Rheingold wine house

The Weinhaus Rheingold in Berlin was a large restaurant belonging to the Aschinger Group that could cater for up to 4,000 guests at the same time. The building near the Potsdamer Platz was in the Second World War with the Allied air raids badly damaged and demolished the ruins at the beginning of the 1950s.

history

The steel frame building, built from 1905 to 1907 according to plans by the architect Bruno Schmitz , was intended as a concert hall with attached meeting rooms and a wine restaurant to mark the Aschinger company's entry into upscale gastronomy. In order to avoid additional traffic at the already congested Potsdamer Platz, the use of the building was restricted to the pure catering business. The difficult construction work, combined with lowering the groundwater level and the costly securing of neighboring houses, aroused the interest of the daily press.

The contemporary architecture press reported almost enthusiastically about the completed new building in 1907. A lot of attention was paid to the monumental facade on Bellevuestrasse with reliefs by the sculptor Franz Metzner - often classified as synonymous with Alfred Messel's facade of the nearby Wertheim department store on Leipziger Platz . The luxurious interior of the fourteen halls, partly exotic, partly inspired by the Middle Ages , created a different atmosphere in each room and was intended to immerse visitors in a wide variety of worlds.

Economically, the prestige building was a failure for Aschinger. After decades of poor profitability, the group finally sold the wine house, which had previously been closed due to the war, to the Deutsche Reichspost in 1943 . In the same year the complex suffered severe damage in the air raids on Berlin . The ruin, classified as capable of being rebuilt, was demolished at the beginning of the 1950s. The site of the former Weinhaus Rheingold share today after the re-development of the Potsdamer Platz essentially the BahnTower , the folded-over Potsdamer Straße and the Kollhoff Tower .

The Aschingers - builders with visions

Aschinger's Bierquelle , founded in 1892 by the brothers Carl and August Aschinger , traded under the name of Aschinger's Bierquelle AG as a family-owned stock corporation with a share capital of three million marks since 1900 . Grown up and successful with their "Bierquellen" - standing beer halls with inexpensive meals - the Aschingers sought entry into the more upscale gastronomy from 1905. The renaming of the company in December 1906 to Aschinger's Aktien-Gesellschaft also illustrates the effort to get rid of the cheap beer source image and to open up new areas of business. With the acquisition of the old Hotel Fürstenhof on Potsdamer Platz, the first step in this expansion was taken. After an architecture competition in 1905, a striking new building with luxurious furnishings was built from 1906 to November 1907 instead of the previous building, including neighboring properties that had already been acquired.

A concert hall with adjoining meeting rooms and a restaurant was to complement the expansion. In 1905, the company also acquired several connected properties on Bellevuestrasse and Potsdamer Strasse near Potsdamer Platz. The company owners were able to win over the architect Bruno Schmitz , who was best known for his monuments such as the Kyffhäuser Monument or the German Corner , for the planning . In 1903, he had already solved a related building task with the city's Rosengarten festival hall in Mannheim . The concert hall planned for Berlin was named after Richard Wagner's opera Das Rheingold , the first part of the cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen . The architecture critic Hans Schliepmann passed on the original intentions of the builders and architects in the journal Berliner Architekturwelt : The plan was “a hall for the most distinguished concert performances”, a “kind of 'box' for the truly highest in Berlin society”. Maximilian Rapsilber described the great expectations of the builders in the magazine Der Profanbau : "[...] considering that great success in Berlin can only be conjured up by a truly grandiose company", he demanded, "to put it naively, the most beautiful house in Berlin as his own, cost what it may. "

location

The area around Potsdamer Platz changed its character several times in the course of Berlin's development from a residential to a large city. Suburban development displaced the previous country houses from the 1820s . This gave way to elegant apartment buildings and villas between 1850 and 1870 when Potsdamer Platz with its side streets became the preferred residential area of wealthy Berliners. The central location near the government district on Wilhelmstrasse and the Potsdamer Bahnhof increased the attractiveness of the district after the establishment of the Empire in 1871, but also led to the displacement of living space by office and administrative buildings as well as hotels and restaurants. Many of these buildings were built between the 1890s and the First World War .

For the construction of the Rheingold wine house, the Aschinger company acquired the plots at Bellevuestraße 19, 19a and Potsdamer Straße 3, which are only a few meters away from Potsdamer Platz, in 1905 Potsdamer Strasse, on Alte Potsdamer Strasse. A little later, another large hotel, the Grand Hôtel Esplanade, was built on the adjacent property at Bellevuestrasse 17-18a .

The three parcels together resulted in an area of 5044.67 square meters. As a result of the small-scale subdivision, the property was poorly cut and angled, only the 54 meter wide front on Bellevuestrasse allowed a representative facade design, the street front on Potsdamer Strasse at 21 meters was unsuitable for this. Nevertheless, Aschinger paid a considerable purchase price totaling four million marks. A five-storey apartment building was built on the property on Potsdamer Strasse, while the parcels on Bellevuestrasse with the “Anker Residence” by the architect Christian August Hahnemann and the Bellevuestrasse 19 house, which was converted by the same architect, still showed the typical development of the 1850s.

Change of use due to building authority concerns

The capital tied up in the high purchase price of the property should yield a quick return and the construction time for the new building should therefore be as short as possible. In order to speed up construction, the client submitted two preliminary projects, which were approved by the building police within three to four weeks. The approval of the project itself took nine months "in spite of the greatest and most gracious consideration from all the responsible authorities". An addendum submitted while the project was still being examined required another nine months - conditions which, in the opinion of the magazine Der Profanbau, indicated the need for reform of the Berlin building police order.

For the Aschinger company, the approval was associated with a difficult condition. The building police feared that the planned concert hall would cause a further increase in traffic on Potsdamer Platz, which was already overloaded. To make matters worse, there was already an event location in the form of the Künstlerhaus of the Association of Berlin Artists in Bellevuestrasse 3, directly opposite the planned concert hall. The building police only allowed it to be used as a restaurant. The edition mainly concerned the concert hall on Bellevuestrasse. However, the planning was already too far advanced for major changes and the original conception of the Rheingold was largely retained, even if the concert hall section now also had to be used for catering purposes. In addition, the planned extension of Vossstraße to the Tiergarten gave the building owner and some architecture critics hope that the restraint on Potsdamer Platz would no longer be used and that the house could still serve its original purpose.

Construction phase

Construction work began in mid-November 1905 with the demolition and excavation work on Bellevuestrasse, followed by the construction of the foundations . The masonry work could already begin there in February 1906. At the same time, the foundation work was carried out on the property at Potsdamer Straße 3, where the machine foundations for the in-house power plant also had to be laid. This work was completed in May 1906.

The foundations, like the earthworks carried out by the construction company Wayss & Freytag , were difficult because of the necessary lowering of the groundwater level and the built-in location of the property and cost almost 500,000 marks. First of all, the excavation pit was excavated to the level of the groundwater level at a depth of approximately 3.1 meters. 65 four- inch (approx. 10 cm) suction wells, drilled five meters on all sides and reaching 7.5 meters deep from the base of the excavation pit, contained the rising groundwater. The main collecting pipe with a diameter of 250 millimeters, located at the level of the groundwater table, was connected to the well on the one hand and to the electrically operated centrifugal pump on the other hand via horizontal pipe strings . This sucked the groundwater from the well into the main collecting pipe and raised it to street level, where it drained into the municipal sewer system. The groundwater level was lowered in two stages: first by 3.20 meters for the normal basement foundations and then by 4.60 meters for the machine foundations. The lowered mirror contained a safety reserve of around 90 centimeters so that the construction site would not be flooded immediately in the event of a pump failure. Even so, the failure of the pump submerged the site several times, resulting in a total of seven working days of failure. The system for lowering the groundwater level remained in operation for seven months until the concrete slab of the foundation with the surrounding walls exerted a counter pressure corresponding to the groundwater buoyancy.

The converted property required securing of neighboring buildings in the form of bracing of the gables and the undercutting of foundations of the neighboring houses. However, subsidence and cracks as a result of the lowering of the groundwater could not be completely avoided. The daily press reported on it in sensational articles as "House collapse on Potsdamer Platz". The most serious incident, in which the basement floor tore in the side wing of the house at Potsdamer Strasse 4, led to the police blocking the house due to the risk of collapse. Construction work could only continue after additional safeguards. The house owner received compensation of 30,000 marks for the damage, but had the house demolished shortly afterwards in order to rebuild the property, as had probably been planned for a long time.

