Military history of Australia during World War II

Australia has already appeared on September 3, 1939 two days after Germany with the invasion of Poland, the Second World War had begun, on the part of the Allies in the war one by the National Socialist German Reich declared war. By the end of the war in 1945, nearly one million Australians were serving in the Australian armed forces , whose units were mainly deployed in mainland Europe, during the African campaign and in the command area of the Southwest Pacific Area . In addition, there were external attacks on the country for the first time since the decolonization of Australia. During the war, the Australian armed forces recorded 27,073 dead and 23,477 wounded.

In particular, Australia waged two wars between 1939 and 1945 - one against the German Empire, Italy and its allies in Europe as part of the British Commonwealth, and one on the side of the United Kingdom , the United States and other allies against Japan and its allies in the Pacific ( Pacific War : July 1937 to September 1945). Despite the withdrawal of most of the Australian forces from the Mediterranean area after the outbreak of the Pacific War, the Royal Australian Air Force participated intensively in the Allied air war against the German Empire . Between 1942 and early 1944, the Australian armed forces played a key role in the Pacific, where they provided the largest Allied troop contingent at that time. From mid-1944 they fought mainly on the side fronts; they carried out ongoing offensive operations against the Japanese troops until the end of the war .

The Second World War brought about major changes in the country's foreign policy, military and economy. The war accelerated industrialization, anchored a larger peace army in Australian society and began a foreign policy shift from a strong focus on relations with the United Kingdom to the United States. As a long-term consequence, the war also resulted in a more diverse and cosmopolitan Australian society.

Outbreak of war

In the 1930s, Australia suffered badly from the Great Depression . The Great Depression in the US also affected Australia, which traded overseas with the US and Canada. As a result of the crisis, there were cuts in the defense budget, which led to the decline in the size and operational efficiency of the Australian armed forces in the 1930s. In the 1930s, Australia followed the British line towards the German Reich and the Nazi regime : it initially supported the appeasement policy (Chamberlain) and in 1939 was one of the states that guaranteed Poland's independence.

Australia declared war on the German Reich on September 3, 1939. It was a reaction to the declaration of war by the United Kingdom, which, after an ultimatum to the German Reich to withdraw from Poland, had declared war on it. Unlike in Canada and South Africa, there was no parliamentary debate on the declaration of war in Australia. Considering itself at war , as Prime Minister Robert Menzies put it, since Britain was at war, the Australian government asked the London government to tell Germany that Australia was an ally of the United Kingdom. Australia's support for the war effort was largely based on the fact that its foreign policy interests were closely linked to those of the UK and that a defeat in Europe would destroy the system of imperial defense of the Empire's territories . In Australia, this system was considered to be absolutely necessary in the event of a war with the increasingly aggressive international Japanese Empire in order to be able to defend its own territory. These official government positions received broad support among the population; there was no general euphoria about the war. As early as 1915 (see ANZAC Day ), the Australian public had known how grueling the war could be.

In 1939 the Australian armed forces were even less prepared for conflict than when the First World War broke out in August 1914. Of the three branches of the armed forces, the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) was relatively best prepared; but she only had two heavy cruisers , four light cruisers , two sloops , five obsolete destroyers and a number of smaller auxiliary vessels. The Australian Army had a standing army of just 3,000 soldiers and 80,000 part-time militias who had volunteered for training in the Citizen Military Forces (CMF). The Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) was the weakest in numbers; only a few of its 246 aircraft were considered modern. Immediately after the outbreak of war, the Australian government began expanding its armed forces, placed some flight crews and units of the RAAF under British control and sent them to Europe; However, it initially refused to set up an expeditionary force and send it overseas, since it considered the danger of Japanese entry into the war on the German side to be realistic.

The first shot of the war on the Australian side was fired a few hours after the start of the war from a naval cannon at Fort Queenscliff in Melbourne . It was a warning shot against an Australian ship that tried to leave the port without the necessary permit. On October 10, 1939, a Short Sunderland flew No. 10 Squadron (10th Squadron) the first mission with enemy contact in a mission towards Tunisia .

On September 15, 1939, Menzies announced the establishment of the Second Australian Imperial Force (AIF). This was designed as an expeditionary force; it initially consisted of the 6th Division and some support units and had over 20,000 men. The AIF was institutionally separated from the CMF, as it was only allowed to be used in Australia itself and its outlying areas (analogous to Home Guard ). It was therefore completely reorganized instead of being formed from existing units of the CMF. On November 15, Menzies announced the reintroduction of compulsory military service for the purpose of homeland security on January 1, 1940. Recruiting for the AIF was slow at first, but increased noticeably, so that by March 1940, every sixth male Australian of military age had registered. The fall of France again led to a sharp rise in the number of volunteers. The motivation of the men to sign up for the AIF was varied, but most felt a kind of duty to defend Australia and the Empire. All three branches of the armed forces introduced restrictions in early 1940 that did not prohibit the service of Australians “essentially of European descent”. While the RAN and the Australian Army strictly adhered to these regulations, the RAAF continued to offer Australians of non-European descent in small numbers the opportunity to enter their service.

The main AIF formations were established between 1939 and 1941. The formation of the 6th Division took place in October and November 1939. After the British had assured the Australian government that Japan was not an acute threat, the division was shipped to the Middle East in early 1940, where it was to complete its training and receive modern equipment. The plans stipulated that the division would then be transported to France and placed under the British Expeditionary Force . The rapid fall of France in the western campaign prevented this, as the division was not yet completely ready to fight. Three further divisions (the 7th , 8th and 9th Divisions ) were set up in the first half of 1940 as well as the headquarters of the I Corps and various support units. All divisions and most support units were relocated overseas in the course of 1940 and 1941. At the beginning of 1941 the 1st Armored Division ( Panzerdivision ) was set up for service in the AIF; this division never left Australia.

Original plans to move the entire RAAF overseas were soon abandoned in order to concentrate the armed forces' forces on training aircrews to support the massive increase in air forces in the Commonwealth of Nations. In late 1939, Australia and other Dominions drafted the Empire Air Training Scheme (EATS) to train the largest possible number of personnel to serve in the Royal Air Force (RAF) and other Commonwealth air forces. Almost 28,000 Australians had completed the EATS training in Australia, Canada and Southern Rhodesia by the end of the war. Many of the men trained in this way served in specially newly formed squadrons, but most served in the RAF or other Commonwealth air forces. The squadrons set up in the course of the EATS were not under the control of the RAAF and were mixed nationally. The Australian government had no control over where EATS trained soldiers were deployed; many Australian historians see this as a factor which hindered the development of an independent defense readiness for Australia. Nine percent of all RAF crews in the European and North African theater of war were Australian flight crews trained in the EATS.

North Africa, the Mediterranean and the Middle East

In the early years of the war, Australia's military strategy was closely aligned with that of the United Kingdom. In line with this strategy, most of Australia's overseas deployments in 1940 and 1941 were to the Middle East and North Africa, where they formed the core of the Commonwealth of Nations at the time. The three AIF divisions sent to the region, as well as the RAN and RAAF units there, were deployed intensively.

North africa

The RAN was the first Australian armed force to be deployed in the Mediterranean region. At the time Italy entered the war on the German side on May 10, 1940, the cruiser HMAS Sydney and five obsolete destroyers were with the British Mediterranean Fleet in Alexandria . During the first days of the Battle of the Mediterranean, the Sydney sank an Italian destroyer and the obsolete Voyager a submarine. The battle in the Mediterranean was characterized by a high operating speed in its early phase, and on July 19, the Sydney together with a British destroyer squadron put the Italian light cruisers RN Bartolomeo Colleoni and RN Giovanni delle Bande Nere in the sea battle at Cape Spada . During the battle, the Bartolomeo Colleoni was sunk. The Australian ships remained at sea most of the remainder of 1940 before HMAS Perth replaced her sister ship Sydney in February 1941 .

