Ruler's cult

The ruler's cult is understood to mean the divine veneration of a ruler during his lifetime. The phenomenon manifested itself during the Hellenistic period. It has its roots in Greek traditions and the interaction between Greek cities and rulers. A distinction is made between the ruler's cult, which was established by Greek cities, associations and private individuals, and the cult that emanated from the royal administration. It can be shown that with the increasing institutionalization of the ruler's cult, the religious acts of the cities for the kings decreased. In contrast, the consecrations made by the royal administration increased. The development is interpreted to mean that the religious significance of the ruler's cult for the cities decreased in the course of Hellenism.

After the Alexander Campaign and the death of Alexander the Great , new kingdoms developed under the Diadochi . To a large extent, they originated in areas that already had a monarchical tradition. The kingship was closely tied to the power and successes of the king. In contrast, the Greek cities struggled with royal rule. The mutual dependence was based on real power relations and the efforts of the rulers for legitimation . The ruler cult arose from this tension. It was also used by the Romans from the beginning . His ideological concept was so successful that parts of him were continued in the Roman imperial cult .

The cities

The cult for a living person was applied for in a city and then decided. A deed of foundation ( Psephisma ) contained the reason for the introduction and the actions to be carried out in the cult. In the case of a number of cults, the motives of which have not been handed down, the reason can be discovered, such as the founders ( Ktistes ) of cities that have always had a cult. The reasons for the introduction is also reflected in the nicknames chosen for the rulers, which can be seen as the short form of a motif.

The introduction of urban cults can all be traced back to the background of an outstanding achievement or benefit ( euergetes , see euergetism ) of a person. This could include financial support in an emergency, rescue from external enemies, the return of freedom or the establishment of To be the “foundation” of a city. The creation, maintenance or restoration of the urban existence by external rulers was in the consciousness of the city, which could not survive on its own. The cult represented thanksgiving and the payment of a debt of thanks. So it was not about the personality or position of a king, but solely about his merit.

A cult could be lifted at any time if the worship was no longer of any use to the city. Whether the venerated person had died or not did not play a decisive role. At times the abolition took on drastic features, as in the example of Philip V , in the case of Athens in 201 BC. BC canceled all actions for him and his ancestors and erased all honors on inscriptions. In the annual prayers for the king's well-being, Philip V, his descendants and all Macedonians should be cursed.

A city's cult had a distinctly local character. On the one hand, the cities did not have political influence outside their domain and, on the other hand, it would have contradicted the sense of thanking a local charity.

An important aspect of the early cult of rulers is the fact that the cities did not create gods in their perception, but rather gave divine honors to outstanding people who were capable of great deeds and thus resembled the gods. They recognized them as gods at once, but they did not create them. So up to 240 BC In no inscriptions that a city made a ruler a god and thus there was no apotheosis of a living person. A city first made Augustus a god in the decree of Mytilene . With this the declaration of a person to a god was abandoned in favor of a constitutive character and the term apotheosis found its way into the Greek language in the following period.

The monarchies

Even before the emergence of the Hellenistic kingdoms, the monarchies of Macedonia , Egypt, and Asia were linked to religion in many ways. In Macedonia the kings assumed priestly functions, in Egypt the pharaoh was the mediator between gods and humans and in the Persian Empire the king had a special relationship with the creator god Ahura Mazda .

From the beginning, the Hellenistic kings strove to maintain good relationships with the local and Greek gods. They placed themselves under the protection of a deity and asserted a divine descent. The Antigonids appealed to Philip II and Alexander the Great and derived their vote from Heracles . The Seleucids had their ancestor and protector Apollon of Miletus and the Ptolemaic kings of Egypt adapted to several Greek gods, the most important of which was Dionysus .

Homer already describes the dwelling of a mortal with a deity. The real meaning of Synnaos Theos unfolded during the Hellenistic period. The sharing of a temple between rulers and gods established a connection between gods and deified people in common rituals and was an important link in the chain that led to the ruler's cult.

Greek idea of the divine

A big difference between the Greek idea of the divine and, for example, the Christian faith is the “fragility of the boundary between God and man”. In the Greek tradition, outstanding personalities were repeatedly referred to as "gods among men". For example, research into Herodotus' treatment of heroes reveals that this early historian made little or no distinction between heroes and gods on religious subjects. Heroes are even referred to as gods when it comes to their religious role or offerings made. The frequent reference to man's hubris in Greek legends and myths also indicates a graduated understanding of the divine.

At the center of the Greek conception of the divine was the willingness of the gods and goddesses to listen to and support those who worshiped them. People who had performed extraordinary things in their lifetime, such as victories in combat or in a competition, could become a protective force after their death. Examples of this were Asklepios , Heracles or Dionysus , who were elevated to gods after their death. The Hellenistic royal cult followed this idea. The kings had the task of protecting and promoting those who worshiped them during their lifetime and beyond their death.

In the Greek beliefs, the real visibility of divine power was an essential element. This comes in a hymn of Athens for Demetrios Poliorketes Soter expressed. The hymnos is narrated from Duris of Samos and Demochares .

“Other gods are either far away or have no ears or do not exist or pay no attention to us, not even once. But we see you presently present, not made of wood, not even of stone, but real. "

The rulers' claim to divine worship had to be earned through success, protection and charity. The numerous epithets of the Hellenistic kings such as savior ( soter ), manifested power ( epiphanes ) or victorious ( kallinikos ) indicated the peculiarity of their merits. The god-like merits enabled the kings to receive similar honors as the gods. But they were not identical to the gods because their mortality made the difference. With their achievements, however, they were able to overcome this inadequacy.

The duties of the rulers are also listed in the aforementioned Athenian hymn:

“So we pray to you: First, create peace, dearest, you are the Lord; but the Sphinx, ruling not only over Thebes, but all of Greece (an aitoler, who, sitting on the rock like the ancient one, steals and carries away all our bodies, and I cannot fight [...]): best chastise herself; otherwise find an oidipus that can either topple this sphinx off the rock or turn it to dust. "

Interaction between rulers and ruled

It is a widespread belief that a king used the ruler's cult to give his rule the necessary legitimation. This idea confuses the result with the original intention and cannot be substantiated by tradition. Demochares even writes that Demetrios I. Poliorketes Soter was annoyed about the behavior of the Athenians , since many aspects of the cult were accompanied by theatrical behavior.

