Slovenian literature

The Slovenian literature is in the Slovenian language written literature . It begins with the Freising Monuments ( Brižinski spomeniki ) around the year 1000. The first books in Slovene were printed around 1550.

Important representatives of Slovenian literature are France Prešeren (1800–1849) and Ivan Cankar (1876–1918).

Literature in the Slovene language until 1918

Early on, the country was included in the Bavarian, then Franconian, Bohemian, and finally Habsburg spheres of power. This hampered the development of a national culture and led to the fact that people and language found support almost exclusively in the peasantry, while the development of a Slovenian bourgeoisie was delayed and the nobility and civil servants used the German language.

First scriptures

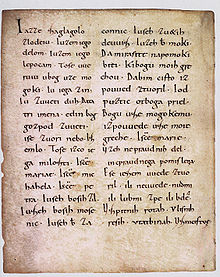

The earliest documents written in a Slovenian dialect are the Freising Monuments ( Brižinski spomeniki ), which date between 972 and 1022 and were found in Freising , Germany in 1803 . It is the oldest Slavic text written in the Latin script .

Together with the manuscript of Rateče (kept in Klagenfurt , also: Ratschacher manuscript or Klagenfurt manuscript) (cf. St. Thomas Church , Rateče / German Ratschach), the trilingual manuscript in the Venetian-Slovenian dialect from Cividale del Friuli (Čedad) (also Manoscritto de Cergneu ) with purely administrative content from the second half of the 15th century and the Sitticher manuscript (also Ljubljana manuscript; see also Sittich Monastery ) they are the oldest documents of Slovenian culture in their original form.

Folk poetry

The nature of the Slovene region encouraged the segregation of dialects. Slovenian fairy tales are often about mountain and cave spirits and dwarfs or magicians (e.g. the fairy tale by Peter Klepec ). The material for the short folk epic Pegam and Lambergar probably comes from pre-Christian times. An important figure in Slovenian folk poetry from the time of the Turkish invasions is Kralj Matjaž ( King Matthias , also Matthias Corvinus ), who was sung about in many poems of the 16th and 17th centuries.

Protestant Reformation

The pioneers and supporters of Protestantism in Slovenia were also the founders of the Slovene written language based on a Lower Krajnian dialect. The first printed books in Slovenian were the catechism in the Windish language and Abecedarium , written by the Protestant reformer Primož Trubar (1508-1586) in 1550 and printed in Tübingen , Germany. Trubar, the first superintendent of the Protestant Church in Slovenia, wrote 25 to 30 books in the Slovene language and is therefore considered the father of Slovene literature. In 1565 he had to go into exile in Tübingen. Today he is depicted on the country's two euro coin. Adam Bohorič (around 1520–1598), a pupil of Philipp Melanchthon , created a Slovenian grammar in Latin as well as Latin-German-Slovenian dictionaries for school use at the Protestant class school in Ljubljana . His student, the theologian Jurij Dalmatin (around 1547–1589) translated the Bible into Slovene. It appeared in 1584. Sebastijan Krelj , also a theologian (1538–1567), identified the local dialects of Slovene and laid down the diacritical marks for the Slovene literary language. In the second half of the 16th century, Slovenian became better known to other European languages thanks to a multilingual dictionary compiled by Hieronymus Megiser .

Counter-Reformation and Baroque

Tomaž Hren (Thomas Chrön, 1560–1630), Bishop of Ljubljana and humanistically educated protagonist of the Counter Reformation , used the Slovene language instead of Latin for sermons and church texts to spread the Counter Reformation and opened the country to cultural influences from Austria and Italy. Nevertheless, the Counter-Reformation under Ferdinand II , which began around 1600, largely destroyed the work of the Reformation linguists. The Protestant scriptures were banned. Except for the baroque preaching art of Janez Svetokriški (1647–1714), it did not produce any special achievements. The descriptions of the country and architecture of the Krajn by Johann Weichard von Valvasor (1641–1693), which he illustrated and illustrated, were written in German or Latin. It was only under Joseph II in the time of the enlightened absolutism that it was possible to study the Slovene language again, and it was not until the 19th century that Slovene literature resumed the achievements of the 16th century.

the Age of Enlightenment

The monk Marko Pohlin (1735–1801) rekindled interest in the Slovenian language and contributed to its grammatical standardization. Subsequently, the Slovenian intellectuals were influenced by the French Enlightenment and rediscovered folk poetry. Valentin Vodnik (1758–1819) wrote poems in the style of this folk poetry, Anton Tomaž Linhart (1756–1795) founded the Slovenian theater.

