Koenigsborn salt works

The Königsborn saltworks was a saltworks founded by the Prussian state in 1734 in what is now the Königsborn district of the Westphalian city of Unna .

Unnaer salt works as the forerunner of the Königsborn salt works

Salt works before the 17th century

The oldest professional salt production in Unna's been for the Salt Square to Brockhausen in 1389 documented occupied. Count Engelbert III. In the earliest document that has been received, von der Mark describes the “Sälzer zu Brockhausen” as “our Sälzer”. The two Unna salt works, Alter Platz der Erbsälzer (Hessenplatz) and the salt works operated by the von Rödinghausen family, have been documented by sources since 1489. The founder of the Rödinghauser plant was the Unna judge Evert von Buttel . Von Buttel was enfeoffed in 1487 by the Essen monastery with the Walravengut zu Brockhausen to service man's rights . The salt fields Westkamp and Übelgönne were under Buttel's direction. In addition, in 1489 , Johann II , Duke of Kleve and Count of the Mark, enfeoffed the Erbsälzer zu Brockhausen with the same rights to extract salt. While the Rödinghausen salt works was finally given up after 40 years of operation due to the lack of boiling brine, Hermann von Rödinghausen and Winold von Büren rebuilt the Übelgünner salt works in 1587. In addition, the Brockhausen Erbsälzer's boiling rights continued to exist.

Von Rödinghausen and von Büren subsequently modernized the salt pans that were under their control by building a completely new salt works and converting the previous wood-burning system to heating with hard coal from Dortmund and Hörde . As Leeck explains in more detail in his work (2007), this bourgeois-entrepreneurial intervention by von Büren became a classic example of a private modernization push in the saltworks at the end of the 16th century. In view of the economic and technological emergency, no solution was to be expected from the traditional pensions. In addition to the sovereign, private individuals represented one of the two possible sources of money for modernizing investments, for example in Sooden a. d. Werra.

It was above all the rising prices of firewood that reduced the profitability of many salt works and often even brought the salt works to a halt. Domestic firewood prices turned out to be a competitive disadvantage, especially when compared to the increased imports of sea salt from the Netherlands .

Unnaer saltworks in the 17th century

Between 1600 and 1625 von Büren provided the necessary capital for the construction of the first graduation tower .

As a result of the Klevian War of Succession (1609–1613) and in the course of the first years of the Thirty Years War , the Unna salt pans ran into economic difficulties for a short time. The increased import of cheaper sea salt from the Netherlands made matters worse . Only when Spain, which was involved in the war, severely disrupted the supply of salt from the Netherlands by blocking the mouth of the Rhine in 1625, did Unna improve again.

It cannot be proven whether the Brockhausen brine was exposed to war damage similar to that of the salt pans in the rest of northwest Germany - for example Lüneburg , Münder , Rhüden , Heyersum , Salzhemmendorf , Westernkotten and Werdohl - including attempts at sabotage by French troops (French salt pans were supposed to open up new sales markets).

The year 1631 marked the first attempt by the Brandenburg-Prussian state to firmly integrate the Unna saltworks into the fiscal policy of the state as a whole. Around 1631/32 Diedrich von Diest was appointed mountain governor and mountain master by electoral appointment . The electoral patent provided him with extensive mining and administrative powers to consistently claim the salt tithe from the existing salt works . The low political and military potential of the Brandenburg-Prussian electors, however, was not sufficient until the end of the 17th century to exert a lasting influence on Unna's saltworks.

During the French invasion of the Mark in 1672, the entire saltworks was destroyed after the city of Unna refused to allow the French military under Marshal Turenne to enter. When Diederich von Büren asked the elector in a petition to grant reconstruction aid in the amount of 2,000 to 3,000 Reichstaler , this was refused for lack of funds.

Only with the unification of numerous salt sites under a new owner did the saltworks at Unna take off again.

For the year 1689 it is documented that judge and court judge Balthasar Caspar Zahn , judge of Unna, initially received lease and then ownership of large parts of the Unna salt works. With the state protection against foreign competition, he saw good profit opportunities from the salt production near Unna and in the 1680s he acquired all the salt works there through inheritance, purchase and lease. During his lifetime , salt was recovered from the Alten Platz (Hessenplatz) , the Westfalenplatz and the Bürenplatz (both places on the Übelgünne ) and a Prumens Pütt .

Immediately before the beginning of the 18th century, the Brandenburg-Prussian state, which was now exclusively legitimized in its western provinces, began to regulate and nationalize the saltworks and salt trade of the County of Mark as part of its mercantilist - cameralist economic policy . Since 1690 there have been increasing attempts by the electoral government to question the rights of the Sälzer families, especially the Zahn family, derived from property ownership, and to assert overarching regal rights. Although another attempt to shake Zahn's legal position failed again in court in 1693, the government pursued its goal until the 1720s.

At the same time as the legal dispute, the Brandenburg-Prussian authorities, above all the rent master Johann Wilhelm Ernst , harassed the Zahn operators while they were overseeing their duties as operators of the salt works. The factories always had to be in perfect condition, production fully guaranteed, and the salt tithes had to be delivered in full on time. Any business interruption had to be justified in the smallest detail to the authorities. This procedure was based on the medieval legal principle that the sovereign, according to the mining law provisions of the Golden Bull , could move in a lent, but not operated salt works at any time and reassign it.

With the end of the naval war between France, England and Holland in 1697, the import of cheaper Dutch and Electoral Cologne salt into the county of Mark began again in full and led to the temporary closure of the entire Zahn factory due to the considerable competition.

Unnaer saltworks at the beginning of the 18th century

With the death of Frederick I and the accession of Friedrich Wilhelm I , the three-way conflict between entrepreneurs, state and central government entered a new phase.

