Hans Böhm (Timpanist from Niklashausen)

Hans Böhm or Hans Behem , Pauker von Niklashausen (* around 1458 in Helmstadt ; † 19 July 1476 in Würzburg ) - also known as Pfeifer von Niklashausen , Pfeiferhannes , Pfeifergehannes or Henselins - was a cattle herder , musician , preacher and initiator of the Niklashaus pilgrimage from 1476.

In the spring of 1476, the hitherto insignificant herdsman Hans Böhm called on people to make a pilgrimage to Niklashausen . He promised the pilgrims, in the name of the Virgin Mary, complete indulgence from their sins. He also proclaimed the social equality of men, common property and God's judgment over the vanity and insatiable greed of princes and high clergy. His sermons affected the soul of the people, so that enthusiastic listeners revered him as a “holy youth” and “ prophet ”. In the short period of three months he is said to have gained more than 70,000 followers. The ecclesiastical and secular authorities followed the emerging mass movement with great concern. By order of the Würzburg Prince Bishop Rudolf II. Of Scherenberg Hans Böhm was arrested, in summary proceedings as a heretic sentenced to death and on 19 July 1476 Würzburg on the pyre burned. Because of his capture, there was a brief, spontaneous mass protest among the Franconian rural population.

Origin and childhood

The name Böhm, mostly written Behem, Beheim or Böheim in the late Middle Ages, indicates that the ancestors of Hans Behem came from Bohemia . During the Hussite Wars from 1415 to 1435, many war refugees from Bohemia came to Franconia . Most of these behem had to reorganize their lives as poor have-nots at the lower end of the class order.

Hans Behem or Böhm, who came from a very poor background, was born around 1458 in Helmstadt in Lower Franconia , a small market town in today's district of Würzburg . There is no reliable knowledge of his origin and childhood. He is said to have grown up as an orphan and had to make a living as a child. As a shepherd boy, he experienced the lawlessness under which the dispossessed hired themselves in the late Middle Ages . Even before his time as a preacher, the self-confident, eloquent boy was known to many people in the villages between Würzburg, Wertheim and Tauberbischofsheim as a shepherd and a drummer . He heard what the people in the lower Main Valley were saying about God and the world, about the plight of ordinary people, the heresies of the Hussites and the deadly sins of the secular and ecclesiastical authorities. He went about with the flock, learned to speak to people, imagined a more godly, better world order for himself and sought certainty about his ideas.

Hans Böhm would have remained an insignificant contemporary and would have long been forgotten today. That did not change until Lent 1476, when, in adolescent enthusiasm - contemporary sources describe him as a youth, almost still a child - he decided to act as a preacher in Niklashausen.

Revival to preacher

Two explanations for the preaching career of Hans Böhm have been handed down. From today's point of view, both are plausible, although he indiscriminately admitted or revoked details under the torture .

Conversion through an apparition of Mary

In all sermons Hans Böhm spoke about his Marian apparitions . In spite of the Church's accusations, a conclusive scenario emerges from the traditions. After Mardi Gras in 1476, Hans Böhm returned to the pasture, set up camp in a cave near the herd, and in a dream the Virgin Mary appeared to him .

The appearance of Mary heralded an imminent judgment of God against all sinners. She told him to call on people to repent in front of her little church in Niklashausen . He was also to proclaim that all believers who came to the church in Niklashausen in adoration and humility to the grace image of the Mother of God received just as perfect indulgence from their sins as those who made pilgrimages to the Pope in Rome. According to his own statements, he had apparitions of Mary several times.

Conversion by a clergyman

After his capture, Hans Böhm confessed during interrogation that he had been converted to a preacher through the encouragement of a clergyman. It remained unclear whether it was only the local chaplain who, with the help of the eloquent young man, wanted to enliven the pilgrimage to Mary's image of grace, or whether the unknown monk of a mendicant order , who was arrested with Hans Böhm, had the decisive influence on him.

From stories and conversations with this clergyman, Hans Böhm knew of a "Holy Father of the Barefoot Order" who had traveled through Franconia in earlier years. His sermons were so convincing that many listeners voluntarily renounced worldly distractions and possessions and turned to a more godly life.

Hans Böhm wanted to follow the example of this "Holy Father" with the support of his spiritual advocate and with the great persuasiveness of his own social utopia .

