poster

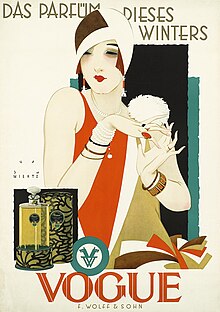

Poster art by Jupp Wiertz for the cosmetics manufacturer F. Wolff & Sohn , 1926/27

A poster is a large sheet of paper or fabric, usually printed with text and images , which is attached to a billboard , a poster tab , an advertising column or other suitable surface in public in order to convey a message. By its very nature, the poster is a message to an anonymous group of recipients. The sender cannot immediately check whether his message reaches the individual recipient and how he or she reacts to it.

Word meaning

The word poster appears in the Netherlands in the 16th century . During the liberation struggle against the Spanish occupiers, the Dutch had glued leaflets onto house walls and walls . Such sheets of paper were called plakatten (New Dutch plakkaat ). In French, this resulted in plaque ("plate, tablet") and placard ("stop"). In Germany in 1578 the satirist Johann Fischart first used the word poster to mean a public announcement to the authorities.

precursor

The forerunners of the poster can be found in pre-Christian times. In ancient Rome, legal texts or official notices were posted on white wooden boards (albae) in public places. In the 16th and 17th centuries, early forms of the picture poster developed - for isolated product offers or the appearances of jugglers' troops was advertised with notices in which texts were combined with pictures. In the 18th century, illustrated posters were used to recruit soldiers, and since around 1830 book illustrators in France have also been designing posters for the book trade.

The modern picture poster

In the mid-1930s, the American word ("poster") arrived in the German-speaking world. In its edition of February 9, 1935, the Kölnische Illustrierte Zeitung headed an article with "POSTER - a new photographic catchphrase from America". It became the most important advertising medium until the mass distribution of television around 1970. The poster has hardly changed since then. Then, as now, it was printed in large numbers on paper, was large, colored, conspicuous, contained images and text in the most sensible arrangement possible and wanted to convey something. In fact, besides the style of the representations, a lot has changed in the meantime without this being apparent at first glance:

- The design technique : After more than a hundred years of at best gradual progress in the manual production of designs - for example through the use of photography and photo montage, airbrush technology or photo typesetting - a revolution in this field began with the use of powerful computers . Today, graphic design is created almost without exception on the computer.

- The printing technique : for decades, color lithography remained the standard in poster printing, after the Second World War it was replaced by screen printing and photo offset printing .

- The areas of application: Initially, posters almost exclusively advertised dance halls and individual consumables, later the whole world of goods and services was offered (with the special categories of film, sport, travel, etc.); In addition, there was the broad field of political influence.

- Coordination with other advertising media: After 1900, the realization gradually gained acceptance that a single advertising medium could not guarantee optimal sales success. The aim was a uniform image of the provider, to which the poster, as one of several building blocks, should contribute. Peter Behrens , artistic advisor to AEG in Germany since 1907, was a pioneer in this field .

- The importance in relation to other media: Compared to the initially dominant position, the poster has steadily lost its importance as an advertising medium. Decisive reasons for this were the further development of the press as an advertising medium and new media such as radio, television and the Internet.

- The evaluation of the poster as an object of art or utility: Especially between 1890 and 1910, but also occasionally afterwards, it was discussed extensively and controversially (see below: The Art Discussion ).

The function of the poster is to convey information quickly, often linked to propaganda purposes. The target group of the poster includes not only those who are looking for this information, but also those who perceive the poster and its message in passing. Since hardly any major social event can do without the poster (e.g. elections, including bogus elections, exhibitions, films, theater productions, memorial days, sports festivals, appeals, advertising for consumer goods), the poster has great everyday significance. It is therefore a mirror of social conditions and an important source for understanding a time.