In the course of the state restructuring by the new king, new administrative bodies were created - above all the 4th Department of the General Directory and the War and Domain Chamber in Kleve . In enforcing the monopoly and import ban , they had to struggle with the strong influence and considerable resistance of the Klevisch-Brandenburg estates, but in particular with the opposition of the aristocratic houses of the Brandenburg region. The attitude of the Brandenburg nobility in this matter reveals the close economic ties between the county of Mark and its neighboring states and their dependence on the free purchase of raw materials and the unhindered export of finished goods. In addition, both the sovereign and the central government had to recognize that the officials deployed there were more likely to pursue their own regional economic interests than the officials of the core provinces, who had long since made the step into unconditional absolutist subordination. It was only with the consolidation of the new state apparatus during the late reign of Friedrich Wilhelm I that the state, under direct pressure from the king, took all the administrative means in the western provinces.

On the one hand, the central government pursued the goal of bringing about a significant increase in state revenues through the salt tithing , and on the other hand, against the background of a mercantilist foreign trade policy, to ensure the basic supply of salt for the people of Brandenburg through their own production in the country. Due to its brine and the resulting capacities, the Zahnsche Saline zu Unna was well suited to ensure the security of supply in the Klevian, Brandenburg and Ravensburg areas. Therefore, the new, much more energetic sovereign forced the entrepreneur Zahn, referring to the Golden Bull in 1717, to resume operations. Six years later, with a new decree on the salt monopoly, the king emphasized the ban on the import of foreign salt into the county of Mark.

The treatment of the Zahn entrepreneurial family by the Brandenburg-Prussian authorities revealed a very ambivalent state understanding of entrepreneurship and its economic risks: On the one hand, the Brandenburg-Prussian state was very keen to sell privately operated works over the salt shelf and the mining law provisions of the Golden Bull in to transfer state property, whereby he hardly left untried legal steps. So Zahn had to prove the legality of his claims to the salt pans again. On the other hand, the state authorities shied away from the entrepreneurial risk, especially the barely calculable risks of salt production, and quickly leased the nationalized salt works to private entrepreneurs or left it to the privately operated continuation of a salt works, albeit by not very profit-oriented officials.

It is therefore not surprising that Zahn has meanwhile offered his salt works to the Prussian government for sale several times in vain. Ultimately, he was forced to continue operations under unfavorable conditions and even expand it due to government supply requirements. Zahn came under increasing pressure from the sovereign requirements, from the threatened total loss of the plant if the company ceased operations, from lost sales proceeds, from increasing competition from the Netherlands and Kurköln as well as from an obstruction policy of the royal-Klevian government against the import ban issued by the Berlin central government more in economic distress. Finally, in 1731 the General Management sent the salt factor Christoph Dove to Unna in order to obtain a neutral assessment of the salt works through his expert advice. His verdict was clear: Dove advised buy it now.

Since a procedure initiated by the skeptical Prussian administration for the legal clarification of ownership was still pending, the General Directorate concluded a six-year supply contract with Zahn on February 26, 1732 to supply the county of Mark with salt for the period from July 1, 1732 to July 1 1738. In it, Zahn undertook to supply the county with the necessary amount of 350 loads of 60 Berlin bushels of salt each on behalf of the state and to consent to the sale of the salt works to the Prussian government after the delivery contract had expired. At the same time, on June 17, 1732, the General Directory again issued a ban on the import of foreign salt . If the Brandenburg subjects did not buy the prescribed amount of salt, the central government authorities automatically assumed that foreign salt had been bought and consumed and imposed draconian fines and imprisonment. At the same time, the General Directorate accused the councilors of the Klevian government and the War and Domain Chamber in Kleve of their abduction tactics and threatened to hold them liable with their personal assets for losses in the salt budget resulting from the failure of the salt tithe. It was only after this threat that the Chamber in Kleve imposed heavy fines on the town of Iserlohn , the parish of Rellinghofen , the court of Hemer , the town of Unna and the farming communities in Niedermassen, Afferde , Uelzen and Obermassen for violating the import ban in 1735 . Foreign salt carts were punished by the confiscation of the wagons and the sale of the salt, horses and wagons.

As tooth mid-1730s, neither in terms of quality nor quantity has been able to fulfill the treaty of 1732, and economic sanctions from abroad in response to the mercantilist policy of Prussia the economic situation in Brandenburg-Prussia intensified, to saw the Brandenburg-Prussian salt management forced to partially allow the import of Dutch salt again. In addition, it used the salt pans in Werdohl and Sassendorf to supply the county with sufficient quantities of salt.

Against the background presented above, the central government now saw the cooperation and probably also the experiment of a purely privately organized salt production and supply of the western province with salt as finally failed and decided to build a state salt works, which from now on supplies the county of Mark with salt had to take over.

The state "Saline Königsborn"

While a search for brine springs carried out by the Prussian authorities in the Bochum, Wattenscheid, Hagen and Hattingen area was unsuccessful, boreholes carried out by the Prussian state between 1732 and 1735 north of the gates of Unna brought the hoped-for success. In 1734 a well was excavated, which was named Königsborn (the king's well) in honor of the Prussian King Friedrich Wilhelm I. A first trial settlement was carried out in the same year by the Klevian war and domain councilor Francke and by the Wettin war and domain councilor Richter. The positive result was the beginning of the eventful history of the state saltworks Königsborn :

Privately run salt works from 1734 to 1745

After relatively short contract negotiations with the financially strong Mayor of Iserlohn and entrepreneur Johann Caspar Lecke , he pledged to the Prussian state to build the Königsborn saltworks, which would remain in state hands , to supply the Sauerland with 350 loads of salt annually and to transfer ownership of the plant back free of charge after completion the contract period of nine years to the owner, i.e. to the Prussian state. As part of this lease, the General Management gave him the formal management of the private business in February 1734. In return for each load of salt, Lecke received - like the entrepreneur Zahn previously - 33 Reichstaler from the Prussian state. Berlin provided the salt springs on the Nettelkampschen estates in the immediate vicinity of Zahn's salt works for the sinking of the “Königsborn” brine fountain, which initially had a brine with a salt content of six solder . The property rights to these sources of salt had the General Directorate recently secured by a civil process. The Prussian sovereign remained the owner of the Nettelkamp property.