Romanticism (1830–1866)

Romanticism, with its emphasis on folk poetry and the national sense, developed Slovenia under the influence of the French Revolution (Slovenia belonged to France as Provinces Illyriennes from 1809 to 1814), the German Romantics and the Italian Risorgimento . The outstanding figure in this context is France Prešeren (1800–1849), who brought the vernacular to a perfect form, with the support of his mentor Matija Čop (1797–1835). However, his work was recognized late, not least because of the lack of a nationally conscious urban bourgeoisie. The romantics Janez Vesel Koseski (1798–1884), Anton Martin Slomšek (1800–1862), Stanko Vraz (1810–1851) and Josipina Turnograjska (1833–1854) as well as the leader of the nationalist Young Slovenian movement Fran Levstik (1831 –1887), who broke away from the old Slovenian Enlightenment movement. The novelist Josip Stritar (1836–1923), who lives in Vienna , followed up on European literature and was the first to appreciate Prešeren's work.

Realism (1866-1910)

The first Slovenian novel by Josip Jurčič (1844–1881), Desiti brat, stands on the threshold from romanticism to realism. Thematically influenced by Walter Scott , he is characterized by a realistic design of the characters. Janko Kersnik (1852–1897) followed up on this in stories and novels. Ivan Tavčar (1851–1923) described the life of mountain farmers before the First World War and the events of the Slovenian Reformation. The naturalistic French novel influenced the works of Zofka Kveder and Fran Govekar . Fran Saleški Finžgar continued the realistic tradition from the turn of the century until the 1950s.

In 1867 the first drama performance in the Slovene language took place in Ljubljana.

Early modernism (1890–1918)

Ivan Cankar (1876–1918) founded modern, lyrical Slovene prose under the influence of Viennese symbolism, while Oton Župančič (1878–1949) founded modern Slovene verse in free rhythms. The poets Josip Murn Aleksandrov (1879–1901) and Dragotinkette (1876–1899), who were also influenced by the Viennese fin de siècle , died early.

Slovenian literature during the time it was part of the Yugoslav state

The literature of this phase was influenced by strong social, political and ethnic tensions in the young Yugoslav state even before the German occupation in 1941. Many authors were also politically active or were so active in the resistance against the German occupation.

1919-1945

After the First World War, the influence of Expressionism became noticeable, for example in the works of Edvard Kocbek . Srečko Kosovel became known as an impressionist, later constructivist lyricist in the 1920s. France Bevk was one of the authors of the Slovenian minority in the Italian-occupied part of Slovenia who described their difficult situation.

In the 1930s, literary topics shifted to the social realm. Vladimir Bartol was best known for his novel Alamut (1938), which was also dramatized. The narrator and novelist Juš Kozak initially leaned toward expressionism, but then became a spokesman for social realism in Slovenia. Prežihov Voranc was one of this tendency, which should not be confused with socialist realism . Voranc, an important narrator of the 1930s, a member of the Communist Party and active in the partisan struggle against the German occupiers, continued his work after the war. He shares these experiences with the novelist Miško Kranjec . Matej Bor was the most important poet of the partisan struggle against the German occupiers. The neo-romantic lyric poet Fran Alb nearly and his wife Vera Alb 180 were deported to German concentration camps, but survived the world war.

the post war period

The immediate post-war period was characterized by the processing of events and a. by Edvard Kocbek, Matej Bor, Miško Kranjec ( Song of the Mountains , 1946) and Ivan Potrč . This process lasted until the 1980s, which is also reflected in the work of the Slovenian author Boris Pahor, who lives in Italy .

As early as 1948, the cultural and political climate was getting worse. In 1951 the left-wing Catholic Kocbek came into conflict with the regime and was dismissed as minister of culture. He was supported u. a. from the temporarily imprisoned Žarko Petan , who reflected on the past in his works in the 1990s. In the same year the younger authors gathered around the Beseda newspaper , with one group continuing the tradition of portraying the average fates of social realism and developing it towards socialist realism, while another tended to more intense psychological penetration and stylistic experimentation. The neo-realists and representatives of socialist realism included Ivan Potrč, Ciril Kosmač , Tone Seliškar , Anton Ingolič , Branka Jurca , Berta Golob , Ela Peroci , Kristina Brenkova and Leopold Suhodolčan . The other group came to be known as the Slovenian Intimism Movement . There were violent conflicts between representatives of both groups.

