Kobsa

Kobsa ( Ukrainian кобза ), also kobza , is a plucked bowl-neck lute that is played in Ukrainian folk music . Two types of lute, each with six gut strings, are known from the 16th to 18th centuries, one of which was similar to the Romanian kink neck lute cobză and the other belonged to the long neck lute. In the course of time, the kobsa received additional short strings on one side of the ceiling, which are only plucked empty, and developed into the larger, asymmetrical stringed instrument bandura with a string level that runs across the ceiling like a box zither . The terms kobsa and bandura were used interchangeably in the 19th century. The older lute type kobsa disappeared at the beginning of the 20th century in favor of the now popular bandura , but was reintroduced in different variants in the 1970s.

The kobsa was the instrument of the kobsar , a mostly blind bard who sang Christian songs ( psalmy , singular psalma ) and epic heroic songs of the Cossacks called dumky (singular dumka ) . The most famous kobsar in the 19th century, when the bard tradition was at its peak, was Ostap Weressai .

etymology

The etymology of the two instrument names kobsa and bandura points in opposite directions: to Asia and to Europe. This has to do with the country's historical relationships and belongs to the question of whether the special construction of the instruments with side zither strings has an Eastern or Western origin. The Ukrainian and Russian word kobsa , which occurs in Romanian in the spelling cobză , is connected with Hungarian koboz , from which Old Czech kobos, kobes and Old Polish kobosa are also derived. Kobos and kobes were probably names for lute instruments, for example in the Bohemarius major dictionary of the Czech writer Klaret from 1369, in the Boskowitz Bible from Olomouc from 1417, in the handwriting of the chronicler Oldřich Kříž von Telč from the middle of the 15th century and in Pernštejn -Bible from 1471. The word kobza appears in several Czech sources from the 16th century , which apparently referred to an instrument of folk music. In Šimon Lomnický z Budče states (1590) in "Cupid's basement": "Young people ... with Lute, Kobza, zither roams around at night ..." and in January Amos Comenius explains the instrument in 1694 as follows: "Kobza - the fiddle (violin) from Sayten and vertebrae with which the Sayten be tightened. "Under kobza so were 15-16. Century understood at least a plucked lute and a string instrument. A drawing from the first half of the 18th century shows the name kobza for a box zither in Bohemia , which probably already existed there in the 17th century. Up until the 19th century, kobza could have meant other folk musical instruments in certain regions, such as the hurdy-gurdy , grater drum and bagpipe . A Romanian source of 1725 tells of "guys who with a girl on his back in the Prut swam and cobuz played." With Romanian cobuz here according to Polish kobza or - consistently in the debate koza - "goat" and "bagpipe" meant. The bagpipe koza occurs to this day in the southern Polish mountainous region.

The word environment in the Slavic languages goes back to the Old Turkish qopuz , "lute". In most Turkic languages , the forms derived from qopuz mean “string instrument”, for example komuz for a Kyrgyz long-necked lute, agach kumuz for a Dagestan sound and kobys for a bowl- necked lute bowed in Central Asia. Usually the Central Asian sounds are canceled and the Slavic sounds with a related name are plucked. The name is also on Asian Maultrommeln passed that Temir Komuz , Chomus, kumys, Kobus and are called similar. For the Siberian Yakuts , chomus can also mean "wind instrument".

The Turkish-speaking word qopuz , which comes from pre-Islamic times, has passed into Persian and Arabic and is used as the name of the Yemeni short-necked qanbus . The instrument and the name came from southern Arabia with Muslim traders to Indonesia, where the gambus lute is played in Islamic music, and from there to the East African coast ( gabbus in Zanzibar ). The Turkish-Arabic name of the instrument qopuz seems to have come to Europe in the early Middle Ages and - as the Arabic rabāb became rebec - to have referred to a European lute instrument. In Heinrich von Neustadt's religious verse story Von Gottes Zukunft , which originated at the beginning of the 14th century, the following stringed instruments are named in verses: " Psalteries and welsche fioln / Die kobus with the luten / Damburen with the bucken ..." The word kobus , das Curt Sachs (1930) refers to a mandora , according to Curt Sachs (1940) he probably came to Western Europe as a koboz from the Byzantine Empire via Hungary, since in a Greek treatise on alchemy written around 800 there was a stringed instrument called kobuz or pandurion with three to five Strings and seven frets is mentioned.

