE 36, 1 - Basic Agreement, judgment of the Second Senate of July 31, 1973 on the oral hearing of June 19, 1973, Az. 2 BvF 1/73.

- BVerfGE 37, 57 - Arrest warrant in Berlin, decision of the Second Senate of March 27, 1974, Az. 2 BvR 38/74.

- BVerfGE 77, 137 - Teso, decision of the Second Senate of October 21, 1987, Az. 2 BvR 373/83.

Remarks

- ^ Bernhard Diestelkamp: Legal and constitutional problems on the early history of the Federal Republic of Germany. 1st part: The "zero hour" . In: JuS 1980, p. 402 f.

- ^ Bernhard Diestelkamp: Legal and constitutional problems on the early history of the Federal Republic of Germany. 1st part: The "zero hour" . In: JuS 1980, p. 403.

- ^ Bernhard Diestelkamp: Legal and constitutional problems on the early history of the Federal Republic of Germany. 1st part: The "zero hour" . In: JuS 1980, p. 403 f.

- ^ Bernhard Diestelkamp: Legal and constitutional problems on the early history of the Federal Republic of Germany. 1st part: The "zero hour" . In: JuS 1980, p. 405.

- ↑ Werner Frotscher , Bodo Pieroth : Verfassungsgeschichte . 17th edition, CH Beck, Munich 2018, Rn. 694.

- ^ A b c Bernhard Diestelkamp: Legal and constitutional problems on the early history of the Federal Republic of Germany. 1st part: The "zero hour" . In: JuS 1980, p. 481 f.

- ^ A b Bernhard Diestelkamp: Legal history as contemporary history. Historical considerations on the development and implementation of the theory of the continued existence of the German Reich as a state after 1945 . In: ZNR 7 (1985), p. 184.

- ↑ Werner Frotscher, Bodo Pieroth: Verfassungsgeschichte . 17th edition, CH Beck, Munich 2018, Rn. 698

- ↑ Werner Frotscher, Bodo Pieroth: Verfassungsgeschichte . 17th edition, CH Beck, Munich 2018, Rn. 699.

- ^ Bernhard Diestelkamp: Legal history as contemporary history. Historical considerations on the development and implementation of the theory of the continued existence of the German Reich as a state after 1945 . In: ZNR 7 (1985), p. 185.

- ^ A b Michael Stolleis : History of Public Law in Germany . Vol. 4. Constitutional and Administrative Law Studies in West and East 1945–1990 . CH Beck, Munich 2012, p. 34.

- ^ Bernhard Diestelkamp: Legal history as contemporary history. Historical considerations on the development and implementation of the theory of the continued existence of the German Reich as a state after 1945 . In: ZNR 7 (1985), p. 186.

- ^ Bernhard Diestelkamp: Legal history as contemporary history. Historical considerations on the development and implementation of the theory of the continued existence of the German Reich as a state after 1945 . In: ZNR 7 (1985), p. 186 f.

- ^ Bernhard Diestelkamp: Legal history as contemporary history. Historical considerations on the development and implementation of the theory of the continued existence of the German Reich as a state after 1945 . In: ZNR 7 (1985), pp. 188-190.

- ^ Bernhard Diestelkamp: Legal history as contemporary history. Historical considerations on the development and implementation of the theory of the continued existence of the German Reich as a state after 1945 . In: ZNR 7 (1985), p. 191.

- ^ Bernhard Diestelkamp: Legal history as contemporary history. Historical considerations on the development and implementation of the theory of the continued existence of the German Reich as a state after 1945 . In: ZNR 7 (1985), pp. 191-193.

- ↑ Oliver Dörr: Incorporation as an offense of state succession (= writings on international law , vol. 120), Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1995, p. 332 f.

- ^ A b c Georg Dahm , Jost Delbrück , Rüdiger Wolfrum : Völkerrecht , Vol. I / 1: The basics. The subjects of international law , 2nd edition, de Gruyter, Berlin 1989, p. 144 f.

- ↑ BGBl. 1949 p. 1 ff.

- ↑ Frotscher / Pieroth: Verfassungsgeschichte , Rn. 744

- ↑ GDR GBl. 1949, p. 5 ff.

- ↑ Frotscher / Pieroth: Verfassungsgeschichte , Rn. 747

- ↑ Frotscher / Pieroth: Verfassungsgeschichte , Rn. 676.

- ↑ Frotscher / Pieroth: Verfassungsgeschichte , Rn. 677.

- ↑ Schweitzer: Staatsrecht III , 8th edition, Rn. 622.

- ↑ See BVerfGE 37, 57 (60 f.) - arrest warrant in Berlin.

- ↑ RGBl. 1910 p. 107; came into force for the German Reich on January 26, 1910.

- ↑ Hans Kelsen : The International Legal Status of Germany to be established immediately upon Termination of the War , AJIL 38 (1944), p. 689 ff.