Since Lecke had no knowledge and experience in the field of the construction and operation of salt works and his contribution to this joint venture between private and state investors was more limited to the capital, it can be assumed that Lecke was a speculator who hoped for quick profit from this early form of public-private partnership . Apparently he had no idea that his obligation to start-up investments and personal entrepreneurial liability in this rigidly state-directed project would mean more disadvantages than big profits in the medium term.

In addition to the aforementioned officials, Francke and Richter, who had overseen the salt works in Halle and Schönebeck for several years , the Prussian officials Christian Scholl from the Wettin Mining Authority, who were also familiar with mining aspects, and Bergrat, who was later also dispatched from the Wettin Mining Authority, took on the professional promotion of the Königsborn salt works August Heinrich Decker. The previously mentioned former salt factor and now Brandenburg salt inspector Christoph Dove took over the actual business management of the Königsborn saltworks .

The overall management - if this includes not only the management of day-to-day operations, but also medium and long-term planning tasks and decisions - was also the responsibility of the General Management, which, in keeping with the mercantile-cameralistic economic policy, reserved the right to intervene directly in the salt works' investment decisions .

When complaints about the bad condition of the new salt works increased, so that there were concerns that an unprofessional work would endanger the salt production and thus the salt monopoly, Berlin suspected that “out of all circumstances it appears that the leak is no match for the plant and it with the same wholeheartedly and not at all go well ” , and demanded “ that rather the boiling in the Royal Salt Works should be intensified in every way in such a way that the dental salt is no longer necessary in time. ”

The drop in the brine content and the subsequent complaints led to the fact that Lecke had to build a first graduation house in 1735/36 in order to be able to switch from the straw grading, which contaminates the boiling brine, to the cleaner form of the thorn graduation . When the contract of the Prussian state with the entrepreneur Zahn expired in 1738 and the Koenigsborn saltworks were transferred from the General Management to supply the entire county of Mark with salt, this decision by the Berlin central government meant that Lecke had to increase from four to eight boiling houses, each with a simmering pan double the annual target of 600 loads of salt.

After the salt supply and the salt monopoly in the county of Mark seemed to be guaranteed by the Königsborn saltworks , the General Management decided to also introduce the salt monopoly in the Lower Rhine duchies of Kleve, Geldern and Moers and to transfer part of the salt supply there to the Königsborn saltworks . These central government decisions meant that by mid-1740, Lecke had to do everything possible to create the operational, technical, infrastructural and, in particular, financial measures.

The General Direction assumed a total annual requirement of 1,000 loads of salt for the western provinces. 500 burdens were accounted for by the county of Mark, 500 burdens on the duchies of Kleve, Geldern and Moers. In this context, on November 22nd, 1740, the General Management issued the “patent that no foreign salt could be introduced into the Clevian and Märkische Lands” . This unpopular measure can be attributed to the fact that the originally targeted sales price of 55 Reichstalers per load of salt, which would have been below the price for Dutch sea salt , could not be maintained due to high production and transport costs (Unna - Wesel). Eventually the price leveled off at a proud 76 Reichstalers, which triggered considerable (futile) protests from the local population.

The fact that Lecke (presumably 1738) had agreed to extend the original nine-year term of his lease (1734–1743, see above) to June 1744, he is likely to add in view of the substantial investments that he has actually been forced to make (his contractually promised entrepreneurial liability left him no other choice) have regretted the running costs afterwards. Expectation of profit and distribution of liability in no way correspond. In 1740, after deducting the operating costs and the salt tithing (salt tax) from its gross profit, Lecke only had a modest net profit of 2,925 Reichstalers. In contrast, this early form of public-private partnership seemed to be paying off for the Prussian state - after all, in the same year it was able to post 15,750 Reichstaler on the income side of its salt budget.

After Lecke was finally given the responsibility of promoting the salt works (presumably to relieve the Prussian staff budget), an official investigation report revealed that the production costs per unit of salt had been found to be significantly lower than Lecke stated in his calculations for setting the state-administered purchase price. Against this background, the Prussian government was no longer willing to pay the 26 Reichstaler per load of salt demanded by Lecke. Rather, it initially estimated a purchase price of 20 thalers before in February 1742, forcing Lecke to sign a new contract in which the latter undertook to deliver 1,000 loads of salt for the annual supply of Mark, Kleve, Geldern and Moers at a purchase price of now only 19.5 Reichstalers. With this contract an even longer term until 1750 was fixed.

As a result of further official investigations, Lecke was accused of considerable economic and technical deficiencies in its management: Lecke ran the Königsborn saltworks at random without any operating plan and the salt boil was also very unprofessional. Lecke, on the other hand, blamed a significant decrease in brine content for the steadily deteriorating operating results. He demanded financial compensation from the Berlin central government for the difference between the purchase price of 19.5 Reichstalers and the production costs per load of salt he estimated of 33 Reichstalers, otherwise he would assert the loss of the business basis and the (gagging ) Withdraw from the contract.