The Middle High German damburen , like Arabic-Persian tanbūr, goes back to ancient Greek pandura , which in turn is linked to the even older pandur in the Sumerian language . Bandura in Ukrainian probably came via Polish from southern and western European languages, which contain a number of lute instruments with related names: German mandora, Pandora , English bandore , Spanish bandurria; the linguistic affinity extends to panduri and pondur in the Caucasus and to South Asia ( dambura , tanpura ).

origin

From the 8th century BC Chr. Are Elamite clay figures from Iran received on which the outlines of the oldest known short necked lutes are seen without a separate neck. They are considered to be the forerunners of the early form of the barbat , which, according to an illustration from the 3rd century, was a presumably three-stringed lute with a pear-shaped body in the Sassanid period . With the Islamic expansion from the 7th century onwards, the pear-shaped type and other short-necked sounds with names like mizhar and ʿūd spread throughout the Arab world. The pear-shaped type of lute with a short neck, which differs significantly from the long-necked lute known in Persian tanbur , also appeared in Choresmia (Central Asia) in the 8th and 9th centuries and is depicted in a Byzantine manuscript from the 13th century: In the Codex Hagios Stavros 42 , which contains the legend of Barlaam and Josaphat , which was widespread in the 11th century , can be found on fol. 164 v the miniature of the "loved by women", Indian prince Josaphat, playing a lute. The moderately well-preserved depiction shows a pear-shaped lute with presumably three strings. In the 13th century, the short-necked lute , which was introduced to Europe via al-Andalus , appears in many Spanish illustrations and the Christian Spanish poet Juan Ruiz called the instrument guitara morisca (" Moorish guitar") in the 14th century .

The existence of stringed instruments among the Slavs in the early Middle Ages is documented by literary sources. The early Byzantine historian Theophylaktos Simokates reports at the beginning of the 7th century of three Slavic prisoners who were deported from the Baltic to Thrace in 591 and who carried “kitharas” with them, by which he probably meant the slender Baltic psalterium gusle . According to an Arabic travel report from the 10th century, the Eastern Slavs had an eight-string lute ( ʿūd ) and another lute ( tanbur ). Ibn Fadlān , the author of the long travelogue, describes the funeral ceremony of a trade caravan of the Rus in the area of the lower Volga , although it is not reliably possible to determine which nationality the group was and what kind of stringed instrument it was.

The oldest surviving illustration and also the earliest clear evidence of a lute in the Ukraine, which can be imagined as the forerunner of the kobsa , can be found on a mural in the St. Sophia Cathedral in Kiev from the 11th century, on which musicians and acrobats also flute ( cf. the Ukrainian flute sopilka ), playing the trumpet or shawm , psaltery and cymbal . Like the Byzantine Stavros lute and the Central Asian komuz, the lute, of which only the outline can be roughly recognized, is pear-shaped and has a long neck. Its shape corresponds to the Ukrainian kobsa depicted in the 17th century . Regarding the origin of the motifs, we can only say that the wall paintings and mosaics in the cathedral were made according to Byzantine models.

The Russian poet Karion Istomin (1640s - around 1718) wrote a Bukwar , an alphabet exercise book in Moscow in 1694 , in which musicians are depicted on one side, a violin, a helmet-shaped box zither ( gusli ), a longitudinal flute and a lute with a circular Play corpus. The illustration is only revealing for the instruments used in Moscow; the appearance of Ukrainian sounds at that time cannot be derived from it. Above all, this concerns the question of when the characteristic lateral zither strings were added to the Ukrainian sounds. These high-pitched treble strings do not increase the range of the instrument, because high notes can just as easily be obtained by shortening the melody strings. This distinguishes them from the arch-lute , which by adding bass strings that lead to a second pegbox on the extended neck, expand their range downwards and increase their sonority. The term arciliuto was in use in Italy before 1590; However, it is not known for which type of lute it applied. The prefix arci- vor liuto ("lute") stands for a kind of enlargement, whereby the extension of the neck should have been meant. A special form of the Erzlaute or Erzcister , the invention of which is attributed to the English composer Daniel Farrant at the beginning of the 17th century , was called poliphant in English . The instrument has a pear-shaped lute body with a long neck with frets for bass strings, a group of high zither strings on the right and a harp-like curved bow on the left for a group of longer strings, around three dozen strings in total. There is a copy of this “harp cister” with the signature of the manufacturer Wendelin Tieffenbrucker , which is dated around 1590. By the middle of the 17th century, this curious string instrument, which most closely resembles the Ukrainian lute, had become rare. Another, equally unusual string instrument, which typologically corresponds more to a zither and is in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna, is mentioned in an inventory catalog from 1596. Its strings are attached to individual bars at the lower ends, which are positioned in an oblique, punctiform row on the ceiling. At the top, all but three strings are tied to two pegboxes that barely protrude beyond the body. The three shortest strings lead to small pegs that stick next to them in the frame. The strings on the side of the Ukrainian lute could have been taken over from examples like these from the west at this time, if it is not a regional development. There is evidence that the classic form of the ore lute with long bass strings came to Eastern Europe, where it became generally known in the Ukraine in the 18th century under the name torban (derived from " theorbo ") and is still used there today. In Russia the arch lute torban was played only during the first quarter of the 19th century and in Poland until the end of the 19th century.

