Black kite

| Black kite | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Black kite ( Milvus migrans ) |

||||||||||

| Systematics | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Scientific name | ||||||||||

| Milvus migrans | ||||||||||

| ( Boddaert , 1783) |

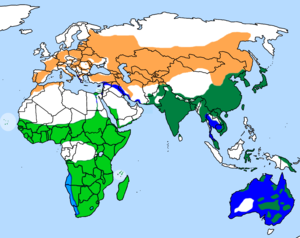

The black kite or black kite ( Milvus migrans ) is a bird of prey about the size of a buzzard from the family of hawks (Accipitridae). In contrast to the closely related red kite ( Milvus milvus ), whose breeding area is essentially limited to Europe , the black kite has a huge distribution area, which includes large parts of the Palearctic in addition to large areas of the Indomalayan fauna and Australasia. According to this widespread distribution, up to twelve subspecies have been described, seven of which are generally recognized. The position of the two yellow-billed kites, Milvus migrans aegyptius and Milvus migrans parasitus , native to Africa is unclear ; they are listed both as an independent species Milvus aegyptius (with the subspecies Milvus aegyptius parasitus ) and as a subspecies of Milvus migrans .

Although the black kite is also found in extremely dry areas, it usually shows a strong preference for wetter areas or seeks the vicinity of water surfaces. He is a food generalist whose food spectrum is extremely broad and, in addition to carrion and waste, includes a variety of mostly rather small self-caught prey. The species is one of the most widespread birds of prey and is the most common species of birds of prey in some areas. Although the population has declined regionally, it is considered safe worldwide.

Appearance of the nominate form M. m. migrans

Black kites are medium-sized birds of prey, fairly uniformly dark brown in color, with little contrast, in which only the lighter head, throat and neck areas and a light band on the upper wing stand out from the rest of the plumage.

Black kites are not colored until they are five years old at the earliest. Head and neck areas are then light gray, sometimes, especially with birds in their last transitional dress, also slightly yellowish. A dark dotted line of the head plumage can be clearly seen, which increases in the neck and upper chest area. The back is uniformly matt dark brown. The chest and abdominal plumage is a little lighter, often also clearly rust-brown in color. The control springs are gray-brown on the top and brownish to cinnamon-colored on the underside.

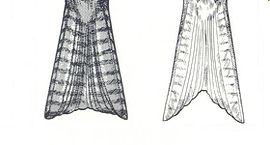

The tail is only weakly forked, if it is fanned out it appears triangular. A dark banding is only indicated and can only be seen up close. The large and small arm covers usually have the color of the breast plumage and contrast quite clearly with the dark, almost black arm and hand wings . The legs of colored birds are yellow, the claws black. The upper beak is also black, the lower beak yellowish. The wax skin is bright yellow. The iris color of the black kite changes from brown to age-typical yellow at the earliest at the age of seven .

The long and narrow wings, which are conspicuously angled in the carpal joint, end in six (five in some juveniles) clearly recognizable, deeply fingered hand wings. A dark mark in the area of the carpal joint is clearly present in some subspecies, but is almost completely absent in others. The black kite flies very elegantly with flat, relatively fast wing beats. It often sails and glides, with the wings, in contrast to those of the red kite, not bent above the horizontal in the same flight position, but slightly rounded downwards. The constant twisting, fanning and folding of the tail, which is only more noticeable in the red kite, is also noticeable.

Young birds that have just flown out have a much lighter head and chest area than the colored ones, but light cinnamon or beige tones predominate in young birds in contrast to the white-gray color of these body parts in adult birds. The iris is still medium brown, the claws are slate gray. Overall, the juvenile plumage is a bit lighter and more contrasting in color, especially on the upper side of the body.

The sexes do not differ in color. The reverse sexual dimorphism, which is evident in many birds of prey, is also only weakly pronounced. Females are a maximum of 6% larger and up to 17% heavier than males.