With the exception of the special case of Alexander the Great, in the early Hellenistic period it was always the cities that initiated a cult. They developed a close relationship with the king through the cult with the intention of expressing gratitude for past deeds and expectations for future benefits. To make the rulers benevolent, they accepted their role as subordinates and showed themselves weak and needy. In contrast, they constructed the image of the godlike king. The rulers, on the other hand, promised to take the interests of the cities into account. As a religious phenomenon , the ruler's cult corresponds to the mentality of the do ut des , “I give as you give”, which corresponds to the fundamental element of the Greek idea of the gods.

There was not just an official cult of the cities as an institution. Individuals were also asked, partly by decree , to pay homage to kings and offer sacrifices. A fountain dedicated to Laodike was used for sacrifices, purifications and wedding rituals. There are dedications from soldiers and officers who expressed their loyalty and solidarity in this way with the hope of promotion and protection.

The garrisons were an important instrument of the kings . The commander and his soldiers became the bearers of the dynastic ideology. They were present and made the king present with their dedications and veneration. Examples of this are traditions from Crete , Cyprus and Ephesus . The priests played a similar role. In the cities under the king's direct or indirect control, they made sure that the king was worshiped.

Ritualized acts

From the beginning, the ruler's cult was carried out on the model of worshiping the gods. The central element was the holiday that bore the name of the venerable. Sacrifices were made that were an essential part of a cult. Other acts were processions and the holding of competitions. The holiday for living rulers always took place on their birthdays, provided that the cult was founded during their lifetime. Cults founded during Alexander the Great's lifetime continued to be celebrated on his birthday after his death. The cult in Alexandria, on the other hand, which was only introduced after his death, took place on the day of his death.

The holiday usually started with a procession . If the holiday was organized by cities, the residents took part in the procession. When it was carried out by the royal administration, the population was a spectator. Competitions very often survived the kings as in the example of Pergamon , in which the games even outlasted the dynasty into the 2nd century AD.

There were altars and shrines built, which were attended by priests. The buildings stood in districts that bore the name of the king or queen. In the case of statues, it is difficult to prove whether they were part of a ruler's cult or simply served to honor a deserving person. They usually stood in a temple dedicated to a deity.

The term eponym is often used by scientists in descriptions of cults in the context of the ruler's cult. Phylums , holy districts, holidays and month names could bear the derived name of the ruler and were an important means of expression of a cult for a particular king. But the term eponymous priesthood is also used, which is not about the name of the ruler. The term is explained in more detail in the chapter on priests and priestesses (see below).

The actions of the cities in honor of the rulers were repeated innumerable times in Hellenistic space and inscriptions confirm that they were increasingly taking on a " stereotypical " character.

Victim

An important indication of cultic veneration was the performance of a sacrificial ritual. The use of sheep and cattle for sacrifices has been handed down. But burn offerings and libations were also offered. Incense offerings are proven in the cult of the Attalids . The sacrifices were carried out by priests, in the case of the Ionian League by delegates from all federal cities or in Pergamon by a college of strategists.

Temple, altars and cult image

A hieron ( sanctuary ) was usually named after the person worshiped. The name encompassed not only the Naos ( cult building ), but the entire Temenos ( sacred area ). Examples are Amyntion , Alexandreion , Ptolemaion , Eumenion and many others. The location and design of the sanctuaries are seldom known. In Rhodes the Temenos of Ptolemy I was in the middle of the city. The Byzantians built the temple for Ptolemy II on a headland in front of the city and in Teos the Alexandreion was in a grove.

Each place of worship contained an altar that stood in front of the temple. Altars were much more common than temples because they were more expensive to build. If there was a temple and an altar, there was also a cult image. A distinction is made between an agalma (" cult image ") and an eikon ("honor statue").

Priests and priestesses

In Greek society there was no priesthood and a cult did not necessarily have its own priest or priestess. The practice was different, however, and only the care and administration of a temple required the office of priest.

Eponymous priests or priestesses were elected for a year. Similar to the consulate years in the Roman Empire , the years bore the names of the elected as in Kassandreia and in Dura-Europos . An eponymous priesthood could therefore serve as a dating element. In Egypt, for example, official documents were dated with the year of reign of Ptolemy I and the name of the priest who held the eponymous priesthood of the cult of Alexander in Alexandria . In the same empire was 270 BC. An eponymous priestess appointed for Arsinoe II , who was listed in the official documents together with the priest of the cult of Alexander. In Erythrai , the Alexander priesthood, like all other priesthoods, was for sale. All known eponymous priestly offices of the cults of cities were offices for city founders.

Priestesses in city cults are not known. But they are not uncommon in dynastic cults. In the state cult of the Seleucids, priestesses for Laodike and Berenike have been handed down. Usually priests were appointed for the cult of a god and priestesses for a goddess.

Festivals, agons and processions

The panegyris ( event ) in honor of living persons was with Agonen ( competitions ) and acting positions connected. The festival bore the name of the honoree like the Alexandreia of the Ionian League , the Lysandreia in Samos , the Demetrieia in Athens and the Seleukeia in Erythrai . The main elements of the holiday were the sacrifice and the agone. As a rule, a pompe - a pageant - was part of it, in which the wreathed population actively participated. Participation in the Pompe was reserved for the citizens of a city. From Plataiai , for example, it is said that no slaves were allowed to take part in the procession for the fallen of the Battle of Plataiai , because the fallen had fought for freedom. After the procession was over, the sacrificial rite was performed.

The types of competitions included gymnastic and artistic agons . Horse and chariot races were also popular. The musical agons featured tragic, dramatic and lyrical performances.

Phyles and months

Numerous phyls were named after living people throughout the Hellenistic period . Tradition counts Alexander the Great, Antigonus I Monophthalmos, Demetrios I Poliorketes, Seleukos I , Antiochus I and Ptolemaios I as eponyms of Phylen. The examples extend further to the Pergamene rulers and to the Roman emperors. The naming of a phyle after a living person was an award given by the state and went hand in hand with the cultic veneration of the ruler throughout the city. The cultic veneration of a phyle for its namesake was carried out in parallel. For one of the city's founders, the phyle had the name from the beginning. In the other cases, the previous eponym was replaced or the number of phylums was increased.

The Greek months always bore the names of gods or festivals. It is believed that months that bore the names of living people give an indication of cultic veneration. Traditional names of the months are Demetrion in Athens, Seleukeios in Ilion , Antiocheon in Laodikeia on Lykos. In Ilion the court hearings were suspended during the month of Seleukeios and it is recorded from Philochorus that the month of Demetrion was considered a “holy” month in Athens.

