Algerian war

ثورة التحرير الجزائرية

Tagrawla Tadzayrit

| date | November 1, 1954 to March 19, 1962 |

|---|---|

| place | Algeria |

| Exit | French political defeat |

| consequences | Algeria's independence from France |

| Peace agreement | Évian Agreement |

| Parties to the conflict | ||

|---|---|---|

| Commander | ||

|

|

||

The Algerian War (synonymous French Guerre d'Algérie ; Arabic ثورة التحرير الجزائرية, literally about the Algerian Liberation Revolution ) was an armed conflict over the independence of Algeria from France from 1954 to 1962. It was started systematically by the Marxist-nationalist FLN , which resorted to terrorism . In contrast to the previous Indochina War , the French military succeeded in maintaining the upper hand militarily. However, losses of war and human rights violations including torture made the conflict so unpopular in France that it was ended politically and led to Algeria's independence. As a result, there were unsuccessful coup attempts by high military officials in France and the terrorist organization OAS was formed . The war ended in March 1962 by the treaties of Évian with a negotiated solution, which resulted in the independence of Algeria under the leadership of the FLN.

The war of independence affected large parts of the population of Algeria, with a minority of Muslim Algerians fighting to become part of France. During that time, millions of people were forcibly relocated. The European minority in the country fled almost completely after the country's independence. The war also spread to the motherland in the form of political demonstrations and attacks. After the war there was a power struggle within the FLN, from which the authoritarian regime Houari Boumediennes emerged in 1965. For France, the defeat in the Algerian war meant the end of its colonial empire.

prehistory

French colonization

In 1830 French troops occupied Algiers , Oran and Bône and began to conquer the country. The reason for the war was a diplomatic affair: The Algerian ruler Hussein Dey , nominally subordinate to the Ottoman Empire , hit the French consul with his fly whisk when he refused to repay French debts from the time of the Napoleonic Wars . The motives behind the declaration of war were the hoped-for gain from colonies , the belief in the superiority of one's own social system in the sense of the contrast between “civilization” and “barbarism” and the endeavor of the survived monarchy to gain popularity through the war.

After conquering the northern part of the country, the French National Assembly was divided on how the new area should be integrated into the state . The occupied part of Algeria therefore remained under military rule until 1848. The French troops were able to occupy most of the country by 1870. The unoccupied territory was partially filled by state structures after the French intervention. Ahmed Bey bin Muhammad Sharif , the former Bey of the region, tried to build an own state based on the Ottoman model in eastern Algeria. Abd el-Kader , a descendant of a family of religious notables, established a tribal theocracy in western Algeria. During this phase there was constant fighting due to rebellions of the local population against the French colonial power that flared up again and again in different regions . Abd el-Kader achieved national fame as a pioneer against the French presence in the country. In 1847 both states came to a standstill after military defeats and the arrest of their leaders. The resulting power vacuum was gradually filled by the expansion of the French colonial state.

The settlement of a loyal group of European colonists was the declared aim of the changing French government. Immigration was massively promoted through land allocation and state aid. The goals of the government were both to consolidate control over Algerian territory and to divert the increasing population pressure from the motherland in the course of industrialization and urbanization . The majority of the colonists initially came from Spain and Italy. The main motive for emigration was the comparatively difficult economic situation there. In 1848 only 9% of the 100,000 European civilians in the country were French citizens . The majority of the French who came to Algeria came from the Mediterranean south of the country. As a result of immigration and naturalization, 220,000 of the 423,000 colonists were French in 1889. After the February Revolution of 1848, around 4,000 Parisian workers were deported to the colony . This practice has been repeated several times by the following governments. The French government also set aside 100,000 hectares of land after the loss of Alsace-Lorraine in 1871 in order to settle 1,200 refugee families from the lost areas. In 1875 the territory was officially annexed as an integral part of France . The political incapacitation of the local population was enshrined in the Code de l'indigénat that same year . Only European settlers were granted voting and civil rights. The local population was ruled with the help of local tribal leaders.

The European colonization of the country led to the destruction of the previously existing rural and urban Muslim social structures. The artisans, which numbered around 100,000 before the colonization, were largely destroyed by the opening of the Algerian market to France, so that in the course of the colonization almost all daily consumer goods were imported from France. The associations of the craftsmen were restricted more and more by the legislation of the colonial power until they were finally banned completely in 1868. The institutions of the educational system, which was religiously influenced before the colonization and which was based on Zawiyas and schools attached to mosques , fell into disrepair due to a lack of funding. The colonial state accelerated the decline by confiscating foundation land for these institutions. The European settlers were clearly overrepresented in the colonial school system. The native languages Arabic and Berber were hardly or not taught until 1936 when Arabic was again allowed as a foreign language. In 1944, only around 8% of local children of primary school age attended primary school. In 1954, 85% of the local population was illiterate, around 95% women. Government sponsored land purchases led to a massive redistribution of the most fertile areas from Muslim to European hands. By 1901, 45 percent of the land was owned by European settlers. As a result, the Muslim farmers were exposed to pauperization , which ultimately led to hundreds of thousands of Muslim farm workers working in the colonists' fields for very low wages. The food supply also deteriorated, so that until the first half of the 20th century there were regular famines in which whole areas were dependent on emergency vegetable food and carrion . On the basis of statistical backward calculations , it is assumed that the number of the native population of the country fell from around 3 million in 1830 to 2.1 million in 1872 due to fighting, hunger, illness or emigration.

In 1870, during the Franco-Prussian War, as part of the Mokrani revolt, there was an uprising of 150,000 Berbers and Arabs who viewed the fight against the French as a religiously legitimized jihad . The uprising was put down by French troops. The social conflicts led to a traditional hatred of the Muslim population against colonial rule. As a result, colonists and colonized people within the country were latently hostile and often violent. This led to a social segregation in which the mountainous hinterland as well as the urban kasbahs were viewed as Muslim domains and the fertile coastal areas as the area of influence of the colonists. The Third Republic , which emerged after the defeat of the French Empire in September 1870, raised the previously economically marginalized Jewish community of Algeria to French citizens after the Empire had already taken measures to promote the assimilation of Algerian Jews to the colonial state. This is often seen as an aggravating factor in the popular anger of the Mokrani revolt. The emancipation of Jews was also rejected by many French Algerians due to fear of losing their own privileges and anti-Semitism .

In the First World War, 173,000 Arabs and Berbers served in the French army. 25,000 died and 57,000 were wounded. Several tens of thousands were also brought to France as workers. More than a third of all Algerian men between the ages of 20 and 40 were in France during the war. The military and labor service led to an increased politicization of the local population. After the war there were some concessions to the veterans , but far-reaching social reforms did not materialize. During the World War there was a locally limited guerrilla of deserters in the Aurès Mountains , which comprised several thousand fighters. It was put down by French colonial troops. During the first half of the twentieth century there was further impoverishment of the rural population. The remaining indigenous land holdings were concentrated within a numerically very small stratum of indigenous society. This led to a lively labor migration of hundreds of thousands of Algerians to France and to a mass emigration to the cities. There the already existing social differences intensified. A local resident had an average of one-eleventh the income of a 92% European middle class.

