Classis Germanica

The Classis Germanica was a part of the Roman navy in Germania superior and Germania inferior . It was next to the Canal Fleet ( Classis Britannica ) one of the largest naval associations of the Roman Empire and ranked above all other provincial fleets.

The Roman Rhine fleet was founded around 13 BC. Set up. Your units were responsible for monitoring the entire Rhine (from the confluence of the Vinxtbach ), its navigable tributaries as well as the coastal strip of Zuidersee and the North Sea in the area of the Rhine- Maas - Scheldt Delta. Subsequently, the mouths of the rivers on the right bank of the Rhine were secured in order to maintain smooth transit and trade traffic on the Rhine. The affiliation of the Classis Germanica to the Lower Germanic army (Exercitus Germaniae Inferioris) is confirmed by a military diploma (found in the Netherlands ) from the reign of Trajan . In addition to the auxiliary troops there, it also lists the Rhine fleet, which (in a modified form of organization) presumably existed until the late 4th century.

Fleet operations

The history of the Rhine fleet begins in the time of the Germanic Wars from 13 BC. Since then, the Roman high command has concentrated the legions and auxiliary troops on the Rhine, and from the beginning the fleet has also been involved in the campaigns of the Roman army. During this time, the operations of the Rhine fleet were still offensive. With the abandonment of the expansion plans in the tribal areas to the right of the Rhine by Tiberius in 17 AD, the tasks of the Classis Germanica also changed.

1st to 2nd century

During the Augustan period, the Romans launched several massive offensives. We know of several large-scale landing operations by Roman troops on the North Sea coast, which were closely coordinated with the advance of the land forces. For this purpose, Drusus led the Rhine fleet in connection with the Drusus campaigns (12 to 8 BC) through one - or more - newly dug canals from the Zuider Sea to the North Sea ( fossa Drusiana ) . Since Friesen and Chauken only had primitive dugout canoes, he could enter the mouth of the Weser (Visurgis) unhindered with his vastly superior forces and then quickly subdue both tribes.

The advance of Tiberius to the Elbe (Albis) in the year 5 AD was accomplished by means of a combined sea and land operation. His fleet drove up the river to the Lauenburg area and reunited there with the army. In the same year, the Romans sailed even further north, "to the area of the Cimbri ". The exact route and end point of the expedition are unknown. It is certain that the ships also passed the Herculis Columnae (Pillars of Hercules on Heligoland ). They probably advanced as far as Cape Skagen , since Pliny reports in this connection about a " Cape Cimbri". The Cimbri were still settling in northern Jutland at that time . After circumnavigating the cape, a large sea was found, which - according to the chronicler Velleius Paterculus - "partly saw, partly known from hearsay". The presence of a Roman fleet in this area is likely to have contributed significantly to the fact that the Germanic coastal tribes did not join the anti-Roman coalition among the Cheruscans after the defeat of Varus as a precaution .

In 15 AD a Roman army under the leadership of Germanicus invaded Germania again: The fleet landed at what is now Rheine on the Ems for a total of four legions, which then marched to the scene of the Varus Battle in order to, among other things, attack the fallen buried. After heavy fighting with the Germanic tribes they retreated to their ships waiting on the Ems. Just a year later, Germanicus started one of the largest amphibious operations in ancient war history. Under the orders of his legates Silius, Anteius and Caecina, he had a new fleet of over a thousand ships laid on the keel, including special constructions such as B. Flat-bottomed landing craft with rudders at the stern and bow, transporters ( actuariae ) for throwing guns, wide arks for cavalry horses, bridge building material as well as food and equipment. With her and an army of over 8,000 men on board, Germanicus set sail again in the spring of 16 AD.

Germanicus built the Bataver Island (today Beveland and Walcheren ) into a fortified bridgehead, as it had an ideal strategic location as a starting point for the campaign to Germania. From the Bataverinsel the fleet advanced to the mouth of the Ems, where the army went ashore at what is now Jemgum . After the battles on the Idistaviso plain and on the Angrivarian Wall (between Weser and Steinhuder Meer ), in which the Angrivarian , Brukterer and Cheruscan tribes were defeated, part of the army was to be returned to their garrisons by the Classis Germanica. Almost the entire fleet with the troops on board fell victim to a severe storm. Germanicus himself stranded in the Chauken settlement area , but remained unharmed.

