Unpunished Nazi justice

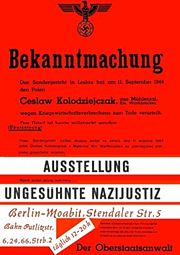

"Unpunished Nazi Justice - Documents on Nazi Justice" was the title of a touring exhibition in Germany on judicial crimes that had been committed during the Nazi era (1933–1945) in the German Reich and areas occupied by it. She showed documents on criminal proceedings and death sentences as well as on the post-war careers of judges and prosecutors involved. It was preceded by two petition campaigns at the Free University of Berlin . This was followed by the “Action Unpunished Nazi Justice”, in which criminal charges were filed against 43 reigning Nazi lawyers. The reason was the upcoming statute of limitations for a large part of the National Socialist crimes against humanity (December 31, 1959) and for manslaughter committed until 1945 (May 31, 1960).

The exhibition was shown from November 27, 1959 to February 1962 in ten German and some foreign university cities, first in Karlsruhe , the seat of the Federal Supreme Court and the Federal Constitutional Court , then in West Berlin , Stuttgart , Frankfurt am Main , Hamburg , Tübingen , Freiburg , Heidelberg , Göttingen , Munich , Oxford , London , Amsterdam , Utrecht and Leiden . The main author was the West Berlin student Reinhard Strecker , the organizers were local student groups, mostly members of the Socialist German Student Union (SDS). Although the exhibition was financed only from private donations, used the simplest means of representation, could often only take place in private rooms and was rejected by almost all German parties and media, it had considerable public effects.

prehistory

The first federal government under Konrad Adenauer pursued a policy of re-integrating Nazi perpetrators, tried to reverse certain measures taken by the Allies against them, and in 1949 helped convicted Nazi criminals to a generously managed partial amnesty . Since 1951, the law regulating the legal relationships of persons falling under Article 131 of the Basic Law has made it possible for more than 55,000 Nazi officials who had lost their employment and pension entitlements as a result of denazification to return to the civil service.

The GDR government has intensified its attacks since rearmament and the accession of the Federal Republic to NATO in 1954, the Federal Republic stands in direct continuity with Nazi fascism . To this end, she founded a “Committee for German Unity” (ADE) under Albert Norden . Since 1956 he has published brochures documenting West German anti-Semitism and the post-war careers of former National Socialists. The first pamphlet Nazi judges in the Bonn service claimed that 80 percent of the senior German judicial officers were pillars of Adolf Hitler's dictatorship . To this end, she named among other things 39 names of judges and public prosecutors who were recorded in war crimes files from the Netherlands , Poland and Czechoslovakia . She compared their offices in the Nazi era with their current offices. With this, the ADE began a multi-year “ blood judge ” campaign, from which in 1965 a comprehensive “ brown book on war and Nazi criminals in high positions in the Federal Republic and West Berlin ” emerged. The brochure of May 23, 1957 Yesterday Hitler's Blood Judge - Today Bonner Judicial Elite listed death sentences, their reasons, the names and dates of execution of the victims, the names and past and current offices of the perpetrators. The material came from files of the Reich Ministry of Justice , the People's Court, and the Upper Reich Attorney General and special courts of the Nazi era. By 1960, the ADE had published eight more such brochures with the names of more than 1,000 lawyers from the Nazi era.

Because of the anti-communism prevailing during the Cold War , the West German judiciary, politics and the media initially paid little attention to the GDR brochures. Federal Minister of Justice Hans-Joachim von Merkatz strictly refused to initiate investigations against the aforementioned lawyers because of their origin. In July 1957, he forbade the official Ernst Kanter , who was responsible for inquiries about Nazi justice , to ask whether the state justice administrations were investigating the allegations. Most federal states only asked the suspected persons for a non-binding statement, which they often refused. The state governments then agreed not to seek criminal investigations and only to initiate occasional disciplinary proceedings in the event of public inquiries. They did not consider transferring or resigning the incriminated.

In November 1957, the GDR brochures also appeared in Great Britain . Because he feared submissions from British parliamentarians, Federal Foreign Minister Heinrich von Brentano demanded a reaction from Federal Justice Minister Fritz Schäffer to the allegations. His brief references to the rule of law in the Federal Republic reinforced the impression abroad that the Federal Government wanted to sit out the necessary proceedings. By March 1958, twenty British MPs had asked their own government about this; many British citizens also complained. The British tabloids used the subject for sensational articles. On the advice of his official Karl Heinrich Knappstein , Schäffer claimed to Brentano that an internal personnel check had revealed the ADE's "baselessness of the suspicions". All responsible German politicians followed this line. After the first critical press reports, also in Germany, the Justice Ministers' Conference agreed in November 1958 that former Nazi lawyers should only be examined in the event of “specific allegations”. The Lower Saxony Minister of Justice Werner Hofmeister claimed that the Nazi special judges were all only “slightly burdened” and that they had a non-revisable “secured legal position” due to denazification. Two state justice ministers wanted to protect the "victims" from further allegations by transferring them. The conference decided to set up a central office of the state judicial administrations for the investigation of National Socialist crimes . The federal government gave the wrong impression to other countries that this agency was also responsible for prosecuting former Nazi judges. The German Association of Judges expressed solidarity shortly thereafter with all as a "hanging judge" attacked lawyers and complained that they were defamed.

In January 1959, Adolf Arndt found that the Bundestag had judgments that were too mild for the opposition SPD in German Nazi trials , but did not ask whether this could have anything to do with the reinstatement of former Nazi lawyers. He avoided morally condemning them and demanded that the "targeted collective defamation" of the GDR no longer be observed. The self-governing organs of the Federal German judiciary were supposed to ensure that judges with previous charges would no longer be used in Nazi trials. Only individual SPD members of the state parliament, such as Fritz Helmstädter in Baden-Württemberg, demanded that former Nazi lawyers in the civil service be investigated quickly and vigorously.

