Graffiti: Difference between revisions

Crazytonyi (talk | contribs) Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Drawings and paintings on walls}} |

|||

{{cleanup}} |

|||

{{Other uses}} |

|||

{{pp|small=yes}} |

|||

{{Original research|date=March 2019}} |

|||

[[File:Former roof felt factory in Tampere Jun2012 003.jpg|thumb|350px|An abandoned roof felt factory with graffiti in [[Santalahti]], [[Tampere]], [[Finland]]]] |

|||

: ''See also [[Graffiti (PalmOS)]] for the [[PalmOS]] handwriting system.'' |

|||

'''Graffiti''' (plural; singular '''''graffiti''''' or '''''graffito''''', the latter rarely used except in archeology) is art that is written, painted or drawn on a wall or other surface, usually without permission and within public view.<ref name=oxd/><ref name=ahd/> Graffiti ranges from simple written [[Moniker (graffiti)|"monikers"]] to elaborate wall paintings, and has existed [[Graffito (archaeology)|since ancient times]], with examples dating back to [[ancient Egypt]], [[ancient Greece]], and the [[Roman Empire]] (see also [[mural]]).<ref name="Graffito"/> |

|||

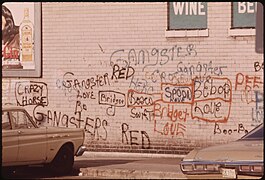

Graffiti is a controversial subject. In most countries, marking or painting property without permission is considered by property owners and civic authorities as defacement and [[vandalism]], which is a punishable crime, citing the use of graffiti by street gangs to mark territory or to serve as an indicator of gang-related activities.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.lapdonline.org/get_informed/content_basic_view/23471|title=Why Gang Graffiti Is Dangerous—Los Angeles Police Department|website=www.lapdonline.org|language=en|access-date=19 February 2018|archive-date=20 February 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180220033252/http://www.lapdonline.org/get_informed/content_basic_view/23471|url-status=dead}}</ref> Graffiti has become visualized as a growing urban "problem" for many cities in industrialized nations, spreading from the [[New York City Subway nomenclature|New York City subway]] system and [[Philadelphia]] in the early 1970s to the rest of the United States and Europe and other world regions.<ref>{{Cite book|title=Encyclopedia of the City|last=Caves|first=R. W.|publisher=Routledge|year=2004|pages=315}}</ref> |

|||

The term '''graffiti''' is the [[English plural|plural]] of ''graffito'', although the singular form is less commonly used. Both words have been borrowed from the [[Italian language]], and along with the English word "graphic", are in turn derived from the [[Greek language|Greek]] γραφειν (''graphein''), meaning ''to write''. In its modern day use, refers to deliberate human markings on property. Graffiti can take the form of art, drawings, or words, and is often illegal, especially when done without the property owner's consent. |

|||

== Etymology == |

|||

[[image:Gnv_lg_graffiti_wall.jpg|thumb|500px|right|This wall, in [[Gainesville, Florida]], has been set aside for use by graffiti artists and passersby.]] |

|||

[[File:Graffiti Kom Ombo.JPG|thumb|right|Ancient graffito in the [[Kom Ombo Temple]], Egypt]] |

|||

"Graffiti" (usually both singular and plural) and the rare singular form "graffito" are from the Italian word ''graffiato'' ("scratched").<ref>The Italian singular form "graffito" is so rare in English (except in specialist texts on archeology) that it is not even recorded or mentioned in some dictionaries, for example the Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English and the Cambridge Advanced Learner's Dictionary.</ref><ref name=oxd/><ref name="ahd">{{Cite web |last=Publishers |first=HarperCollins |title=The American Heritage Dictionary entry: graffiti |url=https://www.ahdictionary.com/word/search.html?q=graffiti |access-date=2024-03-26 |website=www.ahdictionary.com}}</ref> The term "graffiti" is used in [[art history]] for works of art produced by scratching a design into a surface. A related term is "[[sgraffito]]",<ref name=grant/> which involves scratching through one layer of pigment to reveal another beneath it. This technique was primarily used by potters who would glaze their wares and then scratch a design into them. In ancient times graffiti were carved on walls with a sharp object, although sometimes [[chalk]] or [[coal]] were used. The word originates from Greek {{lang|el|γράφειν}}—''graphein''—meaning "to write".<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.etymonline.com/word/graffiti|title=graffiti {{!}} Origin and meaning of graffiti by Online Etymology Dictionary|website=www.etymonline.com|language=en|access-date=19 February 2018}}</ref> |

|||

== |

== History == |

||

{{See also|Graffiti terminology|Roman graffiti|Megalithic graffiti symbols}} |

|||

[[File:Rufus est caricature villa misteri Pompeii.jpg|thumb|right|Ancient [[Pompeii]] graffito [[caricature]] of a politician. [[Villa of the Mysteries]].]] |

|||

[[File:Graffitti, Castellania, Malta.jpeg|thumb|right|Figure graffito, similar to a relief, at [[Castellania (Valletta)|the Castellania, in Valletta]]]] |

|||

'' |

The term ''graffiti'' originally referred to the [[inscription]]s, figure drawings, and such, found on the walls of ancient [[sepulchre]]s or ruins, as in the [[Catacombs of Rome]] or at [[Pompeii]]. Historically, these writings were not considered vandalism,<ref name=":2" /> which today is considered part of the definition of graffiti.<ref>{{cite web|title=How Old Is Graffiti?|url=http://wonderopolis.org/wonder/how-old-is-graffiti/|website=Wonderopolis|access-date=24 January 2017}}</ref> |

||

The only known source of the [[Safaitic]] language, an [[Old Arabic|ancient form of Arabic]], is from graffiti: inscriptions scratched on to the surface of rocks and boulders in the predominantly basalt desert of southern [[Syria]], eastern [[Jordan]] and northern [[Saudi Arabia]]. Safaitic dates from the first century BC to the fourth century AD.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://krc2.orient.ox.ac.uk/aalc/index.php/en/safaitic-database-online|title=Ancient Arabia: Languages and Cultures—Safaitic Database Online|last=dan|website=krc2.orient.ox.ac.uk|language=en-gb|access-date=19 February 2018|archive-date=20 February 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180220033117/http://krc2.orient.ox.ac.uk/aalc/index.php/en/safaitic-database-online|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web|url=http://krc.orient.ox.ac.uk/ociana/index.php/safaitic|title=The Online Corpus of the Inscriptions of Ancient North Arabia—Safaitic|last=dan|website=krc.orient.ox.ac.uk|language=en-gb|access-date=19 February 2018|archive-date=20 February 2018|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20180220033208/http://krc.orient.ox.ac.uk/ociana/index.php/safaitic|url-status=dead}}</ref> |

|||

The (believed to be) first example of "modern day" graffiti is found in the ancient Greek city of [[Ephesus]] in modern day [[Turkey]] and appears to be an advertisement for prostitution, according to the tour guides of the city. It is found near the long mosaic and stone walk way. It consists of a handprint, a vaguely heart-like shape, a footprint shape and a number. It is believed that this indicates how many steps one would have to take to find a lover with the handprint indicating payment. <!-- I will add a photo when I can find my photo taken in 1996 [[User:Alkivar]] --> |

|||

=== Ancient graffiti === |

|||

The [[ancient Rome|Romans]] carved graffiti into both their own walls and monuments and there are also, for instance, [[Egypt|Egyptian]] ones. The graffiti carved on the walls of [[Pompeii]] were preserved by the eruption of [[Vesuvius]] and offer us a direct insight into street life: everyday Latin, insults, magic, love declarations, political consigns. One example has even been found that stated "Cave Canem", which translates as "Beware of Dog". |

|||

Some of the oldest [[cave paintings]] in the world are 40,000 year old ones found in Australia.<ref name=":2">{{Cite book |last=McDonald |first=Fiona |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZnGCDwAAQBAJ |title=The Popular History of Graffiti: From the Ancient World to the Present |date=2013-06-13 |publisher=Simon and Schuster |isbn=978-1-62636-291-8 |language=en}}</ref> The oldest written graffiti was found in ancient Rome around 2500 years ago.<ref>{{Cite web |last1=Magazine |first1=Smithsonian |last2=Griggs |first2=Mary Beth |title=Archaeologists in Greece Find Some of the World's Oldest Erotic Graffiti |url=https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/erotic-graffiti-found-greece-180951979/ |access-date=2023-09-03 |website=Smithsonian Magazine |language=en}}</ref> Most graffiti from the time was boasts about sexual experiences.<ref>{{Cite news |last=Smith |first=Helena |date=2014-07-06 |title=2,500-year-old erotic graffiti found in unlikely setting on Aegean island |language=en-GB |work=The Guardian |url=https://www.theguardian.com/science/2014/jul/06/worlds-earliest-erotic-graffiti-astypalaia-classical-greece |access-date=2023-09-03 |issn=0261-3077}}</ref> Graffiti in Ancient Rome was a form of communication, and was not considered vandalism.<ref name=":2" /> |

|||

On the other hand, [[Viking]] graffiti can be found in [[Rome]], and [[Varangian]]s carved their [[rune]]s in [[Hagia Sophia]]. Many times in [[history]] graffiti were used as form of fight with opponents (see [[Orange Alternative]], for example). The Irish had their own inscriptive language called [[Ogham]]. |