Time as a preacher

During Lent 1476, Hans Böhm made the decision to follow his ideas and inspirations. He wanted to proclaim a better world to people with his devotion to Mary. Sometime between the fourth Sunday of Lent Laetare , March 21, and the day the cross was found, May 3, the traditions are different, Hans Böhm stepped in front of the little church in Niklashausen, burned his kettledrum in front of the astonished congregation and gave his first fascinating one Sermon. The invitation to the Marian pilgrimage to Niklashausen and his message of a new world order spread like wildfire . After only a week, many pilgrims from the surrounding area came to Niklashausen to ask the Virgin Mary for mercy and to hear the young preacher's message. This proclaimed that everyone should first say goodbye to their own sins so that a better world might arise. As a visible sign of atonement , he asked for jewelry, silk cords, breast cloths, pointed shoes and other trinkets as offerings. A large part of the offerings, such as items of clothing, braids, hairnets , musical instruments, toys, etc. went the way of his kettledrum. They were publicly thrown at the stake and burned. After these symbolic proofs of atonement , he preached to the pilgrims a new kingdom of God on earth with the following central ideas:

- The greed of the nobility and the high clergy is threatened with imminent ruin by a terrible judgment of God.

- Everyone should his living with his own hands work to earn and share fraternally with the needy.

- Class differences , taxes and compulsory labor are to be abolished.

- The private and sovereign ownership of fields, meadows, pastures, forests and bodies of water are to be transferred to the commons .

These seemingly communist visions inspired the people and attracted more and more pilgrims. Initially, Hans Böhm only preached on Sundays and public holidays and climbed onto a barrel or an overturned tub.

At the end of May 1476, Count Johann III notified . Wertheim the Archbishop of Mainz, Diether von Isenburg pilgrimage that increasing crowds to Niklashausen because there a youth had a Marian apparition and performing as a preacher great appeal. The archbishop apparently shared the concern of the Count of Wertheim and instructed the Würzburg prince-bishop to take care of the Niklashaus pilgrimage urgently. Würzburg was closer to the place of pilgrimage, and the young preacher from Helmstadt was Würzburg's subject. The bishops actually had no objection to pilgrimages to the little church in Niklashausen. The little church had been consecrated to the Virgin Mary since 1344, and since 1353 there was a letter of indulgence issued by the papal clergy in Avignon . This letter of indulgence, which the Archbishop of Mainz, Gerlach von Nassau , had confirmed on April 12, 1360, guaranteed every person 40 days of indulgence from all sins when they made a pilgrimage to Niklashausen to the image of Mary.

However, the modest framework of the Niklashaus pilgrimage by Hans Böhm was completely out of joint within a few weeks. According to the Würzburg historian Lorenz Fries , a huge field camp was built near Niklashausen in June 1476. It is said to have housed around 40,000 people, not taking into account the daily entries and exits. In comparison, the city of Würzburg had around 5,000 inhabitants at that time. The pilgrims, mostly men, women and children from the rural population, came not only from the lower Main Valley, but increasingly from all over Franconia , from Bavaria , Thuringia and Swabia , from the Rhineland and even from Alsace . Because of the large number of people, Hans Böhm had to light the stake and preach about it several times a week in June. In order to be able to overlook the assembled crowd, he now mostly delivered his sermons out of skylights.

While offerings piled up in the church in Niklashausen in June 1476, the bishops in Mainz and Würzburg had to note with dismay that a permanent pilgrimage with mass effects was established in their sovereign territory, about which they knew nothing. The Würzburg Episcopal Councilor Kilian von Bibra and the cathedral preacher Sigismund Meisterlin therefore went to Niklashausen to question the preacher, who was not impressed by it. Kilian von Bibra then sent a couple of experienced, Bible-based believers to Niklashausen in mid-June to expose the young preacher to the crowd as a charlatan . In several speech duels, however, Hans Böhm demonstrated his rhetorical skills. None of the clergymen sent was equal to the sincerity and skillful argumentation of the young preacher, who was assisted by a monk in theological questions. With scorn and ridicule from the public, they fled in the direction of Würzburg to report.