At that time, the previous West German policy towards the past reached its limits. Since the scandal surrounding the Nazi lawyer and head of the Chancellery, Hans Globke , earlier crimes by Nazi perpetrators who were still employed have been publicly debated instead of just their reinstatement and pensions. From October 1959, there was a nationwide series of anti-Semitic attacks on synagogues and Jewish cemeteries , which received a great deal of attention at home and abroad. In this context, the film " Roses for the Public Prosecutor " and the exhibition "Unpunished Nazi Justice" were a turning point: from then on, the German public was more concerned with the problem of former Nazi perpetrators in state offices than with the intentions of the GDR.

Emergence

The 29-year-old linguistics student Reinhard Strecker ( Freie Universität Berlin ; FU) became aware of the GDR campaign against Nazi lawyers in 1958 and wanted the information in the ADE brochure “We are accusing: 800 Nazi blood judges. Supporting the Adenauer Regime ”(February 1959) through own research. Because he was outraged by the dissolution of the GDR allegations, he decided to create a documentation of the crimes of incumbent Nazi lawyers himself, independent of propaganda material. Federal German judicial authorities did not allow him to inspect files, and a regional court refused them. Therefore, he then turned to Czechoslovakia, which also denied him access to the original files and referred him to the ADE in East Berlin for research . Although Strecker was known to the GDR authorities as an anti-communist and refugee helper, ADE director Adolf Deter supported his project and allowed him to look into selected original documents. After looking through around 3,000 files that the ADE had compiled from German and Eastern European archives, Strecker concluded that they were genuine and that the ADE allegations were justified, apart from a few simplifications.

In the course of the research, the idea of an exhibition arose. In support of this, the FU's student convention collected signatures for two petitions that asked the German Bundestag about re-officiating former Nazi judicial lawyers and former concentration camp doctors who were again working as doctors . The Association of German Student Associations (VDS) supported the petitions. With around 30 fellow students, Strecker checked around 100 court cases , the identity of the perpetrators with West German judges, set up a personal database and put together around 140 personal files. He presented this material in May 1959 in Frankfurt am Main at the SDS Congress "For Democracy - Against Militarism and Restoration ". Higher Regional Court President Curt Staff confirmed the authenticity of the documents.

At the time, the SDS was torn apart by wing battles and was on the verge of split. The federal delegates' conference of July 30, 1959, however, decided unanimously to support Strecker's exhibition. The SPD board members Waldemar von Knoeringen and Willi Eichler were present. At the suggestion of the SDS board members Monika Mitscherlich and Jürgen Seifert , the exhibition was named "Unpunished Nazi Justice". The SDS called on all student university groups to prepare parallel educational campaigns at their locations. These were intended to shake up the public and invalidate the previous construction of the justice system, according to which Nazi perpetrators had to prove “base motives” in order to be able to punish murder or manslaughter. The aim was to prosecute the former Nazi lawyers in good time, as the statute of limitations for their crimes was imminent. After that, they could only have been prosecuted under disciplinary law. In justified suspicious cases, the SDS federal executive board wanted to file criminal charges itself. The exhibition was supposed to start in Karlsruhe because the highest German courts were located there.

In a circular dated October 30, 1959, the SDS federal chairman Günter Kallauch affirmed: Since the crimes of Nazi judges would soon expire, all local SDS groups would have to help ensure that proceedings against as many of these judges as possible were initiated. With the help of the exhibition, further Nazi judges in new offices were to be found and restorative tendencies in the German judiciary were to be pointed out. To this end, prominent Social Democrats were to give lectures on the subject of “ Political Justice ”. Kallauch named Wolfgang Abendroth , Adolf Arndt, Paul Haag , Gustav Heinemann and Diether Posser as speakers . On the initiative of Wolfgang Koppel , the SDS in Karlsruhe formed an organizing committee that prepared the first exhibition with Strecker, invited the SPD party executive committee to do so on November 11, 1959 , and asked for financial aid for the exhibition.

The party executive reacted negatively and asked for more information before they could grant funds. On November 20, 1959, Adolf Arndt wrote to Koppel: An exhibition would be unsuitable for enforcing the criminal proceedings against Nazi lawyers that were certainly necessary. If the SDS had really relevant material, it would have to forward it to the “responsible” parliamentary groups, who would then arrange for the “necessary”. Even before Koppel had replied, the SPD presidium decided on November 23, 1959 to distance itself from the exhibition. In a circular, Waldemar von Knoeringen, Erich Ollenhauer and Herbert Wehner called on all SPD local associations to refrain from supporting the exhibition. The SDS federal board was asked to send such a circular to all SDS groups. As a result, Kallauch did not join the Karlsruhe Organizing Committee and did not send a representative to the exhibition opening. In a letter on November 28th (one day after the start of the exhibition), he asked all SDS groups to organize the exhibition themselves and, for “obvious reasons”, not to involve “neutral action committees”.

The background to this was the strict requirements that the SPD had imposed on the SDS since July 1959 to coordinate general political projects with the party executive and to refrain from all contact with communists . It was feared that the Karlsruhe organizing committee was working specifically with supporters of the magazine , whose exclusion from the SDS had previously been forced by the SPD. Koppel belonged to the left wing of the SDS around the former SDS chairman Oswald Hüller and had organized a study trip to the GDR. Neither he nor Hüller were Stasi employees . The party executive was convinced, however, that communists directed and financed the exhibition because many documents came from East Berlin and some SDS representatives had maintained undesirable "contacts with the East". In order to prevent a continuation of the exhibition at other university locations and a broad public debate about Nazi perpetrators in the federal German civil service, the SPD executive board excluded the Karlsruhe exhibition organizers from the SPD. In the opinion of the SPD, after the Berlin crisis of the previous year and the resolution of the Godesberg program (November 15, 1959), their tolerance would have jeopardized their opening up to the bourgeois electorate.

execution

On November 27, 1959, the exhibition was opened in the Karlsruhe city hall. Several local SPD associations had supported them and donated DM 300 in advance . The following day, the magistrate learned of the circular from the SPD presidium, forbade the organizers to continue using the town hall and forced them to move at short notice. From November 28 to 30, the exhibition took place during the day in the “Krokodil” bar, which was close to the Federal Prosecutor's Office . Wolfgang Koppel had rented the restaurant with the donations and agreed the opening with Strecker. The EKD representative Martin Niemöller and the social scientist Wolfgang Abendroth were intended as public supporters . The first keynote speaker, lawyer Dieter Ralle, is said to have equated Hans Globke with the "henchmen of Auschwitz ". This is what the People's League for Peace and Freedom founded by former National Socialists reported to the Federal Chancellery in its report of December 3, 1959.