The house at Potsdamer Straße 3 required special precautions on the building site itself. The tenants, including a branch of the advertising expedition of the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger , still had long-term rental agreements, for which they demanded correspondingly high sums. Finally, the Aschinger company managed to come to an agreement with the tenants of the basement, ground floor and first floor of the house, which made it possible to partially demolish the old house. The old side wing and the western part of the house up to the second floor were gradually demolished, while at the same time the new building grew in height. The upper floors of the old house hovered over the complicated construction site, reinforced by tie rods, window and door stiffeners and supported by numerous supports.

The tight schedule often required night shifts. The site management also had to struggle with work stoppages. Right at the beginning, a strike by the bricklayers halted all construction, and eight weeks before the planned opening, the marble workers halted work. They demanded 25 percent more wages and the waiver of night shifts - knowing full well that the timely completion of the construction mainly depended on them. The executing company eventually had workers come from their Belgian plants to complete the work.

Despite all the adversities, the shell was completed in July 1906, and construction was completed by early February 1907. The opening was originally supposed to take place on January 27th, the birthday of Kaiser Wilhelm II , but was delayed until February 6th, 1907. The contemporary architecture press praised the short construction time of 14½ months as a record given the difficult foundation work and the rich interior design.

The accumulated construction costs of around 4.5 million marks exceeded the initially calculated 3.5 million marks by a considerable amount. The reasons for the increase in costs were changes in the planning and the interior work with “the finest building materials”, which was more expensive than planned. The construction costs, which are considerable for a private client, are illustrated by a comparison with the construction costs of four million marks for the Kaiser Wilhelm National Monument, completed in 1897, and of seven million marks for the old town house in Berlin, completed in 1911 .

The Deutsche Bauzeitung calculated costs of 560 marks per square meter for the shell including the foundation and 940 marks for the interior work. The cubic meter of enclosed space cost a total of 55.60 marks, of which 20.80 marks went to the shell construction including the foundation and 34.80 marks to the interior work.

Building description

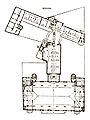

Bruno Schmitz divided the building dimensions into three wings. The hall construction of the planned concert hall, the largest of the three, extended along Bellevuestrasse and was seamlessly connected to the development of the neighboring properties. The restaurant wing on Potsdamer Straße pierced the existing front building on the lower floors. At a right angle to Potsdamer Straße, it initially followed the south-western boundary of the property and reached as far as the adjacent parcel of the Grand Hotel Esplanade . The connecting wing, also used for catering, connected the other two wings. Starting at right angles from the central axis of the hall building, it met the wing on Potsdamer Strasse at an oblique angle, with a rotunda cleverly mediating between the various axes. The courtyards on the remaining areas of the irregularly cut property were sometimes used in a more elaborate manner in summer as an extension of the restaurants, and sometimes as pure farmyards.

The regulations of the building police, according to which the courtyards had to have an access road, and the client's wish for floors as continuous as possible from Bellevuestrasse to Potsdamer Strasse determined the horizontal structure of the building complex. Since the representative facade on Bellevuestrasse should not be disturbed by a passage, all courtyards had to be accessed from Potsdamer Strasse. The passages required for this required crossing the connecting structure twice and would have prevented a continuous ground floor. Schmitz found the solution in that, on the one hand, he lowered the level of the two courtyards to be developed by half a floor compared to street level and, on the other hand, raised the level of the ground floor in the connecting wing and in the rear part of the wing on Potsdamer Straße by half a floor. Not only could the passages be carried out without problems - there was space for additional rooms under the raised halls on the ground floor. Staircases inside mediated between the different levels and created interesting passageways such as the “Red Hall”. Together with the actual staircases, they allowed visitors to walk through the variedly designed room sequences on the ground floor, hall and gallery floors in a variety of ways.

The four- to five-storey steel frame building with its progressive facade on Bellevuestrasse promised a correspondingly modern interior design. However, this was done according to more conservative, decoration-oriented aspects. She found her motifs mainly in the eponymous opera Rheingold and the other operas from Wagner's tetralogy , but also integrated medieval and exotic decorations and other legends to create a peculiar fusion of mythical and national symbolism with Art Nouveau elements.

The expensive and noble building materials, rare types of marble and precious woods, created the luxurious atmosphere appropriate to the “most beautiful house in Berlin” . Even for the work, the Aschinger company attached great importance to prestige - among the executing companies there were a striking number of purveyors to the court, many of whom were involved in the renovation of the Berlin City Palace under Wilhelm II.

The hall on Bellevuestrasse

Facade on Bellevuestrasse

Two risalit-like , 5.3-meter-wide portal porches protruding 3.5 meters from the building line framed the five-axis main facade on Bellevuestrasse. Its essentially semicircular floor plan was broken on the front side by concave indentations . On the ground floor, the portals covered with triangular gables led from the terrace into the pillar hall of the hall building. On the upper two floors, windows divided by stone pillars illuminated the stairwells behind. A bell-shaped dome roof made of copper closed the risalites below the main cornice.

Strong and smooth wall pillars , like the rest of the stone facade made of Franconian shell limestone , divided the 53.21 meter long front vertically. The horizontal was emphasized by a narrower, one meter wide cornice above the ground floor and a slightly wider cornice above the mezzanine at 1.2 meters. The inscription "WEINHAUS RHEINGOLD" affixed with gold-plated metal letters in the middle of the upper ledge advertised the restaurant discreetly. The inner division of the hall into the ground floor, cloakroom and hall floor could be read from the outside on these ledges.

The cornice segment shape erupting arched over the continuous, divided by post large windows of the hall floor called the architectural critic Hans Schliepmann as "the most effective moment of the facade design." The impetus for this solution was the height of the building front on Bellevuestrasse, which was required by the building authorities and forced Bruno Schmitz to move the vaulted ceiling of the planned concert hall to the top floor. This enabled him to bring the main cornice into compliance with the regulations and only the arched windows ended above it. The roof, originally covered with copper, followed on top. Presumably, the “strangely designed and necessarily part of the overall impression” copper roof disappeared just a few years after completion of the construction as a metal donation during the First World War. Photos from the 1920s show the newly tiled roof with the large-format lettering "WEINHAUS RHEINGOLD" inlaid with white tiles. Schmitz used the same motif with the arched windows breaking through the main cornice a second time in 1910 in his competition design for the Reißmuseum in Mannheim .

The monumental force of the tectonic archetypal forms of the pillars and cornices required the appropriate building sculpture. The eight high relief panels with allegorical representations such as “vanity”, “art”, “music” or “beauty” between the 3.0 meter wide windows of the hall floor and to the left and right of the porch porches were created by the sculptor Franz Metzner , with whom Bruno Schmitz had already worked Völkerschlachtdenkmal in Leipzig worked together. The allegorical meaning, however, seems to be more advanced. Hans Schliepmann sees the “atlantic figures in the above-mentioned relief fillings” in the magazine Deutsche Kunst und Decoration merely as an expression of the abundant force of carrying, counter-lifting ”, the artist wants“ to express the conflict between support and load through the physical, through muscle play ”. A few years later, in the special edition of the Berliner Architekturwelt on the 55th birthday of Bruno Schmitz in 1913, he again emphasized the importance of the Rheingold facade, on which a “new decorative motif, the purely decorative use of human forms” appeared and shaped the audience for the first time for this the term "muscle ornament".

As a consequence of the restriction of use to a pure catering business, the terrace turned out to be considerably larger than the original designs. In particular, the subsequently attached tent roofs - already shown in the drawing of the facade - impair the view of the front in the narrow Bellevuestrasse.

Pillar hall

The pillar hall covered the majority of the ground floor with around 700 m². The first room on the ground floor of the hall building accommodated the visitors' cloakroom and provided access to the other rooms of the Rheingold wine house. At the two main entrances on Bellevuestrasse at the head ends of the hall, it was enclosed by two symmetrical three-armed staircases that led to the upper rooms of the wine house and expanded the room by two galleries about halfway up. In the middle of the hall stairs led to the rooms of the connecting building.

Four rows of pillars divided the room, which was 5.2 meters high compared to the area, into a wider central nave and two narrower aisles each. The pillars were part of a pillar system that ran through the entire building on Bellevuestrasse and supported the floor of the Kaisersaal on the hall level.