The glass poster

The foundation stone for glass poster production was laid in 1821 by Jakob Anton Derndinger with the construction of the glassworks in Niederschopfheim. In 1825 the glassworks was relocated to Offenburg and operated under the name "Derndinger & Co., Glasmanufaktur". In 1833 Ludwig Brost became a partner; henceforth the company was called "Derndinger & Brost". In 1857 the company was founded by Carl Nikolaus Geck and Carl Ludwig Weißkopf under the new name “C. Geck & Cie. ”. Decorated window glasses with engraved rosettes and stripes as well as colorfully decorated church windows were produced. The production of muslin glass stepped out of the experimental stage.

In 1862 Carl Weißkopf and Adolf Schell founded a workshop for muslin glass production. When Wilhelm Schell I joined the company in 1863, the actual glass painting began. In 1876 Otto Vittali joined the company, which was now called "Geck & Vittali". In 1876 Adolf and his son Wilhelm I. Schell separated. The company name was now "Adolf Schell & Otto Vittali GmbH". Wilhelm Schell I set up his own business, which passed to his son Paul Schell after his death. The production was switched to glass grinding and brass glazing.

Wilhelm Schell II, another son of Wilhelm Schell I, founded the "Glasplakate-Fabrik Offenburg Wilhelm Schell" in 1896, which he managed until 1934. Now the glass poster production began on sheet glass by means of stone printing, silver plating, gold leaf plating and etched panes in three to four tones, which were in great demand for hotels and larger villas at the time. The glass poster was an independent advertising medium, the posters were applied directly to the glass and thus protected by the glass so that they could be used outdoors.

Development until 1918

Artist posters

Until the middle of the 19th century, poster design and production lay almost exclusively in the hands of printers and lithographers. With the increased demands on the quality of posters, they were often overwhelmed. Now artists took up the matter, first in England and especially in France. Jules Chéret , considered a pioneer of poster art, was both a craftsman and an artist. As a trained lithographer, he worked in London for several years, where he learned how to print large paper formats and, as an artistic self-taught artist, designed posters for opera and circus, among other things. Back in Paris, now the owner of his own print shop, he simplified the complicated color lithography so much that only three to five stones were needed for good color prints, instead of up to 25 as before.

This reduced costs considerably and was an important prerequisite for the wide distribution of high-quality posters. It also allowed the artists of the time to work with the simplified technique. Chéret himself created a multitude of lively illustrative posters, on each of which an attractive, relatively lightly clad young woman advertised places of entertainment, vermouth , cigarettes or petroleum . These representations were enthusiastically received by the audience, certainly also because Chéret combined images and texts into a concise unit and had fundamental thoughts about advertising: “The poster artist [...] has to invent something that even the average person has to do and stimulate when he does from the pavement or the car lets the image of the street rush past his eyes. "

Recognized painters and graphic artists accepted orders for posters. This is how masterpieces of the lithographic artist poster emerged, for example by Eugène Grasset ( Librairie Romantique , 1887), Pierre Bonnard ( France Champagne , 1889), Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec ( Moulin Rouge - La Goulue , 1891) and by Alphonse Mucha , who through his designs became famous for the actress Sarah Bernhardt . Mucha's works are considered to be the first high points for the graphics of the Art Nouveau (in France: Art Nouveau), the dominant art movement of the Belle Epoque . France was the early center of this development.

The art discussion

Jules Chéret received the Cross of the French Legion of Honor in 1888 . The reason stated that with the poster he had "created a new branch of art ... by transferring the art to commercial and industrial print products." A contemporary of Cherets found, "The most beautiful natural spectacle will never outweigh the sight of a billboard". Such views were typical of the height of the "poster movement" in the 1890s. Posters were evaluated according to the criteria of fine art. Public and private poster collections were created. Art dealers specialized in posters, and exhibitions provided information about the latest developments. A Parisian printing company brought out the most sought-after artist's posters as small binders, the great success prompted imitators to publish similar items. Walter von Zur Westen, a committed German collector and member of the Association of Poster Friends , formulated the widespread expectations as follows: “Can artistic posters [...] arouse love and understanding for good art even in circles that otherwise do not come into contact with it . "

This idealistic approach lost its importance after 1900. An objective, increasingly scientific evaluation of the advertisement soon revealed that an artistically high quality poster was not necessarily the most effective advertising medium. The Austrian draftsman and commercial artist Julius Klinger registered that “the misunderstanding arose that advertising and artists coincided”. Posters continued to be designed using all imaginable artistic techniques and taking into account generally applicable rules of composition , color theory , etc. - but now the criteria of advertising psychology became decisive . Instead of artists, commercial graphic artists were asked for, specialists in advertising. They recognized and accepted that they lived in a special environment and had to respect its laws. It has stayed that way ever since.