Beginning of Algerian nationalism

The 1920s and 1930s led to the development of a specifically Algerian national consciousness among the elite cooperating with the French and among Muslim legal scholars . The global economic crisis led to impoverishment and urbanization. In 1933 and 1934 there were violent riots and a pogrom against the Jews in Algiers. The attempts of the local political elite to achieve political concessions across organizations by founding the Congress of Algerian Muslims within the system failed because of the rejection by the government of Léon Blum . In 1937 there was a famine, which made the legitimacy of French rule and the promise of economic development further implausible. This led to a massive influx of the newly founded Parti du peuple algérien under Messali Hadj . Assimilation of the population to a French identity was hardly possible. Only a few thousand wanted French citizenship, which exempted them from Muslim Sharia law and thus isolated a person from the Muslim social structure. Only around two percent of the population changed their colloquial language from Arabic or Berber to French. The party and its demand for national independence were suppressed by the French administration with police means.

At the beginning of the Second World War in 1939, the mobilization of the French armed forces also spread to the North African colonies. The army set up eight colonial divisions, each with around 75% Muslims, the majority of whom came from Algeria. At the beginning of the war, the colonial government recorded few events against the mobilization and was as sure of the loyalty of the Muslim population as in the First World War. During the defeat of France in 1940 , three North African divisions were deployed in Belgium. Around 12,000 Algerians were taken prisoner by Germany. During the Second World War , discontent among the Algerian population increased. The Vichy government tightened political repression. After the conquest of the area in the course of Operation Torch , Algeria came under the rule of the Forces françaises libres . US troops and the US administration's demand to protect the peoples' right to self-determination raised hopes of independence in the eyes of the population. In 1942–1943, around 50% of the conscripts in some regions did not appear to be drafted. In Kabylia , the nationalist PPA managed to set up a political organization. In 1944, of the 560,000 soldiers in the Free French Army, 230,000 were Muslim North Africans. 129,920 of them came from Algeria. However, the Free French government only enlisted around 1.2% of the Algerian population, while 14.2% of the Algerian French were conscripted into military service. Around 11,000 Muslim North Africans died during the war. In August 1943, the Free French government granted Muslim soldiers and officers the same pay as their French comrades, but North African officers remained significantly limited, especially with regard to their chances of promotion. In 1943 the Algerian politician Ferhat Abbas called for an autonomous Algeria within a federation with France. The Free French government - directly confronted with the problem due to the location of its headquarters in Algiers under Charles de Gaulle - implemented a hesitant reform program. A key point of the program was the naturalization of 65,000 Muslims as full French citizens and fell short of the Algerians' expectations. However, it radicalized the settlers who opposed any reform.

On the occasion of the end of the Second World War in Europe , victory celebrations were also held in Algeria in May 1945. These used Algerian nationalists to illegally carry Algerian national symbols, which was tolerated by the authorities in most regions of the country. However, in Sétif , the capital of Muslim life in the colony, there was a shooting while attempting to lower the flags. This event is also known as the Sétif massacre . This resulted in unrest in the region in which large parts of the Muslim population attacked the European population at random. 102 Europeans were killed. In Guelma, the settlers' paramilitary militia massacred one in four Muslim men of gun age, around 1,500 people. The French military responded with a repression campaign involving 10,000 soldiers. Thousands of Algerians fell victim to this - the exact numbers are unclear. In terms of security policy, the French authorities were able to pacify the country again, but the events created a political climate in which a large part of the Muslim population vehemently rejected French rule. In particular, the 136,000 Algerians returning home after the unrest, who had fought on the Allied side in Europe, were thereby motivated to join nationalist movements. After the violence and the associated political repression, the Algerian political spectrum was constituted in two parties - the Movement for the Triumph of Democracy ( Mouvement pour le triomphe des libertés démocratiques , or MTLD for short ), founded by Messali, and the Democratic Union of the Algerian Manifests ( Union Démocratique du Manifeste Algérien , short: UDMA ), led by Ferhat Abbas. Both parties publicly committed to non-violence and legality. In Messali's party, however, younger members insisted against the party leadership in May 1947 on the establishment of an armed cell, the Organization Spéciale (OS), which was to specialize in armed actions. The organization comprised 1,000 to 1,500 members and was largely dismantled by the French authorities by 1950. 1947 by the French authorities in Algeria statute governed democratic representation in Algeria. A legislative assembly was convened, which, due to the separation into a chamber of European origin and a chamber for locals, gave the voice of a settler eight times the weight of an Algerian vote. During the election of the assembly, under the leadership of Governor Marcel-Edmont Naegelen, massive election fraud and intimidation of political opponents were committed. As a result, a majority of 41 of the 60 seats in the local chamber were held by state-sponsored individuals who were not part of the nationalist party spectrum. The population did not feel represented by these candidates, who were decried as yes-sayers (Beni oui-oui) .

Egypt, a center of Algerian nationalist exiles alongside neighboring countries, developed into a supporter of the Algerian nationalists after Gamal Abdel Nasser came to power in 1952. The Egyptian government supported the nationalists initially through diplomacy and also through radio programs broadcast to North Africa, which were intended to spread pan-Arabism . However, like the governments of Morocco and Tunisia, the Egyptian leadership subordinated its involvement in North Africa to its own diplomatic interests vis-à-vis France.

Establishment of the FLN

In the mid-1950s, numerous MTLD cadres split off from the party and its leader Messali as the Front de Liberation Nationale . The main motive for the split was Messali's distancing from the OS guerrillas after they were broken up. The dissidents among the OS veterans saw this as an admission of his disinterest in armed struggle, which they saw as the only promising path to independence. The FLN was founded in the summer of 1954 and claimed political sovereignty and subordination to the armed struggle as a means of achieving independence from France. It saw itself as the only legitimate political representative of the non-European population and enforced this claim by force against more moderate political forces. The FLN publicly announced a socialist, democratic and Islamic republic as the future form of government. The FLN also committed itself to promoting unity among the North African states on the basis of their cultural similarity.

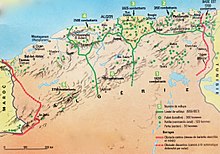

With the National Liberation Army (ALN), the organization created a guerrilla association that was supposed to enforce its goals militarily. The ALN divided the territory of Algeria into six districts (Wilayat) and set up underground fighters there in a centralized manner. At the beginning of its existence in 1954, the ALN could only count on around one to two percent of the population as supporters and possible combatants. The units were correspondingly small, with only a few hundred armed men per district. Overall, the total number of combatants in the FLN at this point in time is estimated at 900 to 3,000 men. From the beginning, the FLN was organizationally split into an internal organization in Algeria itself and an external organization operating abroad . The external organization comprised the political leadership, which represented the highest authority of the organization in relation to the military leadership in the country. Its headquarters were established in 1954 in the Egyptian capital Cairo with the approval of the Egyptian head of state Gamal Abdel Nasser . As an anti-colonialist and pan- Arabist, Nasser was ideologically close to the goals of the FLN and hoped for a possible role for Algeria in its pan-Arab state, which was propagated as a political goal.

course

FLN offensive

On November 1, 1954, the FLN launched an offensive with terrorist actions and guerrilla attacks in all of its military districts. The day went down in French history as Bloody All Saints' Day . The French authorities counted 70 attacks with three dead and four injured. A total of 479 violent attacks occurred in November and December 1954. The main targets of the operations were collaborating locals. The FLN consciously pursued the goal of interrupting the social and political contacts between the colonial power and the locals. Preferred targets of the insurgents among the locals were qaids, elected representatives at the local level, tax collectors, taxpayers and Algerian members of the French armed forces. Often the violence was extended to their families by the FLN. For every victim of the FLN of European descent, there were six local people killed by the FLN in the first two years of the war. Other targets were the French police and the military as well as export-oriented economic institutions and French Algerians (" pied noirs ").

