Vaginal cytology

The vaginal cytology (synonym Kolpozytologie , from Latin vagina or Greek κόλπος kólpos ' sheath ' as well as Greek κύτος kytos ' cell ' and λόγος lógos ' doctrine ') is the microscopic examination of cells from the inner lining of the vagina - the vaginal epithelium - be won. It must be distinguished from the Pap test , which is used to diagnose tumors , in which the smear is taken from the cervix and the external cervix . Since the vaginal epithelium shows characteristic changes in the menstrual cycle under the influence of sex hormones , conclusions can be drawn about the hormonal status of the patient based on the cell structure. Vaginal cytology is a simple and inexpensive procedure for the basic diagnosis of hormonal disorders in gynecology . Vaginal cytology also plays a subordinate role in the diagnosis of vaginal inflammation and vaginal tumors .

Hormone-dependent changes in the course of the sexual cycle take place in all mammals . In veterinary medicine, vaginal cytology is only of greater practical importance in bitches . Here it is mainly used to determine the optimal mating time , the combination with a vaginal examination and a progesterone determination providing the most reliable results.

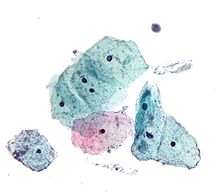

Under the microscope, four cell types can be distinguished in the vaginal epithelium: basal, parabasal, intermediate and superficial cells, and in bitches also “clods”. Under the influence of estrogens results in a cell proliferation with a thickening of the vaginal epithelium and an increased incidence of superficial cells (follicular cell image). A high proportion of intermediate cells indicates high progesterone levels (luteal cell picture). If, on the other hand, there is no significant formation of sex hormones (normal in childhood and old age), basal and parabasal cells dominate (atrophic cell structure).

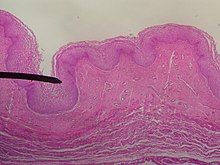

Vaginal epithelium

The inner lining of the vagina, the vaginal epithelium , is made up of several layers of cells in mammals , which are not keratinized and whose superficial cell layers are flattened (multi-layered uncornified squamous epithelium) . The cell layer lying directly on the basement membrane is called the basal layer , the middle cell layers as the middle or intermediate layer and the superficial ones as the superficial layer . The vaginal epithelium is subject to typical, repetitive changes in the course of the sexual cycle , which are primarily due to the influence of estrogens . With the increase in estrogens before the follicle rupture , cells multiply with an increase in the number of cells (in women up to fifty, in bitches up to thirty) as well as a partial cornification of the epithelial cells. Hormonally-induced remodeling processes also take place in other sections of the female genital organs, but the vaginal epithelium already reacts to much smaller amounts of hormones than, for example, the lining of the uterus .

Without estrogen activity, the vaginal epithelium consists of only a few cell layers and with a vaginal swab only small round cells are obtained, which come directly from the basal layer ( basal cells ) or the cell layers immediately above it (parabasal cells) . The parabasal cells form a cell layer with five to ten layers. They are slightly larger than the basal cells and multipotent cells, which are the starting point for the epithelial cells located further on the surface, but which can also differentiate into histiocytes or gland cells . Under the influence of estrogen, the ratio between the cell nucleus and cytoplasm , the nucleus-plasma ratio , decreases. As a result of cell aging, the parabasal cells develop into cells with shrunken , foamy-appearing cell nuclei (intermediate cells ) . These can be differentiated into “upper” and “deep” intermediate cells based on the core-plasma ratio. Intermediate cells produce abundant glycogen and store it. The further shrinkage of the nucleus and the formation of mucopolysaccharides are characteristics of the superficial cells (superficial cells) . The mucopolysaccharides form a keratin-like cell structure. In predators, maximally cornified cells without a nucleus, which are known as clods , develop . Intermediate and superficial cells are constantly being detached from the epithelium ( exfoliation , peeling). The sugars they contain are fermented into lactic acid by the bacteria in the vaginal flora and the cells decompose ( cytolysis ), which takes about a week under normal conditions for women. Cytolysis only takes place in the presence of glycogen-containing cells, i.e. when the epithelium has broken down as far as the upper intermediate cells and these peel off. During this process, the cytoplasm is primarily dissolved. In contrast to degenerative processes , the cell nuclei remain as "naked nuclei ".

