Pedro de Valdivia

Pedro de Valdivia (born April 17, 1497 in Castuera, Extremadura region , Spain , † December 25, 1553 in Tucapel , Chile ) was a Spanish soldier and conquistador and the first acting governor of Chile .

He came from a noble family with a long military tradition. In the Italian wars he took part in the campaign in Flanders, the Battle of Pavia (1525) and the sack of Rome (1527).

In 1536 he came to the Spanish colonies of Central and South America as a military leader. First he took part in the conquest in Venezuela and the search for the legendary gold country Eldorado . In 1537, Francisco Pizarro , the conquistador and governor of Peru, recruited him and appointed him Maestre de Campo . Valdivia helped Pizarro fight the conquistador Diego de Almagro . Francisco Pizarro appointed Valdivia Teniente Gobernador and entrusted him with the Conquista of Chile.

In 1540 Pedro de Valdivia began his expedition to Chile with 150 soldiers. In 1541 he founded the capital Santiago and built up a colonial administration. With great persistence and violence, but also with skill and luck, he prevailed against the permanent fierce resistance of the indigenous population and against mutineers and conspirators from within his own ranks. He succeeded in expanding early colonial Chile beyond the southern border of the former Inca Empire to the Río Bío Bío .

In 1547 he returned to Peru for a year to intervene for the Spanish crown in the Peruvian civil war. There he successfully suppressed the Gonzalo Pizarro uprising. In the same year, Valdivia was appointed captain general and governor of Chile by the Peruvian viceroy and thus received royal confirmation for his conquest enterprise. He returned to Chile with new soldiers and supplies and expanded his colony further south into the so-called Araucania . At the Battle of Tucapel he was captured and executed by the Mapuche under the leadership of Toqui Lautaro . He left the colony of Chile populated with a total of 17 Spanish settlements and fortresses.

Life

origin

Pedro de Valdivia came from a noble family with a long military tradition, originally from the region of the valley of the river Ivia ( Val le d el Río Ivia ) in what is now the province of Palencia in northern Spain, where it got its name from. At the beginning of the 15th century, an ancestor of Valdivia came to Extremadura.

Luis de Roa wrote in a recent research on the family that the conquistador's full name was Pedro Gutiérrez de Valdivia. He was the brother of Diego de Valdiva; the father's name was probably Pedro Gutiérrez de Valdivia; he was married to a woman of unknown name from Almodóvar. The grandparents were Pedro Gutiérrez de Valdivia and María Díaz.

Different historians can find different information about Valdivia's birth. According to Jerónimo de Vivar (* around 1524), who wrote the oldest chronicle on the history of Chile in 1558, he came from Castruera. After Pedro Mariño de Lobera (1528–1595) he was the son of the Portuguese Pedro Oncas de Melo and Isabel Gutiérrez de Valdivia. According to Alonso de Góngora Marmolejo (1536–1575) he came from Castuera in the province of Badajoz and died at the age of 56, that is, born in 1497. Others name Serena in Extremadura, Villanueva de la Serena , Campanario or Zalamea as places of birth .

Soldier in Europe

In 1520 Pedro de Valdivia became a soldier. In 1521 with the beginning of the first war between Emperor Charles V , King of Spain, and the French King Francis I , he took part in the Battle of Valenciana in Flanders . He then came to Italy, where he was under the command of the Marquis de Pescara (1490-1525) and his captain Herrera in the war for Milan (see Italian Wars ) and achieved the rank of Alfaréz (ensign). Valdivia fought in the Battle of Pavia on February 24, 1525 , after which the French king was captured and forced to sign a peace treaty. In May 1527, Valdivia was involved in the sack of Rome as a member of Charles V's runaway mercenary army . The Soldateska sacked the city and besieged the Pope. Valdivia was made captain and returned to Spain. In Salamanca he married the 18-year-old Marina Ortíz de Gaete. Then he went back to Italy without his wife.

Adventure Eldorado

In 1535, Pedro de Valdivia was recruited by Jerónimo de Alderete in the port of Seville to take part in the conquista in Venezuela and in the search for the legendary gold country Eldorado for Jerónimo de Ortal, the governor of Paria . He left his wife Marina in Spain and was never to see her again. After an uncomfortable crossing, Valdivia reached the Caribbean island of Cubagua , the gateway to the supposed paradise in the Spanish colonies in South America, called Tierra Firme. The journey continued into the interior of Venezuela along the Río Paria.

When, at the end of 1536, a call was made to raise more troops for Francisco Pizarro , the conquistador and governor of Nueva Castilla in what is now Peru, Pedro de Valdivia took the opportunity to escape the Venezuelan jungle and advance his career. Together with others he came from Tierra Firme in northern Venezuela to the Panamanian port city of Nombre de Dios . With the force of 400 soldiers formed there under the command of Diego de Fuenmayor, he crossed the isthmus to the city of Panama on the Pacific coast and was embarked there three months later for Túmbez in Peru, from where he overland to Ciudad de los Reyes , today's Lima , came and placed himself under the command of Francisco Pizarro.