The General Directorate in Berlin mistrusted the information provided by the company Lecke, who was officially found to be incapable and ignorant, and sent the Prussian tax council Karl Joachim Krusemarck and a neutral grading master from the Landgraviate of Hesse-Kassel to conduct a detailed investigation . Both confirmed the information leaked about the decreasing brine content.

While Lecke was getting closer and closer to its economic ruin due to the low purchase price (19.5 Reichstaler) with falling annual production (max. 600 to 700 instead of the 1000 loads of salt to be provided), the Berlin central government saw the overall supply of the western provinces, the stability of the salt trade monopoly and import ban and thus the increasingly important salt budget in danger. To make matters worse, the other salt works in County Mark, i. H. Sassendorf, Werdohl and, above all, the Zahnsche Saline, oppressed by the state saltworks in Königsborn , now saw the time to take revenge for the rigid “salt policy” of the Prussian state by refusing the state salt monopoly the amount of salt that was now missing.

While the Prussian government had to buy 200 loads of Dutch sea salt out of sheer necessity and even concluded a delivery contract with a Dutch merchant for a period of twelve years, Lick was finally on the verge of ruin, as the central government in Berlin, cynically pointing out its contractual liability for any kind of damages the years 1743 and 1744 declined. After all, the government, which now had to operate the “Saline Königsborn” entirely on its own, released the bankrupt entrepreneur Lecke from all contracts, which, however, was too little consolation in view of his personal loss of 17,000 Reichstalers.

Fiscal operation from 1745 to 1750

The inevitable decision by the Prussian government to operate the Königsborn saltworks under sole state control from 1745 represented a decisive turning point in the Unna saltworks.

A whole series of economic data on salt production showed that the most critical cost factors of the saltworks were personnel expenses (30%), fuel requirements (29%) and wages (26%). The general management in Berlin now had detailed profitability calculations made on a regular basis. The salt factory had the task of preparing detailed monthly reports on salt boiling (especially boiling costs), the salt content of the brines, the amount of coal used and the amount of salt extracted - an early commercial form of controlling, so to speak, with the central government in Berlin as the controlling body Recommendation of operational processes acted.

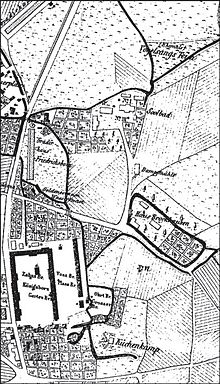

Under the supervision of the Klevian War and Domain Chamber, numerous excavations and speculations were made to set up new brine wells. The general directorate put the individual salt and mining officials in competition with one another in the search for new, more productive brines (a kind of “scheming early form” of employee motivation through internal competition). New sols were actually with 5-6½ percent in that time Lötigkeit found, so the already exhausted previous brines could be replaced gradually. A total of five new wells were sunk: "Missgunst" on Erbsälzerstraße (the name speaks for itself), "Klevischer Favorit" east of Vaersthausener Straße on Katernborn, "Glückauf" on Ludwigsborn, "Güldene Sonne" and "Friedrichsborn", named after the now King of Prussia Friedrich II . The saline was always operated at the upper limit of its capacity and efficiency.

Nevertheless, the Königsborn saltworks increasingly lost its value because the salt factory in Unna failed to reinvest in the outdated systems, especially in technical innovations to save fuel. As a result, their capital value sank from the previous 36,062 Reichstaler to 10,842 Reichstaler in just five years. The main reason was the restrictive salt budget planning of the Klevian Chamber in the short-sighted pursuit of a balanced budget, which made reinvestments considerably more difficult, if not even prevented. The Chamber of War and Domains did everything in advance obedience to achieve the annual profit planned at the green table in Berlin, which is not synonymous with making money. The need for investment, production security and future-oriented corporate management were perceived as disruptive factors by the determined civil servants. A major cause may have been the lack of personal incentives. After all, the civil service did not participate in the state profits. The latter looked rather modest in terms of effort. In five years of sole state management with an average annual output of 924 loads, a profit of 167,570 Reichstalers was recorded. Although the entrepreneurial saline activity of the state served in particular the general interest (here: sufficient salt supply), the fiscal profit could not be satisfactory. It may therefore be seen as wise that the General Management in Berlin decided against the above background to return to the leasing system in 1750.

Privately run salt works from 1750 to 1773

In 1750, the head of the salt industry at the Klevian War and Domain Chamber , Johann Bertram Arnold von Rappard , and the Brandenburg Baron Friedrich Ludolph von Torck von Nordherringen leased the Königsborn saltworks . In 1751, the Prussian King Frederick the Great entrusted them (and not Valentin von Massow , the Prussian Chamber President in Minden ) with the construction of the salt works and the establishment of the salt works in Melbergen / Rehme near Minden.

The lease contract for the Königsborn salt works ran from 1750 to 1765. The tenants committed themselves to an annual production volume of 1,000 loads of 60 Berlin bushels each. Once again, the General Directorate lowered the specified state purchase price in order to achieve higher income and fixed it at only 16 Reichstalers for the load of salt.

The entrepreneurial incentive for Rappard and Torck, however, was not, as with earlier tenants, in the salt boil to supply Kleve-Marck; Rather, the two new entrepreneurs had more lucrative foreign trade in mind. Due to his good technical knowledge and his position in the war and domain chamber of Kleve, Rappard saw sufficient sales opportunities for the Unnaer salt in Cologne , Trier and Frankfurt am Main as well as in the Bergisch area and in Siegerland . From 1750/51 to 1755/57 her personal profit from the salt export averaged a little less than 8,000 Reichstaler, of which the state received half under contract.

Rappard and Torck initially invested 19,650 Reichstaler and made extensive improvements, especially in terms of boiling technology, in order to be able to operate the company economically again. In order to generate the energy savings that had not been made up to now, they built another graduation house as well as two wind and horse arts for pumping the brine up to the graduation houses and replaced the old pans with nine boiling and fifteen broddel pans.