The Australian Army saw its first use as part of the successful Allied Operation Compass in North Africa, which lasted from December 1940 to February 1941. The 6th Division replaced the 4th Indian Division on December 14th . Still without complete equipment, but fully trained, the division received the order to capture the Italian fortifications which the British 7th Armored Division had bypassed.

The 6th Division first became involved in fighting on January 3, 1941 at Bardia . Despite a strong Italian occupation in the city, the Australian infantry quickly managed to break through the defensive lines with British artillery and tank support. The bulk of the Italian troops, around 40,000 men, capitulated on January 5th. On the further advance, the division attacked the Tobruk fortress on January 21st, which was stormed the following day. 25,000 Italian soldiers were taken prisoner. After advancing further along the coast of the Kyrenaica , the Australians captured Benghazi on February 4th . Later that month the division was withdrawn from Africa to fight in Greece. Replacement was provided by the 9th Division, which had not yet been involved in combat and carried out occupation duties in the Cyrenaica.

In the last week of March 1941, a counter-offensive by the armed forces of the Axis powers, which was under German leadership. The allied units quickly retreated from the offensive, which led to a general retreat into Egypt. The 9th Division reared the retreat and received orders on April 6 to hold the strategically important Tobruk, which would be cut off from its own land lines, against the enemy for at least two months. During the siege of Tobruk , the Australians reinforced by the 18th Brigade , together with other Allied troops, fended off repeated attacks by the German-Italian attackers. The Mediterranean Fleet supplied the trapped people with supplies from the seaside, and the old Australian destroyers repeatedly ran into the port of the city, which was under fire. The HMAS Waterhen and the HMAS Parramatta were lost in such operations. At the request of the Australian government, most of the 9th Division was withdrawn from the city in September and October and replaced by the British 70th Infantry Division . Attacks on the convoy intended for their evacuation forced the 2 / 13th Battalion (2nd Company, 13th Battalion) to remain in the city until the siege was lifted at the end of November. During the fighting, the Australian units recorded losses of 3,009 men, including 832 dead and 941 prisoners of war.

Two Australian squadrons, the No. 3 Squadron and the No. 450 Squadron, actively participated in the fighting in North Africa. They were subordinate to the British No. 239 Wing (239th Squadron) and were equipped with Curtiss P-40 fighter aircraft. The squadron in turn was organizationally subordinate to the Desert Air Force (desert air force). What was special about the two squadrons at that time was that the ground crew consisted mainly of Australians, while in other formations of the RAAF mostly only the pilots were Australians and the ground crew were British. Individual Australians also fought in other British air units.

Greece, Crete and Lebanon

In the spring of 1941, the 6th Division and I Corps took part in the Allied efforts to defend Greece against the Axis Powers . The Corps Commander, Lieutenant General (Lieutenant General) Thomas Blamey and Prime Minister Menzies appreciated the operation, both a risky, said an Australian contribution to but after the British government had informed them of their plans, which understated the likelihood of defeat. The Allied forces relocated to Greece were numerically significantly inferior to the Germans in the region from the start, and during the defense of the country there were regular inconsistencies between the goals of the Greek and Allied forces.

Australian troops arrived in Greece in March and began to occupy defense positions in the north of the country together with British, New Zealand and Greek units. The Perth was part of the Allied escort to and from Greece and took part in this function in the Battle of Cape Matapan at the end of March. The quantitatively weaker Allied troops could not hold their positions against the German attack that began on April 6th and had to withdraw. After a series of defeats, they were evacuated from southern Greece between April 24 and May 1. Australian warships took part in the evacuation and took hundreds of soldiers on board in the Greek ports. In the course of the Greek campaign, the 6th Division lost 320 dead and 2,030 prisoners of war.

While the bulk of the 6th Division was returning to Egypt, the 19th Brigade Group and two provisional infantry battalions moved to Crete , where they formed the core of the troops sent to the island for defense. The brigade was able to defend itself for a short time from the German troops landing on Crete from May 20 , before it had to withdraw. After losing several airfields that were considered key tactical positions, the Allies evacuated Crete. About 3,000 Australian soldiers could no longer be evacuated and were taken prisoner of war. Due to the meanwhile serious losses, the 6th Division needed extensive reinforcements after the failed Greece expedition. The Perth and the new destroyers HMAS Napier and HMAS Nizam took part in the sea operations around Crete that took place during the battle. The Perth took soldiers on board during the evacuation itself.

The defeat in Greece led to a government crisis in Australia. Prime Minister Menzies was criticized for a long stay in England in early 1941 and blamed for the heavy losses in Greece. Many members of his own United Australia Party (UAP) denied him the ability to effectively steer the Australian war effort in this regard. Menzies resigned on August 26, as he saw no support for himself within his party either, and was succeeded in his office by Arthur Fadden of the Country Party , the coalition partner of the UAP. Fadden's government fell on October 3 of the same year, after which John Curtin of the Australian Labor Party became the new Prime Minister.

The 7th Division and the 17th Brigade of the 6th Division formed the core of the Allied ground forces in the Syrian-Lebanese campaign that began in June 1941 , in which they forcibly tore the area from the control of the French Vichy regime . The RAAF also supported the RAF during the campaign. Both air forces flew extensive close air support for the ground forces. From June 8th, Australian troops entered Lebanon from the south and advanced north along the coast and in the Litani valley . Contrary to expectations, the Vichy troops put up stubborn resistance and holed up in the mountainous terrain. After the Allied offensive stalled, reinforcements were sent to the front and I Corps headquarters took command of operations on June 18. As a result of the reinforcements, the Allies finally succeeded in breaking through and overcoming the Vichy-French forces. On July 12th, the 7th Division marched into Beirut without a fight, before an armistice was concluded the following day and the Vichy French troops surrendered.

El-Alamein

In the second half of 1941 the troops under the I Corps were concentrated in Syria and Lebanon in order to refresh them and prepare them for further operations in the Middle East. After the outbreak of the Pacific War, most of the Corps' troops, including the 6th and 7th Divisions, moved back to Australia, which was threatened by the Japanese advance. The Australian government agreed to the temporary stay of the 9th Division in the Middle East, as the United States guaranteed the stationing of further own troops in Australia and the United Kingdom in return wanted to support the RAAF in the expansion to 73 squadrons. Since the government did not assume that the 9th Division would be used on a larger scale in further fighting, it sent no further troop reinforcements overseas. While the RAN withdrew all of its ships from the Mediterranean, most of the RAAF units remained in the region.

In June 1942, four Australian N-class destroyers were moved from the Indian Ocean to the Mediterranean to take part in Operation Vigorous . The aim was to call at besieged Malta from Egypt and Palestine in order to deliver supplies. The operation failed and HMAS Nestor had to be sunk by its own forces on June 16 after being hit by Italian bombs the day before. The three remaining destroyers returned to the Indian Ocean after the operation.

In mid-1942, the Axis powers succeeded in defeating the Allies in Libya and advancing into northwestern Egypt. In mid-June, the British Eighth Army took up defense positions at the railroad station of el-Alamein , 100 kilometers from Alexandria. The 9th Division was brought up to the front to reinforce these positions. Advance detachments of the division arrived on July 6 at el-Alamein and commanded to the northern section of the defense line. The division played a crucial role in repelling the enemy attack in the first battle of el-Alamein , but suffered heavy losses, including an entire company that surrendered to the Axis powers on July 27. The division remained in their positions after the battle and made only occasional advances in support of the Battle of Alam Halfa .

In October, the RAAF division and squadrons stationed in the region took part in the second battle of el-Alamein . The 9th Division fought in some of the most intense skirmishes in the battle and captured so many enemy forces by advancing along the coast that the 2nd New Zealand Division managed to break the thinned lines on the night of November 1st to break through the Axis powers. Due to the heavy losses suffered during the battle, the 9th Division was not used in pursuit of the retreating troops. During the battle, the Australian government asked the Allied High Command to relocate the division back to Australia, as it was unable to continuously supply it with sufficient supplies over such a long distance. The request was approved at the end of November, and in January 1943 the division left Egypt for Australia, completing the AIF's operations in North Africa.