Civil War in Peru

A seasoned soldier like Valdivia was exactly what Francisco Pizarro needed. In July 1537 he appointed him Maestre de Campo (field master) of his army. Five years earlier, Pizarro had brought the center of the Inca Empire in Peru under his control; now the Incas had organized an uprising and were fighting the Spanish occupiers quite successfully. Francisco Pizarro marched with Valdivia and 450 soldiers from Ciudad de Los Reyes to Cuzco to help his brothers Hernando Pizarro and Gonzalo Pizarro , who were besieged there by the Inca army . In this situation Francisco Pizarro learned that the conquistador Diego de Almagro had returned with his army from an expedition from Chile and had agreed a truce with the Incas, had taken Cuzco and captured the brothers Hernando and Gonzalo. Pedro de Valdivia, with his many years of experience in war and diplomacy, recognized that an attack on Almagro would trigger a civil war and advised Pizarro against armed struggle. He tried to convince him to arrange a meeting with Diego de Almagro. In the conversation Pizarro should build on the old comradeship with Almagro and appeal to his knightly virtues in order to achieve the release of the brothers in a direct negotiation in a peaceful way. Other advisors pushed for an armed struggle to be prepared from Ciudad de Los Reyes. Francisco Pizarro decided to prepare for the fight; at the same time he sent emissaries to Almagro. Gonzalo managed to escape, and Hernando was eventually released. Then the Pizarros attacked, and with them Valdivia. First the troops broke through the Guaitara Pass in the direction of Cuzco without any particular difficulty, then on April 6, 1538, a decisive battle broke out in the rugged plains of las Salinas about 5 km from Cuzco. Under the leadership of Pedro de Valdivia, the arquebusiers with pelotas de alambre ( wire ball ) were deployed, an ammunition that was new at the time and had a devastating effect on the numerous pikemen infantry of Almagros. So the Pizarros finally defeated their adversary Almagro and executed him without mercy. That was the prelude to a long civil war in Peru, which was not without consequences for Valdivia.

Conquista in Bolivia

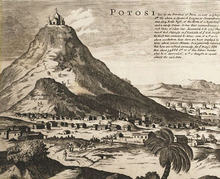

After Almagro was eliminated, Pedro de Valdivia accompanied Hernando Pizarro on expeditions to unconquered plateaus of the Andes. Valdivia received a generous share of the raids from him and became very wealthy during this time. He participated in the Conquista of Charcas in what is now Bolivia , where he acquired his most valuable possessions: a silver mine near Potosí and a particularly large estancia in the La Canela Valley, both of which gave him ample and steady income. But in the end there was also no lack of envious people who complained to Governor Francisco Pizarro that Valdivia got so much of the booty.

In early 1539 Francisco Pizarro traveled to the region where Valdivia was staying for an inspection. In Chuquiabo, today's La Paz , a thousand dissatisfied people were waiting for Pizarro to present their concerns to him. But Pedro de Valdivia did not let himself be deterred and took the opportunity to approach the governor with a special request. He asked Pizarro for permission to conquer Chile. Pizarro gladly granted his loyal troop leader this wish as a reward for his valuable service and appointed Pedro de Valdivia teniente de Gobernador ( lieutenant governor) and captain general (captain general) of Nueva Extremadura , an area in Chile that is south of the former Diego de Almagro designated Nueva Toledo adjoined.

Expedition to Chile

Valdivia spent 9,000 pesos in gold for initial preparations (1 peso in gold corresponds to 4.2 g of fine gold). The prices for the necessary equipment reached exorbitant values. A horse cost up to 2,000 pesos, a sword 50 pesos, a helmet more than 100 pesos, and so the money was not enough for a conquista enterprise. The local moneylenders were unwilling to support him because they were still envisioning the commercial failure of Diego de Almagros when he tried to subdue Chile in 1536. Francisco Martínez, a wealthy trader who had just arrived from Spain, eventually made an agreement with Pedro de Valdivia. Martínez secured 50% of future profits in exchange for equipment worth 9,000 pesos in gold as a deposit into the company.

At the beginning of December 1539, when Valdivia had finished preparing to set off, Pedro Sánchez de la Hoz came from Spain with a license as a conquistador for areas south of the Strait of Magellan and asked Pizarro to subordinate him to the Valdivia expeditionary corps . Hoz had influential friends in Spain, but little else to contribute in order to exercise his license. With skillful diplomacy, Pizarro succeeded in persuading Hoz to work with Valdivia. The two agreed that Valdivia should go first; Hoz was to follow him four months later with ships and supplies to meet him further south in Chunchos.

In January 1540, Valdivia set out from Cuzco with around 1000 Indians and seven Spaniards, including the investor Francisco Martínez, the notary Luis de Cartagena, Inés Suárez 's partner, and Almagro's cousin Alvar Gómez as Maestre de Campo . - an almost poor bunch, compared to the expedition corps that Diego de Almagro had led towards Chile four years earlier, with over 500 soldiers and around 10,000 Indians and three ships. Fortunately for Valdivia, a number of stragglers joined them in the early stage, so that in the end 150 to 170 Spanish soldiers were on their way to Chile. Nevertheless, the expedition gave the impression of an ambulatory colony rather than that of a conqueror. The soldiers with their horses and weapons were accompanied by women, children and pets, and the group transported household items and farm implements.