Dimensions and body mass

The body length of adult birds varies depending on the subspecies and gender between 46 and 66 centimeters, the wingspan between 120 and 153 centimeters. Males of the smallest and lightest subspecies M. m. affinis weigh about 500 grams, those of the largest subspecies M. m. lineatus about 850 grams. The heaviest Lineatus females can weigh over 1000 grams.

voice

Black kites are very vocal and acoustically noticeable even outside the courtship season . The main calls are extremely variable in pitch and expression, so that they can hardly be transcribed. Depending on the mood, it can be soft, melodious trills, a gull-like, slightly annoying sounding meow or even neighing calls. Black kites often sing in a duet.

Systematics

Subspecies

The number of subspecies varies considerably depending on the doctrine. A total of twelve subspecies have been described so far, six to seven of which are generally recognized.

The afrotropic subspecies show a comparatively large relationship to the subspecies of the Palearctic, so that their position as the species Milvus aegyptius ssp. seems to be confirmed by molecular biology. This separation was recently completed, so that Milvus aegyptius has a species status with one subspecies ( M. aegyptius parasitus ). For them the common name Yellow-billed Kite seems to prevail; a corresponding German name (Gelbschnabelmilan?) has not yet been established. Even M. m. lineatus seems to be genetically further removed from other subspecies than they are from each other, so that species rank is also being considered for it.

Apparently all subspecies hybridize in the contact zones and produce intermediately colored offspring, which are variously listed as subspecies ( tienschanicus , ferghanensis , formosanus, etc.).

Distribution of the subspecies

- Milvus migrans migrans ( Boddaert , 1783): The nominate form breeds in most of Europe. The northwest border of the closed distribution runs through northern France , northern Belgium and northwest Germany . To the west and north of this line, breeding occurrences are rare and unstable. Single broods were found in the Netherlands (1984 and 1996) and in Norway . In northern Sweden there is an irregular, small, isolated breeding population.

- Occurrences in Austria and the Czech Republic are sparse and in decline in the eastern parts of the country , and the black kite is only sparsely represented in Poland , the Ukraine and the Balkans . M. m. Also comes to Cyprus and Sicily . migrans as a breeding bird, but is absent on the other Mediterranean islands. In Asia, the northern limit of distribution roughly coincides with the limit of the closed coniferous forest belt. To the east, the deposits extend beyond the Urals , where a wide contact zone with M. m. lineatus exists. The southern limit of distribution lies in the Atlas region and extends westward over Turkey , the Middle East , Iran and Afghanistan to the Himalayan region, where the nominate form with M. m. govinda comes into contact. In the north of the Arabian Peninsula there is a contact zone with M. m. aegyptius .

- M. m. lineatus ( Gray , 1831): This is the largest and also the heaviest subspecies. The at M. m. Migrans gray-white head and neck parts are light brown in this subspecies, the tail is light rust brown. There is a noticeable black spot in the ear area, after which this subspecies is also called "black-eared kite" in German. In the area of the carpal joint, a clear, light, almost white spot can be seen. The color of the iris does not seem to change from brown to yellow in old age. This subspecies is most similar to the red kite. The latest molecular genetic studies show a relatively large genetic distance to other subspecies and suggest that M. m. lineatus species rank close.

- The breeding occurrences of M. m. lineatus connect east of the Urals to those of the nominate form and extend to the Pacific coast. The northern limit of the brood distribution fluctuates around 65 degrees north, but clearly exceeds the Arctic Circle on the central reaches of the Jana . In the east, the subspecies breeds on almost all islands in the marginal seas of the northwestern Pacific, including the Japanese archipelago , with the exception of Sakhalin . To the south is M. m. lineatus spread to the northern edge of the Himalayas, further east the contact zones with M. m. govinda in northern Indochina .