|||

Ancient tourists visiting the 5th-century citadel at [[Sigiriya]] in Sri Lanka write their names and commentary over the "mirror wall", adding up to over 1800 individual graffiti produced there between the 6th and 18th centuries.<ref>{{Cite book |last1=Kljun |first1=Matjaž |last2=Pucihar |first2=Klen Čopič |title=Human-Computer Interaction – INTERACT 2015 |chapter="I Was Here": Enabling Tourists to Leave Digital Graffiti or Marks on Historic Landmarks |date=2015 |editor-last=Abascal |editor-first=Julio |editor2-last=Barbosa |editor2-first=Simone |editor3-last=Fetter |editor3-first=Mirko |editor4-last=Gross |editor4-first=Tom |editor5-last=Palanque |editor5-first=Philippe |editor6-last=Winckler |editor6-first=Marco |chapter-url=https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-319-22723-8_45 |series=Lecture Notes in Computer Science |volume=9299 |language=en |location=Cham |publisher=Springer International Publishing |pages=490–494 |doi=10.1007/978-3-319-22723-8_45 |isbn=978-3-319-22723-8}}</ref> Most of the graffiti refer to the frescoes of semi-nude females found there. One reads: |

|||

[[Fresco|Frescos]] and [[Mural|murals]] are art forms that involve leaving images and writing on wall surfaces. Like the ancient cave wall paintings in [[France]], they are not graffiti, as they are created with the explicit permission (and usually support) of the owner of the walls. |

|||

{{poemquote|Wet with cool dew drops |

|||

==20th century== |

|||

fragrant with perfume from the flowers |

|||

[[Image:GraffitiArtist.jpg|thumb|left|A graffiti artist at work with spray paint.]] |

|||

came the gentle breeze |

|||

jasmine and water lily |

|||

dance in the spring sunshine |

|||

side-long glances |

|||

of the golden-hued ladies |

|||

stab into my thoughts |

|||

heaven itself cannot take my mind |

|||

as it has been captivated by one lass |

|||

among the five hundred I have seen here.<ref name=parana>{{cite book|last=Paranavithana|first=Senarath|title=Sigiri Graffiti; Being Sinhalese Verses of the Eighth, Ninth and Tenth Centuries|year=1956|publisher=Govt. of Ceylon by Oxford UP|location=London}}</ref>}} |

|||

Among the ancient political graffiti examples were [[Arab]] satirist poems. Yazid al-Himyari, an [[Umayyad]] Arab and [[Persian language|Persian]] poet, was most known for writing his political poetry on the walls between [[Sistan|Sajistan]] and [[Basra]], manifesting a strong hatred towards the [[Umayyad]] regime and its ''[[wali]]s'', and people used to read and circulate them very widely.<ref>حسين مروّة، '''تراثنا كيف نعرفه'''، مؤسسة الأبحاث العربية، بيروت، 1986{{clarify|date=October 2014}}</ref>{{clarify|date=October 2014}} |

|||

Starting with the large-scale urbanization of many areas in the 20th century, urban [[gang]]s would mark walls and other pieces of public property with the name of their gang (a "tag") in order to mark the gang's territory. |

|||

Graffiti, known as Tacherons, were frequently scratched on Romanesque Scandinavian church walls.<ref name="green" /> |

|||

Near the end of the twentieth century, the practice of tagging became increasingly non-gang related and began to be practiced for its own sake. Graffiti artists would sign their "tags" for the sake of doing so and sometimes to increase their reputation and prestige as a "writer" or a graffiti artist. |

|||

When [[Renaissance]] artists such as [[Pinturicchio]], [[Raphael]], [[Michelangelo]], [[Domenico Ghirlandaio|Ghirlandaio]], or [[Filippino Lippi]] descended into the ruins of Nero's [[Domus Aurea]], they carved or painted their names and returned to initiate the ''[[Grotesque|grottesche]]'' style of decoration.<ref name="archeology" /><ref name="atlantic" /> |

|||

There are also examples of graffiti occurring in American history, such as [[Independence Rock]], a national landmark along the [[Oregon Trail]].<ref>{{cite web|title=Independence Rock—California National Historic Trail (National Park Service)|url=https://www.nps.gov/cali/planyourvisit/site5.htm|publisher=National Park Service|access-date=18 January 2018}}</ref> |

|||

Tags, like [[screenname]]s, are sometimes chosen to reflect some qualities of the writer. Some tags also contain subtle and often cryptic messages. The year in which the tag or graffito was created, and in some cases the writer's initials or other letters, are sometimes incorporated into the tag. In some cases, tags or graffiti are dedicated or created in memory of a deceased friend, and might read something to the effect of "DIVA Peekrevs R.I.P. JTL '99". |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" caption="Ancient graffiti"> |

|||

In some cases, graffiti (especially those done in memory of a deceased person) found on storefront gates have been so elaborate that shopkeepers have been hesitant to clean them off. Other highly elaborate works covering otherwise unadorned fences or walls may likewise be so elaborate that property owners or the government may choose to keep them rather than cleaning them off. |

|||

File : Graffiti 4.JPG|<small>Graffiti from the Museum of Ancient Graffiti [[:fr:Maison du graffiti ancien|(fr)]], France </small> |

|||

2487(Admiror paries).jpg|Ironic wall inscription commenting on boring graffiti |

|||

Jesus graffito.jpg|Satirical [[Alexamenos graffito]], possibly the earliest known [[Depiction of Jesus|representation of Jesus]] |

|||

AncientgrafS.jpg|Graffiti, [[Church of the Holy Sepulchre]], [[Jerusalem]] |

|||

Crusader Graffiti in the Church of the holy supulchure Jerusalem Victor 2011 -1-21.jpg|Crusader graffiti in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre |

|||

Hagia-sofia-viking.jpg|[[Vikings|Viking]] mercenary graffiti at the [[Hagia Sophia]] in [[Istanbul]], Turkey |

|||

Sigiriya-graffiti.jpg|Graffiti on the [[Sigiriya#Mirror wall|Mirror Wall]], [[Sigiriya]], [[Sri Lanka]] |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

=== Contemporary graffiti === |

|||

In the 20th century, '[[Kilroy was Here]]' became a famous graffito, along with ''Mr. Chad'', a face with only the eyes and a nose hanging over the wall, saying "What No...?" (thing that lacked at the time) during the time of rationing. |

|||

Later, French soldiers carved their names on monuments during the Napoleonic [[French Revolutionary Wars: Campaigns of 1798|campaign of Egypt]] in the 1790s.<ref name="JinxArtCrimes" /> [[Lord Byron]]'s survives on one of the columns of the Temple of [[Poseidon]] at [[Cape Sounion]] in [[Attica]], Greece.<ref name="shanks" /> |

|||

Some graffiti may be local or regional in nature, such as wall tagging in [[Southern California]] by [[gang]]s such as the [[Bloods]] and the [[Crips]]. The name ''Cool "Disco" Dan'' (including the quotation marks) tends to be commonly seen in the [[Washington, DC]] area. Another famous graffiti in the [[Washington Metro|DC Metro]] area was found on the outer loop of the beltway on a railroad bridge near the [[Temple (Mormonism)|Mormon temple]] ([http://www.lds.org/temples/main/0,11204,1912-1-52-2,00.html seen here]), its simple scrawl "surrender dorothy" summoned visions of the Emerald City of [[Wizard of Oz|Oz]] and remained on the bridge for nearly 30 years (arrived sometime in 1973) before pressure from the Temple had it finally removed in 1999. |

|||

The oldest known example of graffiti monikers found on traincars created by hobos and railworkers since the late 1800s. The Bozo Texino monikers were documented by filmmaker [[Bill Daniel (filmmaker)|Bill Daniel]] in his 2005 film, ''Who is Bozo Texino?''.<ref name="bozo-texino-walker">{{cite web |last=Daniel |first=Bill |date=22 July 2010 |title=Who Is Bozo Texino? |url=https://walkerart.org/calendar/2010/who-is-bozo-texino |access-date=23 August 2018}}</ref><ref name="bozo-texino-film">{{cite web |last=Daniel |first=Bill |date=2005 |title=Who Is Bozo Texino? |url=http://www.billdaniel.net/who-is-bozo-texino/ |access-date=23 August 2018 |work=Who Is Bozo Texino? The Secret History of Hobo Graffiti}}</ref> |

|||

[[Image:Graffiti.jpg|thumb|300px|This construction scaffolding has been "tagged".]] |

|||

In [[World War II]], an inscription on a wall at the fortress of [[Verdun]] was seen as an illustration of the US response twice in a generation to the wrongs of the Old World:<ref name="reagan" /><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/1985/08/14/opinion/words-from-a-war.html|title=Words From a War|date=14 August 1985|newspaper=The New York Times|access-date=2 January 2017}}</ref> |

|||

A number of words and phrases have been coined to describe different styles and aspects of graffiti. A ''tag'' is a stylized signature, while a tagger or a ''writer'' is a person who "tags". A ''crew'' is a group of writers or graffiti artists. |

|||

{{poemquote| |

|||

Informal competition sometimes exists between taggers as to who can put up the most, or the most visible or artistic tags. Writers with the most tags up will gain respect among other graffiti artists, although they will also incur a greater risk that if caught by authorities, they will be held responsible for a greater number of tags. |

|||

Austin White – Chicago, Ill – 1918 |

|||

Austin White – Chicago, Ill – 1945 |

|||

This is the last time I want to write my name here.}} |

|||

During World War II and for decades after, the phrase "[[Kilroy was here]]" with an accompanying illustration was widespread throughout the world, due to its use by American troops and ultimately filtering into American popular culture. Shortly after the death of [[Charlie Parker]] (nicknamed "Yardbird" or "Bird"), graffiti began appearing around New York with the words "Bird Lives".<ref name=russel /> |

|||

To ''line'' somebody's tag is to put a line through it and is considered a deep insult. |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" caption="World War II graffiti"> |

|||

The phrase ''back to back'' refers to a graffito that is done all the way across a wall from one end to the next. This could be seen in some parts of the West side of the [[Berlin Wall]]. |

|||

Bundesarchiv Bild 101I-309-0816-20A, Italien, Soldat zeichnend.jpg|Soldier with tropical fantasy graffiti (1943–1944) |

|||

Graffiti inside the ruins of the German Reichstag building.jpg|Soviet Army graffiti in the ruins of the [[Reichstag building|Reichstag]], in [[Berlin]] (1945) |

|||

Kilroy Was Here - Washington DC WWII Memorial - Jason Coyne.jpg|Permanent engraving of [[Kilroy was here|Kilroy]] on the [[World War II Memorial]], in [[Washington, D.C.]] |

|||

</gallery><gallery mode="packed" caption="Early spray-painted graffiti"> |

|||

NYC R36 1 subway car.png|[[New York City Subway]] trains were covered in graffiti (1973). |

|||

GRAFFITI ON A WALL IN CHICAGO. SUCH WRITING HAS ADVANCED AND BECOME AN ART FORM, PARTICULARLY IN METROPOLITAN AREAS.... - NARA - 556232.jpg|Graffiti in [[Chicago]] (1973) |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