At a press conference, Strecker and Koppel announced that they would file criminal charges against incumbent judges and public prosecutors for perverting the law in unity with manslaughter or aiding and abetting manslaughter. Unlike the ADE, Strecker argued not against the state of the Federal Republic of Germany, but for the principles of the rule of law: According to this, the judicial office should only be entrusted to those persons who are capable and worthy of it. This was often disregarded, but those responsible did not want to see their mistakes and correct them. That is the only reason why the students should point out this problem. Every citizen is jointly responsible for maintaining and expanding the rule of law, without the “misdeeds of others” being allowed to induce “self-righteousness”. Former Nazi perpetrators were not only taken over into the federal German judiciary, but also into administration, business, education and journalism. The "whole ideology of the brown epoch lives on." It is not about blaming, but about "mastering the political fate of our country better this time than 30 years ago". The exhibitors contradicted the widespread demonization of the Nazi dictatorship, which attributed it to a seductive power of Hitler. However, they did not fundamentally question the figure of thought of the “excess offender”, according to which only particularly arbitrary judgments of individual Nazi judges should be punished.

Koppel's exhibition catalog stated the intention of the exhibition: “Where supporters of National Socialism are tolerated, protected and cherished, there the old spirit finds justification and at the same time an opportunity to undermine the democratic state order. It is therefore crucial that Nazi judges officiate and that this fact is accepted as unobjectionable by those around them. ”Accordingly, the authors primarily wanted to attack this tolerance and make people aware that the return of National Socialists to offices and authorities was morally intolerable. In order to delegitimize the previous policy, which legitimized Nazi crimes through the integration of Nazi perpetrators, they first had to create a public that disrupted this tolerance. That's why they chose a scandalous language.

First 100 documented cases were presented. They concerned 206 lawyers who were involved in unjust judgments. Due to the lack of funds on the part of the student initiators, the exhibition consisted only of photocopies of special court judgments, judicial and personal files, which were simply summarized in loose-leaf binders and were often of poor optical quality. Only handwritten posters served as an explanation. It was not the presentation that was spectacular, but the content: lists of names showed the previous activities of judicial lawyers in the Nazi judicature, documented the death sentences passed with their participation and revealed the current activities of those affected in the West German judiciary. Among other things, there were judicial files from the Prague Special Court . Lawyers who had previously worked there, such as Judge Johann Dannegger , District Court Judge Walter Eisele and Judge Kurt Bellmann, were again active in German courts. The former judge Erwin Albrecht had become a member of the Saarland state parliament . The unjust character of the judgments should be made understandable for the visitors of the exhibition on the basis of the copies of the procedural protocols.

As announced, on January 18, Koppel and Strecker filed criminal charges against 43 former judges of Nazi special courts. Before that, they had written letters describing at least one such case to the competent public prosecutor's offices throughout Germany. Thus they fulfilled the SDS board resolution of 1959, which had asked all members to bring criminal proceedings against former Nazi lawyers in good time before the statute of limitations . Deprivation of liberty through unlawful prison sentences had been statute-barred since 1950; only the facts of manslaughter, deprivation of liberty resulting in death and murder by unlawful death sentences could still be prosecuted and only proven by perversion of the law. Since a BGH judgment in 1956, defendants had to be proven that they had deliberately and knowingly made illegal verdicts.

Because of the massive preventive attempts in Karlsruhe, Strecker founded a board of trustees for the following station in West Berlin (here the exhibition was shown from Tuesday, February 23, 1960 to March 7, 1960 in the Springer Gallery on Kurfürstendamm), which many recognized personalities joined , including Professors Margherita von Brentano , Helmut Gollwitzer , Wilhelm Weischedel , Ossip K. Flechtheim , the writers Axel Eggebrecht , Günter Grass and Wolfdietrich Schnurre , the chairman of the Jewish community Heinz Galinski , Probst Heinrich Grüber , the publisher Axel Springer and others. They took sides in the media for the exhibition and pushed back allegations against the SDS students. In addition, other university groups contributed to the exhibition, including German-Israeli study groups , Evangelical student community and Liberal Student Union of Germany . As early as 1958, they jointly supported the Fight against Nuclear Death movement. Nevertheless, since January 1960 the German media have always presented the exhibition as a single action by Strecker and named it after him.

In February 1960, the West Berlin Senate ordered the local universities to ban the exhibition on their premises. The project is an “act of public agitation in favor of Soviet zonal agencies” in order to damage the “reputation of the judiciary as a pillar of public order”. All accused members of the West Berlin judiciary have already been checked. The organizers have not yet followed the request to hand over their documents. When the art dealer Rudolf Springer offered the students his gallery on Kurfürstendamm for the exhibition, the Senate asked the house owner to prohibit this and to terminate the gallery's lease. The event stabbed the Governing Mayor Willy Brandt ( SPD ) in the back at a politically difficult time. After some British newspapers reported critically about the Senate's proceedings and the exhibition in the gallery had opened, the Senate asked the West Berlin teachers not to visit them.

As early as March 2, 1960, before the end of the West Berlin exhibition, the Labor Oxford Club at Corpus Christi College (Oxford) showed a selection of Strecker's material on 22 Nazi judges. One of the initiators was the later Holocaust researcher Martin Gilbert . You had visited Poland and Auschwitz in a study exchange in 1959 and then agreed to work with Strecker. The British weekly New Statesman reported on this and contradicted German allegations of forgery: Strecker's documents could be verified at any time by duplicates in the possession of the US government . Strecker carefully differentiated between ordinary criminal justice and death sentences, which Nazi judges could have avoided even under Nazi laws. Furthermore, he had shown the ADE to be mistaken. The Federal German authorities could not have proven any inaccuracies in his presentation, but prevented all attempts to corroborate the East Berlin evidence from Western sources. With letters to the editor to the London Times , the British students got the House of Commons to consider having the East Berlin documents examined for themselves. The federal government had refused. The Labor -Abgeordneten Barbara Castle and Sydney Silverman founded a Allparteienkomitee, the English translations of the exhibition documents in the House of Commons presented. In April 1960, the House of Commons invited Strecker to explain the continuity of personnel in the German judiciary and the unwillingness to come to terms with Nazi crimes in the Federal Republic of Germany. British MPs called on their government to put pressure on the federal government in view of the facts presented and to demand the dismissal of the former Nazi lawyers.