- M. m. govinda Sykes , 1832: This subspecies is smaller than the nominate form and overall poor in contrast gray-brown, sometimes also dirty sand-colored. The head plumage has a reddish brown tinge, the black shaft markings are mostly clearly recognizable. The white drawing of the underside of the wing in the area of the hand swing bases is also striking.

- M. m. govinda occurs in large areas of Pakistan , on the Indian subcontinent , in the northern part of Sri Lanka , eastwards via Myanmar and Thailand to Malaysia .

- M. m. formosanus Kuroda , 1920: Small island breed on Hainan and Taiwan . Very similar to M. m. govinda . Largely resident bird in the breeding area. The validity of this subspecies is being questioned.

- M. m. affinis Gould , 1838: The smallest subspecies has a relatively uniform dark brown appearance. The plumage is lighter in the shoulder area, so that a clear diagonal stripe can be seen on the upper side of the wing.

- This subspecies breeds on Sulawesi and many of the Lesser Sunda Islands , such as Lombok , Sumba and Timor . It is also found in the northeastern part of New Guinea and widely in Australia.

- M. m. aegyptius (Syn. M. aegyptius ) ( Gmelin , 1788): The birds of this subspecies are somewhat smaller than European specimens of the nominate form. The plumage is reddish-brown, on the cinnamon-colored tail some narrow, lighter bands can be seen. The white wing field in the area of the wrist is relatively clear. The beak of the young birds, which are spotted below, is black until they are three years old and then changes to the yellow typical of the two African subspecies.

- The occurrences begin on the Sinai and stretch south along the Nile Valley and the eastern coastal areas of the Red Sea . This subspecies is also a breeding bird in Somalia , Ethiopia and probably in some coastal stretches of Kenya . The breeding birds on the southern Arabian Peninsula (sometimes classified as M. m. Arabicus ) have shorter wings and individually black or yellow beaks.

- M. m. parasitus (Syn. M. aegyptius parasitus ) ( Daudin , 1800): This subspecies is somewhat smaller than the one described above and has a relatively low-contrast, matt brown color. The underside is lighter and has a dark cinnamon tone. The tail is clearly banded, the beak of adult birds is always bright yellow. The subspecies is distributed all over Africa south of the Sahara and also breeds on the Comoros and Madagascar . The latest molecular genetic studies suggest that M. m. parasitus is neither to be regarded as a subspecies of Milvus migrans nor of Milvus aegyptius , but represents an independent species.

habitat

The Black Kite is considered as his German trivial name water Milan or Seemilan prove to be highly water-bound type. The preference for habitats near water, especially leafy lakeside sections but of wetlands or rows of trees along slow-flowing rivers, is only in birds, the northern in Palearctic breeding, strongly pronounced. In such habitats, the nominate form reaches the highest stand density and the highest percentage reproduction rate. But even in these regions the black kite can colonize distant, even extremely dry regions, provided that there is a sufficient supply of potential prey and groups of trees as nesting sites.

In the case of the other subspecies, a latent affinity for water-rich habitats is less evident or not at all recognizable. The availability of food and suitable breeding opportunities alone seem to be decisive for a successful settlement. The populated habitats can be correspondingly diverse: Mangrove swamps at river mouths are used as well as cultivated landscapes or high dry mountain steppes such as in the Altai . Some subspecies, especially the two that occur in Africa, show a nutritionally close connection to humans. The black kite lives there on the outskirts of cities and is a user of human waste along with a number of bird species, for example the capped vulture ( Necrosyrtes monachus ). The Australasian subspecies M. m. Leads a largely nomadic life with irregular breeding cycles in the most varied of habitats, which also include the edge areas of deserts . affinis .

nutrition

Food spectrum

As a food generalist and food opportunist, the black kite has a wide range of foods. It hunts live prey, but also feeds on carrion and various types of waste, such as those produced in slaughterhouses or fish factories. Landfill sites are also searched for usable residues. It can capture and carry off live prey up to the size of a small rabbit and live fish almost up to its own weight, but mostly its prey is smaller. The composition of the prey depends on the habitat of the subspecies.