=== Modern Graffiti === |

|||

Theories and use of graffiti by [[avant-garde]] artists has a history dating at least to the [[Scandinavian Institute of Comparative Vandalism]] in [[1961]]. |

|||

Modern graffiti art has its origins with young people in 1960s and 70s in [[New York City]] and [[Philadelphia]]. [[Tag (graffiti)|Tags]] were the first form of stylised contemporary graffiti. Eventually, throw-ups and [[Piece (graffiti)|pieces]] evolved with the desire to create larger art. Writers used spray paint and other kind of materials to leave tags or to create images on the sides subway trains.<ref>{{Cite web |last=Tate |title=Graffiti art |url=https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/g/graffiti-art |access-date=2023-02-23 |website=Tate |language=en-GB}}</ref> and eventually moved into the city after the NYC metro began to buy new trains and paint over graffiti.<ref>{{Cite journal |last=Snyder |first=Gregory J. |date=2006-04-01 |title=Graffiti media and the perpetuation of an illegal subculture |url=http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/1741659006061716 |journal=Crime, Media, Culture|language=en |volume=2 |issue=1 |pages=93–101 |doi=10.1177/1741659006061716 |s2cid=144911784 |issn=1741-6590}}</ref> |

|||

While the art had many advocates and appreciators—including the cultural critic [[Norman Mailer]]—others, including New York City mayor [[Ed Koch]], considered it to be defacement of public property, and saw it as a form of public blight.<ref name=":02">{{Cite web |title=The history of graffiti |url=https://learnenglishteens.britishcouncil.org/skills/reading/b2-reading/history-graffiti |access-date=2023-03-24 |website=learnenglishteens.britishcouncil.org |language=en}}</ref> The ‘taggers’ called what they did ‘writing’—though [[The Faith of Graffiti|an important 1974 essay]] by Mailer referred to it using the term ‘graffiti.’<ref name=":02"/> |

|||

Some of those who practice graffiti [[art]] are keen to distance themselves from [[gang]] graffiti. There are differences in both form and intent. The purpose of graffiti art is self-expression and creativity, and may involve highly stylized letter forms drawn with markers, or cryptic and colorful spray paint murals on walls, buildings, and even freight trains. Graffiti artists strive to improve their art, which is constantly changing and progressing. The purpose of gang graffiti, on the other hand, is to mark territorial boundaries, and is therefore limited to a gang's neighborhood; it does not presuppose artistic intent. |

|||

Contemporary graffiti style has been heavily influenced by [[hip hop culture]]<ref name="genius-paul-edwards-hiphopbook">{{cite web|url=https://genius.com/Paul-edwards-is-graffiti-really-an-element-of-hip-hop-book-excerpt-annotated|title=Is Graffiti Really An Element Of Hip-Hop? (book excerpt)|date=10 February 2015|work=The Concise Guide to Hip-Hop Music|access-date=23 August 2018|first=Paul|last=Edwards}}</ref> and the myriad international styles derived from [[Philadelphia]] and [[New York City Subway]] graffiti; however, there are many other traditions of notable graffiti in the twentieth century. Graffiti have long appeared on building walls, in [[latrine]]s, railroad [[boxcar]]s, [[rapid transit|subways]], and bridges. |

|||

An early graffito outside of New York or Philadelphia was the inscription in London reading "[[Clapton is God]]" in reference to the guitarist [[Eric Clapton]]. Creating the cult of the guitar hero, the phrase was spray-painted by an admirer on a wall in [[Islington]], north London, in the autumn of 1967.<ref>{{cite news |last1=Hann |first1=Michael |date=12 June 2011 |title=Eric Clapton creates the cult of the guitar hero |work=The Guardian |url=https://www.theguardian.com/music/2011/jun/12/eric-clapton |url-status=live |access-date=16 December 2016 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20170311172627/https://www.theguardian.com/music/2011/jun/12/eric-clapton |archive-date=11 March 2017}}</ref> The graffito was captured in a photograph, in which a dog is [[Urine marking#Canidae|urinating on the wall]].<ref>{{cite news |last=McCormick |first=Neil |date=24 July 2015 |title=Just how good is Eric Clapton? |work=The Telegraph |location=London |url=https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/rockandpopfeatures/11501274/Just-how-good-is-Eric-Clapton.html |url-status=live |access-date=3 April 2018 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171124071909/http://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/music/rockandpopfeatures/11501274/Just-how-good-is-Eric-Clapton.html |archive-date=24 November 2017}}</ref> |

|||

Films like [[Style Wars]] in the 80s depicting famous writers such as Skeme, [[DONDI|Dondi]], MinOne, and [[Zephyr (artist)|ZEPHYR]] reinforced graffiti's role within New York's emerging hip-hop culture. Although many officers of the New York City Police Department found this film to be controversial, Style Wars is still recognized as the most prolific film representation of what was going on within the young hip hop culture of the early 1980s.<ref name="labonte" /> Fab{{nbsp}}5 Freddy and Futura 2000 took hip hop graffiti to Paris and London as part of the New York City Rap Tour in 1983.<ref name="hershk" /> |

|||

==Legal situation== |

|||

=== Commercialization and entrance into mainstream pop culture === |

|||

[[Image:Graffitti-face.jpg|thumb|Illegal graffiti can be elaborate, but may be seen as a nuisance]] |

|||

{{Main|Commercial graffiti}} |

|||

With the popularity and legitimization of graffiti has come a level of commercialization. In 2001, computer giant [[IBM]] launched an advertising campaign in Chicago and San Francisco which involved people spray painting on sidewalks a [[peace symbol]], a [[Heart (symbol)|heart]], and a [[penguin]] ([[Tux (mascot)|Linux mascot]]), to represent "Peace, Love, and Linux." IBM paid Chicago and San Francisco collectively US$120,000 for punitive damages and clean-up costs.<ref name=guerilla/><ref name=wired/> |

|||

Graffiti is subject to different societal pressures from popularly-recognized art forms, since graffiti appears on walls, freeways, buildings, trains or any accessible surfaces that are not owned by the person who applies the graffiti. This means that graffiti forms incorporate elements rarely seen elsewhere. Spray paint and broad permanent markers are commonly used, and the organizational structure of the art is sometimes influenced by the need to apply the art quickly before it is noticed by authorities. |

|||

In 2005, a similar ad campaign was launched by [[Sony]] and executed by its advertising agency in New York, Chicago, Atlanta, Philadelphia, Los Angeles, and Miami, to market its handheld [[PlayStation Portable|PSP]] gaming system. In [[PlayStation Portable#Controversial advertising campaigns|this campaign]], taking notice of the legal problems of the IBM campaign, Sony paid building owners for the rights to paint on their buildings "a collection of dizzy-eyed urban kids playing with the PSP as if it were a skateboard, a paddle, or a rocking horse".<ref name=wired/><!-- Image with unknown copyright status removed: [[File:Yarnbus.jpg|thumb|This bus has been [[yarn bombing|yarn bombed]] by a team of knitters. {{Deletable image-caption|date=May 2012}}]] --> |

|||

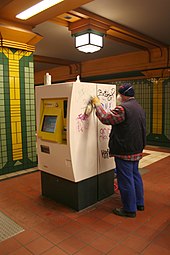

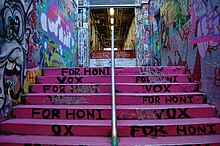

In an effort to reduce vandalism, many cities have designated walls or areas exclusively for use by graffiti artists. It has been suggested that this discourages petty vandalism yet encourages artists to take their time and produce great art, without worry of being caught or arrested for vandalism or [[trespassing]]. Some disagree with this approach, arguing that the presence of legal graffiti walls has not been shown to reduce illegal graffiti elsewhere. |

|||

=== Global developments === |

|||

[[Image:Us-nogutsnofame.JPG|thumb|350px|left|Computer generated graffiti ''No Guts, No Fame'', its noticeable "anti-police" theme shows its artists frustration with the percieved illegal threat of graffiti.]] |

|||

==== South America ==== |

|||

Tristan Manco wrote that Brazil "boasts a unique and particularly rich, graffiti scene ... [earning] it an international reputation as the place to go for artistic inspiration". Graffiti "flourishes in every conceivable space in Brazil's cities". Artistic parallels "are often drawn between the energy of São Paulo today and 1970s New York". The "sprawling metropolis", of São Paulo has "become the new shrine to graffiti"; Manco alludes to "poverty and unemployment ... [and] the epic struggles and conditions of the country's marginalised peoples", and to "Brazil's chronic poverty", as the main engines that "have fuelled a vibrant graffiti culture". In world terms, Brazil has "one of the most uneven distributions of income. Laws and taxes change frequently". Such factors, Manco argues, contribute to a very fluid society, riven with those economic divisions and social tensions that underpin and feed the "folkloric vandalism and an urban sport for the disenfranchised", that is South American graffiti art.<ref name=manco7/> |