| Cell type | features |

|---|---|

| Basal cell |

|

| Parabasal cell |

|

| Intermediate cell |

|

| Superficial cell |

|

| plaice | in dogs and cats: like superficial cells, but without a nucleus |

Vaginal cytology in women and girls

cycle

Girls currently have their first menstrual period ( menarche ) on average around 13 years of age. In the first days of the cycle, the old uterine lining is shed with the menstrual period ( desquamation phase , 1st to 4th day of the cycle). After the bleeding stops, new ovarian follicles mature in the ovary . Under the influence of estrogens , the uterine lining is rebuilt and thickened to 10 to 12 mm ( proliferation phase , 5th to 14th day of the cycle). As a rule, only one follicle matures into a ripe Graafian follicle, and an egg cell is released from it when the follicle ruptures. The remnant of the follicle develops into the corpus luteum , which produces the pregnancy-maintaining hormone progesterone . The progesterone causes the transformation into a secretory epithelium. The mucous membrane is prepared for the reception of a fertilized egg cell ( nidation ) and its thickness increases to 15 mm ( secretion phase , 15th to 28th day of the cycle). If fertilization and nidation do not take place, the corpus luteum regresses. The progesterone level falls from the 25th day of the cycle, the blood flow is reduced. The mucous membrane damaged by the insufficient blood flow is broken down and shed with the next menstrual period. During the menopause , the sexual cycles become rarer and finally they stop completely ( menopause ) on average by the age of 52 (40–60 years ).

evaluation

For the vaginal cytology is with a cotton swab, spatula or a fine brush (Cytobrush) cell material from the top third of the lateral vaginal wall removed ( vaginal ), and then fixed and stained , usually with the Papanicolaou stain . Alternatively, isotonic saline solution can be added to the vaginal fluid and it can be assessed under a phase contrast microscope . This saves the dyeing process and thus delivers quick results. Microorganisms such as Candida albicans or Trichomonas vaginalis are also easily recognizable. The disadvantage is that cell nuclei are only indistinctly differentiated and cannot be further assessed. This makes it difficult to estimate the core-plasma ratio. Also, tumor cells can not be detected because they are identified primarily by nuclear changes. In addition, the documentation of the findings is problematic, as the preparation becomes unusable after a few minutes as it dries up.

Four basic cell patterns can be distinguished microscopically:

| Basic type | Cycle phase | dominant cell type |

|---|---|---|

| Follicular cell picture | Proliferation phase | Superficial and intermediate cells |

| Luteal cell picture | Secretion phase | medium-sized ("upper") intermediate cells |

| Androgenic cell structure | - | slightly folded intermediate cells |

| Atrophic cell picture | Post menopause , childhood | Parabasal and basal cells |

During the menstrual period, numerous red blood cells as well as gland and stroma cells of the uterine lining are found in the cell picture .

In addition to the cervix score, vaginal cytology is a simple and inexpensive examination method for the first assessment of the hormone status. However, it is too imprecise to determine the cycle phase; the blood levels of the hormones estradiol , LH and progesterone are also determined here today .

An atrophic cell picture in a woman of childbearing age is an indication of insufficient activity of the anterior pituitary gland or the ovaries ( ovarian failure ). In children who normally have an atrophic cell structure, vaginal cytology is used to clarify premature sexual maturity ( pubertas praecox ) or premature breast development (premature thelarche , infantile macromastia ). In adolescents with no first menstrual period ( menarche ), an atrophic cell picture with simultaneously high LH and FSH values is an indication of malformation of the ovaries . If menarche has occurred, vaginal cytology provides information as to whether the hormones involved are in balance. The vaginal cytological examination is therefore one of the minimum requirements before prescribing a birth control pill and during the six-monthly check-ups. An androgenic cell picture occurs when large amounts of male sex hormones ( androgens ) are formed. This can indicate, for example, an adrenogenital syndrome or a Sertoli - Leydig cell tumor ( androblastoma ).