Black kites that breed near water primarily prey on live and dead fish. In Central and Eastern Europe, the roach ( Rutilus rutilus ) and bream ( Abramis brama ) predominate . Fish food can reach 80 percent of the total food weight in such populations. In addition, various birds to Partridge size and mammals such as rabbits , small rabbits , rats and mice , captured. In arid areas, the species prey mainly on birds, reptiles , amphibians and smaller mammals (such as hedgehogs (Erinaceidae) and jerboa (Dipodidae)). Pigeons (Columbidae) and crows (Corvidae) can make up a large proportion of prey in dry habitats. But various large insects , earthworms and snails are also regularly consumed. Vegetarian food is consumed in the course of the use of human waste. In West and Central Africa the fruit shells of the oil palm ( Elaeis guineensis ) form for the wintering European black kites as well as for the kites of the subspecies M. m. parasitus is an important vegetarian complementary food.

Food acquisition

Black kites are search aircraft fighters. In a slow, usually quite low search flight, prey or carrion are spotted and often carried over by flying over them. Living or dead fish are picked up from the surface of the water and cranked at a suitable place . The black kite also usually surprises birds such as crows, quails or partridges on the ground and carries them away. The situation is similar with reptiles and amphibians. Successful aerial hunts for birds have rarely been observed, but do happen.

The black kite is often the first bird species to appear on the carrion. He recycles both small animals run over on roads and highways and large carcasses together with large birds of prey. M. m. parasitus and M. m. Some govinda have specialized in the use of human waste and appear in large numbers in landfills, on marketplaces, near slaughterhouses or fish factories, i.e. wherever usable waste is available. Even fishing boats in the coastal area are followed by swarms of black kites. It is not uncommon for pieces of meat or fish to be carried away from market stalls, it has even been observed that black kites steal sandwiches from people or grab grilled meat from the grill.

Like other birds of prey, black kites follow the fire fronts of forest and steppe fires in order to pick up the fleeing or already dead animals. Occasionally they even carry burning twigs that they later drop to catch prey by spreading the fires. Black kites can also be seen behind swarms of migrating field locusts .

Black kites often try to steal their prey from other birds. Seagulls and buzzards are particularly hard hit . Seagulls, herons , ibises , storks and large kingfishers are sometimes harassed until they regurgitate food that has already been swallowed.

behavior

General and social behavior

Black kites are diurnal. The first prey flights begin shortly before sunrise. Usually they go to their resting places before sunset. They only remain active until late at dusk when the food supply is particularly cheap, for example when the cockchafer appears in large numbers. The lunchtime hours are mostly used for plumage care or spent dozing. During the breeding season, the female stays at the eyrie and the male near it. Outside the breeding season, the kites look for sleeping trees, where societies of up to several hundred birds can gather. Black kites are largely gregarious and only defend the closer nest environment. In the winter quarters, the pullers are usually not associated with the subspecies resident there, but form their own groups that roam widely.

The European, Central and North Asian birds are extremely shy and cautious towards humans. Even with minor disturbances, they move away from the eyrie and circle at a greater distance from it. South, Southeast Asian and African kites, which are closely tied to humans in terms of nutritional ecology, have reduced their escape distances from humans to a few meters where they are not pursued and nest, breed and sleep in the immediate vicinity. Various historical sources report on city-breeding birds of prey in European cities. It could have been black kites. Today there is only one urban colony of the nominate form in Istanbul .

hikes

The black kites of the northern Palearctic are long-distance migrants , those of the southern Palearctic, the Afrotropic and East Asia mostly resident birds or short-range migrants . The Australian subspecies M. m. affinis leads a nomadic life without fixed breeding cycles and without fixed breeding territory. Black kites are thermal sailors and therefore migrate during the day and almost always in large groups.