Between the outer rows of pillars and the outer walls, 3.2 meter high wooden panels separated bunk- like areas. The pillars and walls were clad in deep brown rosewood , in places with decorative inlays of other exotic woods. These cabinet-making work was supplied by the company Kimbel & Friederichsen , purveyor to the imperial court. The “masterful carvings” in the bunk walls, which “ contain Bacchian motifs”, as well as the bronze reliefs on the pillars were created by the sculptor Hermann Feuerhahn . The light gray spotted plaster ceiling stood out effectively against the deep brown of the wood. The large windows facing the terrace illuminated the room and could be sunk into the ground in summer. In the dark, candle-shaped sconces and rows of incandescent lamps on the ceiling created “a lavish flood of light”.

Cloakroom vestibule

The hall above on the cloakroom level took up the entire floor with the exception of the stairs and the toilet facilities accessible from the stairwells. In the original plans, the room was supposed to be the cloakroom for concert-goers as a foyer , but could also perform the same function for banquets in the large banquet hall on the same floor. After the planning change, Aschinger set up a café and an Americain bar there. Because of its subordinate purpose in the original planning, the huge room was only 2.80 meters high. Like the pillar hall, four rows of pillars structured the room, which supported the floor of the imperial hall. Greek cipolline marble with Skyros marble inlays clad the pillars and marble tiles covered the floor. The marble stairs from the pillar hall ended at the head of the huge room. They continued in four single-flight staircases on the long sides that ended under the side galleries of the Imperial Hall.

Imperial Hall

On the hall floor - 9.45 meters above the level of Bellevuestrasse - was the "Kaisersaal", which was the "crowning part of the entire building complex". The largest room in the house, 17.46 meters wide and 35.0 meters long, was originally planned for concerts and events. After the concept change imposed by the construction police, it served as a restaurant with over 1000 seats.

A barrel vault structured by large, flat cassettes and belts made of gilded stucco spanned the length of the approximately 11.2 meter high hall and protruded far into the steel structure of the roof structure. With a view to using it as a concert hall, Bruno Schmitz chose a double construction. An outer, fireproof brick shell was hidden behind the visible inner shell made of wire plaster. Numerous openings in the inner ceiling let the sound enter the cavity between the ceilings, which should serve as a resonance body. The exhaust air also exited through the same openings. Two rows of five large metal chandeliers and colored crystal glass in medieval shapes hung from the ceiling.

The vaults above the arched windows were not cut into the main vault, as is customary, as stitch caps . Only the girders of the barrel vault continued to the pillars, while the wall surfaces were raised vertically above the incised vaults and covered horizontally. Schmitz designed the wall surfaces with expressive keystones , flanked by two gusset medallions with figures of knights - both designed by Franz Metzner.

On the hall floor, a corridor surrounded the “Kaisersaal” on all four sides. The stairs from the cloakroom vestibule and the stairwells on the front and courtyard side led into it on the long sides. The lower narrow sides also accommodated side rooms such as toilets or the buffets for the restaurant. On the loft floor, 3.65 meters higher, the “Kaisersaal” expanded on the long sides to include these areas, while the gallery protruded about one meter into the hall. The gold-colored balustrade of the gallery was structured as balusters by bronze knight figures.

On the two narrow sides, there were two niches vaulted with a barrel vault, which accommodated an orchestra box at the height of the top floor. The gold mosaics in the orchestral niches with the four huge heraldic eagles were supplied by Puhl & Wagner from Berlin-Neukölln . There was space for two side rooms against the courtyard. Their counterparts on the top floor were used to store the instruments, matching the neighboring orchestra boxes.

Four imperial figures - Charlemagne and Otto the Great as well as Barbarossa and Wilhelm I - framed the eastern and western niches on consoles. The figures, other works by Franz Metzner, executed by G. Knodt in Frankfurt, again marked “the extreme limit of an artistic venture without, however, crossing it” for the magazine Der Profanbau . And further: "It looks as if the corpses of Karl and Otto the Great, Friedrich Barbarossa and Kaiser Wilhelm were taken out of the sarcophagi and nailed to the wall up there."

As one of the few rooms in the house, the room was given a parquet floor . The lower wall surfaces were covered by large slabs of flamed, yellowish-brownish Faune-de-Sienne marble , interrupted by the tall rectangular grilles of the air inlet openings made of chased bronze. The upper wall surfaces were covered with slabs of grayish Napoleon marble, which was named after Napoleon's gray coat .

The formative materials marble, gilded stucco and bronze led to a "truly gigantic or majestic spatial effect" with a "solemn and mystically tinted grandeur". The Deutsche Bauzeitung spoke of "one of the most important hall creations of recent times" and explicitly included in the comparison the "White Hall" of the Berlin City Palace, which was rebuilt between 1892 and 1902 with interruptions by the architect Ernst von Ihne . Aschinger's prestige object could therefore easily compete with the splendor of the emperor's residential palace.

The grand piano on Potsdamer Strasse

Facade on Potsdamer Strasse

In contrast to Bellevuestrasse, Bruno Schmitz only had limited design options for the facade on Potsdamer Strasse, as the old house could only be partially demolished because of the tenants. The redesign was limited to the new building area, i.e. the lower left part of the facade up to the second floor and the area above the passage to the courtyard.

Schmitz used elaborate and colored materials such as bronze, copper and marble to separate the facade part of the wine house from the rather neutral facade with its rows of windows and simple plastering. Eleven meters high pillars clad in green, flamed white marble framed the entrance to the Rheingold wine house and the passage. The marble for the pillars extending from the ground floor to the second floor was supplied by the Kiefer joint stock company in Berlin. Above it, on a cornice approximately 1.1 meters wide, the copper inscription "RHEINGOLD", which ran along the entire length of the facade of 22.5 meters, advertised the restaurant. Bruno Schmitz dissolved the area between the pillars into large windows with bronze frames and narrow bars, stepping forward like a bay window above the entrance . New for Berlin was the double elevator system that transported guests directly to the second floor on the left and right in front of the recessed entrance.

The architecture critics and journalists regarded this facade in 1907 as provisional and born of necessity. Hans Schliepmann even defends the architect with the words: "Even a god could not have created a work of art from a house like this, where the most hideous company signs have unfortunately only too well-documented a right to scream for years." , certainly also as a result of the lack of economic success. Outwardly, this facade differed little from the numerous renovations after the turn of the century, where old houses for shops were given modern facades on the lower floors, even if in this case a new building was actually hidden behind the facade. The architectural historian Julius Posener sees parallels between this facade on Potsdamer Strasse and the facade of the bentwood company Jacob & Josef Kohn at Leipziger Strasse 40 designed in 1906 by the Austrian architects Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser .

Shell Hall

The Muschelsaal was 2.2 meters below the level of Potsdamer Strasse. The 7.65 meter wide and 17.28 meter long hall was at the rear of the wing. The visitors reached it via a wide staircase framed with gold mosaics from the gallery hall or via the passage that led to the “stone hall” in the connecting wing. According to the location in the foundations of the building, Bruno Schmitz chose heavy structures. A large barrel vault placed directly above the marble mosaic floor supplied by Johann Odorico spanned the room lengthways and reached a height of about 3.7 meters at the top. The tongue walls and windows that cut into the side of the vault exposed the heavy vault as a wire plaster construction. The windows could be completely sunk into the floor and, in warm weather, extended the hall to the artistically designed courtyard. A simple, small wall fountain made of polished limestone on the final rear transverse wall was the only sculptural decoration of the room. Behind it there was a ladies' toilet and a side staircase. The hall got its name after the shells that clad the vaults and walls together with greenish and brownish-red shimmering glass panels. These incrustations were carried out by the Munich-based company C. Ule , the steps and the marble plinths of the walls were supplied by the Aktiengesellschaft für Marmorindustrie Kiefer in Berlin. The barrel vault with the incrustations rising directly from the ground reminded the critics of a grotto of a pleasure palace from the 17th or 18th century, but the heaviness of the architecture also of a crypt or a dungeon . The “cool gold glittering splendor, originating from the colored glass rivers” with its “fairy tale magic” could also be associated with “Gnome King's Throne Room” from Peer Gynt .

Vestibule on Potsdamer Strasse

The vestibule extended over all three floors used by the Weinhaus in the front building on Potsdamer Strasse. There were several possibilities for visitors to get into the halls of the wine house. What was new in Berlin was the double elevator system mentioned in the description of the facade, supplied by the Carl Flohr machine factory in Berlin, which transported guests directly from the street to the two upper floors. When visitors entered the house through the revolving door, an elegantly curved staircase opened up the upper floors. A mosaic floor covered the floor on the first floor, walls and stairs were clad with walnut and divided into squares by lighter wood.