If the brine pumps had previously been laboriously and costly operated by human labor, this task was now carried out by the aforementioned horse arts and wind pumping stations . They obtained the coal they needed for boiling from the mines of the offices of Hörde, Hacheney , Himpental , Hombruch , Limburg , Renninghausen and Wichlinghofen . The general management in Berlin supported the expansion of the use of coal for boiling, which Rappard and Torck were planning, with a special coal transport regulation for the salt works near Unna. This ordinance was a direct subsidy from the state to cover coal needs, as it made individual mines and carters responsible for the saltworks free of charge or at reduced prices.

In addition, the Prussian state began to promote the Königsborn saltworks directly as part of its infrastructure policy. At the beginning of the 1750s, the road between Unna and Kamen was considerably expanded, as it was used for transport in the direction of Lünen , from where the Unna salt was then shipped on the Lippe in the direction of Wesel and Holland. The prosperous development of the Königsborn salt works under the tenants Rappard and Torck came to an abrupt end with the outbreak of the Seven Years' War in 1756. The war interrupted all investment projects. Furthermore, both tenants were only able to maintain the salt works with the help of the occupying powers France and Austria . All in all, the representatives of both countries were extremely cooperative towards the Königsborn saltworks . For example, the French General Maillebois issued a total of six so-called Sauvegarde letters by 1762 , which protected the salt works from destruction by French troops, while the Austrian war administration in 1757, despite the strained supply situation among its own units and the French allies, carried out warfare in the administrative districts of Unna , Hörde and Heeren interrupted to enable the salt works operators to deliver 1,200 wagons of coal to the salt works. It was precisely the negligent conduct of the Prussian administrative officials who stayed behind in the county of Mark during the war that the coal required for salt boiling was often not brought in on time, and as a result, boiling operations increasingly came to a standstill from 1760 onwards. Of the 24 boiling pans, 16 were no longer serviceable at the end of the war, numerous other boiling plants had rotted away and the damage to the salt works and tenants had run to 20,000 Reichstaler. After the war, King of Prussia Frederick II personally requested the rapid rebuilding and resumption of operations. In this context he referred to the great importance of the saltworks for the state revenue.

Reconstruction and recommissioning were now under the personal control of the king, which led to a swift and complete implementation of the royal will. Rappard calculated a financial requirement of 25,000 Reichstalers for the restoration. Although the lease provided for state compensation in the full amount of the war damage caused, the War and Domain Chamber in Kleve only granted him 12,000 Reichstaler compensation. Rappard, who had meanwhile lost all political offices and thus considerable income due to his criticism of the Prussian fiscal policy in the western provinces, it seemed wiser to be content with this severance payment in order not to lose the rent as income. As early as 1764, the Königsborn salt works with 18 pans was back in operation. Rappard and Torck immediately resumed exports to the Cologne area and Dortmund, and in 1764 they were able to generate a profit in the export business of 7,902 Reichstalers.

In 1765, various boreholes were carried out again, during which the "Ludwigsborn" and a graduation building of the same name were built as a new well. At the same time - the General Management had extended the lease contract with Rappard and Torck by twelve years from 1766 to 1778 at even more favorable conditions for the Prussian state - a hydraulic pressure unit supplied from England, a so-called water art , was used at the Königsborn saltworks for the brine to pump up. The total investment volume for both tenants was 22,000 Reichstaler.

In 1767 a renewed salt test register was introduced, the purpose of which was to better control the state's salt trade monopoly and salt import ban, which still existed. The aristocratic houses of the County of Mark were ordered to purchase salt books in which they had to enter the quantities of salt obtained from Unna or from the nearby salt works. At the end of each quarter, these books had to be submitted to the salt factory in Unna for review. The purpose of the test was to determine whether the amount of salt purchased corresponded to the size of their households. If the stipulated minimum quantity was not reached, the purchase of foreign salt was assumed. Drastic penalties were the result. From 1768 onwards, the Königsborn saltworks suffered more and more business interruptions because farmers and carters did not bring enough coal for the evacuation as part of their manual and clamping services. The interruptions in production increasingly caused deviations from plan for the salt budget. Finally, the General Directorate sent the Struve Secret Finance, War and Domain Councilor and the Stegemann Building Councilor to Unna to examine the facilities. Stegemann subsequently suggested increasing the salt content of the boiling brine to 15-16% solder, increasing the salt production to 1,800 to 2,000 loads of salt annually, reducing coal consumption to 2,600 wagons and reducing the production time to 10 months. That was the final end of the Königsborn saltworks in leaseholder hands. Rappard considered Stegemann's plans to be completely unrealistic based on his previous operating experience, feared that he should be asked to pay even more for the distribution of profits between the state and companies and, when he did not succeed in asserting himself against Stegemann at the General Management, asked for immediate cancellation of the lease. This was granted to him in 1773 against payment of 10,000 Reichstalers.

Once again the Prussian central government had ruined a private entrepreneur because of its ever expanding fiscal interests. For the period between 1750 and 1773 it can be said that the Prussian central government continued to feel committed to its already known mercantilist-cameralist principles. The deterioration in the lease conditions for the tenants Rappard and Torck is an eloquent example of the greed of the Prussian tax authorities, which on the other hand shied away from the entrepreneurial risk for another 23 years after the brief interlude between 1745 and 1750. In the years of their fairly uniform management, Rappard and Torck held both the technical and the subject-matter promotions and exercised them consistently to the advantage of the Königsborn saltworks . Although the Prussian state accommodated the two private entrepreneurs in these years with an extensive infrastructure policy and various subsidies in the field of coal supply and coal transport, these failed, apart from the (toggle) contract with the Prussian government, ultimately due to the still inadequate coal supply and the poorly developed road network in County Mark.