The attacks themselves were significantly less efficient than the political leadership had planned. The District Five ( Oran ) deputy commander was killed at the start of the fighting. The organization of District Four ( Algiers ) was broken up by the French police within a few days. Politically, however, the FLN recorded a victory. The organization suddenly became known with the help of the Egyptian radio program, which was also heard in Algeria. The Egyptian government under Nasser also began to support the FLN with arms deliveries.

The European population as well as the authorities initially dismissed the events as an attempt, directed by Gamal Abdel Nasser , to provoke unrest. A few months later, the French security authorities arrested 2,000 supporters of Messalis and drove the previously moderate nationalists into the hands of the FLN. The local population supported the struggle for independence, but mostly only found out about the existence and positions of the FLN in the following months. The established Algerian politicians rejected the acts of violence.

The French state responded with a campaign of repression against the insurgents. The 50,000 French soldiers in the country quickly succeeded in pushing the FLN back from the urban centers. In the mountainous areas of retreat of the country, the FLN was able to rely on a tradition of rural irregulars and thus avoid being completely broken up. At the same time, their notoriety and popularity among the Muslim population increased. The FLN was also able to attract large parts of the local elites of the old parties and the ulama, who were still cooperating with the French, to its side , partly through targeted violence or threats thereof, partly by granting personal advantages . As a result, the number of attacks continued to increase, although the structure of the FLN continued to fall apart. In February 1955, the French military came to the realization that it had failed to crush the resistance with the means available in the country. In January of the year by the Government Pierre Mendes France with Jacques Soustelle a new governor ordered, in addition to military repression also publicly sought a social integration of the Muslim population. In March 1955, part of the country was placed under martial law , the rest gradually followed. In May 1955, the French military called up the first reservists to increase the troop strength in Algeria. On August 20, 1955, at the behest of the FLN, thousands of Algerian civilians clashed in several European settlements in the Constantinois department , killing 123 people, including ten children of European descent. This “ Philippeville massacre ” radicalized the French public and massively discredited Soustelle's ideas for integrating the Muslim population into a civil society based on the French model. It also sparked a military backlash, killing thousands of local villagers. The massacre was carried out on the initiative of the commanders of District Two ( Constantine , Bône , Philippeville), Youssef Zighout and Lakhdar Ben Tobbal, to deliberately escalate the violence between locals and settlers.

Attempt at pacification under Mollet

In February 1956, the socialist Guy Mollet was elected French Prime Minister. One of the main points of his election campaign was the promise of pacifying Algeria and keeping it in the French national association. Mollet and subsequent administrations saw the holding of Algeria as indispensable in order to maintain France's great power status. Should France lose Algeria to the left-wing FLN, France would lose all influence on the neighboring countries Tunisia and Morocco, which became independent in 1956, through the emergence of a communist bloc in North Africa . The attempt of the French government to win aid from NATO for the war failed because of the negative attitude of the USA. The Eisenhower administration considered material support to be possible only if an early solution was found on the basis of the peoples' right to self-determination. The later Kennedy administration followed a similar course and feared that the conflict could weaken NATO's cohesion.

Mollet visited Algiers on February 6, 1956 and, contrary to his expectations, was received by tens of thousands of war veterans and settlers, who started demonstrations and riots just in time for his appearance. Under this public pressure, Mollet once again underlined the fact that the country was part of France. The war veterans' association of the Algerian settlers, which was behind the riots, was banned shortly afterwards and the settlers were reassured by the public concessions, but the local population saw this as a further provocation and felt that the central government had set them back against the settlers.

Mollet wanted to bind the population to the existing political conditions through a rising standard of living. This should be achieved through a massive investment program, especially in rural areas, as well as increased labor migration to France. On the military side, Mollet planned to be able to break up the FLN by means of a massive increase in troops to 450,000 men in mid-1956. For this purpose, the country was to be divided into four hundred military districts (quadrillages) , each of which was occupied by a unit. Likewise, by the forced resettlement of hundreds of thousands of farmers, the connection between the population and the guerrilla refuges should be cut off. In March 1956, the government passed a law that established strict press censorship in Algeria. Likewise, the imprisonment of militant Algerian nationalists in internment camps, which began in 1955, was expanded and several tens of thousands of Algerians and 1,860 were imprisoned in France.

The FLN reacted to the double strategy with increasing politicization of the war. For example, it banned the local population from going to school and buying tobacco and alcohol. As a result, many civilians came under pressure from both sides. Although the military repeatedly achieved spectacular local successes against the guerrillas, the military operation could not stop their growth to around 20,000 active members and 40,000 organized supporters. The warfare of the French troops with the systematic use of torture and collective reprisals against population groups suspected as enemies ( French doctrine ) were largely responsible for the popularity of the FLN. In addition to the numerical growth, the FLN managed to expand its structure in the first two years of the war into an underground state that encompassed large parts of the local population. This included a separate jurisdiction, tax collection and a rudimentary pension and social system. Two years after its appearance, the FLN successfully competed against the established institutions of the colonial state. Likewise, under the aegis of Abane Ramdane, the FLN was able to achieve the self-abolition of all existing political parties of the local people except Messali's MNA movement by July 1956 through a combination of negotiations and acts of violence. Numerous cadres of the older groups joined the FLN; including Ferhat Abbas after he dissolved his own party.

At the same time, violence between settlers and the local population got more and more out of control. Murders by the FLN were followed by lynching by French Algerians, which in turn led to renewed violence on the part of the locals. In the urban center of Algiers in particular, the situation became increasingly uncontrollable for the French at the end of 1956. As a result of France's involvement in the occupation of the Suez Canal during the Suez Crisis , Egypt expanded its aid to the FLN. The direct neighbors Tunisia and Morocco also increased their support. Both states offered refuge for soldiers and refugees, supported the training of the ALN and supported arms smuggling as well as the infiltration of guerrilla fighters through their territory into Algeria.

Battle of Algiers

The FLN began planning a further escalation of the conflict under the political leadership of Ramdane. This was supposed to shift the war from the rural regions to the city through terrorism and guerrilla attacks in Algiers. Targeted violence against French civilians and symbols of colonial rule should be in the foreground. An internal FLN directive stated: A bomb that kills ten people and wounds fifty is, on a psychological level, tantamount to the loss of a French battalion. In addition, the action should be flanked by political actions. A week-long general strike was planned to demonstrate popular support for the FLN to the French and the world.

Yacef Saadi was entrusted with the planning of the operations as Commander-in-Chief . He was himself a resident of the Kasbah of Algiers. He had around 1,500 armed activists. As a base of operations, he had the kasbah expanded into a fortress of the FLN. The kasbah was systematically purged of all potential political deviants and criminals by force. A system of tunnels and secret rooms was also created, creating a place of retreat from the authorities. To maximize the security of his organization, Saadi organized his group into independent cells with no information exchanged between these cells. The operations began from the perspective of the FLN on September 30, 1956 with three bombs placed by European-clad FLN activists in a student bar and the Air France branch at the city's airport. A campaign of planned terrorist violence against civilian and military targets followed. The FLN also launched a campaign within the Algerian emigrant community in France to crush the last remnants of the messali movement. Several thousand Algerians were killed there in attacks. As the situation in Algiers got more and more out of control, on January 7, 1957, Resident Robert Lacoste surrendered police power to the military, represented by General Jacques Massu .