After the reports about the Niklashaus pilgrimage in Würzburg, Bishop Rudolf II. Von Scherenberg and his councilors sought support from the neighboring towns and sovereigns. Although the Niklashaus pilgrimage was apparently peaceful, the requests for help conjured up the specter of peasant uprising. To mobilize the Bavarian and Swabian rulers, the Würzburg canon Georg von Giech even spread the rumor that warring federal farmers were moving from Switzerland to Franconia in order to ally themselves with pilgrims from the Niklashaus. These and other false reports convinced the initially hesitant city councilors and sovereigns of the supposed danger that was brewing in Niklashausen. The citizens and children of the country were not allowed to take part in the Niklashaus pilgrimage. Regardless of this, the flow of pilgrims did not stop.

Capture

At a meeting in Aschaffenburg at the end of June 1476, the Mainz and Würzburg episcopal councils jointly decided to forbid the Niklashaus pilgrimage on the part of the church and to arrest Hans Böhm and the monk who advised him, who was not known by name . At the same time they decided to send informers and provocateurs to Niklashausen to find reasons to justify these measures. A few days later, as requested, several reasons for Böhm's arrest were put forward. It was reported that Boehm made heretical and inflammatory speeches and used fraudulent miracles. The guiding principles of his sermon on July 2nd were handed down in a total of 19 points, here in extracts, in the following sense of the word:

- "How the Virgin Mary appeared to him, revealing the wrath of God against the human race and especially against the clergy."

- "That God wanted to punish sinners by freezing grain and wine on the day of the cross, but averted this through his prayers."

- "Like so great perfect grace in the Taubertal, more than in Rome or anywhere else."

- “That he thinks nothing of purgatory; and if a soul were in Hell, he would want to lead it out by hand. "

- "He wanted to improve the Jews first, then the clergy and the literacy / scholars."

- "How the emperor was a villain, and nothing with the Pope either."

- "Let the emperor give a prince, earl, knight and servant ecclesiastical and secular customs and taxes over the common people - alas, you poor devils."

- “The clergy have many benefices; that shouldn't be; they should be beaten / slain. "

- "It will happen that the priest covers the tonsure with his hand so that he is not recognized as such."

- "How the fish in the water and the game in the field should be shared property."

- “If the princes, clerical and secular, including counts and knights, had as much as the common man, then everyone would have enough; that must then happen. "

- "It happens that the princes and lords still have to work for a day's wage."

- “The priests say I am a heretic and want to burn me. If they knew what a heretic is, they would recognize that they are heretics themselves and I am not. "

- "But if you burn me as a heretic, you will find that you are burdening yourself with great guilt that will fall back on you."

- “He says there is no ban before God ; and the priests divorce what only God and no one else can do. "

Although the intelligence reports of July 2nd gave sufficient reasons, 11 days passed before the arrest. On the night of July 13th - unnoticed by most of the pilgrims - 34 episcopal horsemen came to Niklashausen and, as agreed, secretly captured the two delinquents . The arrest of the unsuspecting preacher and the monk, who were surprised in their sleep, went smoothly with the help of informers. The captors with the bound and gagged prey were able to leave without any noise or fuss. There were no guards and no armed pilgrims, only a few eyewitnesses, but they did not intervene.

Since Helmstadt belonged to the Würzburg rulership, Hans Böhm was kidnapped to Würzburg that same night and imprisoned in the Würzburg Castle on the Frauenberg. The Niklashaus monk was under the jurisdiction of the Archbishop of Mainz and was therefore brought to Aschaffenburg.

According to records that were only written down in August 1476, Boehm is said to have asked the men in a sermon on July 7th to come back on Sunday, July 14th, with weapons but without women and children. With this news, Kilian von Bibra then convinced the prince-bishop to have Böhm arrested as soon as possible. Since, according to all written records, such an accusation was never raised against Böhm during the trial, historians today assume that this is a subsequent reason for conviction within the framework of a targeted disinformation policy of the Würzburg bishop. Possibly the prohibition of the Niklashaus pilgrimage, which continued in August 1476 and thus kept the memory of the “Holy Young Man” and “Prophet” alive in the people, should be given greater emphasis.