Eugène Grasset : Librairie Romantique , 1887

Toulouse-Lautrec : Moulin Rouge - La Goulue , 1891

Ludwig Sütterlin : Industrial exhibition , 1896

Adolfo Hohenstein , for Puccini's opera Madama Butterfly , 1904

After the Art Nouveau

The Glasgow School , Wiener Sezession and Deutscher Werkbund were artists' associations around 1900 whose membersbegan to leavethe lavish ornamentation of Art Nouveau behind, to use simple structures instead and place greater emphasis on functionality. Between 1894 and 1898 the British studio community of the two Beggarstaff Brothers existed , whose posters were designed according to the new principles. In doing so, they also influenced the “German poster style” (also known as non-artifact posters in Germany and Switzerland). An early, much-noticed forerunner for its development was the poster for the industrial exhibition Berlin 1896 by Ludwig Sütterlin ; The work of Lucian Bernhard since 1905 is regarded as the actual beginning. Typical of Bernhard's posters was the reduction to just two essential elements: product presentation and brand names. In Germany, the focus of poster work was established in Munich with Thomas Theodor Heine , Valentin Zietara , Franz Paul Glass , Friedrich Heubner , Carl Moos , Max Schwarzer , Bruno Paul , Emil Preetorius and Ludwig Hohlwein , in Dresden with Hans Unger , Otto Fischer and Johann Vincenz Cissarz and especially in Berlin. Peter Behrens , Lucian Bernhard , Ernst Deutsch-Dryden , Edmund Edel , Hans Rudi Erdt , Julius Gipkens , Julius Klinger and Paul Scheurich worked there in the vicinity of the Hollerbaum & Schmidt printing and art establishment.

With the beginning of World War I , the poster was given a new task: political propaganda . All the warring parties used posters en masse to recruit soldiers, raise money through war bonds , promote arms production and make the respective enemy look bad. In the United States at that time, 2500 poster designs were created in less than two years, of which almost 20 million copies were printed. After the end of the war, normality also became normal in Germany, which was strictly forbidden until 1914: political parties and groups of all kinds used posters to propagate their goals or to attack their opponents. In Russia, under Lenin , the Bolsheviks used posters en masse and successfully as propaganda instruments in the fight against their enemies in the civil war.

1918 to 1945

After the First World War , the professional environment of the poster designer was given more solid structures - specialist magazines appeared and professional associations emerged. In Germany, the “Bund Deutscher Nutzgraphiker” (BDG) has represented the interests of the qualified and professionally active designers since 1919; it was renamed in 1968 to “ Association of German Graphic Designers ”. In 1922 , the German Institute for Standardization established uniform paper formats according to DIN 476 as the technical basis .

Constructivism, De Stijl, Bauhaus

All currents of the visual arts - Cubism , Futurism , Dadaism and Expressionism - left their mark on the advertising graphics of that time. The Russian constructivists in the Soviet Union in the 1920s - El Lissitzky , Alexander Rodchenko , Lyubow Popowa and others - also influenced Western design with their strict "agitational" style. Movements such as De Stijl (a Dutch artists' association since 1917) and the Bauhaus (founded in Weimar in 1919) were looking for an aesthetic that could be applied to all areas of design - including the poster - for a largely abstract formal language that was less, more fundamental from the variation Elements existed. Herbert Bayer and Joost Schmidt are considered to be the most influential poster designers at the Bauhaus . Bayer had been a student since 1921, then a journeyman at the Bauhaus, and from 1925 to 1928 he was in charge of the newly established Bauhaus printing and advertising department. Schmidt started as a student at the Bauhaus in 1919 and succeeded Herbert Bayer as head of his department in 1928. Other Bauhaus posters come from Karl Straub, Max Gebhard, Max Bill and others.