Gallery room

The first restoration room that visitors entered from Potsdamer Strasse was the “gallery room” on the ground floor. In keeping with its importance as an entrance hall, the 7.92 meter wide and 19 meter long hall with a height of around 7.4 meters extended through two floors. The 4.5 meter high gallery, accessible only from the vestibule and not from the room itself, gave the hall its name. Schmitz designed the interior of the hall with wood, carried out by the cabinetmaker Otto Salzmann & Sohn in Berlin-Kreuzberg . The polished, dark brown-red rosewood of the walls with inlaid inlays made of multicolored woods and mother-of-pearl contrasted with the lighter, flamed birch wood that clad the wooden pillars and the smooth parapets of the gallery and the ceiling. Gilded reliefs by Hermann Feuerhahn provided the pillars with rather discreet sculptural jewelry. Glazed walls separated the gallery from the hall and protected the guests seated upstairs from smoke and drafts. A staircase made of dark marble formed the rear end of the room, which contrasted effectively with the gold mosaics on the walls and stair stringers carried out by the Johann Odorico company . The middle staircase led down to the "Shell Hall", the two outer flights of stairs up to the "Mahogany Hall". Etched yellow windows adorned with flower garlands gave "the hall a mood that could not be imagined more sympathetically".

Mahogany hall

The subsequent "Mahogany Hall", 1.84 meters above the level of Potsdamer Straße, could be reached from the gallery hall via a two-flight staircase. The connection to the rotunda of the connecting building was at the same level. The hall got its name from the dark, burgundy-colored wall and ceiling paneling made of mahogany , manufactured by the W. Kümmel furniture factory in Berlin. Wall pillars with volute capitals structured the 7.92 meter wide and approximately 27 meter long room by separating 4.8 meter wide niches at windows on the long sides. The central decorative element was a life-size wooden relief Franz Metzner at the rear narrow wall of the room, accentuated by a preceding that dais . It showed the "love life of the sexes, marked in such a way that the voluptuous woman on bird's claws, and the horny man stalking on goat feet, sits in front of it, a phantom of common ugliness, a child of sin." Hermann Feuerhahn was also involved in decorating the room involved with the “poetic symbols” on the ceiling and the “exotic representations” on the longitudinal walls.

Ebony hall

The “Ebony Hall” stretched on the cloakroom floor almost the entire length of the wing on Potsdamer Strasse. The excess height of the gallery room with its gallery on the ground floor meant that the overlying half of the ebony room was around 1.8 meters higher than its equivalent above the mahogany room. The two halves of the hall, which are 3.6 and 3.9 meters high, also slightly different in height, were connected by a wide staircase. The main access to the hall was via the vestibule on Potsdamer Strasse and the lower rotunda, but it could also be reached from the gallery of the gallery hall via two flights of stairs. Pillars protruding into the room, clad with Indonesian ebony made of Makassar , separated berths 4.8 meters wide and divided the elongated room. In the “Ebony Hall” Schmitz did without a sculptural design, the “unspeakable nobility” of the hall was shaped by the pillar and wall cladding made of the noble Makassar ebony “of a strangely warm and soft tint”, the ceiling in silver crest painting and the elaborate candlesticks Baccarat crystal factory . The Georg Kuhnert company in Berlin carried out the cabinet-making work.

The connecting wing

The connecting wing connected the hall building on Bellevuestraße with the wing on Potsdamer Straße. It led in the central axis of the hall to the wing on Potsdamer Strasse, with a rotunda mediating between the various axes. The ground floor was raised by half a storey compared to the tracts on the street in order to allow the passages required by the building authorities to cross the connecting wing twice and still give visitors a continuous storey from Potsdamer to Bellevuestrasse. The wing was used exclusively for gastronomic purposes and had its own kitchen on the top floor to supply its restaurants.

Located inside the property, its facades facing the three adjoining inner courtyards were simply designed and corresponded to the rear facades of the street wings. The floors of all courtyards were covered with non-slip corrugated tiles and the courtyard facing the Grand Hôtel Esplanade was designed with lanterns with elaborately designed masts, as it served as an extension of the adjoining halls to the open air in warm weather. Potted plants such as date palms and laurel trees greened the courtyard.

Stone hall

The “Steinsaal”, also known as the “Wotansaal” or “Odinsaal”, was 2.20 meters below the level of Bellevuestrasse. It could be reached via a staircase from the “pillar hall” of the main building on Bellevuestrasse and had a connection to the “Muschelsaal” of the wing on Potsdamer Strasse via the rotunda. The lower hall height of around 3.7 meters and the thicker walls, which had to take the weight of the halls above, prompted Bruno Schmitz to use heavy vaults. The vault, which seemed to grow straight out of the ground, rested on gigantic mythical heads in front of the belts of the vault. Metzner also created similar heads for the crypt of the Monument to the Battle of the Nations in Leipzig. The heavy, massive construction was only pretended, however, a wire plaster construction was hidden behind it. The vault and wall surfaces were covered with incrustations made by the Johann Odorico company with geometric ornaments made of gray Danube pebbles pressed into the cement and darker pieces of slate . This design was based on the cave architecture of the Renaissance and Baroque , but was also reminiscent of Moorish surface decorations. Numerous incandescent lamps embedded in the vault between the patterns formed a kind of starry sky. The artistically designed marble mosaic floor was also supplied by the Johann Odorico company . The large arched windows, which can be lowered into the floor, could be opened to the artistically designed courtyard in summer.

Red hall

The “Red Hall” on the ground floor, another elaborately designed transition room, was 1.85 meters above street level on Bellevuestrasse. The approximately four meter high room got its name from the wall coverings made of red silk or red velvet between the articulating pillars made of reddish padouk wood . A gold or silver ceiling with fairytale motifs spanned the room. The room received subdued light from two glass windows designed by the painter August Unger, executed by the glass painting studio August Wichmann in Berlin. In keeping with the originally planned use as a concert hall, they showed allegories of the musical tempos Adagio and Andante as well as Allegro and Furioso .

A two-flight staircase led to the lower “pillar hall” in the main building, into which it protruded into the middle of the long side. On the platform of the staircase and clearly visible from both sides, the “Rheingoldbrunnen” rose as the “showpiece of the complex”, as the “main symbol of the house”. The sculptor Franz Metzner modeled the three Rhine daughters standing on the edge of a green marble bowl, holding the Nibelungen hoard in their raised hands . Like other works by Metzner, his mermaids moved far away from current academic ideals of beauty after the turn of the century. The critic Maximilian Rapsilber attested the “cool-hearted, bitter, angular mermaids” a “truly terrifying highness, so that no mortal would cherish a desire for them”. The bronze statues were cast by the G. Knodt foundry in Frankfurt am Main .

The treasure could be electrically illuminated from the inside and, in conjunction with the jet of water rising from the marble bowl, created effects “as if liquid gold were playing a game of flames”.

Onyx Hall

The "Onyxsaal" got its name from the wall panels made of onyx marble that covered the walls and pillars. The 230 square meter rectangular room was four meters high, and the supports, designed as tongue walls for the “banquet hall” above, formed five niches on each of the long sides. While on the western side all the niches accommodated large, narrow-framed windows, three niches on the eastern side were followed by passages to an adjoining room. The food from the kitchen in the attic reached the restaurant in twelve dining elevators and one freight elevator. The pictures from the opening year show around 50 tables, each set for four people.

The large, light greenish-yellow onyx slabs from the Pyrenees contrasted effectively with their dark bronze borders. A bronze frieze - alternating punched-out squares in which the stone was visible, and bronze squares filled with simple patterns - separated this area from the upper wall zone. The long sides of the support pillars were covered by stucco reliefs by the sculptor Hermann Feuerhahn on the subject of "Poetry of the Seasons" with spring , summer , autumn and winter as well as depictions of the four elements fire, water, air and earth and the emblem of the Rheingold wine house. On the front side, lighting fixtures made in bronze, together with two square silver chandeliers from the Lorraine crystal manufacturer Baccarat, provided atmospheric lighting. The upper part of the walls and the ceiling were kept in a light yellow stone tone.

After the rather dark, partly windowless and therefore only artificially lit rooms that visitors had passed through to the “Onyx Hall”, the room appeared bright and cheerful because of the light materials and the good lighting through the large windows and numerous lamps. The magazine Der Profanbau spoke of “glistening glory” and “champagne mood”.