Epithets

The Hellenistic period was a heyday of the epithets , which were assigned to the rulers in order to highlight their special merits. The most common epithets in the early Hellenistic period up to 240 BC. Were Theos , Soter and Euergetes . Since Euergetes had a profane meaning, its performance does not necessarily prove that a cult existed for this person. In contrast, Soter and Theos always indicate a cult.

In many cases, the epithets were not a permanent title, but an expression of a specific local cult. So a king could have a different title in different cities. It is therefore not possible to identify a king on the basis of his nickname and the fact that kings have the same name often makes it even more difficult to assign them to a specific person.

The urban surnames came about because of the merits of a king. Antiochus I was nicknamed Soter in Ilion because he had saved the city in danger of war. Ptolemy I was honored by Rhodes with the same nickname because he had protected her from Demetrios I Poliorketes. The nicknames therefore express the motivation why a city established a cult for a ruler. They say nothing about the personality or the characteristics of a ruler, but only describe his merits.

The official surnames, however, were used throughout the empire. They emerged independently of the urban surnames, although it happened that local names could develop into dynastic ones. With the Seleucids, for example, the dynastic surnames were only given after the death of the person concerned and were used throughout the empire.

development

predecessor

The Spartan Lysander was the first to be worshiped in a godlike manner during his lifetime. According to Duris, an altar for Lysander was erected on Samos , sacrifices were made, ritual songs were sung in his honor and the holiday for Hera was renamed after him.

The royal cult for Lysander and its classification as the predecessor of the ruler cult was controversial among scientists until the middle of the 19th century. Some classified it as a hero cult , in the opinion that the roots of the ruler cult can be derived from the Orient. Others saw it as a precedent because they saw the ruler cult as a personal creation of Alexander the great.

The worship of Dion of Syracuse is another cult in the run-up to the ruler's cult, but this assessment is not undisputed either. After Dion in 357 BC Chr. Syracuse from the tyranny had freed that Dionysius had made famous, he was hailed as liberators. When he saved the city a second time, he was nicknamed soter ( savior ) and euergetes ( benefactor ). The residents built a tropaion and made sacrifices to it.

Immediate predecessors of the ruler's cult were the cults for the two Macedonian kings, Amyntas III. and Philip II. In Pydna the shrine Amynteion is narrated. The indications for a cult for Philip II are contradicting for Amphipolis , Ephesus and Eresus . Equally controversial is a report that a picture of Philip II was carried along with the twelve Olympian gods in a procession shortly before his murder. The cult of the city of Philippi, on the other hand, may have already taken place during his lifetime.

Before the time of Alexander the Great, rulership cults were not widespread and occurred mainly in Macedonia . It was not until Alexander the Great that a precedent was set that had the power to spread throughout the entire Hellenistic region.

Alexander the Great

Alexander the Great is a special case with regard to the cult of rulers. His military successes overshadowed all previous ones. In the conquest of the fortress of Aornos on the Indus , which was considered impregnable, he was more successful than Heracles and his campaign to India was comparable to that of Dionysus . With his conquests he came into contact with the reverence of the Persian court to the king and the divine worship of the Egyptian pharaoh .

Already during Alexander's lifetime cults from several federal cities of the Ionian League are attested and a common festival. The Bund, a form of Koinon , played Alexander games with competitions ( agone ) and sacrifices. In Ephesus the cult for Alexander was established in 334 BC. After he liberated the city and freed it from its tributes. According to a story by Artemidor of Ephesus , which is reproduced by Strabo, the inhabitants of the city rebuilt the temple at Alexander's request. They asked him if he could contribute to the costs, and he replied, "It is not fitting for a god to offer gifts to the gods."

It does not break with Greek tradition that Alexander traced his ancestry back to heroes like Achilles and Heracles . Examples of this have come down to us from Athens and Kos . In addition, shortly before his death, Alexander declared himself the son of Zeus . There is also a prehistory to this, in that the Sibylle of Erythrai already existed in Winder 332/1 BC. BC announced that Alexander was the son of Zeus. In addition, there are Greek testimonies of other people from earlier times who were regarded as sons of Zeus, as the examples of Theogenes from Thasos or Euthymos show.

Alexander's call for divine glorification from the Greek cities and their response has spawned anecdotes that have been labeled "unreliable" or "very misleading". Misleading in the sense that they lead to the assumption that the Greek cities were reluctant to accept the ruler's cult and that it was imposed on them as something alien. The reactions of Sparta and Athens are nevertheless listed below because they illustrate the tension between Greek cities and Hellenistic kingdoms and give an indication of why the cult of rule is described by some scholars as a phenomenon.

The reaction of Sparta is recorded from Plutarch . The Spartans therefore decided: "If Alexander wants to be a god, let him be a god". In Athens Demosthenes is said to have made the remark: "Let him be the son of Zeus, and also of Poseidon, if he wants."

The extent, spread, and persistence of the glorification of Alexander the Great was not matched by any Hellenistic ruler before or after him. In the second half of the 2nd century BC In the same century private persons reserved his shrine Alexandreion in Priene and a city reserved an amount in their “budget” to make sacrifices for him. There are still many examples from other cities that show that his veneration extended far beyond his death.

Local variants

Antigonids

As early as 311 BC The city of Skepticism in Asia Minor set up a cult for Antigonus I. Monophthalmos . They thanked the king for the peace with Cassander , Lysimachus and Ptolemy I and the freedom he allowed the cities to enjoy.

The festival introduced by the Nesiotenbund on Delos in honor of Antigonus I Monophthalmos and Demetrios Poliorketes is likely to be after the victory at Salamis in 306 BC. Have been introduced. It is until 294 BC. And was probably passed down during the supremacy of Demetrios Poliorketes in the Aegean region until 287 BC. Held.

The city of Athens was so grateful to Antigonos I Monophthalmos and Demetrios Poliorketes after the liberation of Cassander that they founded a priesthood by decree , built an altar, organized a holiday with a procession and competitions in honor of their “benefactors” and liberators. Two phyls, Antigonis and Demetrias , were named after their names.

For Queen Phila I , a resolution from Samos has come down to us that mentions a Temenos to be consecrated to the Queen "as soon as the honors decided for the Queen have been carried out". It is controversial whether the inscription is coined on Phila I or on Phila II , the daughter of Seleucus I and wife of Antigonus II Gonatas . In contrast, the cult in Thia , in which Phila I is listed together with Antigonus I Monophthalmos and Demetrios Poliorketes, is undisputed .