Valdivia followed the Inca Road south and reached Atacama la Chica (today Chiu Chiu ) and Atacama la Grande (today San Pedro de Atacama ) by the beginning of June . Ahead of them lay a stretch of 80 to 120 iguas (17.5 iguas = 1 ° longitudinal) through the Atacama desert that had to be crossed. A soldier who had changed his mind in view of the difficulties secretly tried to convince others to return to Peru with him. Valdivia did not want to allow its authority to be undermined or its business to be compromised by deserters. When he uncovered the conspiracy, he had the soldier hanged without further ado.

Here Pedro Sánchez de la Hoz caught up with him and attempted an assassination attempt on Valdivia in order to be able to put himself at the head of the expedition. Valdivia was generous and initially let him travel with him in chains for a while. But after a while the two agreed. On August 12, 1540, they jointly signed a public deed in which Hoz ceded all his rights, which he had received from the Spanish king, to Valdivia and undertook not to attempt any cancellation or renegotiation of the contract, on pain of a penalty of 50 pesos in gold to be paid to His Majesty's Treasury. In return, Hoz could hope for a fair share of the booty of the campaign and received a change from Valdivia equal to the value of his belongings. For Valdivia, the arrangement meant that he was rid of a rival and for Hoz, who was practically bankrupt, that he could escape his creditors in Peru with a new perspective.

Conquista in Chile

After crossing the Atacama Desert, the group reached the Copiapó Valley . Valdivia had Indios picked up and tortured ( fuerza de tormentos ) in order to obtain information from them. It soon turned out that the Inca king Manco Cápac II had warned the population about the arrival of the Valdivias expedition. As a result, food and gold were hidden so that the Spanish intruders would not spoil them. With a first solemn act on October 24, 1540, Pedro de Valdivia took possession of Nueva Extremadura . According to Jaime Eyzaguirre, a 20th century Chilean historian, Valdivia is said to have said and done the following:

“'Scribe!' He exclaimed in a clear voice, turning to Cartagena: 'Be attentive to what I will say and do, and authenticate and testify to me, Pedro de Valdivia, who I am captain-general of this army, and also in the On behalf of his Majesty the Emperor Charles V, King of Spain, my ancestral lord, as well as for the Royal Crown of Castile, that I take possession of this province and the valleys, themselves and the other provinces, kingdoms and other countries that I discover 'I will conquer and win and those who remain to be discovered or conquered in this demarcation at the front or in whatever part.' After that, he began to cut branches with the sword, pull up herbs and clear away stones, and added: 'If the possession I have taken was questioned by any person for himself or for any prince or lord of this world 'Then I will wait for you here in this field, armed to defend it and fight until I overpower or kill you or drive you off the field.' A cross, erected over a mound of earth, in front of which everyone kneeled, remained as the spiritual insignia of the conquista in the Valley of Copiapo, the incipient invasion of the regions at the end of the world, known as the occupation certified by Valdiva.

Valdivia stayed in this region for two months and had to assert itself against the resistance of the indigenous people, who badly affected his troops in numerous skirmishes. Valdivia divided its people into small raiding parties to fight the inhabitants. Although the tactic was quite successful, he was unable to gain secure control over the region. He did not establish a settlement here. Under these difficult circumstances he wanted to do it further away from Peru, in order to keep his soldiers from an easy return with a great distance, so that they would then fight all the more doggedly for his cause.

Valdivia moved further south into the valley of the Río Aconcagua , also called "Valley of Chile", where the mighty Kaziken Michimalonco opposed it. He managed to defeat Michimalonco, but the caciques Catiputo and Tanjalongo continued the resistance. Eleven months after Valdivia had left Cuzco, he crossed the Chacabuco pass with his expedition and came to the fertile valley of the Río Mapocho .

Foundation of Santiago

On December 13, 1540, Pedro de Valdivia reached the Río Mapocho and the Inca administrative center Tambo Grande , which was built on the site of today's Plaza de Armas Santiago, via the Qhapaq Ñan , where the streets Independencia and Bandera are today . After crossing the Mapocho, the administrative buildings were occupied to gain control of the area. The hill next to it, called Huelén by the local Picunche natives , Valdivia gave the name Cerro Santa Lucía . The population, warned by couriers of the Inca ruler Manco Cápac II. , Had also hidden their food here and were hostile to the occupiers. In addition, the Spanish invaders ran out of provisions when they arrived and, suffering from hunger, it took them another 20 days until Pedro de Valdivia was able to force the population to negotiate and cooperate. As before, Valdivia had divided its soldiers into smaller groups that roamed the region. The fleeing population, driven by one group, soon found each other facing a different group. This gave the impression that the invaders were numerically superior.

In a conference with 13 caciques: Quilicanta (an Inca from Cuzco), Atepudo, Vitacura (an Inca), Huelén-Huara (from the hill Huelén), Apoquindo, Millacura (from the bank of the Río Maipo), Incageruloneo (from the hills Apochane) , Huarragara (from La Dehesa) and others explained to Pedro de Valdivia that he had been sent by the emperor Charles V, legitimized by God and the Pope, to take possession of his lands and to bring the true faith to the inhabitants. They would have to submit to the Church and the King and thus to him, if not voluntarily, then by force. He asked the cacique Huelén-Huara to clear the area at the foot of the Huelén hill with his people and to move to the Inca settlement Talagante , southwest of the Río Maipo , because he wanted to found a town at the foot of the hill. The caciques bowed to dictation and had to provide labor.