Degenerative cell changes occur on the flaked cells, especially in unfavorable environmental conditions. In contrast to physiological cell lysis, changes in the cell nucleus also occur here. Core swelling , dissolution , shrinkage and fragmentation can occur. The accumulation of chromatin particles on the nuclear envelope stains it more strongly ( nuclear wall hyperchromasia ). Increased red coloration in the cytoplasm can occur due to degenerative processes (pseudoeosinophilia), halo formation around the cell nucleus, vacuolization , compression with intense red coloration (hyalinization), partial disintegration, dissolution (heterolysis), change in cell shape and maturation disorders.

In acute inflammation , granulocytes often appear. Serious infections lead to increased exfoliation of parabasal cells, the nucleus-plasma relationship shifts towards the nucleus, areas in the cytoplasm that are partly red and partly blue can appear and the background image looks dirty due to protein-rich precipitation . In the case of chronic inflammation, on the other hand, round cells dominate ( histiocytes , lymphocytes , plasma cells ).

Cocci infections cause increased nuclear shrinkage and eosinophilia with pseudokeratinization. In the case of a Gardnerella infection , the epithelial cells are often coated with powdered sugar. A vaginal yeast usually manifests itself in pseudoeosinophilia, cell breakdown ("measles or window cells") and a blurred background. Trichomonas vaginalis usually stains poorly with the routine staining, so that the causative agent of trichomoniasis can be mistaken for the basal cells of similar size. Phase contrast microscopy is better suited for its detection. Herpes simplex infections damage the parabasal cells. Nuclear wall hyperchromasia, several cell nuclei and inclusion bodies occur here. In the case of human papilloma viruses , in addition to nuclear wall hyperchromasia and binuclear cells, cavities in the cytoplasm ("koilocytes") are typical.

The vaginal cytology of a specifically obtained smear can also provide initial indications of early forms of vaginal carcinoma , but the finding is always confirmed by a biopsy with a patho- histological examination. To diagnose the much more common cervical cancer or uterine tumors, a cervical smear is taken directly and examined using a Pap test .

Radiation exposure , folic acid deficiency and various cytostatic agents used in chemotherapy can also lead to changes in the cell structure.

Cell indexes

A number of key figures (indices) can be determined to assess hormonal activities. However, with the possibility of precise hormone determinations, they have lost their practical importance, since they only reflect the relationship between the sex hormones. The karyopycnosis index indicates the proportion of cells with a shrunken nucleus, the eosinophilia index the proportion of red-stained superficial cells and the folding index the proportion of folded superficial and intermediate cells. The eosinophilia index reaches its maximum of 50% in the middle of the cycle and its minimum of 20% at the beginning of the cycle. The karyopyknosis index follows the eosinophilia index, its values are 10 percentage points higher. These indices reflect the estradiol concentration in the blood plasma , with the index maxima occurring about one to two days behind the maximum hormone level.

Hormonal contraceptives ( birth control pills ) may influence the cell structure and the cell indices. The sequence preparations imitate the normal hormonal cycle, the cell indices show a normal cycle course, but are slightly lower than without the birth control pill. The combination preparations cause a constant hormone level and thus constant indices of 20 to 30%. The estrogen-free " mini pill " leaves the cell structure largely undisturbed. For hormone replacement therapy in postmenopause, the indices are constantly between 20 and 30%.

Proliferation score

The degrees of maturity of the vaginal epithelial cells can be coded with digits. In the classic Schmitt classification , parabasal cells are designated with 1, small intermediate cells with 2, large intermediate cells with 3 and superficial cells with 4. In the case of mixed cell patterns, the most common and the second most common cell population is determined after a rough estimate. A grade 1 proliferation score means that only parabasal cells are present, grade 4-3 means that mainly superficial cells and also some large intermediate cells are present.