The Antigonids ruled over an area where Greek traditions were very strong. The early ruler cult for Antigonus I. Monophthalmos and Demetrios Poliorketes corresponds to the definition of the cult initiated by the cities. It was widespread but limited to the cities. It has long been assumed that Antigonus II Gonatas rejected the cult in the cities he controlled. But more recent findings indicate that he had received god-like worship from Athens .

Ptolemies

The Ptolemies are an example of the introduction of the ruler's cult by the royal administration. With the help of the ruler's cult, they managed to integrate ancient Egyptian traditions into their system of rule. This can be seen, for example, in the redirection of proceeds to cult for Arsinoe II or the adoption of traditional holidays for celebrations of the Ptolemies.

The Ptolemaic queens played a prominent role in the ruler's cult and their high position was demonstrated by the fact that almost all of them received a cult during their lifetime. The most popular goddesses with whom the queens were identified were Aphrodite and Isis .

Arsinoe II was one of the most popular deities in Egypt and Cyprus and her image was processed with Isis and Aphrodite after her death . In Cyprus alone, twenty house altars from different cities have survived and their cult outlived their death by a century. Two of the earliest evidence of their cult come from the Ptolemaic general Kallikrates and a Chairemon , who call Arsione II the patron goddess of sailors. Ptolemy II Philadelphus raised his deceased wife to the temple-dividing goddess in all Egyptian temples. It is also believed that she received the same honor in Greek sanctuaries. 270 BC A Greek priestess office of her own was established for her and she received an altar, her own sacred precinct, a festival, and a temple. Her cult was so important that she received her own altar in the same place next to the temple for the sibling gods.

Outside of Egypt, the Ptolemies received honors in the form of an urban ruler cult. Rhodes judged Ptolemy I Soter in 304 BC. A cult because he had rushed to help them during the siege by Demetrios I Poliorketes. For Ptolemy III. Euergetes and the queen is occupied by a priest on the same island. Other cults are attested by the Nesiotenbund, Miletus and Ephesus. A cult for Ptolemy III was established in Athens. Euergetes and Berenike II. 224/223 BC BC, which included the naming of a phyle, the erection of a statue on the agora and a festival. After the reign of the fourth Ptolemaic king, the urban consecrations disappeared parallel with the loss of Ptolemaic hegemony over the eastern Mediterranean.

In Egypt, Ptolemy I Soter and Berenike I were worshiped as gods by Greek private individuals during their lifetime. The actual ruler cult, however, began under Ptolemy II Philadelphus. He decreed for himself and his sister wife Arsinoe II. 272/271 BC. Its own cult. A holy precinct was established in the palace district, there was a temple for the siblings in Philadelphia, and two altars have survived from Alexandria. It is the first, centrally established, empire-wide cult for the Ptolemies.

The cult for the person of the ruler and his family members soon developed into a new cult that applied to the entire ruling family, similar to the Seleucids. In contrast to that of Antiochus III. introduced dynasty cult, which was tied to the ancestor of the family, Seleukos I, in the Ptolemaic Empire, however, the cult for Alexander the great formed the basis of the Greek dynasty cult, see the main article Ptolemaic Alexander cult .

The Pharaoh played a central role in Egyptian society in maintaining world order. The economic security of the temples depended on his generosity. On the other hand, the priests, as keepers and narrators of the ancient religion, had a great influence on the acceptance of a king. In order to guarantee their survival, the priestly elite supported the foreign rule of the Ptolemies and received an increase in state grants to the sanctuaries as a reward. Due to their strategically important role, they also retained their rank as an elite among the indigenous population of Egypt.

From the beginning, the Ptolemies were represented as pharaohs and were worshiped as Egyptian deities. The initiators of the cult were the Egyptian priests, who had them depicted in their temples in the traditional patterns of the pharaohs. The priestly elite played the decisive role in the practice of the Egyptian ruler cult for the acceptance of foreign rule, in which they presented the Ptolemies at public festivals and processions as new gods according to Egyptian rites and patterns.

The inclusion of the Ptolemaic kings in the Egyptian royal cult, which was expressed in statues and the festival cult for the royal Ka , is difficult to prove. Since the divine Ka of the Pharaoh can be found in the temple texts and in reliefs in Ptolemaic times, it is assumed that the kings continued to receive an Egyptian royal cult. An important indication for the continued existence of an Egyptian king cult could be the adoption of the five-part pharaonic carrier title (see the list of pharaohs during the Hellenistic period ).

The cult of rulers and dynasties in Egypt was multi-layered and provided the population with a wide variety of forms of expression for a kind of ruler worship that was convenient for them. The rulers could be worshiped as Egyptian as well as Greek gods. But it was also enough to express loyalty to the rulers and to worship them like gods. The cult forms could be both Greek and Egyptian.

Seleucids

In the early Hellenistic period, the ruler's cult of the Seleucids did not differ significantly from the other cults established in the Hellenistic region.

A decree has been passed down from the city of Ilion that contains detailed information about the cult for Seleucus I. An altar was set up and an event with sacrifices and competitions was held. The cult was probably introduced out of gratitude for the liberation of Lysimachus, and it seems certain that it was introduced during the king's lifetime. For the same reason, the cults of the cities of Erythrai , Priene , Lemnos and probably Magnesia on the meander may have originated. In Magnesia am Mäander the Phyle Seleukis was named after him in honor of Seleukos I , from which the presence of a cult can be derived.

The cult for Antiochus I has also been handed down from Ilion . The erection of an equestrian statue of the king in the temple of Athena is not in itself a sign of the existence of a cult, but the inscription uses the epithets soter and euergetes , which refer to a cult. Antiochus I had probably saved the city from great danger and the city thanked him with the cult. An interesting detail about the story is that the king had his own temple and priest in the city, but the equestrian statue was placed in the temple of a deity.

The first Seleucid king to introduce his own cult and that of his wife Laodike was Antiochus III. the great. The dynastic cult of the Seleucids was dispersed and each satrapy had its own priest. Neither the Ptolemies nor the Seleucids stated in official documents before the 2nd century BC. The cult title used.

Attalids

The worship of the rulers in the Pergamene Empire was similar to the cults in the cities. The Attalid family was worshiped during their lifetime and, according to current research, were only worshiped as gods after their death.