|||

Many people regard graffiti as an unwanted nuisance, or as expensive [[vandalism]] that must be repaired. It may be seen as a [[quality of life]] issue, and it is often suggested that the presence of graffiti contributes to a general sense of squalor and a heightened fear of [[crime]]. Advocates of the ''broken window theory'' believe that this sense of decay encourages further vandalism and leads to more serious offences being committed. |

|||

<!-- Deleted image removed: [[File:IMG 6754 3.jpg|thumb|Poetry graffiti in [[Tel Aviv]], [[Israel]]]] -->[[File:Graffiti in Tel Aviv, Israel.jpg|thumb|A graffiti piece by the artist DeDe found in [[Tel Aviv]]]] |

|||

To remove graffiti, [[high pressure cleaning]] can be used; it can also be painted over or, as a prevention, a specially formulated anti-graffiti coating can be applied to the surface of high-risk areas. |

|||

The [[Anti-Social Behaviour Act 2003]] is the latest anti-graffiti legislation to be passed in Britain. |

|||

Prominent Brazilian writers include [[OSGEMEOS|Os Gêmeos]], Boleta, [[Francisco Rodrigues da Silva|Nunca]], Nina, Speto, Tikka, and T.Freak.<ref name=globo/> Their artistic success and involvement in commercial design ventures<ref name=nicek/> has highlighted divisions within the Brazilian graffiti community between adherents of the cruder transgressive form of ''[[pichação]]'' and the more conventionally artistic values of the practitioners of ''grafite''.<ref name=revela/> |

|||

In [[August]] [[2004]], the [[Keep Britain Tidy]] campaign issued a [http://www.encams.org/News/newsRelease.asp?ArticleID=65&Sub=0&Menu=0.26.12.60 press release] calling for [[zero tolerance]] of graffiti, with support for proposals such as issuing "on the spot" [[fine]]s to graffiti offenders and banning the sale of aerosol paint to teenagers. The press release also condemned the use of graffiti images in advertising and in music videos, arguing that real world experience of graffiti was far from the 'cool' or 'edgy' image that was often portrayed. To back the campaign, 123 British [[Member of Parliament|MP]]s (including [[Prime Minister]] [[Tony Blair]]) signed a charter which stated: ''“Graffiti is not art, it’s crime. On behalf of my constituents, I will do all I can to rid our community of this problem.”'' |

|||

== |

==== Middle East ==== |

||

[[Image:Graffitiforvandalismarticle.jpg|thumb|300px|left|Graffiti in [[Melbourne]], Australia]] |

|||

The strand of graffiti art which is considered one of the four elements of [[hip hop]] is usually denoted urban ''''''Aerosol Art''''''. Sometimes synonymous with "hip-hop heads," so-called ''graffiti artists'' have gone beyond that stereotype and are abundant even among middle-class white children. There are different genres, from [[Philadelphia, Pennsylvania|Philly]]'s ''[[wicked style]]'' to [[California]] and [[New York]]'s ''[[wild style]]'' graffiti. Graffiti artists are classified based on their style or even on what surface they use. |

|||

Graffiti in the [[Middle East]] has emerged slowly, with taggers operating in [[Egypt]], [[Lebanon]], the [[Arab states of the Persian Gulf|Gulf countries]] like [[Bahrain]] or the [[United Arab Emirates]],<ref>{{Cite book|last1=Zoghbi|first1=Pascal|url=https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/818463305|title=Arabic graffiti = Ghirāfītī ʻArabīyah|last2=Stone|last3=Hawley|first3=Joy|date=2013|publisher=From Here to Fame|isbn=978-3-937946-45-0|location=Berlin|oclc=818463305}}</ref> [[Israel]], and in [[Iran]]. The major Iranian newspaper ''[[Hamshahri]]'' has published two articles on illegal writers in the city with photographic coverage of Iranian artist [[A1one]]'s works on Tehran walls. Tokyo-based design magazine, ''PingMag'', has interviewed A1one and featured photographs of his work.<ref name=pinmag/> The [[Israeli West Bank barrier]] has become a site for graffiti, reminiscent in this sense of the [[Berlin Wall]]. Many writers in Israel come from other places around the globe, such as JUIF from Los Angeles and DEVIONE from London. The religious reference "נ נח נחמ נחמן מאומן" ("[[Na Nach Nachma Nachman Meuman]]") is commonly seen in graffiti around Israel. |

|||

Graffiti [[tagging]] existed in [[Philadelphia]] during the [[1960s]], pioneered by ''Cornbread'' and ''Cool Earl''. Another Philadelphia product, ''Top Cat'', later exported the characteristic Philly style of script (tall, slender lettering with platforms at the bottom) to [[New York City]] where it gained popularity as "Broadway Elegant". It wasn't until it reached popularity in the [[New York City subway system]] that it took on an extravagant artistic role, expanding from tags to full-blown "pieces". |

|||

Graffiti has played an important role within the [[street art]] scene in the Middle East and North Africa ([[MENA]]), especially following the events of the [[Arab Spring]] of 2011 or the [[Sudanese Revolution]] of 2018/19.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Bashir's Overthrow Inspires Sudan Graffiti Artists|url=https://english.aawsat.com/home/article/1695246/bashirs-overthrow-inspires-sudan-graffiti-artists|access-date=2021-06-29|website=Asharq AL-awsat|language=en}}</ref> Graffiti is a tool of expression in the context of conflict in the region, allowing people to raise their voices politically and socially. Famous street artist [[Banksy]] has had an important effect in the street art scene in the MENA area, especially in [[State of Palestine|Palestine]] where some of his works are located in the [[Israeli West Bank barrier|West Bank barrier]] and [[Bethlehem]].<ref>{{Cite journal|last=DeTruk|first=Sabrina|date=2015|title=The "Banksy Effect" and Street Art in the Middle East|url=https://journals.ap2.pt/index.php/sauc/article/view/25|journal=SAUC – Street Art & Urban Creativity Scientific Journal|volume=1|issue=2|pages=22–30}}</ref> |

|||

One of the originators of New York graffiti was ''[[TAKI 183]]'' – a foot messenger who would tag his nickname around New York streets that he daily frequented en route. Taki was a [[Greek-American]] – his tag was diminutive for ''Demetrius'', while ''183'' came from his address. <!--A Greek-American, Taki was his nickname (diminutive for Demetrius); he took the ''183'' from his address. --> After being showcased in the [[New York Times]], his tag was being mimicked by hundreds of urban youth within months. |

|||

==== Southeast Asia ==== |

|||

It should be noted that there were other writers active in NYC before Taki, such as ''JULIO 204'', but he brought the most attention to the movement. With the innovation of art, and the craving to gain the widest audience, attempts by taggers were made. What developed was a strict adherence to spraypaint, sampling foreign [[calligraphy]], and the much anticipated [[mural]] (that usually covered an entire subway car). The artist was called a "[[writer]]," and so were groups of associated artists, called "crews". The movement spread on the streets, returned to the railroads where tagging was popularized by [[Hobo]]s, spread nationwide with the aid of media and [[Hip hop|rap music]]; thus, being yet mimicked again worldwide. |

|||

There are also a large number of graffiti influences in [[Southeast Asia]]n countries that mostly come from modern [[Western culture]], such as Malaysia, where graffiti have long been a common sight in Malaysia's capital city, [[Kuala Lumpur]]. Since 2010, the country has begun hosting a street festival to encourage all generations and people from all walks of life to enjoy and encourage Malaysian street culture.<ref name=kharbar/> |

|||

One of the earliest women to become active on the graffiti scene was New York City's "Lady Pink". Also known as Sandra Fabara, Lady Pink starred in the classic [[1982]] hip hop film "Wildstyle" when she was 18. |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" caption="Graffiti around the world"> |

|||

In the early 1980s, the combination of a booming art market and a renewed interest in painting resulted in the rise of a few graffiti artists to art-star status. [[Jean-Michel Basquiat]], a former street-artist known by his "Samo" tag, and [[Keith Haring]], a professionally-trained artist who adopted a graffiti style, were two of the most widely recognized graffiti artists. In some cases, the line between "simple" graffiti and unsanctioned works of [[public art]] can be difficult to draw. |

|||

File:Grafiti, Čakovec (Croatia).2.jpg|Graffiti on a wall in [[Čakovec]], Croatia |

|||

File:Graffiti in Budapest, Pestszentlőrinc.jpg|Graffiti of the character [[Bender (Futurama)|Bender]] on a wall in [[Budapest]], Hungary |

|||

File:Graffiti in Ho Chi Minh City.JPG|Graffiti in [[Ho Chi Minh City]], Vietnam |

|||

File:Mr. Wany's work-in-progress artwork for Kul Sign Festival.JPG|Graffiti art in [[Kuala Lumpur]], Malaysia |

|||

File:Graffiti in Yogyakarta, Indonesia.jpg|Graffiti in [[Yogyakarta]], Indonesia |

|||

File:Camperdown Memorial Rest Park Graffiti.jpg|Graffiti on a park wall in [[Sydney]], Australia |

|||

File:Graffitiensaopaulo.jpg|Graffiti in [[São Paulo]], Brazil |

|||

File:Absurdious-001.jpg|Absourdios. Tehran-Iran, 2009. |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