Fiscal operation from 1773 to 1800

In 1773, the Prussian state took over the Königsborn saltworks on its own and again made it a state-fiscal enterprise under the leadership of the Märkische War and Domain Chamber deputation in Hamm. The state immediately began with the expansion and renovation of the salt works according to the proposals of the building councilor Stegemann and between 1773 and 1780 invested 100,223 Reichstaler in the project. Despite this huge investment, which private entrepreneurs could hardly shoulder at the time, Stegemann's rationalization goals were not achieved. Nevertheless, numerous other expansions took place up to the beginning. Of the many technical innovations between the years 1775 and 1800 in the Königsborn saltworks , the construction of the fire engine ( steam engine ) in Unna-Afferde , initiated by the then Oberbergrat Freiherr vom Stein , should be mentioned as particularly outstanding . The system was a simple low-pressure machine and was put into operation on August 30, 1799 (it was not finally shut down until 133 years later, in 1932). The Königsborn saltworks now belonged to the top of the German saltworks. In addition to technical innovations, the Prussian state also carried out numerous infrastructure projects that were intended to provide the Königsborn saltworks with better sales channels and thus improved access to the markets. So the extensive expansion of the Ruhr for intensive transport shipping has now been pushed ahead. In particular, the Langschede - Witten section of the Ruhr , which was used almost exclusively to transport salt, was made navigable. For this purpose, the necessary locks at Herdecke , Wetter and Witten were started. In 1791, the Prussian state also began to expand the important road for the Königsborn salt works from Unna via Witten, Bochum and Essen to the Rhine . This extensive road construction project was completed in 1801. Much of the road follows today's Bundesstraße 1 .

It flourished as a saltwater spa in the 19th, declined in the 20th and last marks in the 21st century

With the increasing development of salt deposits and the expansion of the Königsborn saltworks into a health spa between 1800 and 1825, the place temporarily gained supraregional importance as Bad Königsborn . The first brine bath in Unna was the Luisenbad , a social and cultural center that was operated from 1818 to 1860 , which was also visited by the Prussian Crown Prince Friedrich Wilhelm . Another bath, which had initially only been operated for the saltworks employees since 1852, was expanded after the Luisenbad was closed and experienced a rapid boom after the so-called Königsborn union (see also Friedrich Grillo ) took over the saltworks . In May 1882 the old Kurhaus was replaced by a much larger one. The spa park and other spa facilities were also expanded. To meet the increased demand for brine, distant brine springs outside of Königsborn were also used. The Rollmannsbrunnen in the Kamener village of Heeren-Werve has been sunk since 1844 (pumping machine house still exists). Additional brine was pumped from Werries to the Koenigsborn spa via a roughly 25-kilometer-long cast iron pipeline .

Although salt production remained an important branch of the economy until the 1930s, the industrial extraction of hard coal also led to a profound structural change in Königsborn (see the articles " Zeche Königsborn " and " Ruhrgebiet "). After the salt content of the brine springs continued to decrease, the fire engine was finally shut down on June 7, 1932 and left to slowly decay. This was an unmistakable sign that the salt works would not be maintained for much longer. On December 31, 1940, the time had finally come. Even Bad Königsborn had as a medicinal and spa no more existence prospects were gone when the last Sole stocks are running low. On October 15, 1941, the spa was closed forever. During the Second World War , the spa park was a restricted military area, on which weapons captured by the Wehrmacht were stored under strict guard.

Considerations to try a new start after the Second World War by using brine deposits near Sassendorf near Soest were probably not implemented for economic reasons. The elongated salt boiling houses along Friedrich-Ebert-Straße with a total of 13 chimneys and the two saltworks grottoes in the spa gardens were demolished or blown up in 1946. The approximately one meter deep depression of the drained pond on the Monopteros was filled with the rubble . The dilapidated building of the fire machine in Unna-Afferde was completely demolished on July 18, 1964 to make way for a new residential area. Parts of the steam engine were saved in the Bochum mining museum and rebuilt as early as 1953 using a steam cylinder, the control and a reconstructed balancer. They are presented there together with a large model of the machine house. The spa park with a total of around 100,000 square meters was finally renovated by the previous owner, Klöckner-Bergbau Königsborn Werne AG , as a recreational green area and given to the city of Unna as a gift to the citizens of Unna. The last remains of the graduation tower could still be found in the 1970s in the form of “ saline stones ”, some up to half a meter high , wooden brushwood bundles enclosed by metallic and mineral deposits. Sometimes they were used as souvenirs, sometimes as building material for decorative masonry (such as property boundaries), so that no traces of the formerly numerous graduation towers can be found in public spaces. A few listed buildings today remind of the heyday of Bad Königsborn , especially at the former spa gardens of Königsborn.

In 2009 a successful test well was drilled to explore the brine deposits. The aim was to check the requirements for building a new graduation tower in the former spa park. However, the plans are controversial in terms of local politics because of the follow-up costs and the tight budget situation in the city of Unna.

See also

- Bad Dürkheim salt works

- Bad Sassendorf saltworks

- Saline divine gift

- Saline Luisenhall

- Rothenfelde salt works

- Salzkotten saltworks

swell

- ^ Franz Wiemers: The salt system on the Ems and Weser under Brandenburg-Prussia. A contribution to the history of the origins of the city of Oeynhausen. 1915. Münster, University, dissertation, 1919, section The construction of the Neusalzwerk by B. Rappard and v. Torck, hostilities with v. Massow, pp. 76-81.