Cultic honors during his lifetime and after his death have been handed down for Philetairos . In Pergamon, the first cultic honors for a member of the Attalid ruling family for Eumenes I , in which he is nicknamed Euergetes , have been handed down . The city celebrated a festival called Eumeneia in his honor , on which a sheep sacrifice was offered. For two other members, Stratonike and her son Attalus III. , it is said that they had priests in Pergamon. A "Stephanephoros of the twelve gods and the deified Eumenes II" is listed in the same inscription. Some researchers suspect that this Stephanephoros can be assigned to the sacred area called Eumeneion and that this is to be equated with the Pergamon Altar .

From Nikandros von Kolophon it is handed down that the Attalids claimed Heracles as ancestor, whose cult the dynasty consciously promoted. They used the myth of Telephos , who was a son of Heracles. The inner frieze of the Pergamon Altar tells its story. The myth established not only a connection between the dynasty and a god, but also one between the city of Pergamum and the dynasty, since the population was considered Telephid. Legend has it that the foreign ruling family was linked to the origin of the population.

Dionysus was the god of enjoyment, joy and the arts. Two of the three letters from Attalids that are handed down on an inscription stele deal with the cult of Dionysus Kathegemon ( the leader ). In it Attalus II mentions a great festival in honor of the god, at which he and the priest make a sacrifice. The letter shows that the priesthood was for life and that the priest, who came from the ruling family, was appointed by the king. Dionysus was the patron god of the Dionysian technites , who had come together in associations across the entire Hellenistic region. One of the associations was the union of the Technites in the city of Teos . The city did not belong to the Pergamene Empire until the Peace of Apamea . The branch of the Technites in Pergamon, which had been founded by Attalus I or Eumenes II, was then merged with that of Teos. The Dionysian technites played an important role in the self-portrayal of the royal houses and in particular for the royal house of Pergamon. The importance of this is shown by the fact that the Technites from Teos were the first to be allowed to mint coins. The association of attalists , which was founded by technites, was responsible for cultivating the ruler cult. Based on these references, the research is the worship of the cult of Dionysius Kathegemon as a family reference. Dynasty cult of the Attalids.

The ruler cult of the Attalids is classified as a dynastic cult. For a long time it was classified by scholars as fundamentally different from that of the Seleucids and Ptolemies, since it was practiced with caution.

Commagene

For a long time, Kommagene belonged to various empires and was founded in the 2nd century BC. Under Ptolemy of Kommagene , who was of Armenian-Iranian origin, independent. In the late Hellenistic period, Mithradates I Kallinikos reformed the ruler cult in Commagene. His son Antiochus I. Theos Dikaios Epiphanes Philorhomaios Philhellen integrated the Anatolian and Persian cultures that dominated the kingdom and led the ruler's cult to a unique form. The cult was introduced in the Greek cities of the empire, in keeping with Greek tradition and the interaction between the cities and the Hellenistic king.

The epithets of Antiochus I provide a first indication of Greek and non-Greek elements in the commagenic ruler's cult. Theos and Epiphanes are used by Greek rulers , Dikaios and Philhellen, on the other hand, only by non-Greek rulers.

Antiochus I left a hierothesion in Arsameia on Nymphaios , a burial place for the Commagenic dynasty, which his father, Mithridates I Kallinikos, had already built and which his son expanded. Inscriptions from the same city confirm the importance of ancestor worship in the ruler's cult of Kommagene. The deceased are referred to as "fatherly daimones " who have been taken in by the gods. At the same time, the inscriptions also list the honor ( τιμή ) of the king, legitimized by the gods , which is achieved through the worship of the ancestors and everything divine. With this the king acts as a mediator between the divine and the human. With the deified ancestors and the legitimation of the king by the gods, the cult in Kommagene differs significantly from the urban ruler's cult.

The statues and images of gods are described on inscriptions on the base III . The text differentiates between the Agalma ("cult image") for the gods and the Eikon ("honor statue") for the king. The distinction confirms the king's closeness to the gods and at the same time confirms that the king is not a god.

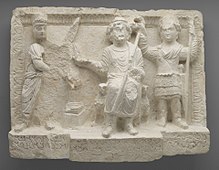

The depiction of dexiosis , the handshake with a god, translates these thoughts on the inscriptions into a picture. The gods are shown on the right side, which is considered more respected. The king and the god are not on the same level, but it is a representation of a "contract of unequal".

An inscription from Nemrut Dağı lists the gods of the dynastic pantheon, which follows the two traditions of kingship and contains Greco-Persian double names, such as Zeus - Oromasdes , Apollon - Mithras , Helios - Hermes and Artagnes - Herakles . According to the trifunctional system of Georges Dumézil, the gods were divided into religious-legal, martial and nourishing responsibilities and competencies. The symbol of the nourishing fatherland was based on the Persian Daēnā , a spiritual element in its collective nourishing function. In the same inscription a deity of fate and time is mentioned together with Chronos Apeiros ( infinite time ), which corresponds to the Persian Zurvān ī Akanārak , see Zurvanism . The double names are now considered to be Persian deities in Greek garb rather than the other way around.

Precise instructions for carrying out the cult are given in inscriptions. Wreaths, incense burnings, sacrifices and the participation of musicians are mandatory. What is striking is the lack of Persian customs such as the fire altar, the magician and the use of sacred sap. The priests spoke Greek and wore Persian clothes.

Antiochus I was convinced that after his death his body would lie in the grave and his soul would be sent to Zeus-Oromasdes. This idea corresponds to a Persian concept that has been handed down from Avestan texts and the Pahlavi literature.

Sources

The sources for the urban ruler cult are very sketchy. Christian Habicht , who in his investigation the cults of the Greek cities for living people until the middle of the 3rd BC. Chr., Differentiates between epigraphic and literary sources and sees an expression of the incompleteness in the few cults that appear in both types of sources. He also lists examples in which what has been handed down can only be a part, such as the psephism of a city that belonged to a covenant that had introduced the cult, or a decree that must be based on an earlier one but has been lost.

Most of the literary sources for the urban cults originally come from local historians, whose accounts have survived in the works of known Greek and Roman historians. Examples of local historians were Gorgon for Rhodes , Demochares and Philochoros for Athens, Duris of Samos and many others. The reasons for the introduction of a ruler cult and descriptions of it only found their way into the respective works in the context of larger events and are therefore very sketchy. With the loss of the reports of the local reporters came the loss of the main literary sources for the urban ruler cult.