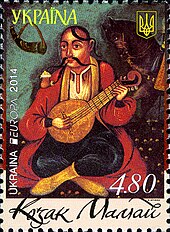

The earlier form of the kobsa without zither strings was still used in the 18th century and possibly until the 19th century. In the Cossack Mamaj mentioned, Ukrainian genre painting of the 18th century and the early 19th century Cossack displayed in different positions, all of a Kobsa play or Kobsa who stand beside him. The sounds shown vary considerably in their shape and number of strings.

According to a theory propagated by Belarusian researchers, there is a kinship between Scandinavian, Baltic and Russian box zithers ( gusli ), which is based on a cultural relationship that developed during the hegemony of the Khazars , which included Ukraine in the south. According to the theory of the Ukrainian bandura player Heorhij Tkachenko (1898–1993) , the helmet-shaped gusli type, which was depicted in Russia from the 14th century onwards, could have formed the template for the wide body with the strings on the sides. This hypothetical formal transformation would have taken place within an East Slavic cultural layer to which the old epic tradition of the gusli bards and the epic heroic songs ( dumky ) of the bandura players belonged. The word contexts gusli / husle and kobsa equally denote lute instruments and zithers. The structurally easy transition between the two groups of instruments illustrate a kobza -called Bohemian fingerboard zither, the strings are truncated at frets in the four and their like a Scherr zither side bulged body to a bandura recalls, and a Mittenwalder zither from the 18th century, devoted with its symmetrical, pear-shaped body, has moved little from the oldest lute type.

Depending on the focus of attention, the kobsa focuses on the linguistic and corpus shape connection to Asian sounds with Mongolian - Tatar origin or the development of the short pages from regional tradition or as a Western cultural import. Analogous hypotheses were put forward on the question of the origin of the bandura , or more precisely, a Ukrainian lute called bandura . The Russian composer Alexander Sergejewitsch Faminzyn drew the much-cited conclusion in his study on "The Domra and Related Musical Instruments" (Saint Petersburg, 1891), which was important for the history of Russian musical instruments: Because the oldest known mention of the bandura in Ukraine dates back to 1580 and an instrument called the bandora was invented in 1562 by the English lute maker John Rose, the Ukrainian lute must have come from England in the meantime. Specifically, the Spanish adopted the instrument as banduirra and the Italians as pandora . Italian professional musicians brought it to the court of the Polish ruler Sigismund II (r. 1548–1572), from where it was brought to the Ukraine and there it became a folk musical instrument. A Polish source contradicts this, according to which there was a court bandura player in Cracow as early as 1441 , as the Polish music historian Adolf Chybiński (1949) mentions. In addition, among the court musicians of the Polish King Sigismund I , who ruled from 1507 to 1548, there was a Ukrainian bandurist, with whom the king also played chess.

Design

Research into the past appearance of kobsa and bandura began in the late 19th century. Since then, numerous ethnomusicologists, folklorists and instrument makers have dealt with the different shapes, moods, musical use and cultural significance of the lute forms. In the absence of precise historical descriptions, it can only be concluded from illustrations that there were two different types of lute from the 16th century, when lute instruments became popular in the Ukraine, to the 18th century, both of which were either carved from a block of wood based on Central Asian models, had a massive body or a body glued from wood chips, as with the lute . One form was like the Romanian cobză a short necked lute, the other a long necked lute like the dombra . Both were usually covered with six gut strings. In the following, kobsa or bandura meant a short-necked lute.