Banquet hall

The largest hall in the intermediate wing was the "banquet hall" on the cloakroom floor, 6.25 meters above the level of Bellevuestrasse. It was connected to the “pillar hall” of the main building via an anteroom, in which a staircase each left and right of the passage led to the galleries of the “banquet hall”. At the other end of the hall, the visitors came to the rotunda.

In the longitudinal direction, a ceiling in the form of a barrel vault arched over the two-storey space. Laterally, the stab caps cut into the main vault above the high arched windows, the apex of which was 9.2 meters above the ground. Rather flat stucco work in shapes reminiscent of the Baroque covered the gray and white plastered ceiling.

Up to the beginning of the vault, almost black water oak covered the walls in plain, simple shapes. Bruno Schmitz also chose the same wood for the balconies of the galleries with their simple, compact balustrades that stretched between the pillars. The upper wall surfaces were kept in a light yellow stone tone.

The entrance areas on the narrow walls comprised portal-like fixtures made of gray, lively flamed Swiss Cipollino , "whose quarries were only reopened two years ago". Hermann Feuerhahn's bronze relief Hagen with the Rhine daughters was set above the passage on the gallery in the direction of the rotunda . Brünhilde's magic fire adorned the passage towards the main building . Both reliefs were made by G. Knodt in Frankfurt.

The room received its light during the day through the numerous windows, which were composed of different colored rectangular pieces of glass, some with figurative representations. In the dark, two lights per cap and sconce on the pillars illuminated the hall.

rotunda

The rotunda, a multi-storey cylindrical structure with a radius of 6.15 meters, connected the intermediate tract with the tract on Potsdamer Strasse as a hinge and, with its round floor plan, mediated between the acute-angled wings.

On the level of the kitchen floor, already 1.75 meters below the level of Potsdamer Strasse, a passage crossed the rotunda. It led from the farm yard on Potsdamer Strasse into the courtyard inside the property, whose fire wall against the Grand Hotel Esplanade was artistically designed. However, the 3.2 meter high room was only used as a passage in exceptional cases. Mainly he connected the “Muschelsaal” in the wing on Potsdamer Strasse with the “Wotansaal” in the intermediate building. The difference in level to these adjoining halls was balanced out by three steps. An exit also led to a staircase that opened up all floors of the intermediate building.

The lower rotunda on the ground floor was also designed as a transition room. On the one hand, the 4.0 meter high room connected the "Onyx Hall" in the intermediate building with the "Mahogany Hall" in the wing on Potsdamer Straße. On the other hand, two curved stairs led along the outer walls to the cloakroom. The stairs began in the “mahogany hall” and were only visible in the rotunda behind a decoratively treated slat made of almost black water oak. The flights of stairs also covered the two windows, so that the lower rotunda only received subdued light from the stairs with their latticework. The Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung reported on "strange [r] geometric [r] painting of the plastered surfaces, which is reminiscent of fabric covering" and the red-black ceiling also matched the room, which is characterized by the strong contrast between the colors.

The rotunda housed a restaurant on the cloakroom floor where the flights of stairs ended. Based on the design of the adjoining “Ebony Hall” in the wing on Potsdamer Strasse, the 3.6 meter high room was given ebony walls. The silver-gray ceiling was covered with a pattern of comb plaster slightly raised with paint. In the direction of Bellevuestrasse, the “banquet hall” followed. Two windows lit the almost “serious, monumental” room.

The “Blue Rotunda” on the hall floor was reached by visitors either from the gallery of the “Banquet Hall” or via the staircase adjoining the rotunda. Since there were no other halls in the wing on Potsdamer Strasse, only a kitchen, the room had no function of passing through. Bruno Schmitz designed a “room intended for special little festivities”.

Circumferential pillars divided the two-storey, 7.6 meter high room, which was covered by a blue painted flat dome with a large gold rosette. The eight white marble pillars ended in huge human heads, crowned by electric lights. They carried a gallery about three meters high. The parapet was decorated with a saying by the writer Emil Jacobsen :

A gift from God is joy to us,

no one disregards it!

To protect us and ref> Julius Posener: Berlin on the way to a new architecture: the age of Wilhelm's Trutz im Leide -

joy is a serious thing!

Jacobsen also wrote the sayings and verses that adorned the walls in decorative fonts in the other rooms, such as the “pillar hall” in the hall building. The dome, the wall surfaces and the parapet were designed by the painter August Unger. The room “in subdued blue-green lighting” reminded the Bauwesen magazine of a “prehistoric temple of idols”, while it had “the mysterious demeanor of a temple of Isis” for the magazine Der Profanbau .

Ancillary and utility rooms

The expensive property required the greatest possible utilization, as far as the building regulations permitted. The area provided for the restoration rooms roughly corresponded to the area of the ancillary and utility rooms combined. Most of the ancillary and utility rooms were located in the basement and attic storeys, which were not very attractive for customers. In order to cover this huge space requirement, the Rheingold wine house was one of the first large buildings in downtown Berlin to have two fully usable basement floors.

The floor of the lower basement was 5.50 meters below street level, the groundwater level was 3.15 meters, which means that the basement was 2.35 meters in the groundwater. At the bottom, a 90 centimeter thick, partly iron-reinforced concrete slab sealed with a 20 millimeter thick insulating layer made of three layers of glued bitumen cardboard with a coating of hot goudron mass . The similar bitumen cardboard insulation, raised up to 30 centimeters above the groundwater level on the side walls, sealed against the groundwater penetrating from the side.

The basement rooms extended to the property boundaries. In addition to the cold storage rooms, the lower basement mainly accommodated ancillary rooms with technical equipment such as the boiler room for the heating, the pump room or the oil room for the generators. The engine room facing Potsdamer Strasse, the 28-meter-long and 4.50-meter-wide machine foundation of which was a further 1.4 meters lower than the floor of the basement, reached down to the second basement floor, referred to as the kitchen floor in the plans. The three courtyards, recessed opposite street level, cut into the kitchen floor. The area under the wing on Bellevuestrasse was shared by the main kitchen of the wine house and the wine cellar, which held seven million bottles of wine.

Kitchens

The Rheingold wine house had three kitchen systems, one for each component. The kitchen for the construction on Bellevuestrasse was on the kitchen floor below the restaurants to be supplied. The largest kitchen facility in the house, well equipped with eleven cooking machines , six large pressure cookers, numerous grills and heating cabinets, extended over around two thirds of the floor area under the hall. It also took on special facilities, such as the pastry shop and the copper and silver washing rooms. 25 dining elevators, some of which are heated with electric heating coils to prevent the food from cooling down, transport the food to the various restaurants in the wing on Bellevuestrasse, such as the “Kaisersaal”. The kitchens of the Rheingold wine house employed 137 people in the opening year, 70 of whom worked in the main kitchen. The kitchens for supplying the halls in the connecting building and in the side wing on Potsdamer Straße were located above the associated restaurants in the attic and on the hall floor, with which they were also connected by dining elevators. Corresponding to the smaller halls and the smaller number of guests, they were hygienically equipped with white-tiled walls, pillars and ceilings, like the main kitchen, while the floor was covered with smooth, light-colored tiles.

Cold rooms

The seven main refrigeration rooms for storing perishable foods such as meat, fish, poultry, butter, cheese and vegetables together covered an area of around 160 m² in the basement. The daily requirements of the three kitchens were stored in ten additional cold rooms, each with an area of 15 to 20 square meters, in the kitchens themselves. Impregnated cork panels insulated the cold rooms from the environment. Its walls, ceilings and floors were lined with white tiles. The cold was produced by a compression refrigeration machine supplied by August Borsig in Berlin-Tegel , using sulfur dioxide as the refrigerant . A pipe system with a cork coating distributed the brine, cooled to −12 ° C, from the basement to the various cold rooms, the temperature of which was set between +2 and +6 ° C depending on the type of food. The cooling machine also produced two tons of ice a day for the needs of the various restaurants in the wine house.

Steam laundry

All laundry in the house was washed and ironed in our own steam laundry. The used table linen reached the laundry collection point in the basement via litter chutes in the dining rooms. From there it went to the laundry room and the associated laundry store on the third floor of the side wing on Potsdamer Strasse at the height of the gallery. The technical equipment for the rooms clad with white tiles was supplied by H. Timm in Berlin, including four large washing drums , three laundry centrifuges and two ironers . The steam required for operation was supplied by the low-pressure steam boilers in the boiler room in the basement.