European black kites overwinter south of the Sahara, south to the Cape Province , but most of them in west and central Africa north of the equator. The migration distances of European birds rarely exceed 5000 kilometers, but in individual cases they can exceed 8000 kilometers. Individual black kites already overwinter in southwest and southeast Europe as well as in Sicily . The Mediterranean is crossed generally to the straits select few individuals, the narrow point Sicily- Cap Bon or drag along the Balkan route on the Aegean island bridge. The Sahara is widely flown over. West Asian M. m. migrans and M. m. lineatus reach the East to South African wintering area via the Arabian Peninsula and the Red Sea . The Central Asian black kites overwinter in southern Iran , southern Pakistan, and central and southern India, the eastern Siberian in southern China and Southeast Asia. The main migration time of the central and northern Palearctic kites is between the end of July and mid-September, with the Swiss and southern German birds leaving their breeding area around two to three weeks earlier than the northeast German or Polish birds. The main migration over Gibraltar was largely completed by the end of August, while it reached its peak over the Bosporus at this time. Along the eastern Black Sea coast , the intense black kite migration lasts throughout September and only subsides in the first decade of October. In Central Europe, single black kites can be found in the breeding area in mild weather until October and November. Reports of black kites overwintering in Central Europe are mostly due to confusion with the red kite. In Switzerland, however, a successful wintering of a black kite in the urban area of Geneva was confirmed in 2003 .

The return home begins at the beginning of February and takes place essentially on the same routes as the departure, but Westerners seem to choose the route Cap Bon – Sicily much more frequently on the home journey. In the breeding area, central and northern Palearctic birds appear at the beginning of March at the earliest, but usually not before the end of March or beginning of April.

New migratory black kites usually spend the summer in their winter quarters. With increasing age, the migrating kites get closer to the area of their birth, but only return to their place of birth when they reach sexual maturity.

Breeding biology

overview

Black kites breed for the first time in their fourth year of life at the earliest. Occasionally, copulation and nest building activities have been found in younger kites, but no successful broods have been reported. The duration of the pair bond has not been exhaustively researched; in any case, both breeding season marriages and long-term relationships occur. Whether the latter are due to the species' great loyalty to the breeding site or whether there is a pair cohesion in winter quarters is still the subject of research. Obviously, individual birds return from their winter quarters already paired. During the courtship up to the early rearing of the young, conspecifics that fly into the immediate vicinity of the nest are consequently driven away, mostly by calling rows, often also by flying towards them. However, physical confrontations have not yet been observed. Alien raptors as well as potential nest predators such as crows or martens, and in some areas also snakes, are attacked immediately and violently. So far, little research has been done into the territorial behavior of colony-breeding black kites. Colony-breeding pairs only defend the immediate nest environment, the feeding grounds are apparently shared with conspecifics without conflict.

Horstbau and courtship

Immediately after arriving at the nesting site, the first bird to arrive (more often the male than the female) begins building its nest or repairing an old nest. The nest size and its structure are extremely variable, so that one cannot speak of a typical black kite nest. Black kite nests can be noticeably small, sloppily assembled structures the size of a crow's nest, but they can also be stately, solid structures one meter in diameter and more. The basic structure is made up of branches and twigs, a wide variety of materials are used for the interior upholstery, very often also waste, but also grass, moss, leaves, animal hair and bird feathers. Black kites always bring in relatively large clumps of earth or clay to clad the clumps. The tendency of the black kite to use plastic materials for the cladding of the eyrie has proven to be problematic for the rearing of young, as this can cause puddles to form in the eyrie, which lead to hypothermia of both the clutch and the chicks. Both partners participate in building the nest, but the male is much more intense than the female.

The tree species seems to play only a subordinate role in the choice of the nest location, more important is an approach that is unobstructed from above. Often, therefore, overbusters or edge trees are chosen as nest trees. Most of the clumps in the crown area are in a strong forked branch, less often in a fork of strong side branches, occasionally a few meters from the trunk. In addition to tree nests, nests on lattice masts and in rock niches were also found. Some populations, for example in the Atlas Mountains and Cape Verde , are pure rock breeders. Ground broods were found extremely rarely. Horst locations on buildings, however, are quite common for the African subspecies.