The disadvantage of this classification is that the delimitation of large from small intermediate cells is not entirely clear and that neither basal cells nor the baso- or eosinophilia of superficial cells are taken into account. The modified classification according to Schmitt takes these inadequacies into account. Basal cells are coded with 0, parabasal cells with 1, intermediate cells with 2, basophilic superficial cells with 3 and eosinophilic superficial cells with 4. Determining the proliferation score is an inexpensive and quick method of estimating the approximate sex hormone levels, which is why it is still used today in routine diagnostics.

A high proliferation (score 4 or 3) is normal in sexually mature women, but also in babies in the first week of life, because the sex hormone levels from the time in the womb still have an effect in the latter. In normal pregnancy, the high progesterone levels prevent the epithelial cells from fully maturing despite high estrogen levels; In the case of a disturbed pregnancy, on the other hand, the progesterone level falls, which is why a high proliferation score can occur.

A low proliferation (score 0 or 1) is to be found with very low sex hormone levels, for example in childhood and after the menopause, but also with dead fruit in the womb, after an ovary removal and during breastfeeding after childbirth. Low proliferation can also occur under the " mini pill " or with inflammation .

An average proliferation (score 2) when taking steroid hormone preparations typical. Other active ingredients such as histamine and cardiac glycosides can also trigger moderate proliferation.

A mixed proliferation with varying values occurs in 10% of all women after the menopause because sex hormones are formed in the adrenal cortex and in adipose tissue .

Vaginal cytology in the bitch

cycle

The sexual maturity occurs in dogs aged six months to two years. Dogs usually have two heats per year with a phase of hormonal inactivity ( anestrous ) in between. Heat begins with a pre-oestrus ( proestrus ), in which follicles mature and produce large amounts of estrogens. The estrogens also cause red blood cells to pass through the vaginal lining. Two to three days before the follicle cracks (ovulation) there is a maximum release of the luteinizing hormone , which in turn leads to an increase in progesterone and a decrease in estrogens . The actual phase of deck readiness (“ standing heat ”) only takes a few days. In the after-oestrus ( metestrus ), the secretion and cell material remaining in the vaginal lumen are broken down by white blood cells (" neutrophil clearing phase"). There is no phenomenon corresponding to menopause in dogs, the number of heats per year usually decreases in old age, but the sexual cycles do not cease completely.

evaluation

The sample is taken with a moistened cotton swab, preferably from the roof of the vagina. If no bacteriological examination is planned, the sample can also be taken from the vaginal vestibule , as the same cell changes occur here. However, the keratinized superficial cells that are always present here physiologically can make the assessment more difficult. The stick is then unrolled on a slide, the sample air-dried and stained with a rapid staining set. Rapid stains of the Romanowsky type are particularly common in veterinary medicine . Papanicolaou or Trichrome stains are more suitable for assessing keratin precursors, but require more extensive equipment and are more time-consuming and costly. Instead of removing it with a cotton swab, a pipette can be used to insert sterile isotonic saline solution into the rear vagina and suck it in again (rinsing sample). Each phase of the oestrus cycle has different dominant cell types, whereby the transitions are always fluid:

| Cycle phase | Duration | features |

|---|---|---|

| Proestrus | 9 (1-27) days |

Erythrocytes , intermediate and superficial cells

at the beginning also parabasal cells, in the course an increase in superficial cells and a decrease in erythrocytes |

| Oestrus | 8 (4-24) days | Superficial cells and clods (> 80%), hardly any erythrocytes

towards the end clods are stored together to form “nests” |

| Metestrus | 60-80 days | Intermediate and parabasal cells steadily increasing

also neutrophils at the beginning |

| Anestrus | a few weeks to several months | low in cells, especially parabasal, some basal cells |

In bitches before sexual maturity, the cell structure resembles that in the anoestrus.