Paul Leni : Cover of the special film issue of the magazine Das Plakat , October 1920

El Lissitzky for Pelikan AG in Hanover , 1929

Art deco

At about the same time as the Bauhaus design, the design language of Art Déco developed , also an international style that encompassed all areas of life, from architecture to posters. Here, too, forms were simplified, but not as rigorously as at the Bauhaus. Individual, clear style features were not available. Influences came again from the current visual arts, but also from the art of Persia , Egypt and Central Africa . The prevailing impression was one of pleasing elegance. The term Art Déco was derived from an exhibition that took place in Paris in 1925: "Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriel Modernes". Leonetto Cappiello in Paris paved the way for the poster art of French Art Deco early on with simplified, mostly humorous advertising messages. The climax was reached with the rather coolly calculated works of AM Cassandre , who used the spray gun for his smooth surfaces , as well as for the famous, striking depictions of ocean liners such as “Normandie” or “Atlantique”. In Germany, Ludwig Hohlwein primarily represented this style.

The French artist Roger Broders used his posters in a clear, reduced style from the 1930s to advertise, among other things, the French railways and the tourist regions in the Alpine region that they developed.

War propaganda

During the Second World War , posters were again primarily used for war propaganda, as they had been between 1914 and 1918, both among the Allies and on the part of the fascist " Axis Powers ". The " Reich Ministry for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda " of the German National Socialists ascribed particular importance to the poster for influencing the population. Studies such as The Political Poster. A Psychological Consideration and The Battle Poster. The nature and regularity of the political poster ... underlined this attitude.

Since 1945

GDR

From the summer of 1945 the first posters appeared in the Soviet occupation zone (SBZ), which were intended to mobilize for the reconstruction, to secure elementary living conditions and to help settle the accounts with National Socialism. The artistic variety was not initially limited. With the establishment of the two German states, GDR cultural policy began to differentiate itself from the “decadent bourgeois art school”. Posters showed “page-filling, symbolic images, restrained colors and clear language” and thus ensured “optical distance to the heroic sheets of the Nazi era”. Due to the lack of demand for goods, goods were no longer advertised on posters from around 1970. In return, exhibition notices, concerts and political events continued to find their way onto mostly very attractively designed posters, designed and printed in the Graphische Werkstätten Berlin, a forerunner of the Berlin printing company . This was an important printing company that produced all kinds of posters and numerous other printing materials.

An exhibition on poster art in the GDR took place in the state capital Schwerin in 2007 , with which the first attempt was made to “gain a critical overview of the development of poster art in the GDR”. The catalog that was published at the same time is now regarded as the standard work on GDR poster history.

Poland

The Polish poster school - with Jan Lenica as its best-known representative - delivered loosely designed, often cryptically surreal results in about the same period.

Switzerland, USA

In the first three to four decades after the end of the war in 1945, various styles produced remarkable posters; however, they only had a limited influence on the overall situation of poster creation. From the early 1950s onwards, monumentally conceptual posters and anecdotal and humorous solutions came from Switzerland; The leading figure here was Herbert Leupin , who later switched from suggestive object representations to a freer, painterly style. A style variant came from the USA around 1970 that propagated a youthful counterculture and its music and summarized influences from Art Nouveau, Surrealism , Op Art and Pop Art under the heading “Conceptual Image” ; here the New York “Push Pin” studio with Milton Glaser was in the foreground.