Pedro de Valdivia founded Santiago del Nuevo Extremo , today's capital of Chile , on February 12, 1541 . He chose the place because the Río Mapocho formed a larger island here. This location was favorable to defending the city from the attacks, and the place was far enough away from Peru to prevent its people from returning. On March 7, 1541, Valdivia began building the civil administration with the establishment of the Cabildo , the colonial city government. The peace with the indigenous people did not last long. As early as March 18, 1541, the Cabildo's minutes contain the remark that some of its members were absent because of the armed conflicts with the Indians.

In May it was rumored that Almagro's son Diego Francisco Pizarro had killed Again Valdivia resorted to torture to obtain information from the indigenous peoples and to learn how the news had got to Chile and that the Almagrists had taken power . Because Valdivia had acquired his titles and rights through his participation in the struggle against Almagro and through Francisco Pizarro, this news meant for him and the colonists that their only supply base had been lost and they were in danger of losing everything in the expected vengeance the Almagristen. On May 30, 1541, the members of the Cabildo tried for the first time to convince Valdivia to be elected by them as governor, who would only be subordinate to the king and so the Almagrists could possibly oppose in order to protect the colony and their rights . Valdivia, who was always concerned with formal aspects and legitimacy, initially refused. He also wondered what if the news were a lie and he'd alienated Pizarro with careless actions. Only days later, after many ifs and buts, did Valdivia accept his election to his Majesty's governor on June 11, 1541. As it turned out later, the alleged news from Peru was actually just rumors. Valdivia and his people were so isolated in Santiago that it wasn't until two years later that they learned that the news had preceded what actually happened a little later on June 26th.

Pedro de Valdivia wanted clarity and needed supplies from Peru. So he set out with 12 workers and 8 soldiers to the coast of the Aconcagua Valley to build a boat with which he wanted to send people to Peru. At the same time he took the opportunity to exploit a gold mine near Quillota . During his absence a conspiracy had started in Santiago. Martín de Solier had incited others to overthrow Valdivia and then return to Peru. Alonso de Monroy noticed this and notified Valdivia, who returned immediately and arrested the conspirators. After a brief examination, he hung Solier and four others, thereby gaining the respect necessary to consolidate his position. But the external threat increased. Shortly afterwards, Captain Gonzalo de los Ríos and the black slave Juan Valiente returned from the coast. They were the only survivors after an attack by Michimalonco that started a new uprising. As the situation continued to escalate, he had some caciques in the Mapocho valley captured and held hostage in his house in Santiago.

On September 11, 1541, Michimalonco began a raid on Santiago. Pedro de Valdivia was at the same time involved in fighting with part of his troops south in the valley of Cachapoal . The overwhelming majority of the attackers - contemporaries exaggeratedly estimated 10,000 people - were able to burn Santiago down and almost succeeded in freeing the captured caciques. Shortly before a defeat, Inés Suárez, Pedro de Valdivia's partner, was able to turn the tide with an idea. She suggested beheading the seven captured caciques. She herself beheaded the first with her sword. When Michimalonco's warriors saw the heads in the hands of the Spanish attackers, they began a confused retreat from the interior of Santiago. But it was only shortly before dark that the attack was finally repelled.

With this spectacular event began a state of war and siege that dragged on for over two years. The street block on the north side of the Plaza de Armas was expanded to form a refuge with a completely surrounding mud wall 2.50 meters high and 2.10 meters deep , with four low towers in the corners and rooms for storing weapons and goods. The conquistadors found themselves in an extremely precarious situation. They suffered from permanent food shortages and were completely isolated from the rest of the world. Hunting was difficult, and agriculture was little relief. They even ran out of clothes. Pedro de Valdivia sent Alonso de Monroy with five horsemen to Peru in January 1542 to request help. For twenty months full of privation, Valdivia and its colonists had to hold their own against all odds, until Monroy returned in December 1543 with 70 riders and an aid delivery. This ended the isolated and demoralizing situation in Santiago. The uprising had failed, the Indians retreated south, and the city was relatively safe. Valdivia began systematic expeditions from Santiago to colonize the country. So at the turn of the year 1543/1544 he sent Juan Bohón with ten soldiers to found a second city in the Coquimbo Valley with the name of San Bartolomé de la Serena and to set up a few rest stops (so-called tambos ) on the way to Peru.

Up to the Río Bío Bío

In the middle of 1544 further support came with the ship San Pedro of the captain Juan Bautista de Pastene . The governor of Peru Cristóbal Vaca de Castro had sent it to explore the coast up to the Strait of Magellan and to look for Valdivia. Valdivia took the opportunity to use the experienced Pastene and his ship to take possession of the coast up to the Strait of Magellan. On August 8, 1544 Pastene was appointed Teniente de Capitán General del Mar del Sur (about: Lieutenant General Captain of the South Seas) by Valdivia . About a month later, on September 4th, Pastene set sail accompanied by Jerónimo de Alderete . After three days they reached 41 ° South and returned north to explore the coast and to take possession of the land, at least symbolically, for the Spanish king and thus for Valdivia.