Technical facilities

The size of the wine house made special demands on the technical equipment. In addition, there was the cellar located deep in the groundwater and the client's wish to operate the house as independently of external influences as possible. For economic reasons, the operating costs should be kept as low as possible - rough calculations, for example, put the annual costs for electric lighting alone at around 55,000 marks. Therefore, the Rheingold wine house had its own well and generated the electricity itself, with the waste heat from the generators also being used to heat the water.

Electrical systems

The electricity for the 5212 tantalum lamps , 544 carbon filament candle lamps and the 51 arc lamps as well as for the operation of the numerous pumps, fans, passenger and goods lifts as well as the ice machines were produced by three direct current shunt dynamo machines, each with 204 kilowatts of power , each directly with were coupled to a diesel engine. The lighting system and the generators were manufactured by Siemens-Schuckert-Werke GmbH in Berlin. The Maschinenfabrik Augsburg delivered the three four-cylinder diesel engines of 300 hp , running at 175 rpm. The machines were housed in the machine cellar under the wing on Potsdamer Strasse. The eight meter wide, 35 meter long and five meter high room was 5.5 meters below street level, but received direct daylight through a two meter wide light shaft on the long side. The 13 cubic meter fuel tank was located directly next to the machine cellar under the courtyard entrance. The electrical systems also included the accumulator battery consisting of 125 elements , housed in two basement rooms, each with an area of 60 square meters, one above the other. Connected in parallel to the machines during operation, they compensated for voltage fluctuations in the generators and the line network and were able to supply the house with electricity for almost three hours after the machines failed. This system was supplied by the Akkumulatoren-Aktien-Gesellschaft in Hagen . The electrical lines, with a voltage of 220 volts , were visible on rollers in side rooms such as kitchens, basements or in the attic above the plaster.

Cold and hot water systems

Two deep wells on the property on Potsdamer Strasse pumped groundwater from a depth of 48 meters. An electrically operated high-pressure centrifugal pump with a delivery rate of 1200 liters per minute pumped the iron-rich water, as in the entire Berlin area, through an iron removal system in the attic to the two cold water tanks above, each with a capacity of eight cubic meters. From there, it was distributed throughout the house. A second pump served as a reserve and a floating contact device interrupted the delivery of the pump when both containers were full. If the self-produced amount did not meet the demand, water from the city network supplemented the demand.

As an early example of combined heat and power, the cooling water of the large diesel engine system was used to generate hot water . The water was heated to around 80 ° C and flowed into two galvanized hot water reservoirs with a total of 60 cubic meters in the basement. From there, a high pressure centrifugal pump pumped the warm water to the hot water tanks in the attic. The cooling water did not cover all the demand - the rest of the hot water was supplied by a conventional boiler in the boiler room under the courtyard on Potsdamer Strasse.

drainage

The deep location of part of the basement below the level of the municipal sewer required special precautions. On the one hand, it was not possible to derive it via the natural gradient, on the other hand, the canal on Bellevuestrasse, which was quickly overloaded in rainy weather, threatened to flood the large kitchen in the underground kitchen level due to backwater.

If the automatic backflow flaps closed when the municipal sewer system in Bellevuestrasse was overloaded, the wastewater generated in the house flowed as an overflow via emergency pipes that were higher than the main sewer pipes into a gully . This simultaneously collected the water from the basement areas, which are deeper than the sewer system, such as the overflow water from the hot water tanks or the rainwater that penetrated via the cellar stairs. A centrifugal pump transported the water from the gully into the less congested canal on Potsdamer Strasse. The systems were supplied by Allgemeine Städt-Reinigungsgesellschaft mbH in Berlin.

Heating and ventilation

The boiler room for the low-pressure steam heating was located under the farm yard on Potsdamer Strasse. The coal-fired system consisting of six steam boilers was divided into two groups, of which the larger with four boilers was used exclusively to generate steam for heating. The smaller group with two boilers produced the steam for the kitchens and the laundry room, but had the heating switched on when required.

The heating system was dimensioned in such a way that it only generated around 80 percent of the heat that was required for an internal temperature of 20 ° C. The ventilation provided the rest of the heat requirement. This coupling of the heating with the ventilation meant that the ventilation system also had to be kept in permanent operation. This in turn ensured a sufficient exchange of air in the rooms of the Rheingold wine house.

The restoration rooms had pressure ventilation , where fresh and, if necessary, preheated air was forced into the room - 20 cubic meters per guest and hour. In the kitchens and sanitary facilities, where the air was renewed five times an hour, suction ventilation prevented the spread of bad smells. Three fans in the cellar under the utility yard on Potsdamer Strasse sucked in the fresh outside air. A 40 square meter coke filter built into the courtyard floor freed the fresh air from dust and vermin. In three heating chambers, one for each fan and with different temperatures, the air could be heated by ribbed heating elements. By mixing the warm air of different temperatures, if necessary also with cold air, the air could be set to the desired temperature before it flowed into the rooms via the ventilation ducts. Schmitz cleverly integrated the openings of the ventilation ducts into the architecture of the individual rooms. The entire heating and ventilation system, supplied by David Grove in Berlin, could be controlled centrally from the control room in the basement.

criticism

The main features of the contemporary German architecture press reported positively, sometimes almost enthusiastically, about the new building. The Deutsche Bauzeitung, for example, saw the Rheingold wine house as “one of the most important architectural creations of the present, a work of great success and victorious creative power”. The architecture world in Berlin counted the building with Alfred Messel's nearby Wertheim department store on Leipziger Platz as one of the “best buildings of our time”. The magazine Der Profanbau also saw the Rheingold wine house as the “full-weight counterpart” to Messel's department store construction, which would do the same for the term “Aschinger” as Messelbau did for the “term Wertheim and generally for the ennoblement of the department store”. If the Deutsche Bauzeitung was "not aware of any recent creation from abroad that comes close to the Rheingold", the building, conversely, was not recognized in the contemporary architecture press abroad. The Vossische Zeitung praised the new building in 1907 as a "glamorous New Year's present which the Aschinger Society brings to the capital of the Reich", the Rheingold wine house is "unique and incomparable on the whole earth."

The cultural commitment of the Aschinger corporation also found recognition - sometimes with swipes at the “beer springs”, from which “suddenly fabulous streams of gold for the highest art” flow out - and their choice of Bruno Schmitz as an architect, who “has the tastelessness of a gold-mosaic-bristling, romanizing- Byzantine imperial hall to devour Munich beer and sausages, as we have already had in Berlin, [...] would never have participated.

On the other hand, the discord between the ambitious artistic design of the Rheingold wine house and its rather profane use as a large restaurant met with criticism . The French journalist Jules Huret visited the newly opened house on his trip to Germany in Berlin and asked in his travel report published in 1909:

«Où suis-je? Dans quel château fort teutonique, dans quel cloître géant? Dans quelle crypte bouddhique ou quel Walhalla? Je suis dans un restaurant où la cuisine est mauvaise et où je peux manger à prix réduits. »

"Where am I? In which Teutonic castle, in which huge monastery cloister? In which Buddhist crypt or in which Valhalla? I'm in a restaurant where the kitchen is bad and where I can eat at discounted prices. "

He acknowledged the efforts to create the design with the words:

«N'importe, on ne peut nier qu'il y ait là un effort énorme pour sortir du convenu et du mièvre, effort que je ne pouvais m'empêcher d'admirer, quand je ne songeais pas que quatre mille personnes viennent, entre ces murs de légende et de rêve, s'emplir le ventre. »

“Nevertheless, one cannot deny that there is a tremendous effort here to get away from the conventional and the thread. An effort that I could not refuse to admire when I was not just thinking that 4,000 people would come into these walls of legends and dreams to fill their stomachs. "

As early as 1909, in the 43rd volume of the series Famous Art Places, the art critic Max Osborn mentioned the Weinhaus Rheingold, “its solemn front (with relief figures by Franz Metzner) and magnificent, albeit excellent interior fittings with excellent treatment in real materials is not in line with the profession of the house ”.