The avant-garde from 1957

After the Ljubljana Writers' Congress in 1952, a cautious thaw set in. The proponents of intimism have dared bold stylistic and semantic experiments since 1953. Among the authors standing in the modernist tradition are Vitomil Zupan , who was first imprisoned in a German concentration camp, later in a Yugoslav prison after a show trial and who wrote under a pseudonym after his release in 1955; also the radical avant-garde Rudi Šeligo (member of the movement of the Critical Generation from 1957 and for a short time Slovenian Minister of Culture in 2000), furthermore the Christian existentialist Andrej Capuder , Svetlana Makarovič , Jože Snoj and Jože Javoršek . The existentialist and playwright Dominik Smole , who worked at the then Europe-wide known theater in Ljubljana (today: National Slovenian Drama Theater / SNG Drama Ljubljana), and the playwright and lyricist Dane Zajc belonged to other members of the experimental theater Oder 57 (stage 57) and the Revija 57 magazine is also one of the representatives of the (regime) critical generation from 1957. Marjan Rožanc , who also came into conflict with the regime, the Trieste-born writer and playwright Miroslav Košuta , who mediated between the literary positions and should also be mentioned Gregor Strniša .

1975-1990

Since the late 1970s, the Stalinist epoch in Slovenia with its show trials has been dealt with in literature, especially in the form of memoirs by V. Zupan, I. Torkar, B. Hofmann, J. Snoj and Peter Božič , who went into politics after 1990 .

Svetlana Makarovič (* 1939) emerged as an extremely productive poet, writer, actress, radio play author and children's book author in the 1970s and 1980s. She illustrated her children's books herself and also wrote puppet shows. She continued her work after 1990, where, as before 1990, she took controversial positions on social issues.

The poet and dramaturge Boris A. Novak , Evald Flisar and Tomaž Šalamun , who temporarily emigrated to the USA in the 1970s , are considered to be representatives of a postmodernism that freely disposes of the traditions of the past .

The period of independence since 1991

Slovenian literature flourished after it had previously been largely neglected under the label of "Yugoslav literature" and quickly became known abroad. Nevertheless, many writers work in scientific, teaching or journalistic professions at the same time, as the literary market is very tight and the sometimes avant-garde poetry often only reaches a limited readership. In Japan and the USA, for example, Some of the time before independence Iztok Osojnik , who also publishes in English.

The politically active Drago Jančar (* 1948), who was imprisoned in 1974 for his reports of atrocities after the end of the war, worked on his experiences immediately after 1990 in partly satirical form. Today he is probably the best-known Slovenian author ( Secret of a Winter Night , German 2015). One of the dissidents was Boris A. Novak , who was born in Serbia in 1953, writes in the Slovene language and also writes for children.

Younger authors include the poet and essayist Aleš Debeljak , the novel and screenwriter Miha Mazzini (* 1961), Sebastijan Pregelj ( On the Terrace of the Tower of Babel , 2013; Under a Lucky Star , 2015), Igor Škamperle , who also published as a scientist on culture and art of the Renaissance, the microbiologist and poet Alojz Ihan , the poet and anthropologist Taja Kramberger , Aleš Šteger , whose poems have been translated into many languages, also the poet and essayist Uroš Zupan (* 1963), the narrator and Screenwriter Nejc Gazvoda (* 1985), Andrej Blatnik ( The Day Tito Died , 2005), Jani Virk ( Pogled na Tycho Brache , 1998), Brane Mozetič (* 1953), Goran Vojnović , who is known for his homoerotic poems and translations (* 1980) ( Yugoslavia, my country , 2014), the convinced Catholic Vinko Ošlak , who had temporarily emigrated to Austria, and the journalist Benka Pulko , who got reports about her trips around the world was nnt. The Bosnian Josip Osti recently published in the Slovenian language.

The most important Slovenian literary and art prize is the Velika Prešernova nagrada (Great Art Prize of the Prešeren Foundation).