The French armed forces, under the high command of Massu, countered the increasing violence and political action with a massive military action, the methods of which came to be known as the French Doctrine . Under the leadership of Roger Trinquier, the kasbah was covered with a system of informants, parts of the population were recorded in an index card archive and, as in the rural counterinsurgency, clearly defined areas of operation were assigned to certain units. Systematic torture of suspects and executions followed by silence about the whereabouts of those executed, the so-called " enforced disappearance ", were routine counterinsurgency measures in the campaign. During the clashes, around 30–40 percent of the male population of the Kasbah of around 40,000 were arrested at least once. Massu first tried to prevent the general strike on January 27, 1957 by distributing food, gifts and propaganda material. After this did not show any response, he had his soldiers forcibly drive as many workers and traders as possible to work. Strikebreakers were occasionally killed by the FLN. The supplies of people and material of the FLN for their activities in the interior and the urban centers had to be brought from the borders with Morocco and Tunisia. The system of quadrillages exposed the guerrillas advancing undercover to constant persecution pressure. In mid-1957, the French side began building a series of border fortifications at the instigation of Defense Minister André Morice . This included the sparsely populated desert areas and used large-scale electric fences and self-firing systems.

Over the next few months, the French military managed to break up the FLN network in Algiers. Yacef Saadi was arrested in late 1957. Exact numbers of those tortured and killed by the armed forces are not known. It is estimated that there are several thousand. The events led to a further polarization of the population, but not to a general surge in popularity of the FLN, as many locals did not approve of the FLN's targeted violence against civilians. The organizational structure of the movement suffered significantly during the clashes, and the successful suppression of the general strike was seen as a political defeat. However, the high-profile culmination of the violence in the capital disillusioned the population of European France and had a lasting impact on the political climate against the engagement in Algeria. The widespread use of torture and its appearance in the mass media shaped French public opinion against the continuation of the war. At the end of 1957, polls in France only showed 17 percent support for Algeria to remain an integral part of the French state. 23 percent supported a gradual transition to political independence. 23 percent were in favor of immediate dismissal from the state association. The prohibition by the French state of the work La Question by Henri Alleg , which deals with torture by French troops, caused an international scandal in 1958.

Independently of the operations in the country, the French security authorities were able to arrest the senior management of the FLN led by Ben Bella in October 1956. The politicians were on a flight from Morocco to Tunis in a civil plane at the invitation of the Tunisian and Moroccan governments. The French flight crew rerouted the machines to Algiers on the instructions of the secret service. The domestic leadership of the FLN around Abane Ramdane left for Tunis in February 1957 after the arrest and murder of Larbi ben M'Hidi . After Ramdane's escape, his prestige within the organization fell significantly. He was murdered by his own people after speaking out against the increasing power of the military leaders within the movement. The most influential still-free leaders of the FLN Belkacem Krim, Ben Tobbal and Abdelhafid Boussouf, occupied the majority of the party bodies with members of the military apparatus loyal to them. Likewise, the previously independent districts were each assigned to three districts to a commander loyal to the new leadership. Despite the losses, the FLN was able to keep the number of its militarily organized activists stable at around 21,000, but was unable to expand it. The heads of the French military and the colonial administration entrusted with leading the war were of the opinion, in view of the military successes at the beginning of 1958, that a victory and the suppression of the FLN were foreseeable.

De Gaulle came to power in May 1958

The French Fourth Republic increasingly suffered from political instability with changing cabinets and coalitions. Guy Mollet fell in June 1957 because of dissatisfaction with a further increase in the military budget, which the government wanted to quadruple within two years. From 1955 to 1957, the cost of the war had increased the national deficit from 650 billion francs to 1.1 trillion francs. The franc was devalued against the other currencies in the Bretton Woods system in 1957 and 1958 ; there were fears of an economic crisis. The debt burden also prevented Mollet from financing large parts of his planned social and economic investments. Nevertheless, he remained a kind of gray eminence in the decision-making of the following coalitions. His second successor, Félix Gaillard , fell in May 1958 as a result of the internationalization of the Algerian conflict following the French air raid on Sakiet Sidi Youssef , a Tunisian border town with Algeria. This attack was in retaliation for guerrilla attacks by rebels who retreated there across the border. They also shot at and planes. After the attack, there were fierce international protests and a request from the Tunisian government to the UN Security Council could only be turned off if the British and the USA mediated. In May 1958, Pierre Pflimlin took over the office of Prime Minister; he was the third new head of government since Mollet. Before taking office, Pflimlin said he would start negotiations with the FLN with the aim of a ceasefire. This was a continuation of secret talks begun under the Mollet government. The military and the settlers saw this as a sign that the political parties were ready to sacrifice their interests in Algeria for a peace treaty.

Fueled and organizationally supported by the military, settler organizations in Algiers mobilized around 100,000 people for demonstrations. These culminated in attacks and the looting of government buildings. Thereupon Massu announced the takeover of power by the military in Algeria on the radio and demanded that Charles de Gaulle take over the power of government in Paris. Massu involved prominent Muslims in the formation of a public security committee, and the Military Intelligence Service's Psychological Warfare Department organized pro-French participants for the demonstrations from among local people. Part of these rallies was also an " unveiling campaign " during which several dozen Algerian women took off their full-body veil, the "Haïk". The participants were members of the Mouvement de solidarité féminine , a charity that was chaired by General Raoul Salan's wife . In Paris, Pflimlin tried to assert the legitimacy of his government. On May 13, 1958, a coup took place in Algiers . On May 24th, a paratrooper battalion bloodlessly took possession of the island of Corsica ( Opération Résurrection ). The military also planned to land paratroopers in the capital, Paris. After President René Coty de Gaulle had nominated Prime Minister on June 1, 1958, this military operation did not take place. De Gaulle was tasked with forming a new government and constitution.

De Gaulle traveled through Algeria shortly after taking office. He was cheered on by both sides, but did not make a final statement on the status Algeria should have in the future. He did not contradict his earlier statements that Algeria was naturally an integral part of France. With a referendum on the new constitution on September 28, 1958, de Gaulle achieved a political victory. Although the FLN threatened the death of the locals who voted, the majority of the population voted. In some cases, Algerians were persuaded or forced to vote. In places, votes against the referendum were not counted. De Gaulle promised in the Constantine Plan a significant increase in the standard of living of both the Algerian French and the local population. A government investment program should create 400,000 jobs and apartments for one million people. Likewise, 250,000 hectares of land should be distributed to Muslim farmers. The government hoped for an economic upswing from oil reserves in the Sahara .

The FLN leadership reacted to the change in power in France and the high level of participation with uncertainty. She feared that the new government could actually pacify the country and deprive the FLN of its political power base. The FLN then forced attacks, attacks and acts of sabotage within Algeria and also in France itself. On the political level, it tried to strengthen its legitimacy by forming a Provisional Government of the Algerian Republic (GPRA) with Ferhat Abbas as head of state. The seat of this government in exile was Cairo . It was immediately recognized by all Arab states with the exception of Lebanon, which is closely linked to France . If France recognized the GPRA, France threatened the Soviet Union with breaking off diplomatic relations. In preparation for the Second Berlin Crisis , the Soviet Union refrained from recognizing the GPRA in order not to endanger its relations with France. Outside the Arab world, the government in exile was recognized by the People's Republic of China , North Korea , North Vietnam and Indonesia . The government-in-exile maintained a formal and informal network of employees in around twenty countries, including Western Europe. The government-in-exile received financial support from the Arab League; its budget was roughly equivalent to the expenditure the FLN spent on armed resistance and the establishment of its own clandestine state within Algeria. The support of a failed coup attempt within the GPRA by Egypt and a restriction of its activities in Tunisia because of a pipeline deal between the local government and France put a strain on the relationship between the FLN and its supporters in 1958.