Liberation attempt and outrage in the wake of the Pauker von Niklashausen

When the pilgrims heard of the arrest of their “Holy Young Man” and “Prophet” on the morning of July 13th, there was great confusion. Since at first nobody knew where Böhm had been kidnapped and what was to happen next, many pilgrims made their way home. In the pilgrims' camp there was no sign of an impending armed uprising, which Boehm supposedly planned for July 14th. During the day the news spread that Hans Böhm was being held prisoner in Würzburg Castle. By evening 16,000 pilgrims had gathered and marched to Würzburg, singing Christian songs. Throughout the night they carried 400 large, burning votive candles that were visible from afar , which they wanted to donate to the miraculous image of Mary.

In the early morning of July 14th, the pilgrims arrived in front of the Würzburg Castle, including numerous women and children. Prince-Bishop's Court Marshal Jörg von Gebsattel , known as Rack , had ridden towards them accompanied by armed servants and blocked the way across the Main and into the city of Würzburg for those arriving. He made sure that the surprised and curious citizens of Würzburg, among whom supporters of the “Holy Young Man” were suspected, stayed in the city and could only watch what was happening from a distance. When meeting the pilgrims, Jörg von Gebsattel asked about the reason and the progress of the rampant procession and started negotiations with some of the pilgrims' educated and contentious spokesmen. The nobles Kunz von Thunfeld , his son Michael, two gentlemen from Stetten and one gentleman from Vestenberg spoke for the pilgrims . They threatened the court marshal to surrender the “Holy Young Man”. Jörg von Gebsattel retired to the castle with the message that the pilgrims wanted to hold out with chants and prayers until the “Holy Youth” and “Prophet” were among them again.

In the castle on what is now the Marienberg Fortress , no one expected such a mass protest. But the majority of the pilgrims were peasants, appropriately unarmed, who posed no serious military threat. Since the mass assembly was generally peaceful, Konrad von Hutten went to the pilgrims as a representative of the prince-bishop. He explained that Hans Böhm stayed in the castle as a subject of the prince-bishop and - like most of the pilgrims - owed his ecclesiastical and secular prince obedience. Rudolf von Scherenberg wanted to hear the message of the young preacher and therefore had him brought to him. The gates were kept closed as a precaution, as there would be a large crowd if the many people wanted to enter the castle, and the walls were reinforced to prevent the rash from entering. For this reason they would not be able to cross the Main behind the city walls. Konrad von Hutten appeased the pilgrims soothingly not to revolt unduly against the secular and clerical authorities and to return home. After his soothing words, the situation below the castle visibly relaxed. Without suspicion, the crowd broke up into smaller groups and left.

After Konrad von Hutten returned to the castle, however, the events took a violent, bloody turn - surprising for the pilgrims. Cannons were fired from the walls of the castle at the retreating people who fled in panic . The abbot Johannes Trithemius wrote in 1514 that the cannonade killed some pilgrims and wounded many. After the cannonade, the episcopal horsemen went into pursuit to catch defiant, possibly violent spokesmen. When the persecuted resisted the arrests, the riders are said to have stabbed a total of twelve men and wounded many. The chase probably ended with more than twelve fatalities. There are traditions according to which Würzburg riders slew a large number of men, women and children who had sought refuge in the Büttelbrunn churchyard about 5 km west of Würzburg . There are different statements about the number of prisoners. There is talk of 100 to 300 men. With the exception of two farmers who were suspected of leadership, most of the prisoners were released after a few days. After the horror that the cannonade, the cavalry attack and the long-range persecution left behind the unorganized fleeing pilgrims, any further fear that Niklashausen could ever lead to an armed peasant revolt was superfluous. Kunz von Thunfeld and the other pilgrims' spokesmen then stayed in hiding for a long time. The country was quiet again. The knight Kunz von Thunfeld and his son Michael had to swear to the bishop Urfehde that they would not take revenge for the disgrace they had suffered and that they transferred their possessions to the Würzburg bishopric.

Interrogation, trial and execution

When the henchmen delivered Hans Böhm to Würzburg Castle on the morning of July 13th, he was certain of the death sentence based on the charges that had been prepared. In his sermons he always referred to the miracle of the apparition of Mary. This was interpreted for him not only as a lie, but as heresy, which was punishable by death by fire. The other principles of his sermon of July 2nd, which were available as an informant report, were not seen as a Christian criticism of social grievances, but as a call for the violent overthrow of the powerful and rich. It bore the death penalty by beheading or hanging. Despite this clear legal situation, the episcopal officials initially assumed that the interrogation and trial would take longer, as a larger conspiracy against the church and God-willed authorities had to be uncovered. Many questions still had to be answered, e.g. B .:

- If Böhm was a member of an apostate religious community, he preached for the Waldensians or Hussites ; who were his idea providers?