Great hopes for the improvement of the sources are placed on new finds of inscriptions. For example, cults for Antigonus II could only be proven in this way in the last few decades. It is also hoped to find other original decrees from cities in which the motivation for the establishment of a cult and the actions carried out are described in great detail. In order to get a complete picture of a cult, one needs information about the motive, form, time of origin and the duration, and all this together is quite rare.

reception

Until the middle of the 20th century, scientists placed the honored people at the center of their research in order to understand the ruler's cult. They were based on the dynastic ruler's cult, which was created by the king and was mandatory throughout the empire. No distinction was made between urban and dynastic cults.

The explanations for the ruler cult led from the overwhelming impression of the personalities of Alexander the Great and the Diadochi to the virtues and virtues of a person to the great power of a revered king. It has also often been claimed that the epiphany had the greatest influence on the establishment of an urban cult. Others, on the other hand, classified the ruler's cult as a moral decline, which led to unworthy flattery and subservience of the cities.

The established opinion was that the ruler's cult was an expression of a relationship between rulers and individuals. With his work "Alexander the Great and the Establishment of the Absolute Monarchy" in 1910, Eduard Meyer created the scientific foundations for the thesis that the ruler cult was a conscious creation of Alexander the Great. He saw in the divinity of kings the only means of reconciling the independence of the Greek city community with absolute monarchical power.

In the course of the 20th century, this thesis came under increasing pressure and scientists such as Ulrich Wilcken , Alfred Heuss and Elias Bickermann set the first standards to refute it. In 1956 Christian Habicht presented the foundation deeds of the cities from the beginnings to 240 BC. At the center of an investigation. It fundamentally changed the view of the ruler cult. The meaning and the special characteristics of a personality, which up until now had been the starting point for any analysis of the ruler's cult, was replaced in the early Hellenistic period with the specific achievements that a personality had performed for a local city. The urban cult is therefore "primarily a general historical and only secondarily a religious-historical phenomenon". But it was only possible through "a change in the general religious consciousness".

Stefan Pfeiffer summarized the research in 2008 for the complex ruler's cult of the Ptolemies. Based on Egyptian and Greek sources, he classifies the cult forms into a Greek and Egyptian ruler and dynasty cult and the Egyptian king cult. He notes that there has been an overlap and interweaving of the five different cult forms, not least because of the Greek, Egyptian and Greco-Egyptian associations that played a central role in the veneration of the royal dynasty.

In 2011, Peter Franz Mittag describes the cult of rulers and dynasties in Kommagene, noting that the ancestors' deification has increased over time. Likewise, the worship of the king was moved closer and closer to serving the gods. The king became a god “at no time”. The investigation found that the ruler's cult in the Kommagene was carried out according to traditional Greek patterns, but the religious core was "Iranian-Persian".

literature

- Sophia Aneziri, Dimitris Damskos: Urban Cults in the Hellenistic Gymnasion. In: Daniel Kah, Peter Scholz : The Hellenistic Gymnasium (= knowledge culture and social change. Volume 8). Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2004, ISBN 3-05-004370-9 , pp. 247-272 (online)

- Angelos Chaniotis : The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers. In: Andrew Erskine (Ed.): A companion to the Hellenistic world. Blackwell, Oxford 2003, pp. 431-445. (PDF)

- Domagoj A. Gladić: The Memphis Decree (196 BC) . Dissertation, Trier 2015. (PDF)

- Linda-Marie Günther , Sonja Plischke: Studies on the pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic cult of rulers (= Oikumene. Studies on ancient world history. Volume 9). Verlag Antike, Berlin 2011, ISBN 978-3-938032-47-3 .

- Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities. 2nd Edition. CH Beck, Munich 1970, ISBN 3-406-03254-0 .

- Haritini Kotsidu : Timē kai doxa. Honors for Hellenistic rulers in the Greek motherland and in Asia Minor with special consideration of the archaeological monuments. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2000, ISBN 3-05-003447-5 .

- Stefan Pfeiffer : rulers and dynasty cults in the Ptolemaic empire. Systematics and classification of cult forms (= Munich contributions to papyrus research and ancient legal history. Volume 98). CH Beck, Munich 2008 (online)

- Frank W. Walbank : Kings as gods. Reflections on the ruler cult from Alexander to Augustus. In: Chiron . Volume 17, 1987, pp. 365-382.

- Erich Winter : Cult of rulers in the Egyptian Ptolemaic temples. In: Herwig Maehler , Volker Michael Strocka (ed.): The Ptolemaic Egypt. Files from the International Symposium, September 27-29, 1976 in Berlin. Philipp von Zabern, Mainz am Rhein 1978, ISBN 3-8053-0362-9 , pp. 147–158.

Individual notes

- ^ A b Frank W. Walbank : Kings as gods. Reflections on the ruler cult from Alexander to Augustus. In: Chiron 17 (1987), p. 366.

- ^ Frank W. Walbank : Kings as gods. Reflections on the ruler cult from Alexander to Augustus. In: Chiron 17 (1987), p. 368.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities. Munich 1970, p. 160.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities. Munich 1970, p. 162.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities. Munich 1970, p. 161.

- ↑ Haritini Kotsidu: Timē kai doxa. Honors for Hellenistic rulers in the Greek motherland and in Asia Minor with special consideration of the archaeological monuments . Akademie-Verlag, Berlin 2000, p. 14.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities. Munich 1970, p. 171.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities. Munich 1970, pp. 163-164.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities. Munich 1970, pp. 185, 189.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities. Munich 1970, pp. 192-193.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities. Munich 1970, p. 171.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities. Munich 1970, pp. 178-179.

- ^ Frank W. Walbank : Kings as gods. Reflections on the ruler cult from Alexander to Augustus. In: Chiron 17 (1987), p. 369.

- ↑ Homer: Odyssey 7.80 f.

- ^ Frank W. Walbank : Kings as gods. Reflections on the ruler cult from Alexander to Augustus. In: Chiron 17 (1987), p. 370; Phillips, C. Robert III .: Synnaos Theos. In: The New Pauly (DNP). Volume 11, Metzler, Stuttgart 2001, ISBN 3-476-01481-9 , Sp. 1156 f.

- ^ Frank W. Walbank : Kings as gods. Reflections on the ruler cult from Alexander to Augustus. In: Chiron 17 (1987), p. 371.

- ^ Gunnel Ekroth: The Sacrificial Rituals of Greek Hero-Cults in the Archaic to the Early Hellenistic Period. Liége 2002, I, 138.

- ^ Frank W. Walbank : Kings as gods. Reflections on the ruler cult from Alexander to Augustus. In: Chiron 17 (1987), p. 372.