Challe offensive

In order to force the FLN to lay down their arms or to find a negotiated solution, de Gaulle planned a military offensive, which should break the resistance and the organizational structure of the FLN. General Maurice Challe was in charge . The aim of the offensive was to isolate the guerrillas from the population and to destroy them physically. In addition, Challe expanded the pro-French units from Algerians from 26,000 to 60,000. Likewise, 19,000 Algerians in rural areas were organized into pro-French militias. These forces should operate close to home and track down the FLN fighters through their knowledge of the local social and terrain structure. The effect of these missions was to be reinforced by the creation of hunting squads made up of volunteers who operated on their own for long periods far from their own bases. The combat should then take over mobile French forces, especially air-mobile paratroopers . Challe's plans provided for a reserve of 3,000 to 4,000 men, always ready for action, to be ready for action at any point in the country within hours. Overall, Challe doubled the reserves deployed as mobile reaction troops from around 15,000 to 35,000 men. He also relied on an increased use of air-mobile formations. In addition to the operations of the mobile reserve, the troops distributed in the country were to drastically intensify the guerrilla warfare at the same time. The plan to intensify the war led to the increase of French troops in Algeria to 380,000 men. In order to ensure the spatial separation of the guerrillas from the population, around one million villagers were forcibly relocated to camps by 1959.

Within months, the FLN lost around half of its around 21,000 militarized cadres in the country to death, wounding or capture. The closure of the borders to Morocco and Tunisia, which had already begun under Challe's predecessors, ensured that the losses could no longer be compensated. The parallel state structure of the FLN was also significantly pushed back by the military operations. From 1959 the guerrillas could no longer cover their financial needs from their own surveys in the country and had to be financed more and more by the foreign organization. In addition, the French armed forces achieved success using intelligence methods. French disinformation led to a violent purge in District 3, which killed 2,000 loyal cadres. As a result of the offensive, the French armed forces were able to destroy the military organization of the FLN in large parts of the country, but not their ability to act. There were still small units of platoon or group strength. The external leadership now shifted to intensifying the build-up of regular troops in the neighboring countries of Morocco and Tunisia. As a result, parts of the internal organization refused to show loyalty to the external leadership. Among other things, FLN troops had to put down the rebellion of a local commander who had withdrawn to Morocco with his severely decimated troops. During this leadership crisis, Houari Boumedienne managed , as chief of staff of the troops abroad, to gain an increasingly dominant power base vis-à-vis the political leadership.

The offensive increased the pressure on the Algerian people from both sides. French politics and the generals wanted the social structures of traditional Muslim society more to the French Republic adjust to the country to pacify permanently. As a result, numerous laws were passed in 1958 and 1959 that were intended to offer Muslim women political equality and equal educational opportunities, in contrast to the previously officially valid legal norms of the Sharia . The rejection of the traditional veiling of women became an image often used in propaganda and media justification of the war. The attempt, already begun under Mollet's predecessors, to improve the living conditions of the rural population through mobile teams of doctors and nursing staff and, in particular, to provide women with knowledge of modern hygiene, was drastically increased. In 1961, 231 teams consisting of at least one doctor and three nurses operated. As a side effect, the Algerian women were to be won over to the French side and the support of the population withdrawn from the FLN.

However, large parts of the population suffered from coercive measures. Two million Algerians were forcibly interned in camps by the end of 1959 and thus placed under direct military surveillance. Many experienced torture on their own bodies or on family members. The army also used sexual violence against women as an instrument of sanction to an extent that has not been quantified in any further detail in the literature. These factors minimized the credibility of the French reform efforts and drove many Algerians to sympathize or support the FLN.

The offensive was unable to eliminate the French settlers' fears of the country's independence. While the victims of collateral damage and terrorism publicly drew attention to their fate, the fear of being abandoned by metropolitan France grew in the majority of the population of European descent. In France itself, the number of supporters of armistice negotiations with the FLN rose from 58% in January 1959 to 71% in March 1960.

Week of the barricades

During the fighting of the Challe Offensive, de Gaulle prepared a political solution to the conflict in talks with leading politicians, the military and diplomats. De Gaulle wanted to present this publicly from a perspective of military strength. De Gaulle envisaged a free plebiscite for the Algerian and French populations as the basis for the decision . De Gaulle suggested three possible solutions. On the one hand, the complete independence of the country, the complete integration of Algeria into the French Republic with French citizenship for all residents, or limited independence in close political and economic ties to France. De Gaulle preferred the latter alternative. In his opinion, complete independence would have resulted in a totalitarian dictatorship of the FLN analogous to that of the Eastern Bloc countries . In de Gaulle's opinion, integration of the country with full citizenship for all local residents would have culturally infiltrated France through immigration and destroyed the national character of the country in view of the higher population growth of Algerians. The President announced these three options to the public in a televised address on September 16, 1959, highlighting the country's limited independence as the most sensible route. De Gaulle announced that the Algerian people would vote on the options he had outlined. In order to gain the necessary legitimacy for this decision, de Gaulle wanted to put it up for election in France in a referendum. De Gaulle's proposal was ratified in the National Assembly in October 1959 with 441 votes to 21, thus authorizing his government to hold a referendum in France. 57% of the population of France supported the proposal at the time.

Within the army units stationed in Algeria , especially among officers and professional soldiers , the speech was largely rejected. Jacques Massu (1908–2002), general de division , played a key role in Algiers and in the coup of May 13, 1958, criticized publicly (interview in the Süddeutsche Zeitung ) and said that perhaps the army had made a mistake in appointing de Gaulle as president committed; the interview received a lot of attention. Large parts of the settlers perceived the president's proposed solution as a threat to their existence in a state dominated by the majority of the local population. Existing settler organizations came together in the French National Front (FNF) under the leadership of Joseph Ortiz and Pierre Lagaillarde and planned violent protests to dissuade the central government from its policies. The FNF used symbols of the banned neo-fascist organization Jeune Nation and maintained a paramilitary structure. Many of its members had served in state-formed self-protection militias.

The FNF occupied the University of Algiers with 600 uniformed paramilitaries on January 23, 1960 and set up an armed base there. The military stationed in the city did not intervene, and the following day there was a solidarity demonstration by around 20,000 French Algerians. When the French gendarmerie tried to clear the barricades set up by the demonstrators, individual demonstrators from the crowd opened fire on the police officers. 14 officers died and 123 were wounded. Eight protesters died from police bullets and 24 were injured. On January 29, after unsuccessful negotiations, De Gaulle stated in another televised address that he would not give way to the demands of the FNF for the referendum to be withdrawn. Likewise, through the loyalty of the senior officers, de Gaulle was able to prevent fraternization of the military with the FNF and the demonstrators, so that their support in the Algerian-French population quickly declined. Ortiz withdrew on February 1, and Lagaillarde surrendered to the authorities. De Gaulle used his political victory to disband military intelligence units operating in Algeria , whose loyalty he questioned, and to dismiss or transfer potentially disloyal officers. The collapse of the revolt was welcomed by three-quarters of the French population of the mother country. The events known as the Week of the Barricades also met with broad approval of the solution (desired by de Gaulle) of a formal association of a partially independent Algerian state within the mother country.