In Tübingen and Freiburg in particular, the exhibition met with enormous rejection from the Ministers of Education and Justice, the German Association of Judges, university management and student opponents of the SDS. In order to get room promises, the organizers called the exhibition in Tübingen Documents on the Nazi Justice , in Freiburg documents of totalitarian justice . They also removed politically explosive elements and added new elements. In Munich the exhibition began on February 10, 1961. The police forbade advertising because the posters allegedly did not make the reference to the Nazi era clear enough. Only with an addition was it allowed to continue posting. In Hamburg, where the exhibition was hosted from May 29 to June 9, 1961, posters for it initially had the title subheading “Can judges be murderers?” And a list of names on which the names of acting Hamburg NS judges were underlined. Hamburg courts banned this poster version and only allowed a version without a title or name.

Until 1962, the exhibition was shown in ten German university cities despite attempts to obstruct or prevent them. British and Dutch student groups also organized their own exhibitions in Oxford, Leiden, Amsterdam and Utrecht. Regional and national newspapers in East and West Germany, the USA, Great Britain and Switzerland reported on it.

effect

Federal and state politicians of all parties viewed the exhibition as breaking a taboo and fought against it violently. They rejected the allegations against the judges unchecked, claimed that the material was falsified and that the students carried out GDR propaganda. They saw the adoption and publication of documents from East Berlin, even mere photocopies, as a serious breach of the norm. The federal government had the exhibition organizers monitored by the Office for the Protection of the Constitution , who asked their friends and relatives about their private lives and financial situation. Baden-Württemberg's State Minister of Justice, Wolfgang Haußmann, accused the organizers of treason . Most of the media commented similarly. The conservative newspaper Badische Latest Nachrichten, for example, described them as the “stooge of the rulers of Pankow ”. Strecker and his family received many anonymous threats, and Strecker's apartment was broken into. Only two newspapers (Badisches Volksblatt, Tat) reported in detail on the contents and objectives of the exhibition.

Adolf Arndt (SPD) received exhibition material from the organizers in November 1959 and had to admit that it contained “seriously real documents”. He passed it on to the legal committee of the German Bundestag , to which he himself belonged, in order to steer the handling of it in parliamentary and non-public channels. In public he maintained his general suspicion, even after a long conversation with Strecker about his sources. In April 1960 in an article for the student magazine Colloqium he repeated: “It is not clear who organized the exhibition, who would speak and who raised the considerable funds for it”.

At the beginning of January 1960, Attorney General Max Güde Strecker invited him to his office, had the exhibition material shown for several hours and then publicly stated: "I have seen judgments under the material that I consider to be genuine, photocopies, I believe of real, real judgments, I've seen judgments that shocked me. ”This gave the exhibition credibility and forced further political responses. Haussmann now also stated that most of the photocopies sent from East Berlin were "not forgeries"; follow up on this material. He agreed to initiate proceedings if the documents were sufficient or to “not re-use the data concerned”. Baden-Württemberg's state parliament founded a commission made up of two higher regional court presidents and a criminal law professor to review 66 former Nazi judges and prosecutors, four of them from the People's Court, and 23 former judges-martial officials in the state's judicial service. Investigations have been initiated against several judges and officials of the higher judicial service in Baden-Württemberg . At the same time, Haussmann justified the perpetrators: No civil servant or judge had withheld any previous activity at Nazi courts. Even death sentences from war courts and special courts are valid as long as the laws in force at the time cover them. Judges could not be accused of applying the then legally prescribed punishment. He recalled the special tribunal proceedings for judges and prosecutors, but did not mention that their personal files had not contained copies or originals of their judgments, as the exhibition showed.

Güde then emphasized in a television interview: The judgments of judges at special courts should be examined on a case-by-case basis. You could not have refused the service, but could have exhausted legal discretion. “Many of the death sentences need not have been passed. They should not have been issued, even on the basis of the laws according to which they were made. ”In no case known to him, a judge was harmed in life and limb because of too mild sentences. Güde thus removed the basis for the justifications customary at the time. Then West German journalists confronted Haußmann with earlier death sentences of Baden-Württemberg officials for the most minor offenses, such as " Degradation of military strength through simple criticism of the Hitler regime, for not reporting fugitive prisoners of war, for refusing to show ID, for injuring a customs dog and for delivering laundry the brother wanted by the Gestapo . ”The magazine Der Spiegel described in particular the death sentences of Walter Eisele in detail and cited pages from excerpts from the court judgments of the former Nazi judges.

West Berlin's Justice Senator Valentin Kielinger had initiated investigations against five judges and two public prosecutors by December 22, 1959. Four West Berlin judges who had worked on death sentences had prematurely retired . The state governments of Hesse , Hamburg and North Rhine-Westphalia tried in confidential negotiations to force the incriminated judicial officers out of service. In spite of this, only 16 former judges or public prosecutors retired early in 1961, while around 70 severely incriminated persons remained in office nationwide. The legal advisor of the SPD Adolf Arndt now described the chosen "quiet path" as a mistake and admitted that the exclusion from the party by the Karlsruhe exhibition organizers was wrong. In the Judges Act of 1961, §116 was inserted, which enabled incriminated judges to take early retirement at their own request with full pay. By the end of the application period (June 30, 1962), 149 judges and public prosecutors had claimed this rule. A bill for the compulsory retirement of the remaining Nazi lawyers would have required an amendment to the Basic Law , for which no two-thirds majority could be found in the Bundestag .

Nevertheless, the exhibition intensified the discussion about legal positivism and judicial office. Judges should no longer be just legal technicians , but, unlike in the Weimar Republic , should be trained and obliged to maintain the democratic order. In 1960, the German Association of Judges set up a commission that drew up recommendations for a major judicial reform in order to strengthen the authority of the judiciary and to train "suitable personalities" for it. The commission did not deal with the exclusion of former Nazi judges, especially those who had passed death sentences, in order not to anticipate the enactment of a German judicial law that had been in preparation since around 1955.