Vaginal cytology is mainly used in veterinary medicine to determine the time of mating. The fertile phase of a bitch is between four days before to four days after the follicle cracks, the four days after ovulation are optimal. Particularly in the case of artificial insemination or if the stud dog lives far away, a precise determination of the time of ovulation is usually essential. Vaginal cytology alone only leads to optimal occupancy in two thirds of the cases. Since the maximum keratinization can occur four days before to one day after the follicle cracks, the accuracy of the prediction is limited. The one to two day determination of the progesterone level offers a more precise prediction, but is usually only possible in external laboratories, so that the results are only available with a time delay. The combination of colposcopy , vaginal cytology and progesterone determination is best . Alternatively, the bitch can be mated every two to three days for the entire cytological oestrus phase.

Further indications for a vaginal cytology are a lack of readiness for breeding and a lack of heat after at least one heat. In ovarian cysts and granulosa cell tumors, there is a cell pattern as in heat. With vaginal inflammation or uterine suppuration , bacteria and white blood cells are abundant ; with bacterial vaginal inflammation, degenerate granulocytes and phagocytosed bacteria are common. Bacteria can also occur in healthy animals in the proestrus or puerperium , and occasionally also in the estrus or metestrus. In most cases, the microscopic detection of bacteria in the context of vaginal cytology does not correlate with the results of a bacteriological examination for which samples should be taken from the vaginal vault.

Vaginal cytology is also suitable for diagnosing sticker sarcoma . Here, vacuolated round cells with numerous mitoses can be detected. The cell nuclei are usually somewhat eccentric, show different sizes (anisokaryosis) and a coarse chromatin structure . Other vaginal tumors in the bitch are usually benign and of mesenchymal origin ( leiomyomas , fibroids , fibro papillomas ). Groups of spindle-shaped cells with an oval nucleus are typical of these tumors. Finally, vaginal cytology may be advisable in the case of diabetes in order to rule out type 3 diabetes due to high progesterone levels in an intact bitch.

Vaginal cytology in other animal species

Vaginal cytology is of some importance in determining the cycle phases in the breeding of laboratory animals such as mice and rats . Assessment of the external genital organs, measurements of electrical impedance or biochemical analysis of urine are also used for this purpose , although vaginal cytology provides the most reliable results for all phases of the cycle. The prediction accuracy of the estrous in mice is only 46%, so that the combination with a histological examination of the vaginal folds makes sense.

In the case of domestic cats , a cycle can be determined with sufficient accuracy. Since cats show follicle cracks triggered by mating (→ heat ), the mechanical irritation of the vagina when the sample is taken can already lead to ovulation. The cell pictures in cats are similar to those in bitches, but red blood cells and granulocytes usually do not occur. The proportion of superficial cells in the oestrus is lower than in the bitch (40 to 88%), clods make up about 10% of the cells on the day of ovulation and up to 40% on the following day. It is also typical that the background clearly clears up on the day of the follicle cracks. At the end of the oestrus, clods dominate, but cell nests do not occur in cats. A reasonably reliable prediction of ovulation is not possible using vaginal cytology in cats.

history

The work of Johannes Müller paved the way for the development of modern cytology . He is considered the first to be able to detect tumor cells. In 1838 he published the then pioneering work On the finer structure and the forms of pathological tumors . The first study of cell changes during the menstrual cycle was published in 1847 by Félix Archimède Pouchet . The Greek-born doctor George Nicolas Papanicolaou began systematic investigations into vaginal cytological changes in humans and animals at the beginning of the twentieth century, he also developed the alcoholic fixation of samples and new staining methods. In 1928 he published his results on cytodiagnostics. In the same year, independently of Papanicolaou, the Romanian pathologist Victor Babes also published a vaginal tumor cytological study. However, both works initially received little attention, so that Papanicolaou turned back to hormonal vaginal cytology. In 1933 he published his results under the title The sexual cycle in the human female as revealed by vaginal smears in the American Journal of Anatomy . In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Adolf Butenandt and, independently of him, other research groups discovered the various sex hormones that cause these cell changes.