International typographic style

The internationally most important poster style of the post-war decades, however, became a direction which, according to its origin and its characteristics, was given the designation “International Swiss Style” or “International Typographical Style”, or “Swiss Style” for short. In Switzerland - a small country with three main languages in which communication across language barriers is an absolute necessity - a graphic style developed at design schools in Zurich and Basel that corresponded to the requirements of the incipient globalization . Firms and organizations operating supranationally needed a supranational identity, a system of generally understandable words and symbols. The “Swiss style” used strict rules of composition based on mathematical grids, preferring black and white photographs instead of illustrations and strong typographic elements with partly newly developed fonts such as “ Helvetica ”, which was introduced in 1957. This international style had its American center in the Yale School of Design , New Haven (Connecticut) , which was closely connected to the Basel Design School.

Current situation

In the 1970s and early 1980s, the “Swiss Style” lost its influence. His results were now often perceived as cold and dogmatic. In Switzerland again, some chaotic-looking, playful, experimental posters with typographical material were created. One of the initiators of the movement was Wolfgang Weingart , a teacher at the Basel School of Applied Arts . As a result, new international trends developed under terms such as " Postmodern Design", "Memphis" or "Retro". A clearly dominant direction has not prevailed since then, at best relatively short-lived trends, triggered for example by spectacular new developments in computer graphics or particularly effective new characters.

Literature and research

Even in the phase of “Postermania” or “poster movement” in the 1890s, the poster was the subject of serious consideration. An initial analysis comes from the French historian and art critic Roger Marx , who also wrote forewords for the poster folders, which were popular at the time, and formulated in 1896: “In order to be more persuasive and convincing, advertising has put art in its service; […] Everyone was able to follow the metamorphosis. The previously less seductive poster with the ugly, difficult-to-read font has turned into a real graphic, which delights the eye with its multicolor and whose symbolism is also understandable ”. In addition to various publications in France, books, special magazines and articles in magazines on the subject of posters have appeared since the 1890s in the USA, England and Belgium and - with a slight delay - also in Austria.

In Germany, too, exhibition catalogs and magazine articles provided information on the subject early on. A fundamental work was “The modern poster” by the art historian and museum director Jean Louis Sponsel , which was published in Dresden in 1897. The author emphasized his conviction of the democratic and educational significance of the new medium: “The poster in its new form is perhaps the most powerful agent in educating the people to feel and need for art.” A characteristic of the early publications was that they were themselves approached their subject matter very subjectively. Apart from general considerations, the authors - journalists, art writers and collectors - usually only found ratings such as "decorative", "beautiful" or "repulsive" for the individual posters. This only changed when the client and graphic artist began to grasp the subject theoretically from their point of view. In 1909 a book by the economist Viktor Mataja was published in Munich and Leipzig , which soon became a standard work: “Die Reklame. Advertising and Advertising in Business ”. It says: “The merchant wants to attract the public with his announcements, but not educate them, he wants to advertise his goods, not new styles .” And the very successful poster artist Julius Klinger stated in the 1913 yearbook of the German Werkbund , “that we do not create eternal values, but only undemanding work that is naturally subject to the fashion of the day. "

The Berlin magazine Das Poster , published between 1910 and 1921 by the Verein der Posterfreunde ( Association of Poster Friends) , familiarized practitioners and collectors with the principles and examples of contemporary poster advertising. Its editor-in-chief , the poster collector Hans Josef Sachs, compiled a bibliography on the subject of "Writings on the art of advertising" in the third volume of the "Handbooks of Advertising Art " in 1920 ; his listing of 782 books and articles proves the intensive publication activity in this area. In the period between the First and Second World Wars , the poster was still considered the most powerful tool in commercial advertising and political agitation . The specialist literature was correspondingly extensive . Outstanding in the German-speaking area was a historical study from 1924: Advertising art from two millennia by Walter von zur Westen. Also in 1924, the first issue of the trade journal Nutzgraphik appeared in Berlin , subtitled “Monthly for the Promotion of Artistic Advertising”.