Almost a year later, in September 1545, Valdivia sent Pastene with the San Pedro , accompanied by Alonso de Monroy and Antonio de Ulloa with gold to Peru. Monroy and Pastene were supposed to get supplies and Ulloa was supposed to sail to Spain to Charles V, to solicit and secure the title of governor for Valdivia for the zone up to the Strait of Magellan and in the whole width between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Due to the betrayal of Ulloa, the project failed on arrival in Peru, which was ravaged by the ongoing civil war. The gold and ships were confiscated, Monroy was critically ill and Pastene was placed under a kind of house arrest.

At the same time Valdivia began to expand its colony south. With 60 mounted soldiers, he moved to the Río Bío Bío. Once there, they were put to flight by a large majority of Mapuche. Nevertheless, the expedition was a success, because it was possible to use the area up to the Río Bío Bío for the colony. In August 1546 Valdivia dispatched another ship with gold to get supplies, even without the desired success. In the meantime, Pastene managed to buy and equip a ship in Peru in order to set off for Chile. After all, it had been 31 months since Valdivia had sent Pastene when he finally returned to Santiago with the bad news about the circumstances of his trip and the deepening crisis in Peru.

Back to Peru

In the seven years that Pedro de Valdivia stayed in Chile, the civil war between the supporters of Pizarros and Almagros had escalated. The governor Francisco Pizarro was killed in 1541, and his opponents had named Almagros' son , who was also called Diego, as his successor. Cristóbal Vaca de Castro , a judge of the Real Audiencia , who had been installed as governor by the Spanish king, had to assert himself against the warring parties by force of arms, which in turn led to the execution of Almagro's son in 1542. Vaca de Castro, in turn, was imprisoned in Lima in 1544 by the newly appointed Viceroy Blasco Núñez de Vela . For his part, the viceroy was arrested by auditors in his palace. Gonzalo Pizarro , who was returning from a long expedition from the virgin forests east of Quito , was asked to retire to his lands, but instead occupied Lima and later Cuzco with 1200 soldiers. Most recently, Valdivia learned from Pastene that all its efforts to get supplies and support from Peru had been in vain. Pedro de Valdivia realized that the civil war in Peru represented a great danger for him and his colony and that only with the help of the Spanish king would he achieve his great goal of becoming governor of Chile. He decided to support the loyal Spanish troops under the leadership of the legitimate viceroy Pedro de la Gasca in the suppression of the rebellious Gonzalo Pizarro.

In order to have as much gold as possible available for his company, he developed a plan. Valdiva announced that he wanted to send another ship to Peru. He was soon contacted by a number of people asking for permission to return to Peru. Valdivia granted permission. The returnees packed their hoarded gold, sold their things and embarked in Valparaíso. Shortly before departure he invited everyone to a farewell dinner ashore; at an opportune moment he set off with the ship and the gold of his men. Valdivia had prepared everything well. A few days earlier he had appointed Francisco de Villagra as deputy governor and administrator of his personal property with the consent of the Cabildos of Santiago . The ship belonged to his loyal follower, the captain Juan Bautista de Pastene, who now brought him together with eleven captains from Valparaíso to Callao , the port of Lima.

Twenty days later, on December 30th, Pedro de Valdivia arrived in Callao. The Viceroy Pedro de la Gasca appointed Valdivia Maestre de Campo jeneral del ejército (General Field Master ) and appointed him his secret advisor. On April 9, 1548, they defeated Gonzalo Pizarro in the battle of Xaquixaguana (or Jaquijaguana), on a plateau about 25 km west of Cuzco. Gonzalo was executed by beheading the following day.

Valdivia used the rest of his stay in Peru to secure his position in Chile. At his request, Pedro de la Gasca promised to order soldiers to support him in Chile and on April 23, 1548, appointed him governor and captain general of Chile in Cuzco. However, Gasca limited the governorate to the region of Copiapo as the northern border to 41 ° south in a strip of 100 iguas (17.5 iguas = 1 ° longitudinal) from the coast to the east. Then Valdivia traveled to Lima, where he recruited people to reinforce him. He recruited many soldiers from among the hapless, impoverished veterans from Gonzalo Pizarro's entourage, plus 5 priests, 15 Spanish war widows , the lawyers Antonio de las Peñas and Pedro González. He also got a lot of clothes, plenty of ammunition, plants and other essential equipment.

Around mid-1548, Valdivia and his entourage returned to Chile. His soldiers plundered along the way to provide for themselves. Once in Atacama, Valdivia was arrested by Pedro de Hinojosa and brought back to Callao. Valdivia had been charged with looting its soldiers. Viceroy Gasca soon acquitted him of all charges. In October 1548, shortly before Valdivia could leave, a ship came from Chile with the colonists whom he had cheated out of their gold. Again he faced an indictment, this time with 57 allegations. Fortunately for him, the whole burden of proof was placed on the stolen, and because everyone was prosecuting, no one was left to witness. Valdivia, for his part, promised to compensate everyone in Chile. So here too, a short process was made. Within a month, Valdiva cleared the allegations in both trials. On December 3, 1548, the Real Audiencia in Lima confirmed Valdivia's title as Captain General and Governor of Chile. So well legitimized and equipped, Valdivia sailed from Arica on January 21, 1549 with three ships, accompanied by 200 men back to Valparaíso .