At an unknown time (late 17th / early 18th century) the short-necked lute was given four to six short, empty treble strings ( pristrunki ) on the right side of the top of the body in addition to the melody strings that were shortened with the fingers on the fingerboard . Although the terms kobsa and bandura were sometimes used synonymously in the 19th century , it was notably the kobsa whose number of strings remained constant and which gradually lost popularity, while the bandura was equipped with other short zither strings and became the most popular Ukrainian plucked instrument. By the end of the 19th century, Ukrainian lutes had between 8 and 30 strings. As the number of strings increased, the musicians refrained from shortening the long strings on the fingerboard. Since every instrument was handcrafted by an instrument maker in the village or by the musician, there were no standardized sizes and shapes. The body of the kobsa was more or less rounded at the bottom and between 5 and 20 centimeters thick. It was often made from willow wood, with more valuable specimens from maple, and pine wood was used for the top. Sheep gut strings were replaced by copper and steel wire strings in the 19th century. There was no uniform string tuning; the strings were mainly tuned for scales with a diminished third , an augmented fourth, and a diminished seventh . In the first two decades of the 20th century, the asymmetric wide shape had the bandura enforced and in the 1930s began, the only empty plucked strings of the bandura not as far diatonic but chromatically to vote.

The classical form of the kobsa is the instrument played by Ostap Weressai (1803–1890), the most famous kobsar of the 19th century. This Kobsa has a symmetrical, as compared to the Romanian cobză very broad, pear-shaped body, which merges into a short neck, a kinked backwards to the peg box is fitted with lateral wooden pegs. The pegbox ends in an upturned snail . Six strings run from the lower end over a wide flat bridge over the fretless fingerboard to the pegs. In addition, there are six short strings that are not stretched exactly parallel to the melody strings on the right side of the top over the same bridge up to voice pegs protruding vertically from the top on the upper edge of the body. Ostap Weressai held his kobsa upright and tilted slightly towards the left shoulder, propping it on his thighs and plucking the strings with the fingers of his right hand. He shortened the melody strings with the fingers of his left hand, while almost all other singers in his day only plucked all the strings empty and with both hands. Some musicians used a pick on a ring drawn over the middle finger.

At the beginning of the 20th century the kobsa had largely disappeared, but was reintroduced into a revitalized folk music in Kiev and Kharkiv in the last quarter of the 20th century . Mykola Prokopenko deserves special mention, in the 1970s he designed a series of four kobza with frets, graduated in size according to the violin family , whose strings are tuned to fifths apart . He was supported in this by the Ukrainian Ministry of Culture. These modern instruments have an egg-shaped body, four or six strings and do without the short zither strings. Their shape and style of playing has little in common with the historical kobza , but their name is supposed to tie in with the Ukrainian tradition and replace the Central Asian long-necked lute dombra in the orchestra . The orchestra musicians value the new kobza variants behind the bandura .

The kobsa type played by Ostap Weressai in the 19th century has not survived, but the form and style of playing are well known from the description by the composer Mykola Lyssenko (1842–1912). Reconstructions made by several instrument makers from the 1980s onwards, with which musicians perform Weressai's repertoire today, are based on this.

Style of play

Blind bards

The fresco in the Sophia Cathedral in Kiev from the 11th century shows musicians and wandering folk entertainers ( Skomorochen ) accompanying their spectacles and chants with stringed instruments. The 13th century Galician-Volhyn Chronicle mentions that the famous Galician bard Mitusa considered himself so important that in 1241 he refused to serve Prince Daniel (later King of Russia). Sources from the 14th and 15th centuries mention Ukrainian musicians with hurdy-gurdy ( lira ) at Polish courts and the kobsa / bandura player Churilo. In Poland, besides Ukrainian and Belarusian singers with the introduced instruments kobsa and lira, there were other ballads and storytellers who accompanied each other on the local fiddle suka . The snamennyj , an old Russian liturgical style of singing, is said to have developed from secular vocal music in the 11th century .

A Ukrainian lute player of the 18th century who worked as a court musician in Saint Petersburg was Tymofij Bilohradskyj (around 1710 - around 1782). The most important musicians and singers in Saint Petersburg in the 18th century came from the Ukraine; Ukrainian folk song melodies were widespread and also popular with the Russian tsars. The proportion of Ukrainian songs in Russian folk song collections, which were published in Saint Petersburg in the 18th century, played a major role in the development of national Ukrainian music. The accompanying instruments of the old Ukrainian singing tradition include kobsa, bandura, torban , violin, basolya (bass violin), cimbalom (dulcimer), lira and sopilka (longitudinal flutes).