Slovenian authors in Carinthia, Italy and in emigration

Slovenian-speaking authors, publishers and cultural institutions are also active in Carinthia and Italy, who have contributed to making Slovenian literature better known in Europe. This counts or counted

- in Trieste Boris Pahor , Alojz Rebula , and Marko Kravos, who was born in the southern Italian exile of his parents . Dušan Jelinčič , who became known as a mountaineer, writes in Italian .

- in Carinthia Florjan Lipuš , who describes the end of the idyllic village, furthermore Janko Ferk , Cvetka Lipuš , Janko Messner and Gustav Januš , whose artistic poems have been translated by Peter Handke . Tomaž Ogris published one of the rare and therefore all the more important dialect books in the Radsberg dialect . Bojan-Ilija Schnabl writes Slovenian prose and poetry, which finds its linguistic and mythological roots in the Klagenfurt field and in the municipality of Magdalensberg .

Louis Adamic , who emigrated to the USA in 1913, toured Slovenia in the 1930s and published critical travel reports about the Yugoslav royal dictatorship in English.

The author Lojze Kovačič was born as the child of Slovenian migrants in Basel and died in Ljubljana in 2004. Brina Svit emigrated to Paris in 1980.

literature

- Erwin Köstler : From the cultureless people to the European avant-garde. Main lines of translation, presentation and reception of Slovenian literature in German-speaking countries. Interactions Volume 9. Bern; Berlin ; Bruxelles; Frankfurt am Main ; New York ; Oxford; Vienna: Lang, 2006. ISBN 3-03910-778-X

- Anton Slodnjak : History of Slovenian Literature . Berlin: Walter de Gruyter 1958

- Alois Schmaus (continued by Klaus Detlef Olof): The Slovene Literature , in: Kindlers Neues Literatur-Lexikon, Ed. Walter Jens, Vol. 20. S. 455 ff., Munich 1996

See also

References and footnotes

- ↑ kodeks.uni-bamberg.de

- ↑ ng-slo.si: Slovenska moderna ( memento of the original from October 26, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ gorenjskiglas.si: Je človek še Sejalec ( Memento of the original of February 8, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and not yet checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ krajev in obcine / rokopis-f.htm Celovški rokopis iz Rateč ( page no longer available , search in web archives ) Info: The link was automatically marked as defective. Please check the link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ kodeks.uni-bamberg.de ; see. fabian.sub.uni-goettingen.de , theeuropeanlibrary.org , nuk.uni-lj.si: Stična Manuscript ( Memento of the original from May 24, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. & wieninternational.at ( Memento of the original from May 17, 2013 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice. , dialnet.unirioja.es

- ↑ ach.si , nuk.uni-lj.si: The Birth Certificate of Slovene Culture - Exhibits ( Memento of the original dated February 12, 2012 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ The tournament between the two knights Lamberg and Pegam: A Carniolan folk song with a German translation by JA Suppantschitsch, Egersche Schriften, 1807

- ↑ Branco Bercic, Treatises on the Slovenian Reformation. Literature - History - Language - Style - Music - Lexicography - Theology - Bibliography. History, Culture and Spiritual World of the Slovenes, Vol. 1 , welcomed by Rudolf Trofenik . Trofenik publishing house, Munich 1968

- ^ A. Schmaus, Die Slovakische Literatur , p. 456

- ↑ A. Schmaus, Die Slovakische Literatur , pp. 456 f.

- ↑ A. Schmaus, Die Slovakische Literatur , pp. 457 f.

- ^ German translation: Alamut. A novel from the ancient Orient , Lübbe Verlag

- ↑ In 2014 the spoken Slovenian dialect from Radsberg, which is included in the dialect of the Klagenfurt field , was published in its current form in dialectal episodes and cheerful village stories by Tomaž Ogris in book form and on CD-ROM in the book Vamprat pa Hana .

- ↑ Tomaž Ogris: Vamprat pa Hana, Domislice, čenče, šale, laži . Klagenfurt / Celovec, Drava Verlag 2014, ISBN 978-3-85435-748-3 .

- ↑ Book cover: Archived copy ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.

- ↑ Bojan-Ilija Schnabl: Magnolija in tulipani, Pripovedi in resnične pravljice s Celovškega polja . Celovec: Drava Verlag , 2014, 72 pages, ISBN 978-3-85435-740-7 , www.drava.at

- ↑ Book cover Magnolija in tulipani: Archived copy ( Memento of the original from March 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link was inserted automatically and has not yet been checked. Please check the original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this notice.