Pedro de Valdivia arrived in Santiago on June 10, 1549. He was received triumphantly by the colonists in Santiago with great joy about his return and the new supplies. It is said that there were three days and nights of celebration afterwards. In the expectation that the soldiers promised by Gasca would come from Peru through the Atacama Desert and to be able to help them on their way, Valdivia had the settlements in La Serena and Copiapo that had been destroyed during his absence rebuilt. He entrusted this task to Francisco de Aguirre, who set out in July 1549 with 80 soldiers.

Expansion of the colony

Pedro de Valdivia's goal was to expand his colony as quickly and as widely as possible. In the south it should extend to the Strait of Magellan , the strait that connects the Atlantic and Pacific oceans in the south of the continent. In the east it should extend to the Atlantic. So from the 26th parallel south he wanted the entire rest of the continent south for himself. And he had to hurry because other conquistadors were pushing into these areas. On December 20, 1549, he deposited his will in the care of the city government of Santiago. At the beginning of January 1550 he set off with 150 to 200 soldiers and many Indians and advanced south. That was the prelude to the long-term so-called Arauco War . He crossed the Río Maule and the Río Itata and penetrated the Penco Valley north of the Río Bío Bío , where he founded the town of Concepción del Nuevo Extremo with a small fortification on the coast . In March 1550 it came to the battle of Andalién. About 6,000 to 8,000 Mapuche of Penco under the leadership of Aillavillú succeeded in enclosing the troops of Valdivia. The warriors running in en masse brought the Spanish invaders into dire straits. Valdivia lost his horse in the process and was almost captured. But with the superior firearms ( arquebuses ), the soldiers on horseback and a superior tactic, the Araukans were successfully fought. Ayllavilu was critically injured and taken prisoner. After losing more leaders, the Araucans only had to flee in the end. Valdivia made peace with the Mapuche, who in return had to cede the Penco Valley. At the beginning of April the city of Concepción could then be traced. In December 1550 Valdivia fended off another heavy attack led by Caupolicán . In a punitive action, Valdivia had around 200 Mapuche prisoners cut off their ears and noses before releasing them.

In the following three years Pedro de Valdivia succeeded in expanding the colony beyond the borders of the past Inca empire. In January 1551 he set out from Concepción with 200 soldiers and some Indians and crossed the Río Bío Bío, which the Incas had not overcome. Valdivia penetrated to the Río Cautín , where he founded the city of Imperial (now Carahue ) in March . About a year later, in February 1552, he founded the city of María de Valdivia at 39 ° 40 'South. He established a fortress and took some Mapuche hostage to prevent attacks. He also took the hostages with him on his expeditions. Valdivia had recognized that he could not simply defeat and subjugate the Araucans militarily and that the way to control the colony was to establish as many settlements as possible. In the same year he founded the city of Villarrica .

At the end of 1552, Pedro de Valdivia traveled to Santiago. From there he sent Jerónimo de Alderete to Spain to inform the Spanish king about the progress of the conquista and to ask the monarch for Valdivia for the title of governor for the whole zone between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Then Valdivia planned the conquest of areas east of the Andes. In December he entrusted Francisco de Aguirre with this task. With 100 soldiers he was to move from La Serena through the valley of the Río Elqui and cross the Andes. Then Pedro de Valdivia returned to Concepción. From there he directed his troops to 43 ° south and then turned to Eastern Patagonia , with the aim of founding a port city on the Atlantic to facilitate trade with Spain.

the last fight

In December 1553, Pedro de Valdivia received a message from the Tucapel fortress that the Araucans were preparing a revolt. Under the leadership of the Colo Colo cacique , the Araucans had decided to fight for their freedom and chose the Caupolicán cacique to be Toqui (war chief). Valdivia immediately had the nine caciques Guaito, Pangue, Lincuo, Guaicha, Paineli, Renque, Llaipo, Toraquin and Millanque arrested in order to then torture them lying on the floor over embers and extract information from them. But the caciques gave no information. Soon after, the Tucapel fortress was destroyed. At the end of December, Valdivia left the city of Concepción with 50 soldiers to face the Araucans. But first he went to one of his gold mines in the zone and secured it against possible attacks. Only then did he go in the direction of the fortress Tucapel near the present-day city of Cañete . When they arrived in the destroyed fortress, they were attacked and surrounded. This time Valdivia was unable to cope with the overwhelming odds and a new tactic of Toqui Lautaro and was captured.

The so-called Battle of Tucapel ended on December 25, 1553 with the death of Pedro de Valdivia. The chronicler Alonso de Gongora reported that he had learned from a Spaniard, Don Alonso, who is said to have been there as an eyewitness but was able to escape, that Valdivia was attacked by a group with lances and clubs, pulled from the horse, disarmed and tied up would have been. Valdivia was held prisoner together with an Inca servant called Agustinillo and the priest Bartolomé del Pozo and Caupolicán and Lautaro were brought before them. The three were tortured and killed and their severed heads were put on spears. The chronicler Vicente Carvallo reported that Valdivia was allegedly killed with a club on the head by a Mapuche named Lebentun three days after his capture. There are several other versions of Valdivia's death. There is no evidence of how he died. The date of death was given as the 25th, 27th or 31st December 1553.