Black kites occasionally take over nests of other bird species, such as those of cormorants , crows, red kites and various other birds of prey, and conversely, black kite nests of other species of birds of prey are also used.

Within their own species, the horbar stands can only be a few meters. It is not uncommon for nests to be set up less than 100 meters from other nests of birds of prey that are flown over, sometimes in the middle of heron or cormorant colonies.

Mating occurs even during the construction of the nest, which the female prompts for with the horizontal posture typical of raptors and with a quiet whimper. Two copulations can follow each other in a few minutes. When the weather is nice, black kites show sightseeing flights over their nesting area, in which impressive flight acrobatics such as garland flights (rhythmic steep rise and fall), spinning with mutual entanglement or flying with their backs to the ground, can be embedded. With the development of the first egg, these activities stop. At this point, the female also ceases to hunt independently and is taken care of by the male during the breeding season and the first rearing phase of the chicks.

Clutch and brood

Black kites start breeding relatively late in the year, the earliest egg-laying in Central Europe occurs at the beginning of April, the main breeding season does not start until the last decade of April. If the clutch is lost early, there may be a new clutch.

The clutches usually consist of two to three, more rarely four and in exceptional cases five eggs. Additional clutches often only contain one egg. The lackluster eggs are short oval usually rare long oval and have pale white, or greenish isabellfarbigem reason often sepia-colored stains on it receives from the overall very similar eggs of the buzzard is different with rötlichtonigen spots. In size, shape and mass, they are roughly equivalent to medium-sized chicken eggs.

The eggs are laid at intervals of two to three days and incubated immediately, but usually not yet firmly. The female spends most of its time on the clutch, only occasionally is it briefly replaced by the male. After an incubation period of about 32 days, the young hatch, between which, depending on the oviposition, there can be considerable developmental differences. The older siblings often push the youngest away from the prey, and sometimes attack it directly. Often dead chicks are cut up and fed. In the first two weeks, the male alone creates the food, which the female at the eyrie takes over, divides and feeds to the young. Nestling food consists largely of live prey, primarily from small mammals and birds. Fish are not fed for the first two weeks. When the young no longer have to be constantly hovered or shadowed, the female also takes part in the prey flights. Occasionally, non-breeding black kites, and very rarely also red kites, were observed as brood helpers .

The young birds begin their first flight exercises at around 32 days and can move away from the nest at 40 days. Overall, however, the development time of nestlings varies greatly from person to person. It can take more than 50 days to fly out. Fledglings with less than 45 days have also been observed.

Even after the young birds leave the nest, the nest remains the center of the black kite family for at least three to four weeks. The prey brought by the parents is handed over on it, and the cubs return to sleep at it or in its immediate vicinity. Young black kites become independent relatively late, between 80 and 90 days of age. Around six weeks after leaving, they have learned to hack prey independently and are gradually leaving their parents' territory.

Mixed broods

In the wild, mixed breeds between red and black kites have occasionally been found. The black kite was mostly the female bird. Successful breeding between a male black kite and a hybrid female was also known. Such mixed broods are more common in captivity. In the Aukrug Nature Park in Mittelholstein, a mixed couple bred successfully for 6 years. After the red kite was absent, a hybrid from a previous brood apparently took its place.

In Cape Verde there are regular mixed breeds between the native Cape Verde milan and the black kite that immigrated about a hundred years ago. The Kapverdemilan is considered either as a subspecies of the red kite ( Milvus milvus fasciicauda ) or as a separate species ( Milvus fasciicauda ). These mixed broods produce fertile offspring which continue to mate. It is therefore questionable whether pure Cape Verde silanes still exist.