In 28 AD, the Frisians rebelled again against Roman rule: The Rhine fleet brought an expeditionary army into the area of the uprising, among other things to relieve the fortified port of Flevum ( Velsen ), which was besieged at the time . Nevertheless, the defection of the Frisians could not be prevented and the Romans lost control of the North Sea coast to the mouth of the Rhine. 46 to 47 the Romans tried again to subdue the Frisians; Despite the use of the fleet, the Romans could not hold their own for long.

48 under the legate Gnaeus Domitius Corbulo a 27 km long canal (fossa Corbulonis) was completed between the mouths of the Oude Maas and the Oude Rijn. It was mainly used for troop and supply transports.

In 68/69 AD a revolt broke out among the allied Batavians under Iulius Civilis in the course of the Roman civil war (year of the Four Emperors ) , which spread to almost all other Rhine-Germanic tribes. All forts north of Mogontiacum were besieged or destroyed. The Classis Germanica was severely restricted in its operations by the low water level of the Rhine, and most of the Batavian Rojer and auxiliaries proved to be unreliable and deserted in large numbers to the rebels. On top of all this, it was also poorly managed and could hardly contribute anything to support the hard-pressed Rhine legions. Legions I and II Adiutrix, who were recruited from sailors, were among the legions that were sent to Lower Germany to crush the revolt. An entire squadron of the Classis Germanica fell into the hands of the Batavians through treason in 70 and was then used against the Romans. When the Commander-in-Chief of the Rhine Army, Quintus Petillius Cerialis , had the Legio XIIII Gemina put ashore by units of the Classis Britannica to reinforce the rebels, the Caninefats, who were related to the Batavern, were ambushed and almost completely wiped out. Cerialis hurried to help from Novaesium with the Classis Germanica, but was attacked by the Batavians during the night and lost all of his ships (including his Trireme ). However, the losses could be quickly replaced. With their new fleet, the Batavians now tried to raise supplies from the Romans from Gaul in the Rhine delta. In the mouth of the Maas (Mosa) , the numerically inferior but better educated Classis Germanica finally took on the fight. However, there was only a brief skirmish. Civilis withdrew to the north bank of the Rhine, and the Romans devastated the settlement area of the Batavians. The fleet never succeeded in achieving decisive successes in the Batavian revolt.

In 89 AD, large parts of the Rhine army mutinied against Emperor Domitian . The Classis Germanica, however, was loyal to the ruling imperial family and proved itself in the overthrow of the rebels. For this she was awarded the honorary title classis pia fidelis Domitiana .

The scenes on the Trajan's Column show that Trajan's naval units were also involved in the Dacer Wars (101 to 106). In an inscription, a certain Manlius Felix is named as Praefectus classium Pannonicae et Germanicae (Admiral of the Pannonian and Germanic fleet). So it should have commanded both fleets in personal union. The consolidation of fleet units stationed a long way apart for campaigns was still common in later times.

3rd to 4th century

After the end of the so-called Gallic Empire under Postumus and after repeated heavy incursions by the Franks, the Classis Germanica perished in the last third of the 3rd century AD. From this time on, the Rhine legions maintained their own flotillas (milites liburnarii) . Roman river warships on the Rhine were not mentioned again until the year 280: Germanic invaders succeeded in setting several of the new naves lusoriae on fire.

In 298 Constantius I used the Rhine fleet against the Alemanni , who had established themselves on a river island. His son and successor Constantine I modernized the Rhine fleet and replaced the Liburnians entirely with Lusorien. This meant that maritime operations could now also be carried out on the Upper Rhine. In 306 Constantine had troops set across the Rhine and with them devastated the settlement areas of the Brukterer . In 313, too, the Rhine fleet advanced again into Germanic territory.

In 355 Julian was appointed Caesar of the West. Under his rule, in the course of defense efforts in the 2nd half of the 4th century, the Rhine fleet was upgraded along the river border. It was used for several campaigns and Rhine crossings: In 356/357 defensive battles took place on the Rhine and Main. In the winter of 357/358, Julian's troops enclosed a large group of Frankish looters on the Meuse island. Constantly patrolling up and down Lusoria prevented the permanent formation of a solid ice cover, so that the Franks could no longer escape across the river and finally had to surrender to the Romans after two months of siege. In 359 a squadron of 40 ships was used against the Alamanni.