Until then, Pedro de Valdivia had achieved considerable success. He had begun a conquista, giving up an already well-secured existence, for which almost no one granted him credit at first. He had stubbornly and forcefully prevailed against all odds and conquered a colony that was populated with 17 Spanish settlements between the 26th and 42nd parallel south over the course of 13 years. These were the nine cities of Santiago del Nuevo Extremo , San Bartolomé de la Serena , El Barco , Concepción del Nuevo Extremo , Imperial , Santa María de Valdivia , Villarrica , Angol de los Confines and Santa Marina Ortíz de Gaete , the four villages of Copiapó , Valparaíso , Diaguistas and Juríes and the four fortresses Quillota , Cuyo , Tucapel and Arauco . In the end, around 1,200 Spanish soldiers across Chile were subordinate to him. He left no children.

literature

- Amunátegui Aldunate, Miguel Luis (1828–1888): Descubrimiento i conquista de Chile - Pedro de Valdivia . Imprenta, Litografía y Encuadernación Barcelona, Santiago de Chile 1913 ( Memoria Chilena - Documents ).

- Luis de Cartagena: Actas del Cabildo de Santiago de 1541 a 1557. In: Colección de historiadores de Chile y de documentos relativos a la historia nacional. Volume 1 . Imprenta del Ferrocarril, Santiago de Chile 1861 ( Memoria Chilena - Documents ).

- Vicente Carvallo Goyeneche (1740-1816): Descripción-histórico-jeográfica del reino de Chile, Volume 1. In: Colección de historiadores de Chile y de documentos relativos a la historia nacional, Volume 8 . Imprenta del Ferrocarril, Santiago de Chile 1875 ( Memoria Chilena - Documente ).

- Luis Cornejo: Los Inka y sus aliados Diaguita en el extremo austral del Tawantinsuyu. In: Tras la huella del Inka en Chile . Museo de Arte Precolombino, Santiago de Chile 2001 ( Library, Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino (PDF)).

- Jaime Eyzaguirre (1908–1968): Ventura de Pedro de Valdivia . Ercilla, Santiago de Chile 1942 ( Memoria Chilena - Documente ).

- Alonso de Gongora Marmolejo (1524–1575): Historia de Chile desde su descubrimiento hasta el año de 1575. In: Colección de historiadores de Chile y de documentos relativos a la historia nacional. Volume 2 . Imprenta del Ferrocarril, Santiago de Chile 1862 ( Memoria Chilena - Documente ).

- Pedro Mariño de Lobera (1528–1595): Crónica del reino de Chile. In: Colección de historiadores de Chile y de documentos relativos a la historia nacional. Volume 6 . Imprenta del Ferrocarril, Santiago de Chile 1865 ( Memoria Chilena, Documente ).

- José Toribio Medina (1852–1930): Diccionario biográfico colonial de Chile . Imprenta Elziviriana, Santiago de Chile 1906 ( Memoria Chilena - Documents ).

- Luis de Roa y Ursúa (1874-1947): La familia de Don Pedro de Valdivia conquistador de Chile . estudio histórico. Imprenta de la Gavidia, Seville 1935 ( Memoria Chilena - Documents ).

- Luis de Roa y Ursúa: El Reyno de Chile 1535-1810 . Estudio historico, genealogico y biografico. Talleres Tipográficas Cuesta, Valladolid 1945.

- Gerónimo de Vivar (1524? -): Crónica y relación copiosa y verdadera de los reinos de Chile 1558. In: Fondo Histórico y Bibliográfico José Toribio Medina, Volume 2 . Instituto Geográfico Militar, Santiago de Chile 1966 ( Memoria Chilena - Documents ).

- Justin Winsor (1831-1897): Narrative and Critical History of America, Vol. 2 . Houghton Mifflin and Company, Boston; New York 1886 ( Internet Archive, Presidio of San Francisco ).

Further literature:

- Simon Collier, William F. Sater: A History of Chile . Cambridge Latin American Studies, 2004, ISBN 0-521-82749-3

- Ricardo E. Latcham: The Art of War of the Araucanos . ISBN 3-88506-403-0

- Armando De Ramon, Armando de Ramsn: Breve Historia de Chile: Desde la Invasion Incaica Hasta Nuestros Dias (1500–2000) . (Coleccion Historias Americanas). 2001, ISBN 950-786-294-3 , Spanish

- Pedro de Valdivia . In: Grandes Biografías de la Historia de Chile (English)

- Inés de Suarez . In: Grandes Biografías de la Historia de Chile (Spanish)

- Ann K. Nauman: Inés de Suárez, Conquistadora (PDF) V Congreso de las Américas (Universidad de Américas). Southeastern Louisiana University

Web links

- Literature by and about Pedro de Valdivia in the catalog of the German National Library