== Types of graffiti == |

|||

===Safety issues=== |

|||

{{See also|Graffiti terminology|Graffiti in the United States}} |

|||

Spray paint usually contains [[volatile organic compounds]] that are often highly toxic. Some graffiti artists who regularly work with spray paint develop [[neurology|neurological]] problems due to overexposure to VOCs. Compounds designed to remove graffiti can also be highly toxic (although the maintenance workers who work with these substances are usually more highly trained to use them safely.) [http://www.graffiti.org/faq/masks.html This article] from graffiti.org contains more information on the subject and recommends that spray painters wear a mask when painting. |

|||

=== Methods and production === |

|||

Some heavy duty [[permanent marker]]s also contain harmful VOCs, although the quantity of VOC released will probably be less than with spray paint. Those who use permanent markers should check the label and follow the safety instructions. |

|||

The modern-day graffitists can be found with an arsenal of various materials that allow for a successful production of a [[Piece (graffiti)|piece]].<ref name=nicolas/> This includes such techniques as [[Scribing (graffiti)|scribing]]. However, [[spray paint]] in aerosol cans is the number one medium for graffiti. From this commodity comes different styles, technique, and abilities to form master works of graffiti. Spray paint can be found at hardware and art stores and comes in virtually every color. |

|||

== Computer generated graffiti == |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" caption="Graffiti making"> |

|||

[[Image:Wiki-graffiti2.png|thumb|300px|left|Computer-generated graffiti reading "Wikipedia"]] |

|||

File:Vlg shop.jpg|The first graffiti shop in [[Russia]] was opened in 1992 in [[Tver]]. |

|||

File:Eurofestival graffiti 2.jpg|Graffiti application at Eurofestival in [[Turku]], Finland |

|||

File:Graffity in the making...(On a wall at Thrissur) CIMG9868.JPG|Graffiti application in India using natural pigments (mostly [[charcoal]], plant [[sap]]s, and dirt) |

|||

File:Graffity in the making...(On a wall at Thrissur) CIMG9873.jpg|Completed landscape scene, in [[Thrissur]], [[Kerala]], India |

|||

File:Leake Street TQ3079 352.JPG|A graffiti artist at work in [[London]] |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

=== Stencil graffiti === |

|||

Since many graffiti artists are considered vandals, many have moved to creating computer generated graffiti instead. Most of these types of artists are associated with [[ASCII art]], [[ANSI art]], and the [[Computer underground]]. |

|||

[[Stencil graffiti]] is created by cutting out shapes and designs in a stiff material (such as [[Corrugated fiberboard|cardboard]] or subject [[File folder|folder]]s) to form an overall design or image. The stencil is then placed on the "canvas" gently and with quick, easy strokes of the aerosol can, the image begins to appear on the intended surface. |

|||

==Graffiti Art Battle== |

|||

Some of the first examples were created in 1981 by artists [[Blek le Rat]] in Paris, in 1982 by [[Jef Aerosol]] in Tours (France);<ref>{{Cite web |last= |first= |date=2024-04-11 |title=The Evolution of Graffiti Art |url=https://artsfiesta.com/the-evolution-of-graffiti-art/ |access-date=2024-04-13 |website=Arts Fiesta |language=en-US}}</ref> by 1985 stencils had appeared in other cities including New York City, Sydney, and [[Melbourne]], where they were documented by American photographer Charles Gatewood and Australian photographer Rennie Ellis.<ref name="ellis" /> |

|||

In the early [[1980s]] one of the largest community "Graffiti Art Battles" took place next to the [[Bull Ring, Birmingham|Bull Ring]] shopping centre in [[Birmingham]], [[England]]. The city invited a selection of the UK's most renowned graffiti artists, including local artist ''[[Goldie]]'', [[Bristol]]'s ''[[Robert Del Naja|3D]]'' (who went on to form ''[[Massive Attack]]''), [[London]]'s ''[[Mode]]'' from the ''[[Chrome Angelz]]'', with [[Bronx]] Man ''[[Brim]]'' and his [[New York]] alter ego ''[[Bio (graffiti tagger)|Bio]]'' attending for good measure. |

|||

=== Tagging === |

|||

Massive boards were erected with scaffolding in place to enable free movement of the artists. It was a rare occasion of the age for so many prestigious artists to come together on one wall - many battles would lead to gang rivalry especially if one artist would "bite", or copy, another's style. Clips from the Battle can be seen in a [[Channel 4]] documentary titled ''Bombing''. |

|||

{{Main|Tag (graffiti)}} |

|||

Tagging is the practice of someone spray-painting "their name, initial or logo onto a public surface"<ref>{{Cite news|date=2022-01-18|title=Gullu Daley, Ajax Watson and Jestina Sharpe depicted in St Paul's street art|language=en-GB|work=BBC News|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-bristol-60039912|access-date=2022-01-19}}</ref> in a [[handstyle]] unique to the writer. Tags were the first form of modern graffiti. |

|||

[[Image:banksy.bomb.jpg|thumb|225px|right|Stencil art by Banksy. Brick Lane, London]] |

|||

[[File:Tag by Spore.jpg|thumb|A tag in [[Dallas]], reading "Spore"]]A number of recent examples of graffiti make use of [[hashtags]].<ref>{{Cite web |date=2015-07-23 |title=Hashtag on the pavement connects with Fitzrovia's past |url=http://fitzrovianews.com/2015/07/23/hashtag-on-the-pavement-connects-with-fitzrovias-past/ |access-date=2024-03-26 |website=Fitzrovia News |language=en-GB}}</ref><ref>{{Cite web |date= |title=#RISKROCK #GRAFFITI IN #SANFRANCISCO |url=https://massappeal.com/riskrock-graffiti-in-san-francisco/ |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20171011183228/https://massappeal.com/riskrock-graffiti-in-san-francisco/ |archive-date=2017-10-11 |website=Mass Appeal}}</ref> |

|||

{{wide image|Graffiti i baggård i århus 2c.jpg|1300px|align-cap=center|Densely-tagged parking area in [[Århus]], Denmark|center|}} |

|||

=== Modern experimentation === |

|||

==Street art== |

|||

[[File:Knitted graffiti 1.jpg|thumb|right|Knitted graffiti in [[Seattle]], Washington]] |

|||

In the '80s and early '90s the writers ''[[Cost (graffiti artist)|Cost]]'' and ''[[Revs]]'' were the first to get up with their name with the new techniques that would be a new form of graffiti, i.e. Post-Graffiti, or also known as Street Art. The participants use stencils, posters, stickers and installations to spread their art illegally in the streets. Since the '90s [[Shepard Fairey]] influenced many of today's street artists with his '[[Obey Giant]]' campaign. |

|||

[[File:Spiderweb Yarnbomb Installation by Stephen Duneier.JPG|thumbnail|Stephen Duneier's Spiderweb Yarnbomb installation hides and highlights previous graffiti.]] |

|||

Modern graffiti art often incorporates additional arts and technologies. For example, [[Graffiti Research Lab]] has encouraged the use of projected images and magnetic light-emitting diodes ([[LED art|throwies]]) as new media for graffitists. [[Yarn bombing|yarnbombing]] is another recent form of graffiti. Yarnbombers occasionally target previous graffiti for modification, which had been avoided among the majority of graffitists. |

|||

Other important Street Artists include C6.org, who incorporate new technologies into street graffiti art, [[Banksy]], probably the most famous of the stencil artists, D*Face (UK), [[Stak]], [[HNT]], [[Alexone]], [[André]] (France), [http://www.wearechangeagent.com/swoon/ Swoon], famous for the Cut-out Poster technique, Faile, (USA), [[Os Gemeos]], [[Herbert]] (Brazil), 6-_-©IIIII>@rtist.info, [[Flying Fortress (graffiti artist)|Flying Fortress]], [[Gomes]], [[Graffitilovesyou]], (Germany), Influenza, Erosie (Holland) and others. |

|||

== Uses == |

|||

A new form of tagging was created 1995 in Berlin by 6-_-©|||||>@rtist.info. He painted his 500 000 "6" tags with lime on wildly pasted posters, garbage and on the street . 30 % of his tags he painted while cycling. |

|||

Theories on the use of graffiti by [[avant-garde]] artists have a history dating back at least to the [[Asger Jorn]], who in 1962 painting declared in a graffiti-like gesture "the avant-garde won't give up".<ref>{{cite book | title=Expression as vandalism: Asger Jorn's "Modifications" | publisher=The University of Chicago Press | author=Karen Kurczynski | year=2008 | pages=293}}</ref> |

|||

== Radical and Political Graffiti == |

|||

Many contemporary analysts and even art critics have begun to see artistic value in some graffiti and to recognize it as a form of [[public art]]. According to many art researchers, particularly in the Netherlands and in Los Angeles, that type of public art is, in fact an effective tool of social [[emancipation]] or, in the achievement of a political goal.<ref name=thimar/> |

|||

Graffiti is sometimes seen as part of a subculture that rebels against extant societal authorities, or against authority as such. However these considerations are often divergent and relating to a wide range of practices. For some, graffiti is not only an art but also a lifestyle. For others it is a matter of political practice and forms just one tool in an array of methodologies and technologies or so-called anti-technologies of resistance. |

|||

In times of conflict, such murals have offered a means of communication and self-expression for members of these socially, ethnically, or racially divided communities, and have proven themselves as effective tools in establishing dialog and thus, of addressing cleavages in the long run. The [[Berlin Wall]] was also extensively covered by graffiti reflecting social pressures relating to the oppressive [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] rule over the [[East Germany|GDR]]. |

|||

The developments of graffiti art which took place in art galleries, colleges as well as "on the street" or "underground", contributed to the resurfacing in the 1990's of a far more overtly politicized form in the [[subvertising]], [[culture jamming]] or 'tactical media' movements. These movements or styles tend to classify the artists by their relationship to their social and economic contexts, since graffiti art is still illegal in many forms, in most countries. |