- ↑ a b c Angelos Chaniotis : The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers. In: Andrew Erskine (Ed.): A companion to the Hellenistic world. Blackwell, Oxford 2003, p. 432.

- ↑ Duris: The Fragments of the Greek Historians 76 F13, in Athenaios 6,253b – f.

- ↑ Demochares: The Fragments of the Greek Historians 75 F2, in Athenaios 6,253b – f.

- ↑ Angelos Chaniotis : The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers. In: Andrew Erskine (Ed.): A companion to the Hellenistic world. Blackwell, Oxford 2003, p. 431.

- ^ Translation after Hans-Joachim Gehrke , Helmuth Schneider : Geschichte der Antike. Source volume. Metzler, Stuttgart et al. 2007, p. 158 Q 135 .

- ↑ Angelos Chaniotis : The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers. In: Andrew Erskine (Ed.): A companion to the Hellenistic world. Blackwell, Oxford 2003, p. 433.

- ^ Translation after Hans-Joachim Gehrke, Helmuth Schneider: Geschichte der Antike. Source volume. Metzler, Stuttgart et al. 2007, p. 158 Q 135 .

- ↑ The Fragments of the Greek Historians 75 F1.

- ↑ a b Angelos Chaniotis : The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers. In: Andrew Erskine (Ed.): A companion to the Hellenistic world. Blackwell, Oxford 2003, pp. 439-440.

- ↑ a b c Angelos Chaniotis : The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers. In: Andrew Erskine (Ed.): A companion to the Hellenistic world. Blackwell, Oxford 2003, p. 441.

- ↑ Angelos Chaniotis : The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers. In: Andrew Erskine (Ed.): A companion to the Hellenistic world. Blackwell, Oxford 2003, p. 440.

- ↑ a b Angelos Chaniotis : The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers. In: Andrew Erskine (Ed.): A companion to the Hellenistic world. Blackwell, Oxford 2003, p. 438.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, p. 17.

- ↑ Angelos Chaniotis : The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers. In: Andrew Erskine (Ed.): A companion to the Hellenistic world. Blackwell, Oxford 2003, pp. 438-439.

- ↑ a b Angelos Chaniotis : The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers. In: Andrew Erskine (Ed.): A companion to the Hellenistic world. Blackwell, Oxford 2003, p. 435.

- ↑ a b Angelos Chaniotis : The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers. In: Andrew Erskine (Ed.): A companion to the Hellenistic world. Blackwell, Oxford 2003, p. 436.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, pp. 138-139.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, pp. 140–144, here p. 143.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, pp. 144-147.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, pp. 144-147; Gregor Weber : The Ptolemaic cult of rulers and dynasties - a field of experimentation for Macedonians, Greeks and Egyptians In: Linda-Marie Günther , Sonja Plischke: Studies on the pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic cult of rulers (= Oikumene. Studies on ancient world history. Volume 9). Verlag Antike, Berlin 2011, pp. 82, 86, 88.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, pp. 144-147.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, pp. 147-153.

- ↑ Philochoros 328, F 166 == Scholion Pindar Nemea 3, 4.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, pp. 153-155.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, pp. 156-159.

- ^ The Fragments of the Greek Historians 76 F71. 26. 404.

- ↑ a b c d e f Angelos Chaniotis : The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers. In: Andrew Erskine (Ed.): A companion to the Hellenistic world. Blackwell, Oxford 2003, p. 434.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, p. 5.

- ↑ Frank W. Walbank rates it as a hero cult. Frank W. Walbank : Kings as gods. Reflections on the ruler cult from Alexander to Augustus. In: Chiron 17 (1987), p. 373.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, pp. 8-9.

- ^ Frank W. Walbank : Kings as gods. Reflections on the ruler cult from Alexander to Augustus. In: Chiron 17 (1987), p. 374.

- ^ Wilhelm Tomaschek : Aornos 2 . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume I, 2, Stuttgart 1894, Col. 2659.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, p. 5.

- ↑ Strabo 14,640.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, pp. 18-19.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, p. 20.

- ↑ a b c Frank W. Walbank : Kings as gods. Reflections on the ruler cult from Alexander to Augustus. In: Chiron 17 (1987), p. 365.

- ↑ Plutarch: moralia 219E.

- ↑ Aelianus Tacticus VH 2,19 .; Hypereides , v 6.21 .; Athenaios 6,251 b.

- ^ Frank W. Walbank : Kings as gods. Reflections on the ruler cult from Alexander to Augustus. In: Chiron 17 (1987), p. 374.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, pp. 58-59.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, pp. 62-63.

- ↑ a b c Angelos Chaniotis : The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers. In: Andrew Erskine (Ed.): A companion to the Hellenistic world. Blackwell, Oxford 2003, p. 437.

- ↑ Stefan Pfeiffer: Rulers and dynasty cults in the Ptolemaic empire. Systematics and classification of cult forms. Munich contributions to papyrus research and ancient legal history. Munich 2008, p. 58.

- ↑ Angelos Chaniotis : The Divinity of Hellenistic Rulers. In: Andrew Erskine (Ed.): A companion to the Hellenistic world. Blackwell, Oxford 2003, p. 442.

- ↑ Stefan Pfeiffer: Rulers and dynasty cults in the Ptolemaic empire. Systematics and classification of cult forms. Munich contributions to papyrus research and ancient legal history. Munich 2008, pp. 59–61.

- ↑ Stefan Pfeiffer: Rulers and dynasty cults in the Ptolemaic empire. Systematics and classification of cult forms. Munich contributions to papyrus research and ancient legal history. Munich 2008, pp. 49–51.

- ↑ Stefan Pfeiffer: Rulers and dynasty cults in the Ptolemaic empire. Systematics and classification of cult forms. Munich contributions to papyrus research and ancient legal history. Munich 2008, p. 51.

- ↑ Stefan Pfeiffer: Rulers and dynasty cults in the Ptolemaic empire. Systematics and classification of cult forms. Munich contributions to papyrus research and ancient legal history. Munich 2008, p. 64.

- ↑ Stefan Pfeiffer: Rulers and dynasty cults in the Ptolemaic empire. Systematics and classification of cult forms. Munich contributions to papyrus research and ancient legal history. Munich 2008, pp. 28 and 115–117.

- ↑ Stefan Pfeiffer: Rulers and dynasty cults in the Ptolemaic empire. Systematics and classification of cult forms. Munich contributions to papyrus research and ancient legal history. Munich 2008, pp. 115–117.