Tunisia, Sicily and mainland Italy

After the withdrawal of the main Australian combat units, several RAAF units and several hundred Australians involved in other Commonwealth units remained in action in the Mediterranean until the end of the war. Some RAAF squadrons supported the advance of the Eighth Army through Libya and during the Tunisian campaign . The destroyers HMAS Quiberon and HMAS Quickmatch also took part in the Allied landings in North Africa in November 1942.

Australia only played a small role in the Italian campaign . The RAN was again present in the Mediterranean between May and November 1943, when eight Bathurst- class corvettes were detached from the British Eastern Fleet to protect the invasion fleet off Sicily . Before being relocated back to Eastern Fleet, the corvettes were still used for convoy protection in the western Mediterranean. The No. 239 Wing and four other squadrons also supported the fighting in Sicily and, in the final phase of the battle, partly already moved to airfields on the island that had been captured. The No. 239 Wing then supported the September invasion of mainland Italy and moved to the same in the middle of the month. Two Australian fighter-bomber squadrons continued to fly close air support until the end of the war and attacked enemy supply lines. The Australian No. 454 Squadron also moved to Italy in August 1944 and hundreds of Australians were also deployed in units of the RAF until the end of the war in Italy.

Two RAAF squadrons supported the Allied landing in southern France in August 1944 . Between the end of August and the beginning of September the Supermarine Spitfires equipped No. 451 Squadron to mainland France. After the immediate invasion was over, the squadron, like the Vickers Wellingtons equipped No. 458 Squadron to Italy. The Jagdstaffel moved to Great Britain in December. The No. 459 Squadron remained stationed in the eastern Mediterranean until a few months before the end of the war and attacked German targets in Greece and the Aegean Sea . 150 other Australians fought in the Balkan Air Force , which supplied partisans in the Balkans with supplies and dropped agents over the area. During the Warsaw Uprising in 1944, she tried unsuccessfully to supply the Polish Home Army with supplies from the air.

Great Britain and Western Europe

While most Australians fought on the Western Front in France during the First World War , comparatively few Australians were deployed in Europe during the Second World War . The RAAF, including thousands of Australians under the command of the RAF, played a major role in the strategic bombing war against the German Reich and in the defense of the Allied shipping in the Atlantic. The other branches of the armed forces were only involved in the fighting to a lesser extent. Two Australian Army brigades were briefly stationed in Great Britain in late 1940, and some RAN ships were serving in the Atlantic.

Defense of Great Britain

Australians took part in the war in defending Britain against attack. More than a hundred of them were used by the RAF during the Battle of Britain , over 30 of them as fighter pilots. Two AIF brigades, the 18th and the 25th Brigade, were stationed in Great Britain between June 1940 and January 1941 and were part of the mobile reserves in the event of a German invasion . An Australian Army forestry group was stationed in Great Britain between 1940 and 1943. Several Australian fighter squadrons were also set up on site in 1941 and 1942 to intercept German air raids and Fi 103s approaching from mid-1944 .

The RAAF and the RAN took part in the Battle of the Atlantic . At the outbreak of war for the purpose of equipping with Short Sunderland flying boats in Great Britain, No. 10 Squadron stayed there through the war and was incorporated into the RAF Coastal Command . In April 1942, the No. 461 Squadron to her. Together, the two squadrons flew air raid protection for Allied convoys and sank a total of 12 submarines. Also in April 1942, the no., Specializing in light bombers and fighting ship targets, moved. 455 Squadron to Great Britain and became part of the RAF Coastal Command. In September of that year, she moved to the Soviet Union for a short time in order to protect convoy PQ 18 from there . In addition to the RAAF, the RAN used several cruisers and destroyers in escort service and provided personnel for ships of the Royal Navy.

Air war over Europe

The RAAF's involvement in the strategic bombing war over Europe was Australia's greatest contribution to the overthrow of Nazi Germany. Between 1940 and the end of the war, around 13,000 Australians served in the formations of the RAF Bomber Command (RAF Bomber Command). More precisely, this participation is to be credited to more individual Australians than to the Australian state, as most of them served in British units and the Australian bomber squadrons were subordinate to the RAF.

The majority of the aircraft crews serving in the RAF Bomber Command had been trained within the framework of the EATS. They were often assigned to different squadrons as needed, where failures had to be replaced, as a result of which they often served in multinational crews. In the course of the war, five Australian bomber squadrons were put together within the RAF Bomber Command, in which the proportion of Australians in the personnel grew increasingly. The No. 464 Squadron was originally formed as part of the RAF Bomber Command, but in June 1943 it was assigned to the RAF Second Tactical Air Force , under whose command it continued to attack targets on mainland Europe. Unlike Canada, which had its heavy bomber squadrons in its own No. 6 Group RCAF bundled, the Australian squadrons were part of the RAF Bomber Command until the end of the war, which minimized the influence of the Australian government on their operations.

During the raids of the RAF Bomber Command against German cities and over France, Australians were involved in all major operations and suffered heavy losses. During the missions in 1943 and 1944, the Australian squadrons often made up about 10 percent of the machines used. In total, 6 percent of the bomb load dropped by Australian squadrons was transported over the target during the war. The Australian aircrew had the highest casualty rate of any Australian armed forces during the war. While only 2 percent of all soldiers enrolled in the armed forces served in the Bomber Command, they caused 20 percent of all combat losses with 3,486 dead and hundreds taken prisoner.

Many Australians fought on the Western European front in 1944 and 1945 . Ten squadrons of the RAAF, several hundred deployed with the RAF and about 500 Australian sailors of the Royal Navy took part in the Allied landing in Normandy on June 6, 1944 , a total of an estimated 3,000 Australians. Between June 11 and September 1944, the No. 453 Squadron repeatedly stationed on airfields close to the front in France in order to be quickly over the target area. Other squadrons flew escorts for bomber groups or provided close air support until the end of the war. The No. 451 and No. 453 Squadron were part of the British occupation forces in Germany from September 1945 . After initial plans to station Australian troops in occupied Germany in the long term, both squadrons were disbanded in January 1946.

Pacific War

Due to the close interlinking of defense policy with that of the United Kingdom and the urgent need for troops on the European and North African front, few Australian units remained in the country itself and in the Commonwealth possessions in the Asia-Pacific region after 1940. As the likelihood of war against Japan increased in 1941, arrangements were made to strengthen Australia's defense capabilities. These turned out to be unsuitable after the outbreak of war in Asia. In December 1941, the Australian Army in the Pacific region consisted of the 8th Division, which was largely stationed in Malaya, and eight divisions in Australia, including the 1st Armored Division , which were still being set up . The RAAF had 373 aircraft, mostly obsolete training machines, and the RAN had three cruisers and two destroyers in Australian waters.

In 1942, Australia strengthened its troops with units recalled from the Middle East and the expansion of the CMF and RAAF. Large numbers of United States troops also moved to Australia before moving on to New Guinea. At the end of the year the Allies went on the offensive and systematically accelerated it through 1943. From 1944 onwards, the Australian troops no longer fought in the center of the Allied advance, but continued to carry out large-scale operations on side fronts until the end of the war.