|||

Many artists involved with graffiti are also concerned with the similar activity of [[stenciling]]. Essentially, this entails stenciling a print of one or more colors using spray-paint. Recognized while [[Art exhibition|exhibiting]] and publishing several of her coloured stencils and paintings portraying the [[Sri Lankan Civil War]] and [[Urban area|urban Britain]] in the early 2000s, graffitists [[M.I.A. (artist)|Mathangi Arulpragasam, aka M.I.A.]], has also become known for integrating her imagery of political violence into her [[music videos]] for singles "[[Galang (song)|Galang]]" and "[[Bucky Done Gun]]", and her cover art. Stickers of her artwork also often appear around places such as London in [[Brick Lane]], stuck to lamp posts and street signs, she having become a muse for other graffitists and painters worldwide in cities including [[Seville]]. |

|||

Contemporary practitioners are therefore varied and often conflicting in their practices. There are those individuals such as [[Alexander Brener]] who have used the medium to politicise other art forms, and have taken the prison sentences forced onto them, as a means of further protest. Anonymous groups and individuals, however, are very varied also, with anonymous anti-capitalist art groups like the [[Space Hijackers]] who, in 2004, did an action about the capitalistic elments of [[Banksy]] and his use of political imagery. There are also those artists who are funded by a combination of government funding as well as commercial or private means, like irational.org who recently coined the term Advert Expressionism, replacing the word Abstract for Advert, in [[Clement Greenberg]]'s essay on [[Abstract Expressionism]]. |

|||

Graffitist believes that art should be on display for everyone in the public eye or in plain sight, not hidden away in a museum or a gallery.<ref name=":12">{{Cite web |title=Street and Graffiti Art Movement Overview |url=https://www.theartstory.org/movement/street-art/ |access-date=2023-03-24 |website=The Art Story |language=en}}</ref> Art should color the streets, not the inside of some building. Graffiti is a form of art that cannot be owned or bought. It does not last forever, it is temporary, yet one of a kind. It is a form of self promotion for the artist that can be displayed anywhere from sidewalks, roofs, subways, building wall, etc.<ref name=":12" /> Art to them is for everyone and should be showed to everyone for free. |

|||

See also: [[Writing]], [[visual art]], [[protest]] |

|||

=== Personal expression === |

|||

==Famous graffiti artists== |

|||

Graffiti is a way of communicating and a way of expressing what one feels in the moment. It is both art and a functional thing that can warn people of something or inform people of something. However, graffiti is to some people a form of art, but to some a form of vandalism.<ref name=":02"/> And many graffitists choose to protect their identities and remain anonymous or to hinder prosecution. |

|||

With the commercialization of graffiti (and [[Hip hop music|hip hop]] in general), in most cases, even with legally painted "graffiti" art, graffitists tend to choose anonymity. This may be attributed to various reasons or a combination of reasons. Graffiti still remains the [[hip hop#Culture|one of four hip hop elements]] that is not considered "performance art" despite the image of the "singing and dancing star" that sells hip hop culture to the mainstream. Being a graphic form of art, it might also be said that many graffitists still fall in the category of the [[Extraversion and introversion#Introversion|introverted archetypal artist]]. |

|||

===Hip-hop=== |

|||

* [[Robert Del Naja|3D]] from [[Massive Attack]] |

|||

* [[Brim]] |

|||

* [[DAIM]] |

|||

* [[Futura 2000]] |

|||

* [[Goldie]] |

|||

* [[Haze (graffiti artist)|Haze]] |

|||

* [[Jean-Michel Basquiat]] |

|||

* [[Loomit]] |

|||

* [[Mode2 (graffiti artist)|Mode2]] from [[Chrome Angels]] |

|||

* [[Neur]] |

|||

* [[Seen]] |

|||

* [[TAKI 183]] |

|||

[[Banksy]] is one of the world's most notorious and popular street artists who continues to remain faceless in today's society.<ref name=banksy/> He is known for his political, anti-war stencil art mainly in [[Bristol]], England, but his work may be seen anywhere from Los Angeles to [[Palestine (region)|Palestine]]. In the UK, Banksy is the most recognizable icon for this cultural artistic movement and keeps his identity a secret to avoid arrest. Much of Banksy's artwork may be seen around the streets of London and surrounding suburbs, although he has painted pictures throughout the world, including the Middle East, where he has painted on Israel's controversial [[West Bank]] barrier with satirical images of life on the other side. One depicted a hole in the wall with an idyllic beach, while another shows a mountain landscape on the other side. A number of [[Art exhibition|exhibitions]] also have taken place since 2000, and recent works of art have fetched vast sums of money. Banksy's art is a prime example of the classic controversy: vandalism vs. art. Art supporters endorse his work distributed in urban areas as pieces of art and some councils, such as Bristol and Islington, have officially protected them, while officials of other areas have deemed his work to be vandalism and have removed it. |

|||

===Street Art/Post Graffiti=== |

|||

* [[Banksy]] |

|||

* [[C6 (graffiti artist)|C6]] |

|||

[[Pixnit]] is another artist who chooses to keep her identity from the general public.<ref name=shaer/> Her work focuses on beauty and design aspects of graffiti as opposed to Banksy's anti-government shock value. Her paintings are often of flower designs above shops and stores in her local urban area of [[Cambridge, Massachusetts]]. Some store owners endorse her work and encourage others to do similar work as well. "One of the pieces was left up above Steve's Kitchen, because it looks pretty awesome"- Erin Scott, the manager of [[Tick (character)|New England Comics]] in [[Allston]], Massachusetts.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Pixnit was here {{!}} Stencil Archive|url=https://www.stencilarchive.org/content/pixnit-was-here|access-date=2021-06-03|website=www.stencilarchive.org}}</ref> |

|||

===Avant-Garde=== |

|||

* [[N.S.W Youth]] |

|||

Graffiti artists may become offended if photographs of their art are published in a commercial context without their permission. In March 2020, the [[Finland|Finnish]] graffiti artist Psyke expressed his displeasure at the newspaper ''[[Ilta-Sanomat]]'' publishing a photograph of a [[Peugeot 208]] in an article about new cars, with his graffiti prominently shown on the background. The artist claims he does not want his art being used in commercial context, not even if he were to receive compensation.<ref>Tamminen, Jari: ''Kuka omistaa graffitin?'' In ''[[Voima (newspaper)|Voima]]'' issue #1/2021, p. 40.</ref> |

|||

===Political=== |

|||

* [[Alexander Brener]] |

|||

* [[Asger Jorn]] |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" caption="Personal graffiti"> |

|||

===Misc=== |

|||

Graffiti at the Temple of Philae (XIII).jpg|Drawing at [[Philae temple complex|Temple of Philae]], [[Egypt]], depicting three men with rods, or staves |

|||

*[[Alexone]] |

|||

4091(Quisquis amat).jpg|Inscription in [[Pompeii]] lamenting a frustrated love: "Whoever loves, let him flourish, let him perish who knows not love, let him perish twice over whoever forbids love" |

|||

Post Apocalyptic Zombie Graffiti, Jan 2015.jpg|[[Apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction|Post-apocalyptic]] despair |

|||

Mermaid Sliema.JPG|[[Mermaid]] in [[Sliema]], [[Malta]] |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

=== Territorial === |

|||

==External links== |

|||

Territorial graffiti marks urban neighborhoods with tags and logos to differentiate certain groups from others. These images are meant to show outsiders a stern look at whose turf is whose. The subject matter of gang-related graffiti consists of cryptic [[symbols]] and [[initials]] strictly fashioned with unique [[calligraphies]]. Gang members use graffiti to designate membership throughout the gang, to differentiate rivals and associates and, most commonly, to mark borders which are both territorial and ideological.<ref name="ley" /> |

|||

=== As advertising === |

|||

* [http://www.at149st.com/ @149<sup>st</sup>] New York graffiti |

|||

{{Unreferenced section|date=March 2009}} |

|||

* [http://bomblondon.com Bomblondon] Political graffiti |

|||

*[http://www.counterproductiveindustries.com/gbgc God Bless Graffiti Coalition] Pro graffiti organization |

|||

* [http://the-raw-prawn.blogspot.com/2004/09/mcdonalds-uses-graffiti-to-woo-us.html Graffiti as an advertising medium] |

|||

* [http://www.graffiticreator.net/ Graffiticreator.net] Create your own graffiti |

|||

* [http://www.graffiti.org Graffiti.org] Art Crimes: The Writing on the Wall |

|||

* [http://www.jdoodle.com/index.jsp JDoodle.com] A graffiti Wiki |

|||

* [http://www.encams.org Keep Britain Tidy] UK organisation, campaigns against graffiti |

|||

* [http://www.bastardartist.com Los Angeles Graffiti Art] |

|||

* [http://www.bok.net/~jig/mural/muralprep.html Making Your Mural Last: Graffiti, Varnish and Wall Chemistry] |

|||

*[http://www2.cr.nps.gov/tps/briefs/brief38.htm Removing Graffiti from Historic Masonry] by [[National Park Service]] |

|||

* [http://www.ukgraffiti.com/# UK Graffiti Artists Today] |

|||

* [http://www.violadoresdelverso.org/graffstock/graffstock.asp] [[Violadores del Verso]] Graffstock, [[Zaragoza, Spain]]. |

|||

Graffiti has been used as a means of advertising both legally and illegally. [[The Bronx|Bronx]]-based [[TATS CRU]] has made a name for themselves doing legal advertising campaigns for companies such as [[Coca-Cola]], [[McDonald's]], [[Toyota]], and [[MTV]]. In the UK, Covent Garden's [[Boxfresh]] used stencil images of a [[Zapatista Army of National Liberation|Zapatista]] revolutionary in the hopes that cross referencing would promote their store. |