Before Strecker and Koppels reported criminal charges on behalf of the SDS, only a few Nazi victims reported former Nazi judges; the media had hardly noticed this. The SDS action meant that from then on, larger victim associations such as the Association of Victims of the Nazi Regime - Association of Antifascists and the Czechoslovak Association of Antifascist Fighters filed collective reports with specific allegations.

The Hessian attorney general Fritz Bauer , a survivor of the Holocaust , took up the title and subject of the exhibition in his essay "Unpunished Nazi Justice" (1960) in the journal Neue Gesellschaft . In it he explained the personal continuities and the non-prosecution of Nazi crimes from the same "spirit from which the (Nazi) unjust state arose". The non-involvement with Nazi perpetrators who are still employed shows a “chronic disposition” in Germany for this spirit. It stands for an unresolved past , present and future. Bauer used exhibition documents as a case study for blatant injustice judgments and inadequate legal figures to punish them. He doubted that “ atonement ” would be a sensible criminal law goal, since it presupposed the perpetrator's insight and this could not be expected from Nazi judges any more than from ordinary criminals. You would always excuse yourself with fateful circumstances, entanglement and doom. Bauer described the legal obstacles to lifting the statute of limitations through timely indictments: It is very unlikely that the Nazi judges could be proven to have "low motives" as the murder criterion. In addition, most of the judges were trained during the Nazi era, so they practically sit in court over themselves.

Nonetheless, on February 17, 1960, Bauer received the order from the Hesse Ministry of Justice to systematically examine all judgments of the Hessian special courts (around 5,470 in total). On March 21, he sent the report to the Hessian Ministry of Justice with the request to evaluate above all "excessive" death sentences in good time before the statute of limitations. The ministry said it had examined 67 cases but found no death sentences in them that required criminal or disciplinary action. By then, it had opened five preliminary investigations, including one judge and one retiring. Bauer had to discontinue the three remaining proceedings because deliberate infraction of the law could not be proven. By June 3, 1960, the number of suspected cases in Hesse rose to 159. Since the Eastern European files were still largely unevaluated, the justice ministers of the federal states expected numerous further criminal charges from the victims' associations.

Although the federal government had advised that the statute of limitations should be interrupted for all related criminal complaints, the state justice ministers ruled out their own investigations in Eastern Europe and limited themselves to general administrative assistance requests. Only Fritz Bauer applied on May 5, 1960, to initiate preliminary proceedings against 99 Hessian lawyers. He was awaiting further evidence of unjust judgments, which the Polish and Czech authorities had pointed out to him in his preparation for the Auschwitz trials. On May 8, 1960, manslaughter became statute-barred because the Bundestag majority had rejected an SPD motion to extend the deadline. A variety of Nazi crimes were characterized with a de facto - amnesty withdrawn at any prosecution. In mid-May 1960, the other attorneys general of the federal states rejected Bauer's urgent advice to set up a special conference on the problem of Nazi lawyers. On June 2, 1960, the Hessian state parliament debated the issue. It turned out that the Hessian Ministry of Justice had begun a survey of the incriminated lawyers proposed by Bauer in 1959 and had written to 72 former Nazi lawyers. The opposition parties strongly opposed this and wanted to postpone the debate until the limitation period (June 30, 1960) expired. They did not want to recognize the activity at a war or special court of the Nazi era or the lists of names of the ADE or the SDS criminal charges as a reason to interrupt the statute of limitations for these persons. Nevertheless, the legal committee decided these reasons for recognition with a narrow majority. However, criminal proceedings continued to be initiated at most as a result of criminal charges against these persons. Bauer's efforts to prosecute Nazi crimes were largely unsuccessful, while the number of Nazi perpetrators exposed in the German civil service increased steadily. Only in 1965, the Bundestag extended the limitation period for murder during the Nazi era just in time. But in West Germany not a single judge of the People's Court, the special courts and other Nazi courts was convicted after 1945.

Before 1959, only smaller, largely neglected exhibitions on the Nazi theme had taken place. The exhibitions “Unatunited Nazi Justice” and “The Past Warns” (1960–1962) met with greater publicity and marked a change in the culture of remembrance in dealing with the Nazi era, which initiated the West German student movement in the 1960s .

For the first time, the exhibition drew attention to some of the failings of the Federal German judiciary, but failed to achieve its goals: none of the more than 100 Nazi lawyers uncovered were charged. It favored the relieving fallacy that the SDS project "essentially unmasked the 'black sheep'". It did not show the full extent of the takeover of Nazi lawyers in Federal German offices: since 1949, the judicial apparatus of the Nazi era had been almost completely restored. 34,000 German lawyers, 8,000 of them throughout, remained in judicial offices between 1933 and 1965. In 1954, 74 percent of lawyers at local courts, 68 percent at regional courts, 88 percent at higher regional courts and 75 percent at the BGH were already active as lawyers during the Nazi era.

The exhibition showed only rudimentarily that and how the former Nazi judges conducted a case law in their own right and also hardly or not at all punished other Nazi criminals. Your criticism did not change the judgment practice of German courts. These hardly ever accused Nazi criminals, they mostly acquitted the others, played down their crimes as aids, justified the worst injustice through formal legality and thus reinterpreted the Nazi regime for decades as a constitutional state. As a result, only 6,494 of hundreds of thousands of Nazi criminals were punished by 1998; far more than 150,000 murderers from the Nazi era were never investigated. Only in 1999 did the Bundestag retroactively deny the legal validity of the unjust judgments of the Nazi regime.

research

The exhibition stimulated research on Nazi justice and its continuity. In 1963, Wolfgang Koppel published the catalog “Justiz im Zwielicht”, which represented the contribution of the Nazi judiciary to the Nazi crimes and set up the Federal German courts where former Nazi judges were active at the time. This contradicted the common narrative that only sadistic excess criminals from the ranks of the SS had committed the Nazi crimes. Ingo Müller's groundbreaking work Terrible Jurists (1987) used exhibition documents as evidence for case studies. Norbert Frei described Strecker's achievements in his work Careers in Twilight (2001). Annette Weinke described the contemporary impact of the exhibition: It caused a delayed change in public opinion about Nazi perpetrators in the civil service.