Until Valentinian I succeeded in keeping the Rhine fleet operational, at that time a new border defense concept was developed that was largely based on the Rhine fleet, which was now divided into a chain of bases on the left bank of the Rhine and a large number of heavily fortified rural castles. Warships patrolled the Rhine almost constantly from these bases. Ports and forts were built in Speyer , Worms and Altrip and the Ländeburgi on the right bank of the Rhine in Zullestein , Mannheim-Neckarau and Ladenburg were built. Apparently there were always clashes with Germanic invaders, as some dedicatory inscriptions from the Rhine border attest. After the invasion of the Vandals , Suebi and Alans on New Year's Eve of 407, the fleet organization finally dissolved.

Officers and men

Little is known about the command hierarchy of the Rhine fleet. The supreme command was carried out by a praefectus classis from the knightly class , which was however subordinate to the governor (legatus Augusti pro praetore) of the respective province. A sub-prefect (subpraefectus) stood by his side as chief of staff and deputy . The praepositus classis ranked among the prefects ; Each fleet usually had two such officers. He also took on independent commands. The later Emperor Pertinax also served as prefect in the Classis Germanica. The above officers each had their own staff with their adjutants. A nauarchus princeps or nauarchus archigybernes was used as the flotilla chief. In the 3rd century the rank of the naval tribune was created (tribunus classis), which took over the duties of the first nauarch. Later it was also called tribunus liburnarum (= tribune of warships).

The crew of a trireme consisted of the officers (trierarchi) , the rowers (remiges) and a centurion of marines (manipulares / milites liburnarii) . The crew (classiari / classici) was divided into two groups, the nautical personnel and the marine infantry . Their service time was 26 years (in contrast to the 20 to 25 years for a legionnaire), from the 3rd century onwards 28 years, occasionally one knows of even longer service periods. After their honorable discharge ( honesta missio ) , they were compensated with money or land and were usually granted citizenship if they had entered the army as peregrini (= foreigners). They were only allowed to marry after they had finished their active service.

In the l. In the 20th century AD, most of their relatives came from the countries in which they were originally excavated. For Lower Germany this meant that the teams came from Gaul, Spain and the Balkans. As with their commanders, the Germanic-Gallic element also increasingly prevailed among the auxiliaries from the 2nd century onwards. The only exception here was the fleet. Since the sea service was not very respected by the Roman soldiers, freedmen ( liberti ) in particular served there . The majority of the fleet soldiers therefore came from the east of the empire even in the 2nd and 3rd centuries. This was also the case in the Classis Germanica. An inscription from Cologne proves, among other things, the presence of Greek fleet soldiers:

- “Lucius Octavius, son of Lucius, from Elaia, helmsman, 58 years old, with 34 years of service, is buried here. Dionysius, son of Plestharches, from Tralles, scribe, set the tomb for his services "

In the early imperial era, the fleet was an integral part of the Roman Rhine Army. This means that their soldiers were also used as milites classiari (naval or marine soldiers). For the Germanic provinces there are also references to the legions' own naval divisions (liburnarii) , e.g. B. in Upper Germany. Do the anchor with a stamp of the XVI. Legion, which was in Mainz in Claudian times, and the tombstone of a shipbuilder of the XXII. Legion from the late 1st and early 2nd centuries to the time when the rivers Rhine and Neckar still formed the imperial border, this no longer applies to two members of the XXII. Legion, which as optiones navaliorum probably supervised the legion's own shipyard. Both belong to the late 2nd century when the front Limes already existed. Against the assumption that the XXII. Legion only owned cargo ships at that time, one of their brick stamps speaks from the 2nd / 3rd centuries. Century. A warship can be clearly identified under the legion's name. The naval department of the XXII. Legion in the time after 260 AD, when the area on the right bank of the Rhine was abandoned. After that the Rhine was again the imperial border. It was well secured on the left bank by the Limes fort. On the right bank there were small outposts at the confluence of the main tributaries, which in some cases could only be reached by ship. Up to five lusoria could be stationed in these so-called “ Ländeburgi ”.

Ship types

The types of ships that are presumed to be part of the Rhine fleet were freighters ( Navis actuaria ) , rafts, light guard ships and some heavy warships. They could be rowed as well as sailed.

The most common type of ship in the 1st and 2nd centuries was the bireme or liburna (double-breasted), which was originally used by Illyrian pirates. She was fast and extremely manoeuvrable and, like all ancient warships, had a ram at the bow. River liburnas were usually about 21 meters long, 3.30 meters wide and had a draft of about 0.7 meters. The crew consisted of 44 Rojers, 4 sailors and 16 marines. In addition to the river Liburnians, larger triremes are also known, which were very similar to the Liburnians , but differed from them by a third additional row of Rojer (three-breasted).