- ↑ Brine fed up in the spa gardens . In: DerWesten. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- ↑ Resistance to a new graduation tower . In: DerWesten. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- Secret State Archive of Prussian Cultural Heritage (Berlin-Dahlem)

- I. Main Department, Rep. 34, Nos. 6d, 30c and 182d

- II. Main Department, General Directory Salt Department, Tit. XVI, Nos. 1, 3, 4, 6, 7 and 17

- North Rhine-Westphalian State Archives, Münster

- Principality of Paderborn, edicts, volume 9, sheets 144, 216, 267 and 404

- Graflich Landbergisches Archiv Imbsen, No. 14493

- Kleve-Mark Landstands, No. 161

- Kleve-Märkische Government, Landessachen, No. 1138

- War and Domain Chamber Kleve, No. 9, 14a, 15, 16, 17

- Paderborn state ordinances v. March 28, 1654 a. May 25, 1666

- Oberbergamt Dortmund, No. 1907

- Reich Chamber of Commerce, B No. 2147 and R No. 805

- From Romberg General Archives, No. 4892

- N. Schaten: Annalium Paderbornensium. 2 parts. Munster 1774/1775. Part 3 by M. Strunck: Annalium Paderbornensium III . Paderborn 1741.

- Westphalian document book. IV No. 2472

literature

- Klaus Basner: Unna - historical portrait of a city. Volume 1, Unna 2014, ISBN 978-3-944430-01-0 , Sections II.14 The Salt Works in Brockhausen, pp. 151–156; II.17.8 Salt War and Denominational War, pp. 182–184 (Author: Hartmut Hegeler ); IV.5 Die Saline, pp. 281–286; Volume II, Unna 2013, ISBN 978-3-9813452-9-2 , Section II.2 Saline and Kurbad Königsborn, pp. 131–135.

- D. Burgholz: Salt production and politics during the decline of the old saltworks. In: H.-J. Teuteberg (Hrsg.): Westphalian economy at the beginning of the "machine age" (= studies on economic, social and technological history. Volume 6). Dortmund 1988, pp. 247-267.

- K. Coerdt: From Asseln to Königsborn. The royal saline canal - a technical masterpiece. In: Yearbook of the Unna district. Volume 30. 2009, pp. 145-149.

- G. von Detten: Westphalian economic life in the Middle Ages. Paderborn 1902.

- R. Dietrich (Ed.): The political testaments of the Hohenzollern (= publications from the archives of Prussian cultural property. Volume 20). Cologne / Vienna 1986.

- H. Ditt: Structure and Change of Westphalian Agricultural Societies (= publications of the Provincial Institute for Westphalian Regional and Folklore, Series 1, No. 13). Munster 1965.

- E. Dösseler (Ed.): Süderländische historical sources and research. Volume 3. Werdohl 1958.

- E. Dösseler: The economy of the county of Mark under Brandenburg-Prussia 1609-1806. Contributions to the history of the medical system in the county of Mark and in the Märkisch-Lippischen condominium Lippstadt (= Altenaer contributions. Works on the history and local history of the former county of Mark. New series, volume 1). Altena 1961.

- H.-H. Emons, H.-H. Walter: With the salt through the millennia. History of white gold from prehistoric times to the present. 2., through Edition. Leipzig 1986.

- H.-H. Emons, H.-H. Walter: Old salt pans in Central Europe. On the history of evaporated salt production from the Middle Ages to the present. Leipzig 1988.

- M. Fessner: coal and salt. The long way to the industrial Ruhr area (= publications from the German Mining Museum Bochum. No. 73). Bochum 1998.

- Förderverein Kloster / Schloss Bentlage eV (Ed.): 1100 years of Bentlage. On the history of an old cultural landscape. Rheine 1991.

- W. Friday (Ed.): The Salt City. Old European structures and early modern innovations (= studies on regional history. Volume 19). Bielefeld 2004.

- R.-J. Gleitsmann: Shortage of raw materials and solution strategies. The problem of pre-industrial timber shortages. In: F. Duve (ed.): Technologie und Politik. Reinbek 1980, pp. 104-154.

- R.-J. Gleitsmann: Aspects of the resource problem from a historical perspective. In: Scripta Mercaturae. 15, No. 2. 1981, pp. 33-89.

- W. Grevel: Overview of the history of the salt works and the salt bath Königsborn up to the year 1873. Unna 1954.

- A. Hanschmidt: The 18th century. In: W. Kohl (Hrsg.): Westphalian history in three volumes and an illustrated and document volume. Volume 1. Düsseldorf 1983, pp. 605-685.

- M. Hart: Salt Tax and Salt Trade in the Low Countries. In: J.-C. Hocquet (Ed.): Le roi, le marchand et le sel. Lille 1987, pp. 293-312.

- V. Hentschel: Prussia's contentious history 1594-1945. Düsseldorf 1980.

- A. Huyssen: The brine springs of the Westphalian Chalk Mountains, their occurrence and presumed origin. Berlin 1856.

- W. Kaiser: The history of the company and the state influence in the salt industry in Hanover and Westphalia up to the end of the 18th century. Cologne 1938.

- W. Kliche: The shipping on the Ruhr and Lippe in the 18th century. In: Journal of the Bergisches Geschichtsverein. 37, 1904, pp. 3-19.

- J. Kloosterhuis: "... spoiled by villen Orteren von allerseidtz war folk ...". The consequences of the Spanish-Dutch War (1566–1609) for the county of Mark. In: The Märker. 32, 1983, pp. 125-132, 162-173, 200-211.

- J. Kloosterhuis: princes, councilors, subjects. The County of Mark, its local administrative bodies and the government of Kleve. In: The Märker. 35, 1986, pp. 3-25, 76-87, 104-117, 147-164.