Malaya and Singapore

Since the 1920s, Britain's Singapore strategy has dominated defense thinking in Australia. That strategy involved the establishment of a large naval base in Singapore from which a strong British fleet would respond to a Japanese military advance into the region. In line with the strategy, most of the operational Australian troops were transferred to Malaya in 1940 and 1941. In the event of war, they should defend Singapore against a land attack by the increasingly aggressive Japanese. When war broke out, the Australian troops in Malaya consisted of the 8th Division (excluding the 23rd Brigade ) under the command of Major General (Major General) Gordon Bennett , four seasons of the RAAF and eight warships. The RAAF was used before the outbreak of war on December 7, 1941, when its planes observed and were shot at by a Japanese troop convoy that later landed in Malaya. Later on, Australian troops took part in unsuccessful attempts to repel the Japanese landing forces. RAAF airmen attacked the landing sites, and the HMAS Vampire accompanied the HMS Prince of Wales and the HMS Repulse in their unsuccessful attempt to attack the Japanese landing fleet .

The 8th Division and its subordinate formations of the British Indian Army were tasked with defending Johor in southern Malaya and therefore did not come into contact with the enemy until mid-January 1942, when Japanese advance detachments marched into the province. The first major fighting occurred during the Battle of Muar , when the Japanese 25th Army took advantage of the weakness of the 45th Indian Infantry Brigade and breached their positions on the coast and bypassed the stronger units of the Commonwealth forces. Despite some minor local successes, they were able to slow down the Japanese troops to the maximum and, after heavy losses and because of the risk of being cut off from their own lines, had to retreat to Singapore on the night of January 30th to 31st.

After the withdrawal, the 8th Division was given the task of defending the northwest coast of the island. As a result of the heavy fighting in Johor, most of the division's units were only half their strength. The commander of the fortress Singapore, Lieutenant General Arthur Percival suspected the Japanese attack in the northeast and therefore stationed the almost full strength British 18th Infantry Division in this sector. Contrary to expectations, the Japanese attacked on February 8 in the area of the 8th Division, which vacated its positions after two days of fierce fighting. It was also unable to repel another landing on February 9 at Kranji and withdrew to the center of the island. After further fighting that crowded Commonwealth troops in urban Singapore, Percival and his troops surrendered on February 15. A total of 14,972 Australians were taken prisoner of war after the surrender. Some managed to escape on ships, including Major General Bennett, who after the war two committees of inquiry found guilty of unlawfully leaving his post. The loss of nearly a quarter of the soldiers stationed outside Australia and the failure of the Singapore strategy, under the aegis of which the AIFs were sent overseas, shocked the country.

Dutch East Indies and Rabaul

While the focus of Australia's defense contribution under the Singapore Strategy in Southeast Asia was in Malaya and Singapore, smaller units occupied smaller islands north of mainland Australia. The task of these troops was to protect the airfields there from enemy occupation, as land-based bombers could attack the continent from them. Smaller departments of coastal observers in the Bismarck Archipelago and on the Solomon Islands should also report on Japanese operations near the coast.

At the beginning of the Pacific War, the strategically important port of Rabaul in New Britain was held by the Lark Force , consisting of an infantry battalion, coastal artillery and a poorly equipped RAAF bomber squadron. Although the Lark Force was considered unsuitable for effective defense, there was no reinforcement until the landing of Japanese troops on January 23, 1942. In the battle for Rabaul that followed , the severely defeated Australians quickly surrendered and most of them were taken prisoners of war. There was already a massacre on February 4th when Japanese troops executed 130 prisoners. Of the remaining members of the Lark Force, only a few survived the war, as the ship with which they were to be transported to Japan was sunk by an American submarine on July 1, 1942.

AIF troops were relocated to the Dutch East Indies during the first weeks of the war . Refreshed battalions of the 23rd Brigade moved to Kupang in West Timor and the island of Ambon to defend these areas against Japanese attacks. In violation of Portuguese neutrality , an independent company occupied Dili , the capital of Portuguese Timor . Ambon fell to Japanese troops on February 3, 1942, who landed on January 30. During February, over 300 captured Australians were executed by the Japanese in waves. The troops in Kupang surrendered on February 20, in the Portuguese part of Timor , which was also occupied by the Japanese, a guerrilla war developed , as Allied troops fought their way into the jungle and resisted the conquerors until February 1943. The HMAS Voyager and HMAS Armidale were lost in September and December 1942 when they were doing support missions for the commando units in Timor.

On February 19, 1942 , 242 land and carrier-based aircraft attacked Darwin . At that time, the city's port was one of the most important allied naval ports and served as a transshipment point for sending troops and materials to the Dutch East Indies. The attack killed 251 people, mostly non-Australian seafarers, and wreaked havoc on the city's port facilities and air base .

Several Australian warships and around 3,000 army soldiers and aircraft from various RAAF squadrons participated in the unsuccessful defense of Java in March 1942. The Perth sailed in the ranks of the largest ship formation of the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (American-British-Dutch Command, ABDACOM) and took part with this in the battle in the Java Sea , in which the Allies unsuccessfully tried to intercept a Japanese troop convoy on February 27. The Perth sank on March 1 after she encountered another Japanese invasion force in the battle of the Sunda Strait, along with the American cruiser USS Houston and the Dutch destroyer HNLMS Evertsen . The sloop HMAS Yarra was sunk on March 4, while under escort, off the south coast of Java in a battle with Japanese cruisers. The Australian warships remaining in the waters around the Dutch East Indies, including the light cruiser HMAS Hobart and several corvettes, managed to retreat to safer areas. An army unit consisting of parts of the 7th Division was subordinate to the land forces of ABDACOM on Java. It was only used sporadically and surrendered on March 12 at Bandung after the Dutch units on the island began to surrender. RAAF planes entered the fighting from places in Java and Australia, and 160 ground crew from No. 1 Squadron were taken prisoner of war.

Following the conquest of the Dutch East Indies, the central Japanese carrier fleet carried out an advance into the Indian Ocean . The fleet attacked Ceylon in early April. The HMAS Vampire was lost off Trincomalee on April 12 , while escorting the carrier HMS Hermes , which was also sunk by Japanese carrier aircraft. The Australian 16th and 17th Brigades in garrison service on Ceylon did not come into enemy contact during Japanese operations.

Troop levies in Australia

The rapid loss of Singapore raised fears of a possible Japanese invasion of mainland Australia among the Australian population and government. The country and its armed forces were ill-prepared for such an invasion, as the RAAF lacked modern aircraft and the RAN was too small and unbalanced in structure to take on the Japanese Navy. The Australian Army also had many troops, but they were inexperienced and not very mobile. In response to these facts, most of the AIFs were relocated from the Mediterranean and the Australian government sought assistance from the United States. The British Prime Minister Winston Churchill tried to divert the divisions 6th and 7th , which were being relocated, to Burma , which Curtin refused. As a compromise, the 16th and 17th Brigades of the 6th Divisions disembarked on Ceylon and formed part of the island garrison. In August 1942 they were withdrawn for Australia.

The danger of an invasion led to a strong expansion of the Australian armed forces. By mid-1942, the army had ten infantry divisions, three tank divisions and several hundreds of smaller units. The RAAF and the RAN were also considerably upgraded, but their respective maximum strengths were only reached in the following years. Due to the high personnel requirements, the restrictions that excluded Australians from non-European descent from service in the armed forces were no longer applied from the end of 1941. As a result, approximately 3,000 Aborigines signed up for the service. Most of these new recruits were incorporated into existing units, but there were also segregation-based units such as the Torres Strait Light Infantry Battalion ( Torres Street Light Infantry Battalion ). Thousands not volunteered to serve for the regular service suitable Australians in support of organizations such as the Volunteer Defense Corps (volunteer defense corps) and the Volunteer Air Observer Corps (volunteer air observer corps), which differ in their organization at the British Home Guard British (Home Guard ) and the Royal Observer Corps ( Royal Observer Corps ). Since the Australian population was not large and the Australian industry was not developed enough to sustain these armed forces permanently, their strength was gradually reduced during the war after the acute threat of invasion ended and only 53 of the 73 planned squadrons of the RAAF were actually deployed.