According to finds from Alphen-Zwammerdam, freighters and rafts could be up to 30 m long. Numerous wreckage finds on the Rhine and Lake Neuchâtel also testify to the use of pram boats in Roman times. This was a box-shaped ship with a mast, shallow draft and ramp-like ends on both sides of the hull, which could carry a payload of up to 30 t.

From the 3rd century onwards, the backbone of the late antique provincial fleets were the much smaller and agile naves lusoriae , which operated from bank forts and watchtowers (Ländeburgi). In the early 3rd century, ships such as the tomb sculpture of a Roman wine merchant from Neumagen were probably also used as transport or combat vehicles (see Neumagener Weinschiff ).

function

The main task of the river forces was to ensure free navigation. Their surveillance area included the rivers Rhine, Scheldt, Maas and their tributaries, as well as the coastal strips on the Zuidersee and North Sea. With the end of the plans to conquer the Germania Magna on the right bank of the Rhine under Tiberius, the tasks of the Classis Germanica also change. It was now mainly used for daily patrols on the Rhine. Operations along the North Sea coast became less and less important.

Since the time of the Drusus' Germania offensives, the logistical tasks of the Rhine fleet have been even more important than the use in campaigns . The castles on the Lippe (Lippia) were supplied from Xanten / Vetera . These heavily exposed warehouses often also have fortified port facilities. The governors could also use the ships for their needs at any time. For example, were obtained from the fractions of the Brohltales in Siebengebirge transported stones obtained by the fleet. Food such as grain and wine, which could only be moved with difficulty by land, were transported.

tactics

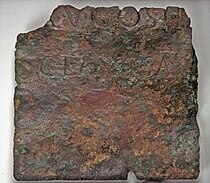

With the beginning of the reign of the Flavians in the last third of the 1st century, the situation on the Rhine border had largely stabilized again. In addition to the river patrol service, the members of the fleet took care of the extraction and transport of building materials, as the freight costs by water were much lower than by land (around 1/6 of the road tariffs). This is demonstrated above all by the numerous brick stamps found in the regions of what is now the Netherlands, as well as some dedicatory inscriptions from the quarries in Brohl Valley and Siebengebirge . There is also a dedicatory inscription dedicated to the well-being of Emperor Antoninus Pius (today in the Rheinisches Landesmuseum, Bonn), which reports on the transport of building materials by Classis Germanica barges for the construction of the Forum of Xanten (Colonia Ulpia Traiana) .

In the 270s at the latest, the old-fashioned Classis Germanica dissolved. Until then, its area of operation had been largely limited to the Lower Rhine. With the increasing threat to the rivers Rhine and Danube after the abandonment of the Dekumatenland , however, the strategic situation changed. Concentrating the fleet on a few central points no longer made sense. Due to the new political realities on the Rhine, large sections of the river, but also the mouths of the waters flowing from the Barbaricum, had to be monitored more strictly and more seamlessly. In contrast to the Upper and Middle Rhine, the winding course of the Upper Rhine and its dense floodplains made efficient surveillance by forts impossible. These new challenges could only be met through constant military presence on the river and on its banks.

The new promising concept for border protection on the Rhine was therefore a decentralized forward defense. By abandoning the doctrine of centralizing the fleet and distributing it to smaller forts and burgi , numerous units could be brought together at focal points on the border within a few hours if necessary. The neighboring forts or watchtowers also had to be alerted quickly in an emergency. The best way to do this was with the smaller and more agile navis Lusoria , with which the potential intruders could either be confronted directly on the Rhine river or in amphibious operations together with the land army.

The daily range of action of the river combat ships at that time was up to 15 km. The distance between the forts and Ländeburgi was on average between 15 and 30 km. Driving down the river, a Lusoria could have reached the nearest base in around 75–150 minutes, upstream it would take around 2–4 hours. With smooth communication (and a minimum of three ships per base), the high command was able to position at least four patrol boats at endangered crossings within a few hours and thus throw up to 100 liburnarii into battle right at the beginning of the battle . It was therefore quite possible that the attackers could be taken under effective fire by the Roman border guards shortly after they appeared on the banks of the Rhine. Due to the superiority of their lusoria, the Limitanei were able, under favorable circumstances, to confront even numerically far superior barbarian associations. The Germanic tribes on the Rhine were unable to counter the highly developed Roman river combat ships with anything nearly equivalent.