Referendum and coup of the generals

The resistance of those who clung to a French Algeria and wanted to block a possible path to independence from the French side by force was not broken. At the beginning of 1960, greats of the colonial establishment such as the ex-governor Jacques Soustelle founded the Front of French Algeria ( Front d'Algérie français , short: FAF ). Shortly after it was founded, the organization had more than a million members. In particular, it was aimed at men and non-commissioned officers of the troops stationed in Algeria. The FAF planned to remove de Gaulle when visiting the city of Algiers for the referendum through a combination of a mass, violent demonstration and a military coup. The plan was prepared, but de Gaulle canceled his visit to the territory's capital. On January 8, 1961, 75% of the French mainland and 70% of the voters in Algeria voted in a referendum in favor of de Gaulle's bill, aimed at self-government in Algeria. One of the reasons for the low turnout in Algeria was the FLN's ban on participation, as it considered the French vote on the fate of Algeria to be illegitimate. The FAF was banned after the referendum. The terrorist group OAS , which was founded at the turn of the year, was recruited from around them and wanted to thwart the country's independence with openly violent means and terrorism.

The organization - led by ex-military and radical nationalist activists - planned another coup and was able to win the popular General Challe in the course of planning. Under the leadership of officers Zeller, Challe, Salan and Jouhaud, paratrooper units, especially parts of the 1st REP and the 1st RCP, took control of Algiers, and Challe announced the takeover of power by the military under the collective leadership of the above-mentioned officers in Algeria and on the radio the Sahara. The conscripts in the city were kept under curfew in the barracks by order of Challe. The "coup of the generals" on April 21, 1961 found support from many French Algerians. Demonstratively uniformed OAS militants joined the paratroopers. Only a few units and officers - a total of 25,000 soldiers - in Algeria followed the coup, the army on the continent remained completely loyal to de Gaulle, who, as a first measure, cut off all communication between France and Algeria. The putschists themselves had not carried out any logistical planning and were dependent on supplies from France. The possibility of an air landing for the coup plotters in France was taken away by the loyalty of the air force, which withdrew its transport planes from Algeria. The coup was rejected by the French population and the general public. There was an hour-long general strike and demonstrations in favor of de Gaulle across the country. As a result, the coup collapsed by April 25, 1961. The OAS went underground and continued to pursue its political goals with terrorist means.

Peace negotiations and continued violence

On May 20, 1961, direct negotiations between the French government and the FLN began on French soil in Évian-les-Bains . As a sign of goodwill, de Gaulle ordered the release of 6,000 prisoners in advance, transferred the FLN leadership interned in France to a country castle and announced a unilateral ceasefire. De Gaulle granted the other side in the negotiations the independence of the country and sole political representation by the FLN. For this he expected concessions regarding the status of the oil-rich territories in the Sahara as well as special legal protection for the Algerian-French. The FLN continued its guerrillas to persuade the French side to withdraw unconditionally. In addition, demonstrations and unrest among the Algerian population increased. In July 1961, the FLN called for a general strike lasting several days, which was followed by the majority of the Algerian population. This was followed by riots and looting in the big cities, which could only be suppressed by deploying 35,000 soldiers.

Both the OAS and the FLN tried harder to carry the war to the French mainland through attacks and political actions. The FLN attempted to put pressure on the government through both terror and political action. On October 17, 1961, she organized a non-violent protest march by around 30,000 Algerians in Paris. The reaction of the French state came to be known as the Paris Massacre . The police killed up to 200 demonstrators and deported around 11,000 out of the country. The events were denied by the local authorities under Maurice Papon . The OAS launched a terror campaign and carried out attacks almost every day in early 1962, particularly in the capital Paris. After the OAS killed a toddler from a neighboring family in an attempt to murder the Minister of Culture, André Malraux , mass demonstrations broke out across the country, in which nine demonstrators were killed by the police in Paris. The protest movement, led by the PCF and the trade unions, responded with a one-day general strike and a gathering of around one million people in the capital alone.

Peace Accords and Independence

The escalation of both the terrorist violence of the OAS in France and the pressure of the public motivated de Gaulle to significantly accelerate the negotiation process by making concessions. Thereupon, on March 18, 1962, the contracts of Évian were concluded. They signed a ceasefire with the FLN and mandated a referendum on independence. This should be organized by a joint Algerian-French administration. The French troop strength in the country should be reduced to 80,000 within a year. The French government recognized the Sahara as an integral part of Algeria. For the naval and air force bases around Mers-el-Kébir , France received a 15-year right of reservation. The FLN also allowed France to continue using its nuclear weapons test facilities in the Sahara for five years . The political and cultural rights of the Algerian French were explicitly guaranteed in the agreement by the Algerian side. This population group was given a three-year period to choose between Algerian and French citizenship. The treaty provided guarantees for the property of citizens of European descent. Likewise, both states committed themselves to the exploitation of the oil reserves of the Sahara by a joint company, the settlement of oil reserves in French francs and the pegging of the Algerian currency to France (→ Algerian franc ). High-ranking FLN members internally expressed the aim of offering the most conciliatory conditions possible, since an independent Algeria would be able to quickly cancel the provisions of the treaty.

In return, the OAS tried to create enclaves under its control in urban areas (including Bab el Oued in Algiers and Oran) with a high proportion of the population of European descent. This was intended either to achieve secession of European-controlled areas or to force the FLN to counter-violence, which would ultimately destroy the peace treaty. The FLN held back, however, and the French armed forces crushed the rebellion in several days of street fighting using air support and heavy weapons. The attempt by the OAS to thwart military action against them through peaceful demonstrations by their supporters and a general strike failed with 54 dead in the fire of French troops in the massacre on Rue d'Isly . The OAS also directed violence against remaining civilian institutions in order not to leave them to the Algerians, as well as against French Algerians who were willing to flee.

A referendum was held on July 1, 1962 . 99.72% of those who voted welcomed the agreements and 0.28% voted against (turnout 91.88%). The provisional government formed by the FLN under Ferhat Abbas was recognized within three days by France, the USA and several Arab countries as the representative of the now sovereign state.

consequences

War victims

There are contradicting figures about the total number of Algerian casualties and wounded in the war. The FLN put the number of Algerian war victims without distinction between death or injury in 1959 with one million and after the end of the war in 1962 with around one and a half million people. After the war, the phrase of the one and a half million martyrs in Algeria became a means of state propaganda. According to the FLN, around 154,000 members of the FLN fell from a total of 336,000. The French armed forces said they had 24,000 dead and 64,000 wounded. The official French statistics put the civilian casualties at 2,700 dead of European descent and 16,000 native dead. 325 French Algerians and 18,296 Algerians are missing, according to the authorities. Demographic backward calculations fluctuate closely around around 300,000 deaths in the Algerian population.

