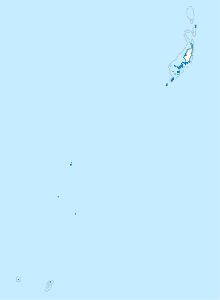

Babeldaob

| Babeldaob | ||

|---|---|---|

| Relief map of Babeldaob | ||

| Waters | Pacific Ocean | |

| Archipelago | Palau Islands | |

| Geographical location | 7 ° 32 ' N , 134 ° 34' E | |

|

|

||

| length | 45.8 km | |

| width | 15.4 km | |

| surface | 376 km² | |

| Highest elevation |

Mount Ngerchelchuus 242 m |

|

| Residents | 5185 (2015) 14 inhabitants / km² |

|

| main place | Melekeok | |

Babeldaob or Babelthuap , also on older maps: Baobeltaob, Baubelthouap, Banbeltbonap, Baberudaobu To , is the largest island in the Carolines archipelago and the largest in the island state of Palau in the western Pacific Ocean .

geography

The Palau Islands are located north of the equator in the Pacific Ocean, around 2000 km north of the Australian continent and are geographically part of the island region of Micronesia . Babeldaob is the largest island in the archipelago with 376 km². The roughly north-south oriented island is around 45 km long and up to 13 km wide. An extensive barrier reef runs along large parts of the west coast .

The major part of Babeldaob consists of rock of volcanic origin, mostly andesite and basaltic rocks . Babaeldaob has some not very extensive coastal plains, especially at the mouths of the rivers. Otherwise the landscape rises in gentle waves from the coast to the center of the island. The interior of the island consists mainly of densely overgrown hills. The highest point at 242 m is Mount Ngerchelchuus in the Ngardmau administrative district in the north.

The high amounts of rain are drained into the sea via rivers - the longest is the Ngerdorch River - and numerous smaller rivers. In some places they have spawned spectacular waterfalls. There are two small lakes on the island: Lake Ngardok not far from the town of Melekeok in the east with 48,000 m² and Ngerkall Pond in the Ngaraard administrative district with 4000 m².

There is a narrow strip of sandy beach at Melekeok on the east coast.

climate

The Palau Islands have a tropical and humid marine climate. The temperature in the coastal areas of Babeldaob rarely falls below 23 ° C, the annual average temperature is 28 ° C. As usual in the tropics, the rains are short and heavy. The average rainfall is between 272 and 531 mm per month. Most of the rain falls in April / May as well as in the winter months, which are climatically influenced by the north-eastern trade winds .

Flora and fauna

On Babeldaob there is a nature reserve - Ngardok Nature Reserve - which encloses the Ngardok Lake and its water catchment area. It was established in 1997 and covers around 4 km².

flora

The original flora of Babeldaob comes mainly from Asia . Because of the greater proximity to the continent, the high levels of precipitation and the fertile soil from the weathering products of volcanic rocks, the vegetation is more lush and species-rich than on the other islands of Micronesia .

The coastal vegetation consists of mangrove forests in large parts of the island . In addition to several mangrove species can be found here: Horsfieldia amklaal , a tree of the magnolia-like part, Cynometra ramiflora , a diminutive tropical tree, and Barringtonia racemosa , a medium-sized tree from the family of lecythidaceae . Hibiscus tiliaceus ( linden-leaved marshmallow ) has settled in disturbed areas .

The low, coastal regions have been completely remodeled over the centuries of human settlement, especially in the east of the island. In addition to residential development, you will mainly find garden land ( tapioca , sweet potato ), tree cultures ( breadfruit , papaya , mango , betel nut ), coconut groves and taro fields.

The high altitude is covered by a dense forest, which, however, is repeatedly interrupted by larger, savanna-like zones. This bush and grassland is the result of extensive interventions by the indigenous population in the environment. The indigenous people cleared and terraced the hills for the intensive cultivation of crops. Already in pre-European times, the cultivation areas were largely abandoned and a secondary, species-poor vegetation with bushes and robust grasses developed.