- ^ Hans Kelsen: The Legal Status of Germany According to the Declaration of Berlin . In: AJIL 39 (1945), p. 518 ff.

- ↑ Frotscher / Pieroth: Verfassungsgeschichte , Rn. 648.

- ↑ Schweitzer: Staatsrecht III , 6th edition, Rn. 629

- ^ Hermann Graml: Between Yalta and Potsdam. On the American planning for Germany in the spring of 1945 . In: Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 24 (1976), p. 508.

- ↑ Cf. Frotscher / Pieroth: Verfassungsgeschichte , Rn. 648, 705.

- ↑ Schweitzer: Staatsrecht III , 6th edition, Rn. 630

- ↑ Frotscher / Pieroth: Verfassungsgeschichte , Rn. 651.

- ↑ Frotscher / Pieroth: Verfassungsgeschichte , Rn. 725

- ^ Wilhelm Pieck: Inaugural address of October 11, 1949 , quoted in nach Ost und West , No. 11 / November 1949, p. 9 f.

- ^ Instead of all, Klaus Stern , The State Law of the Federal Republic of Germany , Volume V, Beck, Munich 2000, p. 1964 f.

- ↑ See Wilhelm Pieck, President of the GDR , in his inaugural address of October 11, 1949 when the GDR was founded

- ↑ Even in the years when the text of the GDR anthem ("Deutschland einig Vaterland") was no longer sung, seventh classes in the GDR were reminded that on October 7, 1949 the GDR was founded by the "Provisional People's Chamber " , because until October 15, 1950 "the state organs formed in 1949 described themselves as provisional" (textbook Citizenship Studies, 2nd edition, Berlin / GDR 1983, p. 44).

- ↑ Schweitzer: Staatsrecht III , 8th edition, Rn. 631 f.

- ↑ See the majority opinion in the report on the Constitutional Convention on Herrenchiemsee, in: The Parliamentary Council 1948–1949. Files and protocols , Vol. II, p. 509 ff.

- ↑ BVerfGE 2, 1 (56, cit. Para. 254) from 1952 - SRP ban

- ↑ BVerfGE 2, 266 (277, cit. Para. 30) from 1953 - emergency room

- ↑ BVerfGE 3, 288 (319 f., Cited paragraph 92) from 1954 - professional soldier relationships: “The assumption of such a remainder of mutual legal relationships presupposes that the German Reich continued to exist as a partner in such a legal relationship beyond May 8, 1945 , a legal opinion from which the Federal Constitutional Court [...] started. "

- ↑ BVerfGE 3, 288 (319 f., Cit. Para. 92) from 1954 - professional soldier relationships

- ↑ BVerfGE 6, 309 (336 ff., Cit. Para. 160, para. 166) from 1957 - Reich Concordat

- ↑ BVerfGE 36, 1 (15 ff.) - Basic Agreement

- ↑ BVerfGE 77, 137 (150 ff.) - Teso

- ↑ a b c d Schweitzer: Staatsrecht III , 8th edition, Rn. 637.

- ↑ Herdegen: Völkerrecht , 4th ed., § 8, marginal no. 12.

- ↑ RGBl. II p. 679.

- ↑ Quotation from Albert Bleckmann , "On the determination and interpretation of customary law", in: ZaöRV 37 (1977), Max Planck Institute for Foreign Public Law and International Law , Heidelberg / Munich 1977, pp. 504 ff. (512) .

- ↑ For the whole see the report on the Constitutional Convention on Herrenchiemsee , in: The Parliamentary Council 1948–1949. Files and protocols , Vol. II, p. 509 ff.

- ↑ Dieter Blumenwitz explains in this regard that “even with the arrest of the last - no longer effective - Reich government (' managing government Dönitz') by the victorious powers on May 23, 1945, the core of the German state power was not yet affected, since the State authority does not depend on the fate of one of its functionaries and, moreover, German state authority was still exercised at the middle and lower level ”(quoted afterwards, Think I of Germany. Answers to the German Question , 2 vols., Bavarian State Center for Political Education , Munich 1989, Vol. 1, p. 67).

- ^ Josef L. Kunz , The Status of Occupied Germany under International Law: A Legal Dilemma , The Western Political Quarterly, Vol. 3, No. 4 (Dec 1950), pp. 538-565.

- ↑ See Klaus Stern, The State Law of the Federal Republic of Germany , Vol. V, 2000, § 135, p. 1964.

- ↑ Schweitzer: Staatsrecht III , 8th edition, Rn. 541 ff.

- ↑ Schweitzer: Staatsrecht III , 8th edition, Rn 547 ff.

- ↑ BVerfGE 77, 137 (148 f., Cit. Para. 31)

- ↑ Schweitzer: Staatsrecht III , 8th edition, Rn. 570 f.

- ↑ Schweitzer: Staatsrecht III , 8th edition, Rn. 572 f.

- ^ Art. 1 of the German-Polish border treaty

- ↑ Schweitzer: Staatsrecht III , 8th edition, Rn. 568.