Contrary to Australian fears, the Japanese forces never seriously planned an invasion. The Japanese General Headquarters briefly considered such an operation in February 1942, but rejected it again because, in its opinion, it was beyond Japan's military capabilities. From March 1942, the Japanese strategy instead provided for cutting off Australia from the supply lines from the United States. To this end, Port Moresby in New Guinea, the Solomon Islands , Fiji , Samoa and New Caledonia should be conquered. The Japanese plan suffered a first setback with the defeat in the Battle of the Coral Sea and was postponed indefinitely after the defeat in the Battle of Midway . Although both battles made invasion increasingly unlikely, the Australian government officially warned of its possibility until mid-1943.

The collapse of British power in the Pacific region led Australia to increasingly orient its foreign and security policy towards the United States. In February 1942, the United Kingdom and United States governments agreed that Australia should be under the strategic jurisdiction of the United States, and the ANZAC Force was established to defend the Australian continent. In March, General Douglas MacArthur reached Australia after his escape from the Philippines and took command of the Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA). All Australian armed forces in this area were henceforth subordinate to MacArthur's command, and by the end of the war MacArthur took over the role of the chief military advisor to the Australian government from the Australian chiefs of staff. The Australian General Thomas Blamey received command of the land forces in the command area, but MacArthur excluded the American forces from this. He also denied the Chief of Staff of the United States Army George C. Marshall's request to use Australians in senior positions at his headquarters. Despite these restrictions, the partnership between Curtin and MacArthur turned out to be positive for Australia, as the latter was able to enforce demands for support from the Australian government against the American government.

In the early years of the Pacific War, the United States stationed a large number of troops in Australia. The first units arrived in early 1942, and nearly a million Americans were deployed in the country during the war. In the course of 1942 and 1943, many American military bases were established in northern Australia, and it remained an important supply hub until the surrender of Japan. Despite isolated incidents between American and Australian soldiers, military relations were considered good. However, the Australian government was reluctant to allow African American units to be stationed in the country.

Fight in Papua

Japanese troops landed for the first time on March 8, 1942 at Salamaua and Lae in New Guinea to capture bases from which they could secure their nascent, important base in Rabaul. Australian guerrillas from the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles set up secret observation posts around the Japanese bridgeheads, and a commando raided the Japanese base in Salamaua on June 29 .

After the defeat in the Battle of the Coral Sea thwarted the Japanese plans to take Port Moresby by amphibious landing, the Japanese troops landed at Buna in the north of the Papua Territory . These should cross the Owen Stanley Mountains along the Kokoda Track and take Port Moresby from land. The Battle of the Kokoda Track began on July 22nd when the Japanese began their advance and encountered the ill-prepared Australian Maroubra Force. This could only delay the Japanese advance and not stop it entirely as planned. On August 26, two battalions of the 7th Division reinforced the remnants of the Maroubra Force. Even these reinforcements failed to stop the Japanese, who occupied the village of Ioribaiwa near Port Moresby on September 16. Supply shortages and the fear of an Allied landing at Buna, which would lock them up in interior New Guinea, ultimately led to the withdrawal of the Japanese. Australian troops pursued them along the Kokoda Track and trapped them in a small beachhead on the north coast in early November. The Australian operations were supported by locals who were often forcibly recruited by the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit as porters. The RAAF and USAAF also intervened extensively in the fighting, parachuting supplies and attacking Japanese troops.

In August 1942, Australian troops fended off an attack on the strategically important Milne Bay . During the Battle of the Bay, two Australian brigades called the Milne Force, together with two RAAF fighter squadrons, smashed a numerically weaker Japanese marine infantry unit . The battle was the first of the war in which Allied forces managed to defeat a larger Japanese unit in a land battle.

At the end of November 1942, American and Australian units attacked the Japanese bridgehead at Buna-Gona . The fighting dragged on until January 1943 before the Allies were victorious. Their troops consisted of the worn-out Australian 7th Division and the inexperienced and poorly equipped American 32nd Infantry Division and had little artillery and insufficient supplies. A lack of heavy weapons and the focus on rapid advance set by MacArthur and Blamey, the Allied tactic consisted of repeated infantry attacks on Japanese fortified positions. Because these attacks were poorly prepared, they caused heavy losses and delayed fighting until January 22nd. Most of the Australians captured during the fighting in the Papua Territory were executed by the Japanese. This led to a brutalization of the warfare, which led to the fact that the Australian troops no longer tried to take prisoners and executed some of them.

After the defeats in Papua and Guadalcanal , the Japanese withdrew to defensive positions in the territory of New Guinea . To secure their important bases in Lae and Salamaua, they tried to conquer the town of Wau in January 1943 . Rapidly flown in reinforcements were able to repel the attack after heavy fighting on the edge of the settlement. On February 4, a general Japanese coastal retreat began. A convoy to reinforce the troops in Lae was broken up by RAAF and USAAF aircraft during the battle in the Bismarck Sea , killing around 3,000 men.

The fighting in Papua led to significant reforms in the composition of the Australian Army . During operations, the restriction on not deploying CMF members outside Australia severely hampered tactical planning and created tension between the AIF leadership and the CMF. At the end of 1942 and beginning of 1943, Curtin succeeded in overcoming internal party opposition to the expansion of the deployment area of conscripts, and in January 1943 the Defense (Citizen Military Forces) Act 1943 was passed, which expanded this deployment radius to almost the entire Southwest Pacific. Despite legislative approval now given, the 11th Brigade served as the only CMF formation outside of Australia when it fought as part of the Merauke Force in the Dutch East Indies in 1943 and 1944 .

Attacks on Australian shipping

The Japanese efforts to secure New Guinea went hand in hand with an intensified submarine offensive against the Allied shipping routes between America and Australia and between Australia and New Guinea. As early as 1940 and 1941, a total of five German auxiliary cruisers had disrupted shipping traffic in Australian waters. Although they could not successfully disrupt Australian shipping, the auxiliary cruiser Kormoran managed to sink the light cruiser HMAS Sydney with its entire crew of 641 men off the coast of Western Australia in November 1941 .

After the first defeats of the Japanese capital ship units, the Japanese navy concentrated on using submarines to disrupt the supply routes off the east coast of Australia. These missions began with a failed attack with micro-submarines on Sydney Harbor on May 31, 1942. Subsequently, Japanese submarines operated off the Australian east coast until August and were able to sink eight merchant ships. Between January and June 1943 they operated again off the Australian east coast and sank 15 ships, including the hospital ship AHS Centaur , killing 268 people. After June 1943, the Japanese withdrew their submarines to repel the allied offensive operations that had meanwhile been deployed and did not send them to Australian waters as the war continued. With U 862 , a single German submarine operated in the Pacific during the war and cruised off Australia and New Zealand in December 1944 and January 1945, sinking two ships. Then it returned to the port of the Japanese-occupied Batavia .

Significant military resources by both the Australian and other Allied forces were expended to protect shipping and ports from enemy warships. In the course of the war, RAN ships escorted more than 1,100 convoys, and the army built and manned extensive coastal fortifications around strategically important ports. In addition, many RAAF squadrons regularly flew escorts. This use of funds to protect shipping, despite its size, had no serious impact on Australian economic strength and the offensive Allied war effort.

Offensives in New Guinea

After the Japanese offensives got stuck, the allies in the SWPA began the counteroffensive in mid-1943. Australian troops played a key role in the offensive called Operation Cartwheel . General Blamey coordinated a number of successful endeavors in northeastern New Guinea that were later seen as the pinnacle of Australian operational leadership during the war.

After the successful defense of Wau, the 3rd Division began the advance on Salamaua in April 1943 . The advance on this section of the front served as a diversionary maneuver to pull Japanese troops from the actual main target of Operation Cartwheel, the town of Lae. At the end of June, American troops landed in Nassau Bay to reinforce the 3rd Division. The fighting for Salamaua dragged on despite the reinforcements until September 11th, when the Allies succeeded in driving the Japanese out of the place.