Existence and endangerment

The black kite is considered the most common bird of prey worldwide. According to the IUCN, its populations are not currently threatened, although there are indications of a slight decline. The populations in Europe are estimated at 130,000 to 200,000 animals. Exact numbers on population sizes and exact assessments of the population trends outside of Europe are only available for parts of the huge distribution area, which give rise to fears of strongly negative population developments for some populations in Asian Russia. In Europe, however, the species is classified with VU (= vulnerable). The decline in stocks in Spain and in large parts of Eastern and Southeastern Europe are primarily responsible for this. In Central Europe, stocks have remained largely stable or increased slightly over the past ten years, and in central and south-eastern France they have even increased considerably. The stock situation in Germany was also inconsistent up to the end of the 1990s: strong and moderately strong increases in Lower Saxony , Bavaria , Baden-Württemberg , Thuringia and Saxony resulted in some not inconsiderable stock and area losses in Schleswig-Holstein , Berlin-Brandenburg and Mecklenburg -Vorpommern opposite. In recent years, however, there has been a consistently positive trend in almost all federal states. In some German federal states, there were even significant increases in stock and area expansions.

In Switzerland, which is home to a large number of black kites with up to 1500 breeding pairs - compared to the size of the country - the population development is unclear. Colony-like breeding in some of the large Swiss lakes, such as Lake Neuchâtel , Lake Biel or the eastern part of Lake Geneva , has decreased significantly or has already stopped. Instead, the species increasingly migrated to cattle breeding areas and is now breeding there at heights of 1000 m above sea level. NN and more. In Eastern Austria, the already small populations of the black kite are continuously decreasing. The main causes of the population decline are still the destruction of biotopes, in particular the draining of wetlands, the conversion of mixed forests into pure spruce cultures as well as river regulation and the associated destruction of alluvial forest areas. Direct tracking through shooting and poisoning also plays a major role in the negative population development. Thousands of kites are killed every year, especially at the narrow points of the train routes, such as some Pyrenees passes , on Malta , in Lebanon and along the Nile Valley. Similar topographical traps with enormous hunting pressure exist for Southwest Asian migrants in the Caucasus . The declining eutrophication of many (central) European lakes and the often earlier covering of landfills also seem to have an unfavorable effect on the stocks .

Life expectancy

The oldest ringbird found in the wild was 24 years old. Some recoveries of similar old black kites show that the species can reach a very old age under favorable conditions. However, the individual life expectancy is significantly lower for this long-distance migrant . About 40 percent of black kites do not survive the first year of life. This mortality rate decreases very significantly with increasing age. It is not known how high the average percentage of a vintage that reaches breeding maturity is. If conclusions can be drawn from the red kite, however, it will not be far above 30 percent.

Name derivation

The Latin noun miluus , later milvus, denotes a larger bird of prey. It can mean buzzard, hawk, consecration or kite. Migrans comes from the Latin verb migrare and means wandering . Black kite is actually not correct, the brown kite would more closely match the appearance of this bird of prey. The Swedish ( Brun glada ) and the Italian ( Nibbio bruno ) species name take better account of the appearance.

literature

- Hans-Günther Bauer and Peter Berthold : The breeding birds of Central Europe. Existence and endangerment. Aula-Wiesbaden 1998 pp. 88-89, ISBN 3-89104-613-8 .

- Mark Beaman and Steven Madge: Handbook of Bird Identification. Europe and Western Palearctic. Ulmer-Stuttgart 1998. pp. 181 and 232, ISBN 3-8001-3471-3 .

- James Ferguson and David A. Christie: Raptors of the World. Houghton Mifflin Company Boston, New York 2001. pp. 381-386; 92, ISBN 0-618-12762-3 .

- Dick Forsman: The Raptors of Europe and The Middle East. Christopher Helm London 2003. pp. 65-76, ISBN 0-7136-6515-7 .

- Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim (Hrsg.): Handbuch der Vögel Mitteleuropas , arr. u. a. by Kurt M. Bauer and Urs N. Glutz von Blotzheim. 17 vols. In 23 parts. Academ. Verlagsges., Frankfurt am Main 1966 ff., Aula-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1985 ff. (2nd edition). Vol. 4 Falconiformes. Aula-Verlag, Wiesbaden 1989 (2nd edition). Pp. 97-136, ISBN 3-89104-460-7 .

- Theodor Mebs and Daniel Schmidt: The birds of prey in Europe, North Africa and the Middle East. Biology, characteristics, stocks. Franckh-Kosmos Verlag GmbH & Co. KG, Stuttgart 2006. pp. 331–339, ISBN 3-440-09585-1 .

- Rudolf Ortlieb: The Black Kite . Neue Brehm Bücherei Vol. 100. Westarp Sciences Hohenwarsleben 1998, ISBN 3-89432-441-4 .

- M. Schmidt & R. Schmidt (2006): Long-standing successful mixed breed pair of black kites (Milvus migrans) and red kites (Milvus milvus) in Schleswig-Holstein . Corax 20: 165-178.

- Jochen Walz: Red and Black Kites. Flexible hunters with a penchant for socializing. Ornithological collection in the Aula publishing house. Aula Wiebelsheim 2005, ISBN 3-89104-644-8 .

- Viktor Wember: The names of the birds of Europe. Meaning of the German and scientific names. Aula-Wiebelsheim 2005. P. 62, ISBN 3-89104-678-2 .

Web links

- Milvus migrans in the endangered Red List species the IUCN 2008. Posted by: BirdLife International, 2008. Accessed January 18 of 2009.

- Factsheet from bildlife europe 2004 (PDF; 270 kB)

- Very good videos of the black kite

- ( Page no longer available , search in web archives: flight silhouette )

- Videos, photos and sound recordings of Milvus migrans in the Internet Bird Collection

- Age and gender characteristics (PDF; 4.9 MB) by J. Blasco-Zumeta and G.-M. Heinze (English)

- Black kite feathers

swell

- ^ IOC 2012 ( Memento from December 5, 2013 in the Internet Archive ).

- ↑ Orta, J., Marks, JS, Garcia, EFJ & Kirwan, GM (2016). Black kite (Milvus migrans). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, DA & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. (retrieved from http://www.hbw.com/node/52978 on October 16, 2016).

- ↑ Milvus migrans in the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species .

- ↑ a b Jeff A. Johnson et al .: Prioritizing species conservation: does the Cape Verde kite exist? (pdf, 360 kbyte)

- ↑ ITIS data sheet

- ↑ a b Orta, J. & Marks, JS (2014). Black kite (Milvus migrans). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, DA & de Juana, E. (eds.) (2014). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. (accessed from http://www.hbw.com/node/52978 on July 31, 2014).

- ↑ Mark Bonta, Robert Gosford, Dick Eussen, Nathan Ferguson, Erana Loveless, Maxwell Witwer: Intentional Fire-Spreading by “Firehawk” Raptors in Northern Australia. In: Journal of Ethnobiology . 37, 2017, pp. 700-718, doi: 10.2993 / 0278-0771-37.4.700 .

- ^ Burn, Baby, Burn: Australian Birds Steal Fire to Smoke Out Prey.

- ^ Rudolf Ortlieb: The Black Kite. P. 130 (see literature).

- ↑ M. Schweizer: Rare bird species and unusual bird observations in Switzerland in 2002. 12. Report of the Swiss Avifaunistic Commission . In: Ornithol. Obs. Volume 100, 2003, pp. 293-314.

- ^ Schmidt & Schmidt (2006).

- ↑ Mebs & Schmidt p. 322.

- ↑ Nabu: Red List of Germany's Breeding Birds .

- ^ Hans Schmid, Swiss Ornithological Institute Sempach: Mail from September 25, 2006 .

- ↑ Ortlieb p. 146; Walz p. 127.