- Were there clerical backers who, with him, chose the Niklashaus pilgrimage of all places for proselytizing the apparently numerous followers, who helped organize this permanent mass event?

- Which people or even communities had conspired to his faith, what obligations had they entered into, were there plans for armed rebellion?

- What did his backers and he intend to do with the treasure trove piled up in Niklashausen?

It was expected that answers to these questions would lead to further arrests, confrontations and additional culprits. In the first questioning, however, the officers did not, as expected according to the report, come across a heretic who was washed up with the water . Rather, they saw a frightened young man who did not seem to know that he had burdened himself with serious guilt.

This picture did not change during the interrogation that followed. Hans Böhm turned out to be illiterate , understood only a few Latin words and could neither recite the Our Father nor the creed . During several embarrassing interviews , he said the following:

- He grew up as an orphan in the community, met many people from childhood on, but about whom he did not know anything bad to report. Before he began to preach in Niklashausen, he had served as a cattle herder in several villages and had often played the drum.

- He has always confessed his sins and is not aware of any open guilt. He believed in the Holy Trinity and in the Virgin Mary, who appeared to him in the pasture. She told him to come to her miraculous image in Niklashausen and speak to the people.

- What he preaches about God and the world has long been within him. Even earlier as a cattle herder he had put these ideas into words and entrusted them to a clergyman. He assured him in conversations that these were Christian thoughts that he should talk about in public with a clear conscience. The clergyman told him that those words reminded him of a "Holy Father of the Barefoot Order". He preached so convincingly that the audience voluntarily renounced worldly possessions and began to lead a more godly life. The clergyman had also promised him spiritual assistance if he wanted to speak to the people following the example of this holy preacher.

A few days after the arrest, the investigators in Würzburg received news about the statements of the arrested monk from Aschaffenburg, and it became clear that the “Holy Father of the Barefoot Order” was Johannes Capistranus . In 1451 Pope Nicholas V sent him via Franconia to Bohemia and Silesia , where he was supposed to convert Jan Hus's followers to the Catholic faith. Many people from Silesia, Poland , Saxony , Pomerania and even Denmark , Courland and Livonia had flocked to Wroclaw to attend the moving sermons of St. Capistranus . Like the accused Hans Böhm, Capistranus had persuaded peasants, citizens and nobles to publicly burn games, books and luxury items at the stake and to donate abundant offerings as penance . Rudolf von Scherenberg, who is known to be an extremely prudent and level-headed regent , recognized the dilemma . He arranged for the investigation to be terminated immediately and the process to be ended quickly.

Because Hans Böhm - without knowing it himself - appealed to Capistranus, this outstanding representative of the Catholic Church, further research to uncover a larger conspiracy had become pointless. In the interests of the church, the prince-bishop refrained from further knowledge, which the Würzburg historian Fries and many other historians later regretted.

After the peaceful procession of the pilgrims in front of the Würzburg Castle on July 14th and the interrogation of the men captured afterwards, further questions to Hans Böhm about a deeper conspiracy or an impending peasant uprising were superfluous. Böhm was just an exceptionally charismatic lay preacher who saw his effect on people, but who had not (yet) pursued any concrete goals. The huge crowd in Niklashausen was actually just a pilgrimage. However, after the sensation that the Mainz and Würzburg clergy had caused among the surrounding rulers, these simple truths could no longer be conveyed, unless one exposed oneself to general ridicule. Therefore, the verdict on the "Pauker von Niklashausen" had to be pronounced and enforced as quickly as possible.

The place of execution was prepared on the fourth day of Böhm's arrest. At the same time, the citizens of Würzburg received the announcement that the Niklashaus pilgrimage and the crowd that they had experienced three days ago in front of the city were the work of the devil . Let the devil's servant be recognized and taken as the main culprit. The just punishment awaits him in three days. On Friday, July 19, the verdict on Hans Böhm was pronounced. With the help of the devil he faked Marian apparitions and bewitched the honorable pilgrims in Niklashausen with his sermons . Therefore, he was irrevocably guilty of heresy and should be publicly executed at the stake.