The monograph Diagnosis of uterine cancer by the vaginal smear , published in 1943 by Papanicolaou and the gynecologist Herbert F. Traut , is considered to be the birth of gynecological cytodiagnostics. In 1948 Papanicolaou, Traut and Andrew Anthony Marchetti summarized their findings on vaginal cytology in the work The epithelia of woman's reproductive organs . In 1953 A. Schmitt published the graduation that is still common today for characterizing the proliferation of the vaginal epithelium. In 1957 the International Academy of Cytology was founded in Brussels. Its first chairman was the German gynecologist Hans-Klaus Zinser , who introduced phase contrast cytology in 1949 .

literature

- Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynecological cytodiagnostics . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 .

- Gerd Neumann, Axel Schäfer and Werner Mendling: phase contrast microscopy in the gynecological practice . Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg 2014, ISBN 978-3-642-38309-0 .

- Axel Wehrend: Key symptoms of gynecology and obstetrics in dogs . Enke, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8304-1076-8 , pp. 36-47 .

- Laia Solano-Gallego: vagina . In: Rose E. Raskin and Denny J. Meyer (Eds.): Canine and feline cytology . 2nd Edition. Saunders, St. Louis 2010, ISBN 978-1-4160-4985-2 , pp. 288-294 .

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynecological Cytodiagnosis . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 , p. 22 .

- ↑ Axel Wehrend: Key symptoms of gynecology and obstetrics in dogs . Enke, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8304-1076-8 , pp. 37 .

- ↑ a b c d Karl Knörr, Henriette Knörr-Gärtner, Fritz K. Beller, Christian Lauritzen: Obstetrics and gynecology: Physiology and pathology of reproduction . 3. Edition. Springer, Berlin 2013, ISBN 978-3-642-95584-6 , pp. 24-25 .

- ↑ a b Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynecological Cytodiagnosis . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 , p. 23 .

- ↑ a b Axel Wehrend: Key symptoms of gynecology and obstetrics in dogs . Enke, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8304-1076-8 , pp. 17 .

- ↑ Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynecological Cytodiagnosis . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 , p. 64-65 .

- ↑ Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynecological Cytodiagnosis . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 , p. 24-29 .

- ↑ Axel Wehrend: Key symptoms of gynecology and obstetrics in dogs . Enke, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8304-1076-8 , pp. 39 .

- ↑ a b c Laia Solano-Gallego: Vagina . In: Rose E. Raskin and Denny J. Meyer (Eds.): Canine and feline cytology . 2nd Edition. Saunders, St. Louis 2010, ISBN 978-1-4160-4985-2 , pp. 289 .

- ^ Freimut Leidenberger, Thomas Strowitzki and Olaf Ortmann: Clinical endocrinology for gynecologists . 4th edition. Springer, Heidelberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-540-89759-0 , pp. 81 .

- ^ Jan Behrends, Josef Bischofberger, Rainer Deutzmann: Physiology . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2012, ISBN 978-3-13-138412-6 , p. 425 .

- ^ Freimut Leidenberger, Thomas Strowitzki and Olaf Ortmann: Clinical endocrinology for gynecologists . 4th edition. Springer, Heidelberg 2009, ISBN 978-3-540-89759-0 , pp. 203 .

- ↑ Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynecological Cytodiagnosis . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 , p. 36 .

- ↑ Manfred Kaufmann, Serban-Dan Costa, Anton Scharl: Die Gynäkologie . 3. Edition. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg 2012, ISBN 978-3-642-20922-2 , pp. 171-172 .

- ↑ a b Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynecological Cytodiagnosis . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 , p. 32 .

- ^ Kai J. Bühling and Wolfgang Friedmann: Intensive course in gynecology and obstetrics . Elsevier, Urban & Fischer, Munich 2009, ISBN 978-3-437-42401-4 , pp. 30 .