Before the forced collectivization in the Soviet Union in the early 1930s, the instrumentalists of Ukrainian folk music were divided into part-time musicians who performed for entertainment at weddings and other festive occasions in order to supplement their income from agriculture; Musicians of special regional styles , such as the players of the trembita (wooden trumpet) in the Hutsulen ; the bards, who are differentiated as kobsars ( kobsari ) or lira players ( lirnyky ) according to their accompanying instrument, and finally the amateurs, who occasionally appeared in public for their amusement. Blind singers were often referred to as kobsars in general, regardless of the instrument they played. Its distribution area in the 19th century was the middle and east of Ukraine, it was roughly within the limits of the Cossack hetmanate . They were not found in western Ukraine or Galicia.

The blind bards still appeared in the villages with kobsa and lira in the 1930s until many of them were arrested like other minorities and murdered as alleged traitors during the time of the Great Terror - accused of nationalist propaganda. The atheistic Soviet ideology also blamed the Cobars for their connections to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church . At the beginning of the 20th century, according to a rough estimate, there were well over 2,000 blind bards in Ukraine, by the middle of the 20th century they had disappeared except for "a handful" and by the beginning of the 1990s they had completely disappeared. In their place came a large number of bandura players who perform a stylistically mixed, more urban repertoire that has little in common with that of the bards.

repertoire

The numerous vocal styles of Ukrainian folk music include the epic heroic songs dumky (also dumy , singular dumka , думка, or duma , дума), which were recited by the bards, usually accompanied by kobsa, bandura or lira . In Poland, dumky came into fashion during the period of national romantic renewal at the beginning of the 19th century, when the piano began to be used to accompany them. Form and content are the sometimes long over 300 lines of verse Dumky with medieval Russian heroes songs byliny (singular Bylina ) and the Tale of Igor's combined.

Dumky were first mentioned in 1567 in a Polish chronicle by Stanislaw Sarnitski (around 1532–1597) and first written down in 1693 in the collection of stories Kozak Hołota (" Cossack- Landstreicher"). The approximately 50 recorded dumky were composed by Cossacks who appeared as nomadic equestrian associations in the 15th century. An anonymous author wrote from Podolia in 1617 about the pleasant life of soldiers: “In the early morning they play their Dumy on the kobsa” and in a verse from the same region dating back to the 17th century that introduces a dumka , the relationship of the musician comes to his instrument: "Tell me, my dear Kobza, whether your Duma also knows something."

After an idealized idea, the Cossacks carried a kobsa with them on their campaigns and accompanied them to their songs about their latest experiences at the evening campfire. In order to explain the change of instrument from these riding and fighting song singers to the later blind bards, it is helpful to introduce a hypothetical transition stage, as suggested by Natalie Kononenko (1990). Accordingly, a specialization took place at a certain time and only the wounded fighters who remained in the camp or the old men played and sang the heroic songs. Having become professional singers, they moved on with the corsairs and, incidentally, recruited new participants for the struggle for freedom with the songs. For this they were supported and cared for by their regiments. This would connect the musical instrument and the songs with one another and move over to the social area of the handicapped and the weak.

Later, the dumky were performed by professional, mostly blind bards who accompanied each other on a kobsa or lira . The Kobsars thus belonged to a tradition of blind singers and storytellers known in many cultures, which ranges from the ancient Aoden to the Turkish Aşık to the Japanese Goze . The Kobsars were organized in guilds, their recognition as professional singers and kobsa players was preceded by three to six years of instruction from a guild master. During this time they had to learn the epic narratives, the melodies, the playing of the accompanying instruments and the set rules of the guild. Most blind singers had families and permanent homes to which they returned after traveling as traveling musicians for a period of the year. They appeared on market days in villages and towns, in private homes and in monasteries. Their radius of action was limited to a few day trips on foot around their home town. With their income (money and food), the Kobsars contributed significantly to the income of their families. The appearances at the annual festivals for the patron saint of a village were particularly profitable.