Together with two farmers who had been arbitrarily seized from a crowd of fleeing pilgrims on July 14th, he was taken to the place of execution on the Würzburg Schottenanger on the left bank of the Main.

One of the farmers was found guilty of stirring up a riot in the pilgrims' camp and wielding a sword, the other, a hermit , is said to have invented and spread miracle tales about the "Holy Young Man". In order to show the “Pauker von Niklashausen” the extent of his guilt, judges forced the two farmers to kneel in front of him and he had to watch them behead. The stunned young man was then led to the stake. While the flames were blazing up, he is said to have sung Marian songs in a bright boy’s voice until pain, fire and smoke broke his voice and suffocated it. In order to wipe the heretic completely from the earth, the ashes were scattered into the Main under strict supervision.

- Schottenanger memorial for Hans Böhm

Würzburg, Schottenanger, memorial from 2001 for Hans Böhm at the place of his execution, designed by Heinrich Schreiber (* 1935, Kronach), donated by Klaus Zeitler (former mayor of the city of Würzburg ) as a rising flame with a surrounding bronze relief

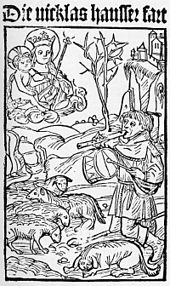

How the drummer became the little piper

Immediately after Böhm's execution, the Würzburg prince-bishop launched veritable disinformation campaigns. Their aim was to permanently discredit the reputation of the sincere preacher, “young holy man” and “prophet” as he was known among the people. For this purpose, a ballad similar to morality (title: Die nicklas hausser fart. ) Was commissioned and brought to the people in August 1476. Since the Nuremberg city council had inquired about the whereabouts of the arrested monk in Würzburg, a verse was also included in the ballad that portrayed the monk as an enigmatic devil creature that disappeared without a trace after its discovery. The Archbishop of Mainz and the Count of Wertheim shared the treasure heaped up in Niklashausen, which was so valuable that it was used to finance a bridge structure and construction work in the Mainz episcopal residence.

The Niklashaus pilgrimage turned out to be a bigger problem. After Böhm's execution, the pilgrims' camp had disbanded, but despite all the prohibitions, many people still made pilgrimages to the miraculous image of Mary. Niklashausen did not belong to the Würzburg territory, so Rudolf von Scherenberg did not know how to proceed against it. To his shame, the little church in Niklashaus threatened to become a memorial for martyrs .

A Franconian martyr - the symbolic power of the shepherd - transfiguring legends of those who had heard the "Holy Youth" preach - martyred and judged by the Würzburg prince-bishop: "What a terrible nightmare ."

In order to erase authentic memories of Hans Böhm as quickly as possible, the spreading of his message and the singing of his songs were persecuted and severely punished with the support of the southern German sovereigns and city councils. At the urging of Würzburg, the Archbishop of Mainz finally took the last option in the summer of 1477 and had the little church of Niklashäus torn down. Valuable inventory and other offerings were brought to Mainz and given to the cathedral building works of the Mainz Cathedral . Pilgrims who wanted to make a pilgrimage to Niklashausen were threatened with the most terrible punishments if they were apprehended in Mainz.

As if that weren't enough, in the Würzburg bishopric the former cattle herdsman, who occasionally hit the drum, was portrayed as a light-hearted musician, bagpipe player and fool . On a Würzburg print from 1490 his figure is depicted not only with a timpani but also with a flute.

The power of published opinion gradually took hold. In 1494 Sebastian Brant published the ship of fools , in which Hans Böhm (Behem) also found his fool's place, as the "bagpiper of Niklashausen". The danger of a resurrection of the cattle herder and heretical “fool” Bohm as a martyr was averted.

Böhm was not a scholar and politician like his contemporary Girolamo Savonarola , with whom he is often compared because of his mass impact, but who, unlike him, achieved martyr status. Böhm was also not one of the penitential preachers who were frequently encountered at the time . While they were imposing penances on people so that they might share in the bliss of heaven after their death, Boehm announced a new kingdom of God on earth to the people. Böhm's revolutionary social visions, which were only partially transmitted in written denunciations , quickly went under. 50 years after his execution, no peasant leader referred to an article in the Peasants' War that had anything to do with the “fool” Böhm. The buried memories of Hans Böhm, who had mutated from “cattle herders” and “drummers” to “pig drivers” and “piper hans”, were only unearthed again in the 19th century. The many unanswered questions and riddles about the "Pauker von Niklashausen", which repeatedly challenge new speculations due to the success of the disinformation policy pursued by Rudolf von Scherenberg, have turned him into a worthwhile projection figure, an object of history, literature that stimulates the imagination and cinematography.