In early September, Australian-led forces carried out a pincer attack on Lae. On September 4, the 9th Division landed east of the village and advanced on it. The following day, an American infantry regiment landed at Nadzab, west of the city, and secured the airfield there, over which the 7th Division was flown. During the following advance, the 7th Division was the first to advance into the village and secured it on September 15th. Despite heavy losses, the Japanese troops involved in the fighting managed to withdraw to the north.

After securing Laes, the 9th Division was given the task of cleaning up the Huon Peninsula . The 20th Brigade landed for this purpose on September 22, 1943 at Finschhafen and secured the strategically important port of the place. In response, the Japanese began to move the 20th division overland in the direction of Finschhafen. To repel the expected attack, the 20th Brigade was reinforced by the remaining units of the 9th Division. From mid-October there was heavy fighting over the place, which the Australians won. In the second half of November they also succeeded in conquering the heavily fortified hills in the hinterland of Finschhafen . The Japanese withdrew after the renewed defeat along the coast and were pursued in fighting by the 9th Division and the 4th Brigade . Towards the end of the fighting, Australian pioneers managed to secure all the encryption manuals of the 20th Division, which it had buried on its retreat. This find represented an enormous success in the intelligence service, as it was now possible to overhear all radio traffic of the Japanese army and thus avoid positions and islands that were particularly strong on the advance.

While the 9th Division secured the coastal region of the Huon Peninsula, the 7th Division took action against enemy forces in the Finisterre Mountains . The Battle of the Finisterre Mountains began with the air landing of an Australian company on September 17th in the Markham Valley. The company drove Japanese troops out of Kaiapit and secured the airfield there, where the 21st and 25th Brigade were flown in. With aggressive patrols they then secured a larger area in difficult terrain, before the strategically important Japanese positions on the Shaggy Ridge ridge were attacked in January 1944. At the end of January, the Japanese withdrew from their positions and from all of the Finisterre Mountains after repeated RAAF air strikes. On April 21st, the Australians met American troops that had landed at Saidor in January and together with them they secured Madang on April 24th .

In parallel to the army operations in New Guinea, the RAN and RAAF carried out offensive operations in the Solomon Islands. Operations there began in August 1942 when the heavy cruisers HMAS Australia and HMAS Canberra supported the American landing on Guadalcanal . On the night following the landing, the Canberra was lost to enemy fire in the battle of Savo Island , whereupon the RAN no longer intervened in the further course of the battle for Guadalcanal. During 1943 and 1944, RAAF aircraft repeatedly supported American landings and one of their long-range reconnaissance units took part in the Battle of Arawe . The cruisers Australia and Shropshire and the destroyers Arunta and Warramunga provided fire support to the American landing forces during the battles for Cape Gloucester and the Admiralty Islands in late 1943 and early 1944. The amphibious transport ship Westralia was also used for the first time on the landings near Cape Gloucester .

Air War over Northern Australia

A Japanese air raid on Darwin in February 1942 marked the beginning of the aerial warfare over northern Australia and the Japanese-occupied Dutch East Indies. The Japanese attack led to the hasty relocation of fighter squadrons to the region and the reinforcement of the Northern Territory Force of the Australian Army in order to be able to fend off a possible invasion. Attacks by Australian air forces on Japanese positions in the Dutch East Indies led to repeated air strikes against Darwin and the airfields there in 1942 and 1943, which, however, rarely caused serious damage. American, Australian and British hunting associations were available to repel the attacks. The increasing improvement in defense mechanisms around Darwin caused increasing losses among the Japanese. During the same period, the Japanese forces carried out a few unsuccessful air strikes in Queensland and Western Australia.

While the Japanese air raids on Australia ceased in late 1943, the Allies carried out operations from their bases there until the end of the war. At the end of 1942 they attacked enemy positions in Timor in particular to support the Australian guerrilla war there. From the beginning of 1943, heavy American bombers flew against targets in the eastern Dutch East Indies. From June 1943, American, Australian and Dutch units intensified this air war in order to persuade the Japanese to withdraw troops from the Solomon Islands and New Guinea. These attacks continued until the end of the war, with Australian bomber squadrons equipped with Consolidated B-24 replacing the American ones from the end of 1944 . Consolidated PBY flying boats laid sea mines on many important shipping routes in Southeast Asia from 1944 onwards .

Advance on the Philippines

In the course of 1944, the importance of the Australian armed forces in the Southwest Pacific declined. In the second half of 1943 the Australian government, in agreement with MacArthur, decided to reduce the strength of the armed forces in order to free up human resources for the war industry. This represented an important factor in the supply of the American and British forces in the Pacific region. Australia changed the focus of its war efforts with it from a strong own contribution to the supply of its allies in the war against Japan with food and other strategic supplies. As a consequence of this decision, the offensive component of the Australian Army was set at six infantry divisions (three from the AIF and three from the CMF) and two tank brigades. The size of the RAAF was capped with 53 active squadrons, and the RAN was only reinforced by the ships that were already under construction and planning at the time. In early 1944, all but two army divisions were relocated to the Atherton Tablelands in northern Queensland to refresh and train them. In the further course of the year, several battalions of local men and Australian officers were set up in New Guinea and combined in November in the Pacific Islands Regiment . They were supposed to replace disbanded Australian battalions during the same period and came to New Guinea for repeated combat missions until the end of the war.

After the reconquest of most of Australian New Guinea, RAAF and RAN units took part in the American-led Battle of Western New Guinea . The aim was to secure the area and use it as a stepping stone to the Philippines . Australian warships and both aviation and engineering units of the No. 10 Operational Group RAAF took part in the conquest of Hollandia , Biak , Numfor and Morotai . After Western New Guinea had been secured, the renaming of No. 10 Operational Group in No. 1 Tactical Air Force (1st Tactical Air Fleet; 1TAF), which henceforth covered the flank of the Allied advance by attacking Japanese positions in the Dutch East Indies. Disproportionately high losses in these missions, which were perceived as strategically unimportant, led to a collapse in troop morale and the so-called Morotai mutiny in April 1945.

Parts of RAAF and RAN also took part in the retaking of the Philippines. The transport ships HMAS Kanimbla , HMAS Manoora and HMAS Westralia as well as a number of smaller ships took part in the American landing in the Gulf of Leyte on October 20, 1944. Some Australian historians take the view that the HMAS Australia, also cruising in the region , was the first ship to be attacked by Kamikaze pilots of the Shimpū Tokkōtai on October 21 . However, the American historian Samuel Eliot Morison questions this. The Australia took part with other Australian ships in the sea and air battle in the Gulf of Leyte , with the Arunta and Shropshire involved in a gun battle with Japanese ships in Surigao Strait on October 25. In January 1945 ships of the RAN covered the Allied landing in the Gulf of Lingayen , where the Australia was hit by a total of five kamikaze and lost 44 men of her crew. The hits damaged her so badly that she had to withdraw and call into a shipyard for repair work. US Navy supply convoys were regularly escorted by Australian ships during the fighting in the Philippines. A RAAF engineer and communications unit landed in the Philippines to support American troops, and 1TAF repeatedly attacked targets in the south of the archipelago.

On several occasions, the Australian government offered MacArthur to send the I Corps to Leyte and Luzon in support of the fighting, to which MacArthur did not respond. The relative inactivity of the Australian Army in 1944 sparked debate among the Australian public as to whether the AIF should be demobilized if it was not needed for offensive operations. The public discussions led the government to search intensively for new fields of operation for the army.

Enemy clearance in New Guinea and the Solomon Islands

The Australian government made twelve brigades available at the end of 1944 to relieve six US Army divisions stationed for defense purposes in Bougainville , New Britain and in the Aitape-Wewak area of New Guinea. The Australian units began to dismantle the static defensive lines established by the American divisions and to carry out new offensive operations against the remaining Japanese forces. The meaningfulness of these fights was already then and is still controversially discussed today (as of 2013). The Australian government ordered it for mainly political reasons. She assumed that an ongoing Australian contribution to the fight would increase the influence on the peace conferences that followed the war and in general in the region. Critics accuse her of having acted unnecessarily and thrown away the lives of Australian soldiers, as the corresponding Japanese units were already isolated and could no longer influence the outcome of the war.