The forest areas on the high elevations are affected by intensive logging during the Japanese occupation. The tree fern Cyathea lunulata , Casuarina equisetifolis ( casuarina ) and Pandanus tectorius ( screw trees ) have established themselves as secondary forests . Undisturbed or undisturbed vegetation is most likely to be found on the west coast. There are still remnants of “typical” tropical rainforest with tall trees, covered with lianas and epiphytes , as well as a dense stand of ferns and moss . The remaining indigenous tree species include: Campnosperma brevipetiolata, Myristica insularis, Alphitonia carolinensis, Atuna racemosa and several glochidion species, all of which are quite impressive trees that shape the landscape.

fauna

There are saltwater crocodiles on Babeldaob . The animals breed in Lake Ngardok. The connection with the sea is made by the Ngerdorch River.

There are two species of bats : Pteropus muriannus pelewensis , a fruit- eating species, and Embullonura semicaudata palauensis , which feeds on insects. Both species are endemic and now threatened as they are caught by the locals and made into a soup with coconut milk or exported to the Mariana Islands . Another species, Pteropus pilosus ( soft-haired flying fox ), became extinct in the 19th century.

history

prehistory

Despite some archaeological excavations with several radiocarbon dates since the 1990s, the settlement history of the Palau Islands is still not sufficiently secured. It is believed that the indigenous people reached Babeldaob in several waves of immigration, from the Philippines, Indonesia and other Melanesian islands. When that happened is still unclear.

Bruce Masse, an environmental archaeologist at Los Alamos National Laboratory, New Mexico , dates the first settlement of Babeldaob to around the turn of the century . The dating of a human skull fragment from the archaeological site of Chelechol ra Orrak on Orrak Island, a small side island off the village of Airai in the southeast of Babeldaob, dates back to 800–890 BC. BC back. Relics that came to light on a road construction project could date back to 1400 BC. To be dated. The analysis of sediment samples from a taro field in 2000 could even show that human activities on Babeldaob continued into the early 2nd millennium BC. Go back BC.

Little is known about the early period of settlement; the natives probably first lived in small settlements near the coast and under rocky overhangs. With increasing population growth in the first millennium BC BC the people settled some distance from the coast, but still in the low coastal country. Settlement remnants from this period were found 1.0–1.5 km from the coastline.

Over time, a stratified tribal society developed, with aristocratic (large) families at the top, which relied heavily on male associations. The men met in large, elaborately built men's houses ( bai ) and were probably the organizers of the labor-intensive earthworks. In order to maintain the social balance, there were also women's associations in the villages, but they did not have such elaborately designed meeting houses and also had significantly less social influence.

The social substructure was organized in centers, larger villages that formed alliances with smaller, surrounding settlements in order to be able to dispose of a sufficient number of warriors. Such middle centers were Koror, Melekeok, Imeyong, and Imeliik (Aimelik).

From the turn of the ages, the inhabitants increasingly opened up the interior of the island by means of slash and burn and converted the hills into large areas of cultivated terraces. In the period between 500 and 1400 AD, a considerable number of such terraces were built on the entire island, which still shape the landscape today. The hills were not only used for agricultural purposes, but were also fortified residential complexes. Some of the terraced hills are flattened at the top and fortified with walls ( breastworks ?). They are large defensive structures surrounded by a circular moat . The V-shaped moat of Ngerulmud Hill near Melekeok, which was archaeologically examined in 1996, had a diameter of 100 m, was originally 7.5 m deep and 4 m wide.

The monumentality of the terraces, which can be seen from afar, made them structures dominating the landscape. This suggests that they were not only built for intensified food cultivation, but were also a manifestation of the power struggle for socio-political supremacy between rival groups. The spatial arrangement suggests that they also served as boundary markers for the tribal areas. Their location with unrestricted all-round visibility indicates a control and monitoring function in relation to the villages in the coastal zone.

The large number and size of the completely redesigned mounds of earth with six to eight terraces, as well as the immense workload associated with it, indicate an efficient, well-thought-out organizational structure and suggest a considerably higher population than today. Older publications speak of 40,000 to 50,000 residents.

In the 2nd millennium AD, construction work on the hillside terraces stopped, the reasons for this are unknown. Environmental influences were suspected, but a socio-political upheaval within society is more likely. Instead, the residents settled in open villages without completely abandoning the terraces. They were integrated into the villages, e.g. B. planted with usable trees or rededicated for residential development. The German explorer Karl Semper counted 235 villages at the end of the 19th century, 151 of which had already been abandoned. Today they can be archaeologically proven by means of stone terraces, stone platforms, paved paths and stone sarcophagi .