With the increasing social importance of advertising, dealing with its potential effects has become more professional. New professions and "advertising science" institutes emerged, and technical issues were analyzed in numerous publications. A typical example was the study of poster calibration . How to choose effective advertising posters that appeared in Berlin and Hamburg in 1926. In the foreword, the author Hans Paul Roloff referred to the expedient attitude of American advertising professionals: “For us, the development of new advertising methods is still essentially an 'art', a matter of feeling, at best of years of experience: in America it is one Science, a matter of the most sober calculation, of the most exact experiment. "

The loss of importance of the poster in comparison to the new media - television, and later also the Internet - has led to an increasingly retrospective approach since the late 1950s . The poster has now been recognized as a historical source, according to a forecast that Julius Klinger had already formulated in 1913 when he spoke of posters based on the “fashion of the day”. He went on at the time: "But we have a modest hope that our work will perhaps one day in 50 or 100 years be strong cultural documents [...]" Historians took up the subject. In 1965, Hellmut Rademacher published his extensive work “Das deutsche Plakat. From the beginning to the present ”and“ German poster art and its masters ”. In summary, the author wrote: "As a source of historical knowledge, as an object of aesthetic enjoyment, as a vivid expression of developing social consciousness, the poster plays an important and actually irreplaceable role". Finally, in the 1970s in Germany, through the collaboration of the major poster collections, an extensive inventory catalog was created under the title The early poster in Europe and the USA - an important, sustainable working basis for authors, exhibition organizers, illustrators and museum experts.

Sachs poster collection

The Berlin Jewish dentist and committed poster collector Hans Sachs , who founded the Verein der Posterfreunde in 1905, put together a collection of around 12,500 posters and 18,000 small-format commercial works between 1896 and 1938. They included depictions by well-known artists such as Henry van de Velde , Wassily Kandinsky , Käthe Kollwitz , Max Pechstein and Otto Dix . After the Second World War , the collection was considered lost, and Sachs received compensation from the Federal Republic of DM 225,000 . In the mid-1960s, part of the inventory reappeared in the GDR's Berlin armory . Around 4,300 pieces from the original poster collection have been in the German Historical Museum Berlin since the 1990s . Peter Sachs, the collector's son, who lives in the United States , has asked for the collection to be returned. The “Advisory Commission for the Return of Cultural Property Stolen by National Socialist Persecution”, chaired by the former constitutional judge Jutta Limbach , spoke in 2007 for the collection to remain in the Historical Museum. Deviating from this vote, the Berlin Regional Court decided on February 10, 2009 that the collection should be returned to Peter Sachs. According to lawyers, this ruling could have far-reaching consequences for an initially immense number of comparable proceedings. On March 6, 2009, Minister of State for Culture Bernd Neumann announced that the Federal Republic would raise an objection because of the fundamental significance of the judgment. On March 16, 2012, the Federal Court of Justice ruled that the Sachs family was still the legal owner despite compensation that had been paid in the meantime.

In implementation of the above judgment and after the objection was rejected, the heir Peter Sachs got the collection back in October 2012. He is planning an auction in three parts. In January 2013, the first auction by the New York auction house Guernseys for 1,200 posters brought in a sum of 2.5 million dollars. At this auction, the DHM bought back 31 pieces for around 50,000 euros and shows them in its exhibition Around the World .

Poster formats

Germany and Austria

In Germany and Austria the poster formats are designated in sheets , whereby one sheet corresponds to the paper size DIN A1. For example, 1 sheet high denotes a poster the size of a superscript sheet in DIN A1 format, 4 sheets across is a poster with four sheets A1 horizontally, two on top of each other and next to each other.

The classic advertising pillar can accommodate posters in the sizes 1/1 to 8/1 sheet. Advertising pillars are either occupied by several advertisers at the same time (general point) or only by one advertiser (full pillar). The formats here are 4/1 and 8/1 sheets, sometimes 12/1. Occasionally, however, you can also see 4/1 and 12/1 posters, as well as so-called all-round stickers, where a subdivision into single units is no longer recognizable, but the entire column represents a motif.

City light posters (format: 119 cm × 175 cm, often at bus stops) are printed in one piece and hung in the showcases . Since the showcases are standardized, only the 4/1 arch is possible. Due to the showcase frame, there is a difference between the printed format and the visible format, which must be taken into account when creating.