The dumky consist of stanzas of different lengths with verse lengths of about 6, 16 or 18 syllables. The range of the sung melody is a fifth or fourth; it can only exceed an octave in dramatic passages. The key is often a kind of Doric mode . A dumka lecture often begins with a melodic opening motif ( zaplatjka ) without any instrumental accompaniment. This is followed by the actual narration ( ustupi ), which is interrupted by instrumental interludes. The performance ends with a virtuoso play on the stringed instrument. Three parts follow one another in the narrative: a recitative (“sigh”) on a single note, a more melodic presentation and a melodically ornamented ending. The topics of the dumky in the older text layer include the war events during the advance of the Ottoman Empire into the territory of the Russian Tatars and in later texts, which deal with the clashes between Cossacks and Poles, the Khmelnytskyi uprising against the Kingdom of Poland-Lithuania Mid 17th century. This began as a social upheaval supported by the Ukrainian rural population and took on the dimension of a national liberation struggle. Younger dumky deal with the October Revolution in Russia in 1917.

The repertoire of the Cobars consisted only to a small extent of the epic genre dumka . The majority of them performed Christian songs ( psalmy ). There were bards who knew only a few dumky but had a much larger repertoire of psalmy , which made them the most money. A typical Christian song is Chrystu na chresti ("Christ on the Cross"). They also had satirical songs and dance styles in their program.

A performance usually began with a begging song, in which an apology from Kobsar for his situation as a supplicant was built. If nothing else came after that, the kobzar added a prayer. Otherwise he ended the program with a song of thanks. Especially the religious songs, which appealed to the listeners' fear of God, contained the invitation to give alms.

Current kobsa players who play modern Ukrainian folk music that is partly related to the old “Cossack songs” and often has a melancholy mood are Wolodymyr Kuschpet (* 1948), Eduard Drach (* 1965) and Taras Kompanitschenko (* 1969).

Cultural meaning

The historical Kobsars are symbols of the Ukrainian national culture. Taras Shevchenko (1814–1861) is considered to be the founder of national Ukrainian poetry ; his main work is the poetry collection Kobsar, first published in 1840 . The title was later carried over to all of this author's poetic work. Numerous editions appeared, each time containing previously unpublished poems. After the publication of the work was prohibited by the Ems Decree of 1876, it was first published in Prague and subsequently translated into numerous languages. In the poem Perebendja , which is included in the first edition of Kobsar , and elsewhere, Shevchenko spreads the idea of the Kobsars as homeless vagabonds. This image was taken over in many other descriptions of the blind bards, but does not correspond to the reality of the time.

Until the beginning of the 20th century, the blind bards had a different, preferred social position compared to all other - semi-professional or amateur - village musicians. They saw themselves as outsiders and were not perceived by the villagers as part of their community, as they did not take part in the vital seasonal rituals and family celebrations. The God-given fate of blindness, according to many, gave them a higher purpose in life and a role as moral authority. On the other hand, magical abilities that were not of divine origin were ascribed to the Cobars. Ostap Weressai explained his blindness with the evil eye ( oslip z prystritu ), which met him as a small boy. Their special role as outsiders for the village community, which made them a social minority, was their undoing in the early Soviet times.

The Kobsars are honored today because they sang songs of the Cossacks who stood up for the protection of Ukraine from external influences and because they themselves suffered under the Soviet policy of harmonization. The Cobars are a symbol of the resistance of the Ukraine towards Soviet rule. The appreciation of the Cobars as the singers of dumky is an attribution today, because in fact they sang mainly Christian songs and the word dumka was not used by the Cobars or their listeners in the 19th century and until the 1920s. There were several regional words with which both different genres were often referred to together, or the Cobars simply called their repertoire "Cossack songs" or "prisoner songs". Notwithstanding this, the Cobars retained their prominent position as a moral authority in society's consciousness. In Ukrainian folk music, the revival of Cossack songs - as in Russia - has led to a new, sophisticated genre of vocal and instrumental music. Such a revival of a popular music scene takes place in parallel in other Eastern European countries, as with the Hungarian dance house movement Táncház , with the kokle -music Latvia or highlanders -music in southern Poland, where the fiddle złóbcoki was rediscovered.