The relics of the villages that are visible to tourists are anthropomorphic megaliths , which are found in considerable numbers all over the island. In the administrative district of Melekeok on the east coast, near the village of Ngermelech, which has barely a dozen houses, there are seven sculptures (out of nine originally) made of andesite, arranged in two parallel rows in an area of around 30 × 10 m not far from the coastline. They have roughly crafted, anthropomorphic faces whose large, round eyes are reminiscent of owl eyes . The purpose of the statues is unknown; they may be the foundation pillars of a representative house. The 1 m to 2.7 m high stone figures have names and are woven into local legends.

There are more megaliths near Bairulchau in the far north of Babeldaob. On the area there are a total of 52 upright stones, also made of andesite. 25 of them (originally 36) are arranged in a 54 m long colonnade . They probably formed the elevated foundation of a bai , a meeting house for men. Some of these houses were still in use during the German colonial era. Semicircular recesses at the top of the megaliths suggest that they once supported a beam scaffolding on which the floor of the house rested. To the south-east of this there is another row of columns with 12 stones and to the north-west a small, 8 m high earth pyramid. A radiocarbon dating from excavations revealed an age of the site of 1,800 years. Similar houses, called latte , resting on large stone pillars , existed in the Marianas 1,300 km to the northeast .

Other stone testimonies of the indigenous people are petroglyphs , which can be found all over the island, with simple, graphic and anthropomorphic signs and symbols that are perhaps the preliminary stage of writing.

European discovery

As early as the 16th century, a currency made of glass and ceramic beads that were not made on the islands was circulating on the Palau Islands. They probably came from the Philippines , which had been a Spanish colony since 1565. This shows a very early trade between Micronesia and the Philippine Islands. Before the Europeans could establish themselves on Babeldaob, their products were already known there.

The Spanish navigator Ruy López de Villalobos probably discovered Babeldaob and the surrounding islands for Europe in January 1543. Presumably he did not see Babeldaob himself, but only the coral reef off the coast, as can be deduced from the name “Los Arrecifes” (dt .: the reefs ).

It is also possible that Francis Drake reached Babeldaob with the Golden Hinde during his circumnavigation of the world in 1579. Nevertheless, little was known about the Palau Islands in Europe until the beginning of the 18th century.

Catholic missionaries who had lived in the Philippines since the 16th century received information from shipwrecked people in the Carolines about a group of islands east of the Philippines and decided to Christianize their inhabitants. 1710 reached Santissima Trinidad under the command of Francisco Padilla the Sonsorol Islands and sat two Jesuit -Missionare from. However, the Santissima Trinidad was carried away by adverse winds and landed on the coast of Babeldaob. The further fate of the missionaries is unclear. Don Bernardo de Egui , who was sent from Guam on the ship Santo Domingo de Guzman in 1712 and landed on Babeldaob, was also unable to explain their whereabouts.

The American whaling mentor from New London ran aground and sank on the barrier reef west of Babeldaob in 1832. Several crew members, including the seaman Horace Holden, were able to save themselves on Babeldaob. There they lived among the locals for several months and built a boat with which they wanted to sail to Canton in China. However, they got caught in a storm, drifted and landed on the island of Tobi , where they were captured. They were rescued from the British ship Britannica in 1834 . Horace Holden published a book about his adventures in 1836, which for the first time made Babeldaob known to a wider audience in the western world.

Babaeldaob was nominally part of the Spanish colonial empire , even if significant colonization and administration did not take place until the late 19th century. When Spanish Capuchins were commissioned by Rome to evangelize the Carolines at the end of the 19th century , the Palau Islands came again into the focus of the mission. On the way to Yap, seven missionaries of the Spanish Capuchins explored the island of Koror and were warmly received. On April 28, 1891, the merchant schooner Santa Cruz brought two missionaries from Yap to Koror to establish the first permanent mission station. At first they were not very successful in Christianizing the natives. When a flu epidemic broke out in 1892 and numerous islanders became seriously ill and died, this was an occasion to turn away from the old, animistic local religion and turn to the Christian religion. The first church with a mission school was opened on Koror in 1892, but in April 1893, Father Luis de Granada built a chapel dedicated to St. Joseph of Nazareth in Ngarchelong on the northern tip of Babeldaob. A mission school was built the year after. Further mission stations in Chelab, Ngaraard and Melekeok followed within a short time. Melekeok became the center of the mission on Babeldaob until the station was destroyed by a typhoon on Easter Sunday 1922 . After that, the missionaries concentrated on the more populated Koror.