The historian Stephan Alexander Glienke stated in 2005 that it was only the reactions abroad, especially in Great Britain and the GDR, that had given the exhibition a wider impact. In his dissertation (2008), Glienke showed the impetus the exhibition gave: It was Güdes' interview that gave the exhibitors unexpected publicity and the legal argument for their criminal charges against Nazi lawyers. For the first time, the FU curtailed some of its students' freedom of expression . This triggered a wave of solidarity from several student committees and university associations and a test of strength between the SDS and SPD, which intensified their conflict and in 1961 led to the SDS being excluded from the SPD. The attempts by the West Berlin Senate to prevent it drew the attention of the British press. As a result of this, and through Strecker's contacts with British students and Labor MPs, the exhibition probably only developed the necessary pressure on the federal government, which induced it to make minimal concessions on the Nazi judge question.

Gottfried Oy and Christoph Schneider (2013) explain the propaganda and falsification allegations against the exhibitors at the time and their exclusion from the SPD from the systemic competition between the two German states. It was only Güdes advocacy that made the criminal charges possible, which forced public prosecutors and legal committees throughout Germany to investigate cases of Nazi injustice and 149 Nazi lawyers to take early retirement. The exhibition thus made an important individual contribution to clearing up the Nazi crimes. However, her request to remove the Nazi lawyers from their offices finally failed in 1969. The continuities between the Nazi judiciary and the federal German judiciary continued to have a long-term effect, as demonstrated by the interconnection of security authorities with the Nazi underground terror group, which was revealed in 2012 . Because of this continuity, the long "iron silence" and the few attempts to punish Nazi judicial crimes, it is almost impossible to speak of a successful coming to terms with the past of the Federal Republic of Germany. Civil society protests such as those of the exhibitors remained exceptions.

For Reinhard Strecker's 85th birthday in 2015, the Berlin State Center for Political Education , the Forum Justizgeschichte eV and the Center for Research on Antisemitism at the TU Berlin hosted a joint event. In the announcement text , Michael Kohlstruck recalled the importance of the exhibition: Strecker had prepared it through months of meticulous research, for the first time showed personal continuities between the Nazi system and the Federal Republic and thus contributed significantly to a historical learning process. He maintained his goal of a “critical self-enlightenment of democracy” despite considerable hostility and thus set an instructive example of moral courage .

In 2012, the Federal Ministry of Justice set up an independent scientific commission to research and document how the office dealt with its own Nazi past. The final report from 2016 recognized the exhibition as a pioneering achievement.

Additional information

See also

literature

- Kristina Meyer: Too far to the left: The SDS and the "Unpunished Nazi Justice". In: Kristina Meyer: The SPD and the Nazi past 1945–1990. Wallstein, 2015, ISBN 3-8353-2730-5 , pp. 217-227.

- Gottfried Oy, Christoph Schneider: The sharpness of the concretion. Reinhard Strecker, 1968 and National Socialism in West German Historiography. Westphalian steam boat, Münster 2013, ISBN 978-3-89691-933-5 .

- Dominik Rigoll: " Unpunished Nazi Justice" and the consequences for the VVN. In: Dominik Rigoll: State Security in West Germany: From Denazification to Defense against Extremists. Wallstein, 2013, pp. 145-164.

- Stephan Alexander Glienke: The exhibition “Unpunished Nazi Justice” (1959–1962). On the history of coming to terms with Nazi judicial crimes. Nomos, Baden-Baden 2008, ISBN 978-3-8329-3803-1 .

- Stephan Alexander Glienke: Clubhouse 1960 - scenes from an exhibition. Lines of conflict in the Tübingen exhibition "Documents on the Nazi Justice" as a prehistory of the student fascism discourse . In: Hans-Otto Binder (Ed.): The homecoming board as a stumbling block. How to deal with the Nazi past in Tübingen . Tübingen 2007, ISBN 978-3-910090-76-7 . ( Online excerpt )

- Stephan Alexander Glienke: Aspects of change in dealing with the Nazi past. In: Jörg Calließ (Hrsg.): The reform time of the successful model BRD. Those born later explore the years that shaped their parents and teachers. Loccumer Protokoll 19/03, Rehburg-Loccum 2004, ISBN 978-3-8172-1903-2 , pp. 99-112.

- Marc von Miquel: Punish or amnesty? West German Justice and Politics of the Past in the Sixties. Wallstein, Göttingen 2004, ISBN 3-89244-748-9 , pp. 27-56.

- Paul Ciupke: “A sober knowledge of the real…” The contribution of political education and exhibitions to “ coming to terms with the past” between 1958 and 1965. In: Research Institute Work - Education - Participation at the Ruhr University Bochum (Ed.): Yearbook Work - Education - Culture, Volume 19/20 (2001/2002). ISSN 0941-3456 , pp. 237-250.

- Michael Kohlstruck: From political action to private outrage. The exhibition “Unatunited Nazi Justice” (1959) and the Wehrmacht exhibition (1995) in comparison. In: Freibeuter 80 (1999), pp. 77-86.

- Michael Kohlstruck: The second end of the post-war period. On the change in political culture around 1960. In: Gary S. Schaal, Andreas Wöll (Hrsg.): Coping with the past. Models of political and social integration in West German post-war history. Nomos, Baden-Baden 1997, ISBN 3-7890-5032-6 , pp. 113-127.

- Klaus Bästlein: "Nazi blood judges as pillars of the Adenauer regime". The GDR campaigns against Nazi judges and public prosecutors, the reactions of the West German judiciary and their failed “self-cleaning” 1957–1968. In: Helge Grabitz and others (ed.): The normality of crime. Berlin 1994, pp. 408-443.

swell

- Wolfgang Koppel: Justice in the Twilight. Documentation: NS judgments, personal files, catalog of accused lawyers. Karlsruhe 1963.

- Wolfgang Koppel: Unpunished Nazi justice. Hundreds of judgments indict their judges. Published on behalf of the organizing committee of the document exhibition "Unpunished Nazi Justice" in Karlsruhe. (Exhibition catalog) Karlsruhe 1960.