Historical context

Hans Böhm's appearance came at a time when reforms in the spiritual and secular areas were overdue. Emperor Friedrich III. was not in the position to assert itself against the princes and push through far-reaching reforms. In the previous decades was in the Hochstift Würzburg with Johann II. Von Brunn , Sigismund von Sachsen and Johann III. von Grumbach, the credibility of the Würzburg bishops has reached a low point. The mixture of worldly power and - sometimes neglected - spiritual tasks resulted in hardship and skepticism, including hostility among the population. Even before Hans Böhm, there were prophetic social utopian remarks about the perceived grievances by traveling preachers, who were often tortured and died at the stake . Sects and larger religious movements, such as the devout followers of Jan Hus , were active and were opposed by the state church.

Was Hans Böhm the harbinger of later developments?

Hans Böhm is often seen as a harbinger of the Bundschuh movement and the peasant war . However, there is no evidence that the insurgents of the Peasant War made any reference to him or his movement.

Friedrich Engels saw Böhm's asceticism as typical of all later uprisings in the Middle Ages and modern times . As a result of the ascetic moral rigor, on the one hand, a principle of Spartan equality is established against the ruling class. On the other hand, it is necessary for the lowest social class to renounce the few pleasures that made their existence bearable at the moment in order to concentrate as a class , to assure themselves and to develop revolutionary energies. Engels distinguishes this plebeian-proletarian from the bourgeois asceticism of Lutheran morality and English Puritanism , the whole secret of which is frugality. At that time, Engels assumed that Hans Böhm had been in secret communication with the pastor of Niklashausen and the knights Kunz von Thunfeld and his son. They had prepared a military uprising, and on July 14, 1476 Boehm actually called the peasants to arms.

While Engels and a number of Marxist-Leninist social theorists who were oriented towards him heard the epoch of the early bourgeois revolution ringing in with the events of 1476, the movement of Hans Böhm, according to Klaus Arnold, lacks the underlying class struggle . The farmers, citizens and the lower aristocrats involved are difficult to understand as a homogeneous class because of their different positions.

Evaluation of the sources

There are numerous historical attempts to explain and reconstruct the events in Niklashausen and only a few contemporary reports, some of which have only been discovered and evaluated in the recent past. These reports, which largely ignore and deny the goals of this movement and the need for social change , were written exclusively by princely and clerical officials with fundamentally hostile reservations towards Hans Böhm. The pilgrims are portrayed as irrationally acting, seduced people who want to destroy the reasonable political and religious order. The propaganda campaign of the Würzburg prince-bishop, which began shortly after Böhm's execution, deliberately spread a distorted view of the events and tried to make him ridiculous. On the other hand, legends about historical facts probably began very early. Essential text and image sources of the immediate following time were the Schedelsche Weltchronik or the historical works of Lorenz Fries , on which many follow-up authors orientated themselves.

literature

Specialist literature

- Willy Andreas : Germany before the Reformation. A turning point . Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1972, ISBN 3-428-02670-5 (repr. Of the Stuttgart 1932 edition)

- Klaus Arnold : Niklashausen 1476. Sources and studies on the socio-religious movement of Hans Beheim and on the agricultural structure of a late medieval village . Koerner Verlag, Baden-Baden 1980, ISBN 3-87320-403-7

- Karl August Barack : Hans Böhm and the pilgrimage to Nicklashausen in 1476. A prelude to the great peasant war, edited from documents and chronicles . Theiss publishing house, Würzburg 1858

- Friedrich Engels : The German Peasants' War . Unrast-Verlag, Münster 2004, ISBN 3-89771-907-X

- Günther Franz : The German Peasants' War . Deutsche Buchgemeinschaft, Darmstadt 1975, ISBN 3-534-00202-4

- Alfred Meusel : Thomas Müntzer and his time. With a selection of the documents from the great German Peasant War . Aufbau-Verlag, Berlin 1952

- Will-Erich Peuckert : The big turning point . Scientific Book Society, Darmstadt 1976, ISBN 3-534-02765-5 (Repr. Of the Hamburg 1948 edition)

- The apocalyptic Saeculum and Luther , 295 pp.