German colony

After the defeat in the Spanish-American War , the Kingdom of Spain sold the Palau Islands to Germany. After the German-Spanish treaty was signed on February 12, 1899, the Spanish government of Babeldaob and the rest of the Palau Islands as well as the Carolines and Marianas ceded to Germany. By law of July 18, 1899, Kaiser Wilhelm II declared the islands a German protected area . Babeldaob belonged to the administrative district of the West Carolina and was subordinate to the district administrator on the island of Yap. The German administration on the South Sea islands was always equipped with very few staff. In the initial phase of colonization on Yap, there were only two Germans with eleven local police soldiers. It was not until 1905 that Wilhelm Winkler, his own administrator, came to Palau. He resided on the island of Koror and was also responsible for Babeldaob.

After the Spanish mission, the inhabitants of the Palau Islands were predominantly Catholic. With the establishment of the German colonial administration, responsibility passed from the Spanish Capuchins to the brothers of the Rhenish-Westphalian order province. There was a German mission school in Melekeok.

During the German colonial period, the Hamburg South Sea Expedition , initiated by Georg Thilenius , explored Babeldaob and the other Palau Islands from 1908–1910 and brought numerous museum objects to Germany.

Japanese mandate

After the Japanese Empire declared war on the German Reich in 1914, the Japanese occupied the German colonies in Micronesia between September 29 and October 21, 1914 without encountering any resistance. The German officials and mostly the settlers and missionaries had to leave the islands.

As a result of the Versailles Peace Conference , the mandate powers for the German colonies were announced on May 7, 1919 . Japan received the League of Nations mandate over the Palau Islands, but had to undertake not to set up any military bases and not to set up a native army.

The Japanese administration in the Palau Islands was fraught with prejudice. The islanders were considered lazy and third class people (santo kokumin). For economic development, colonists from the Okinawa Islands settled on Babeldoab for the mining of bauxite and extensive logging in the previously untouched forests .

In 1933 the Japanese Empire withdrew from the League of Nations, whereby all obligations of the mandate power towards the League of Nations became null and void. From the 1930s onwards, Babeldaob was militarized.

The Second World War and the time after

Main article → Battle of the Palau Islands

When the Pacific War began on December 7, 1941, the remote Palau Islands, which were now heavily fortified by the Japanese , were initially unaffected. There were Japanese garrisons on Babeldaob with a total of over 20,000 military personnel, far more than the island's population. In addition, the Japanese had armed the island with coastal batteries , anti-aircraft cannons , forts and shelters against an invasion.

In 1944 the US Navy bombed the Japanese facilities on Babeldaob and the islands of Koror, Peleliu and Angaur. However, the US landing operations in 1944 were concentrated on the islands of Peleliu (→ Battle of Peleliu ) and Angaur (→ Battle of Angaur ). Babeldaob remained under Japanese occupation until the end of the Pacific War. Most of the casualties among the island's native population were not caused by the almost daily bombing attacks, but by poor living conditions, malnutrition, diseases and a lack of medical care.

Numerous volunteers from Palau served as auxiliaries in the Japanese military and were sent to other islands in the Pacific during the war. After the fighting ended, it took them years to return to their homeland. The fate of the men of the 104th Construction Detachment, who were stranded in New Guinea and were only able to return to the Palau Islands a few years after the end of the war, was dramatized in a Japanese film .

With the end of the Second World War , Palau and a large part of Micronesia became " Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI) ", a United Nations mandate under US administration, in July 1947 . On October 1, 1994, Palau proclaimed its independence, and Koror became the capital .

The Koror – Babeldaob Bridge , which was completed in 1977 and connected the islands of Babeldaob and Koror, was the longest prestressed concrete bridge in the world at the time . After renovation work, the concrete bridge collapsed on September 26, 1996. Two people died and four were injured. The 413 m long "Japan-Palau Friendship Bridge", an extradosed bridge opened in 2002 , replaced the destroyed structure.