Due to their flat-bottom construction, the Roman Lusorians were also able to penetrate far into the waters coming from the Barbaricum, for example in the course of an armed reconnaissance mission. The Teutons liked to use these tributaries as staging areas for their surprise attacks on Roman territory. The findings from this type of “maritime early warning system” were certainly highly valued by the Roman commanders. Another protection was the widely ramified, in places almost impenetrable and swampy floodplain landscapes of the Upper Rhine as well as the presence of numerous meandering tributaries, which also made an approach to the border zone much more difficult. However, if the invaders had overcome all the difficulties, there was still a chance of intercepting them again at the latest on the Rhine, when they returned from their raids, to steal the booty from them and then to distribute it again among the border guards involved in the fighting (see also hoard from Neupotz ).

Naval bases

The headquarters of Classis Germanica was initially in Vetera ( Xanten ), later in the Cologne-Alteburg castle . The metropolis of Lower Germany, the Colonia Claudia Ara Agrippinensium (CCAA), was the provincial capital, an important economic center and was of great supraregional importance as a trading center. The Rhine, in turn, served as the most important traffic route for the transport of goods produced in Cologne, but also for the import of goods from other provinces. Late antique bases are proven for Mainz / Straubing, Speyer and Passau . After the Battle of Mursa , 351 AD, the naval port in Mainz / Mogontiacum was massively expanded and became one of the most important bases of the Rhine fleet. The main use of the war port in Mainz (harbor moles in Dimesser Ort, Ingelheimer Aue and am Brand as well as remains of bank fortifications and a shipyard on Neutorstrasse / Dagobertstrasse) took place in the second half of the 3rd and 4th centuries, when the Rhine came to the border of the Germania was great . The Rhine fleet, which was reorganized in the first third of the 4th century, was only able to develop its combat strength to the full because the banks of the Rhine - especially on the central section - were manned at regular intervals with forts as supply bases and safe ports. Effective use of the Rhine fleet would have been hard to imagine without these camps. It is assumed that the late antique (left bank of the Rhine) fortifications between Bingen and Bonn were built according to a uniform plan during the reign of Constantine's sons (approx. 320-350).

| Ancient name | Closest place |

| Vetera Castra |

Xanten (main base up to 50) |

| Colonia Claudia Agrippinensium |

Flottenkastell Alteburg (headquarters / navalia since 50) |

| Aliso |

Holders (on the lip) |

| Antunnacum | Then after |

| Argentoratum | Strasbourg |

| Bingium | Bingen |

| Bonna | Bonn |

| Confluentes | Koblenz |

| Lugdunum Batavorum |

Katwijk -Brittenburg (at the mouth of the Rhine / NL) |

| Mogontiacum | Mainz |

| Nigrum Pullum | near Zwammerdam / NL |

| unknown | Rumpst on the Rupel / B |

| unknown | Base ad Rur / near Jülich |

| unknown | Base at Jemgum ad Ems |

| Novaesium | Neuss |

| Noviomagus Batavorum | Nijmegen |

| Noviomagus Nemetum | Speyer |

| Praetorium Aggripinae | Valkenburg (South Holland) |

| Traiectum | Utrecht |

See also

literature

- Rudolf Aaskamp, Christoph Schäfer (Ed.): Project Römerschiff. Köhlers Verlagsgesellschaft, Hamburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7822-0977-9

- Jos Bazelmans, Esther Jansma: The De Meern ship discovery (Netherlands). In: Ancient World. 36, 2005, pp. 23-29.

- Tilmann Bechert : Germania Inferior, a province on the northern border of the Roman Empire . (= Orbis Provinciarum ; = Zabern's illustrated books of archeology ). Zabern, Mainz 2007, ISBN 978-3-8053-2400-7 , p. 41f.

- Ronald Bockius: Shipping and shipbuilding in antiquity . Stuttgart 2007, esp. P. 50 ff. (Special issue of the journal 'Archäologie in Deutschland' 2007).

- Ronald Bockius, Dietwulf Baatz : Vegetius and the Roman fleet. (= Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum, research institute for prehistory and early history, monographs. Volume 39). Habelt, Bonn 1997, ISBN 3-88467-038-7 .

- Karl Christ : History of the Roman Empire, from Augustus to Constantine . CH Beck, Munich 1995, ISBN 3-406-36316-4 , p. 418.

- Thomas Fischer , Maureen Carroll: Archaeological excavations 1995/96 in the camp of the Roman fleet (Classis Germanica) in Cologne-Marienburg. In: Kölner Jahrbuch. 32, Berlin 1999, pp. 519-568.