The basic pattern of the idealized Kobsar narrative tradition is taken up again and again in a variety of ways in Ukrainian culture. In the 2014 feature film Powodyr (“The Leader”) by director Oles Sanin, for example, the blindness of the protagonist playing kobsa is only part of his suffering, the real cause of which is to be found in the political situation of Russian domination. The film was released shortly after the Euromaidan protests, when tensions between Ukraine and Russia reached a temporary peak.

literature

- Kobza. In: Grove Music Online , May 25, 2016

- Andrij Hornjatkevyč: The Kobza and the Bandura: A Study in Similarities and Contrasts. In: Folklorica , Volume 13, 2008, pp. 129-143

- William Noll: Ukraine. In: Thimothy Rice, James Porter, Chris Goertzen (Eds.): Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. Volume 8: Europe . Routledge, New York / London 2000, pp. 806-825

- William Noll: The Social Role and Economic Status of Blind Peasant Minstrels in Ukraine . In: Harvard Ukrainian Studies , Volume 17, No. 1/2, June 1993, pp. 45-71

Web links

- Roman Turovsky: Ukrainian Musical instruments. torban.org

- S. Grytsa: Kobza- and lyre playing tradition in Ukrainian Polissya. storinka-m.kiev.ua

- Дума про Хведора Безродного Youtube Video (The composer and musician Jurij Fedynskyj, born in the United States in 1975, sings a dumka and plays kobsa .)

Individual evidence

- ^ Ludvík Kunz: The folk musical instruments of Czechoslovakia . Part 1. (Ernst Emsheimer, Erich Stockmann (Hrsg.): Handbook of European Folk Musical Instruments , Series 1, Volume 2) Deutscher Verlag für Musik, Leipzig 1974, p. 58f

- ^ Anca Florea: Wind and Percussion Instruments in Romanian Mural Painting . In: RIdIM / RCMI Newsletter , Volume 22, No. 1, Spring 1997, pp. 23–30, here p. 28

- ^ Gerhard Doerfer : Turkish and Mongolian elements in New Persian. With special consideration of older neo-Persian historical sources, especially the Mongol and Timurid times . ( Academy of Sciences and Literature Mainz. Publications of the Oriental Commission , Volume 16) Volume 1, Franz Steiner, Wiesbaden 1963, p. 536

- ↑ Cf. András Róna-Tas: Language and History: Contributions to Comparative Altaistics . (PDF) Szeged 1986, p. 19f

- ↑ Larry Francis Hilarian: The migration of lute-type instruments to the Malay Muslim world. (PDF) Conference on Music in the world of Islam. Assilah, August 8-13 August 2007, p. 3

- ↑ Document archive / concordance . Middle High German dictionary

- ^ Curt Sachs : Handbook of musical instrumentation . (1930) Georg Olms, Hildesheim 1967, p. 216 f.

- ^ Curt Sachs: The History of Musical Instruments. WW Norton, New York 1940, p. 252

- ↑ Larry Francis Hilarian: The Transmission and Impact of the Hadhrami and Persian Lute-type instrument on the Malay World. P. 5

- ^ Henry George Farmer : The Origin of the Arabian Lute and Rebec . In: The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland , No. 4, October 1930, pp. 767-783, here p. 768

- ↑ Hagios Stavros 42. Barlaam and Joasaph. 13th cent. fol. 164v.

- ↑ Joachim Braun: Musical Instruments in Byzantine Illuminated Manuscripts. In: Early Music , Volume 8, No. 3, July 1980, pp. 312-327, here pp. 321f

- ↑ Curt Sachs, 1940, pp. 251f

- ↑ Alicia Simon: An Early Medieval Slav Gesle . In: The Galpin Society Journal , Volume 10, May 1957, p. 64

- ↑ Lynda Sayce: Archlute . In: Grove Music Online , 2001

- ↑ Ian Harwood: Poliphant . In: Grove Music Online , 2001

- ↑ Alexander Buchner: Handbook of musical instruments. 3rd edition, Werner Dausien, Hanau 1995, p. 102

- ^ Friedemann Hellwig: The Morphology of Lutes with Extended Bass Strings. In: Early Music , Volume 9, No. 4 ( Plucked-String Issue 2) October 1981, pp. 447-454, here p. 453

- ^ Sibyl Marcuse : A Survey of Musical Instruments. Harper & Row, New York 1975, p. 428

- ↑ Andrij Hornjatkevyč, 2008, pp. 131f, 134-136

- ↑ M. Khay: Enclosed Instrumentarium of Kobzar and Lyre Tradition. In: Music Art and Culture , No. 19, 2014, section: Psalnery (gusli)

- ↑ Ludvík Kunz, 1974, p. 54

- ↑ Mittenwald zither with two bulges . Europeana Collections (image)

- ↑ Andrij Hornjatkevyč, 2008, pp. 132f

- ↑ Zinovii Shtokalko: A Kobzar Handbook . Translated and commented by Andrij Hornjatkevyč ( Occasional Research Reports , No. 34) Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, University of Alberta, Edmonton 1989, p. 5; Text archive - Internet Archive