Administration and Infrastructure

Ten of the sixteen administrative units (called "States") of the Republic of Palau are located on the island of Babeldaob:

- Airai

- Aimeliik

- Ngeremlengui

- Ngerchelong

- Ngchesar

- Melekeok

- Ngiwal

- Ngaraard

- Ngardmau

- Ngatpang.

After independence in 1994, Koror was initially the capital of the Republic of Palau on the neighboring island of the same name. The small town of Melekeok with 391 inhabitants (as of 2005) has been the capital since 2006 and replaced the much larger Koror in this function.

Babeldaob is the largest but not the most populous island in Palau. Two thirds of all residents of the Republic of Palau live on the much smaller, urban neighboring island of Koror. In 2000 the population of the 10 administrative districts on Babeldaob was 4,867 people who live in 47 villages. Babaldaob suffers from permanent population decline. Many younger people are drawn to the neighboring Koror, which is still the administrative and economic center of the republic. In addition, there is a significant emigration to Guam , because one hopes for jobs there with the United States Air Force and the American administration, as well as to study in the USA.

On Babeldaob there are schools for all degrees up to university entrance qualification. However, the school system is strongly influenced by private denominational schools. The island state of Palau does not have a university, only a college , the "Palau Community College" on the island of Koror.

The most important infrastructure project for Babeldaob, which was tackled in the 1990s with funds from the United States , was the construction of the 95 km long, paved ring road that connects the villages in the coastal lowlands and crosses the Koror-Babeldaob Bridge to the The neighboring island of Koror leads. The United States Army Corps of Engineers was responsible for planning and coordinating the construction work .

Babaeldaob-Koror International Airport ( ICAO code : PTRO, IATA code : ROR), the former US military airfield with a 2195 m long asphalt runway and a small terminal building, is located near the town of Airai in the south by Babaldaob.

Tourism in Palau is mainly limited to Koror and the nature reserve of the Chelbacheb Islands . Mostly it is diving or cruise tourism. Babeldaob is rarely visited.

Remarks

- ↑ Both spellings can be found, the former is used in official language and z. B. used on the Internet site of the Republic of Palau and is also common in the Anglo-American language area

Individual evidence

- ↑ a b [1]

- ↑ Yimnang Golbuu et al .: Effects of Land-Use Change on Characteristics and Dynamics of Watershed Discharges in Babeldaob, Palau, Micronesia . In: Journal of Marine Biology. January 2011, p. 5.

- ^ A b Joan E. Canfield: Palau: Diversity and Status of the Native Vegetation of a Unique Pacific Island System. In: Clifford W. Smith (Ed.): Cooperative National Park Resources Studies. University of Hawaii, Department of Botany, Honolulu (HI) 1980, pp. 41-51.

- ^ A b Dieter Mueller-Dombois & F. Raymond Fosberg: Vegetation of the Tropical Pacific Islands. Springer Verlag, New York / Berlin 1998, ISBN 0-387-98285-X , pp. 278-281.

- ^ A b c Patrick Vinton Kirch: On the Road of the Winds - An Archaeological History of the Pacific Islands before European Contact. University of California Press, Berkeley 2000, ISBN 0-520-23461-8 .

- ↑ GJ Wiles, J. Engbring and D. Otobed: Abundance, biology, and human exploitation of bats in the Palau Islands. In: Journal of Zoology, Volume 241 (2), February 1997, pp. 203-227

- ↑ a b Atholl Anderson et al .: Comparative Radiocarbon Dating of Lignite, Pottery, and Charcoal Samples from Babeldaob Island, Republic of Palau . In: Radiocarbon. Vol 47 (1), University of Arizona 2005, pp. 1-9.

- ^ WB Masse: Radiocarbon dating, sea-level change and the peopling of Belau, Micronesica. In: Micronesica Supplement 2, Ed .: University of Guam, 1990, pp. 213-230.

- ^ Scott M Fitzpatrick: AMS Dating of Human Bone from Palau: New Evidence for a Pre-2000 BP Settelement. In: Radiocarbon. Vol 44 (1), University of Arizona 2002, pp. 217-221.