On large areas and mega-lights , 18/1 sheets are usually used, which corresponds to a width of 3.56 m and a height of 2.52 m (around 9 m²). In Austria, the 16/1 (3.36 m × 2.38 m) and the 24/1 sheet format (5.04 m × 2.38 m) are in use. Due to its widespread use, the large-format board is suitable as a medium for national advertising campaigns. There are also large areas that are used as general points, i.e. by several advertisers at the same time. The posters are then 1/1 sheet size and are often glued in a checkerboard pattern, i.e. a customer poster and a sheet of waste or lining paper alternating.

City lights (portrait format) and poster lights (16/1 or 24/1 sheets, landscape) have been used in Austria since around 2005 as poster changers in heavily frequented places. A translucent film with a sequence of 2 to 8 subjects is wound up on a thin roll and is gradually rewound onto a second one in a certain rhythm, so that each image can be seen standing for 20 to 30 seconds before it quickly moves up or down again .

Newly developed variations for city lights are the installation of a recorded LCD screen on a small sub-area - active light , formation of a window with three-dimensional content - frame light , free, updatable data offer via Bluetooth to mobile phone users - interactive light or design of the border or also further surroundings (e.g. entire wall of tram stops) to reinforce the advertising message.

Switzerland

In Switzerland, the formats F200 city format (116.5 cm × 170 cm), F4 world format (89.5 cm × 128 cm), F12 wide format (268.5 cm × 128 cm) and the new F24 large format (268 , 5 cm × 256 cm).

The culture formats F1 (50 cm × 70 cm) and F2 (70 cm × 100 cm) are standardized for small posters.

See also

- Outdoor advertising

- Election poster

- Les maîtres de l'affiche , contemporary poster collection 1895–1900, ed. by Jules Chéret

- Wooden letters

- Double wall poster

literature

- Josef Müller-Brockmann : History of the poster. Phaidon Press, 2004, ISBN 978-0-7148-4403-9 .

- Fons Hickmann , Sven Lindhorst-Emme (eds.): Berlin attack - Zeitgeist medium poster. Verlag Seltmann + Söhne, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-944721-56-9 .

- 100 best posters, NO ART - NO ART. With texts by Gabriele Werner, Fons Hickmann , Niklaus Troxler . Verlag Hermann Schmidt 2006, ISBN 978-3-87439-703-2 .

- Franz-Josef Deiters : Pictures without a frame. On the rhetoric of the poster. In: Joachim Knape (Ed.): Medienrhetorik. Attempto, Tübingen 2005, ISBN 3-89308-370-7 , pp. 81-112.

- Bernhard Denscher: Diary of the Road. Österreichischer Bundesverlag, Vienna 1981, ISBN 3-215-04576-1 .

- Hermann Junghans, Friedrich Dieckmann, Sylke Wunderlich (publisher: Landeshauptstadt Schwerin): Pasted over - posters from the GDR. cw Verlagsgruppe, Schwerin 2007, ISBN 3-933781-59-0 .

- Johannes Kamps: poster. Niemeyer, Tübingen 1999, ISBN 3-484-37105-6 .

- Museum of Arts and Crafts Hamburg. Jürgen Döring (Ed.): Poster Art. From Toulouse-Lautrec to Benetton. Edition Braus, Heidelberg 1994, ISBN 3-89466-092-9 .

- Heinz-Werner Feuchtinger: Poster Art of the 19th and 20th Century. Schroedel, Hannover 1977, ISBN 3-507-10225-0 .

- Gabriele Huster: Wild freshness. Sweet temptation. Images of men and women on advertising posters from the 1950s to 1990s. Jonas Verlag, Marburg 2001, ISBN 3-89445-286-2 .

- Klaus Staeck, Klaus Werner: Posters. Steidl, Göttingen 2000, ISBN 3-88243-748-0 .