|||

=== Street Art/ Post-Graffiti === |

|||

*[http://1kg.de 6-_-©||||||||>@rtist.info] Post-graffiti art from Germany |

|||

*[http://www.goabove.com Above] Street artist from California |

|||

*[http://www.banksy.co.uk Banksy] Stencil artists from England |

|||

*[http://www.daim.org Daim´s Homepage] Street artist from Germany |

|||

*[http://www.duncancumming.co.uk DuncanCumming.co.uk] |

|||

*[http://www.ekosystem.org Ekosystem] A Street-art portal |

|||

*[http://www.crcstudio.arts.ualberta.ca/scrawl Scrawl] Collection of street art from around the world |

|||

*[http://www.stencilrevolution.com Stencil Revolution] Biggest Stencil community on the web |

|||

*[http://www.thelondonpolice.com The London Police] Streetart from the Netherlands |

|||

*[http://www.woostercollective.com/ Wooster Collective: A Celebration of Street Art] |

|||

[[Smirnoff]] hired artists to use [[reverse graffiti]] (the use of high pressure hoses to clean dirty surfaces to leave a clean image in the surrounding dirt) to increase awareness of their product. |

|||

== In film == |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" caption="Advertising graffiti"> |

|||

*''Style Wars'': Directed by Tony Silver, Produced by Henry Chalfant. Represents a history of the [[1980s]] NYC graffiti scene as seen thru the eyes of its participants. [http://imdb.com/title/tt0177262/ Style Wars at imdb]. |

|||

1969(Lais felat).jpg|Ancient [[Pompeii]]an graffiti advertising by a [[Procuring (prostitution)|pimp]] |

|||

*''Turk 182'' ([[1985]]) is a fictional account of graffiti used for political purposes in New York City. The name might be a reference to TAKI 183. [http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0090217/ Turk 182 at imdb] |

|||

Grafitti as advertising in China 02.jpg|Graffiti as advertising in [[Haikou]], [[Hainan]] Province, China, which is an extremely common form of graffiti seen throughout the country |

|||

Warszawa Stary Mokotów graffiti on shop window.jpg|Graffiti as legal advertising on a grocer's shop window in [[Warsaw]], Poland |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

=== Radical and political === |

|||

== Literature == |

|||

*Reisser, Mwinkand, Behrend: ''[[DAIM]] - daring to push the boundaries'' getting-up/reisser (Germany) 2004 ISBN 3-00-014155-3 |

|||

*van Treeck, Bernhard: ''Das große Graffiti-Lexikon'', Lexikon-Imprint-Verlag, Berlin, 2001, ISBN 3-89601-292-X |

|||

*van Treeck, Bernhard and Metze-Prou, Sibylle: ''Pochoir - die Kunst des Schablonengraffiti'', Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf, Berlin, 2000, ISBN 3-89602-327-6 |

|||

*van Treeck, Bernhard: Street Art Berlin, Schwarzkopf und Schwarzkopf, Berlin, 1999 ISBN 3-89602-191-5 |

|||

*van Treeck, Bernhard: ''Wandzeichnungen, Edition aragon'', Moers, 1995 ISBN 3-89535-424-4 |

|||

*''Urban Discipline 2000 - Graffiti-Art'' Peters/Reisser/Zahlmann. 2000 Ausstellungskatalog getting-up (Germany) ISBN 3-00-006154-1 |

|||

*''Urban Discipline 2001 - Graffiti-Art'' Peters/Reisser/Zahlmann. 2001 Ausstellungskatalog getting-up (Germany) ISBN 3-00-007960-2 |

|||

*''Urban Discipline 2002 - Graffiti-Art'' Peters/Reisser/Zahlmann. 2002 Ausstellungskatalog getting-up (Germany) ISBN 3-00-009421-0 |

|||

*''Exhibizion, Z 2000'' Ute Baumgärtel. 2000 Ausstellungskatalog/Exhibition catalogue Akademie der Künste Berlin Die Gestalten Verlag (Deutschland) ISBN 3-931126-34-x |

|||

*''Graffiti Art #1 Deutschland - Germany'' Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf (Germany), ISBN 3-89602-028-5 |

|||

*''Graffiti Art #3 Writing in München'', 1995, Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf (Germany) ISBN 3-89602-045-5 |

|||

*''Graffiti Art #4 Ruhrgebiet-Rheinland'' Hrsg: O. Schwarzkopf. 1995 Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf (Germany) ISBN 3-89602-051-x |

|||

*''Graffiti Art #7 Norddeutschland'' 1997 Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf (Germany), ISBN 3-89602-136-2 |

|||

*''Graffiti Art #9 Wände'' Hrsg: B. van Treeck. 1998 Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf (Germany) ISBN 3-89602-161-3 |

|||

*''Graffiti Art #8 Charakters'' B. van Treeck. 1998 Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf (Germany) ISBN 3-89602-144-3 |

|||

*''Broken Windows Graffiti NYC'' James Murray, Karla Murray. 2002 Ginko Press (USA), ISBN 1-58423-078-9 |

|||

*''NYC Graffiti'', Michiko Rico Nosé. 2000 Graphic-Sha Publishing (Japan) ISBN 4-7661-1177-x |

|||

*''Graffiti Oggi'' Karin Dietz. 2001 Ausstellungskatalog/Exhibition catalogue, Arte Contemporanea Hirmer/M. Wiedemann (Italy) |

|||

*''Aspects of Graffiti'', Wortbüro Stefan Michel/Zürich. 2001 Ausstellungskatalog, Rote Fabrik (Switzerland) |

|||

*''Backjumps Sketch Book'', Adrian Nabi. 1996, Backjumps (Deutschland), ISBN 3-9806846-0-1 |

|||

*''HamburgCity Graffiti'', 2003, Publikat Verlag (Deutschland), ISBN 3-980-74786-7 |

|||

*''Cope 2, True Legend'', Donatien B. Orns. 2003, Righters.com (France), ISBN 2-9520-0608-6 |

|||

*''Le graffiti dans tous ses états'', 2002, Ausstellungskatalog, Taxie Gallery (France) |

|||

*AT Down, 2000, Octopus (Frankreich), ISBN 2-9516384-0-x |

|||

*Stylefile, Blackbook Sessions.01, Markus Christl. 2002, Publikat Verlag (Germany), ISBN 3-9807478-2-4 |

|||

*Hip-Hop Lexikon, S. Krekow, J. Steiner, M. Taupitz. 1999, Lexikon Imprint Verlag (Germany), ISBN 3-89602-205-9 |

|||

*Swiss Graffiti, S. von Koeding, B. Suter. 1998, Edition Aragon (Germany), ISBN 3-89535-461-9 |

|||

*Graffiti Lexikon, B. van Treeck. 1998, Schwarzkopf & Schwarzkopf (Germany), ISBN 3-89602-160-5 |

|||

*Writer Lexikon, Bernhard van Treeck, 1995, Edition Aragon (Germany), ISBN 3-89535-428-7 |

|||

*Street Art Köln, B. van Treeck. 1996, Edition Aragon (Germany), ISBN 3-89535-434-1 |

|||

*Hall of Fame, M. Todt, B. van Treeck . 1995, Edition Aragon (Germany), ISBN 3-89535-430-9 |

|||

*Best of German graffiti. Band 1, Timeless-X. 2001, Verlag H. M. Hauschild (Germany), ISBN 3-89757-121-8 |

|||

*Langages de Rue #2, Graff-It!. 2004, Verlag Graf-It! (France), ISBN 2-914714-02-5 |

|||

*Street Art, Tristan Manco. Thames & Hudson. 2004 (UK), ISBN 0-500-28469-5 |

|||

*Grafftit World, Nicholas Ganz. Thames & Hudson. 2004 (UK) ISBN 0-500-51170-5 |

|||

[[File:M2109 Iraq War Protest (Black Bloc Element).jpg|thumb|upright=1.05|[[Black bloc]] members spray graffiti on a wall during an [[Protests against the Iraq War#March 21, 2009|Iraq War Protest]] in Washington, D.C.]] |

|||

{{hiphop}} |

|||

Graffiti often has a reputation as part of a subculture that rebels against authority, although the considerations of the practitioners often diverge and can relate to a wide range of attitudes. It can express a political practice and can form just one tool in an array of resistance techniques. One early example includes the [[anarcho-punk]] band [[Crass]], who conducted a campaign of stenciling [[anti-war]], [[anarchism|anarchist]], [[feminism|feminist]], and [[Anti-consumerism|anti-consumerist]] messages throughout the [[London Underground]] system during the late 1970s and early 1980s.<ref name=souther/> In [[Amsterdam]] graffiti was a major part of the punk scene. The city was covered with names such as "De Zoot", "Vendex", and "Dr Rat".<ref name=stockho/> To document the graffiti a punk magazine was started that was called ''Gallery Anus''. So when hip hop came to Europe in the early 1980s there was already a vibrant graffiti culture. |

|||

[[Category:Art]] |

|||

[[Category:Crimes]] |

|||

[[File:Anarchy police.jpg|thumb|left|Police car graffitied with [[Anarchist symbolism|anarchist symbols]]]] |

|||

[[Category:Hip hop]] |

|||

The student protests and general strike of [[May 1968 in France|May 1968]] saw Paris bedecked in revolutionary, anarchistic, and situationist slogans such as ''L'ennui est contre-révolutionnaire'' ("Boredom is counterrevolutionary") and ''Lisez moins, vivez plus'' ("Read less, live more"). While not exhaustive, the graffiti gave a sense of the 'millenarian' and rebellious spirit, tempered with a good deal of verbal wit, of the strikers. |