- ↑ Schweitzer: Staatsrecht III , 8th edition, Rn. 574.

- ↑ Schweitzer: Staatsrecht III , 8th edition, Rn. 665.

- ↑ AG Duisburg, decision of January 26, 2006, Az. 46 K 361/04, para. 11 ( full text ).

- ↑ Model Breivik , in: Der Spiegel 1/2013, p. 11.

- ^ Bernhard Diestelkamp: Legal and constitutional problems on the early history of the Federal Republic of Germany . In: Juristische Schulung 1980, pp. 401–405, here p. 402; Joachim Rückert: The elimination of the German Reich - the historical and legal-historical dimension of a suspension situation. In: Anselm Doering-Manteuffel (Hrsg.): Structural features of the German history of the 20th century (= writings of the historical college, vol. 63), Oldenbourg, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-486-58057-4 , pp. 65–94 , here p. 66 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Wolfgang Schieder: The upheavals of 1918, 1933, 1945 and 1989 as turning points in German history . In: the same and Dietrich Papenfuß (ed.): German upheavals in the 20th century . Böhlau, Weimar 2000, ISBN 978-3-412-31968-7 , pp. 3–18, here p. 10 (accessed from De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Heinrich August Winkler: The long way to the west . German history II. From the “Third Reich” to reunification . CH Beck, Munich 2014, p. 117.

- ↑ Hermann Lübbe: National Socialism in the German Post-War Consciousness . In: Historische Zeitschrift 236 (1983), pp. 579-599, here p. 587 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ^ Hans-Ulrich Wehler: German history of society. Vol. 5: Federal Republic and GDR 1949–1990 , CH Beck, Munich 2008.

- ↑ Joachim Fest: The German Question: The Open Dilemma. In: Wolfgang Jäger and Werner Link (eds.): The Changing Republic 1974–1982: The Schmidt era (= History of the Federal Republic of Germany , Vol. 5 / II). Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, Stuttgart 1987, pp. 433-446, quoted from Otwin Massing: Identity als Mythopoem. On the political symbolization function of constitutional judgments , in: Staat und Recht 38, Heft 2 (1989), pp. 145–154, the quotation on p. 148.

- ↑ Herfried Münkler: The Germans and their myths . Rowohlt Berlin Verlag, Berlin 2008, p. 413 u. 542.

- ↑ Walter Schwengler: The end of the Third Reich - also the end of the German Reich? In: Hans-Erich Volkmann (Ed.): End of the Third Reich - End of the Second World War. A perspective review. Piper, Munich / Zurich 1995, pp. 173–199, here p. 194; Florian Roth: The idea of the nation in political discourse. The Federal Republic of Germany between new Ostpolitik and reunification 1969–1990 , Nomos, Baden-Baden 1995, p. 97; Ines Lehmann: German unification seen from the outside. Fear, concerns and expectations. Volume IV: Poland and Czechoslovakia , Peter Lang, Frankfurt am Main 2004, p. 25; Joachim Wintzer: Germany and the League of Nations 1918–1926 , Schöningh, Paderborn 2006, p. 97; Oliver Schmolke: Revision. After 1968 - On the political change in historical images in the Federal Republic of Germany . Diss. FU Berlin 2007, p. 141.

- ^ Manfred Görtemaker: History of the Federal Republic of Germany. From the foundation to the present , CH Beck, Munich 1999, p. 18.

- ^ Bernhard Diestelkamp: Legal and constitutional problems on the early history of the Federal Republic of Germany . In: Juristische Schulung 1980, pp. 401–405, here p. 402.

- ↑ Walter Schwengler: The end of the Third Reich - also the end of the German Reich? In: Hans-Erich Volkmann (Ed.): End of the Third Reich - End of the Second World War. A perspective review. Piper, Munich / Zurich 1995, pp. 173–199, here p. 194.

- ↑ Joachim Rückert: The elimination of the German Empire - the historical and legal-historical dimension of a suspension situation. In: Anselm Doering-Manteuffel (Hrsg.): Structural features of the German history of the 20th century (= writings of the historical college, vol. 63), Oldenbourg, Munich 2006, ISBN 3-486-58057-4 , pp. 65-94 , here pp. 65–68 (accessed via De Gruyter Online).

- ↑ Schweitzer: Staatsrecht III , Rn. 572 u. 662 ff.

- ↑ See the judgment of the Adentere Commission on the decision on how the UN should behave towards the successor states of the USSR . Here, too, the determinative character of the recognition was confirmed.

- ↑ See BVerfG, judgment of October 23, 1952 - 1 BvB 1/51, BVerfGE 2, 1 , 56 f .; Judgment of December 17, 1953 - 1 BvR 147/52, BVerfGE 3, 58 .

- ^ District court Duisburg, decision of January 26, 2006 (Az .: 46 K 361/04, printed in: NJW 2006, pp. 3577-3588).