- Steffen Damm, Klaus Siebenhaar: Ernst Litfaß and his legacy. A cultural history of the advertising column. Berlin 2005, ISBN 3-936962-22-7 .

- Uwe Clever: Outdoor technology advertising: posters in 3D. In: German printer. 30, 2004, p. 15.

- Thierry Favre: Railway posters. Hirmer Verlag, Munich 2011, ISBN 978-3-7774-3771-2 .

- Joachim Felix Leonhard u. a. (Ed.): Media Studies. A manual for the development of media and forms of communication. 2nd subband. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin 2001, ISBN 3-11-016326-8 .

- Jürgen Lewandowski: Porsche - The racing posters. Delius Klasing Verlag, Bielefeld 2008, ISBN 978-3-7688-2515-3 .

- Paul Wember: The youth of posters. Scherpe Verlag, Krefeld 1961, DNB 455457700 .

- Uwe Loesch : Nonetheless - posters by Uwe Loesch. Verlag Hermann Schmidt, 1997. ISBN 978-3-87439-425-3 .

- John Foster: New Masters of Poster Design. Rockport Publishers 2008 ISBN 978-1-59253-434-0 .

- Artist posters for the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. From the edition of Olympia 1972 GmbH, 1st edition (35,000 copies). Works by Friedensreich Hundertwasser , Alan Davie , Peter Philipps , Paul Wunderlich , Valerio Adami , Jacob Lawrence and others.

- Karolina Kempa: Polish Culture Posters in Socialism. An art-sociological study on the (meaning) interpretation of the work of Jan Lenica and Franciszek Starowieyski. Wiesbaden 2018.

Web links

- The poster - Art and Propaganda in the Spanish Civil War on the website of the German Historical Museum

- Essay about the artist poster (private site)

- "Poster archive - 100 best posters, Germany, Austria, Switzerland"

- originalgrafik.de to the artist poster

Individual evidence

- ^ Hermann Junghans, Friedrich Dieckmann, Sylke Wunderlich (publisher: Landeshauptstadt Schwerin): Pasted over - posters from the GDR. cw Verlagsgruppe, Schwerin 2007, ISBN 3-933781-59-0 , pp. 6-7.

- ↑ a b Jörg Meißner (ed.): Strategies of advertising art. Catalog for the exhibition of the German Historical Museum Berlin, 2004. Druckverlag Kettler, Bönen 2004, ISBN 3-937390-22-7 .

- ^ Article from the Swiss National Library: History of the Swiss Poster, Das Sachplakat: 1920–1950 , accessed in December 2014.

- ↑ Description of the “Berlin poster from 1910” in the article about the poster on Advertising-Art.de, accessed in December 2014.

- ^ Section History of Poster Advertising p. 213f and p. 220 of the book Historical Sources in DaF-Lessons , edited by Marc Hieronimus at Universitätsdrucke Göttingen, 2012

- ↑ a b c d e Bernhard Denscher: Pictures and words. Scientific research and literature on the history of poster art.

- ↑ Hermann Junghans, Friedrich Dieckmann, Sylke Wunderlich: Oversticked - posters from the GDR , pp. 11-13.

- ^ Hermann Junghans, Friedrich Dieckmann, Sylke Wunderlich: Pasted over - posters from the GDR. P. 9.

- ^ Poster for the exhibition Most Beautiful Books from All Over the World , 1968, in the Old Town Hall in Leipzig , accessed on July 27, 2018.

- ^ Hermann Junghans, Friedrich Dieckmann, Sylke Wunderlich: Pasted over - posters from the GDR. P. 6.

- ↑ a b Sachs poster collection auctioned , accessed on July 28, 2018.

- ^ German Historical Museum loses poster dispute. on: ZEIT-online. February 10, 2009.

- ↑ File number: Federal Court of Justice V ZR 279/10

- ↑ The Federal Museum has to release Nazi-looted art on: ZEIT-online. March 16, 2012.

- ↑ Berlin is buying back lost poster treasure. on www.bz-berlin.de; accessed on July 28, 2018.