- ↑ Alfred S. Wolf: Child and Adolescent Gynecology: Atlas and Guide for Practice . 2nd Edition. Schattauer, Stuttgart 2002, ISBN 978-3-7945-2125-8 , pp. 21-22 .

- ^ Karl Knörr, Henriette Knörr-Gärtner, Fritz K. Beller, Christian Lauritzen: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Physiology and Pathology of Reproduction . 3. Edition. Springer, Berlin 1989, ISBN 978-3-642-95584-6 , pp. 80 .

- ^ Theodor Hellbrügge: Pediatric diagnostics. Pediatric Therapy . tape 2 . Springer, Berlin 1966, ISBN 978-3-642-94950-0 , p. 621 .

- ↑ Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynecological Cytodiagnosis . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 , p. 66-67 .

- ↑ Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynecological Cytodiagnosis . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 , p. 114 .

- ↑ Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynecological Cytodiagnosis . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 , p. 120 .

- ↑ Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynecological Cytodiagnosis . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 , p. 95 .

- ↑ Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynecological Cytodiagnosis . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 , p. 101 .

- ↑ Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynecological Cytodiagnosis . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 , p. 107 .

- ↑ Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynecological Cytodiagnosis . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 , p. 109 .

- ^ Karl Knörr, Henriette Knörr-Gärtner, Fritz K. Beller, Christian Lauritzen: Obstetrics and Gynecology: Physiology and Pathology of Reproduction . 3. Edition. Springer, Berlin 1989, ISBN 978-3-642-95584-6 , pp. 670 .

- ^ Joachim Dudenhausen, Hermann PG Schneider, Gunther Bastert: Gynecology and obstetrics . 2nd Edition. DeGruyter, Berlin 2003, ISBN 3-11-016562-7 , pp. 327 .

- ↑ Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynecological Cytodiagnosis . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 , p. 89 .

- ↑ a b Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynecological Cytodiagnosis . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 , p. 33 .

- ↑ a b c d e Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynäkologische Zytodiagnostik . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 , p. 34 .

- ↑ Gerd Neumann, Axel Schäfer and Werner Mendling: Phase contrast microscopy in the gynecological practice . Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg 2014, ISBN 978-3-642-38309-0 , pp. 87 .

- ↑ Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynecological Cytodiagnosis . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 , p. 35 .

- ↑ Peter F. Suter and Barbara Kohn: Internship at the dog clinic . 10th edition. Paul Parey, Stuttgart 2004, ISBN 978-3-8304-4141-0 , pp. 859-860 .

- ↑ Axel Wehrend: Key symptoms of gynecology and obstetrics in dogs . Enke, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8304-1076-8 , pp. 41 .

- ↑ Laia Solano-Gallego: Vagina . In: Rose E. Raskin and Denny J. Meyer (Eds.): Canine and feline cytology . 2nd Edition. Saunders, St. Louis 2010, ISBN 978-1-4160-4985-2 , pp. 288 .

- ↑ Axel Wehrend: Key symptoms of gynecology and obstetrics in dogs . Enke, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8304-1076-8 , pp. 16 .

- ^ A b Laia Solano-Gallego: Vagina . In: Rose E. Raskin and Denny J. Meyer (Eds.): Canine and feline cytology . 2nd Edition. Saunders, St. Louis 2010, ISBN 978-1-4160-4985-2 , pp. 290 .

- ↑ Axel Wehrend: Key symptoms of gynecology and obstetrics in dogs . Enke, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8304-1076-8 , pp. 18 .

- ↑ Axel Wehrend: Key symptoms of gynecology and obstetrics in dogs . Enke, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8304-1076-8 , pp. 19 .

- ^ A b Laia Solano-Gallego: Vagina . In: Rose E. Raskin and Denny J. Meyer (Eds.): Canine and feline cytology . 2nd Edition. Saunders, St. Louis 2010, ISBN 978-1-4160-4985-2 , pp. 291 .