- ↑ Stefan Pfeiffer: Rulers and dynasty cults in the Ptolemaic empire. Systematics and classification of cult forms. Munich contributions to papyrus research and ancient legal history. Munich 2008, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ Stefan Pfeiffer: Rulers and dynasty cults in the Ptolemaic empire. Systematics and classification of cult forms. Munich contributions to papyrus research and ancient legal history. Munich 2008, p. 120.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, pp. 82-85.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, p. 88.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, p. 91.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, pp. 82-85.

- ^ Frank W. Walbank : Kings as gods. Reflections on the ruler cult from Alexander to Augustus. In: Chiron 17 (1987), p. 379.

- ↑ Christoph Michels : Dionysus Kathegemon and the Attalid ruler's cult. Reflections on the representation of power by the kings of Pergamon . In: Linda-Marie Günther , Sonja Plischke: Studies on the pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic cult of rulers , Berlin 2011, pp. 117 and 139 ( online ).

- ↑ Christoph Michels : Dionysus Kathegemon and the Attalid ruler's cult. Reflections on the representation of power by the kings of Pergamon . In: Linda-Marie Günther , Sonja Plischke: Studies on the pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic cult of rulers , Berlin 2011, p. 119.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities. Munich 1970, pp. 124-125.

- ↑ Christoph Michels : Dionysus Kathegemon and the Attalid ruler's cult. Reflections on the representation of power by the kings of Pergamon . In: Linda-Marie Günther , Sonja Plischke: Studies on the pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic cult of rulers , Berlin 2011, p. 121.

- ↑ Christoph Michels : Dionysus Kathegemon and the Attalid ruler's cult. Reflections on the representation of power by the kings of Pergamon . In: Linda-Marie Günther , Sonja Plischke: Studies on the pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic cult of rulers , Berlin 2011, p. 122.

- ↑ Christoph Michels : Dionysus Kathegemon and the Attalid ruler's cult. Reflections on the representation of power by the kings of Pergamon . In: Linda-Marie Günther , Sonja Plischke: Studies on the pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic cult of rulers , Berlin 2011, p. 137.

- ↑ Christoph Michels : Dionysus Kathegemon and the Attalid ruler's cult. Reflections on the representation of power by the kings of Pergamon . In: Linda-Marie Günther , Sonja Plischke: Studies on the pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic cult of rulers , Berlin 2011, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Christoph Michels : Dionysus Kathegemon and the Attalid ruler's cult. Reflections on the representation of power by the kings of Pergamon . In: Linda-Marie Günther , Sonja Plischke: Studies on the pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic cult of rulers , Berlin 2011, pp. 129 and 130.

- ↑ Christoph Michels : Dionysus Kathegemon and the Attalid ruler's cult. Reflections on the representation of power by the kings of Pergamon . In: Linda-Marie Günther , Sonja Plischke: Studies on the pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic cult of rulers , Berlin 2011, p. 131.

- ↑ Christoph Michels : Dionysus Kathegemon and the Attalid ruler's cult. Reflections on the representation of power by the kings of Pergamon . In: Linda-Marie Günther , Sonja Plischke: Studies on the pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic ruler cult , Berlin 2011, p. 117.

- ↑ a b Bruno Jacobs : Nemrud Dağı . In: Ehsan Yarshater (Ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica , as of February 25, 2011, accessed on October 22, 2019 (English, including references)

- ↑ Peter Franz Mittag : On the development of the "rulers" and "dynasty cults" in Kommagene. In: Linda-Marie Günther , Sonja Plischke: Studies on the pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic cult of rulers (= Oikumene. Studies on ancient world history. Volume 9). Verlag Antike, Berlin 2011, p. 150.

- ↑ Peter Franz Mittag : On the development of the "rulers" and "dynasty cults" in Kommagene. In: Linda-Marie Günther , Sonja Plischke: Studies on the pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic cult of rulers (= Oikumene. Studies on ancient world history. Volume 9). Verlag Antike, Berlin 2011, pp. 152–155.

- ↑ Peter Franz Mittag : On the development of the "rulers" and "dynasty cults" in Kommagene. In: Linda-Marie Günther , Sonja Plischke: Studies on the pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic cult of rulers (= Oikumene. Studies on ancient world history. Volume 9). Verlag Antike, Berlin 2011, p. 153.

- ↑ Peter Franz Mittag : On the development of the "rulers" and "dynasty cults" in Kommagene. In: Linda-Marie Günther , Sonja Plischke: Studies on the pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic cult of rulers (= Oikumene. Studies on ancient world history. Volume 9). Verlag Antike, Berlin 2011, p. 153.

- ^ Franz Cumont : Artagnes . In: Paulys Realencyclopadie der classischen Antiquity Science (RE). Volume II, 1, Stuttgart 1895, column 1302.

- ↑ a b Geo Widengren : Antiochus of Commagene . In: Ehsan Yarshater (ed.): Encyclopædia Iranica . Volume 2 (Fasc. 2), pp. 135–136, as of August 5, 2011, accessed on October 22, 2019 (English, including references)

- ↑ Peter Franz Mittag : On the development of the "rulers" and "dynasty cults" in Kommagene. In: Linda-Marie Günther , Sonja Plischke: Studies on the pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic cult of rulers (= Oikumene. Studies on ancient world history. Volume 9). Verlag Antike, Berlin 2011, p. 154.

- ↑ Peter Franz Mittag : On the development of the "rulers" and "dynasty cults" in Kommagene. In: Linda-Marie Günther , Sonja Plischke: Studies on the pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic cult of rulers (= Oikumene. Studies on ancient world history. Volume 9). Verlag Antike, Berlin 2011, p. 154.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, p. 129.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, p. 130.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, pp. 132-133.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, pp. 136-137.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, p. 222.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, pp. 223-224.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, p. 225.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, p. 226.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, p. 236.

- ↑ Christian Habicht : God-humanity and Greek cities . Munich 1970, p. 265.

- ↑ Stefan Pfeiffer: Rulers and dynasty cults in the Ptolemaic empire. Systematics and classification of cult forms. Munich contributions to papyrus research and ancient legal history. Munich 2008, p. 118.

- ↑ Peter Franz Mittag : On the development of the "rulers" and "dynasty cults" in Kommagene. In: Linda-Marie Günther , Sonja Plischke: Studies on the pre-Hellenistic and Hellenistic cult of rulers (= Oikumene. Studies on ancient world history. Volume 9). Verlag Antike, Berlin 2011, p. 160.