Movies

- Gerolf Karwath: Hitler's elites after 1945. Part 4: Jurists - acquittal on their own behalf . Director: Holger Hillesheim. Südwestrundfunk (SWR, 2002).

- Christoph Weber: File D (1/3) - The failure of the post-war justice system. Documentation, 2014, 45 min. With Norbert Frei ( commentary on Phoenix.de from Nov. 2016)

Web links

- Stephan A. Glienke: The dagger under the judge's robe. The processing of the Nazi justice in society, science and jurisprudence of the Federal Republic. Contemporary history online, December 2012

- Utz Anhalt: "Unpunished Nazi Justice" - On the history of the coming to terms with National Socialist judicial crimes (review in sopos 5/2011)

- Stephan A. Glienke: The exhibition Unpunished Nazi Justice (1959-1962). Hanover 2005

- Michael Kohlstruck, Claudia Fröhlich: Where officials are silent ... (taz Magazin No. 6002 of November 27, 1999)

- Judgments that are terrifying. Student tensions over the exhibition "Unpunished Nazi Justice". Die Zeit, June 16, 1961

- Sabine Lueken: Teachers were not allowed to go . Sixty years ago the exhibition “Unpunished Nazi Justice” was opened in West Berlin. The maker only received official recognition 55 years later . In: Junge Welt from 22./23. February 2020, p. 11.

- Rainer Bieling : The exhibition “Unpunished Nazi Justice” 60 years later . In 2020, the initiator Reinhard Strecker will experience the late satisfaction of the recognition of his work in 1960 . In: Berlin Freedoms of February 23, 2020.

Individual evidence

- ↑ Devin O. Pendas: The 1st Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial 1963–1965. A historical introduction. In: Raphael Gross, Werner Renz (ed.): The Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial (1963–1965): Annotated source edition. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2013, ISBN 3-593-39960-1 , pp. 55–85, here pp. 56f.

- ↑ Stephan A. Glienke: The exhibition “Ungesunnte Nazijustiz” (1959–1962) , 2008, p. 26.

- ↑ Marc von Miquel: Punish or amnesty? West German Justice and Politics of the Past in the Sixties. Wallstein, 2004, ISBN 3-89244-748-9 , pp. 27-30.

- ↑ Marc von Miquel: Punish or amnesty? 2004, pp. 31-44.

- ↑ Devin O. Pendas: The 1st Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial 1963–1965. A historical introduction. In: Raphael Gross, Werner Renz (ed.): The Frankfurt Auschwitz Trial (1963–1965): Annotated source edition. Frankfurt am Main 2013, pp. 55–85, here p. 57.

- ↑ Marc von Miquel: Punish or amnesty? 2004, p. 48f.

- ↑ Kristina Meyer: The SPD and the Nazi past 1945–1990. 2015, p. 218

- ^ A b Marc von Miquel: Punish or amnesty? 2004, p. 50f.

- ^ A b Kristina Meyer: The SPD and the Nazi past 1945–1990. 2015, p. 219

- ^ Stephan A. Glienke: Clubhouse 1960 - Scenes at an Exhibition , Tübingen 2007, pp. 118f.

- ↑ Michael Kohlstruck: The second end of the post-war period. On the change in political culture around 1960. In: Gary S. Schaal, Andreas Wöll (Hrsg.): Coping with the past. Models of political and social integration in West German post-war history. Nomos, Baden-Baden 1997, ISBN 3-7890-5032-6 , pp. 113–127, here p. 116

- ↑ Irmtrud Wojak: Fritz Bauer 1903–1968: A biography. Beck, Munich 2011, ISBN 3-406-62392-1 , p. 367

- ^ Tilman Fichter: SDS and SPD. Partiality beyond the party. Westdeutscher Verlag, Opladen 1988, p. 306 f.

- ^ Willy Albrecht: The Socialist German Student Union (SDS). JHW Dietz, Bonn 1994, p. 356f.

- ↑ Marc von Miquel: Punish or amnesty? 2004, p. 51f. and footnote 32

- ^ A b Kristina Meyer: The SPD and the Nazi past 1945–1990. 2015, p. 217f. and fn. 2

- ↑ Marc von Miquel: Punish or amnesty? 2004, p. 53f.

- ↑ Marc von Miquel: Punish or amnesty? 2004, p. 52 and footnote 34.

- ↑ Michael Kohlstruck: The second end of the post-war period , Baden-Baden 1997, p. 118.

- ↑ Dominik Rigoll: State Security in West Germany , in 2013, S. 145f.

- ^ Arnd Bauerkämper: The controversial memory: The memory of National Socialism, fascism and war in Europe since 1945. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2012, ISBN 3-657-77549-8 , p. 124f.

- ↑ Christoph Schneider: The appropriation. In: Gottfried Oy, Christoph Schneider: The Sharpness of Concretion , Münster 2013, pp. 198f.

- ↑ Wolfgang Koppel: Unpunished Nazi Justice. Hundreds of judgments indict their judges. Hectographed exhibition catalog . Karlsruhe 1960.

- ↑ Irmtrud Wojak: Fritz Bauer 1903–1968 , Munich 2011, p. 368

- ↑ Stephan A. Glienke: The exhibition Unatunited Nazi Justice (1959–1962). In: Bernd Weisbrod (Ed.): Democratic transitions. The end of the post-war period and the new responsibility. Conference documentation of the annual conference of the Contemporary History Working Group Lower Saxony (ZAKN), Göttingen, 26./27. November 2004. Göttingen 2005, pp. 31–37, here p. 31.