Some of the contemporaries were bothered by Franz Metzner's non- naturalistic , ornamental handling of the human body. The Deutsche Bauzeitung reported that “his conception of art encountered the strongest contradiction of traditional taste”. If the Zentralblatt of the building administration showed understanding for “a certain uncomfortable feeling” that the “raped body” created, the other specialist critics distanced themselves from it. The later first Federal President Theodor Heuss , at the time a critic of the Neudeutsche Bauzeitung, wrote : “I don't mind the fact that the men who were formed in wood or other material on the pillars and wall cladding are beheaded and at least fragmentary and questionable replacements "He praised Schmitz's efforts to revive the" sculpture in architecture "in the external design of the building and in the large rooms of the Rheingold wine house, especially the" Kaisersaal ". For the smaller cabinets and halls, on the other hand, “the monumental sculpture acts violently and as a burden” and the “excessive size of the sculpture” crushes the space.

The architectural historian Julius Posener also compared the Rheingold wine house with Messel's Wertheim department store in 1977 in his publication Berlin on the Way to New Architecture 1889–1918 . He attested the Rheingold façade to be of superior quality and greater modernity - “Only Messel's Leipzig street front was on the path that continued. The Rheingoldfront represents the most beautiful expression of an achieved state of art, so it is more at the end of a path. "

Aschinger's prestige property is not profitable

The euphoria of the group after the opening on February 6, 1907 quickly gave way to worries about problems in the operational processes and the lack of cost recovery at the Rheingold wine house. As early as July 1907, Carl Aschinger asked his brother August to re-enter the operative business, although as a supervisory board member of the Aschinger stock corporation he was only supposed to perform supervisory and representative functions. August Aschinger noted in a note that the "financial side of the Rheingold [...] was simply impossible economically" and "in fact had eaten up the other businesses". "Getting this house operational was the greatest task of my life." Problems caused, for example, the oversized expansion of the Rheingold wine house. The food cooled down on its way to the guests despite the electrically heated dining lifts. If more than 3,000 guests visited the restaurant, the kitchens reached their capacity limits. Long waiting times and lukewarm or even cold meals were not a good advertisement for the Aschinger Group's showpiece and not a good basis for building up a customer base. By installing additional kitchens and utility rooms in 1907, probably coupled with improvements in service , August Aschinger was able to solve the problems in the operational processes.

The earnings situation remained poor, however, and sales hardly covered the running costs. With this poor earnings situation, the high investment costs for the property and the building did not pay off. The original calculation of the catering business was already out of date when the Rheingold wine house opened as a result of the change in use ordered by the building authorities and the one million marks in building costs. There Aschinger had calculated "with slightly higher wine prices" with "cheap [n] and good [n] food portions at the basic prices of M. 0.80 and M. 1.30" and 3800 seats. The weak return on sales of the Rheingold wine house within the Aschinger Group is exemplified by the figures from January 1911. The 30 “beer sources” achieved a profit of 160,000 marks on sales of 1.1 million marks and thus a return on sales of 14.6 percent. The Weinhaus Rheingold, on the other hand, achieved a profit of 15,000 marks with a turnover of 300,000 marks and thus only five percent return on sales, i.e. around a third. The group had invested better in the nearby Hotel Fürstenhof on Potsdamer Platz, where profitability reached 22.2 percent based on a profit of 30,000 marks with a turnover of 135,000 marks.

The obituary for Carl Aschinger in the Deutsche Gastwirthe-Zeitung on May 8, 1909 gives a picture of the continued lack of success of the Rheingold wine house. There were no consistently high numbers of guests and the occupancy rate was only reasonably satisfactory on Sundays, so that most of the halls were closed during the week. The kitchen and cellar were “not up to par” and lagged behind the competition. The restaurant, built with such high standards, was unable to win over the Berlin middle or upper classes as regulars and became a tourist bar. In 1909, Grieben's travel guide to Berlin and the surrounding area recommended the Rheingold wine house as a “highly elegant wine and beer restaurant”. In 1910 , Baedekers Berlin and the surrounding area classified the bar under the “not so demanding” wine restaurants, but mentioned “the splendidly furnished Rheingold wine house, built by Bruno Schmitz, with sculptures by F. Metzner” on the tour of Potsdamer Platz. As a tourist attraction with insufficient profitability, the Weinhaus Rheingold remained an economic mistake of the otherwise successful Aschinger Group.

Interwar period

In the economically difficult times after the First World War , the group considered selling the Rheingold wine house in 1919. But the sales plans already approved by the supervisory board, which were supposed to bring in 15 million marks, came to nothing. In the Empire modern equipment the Weinhaus Rheingold with their Jugendstilanklängen was considered out of date after the end of World War II. At the beginning of the 1920s, Grieben's travel guide noted evening concerts, and from 1922 dance and cabaret events were supposed to increase the attractiveness of the restaurant. Success was still a long time coming and in 1928 the group's board of directors was resigned to the fact that the Weinhaus Rheingold “does not even come close to covering its costs, let alone earn it.” With the global economic crisis, the situation worsened in 1930, because of the collapse Income, the cross-subsidization of the Rheingold wine house by other Aschinger companies ceased and the group ran into serious financial difficulties in 1931. The Rheingold wine house remained completely closed in 1931/1932 and was no longer mentioned in Baedeker's Berlin and the surrounding area in 1933. From 1935 onwards, the catering of the numerous tour groups who traveled to Berlin with the organization “ Kraft durch Freude ” and events organized by patriotic associations brought somewhat better capacity. During the Second World War , the Rheingold wine house served as accommodation for the troops, but operations had to be stopped in the winter of 1940 due to a lack of coal.

Sale and Destruction

In January 1943, a report in the Berliner Börsen-Zeitung about the Aschinger company's plans to sell the Rheingold wine house aroused the interest of several Reich ministries. The property was close to the new, prestigious north-south axis in Albert Speer's plans for the world capital Germania . In the files of the former Aschinger Group, kept in the Berlin State Archives , there is a preliminary contract with the Ministry of Finance, which set the sales price at six million marks . In 1943, the Deutsche Reichspost finally won the bid . The building suffered severe damage in a bombing raid in the same year, and the inventory of the wine house, valued at 250,000 Reichsmarks, which was stored when it was sold, was burned in an attack in spring 1944.

The map of the building damage from 1945 showed the building as “damaged but rebuildable”, but the ruins of the Rheingold wine house were quickly removed in the first post-war years. Photographs show the cleared property as early as the early 1950s. After the construction of the Berlin Wall in 1961, Linkstrasse, which had been extended to Bellevuestrasse to bypass the inaccessible Potsdamer Platz, ran across the wasteland. Potsdamer Strasse, which was converted in 1966 for the new building of the West Berlin State Library , also ended in this extension , also over the site of the former Rheingold wine house.

With the redevelopment of Potsdamer Platz after German reunification , the situation changed again. While the extension of Linkstrasse was canceled, Potsdamer Strasse, which runs through to Potsdamer Platz, divides the property. The BahnTower stands roughly at the site of the hall building on Bellevuestrasse, while the Kollhoff Tower on the opposite side takes up the area of the former front building on Potsdamer Strasse.

literature

- Alexander Koch: Professor Bruno Schmitz 'House Rheingold Berlin. (Koch's Monographs XIII), Alexander Koch publishing house, Darmstadt, no year (1907).

- Brüstlein: The Rheingold Wine House in Berlin. In: Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung. 27th year 1907.

- Karl-Heinz Glaser: Aschinger's “Bierquellen” conquer Berlin. From the wine town of Oberderdingen to the up-and-coming capital. Verlag Regionalkultur, Heidelberg 2004, ISBN 3-89735-291-5 , pp. 83-99.

- Hermann Hinderer: Rheingold Wine House. In: The builder. 5th year 1907, issue 7, pp. 73–84, pp. 87–91.

- Karl-Heinz Hüter: Architecture in Berlin. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart 1988, ISBN 3-17-009732-6 , pp. 46-48.

- Theodor Heuss : Rheingold by Bruno Schmitz. In: Neudeutsche Bauzeitung. 3rd year 1907, pp. 145–148.

- Leo night light : Weinhaus Rheingold in Berlin. In: Berliner Architekturwelt. 10th year 1907/1908, issue 1 (from April 1907) ( digitized 13 kB), pp. 5-40.

- Julius Posener : Berlin on the way to a new architecture: the age of Wilhelm II. Prestel, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-7913-0419-4 , p. 85, p. 100-105.

- Maximilian Rapsilber: The Rheingold Wine House. In: Profanbau. 3rd year 1907, pp. 94-100, pp. 105-108, pp. 117-119, pp. 138-143.

- Hans Schliepmann: Bruno Schmitz. (= XIII. Special edition of the Berlin architecture world ) Ernst Wasmuth, Berlin 1913, p. VIII.