- ↑ Axel Wehrend: Key symptoms of gynecology and obstetrics in dogs . Enke, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8304-1076-8 , pp. 154-156 .

- ↑ Axel Wehrend: Key symptoms of gynecology and obstetrics in dogs . Enke, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8304-1076-8 , pp. 88 .

- ↑ Axel Wehrend: Key symptoms of gynecology and obstetrics in dogs . Enke, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8304-1076-8 , pp. 79 .

- ^ A b Laia Solano-Gallego: Vagina . In: Rose E. Raskin and Denny J. Meyer (Eds.): Canine and feline cytology . 2nd Edition. Saunders, St. Louis 2010, ISBN 978-1-4160-4985-2 , pp. 292 .

- ↑ Axel Wehrend: Key symptoms of gynecology and obstetrics in dogs . Enke, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8304-1076-8 , pp. 38 .

- ↑ Axel Wehrend: Key symptoms of gynecology and obstetrics in dogs . Enke, Stuttgart 2010, ISBN 978-3-8304-1076-8 , pp. 144 .

- ↑ Laia Solano-Gallego: Cytological internship for veterinary medicine . Ed .: Reinhard Mischke. Schlütersche, Hannover 2005, ISBN 3-89993-013-4 , p. 136 .

- ↑ Laia Solano-Gallego: Vagina . In: Rose E. Raskin and Denny J. Meyer (Eds.): Canine and feline cytology . 2nd Edition. Saunders, St. Louis 2010, ISBN 978-1-4160-4985-2 , pp. 293 .

- ↑ Astrid Wehner and Sylvia Geist: Update on insulin therapy in dogs and cats . In: Small Animal Practice . tape 59 , no. 8 , 2015, p. 443-462 , doi : 10.2377 / 0023-2076-59-443 .

- ^ SL Byers et al .: Mouse estrous cycle identification tool and images . In: PloS one . tape 7 , no. 4 , 2012, ISSN 1932-6203 , p. e35538 , doi : 10.1371 / journal.pone.0035538 , PMID 22514749 , PMC 3325956 (free full text).

- ↑ A. Galet al .: Vaginal fold histology reduces the variability introduced by vaginal exfoliative cytology in the classification of mouse estrous cycle stages . In: Toxicologic pathology . tape 42 , no. 8 , 2014, ISSN 1533-1601 , p. 1212-1220 , doi : 10.1177 / 0192623314526321 , PMID 24705880 .

- ^ Theresa Conze and Axel Wehrend: Cycle and cycle determination in cats . In: Kleintiermedizin No. 4, 2015, pp. 178–183.

- ↑ Werner E. Gerabek, Bernhard D. Haage, Gundolf Keil and Wolfgang Wegner: Encyclopedia Medical History . tape 1 . Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York 2007, ISBN 978-3-11-019703-7 , pp. 1537 ( online here ).

- ^ A b c Hans Friedrich Nauth: Gynäkologische Zytodiagnostik . 2nd Edition. Georg Thieme, Stuttgart 2014, ISBN 978-3-13-131092-7 , p. 16-17 .

- ^ A b Aristidis Diamantis, Emmanouil Magiorkinis and Helen Koutselini: 50 years after the death of George Nicholas Papanicolaou (1883–1962): Evaluation of his scientific work . In: Acta med-hist Adriat . tape 12 , no. 3 , 2014, ISSN 1334-4366 , p. 181-188 .

- ↑ JR Tata: One hundred years of hormones . In: EMBO reports . tape 6 , no. 6 , 2005, ISSN 1469-221X , p. 490-496 , doi : 10.1038 / sj.embor.7400444 , PMID 15940278 , PMC 1369102 (free full text).

- ↑ A. Schmitt: A graduation for functional cytodiagnostics in gynecology . In: Obstetrics and gynecology . tape 13 , 1953, ISSN 1431-4878 , pp. 593-603 .