- ↑ MJ Diakowsky: A Note on the History of the Bandura. In: The Annals of the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and Sciences in the US Volume 6, Nos. 3-4, 1958, p. 1419

- ^ William Noll, 2000, p. 815

- ↑ Violetta Dutchak: The Ukrainian Bandura as a musical instrument of the chordophones Group. In: Journal of Vasyl Stefanyk Precarpathian National University , Volume 4, No. 2, 2017, pp. 125-133, here pp. 129f

- ↑ Andrij Hornjatkevyč, 2008, p. 138

- ↑ Andrij Hornjatkevyč, 2008, p 140

- ↑ George A. Perfecky (transl.): The Hypathian Codex. Part Two: The Galician-Volynian Chronicle . Wilhelm Fink, Munich 1973, p. 52 ( Harvard Series in Ukrainian Studies , Volume 16, II)

- ^ Anna Czekanowska: Polish Folk Music: Slavonic Heritage - Polish Tradition - Contemporary Trends. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1990, pp. 167, 173

- ↑ Vladimir Gurevich: St. Petersburg and the emergence of the Ukrainian musical culture. In: Luba Kyyanovska, Helmut Loos (eds.): Ukrainian music. Idea and history of a national musical movement in its European context . Gustav Schröder, Leipzig 2013, pp. 3–9, here p. 7f

- ↑ Sofia Hrytsa: Ukraine. II: Traditional music. 1. Historical background and general features. In: Grove Music Online , 2001

- ^ William Noll, 2000, p. 819

- ^ Natalie O. Kononenko: Ukrainian Minstrels: And the Blind Shall Sing. ( Folklores and Folk Cultures of Eastern Europe ) ME Sharpe, Armonk (New York) 1998, p. 154

- ^ William Noll, 1993, p. 45

- ↑ John Tyrrell: Dumka . In: Grove Music Online , 2001

- ↑ Holota . In: Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- ↑ Alisa El'šekova, Miroslav Antonovič: Duma and Dumka. I. The term and its history. In: MGG Online , November 2016 ( Music in the past and present , 1995)

- ↑ Adrianna Hlukhovych: "... like a dark jump through a light cup ..." Rainer Maria Rilke's Poetics of the Blind. Ukrainian trail. Königshausen & Neumann, Würzburg 2007, p. 53

- ↑ Natalie Kononenko: Widows and Sons: Heroism in Ukrainian Epic. In: Harvard Ukrainian Studies , Volume 14, No. 3/4, December 1990, pp. 388–414, here p. 407

- ↑ Sofia Hrytsa: Ukraine. II: Traditional music. 4. Epics. (i) Dumy. In: Grove Music Online , 2001

- ^ William Noll, 2000, p. 813

- ↑ Duma. In: Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- ↑ Ivan L. Rudnytsky: A Study of Cossack History. In: Slavic Review , Volume 31, No. 4, December 1972, pp. 870-875, here pp. 872f

- ^ Jan Ling: A History of European Folk Music. University of Rochester Press, Rochester 1997, pp. 85f

- ↑ Христу на хресті - To Christ on the cross. Ukrainian song - Володимир Кушпет. Youtube Video ("Christ on the Cross", Volodymir Kuschpet: Singing and kobsa )

- ↑ William Noll, 2000, pp. 813f

- ↑ Melissa Bialecki: “They Believe the Dawn will come”: Deploying Musical Narratives of Internal Others in Soviet and Post-Soviet Ukraine . (Master's thesis) Graduate College of Bowling Green State University , Ohio 2017, pp. 14-16

- ↑ Sanylo Husar Struk: Kobzar. In: Internet Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- ^ William Noll, 1993, p. 47

- ↑ Natalie O. Kononenko, 1998, p. 48

- ^ William Noll, 1993, p. 49

- ^ William Noll, 1993, pp. 50f, 64

- ^ Ulrich Morgenstern: Imagining Social Space and History in European Folk Music Revivals and Volksmusikpflege. The Politics of Instrumentation. In: Ardian Ahmedaja (Ed.): European Voices III. The Instrumentation and Instrumentalization of Sound. Local Multipart Music Practices in Europe. Böhlau, Vienna 2017, pp. 263–292, here p. 276

- ↑ Bert Rebhandl: We see each other during the riot . Frankfurter Allgemeine, July 23, 2014