- Hans Schliepmann: “House Rheingold” in Berlin. A masterpiece by Bruno Schmitz. In: German art and decoration. Illustrated monthly booklets for modern painting, sculpture, architecture, home art and women's artistic work. Year 1907, pp. 1–60.

- The new building of the “Rheingold” wine house of Aktien-Gesellschaft Aschinger in Bellevue and Potsdamer Strasse in Berlin. In: Deutsche Bauzeitung. 41st year 1907, pp. 85–89, pp. 111–112, pp. 121–125, pp. 257–259, pp. 261–265, pp. 269–273.

- The metalwork in the Rheingold, Bellevue and Potsdamer Strasse wine restaurant in Berlin. In: Bautechnische Zeitschrift. 23rd year 1908, p. 107, pp. 196-200.

Web links

- Design drawings in the architecture museum of the TU Berlin

- Weinhaus Rheingold at potsdamer-platz.org

Individual evidence

- ↑ Hans Schliepmann: Bruno Schmitz; XIII. Special issue of the Berliner Architekturwelt with text by Hans Schliepmann. Verlag Ernst Wasmuth, Berlin 1913, p. VIII.

- ^ Maximilian rapeseed silver. In: Profanbau. 3 (1907), p. 95.

- ^ Jörg Müller: The Potsdamer Platz in Berlin. To the history of a central square. Technische Universität Berlin, Berlin 1990, ISBN 3-7983-1339-3 , pp. 30/31.

-

↑ Bellevuestrasse 19, 19a . In: Berliner Adreßbuch , 1905, part 3, p. 52 (previous owner; 19a: construction site).

Bellevuestrasse 19, 20 . In: Berliner Adreßbuch , 1906, part 3, p. 54 (Aschinger's beer source). -

^ Potsdamer Strasse 3 . In: Berliner Adreßbuch , 1905, part 3, p. 565 (previous owner).

Potsdamer Strasse 3 . In: Berliner Adreßbuch , 1906, part 3, p. 595 (Aschinger's beer source). -

^ Potsdamer Strasse 3 . In: Berliner Adreßbuch , 1937, part 4, p. 661.

Potsdamer Strasse 8 . In: Berliner Adreßbuch , 1938, part 4, p. 679. - ↑ a b c Hermann Hinderer. In: The builder. 5 (1907), p. 73.

- ^ Maximilian rapeseed silver. In: Profanbau. 3 (1907), pp. 139/140.

- ^ Maximilian rapeseed silver. In: Profanbau. 3 (1907), p. 98.

- ↑ a b "Rheingold" house in Berlin. A masterpiece by Bruno Schmitz. In: German art and decoration. Illustrated monthly booklets for modern painting, sculpture, architecture, home art and women's artistic work. Darmstadt 1907, p. 3.

- ↑ a b c The new building of the "Rheingold" wine house of Aktien-Gesellschaft Aschinger in Bellevue and Potsdamer Strasse in Berlin. In: Deutsche Bauzeitung. 1907, p. 110.

- ↑ a b c d e f The new building of the “Rheingold” wine house of the Aktien-Gesellschaft Aschinger on Bellevue and Potsdamer Strasse in Berlin. In: Deutsche Bauzeitung. 1907, p. 262.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Hermann Hinderer, In: Der Baumeister. 5 (1907), p. 74.

- ↑ a b Hermann Hinderer. In: The builder. 5 (1907), p. 78.

- ↑ In contrast to this, the Deutsche Bauzeitung dates the completion of the building to mid-January 1907, cf. Deutsche Bauzeitung , 1907, p. 110.

- ↑ a b c d e E. Carlotta in the fourth supplement of the Vossische Zeitung (no. 1/1907) .

- ↑ a b c Hermann Hinderer. In: The builder. 5 (1907), p. 91.

- ↑ a b c Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung, 27 (1907), p. 199.

- ↑ a b "Rheingold" house in Berlin. A masterpiece by Bruno Schmitz. In: German art and decoration. Illustrated monthly booklets for modern painting, sculpture, architecture, home art and women's artistic work. Darmstadt 1907, p. 8.

- ^ Julius Posener: Berlin on the way to a new architecture: the age of Wilhelm II. Prestel, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-7913-0419-4 .

- ↑ a b "Rheingold" house in Berlin. A masterpiece by Bruno Schmitz. In: German art and decoration. Illustrated monthly booklets for modern painting, sculpture, architecture, home art and women's artistic work. Darmstadt 1907, p. 9.

- ↑ Hans Schliepmann: Bruno Schmitz; XIII. Special issue of the Berliner Architekturwelt with text by Hans Schliepmann. Verlag Ernst Wasmuth, Berlin 1913, p. VIII.

- ↑ a b c d e f g Maximilian rapeseed silver. In: Profanbau. 3 (1907), p. 107.

- ↑ a b c d e “Rheingold” house in Berlin. A masterpiece by Bruno Schmitz. In: German art and decoration. Illustrated monthly booklets for modern painting, sculpture, architecture, home art and women's artistic work. Darmstadt 1907, p. 30.

- ↑ a b c d e Deutsche Bauzeitung 1907, p. 122.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h i j k Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung, 27 (1907), p. 210.

- ↑ a b "Rheingold" house in Berlin. A masterpiece by Bruno Schmitz. In: German art and decoration. Illustrated monthly booklets for modern painting, sculpture, architecture, home art and women's artistic work. Darmstadt 1907, p. 42.

- ↑ Maximilian Rapsilber: The Rheingold Wine House. The secular building 1907, p. 107/108.

- ↑ Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung, 27 (1907), p. 211.

- ^ House "Rheingold" in Berlin. A masterpiece by Bruno Schmitz. In: German art and decoration. Illustrated monthly booklets for modern painting, sculpture, architecture, home art and women's artistic work. Darmstadt 1907, p. 7.

- ↑ Julius Posener: Berlin on the way to a new architecture: the age of Wilhelm II. Prestel, Munich 1979, ISBN 3-7913-0419-4 , p. 99 and 14. Illustration of the facade at Leipziger Straße 40 .

- ↑ Zentralblatt der Bauverwaltung, 27 (1907), p. 198.

- ↑ a b c d Maximilian rapeseed silver. In: Profanbau. 3 (1907), p. 99.

- ↑ a b "Rheingold" house in Berlin. A masterpiece by Bruno Schmitz. In: German art and decoration. Illustrated monthly booklets for modern painting, sculpture, architecture, home art and women's artistic work. Darmstadt 1907, p. 44.

- ^ House "Rheingold" in Berlin. A masterpiece by Bruno Schmitz. In: German art and decoration. Illustrated monthly booklets for modern painting, sculpture, architecture, home art and women's artistic work. Darmstadt 1907, p. 43.

- ↑ a b Maximilian rapeseed silver. In: Profanbau. 3 (1907), p. 142.

- ^ Maximilian rapeseed silver. In: Profanbau. 3 (1907), p. 139.

- ^ Maximilian rapeseed silver. In: Profanbau. 3 (1907), p. 141.

- ^ Maximilian rapeseed silver. In: Profanbau. 3 (1907), p. 89.

- ↑ a b Maximilian rapeseed silver. In: Profanbau. 3 (1907), p. 140.

- ↑ a b Deutsche Bauzeitung 1907, p. 269.

- ↑ Master builder section of the rotunda.

- ↑ a b c d e f g h Maximilian Rapsilber, In: Der Profanbau. 3 (1907), p. 100.

- ↑ a b c d e Maximilian rapeseed silver. In: Profanbau. 3 (1907), p. 106.

- ↑ a b "Rheingold" house in Berlin. A masterpiece by Bruno Schmitz. In: German art and decoration. Illustrated monthly booklets for modern painting, sculpture, architecture, home art and women's artistic work. Darmstadt 1907, p. 32.

- ^ Maximilian rapeseed silver. In: Profanbau. 3 (1907), p. 105.

- ^ Maximilian rapeseed silver. In: Profanbau. 3 (1907), p. 110.

- ^ House "Rheingold" in Berlin. A masterpiece by Bruno Schmitz. In: German art and decoration. Illustrated monthly booklets for modern painting, sculpture, architecture, home art and women's artistic work. Darmstadt 1907, p. 34.

- ↑ a b c “Rheingold” house in Berlin. A masterpiece by Bruno Schmitz. In: German art and decoration. Illustrated monthly booklets for modern painting, sculpture, architecture, home art and women's artistic work. Darmstadt 1907, p. 33.