The 5th Division replaced the American 40th Infantry Division in New Britain in October and November and continued their battles to secure Allied bases and to push the Japanese back on Rabaul. At the end of November, their troops established bases close to the Japanese defense lines and, with the support of the Allied Intelligence Bureau, began aggressive attacks against them. At the beginning of January 1945, amphibious landings in two bays at the base of the Gazelle Peninsula and the breaking up of the weak Japanese crews in the area followed. By April the Japanese were pushed back into fortified positions on the peninsula. The 5th Division had losses in the form of 53 dead and 140 wounded in the fighting. After the end of the war, it emerged that the Japanese forces on the island were 93,000 strong, several times the 38,000 soldiers expected by the Allied intelligence.

The II Corps took over fighting on Bougainville from the American XIV Corps , which it replaced between October and December 1944. The corps consisted of the 3rd Division, the 11th Brigade and the Fiji Infantry Regiment on Bougainville and the 23rd Brigade, which occupied smaller neighboring islands. Air support came from the RAAF, the Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) and air units of the United States Marine Corps . While the Americans had previously set up defensive positions on Bougainville, the Australians, like in New Britain, took the offensive after taking over the area in order to completely crush the Japanese armed forces on the island. The main objective was the Japanese base near Buin in the south of the island, and from May 1945 the fighting in the north and in the center was largely stopped. The fighting continued until the end of the war, large Japanese units were able to hold out in Buin and in the north until then.

The 6th Division was given the task of crushing the Japanese 18th Army in New Guinea , which was the last large enemy force in Australian New Guinea. The division, reinforced by units of the CMF, arrived in Aitape from October 1944 . In addition, some RAAF squadrons and individual RAN ships supported the fighting. In late 1944, an Australian pincer attack began on Wewak . The 17th Brigade advanced through the central Torricelli Mountains while the rest of the division advanced on the coast. Despite heavy losses due to lack of food, illness and previous battles, the 18th Army put up stubborn resistance. Bad weather and supply difficulties additionally hindered the division's progress. The coastal area could only be secured in May 1945 after a small force was landed east of Wewak and occupied the place on May 10th. By the end of the war, the Eighteenth Army had been pushed back into a small area inland and suffered from ongoing Australian attacks. Before Japan surrendered, the fighting cost 442 lives on the Australian side. About 9,000 Japanese fell while 269 were captured.

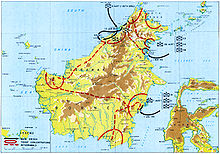

Battle for Borneo

The Battle of Borneo in 1945 was the last large-scale Allied offensive action in the SWPA. The I Corps under Lieutenant General Leslie Morshead attacked the Japanese occupiers of the island in a series of amphibious landings between May 1 and July 21 . The United States Seventh Fleet under Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid , the 1TAF, and the American Thirteenth Air Force also played a significant role in the battle. The aim of the battle was to secure the island's oil fields as well as Brunei Bay and to use the island as a base for the Allied landing in Japan and the landing in Malaya, both of which were to call at later that year. The Australian government rejected MacArthur's proposal to include the island of Java in operations on Borneo and did not make the 6th Division available, which is why the plan was not carried out.

The battle began on May 1st with the landing of the 26th Brigade on Tarakan, off the east coast of Borneo. The goal was the island's airfield to support operations against Brunei and Balikpapan from there . Contrary to the original plans, heavy fighting broke out on the island , which lasted until June 19. The airfield could only be put into operation on June 28th, which is why this operation was rated as a failure.

The second phase of the battle began on June 10 with several parallel attacks by the 9th Division against the northwest of the island of Labuan and the coast of Brunei. While Brunei was quickly occupied, Japanese troops on Labuan resisted for more than a week. After securing Brunei, the 24th Brigade was landed in northern Borneo while the 20th Brigade advanced along the coast south of Brunei. Both brigades advanced rapidly against weak resistance and conquered most of Northwest Borneo by the end of the war. The Australian troops were supported in the fighting by local guerrilla fighters, whose units were trained by Australian special forces.

The third and final phase of the battle was the capture of Balikpapan on the island's central east coast. It was carried out on MacArthur's orders and against the wishes of Blamey, who considered it unnecessary. After a preparatory twenty-day bombing from sea and from the air, the 7th Division landed near the place on July 1st. The fighting for the city and its surroundings dragged on until July 21 and was the last major land operation of the Western Allies in World War II. The operations on Borneo were criticized as senseless waste of life during the war and in the years that followed. At the same time, however, they achieved most of their goals, the most important of which were the isolation of enemy troops still in the Dutch East Indies, the securing of important oil production facilities and the liberation of Allied prisoners of war who were in extremely poor condition.

During the fighting, there was a change in the political leadership of Australia. Prime Minister Curtin suffered a heart attack in November 1944 and was first represented by Deputy Prime Minister Frank Forde until January 22, 1945 . After being hospitalized again in April 1945, Treasury Secretary Ben Chifley took over the role of ruling prime minister as Forde was at the San Francisco Conference . Curtin died on July 5th, after which Forde was sworn in as Prime Minister. On July 13th, he lost his position again because he had no support from his party and so lost a vote of no confidence. Chifley then took up his post.

Intelligence and special forces

Australia developed numerically strong intelligence services during the war. Before the outbreak of war there had been almost no reconnaissance activities in the armed forces, which meant that they relied primarily on information from British services. Several small communications reconnaissance units were set up during 1939 and 1940 and had some success in intercepting and decoding Japanese radio communications prior to the outbreak of war in the Pacific.

General MacArthur began large-scale reconnaissance services shortly after arriving in Australia. On April 15, 1942, the American-Australian Central Bureau was set up in Melbourne. His headquarters were moved to Brisbane in July of that year and to Manila in May 1945 . Australians made up half of the more than 4,000-strong organization in 1945. The Australian Army and RAAF had the largest radio reconnaissance capabilities in the SWPA, and the number of these units was consistently increased at a large rate between 1942 and 1945. The Central Bureau was able to crack a number of Japanese radio codes and, through this and extensive radio direction finding, helped to analyze the movements of Japanese troops.

Australian special forces played some role during the Pacific War. After the outbreak of war, command companies were sent to Timor, the Solomon Islands, the Bismarck Islands and New Caledonia. While the 1st Independent Company in the Solomon Islands was quickly smashed in early 1942, two other companies were able to involve the Japanese who had landed on Timor in a guerrilla war with many losses between February 1942 and February 1943 before they were evacuated to Australia. The commandos continued to play a role in New Guinea, New Britain, Bougainville and Borneo, where they scouted the enemy, led offensive operations and covered the flanks of regular troops.

Australia also set up a small force specializing in behind enemy line reconnaissance and sabotage. Most of these formations were subordinate to the Allied Intelligence Bureau (AIB). They observed enemy coastlines or raided unsecured supply depots. In September 1943, a special unit succeeded in sinking seven ships in the port of Singapore. AIB units were often called in to support army units and took on reconnaissance and liaison missions there. In Timor and Dutch New Guinea they were under the command of the former Dutch colonial administration. In 1945, the RAAF set up its own unit to supply special commands from the air that were operating behind enemy lines.

Operations against the main Japanese islands

Australia played only a subordinate role in the Allied actions against the main Japanese islands in the last months of the war, but was preparing to participate in the planned invasion of the islands. Several Australian warships operated with the British Pacific Fleet (British Pacific Fleet, BPF) during the Battle of Okinawa , and destroyers later escorted British aircraft carriers and battleships in attacks against the main islands. Despite its distance from Japan, Australia was the main base for the BPF, which is why a number of large bases were established there.