|||

{{quote box|align=right|width=220px|quote=I think graffiti writing is a way of defining what our generation is like. Excuse the French, we're not a bunch of p---- artists. Traditionally artists have been considered soft and mellow people, a little bit kooky. Maybe we're a little bit more like pirates that way. We defend our territory, whatever space we steal to paint on, we defend it fiercely.|source=—Sandra "Lady Pink" Fabara<ref name=chang/>}} |

|||

The developments of graffiti art which took place in art galleries and colleges as well as "on the street" or "underground", contributed to the resurfacing in the 1990s of a far more overtly politicized art form in the [[subvertising]], [[culture jamming]], or tactical media movements. These movements or styles tend to classify the artists by their relationship to their social and economic contexts, since, in most countries, graffiti art remains illegal in many forms except when using non-permanent paint. Since the 1990s with the rise of [[Street Art]], a growing number of artists are switching to non-permanent paints and non-traditional forms of painting.<ref name="ziptopia-switch">{{cite web|url=https://www.zipcar.com/ziptopia/city-living/temporary-street-art-changing-the-graffiti-game|title=Temporary Street Art That's Changing The Graffiti Game|work=Ziptopia|first=STEVEN|last=HARRINGTON |access-date=26 August 2018}}</ref><ref name="huffpost-streetart">{{cite web|url=https://www.huffingtonpost.com/ron-english/street-art-its-not-meant-_b_5610496.html|title=Street Art: It's Not Meant to be Permanent|work=Huffington Post|first=Ron|last=English|date=6 December 2017|access-date=26 August 2018}}</ref> |

|||

Contemporary practitioners, accordingly, have varied and often conflicting practices. Some individuals, such as [[Alexander Brener]], have used the medium to politicize other art forms, and have used the prison sentences enforced on them as a means of further protest.<ref name="voice" /> |

|||

The practices of anonymous groups and individuals also vary widely, and practitioners by no means always agree with each other's practices. For example, the anti-capitalist art group the [[Space Hijackers]] did a piece in 2004 about the contradiction between the capitalistic elements of Banksy and his use of political [[imagery]].<ref name="tanyabaxter-Gallery">{{cite web|url=http://tanyabaxtercontemporary.com/banksy#!Banksy_Flying_Copper__screen_print_on_paper__100_x_70_cm|title= Banksy |work=Tanya Baxter Contemporary Gallery|access-date=26 August 2018}}</ref><ref name="haynes-banksy">{{cite web|url=http://www.haynesfineart.com/artists/Banksy--|title= Banksy |work=Haynes Fine Art|access-date=26 August 2018}}</ref> |

|||

Berlin human rights activist [[Irmela Mensah-Schramm]] has received global media attention and numerous awards for her 35-year campaign of effacing [[Neo-Nazism|neo-Nazi]] and other [[Far-right politics|right-wing extremist]] graffiti throughout Germany, often by altering hate speech in humorous ways.<ref name=":1">{{Cite news|last=Ramsel|first=Yannick|date=8 January 2021|title=Die Hakenkreuzjägerin|work=Der Spiegel|url=https://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/irmela-mensah-schramm-beseitigt-rassistische-graffiti-und-aufkleber-die-hakenkreuzjaegerin-a-00000000-0002-0001-0000-000174784623}}</ref><ref name=":4">{{Cite news|last=Cataneo|first=Emily|date=12 April 2018|title=The Berliner Who Evaded Arrest|work=Off Assignment|url=https://www.offassignment.com/articles/emily-cataneo}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Graffiti, George Floyd protest, Minneapolis, Minnesota, June 2020 (49997279552).jpg|thumb|"Fuck [[List of police-related slang terms#T|12]]", an [[Anti-police sentiment#United States|anti-police]] message insulting the police on a wall in [[Minneapolis]]]] |

|||

<gallery mode="packed" caption="Political graffiti around the world"> |

|||

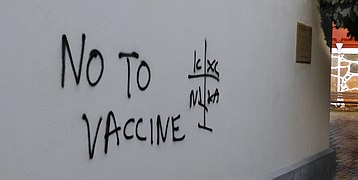

File:Graffiti - No To Vaccine - Ystad-2021.jpg|Graffiti with orthodox cross at the Catholic Church in [[Ystad]], 2021 |

|||

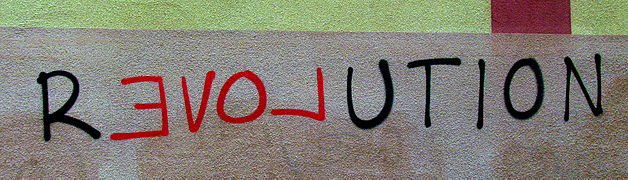

File:Revolution - 2014.jpg|"Revolution". [[Sweden]], 2014. |

|||

File:Anti Iraqi war graffiti by street artist Sony Montana in Cancun, Mexico.jpg|Anti Iraqi war graffiti by street artist Sony Montana in [[Cancún]], Mexico (2007) |

|||

File:Vote for Filip Filipovic.jpg|Wall in [[Belgrade]], Serbia, with the slogan "Vote for [[Filip Filipović (politician)|Filip Filipović]]", who was the [[League of Communists of Yugoslavia|communist]] candidate for the [[mayor of Belgrade]] (1920) |

|||

File:The separation barrier which runs through Bethlehem.jpg|An interpretation of ''[[Liberty Leading the People]]'' on the separation barrier which runs through [[Bethlehem]] |

|||

File:BerlinAnhalterBunker.jpg|WWII bunker near [[Berlin Anhalter Bahnhof|Anhalter Bahnhof]] ([[Berlin]]) with a graffiti inscription ''Wer Bunker baut, wirft Bomben'' (those who build bunkers, throw bombs) |

|||

File:Amsterdam Grafitti Freedom Lives When the State Dies.png|Graffiti on the train line leading to Central Station in [[Amsterdam]] |

|||

File:Riia-002.JPG|"Let's JOKK" in [[Tartu]] refers to political scandal with the [[Estonian Reform Party]] (2012). |

|||

File:Pieksämäki - Kekkos-graffiti IMG 0227 C.JPG|Stencil in [[Pieksämäki]] representing former president of Finland, [[Urho Kekkonen]], well known in Finnish popular culture |

|||

File:Keep your rosaries graffiti.jpg|[[Female graffiti artists|Feminist graffiti]] in [[A Coruña]], Spain, that reads ''Enough with rosaries in our ovaries'' |

|||

File:Australia steals Timor Oil.jpg|[[East Timor]]ese protest against Australian petroleum extraction |

|||

File:Kiss-EastSideGallery.jpg|Graffiti of two [[Second World|communist]] leaders [[Socialist fraternal kiss|kissing]], on the [[Berlin Wall]] |

|||

File:Bethlehem Wall Graffiti 1.jpg|Ironic graffiti in [[Bethlehem]], Palestine |

|||

File:Berliner Mauer.jpg|[[Berlin Wall]]: "Anyone who wants to keep the world as it is, does not want it to remain" |

|||

File:ACAB - Cusco, Peru.jpg|A [[List of police-related slang terms#P|pig]] above [[ACAB]], beside [[anti-Fujimorism]] graffiti in [[Cusco]], Peru |

|||

</gallery> |

|||

=== Genocide denial === |

|||

{{Undue weight|date=December 2023}} |

|||

In [[Serbia]]n capital, [[Belgrade]], the graffiti depicting a uniformed former [[General officer|general]] of [[Army of Republika Srpska|Serb army]] and [[War Criminal|war criminal]], convicted at [[International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia|ICTY]] for war crimes and crimes against humanity, including [[Bosnian genocide|genocide]] and [[Ethnic cleansing in the Bosnian War|ethnic cleansing]] in [[Bosnian War]], [[Ratko Mladić]], appeared in a military salute alongside the words "General, thank to your mother".<ref name="rferl.org">{{cite web |author1=Nevena Bogdanović |author2=Predrag Urošević |author3=Andy Heil |title=Graffiti War: Battle In The Streets Over Ratko Mladic Mural |url=https://www.rferl.org/a/serbia-mladic-mural-protests/31555357.html |website=Radio Free Europe / Radio Liberty |access-date=28 August 2022 |language=en |location=Belgrade |date=November 10, 2021}}</ref> |

|||

Aleks Eror, Berlin-based journalist, explains how "veneration of historical and wartime figures" through street art is not a new phenomenon in the region of former Yugoslavia, and that "in most cases is firmly focused on the future, rather than retelling the past".<ref name="calvertjournal.com-Eror">{{cite web |author1=Aleks Eror |title=How Serbian street art is using the past to shape the future |url=https://www.calvertjournal.com/articles/show/13353/ratko-mladic-mural-belgrade-serbia-are-revision-history-shape-future |website=The Calvert Journal |access-date=28 August 2022 |language=en |date=14 December 2021}}</ref> Eror is not only analyst pointing to danger of such an expressions for the region's future. In a long expose on the subject of [[Bosnian genocide denial]], at [[Balkan Diskurs]] magazine and multimedia platform website, Kristina Gadže and Taylor Whitsell referred to these experiences as a young generations' "cultural heritage", in which young are being exposed to celebration and affirmation of war-criminals as part of their "formal education" and "inheritance".<ref name="balkandiskurs.com">{{cite web |author1=Taylor Whitsell |author2=Kristina Gadže |title=New Generations Still Follow in a War Criminal's Footsteps |url=https://balkandiskurs.com/en/2021/12/15/new-generations-still-follow-in-a-war-criminals-footsteps/ |website=Balkan Diskurs |access-date=28 August 2022 |location=Belgrade |language=en |date=15 December 2021}}</ref> |

|||

[[File:Mural u Baru, prikaz ratnog zločinca Ratka Mladića.jpg|250px|thumb|right|Mural in [[Bar, Montenegro]], depicting the war criminal Ratko Mladić]] |

|||