- Intellectual history and folklore , pp. 299–748

- Elmar Weiss: The piper from Niklashausen . Franconian News, Tauberbischofsheim 2001, ISBN 3-924780-43-9

- Richard Wunderli: Peasant Fires. The Drummer of Niklashausen . Indiana University Press, Bloomington 1992, ISBN 0-253-36725-5

Biographies

- August Schäffler: Böhm, Hans . In: Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB). Volume 3, Duncker & Humblot, Leipzig 1876, pp. 62-65.

- Otto Graf zu Stolberg-Wernigerode: Böhm (Beheme), Hans (Pauker von Niklashausen, Pfeiferhänsle). In: New German Biography (NDB). Volume 2, Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 1955, ISBN 3-428-00183-4 , p. 382 ( digitized version ).

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bautz : Böhm, Hans, the "Pauker von Niklashausen". In: Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL). Volume 1, Bautz, Hamm 1975. 2nd, unchanged edition Hamm 1990, ISBN 3-88309-013-1 , Sp. 660-661.

- Hermann Haupt: Böhm, Hans . In: Realencyklopadie for Protestant Theology and Church (RE). 3. Edition. Volume 3, Hinrichs, Leipzig 1897, pp. 271-272.

Fiction

- Gunter Haug : Rebel in God's name - The short summer of the Pfeiferhans von Niklashausen . DRW-Verlag, Leinfelden-Echterdingen 2004, ISBN 3-87181-529-2

- Will Vesper : The Piper from Niclashausen. Historical narrative . Bertelsmann, Gütersloh 1924

- Leo Weismantel : Rebels in the name of God (formerly "Die Bauernnot"). German book club, Berlin 1926

- Alex Wedding : The flag of the piper hanger . New Life Publishing House, Berlin 1948

- Christa Wolf : Till Eulenspiegel . Luchterhand, Neuwied 1982, ISBN 3-472-61430-7 (together with Gerhard Wolf )

- Roman Rausch : The False Prophet . Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-499-27086-4

filming

Rainer Werner Fassbinder made the film Niklashauser Fart in 1970 , which tells the story of Hans Böhm in a mixture of historicizing and modernly adapted form. In the Niklashauser Fart, the sermons of Hans Böhm and the conversations of his companions reflect the forms of agitation and discussions in Marxist and anarchist groups in 1970, which in the Federal Republic of Germany were considering suitable paths to revolution .

Web links

- Literature by and about Hans Böhm in the catalog of the German National Library

- Stefan Primbs: Niklashauser Fahrt, 1476 . In: Historical Lexicon of Bavaria

- The Pauker von Niklashausen in the Würzburg Bishop's Chronicle

Individual evidence

- ^ A b Friedrich Engels: The German Peasants' War (1870), MEW Vol. 7, pp. 359–362

- ↑ see also Thüngfeld (noble family)

- ↑ See also list of Frankish knight families

- ↑ StA Würzburg: Liber diversarum formarum 16, fol. 344 (p. 718 ff.) - Copy from the 16th century. with the headline: Urphede Kuntzen von Thünstelts and Michels his son in 1476 .

- ^ Klaus Arnold: Niklashausen. Sources and studies on the socio-religious movement of Hans Beheim and on the agricultural structure of a late medieval village ; Koerner Publishing House, Baden-Baden 1980; ISBN 3-87320-403-7 ; P. 37 ff.

- ^ Klaus Arnold: Niklashausen. Sources and studies on the socio-religious movement of Hans Beheim and on the agricultural structure of a late medieval village. Koerner Verlag, Baden-Baden 1980, ISBN 3-87320-403-7 , pp. 31-36.

- ^ Klaus Arnold: Niklashausen. Sources and studies on the socio-religious movement of Hans Beheim and on the agricultural structure of a late medieval village ; Koerner Publishing House, Baden-Baden 1980; ISBN 3-87320-403-7 ; P. 20.

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Bohm, Hans |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Preacher, "Pauker von Niklashausen" |

| DATE OF BIRTH | around 1458 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Helmstadt |

| DATE OF DEATH | July 19, 1476 |

| Place of death | Wurzburg |