- ↑ DJ Welch: Early upland expansion of Palauan settlement. In: Stevenson, Lee & Morin (Eds.): Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference on Easter Island and the Pacific. Easter Island Foundation Los Osos, California 2000, pp. 164-77.

- ^ A b c d William N. Morgan: Prehistoric Architecture in Micronesia . University of Texas Press, Austin (TX) 1989, ISBN 0-292-76506-1

- ↑ a b c d Stephen Wickler: Terraces and Villages: Transformations of the Cultural Landscape in Palau. In: Thegn N. Ladefoget, Michael W. Graves (Eds.): Pacific Landscapes. Archaeological Approaches. Easter Island Foundation, Los Osos 2002, ISBN 1-880636-20-4 , pp. 65-96.

- ↑ Meyers Konversationslexikon. 1897, Volume 13, p. 429.

- ^ Karl Semper: The Palau Islands in the Pacific: Travel experiences. Verlag FA Brockhaus, 1873. (Reprint: Nabu Press 2010, ISBN 978-1-147-63116-6 )

- ^ A b c d Steven Roger Fischer: A History of the Pacific Islands. Palgrave, New York 2002, ISBN 0-333-94976-5 .

- ↑ James Burney: A Chronological History of the Discoveries in the South Sea or Pacific Ocean, Part 1. Luke Hansard, London 1813, p. 233.

- ^ Samuel Bawlf: Secret Voyage of Sir Francis Drake 1577-1580. Walker & Co., New York 2003, ISBN 1-55054-977-4 , p. 363.

- ↑ Max Quanchi, John Robson: Historical Dictionary of the Discovery and Exploration of the Pacific Islands. The Scarecrow Press, Lanham (MD) 2005, ISBN 0-8108-5395-7 , p. 132.

- ↑ Michiko Intoh: Historical significance of the Southwest Islands of Palau. In: Geoffrey Clark (ed.): Islands of Inquiry - Terra Australis 29, Australian National University Canberra, 2008, ISBN 978-1-921313-89-9 , pp. 325–338.

- ^ John Dunmore: Who's who in Pacific Navigation, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1991, ISBN 0-8248-1350-2 , p. 94.

- ↑ Horace Holden: A Narrative of the Shipwreck, Captivity and Sufferings of Horace Holden and Benj. H. Nute who were cast away in the American ship Mentor, on the Pelew Islands, in the year 1832. Russel, Shattuck & Co., Boston 1836.

- ^ Francis X. Hezel SJ: The Catholic Church in Micronesia: Historical essays on the Catholic Church in the Caroline-Marshall Islands. Publication of the Micronesian Seminar, Pohnpei [2]

- ↑ a b German Colonial Lexicon . Volume 3, Quelle & Meyer, Leipzig 1920.

- ^ Markus Schindlbeck: Germans in the South Seas . In: Paradises of the South Seas - Myth and Reality , catalog for the exhibition of the same name in the Roemer- und Palizaeus-Museum Hildesheim, Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz 2008, ISBN 978-3-8053-3915-5 , pp. 35-48

- ^ Augustin Krämer : Results of the South Seas Expedition 1908-1910. Volume 3: Ethnography Micronesia. Volume 1–5: Palau. Friedrichsen & Co, Hamburg 1917.

- ↑ a b Hermann Joseph Hiery : The First World War and the end of German influence in the South Seas. In: Hermann Joseph Hiery (Ed.): Die Deutsche Südsee 1884-1914. Verlag Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2001, ISBN 3-506-73912-3 .

- ^ Karen R. Walter: Through the Looking Glass. Palau Experiences of War and Reconstruction 1944-1951. University of Adelaide, 1993.

- ↑ Mark R. Peattie: Nan'yô. The Rise and Fall of the Japanese in Micronesia, 1885-1945. University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1988, ISBN 978-0-8248-1480-9 , p. 347.

- ↑ Kimie Hara: Micronesia and the Postwar Remaking of the Asia Pacific: "An American Lake". In: The Asia Pacific Journal , Volume 5 (8), Number 0 from August 2007 (online at: japanfocus.org )

- ↑ M. Pilz: Investigations into the collapse of the KB bridge in Palau . In: Concrete and reinforced concrete construction. Volume 94 (5), May 1999, pp. 229-232.

- ^ World Aero Data