In 1960 there were around one million French citizens of European descent in Algeria. Between 1954 and 1960, around 25,000 left the country. From 1960 onwards, the terror drove tens of thousands to flee every month. By the end of the war, around 99% had left the country. Violent attacks against Europeans who remained in the country took place across the country on the occasion of independence. One focus was Oran , a center of European colonization, where there were violent clashes between French and Algerian Algerians on Independence Day and several hundred people of European origin were murdered on the following days. The number of certain deaths among the French Algeria after independence is 1,165. The numbers for missing and unresolved cases are higher. The FLN did not pursue the attacks. The French government itself saw it as inopportune to discuss the incidents publicly. Among the French in Algeria, the massacres accelerated emigration to France. The later refugees were only allowed to leave with their hand luggage and were thus de facto expropriated. The fleeing French Algeria destroyed many of their own and state property that they had to leave behind. The property passed to the state, but was often distributed at the discretion of the FLN cadre. A total of 2.3 million hectares of land changed hands. The companies were initially run under the leadership of the UGTA union in workers' self-administration. As a result of the acts of war and, above all, the French policy of forced resettlement, around three million Algerians were displaced, usually from rural areas within the country. The majority was spread over around 2,000 internment camps. Hundreds of villages and their agricultural areas had been destroyed. Several hundred thousand Algerians were refugees in neighboring countries.

Numerous Algerian supporters of French colonial policy, above all the Harkis serving as auxiliary troops , found themselves exposed to violent attacks after the war. Charles de Gaulle personally refused to accept the Muslim volunteers and their families. According to his own statement, he feared cultural and demographic infiltration through the migration of large Muslim population groups to France. De Gaulle prevailed against the resistance of his cabinet and also against public resistance from military circles. Around 100,000 to 260,000 people fled to France via informal networks, which were often run by active or former French military personnel. Exact figures on the number of Harkis killed are not available. Estimates put between 10,000 and 50,000 dead.

Influences on France

The French economy was in crisis at the beginning of the war. Military spending peaked at 10.3% of GDP in 1957. However, French finances were significantly more burdened by civil spending. However, the crisis was overcome through an austerity program led by the de Gaulle government. Expenditures for Algeria averaged relatively constant around 2% of GDP with a general government budget of around 30% of GDP. In the following years, the French economy achieved a boom with growth rates of around 7%, so that military spending in relation to GDP fell to around 7.5%. Economically, the country benefited from the immigration of the French and Algerian refugees, who provided urgently needed labor during the boom. The noticeable increase in the standard of living during this period is also seen as a factor that the French public increasingly rejected the war. In 1962, the year of independence, only 13% of the French believed that war was the country's main problem.

At the beginning of the peace negotiations in the spring of 1961, the French government, under the auspices of the Ministry of the Interior, launched a program of social support for returning French citizens from overseas territories. This was formalized in December 1961, which provided for transitional allowances, housing procurement programs, professional reorientation and partial compensation for lost property. The law made no mention of the French in Algeria and received little media attention, but in the eyes of the French administration it served as a central point of pacifying this population group.

Politically, Algeria's independence represented the end of the French colonial empire. The country's political leadership no longer justified the nation's great power status with the colonial empire, but with the atom bomb, which was first tested in 1960. The personal and institutional changes within the armed forces initiated by de Gaulle marked the end of their role as an independent political actor in France. In 1968 the government pardoned the last remaining coup plotters. Today around 17 million people live in France who were directly affected by the war.

Even before the war there were anti-colonial writers in France such as B. Frantz Fanon . From 1955 left-wing French intellectuals around Michel Gallimard , Robert Gallimard , Dionys Mascolo and Jacques Lemarchand organized themselves in a committee against the continuation of the war. A journalistic movement against the war developed around them. From 1957 there were publications from Christian and bourgeois circles, which mainly denounced the torture and human rights violations on the French side during the war. These met with great media coverage. In 1961, the 121 Manifesto , organized by the founders of the Anti-War Committee, called for impunity for desertion and civil disobedience, as well as support for the FLN. This action met with great media coverage. The French state reacted sporadically with censorship, lawsuits and the distribution of around 2.1 million information brochures, which were intended to give legitimacy to the military action by illustrating the terror of the FLN. The anti-colonialist literature was limited to a small scene in the country. Out of this movement grew a group of intellectuals who called for illegal activities such as conscientious objection and support for the FLN to be morally imperative. The literature that thematized and often heroized the deployment of the French army, such as the books of the officer Jean Lartéguy , had great commercial success . There was also a niche of publications by often prominent advocates of the Algérie francaise , which thematized the peace treaty as a betrayal of the Algerian French. The movement of active opponents of the war remained limited and military service or refusal to command remained isolated events among French conscripts. After the war ended, several hundred French activists left for Algeria to support the FLN in building a socialist state. The organizations and persons of the war opponents later formed a core of the cultural milieu from which the activists of May 1968 were composed.

Independence crisis in Algeria

Independence and decolonization presented Algerian society with major economic problems. The settlers constituted an economic elite that comprised the majority of the academic professions, capital owners, and highly trained skilled workers. Their departure to Europe led to an economic crisis which led to an unemployment rate of around 70% in independent Algeria. Around a third of the 10.4 million inhabitants lived in cities. Approximately 65% of the urban population consisted of former rural residents who lived in slum belts around the actual cities and formed a de facto self- contained social group. Algerian industry employed around 110,000 people in the post-war period, compared to around 400,000 emigrants employed in the same sector in France. Agriculture employed 70% of the workforce and generated around 24% of the gross domestic product. Despite the efforts of the UGTA to self-govern, around 25,000 Algerian landowners owned around 50% of the arable land. The self-government and nationalization efforts of the UGTA ensured that around 40% of the buildable area that had been in the hands of settlers was transferred to cooperatives, which brought around 10% of the male rural population into employment. The main aim of this movement was to avoid buying up the land by the local large landowners.

The FLN adopted the program of the same name in Tripoli in June 1962 and set out the future of Algeria as a socialist state dominated by it as a unity party. At the center of the architecture of the new state should be a political bureau as the supreme control body . This initiative on the part of Ben Bellas offended large parts of the political leadership and the FLN split. Ben Bella rallied the Tlemcen group, which enjoyed the support of large parts of the officer corps of the regular foreign army of the FLN under Houari Boumedienne. In the capital of Kabylia , the Tizi Ouzo group gathered under the leadership of Muhammad Boudiaf and Belkacem Krim. It enjoyed the support of three Wilayat (Constantine, Kabylia, Algerois), the majority of the historical founders of the organization and the foreign organization in France. The Tizi Ouzo group was then broken up a few months after independence from the troops under the military leadership of Houari Boumedienne at the behest of Ben Bella. The renewed flare-up of violent clashes sparked protests by tens of thousands of civilians in Algiers. Ben Bella installed the Politburo despite the opposition and had it appoint a National Assembly, which appointed him President with far-reaching powers. Ben Bella created a socialist one-party state in which the FLN as a mass organization had to enforce the politics of a small circle in the country. In doing so, he succeeded in bringing the FLN's internal union UGTA politically in line at the end of 1963 as the only remaining tolerated center of power beyond his control. This also ended the experimental self-organization of workers on numerous farms and businesses confiscated from Algerian French.

In 1964 a guerrilla was formed in Kabylia, led by former FLN leader Hocine Aït Ahmed . At the behest of Ben Bella, this Front des forces socialistes was broken up with the use of 50,000 soldiers under the command of Boumedienne. Ben Bella tried to legitimize himself through an FLN congress. Ben Bella's government was unable to achieve its main promise, an improvement in economic living conditions. The country's gross domestic product fell by 37% after the end of the war when the French Algeria fled. This created a crisis within the country and the political establishment. Ben Bella was replaced in 1965 by a military coup Boumediennes. The real motives behind the small group of senior officers are not known. On the one hand, the fear of a loss of power for the military in Ben Bella's party-dominated state is posited. On the other hand, the role of the military can also be interpreted as an expression of an Arabized, petty-bourgeois and traditionally Islamic-oriented social class against the dominance of a largely Francophone and Marxist-secular party elite.