Individual evidence

- ↑ Luis de Roa y Ursúa . 1945, p. 85

- ↑ Luis de Roa y Ursúa. 1935, p. 13

- ↑ a b Luis de Roa y Ursúa. 1935, p. 79

- ↑ Luis de Roa y Ursúa. 1935, pp. 118f

- ↑ Luis de Roa y Ursúa. 1935, p. 87 and p. 114f

- ↑ a b c Jerónimo de Vivar. 1966, p. 3

- ↑ a b c d e Pedro Mariño de Lobera. 1865, p. 158

- ^ Alonso de Gongora Marmolejo. 1862, p. 39

- ↑ a b Justin Winsor. 1886, Vol. 2, p. 528

- ^ A b Vicente Carvallo Goyeneche. 1875, p. 74

- ↑ Luis de Roa y Ursúa. 1935, p. 8

- ↑ Luis de Roa y Ursúa. 1935, p. 11

- ^ Alonso de Gongora Marmolejo. 1862, p. 5

- ↑ Pedro Mariño de Lobera. 1865, p. 37

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 31f

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 32

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 33

- ↑ Jerónimo de Vivar. 1966, p. 4

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 34

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 36

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 37

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 41ff

- ↑ a b Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 53

- ↑ Jerónimo de Vivar. 1966, p. 6

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 54

- ↑ Vicente Carvallo Goyeneche. 1875, p. 11

- ^ FA Kirkpatrick: El Dinero In: Los conquistadores españoles .

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 56f

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 58f

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 60

- ↑ see Diego de Almagro

- ^ A b Pedro Mariño de Lobera. 1865, p. 38

- ↑ a b c Alonso de Gongora Marmolejo. 1862, p. 6

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, pp. 189f

- ↑ ?

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 189

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 190

- ↑ Jerónimo de Vivar. 1966, p. 20

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 73. Translation from Spanish user: WeHaKa

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 77

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 192

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 78

- ↑ a b Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 79

- ↑ Luis Cornejo. 2001, p. 103

- ↑ Armando De Ramón. 2000, p. 16

- ↑ Jerónimo de Vivar. 1966, p. 38f

- ↑ Jerónimo de Vivar. 1966, p. 39

- ↑ Pedro Mariño de Lobera. 1865, p. 45

- ↑ Vicente Carvallo Goyeneche. 1875, p. 19

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 80

- ↑ Luis de Cartagena. 1861, p. 67

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 82

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 195

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 84

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, pp. 196-198

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 204

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 209

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, pp. 210f

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 212ff

- ↑ Armando De Ramón, 2000, pp. 17ff

- ↑ Armando De Ramón, 2000, p. 22ff

- ↑ Pedro Mariño de Lobera. 1865, p. 60

- ↑ Armando De Ramón, 2000, p. 24ff

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 220ff

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 230

- ↑ a b José Toribio Medina. 1906, p. 646 f.

- ↑ a b Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 232.

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, pp. 238-247.

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, pp. 247-256.

- ↑ Justin Winsor. 1886, Vol. 2, pp. 537ff

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 256

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, pp. 259-265

- ↑ Vicente Carvallo Goyeneche. 1875, p. 41

- ↑ Justin Winsor. 1886, Vol. 2, p. 534

- ↑ Vicente Carvallo Goyeneche. 1875, p. 44f

- ^ A b Vicente Carvallo Goyeneche. 1875, pp. 45f

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 268ff

- ↑ Justin Winsor. 1886, Vol. 2, p. 572

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 272

- ↑ a b Justin Winsor. 1886, Vol. 2, p. 548

- ↑ Jerónimo de Vivar. 1966, p. 129

- ↑ Vicente Carvallo Goyeneche. 1875, p. 46

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 286

- ^ A b Vicente Carvallo Goyeneche. 1875, p. 50

- ↑ Vicente Carvallo Goyeneche. 1875, p. 51f

- ↑ Vicente Carvallo Goyeneche. 1875, p. 55

- ↑ a b c Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 302

- ↑ Vicente Carvallo Goyeneche. 1875, p. 56

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 306

- ↑ Vicente Carvallo Goyeneche. 1875, Volume 1, pp. 59f

- ↑ Vicente Carvallo Goyeneche. 1875, p. 62ff

- ↑ Vicente Carvallo Goyeneche. 1875, p. 64

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 316

- ↑ Pedro Mariño de Lobera. 1865, p. 151

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 320

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 185

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 324

- ↑ Jaime Eyzaguirre. 1942, p. 188

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 327ff

- ^ Alonso de Gongora Marmolejo. 1862, p. 38f

- ↑ Vicente Carvallo Goyeneche. 1875, p. 73

- ↑ Miguel Amunátegui. 1913, p. 332ff

- ↑ Luis de Roa y Ursúa. 1935, p. 89

- ↑ a b Justin Winsor. 1886, Vol. 2, p. 549

- ↑ Vicente Carvallo Goyeneche. 1875, p. 65

| personal data | |

|---|---|

| SURNAME | Valdivia, Pedro de |

| BRIEF DESCRIPTION | Spanish conquistador and governor of Chile |

| DATE OF BIRTH | April 17, 1497 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Castuera, Extremadura , Spain |

| DATE OF DEATH | December 25, 1553 |

| Place of death | Tucapel , Chile |