- F. Knoke, FJ Ewers, J. Bürger (Ed.): City and Office Salzkotten. Paderborn 1970.

- SR Krause: "The richest and most productive mines in Grafschaft Mark". Pre-industrial coal mining in Gogericht Schwelm. Wuppertal 2002.

- C. Leeck: The introduction of technological innovations in the saltworks of the 16th century using the example of the Brockhauser salt works and the Sooden ad Werra saltworks. Munich 2007.

- K.-H. Ludwig: Mountain regulations, technical and social change in the transition from the Middle Ages to the modern age. In: History of Technology. 52, 1985, pp. 179-196.

- C. von Looz-Corswarem: The western parts of the country. In: J. Ziechmann (ed.): Panorama of the Friderician time. Frederick the Great and his epoch. A manual. Bremen 1985, pp. 695-704.

- A. Meister: Commerce, trade, industry and mining until the beginning of the 19th century. In: A. Meister (Ed.): Die Grafschaft Mark. Festschrift to commemorate the 300-year union with Brandenburg-Prussia. Volume 1. Dortmund 1909.

- P. Piasecki: New technologies, rationalization and the development of the workforce structure in the Westphalian salt pans from the middle of the 18th to the beginning of the 20th century. In: T. Hellmuth, E. Hiebl (Ed.): Cultural history of salt: 18th to 20th century. Vienna / Munich 2001, pp. 75–88.

- P. Piasecki: Investments in the Westphalian salt pans in the age of industrialization. In: Thesis. 4/5, 2002, pp. 74-83.

- H.-J. Puhle: Prussia: development and undesirable development. In: H.-J. Puhle, H.-U. Wehler (Ed.): An overview of Prussia. Göttingen 1980, pp. 11-42.

- H. Rachel: The trade, customs and excise policy of Prussia 1713-1740. Berlin 1922.

- W. Reininghaus: Economy, State and Society in the old County of Mark. In: E. Trox (Ed.): Prussia in southern Westphalia. Economy, society and the state, especially in the area of Grafschaft Mark until 1870/71. Lüdenscheid 1993, pp. 11-41.

- W. Reininghaus: The Brandenburg coal mining and Brandenburg-Prussia. An overview of the development in 1770. In: T. Schilp (Hrsg.): Das Muth-, Verleih- und Confirmationbuch 1770–1773. A source on the early history of the Ruhr mining industry . Edit v. Joachim Huske , Wilfried Reinighaus, Thomas Schilp. Dortmund 1993, pp. 15-45.

- G. Schmidt: "The praiseworthy Saltzwerck zu Sülbeck". History and development of a saltworks in Lower Saxony. Bochum 1995.

- R. Schütz: Prussia and its provinces. In: M. Schlenke (Ed.): Preußen-Ploetz. A historical balance sheet in dates and interpretations. Würzburg 1983, pp. 24-40.

- JJ Scotti: Collection of the laws and ordinances that were passed in the Duchy of Cleve and the County of Mark on matters of sovereignty, constitution, administration and the administration of justice, from the year 1418 to the entry of the royal Prussian governments in 1816. Volume 2. Düsseldorf 1826 .

- RP Sieferle: The underground forest. Energy crisis and industrial revolution. Munich 1982.

- JD von Steinen: Westphalian history. Part 2. Lemgo 1755.

- D. Stievermann: Absolutist centralism or class regionalism? Prussia and its western provinces in the 17th and 18th centuries. In: Westphalian magazine. 138, 1988, pp. 51-65.

- L. Suhling: Mining, Territorial Rule and Technological Change. Process innovations in the mining industry of the Renaissance using the example of Central European silver production. In: U. Troitzsch, G. Wohlauf (Hrsg.): Technology history. Historical contributions and recent essays. Frankfurt am Main 1980, pp. 139-179.

- W. Timm: From the Brockhauser salt works to the Königsborn salt works. A chapter of Brandenburg's economic history (= Hagener Hefte. Contributions to the history of the city of Hagen and Grafschaft Mark. Publications from Hagen City Archives, No. 7). Hagen 1978.

- W. Timm: 250 years of Königsborn 1734–1984. Unna 1984.

- J. Vogel: visionaries of progress. The Prussian and Austrian officials and the end of the old European salt city around 1800. In: W. Freitag (Hrsg.): Die Salzstadt. Old European structures and early modern innovations (= studies on regional history. Volume 19). Bielefeld 2004, pp. 195-209.

- H. Vollmerhaus: The inhabitants of the iron industry settlement Sessinghausen in the upper Volmetal and the Sessinghaus family from Unna in Westphalia. In: The Märker. 1963, pp. 129-139.

- H. Vollmerhaus: Rödinghauser Salzwerk and Bürenplatz zu Brockhausen near Unna 1489–1689. In: The Märker. 1964, pp. 251-254, 265-271.

- H.-H. Walter: Joachim Friedrich von Beust and his work on the salt pans. In: The cut. 42, 1990, pp. 26-43.

- W. Westhoff, W. Schlueter: History of the German mining law. In: Journal for Mining Law . 50, 1909, pp. 27–95, 230–269, 357–386 (edited from the estate by Oberbergrat Wilhelm Schlueter).

- F. Wiemers: The salt system on the Ems and Weser under Brandenburg-Prussia. A contribution to the genesis of the city of Bad Oeynhausen. Munster 1915.

- J. Ziechmann: Features of European economic and trade policy. In: J. Ziechmann (Hrsg.): Panorama of the Friderician time, Frederick the Great and his epoch. A manual. Bremen 1985, pp. 471-477.

Web links

Coordinates: 51 ° 33 '0.2 " N , 7 ° 40' 57.3" E