The economic misery and political instability triggered another wave of Algerians migrating to France. From September 1 to October 11, 1962 alone, around 92,000 Algerians emigrated to France. The independence crisis led the Algerian nationalists' goal of bringing the emigrants home from France, which had been propagated since the beginning of emigration in the 1930s, to absurdity, which could not be realized in the course of the year.

Franco-German relationship

Since the Federal Republic was not directly affected by the Algerian war, its position must be viewed against the “background of general policy from 1954 to 1962”. One of the political developments was the desired integration into the West, which depended on the relationship with France . In addition, at the beginning of the Algerian War, neither the Paris Treaties , the Rome Treaties nor the Agreement on the Saar question had been signed or ratified. Against this background, the Federal Republic initially took French interests into account and did not address the Algerian war.

This attitude changed, however, when the Soviet Union took on the interests of the Arab countries after the Bandung Conference in 1955 . There was now the danger that the Soviet Union would encourage the Arab countries to recognize the GDR and that the Federal German claim to sole representation would be lost. The Arab embassies in the Federal Republic threatened the Federal Government with recognition of the GDR after the Bandung Conference.

For the federal government in Bonn it was then difficult to live up to its loyalty to France and its claim to sole representation. In addition to these developments, the Arab countries sided with the FLN, "which severely restricted the German leeway". Both these facts and the longstanding friendship and trade relations with the Arab countries prompted the federal government to change its perspective. You now went over to a "balancing act". This consisted of preferring French interests, but accommodating Arab views without annoying France too much.

The first stress test of this policy came with the Suez crisis in 1956. Despite the military action of the French and British, the “balancing act” was successful here. On the one hand, the German government criticized the military action of the British and French, but at the same time showed understanding for the Franco-British initiative. On the other hand, it pushed for a peaceful solution within the framework of the United Nations , thereby taking the interests of the Arab states into account.

The actors who influenced the Franco-German relationship during this time also included the so-called "porters". These were mostly non-political German groups or individuals who showed solidarity with the Algerian independence movement for socialist, Christian, humanistic and political motivation. They helped, for example, with the transport of Algerian independence fighters to the Federal Republic, their accommodation and the delivery of weapons for the FLN.

With regard to arms deliveries, the French Navy also checked German ships outside their territorial waters. For the Federal Republic, which had only been occupied since 1955, this procedure represented a violation of its sovereignty. This increased tensions between the Federal Republic and France. However, it should not be disregarded that the Federal Republic also endured the injury. This can be attributed to the consideration for France and the pursuit of the “balancing act”.

With the pursuit of the internationalization of the Algerian War on the part of the FLN from 1958 on, it finally came about that in addition to many Algerian refugees, representatives of the FLN also came to the Federal Republic. As a result, an FLN office was opened in the Tunisian embassy in Bad Godesberg. On the one hand, the Federal Republic risked its relations with France, on the other hand, it wanted to prepare for possible independence, which is why FLN activities on German soil were tolerated, especially from 1960, when a victory for the FLN seemed increasingly likely.

As a result, from 1958 onwards France increasingly took action against the porters and actors of the FLN in the Federal Republic. Mention should be made of the main rouge , which among other things carried out the attacks on the German arms dealer Georg Puchert and the FLN actor Ait Ahcène. The actions of the French against porters and FLN actors on German soil and the associated violation of German sovereignty repeatedly led to tensions between the two states.

With de Gaulle taking office and the ever closer settlement of the conflict between Algeria and France, the federal government gained more and more political leeway and was able to break away from the “balancing act”. Overall, the attitude of the federal government has paid off. Through them she has managed to maintain relations with both France and the Arab countries. Above all, the relationship with France assumed a steady development in the period that followed. Shortly after the Évian treaties were signed , Franco-German relations turned into Franco-German friendship. Less than a year after the end of the Algerian War, this was sealed with the Élysée Treaty .

historiography

After Boumediennes came to power, the Algerian government forced a historiography of the war prescribed by the state, which, as the Algerian Revolution, represented the founding myth of the state. The official historiography tried to highlight the merit of Boumedienne's foreign army of the ALN against the acts of the domestic guerrilla and the FLN in France. The political pluralism within Algerian nationalism and its violent suppression by the FLN, as well as the wing battles within the organization itself, were kept secret. On the other hand, there were counter-statements from prominent FLN cadres in Algeria such as Mohammed Harbi and Ferhat Abbas , who had gone into exile. The extent of the literature on the war published in France about the war clearly exceeds that of the works published in Algeria. In 1981, in the post-Boumedienne era, the Algerian historian Slimane Chikh criticized the hagiographic character of Algerian historiography of the war. He was followed by other historians who called for a revision of the state-decreed historical image. In addition to the official state term of revolution and war, other terms such as liberation war ( Harb at-Tahrir ), armed struggle ( An-Nidal ) or jihad are used for war in Algeria .

Between 1960 and 1980, more than a thousand works from all media about the Algerian war appeared in France. The French historian Benjamin Stora criticizes the fact that many of these works leave out unpleasant elements of this war. The French state did not recognize the events as war until 1999 by a resolution of the National Assembly, previously they were classified as police actions. From 1990, on the occasion of the Algerian civil war and the biographical statements of those involved and war victims, this view of history was questioned, which focused more on Algerian nationalism and Algerian society than on the military course.

Processing and remembrance

Public memory discourse in France

For a long time, the Algerian war was hardly discussed in public in France. Up until the 1980s there was little educational impetus. An indication of this is inter alia. the timely adoption of amnesty laws, which de Gaulle already took into account in the Evian treaties . In order to prevent possible legal proceedings against the French military, an amnesty for the Algerian combatants and supporters was agreed with Algeria. Algeria agreed to this because their acts of violence could no longer be judged in court and, on the other hand, Algeria was recognized as an independent war party. The French parliament then issued a first decree on March 22, 1962 regarding the Algerian war participants. A second decree was also not agreed in the Evian Treaties, but was nevertheless passed, which also exempted all war crimes committed by the French side, including torture, rape and collective retaliation. However, there was little resistance to the second decree, as the public was tense due to the end of the war and the flare-up of terror caused by the OAS . The historian Vidal-Naquet , on the other hand, criticized the inconsistent amnesty, which in his opinion should only serve to legitimize the French army. Nonetheless, Hüser (2005) notes that the amnesty laws were passed even faster after the Algerian war than after 1945. The crimes were not forgotten, but were no longer discussed in the media until the 1980s. At the same time, anti-amnesty opponents who wanted to campaign for the reappraisal threatened legal prosecution. This is illustrated by the trial of Jean-Marie Le Pen , who was involved as a lieutenant in the Algerian war and who was accused of torture in the Algerian war in the newspaper Le Canard enchaîné in 1984 . As a result of the second amnesty decree, Le Pen became the defendant in the trial, who was not threatened with conviction, but on the contrary was found to be right. Renken (2006) therefore sees the passing of two decrees on amnesty as "de Gaulle's trick, because even today it appears that it was not de Gaulle but 'Evian' who granted amnesty for torture."