Australia's participation in the invasion of Japan should include all three branches of the armed forces. The 10th Division was to be set up again from existing units of the AIF and become part of the British-Canadian-New Zealand Commonwealth Corps. Its structure should be identical to that of an American army corps, and it should be used in March 1946 when landing on Honshu . In addition to the ships of the RAN together with the BPF, two bomber squadrons and one transport squadron were to be relocated from Europe in order to take part in the strategic bombing war against Japan with the Tiger Force . The plans for the invasion were suspended in August 1945 after the atomic bombs were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the declaration of Japan to surrender .

General Blamey signed the Japanese document of surrender on September 2, 1945 on behalf of Australia on board the American battleship USS Missouri . Several Australian ships were present in Tokyo Bay during the ceremony . After the ceremony on board the Missouri , the commanders of remaining formations in the Pacific region surrendered to Allied troops. Australian units received these in Morotai, various places in Borneo, Timor, Wewak and Rabaul, Bougainville and Nauru.

Australians in other theaters of war

In addition to the main locations, smaller Australian units and other men and women also served in other regions, mostly within British-led Commonwealth units. Around 14,000 Australians served in the British merchant navy and sailed the world's oceans with it.

Australia played a minor role in Allied operations in the African colonies of Vichy France . End of September 1940 took the HMAS Australia in the unsuccessful attempt by British and Free French forces in part to conquer the Dakar and put this one vichyfranzösischen destroyer. The Australian government had not previously been informed of the use of the cruiser in the battle and complained about this to the British government. Three Australian destroyers took part in Operation Ironclad to conquer Madagascar in September 1942 . The HMAS Adelaide was escorting a sympathizing with the Free French governor in September 1940 to Noumea in New Caledonia and then moored outside the city. The erupting tumult led to the removal of the Vichy-loyal colonial administration and the change of New Caledonia to Free France.

Other Australian warships patrolled the Red Sea and Persian Gulf during the war . Between June and October 1940, HMAS Hobart supported the East Africa campaign and played an important role in the evacuation of Berbera . In May 1941, the Yarra supported the landing of Gurkhas near Basra during the British-Iraqi War . In August of that year, the Kanimbla and the Yarra took part in the Ango-Soviet invasion of Iran , with the Yarra sunk the Iranian Sloop Babr and the Kanimbla troops landed at Bandar Shapur. During 1942, a dozen Australian Bathurst- class corvettes escorted Allied shipping in the Persian Gulf.

While most Australians fought in the Far Eastern theater of war in the SWPA, a few hundred served in British units in Burma and India. Among them were 45 men from the 8th Division who had volunteered to train Chinese guerrillas. They were part of the British Mission 204, which was in southern China between February and September 1942. In May 1943, about 330 Australians were serving in 41 British squadrons in India, with only nine having more than ten Australians each. Many of the RAN's corvettes served in the British Eastern Fleet , which usually protected Allied shipping in the Indian Ocean.

Prisoners of war

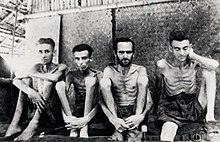

A little under 29,000 Australians became prisoners of war . Of the 21,467 captured by Japan, only about 14,000 survived the war. Most of the deaths were due to malnutrition and illness.

The under 8,000 captured by the German Reich and Italy were usually treated in accordance with the Geneva Conventions . Most of them were captured during the fighting in Greece and Crete in 1941, around 1,400 were shot down aircraft crews. Like other prisoners of the Western Allies, the Australians were interned in permanent prisoner-of-war camps in Germany and Italy. Towards the end of the war, the Germans transferred their prisoners to the interior of the Reich in order to prevent their liberation by the advancing Allies. The relocation often took place in force and death marches . After a mass flight of prisoners from the Stalag Luft III camp in March 1944, four Australian prisoners were executed. While the death rate of Australian prisoners in Germany and Italy was higher than that of World War I prisoners, it was still significantly lower than the death rate in the Japanese prisoner of war camps.

Most of the allies captured in the early months of the Pacific War suffered particularly dire conditions. They were interned in makeshift camps throughout the Pacific and transported there under the most adverse conditions . In addition to malnutrition and illness, hundreds of Australian prisoners were killed or executed by their guards. In 1942 and 1943, in addition to many other prisoners of war and forced recruited locals, around 13,000 Australians were also used to build the infamous Thailand-Burma Railway , of whom approximately 2,650 died. Many prisoners were also taken to the main Japanese islands, where they worked in mines and factories in generally poor conditions. The camps in Ambon and Borneo recorded the highest death rates. 77 percent of the prisoners on Ambon died, and of the 2,500 interned on Borneo only a few survived. Most died from overwork and the so-called Sandakan Death Marches in 1945.

The treatment by the Japanese meant that many Australians remained hostile to them even after the end of the war. The Australian authorities investigated reports of ill-treatment in their jurisdiction after the war and indicted suspected prisoners in war crimes trials.

Thousands of enemy prisoners of war were interned in Australia during the war. The total number was 25,720, of which 18,432 were Italians, 5,637 were Japanese and 1,651 were German. These prisoners lived in specially built camps and were generally treated according to the Geneva Conventions. In addition, 16,798 civilians were interned, including 8,921 so-called enemy aliens living in the country . The rest were brought to Australia from other countries. On the morning of August 5, 1944, about half of 1,104 Japanese prisoners of war interned in a camp near Cowra attempted to escape. About 400 managed to overpower the guards and break through the fences. Over the next ten days, all those who escaped were either recaptured or killed.

Home front

During the war, the Australian government significantly expanded its powers and rights to better utilize the country's industry and people for the Allied war effort. These reforms began on September 9, 1939 when the National Security Act was passed. This enabled the government to convene the population for industrial work, which affected both men and women. The rationing of food and other consumer goods first came into effect in 1940 and expanded on a large scale during 1942. The government also appealed for thrift and issued various war bonds in order to save raw materials and raise sufficient funds.

The government's economic and armaments policy to expand industry was successful, which enabled the country to be self-sufficient in many armaments sectors. In the years before the war, the government had tried through subsidies, tariffs and other measures to specifically promote areas that were important to the war effort, such as the automobile and aircraft industries, the chemical and electrical industries. The industries that were indirectly linked to the armaments industry were merged with it in 1940 and 1941 to form a war economy , which from 1942 onwards was able to meet most of the army's needs. The electrical industry, which was particularly promoted by the government, produced light radar devices and optical target systems for the artillery during the course of the war and adapted a whole range of devices to the tropical conditions in Southeast Asia. The industry also developed new weapons such as the Owen submachine gun and modified others to suit the needs of the armed forces. During the war, the country's doctors made great strides in the treatment of tropical diseases. Other developments turned out to be a failure. Development and testing of the AC-1 Sentinel tank was discontinued after it had already proven to be obsolete and unnecessary at this stage. The development of its own aircraft, namely the Commonwealth Woomera bomber and the Commonwealth Kangaroo fighter , was discontinued because no suitable engines were available. Instead of these in-house developments, American and British aircraft types were manufactured under license.

The massive increase in the armed forces led to a shortage of male workers, which is why women were increasingly called to work. The number of employed women rose from 644,000 in 1939 to 855,000 in 1944. While this represented an increase of only 5% in relation to the total female population, many already working women switched from typical "female jobs" to more "male" industrial jobs. From 1941, women could also serve in certain areas of the armed forces, and by 1944 nearly 55,000 of them took advantage of this opportunity with the Women's Royal Australian Naval Service , the Australian Women's Army Service and the Women's Auxiliary Australian Air Force . A few thousand more worked in the civilly organized Australian Women's Land Army or in volunteer services. The worsening shortage of labor led from 1944 to the reduction of the armed forces in order to free men for the war industry and the civil economy.