- ↑ Stephan A. Glienke: The exhibition “Ungone Nazi Justice” (1959–1962) , 2008, p. 174

- ↑ Stephan A. Glienke: The exhibition “Ungesunten Nazijustiz” (1959–1962) , 2008, p. 188

- ↑ On February 24, 1960, the Berlin daily newspapers report on the opening the day before, according to Der Kurier in an article signed by name by Dr. Erika Altgelt: “The show opened yesterday. It is open until March 7 on Wednesdays, Saturdays and Sundays from 10 a.m. to 10 p.m., on the other days from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. Of course, entry is free. "

- ↑ Stephan A. Glienke: The exhibition "Ungesunten Nazijustiz" (1959–1962) , 2008, p. 97 and fn. 380

- ↑ Stephan A. Glienke: The exhibition “Ungone Nazi Justice” (1959–1962) , 2008, p. 103

- ↑ Stephan A. Glienke: The exhibition “Ungone Nazi Justice” (1959–1962) , 2008, p. 265

- ↑ Stephan A. Glienke: The exhibition "Ungesunten Nazijustiz" (1959–1962) , 2008, p. 92f.

- ^ Stephan A. Glienke: Post-war scandal: students against Nazi judges. Der Spiegel, February 24, 2010

- ↑ Stephan A. Glienke: The exhibition “Ungesunnte Nazijustiz” (1959–1962) , 2008, p. 141

- ↑ Stephan A. Glienke: The exhibition “Ungesunten Nazijustiz” (1959–1962) , 2008, p. 151

- ↑ Manfred Görtemaker, Christoph Safferling: The Rosenburg files: The Federal Ministry of Justice and the Nazi era. Beck, Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-406-69769-2 , pp. 306f.

- ↑ Stephan A. Glienke: The exhibition "Ungesunten Nazijustiz" (1959–1962) , 2008, p. 126f.

- ↑ Stephan A. Glienke: The exhibition “Unges atoned Nazijustiz” (1959–1962) , 2008, p. 115 and fn. 461 and 462.

- ↑ Stephan A. Glienke: "Such a thing does harm abroad ...": Dealing with National Socialism - Differences between the Federal Republic of Germany and Great Britain. In: Jörg Calließ (Ed.): The history of the successful BRD model in international comparison. Rehburg-Loccum 2006, (Loccumer Protocols 24/05), ISBN 978-3-8172-2405-0 , pp. 35-61.

- ^ Norbert Frei: Careers in the Twilight: Hitler's Elites after 1945. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2001, ISBN 3-593-36790-4 , p. 211

- ↑ Marc von Miquel: Punish or amnesty? 2004, p. 54

- ↑ Manfred Görtemaker, Christoph Safferling: The Rosenburg Files , Munich 2016, pp. 304f. and fn. 153

- ↑ Christoph Schneider: The appropriation. In: Gottfried Oy, Christoph Schneider: The Sharpness of Concretion , Münster 2013, p. 198, fn. 19.

- ↑ Stephan A. Glienke: The exhibition “Ungone Nazi Justice” (1959–1962) , 2008, p. 248, fn. 1051

- ↑ Bernd M. Kraske: Duty and Responsibility: Festschrift for the 75th birthday of Claus Arndt. Nomos, 2002, ISBN 3-7890-7819-0 , p. 69

- ↑ Marc von Miquel: Punish or amnesty? 2004, p. 52 and footnote 361

- ^ A b NS judge: On photocopies. The mirror no. 3/13. January 1960

- ↑ Marc von Miquel: Punish or amnesty? 2004, p. 55 ; Nazi judge: easy cases? Der Spiegel, February 17, 1960

- ↑ Manfred Görtemaker, Christoph Safferling: The Rosenburg Files , Munich 2016, p. 306f.

- ↑ Manfred Görtemaker, Christoph Safferling: The Rosenburg Files , Munich 2016, p. 308

- ↑ Stephan A. Glienke: The exhibition "Ungesunten Nazijustiz" (1959–1962) , 2008, p. 204f.

- ↑ Claudia Fröhlich: "Against the tabooing of disobedience": Fritz Bauer's concept of resistance and the reappraisal of Nazi crimes. Campus, Frankfurt am Main 2006, ISBN 3-593-37874-4 , p. 224

- ↑ Irmtrud Wojak: Fritz Bauer 1903-1968 , Munich 2011, pp 368 - 376

- ↑ Henning Borggräfe, Hanne Leßau, Harald Schmid (ed.): Findings: The perception of the Nazi crimes and their victims in the course of change. Wallstein, 2015, ISBN 3-8353-2856-5 , p. 17f. ; Harald Schmid: The past is a warning . Genesis and reception of a traveling exhibition on the National Socialist persecution of Jews (1960–1962). In: Journal of History 60 (2012) 4, pp. 331–348.

- ^ A b Christian Staas: German lawyers and the Nazi dictatorship: What was right then ... In: Die Zeit, February 25, 2009

- ↑ a b c Sebastian Felz: Research on Nazi Justice after 1945 - An Interim Review (HSozKult, April 1, 2014)

- ↑ Georgios Chatzoudis: The biased constitutional state: The West German justice and the Nazi past. Gerda Henkel Foundation, April 20, 2010; Numbers from Hubert Rottleuthner: Careers and continuities of German legal lawyers before and after 1945: with all basic and career data on the enclosed CD-ROM. Berliner Wissenschafts-Verlag, Berlin 2010, ISBN 3-8305-1631-2 (tables from p. 71)

- ↑ Stephan A. Glienke: The exhibition “Ungone Nazi Justice” (1959–1962) , 2008, p. 20

- ^ Norbert Frei: Careers in Twilight: Hitler's Elites after 1945. Campus, 2001, ISBN 3-593-36790-4 , pp. 210-213

- ↑ Annette Weinke: The persecution of Nazi perpetrators in a divided Germany: Coming to terms with the past 1949-1969, or, A German-German relationship history in the Cold War. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2002, ISBN 3-506-79724-7 , pp. 101-107 and p. 400

- ↑ Dominik Rigoll: The history of the successful FRG model in international comparison (HSozKult, August 12, 2005)

- ↑ Annette Weinke: S. Glienke: The exhibition "Ungone Nazi Justice" (1959–1962) (HSozKult, June 3, 2009)

- ↑ Oy / Schneider quoted. after Stephan A. Glienke: G. Oy et al .: The sharpness of the concretion (HSozKult, October 29, 2013)

- ↑ Michael Kohlstruck: Reinhard Strecker. Pioneer of critical politics of the past. (HSozKult, September 17, 2015)

- ↑ Manfred Görtemaker, Christoph Safferling: The Rosenburg Files , Munich 2016, p. 302ff.