- Thomas Fischer: Recent research on the Roman fleet camp Cologne-Alteburg. In: Thomas Grünewald: (Ed.): Germania inferior. Settlement, society and economy on the border of the Roman-Germanic world, contributions of the German-Dutch colloquium in the regional museum Xanten, 21.-24. September 1999. (= Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. Supplementary volume 28). de Gruyter, Berlin 2001, pp. 547-564.

- Thomas Fischer: Fleets . In: ders. (Ed.): The Roman Provinces. An introduction to their archeology . Theiss, Stuttgart 2001, pp. 109-110.

- Olaf Höckmann: Roman ship formations on the Upper and Middle Rhine and the defense of the Rhine border in late antiquity. In: Yearbook of the Roman-Germanic Central Museum Mainz. 33, 1986, pp. 369-416.

- Olaf Höckmann: Shipping between the Alps and the North Sea. In: Ludwig Wamser (Ed.): The Romans between the Alps and the North Sea. Civilizing legacy of a European military power, catalog handbook for the state exhibition of the Free State of Bavaria, Rosenheim 2000 . Mainz 2000, pp. 264-267.

- Heinrich Clemens Konen: Classis Germanica. The Roman Rhine fleet in the 1st – 3rd Century AD (= Pharos. 15). St. Katharinen 2000, ISBN 3-89590-106-7 .

- Barbara Pferdehirt : The Museum of Ancient Shipbuilding I . Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum, Mainz 1995, ISBN 3-88467-033-6 .

- Barbara horse herdsman: The Roman fleet in service. The largest complex of finds from late antique ships across the Alps was recovered in Mainz. In: Ancient World. 36, 2005, pp. 8-16.

- Georg Alexander Rost: From the sea and sea trade in antiquity: a study from a maritime-military point of view . Gruner, Amsterdam 1968.

- Christoph Schäfer : Lusoria, a Roman ship in an experiment . Koehlers Verlagsgesellschaft, Hamburg 2008, ISBN 978-3-7822-0976-2 .

- Hans DL Viereck: The Roman fleet. Classis Romana. Köhlers Verlagsgesellschaft, Hamburg 1996, ISBN 3-930656-33-7 .

- Berndmark Heukemes : The late Roman Burgus of Lopodunum, Ladenburg am Neckar, preliminary report of the investigation from 1979. Festschrift for Hartwig Zürn. 1981.

- Johannes Prammer : Lands, port facilities and port projects in Straubing. Zweckverband Industriegebiet mit Donauhafen Straubing-Sand, 1996.

- Johannes Prammer: Gäubodenmuseum, Straubing. Prehistory Department, Straubing 1987.

- Raffaele D Amato, Graham Sumner: Imperial Roman Naval Forces 31 BC - AD 500. (= Men at Arms. 451). Osprey Publishing, Oxford 2009, ISBN 978-1-84603-317-9 .

Web links

- Thomas Fischer: The Roman fleet in Germania

Remarks

- ↑ CIL 13, 8252 .

- ↑ CIL 13, 12061 .

- ↑ Florus 2.30.

- ^ Velleius Paterculus 2, 106.

- ↑ Tacitus, Annals 2,9-24.

- ^ Tacitus, Historiae 4, 14 ff.

- ↑ Raffaele D Amato, Graham Sumner: 2009, p. 7.

- ↑ Tacitus, Historiae 4,16-17.

- ↑ Tacitus, Historiae 4.79.

- ^ Tacitus, Historiae 5.23.

- ↑ CIL 3, 726

- ^ Historia Augusta , Bonos 15.

- ↑ Panegyricus 6.6.

- ↑ Panegyricus 6.13.

- ↑ Panegyricus 12:22.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus 16.11-12 and 17.1.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus 17.2.

- ↑ Ammianus Marcellinus 18.2.

- ↑ Heukemes 1981; Baatz / Bockius 1997.

- ↑ Höckmann: 1986, p. 403 f.

- ↑ CIL 13, 8323 .

- ↑ Raffaele D Amato, Graham Sumner: 2009, p. 7.

- ^ Tilmann Bechert: 2007, p. 42.

- ↑ Viereck 1996, pp. 87-88.

- ↑ Cato, de agri cultura 22, 3.

- ↑ CIL 13, 8036

- ↑ Christoph Schäfer, 2008, p. 90.

- ↑ Bockius: 2006.

- ↑ Höckmann: 1986, p. 415.

- ↑ Bockius: 2006, p. 212.

- ↑ Prammer 1987a; the same in 1996.

- ↑ Olaf Höckmann 1986, pp. 369-416.